ABSTRACT

This paper highlights an emergent form of gender inequality within schools, set against the backdrop of a perceived mental health “crisis” amongst young people in popular and media narratives. We present interview data collected in a qualitative study with students and staff in secondary schools in England. Through a Foucauldian analytic lens, we interrogate the discourses participants mobilised when discussing girls’ and boys’ experiences of mental ill/health. We demonstrate how girls are paradoxically celebrated for their emotional openness and maturity, yet simultaneously positioned as unfairly advantaged and likely to receive “more” mental health support. In contrast, boys are understood as likely to mask their emotional distress through silence or disruptive behaviours, with fears that their needs might be missed and that boys are an “at risk” group. We also illustrate how girls’ manifestation of emotional distress (e.g. crying, self-harm) becomes feminised and diminished. We ultimately call for increased awareness of gendered discourses surrounding mental health in education and resultant inequalities.

Introduction

In recent times, we have witnessed a number of significant global events that have heightened feelings of fear, uncertainty and risk, such as the Covid-19 pandemic, rise in right-wing populism, economic downturn, and intensifying international conflicts. These events have created an increasingly precarious world in which young people inhabit, with emergent research indicating impacts on young people at the psycho-social level (Newlove-Delgado et al., Citation2022; Winter & Lavis, Citation2022). It is therefore seemingly logical that schools, as key sites where young people spend their formative years, are spaces where mental health and wellbeing issues are addressed. In line with numerous other countries worldwide – particularly in the Global North (Brown & Shay, Citation2021) – educational policy in England has tasked school leaders with putting in place policies, structures and practices to ensure the wellbeing of the young people in their care (Department of Health & Department for Education [DfE], Citation2017; DfE, Citation2018; DfE, Citation2021). Schools are now also assessed on this as part of the revised Ofsted framework (Ofsted, Citation2022). An array of universal, targeted and specialist programmes and interventions are currently being implemented in schools in an attempt to fulfil such policy demands (Norwich et al., Citation2022).

Yet, there is a growing sense of unease amongst a number of critical scholars as to what the increasing prominence of mental health might be “doing” within educational spaces (Allan & Harwood, Citation2022; Brown & Carr, Citation2019; Timimi & Timimi, Citation2022). Researchers identified more than a decade ago a change in orientation of the envisaged philosophical purpose of schooling, with an increasing emphasis being placed on its therapeutic function (Ecclestone & Hayes, Citation2009; Furedi, Citation2004). Thus the aim of schooling is not just to ensure that children acquire academic knowledge and abilities, but to develop emotional intelligence and resilience to help them “cope” later in life. This has been linked with a drive for pedagogic practices and interventions that promote students’ social and emotional competencies such as self-esteem, confidence, empathy, motivation, and emotion management, which have often been referred to as “soft skills” (Ecclestone, Citation2017; Rawdin, Citation2021). Questions have been raised about this shift in emphasis from a number of angles; for example, Ecclestone and Hayes (Citation2009) contend that therapeutic education presents a diminished subjecthood which is disempowering whereby the concept of the “vulnerable” and “fragile” child is normalised. Brown and Carr (Citation2019) argue that a focus on mental health and wellbeing in schools represents an extension of neoliberal rationality and governmentality that individualises responsibility for mental health struggles, and attempts to “cure” a problem caused by the very system that creates intolerable pressures, i.e. through testing and performativity regimes.

Others have begun to question whether mental health ideology is in fact self-perpetuating a “moral panic”. Timimi and Timimi (Citation2022), for example, suggest that due to uncertain understandings of the root cause of mental “illness” within clinical medicine itself, confusion about its meanings and consequences has broadened the remit for what is categorised as mental ill health by educational professionals within school contexts. As a consequence, ordinary emotional challenges that young people encounter as part of growing up such as navigating social relationships and academic pressures have become medicalised, and everyday stress has become a “disorder” that requires specialist help.

Regardless of one’s positioning in relation to debates regarding the growing prevalence of mental ill health amongst young people and the desirability (or potential dangers) of mental health rhetoric, campaigns and initiatives becoming embedded in education, mental health is clearly a central motif within schooling in the current context (Jessiman et al., Citation2022). It is therefore important to consider the impact of the discursive construction of mental health (Foucault, Citation1965, Citation1979) on key educational stakeholders, particularly from student and staff perspectives. This paper seeks to do so through a critical exploration of how mental health discourses intersect with gender discourses in the context of the secondary school in England. At present, relatively little research on mental health in schools has adopted a gendered lens – yet this is an important area for enquiry owing to the potential for school sites to be implicated in the (re)production of gender/health inequalities. The operation of identity is central to how emotions and mental ill/health are experienced and mediated by students, and gender identity formation has been identified as particularly important to young people in school settings (Francis et al., Citation2012; Jackson, Citation2006; Paechter, Citation2021). Therefore, to overlook the potential relationships between gender and mental health appears short-sighted. In the next section, we explore how gender and mental health in intersection have been researched in schools to date across disciplinary perspectives, providing a backdrop for this study.

Gender and mental health in schools: the research landscape

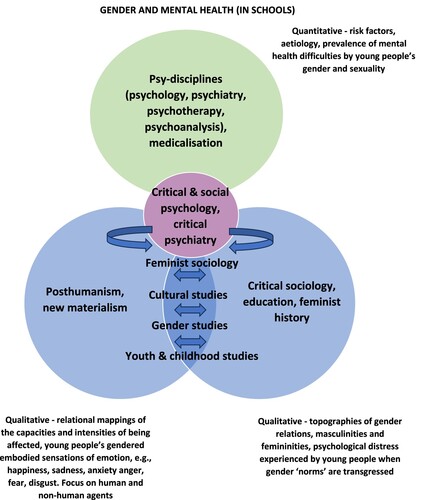

Understandings of mental health are traditionally located within the realm of medicine and the psy-disciplines – psychology, psychiatry, psychotherapy and psychoanalysis (Foucault, Citation1965; Rose, Citation1996). The origin of these disciplines has been traced back to the establishment of modern psychology in the late nineteenth century, but has wider roots in Ancient Greek philosophy and Plato and Aristotle’s thinking regarding memory, perception and learning (Hergenhahn, Citation2009). Traditional modern psychology is often understood to have adopted a natural science model as grounded in a desire to understand universal truths about human behaviour and experience, with the aim being to categorise, measure, regulate and “cure” the sick individual (Rose, Citation1996). Whilst not totalising given the emergence of sub-fields such as social and critical psychology (Billig, Citation2008), these historical imprints are enduring and research that seeks to investigate the phenomenon of mental health in schools – including its aetiology, prevalence, and impact on student outcomes – tends to work from “scientific” approaches. Quantitative methods are often favoured, with substantial bodies of literature evaluating the “efficacy” of interventions designed to prevent or remediate mental health problems amongst particular groups of students or whole-school wellbeing approaches (Weare & Nind, Citation2011).

At present, a growing quantitative literature exists which foregrounds gender in the analysis and seeks to understand the mental health “risk factors” impacting on the academic outcomes of young people of different genders and sexualities (e.g. girls, boys, transgender, non-binary, lesbian, gay, bisexual youth). For example, some studies indicate that girls might be more likely than boys to experience academic performance-related stress and anxiety (Giota & Gustafsson, Citation2017), and that girls with depression are more likely to fail to complete high school (Needham, Citation2009). Other research has demonstrated that LGB youth are more likely to experience anxiety, depression and suicidal ideation due to experiences of exclusion and victimisation, which can be particularly pronounced for transgender and non-binary youth (Rimes et al., Citation2019; Russell & Fish, Citation2016). Studies have established links between LGBTQ + students’ emotional distress and behaviours such as school absenteeism, drop-out, and lower academic attainment (Ancheta et al., Citation2021; Aragon et al., Citation2014; Burton et al., Citation2014).

Alternative approaches are, however, evident when one looks beyond the disciplinary boundary lines of traditional psychology, psychiatry, and medicine. Over the past three decades, research conducted by critical and feminist sociologists and educationalists, cultural and youth researchers, and childhood studies scholars has focused on mapping topographies of gender relations in diverse school contexts, with particular attention paid to students’ “identity work” and performances of gender and sexuality (Kostas, Citation2022; Mac an Ghaill & Haywood, Citation2014; Renold, Citation2005). Mental health as explicitly defined is rarely the focus of analysis, but studies have documented – often as a by-product – the psychological distress experienced by young people in educational settings when gender “norms” are transgressed, whether this be in terms of bodily, academic or social ideals. Scholars have drawn attention to the profound and damaging experiences of exclusion, bullying and alienation encountered by young people who do not conform to heteronormative gender ideals, which can manifest in health “disorders” such as chronic anxiety, depression, eating disorders, and self-harm (Horton, Citation2019; Rich & Evans, Citation2009; Walkerdine et al., Citation2001). This is accompanied by work in the fields of gender studies and feminist history relating to masculinities and femininities, where gendered phenomena such as the “male” discourse of suicide (Jordan & Chandler, Citation2019) and the historical connection between femininity and mental distress or “hysteria” have been troubled (Milne-Smith, Citation2022; Sturkenboom, Citation2000). However, within these areas of research, explicit links are not often made to the context of schooling.

Concomitantly, a growing body of research has paid attention to the role of affect and emotions in education (Dernikos et al., Citation2020; Ringrose, Citation2011; Zembylas, Citation2021), emblematic of the “affective turn” that has taken place in social science more widely (Clough, Citation2007). Here, the aim for educational scholars has often been to map relationally the capacities and intensities of being affected, and student and staff’s embodied sensations of emotion, e.g. happiness, anger, fear, disgust. This serves to “disrupt the Cartesian notion of the self-contained, rational subject by embracing a view of bodies as porous and permeable human and nonhuman assemblages” (Dernikos et al., Citation2020, p. 6). In a rare set of papers writing specifically about girls’ ill-/well-being in schools in Sweden, Lenz Taguchi and Palmer (Citation2013; Citation2014) conduct a diffractive analysis and Deleuzio-Guattarian cartography to understand how the entanglement of medicine, psychology, popular science, media, the narratives of young girls, and the researchers’ personal reflections are agents in the production of schoolgirls’ mental ill health. However, at present there remains a lacuna of educational studies that adopt a critical approach and explicitly interrogate power relations in understandings of gender and mental health in education (for another notable exception, see Pearson, Citation2023). This paper seeks to address this gap (see ).

Figure 1. Simplified diagram depicting dominant fields of study and approaches when researching gender and mental health (in schools).

This paper presents data collected in a qualitative study conducted in two secondary schools in England. Adopting a feminist poststructuralist and Foucauldian analytic lens, we seek to critically interrogate the discourses espoused by students and staff members during semi-structured interviews, focusing specifically on their responses to the following question: “Do you think that girls and boys experience mental health in the same way?”

Theorising gender and mental health

The analysis in this paper is informed by a Foucauldian (Citation1978, Citation1979) understanding of discourse and power, with the individual – or subject – seen as constituted in and through discursive practice. We focus on critically interrogating the plurality of discourses framing gender and mental health in education in intersection that offer students and staff a range of possibilities for subjectivity, meaning-making and intentionality (Weedon, Citation1987; Youdell, Citation2006). This is not, however, to deny that mental “illness” exists or to claim that it is produced solely in language and discourse, for this risks overlooking the very “real” pain and anguish that can be experienced by those with mental health difficulties and the impact on one’s embodied functioning in the social and material world (Shakespeare, Citation2013). We see mental ill/health through a bio-psycho-social theoretical framework (see Stentiford et al., Citation2023), acknowledging the complex interaction between individual and social factors in producing mental illness – but with a specific focus in this paper on the varied discourses (e.g. psychiatric, psychological, sociological) which frame its production as a phenomenon (Strong & Sesma-Vazquez, Citation2015).

In this paper, we also draw on theoretical tools offered by feminist poststructural thinkers who understand gender as a polymorphic concept; not as something that is possessed by the individual in a singular way, but as performatively constituted through dynamic and citational practices (Butler, Citation1990, Citation2004). Intelligible genders are those legitimised through the hegemonic “heterosexual matrix” which prescribes normative masculinities and femininities, and renders unintelligible or “Others” alternative constellations of sex/gender/sexuality (Youdell, Citation2005). We take up this lens in order to read and problematise the data in this study.

Methodology

This paper draws on data gathered in two secondary schools located in the south of England. So that we could access a diversity of student and staff views and consider how local context might shape experiences and understandings of mental health, we purposively recruited two different types of educational setting: a mixed grammar school in a predominantly White, middle-class rural catchment (given the pseudonym Oakford), and a mixed comprehensive school in a predominantly White, working-class urban catchment (given the pseudonym Hollyside). Oakford has a lower number of students on roll on Free School Meals and special educational needs (SEN) support than the national average, whilst Hollyside has a higher number than the national average, respectively. The research took place in autumn 2022 after Covid-19 social distancing restrictions had been lifted in England.

The study was granted ethical clearance by the University of Exeter’s Ethics Committee (No. 513215). We conducted individual semi-structured interviews with staff and students at both school sites. We approached each school’s Headteacher by email and they acted as “gatekeeper” to the site. In order to recruit students to the study, we liaised with senior school leaders and pastoral leads who worked with us to identify students who they felt might be willing to talk with us, from a range of backgrounds. In total, we recruited 34 students (22 in Oakford, and 12 in Hollyside) who were aged between 12 and 17 years. Twenty-nine were of White-British or British-European heritage, 4 of British-Asian heritage, and 1 of British-African heritage. Seventeen students identified as female and 12 as male. Five students in our sample identified as non-binary, gender fluid or something other than their “birth gender”. Students came from a range of social class backgrounds (determined by parental occupations) and there was a mix of young people with and without SEN support. Across the two schools, 19 students self-identified as experiencing, or having previously experienced some form of mental health difficulty. This represented just over half of the students in the sample, and ensured we could elicit views from those with and without lived experience of mental ill health. Information sheets and consent forms were given to both parents and students to sign.

The student interviews were conducted in a private room on school premises so that the young people might feel comfortable discussing potentially sensitive health-related issues. The interviews commenced with biographical questions so that we could gain a broader understanding of the young people’s lives (e.g. families, friendships), and to establish rapport and trust. We moved on to ask about their perceptions of the significance of gender in their school, of mental health, and the intersection of the two. The interviews ranged from approximately 30–45 min. The young people in both schools spoke very articulately and openly about their gender identities and personal experiences of mental health. We also conducted semi-structured interviews with 18 members of staff (9 in Oakford, and 9 in Hollyside), who held roles including Headteacher, school counsellor, SENCO, and classroom teacher. We purposively recruited staff in these roles to understand the perspectives of individuals who might interact with students in different spaces and contexts, and who might have some responsibility for mental health provision. We sought staff as well as student views to facilitate a more holistic understanding of the schools under study and the environment in which the young people were studying. Staff interviews lasted up to an hour and topics covered included the school’s mental health policies, practices and provision, their perceptions of gender issues in the school, and students’ experiences of mental health. In total, we interviewed 52 individuals (students and staff) across the two school locations.

With participants’ permission, all interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed. Transcripts were imported into Nvivo and subject to a Foucauldian discursive analysis (Arribas-Ayllon & Walkerdine, Citation2017), with the analytic lens being harnessed on the “rules and systems” that governed participants’ understandings and articulations of gender and mental health in intersection. Attention was paid to complexity and contradiction within participants’ discursive repertoires, but also silences regarding what was not or seemingly could not be expressed (Khan & MacEachen, Citation2021). This included attending to how problematizations manifest in the data that rendered certain types of thought relating to gender and mental health im/possible, the subject positions from which the participants spoke, and the acts of subjection which constituted participants as subjects (Arribas-Ayllon & Walkerdine, Citation2017).

Student and staff perceptions of young people’s gender and mental health

Our research was designed as attuned to the increasing gender diversity found within school communities (Bragg et al., Citation2018). We therefore asked the students and staff members a number of questions about the perceived experiences of young people identifying as gender/sexually diverse (e.g. LGB, trans, non-binary, gender fluid). However, given that binary understandings of gender are still often used as a classificatory system in English schools and wider society and have been found to be a source of enduring structural inequalities (Francis et al., Citation2017), we also wanted to explore participants’ thoughts in relation to the traditional girl/boy dichotomy. We therefore asked the 52 participants the following question: “Do you think that girls and boys experience mental health in the same way?” We deliberately worded the question openly but offered prompts to help concretise this question where needed, including whether girls and boys might have different “triggers”, pressures, or behavioural responses when they are experiencing mental distress. It is participants’ response to this question that we focus on in this paper. We do so because the answers to this question elicited particularly gender traditional articulations, and the responses of the gender-conforming and gender-diverse students in the sample were remarkably similar. In the following sections, we merge the student and staff views together as the data also revealed a very strong alignment between the perceptions of the student and staff groups.

Gender doesn’t matter: mental health depends on a person’s individual situation

Out of the 52 students and staff in the sample, 9 participants (8 students and 1 teacher) felt that there were no differences between girls’ and boys’ experiences of mental health. Amongst these 9 participants, there tended to be a focus on possible causes and manifestations of mental health difficulties. There was a common perception that gender was less relevant because it was the external situation that young people found themselves in that was important, or that it depended on the individual and how they felt about and responded to certain situations:

I suppose that sort of for most it depends on the situations, it depends on why it happened but yeah, of course they will both experience anxiety but there’s, you know, it can’t just be one gender with one mental health issue and another gender with another, it doesn’t work like that. It depends on … the situation why they are sad … it depends on the way you deal with it I think too. (Lily, Oakford)

I don’t think you can group it into, girls have these reasons for anxiety and boys have these reasons because it’s individual why people feel in a way that they do, and I don’t think that they have different reasons because everybody will have different reasons for why they feel bad. (Dillon, Oakford)

I think male/female, boys/girls’ pressures are going to come as they potentially always have done you know irrespective of the group. It’s a young person growing and evolving and trying to work out where they fit in the world. (Mr Bell, Oakford)

Gender does matter: girls are open about their emotions, but boys will hide them

The majority of our participants (43 out of 52) felt that girls and boys experienced mental health in different ways. Further, a key motif emerged in both the student and staff interview narratives which centred on a traditional binary discourse of gendered emotion and behaviour: Girls are open about their emotions, but boys will hide them. This discourse recurred across the data set over 50 times. What was notable was that this binary discourse appeared totalising, and was the only way in which students and staff appeared able to articulate any perceived relationship or connection between girls’ and boys’ experiences of mental health:

Girls are open about their emotions:

Girls feel overall more free to express their emotions. (Hallie, Oakford)

Girls are more inclined I feel to talk to each other about [mental health] because we’re not told to repress our emotions (Willow, Oakford)

I am forever impressed with, not just at this school, young women’s confidence and assuredness about talking about [emotional] things. (Mr Hughes, Oakford)

Boys hide their emotions:

I know for a fact you always get the guys get taught from a young age to bottle up their feelings. (Calvin, Oakford)

Boys just don’t, they barely tell anyone anything that they don’t want to talk about because they feel like they’ll be looked at and be told the phrase “man up” or “boys don’t cry”. (Kayla, Hollyside)

Sometimes males, you know, having to be that strong person and how they’ve been brought up and not being able to communicate those things. (Ms Young, Oakford)

I have four male friends, three of which have social anxiety but they don’t talk to anyone else about it except for in our friendship group … I think yeah, it's more likely to be held that girls have anxiety because they are generally more open and willing to talk about it.

In the above excerpts, Kayla expresses that boys are often reluctant to talk about their feelings as they would be told “boys don’t cry” or to “man up” – the latter of which was a phrase referenced multiple times by different staff members and students in both Oakford and Hollyside. What is notable is that such traditional gender and emotion constructions are central in much media reporting about mental health (Kale, Citation2022) and the design and messaging of various global mental health initiatives. For example, the Man Up public health intervention in Australia (Pirkis et al., Citation2019) and the MANUP? (Citation2023) social media campaign in England aim to address men’s mental health through reworking masculine stereotypes and encouraging men to “speak up” about their mental health. The framing of such campaigns has been questioned for unintentionally reifying and reinforcing traditional gender stereotypes (Fleming et al., Citation2014), yet these public health and media narratives create a wider context in which dominant understandings of gender and mental health are shaped.

It is also perhaps unsurprising that the students and staff felt that boys are strongly socialised into hiding their emotions given that traditional masculinity links closely with traits such as strength, exertion of control, mental and physical toughness, and emotional detachment, which are seen as relational and oppositional with femininity (Connell, Citation2005). Whilst new and “softer” versions of masculinity have been identified as increasingly apparent and valued within school settings in different countries worldwide (Halvorsen & Ljunggren, Citation2021; Ward, Citation2014), the participants in this study spoke of persistent and troublesome expectations that boys should not show their emotions. Similar findings have been obtained in educational studies conducted with teaching staff, students and health professionals in other schools in England (Pearson, Citation2023), as well as Sweden (Johansson et al., Citation2007; Odenbring, Citation2019) and Finland (Perander et al., Citation2020), indicating the cross-cultural Northern European purchase of dominant understandings of gender and emotion.

What does this dichotomous discourse of gender and emotion do within schools?

In further reflecting on the significance of the gender and emotion dichotomy, a problematization presented itself in our data set that exposed the re-inscription of patriarchal power-knowledge (Foucault, Citation1979). Our analysis revealed two central and contradictory ways in which this dichotomy worked to position girls as both unfairly advantaged over boys, yet simultaneously marginalised in terms of mental health provision and support. We outline these in turn.

A perception that girls are at an advantage over boys in receiving mental health support

Our analysis revealed that the students and staff members tended to position girls in hierarchical relation with boys when it came to mental health, with girls constructed as elevated above boys because of their perceived emotional openness. We identified in the data set an intersecting discourse of girls as being more emotionally mature than boys, with the implication being that girls are “responsible” individuals who would actively look for help when they needed it: “boys just aren’t as mature yet. They still need, you know, some kind of wake-up call [about their mental health]” (Calvin, Oakford). These perceptions align with Rich’s (Citation2018) assertion that girls and young women tend to be constructed as the “ideal” subject in the current neo-liberal “healthism” era, enmeshed with wider postfeminist discourses of girls’ empowerment, self-responsibilisation and self-actualisation. They also align with dominant historical notions of gender, development and adolescence – that girls have long been categorised as growing up more quickly and made responsible for maturing (Dyhouse, Citation2013).

There was also evidence of participants understanding emotional distress as manifesting itself differently in girls and boys in school, with girls more likely to cry or withdraw, and boys more likely to engage in off-task or disruptive behaviours such as “messing around” in class (c.f., Jackson, Citation2006):

If we’re [girls] stressed out in class and I might cry then boys will just sit there and mess around, not really do anything and just talk to their mates, they won’t really show anything. (Amelia, Hollyside)

Girls sometimes put their head on their desk they don’t pay attention. (Jemma, Hollyside)

Mental health challenges might present [in boys] as just constant behavioural issues and perhaps we’re more likely to challenge the behaviour rather than thinking about their mental health in that moment especially if they’re not communicating that they are suffering from anxiety or worries or things going on at home. So, I think with girls maybe it’s identified a bit sooner. (Ms Scott, Hollyside)

Further tensions “bubbled up” in the data with several students (those identifying as boys and girls) expressing explicitly that girls might be at an advantage because they were more likely to confide in others. In fact, there was evidence in the interview narratives of girls being positioned as likely to receive more or better-quality support or treatment for mental health difficulties:

Girls, if they are upset or sad or just not feeing themselves at a moment, they would in my opinion get a lot more support by those around them which it should be the same for boys and girls but I don’t think it is exactly. (Salma, Hollyside)

A lot of girls were encouraged to speak about [their mental health] and in a way, I know the school definitely encourages boys to talk about it as well but yeah, girls definitely are encouraged to talk about it more and do talk about it more. (Abigail, Hollyside)

I think maybe with girls it’s more looked after sort of if they’ve got depression maybe it would be a bit more looked after than boys. (Freddie, Oakford)

Ivor was the only student in our study to claim quite fervently that boys are at a distinct disadvantage:

Girls have it easier, they can get the help easier they can talk about it easier I think and they can, you know, actually get what they need whereas boys don’t, can’t talk about it because they’re taught that and during the, like, the month of mental health awareness month there was no one to talk about it at our school, nothing … .I think men have more pressure on them that would trigger them because they’re taught to you know … they’re taught to hide it and they’re taught to bring in the money have all the have the high-paying jobs have the, look like they are sort of, yeah, women are told that they have to look a certain way but it’s not as bad as men.

| 2. | Girls’ experiences of mental ill health are constructed as less significant than boys’ | ||||

Another point of significance in the data emerged in the context of Hollyside school. Through speaking with staff and students, we established that self-harm was a prevalent issue within the school community, with particularly high rates amongst girls in years 8 and 9 (12–14 years). When asked their thoughts as to possible causes, several staff members attributed the rise to the Covid-19 pandemic and school closures which meant that young people spent an increased amount of time isolated at home and were thought to have been greater influenced by social media. One staff member explained that tailored support had subsequently been put in place at Hollyside to address the issue:

We’ve spent a lot of time researching self-harm workbooks and in the summer we had an external practitioner come in and do work around self-esteem for girls and breaking down barriers of what you see on social media and how you should view yourself. We did that because that was the need we were seeing and that’s what young girls were telling us that they needed. (Ms Woods)

When we spoke with the Headteacher of Hollyside school, Mr Taylor, we gained an insight into how the issue was being understood from a management perspective. What emerged was the perception of a hierarchy of mental health difficulties that ranged in “severity”. What was notable was the way in which self-harm was positioned within this hierarchy of need:

Obviously, we know that suicide is the biggest killer of young men between fourteen and thirty that there is. So, there’s obviously something going wrong where young men are taking their lives. I think what we see more in our school is we probably see more young women struggling visibly by not being able to go into lessons by being visibly upset by low-level self-harm you know so like your scratches, your cuts, your pen nibs, your sharpener blades but I think there is a whole hierarchy … So, when I talk about it I don’t want to seem cold but some of our kids you can see that the cuts are like, there is no serious attempt you know that is a, you know the self-harm is they talk about relief they are not trying to take their lives, they are hurting themselves either for a release or for a cry and then there are the ones where you think actually, they are really seriously trying to hurt themselves by taking an overdose or actually cutting the veins you know the right way etc. So, there’s a whole magnitude.

… they’ve got more strength in [the] CAMHS team … [but] You know that the waiting list at the moment, you’ve got somebody that’s got suicide ideation, somebody that is self-harming and it’s almost to the point where it’s like how serious was the risk on their life? It’s like well what do they need to get to CAMHS, you almost need to get, it’s too late, you need to kill yourself to get an appointment.

The issue of young male suicide is of great concern and importance. Yet critical gender scholars have sought to deconstruct the emergence of a male discourse of suicide that risks homogenising young men’s gender identities and life experiences in an overly simplistic way, overlooking the intersection of background facets such as class, ethnicity, disability and sexuality (Jaworski, Citation2014; Mac an Ghaill & Haywood, Citation2012). Jordan and Chandler (Citation2019) further argue that the male discourse of suicide renders girls’ and young women’s experiences of mental distress less visible or important. Indeed, studies indicate that self-harm is a strong predictor of attempted suicide and can act as a “gateway” (Chan et al., Citation2016; O’Connor et al., Citation2018). The situation is further complexified by the “gender suicide paradox” which is often obscured in popular discourse – statistics demonstrate that girls/women are more likely to attempt suicide than men but are less likely to be successful because the methods men choose tend to be quicker, more violent, and lethal (Bommersbach et al., Citation2022; Freeman et al., Citation2017; O’Connor et al., Citation2018). When this is realised, girls’ “lower-level” self-harm might be reappraised and reworked, with the importance of prevention and provision amplified. The problem, then, with dominant discourses of gender and emotion and mental health is that they come to be construed as self-evident and nuance can be missed.

Conclusion

Educational policy directives are increasingly framing schools as sites for mental health promotion in England and countries across the Global North (Brown & Shay, Citation2021), yet the gendered implications of this shift are yet to be fully examined. Through a critical deconstruction of the discourses mobilised by students and staff in two secondary schools in England, this paper has highlighted a new and emerging form of gender inequality, set against the context of a perceived growing mental health “crisis” amongst young people (Timimi & Timimi, Citation2022). This study indicates that traditional binaristic understandings of gender and emotion dominated powerfully in the schools under study (including amongst the five students who identified as non-binary or gender fluid), and we worked to trouble both the misogynist epistemology of such discourses, and discussed implications in relation to understandings of mental health in schools. In particular, we highlighted the dangers around “emotional” girls being constructed as unfairly advantaged and taking up time and support for mental health difficulties at the expense of boys, who are seen as particularly “at risk” and a hidden problem. Further, we demonstrated how girls’ experiences of self-harm at Hollyside became diminished or trivialised, set against the wider backdrop of a highly pressurised and precarious political and economic climate where NHS support is lacking – with girls’ cut flesh from pen nibs and sharpener blades (unintentionally) constructed as being of lesser importance or seriousness.

The findings are significant as they bring into sharper relief how understandings of mental health are intimately bound up with heteronormative understandings of gender and the operation of gender-power relations, which can result in the de/legitimisation of particular mentally ill/healthy student identities. This has previously gone largely unrecognised in the medical and psychologically-dominated educational literature. This paper has exposed the distinct costs for girls who remain “trapped” within unhelpful discursive chains (Youdell, Citation2006) that result in perceived differences and hierarchies in experiences and treatment. Yet boys also remain constrained within gender and emotion norms which limit recognition and validation of other (e.g. “softer” or “feminine”) masculinities. Overall, there was little to no evidence in students’ or staff’s interview narratives of resistance to, or questioning of the gender and emotion binary that might work to undermine or at least punctuate dominant understandings of mental health, which is a cause for concern. The research thus reminds us of the need to greater and more critically examine the nature and effects of the discursive proliferation of mental health narratives in the context of education, and its impact on specific groups of students.

Questions might be raised as to how the situation described in this paper could be addressed in ways that offer hope for the future. On a practical level, consideration needs to be paid to whether mental health initiatives in schools that target students by gender (such as the workshop on girls’ self-esteem and social media that was introduced at Hollyside) might be helpful in providing targeted support, or mask the complexity and variety of young people’s experiences of mental ill/health – and unintentionally foster resentment amongst some student groups. We ultimately conclude that there needs to be increased awareness amongst educational stakeholders including students, teachers, parents, educational policymakers and academics of the nuance surrounding young people’s gendered perceptions and experiences of mental health – including students with diverse gender and sexual identities to add further nuance to gendered debates and rupture binaristic understandings. We spoke with five students in this study, but larger samples would be beneficial to probe this complexity further, including potential tensions and contradictions in desired/assumed identities. Schools have the potential to play a transformative role in challenging gender and mental health inequalities, but we require greater understanding of emerging trends before this can be realised.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the reviewers for their very helpful comments and suggestions. For the purpose of open access, the authors have applied a CC BY public copyright licence to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising from this submission. The research data supporting this publication are provided within this paper.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Allan, J., & Harwood, J. (2022). On the self: Discourses of mental health and education. Palgrave MacMillan.

- Ancheta, A., Bruzzese, J.-M., & Hughes, T. (2021). The impact of positive school climate on suicidality and mental health among LGBTQ adolescents: A systematic review. The Journal of School Nursing, 37(2), 75–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059840520970847

- Aragon, S., Poteat, P., Espelage, D., & Koenig, B. (2014). The influence of peer victimization on educational outcomes for LGBTQ and non-LGBTQ high school students. Journal of LGBT Youth, 11(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/19361653.2014.840761

- Arribas-Ayllon, M., & Walkerdine, V. (2017). Foucauldian discourse analysis. In C. Willig & W. Stainton Rogers (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative research in psychology (pp. 110–123). SAGE.

- Bartky, S. L. (2013). Foucault, femininity, and the modernization of patriarchal power. In C. McCann & K. Seung-kyung (Eds.), Feminist theory reader: Local and global perspectives (3rd ed., pp. 447–461). Routledge.

- Billig, M. (2008). The hidden roots of critical psychology. Sage.

- Bommersbach, T. J., Rosenheck, R. A., Petrakis, I. L., & Rhee, T. G. (2022). Why are women more likely to attempt suicide than men? Analysis of lifetime suicide attempts among US adults in a nationally representative sample. Journal of Affective Disorders, 311, 157–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.05.096

- Bragg, S., Renold, E., Ringrose, J., & Jackson, C. (2018). ‘More than boy, girl, male, female’: Exploring young people’s views on gender diversity within and beyond school contexts. Sex Education, 18(4), 420–434. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2018.1439373

- Brown, C., & Carr, S. (2019). Education policy and mental weakness: A response to a mental health crisis. Journal of Education Policy, 34(2), 242–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2018.1445293

- Brown, C., & Shay, M. (2021). From resilience to wellbeing: Identity-building as an alternative framework for schools’ role in promoting children’s mental health. Review of Education, 9(2), 599–634. https://doi.org/10.1002/rev3.3264

- Burton, C. M., Marshal, M., & Chisolm, D. (2014). School absenteeism and mental health among sexual minority youth and heterosexual youth. Journal of School Psychology, 52(1), 37–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2013.12.001

- Butler, J. (1990). Gender trouble: Feminism and the subversion of identity. Routledge.

- Butler, J. (2004). Undoing gender. Routledge.

- Chan, M., Bhatti, H., Meader, N., Stockton, S., Evans, J., O’Connor, R. C., Kapur, N., & Kendall, T. (2016). Predicting suicide following self-harm: Systematic review of risk factors and risk scales. British Journal of Psychiatry, 209(04), 277–283. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.115.170050

- Chesler, P. (1972). Women and madness. Doubleday.

- Clough, P. (2007). The affective turn: Theorizing the social. Duke University Press.

- Connell, R. (2005). Masculinities (2nd ed.). Polity.

- De Boise, S., & Hearn, J. (2017). Are men getting more emotional? Critical sociological perspectives on men, masculinities and emotions. The Sociological Review, 65(4), 779–796. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038026116686500

- Department of Health & DfE. (2017). Transforming children and young people’s mental health provision: A green paper. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/664855/Transforming_children_and_young_people_s_mental_health_provision.pdf.

- Dernikos, B., Lesko, N., McCall, S., & Niccolini, A. (2020). Mapping the affective turn in education: Theory, research, and pedagogies. Routledge.

- DfE. (2018). Mental health and behaviour in schools: Departmental advice for school staff. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/755135/Mental_health_and_behaviour_in_schools__.pdf.

- DfE. (2021). Promoting and supporting mental health and wellbeing in schools and colleges. https://www.gov.uk/guidance/mental-health-and-wellbeing-support-in-schools-and-colleges.

- Dyhouse, C. (2013). Girls growing up in late Victorian and Edwardian England. Routledge.

- Ecclestone, K. (2017). Behaviour change policy agendas for ‘vulnerable’ subjectivities: The dangers of therapeutic governance and its new entrepreneurs. Journal of Education Policy, 32(1), 48–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2016.1219768

- Ecclestone, K., & Hayes, D. (2009). The dangerous rise of therapeutic education. Routledge.

- Epstein, D., Elwood, J., Hey, V., & Maw, J. (1998). Schoolboy frictions: Feminism and ‘failing boys’. In D. Epstein, J. Elwood, V. Hey, & J. Maw (Eds.), Failing boys? (pp. 3–19). Open University Press.

- Faludi, S. (1992). Backlash: The undeclared war against women. Vintage.

- Fivush, R., & Buckner, J. (2000). Gender, sadness, and depression: The development of emotional focus through gendered discourse. In A. Fischer (Ed.), Gender and emotion: Social psychological perspectives (pp. 232–253). Cambridge University Press.

- Fleming, P., Lee, J., & Dworkin, S. (2014). “Real men don’t”: Constructions of masculinity and inadvertent harm in public health interventions. American Journal of Public Health, 104(6), 1029–1035. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301820

- Flood, M., Dragiewicz, M., & Pease, B. (2021). Resistance and backlash to gender equality. Australian Journal of Social Issues, 56(3), 393–408. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajs4.137

- Foucault, M. (1965). Madness and civilization. Random House.

- Foucault, M. (1978). The history of sexuality. Pantheon Books.

- Foucault, M. (1979). Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison (A. Sheridan Trans.). Vintage.

- Francis, B., Archer, L., Moote, J., de Witt, J., & Yeomans, L. (2017). Femininity, science, and the denigration of the girly girl. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 38(8), 1097–1110. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2016.1253455

- Francis, B., Burke, P., & Read, B. (2014). The submergence and re-emergence of gender in undergraduate accounts of university experience. Gender and Education, 26(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2013.860433

- Francis, B., Skelton, C., & Read, B. (2012). The identities and practices of high achieving pupils: Negotiating achievement and peer cultures. Continuum.

- Francis, F. (2006). Heroes or zeroes? The discursive positioning of ‘underachieving boys’ in English neo-liberal education policy. Journal of Education Policy, 21(2), 187–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680930500500278

- Freeman, A., Mergl, R., Kohls, E., Székely, A., Gusmao, R., Arensman, E., Koburger, N., Hegerl, U., & Rummel-Kluge, C. (2017). A cross-national study on gender differences in suicide intent. BMC Psychiatry, 17(1), 234. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1398-8

- Furedi, F. (2004). Therapy culture: Cultivating vulnerability in an uncertain age. Routledge.

- Giota, J., & Gustafsson, J. E. (2017). Perceived demands of schooling, stress and mental health: Changes from grade 6 to grade 9 as a function of gender and cognitive ability. Stress and Health, 33(3), 253–266. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2693

- Gonick, M. (2006). Between ‘girl power’ and ‘reviving Ophelia’: Constituting the neoliberal girl subject. NWSA Journal, 18(2), 1–23.

- Halvorsen, P., & Ljunggren, J. (2021). A new generation of business masculinity? Privileged high school boys in a gender egalitarian context. Gender and Education, 33(5), 499–513. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2020.1792845

- Hergenhahn, B. R. (2009). An introduction to the history of psychology. Wadsworth.

- Horton, P. (2019). The bullied boy: Masculinity, embodiment, and the gendered social-ecology of Vietnamese school bullying. Gender and Education, 31(3), 394–407. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2018.1458076

- Jackson, C. (2006). Lads and ladettes in school: Gender and a fear of failure. Open University Press.

- Jaworski, K. (2014). The gender of suicide. Ashgate.

- Jessiman, P., Kidger, J., Spencer, L … , & Limmer, M. (2022). School culture and student mental health: A qualitative study in UK secondary schools. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 619. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-13034-x

- Johansson, A., Brunnberg, E., & Eriksson, C. (2007). Adolescent girls’ and boys’ perceptions of mental health. Journal of Youth Studies, 10(2), 183–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676260601055409

- Jordan, A., & Chandler, A. (2019). Crisis, what crisis? A feminist analysis of discourse on masculinities and suicide. Journal of Gender Studies, 28(4), 462–474. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2018.1510306

- Kale, S. (2022). The people making a difference: The man who set up a mental health walking group for ‘blokes’. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2022/aug/22/the-people-making-a-difference-the-man-who-set-up-a-mental-health-walking-group-for-blokes.

- Khan, T. H., & MacEachen, E. (2021). Foucauldian discourse analysis: Moving beyond a social constructionist analytic. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 20, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069211018009

- Kostas, M. (2022). Real’ boys, sissies and tomboys: Exploring the material-discursive intra-actions of football, bodies, and heteronormative discourses. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 43(1), 63–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2021.1999790

- Lenz Taguchi, H., & Palmer, A. (2013). A more ‘livable’ school? A diffractive analysis of the performative enactments of girls’ ill-/well-being with(in) school environments. Gender and Education, 25(6), 671–687. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2013.829909

- Lenz Taguchi, H., & Palmer, A. (2014). Reading a Deleuzio-Guattarian cartography of young girls’ “school-related” ill-/well-being. Qualitative Inquiry, 20(6), 764–771. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800414530259

- Lorber, J. (2000). Using gender to undo gender: A feminist degendering movement. Feminist Theory, 1(1), 79–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/14647000022229074

- Mac an Ghaill, M., & Haywood, C. (2012). Understanding boys’: Thinking through boys, masculinity and suicide. Social Science & Medicine, 74(4), 482–489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.07.036

- Mac an Ghaill, M., & Haywood, C. (2014). Pakistani and Bangladeshi young men: Re-racialization, class and masculinity within the neo-liberal school. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 35(5), 753–776. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2014.919848

- MANUP? (2023, May 15). Men, talking to men. https://www.manup.how/.

- McRobbie, A. (2009). The aftermath of feminism: Gender, culture and social change. Sage.

- Milne-Smith, A. (2022). Gender and madness in nineteenth-century Britain. History Compass, 20(11), e12754. https://doi.org/10.1111/hic3.12754

- Needham, B. (2009). Adolescent depressive symptomatology and young adult educational attainment: An examination of gender differences. Journal of Adolescent Health, 45(2), 179–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.12.015

- Newlove-Delgado, T., Marcheselli, F., Williams, T., Mandalia, D., Davis, J., McManus, S., Savic, M., Treloar, W., & Ford, T. (2022). Mental health of children and young people in England, 2022. NHS Digital. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/mental-health-of-children-and-young-people-in-england/2022-follow-up-to-the-2017-survey.

- Norwich, B., Moore, D., Stentiford, L., & Hall, D. (2022). A critical consideration of ‘mental health and wellbeing’ in education: Thinking about school aims in terms of wellbeing. British Educational Research Journal, 48(4), 803–820. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3795

- O’Connor, R., Wetherall, K., Cleare, S., Eschle, S., Drummond, J., Ferguson, E., O’Connor, D., & O’Carroll, R. (2018). Suicide attempts and non-suicidal self-harm: National prevalence study of young adults. BJPsych Open, 4(3), 142–148. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2018.14

- Odenbring, Y. (2019). Strong boys and supergirls? School professionals’ perceptions of students’ mental health and gender in secondary school. Education Inquiry, 10(3), 258–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/20004508.2018.1558665

- Ofsted. (2022). Education inspection framework. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/education-inspection-framework#full-publication-update-history.

- Paechter, C. (2021). Implications for gender and education research arising out of changing ideas about gender. Gender and Education, 33(5), 610–624. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2020.1798361

- Pearson, R. (2023). Masculinity and emotionality in education: Critical reflections on discourses of boys' behaviour and mental health. Educational Review, 75(6), 1101–1130.

- Perander, K., Londen, M., & Holm, G. (2020). Anxious girls and laid-back boys: Teachers’ and study counsellors’ gendered perceptions of students. Cambridge Journal of Education, 50(2), 185–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2019.1653825

- Phipps, A. (2017). (Re)theorising laddish masculinities in higher education. Gender and Education, 29(7), 815–830. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2016.1171298

- Pirkis, J., Schlichthorst, M., King, K., Lockley, A., Keogh, L., Reifels, L., Spittal, M., & Phelps, A. (2019). Looking for the ‘active ingredients’ in a men’s mental health promotion intervention. Advances in Mental Health, 17(2), 135–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/18387357.2018.1526095

- Pomerantz, S., Raby, R., & Stefanik, A. (2013). Girls run the world? Caught between sexism and postfeminism in school. Gender & Society, 27(2), 185–207. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243212473199

- Rawdin, C. (2021). Towards neuroparenting? An analysis of the discourses underpinning social and emotional learning (SEL) initiatives in English schools. Educational Review, 73(3), 279–296. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2018.1557598

- Renold, E. (2005). Girls, boys and junior sexualities: Exploring children’s gender and sexual relations in the primary school. RoutledgeFalmer.

- Rich, E. (2018). Gender, health and physical activity in the digital age: Between postfeminism and pedagogical possibilities. Sport, Education and Society, 23(8), 736–747. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2018.1497593

- Rich, E., & Evans, J. (2009). Now I am NObody, see me for who I am: The paradox of performativity. Gender and Education, 21(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540250802213131

- Rimes, K., Goodship, N., Ussher, G., Baker, D., & West, E. (2019). Non-binary and binary transgender youth: Comparison of mental health, self-harm, suicidality, substance use and victimization experiences. International Journal of Transgenderism, 20(2-3), 230–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2017.1370627

- Ringrose, J. (2011). Beyond discourse? Using Deleuze and Guattari’s schizoanalysis to explore affective assemblages, heterosexually striated space, and lines of flight online and at school. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 43(6), 598–618. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-5812.2009.00601.x

- Rose, N. (1996). Inventing our selves: Psychology, power, and personhood. Cambridge University Press.

- Russell, S., & Fish, J. (2016). Mental health in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) youth. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 12(1), 465–487. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-093153

- Shakespeare, T. (2013). Disability rights and wrongs revisited. Routledge.

- Stentiford, L., Koutsouris, G., & Allan, A. (2023). Girls, mental health and academic achievement: A qualitative systematic review. Educational Review, 75(6), 1224–1254. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2021.2007052

- Strong, T., & Sesma-Vazquez, M. (2015). Discourses on children’s mental health: A critical review. In M. O’Reilly & J. N. Lester (Eds.), The palgrave handbook of child mental health (pp. 99–116). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Sturkenboom, D. (2000). Historicizing the gender of emotions: Changing perceptions in Dutch Enlightenment thought. Journal of Social History, 34(1), 55–75. https://doi.org/10.1353/jsh.2000.0125

- Tasca, C., Rapetti, M., Carta, M. G., & Fadda, B. (2012). Women and hysteria in the history of mental health. Clinical Practice & Epidemiology in Mental Health, 8(1), 110–119. https://doi.org/10.2174/1745017901208010110

- Timimi, S., & Timimi, Z. (2022). The dangers of mental health promotion in schools. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 56(1), 12–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9752.12639

- Walkerdine, V., Lucey, H., & Melody, J. (2001). Growing up girl: Psychosocial explorations of gender and class. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ward, M. (2014). I'm a geek I am’: Academic achievement and the performance of a studious working-class masculinity. Gender and Education, 26(7), 709–725. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2014.953918

- Weare, K., & Nind, M. (2011). Mental health promotion and problem prevention in schools: What does the evidence say? Health Promotion International, 26(1), i29–i69. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dar075

- Weedon, C. (1987). Feminist practice and poststructuralist theory. Blackwell Publishers.

- Winter, R., & Lavis, A. (2022). The impact of COVID-19 on young people’s mental health in the UK: Key insights from social media using online ethnography. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(1), 352. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010352

- Youdell, D. (2005). Sex-gender-sexuality: How sex, gender and sexuality constellations are constituted in secondary schools. Gender and Education, 17(3), 249–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540250500145148

- Youdell, D. (2006). Impossible bodies, impossible selves: Exclusions and student subjectivities. Springer.

- Zembylas, M. (2021). The affective dimension of everyday resistance: Implications for critical pedagogy in engaging with neoliberalism’s educational impact. Critical Studies in Education, 62(2), 211–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2019.1617180