You have been an executive editor of Environment magazine and still follow it closely. Would you briefly describe what you feel is the magazine’s importance and its role in the environmental movement?

Environment has long occupied a critical niche in the larger ecosystem of environmental science, policy, advocacy, and professional practice. It uniquely publishes original research and thought leadership articles that are often rooted in scientific research but that are framed and written to be accessible to wider audiences, helping to break down the silos between academic disciplines and between academia and the world of environmental practice.

You are the founder and director of the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication. Would you briefly describe why you started the program and what you think is its main mission?

My career has been devoted to the science and practice of climate change communication. In the early 1990s, I was lucky to have a job working with many of the world’s leading scientists to advance scientific knowledge about climate change at the Aspen Global Change Institute. There, I soon confronted the enormous gap between the scientific understanding of the potentially catastrophic risks of global warming and society’s tepid response.

I subsequently earned a PhD at the University of Oregon, studying with Paul Slovic, one of the founders of the field of risk perception, decision making, and communication, seeking to understand why scientific findings so often fail to reach or engage the public and policymakers, and how to develop more effective communication strategies.

I later joined the Yale School of the Environment, where I founded the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication, which helps to build public and political will for climate action in the United States and around the world. We conduct scientific studies on public climate change knowledge, attitudes, policy support, and behavior, and the psychological, cultural, and political factors that drive them. We then apply this research by developing communication strategies to engage key audiences in climate change science and solutions. We work with governments, the media, educators, companies, and advocacy organizations to implement these insights in their own communication campaigns. Finally, we directly engage the general public via Yale Climate Connections, an online news service and radio program on climate science and solutions, broadcast each day on nearly 750 stations nationwide.

You pioneered the notion of “Global Warming’s Six Americas” in 2009. What are those six Americas? Of what use has that been in understanding how Americans feel about climate change?

In 2008, we and our partners at George Mason University’s Center for Climate Change Communication conducted our first nationally representative survey in our “Climate Change in the American Mind” project. We have conducted two national surveys each year since then.

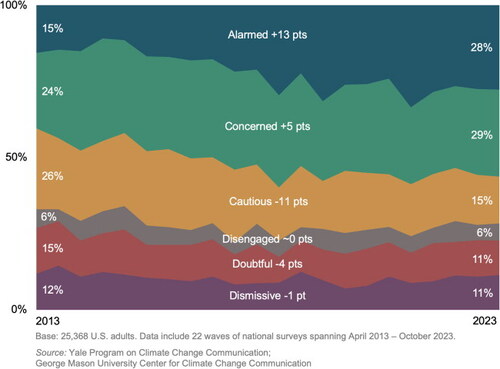

One of the first rules of effective communication is to “know your audience.” Thus, climate change public engagement efforts must recognize that people are different and have different psychological, cultural, and political reasons for acting—or not acting—to reduce carbon emissions. Our early research identified “Global Warming’s Six Americas”: six unique audiences within the American public that each responds to the issue in their own distinct way.

The Alarmed are convinced global warming is happening, human-caused, an urgent threat, and they strongly support climate policies. Most, however, do not know what they or others can do to solve the problem. The Concerned think human-caused global warming is happening, is a serious threat, and support climate policies. However, they tend to believe that climate impacts are still distant in time and space, thus climate change remains a lower priority issue. The Cautious have not yet made up their minds: Is global warming happening? Is it human-caused? Is it serious? The Disengaged know little about global warming. They rarely or never hear about it in the media. The Doubtful do not think global warming is happening or they believe it is just a natural cycle. They do not think much about the issue or consider it a serious risk. The Dismissive believe global warming is not happening, not human-caused or a threat, and most endorse conspiracy theories (e.g., “global warming is a hoax”).

The Six Americas framework and insights are now used by governments, journalists, companies, and educators nationwide to better understand and engage their own audiences. This audience segmentation approach has also been adapted in other countries around the world.

In 2023 you found that Americans are more than twice as likely to be Alarmed or Concerned than they are Doubtful or Dismissive. What implications do you draw from that?

Ten years ago, the Alarmed and Dismissive (the most engaged segments) were roughly equal in size—that is, for every one Alarmed American there was one Dismissive American. We’ve been tracking the changing proportions of all six groups over time. Our most recent study found that the Alarmed now outnumber the Dismissive nearly three to one. The Dismissive haven’t really changed in size over that period—the change has been driven by millions of Americans becoming Alarmed (and Concerned) about global warming. This reflects a fundamental shift in the underlying social, cultural, and political climate of climate change, making climate action more likely, ambitious, and durable.

You state that public opinion plays a critical role in the American response to global warming, and your data show that Americans, by a two-to-one margin, are at least somewhat concerned. How do you account for the fact that our policies seem to lag behind that understanding?

I actually think our policies reflect, in part, that shift in public opinion. It’s no coincidence that climate change has become a top priority of the Democratic Party, leading, among other things, to the passage (barely) of the Inflation Reduction Act, the single biggest national investment in climate action in history. Likewise, the past few years have seen major new policies adopted at state and local levels across the United States. It’s still not at the speed and scale we need to limit future warming to “safe” levels, but there has been great progress.

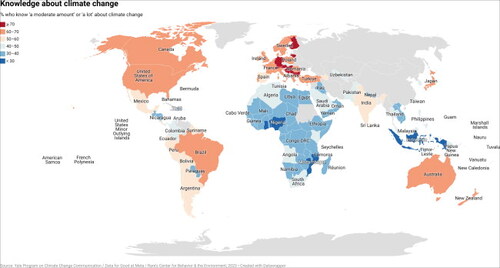

You also study the international response to climate change. In your 2023 study you found that when given a short definition of climate change, more than 50% of respondents in every country surveyed felt that climate change was happening, with more than 90% in many countries believing in it. Why do world leaders seem not to respond to this?

We also found that about 4 out of 10 people worldwide still know little to nothing about climate change, which is roughly 2 billion people. And these are often the most vulnerable, who have contributed the least to the causes of climate change but are getting hit first and worst by the impacts. And many more people worldwide still don’t understand that climate change is human-caused, or they perceive it as a problem distant in time and space.

Each country is unique, of course, so there’s no simple answer to your question. But as a broad-brush response, I suspect many world leaders do not believe they have a public mandate to prioritize climate change over other pressing issues. But that is changing, especially as citizens come to fully grok the dangers of increasing global warming, generating public demand (public will) for climate action.

You have a very detailed analysis of the opinions about climate change in many countries. What is the value of these data? What is the best use of the information you have gathered?

One of the great pleasures of this work, which was totally unexpected, is the diversity of people who have found it valuable in their own efforts to engage audiences in climate change. We’ve been fortunate not just to contribute our research to the scientific literature, but to work with governments ranging from the United Nations to federal, state, and local levels, companies large and small, journalists and weathercasters, educators, advocates, medical professionals, religious leaders, and creatives ranging from film and television, to novelists, poets, musicians, playwrights, comedians, and even ballet and hip-hop dancers! So many amazing people and organizations doing such incredible and important work. We’re just glad that they continue to find our research helpful. Some use it to develop their communication goals and objectives. Others use it to design their strategy and tactics. Many also use our research and tools to measure and evaluate their success.

More than 90% of the population in Puerto Rico and El Salvador feel that climate change should be a “very high” or “high” priority. Why do you think the proportion is so high there?

We’ve generally found that people in Central and South America are more worried about climate change than anywhere else in the world. Likewise, we’ve found that Latinos in the United States are more worried about climate change than any other demographic groups. This isn’t simply because they have experienced climate-fueled extreme events, which have happened worldwide. We think there’s something deeply social and cultural in these communities that shapes these responses. It’s an active area of study.

Do you see any correlation between attitudes about climate change and other variables, such as income levels, levels of education, or others?

That very much depends on where you are in the world. In a global studyFootnote1 we conducted several years ago, education was the single strongest predictor of climate change awareness worldwide. But in the United States, it’s often political ideology that is a strong driver of public responses.

You have also done a great deal of work on educational materials. Do you have any sense of how effective these materials have been? Has their use been growing over the years that you have made them available?

Yes, we’ve produced analyses, educational materials, and tools that have been used by both formal (e.g., K–12 and universities) and informal educators (e.g., science museums, zoos, aquariums, etc.) across the country. Many educators really like using our online SASSYFootnote2 tool, which allows anyone to identify the Six Americas status of their audience with just four questions. And lots use our Yale Climate Opinion Maps,Footnote3 which provide accurate estimates of public opinion for all 50 states, 435 congressional districts, 1,000+ metro areas, and 3,000+ counties nationwide—helping students investigate public views in their own community and then conduct their own informal surveys or learn basic statistics using the downloadable data. Our Yale Climate Connections short radio stories, which are available on our website,Footnote4 are being used by educators to spark class discussions and activities for their students. One major city school district actually embedded more than 30 stories into their environmental chemistry curriculum, to bring abstract scientific concepts to life. For example, students learn the chemistry of ocean acidification and then listen to a story featuring an oyster fisherman talking about how it’s affecting their livelihood.

One of your very interesting initiatives is storytelling as a way of presenting complex information. How extensive is your work in storytelling, and what can you tell us about its effectiveness? Are there key elements for effective stories? Has its use been growing?

Despite all of our technological marvels, from the printing press to ChatGPT, one of the most powerful forms of communication remains storytelling, which humans have been doing since the Stone Age. Stories inform, they persuade, they warn, they model behavior, they transmit culture, and so much more. Storytelling is the essence of Climate Connections, our national radio program. At best, stories engage our heads, hearts, and hands—our full humanity. Our storytelling tries to amplify the voices of people from every walk of life, describing how climate change is already impacting their lives and the people, places, and things they care about, right here, right now. And the voices of people from every walk of life describing how they are not just sitting on the sidelines watching the world burn, but are rolling up their sleeves, getting involved, taking action, and making a difference in their sphere of influence, whatever that is. We know from our experimental studies that these stories are very engaging, including across partisan divides. Humans are storytelling animals and narratives shape our behaviors, from the individual to the national and global scales.

You are a pioneer in this work. Do you know of other organizations or schools doing similar work?

It’s been so exciting to see the field of climate communication grow over the years, building on the incredible work of so many researchers and practioners before us, often in other domains. There are too many individual scholars and programs to list, but I’ll highlight just a few, especially our dear friends and colleagues at the Center for Climate Change Communication at George Mason, who have been our co-researchers on much of our work in the United States. The Annenberg School at U Penn has just launched a new climate communication program, and there are now excellent programs around the world, including at Cardiff University in the United Kingdom, Monash University in Australia, and Peking University in China. The Climate Advocacy Lab, Climate Access, and Climate Outreach are amazing networks of practitioners in the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom. And there are so many more.

Finally, to sum up, what impact do you think your work has had? And what lies in the future? What new ideas are you exploring?

I hope that we’ve helped advance scientific knowledge, even if just a little. And more importantly, that our work continues to empower the climate community in our fight to preserve a safe and stable climate for humanity and the more-than-human world.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Alan McGowan

Alan H. McGowan is an assistant professor (part-time) in the Environmental Studies Program at the New School in New York City.