ABSTRACT

Mentoring programmes are considered a core component of professional learning approaches for early career teachers (ECTs) as they commence in and progress through the first few years in the profession. Mentoring in the contemporary Australian context, however, is situated within a culture of high teacher standardisation, as is the case in numerous countries across the word. The Australian Professional Standards for Teachers (“the Standards”), for example, are the measuring device against which full teacher registration of ECTs is awarded as well as being put forward as the framework that informs teacher goal setting and development. In such circumstances, lines between mentoring purposed for teacher growth and for accountability may be blurred, and mentoring may be delimited to teachers’ work privileged in the Standards. In this paper, we report on data collected and thematically analysed from semi-structured interviews with 15 mentors and 15 ECTs from eight independent schools across Queensland and New South Wales in Australia about the role of the Standards in their mentoring work. Findings demonstrated that these mentors and ECTs address the Standards during mentoring ranging from regulatory to developmental to cursory. These findings have implications for the development of mentoring programmes, in Australia and elsewhere, where mentoring occurs in neoliberal cultures of audit.

Background

Mentoring is considered a core component of professional learning approaches for early career teachers (ECTs), also known as beginning teachers, as they commence in and progress through the first five years in the profession (Aarts et al., Citation2020; Miles & Knipe, Citation2018). Advocacy for this approach is grounded in its reported potential to assist novice teachers in managing and thriving in the earliest stages of their careers through professional capacity building, social and emotional support and socialisation into the profession. At a more pragmatic level, mentoring is seen as one weapon in a political arsenal seeking to reform education and stem the rising tide of ECT attrition (Goodwin et al., Citation2021), a contributing factor to the concerning teacher workforce shortages in both Australia (Heffernan et al., Citation2022) and internationally (Craig, Citation2017). In Australia, for example, there is, while not mandated, an expectation that all schools provide mentoring support to ECTs. However, contemporary mentoring occurs within a landscape of mounting performative accountability (Thompson et al., Citation2022).

Performance accountability takes the form of professional teacher standards in many OECD countries such as Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United States of America (US), and the United Kingdom (UK). In Australia, the site of this research, teachers are required to meet the Australian Professional Standards for Teachers (AITSL) (hereafter referred to as “Professional Standards”, “Teacher Standards” or “Standards”), introduced in 2011 as part of a larger national education reform agenda. Progressing through four career stages (graduate, proficient, highly accomplished, and lead) and constitutive of a set of seven overarching standards (see ) and 37 focus areas, these take on particular significance for ECTs as they must illustrate their practice against these Standards at the Proficient career stage to move from provisional to full teacher registration, also known as accreditation. This comes in the form of a portfolio that must be compiled by the ECT which serves as a collection of annotated evidence from their practice showing how these Standards have been met.

Table 1. Domains and standards of the Australian Professional Standards for Teachers (APSTs) (AITSL, Citation2017).

Furthermore, AITSL (Citation2023, p. 37) explicitly states with regard to mentoring that “it is expected that 100% of the programmes use the standards to guide professional growth of mentees to both Graduate and Proficient career stages”, opening the door to standards-driven mentoring, an approach seemingly encouraged in Standard 6.1: Use the Australian Professional Standards for Teachers and advice from colleagues to identify and plan professional learning needs.

In such circumstances, lines between mentoring for teacher growth and mentoring intended to improve teacher accountability may be blurred, and furthermore, mentoring may be delimited to the set of measurable functions (what teachers should know and do) as defined by the Standards. AITSL (Citation2011) argues that:

developing professional standards for teachers that can guide professional learning, practice and engagement facilitates the improvement of teacher quality and contributes positively to the public standing of the profession.

It is therefore critical to understand the ways in which the Standards and mentoring practice with ECTs intersect. In so doing, we respond to the following research question:

In what ways are the Teacher Standards addressed and used by teachers as they participate in the mentoring process?

This paper extends on work previously undertaken by Grima-Farrell et al. (Citation2019) on the deployment of Teacher Standards, though that work focused on the pre-service space. In that study (Grima-Farrell et al., Citation2019), the Teacher Standards are discussed from two different perspectives. Regulation, otherwise explained as assessment of the pre-service teachers’ effectiveness for purposes of accountability or assessment, was contrasted with development, with the Standards operating as a frame of reference for supervising teachers giving feedback to pre-service teachers on practicum for the purposes of building capacity in areas defined within the Standards (Grima-Farrell et al., Citation2019).

The current study subsequently builds on this conceptualisation of the Standards at work in mentoring to report on the experiential accounts of mentors and ECTs to understand their use of the Standards. In so doing, this study will seek to understand how mentors and ECTs perceive the role of the Teacher Standards in their mentoring practice and therefore to better understand how mentoring can navigate the challenges of standardisation and meet the complex needs of contemporary Australian ECTs.

This paper will firstly review the literature pertaining to factors of influence on mentoring practices for ECTs, internationally and in Australia, specifically in relation to mentoring and the use of professional standards. Following this, it will detail the methodology employed. Finally, it will present and discuss key findings and conclude with implications for practice and future research.

Mentoring ECTs and professional standards

The literature on mentoring of ECTs covers a range of topics, including: what mentoring is; the variety of mentor roles (Jaspers et al., Citation2014; Orland-Barak, Citation2001); the ways it contributes to student outcomes (Nolan & Molla, Citation2018; Shanks et al., Citation2022); the impact of mentoring on beginning teachers (Richter et al., Citation2013; Vaitzman Ben-David & Berkovich, Citation2021) and their retention in the profession. However, research into the perception and experience of mentoring within the context of the Standards for ECTs and mentors is limited.

Instead, research reports on the purpose of the Standards more generally in the ECT space in a myriad of ways. First, the Standards are often seen as a way of inducting new teachers into the profession (Darling-Hammond, Citation2017; Ingvarson, Citation2019). As such, the Teacher Standards are framed as what those in the profession need to know and do. Second, and related to this, is the view that the Standards are used as a tool for moving beginning teachers to full registration in the profession (Langdon et al., Citation2019). As such, the Standards are used as a “means by which good teaching can be identified, rewarded and celebrated” (Mayer et al., Citation2005, p. 160) via accountability processes. Third, the Standards may be seen as a tool for promoting professional learning (Mayer et al., Citation2005) more generally, with ECTs’ professional learning guided by how they respond to or meet each of the Standards (Adoniou & Gallagher, Citation2017).

Research about the use of the Standards within the mentoring process has often been situated in the pre-service teacher space. In Australia, for example, successful completion of pre-service teachers’ work-integrated learning is determined by their effective illustration of practice as defined by the Standards. Research has indicated, however, that among supervising mentors there is a tendency to use the Standards as a “tick box” approach rather than use them as a reflective tool (Bradbury et al., Citation2020) for teacher growth. Despite this, other studies have reported that beginning teachers may feel that the Standards help them to focus on all aspects of their teaching and that the requirement to collect evidence and demonstrate their performance against the Standards (Adoniou & Gallagher, Citation2017; Hudson & Hudson, Citation2016) forces them to reflect and “take stock” (Adoniou & Gallagher, Citation2017) of their progress as a developing teacher. Thus, as suggested by Grima-Farrell et al. (Citation2019), standards-driven discourses of regulation and development have been identified in the mentoring of pre-service teachers.

The Teacher Standards in Australia, and similar frameworks abroad, are often lauded in the policy space to explicitly benefit the profession. Standards have been espoused to provide a common professional language for teaching and an explicit framework that can be a powerful tool for assessing teacher performance and development, as well as to support their continuing growth at different stages of their career (Darling-Hammond, Citation2017; Sachs, Citation2016). In Australia, at the time of the release of the Teacher Standards in 2011, they were promoted as a basis for teacher development and reflection and as a guide to professional learning (Leonard, Citation2012). This focus has been undermined, however, by the frenetic movement toward reforming teacher practice to address perceived failings in competitive global rankings.

Instead, the Standards have been repurposed as part of the larger GERM (global education reform movement) (Sahlberg, Citation2010) that has “reshaped and reconfigured different aspects of teachers’ work and learning” (Mockler, Citation2022, p. 166). In other words, while teacher standards as a concept might have been initially conceived to align with professional learning and professional credibility, they have moved into a regulatory space where teachers need to provide evidence against the Standards to achieve registration and to be promoted to higher levels (Adoniou & Gallagher, Citation2017; Mahony & Hextall, Citation2000). In Australia, this has seen the prioritisation of excessive datafication, curriculum control, and pedagogical homogeneity placing teacher autonomy, creativity, and sense of professionalism under duress (Mockler, Citation2022). Power (Citation2009) notes that this regulatory approach is part of a general societal malaise where professions have fallen prey to organisation-specific internal control and compliance systems. In this context, the Standards can therefore be seen as a tool “for measuring the efficiency and effectiveness of systems, institutions and individuals” (Mahony & Hextall, Citation2000, p. 31), emphasising what can be measured at the expense of the immeasurable (Mahony & Hextall, Citation2000). Ryan and Bourke (Citation2018) note that a clear message has been sent through policy documents relating to the Teacher Standards that they will be used in identifying and dealing with unsatisfactory teacher performance. As a result, the Standards are used as the goal or outcome desired from the induction/mentoring programme, thus devaluing the supportive aspect which research shows can be integral to the development of ECTs (Polikoff et al., Citation2015; Spooner-Lane, Citation2017).

Using the Standards in this regulatory way may very likely create more pressure for ECTs (Mitchell et al., Citation2017), inhibit their learning (Adoniou, Citation2016), and create tensions between induction as an assessment and induction as support and socialisation (Mitchell et al., Citation2017). It seems apparent that the use of the Standards as an assessment tool in induction programmes narrows beginning teachers’ opportunities to develop their own teaching repertoire and professional autonomy and rather sees them being constructed as a particular sort of teacher (Devos, Citation2010) that mentors may also feel obligated to exemplify and promote. In some contexts, such as Hong Kong, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, and the Philippines (Asih et al., Citation2022), teacher standards linked to induction programmes for ECTs are recommended but not formally enforced and are not directly linked to accreditation and licensing, and thus are more about the schools’ context and needs (Goodwin & Low, Citation2021). However, in many countries, such as Australia, contemporary mentoring is faced with a prevailing tension between support for ECT growth and accountability, creating a discrepant space that mentors are also compelled to try and navigate.

Certainly, there is a necessity for further comprehensive and systematic research into beginning teachers and mentoring to inform the development of any future policy that seeks to fortify the role of Teacher Standards in mentoring practice. Whilst several studies (see Adoniou & Gallagher, Citation2017; Bradbury et al., Citation2020; Forde et al., Citation2016) comment on the tension between the developmental and regulatory roles of professional standards, to date, there appears to be a deficit of research studies that supports effective, balanced practice for mentors and ECTs. This study and paper go some way in addressing this need by investigating both the mentors’ and ECTs’ perceptions of the role of the Australian Teacher Standards in the mentoring process.

Before we describe the study’s methodology and present the findings, we need to acknowledge the research of Stephen Ball, Meg Maguire, and Annette Braun (Ball, Citation2012; Ball et al., Citation2011; Braun et al., Citation2010; Maguire et al., Citation2015) on the policy work of teachers in which teachers are described as both “receivers and agents” (Ball et al., Citation2011, p. 626) of policy. In so being, they enact, rather than implement, policy (Maguire et al., Citation2015) in multifaceted ways, with policy “a process that is diversely and repeatedly contested and/or subject to 'interpretation' as it is enacted in original and creative ways within institutions and classrooms” (Braun et al., Citation2010, p. 549). In this way, it can be said that schools and teachers work in ways that represent their own “take” on a policy (Braun et al., Citation2010, p. 547). That said, this paper does not adopt a critical orientation to understanding the socio-cultural factors that underlie the development of policy uptake; rather, it embraces an experiential orientation (Byrne, Citation2022) that seeks to understand and foreground the attitudes and experiences of those teachers engaged in mentoring work and the ways that they deem fit to engage, or not, with the Teacher Standards as part of this process.

Methodology

Participants in this study included 15 ECTs and 15 mentors from eight independent school sites, six in Queensland (QLD) (n = 20) and two in New South Wales (NSW) (n = 10) in 2022. Of the 15 ECT participants, 12 were female, and 10 of the 15 mentors were also female. ECTs included those in their first year of teaching, through to their third year, and mentors had a range of experience in a mentoring role from one year through to 10 years. All schools were year Prep (first year of formal schooling) – year 12 (final year of formal schooling) schools, except for one Year 3-Year 12 school. Participants worked in Primary (n = 18) and secondary (n = 12) settings. All participants were de-identified and allocated a pseudonym during the interview transcription phase. The first letter of the pseudonym indicates the state in which they work (Q-Queensland and N-New South Wales), the next letter indicates their role in the mentoring partnership (M-Mentor and E-ECT), and the number indicates their interview number. For example, QM3 is a mentor from Queensland.

The independent schools in which the participants were situated were representative of regional and metropolitan school settings of varying sizes across faith affiliations, philosophical and pedagogical persuasion, and the socio-cultural and economic characteristics of the communities they serve. Unlike their system-driven counterparts, independent schools in Australia are governed by their own school board rather than an overarching system authority. While independent schools are autonomous regarding their governance in comparison to their state-based or government-run school counterparts, they are still held accountable to “state and territory and Australian Government legislation which together impose requirements in relation to financial operation, accountability, the curriculum, assessment and reporting” (Independent Schools Australia, Citation2022, section 2). Thus, teachers within the independent sector are required to work with the Teacher Standards and illustrate their address of these for the purpose of teacher registration and employability.

As part of a larger mentoring project (The Future-focused Mentoring Project UniSQ HREC Approval number: H21REA310) for which these teachers had volunteered, and following written consent, 20–25-minute semi-structured online interviews were conducted by the research team at the start of the project with each mentor and ECT to gain an understanding of the participants’ mentoring experiences, practices, and beliefs. As part of this interview, participants were asked questions, such as:

What place do the Teacher Standards have in your mentoring conversations? Why do you think that is?

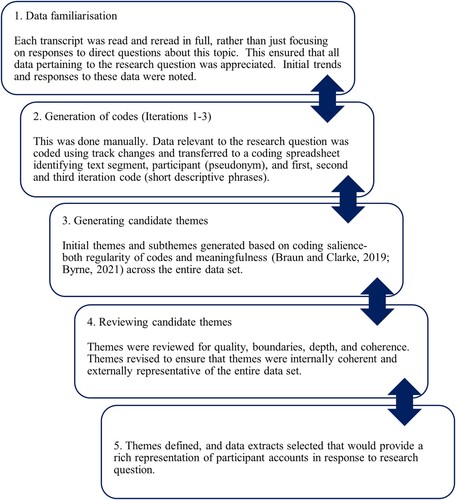

Figure 1. Data analysis process (adapted from Byrne Citation2022).

While Braun and Clarke (Citation2019) do not specifically hold to the appropriateness of intercoder reliability, they do consider it beneficial for dual researcher involvement for the purpose of reaching a greater depth and richness of data interpretation through collaborative exploration of data meaning and assumptions (Byrne, Citation2022). Two of the research team therefore collaboratively engaged with the interview data, with sense-making undertaken through a shared and provocative discussion of noticing and shared interpretation.

From this analysis, we arrived at three key findings in response to the research question. In essence, teachers demonstrated a:

Regulatory address of the Standards

Developmental address of the Standards

Cursory address of the Standards

These three ways in which mentors and early career teachers in this study used or referred to the Standards as part of their mentoring work will now be examined in turn.

Findings and discussion

The ways of working with the Standards, while categorised as regulatory, developmental, and cursory, were not necessarily stable, or exclusive to particular roles or individuals; rather, early career teachers and mentors alike moved between these enactments of the Standards though some ways of working were more prominent in some contexts and with some individuals.

The standards as regulatory

There was an acceptance among both the mentors and early career teachers that there was a need to address the Teacher Standards at some stage in the mentoring process as an essential requirement for the move to full teacher registration of ECTs. However, the address of the Standards for this purpose seemed to be positioned as a distinct mentoring activity focused on supporting teachers to understand what evidence of practice was required, and how it should be documented, in order that regulatory requirements were met. For example, QM19 explained that she ran specific sessions on the development of the ECTs’ e-portfolios, a digital compilation of illustrations of their practice against each of the Teacher Standards. This task occurred outside of scheduled mentoring conversations and was almost administrative in nature.

For a number of ECTs and mentors, the requirement that a portfolio of practice against each standard must be developed acts as an additional pressure that takes away time from the real work of teaching and the benefits of mentoring. For example, NE2 stated that:

And so I think the challenge is just under being under time pressure and knowing that I have to meet certain descriptors and standards and fill something in and find the time with [mentor] to discuss that.

Despite these frustrations, ECTs and mentors remain very aware of the high-stakes nature of addressing the Standards and note that addressing this aspect of the support process is unavoidable. As another ECT (NE10) explained:

At the moment I'm working on my accreditation, so my mentor is deliberately looking at the [S]tandards very closely and making sure that my teaching is aligned with the Standards because I wanna meet my accreditation.

Some mentors and ECTs managed this duality by keeping the regulatory aspect of the Standards in mind during mentoring conversations as their way of ensuring that their ECT did not get “caught out without the evidence they need for their portfolio” (QM7). As QM1 explained:

So we try to identify those [relevant Standards] … which will also help to hopefully eventually build that portfolio that will need to be created at some point. So the registration process is definitely in the back of my mind as we go …

She's working towards developing a portfolio, so I've actually talked to her about how she could use it as evidence. So if she's used a particular strategy, take a photo of it or if it’s a template or something, use that as a sample … to serve your purpose for the portfolio as well.

Yeah. So just using this for our portfolio, obviously, it should connect to the APSTs you want to work on. So it's kind of just you already have to do that. So why not just connect it to what practice you're doing?

The Standards as developmental

Whereas in some instances the Standards were only referenced during mentoring from a regulatory perspective, not all ECTs and mentors were averse to using the Standards in a more developmental manner. In some instances, mentors saw the Standards as a useful guide for mentoring conversations. In these cases, both mentors and ECTs saw the Standards as offering a direction or structure to the mentoring process; thus offering a guide through discussions about practice, as illustrated by NM4’s comment about the use of the Standards in their mentoring conversations:

I'm a standards nerd. I can see the value of those standards because they're not in opposition to what we're trying to do here as a school, and in fact, at times I think it's probably an easier entry point for teachers, especially early in their career.

Along with seeing a connection between their work as teachers and the Standards, some ECTs saw the Standards as providing a way of ensuring they were on track across the practices defined by the Standards and potential areas that require professional attention. For example, QE13 stated that:

I guess to me, the [S]tandards are a reminder of what we need to do; not so much as rules, but to kind of go back and see if you are meeting those things … I guess it's like a checklist if you're meeting all the requirements. It really narrows down which ones you need to do.

Yeah, I mean, I think they should be used as a really good way of framing the conversation. How can we improve your teaching? That's too big of a question. Say, right this term, we're gonna really focus on choosing some goals and working these descriptors rather than just broad brushstrokes.

So she went through each [Standard], one to say, “I think this is where you're at here, and this is where you're at here”, and giving me feedback on those areas. She gave me some really positive feedback as well as some areas for improvement. You know, it was helpful in giving me more motivation to work and giving me direction. I left it as well knowing that I've been meeting some expectations.

Thus, ECTs perceived the Standards as having utility value as a developmental tool for their professional development. The ECTs spoke of the value of the Standards in providing a language for mentors’ feedback, a structure for their mentoring conversations, and a measure by which they could potentially be reassured of their value to the profession (Adoniou & Gallagher, Citation2017; Hudson & Hudson, Citation2016). This use of the Standards as goals and milestones generally provided a structure for them to make sense of their very broad range of responsibilities as an early career teacher (Adoniou & Gallagher, Citation2017) which can seem overwhelming. Similar findings have been reported in studies with pre-service teachers, with pre-service teachers more likely than their supervisors to see the utility of the Teacher Standards (Loughland & Ellis, Citation2016).

While the use of the Standards to structure mentoring conversations toward standards-aligned development is therefore perceived as assistive in some instances, there remains the concern raised in the research that the Standards alone fall very short of providing a complete representation of who teachers are, and need to be (Goodwin, Citation2021; Larsen & Allen, Citation2021; Mockler, Citation2022). With Standards focused on the observable, measurable, and technicist aspects of teaching (Mahony & Hextall, Citation2000; Mockler, Citation2022), mentoring for other teaching attributes such as critical dispositional development may be overlooked to the detriment of both ECTs and the profession more broadly (Larsen et al., Citation2023).

The standards as cursory

Significant to this study as an extension to Grima-Farrell’s (Citation2019) work on the deployment of Standards in mentoring, some of the mentors and ECTs paid significantly less intentional focus to the Standards as a tool for teacher development and capacity building during mentoring conversations. These teachers felt that despite the obvious expectations that teachers, and ECTs more specifically in this situation, must be able to demonstrate each of the Standards for accountability purposes, they did not consider it either necessary or warranted to specifically frame their mentoring conversations around these descriptors. For many of the participants, this hesitancy to pursue a Standards focused approach was due to the insufficiency of the Standards to represent the realities of teachers’ work. NM1, for example, described the inadequacy of the Standards in the following way:

Yeah, nothing. I mean, I'm aware of them but a lot of the stuff around the professional Standards are either common sense or are kind of overblown. They are documents that don't necessarily connect to the classroom. The classroom is about relationships and relevance, and those things are not represented in the [P]rofessional [S]tandards.

You’re kind of just using the rubric of the Standards, but it doesn't really give you that guidance within emotional intelligence or how to build resilience and teach how to inspire them. You know, so you’re still kind of looking at it from an operational perspective for mentoring, but it is more than just an operational perspective. We're dealing with people, and that side of things is never really reflected in the Standards. … there's a whole other piece that's missing in terms of what mentors need to do. … I think the [S]tandards are really missing the heart of people.

There's a lot of things that it doesn't encapsulate. It doesn't encapsulate entrepreneurship skills, specifically intuition, and managing those in-the-moment things where you make decisions on that … And so if you look at the [S]tandards, I don't see that anywhere in the Standards how to deal with complex situations.

While many of the mentors made only cursory mention of the Standards during mentoring conversations with their ECTs, most ECTs were less critical of the Standards than their experienced counterparts. That said, they concurrently understood the constraints that could come with an overemphasis on these during their mentoring experiences. As N6 (ECT) explained:

The [P]rofessional [S]tandards … I suppose again you could labour the point … try to make those links which is what you have to do in the accreditation process, but the links aren't necessarily there, aren't they? In the daily mentoring conversation, your mentor may not directly mention [P]rofessional [S]tandards. I think it would be forced.

Look, I'm sure they're there, but we probably, in all honesty, haven't given a massive focus to them. But you can definitely draw back on them with, you know, strategies that you're using … They definitely link, but we don’t, you know, say, “This is the one we're focussing on, sort of thing”.

We usually do make that connection to the APSTs. To be honest, they don't play much of a role. I feel like subconsciously they kind of underline everything we do. But there's no really explicit mention to, like, “Oh, we're going to definitely address this one”. It's more tagged on. Which APST does this align with? That part of the conversation ends.

Limitations of this study

The limitations of the study include the sample size and composition. The sample size of 30 participants allows for generalisability at the theoretical level in relation to the regulatory and developmental use of the Standards but not at the level of replicability. This means that we encourage other researchers to further examine the regulatory and developmental use of Teacher Standards as a potentially generative and professionally useful avenue of inquiry.

The composition of the sample is also of note, as all the participants were from independent schools, and this may have influenced the findings. It should be noted that, in 2021, Independent schools accounted for 15.4% of the Australian school population (Australian Bureau of Statistics, Citation2022), and are considered to have more decision-making autonomy (Demas & Arcia, Citation2015) than the larger public and Catholic school systems in Australia. This autonomy may have skewed our findings to a more skeptical view of Teacher Standards than might be expected in a different sector, such as Australian government schools.

Conclusion and implications

In this paper, we have highlighted three key perspectives of ECTs and mentors regarding Teacher Standards as they work together through the mentoring process: that of ensuring ECTs are supported to collect evidence of practice that meets regulatory requirements in order that they may move forward to teacher registration; to develop capacity with the focus areas of the Standards offering a helpful framework for goal setting and mentoring direction; and to be cognisant of the insufficiency of the Standards to prepare ECTs for longevity in a profession that requires more than the Standards represent. These findings have significant implications for teacher mentoring moving forward.

We argue that while each perspective serves an important purpose, in isolation each falls short of providing the full gamut of purposeful mentoring. Instead, we contribute to previous arguments that caution against dual regulatory and developmental responsibilities within the mentoring process (Polikoff et al., Citation2015; Spooner-Lane, Citation2017). However, in the spirit of pragmatism whereby many mentors are charged with this responsibility (Polikoff et al., Citation2015; Spooner-Lane, Citation2017), these findings suggest that mentoring needs to employ a balanced approach to the Standards for regulatory and standards-based developmental purposes. Further, we argue the need for mentoring to go beyond the Standards to experience the kind of deep learning that speaks to the complexity of the teaching profession (Mockler, Citation2022).

We do not however within this paper argue that such recommendations make their way into a set of mentoring standards to which mentors are held accountable as has already occurred in countries such as England with problematic consequences (Jerome & Brook, Citation2020) and a strategy currently under consideration in Australia as reported in the Next Steps: Report of the Quality Initial Teacher Education Review (Department of Education, Skills, and Employment, Citation2022). Instead, we argue that the professional development of mentors be extended to consider the ways in which Standards are and could be employed effectively.

Further research

The regulatory, developmental, and critical address of the Teacher Standards in ECT mentoring as found in this study warrants further study. One hypothesis for this further research could focus on the relative experience of both ECTs and mentors with the use of the Standards in a developmental fashion. Another hypothesis for future research could examine the link between mentor training (Stanulis et al., Citation2019) and the positioning of the Standards in mentoring. Given the ever-expanding responsibilities of the mentor, it would also be timely to investigate the impact of mentors’ role intensification. We encourage future work that can engage with alternative educational contexts to determine how the Standards are positioned among other educators working in Australia and internationally where Teacher Standards are impacting teachers’ work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Aarts, R., Kools, Q., & Schildwacht, R. (2020). Providing a good start. Concerns of beginning secondary school teachers and support provided. European Journal of Teacher Education, 43(2), 277–295. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2019.1693992

- Adoniou, M. (2016). Don't let me forget the teacher I wanted to become. Teacher Development, 20(3), 348–363. https://doi.org/10.1080/13664530.2016.1149510

- Adoniou, M., & Gallagher, M. (2017). Professional standards for teachers—what are they good for? Oxford Review of Education, 43(1), 109–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2016.1243522

- Asih, R., Alonzo, D., & Loughland, T. (2022). The critical role of sources of efficacy information in a mandatory teacher professional development program: Evidence from Indonesia’s underprivileged region. Teaching and Teacher Education, 118, 103824. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2022.103824

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2022). Schools. Retrieved August 12, from https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/education/schools/latest-release

- Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL). (2011). Australian professional standards for teachers. AITSL.

- Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL). (2017). Australian Professional Standards for Teachers. AITSL. https://www.aitsl.edu.au/tools-resources/resource/australian-professional-standards-for-teachers

- Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL). (2023). Environmental scan of mentoring programs: Informing the development of teaching practice through a scan of international and Australian mentoring programs. AITSL. https://www.aitsl.edu.au/docs/default-source/default-document-library/environmental-scan_final.pdf?sfvrsn=6358b53c_0

- Ball, S. J. (2012). Global education Inc. New policy networks and the neoliberal imaginary. Routledge.

- Ball, S. J., Maguire, M., & Braun, A. (2011). How schools do policy: Policy enactments in secondary schools. Routledge.

- Bradbury, O. J., Fitzgerald, A., & O'Connor, J. P. (2020). Supporting pre-service teachers in becoming reflective practitioners using conversation and professional standards. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 45(10), 18–34. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2020v45n10.2

- Braun, A., Maguire, M., & Ball, S. J. (2010). Policy enactments in the UK secondary school: Examining policy, practice and school positioning. Journal of Education Policy, 25(4), 547–560. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680931003698544

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Byrne, D. (2022). A worked example of Braun and Clarke's approach to reflexive thematic analysis. Quality & Quantity, 56(3), 1391–1412. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-021-01182-y

- Collie, R. J., Granziera, H., & Martin, A. J. (2018). Teachers’ perceived autonomy support and adaptability: An investigation employing the job demands-resources model as relevant to workplace exhaustion, disengagement, and commitment. Teaching and Teacher Education, 74, 125–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2018.04.015

- Craig, C. J. (2017). International teacher attrition: Multiperspective views. Teachers and Teaching, 23(8), 859–862. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2017.1360860

- Darling-Hammond, L. (2017). Teacher education around the world: What can we learn from international practice? European Journal of Teacher Education, 40(3), 291–309. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2017.1315399

- Demas, A., & Arcia, G. (2015). What matters most for school autonomy and accountability: A framework paper. The World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/22086/What0matters0m0000a0framework0paper.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Department of Education, Skills & Employment. (2022). Next Steps: Report of the Quality Initial Teacher Education Review. DESE. https://www.education.gov.au/quality-initial-teacher-education-review/resources/next-steps-report-quality-initial-teacher-education-review

- Devos, A. (2010). New teachers, mentoring and the discursive formation of professional identity. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26(5), 1219–1223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2010.03.001

- Dolev, N., & Leshem, S. (2017). Developing emotional intelligence competence among teachers. Teacher Development, 21(1), 21–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/13664530.2016.1207093

- Forde, C., McMahon, M. A., Hamilton, G., & Murray, R. (2016). Rethinking professional standards to promote professional learning. Professional Development in Education, 42(1), 19–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2014.999288

- Goodwin, A. L. (2021). Teaching standards, globalisation, and conceptions of teacher professionalism. European Journal of Teacher Education, 44(1), 5–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2020.1833855

- Goodwin, A. L., Chen Lee, C., & Pratt, S. (2021). The poetic humanity of teacher education: Holistic mentoring for beginning teachers. Professional Development in Education, 49, 707–724. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2021.1973067

- Goodwin, A. L., & Low, E. L. (2021). Rethinking conceptualisations of teacher quality in Singapore and Hong Kong: A comparative analysis. European Journal of Teacher Education, 44(3), 365–382. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2021.1913117

- Grima-Farrell, C., Loughland, T., & Nguyen, H. T. M. (eds.), (2019). The relationship of the developmental discourse of the graduate teacher standards to theory and practice: Translation via implementation science. In Theory to practice in teacher education (pp. 45–61). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-32-9910-8_4

- Heffernan, A., Bright, D., Kim, M., Longmuir, F., & Magyar, B. (2022). ‘I cannot sustain the workload and the emotional toll’: Reasons behind Australian teachers’ intentions to leave the profession. Australian Journal of Education, 66(2), 196–209. https://doi.org/10.1177/00049441221086654

- Hudson, P., & Hudson, S. (2016). Mentoring beginning teachers and goal setting. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 41(10), 48–62. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2016v41n10.4

- Independent Schools Australia. (2022). Autonomy and Accountability. https://isa.edu.au/our-sector/about-independent-schools/autonomy-and-accountability/.

- Ingvarson, L. (2019). Teaching standards and the promotion of quality teaching. European Journal of Education, 54(3), 337–355. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12353

- Jaspers, W. M., Meijer, P. C., Prins, F., & Wubbels, T. (2014). Mentor teachers: Their perceived possibilities and challenges as mentor and teacher. Teaching and Teacher Education, 44, 106–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2014.08.005

- Jerome, L., & Brook, V. (2020). Critiquing the “National Standards for School-based Initial Teacher Training Mentors” in England: What lessons can be learned from inter-professional comparison? International Journal of Mentoring and Coaching in Education, 9(2), 121–135. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJMCE-04-2019-0057

- Langdon, F., Daly, C., Milton, E., Jones, K., & Palmer, M. (2019). Challenges for principled induction and mentoring of new teachers: Lessons from New Zealand and Wales. London Review of Education, 17(2), 249–265. https://doi.org/10.18546/LRE.17.2.14

- Larsen, E., & Allen, J. M. (2021). Circumventing erosion of professional learner identity development among beginning teachers. Teaching Education, 34, 78–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/10476210.2021.2011193

- Larsen, E., Jensen-Clayton, C., Curtis, E., Loughland, T., & Nguyen, H. T. M. (2023). Re-imagining teacher mentoring for the future. Professional Development in Education, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2023.2178480

- Leonard, S. N. (2012). Professional conversations: Mentor teachers’ theories-in-use using the Australian National Professional Standards for Teachers. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 37(12), 46–62. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2012v37n12.7

- Loughland, T., & Ellis, N. (2016). A common language? The Use of teaching standards in the assessment of professional experience: Teacher education students’ perceptions. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 41(7), 56–69. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2016v41n7.4

- Maguire, M., Braun, A., & Ball, S. J. (2015). ‘Where you stand depends on where you sit’: The social construction of policy enactments in the (English) secondary school. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 36(4), 485–499. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2014.977022

- Mahony, P., & Hextall, I. (2000). Reconstructing teaching: Standards, performance and accountability. Routledge/Falmer.

- Mayer, D., Mitchell, J., Macdonald, D., & Bell, R. (2005). Professional standards for teachers: A case study of professional learning. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 33(2), 159–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/13598660500121977

- Miles, R., & Knipe, S. (2018). I Sorta Felt Like I was out in the Middle of the Ocean”: Novice Teachers’ Transition to the Classroom. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 43(6), 105–121. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2018v43n6.7

- Mitchell, D. E., Howard, B., Meetze-Hall, M., Scott Hendrick, L., & Sandlin, R. (2017). The new teacher induction experience: Tension between curricular and programmatic demands and the need for immediate help. Teacher Education Quarterly, 44(2), 79–104. https://www.jstor.org/stable/90010519

- Mockler, N. (2022). Teacher professional learning under audit: Reconfiguring practice in an age of standards. Professional Development in Education, 48(1), 166–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2020.1720779

- Nolan, A., & Molla, T. (2018). Teacher professional learning in Early Childhood education: Insights from a mentoring program. Early Years: An International Research Journal, 38(3), 258–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/09575146.2016.1259212

- Orland-Barak, L. (2001). Learning to mentor as learning a second language of teaching. Cambridge Journal of Education, 31(1), 53–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057640123464

- Polikoff, M. S., Desimone, L. M., Porter, A. C., & Hochberg, E. D. (2015). Mentor policy and the quality of mentoring. The Elementary School Journal, 116(1), 76–102. https://doi.org/10.1086/683134

- Power, M. (2009). The risk management of nothing. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 34(6-7), 849–855. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2009.06.001

- Richter, D., Kunter, M., Lüdtke, O., Klusmann, U. a., Anders, Y., & Baumert, J. (2013). How different mentoring approaches affect beginning teachers’ development in the first years of practice. Teaching and Teacher Education, 36, 166–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2013.07.012

- Ryan, M., & Bourke, T. (2018). Spatialised metaphors of practice: How teacher educators engage with professional standards for teachers. Critical Studies in Education, 59(2), 167–186. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2016.1185641

- Sachs, J. (2016). Teacher professionalism: Why are we still talking about it? Teachers and Teaching, 22(4), 413–425. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2015.1082732

- Sahlberg, P. (2010). Rethinking accountability in a knowledge society. Journal of Educational Change, 11(1), 45–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-008-9098-2

- Shanks, R., Attard Tonna, M., Krøjgaard, F., Paaske, K. A., Robson, D., & Bjerkholt, E. (2022). A comparative study of mentoring for new teachers. Professional Development in Education, 48, 751–765. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2020.1744684

- Spooner-Lane, R. (2017). Mentoring beginning teachers in primary schools: Research review. Professional Development in Education, 43(2), 253–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2016.1148624

- Stanulis, R. N., Wexler, L. J., Pylman, S., Guenther, A., Farver, S., Ward, A., Croel-Perrien, A., & White, K. (2019). Mentoring as more than “cheerleading”: Looking at educative mentoring practices through mentors’ eyes. Journal of Teacher Education, 70(5), 567–580. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487118773996

- Thompson, G., Mockler, N., & Hunt, A. (2022). Making work private: Autonomy, intensification and accountability. European Educational Research Journal, 21(1), 83–104. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474904121996134

- Vaitzman Ben-David, H., & Berkovich, I. (2021). Associations between novice teachers’ perceptions of their relationship to their mentor and professional commitment. Teachers and Teaching, 27(1-4), 284–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2021.1946035