ABSTRACT

While the under-representation of women in senior leadership roles in the UK higher education sector is well recognised, scant regard has been paid to how this impacts female academics from alternative ethnicities and from overseas. This paper aims to help address this by summarising the findings from an integrative review of published evidence concerning the career prospects of women who are migrant academics from UK minority ethnic backgrounds (MAMEB) in the UK’s Higher Education sector, in three regards, these being [i] the scale and patterns of their under-representation, [ii] the possible causes of this under-representation and [iii] approaches which may be effective in addressing it. This review found there to be a paucity of material concerning the experiences of this core group of academics. Furthermore, considerations of differences between women from alternative ethnic groups or countries of origin were ostensibly absent from published studies. Explanations for under-representation include patriarchy, racism, xenophobia, and issues relating to personal agency. Potential strategies for addressing these inequalities were located at the societal, organisational and individual level. Moving forward, this study calls for further research, including the publication of detailed statistical analysis, to understand the scale and nuances of under-representation more fully by migrant women academics from minority ethnic groups in the UK. In addition, it recommends that senior leaders within the HE sector collaborate with the government to address the variety of structural and cultural barriers which impact these colleagues’ progression in leadership roles.

Introduction

The under-representation of women in senior leadership roles in Higher Education (HE) is both a persistent and global social phenomenon (CohenMiller et al., Citation2023; McTavish & Miller, Citation2009). Over time, a variety of initiatives and commitments have been introduced to address this issue, including, for example, the adoption of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women [CEDAW] and UNESCO’s Convention Against Discrimination in Education [CADE] (Chowdhury, Citation2023). Within the UK, the Athena Swan, Aurora and STEM initiatives have further sought to redress this imbalance, while individual institutions have also often introduced additional localised initiatives, aimed at securing similar outcomes. While these efforts have contributed to some improvement in the gender imbalance in senior leaders within the English HE sector, pronounced inequalities nevertheless remain (AdvanceHE, Citation2021).

Similarly, colleagues from a “non-White” background also continue to experience significant under-representation relative to their numbers across the sector as a whole (AdvanceHE, Citation2021). Again, a variety of initiatives have sought to address this imbalance, including for example Advance HE’s Diversifying Leadership programme and its Race Equality Charter. However, evidence of their impact is similarly mixed (Oloyede et al., Citation2021).

In the last two decades, marked increases in the numbers of academics from overseas joining UK HE Providers (HEPs) have added further complexity to this picture of under-representation (Universities UK, Citation2022). While the impact of globalisation on the profile of UK academic staff is recognised (Hughes, Citation2004), it nevertheless remains an area which is under-explored and, more pertinently for this study, its impact on the profile leadership largely ignored.

In our own careers, we have seen evidence, both anecdotal and empirical, of why representation matters. To be successful in reaching senior leadership positions in academic institutions, apart from the usual metrics on publication and research, there are informal social networks that support academics, and this social capital can be an important contributor to career progression (Angervall et al., Citation2018; Brabazon & Schulz, Citation2020; Heffernan, Citation2021). Thus, the absence of diversity amongst senior managers itself serves as an important barrier to addressing this issue.

Whilst many aspects of under-representation within HE globally have been explored individually and strategies to help address them proposed (e.g. Chowdhury, Citation2023), this article focuses on a specific intersection which has remained largely hidden, i.e. the underrepresentation of women in senior leadership roles in UK HEPs who are migrant academics from UK-minority ethnic backgrounds (MAMEB).Footnote1 Specifically, we explore the following questions:

What evidence is there concerning the under-representation within senior leadership positions in UK Higher Education Providers (HEPs) of MAMEB women?

What are the possible causes of this under-representation?

What approaches are potentially important in addressing under-representation and promoting greater access to senior leadership for MAMEB women?

Torraco (Citation2016) identifies the integrative literature review as “a form of research that reviews, critiques, and synthesizes representative literature on a topic in an integrated way, such that new frameworks and perspectives on the topic are generated” (Torraco, Citation2016, p. 356). We therefore considered this approach particularly suitable for our area of interest, given that it remains ostensibly ignored (our conclusion is that the overwhelming majority of research relevant to our study has focused on issues of gender and/or race and that the importance of migration has largely been overlooked). Thus, we offer this review as a baseline for existing knowledge, which effectively critiques and resolves inconsistencies, while simultaneously offering a fresh, new perspective that reveals the principal theories and patterns that emerge from the limited canon of relevant work (Baumeister & Leary, Citation1997).

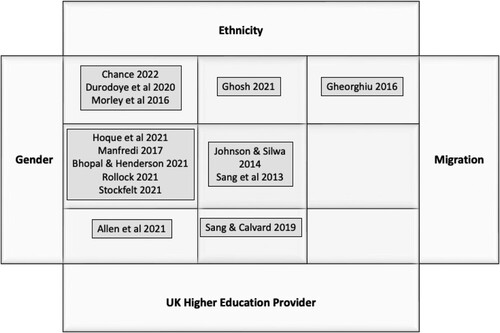

In our discussion, we note the paucity of empirical evidence on this issue, having identified only two journal articles focused on our core intersection of gender, ethnicity, migration, and academia in the UK. We describe and justify our strategy for buttressing this core by including a further twelve articles of particular relevance to our central focus, each of which we judged to provide an especially important contribution to considering at least two of these factors in unison.

We then examine the important implications of this and other relevant work from the wider leadership literature, suggest possible causes of under-representation, and identify approaches that may be important in promoting greater career progression for MAMEB women (some of these strategies may also be appropriate to other under-represented groups in academia going forward). To facilitate this, we offer an exploratory reading of the issues most important to MAMEB women and, at the same time, highlight issues that may be more generally relevant to discussions on gender and ethnicity in the academy.

Methodology

Identification of relevant articles

Torraco (Citation2016) highlights how in contrast to systematic reviews, the evidence base utilised in an integrative literature review may range from exhaustive to selective, representative, or pivotal depending on the purpose of the study itself. In all cases. however, transparency of aims and methods are essential to facilitating its critical appraisal. As this study focused on a relatively new and under-explored area, it utilised a strategy intended to maximise the scope of evidence examined (Torraco, Citation2016). To this end, consistent search parameters were employed to identify items of interest from the following databases:

EBSCO: Business Source Complete and Education Source

ProQuest: ABI/INFORM and Education Database

ERIC and

SCOPUS.

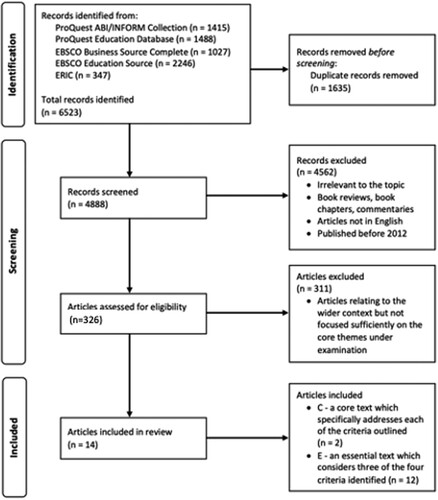

All searches were completed on 27 April 2022. In total 6,523 items were identified through these searches (including 1,635 items which appeared in multiple databases).

In line with Prisma (Citation2020), clear screening criteria were agreed in advance to ensure transparency and consistency amongst the reviewers. These were:

Is the article a peer-reviewed paper, published between 2012 and 2022?

Does the focus of the article relate to the UK higher education sector?

Does the paper focus explicitly and primarily on race/ethnicity (specifically “non-White”), AND nationality (specifically non-UK) AND gender/sex (specifically women)?

Is the focus of the paper on staff and not students?

In total, 4,888 items were assessed against these criteria by the research team. In each instance, the title and abstract were reviewed, and the item classified according to the following schematic:

C – a “core” text which specifically addresses each of the criteria outlined (2 items)

E – an “essential” text which considers three of the four criteria identified (12 items)

W – an item relating to the wider context but not focused on the core themes under examination (311 items)

R – rejected as irrelevant (4,562 items)

Items classified as “C”, “E” or “W” (n = 325) were then reviewed in full and their findings summarised in an Excel database. This database included details of each item’s year of publication, author, source, evidence base, identified limitations and main findings concerning the three research questions outlined above. In keeping with Petticrew and Roberts’s (Citation2006) recommendation, a summary of the (fourteen) most critical articles which formed the basis for this review is included in Appendix A. The intersections between these papers are summarised in , which shows of the 14 selected, only two cover all four areas of priority (i.e. UK HEP, gender, ethnicity and migration). Of the others, seven covered three intersections, with those between gender, ethnicity, and UK HEP the most common. The remainder were concerned with two intersections, most commonly gender and ethnicity.

Additional articles were also identified as part of this review and are referred to as appropriate within the subsequent sections of this paper.

Synthesis of findings

In producing this paper, the authors were cognisant of Post et al.’s (Citation2020) assertion that to make the greatest contribution to the discourse on any given issue, it is insufficient to simply report and summarise previous research. Instead, the focus should be to analyse, synthesise and generate an innovative way to conceive it. Therefore, the authors sought to connect, integrate, and effectively build upon alternative streams of literature on related areas of intersectionality, to create an original conceptual framework (Torraco, Citation2005), which embraced and extended the most relevant studies concerned with at least two of these considerations within the HE context.

Post et al. (Citation2020) identify seven specific, alternative avenues for theory generation, which may form the focus for an integrative review that seeks to extend the existing discourse in this way. Amongst these, the strategy of exploring emerging perspectives focuses on increasing understanding of a new phenomenon, in part by contrasting it with more established ideas; in this case, this included more established discourses concerning the career progression of both women in general and of women from minority ethnic backgrounds. Further value comes from the fact that articles on other, related intersectionalities such as this, often utilise alternative theoretical lenses for their consideration (e.g. feminism, conflict theory, critical race theory), as this required the authors to identify and analyse the assumptions (Post et al., Citation2020) within these discourses as to the factors which promote material differences in the experiences of these women, and, for example, the extent to which differences are driven by ethnographic and biographical variations. Our work further sought to address Post et al.’s (Citation2020) ambition for integrative reviews, by proposing a coherent and cohesive framework for both explaining and (tentatively) postulating (rather than predicting) the likely experiences of other minority ethnic women as they enter the UK HE system for the first time. In doing so, we seek to locate this outside of any individual perspective or discourse whilst nevertheless remaining cognisant of the value and limitations of each.

Findings

Evidence concerning the under-representation of MAMEB women within senior leadership positions in UK higher education providers (HEPs)

In the UK, AdvanceHE’s “staff statistics report” (AdvanceHE, Citation2021) provides the most comprehensive assessment of the demographic characteristics of staff employed within the HE sector. This annual report summarises data from HESA staff records on the characteristics of all academic and professional support staff holding one or more contracts of employment with a UK HEI. Data is primarily published in relation to age, disability, ethnicity, and gender. Some intersectional data is also included, providing (limited) insight into differences, for instance, by gender and broad ethnic group, and UK/non-UK nationality by gender and ethnicity. However, data is not published on how frequently MAMEB women reach senior leadership positions within UK HE.

Sang et al.’s (Citation2013) consideration of the careers of nine migrant academic women in the UK, and Johansson and Śliwa's (Citation2014) review of the experiences of 31 foreign female academics, are the only studies identified that specifically address the primary intersectional focus of this review. While Ghosh and Barber (Citation2021) and Sang and Calvard (Citation2019) have also examined the experiences of migrant female academics, these focused on the US and Australian/New Zealand contexts respectively rather than experiences of those migrating to the UK. Elsewhere other studies of interest considered a more limited number of relevant intersectionalities. For instance, Manfredi (Citation2017), Rollock (Citation2021), Stockfelt (Citation2018) and Bhopal (Citation2020a) all provide valuable understanding of the experiences of female academics from ethnic minorities in the UK but do not specifically consider how these may affect migrants.

Other studies identified in our work offer insight into the experiences of women academics from other ethnicities and/or HE systems, but do not consider how migration may affect this. For instance, Ford et al. (Citation2018) focus on the under-representation of indigenous women in the Australian higher education system, while Zhao and Jones (Citation2017) and Abalkhail (Citation2017) explore the challenges faced by women academics in advancing their careers in China and Saudi Arabia more generally. Morley (Citation2014) and Morley and Crossouard (Citation2016) also offer interesting multinational comparisons of women academics’ experiences, primarily (but not exclusively) focused on the Middle East and Indian subcontinent.

Despite these empirical studies in various contexts, we found that most research on the under-representation of women academics with the dynamics of race, gender and career progression focuses on US academic institutions. Moreover, much of this specifically examines the experiences of Black women (e.g. Chance, Citation2022; Durodoye et al., Citation2020; Ghosh & Barber, Citation2021; Jean-Marie, Citation2011), although limited other work considers the experiences of women from alternative ethnic backgrounds, including Hispanic (e.g. Suárez-McCrink, Citation2011) Pacific Islander and American Asian (Le, Citation2016).

Notwithstanding these limitations, analysis of data included in these (and other) sources reveals some interesting patterns, which in turn shed light on the situations of academics considered in this paper.

Firstly, the relative disadvantage of women within HE more broadly is well recognised and has been a focus for study throughout this century. Indeed, considerable evidence demonstrates how women academics frequently occupy lower positions in institutions within most developed countries (Acker, Citation2008; Probert, Citation2005). In the US for instance, Durodoye et al. (Citation2020) note that while efforts in the 1970s to improve gender diversity at a faculty level led to some improvements, fifty years later women are still more likely to be clustered in junior positions, with fewer promoted to professor. Indeed, O’Connell and McKinnon (Citation2021) suggest that only around 32% of professors in the US are female, with slightly fewer (around 27%) reaching this status in the European Union. Data from AdvanceHE confirms that while the proportion of professors who are women in the UK has increased by half since 2010, it remains broadly in line with other countries (AdvanceHE, Citation2021; Brill, Citation2010).

Secondly, while women in general remain under-represented in higher education per se, there are important differences in experiences between women from different ethnic backgrounds. More specifically, writers such as Bhopal (Citation2020b) have highlighted how in the UK women from a non-White background are in general less likely to reach leadership positions than their White colleagues. This view is supported by data from AdvanceHE (Citation2021), summarised in . This shows that White male UK nationals continue to dominate the most senior roles in this country, accounting for 65% of all professors, but only 44% of academics at more junior levels. While the picture is reversed for women of all ethnicities, the scale of under-representation differs markedly between Black, Asian and Minority ethnic (BAME) women and those who are White.

Table 1. Academic staff by professional category, gender, and BAME/White identity (developed from table 5.7 Advance HE “Equality and higher education staff statistical report” Citation2022).

While is helpful in highlighting the under-representation of female (and indeed male) academics from non-White backgrounds in leadership, it contains several significant limitations for our study. Firstly, data is not provided on academics’ countries of origin and so it is impossible to assess the impact that migration may have on the patterns shown. Secondly, the fact that data on ethnicity is published at a high level of aggregation and under the category of “BAME” is problematic for both analytical and philosophical reasons. At a practical level aggregated data prohibits the exploration of patterns which may exist within its individual subgroups. Philosophically, this aggregation makes important assumptions concerning the comparability of its constituent groups which are problematic, and compounded by adopting the abbreviation “BAME”. In essence, this reflects a tendency within this discourse to homogenise the experiences of non-White academics, which effectively serves to mask important nuances in patterns of inequality affecting colleagues from diverse and distinct ethnic backgrounds (Stockfelt, Citation2018). One example of this concerns important differences in how women from different contexts construct their personal identity and the relative importance they place on ethnicity and gender. For instance, Valverde’s (Citation2011) work highlights the importance of historical, sociological, and philosophical factors determining how US women emphasise alternative aspects of identity, noting that while Asian women academics most commonly consider gender to be a more dominant characteristic than ethnicity, the reverse is true of their Latina, African America and African Indian counterparts. Similarly, Bhopal (Citation2020b) concludes that in the UK, White privilege means that for White women, issues of ethnicity may barely feature at all. The importance of such differences, which are therefore hidden by such aggregation, should not be under-estimated and often reflect profound disparities in historical socio-political contexts, the legacies of which can be identified in alternative strands of feminist philosophy (Pasque, Citation2011). That White minority groups (such as Travellers and Gypsy Roma for example) are excluded from this classification (Advance HE, Citation2023) is also problematic as it further perpetuates a view that it is skin colour which serves as the dominant driver of an individual’s identity and lived experience. Little wonder then that the term “BAME” is also criticised as both ill-understood and as a mechanism for perpetuating unequal power relations (Aspinall, Citation2021).

However, while such limitations in data publication restrict opportunities to examine the dynamics between alternative intersectionalities, nevertheless provides further insight into the disparities between academics from different ethnic groups, and from a UK and non-UK background.

Table 2. Academic staff by professional category and BAME/White identity (developed from table 3.20 Advance HE “Equality and higher education staff statistical report” Citation2022).

also supports a variety of research which has highlighted how in addition to experiencing restricted opportunities for promotion, academics who are women, from non-White backgrounds and from overseas endure less favourable conditions in a variety of other ways, including in relation to pay and security of tenure (Bhopal, Citation2020a; Bhopal & Brown, Citation2016; Johansson & Śliwa, Citation2014; Sang et al., Citation2013). It shows that women academics remain far more likely to work part time than their male counterparts (40.9% c.f. 28.5%) and are also more likely to be employed in professional and support roles (62.7% c.f. 37.3%) than higher status academic ones (Advance HE, Citation2021).

shows similar inequalities in terms of academics’ tenure. While variations may be relatively small, women academics are nevertheless more likely to be employed on fixed term contracts than their male counterparts. also shows marked differences in the employment status of White and non-White academics from both the UK and overseas, with these collectively favouring White UK nationals over other groups.

Table 3. UK/non-UK academics, by contract type and gender/ethnicity (developed from tables 3.5 and 4.5, Advance HE “Equality and higher education staff statistical report” Citation2022).

Causes of under-representation

Patriarchy, gender stereotypes and the myth of meritocracy

One common theme concerns the persistence of a patriarchal culture which continues to negatively impact women’s career prospects across many professional settings (Bhopal, Citation2020a; Ghosh & Barber, Citation2021; Johansson & Śliwa, Citation2014; Sang et al., Citation2013). Patriarchy can take a variety of forms. For example, Stockfelt (Citation2018), Durodoye et al. (Citation2020) and Ghosh and Barber (Citation2021) describe how academic roles are often segregated between genders. Ghosh and Barber (Citation2021), for instance, see female academics as “often expected to be emotionally available to students as bosomy mother figures” (Ghosh & Barber, Citation2021, p. 1064), leading to them being overburdened in less prestigious academic duties such as mentoring, advising, committee work and other service duties. Such gendered segregation produces a “double whammy” effect of reducing women’s capacity to focus on more prestigious activities such as research and funding applications, while simultaneously providing greater space for men to do so.

Patriarchy is seen to extend into fundamental assumptions as to how success within HE is defined. Johansson and Śliwa (Citation2014) for instance describe how a “myth of meritocracy” (seemingly based on neutral, objective criteria) serves to perpetuate a focus on individual achievement, while obscuring underlying processes of differentiation and discrimination that (invariably) prejudice against women (e.g. different expectations around childcare responsibilities). A variety of other writers posit that assumptions of race are inextricably intertwined within such myths and assumptions. Jean-Marie (Citation2011) for instance notes that, regardless of any wider discourses of equity, policies within HEPs are invariably written by, or for, White men in power, and serve (directly or indirectly) to protect their positions of power. Cotterill et al. (Citation2006) build on Johansson and Śliwa’s (Citation2014) position, by asserting that HEPs are invested in representations which are inescapably masculine, neo-liberal and White, and unsurprisingly, assume ontological and epistemological positions which are consistent with this. In practice this results in measures to assess quality and success that are predominantly Positivist in nature, and a prevailing view that activities only really “count” if they produce tangible outputs which can be “objectively” quantified. This perspective subsequently supports a culture dominated by metrics, in key areas of research (with its metrics to assess research quality via ranking lists and output targets) and teaching (where the quality and impact of teaching can be “objectively” observed and accurately assessed using quantitative measures), which in turn generate pan-institutional frameworks and strategies that perpetuate inequality in these and other key areas (such as networking and collaboration) and ultimately promotion (Cotterill et al., Citation2006; Jean-Marie, Citation2011; Lipton, Citation2017; Spence, Citation2018). Furthermore, while such mechanisms prejudice the interests of all women, Campbell (Citation2022) argues their ethnocentricity means that those from a non-White background in general, and Black women in particular, are disproportionately impacted.

Racism, uneven career pathways and a “hierarchy of colour”

Discussions of prejudice also feature consistently within the literature. For instance, in her study of the experiences of Black professors in the UK, Rollock (Citation2021) identifies racism as operating at both an individual and wider systemic level. Here, racism is the key reason why “Black female academics endure an uneven and convoluted pathway to professorship characterized by undermining, bullying, and the challenges of a largely opaque progression process” (Rollock, Citation2021, p. 209). Similarly, Oade (Citation2009) highlights strong racial and gender elements to the various forms of bullying that take place in the academic context, including personal verbal abuse, derogatory remarks, spreading false rumours, and a wider set of behaviours which cause academics to doubt themselves, reduce their self-esteem and question their competence or commitment.

Stockfelt (Citation2018) expands this discourse by emphasising the need to explore the nuances of individual experiences. Importantly, in her examination of the experiences of several Black female academics in the UK, she highlights how some respondents believe “society utilises a hierarchy of colour with darker skins at the bottom” (Stockfelt, Citation2018, p. 1023), which in turn has implications for the treatment received. From an academic perspective, she describes one respondent’s opinion that Chinese academics were commonly viewed as the “model minority” with Blacks (Caribbean, African, British, and other) at the bottom. Valverde (Citation2011) also identified a similar hierarchy in the US context, noting that the “prevailing stereotypical thinking about Asians [sic] is that they are intellectually more capable than other groups of color” (p. 52); a perspective which he states underpins the term “model minority” in relation to this group and has very real implications in relation to career advancement.

Given Stockfelt’s (Citation2018) conclusion that ethnicity impacts more than gender on career prospects, the significance of such a hierarchy is important within the context of this study and links strongly to the discourse of scientific racism. Durodoye (Citation2003) for instance identifies a long tradition of science both contributing to and reinforcing inequality in general and a view of “non-White” as inferior in particular. Similarly, Sue and Sue (Citation2003) highlight how “differences” between alternative groups have effectively been framed as deviations from and deficient to a “White” norm, regardless of the fact ethnicity itself is socially constructed and does not exist a priori. Diamond (Citation1994) for instance notes a variety of alternative ways in which humans may be defined and categorised, such as digestion, genes, and resistance, each of which can be justified as coherently as by skin colour. From one perspective, it is therefore unsurprising that it is colour which is central to such discussions of relative biological merit, given that it is this characteristic which most readily distinguishes the allocation of privilege within many societies. In our view, the fact that academia as a core social institution has historically facilitated Scientific Racism, which continues to legitimise negative stereotyping and impact on material outcomes at all levels of society, reinforces the importance of our study.

Xenophobia, its intersection with race and gender, and conceptualisations of “foreignness”

Ghosh and Barber (Citation2021) discuss how racism and xenophobia, often underpinned by spurious pseudo-scientific justifications as outlined above, impact migrant academic women’s career progression. Perhaps most strikingly, they highlight how racism and xenophobia operate as independent variables, influencing academics’ careers in a variety of complex ways. For example, while White overseas academics may benefit from racial privileges, they frequently simultaneously suffer exclusion because of xenophobic prejudice, for example pre-conceptions concerning their linguistic skills. For women, challenges associated with patriarchy and misogyny, outlined above, complicate this dynamic further. For example, Lin et al. (Citation2004) found that women academics often believe sexism to be a driving factor behind students and colleagues using feedback mechanisms to question their wider professional capabilities, which in turn may result in significant damage to their career progression. That responsibility for this is frequently placed on the individual academic themselves (e.g. that they need to develop their linguistic capabilities further) is telling, as this serves to simultaneously both deny yet reinforce what can be a wider hostile culture for women in academy (Nawyn et al., Citation2012).

Gheorghiu and Stephens (Citation2016) also highlight how xenophobia can negatively impact migrants’ career prospects. Michael (Citation2011) adds further complexity to this picture by noting how in recent years HEPs, driven largely by commercial considerations, have increasingly sought to position “foreignness” (including amongst its academic staff) as an asset and source of enrichment to campus life, but at the same time, failed to provide the support migrant academics require to realise their full potential. Furthermore, to compete effectively with domestic academics, foreign colleagues may in practice be required to demonstrate greater productivity, despite potentially enduring language related difficulties, fewer mentors, smaller professional networks, and more limited access to support (Kim et al., Citation2011; Mamiseishvili & Rosser, Citation2010; Stephens, Citation2016). Clarke (Citation2005) notes how in many instances, these and other issues can produce tensions which contribute to increased recognition of difference, and in turn greater, negative latent or overt competition which can spill over into incivility and bullying.

“Glass, concrete and ivory ceilings”

Numerous studies employ metaphoric “ceilings” to highlight how structural factors place de-facto limitations on academics’ careers. Hoque et al. (Citation2021) for instance describe the presence of a (generalised) glass ceiling for female academics within a medical context, who despite outperforming their male counterparts on a range of measures, remain markedly less likely to achieve leadership roles because of various invisible barriers to career advancement. Similarly, Manfredi et al. (Citation2014) identify an “ivory ceiling” through which passive racism requires Black academics to work twice as hard as their White peers to secure promotion. For Baxter-Nuamah (Citation2015), the scale of challenges to be overcome is better embodied through the metaphor of a “concrete ceiling”, which is in practice almost impossible to penetrate and reinforced through racism, sexism, ageism, stereotyping threat, isolation, and tokenism.

These metaphorical ceilings operate at both a systemic and institutional level. Durodoye et al. (Citation2020) for instance highlight how in the US, such ceilings are maintained within individual organisations by “an unwelcoming climate, slanted internal processes and disinterested policymaking, all [of which] adversely impact the promotion prospects of women of colour at an individual institutional level” (p. 630). Similarly, a lack of positive role models, reduced mentoring opportunities and an unwillingness to challenge patriarchal procedures and cultures are also identified within individual institutions as restricting career prospects for women in general and women of colour in particular (Bhopal, Citation2020a; Johansson & Śliwa, Citation2014; Stockfelt, Citation2018). If women do make it to interview, Valverde (Citation2011) suggests the panel they face is likely to be dominated by White men, and employ masculine criteria for assessing their suitability.

Personal factors and individual agency

Unsurprisingly, many of the factors identified above as restricting the career progression of individuals at the system or organisational level are also keenly felt on a routine, day-to-day basis by individual academics. Bhopal and Brown (Citation2016) for instance highlight how the intersection between gender, ethnicity and class can compound the challenges academics face personally and the decisions they routinely have to make, describing this as a “triple burden”; less then, the even application of gravity and more the feeling of carrying a millstone around one’s neck.

Social ostracisation and exclusion from (male dominated) networks (Allen et al., Citation2021; Bhopal, Citation2020a; Ghosh & Barber, Citation2021), dealing with conflict and bullying (Gheorghiu & Stephens, Citation2016; Rollock, Citation2021) and coping with toxic cultures (Stockfelt, Citation2018) are all challenges identified in the literature as more likely to be faced on a day-to-day basis by women and women of colour.

Tellingly, Monroe et al. (Citation2008) conclude that organisations frequently view such issues as problems for the individual to cope with rather than for the institution to address. Similarly systemic challenges relating to gendered issues such as the allocation of caring responsibilities, frequently require women from all backgrounds to make difficult personal decisions, and feature heavily within discussions around the role of personal agency in career progression. For MAMEB women, the reduced likelihood of an extensive support network makes such dilemmas especially keenly felt. Thus, discourses of personal agency effectively reinforce gendered, racial and other inequalities by absolving social and individual institutions of their responsibility to address them.

Important approaches in addressing under-representation and promoting greater access to senior leadership

Relatively little space is given in the literature to exploring approaches to addressing the variety of issues identified as barriers to progression to senior leadership roles for MAMEB women. Where strategies themselves are discussed, many of the approaches described are at a relatively high level and effectively reiterate the causes of inequality already discussed.

Sector and societal approaches

One of the fullest considerations of strategies targeted at systemic challenges features in Allen et al.’s (Citation2021) exploration of inequality in the Australian HE sector. Building on the work of Westering et al. (Citation2012), Allen et al. (Citation2021) advocate strengthening legislation at a national level to address societal inequalities underpinning poorer career outcomes for women. In doing so, they highlight a range of legislation relating to this issue generally, and the presence of regulatory standards specifically tailored for the education sector. However, they also recognise the limitations of such legislation and draw attention to various structural issues across HE which systematically reproduce inequalities in outcomes between male and female academics, for instance in terms of patriarchal assumptions which underpin systems to awarding grants and funding, publishing papers, accessing professional development and securing leadership opportunities. Thus, Allen et al. (Citation2021) echo the views of writers such as Manfredi (Citation2017) and Durodoye et al. (Citation2020) who see change as requiring a more fundamental reconsideration as to what success “looks” like in HE and the development of a more inclusive definition for this.

HEP and organisational strategies

Several studies focus on the organisational level and identify specific actions individual HEPs can take to address under-representation. For example, Manfredi (Citation2017) calls for greater commitment to strategies of positive action, including targets for diversity, and outlines approaches which can address barriers to recruitment and promotion. Sang and Calvard’s (Citation2019) work in Australia and New Zealand also advocates the need for universities to adopt clearer and more consistent policies for promotion, not least to enable them to be scrutinised for their implicit “Whiteness”.

Bhopal and Henderson (Citation2021) highlight the impact having a family can have on career prospects, and the responsibilities that HEPs have to address the disproportionate impact of this on women’s careers. Allen et al. (Citation2021) and Bhopal (Citation2020a; Citation2020b) also recognise a broader need to promote examples of successful female academics from minority ethnic backgrounds, while simultaneously monitoring promotion and recruitment practices to ensure that their numbers increase. At the same time, role models of this kind may also make a major contribution to the progression of their peers, by supporting mentoring programmes which help academics from our intersection of interest to realise their potential (Allen et al., Citation2021; Bhopal, Citation2020b; Citation2020a).

However, while such policies and strategies have an essential role to play in addressing the inequality outlined, their existence alone is no guarantee of success. Rollock (Citation2021) for instance notes that “universities, like many public institutions, author equality and diversity statements and express their unrelenting commitment, in job advertisements and elsewhere, to increasing the number of under-represented groups, especially women, those with disabilities, and those from Black and minority ethnic backgrounds. However, such statements and promises do relatively little to alter the education landscape either in terms of representation or improving the daily experiences of these groups” (Rollock, Citation2021, p. 215).

Allen et al. (Citation2021) identify leadership as among six key areas which require systematic intervention to effect genuine change on this issue. More specifically, they note that leaders’ commitment is essential to the success of initiatives intended to promote equality and to addressing both structural and cultural issues which potentially threaten it.

Personal strategies

The greatest consideration of potential approaches to addressing inequalities in representation between gender and different ethnic backgrounds at senior leadership level focuses on actions open to individual academics. This may reflect a context where structural safeguards are largely ineffective, and it is therefore beholden on the individual to identify and take the necessary action themselves. As noted above, it can also be seen as a mechanism for reinforcing existing patriarchal and race-based exclusionary cultures and structures, and absolving institutions and the sector as a whole of responsibility. Effectively, then, it legitimises a “victim blaming” discourse and narrative that as some women achieve “success”, all can, so as long as they are prepared to do whatever is necessary to achieve it.

One strand of this concerns the degree to which MAMEB women who aspire to leadership positions should actively seek to assimilate with existing, dominant cultures. For instance, Sang et al. (Citation2013) found that while most foreign academics in their study had applied for UK citizenship, retaining the capacity to draw on their wider experiences was nevertheless key to their success: “for these women, standing at the intersection of two countries was seen as an advantage, as they were able to draw on two repertoires of academic and cultural tradition, which helped them identify a wide range of possibilities and work in the UK” (p. 164). Similarly, Johansson and Śliwa (Citation2014) assert that being such a metaphoric “double stranger” may not be an uncomplicated cumulative disadvantage, and indeed for overseas academics in UK business schools, “foreignness” could serve as an asset, enabling them to test and potentially exploit differences in cultural norms to their own advantage. At the same time, Johansson and Śliwa (Citation2014) concede that the effectiveness of such strategies may be limited by a range of factors, including the cultural proximity of an individual academic’s schools and their personal biography. One example of proximity is alternative dimensions of linguistic competence, with accent in particular serving as an important marker of class and ethnicity, and therefore acting in practice as a powerful attribute for the social positioning of academics (Coulthard, Citation2008). Similarly, self-presentation (for example in terms of dress and the use of jewellery to meet European standards of beauty) may also be an important factor in the process of (personal) social construction and subsequently impact an individual’s career progression within academia (Bauder, Citation2006; Chance, Citation2022; Johansson & Śliwa, Citation2014).

Finally, several writers highlight the value of a small set of personal attributes in career progression. For example, Johansson and Śliwa (Citation2014) and Rollock (Citation2021) both draw attention to the importance of commitment and hard work, while recognising that what is judged as “working hard” and therefore worthy of reward is underpinned by established masculine norms, and often varies depending on ethnicity, gender and migrant status. Sang et al. (Citation2013) highlight the value placed on mobility as a means of “demonstrating commitment”, which again can be viewed as embedded within masculine assumptions of what is necessary for career progression, and does not take into account factors including gendered expectations of family and caring responsibilities. Personal resilience is also highlighted as critical in some studies, with Chance (Citation2022) for instance concluding that resilience and strength are core characteristics of the “superwomen” who overcome challenges of racism, sexism and ageism to achieve leadership positions in academia in the US. Indeed for Chance (Citation2022), overcoming such obstacles is not only necessary for personal success; it also helps to develop the attributes required for success as leaders in the future.

summarises the principle causes of under-representation and approaches to addressing them identified by this review.

Table 4. The principle causes of under-representation and approaches to addressing them.

Discussion

Our integrative literature review identifies several important findings concerning the under-representation of MAMEB women in senior leadership positions in HE.

Firstly, while the under-representation of both women and of people from Black and minority ethnic backgrounds have long been recognised as issues within a variety of academic contexts (Miller, Citation2016; Xiao et al., Citation2020), the intersection between these and migration has largely been ignored. This is reflected in the paucity of published statistics, with what limited data is produced aggregated at too high a level to support exploration of the differences between the experiences of women from different backgrounds. While we recognise this may in part be a consequence of technical limitations, presenting data in this way at once precludes such detailed explorations, while simultaneously promoting a homogenised perspective which subconsciously devalues such an activity in any case. This is especially unfortunate in this instance, given the suggestion that nationality and ethnicity may both act as powerful agents in these women’s career journeys. Thus, while such data allows us to identify a number of broader challenges which migrant academics face (such as less secure tenure for instance), it is impossible to determine the degree to which these affect colleagues from particular contexts. Given Stockfelt’s (Citation2018) suggestion that a de-facto “hierarchy” may exist in how ethnicity is viewed and Johansson and Śliwa (Citation2014) claim that for some, “foreignness” may actually represent an asset, this is particularly frustrating.

Secondly, patriarchy serves as a central unifying theme in the experiences of all women, regardless of ethnicity and nationality. The literature reviewed in this study reveals how this impacts women in a variety of ways, some of which are less overtly recognised. The detrimental effect that maternity may have on women’s careers is well documented across a wide range of careers and industries, but considerably less attention has been given to the precise mechanisms through which this occurs. Johansson and Śliwa’s (Citation2014) concept of the “myth of meritocracy” is therefore especially valuable here in making explicit how supposedly “neutral” and gender-blind considerations, primarily concerned with research activity, frequently disadvantage female academics in general and those with additional caring responsibilities in particular. What is missing in the literature is a fuller insight into how cultural and other considerations mediate the impact of patriarchy to produce different outcomes for MAMEB women.

Studies included in this review highlight how patriarchy operates at a variety of levels, with systemic challenges amplified or reduced at both the institutional level (for instance through policy decisions and work cultures) and the personal/interpersonal level (for example through expectations concerning work choices, bullying, and social exclusion). The material reviewed here suggests strategies which may help to address these. Perhaps foremost in these is the contribution leaders can make in a variety of ways, including for example promoting networks, providing mentoring opportunities, and challenging gender-based expectations around caregiving (both within the personal and professional spheres).

Thirdly, research reviewed strongly evidenced the relative importance colleagues place on alternative, intersecting aspects of personal biography in their (personal) constructions of identity (Crenshaw, Citation2021, Citation2013). Becker’s (Citation1963) seminal work on labelling is particularly valuable here in highlighting how dimensions of ethnicity, place and gender combine in complex ways to influence both how colleagues view themselves and are viewed by others. For researchers, policy makers and programme developers, navigating the delicate path between atomisation and generalisation is perhaps the most difficult ongoing challenge in ensuring that future work considers questions of this nature in “coherent but sensitive ways” (Nichols & Stahl, Citation2019, p. 1257).

Limitations of this study

Despite considerable interest in career progression within academia, relatively few studies were identified which covered the central focus of our research. This was perhaps to be expected given the emergent and highly specific nature of our interest. We addressed this in part by adopting an approach which at once was wider (in terms of the intersectionalities it covered) and more targeted (in that it focused on the most important studies only), and thereby enabled the team to utilise the most important research focused on closely related intersectionalities relating to gender and ethnicity.

In our review we focused on three specific aspects of MAMEB women’s identity in relation to their ambitions to reach senior leadership positions, these being gender, ethnicity, and migrant status. A fundamental question therefore is whether there are other aspects which may be equally or potentially more important, such as sexuality, religion or class.

Within our paper, we have discussed at some length the philosophical and practical limitations associated with categorisations of ethnicity and recognise that these are applicable to a significant proportion of the source material which underpins this review.

Finally, we acknowledge an important limitation within the integrative review methodology itself. Integrative reviews are inevitably dependent upon the scale and quality of material available (Elsbach & Knippenberg, Citation2020). This risk is potentially heightened in intersectional studies where the scope of interest is narrowed and availability of source material reduced (Elsbach & Knippenberg, Citation2020).

Implications for research and practice

Our review has a variety of implications for research and practice. Firstly, it highlights the paucity of empirical evidence into the factors which inhibit the prospects of migrant female academics from ethnic minorities securing leadership positions. Care is needed to ensure that such studies provide insight into the various ways in which such barriers impact women from different contexts, together with the efficacy of alternative strategies in addressing these.

Secondly, despite their espoused commitment to addressing the under-representation of women within leadership positions, alongside more generally addressing issues of diversity as part of their wider commitment to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), more needs to be done to encourage HEPs to embed practices which genuinely tackle the root causes of this. Our view is that given the scale and complexity of these challenges, it is necessary for the sector as a whole to work with the government to develop and implement the safeguards necessary to produce practical outcomes, which genuinely make progress and do not simply pay lip service to the concerns of those affected. One step is to publish openly disaggregated data which lays bare, for the first time, the true scale of how under-representation affects women from a wider variety of backgrounds.

Finally, our review highlights the role which MAMEB women themselves may play as agents of change. Moving forward we believe this review has helped to clarify what further work may look like, and those pieces of the puzzle which it is most important to source.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 In using this abbreviation, the authors are mindful not to be seen as attempting to introduce yet another acronym to an already overcrowded lexicon. Moreover, in this context, we are especially concerned that such a strategy could be seen to infer a uniformity of experience and homogeneity of context which we explicitly reject. As such this term is used solely to simplify presentation and increase the readability of this paper.

References

- Abalkhail, J. M. (2017). Women and leadership: Challenges and opportunities in Saudi higher education. Career Development International, 22(2), 165–183. https://doi.org/10.1108/CDI-03-2016-0029

- Acker, J. (2008). Helpful men and feminist support: More than double strangeness. Gender, Work and Organization, 15(3), 288–293. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0432.2008.00393.x

- AdvanceHE. (2021). Staff statistical report 2021. https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/equality-higher-education-statistical-report-2021

- Advance HE. (2022) Equality and Higher Education Staff statistical report 2021. https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/equality-higher-education-statistical-report-2021

- Advance HE. (2023). Use of language: Race and ethnicity. https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/guidance/equality-diversity-and-inclusion/using-data-and-evidence/use-of-language-race-ethnicity#BAME

- Allen, K.-A., Butler-Henderson, K., Reupert, A., Longmuir, F., & Finefter-Rosenbluh, I. (2021). Work like a girl: Redressing gender inequity in academia through systemic solutions. Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice, 18(3), 14–29. https://doi.org/10.53761/1.18.3.3

- Angervall, P., Gustafsson, J., & Silfver, E. (2018). Academic career: On institutions, social capital and gender. Higher Education Research and Development, 37(6), 1095–1108. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2018.1477743

- Aspinall, P. J. (2021). Bame (black, Asian and minority ethnic): The ‘new normal’ in collective terminology. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 75, 107. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2020-215504

- Bauder, H. (2006). Labour movement: How migration regulates labour markets. Oxford University Press.

- Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1997). Writing narrative literature reviews. Review of General Psychology, 1(3), 311–320. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.1.3.311

- Baxter-Nuamah, M. (2015). Through the looking glass: Barriers and coping mechanisms encountered by African American women presidents at predominately White institutions. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database (UMI no. 3702781).

- Becker, H. (1963). Outsiders: Studies in the sociology of deviance. The Free Press.

- Bhopal, K. (2020a). Gender, ethnicity and career progression in UK higher education: A case study analysis. Research Papers in Education, 35(6), 706–721. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2019.1615118

- Bhopal, K. (2020b). Confronting White privilege: The importance of intersectionality in the sociology of education. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 41(6), 807–816. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2020.1755224

- Bhopal, K., & Brown, H. (2016). Black and minority ethnic leaders: Support networks and strategies for success in higher education small development projects. www.lfhe.ac.uk.

- Bhopal, K., & Henderson, H. (2021). Competing inequalities: Gender versus race in higher education institutions in the UK. Educational Review, 73(2), 153–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2019.1642305

- Brabazon, T., & Schulz, S. (2020). Braving the bull: Women, mentoring and leadership in higher education. Gender and Education, 32(7), 873–890. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2018.1544362

- Brill, C. (2010). Equality in higher education statistical report 2010. https://s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/assets.creode.advancehe-document-manager/documents/ecu/equality-in-higher-education-statistical-report-2010_1578649784.pdf.

- Campbell, S. L. (2022). Shifting teacher evaluation systems to community answerability systems: (Re)Imagining how we assess black women teachers. The Educational Forum (West Lafayette, Ind.), 86, 80–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131725.2022.1997523

- Chance, N. L. (2022). Resilient leadership: A phenomenological exploration into how black women in higher education leadership navigate cultural adversity. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 62(1), 44–78. https://doi.org/10.1177/00221678211003000

- Chowdhury, D. (2023). Making higher education institutions gender-sensitive: Visions and voices from the Indian education system. In Leading change in gender and diversity in higher education from margins to mainstream (pp. 239–258). Routledge.

- Clarke, S. (2005). The neoliberal theory of society. In A. Saad-Filho, & D. Johnston (Eds.), Neo-liberalism: A critical reader. Pluto Press.

- CohenMiller, A., Hilton-Smith, T., Mazanderani, F., & Samuel, N. (2023). Reimagining higher education leadership through envisioning spaces for agency. In A. CohenMiller (Ed.), Leading change in gender and diversity in higher education from margins to mainstream (pp. 1–4). Routledge.

- Cotterill, P., Hughes, C., & Letherby, G. (2006). Editorial: Transgressions and gender in higher education. Studies in Higher Education (Dorchester-on-Thames), 31(4), 403–406. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070600800350

- Coulthard, M. (2008). By their words shall ye know them: On linguistic identity. In C. Caldas-Coulthard, & R. Iedema (Eds.), Identity trouble. Critical discourse and contested identities (pp. 143–155). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Crenshaw, K. (2021). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. Droit et Société, 108(2), 465–487. https://doi.org/10.3917/drs1.108.0465

- Crenshaw, K. W. (2013). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. In The public nature of private violence (pp. 93–118). Routledge.

- Diamond, J. (1994). Race without color. Discover (Chicago, Ill.), 15(11), 82.

- Durodoye, B. (2003). The science of race in education. Multicultural Perspectives (Mahwah, N.J.), 5(2), 10–16. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327892MCP0502_3

- Durodoye, R., Gumpertz, M., Wilson, A., Griffith, E., & Ahmad, S. (2020). Tenure and promotion outcomes at four large land grant universities: Examining the role of gender, race, and academic discipline. Research in Higher Education, 61(5), 628–651. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-019-09573-9

- Elsbach, K. D., & Knippenberg, D. (2020). Creating high-impact literature reviews: An argument for ‘integrative reviews.’. Journal of Management Studies, 57(6), 1277–1289. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12581

- Ford, L. P., Guthadjaka, K. G., Daymangu, J. W., Danganbar, B., Baker, C., Ford, C., Ford, E., Thompson, N., Ford, M., Wallace, R., St Clair, M., & Murtagh, D. (2018). Re-imaging aboriginal leadership in higher education: A new indigenous research paradigm. The Australian Journal of Education, 62(3), 276–288. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004944118808364

- Gheorghiu, E., & Stephens, C. S. (2016). Working with “the others”: Immigrant academics’ acculturation strategies as determinants of perceptions of conflict at work. The Social Science Journal, 53(4), 521–533. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soscij.2016.08.002

- Ghosh, D., & Barber, K. (2021). The gender of multiculturalism: Cultural tokenism and the institutional isolation of immigrant women faculty. Sociological Perspectives, 64(6), 1063–1080. https://doi.org/10.1177/0731121420981098

- Heffernan, T. (2021). Academic networks and career trajectory: “There’s no career in academia without networks.”. Higher Education Research and Development, 40(5), 981–994. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2020.1799948

- Hoque, S., Baker, E. H., & Milner, A. (2021). A quantitative study of race and gender representation within London medical school leadership. International Journal of Medical Education, 12, 94–100. https://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.609d.4db0

- Hughes, C. (2004). Review essay: The “managerial turn” in gender and higher education research: Time for a new language? In Gender and education (Vol. 16(1), pp. 115–123). Taylor and Francis Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1080/0954025032000204715

- Jean-Marie, G. (2011). “Unfinished agendas”: Trends in women of color’s status in higher education. In Women of color in higher education: Turbulent past, promising future (Vol. 9, pp. 3–19). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1479-3644(2011)0000009006

- Johansson, M., & Śliwa, M. (2014). Gender, foreignness and academia: An intersectional analysis of the experiences of foreign women academics in UK business schools. Gender, Work and Organization, 21(1), 18–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12009

- Kim, D., Wolf-Wendel, L., & Twombly, S. (2011). International faculty: Experiences of academic life and productivity in U.S. Universities. The Journal of Higher Education (Columbus), 82(6), 720–747. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2011.11777225

- Le, B. P. (2016). Choosing to lead: Success characteristics of Asian American academic library leaders. Library Management, 37(1/2), 81–90. https://doi.org/10.1108/LM-05-2015-0029

- Lin, A., Grant, R., Kubota, R., Motha, S., Sachs, G., Vandrick, S., & Wong, S. (2004). Women faculty of color in TESOL: Theorizing our lived experiences. TESOL Quarterly, 38(3), 487–504. https://doi.org/10.2307/3588350

- Lipton, B. (2017). Measures of success: Cruel optimism and the paradox of academic women’s participation in Australian higher education. Higher Education Research and Development, 36(3), 486–497. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2017.1290053

- Mamiseishvili, K., & Rosser, V. J. (2010). International and citizen faculty in the United States: An examination of their productivity at research universities. Research in Higher Education, 51(1), 88–107. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-009-9145-8

- Manfredi, S. (2017). Increasing gender diversity in senior roles in he: Who is afraid of positive action? Administrative Sciences, 7(2), https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci7020019

- Manfredi, S., Grisoni, K., Handley, K., Nestor, R., & Cooke, F. (2014). Gender and higher education leadership: Researching the careers of top management programme alumni.

- McTavish, D., & Miller, K. (2009). Management, leadership and gender representation in UK higher and further education. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 24(3), 178–194. https://doi.org/10.1108/17542410910950868

- Michael, S. (2011). In pursuit of excellence, diversity and globalisation: The art of leveraging international assets in academia. In S. Robins, S. Smith, & F. Santini (Eds.), Bridging cultures: International women faculty transforming the US academy (pp. 138–144). University Press of America Ltd.

- Miller, P. (2016). ‘White sanction”, institutional, group and individual interaction in the promotion and progression of black and minority ethnic academics and teachers in England. Power and Education, 8(3), 205–221. https://doi.org/10.1177/1757743816672880

- Monroe, K., Ozyurt, S., Wrigley, T., & Alexander, A. (2008). Gender equality in academia: Bad news from the trenches, and some possible solutions. Perspectives on Politics, 6(2), 215–233. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592708080572

- Morley, L. (2014). Lost leaders: Women in the global academy. Higher Education Research and Development, 33(1), 114–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2013.864611

- Morley, L., & Crossouard, B. (2016). Women’s leadership in the Asian century: Does expansion mean inclusion? Studies in Higher Education, 41(5), 801–814. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2016.1147749

- Nawyn, S., Gjokaj, L., Agbenyiga, D., & Grace, B. (2012). Linguistic isolation, social capital, and immigrant belonging. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 41(3), 255–282. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891241611433623

- Nichols, S., & Stahl, G. (2019). Intersectionality in higher education research: A systematic literature review. Higher Education Research and Development, 38(6), 1255–1268. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2019.1638348

- Oade, A. (2009). Managing workplace bullying: How to identify, respond to and manage bullying behavior in the workplace. Palgrave Macmillan.

- O’Connell, C., & McKinnon, M. (2021). Perceptions of barriers to career progression for academic women in stem. Societies (Basel, Switzerland), 11(2), 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc11020027

- Oloyede, F., Christoffersen, A., & Cornish, T. (2021). Race equality charter review. https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/equality-charters/race-equality-charter/race-equality-charter-update.

- Pasque, P. A. (2011). Feminist theoretical perspectives. In Women of color in higher education: Turbulent past, promising future (Vol. 9, pp. 21–47). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1479-3644(2011)0000009007

- Petticrew, M., & Roberts, H. (2006). Systematic reviews in the social sciences: A practical guide.

- Post, C., Sarala, R., Gatrell, C., & Prescott, J. E. (2020). Advancing theory with review articles. Journal of Management Studies, 57(2), 351–376. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12549

- Prisma. (2020). PRISMA statement. https://www.prisma-statement.org/PRISMAStatement/PRISMAStatement.aspx.

- Probert, B. (2005). I just couldn’t fit it in: Gender and unequal outcomes in academic careers. Gender, Work and Organization, 12(1), 50–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0432.2005.00262.x

- Rollock, N. (2021). I would have become wallpaper Had racism Had Its Way”: Black female professors, racial battle fatigue, and strategies for surviving higher education. Peabody Journal of Education, 96(2), 206–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/0161956X.2021.1905361

- Sang, K., Al-Dajani, H., & Özbilgin, M. (2013). Frayed careers of migrant female professors in British academia: An intersectional perspective. Gender, Work and Organization, 20(2), 158–171. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12014

- Sang, K. J. C., & Calvard, T. (2019). I’m a migrant, but I’m the right sort of migrant’: Hegemonic masculinity, whiteness, and intersectional privilege and (dis)advantage in migratory academic careers. Gender, Work and Organization, 26(10), 1506–1525. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12382

- Spence, C. (2019). Judgement’ versus ‘metrics’ in higher education management. Higher Education, 77(5), 761–775. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-018-0300-z

- Stephens, C. S. (2016). Acculturation contexts: Theorizing on the role of inter-cultural hierarchy in contemporary immigrants’ acculturation strategies. Migration Letters, 13(3), 333–349. https://doi.org/10.33182/ml.v13i3.287

- Stockfelt, S. (2018). We the minority-of-minorities: A narrative inquiry of black female academics in the United Kingdom. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 39(7), 1012–1029. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2018.1454297

- Suárez-McCrink, C. L. (2011). Hispanic women administrators: Self-efficacy factors that influence barriers to their success (Vol. 9, pp. 217–242). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1479-3644(2011)0000009015

- Sue, D. W., & Sue, D. (2003). Counselling the culturally diverse: Theory and practice (4th ed.). Libra Publishers, Inc.

- Torraco, R. J. (2005). Writing integrative literature reviews: Guidelines and examples. Human Resource Development Review, 4(3), 356–367. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484305278283

- Torraco, R. J. (2016). Writing integrative literature reviews: Using the past and present to explore the future. Human Resource Development Review, 15(4), 404–428. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484316671606

- Universities UK. (2022). International facts and figures 2022. https://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/universities-uk-international/insights-and-publications/uuki-publications/international-facts-and-figures-2022.

- Valverde, L. A. (2011). Their path to leadership makes for a better higher education for All. In Women of color in higher education: Turbulent past, promising future (Vol. 9, pp. 49–75). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1479-3644(2011)0000009008

- Westering, A., Speck, R., Sammel, M., Scott, P., Tuton, L., Grisso, J., & Abbuhl, S. (2012). A culture conducive to women’s academic success: Development of a measure. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 87(11), 1622–1631. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31826dbfd1

- Xiao, Y., Pinkney, E., Au, T. K. F., & Yip, P. S. F. (2020). Athena SWAN and gender diversity: A UK-based retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open, 10(2), e032915–e032915. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-032915

- Zhao, J., & Jones, K. (2017). Women and leadership in higher education in China: Discourse and the discursive construction of identity. Administrative Sciences, 7(3), 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci7030021

Appendices

Appendix A. Search terms

EBSCO: business source complete and education source

Proquest: ABI/INFORMand education database

(* OR Ghana* OR Kenya* OR Nigeria* OR Japan* OR Korea* OR China OR Chinese OR Vietnam* OR Malay* OR nationalit* OR immigrant* OR immigrat* OR migrat* OR migrant* OR “global majorit*” OR “national origin*”)

AND tiab(lecturer* OR academ* OR professor* OR “higher education” OR HE OR universit* OR dean)

AND tiab(lead* OR manag* OR progress* OR promot* OR career*)

ERIC & Scopus database

(women* OR woman* OR female* OR gender* OR sex OR sexes) AND (race* OR raci* OR ethnic* OR minorit* OR BAME OR Black OR Asia* OR Caribbean OR “West Indies” OR “West Indian” OR Jamaica* OR Africa* OR Ghana* OR Kenya* OR Nigeria* OR Japan* OR Korea* OR China OR Chinese OR Vietnam* OR Malay* OR nationalit* OR immigrant* OR immigrat* OR migrat* OR migrant* OR “global majority” OR “global majorities” OR “national origin”) AND (lecturer* OR academ* OR professor* OR “higher education” OR HE OR universit* OR dean) AND (lead* OR manag* OR progress* OR promot* OR career*) pubyearmin:2012.