ABSTRACT

This study explores the challenges of students who identify as LGBTQ+ in six secondary schools in the south of England. Drawing on survey data from five schools (n = 257), and focus groups in six schools with 33 students, this study looks at the way that school culture and school climate operate and how these impact on the experiences of LGBTQ+ youngsters. This paper examines how school culture and climate serve to challenge, and occasionally affirm, LGBTQ+ identities, and how LGBTQ+ youngsters try to mediate the challenges raised by the culture and climate within schools. The comparison between schools shows that some provide more inclusive environments, but this is often at the level of the school climate, rather than the overall culture. Generally, schools should be looking to create more inclusive school cultures that are affirming of young people’s LGBTQ+ identities.

Introduction/context

You're just not real.

In the UK, the removal of Section 28 of the 1988 Local Government Act and the introduction of the 2010 Equalities Act showed progress for the LGBTQ+ community, yet recently, the UK has fallen in an ILGA Europe-wide ranking of LGBTQ+ rights from 1st in 2015 to 14th (Brooks, Citation2022). In particular, both the CoE (Citation2021) and Stonewall (Citation2023) highlight the deteriorating situation for the transgender community in the UK; this is seen in the Conservative government’s failure to extend a ban on conversion practices to transgender people, abandoning promised reforms to gender recognition, as well as attacks by some Conservative MPs on schools that affirm trans students’ identity (Cates, Citation2023, Column 504).

The situation in schools for LGBTQ+ youth generally does appear to be challenging. Although some studies (e.g. McCormack & Anderson, Citation2010) present an improving picture for LGBTQ+ youngsters, various international large-scale surveys highlight numerous challenges (e.g. Kosciw et al., Citation2022; Peter et al., Citation2021; Stonewall, Citation2017; Ullman, Citation2021). Together with detailed smaller-scale qualitative studies (e.g. Harris et al., Citation2021; Kjaran & Jóhannesson, Citation2013), this research consistently shows LGBTQ+ students are victimised by their peers, are more prone to self-harm or attempt suicide, often have lower levels of school attainment and suffer from mental health issues. Research on the experiences of LGBTQ+ students shows there is little room for complacency. To gain a better understanding of the experiences of LGBTQ+ students, this study examines issues around LGBTQ+ identities in secondary schools, the extent to which school culture and school climate affirm students’ sense of self, and how this differs between schools.

Literature review

Firstly, we set out the theoretical framework for this paper, followed by issues around identity development and LGBTQ+ identity development. Finally, the review focuses on the differences between school climate and school culture.

Theoretical framework

This research draws on queer and trans-informed theory, and particularly on concepts related to hetero- and cisnormativity, framing how sexuality and gender identities are policed in school. Both Ingrey (Citation2018) and Wozolek (Citation2019) acknowledge that defining queer theory is challenging, but agree it can allow for deconstructing and disrupting binary notions of sexuality and gender, and critiques the systems that privilege particular forms of being. However, while there are links between queer and trans theories in terms of critiquing supposed “normal” identities (see Love, Citation2014), as Martino and Cumming-Potvin (Citation2018) argue, queer theory fails to fully address gender complexity as its inappropriate application can be prejudicial to trans and non-binary persons’ lived experiences and can be potentially exclusionary (see also Martino et al., Citation2022b).

In this study, understanding the concepts of hetero- and cisnormativity, as well as heterosexism and cisgenderism, are crucial in making sense of the ways in which LGBTQ+ students experience school. Heteronormativity is where heterosexuality is perceived to be the unquestioned social norm, where heterosexual values and ways of being are hegemonic and encouraged (Kjaran & Jóhannesson, Citation2013; Yep, Citation2002). Heterosexism, i.e. cultural, social, legal and organisational practices, is the mechanism through which heteronormativity is enforced. Cisnormativity privileges binary notions of gender, and is based on the idea that everyone is (or should be) cisgender, i.e. someone’s gender identity should align with their gender assigned at birth (Berger & Ansara, Citation2021; Horton, Citation2023). Cisgenderism is “the cultural and systematic ideology that denies, denigrates or pathologizes self-identified gender identities that do not align with assigned gender at birth” (Lennon & Mistler, Citation2014, p. 63). Kennedy (Citation2018) develops this further, using the term “cultural cisgenderism”, which is again seen as ideology, albeit one that is tacitly held in society generally, (in contrast to transphobia, which is seen as an individual attribute), and which “represents a systemic erasure and problematizing of trans’ people and the distinction between trans’ and cisgender people. It essentializes sex/gender as biologically determined, fixed at birth, immutable, natural and externally imposed on the individual” (p. 308). Consequently, schools, as public spaces, can readily become places where societal norms around sexual and gender identity are (often unconsciously) expressed and enforced through various organisational, instructional and interpersonal processes (Martino et al., Citation2022a; Ullman, Citation2014). LGBTQ+ identities can easily be invisible and silenced within schools, which, by default, reinforce hetero- and cisnormative ways of being (Allan et al., Citation2008).

Identity development and LGBTQ+ identity development

Creating a cohesive, stable sense of identity is crucial in someone’s personal development and for promoting positive mental well-being (Brennan et al., Citation2021). Our understanding of this process has shifted from an essentialist understanding of the self, where there is an innate sense of identity, towards a model where identity is affected by the social-cultural context (Schachter, Citation2005), implying that identity development is complex and unique to individuals, whether or not they are LGBTQ+. Yet, identities are constrained by what is deemed socially acceptable; regimes of power define the boundary between what is considered normal and deviant, which are then socially policed (Weir, Citation2009). This makes it important to understand the ways in which hetero- and cisnormativity operate at the school level and their impact on LGBTQ+ identities. These identities, in particular transgender identities, provide a disruptive element in understanding identity development, which has led Butler (Citation1999) to argue that gender is based around socially produced, normative perspectives, and gender is therefore performative.

The literature on LGBTQ+ identity development has also shifted away from a stage model of identity development, and has been replaced by a lifespan approach, reflecting a socio-cultural model, where identities are seen as fluid and renegotiated as contexts change, such as schools, change (Bilodeau & Renn, Citation2005). Within this approach, particular processes that LGBTQ+ youngsters experience, which differ to those of their non-LGBTQ+ peers, have been identified, for example Hall et al. (Citation2021, p. 1) include “becoming aware of queer attractions, questioning one’s sexual orientation, self-identifying as LGB+, coming out to others”, among others, although they emphasise that individual trajectories vary. Identifying as LGBTQ+ is frequently associated with significant mental health issues (e.g. Meyer, Citation2003).

Members of the LGBTQ+ community are subject to “minority stress” (Meyer, Citation2003), and can experience stigma and macro and microaggressions in schools (McBride, Citation2021; Travers et al., Citation2022). Horton (Citation2023) also uses the term “gender minority stress” to highlight some of the specific stresses to which trans children are subject. These stresses are either external (i.e. what others do to members of the LGBTQ+ community), expectations of stressful events, or the internalisation of negative social attitudes.

The importance of school climate and school culture

The literature does not provide for consistent definitions of school culture and school climate. Some authors use the terms interchangeably (e.g. Barnes et al., Citation2012). Others, such as Van Houtte (Citation2005), see school culture as a sub-set of school climate, whereas some, for example Schoen and Teddlie (Citation2008), see school climate as a level within school culture. Within the LGBTQ+ literature, several simply use climate when referring to all aspects of LGBTQ+ students’ experiences in school (e.g. Kosciw et al., Citation2022; Peter et al., Citation2021), whereas others conflate culture and climate when discussing cisgender norms and values in schools (Ullman, Citation2014).

However, a closer inspection of the literature suggests that general agreement about distinctions between the two concepts does exist. School culture is generally referred to as norms, shared values, behaviours and expectations, often reflected in stories, icons and rituals that characterise an organisation (Barnes et al., Citation2012). School climate is often linked to feelings of safety and acceptance, the quality of relationships and patterns of behaviour within an organisation (Cohen et al., Citation2009).

We draw on Payne and Smith’s (Citation2013) distinction between culture and climate. School culture reflects the norms and values in a school, through mechanisms such as use of gendered spaces, curriculum and enforcement of behavioural policies (which are seen to be largely hetero- and cisnormative). School climate refers to the everyday interactions within a school environment and whether those generate feelings of safety, connection and belonging. It is perfectly possible that everyday “niceness”, i.e. a positive school climate, may mask a negative school culture (Rawlings, Citation2019).

The precise interplay between climate and culture is, however, not always clear. The extent to which negative behaviours reflect an individual or institutional set of values may not be obvious but plausibly suggests that persistent and pervasive behaviours within a school environment are indicative of wider socio-cultural assumptions. It is also possible that individual negative behaviours go unchallenged because they are not seen as a threat to the socially-accepted norms within an institution. Furthermore, culture is malleable, and schools can develop different cultures and support different climates, so the experiences of LGBTQ+ students, within and between schools, may not be universal. This may account for some of the positive experiences identified in certain studies (e.g. McCormack & Anderson, Citation2010), which makes it important to identify both positive and negative aspects of school culture and climate, in order to identity ways in which LGBTQ+ lives can be normalised.

The present study

The literature surveyed suggest that school culture and climate do have a major impact on the experiences of LGBTQ+ youth, and this can be extremely negative. Less well explored, is the impact that schools have on LGBTQ+ students’ sense of self. Queer and trans-informed theories, allied with the concepts of hetero- and cisnormativity, provides a lens through which school culture and climate can be critiqued. Trying to define and assert an identity that is at odds with more widely-accepted social norms, is likely to present a challenge for LGBTQ+ youth. This study contributes to the literature by examining the extent to which school culture and climate provide affirmative experiences for LGBTQ+ students’ identity.

Research design

This study used a mixed methods approach to explore school culture and school climate in six secondary schools in England, and the impact of these on LGBTQ+ students’ sense of self. The study draws on focus groups in six schools and five sets of survey data (one school did not return surveys). The research design followed a qualitative priority method (QUAL+ quant) in which the primary data came from focus groups, with complementary survey data (Morse & Niehaus, Citation2016).

Participants

Around 100 schools, located in southern England, were invited to participate; six agreed. Reasons for non-participation were not collected. The schools involved were secondary schools for students aged 11-18. The schools were similar in size but differed considerably regarding students who claimed free school meals, a proxy measure for socioeconomic (SES) levels, and those who had English as an additional language (reflecting the multi-cultural nature of some schools, like Ash, Elm and Willow) (see ). Further SES indicators can be seen in the IDACI and the Indices of Multiple Deprivation ranking, indicating that Ash and Maple were lower SES schools, although middle-ranking compared to England overall; other schools were in more affluent areas. All schools were co-ed, with the exception of Elm, a single-sex school for boys. Both Elm and Willow were also grammar schools, i.e. students are academically tracked at the age of 11.

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of the sample schools.

Data collection

Data collection was via focus groups with LGBTQ+ -identifying students (total across six schools, n = 33), with survey data collected from LGBTQ+ -identifying and non- identifying students in Year 8, 9 and 10Footnote1 (n = 257). A liaison person in each school organised a focus group of six to eight students. gives details of the numbers in each focus group, whilst shows how they identified in terms of sexuality and/or gender identity. and give details of who completed the surveys in each school, by year group and self-identification as LGBTQ+, and whether they are questioning their identity. Although there are few statistics on the numbers of the population who identify as LGBTQ+, (see, for example, ONS, Citation2022), around 12% of the students who completed the survey identified as being LGBTQ+, with a further 12% questioning their identity. The liaison person also arranged for the surveys to be done, ideally with around 60 students, chosen from Years 8-10. Elm School provided no survey responses despite repeated attempts to obtain these.

Table 2. Focus group participants.

Table 3. Self-identification of those students involved in focus groupsTable Footnotea.

Table 4. Crosstabulation: Survey data by school and year.

Table 5. Crosstabulation: Survey data presented by school and LGBTQ+ identification.

Focus groups were adopted so that participants could talk within a supportive environment of known peers. They were conducted in school, lasting 45–60 min. In Ash, Elm and Oak Schools, no teacher was present during the focus groups, whereas the other three schools insisted that a teacher be present for safeguarding reasons; nevertheless, this did not seem to inhibit students from making critical comments about their schools.

The survey contained sociodemographic questions, including sexual orientation and gender identity items, and closed-ended items aimed at assessing school climate and culture from a student perspective. A deep dive into survey results is beyond the scope of this paper and will be published elsewhere. When relevant, however, they are cited as complementary to the focus group data.

Quantitative measures

School climate. Six items were created to measure how LGBTQ+ youth are treated by their peers in everyday actions, based on issues highlighted by Payne and Smith (Citation2013) and Rawlings (Citation2019). Students responded using a 5-point frequency scale (5 = frequently, 1 = never); scores were reversed so that lower scores represent a more negative perception. Example items include: “LGBTQ+ students at my school have their things stolen or damaged” and “Students use the word ‘gay’ in a negative way at my school” (α = .88; ω = .88).

Relation with school peers. Students responded to five items using a 5-point scale (5 = strongly agree to 1 = strongly disagree). Example items include “Other students here like me the way I am” (from Goodenow, Citation1993), and “Even around the students I know at school, I don’t feel that I really belong” (from Lee et al., Citation2001) (α = .81; ω = .81).

Teacher support specific to LGBTQ+ students. A single item was used to measure teacher support of LGBTQ+ students, “LGBTQ+ student peers at my school receive positive encouragement from teachers when they come out to them”.

Adults at school care about me. A total of 5 items made up this scale (5 = strongly agree to 1 = strongly disagree). Example items include: “Generally, the adults in my school respect my opinion” (from Mayberry et al., Citation2009), and “The teachers here respect me” (from Goodenow, Citation1993) (α = .83; ω = .84).

Data analysis

Although queer and trans-informed theories do offer a lens to identify and disrupt hetero- and cisnormative binaries and practices, there is a danger of simply creating another homogenising perspective, where the experiences of LGBTQ+ students (or other groups) are “lumped together”. To counteract this, when referring to quotes, we have included the details of how individual students identify. Our stance is empathetic to LGBTQ+ youngsters given their marginalised status. We felt it was important to treat their voices with respect, whilst maintaining a critical stance, not simply taking comments at “face value” but reviewing responses and placing them within a conceptual framework (Gerson & Damaske, Citation2021). In this case, the framework drew on the concepts of school culture and climate, and hetero- and cisnormativity. Both positive and negative experiences and views were sought.

The focus group data was recorded, transcribed, and underwent two rounds of inductive coding. Firstly, process coding using gerunds was adopted (Saldaña, Citation2016), followed by a further round of coding to refine key themes. Process coding allows actions to be more readily identified, with these actions revealing the way culture and climate operate in the participating schools to enforce or challenge hetero- and cis norms.

The use of quantitative data does homogenise responses, but highlights patterns in the data, that help to contextualise the qualitative findings.Footnote2 Descriptive statistics ( and ) and between-groups analysis of variance (ANOVA) were calculated using SPSS, and where relevant, are referred to in the text.

Ethical considerations

Obtaining consent for focus-group participation presented some issues. LGBTQ+ students can be hard to identify, yet listening to the experiences of those who are out, as well as those whose “outness” is more selective is important. Ideally, participants would be students who were out at home as well as school. However, those out in school, but not home, were identified by the school as being particularly keen to participate, and there is an ethical argument that their voices also need to be heard (Smith & Schwartz, Citation2019). Where students were out at home, consent to participate was provided by parents or carers, but where students were not, but wished to participate and schools were willing to permit this, consent to interview students was school-granted. Although focus group participation meant some students recalled distressing incidents, either a member of staff was present or information was relayed to the school’s liaison person for the necessary support. Focus group participants did express gratitude for the opportunity to share their experiences with the research team.

Findings

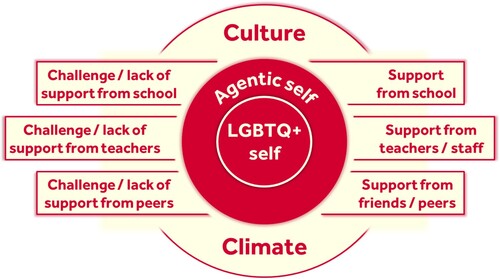

The initial coding of the data indicated that lots of things were “being done” to the students interviewed; including being insulted, ignored, and dismissed. There were also issues with support for these students. Collectively, these were seen as “challenges to identity”, which was divided into sub-categories, which were indicative of school culture and climate and the extent to which hetero- and cisnormativity was enforced. Supportive issues were also identified, and divided into two themes: the “agentic self”, where LGBTQ+ students took steps to protect/support their identity, and “external support for identity”, both of which had sub-categories.

Challenges to identity

Challenges from peers

This category was seen as indicative of School Climate (see the quantitative measures section), as the focus was on the daily interactions that LGBTQ+ students had with their peers. Survey data showed significant differences between schools [F(4,247) = 6.61, p < .001]. For example, students reported a significantly more positive School Climate at Willow School (M = 2.18), whilst Maple School (M = 3.06) scored least well on this scale. Further analysis also showed significant differences across all schools when comparing the experiences of students who identified as LGBTQ+, with those who were unsure, and those who were non-LGBTQ+ [F(2,245) = 20.99, p < .001], when not taking into account school differences. Students who were part of the LGBTQ+ community generally reported a more negative School Climate.

These students also reported significantly more negative Relationships with School Peers [F(2,250) = 20.98, p < .001], a measure for which differences between schools were also significant [F(4,252) = 3.57, p = .008]. Regarding the Relationships with School Peers variable, Willow students’ answers implied an overall best relationship with peers, and Maple school students again responded the most negatively (M = 3.78; M = 3.23 respectively), when taking into account only the answers of LGBTQ+ -identifying and questioning students (although the sample size does not allow for ANOVA comparisons within schools, but see Appendix).

Focus group data also presented a positive perspective from students at Willow School, and a negative perspective from students at Maple School. The LGBTQ+ students in Elm School (which did not provide any survey data) also reported a very positive picture, similar to that in Willow School. In both cases, students reported inappropriate use of the word “gay” by some peers, but in other schools, more significant issues were raised. Several students from the range of LGBTQ+ identities reported that there was simply little acceptance of who they were from either individuals or groups of students:

I got told that this kid said there are only two genders. And if you’re not, if you’re any other genders, you’re just not real. (Maple School, student 4, bisexual)

I came out last year, and then I moved to a different class because my class was not happy with that … But then in that class, in one of the lessons people were like, starting to say, oh, no, being gay goes against my religion. Like, ‘that’s disgusting’. (Maple School, student 2, bisexual, questioning non-binary)

Walk[ing] around on my own and walking home from school can be quite scary and to school. Because I’ve transitioned fully whilst in school, so people have known me as who I was before, have seen the transition. And I feel that’s left me in a lot more of an unsafe place. (Ash School, student 4, gay, trans man)

Someone’s told me they know where I live. And they’re gonna, like, hurt me. (Maple School, student 2, bisexual, questioning non-binary)

I had been followed, while walking out of school, and had people call slurs. I was on my own … and they, er, on one occasion surrounded me and were throwing things at me. (Sycamore School, student 5, queer, trans man)

A while ago, I had a … really bad mental health day, and I had been actively on the phone to a helpline and a group of students started chucking bottles at me and yelling names. I actually ended up in hospital later that night. But it’s just how bad it’s gotten. (Sycamore School, student 4, bisexual, non-binary)

Worryingly, these more extreme examples involve those whose identity challenges both hetero- and cisnormativities. Such experiences from some peers serve as a rejection of identity or a threat. It was notable that trans students were more likely to be physically threatened having visibly transitioned socially whilst at school.

Challenges/lack of support from teachers

The survey data on the Adults Care About Me measures presented a similar picture to the School Climate and Relations with Peers when comparing schools. There were significant differences between schools, with Willow and Maple Schools again presenting the extremes [F(4,251) = 3.58, p < .001], with students at Willow School being more positive. However, when looking at differences between groups of students, there was no statistical difference between students who identified as LGBTQ+ and those who did not [F(2,249) = 0.36, p = .70]. This may suggest that teachers within schools treated all students similarly, despite their gender and sexual identities. Nevertheless, a closer look at the qualitative data shows that particular teachers were LGBTQ+ allies, whereas others were seen as unhelpful or hostile. The measure Teacher Support Specific to LGBTQ+ Students did not show significant differences between schools [F(4,244) = 1.58, p = .20], but did between those who identified as LGBTQ+, were unsure, and those who were not [F(2, 240) = 3.65, p = .027].

Focus group data showed that Willow students had more positive perceptions of adult support and Maple School students more negative. The survey data for the other schools did not reflect the sentiment from the focus groups. For example, the survey data from Ash and Sycamore Schools was quite positive, but the students who were interviewed highlighted concerning issues with particular staff:

My friend who is nonbinary has had both Miss. P. and Mr. M., and they have received, like abuse from both teachers like directly in front of quite a few people. (Ash School, student 2, bisexual)

Mr. S. told Charles that his dead name didn’t matter. And he’s gonna use it because he can. (Ash School, student 4, gay, trans man)

I had a lot of people and still have a lot of people, including teachers, who, like refuse to use the correct pronouns. (Sycamore School, student 5, queer trans man)

There was a certain incident with a teacher. I think it was in year seven or eight. I kind of told them that I was okay with like, they/them/she pronouns. And they kind of tried to disprove that in a sense. And it kind of just made me think, why do you think you have influence on my identity and why you as a teacher, why do you think you can say that? (Sycamore School student 3, pansexual, non-binary)

What is worrying is these cases involve those who are challenging both the hetero- and cisgenderist norms, and show some teachers are actively refusing to recognise or deliberately challenging students’ LGBTQ+ identities. This reflects a power imbalance, with an authoritative teacher figure imposing views on students trying to establish their identity. Some students recognised their own vulnerabilities in this process and felt that staff should be supportive, rather than antagonistic. Although pronoun usage is an issue that would appear to affect trans and non-binary students more, other focus group participants, whose identity challenged heteronormality, had also chosen to use pronouns to queer their gender identity (even where they were not overtly questioning their gender).

These interactions reflect issues relating to school climate, as they predominately reflect individual relationships between staff and students. However, relations with staff do spill over into school culture when it comes to implementation of things, such as behavioural policies.

Challenges/lack of support from school

In several focus groups, students complained about the ineffectiveness of school behavioural policies in dealing with bullying, particularly in Ash, Maple, and Sycamore Schools:

It feels very performative, performative. As someone who’s had to complain on many occasions, about people being homophobic towards me, and calling me a faggot, and stuff like that. My experience is that no action is ever taken aside from detentions or IERs [exclusions], which, as someone who’s had a detention is very, very easy to skip by just not going. (Ash School, student 5, omnisexual)

So, one of the examples is during maths, I was called the F slur. And I said to the teacher, ‘Miss, this guy’s just called me a slur’. And she was like, the teacher was like, oh I’ll put it on SIMS (School Information Management System), she didn’t even react to it either. (Maple School, student 5, pansexual)

I’ve had several instances where I’ve asked to be removed from classrooms due to behaviour of other students, and it’s taken months and months of missing lessons, just to get put in another room. (Sycamore School, student 2, aromantic asexual, agender)

Students pointed out that racial slurs would be treated far more seriously in their schools. The students felt this signified a heteronormative and cisgenderist culture, where homo- and transphobia was seen as acceptable. In Maple School, students recounted episodes where staff suggested homo- and transphobia were “opinions”, something students were entitled to express, unlike racism.

Use of gendered spaces, especially access to toilets and changing rooms were causes for complaint in Ash and Sycamore Schools. Uniforms were less of an issue but in Sycamore School reflected gender norms, whilst the lack of openly out teachers as role models, the use of boy/girl seating plans, and the use of deadnames on school systems reinforced hetero- and cisnormative binaries, negating LGBTQ+ identities.

The lack of curriculum representation was also noted in Ash, Maple, Oak and Sycamore Schools. Students complained that Personal, Social and Health Education (PSHE) and sex education lessons reflected hetero- and cisnormative notions. The survey data also highlighted the curriculum as an area where there were significant differences, not only between schools, but also in how negatively LGBTQ+ students experienced the curriculum.

Even in Elm and Willow Schools, which were the most positive in terms of the focus groups, there were issues around the normalisation of LGBTQ+ identities. Willow School serves a multi-cultural and multi-faith community, which the students acknowledged was an issue when it came to accepting LGBTQ+ identities, especially for males:

I think it's also the difference between genders, like a couple of my friends, especially the male ones … they have a lot … harder time coming to terms with the fact that they might be part of the LGBTQ. And also, with coming out, my female friends don’t have that, that they have quite close-knit friend groups, they’re very accepting. But my male friends are constantly questioning … how their friends are going to react. (Willow School, student 7, bisexual)

Elm School, which was a single-sex school for boys, also had an underlying hetero- and cisnormative culture. A school slogan, “creating good men”, caused a great deal of laughter when discussed, as the students felt they were not living up to the school’s expectations, either in terms of sexuality or gender identity. However, issues around gender identity appeared particularly acute; one of the students recounted the struggles encountered by the first student who came out as trans whilst at school:

When they amended the school uniform policy, that was a big hassle … we have trans students and obviously, the trans students want to express themselves how they want to. So, I think … the old student who used to come here, she, she said that the headmaster had agreed for her to come to school in a skirt and then like a week before the term began, went completely against her and was like, no, you have to come in wearing trousers. (Elm School student 5, queer, genderqueer)

Overall, both the focus group, and some of the survey data, show that many LGBTQ+ students encountered various direct or indirect challenges to their sense of identity, as a result of both the heteronormative and cisgenderist nature of the schools’ cultures and climates. The severity of the issues varied by school, but all the students could identify challenges within their contexts. The most direct challenges in some schools came from peers, reflecting issues around school climate, whilst the hostility and indifference in some schools from staff did little to affirm these students’ sense of self. Consequently, it seems that schools, in terms of climate and culture, were difficult places for these students to be comfortable as themselves.

Agentic self

Issues around power were identified, as lots of things were “being done” to the LGBTQ+ identifying students, highlighting their powerlessness, for example, when confronted by inadequate implementation of behavioural policies or staff attitudes. However, the students exerted agency in some ways, as a means of mediating attacks on their identity, such as through support for each other:

That’s the thing we’ve sort of, because we haven’t really got much support in school, we’ve made ourselves our little support group with the group of us and we sort of, we handle things very sensitively. (Sycamore School, student 4, bisexual, non-binary)

And you can like, if you’re the same size, someone will probably give you one of their items [sharing clothes with trans student]. (Maple School, student 2, bisexual, questioning non-binary)

It’s just like a happy little family who will just eat lunch and just talk about what we need to. (Oak School, student 1, gay)

Another means of exerting some autonomy was through small acts of resistance:

We’re standing up to start correcting people’s pronouns, like I didn’t do before, because I was so nervous that I would get in trouble. But you know, I don’t even care because it’s the teacher’s problem and not mine. (Sycamore School, student 1, queer)

However, the students were more likely to avoid situations for their own safety:

I’ve missed a lot of lessons that are important, because I’ve avoided students, because I don’t know what they’re gonna say, I don’t know what they’re gonna do. (Sycamore School, student 4, bisexual, non-binary)

I’ve had to fake sick. Yeah. (Maple School, student 2, pan/bisexual, trans man)

Another strategy was around disclosure and the selective nature of the choices the students made. This could be who they chose to come out to, i.e. friends, staff, and family. Also, although each school had an LGBTQ+ group that met regularly, in some cases, the group was secret, to prevent students being outed and being victimised:

Yeah, it’s secretive because we don’t want homophobic people coming in. (Willow School, student 5, lesbian)

Another reason for selective disclosure was linked to the nature of the school. One of the trans students interviewed at Elm School wanted to go to a grammar school, but the two grammar schools in the area were both single-sex, so she had a dilemma of “do I go to the one where I won’t fit in later? Or do I go to the one where I don’t look like I fit in now?” (Elm School, student 4, queer trans woman). She chose to attend the boys’ school and delayed coming out for several years to ensure she would not be asked to leave.

Students also demonstrated agency by educating others and supporting the wider LGBTQ+ community. In four schools, students gave examples of how they had prepared materials to be used in assemblies or tutor groups to educate their peers about LGBTQ+ matters. However, in Maple School, the assembly actually caused more trouble as a number of students openly objected to the materials, whilst students in Ash School were aware many teachers simply ignored materials produced. Support for the wider community was either through student-led fundraising for LGBTQ+ charities or LGBTQ+ students approached by questioning students for support.

Although these attempts to protect or assert LGBTQ+ identity are positive, they still reflect negatively on the wider school climate and culture. The secrecy around some LGBTQ+ groups, or students feeling compelled to skip classes, highlight the challenges of existing within hetero- and cisnormative institutions.

External support for identity

This theme mirrored the categories in challenges to identity, namely teacher support, school support and peer support. In each school, students were able to identify teachers who were either role models or sources of support, many of whom were spoken of with great affection, as shown in this exchange between students at Willow School:

Miss H is like a cool aunt and then like, Miss L is like a cool older sister (Student 2, lesbian).

Miss H is the type of aunt I aspire to be in my life, even if it’s just to your cat. (Student 3, lesbian)

A teacher did sort of casually mention like my, she’s like my wife. And so at least then it’s good to know that teachers are comfortable, just casually revealing that. (Elm School, student 4, queer, trans woman)

The curriculum was also another source of wider school support if it reflected students’ identities. This was most commented upon in Willow School:

Obviously, there are like posters around the school like this person who was an artist and this person who was a writer was gay or lesbian or trans. (Willow School, student 2, gay, queer)

As for our curriculum for history, what we’re learning in history, and the last topic is about human rights. And I know that’s gonna cover LGBT so I think it’s good how they’re teaching us. (Willow School, student 3, lesbian)

Support from peers was also highlighted in a few instances. In Willow School, one of the students described an incident in a French lesson when their peers:

… looked at my [rainbow] badge and said, ‘What does that mean? Does that mean you’re queer?’. I was like, ‘yes’ … And they looked at me and they just asked me what my pronouns were and how I identify that that was just so touching it made my day. And then they started going on saying sentences saying oh they are blah blah blah. And then they did sentences about me using the different pronouns I identified with and that was just so sweet and heart felt. (Willow School, student 1, pansexual)

Two things stand out from the data regarding external support. Firstly, the paucity of comments highlighting positive points about school culture. Secondly, nearly all the positive comments were provided by focus group participants at Willow, Elm, and to some extent Oak. Students at Ash, Maple and Sycamore were far more negative and struggled to recall positive experiences, apart from with particular teachers.

Discussion

Payne and Smith (Citation2013) and Rawlings (Citation2019) argue that the need to examine both school culture and school climate appear to be supported by this study's findings. The results show a clear distinction between schools and the type of culture and climate that exists, which in turn appears to shape how young people experience their LGBTQ+ identity. There are schools, for example Elm School, where a positive school climate exists in contrast to an underlying school culture that projects hetero- and cisnormative values. Similarly, in Willow School, according to focus group data, the school climate seems generally supportive. Nevertheless, the secrecy around the LGBTQ+ lunchtime group, challenges faced by male students in coming out, and the significant difference between the perception of non- and LGBTQ+ -identifying students regarding said climate suggest there is work to be done on creating a more openly-supportive culture.

Although the overall findings for the other schools are more mixed, with the survey data and focus groups from Ash, Oak and Sycamore Schools presenting slightly different realities, there does seem to be a disconnect between the perceived experiences of non-LGBTQ+ students and their questioning or LGBTQ+ peers regarding the school climate measure. In Willow, Sycamore and Maple Schools, the LGBTQ+ students highlight a significantly more negative experience compared to their non-LGBTQ+ peers, suggesting that part of the problem, at least in these schools, is the failure of the majority group to grasp the struggles that exist for their LGBTQ+ peers. This seems also reflected in data on the school culture, highlighting particular issues around implementation of behavioural policies by staff and curriculum concerns. The findings from Maple School present a consistently negative, hostile experience in relation to both climate and culture for LGBTQ+ students, regarding both survey and focus group data. Overall, the findings reinforce other studies that show school culture is essentially heterosexist and cisgenderist (Horton, Citation2020; Kjaran & Jóhannesson, Citation2013; Yep, Citation2002), although perceptions of school climate vary by institution.

Reasons for differences between schools are not entirely clear as that was not the main focus of the study. But as mentioned, both Elm and Willow schools serve more affluent areas, and are academically selective, potentially indicating that high levels of academic attainment and SES may help support greater levels of LGBTQ+ -acceptance. Maple and Ash are in relatively less-wealthy areas, and the students there report quite negative experiences. Oak and Sycamore do, however, reside in higher SES areas, yet LGBTQ+ students reported quite a mixed experience. The mixed nature of the findings suggests that, although there is a wider societal context in terms of the way LGBTQ+ issues are portrayed, each school is individually situated and shape and define their particular responses to these wider matters. However, it would seem that the quality of LGBTQ+ students’ experiences currently depends more on the support of individual teachers, rather than the way schools operate at an institutional level. The lack of institutional support is a significant issue (Martino et al., Citation2022a).

These experiences of school climate and culture appear to impact on LGBTQ+ students’ sense of identity. In terms of school climate, the verbal abuse and, in some cases, physical intimidation, illustrate a distinct lack of respect for LGBTQ+ identities from pockets of the student body and individual teachers. Drawing on a socio-cultural model of identity development (Schachter, Citation2005; Weir, Citation2009), students face a considerable assault on their sense of self at the micro-level, through a series of microaggressions (McBride, Citation2021). The school climate can present LGBTQ+ identities as less worthy of care, for example through the lack of access to toilets and changing spaces, as this requires “extra effort” (Airton, Citation2018) from the non-LGBTQ+ population to address (see also Horton, Citation2020, Citation2023). For Weir (Citation2009, p. 550) this would also reflect a Foucauldian view where identities are “produced and enforced through relations of power”.

School culture presents a challenge at the macro-level. Issues around school climate become a cultural issue when they are persistent and pervasive. For example, the failure of individual teachers to implement the school behavioural policy may reflect individual attitudes, but consistent school-wide policy failings are more likely a cultural issue, where LGBTQ+ issues are widely ignored. As many students noted, racist abuse would not be tolerated in schools, yet the use of slurs against the LGBTQ+ community seem to be somehow acceptable, consistent with Horton’s (Citation2020) findings. This reflects concerns raised by Hoffman et al. (Citation2001, p. 8) that homophobia remains “the one bigotry that remains acceptable”. As Jones (Citation2014) argues, hierarchy in language, i.e. which slurs are considered more objectionable, reflects on how seriously issues are addressed. In looking at school culture in this study, there seems a general sense of “not caring” about LGBTQ+ students, whose identities are seen as “not real”. A culture of (in)visibility can contribute to this – i.e. few adult role models in school, a trend towards students feeling uncomfortable disclosing their identity or secretive LGBTQ+ support groups. This invisibility means non-LGBTQ+ students are not forced to engage with the existence of their LGBTQ+ peers, potentially perpetuating a veil of ignorance around LGBTQ+ matters and generating more “minority stress” (Meyer, Citation2003). Overall, it would seem that if identity is about creating a stable, coherent and cohesive sense of self (Chen et al., Citation2012), the negativity many LGBTQ+ students experience presents a threat to these students’ identity.

LGBTQ+ students are able to “cushion” some negative experiences through a degree of agency and resilience (Travers et al., Citation2022). shows what this may look like in terms of a model of identity development. However, the data from this study suggests that the hetero- and cisnormativity embedded in school climate and culture come across as more prevalent than the degree of support that LGBTQ+ students receive. This is not to underestimate the importance of the supportive work undertaken, but the challenges LGBTQ+ students face seem far more prevalent and persistent in many schools. This seemed particularly true of those who identify as transgender or non-binary, especially if they had transitioned whilst at school. These students challenged both gender and sexuality norms, and were more likely to provide accounts of intense and persistent verbal and physical harassment, reflecting broader reported societal trends (e.g. CoE, Citation2021).

Conclusion

The positive picture presented in this study of school climate in some schools, the existence of a hostile school climate in others, and the lack of a strong LGBTQ+ friendly culture in most, should be a matter of concern. The positive examples of the ways in which some schools do promote a healthy and supportive environment for LGBTQ+ youngsters imply that this should be possible in other schools.

Our survey data suggest that students who identify as LGBTQ+, or question their identity, is a significantly-sized minority group in UK schools. Given what is known about the challenges facing members of the LGBTQ+ community, for example mental health issues, increased risk of poverty and so forth, looking at ways to normalise LGBTQ+ identities is an important societal issue. Identity formation, in terms of creating a secure, stable sense of self, is crucial to an individual’s development. Schools should address the cultural issues that prevent a supportive and affirmative environment in which this can happen for all students. The suggestion, that LGBTQ+ identities are challenged, ignored or attacked within schools is potentially destructive for those individuals, and raises serious questions about what schools should be doing proactively to address this. Essentially, the heterosexism and cisgenderism prevalent in school culture needs dismantling for LGBTQ+ identities to be normalised. It is not simply a case of “accommodating” such identities. Schools need to understand how existing hetero- and cisnormative power structures underpin school culture and climate, and serve to marginalise LGBTQ+ identities.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Year 8 students are aged 12–13, Year 9 are 13–14 and Year 10 are 14–15.

2 In the body of the paper, we have broken survey responses into non-LGBTQ+, questioning and LGBTQ+ students. To show further differences between groups of students we have included Appendix tables of those who identify as LGB, Trans and Q+, although the numbers for these groups are smaller, so the data is statistically less robust.

References

- Airton, L. (2018). The de/politicization of pronouns: Implications of the No Big Deal Campaign for gender-expansive educational policy and practice. Gender and Education, 30(6), 790–810. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2018.1483489

- Allan, A., Atkinson, E., Brace, E., DePalma, R., & Hemingway, J. (2008). Speaking the unspeakable in forbidden places: Addressing lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender equality in the primary school. Sex Education, 8(3), 315–328. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681810802218395

- Barnes, K., Brynard, S., & De Wet, C. (2012). The influence of school culture and school climate on violence in schools of the Eastern Cape Province. South African Journal of Education, 32(1), 69–82. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v32n1a495

- Berger, I., & Ansara, Y. G. (2021). Cisnormativity. In A. E. Goldberg, & G. Beemyn (Eds.), The SAGE encyclopedia of trans studies (pp. 122–125). Sage Publications.

- Bilodeau, B. L., & Renn, K. A. (2005). Analysis of LGBT identity development models and implications for practice. New Directions for Student Services, 2005(111), 25–39. https://doi.org/10.1002/ss.171

- Brennan, J. M., Dunham, K. J., Bowlen, M., Davis, K., Ji, G., & Cochran, B. N. (2021). Inconcealable: A cognitive–behavioral model of concealment of gender and sexual identity and associations with physical and mental health. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 8(1), 80–93. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000424

- Brooks, L. (2022, May 21). UK falls down Europe’s LGBTQ+ rights ranking for third year running. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/may/12/uk-falls-down-europes-lgbtq-rights-ranking-for-third-year-running

- Butler, J. (1999). Gender trouble: Feminism and the subversion of identity. Routledge.

- Cates, M. (2023, February 27). Transphobic bullying [Hansard]. (Vol. 728). https://hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/2023-02-27/debates/0474DBA1-F27C-475C-AB79-1ED639638D95/TransphobicBullying?highlight=trans#contribution-C06B4DE7-0136-42CE-8980-E9DF6C8E5C78

- Chen, J., Lau, C., Tapanya, S., & Cameron, C. A. (2012). Identities as protective processes: Socio-ecological perspectives on youth resilience. Journal of Youth Studies, 15(6), 761–779. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2012.677815

- Cohen, J., McCabe, E. M., Michelli, N. M., & Pickeral, T. (2009). School climate: Research, policy, practice, and teacher education. Teachers College Record: The Voice of Scholarship in Education, 111(1), 180–213. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146810911100108

- Council of Europe. (2021). Combating rising hate against LGBTI people in Europe. https://assembly.coe.int/LifeRay/EGA/Pdf/TextesProvisoires/2021/20210921-RisingHateLGBTI-EN.pdf.

- Gerson, K., & Damaske, S. (2021). The science and art of interviewing. Oxford University Press.

- Goodenow, C. (1993). The psychological sense of school membership among adolescents: Scale development and educational correlates. Psychology in the Schools, 30(1), 79–90. https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6807(199301)30:1<79::AID-PITS2310300113>3.0.CO;2-X

- Hall, W. J., Dawes, H. C., & Plocek, N. (2021). Sexual orientation identity development milestones among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and queer people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 753954. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.753954

- Harris, R., Wilson-Daily, A. E., & Fuller, G. (2021). Exploring the secondary school experience of LGBT+ youth: An examination of school culture and school climate as understood by teachers and experienced by LGBT+ students. Intercultural Education, 32(4), 368–385. https://doi.org/10.1080/14675986.2021.1889987

- Hoffman, L. G., Hevesi, A. G., Lynch, P. E., Gomes, P. J., Chodorow, N. J., Roughton, R. E., Barney, F., & Vaughan, S. (2001). Homophobia: Analysis of a “permissible” prejudice: A public forum of the American Psychoanalytic Association and the American Psychoanalytic Foundation. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Psychotherapy, 4(1), 5–53. https://doi.org/10.1300/J236v04n01_02

- Horton, C. (2020). Thriving or surviving? Raising our ambition for trans children in primary and secondary schools. Frontiers in Sociology, 5(67), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2020.00067

- Horton, C. (2023). Gender minority stress in education: Protecting trans children’s mental health in UK schools. International Journal of Transgender Health, 24(2), 195–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/26895269.2022.2081645

- Ingrey, J. C. (2018). Queer studies in education. Oxford research encyclopaedia of education. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.249

- Jones, J. R. (2014). Unnormalizing education: Addressing homophobia in higher education and K-12 schools. Information Age Publishing.

- Kennedy, N. (2018). Prisoners of lexicon: Cultural cisgenderism and transgender children. In E. Schneider, & C. Balthes-Lohr (Eds.), Normed children: Effects of gender and sex related normativity on childhood and adolescence (pp. 297–312). Transcript Publishing.

- Kjaran, J. I., & Jóhannesson, I. A. (2013). Manifestations of heterosexism in Icelandic upper secondary schools and the responses of LGBT students. Journal of LGBT Youth, 10(4), 351–372. https://doi.org/10.1080/19361653.2013.824373

- Kosciw, J. G., Clark, C. M., & Menard, L. (2022). The 2021 National School Climate Survey: The experiences of LGBTQ+ youth in our nation’s schools. GLSEN.

- Lee, R., Draper, M., & Lee, S. (2001). Social connectedness, dysfunctional interpersonal behaviors, and psychological distress: Testing a mediator model. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 48(3), 310–318. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.48.3.310

- Lennon, E., & Mistler, B. (2014). Cisgenderism. TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly, 1(1-2), 63–64. https://doi.org/10.1215/23289252-2399623

- Love, H. (2014). Queer. TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly, 1(1-2), 172–176. https://doi.org/10.1215/23289252-2399938

- Martino, W., & Cumming-Potvin, W. (2018). Transgender and gender expansive education research, policy and practice: Reflecting on epistemological and ontological possibilities of bodily becoming. Gender and Education, 30(6), 687–694. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2018.1487518

- Martino, W., Kassen, J., & Omercajic, K. (2022a). Supporting transgender students in schools: Beyond an individualist approach to trans inclusion in the education system. Educational Review, 74(4), 753–772. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2020.1829559

- Martino, W., Omercajic, K., & Kassen, J. (2022b). “We have no ‘visibly’ trans students in our school”: Educators’ perspectives on transgender-affirmative policies in schools. Teachers College Record: The Voice of Scholarship in Education, 124(8), 66–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/01614681221121522

- Mayberry, M. L., Espelage, D. L., & Koenig, B. (2009). Multilevel modeling of direct effects and interactions of peers, parents, school, and community influences on adolescent substance use. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38(8), 1038–1049. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-009-9425-9

- McBride, R. (2021). A literature review of the secondary school experiences of trans youth. Journal of LGBT Youth, 18(2), 103–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/19361653.2020.1727815

- McCormack, M., & Anderson, E. (2010). ‘It’s not acceptable any more’: The erosion of homophobia and the softening of masculinity at an English Sixth Form. Sociology, 44(5), 843–859. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038510375734

- Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

- Morse, J. M., & Niehaus, L. (2016). Mixed method design: Principles and procedures. Routledge.

- ONS. (2022). Sexual orientation, UK: 2020. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/culturalidentity/sexuality/bulletins/sexualidentityuk/2020

- Payne, E., & Smith, S. (2013). LGBTQ kids, school safety, and missing the big picture: How the dominant bullying discourse prevents school professionals from thinking about systemic marginalization or … why we need to rethink LGBTQ bullying. QED: A Journal in GLBTQ Worldmaking, 1(1), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.14321/qed.0001

- Peter, T., Campbell, C. P., & Taylor, C. (2021). Still in every class in every school: Final report on the second climate survey on homophobia, biphobia, and transphobia in Canadian schools. Egale Canada Human Rights Trust.

- Rawlings, V. (2019). ‘It’s not bullying’, ‘it’s just a joke’: Teacher and student discursive manoeuvres around gendered violence. British Educational Research Journal, 45(4), 698–716. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3521

- Reid, G. (2020, May 18). A global report card on LGBTQ+ rights for IDAHOBIT. The Advocate. https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/05/18/global-report-card-lgbtq-rights-idahobit.

- Saldaña, J. (2016). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (3rd ed.). Sage.

- Schachter, E. P. (2005). Context and identity formation: A theoretical analysis and a case study. Journal of Adolescent Research, 20(3), 375–395. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558405275172

- Schoen, L. T., & Teddlie, C. (2008). A new model of school culture: A response to a call for conceptual clarity. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 19(2), 129–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243450802095278

- Smith, A. U., & Schwartz, S. J. (2019). Waivers of parental consent for sexual minority youth. Accountability in Research, 26(6), 379–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/08989621.2019.1632200

- Stonewall. (2017). School report: The experiences of lesbian, gay, bi and trans young people in Britain’s schools in 2017. https://www.stonewall.org.uk/resources/school-report-2017

- Stonewall. (2023, May 9). EHRC ‘actively harming’ trans people, ignoring international recommendations, charities warn. https://www.stonewall.org.uk/about-us/news/ehrc-%E2%80%98actively-harming%E2%80%99-trans-people-ignoring-international-recommendations-charities

- Travers, A., Marchbank, J., Boulay, N., Jordan, S., & Reed, K. (2022). Talking back: Trans youth and resilience in action. Journal of LGBT Youth, 19(1), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/19361653.2020.1758275

- Ullman, J. (2014). Ladylike/butch, sporty/dapper: Exploring ‘gender climate’ with Australian LGBTQ students using stage–environment fit theory. Sex Education, 14(4), 430–443. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2014.919912

- Ullman, J. (2021). Free to be … yet?: The second national study of Australian high school students who identify as gender and sexuality diverse. Centre for Educational Research, Western Sydney University.

- Van Houtte, M. (2005). Climate or culture? A plea for conceptual clarity in school effectiveness research. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 16(1), 71–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243450500113977

- Weir, A. (2009). Who are we? Modern identities between Taylor and Foucault. Philosophy & Social Criticism, 35(5), 533–553. https://doi.org/10.1177/0191453709103426

- Wozolek, B. (2019). Implications of queer theory for qualitative research. Oxford research encyclopedia of education. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.735

- Yep, G. A. (2002). From homophobia and heterosexism to heteronormativity. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 6(3-4), 163–176. https://doi.org/10.1300/J155v06n03_14

Appendix

Table A1. Means for quantitative variables by student groupings of self-identifications