Abstract

The deeply embedded inequalities in gender which mark most contemporary societies have led to a world shaped by male perspectives. This world fails to accommodate adequately the needs and experiences of women: no more evident than in the transport sector, where a ‘default male’ perspective dominates the planning and policies that shape our roads, railways, airlines, and shipping. This paper argues that the ways in which masculinity infuses transport systems mean they are integral to debates on gender and work. They impact both the way women experience travel and their access to places of work. A multi-transport domain scoping study has been conducted to review the literature for key gender factors that influence the use of road, rail, aviation, and maritime transport modes. A multi-disciplinary approach is proposed which incorporates perspectives and methods from the social sciences that can help to foster Gender-Equitable Human Factors (GE-HF).

Practitioner summary: This paper seeks to identify the gender issues related to transport and work. A scoping review provides key factors that detail how women are disadvantaged by current transport systems. It presents gaps in knowledge that future research needs to fill. Women must be included in key decisions within the transport sector.

1. Introduction

In 1966, James Brown sang ‘This is a man’s world…’ and over six decades later the world is still designed for men (Criado-Perez Citation2019) in an economy built by and for men (Marçal Citation2021). Human Factors (HF) have a vital role to play in changing society so that 51% of the population are no longer marginalised and under-represented in policy, products, protection, and the provision of basic human needs (Madeira-Revell et al. Citation2021). To do this requires a conscious shift from the ‘default male’ thinking currently pervasive in society (Criado-Perez Citation2019; Sanchez de Madariaga Citation2013). This is an active process that takes time, attention, commitment, and support to develop different ways of working to produce a different outcome.

Transportation networks are central to the economic functioning of society (Cho et al. Citation2001; Ham, Kim, and Boyce Citation2005), not least through the kinds of work people can access. The United Nations has incorporated transport accessibility and equality as a sustainable development goal, recognising the influence that transport modes can have on social and economic inclusion (Pooley Citation2016), especially with respect to gender (Peake Citation2019). With everyone needing transport for their daily lives, equality of experience across transport modes should be guaranteed. Yet, it is evident that there are gender factors that influence the use and experience of different transport modes (Hamilton and Jenkins Citation2000; Sanchez de Madariaga Citation2013; Levy Citation2013; Vasquez-Henriquez, Graells-Garrido, and Caro Citation2019). Routinely, it is women who are inconvenienced and suffer from exclusion (Hamilton and Jenkins Citation2000; Simmons Citation2019).

There is a growing awareness that future transport equality, and consequentially future economic equality, requires better representation of women’s needs within the decision making and planning processes of transport systems (Dobbs Citation2007; Sanchez de Madariaga Citation2013; Kuttler and Moraglio Citation2020; Kronsell et al. Citation2020; Winslott Hiselius et al. Citation2019; Madeira-Revell et al. Citation2021; Read et al. Citation2022). Their exclusion can, in part, be explained by the lack of women in senior roles within the sector, who may be better able to identify women’s imperatives. For example, the European Economic and Social Committee (Citation2015) has highlighted the importance of female perspectives in policy-making which has historically been lacking: female workers comprise only 20% of workers in the UK transport sector, typically occupying lower positions of responsibility and pay (European Commission Citation2017; DfT Citation2020a). However, employment in the sector is only part of the picture. Also important to consider is the broad and complex range of factors that produce the systemic gender inequalities which pattern contemporary societies, economies, and policy-making. These include inter alia, culture, power and representations, the division of labour and care, and violence against women. This complexity means that we need to know very much more about how both gender: the socially produced differences between being feminine and being masculine, such as who takes the burden for domestic duties, who works in which occupations, and so on; and sex: the biological differences between men and women, such as pregnancy, menopause, etc., impact on mobility and transport choices.

Overcoming transport’s deeply entrenched gendered inequalities will be no quick fix. Within the academic community, we argue that gender equitable research is required to aid understanding of, where, and how, gender and sex need to be considered (Nowatzki and Grant Citation2011; Nieuwenhoven and Klinge Citation2010; Criado-Perez Citation2019; Madeira-Revell et al. Citation2021; Read et al. Citation2022). In many research areas, the relevance of sex and/or gender may be obvious. Yet, all too often gender has an indirect impact on the area of study, which may not be immediately evident but can lead to significant gender biases further down the line, as is evident in the non-inclusive transport networks we currently have today. For example, Sanchez de Madariaga (Citation2013) highlights that transport planning often prioritises employment-related mobility and its purpose of facilitating travel to and from places of work. Yet, gendered analysis of the reasons people travel identifies a large portion of travel is for the purposes of care work; activities involved in everyday life including domestic jobs and care for the young, old and sick. These trips are more routinely conducted by women alongside their employment commitments and, as transport planning has traditionally held a default male approach, these trips have routinely been ignored. Sanchez de Madariaga (Citation2013) provides evidence that transport has been developed based on an economy that does not value care work, despite it being a compulsory purpose for travel. Socio-economic barriers further compound the issue, limiting access to jobs and care giving activities (Gates et al. Citation2019).

HF must do more to understand the gender-related factors that impinge upon work performance. Gaining insight from other disciplines can help to capture a more complex understanding (Robinson et al. Citation2016). Through a collaboration of HF and Social Science researchers, this paper presents the complementary nature of Sociology and HF approaches to capture a broad societal view of diversity and inequality issues (Ackerley and True Citation2019). Feminist Social Science in particular takes questions of gender and social organisation as core, rigorously interrogating every aspect of everyday practices through a gendered lens (Holmes Citation2008). The aim is to expose how assumptions about gender differences infuse social life, but also how women may be rendered invisible (Criado-Perez Citation2019).

This scoping review aims to map the terrain for the Gender Equitable Human Factors (GE-HF) research now needed in the transport sector. To achieve this, we will review the literature for key gender factors that are relevant across seven transportation modes. Madeira-Revell et al. (Citation2021) identified gender-related factors in transportation that were inferred within the ‘EU gender in research toolkit’ to outline a checklist for inclusion of gender throughout the research process (Yellow Window Citation2018). provides a description of each of these factors. We aim to use these to (i) understand the current gender-relevant areas across the different transport modes and (ii) identify areas where further research is required to close the ‘gender data gap’ in transport and work research.

Table 1. Description of the gender factors related to transportation research.

2. Method

A literature search was undertaken to identify the current state of knowledge on gender across various transport modes in relation to the factors in . A scoping review was conducted to provide an overview of the literature and map it to key factors and themes (Arksey and O’Malley Citation2005). The four main transportation categories included: road, rail, aviation, and maritime; with road transport including personal road vehicles, pedestrians, cyclists, and buses. Rail transport focuses specifically on trains (trams were out of scope for this review).

2.1. Scoping literature review

The literature was reviewed by experts from each of the transport domains. Researchers in HF, Sociology and Engineering had a combined number of 31 years of experience in road, rail, aviation, and maritime transport domains. Google Scholar (GS) and Web of Science (WoS) were chosen as the search platforms. The scoping review aimed to capture the research that has already been conducted, as well as identify where there are gaps. These gaps may be presented in discussion pieces but not officially researched and published in the academic literature. GS was used due to its liberal inclusion of research material, therefore, we took a broad view of the research material identified from this search platform. GS was used as a starting point to understand the literature available across the different modes. WoS was then used to ensure comprehensive access to peer-reviewed articles that related to the themes across each of the transport modes.

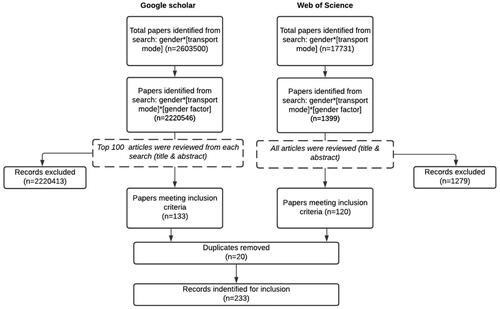

Due to the nature of a scoping review, research with varying methodologies and approaches was reviewed (Arksey and O’Malley Citation2005; Pham et al. Citation2014). This aimed to provide an overview of the literature and map out key areas of relevance to the gender factors across each of the transport modes reviewed. The processes employed in the scoping study, as outlined by Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005) are presented in . This approach supports a descriptive approach that can help identify and inform the factors to be considered in a more detailed systematic review.

Table 2. Method for applying the Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005) processes of a scoping review.

2.1.1. Search terms

Independent searches were conducted for every transport mode across each of the different gender factors. The search terms were selected following a pilot search by the researchers to review the best terms that captured the transport modes and gender factors. shows the terms that were included in the search and those removed following the results from the pilot search. Terms were excluded either due to generating minimal results or being too generic and therefore generating multiple irrelevant themes. For example, ‘car’ was used instead of ‘driving’ or ‘vehicle’ as these terms have alternative meanings that confused the results with those outside transportation. Only one search term was used per gender factor.

Table 3. Search terms included/excluded as identified in a pilot search.

2.1.2. Inclusion/exclusion criteria

The results were first filtered to only include research since the year 2000. When reviewing the remaining search results the research team used set criteria to determine which papers were relevant to the gender factors under review. The criteria stated:

The transport mode is the main mode under analysis. Studies where interactions between modes or where multiple modes were reviewed were not included.

Gender is a substantial part of the analysis or the purpose and/or outcome of the study.

The gender factor is the (or one of a few) primary focus of the paper, i.e. not just a minor variable.

The text must be in English or have an English translation (due to the native language of the researchers).

As the research team was UK-based, we were also interested in research and discussion across different countries and cultures as ideas in non-Western countries were likely to differ and expose further gaps in research and knowledge. The results were sorted by relevance and only the first 100 papers from these search results in GS were reviewed due to the volume of results. In WoS, all results were reviewed as there were less of them and they were all peer-reviewed. During the pilot searches, it was deemed that after 100 papers the results became progressively less relevant to the search. As this was intended to be a scoping review, we were interested in the most relevant papers to the search terms to get an overview of the research themes and gender factors. The title and the abstract of the paper were initially reviewed to determine inclusion/exclusion. If it could not be determined from the abstract alone, the full paper was read. If the paper did not meet one of the inclusion criteria stated above then it was excluded. If a paper met all the inclusion criteria, the manuscript was reviewed in full. A working document was accessed by all researchers to record the papers that met the inclusion criteria. The records included the paper title, authors, year, methodological approach, and a summary of the findings related to the gender factor it related to. Links to the full paper were also provided.

2.1.3. Identifying sub-themes

The primary researcher read all the papers that met the inclusion criteria in full. They reviewed their relevance to the factors (using descriptions in ) and then determined common and/or diverging themes that arose within the findings. They then proposed a set of sub-themes that captured the key areas of focus in the literature. These were then discussed and reviewed by all other members of the research team until a consensus was reached on the number of themes, their meaning, and definitions.

3. Results

3.1. Search results

An overview of the literature search, presented in the ‘preferred reporting items for systemic reviews’ format set by Moher et al. (Citation2009 ), is shown in . This shows the total number of papers identified in GS and WoS when searching for gender across all the transport modes (sum of searches for the top section of ) and the total number of papers when the search terms for the key factors were applied for all transport modes (sum of searches for the bottom section of ). The substantial number of initial search results in GS is indicative of the liberal approach and a vast number of non-academic journal sources. GS and WoS identified a total of 133 and 120 papers, respectively that met the inclusion criteria. Removing 20 duplicates meant that 233 papers were included in the scoping review.

Figure 1. Overview of search results outputs (adapted from Moher et al. Citation2009).

A breakdown of the number of papers identified in relation to each of the gender search terms across each of the transport modes is presented in . This shows that ‘Safety and Perceived Safety’ identified the most number of papers (N = 60) that met the inclusion criteria. With ‘Urban structures’ identifying the next highest number (N = 46). ‘User behaviour’, ‘Mobility needs’, and ‘Family norms’ identified the least number of papers, but were very similar with 33, 34, and 38, respectively. Road transport was the mode that had the most number of research papers identified across all gender factors (N = 69), followed by cycling (N = 56). While rail (N = 13) and bus (N = 15) had considerably less results.

Table 4. Frequency of results found from the Web of Science (WoS) and Google Scholar (GS) search in relation to gender for each transport mode.

A summary of each of the most cited factors for each of the transport modes is now provided to present how each factor relates to transport use. ‘Ergonomics’ was the most cited factor in road vehicle transportation (N = 19). These papers captured the ergonomic design of vehicles which has tended to take a default male approach to the measurement and vehicle testing requirements. The representation of the male body to capture the adult population has been evidenced within the European Commission for Europe (ECE) and has had severe consequences for women who are more likely to suffer from whiplash-related injuries (Linder and Svedberg Citation2019). Reactive head restraints were found to reduce permanent impairment in male drivers by 70% but increased impairment in females by 13% (Kullgren, Stigson, and Krafft Citation2013). Furthermore, Bose, Segui-Gomez, and Crandall (Citation2011) reported that females were 47% more likely to suffer a serious injury in the vehicle while wearing a seatbelt than males in comparable crashes.

‘Family roles’ also identified a large number of citations for road vehicles (N = 15), more than for any other transport mode. The papers identified reference the use of the family vehicle to perform chauffeuring trips. Men are more likely to have priority over the family car (Naess Citation2008; Scheiner and Holz-Rau Citation2012), yet as the number of children in the household increases, the number of car trips that women make increases, while for men it decreases (Vance, Buchheim, and Brockfeld Citation2005). Boarnet and Hsu (Citation2015) describe this as the ‘within-household, female-male chauffeuring gap’, finding that women in households with children make over 300% more chauffeuring trips in the car than men who live alone.

‘Safety and Perceived Safety’ identified several references for the pedestrians (N = 12) and public transport modes (bus; N = 5, rail; N = 8) that cite the enhanced risks women experience when travelling by public transport or walking, especially at night (Vanier and De Jubainville Citation2017; Ceccato and Paz Citation2017; Schmucki Citation2012). Research shows that women often choose more independent and private travel modes, such as vehicles and cycling, to avoid exposure to potential offenders (Stark and Meschik Citation2018; Bonham and Wilson Citation2012). Aviation also had several ‘safety and perceived safety’ references (N = 14), yet the citations identified here relate to the safety of the aircraft, with women being more concerned with flight safety (e.g. Boksberger, Bieger, and Laesser Citation2007; Clemes, Kao, and Choong Citation2008; Rose et al. Citation2012). There were also several safety concerns in the cycling literature, with women feeling more unsafe and safety conscious when cycling compared to men (ARUP and Sustrans Citation2019; DfT Citation2020b; Haynes et al. Citation2019). There was also the suggestion that female cyclists were more likely to be involved in dangerous conflicts at intersections (Evans et al. Citation2018; Stipancic et al. Citation2016).

The most cited factor in the cycling literature was ‘Infrastructure’ (N = 23), providing the greatest number of references for this factor out of all the transport modes. There has been considerable research into bicycle infrastructure that has shown women are more likely to choose cycle routes designed with designated cycle infrastructure (Yeboah and Alvanides Citation2013; Lusk, Wen, and Zhou Citation2014) rather than main roads (Heesch, Sahlqvist, and Garrard Citation2012). This suggests one way of encouraging more female cyclists is to improve cycling infrastructure (Kunieda and Gauthier Citation2007). Bonham and Wilson (Citation2012) found that women cycled more within inner-city areas compared to the suburbs, which may be due to the enhanced cycling infrastructure within cities compared to more rural areas. Another limiting factor is the restricted baggage that cyclists can take with them (Twaddle, Hall, and Bracic Citation2010). Women have been reported to carry more personal items with them (e.g. Hwangbo et al. Citation2015), such as a change of clothes for work, which makes cycling a less attractive option (van Bekkum, Williams, and Morris Citation2011).

‘User behaviour’ produced the least number of papers that met the inclusion criteria, however, it was identified by the researchers that they may be slightly more critical of including papers due to the factor being broader. Many of the behaviours already discussed are, to some extent, user behaviour and there were some cross overs with other factors, such as work patterns, commuting, and mobility needs. A key behavioural trend evident across the transport domains was the heightened car use by men and evidence of a male cultural affinity for driving, whereas women are more likely to have a cultural affinity for walking and public transport (Kawgan-Kagan Citation2020; Ng and Acker Citation2018; Den Braver et al. Citation2020; Gill Citation2018; TFL Citation2019). There is also evidence that women tend to drive less for environmental reasons (Scheiner and Holz-Rau Citation2012). In terms of public transport behaviours, women display a tendency to take the bus for frequent, shorter trips, whereas men use the bus occasionally and generally for longer journeys (Rojo et al. Citation2011). There are also gender stereotypes prevalent at a societal level, with a ‘proper cyclist’ viewed as being predominantly male (Aldred Citation2013). Steinbach et al. (Citation2011) suggest this may be due to men being more inclined to demonstrate their physical capabilities through cycling strength. These reasons may contribute to the evidence that men tend to cycle more than women (Bonham and Wilson Citation2012).

3.2. Sub-themes

The sub-themes were identified through reviewing the literature for each factor to classify common areas in which gender may affect transport use (see section 2.1.3). The sub-themes allow a more granular level of insight into the different ways that gender influences transport use across domains. For example, when reviewing the literature on family and community roles, research articles could be differentiated by their focus on how transport is used while caring for family members, and the division of work within households that influences what travel was needed.

presents each of the sub-themes with their description and main findings from the literature in the scoping review. This table highlights key gender-related findings across all of the different transport domains, giving specific examples of how gender impacts transportation use and access.

Table 5. Gender factor sub-themes and a summary of the main finding from the scoping review.

Reviewing the gender factors and sub-themes across the different transport domains provides a rich picture of the way that gender influences travel patterns, accessibility, and safety. Bringing research together from various research domains enables a review of the systemic gender factors in transportation as well as highlighting where future research is needed. maps where our scoping review found research into the specific gender themes (grey boxes) and where no research was found (white boxes). ‘Personal safety/harassment’ was the only sub-theme that was found across all of the transport modes which highlights the importance of safety to the gendered review of transport as it is considered across multiple different modes. ‘Female body shape’ was an evident theme across all modes apart from pedestrians, highlighting how the design of transport must consider the difference in male and female bodies. ‘Behavioural trends’ and ‘infrastructure’ also only had one gap, both of which were for rail travel. Again, these themes are integral to transportation access. The cycling literature has the least number of gaps. Pedestrians and rail have the most number of gaps. The gaps identified in this scoping review suggest areas for future research that needs to consider the ways in which gender influences transport use. Comparisons across the different modes offer opportunities to learn from each other and identify concurrent issues that need to be realised and overcome. The research gaps are discussed in more detail in the Discussion section below.

Table 6. Matrix of gender-equitable transport research showing where references found evidence for the gender factor (grey box and x) and where no references were found in the search (white box).

4. Discussion

This paper presents the first gender-equitable scoping review of the current issues facing the transportation sector, as well as the gaps in understanding that need to be targeted. This scoping review has generated insights into the direct and in-direct ways that gender influences how people experience different transport modes. Identifying the high-level factors and sub-themes presents the systemic gender issues and aims to show how they need to be better understood in relation to all transport modes. Comparisons between transport modes highlight interesting areas for future research to consider on how to close the gender data gap in transportation research. The gaps we have identified in relation to the gender factors presented in this scoping review do not suggest that they are not relevant, but that future research is needed to understand their importance. These are discussed below.

4.1. Research gaps

4.1.1. Family and community roles

shows a gap in the literature on rail and bus travel for ‘Family and community roles’ and both of its sub-themes. It is suspected that there are issues relating to these factors that need to be further uncovered in these domains. For example, one consideration is the relative inflexibility of the location and times of travel in these modes which can be limiting, especially in more rural areas where trains are temporally irregular and further away. Dependability of arriving on time may also be a factor when having to collect children/dependents. Research is needed to gain a better understanding of these issues in this domain.

Research gaps were found across multiple domains for the ‘division of work’ subtheme, including aviation, bus, rail, and pedestrians. However, as it was identified that women predominantly accompany their dependents, it is expected that travel across these modes may relate also to unpaid care work and domestic duties, such as walking children to school. There could be interesting crossovers with other themes, such as safety here. For example, could safer streets enable more freedom for women as children could walk themselves to school? In the aviation domain, how do women’s domestic roles impact the experience of flying? We see overlaps with other areas, such as ‘facilities’ and ‘travelling encumbered’ being relevant here also.

4.1.2. Safety and perceived safety

There has been a significant focus on gender with respect to safety, in contrast to the other factors included in this review. There were still, however, some research gaps identified, including how ‘time of day’ may impact aviation passengers and maritime travel. There are some key questions that need to be asked as travel on these modes often requires travel to/from airports/ports at off-peak times. How do the travel patterns of women/men to and from airports/ports vary late at night or early in the morning? How can a sense of safety be maintained during these hours? Furthermore, airports are often open 24 h and require a lot of waiting around in contained areas. How does gender impact the perception of safety in these scenarios? This is likely to be highly linked to ‘fear’, which was another gap identified within the maritime mode. Other factors may also influence this, such as the environmental conditions for travel at sea, which should be researched through a gendered lens.

4.1.3. Ergonomic standards

The default male approach is heavily evident in the ergonomic design of transport safety systems which has left women at a higher risk of discomfort, injury, and death. Yet, still much more research is needed to understand exactly how male and female bodies differ and how design can be inclusive to all users. This is particularly pertinent to the domain of Human Factors, where toolsets for inclusive design should be employed. This research also needs to be considered in policy and regulation documents to promote change at the highest level. While many modes had evidence to suggest the ergonomic design of transport modes needs to fit females, there was a gap in how this applied to pedestrian travel. There may be some overlap with the evidence found for urban structures, such as the design of pavements for travelling encumbered. Yet, other factors relating to female shoe design and their ergonomic design for walking longer distances would develop the literature. Often, female footwear tends to be less practical than male footwear.

Notably, in relation to the gender data gap, the generation of female ergonomic data and its inclusion within design processes is a vital way in which gender-equitable human factors must enforce standards and best practise for inclusive design.

4.1.4. Mobility needs

While research across several domains suggests a lack of hygiene facilities for females, no research into similar trends has yet been conducted on the roads. How do service stations provide for female travellers who need more frequent access to toilet facilities and feel unsafe in empty and isolated spaces? Females are also more likely to be accompanied by dependents, as identified in the ‘family and community roles’ factor, who are also more likely to need enhanced facilities.

There were also several gaps for ‘trip characteristics’. While there is an understanding that women perform more trip chaining, how this relates specifically to cycling, rail, walking, and bus travel requires more research. Active and public travel options may restrict the accessibility to certain areas of work and/or care that making trip chaining difficult.

4.1.5. User behaviour

While research has started to look into how transport may impact well-being across genders, more research is needed in this area across all modes. Combining insights, such as evidence that women use the car more as chauffeurs, while men are more dependent on car travel for commuting, may reveal how these behaviours impact the psychological state of individuals and their employment decisions. Links can be made from other research, such as evidence that driving with young children is a common cause of driver distraction (Beanland et al. Citation2013). Could women be placing themselves at enhanced levels of stress and risk due to the chauffeuring trips they make? Do they then arrive at work more stressed? Specific gendered analysis linking these effects is missing. We need to design our transport systems to enhance the well-being of all travellers by making them safe, efficient, and resilient. This is something that is now beginning to be understood, with applications already made to children and their experience of transport (Waygood et al. Citation2020). Further research needs to review this with a gendered lens to identify how men and women interact with different transport modes.

4.1.6. Urban structures

Travelling encumbered is a key area to target with further research. Across many modes, research has failed to consider how gender may influence the type or possessions that passengers may carry and the implications this has for mode choice.

More research is also needed to review rail infrastructure with respect to gender, both within trains themselves and their provision for baggage, push chairs, and bicycles, as well as the platforms and stations. How could interactions with other modes facilitate easier encumbered travel to and from train stations? Crossovers with safety are also important here when considering how infrastructure could be designed to make women feel safer when waiting on train platforms, for example.

4.2. Recommendations for gender-equitable research methods

The research reviewed was multi-disciplinary covering journals focussing on specific transport sectors as well as Sociology, Geography, Business, Health, Manufacturing, Accident Analysis, and Engineering. The breadth of our search highlights the interdisciplinary nature of gender issues in transportation. The methodologies used vary from surveys (e.g. Cheng Citation2010; Clayton et al. Citation2014), observational studies (e.g. Schultz and Fricke Citation2011; Hwangbo et al. Citation2015), and in-depth interviews (e.g. Steinbach et al. Citation2011; Gopal and Shin Citation2019).

Typically, empirical work within the HF domain strives to incorporate the end-user within research, advocating a human-centred approach (Norman and Draper Citation1986; Karat Citation1997; Bekker and Long Citation2000). However, the evidence presented here shows that this approach can also lead to the exclusion of female participants: the fact that women have more domestic and caregiving responsibilities limits the time they have available to participate in research studies. Further, physiological methods are also limiting. Barriers to studies, such as simulator research, include enhanced motion sickness in females (Matas, Nettelbeck, and Burns Citation2015), which continues to be the case with new virtual reality technologies increasingly used in research. Stanney, Fidopiastis, and Foster (Citation2020) found this may be due to the interpupillary distance within the technology that is typically set to fit males. Difficulties in physiological data collection include eye-tracking which is less effective with those wearing eye make-up. The placement of heart-rate monitors is also more intrusive for females than males due to their placement on the chest. Due to these reasons, equal sample sizes are often neglected in favour of meeting tight research deadlines and convenience sampling (Madeira-Revell et al. Citation2021; Read et al. Citation2022). Such continuations of the ‘default male’ approach emphasise the need for women to be involved in the design process of new technologies.

Interesting new avenues for research currently underway within the authorial team include data mining and the use of social media content to review and capture gendered opinions towards transport modes in relation to travel to work. Vasquez-Henriquez, Graells-Garrido, and Caro (Citation2019) were able to capture the different ways that women and men discuss transport from a review of social media. This led them to determine the internalised safety perceptions women have towards cycling in contrast to men’s externalised views. Research methods, such as this offer much potential for understanding the societal pressures, influences, and understandings of transport and how this differs across individuals. This is critical if we are to meet the European Economic and Social Committee (Citation2015) call to include female perspectives within transportation systems.

5. Limitations and future work

This scoping review was intended to map the terrain for Gender Equitable Human Factors (GE-HF) research in the transport sector. The gender factors that we report are comprehensive but not exhaustive. There are some limitations of the review process that are important to highlight. Firstly, the review was conducted using only two search platforms. WoS was chosen due to the engineering and human factors basis of the review, however, when considering gender, more social science-based papers may be evident using platforms, such as Scopus. Further work should determine if similar findings are present across different search platforms.

It is also noted that the search criteria were limited to UK-centric terms which may have limited the search. For example, American-English alternatives, such as ‘transit’ instead of ‘bus’ and terminologies including ‘crosswalk’ and ‘sidewalk’ for pedestrians and pavements. The search was also limited by only including articles predominantly focussed on one mode of transport, greater complexities in mode choice are likely to be evident when looking at research into multiple modes.

This review has focussed solely on gender differences between men and women without looking into other intersectionality influences. It is acknowledged that these will influence some of the reported factors and statements presented in this work. For example, socio-economic status is also a key factor that impacts transport equity (Gates et al. Citation2019), including where people live, what opportunities are available, and how these opportunities can be accessed. For example, people from lower socio-economic backgrounds are more likely to take the bus and are also more likely to reject job opportunities due to transport barriers (DfT Citation2017; Gates et al. Citation2019). Travel patterns also vary with age across genders, with women of a reproductive age making many more journeys than women over the age of 50, whereas male travel patterns are more resistant to changes (Sánchez and González Citation2016). Different cultures also have different views on the roles of females and the roles that they can fulfill, particularly in relation to employment (Seligson Citation2019; Kuruppu and Hettiarachchi Citation2019). Future work should build on this matrix to include intersectionality factors and review how they intersect the themes presented in this paper.

The transport industry is currently at a pivotal moment with pressure from environmental issues and rapid developments in automated technologies. At the same time, the industries essential role in travel to work is recognised as a major contributor to social equalities. Research into the implementation of automated and electric vehicles must consider who those vehicles are predominantly targeted at and the types of journeys that they will be used for. Men, who rely more heavily on private vehicles, are set to benefit more than women. Opportunities for charging electric vehicles may be more limited when trip-chaining, is routinely conducted by women. Alternatively, investment in a modal shift away from private vehicles to enhance the accessibility of alternative modes will aid women as well as provide more sustainable modes of transport (Scheiner and Holz-Rau Citation2012).

6. Conclusion: the importance of gender-equitable human factors and ergonomics

The first verse of the song ‘It’s a man’s, man’s, man’s world’ (Brown and Newsome Citation1966) describes the historic state of transport, which no longer fits the needs of society today.

“You see, man made the cars to take us over the road

Man made the train to carry the heavy load

Man made electric light to take us out of the dark

Man made the boat for the water, like Noah made the ark”

This paper argues that an interdisciplinary approach to HF, routinely applying a gender-equitable lens, could ensure all forms of public transport meet the varying mobility needs of both the labour market and family and community roles. A Gender-Equitable HF can, for example, make cars as ergonomically crash-proof for women as for men. It can ensure trains, platforms, and stations are designed to encourage high perceptions of safety for all. Considering where and how electric lighting is used would encourage safer active travel, such as walking, running, and cycling, and reduce differences in confidence and perceptions that affect user behaviour. GE-HF could also aspire to create a transport sector with cultures where women are not only attracted to work, but retained to become leaders and decision-makers. Our review has focussed on transport to reveal the essential role that travel plays within debates on gender and work.

In sum, our argument is that if we keep creating and using research focussed on a man’s world, it will do nothing to build an equitable future. As our review demonstrably evidences now is the time for a change.

| Abbreviations | ||

| DfT | = | Department for Transport |

| EU | = | European Union |

| ECE | = | European Commission for Europe |

| HF | = | human factors |

| GE | = | HE: gender equitable human factors |

| GS | = | google scholar |

| WoS | = | web of science |

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the ‘Close the Data Gap’ group at the University of Southampton for their insights and support with this publication (https://closethedatagap.soton.ac.uk).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ackerley, B., and J. True. 2019. Doing Feminist Research in Political and Social Science. Red Globe Press.

- Aldred, R. 2013. “Incompetent or Too Competent? Negotiating Everyday Cycling Identities in a Motor Dominated Society.” Mobilities 8 (2): 252–271. doi:10.1080/17450101.2012.696342.

- Arksey, Hilary, and Lisa O’Malley. 2005. “Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology: Theory and Practice 8 (1): 19–32. doi:10.1080/1364557032000119616.

- ARUP and Sustrans. 2019. Inclusive cycling in cities and towns. Accessed 24 September 2021. https://www.arup.com/perspectives/publications/promotional-materials/section/inclusive-cycling-in-cities-and-towns

- Beanland, V., M. Fitzharris, K. L. Young, and M. G. Lenné. 2013. “Driver Inattention and Driver Distraction in Serious Casualty Crashes: Data from the Australian National Crash in-Depth Study.” Accident; Analysis and Prevention 54: 99–107. doi:10.1016/j.aap.2012.12.043.

- Beebeejaun, Y. 2017. “Gender, Urban Space, and the Right to Everyday Life.” Journal of Urban Affairs 39 (3): 323–334.

- Bekker, M., and J. Long. 2000. “User Involvement in the Design of Human–Computer Interactions: some Similarities and Differences between Design Approaches.” In People and Computers XIV (Proceedings of HCI’2000), edited by S. McDonald, Y. Waern, and G. Cockton, 135–147. Springer.

- Boarnet, M. G., and H. P. Hsu. 2015. “The Gender Gap in Non-Work Travel: The Relative Roles of Income Earning Potential and Land Use.” Journal of Urban Economics 86: 111–127. doi:10.1016/j.jue.2015.01.005.

- Boksberger, P. E., T. Bieger, and C. Laesser. 2007. “Multidimensional Analysis of Perceived Risk in Commercial Air Travel.” Journal of Air Transport Management 13 (2): 90–96. doi:10.1016/j.jairtraman.2006.10.003.

- Bonham, J., and A. Wilson. 2012. “Bicycling and the Life Course: The Start-Stop-Start Experiences of Women Cycling.” International Journal of Sustainable Transportation 6 (4): 195–213. doi:10.1080/15568318.2011.585219.

- Bose, D., M. Segui-Gomez, and J. R. Crandall. 2011. “Vulnerability of Female Drivers Involved in Motor Vehicle Crashes: An Analysis of US Population at Risk.” American Journal of Public Health 101 (12): 2368–2373. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2011.300275.

- Boterman, W. R. 2020. “Carrying Class and Gender: Cargo Bikes as Symbolic Markers of Egalitarian Gender Roles of Urban Middle Classes in Dutch Inner Cities.” Social & Cultural Geography 21 (2): 245–264. doi:10.1080/14649365.2018.1489975.

- Brown, J., and B. J. Newsome. 1966. It’s a Man’s Man’s Man’s World. Accessed 24 September 2021. https://genius.com/James-brown-its-a-mans-world-lyrics

- Ceccato, V., and Y. Paz. 2017. “Crime in Sao Paolo’s Metro System: Sexual Crimes against Women.” Crime Prevention and Community Safety 19 (3–4): 211–226. doi:10.1057/s41300-017-0027-2.

- Chebli, H., and H. S. Mahmassani. 2003. “Air Travellers’ Stated Preferences towards New Airport Landside Access Mode Services.” Annual Meeting of Transportation Research Board.

- Cheng, Y. H. 2010. “Exploring Passenger Anxiety Associated with Train Travel.” Transportation 37 (6): 875–896. doi:10.1007/s11116-010-9267-z.

- Cho, S., P. Gordon, J. E. Moore II, H. W. Richardson, M. Shinozuka, and S. Chang. 2001. “Integrating Transportation Network and Regional Economic Models to Estimate the Costs of a Large Urban Earthquake.” Journal of Regional Science 41 (1): 39–65. doi:10.1111/0022-4146.00206.

- Choo, S., S. You, and H. Lee. 2013. “Exploring Characteristics of Airport Access Mode Choice: A Case Study of Korea.” Transportation Planning and Technology 36 (4): 335–351. doi:10.1080/03081060.2013.798484.

- Clayton, W., E. Ben-Elia, G. Parkhurst, and M. Ricci. 2014. “Where to Park? A Behavioural Comparison of Bus Park and Ride and City Centre Car Park Usage in Bath, UK.” Journal of Transport Geography 36: 124–133. doi:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2014.03.011.

- Clemes, M. D., T. Kao, and M. Choong. 2008. “An Empirical Analysis of Customer Satisfaction in International Air Travel.” Innovative Marketing 4 (2): 49–62.

- Criado-Perez, C. 2019. Invisible Women: Exposing Data Bias in a World Designed for Men. Penguin Random House.

- Cui, M., T. Wang, Z. Pan, and L. Ni. 2020. “Definition of People with Impediments and Universality Evaluation of Public Service in Airport Travel Scenarios.” In Design, User Experience, and Usability. Design for Contemporary Interactive Environments, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, edited by A. Marcus and E. Rosenzweig, 623–639. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Dargay, J. M., and S. Clark. 2012. “The Determinants of Long Distance Travel in Great Britain.” Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 46 (3): 576–587. doi:10.1016/j.tra.2011.11.016.

- Den Braver, N. R., J. G. Kok, J. D. Mackenbach, H. Rutter, J. M. Oppert, S. Compernolle, J. W. R. Twisk, J. Brug, J. W. J. Beulens, and J. Lakerveld. 2020. “Neighbourhood Drivability: Environmental and Individual Characteristics Associated with Car Use across.” International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 17 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1186/s12966-019-0906-2.

- Department for Transport. 2017. National Travel Survey: 2017. Accessed 21 January 2022. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/national-travel-survey-2017

- Department for Transport. 2020a. DfT: gender pay gap report and data 2020. Accessed 28 September 2021. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/dft-gender-pay-gap-report-and-data-2020/dft-gender-pay-gap-report-and-data-2020

- Department for Transport. 2020b. National Travel Attitudes Study: Wave 3. Accessed 6 July 2021: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/national-travel-attitudes-study-wave-3

- Dobbs, L. 2007. Stuck in the Slow Lane: Reconceptualizing the Links between Gender, Transport and Employment – Dobbs – 2007 – Gender, Work & Organization – Wiley Online Library. Accessed 5 January 2021. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0432.2007.00334.x

- Esat, V., and B. S. Acar. 2012. “Effects of Table Design in Railway Carriages on Pregnant Occupant Safety.” International Journal of Crashworthiness 17 (3): 337–343. doi:10.1080/13588265.2012.664009.

- European Commission. 2017. Women employed in the transport sector. Accessed 27 September 2021. https://ec.europa.eu/transport/facts-fundings/scoreboard/compare/people/women-public-transport_en#2017

- European Economic and Social Committee. 2015. Opinion of the European Economic and Social Committee on ‘Women and Transport’ (2015/C 383/01). Accessed 29 September 2021. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52015AE1773&from=SL

- Evans, I., J. Pansch, L. Singer-Berk, and G. Lindsey. 2018. “Factors Affecting Vehicle Passing Distance and Encroachments While Overtaking Cyclists.” Institute of Transportation Engineers Journal 88 (5): 40–45. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/factors-affecting-vehicle-passing-distance/docview/2038608337/se-2?accountid=13963.

- Federal Bureau of Investigation. 2018. “Sexual Assault aboard Aircraft: Raising Awareness about a Serious Federal Crime.” FBI News. https://www.fbi.gov/news/stories/raising-awareness-about-sexual-assault-aboard-aircraft-042618.

- Flynn, D. 2015. Finnair's Airbus A350 has free Internet, ladies-only toilet. Executive Traveller. https://www.executivetraveller.com/finnair-s-airbus-a350-has-free-internet-ladies-only-toilets

- Frändberg, L., and B. Vilhelmson. 2003. “Personal Mobility: A Corporeal Dimension of Transnationalisation. The Case of Long-Distance Travel from Sweden.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 35 (10): 1751–1768. doi:10.1068/a35315.

- Fundamental Rights Agency. 2014. Violence against women: an EU-wide survey. Accessed 29 September 2021. https://fra.europa.eu/sites/default/files/fra-2014-vaw-survey-at-a-glance-oct14_en.pdf

- Gahlinger, P. M. 2000. “Cabin Location and the Likelihood of Motion Sickness in Cruise Ship Passengers.” Journal of Travel Medicine 7 (3): 120–124. doi:10.2310/7060.2000.00042.

- Gates, S., F. Gogescu, C. Grollman, E. Cooper, and P. Khambhaita. 2019. Transport and Inequality: An Evidence Review for the Department for Transport. London: NatCen Social Research. Accessed 21 January 2022. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/953951/Transport_and_inequality_report_document.pdf

- Gill, R. 2018. Public Transport and Gender (Issue October). https://wbg.org.uk/analysis/2018-wbg-briefing-transport-and-gender/

- Gkritza, K., D. Niemeier, and F. Mannering. 2006. “Airport Security Screening and Changing Passenger Satisfaction: An Exploratory Assessment.” Journal of Air Transport Management 12 (5): 213–219. doi:10.1016/j.jairtraman.2006.03.001.

- Gopal, K., and E. J. Shin. 2019. “The Impacts of Rail Transit on the Lives and Travel Experiences of Women in the Developing World: Evidence from the Delhi Metro.” Cities 88: 66–75. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2019.01.008.

- Gray, J. 2020. Sexual assaults on airplanes on the rise, FBI warns. WSBTV. https://www.wsbtv.com/news/2-investigates/sexual-assaults-airplane-rise-fbi-warns/HZRVB762XVGONC53ZFNSUCJXQA/

- Greghi, M. F., T. N. Rossi, J. B. G. de Souza, and N. L. Menegon. 2013. “Brazilian Passengers' Perceptions of Air Travel: Evidences from a Survey.” Journal of Air Transport Management 31: 27–31. doi:10.1016/j.jairtraman.2012.11.008.

- Gupta, S., P. Vovsha, and R. Donnelly. 2008. “Air Passenger Preferences for Choice of Airport and Ground Access Mode in the New York City Metropolitan Region.” Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board 2042 (1): 3–11. doi:10.3141/2042-01.

- Gustafson, P. 2006. “Work-Related Travel, Gender and Family Obligations.” Work, Employment and Society 20 (3): 513–530. doi:10.1177/0950017006066999.

- Ham, H., T. J. Kim, and D. Boyce. 2005. “Assessment of Economic Impacts from Unexpected Events with an Interregional Commodity Flow and Multimodal Transportation Network Model.” Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 39 (10): 849–860.

- Hamilton, K., and L. Jenkins. 2000. “A Gender Audit for Public Transport: A New Policy Tool in the Tackling of Social Exclusion.” Urban Studies 37 (10): 1793–1800. doi:10.1080/00420980020080411.

- Harrison, C. R, and K. M. Robinette. 2002. CAESAR: Summary Statistics for the Adult Aopulation (Ages 18–65) of United States of America. SAE International. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA406674.pdf

- Haynes, E., J. Green, R. Garside, M. P. Kelly, and C. Guell. 2019. “Gender and Active Travel: A Qualitative Data Synthesis Informed by Machine Learning.” International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 16 (1): 135. doi:10.1186/s12966-019-0904-4.

- Heesch, K. C., S. Sahlqvist, and J. Garrard. 2012. “Gender Differences in Recreational and Transport Cycling: A Cross-Sectional Mixed-Methods Comparison of Cycling Patterns, Motivators, and Constraints.” International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 9 (1): 106–112. doi:10.1186/1479-5868-9-106.

- Holmes, M. 2008. Gender and Everyday Life. 1st ed. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203929384.

- Hwangbo, H., J. Kim, S. Kim, and Y. G. Ji. 2015. “Toward Universal Design in Public Transportation Systems: An Analysis of Low-Floor Bus Passenger Behavior with Video Observations.” Human Factors and Ergonomics in Manufacturing & Service Industries 25 (2): 183–197. doi:10.1002/hfm.20537.

- Karastergiou, K., S. R. Smith, A. S. Greenberg, and S. K. Fried. 2012. “Sex Differences in Human Adipose Tissues-the Biology of Pear Shape.” Biology of Sex Differences 3 (1): 1–12.

- Karat, J. 1997. “Evolving the Scope of User-Centered Design.” Communications of the ACM 40 (7): 33–38. doi:10.1145/256175.256181.

- Kawgan-Kagan, I. 2020. “Are Women Greener than Men? A Preference Analysis of Women and Men from Major German Cities over Sustainable Urban Mobility.” Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives 8: 100236. doi:10.1016/j.trip.2020.100236.

- Kronsell, A., C. Dymén, L.S. Rosqvist, and L.W. Hiselius. 2020. “Masculinities and Femininities in Sustainable Transport Policy: A Focus on Swedish Municipalities.” NORMA 15 (2): 128–144. doi:10.1080/18902138.2020.1714315.

- Kullgren, A., H. Stigson, and M. Krafft. 2013. “Development of Whiplash Associated Disorders for Male and Female Car Occupants in Cars Launched since the 80s in Different Impact Directions.” Proceedings of the IRCOBI Conference.

- Kunieda, M, and A. Gauthier. 2007. Sustainable Transport: A Source Book for Policy Makers in Developing Cities. Module 7a: Gender and Urban Transport. Eschborn: Fashionable and Affordable, GTZ.

- Kuruppu, K. A. D. D., and C. J. Hettiarachchi. 2019. “Study on Women's Perspective towards Aviation Careers in Sri Lanka.” GARI International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research 5 (5): 26–35.

- Kuttler, T, and M. Moraglio. 2020. Re-thinking Mobility Poverty Understanding Users’ Geographies, Backgrounds and Aptitudes. Accessed 20 January 2021. http://www.vlebooks.com/vleweb/product/openreader?id=none&isbn=9781000289466

- Levy, C. 2013. “Travel Choice Reframed: “Deep Distribution” and Gender in Urban Transport.” Environment and Urbanization 25 (1): 47–63. doi:10.1177/0956247813477810.

- Linder, A., and W. Svedberg. 2019. “Review of Average Sized Male and Female Occupant Models in European Regulatory Safety Assessment Tests and European Laws: Gaps and Bridging Suggestions.” Accident; Analysis and Prevention 127: 156–162. doi:10.1016/j.aap.2019.02.030.

- Loukaitou-Sideris, A. 2014. “Fear and Safety in Transit Environments from the Women’s Perspective.” Security Journal 27 (2): 242–256. doi:10.1057/sj.2014.9.

- Lucas, K. T. 2021. “In-Flight Sexual Victimization in the #METOO Era: A Content Analysis of Media Reports.” American Journal of Criminal Justice 46 (1): 130–148. doi:10.1007/s12103-020-09587-5.

- Lusk, A.C., X. Wen, and L. Zhou. 2014. “Gender and Used/Preferred Differences of Bicycle Routes, Parking, Intersection Signals, and Bicycle Type: Professional Middle Class Preferences in Hangzhou, China.” Journal of Transport & Health 1 (2): 124–133. doi:10.1016/j.jth.2014.04.001.

- Maciejewska, M., O. Marquet, and C. Miralles-Guasch. 2019. “Changes in Gendered Mobility Patterns in the Context of the Great Recession (2007–2012).” Journal of Transport Geography 79: 102478. doi:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2019.102478.

- Madan, M., and M. Nalla. 2016. “Sexual Harassment in Public Spaces: Examining Gender Differences in Perceived Seriousness and Victimization.” International Criminal Justice Review 26 (2): 80–97. doi:10.1177/1057567716639093.

- Madeira-Revell, K. M., K. J. Parnell, J. Richardson, K. A. Pope, D. T. Fay, S. E. Merriman, and K. L. Plant. 2021. “How Can we Close the Gender Data Gap in Transportation Research?” Ergonomics SA: Journal of the Ergonomics Society of South Africa 32 (1): 19–26.

- Marçal, K. 2021. Mother of Invention: How Good Ideas Get Ignored in an Economy Built for Men. William Collins.

- Martinussen, M., E. Gundersen, and R. Pedersen. 2011. “Predicting Fear of Flying and Positive Emotions towards Air Travel.” Aviation Psychology and Applied Human Factors 1 (2): 70–74. doi:10.1027/2192-0923/a000011.

- Matas, N. A., T. Nettelbeck, and N. R. Burns. 2015. “Dropout during a Driving Simulator Study: A Survival Analysis.” Journal of Safety Research 55: 159–169. doi:10.1016/j.jsr.2015.08.004.

- Miller, E. L., S. M. Lapp, and M. B. Parkinson. 2019. “The Effects of Seat Width, Load Factor, and Passenger Demographics on Airline Passenger Accommodation.” Ergonomics 62 (2): 330–341. doi:10.1080/00140139.2018.1550209.

- Moher, D., A. Liberati, J. Tetzlaff, and D. G. Altman. 2009. “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses: the PRISMA Statement.” Annals of Internal Medicine 151 (4): 264–269.

- Naess, P. 2008. “Gender Differences in the Influences of Urban Structure on Daily Travel.” In Gendered Mobilities, edited by T. P. Uteng and T. Cresswell, 173–193. Aldreshot, UK: Ashgate Publishing Limited.

- Ng, W. S., and A. Acker. 2018. Understanding Urban Travel Behaviour by Gender for Efficient and Equitable Transport Policies. OECD International Transport Forum. https://www.itf-oecd.org/understanding-urban-travel-behaviour-gender-efficient-and-equitable-transport-policies%0Ahttps://trid.trb.org/view/1505620FGF

- Nieuwenhoven, L., and I. Klinge. 2010. “Scientific Excellence in Applying Sex-and Gender-Sensitive Methods in Biomedical and Health Research.” Journal of Women's Health 19 (2): 313–321. doi:10.1089/jwh.2008.1156.

- Norman, D. A., and S. W. Draper. 1986. User Centered System Engineering. Erlbaum.

- Nowatzki, N., and K. R. Grant. 2011. “Sex is Not Enough: The Need for Gender-Based Analysis in Health Research.” Health Care for Women International 32 (4): 263–277. doi:10.1080/07399332.2010.519838.

- Oyewole, P. 2001. “Consumer’s Socio-Demographic Characteristics and Satisfaction with Services in the Airline Industry.” Services Marketing Quarterly 23 (2): 61–80. doi:10.1300/J396v23n02_04.

- Park, H., and B. Almanza. 2020. “What Do Airplane Travelers Think about the Cleanliness of Airplanes and How Do They Try to Prevent Themselves from Getting Sick?” Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism 21 (6): 738–757. doi:10.1080/1528008X.2020.1746222.

- Park, A. H., and S. Hu. 1999. “Gender Differences in Motion Sickness History and Susceptibility to Optokinetic Rotation-Induced Motion Sickness.” Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine 70 (11): 1077–1080.

- Peake, L. 2019. “Gender and the City (2020).” In International Encyclopedia of Human Geography, 2nd ed., edited by A. Kobayashi, 281–292. Elsevier.

- Pham, M. T., A. Rajić, J. D. Greig, J. M. Sargeant, A. Papadopoulos, and S. A. McEwen. 2014. “A Scoping Review of Scoping Reviews: Advancing the Approach and Enhancing the Consistency.” Research Synthesis Methods 5 (4): 371–385. doi:10.1002/jrsm.1123.

- Plyushteva, A., and T. Schwanen. 2018. “Care-Related Journeys over the Life Course: Thinking Mobility Biographies with Gender, Care and the Household.” Geoforum 97: 131–141. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.10.025.

- Pooley, C. 2016. “Mobility, Transport and Social Inclusion: Lessons from History.” Social Inclusion 4 (3): 100–109. doi:10.17645/si.v4i3.461.

- Potter, J. J., J. L. Sauer, C. L. Weisshaar, D. G. Thelen, and H. L. Ploeg. 2008. “Gender Differences in Bicycle Saddle Pressure Distribution during Seated Cycling.” Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 40 (6): 1126–1134. doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181666eea.

- Read, G. J. M., K. Madeira-Revell, K. J. Parnell, D. Lockton, and P. Salmon. 2022. “Using Human Factors and Ergonomics Methods to Challenge the Status Quo: Designing for Gender Equitable Research Outcomes.” Applied Ergonomics 99: 103634. doi:10.1016/j.apergo.2021.103634.

- Robinson, B., S. E. Vasko, C. Gonnerman, M. Christen, M. O’Rourke, and D. Steel. 2016. “Human Values and the Value of Humanities in Interdisciplinary Research.” Cogent Arts & Humanities 3 (1): 1123080. doi:10.1080/23311983.2015.1123080.

- Rojo, Marta, Hernan Gonzalo-Orden, Luigi. dell'Olio, and Angel. Ibeas. 2011. “Modelling Gender Perception of Quality in Interurban Bus Services.” Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers-Transport 164 (1): 43–53. doi:10.1680/tran.9.00031.

- Rose, J. M., D. A. Hensher, W. H. Greene, and S. P. Washington. 2012. “Attribute Exclusion Strategies in Airline Choice: Accounting for Exogenous Information on Decision Maker Processing Strategies in Models of Discrete Choice.” Transportmetrica 8 (5): 344–360. doi:10.1080/18128602.2010.506897.

- Ross, W. 2000. “Mobility Abd Accessibility: The Yin and Yang of Planning.” World Transport Policy and Practice 6 (2): 13–19.

- Salvendy, G. 2012. Handbook of Human Factors and Ergonomics. John Wiley & Sons.

- Sanchez de Madariaga, I. S. 2013. “From Women in Transport to Gender in Transport: challenging Conceptual Frameworks for Improved Policymaking.” Journal of International Affairs 43–65.

- Sánchez, M. I. O., and E. M. González. 2016. “Gender Differences in Commuting Behavior: Women's Greater Sensitivity.” Transportation Research Procedia 18: 66–72. doi:10.1016/j.trpro.2016.12.009.

- Sarshar, P., J. Radianti, O. C. Granmo, and J. J. Gonzalez. 2013. “A Dynamic Bayesian Network Model for Predicting Congestion during a Ship Fire Evacuation.” Lecture Notes in Engineering and Computer Science 1: 29–34.

- Scheiner, J., and C. Holz-Rau. 2012. “Gender Structures in Car Availability in Car Deficient Households.” Research in Transportation Economics 34 (1): 16–26. doi:10.1016/j.retrec.2011.12.006.

- Scheiner, J., and C. Holz-Rau. 2017. “Women’s Complex Daily Lives: A Gendered Look at Trip Chaining and Activity Pattern Entropy in Germany.” Transportation 44 (1): 117–138. doi:10.1007/s11116-015-9627-9.

- Schmucki, B. 2012. “If I Walked on my Own at Night I Stuck to Well Lit Areas. Gendered Spaces and Urban Transport in 20th Century Britain.” Research in Transportation Economics 34 (1): 74–85. doi:10.1016/j.retrec.2011.12.002.

- Schorr, M., L.E. Dichtel, A.V. Gerweck, R.D. Valera, M. Torriani, K.K. Miller, and M.A. Bredella. 2018. “Sex Differences in Body Composition and Association with Cardiometabolic Risk.” Biology of Sex Differences 9 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1186/s13293-018-0189-3.

- Schultz, M., and H. Fricke. 2011. “Managing Passenger Handling at Airport Terminals.” In 9th USA/Europe Air Traffic Management Research and Development Seminars, 438–477.

- Seligson, D. 2019. Women and Aviation: Quality Jobs, Attraction and Retention. International Labour Organization Working Paper No. 331. https://www.academia.edu/download/63524331/Women_and_aviation_Quality_jobs__attraction_and_retention20200604-24982-g20b0b.pdf

- Simmons, M. 2019. “Infant Mortality and Issue Framing in South Linden.” Doctoral Diss., Ohio State University. Knowledge Bank. Accessed 11 February 2021. https://kb.osu.edu/handle/1811/87671

- Srinivasan, S. 2008. “A Spatial Exploration of the Accessibility of Low-Income Women: Chengdu, China and Chennai, India.” In Gendered Mobilities, edited by T. Cresswell and T. P. Uteng, 143–158. Ashgate Publishing.

- Stanney, K., C. Fidopiastis, and L. Foster. 2020. “Virtual Reality is Sexist: But It Does Not Have to Be.” Frontiers in Robotics and AI 7: 4. doi:10.3389/frobt.2020.00004.

- Stark, J., and M. Meschik. 2018. “Women’s Everyday Mobility: Frightening Situations and Their Impacts on Travel Behaviour.” Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour 54: 311–323. doi:10.1016/j.trf.2018.02.017.

- Steinbach, R., J. Green, J. Datta, and P. Edwards. 2011. “Cycling and the City: A Case Study of How Gendered, Ethnic and Class Identities Can Shape Healthy Transport Choices.” Social Science & Medicine 72 (7): 1123–1130. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.01.033.

- Stipancic, J., S. Zangenehpour, L. Miranda-Moreno, N. Saunier, and M. A. Granié. 2016. “Investigating the Gender Differences on Bicycle-Vehicle Conflicts at Urban Intersections Using an Ordered Logit Methodology.” Accident Analysis & Prevention 97: 19–27. doi:10.1016/j.aap.2016.07.033.

- Tahanisaz, S., and S. Shokuhyar. 2020. “Evaluation of Passenger Satisfaction with Service Quality: A Consecutive Method Applied to the Airline Industry.” Journal of Air Transport Management 83: 101764. doi:10.1016/j.jairtraman.2020.101764.

- Transport for London. 2019. Travel in London: Understanding our diverse communities 2019. Accessed 29 February 2021. http://content.tfl.gov.uk/travel-in-london-understanding-our-diverse-communities-2019.pdf

- Thom, M. L., K. Willmore, A. Surugiu, E. Lalone, and T. A. Burkhart. 2020. “Females Are Not Proportionally Smaller Males: Relationships between Radius Anthropometrics and Their Sex Differences.” HAND 15 (6): 850–857. doi:10.1177/1558944719831239.

- Tran, H. A., and A. Schlyter. 2010. “Gender and Class in Urban Transport: The Cases of Xian and Hanoi.” Environment and Urbanization 22 (1): 139–155.

- Tsafarakis, S., T. Kokotas, and A. Pantouvakis. 2018. “A Multiple Criteria Approach for Airline Passenger Satisfaction Measurement and Service Quality Improvement.” Journal of Air Transport Management 68: 61–75. doi:10.1016/j.jairtraman.2017.09.010.

- Turner, M., and M. J. Griffin. 1999. “Motion Sickness in Public Road Transport: The Effect of Driver, Route and Vehicle.” Ergonomics 42 (12): 1646–1664. doi:10.1080/001401399184730.

- Turner, M., M. J. Griffin, and I. Holland. 2000. “Airsickness and Aircraft Motion during Short-Haul Flights.” Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine 71 (12): 1181–1189.

- Twaddle, H., F. Hall, and B. Bracic. 2010. “Latent Bicycle Commuting Demand and Effects of Gender on Commuter Cycling and Accident Rates.” Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board 2190 (1): 28–36. doi:10.3141/2190-04.

- Tyers, R., and P. Leonard. 2020. “Making Smart Fair: Building Inclusive, Fair and Sustainable Transport for Cities of the Future.” WSI White Papers 3. doi:10.5258/SOTON/WSI-WP003.

- van Bekkum, J. E., J. M. Williams, and P. G. Morris. 2011. “Cycle Commuting and Perceptions of Barriers: Stages of Change, Gender and Occupation.” Health Education 111 (6): 476–497. doi:10.1108/09654281111180472.

- Tilburg, Miriam, Theo Lieven, Andreas Herrmann, and Claudia Townsend. 2015. “Beyond “Pink It and Shrink It” Perceived Product Gender, Aesthetics, and Product Evaluation.” Psychology & Marketing 32 (4): 422–437. doi:10.1002/mar.20789.

- Vance, C., S. Buchheim, and E. Brockfeld. 2005. “Gender as a Determinant of Car Use: Evidence from Germany.” In Research on Women’s Issues in Transportation. Technical Papers. Transportation Research Board Conference Proceedings, Vol. 35, edited by Transportation Research Board, 59–67. National Research Council.

- Vanier, C., and H. D. A. De Jubainville. 2017. “Feeling Unsafe in Public Transportation: A Profile Analysis of Female Users in the Parisian Region.” Crime Prevention and Community Safety 19 (3–4): 251–263. doi:10.1057/s41300-017-0030-7.

- Vasquez-Henriquez, P., E. Graells-Garrido, and D. Caro. 2019. “Characterizing Transport Perception Using Social Media: Differences in Mode and Gender.” In Proceedings of the 10th ACM Conference on Web Science, 295–299.

- Venter, C., V. Vokolkova, and J. Michalek. 2007. “Gender, Residential Location, and Household Travel: Empirical Findings from Low‐Income Urban Settlements in Durban.” South Africa, Transport Reviews 27 (6): 653–677. doi:10.1080/01441640701450627.

- Wang, J., Z.-R. Xiang, J.-Y. Zhi, J.-P. Chen, S.-J. He, and Y. Du. 2021. “Assessment Method for Civil Aircraft Cabin Comfort: Contributing Factors, Dissatisfaction Indicators, and Degrees of Influence.” International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics 81: 103045. doi:10.1016/j.ergon.2020.103045.

- Waygood, O., M. Friman, L. Olsson, and R. Mitra, eds. 2020. Transport and Children’s Wellbeing. Elsevier.

- Weber, K. 2005. “Travelers’ Perceptions of Airline Alliance Benefits and Performance.” Journal of Travel Research 43 (3): 257–265. doi:10.1177/0047287504272029.

- Westwood, S., A. Pritchard, and N. J. Morgan. 2000. “Gender-Blind Marketing: Businesswomen's Perceptions of Airline Services.” Tourism Management 21 (4): 353–362. doi:10.1016/S0261-5177(99)00069-2.

- Winslott Hiselius, L., A. Kronsell, C. Dymén, and L. Smidfelt Rosqvist. 2019. “Investigating the Link between Transport Sustainability and the Representation of Women in Swedish Local Committees.” Sustainability 11 (17): 4728.

- Yeboah, G., and S. Alvanides. 2013. Everyday cycling in urban environments: Understanding behaviours and constraints in space-time.

- Yellow Window. 2018. Gender and the Transport Research field. Accessed 29 September 2021. https://cca91782-7eea-4c09-8bff-0426867031ff.filesusr.com/ugd/17c073_61fd21c4621c478b9e901eb86bb5aa38.pdf