Abstract

As families increase their use of mobile touch screen devices (smartphones and tablet computers), there is potential for this use to influence parent-child interactions required to form a secure attachment during infancy, and thus future child developmental outcomes. Thirty families of infants (aged 9–15 months) were interviewed to explore how parents and infants use these devices, and how device use influenced parents’ thoughts, feelings and behaviours towards their infant and other family interactions. Two-thirds of infants were routinely involved in family video calls and one-third used devices for other purposes. Parent and/or child device use served to both enhance connection and increase distraction between parents and infants and between other family members. Mechanisms for these influences are discussed. The findings highlight a new opportunity for how hardware and software should be designed and used to maximise benefits and reduce detriments of device use to optimise parent-infant attachment and child development.

Practitioner Summary: Many families with infants regularly use smartphones and tablet computers. This qualitative study found that how devices were used either enhanced or disrupted feelings of parent-infant attachment. Practitioners should be aware of the potential beneficial and detrimental impacts of device use among families given implications for attachment and future child development.

1. Introduction

Over the past few decades, human-computer interaction has been found to have considerable effects on humans including their performance, communication and health (Gurcan et al. Citation2021). As newer technologies have emerged, such as mobile touch screen devices, research has also evolved to explore the implications of their use. Much of this evidence has centred on human-computer interaction among adults (Coenen et al. Citation2019; Han et al. Citation2019); however some research has explored child use and outcomes (Harris and Straker Citation2000; Straker et al. Citation2014) and even human-computer interactions prior to birth (Hood et al. Citation2022; Fleming et al. Citation2014).

Many families now regularly use newer digital technologies such as smartphones and tablet computers with ownership of these devices increasing dramatically in recent years. For example in 2021, 85% of U.S. adults reported owning a smartphone and 53% a tablet computer (up from 35% and 8% respectively in 2011) (Pew Research Centre Citation2021). A recent field study of Australian adults found the average duration of touch screen device use to be 2.5 h/d, with participants engaging with their device on average 52 times a day (Alzhrani et al. Citation2022). Among young children, one-third (36%) of Australian pre-schoolers have been reported to own their own tablet or smartphone (Rhodes Citation2017). A study of Irish children aged 12 months to 3 years found that 71% had access to touch screen devices, with a median usage time of 15 min/d (Ahearne et al. Citation2016).

With the rapid uptake in mobile touchscreen technology among adults and children, it is important to consider human-computer interactions within families to both understand their consequences on behaviour and development – particularly for growing children – and to ensure they are used in a positive manner. Family system theory (White and Klein Citation2008) and the bioecological model (Bronfenbrenner and Morris Citation2006) provide a framework for exploring human-computer interactions in a family setting, where the whole family unit is considered, along with their mutual influence on each other’s behaviours and experiences.

Within the family system is the parent-child dyad. The theory of parent-child attachment proposes that infants develop an emotional bond with their primary caregiver during their first years of life (Bowlby Citation1980). In the presence of a secure attachment relationship, the parent is sensitive and responsive to their child’s needs and signals for attention, and the child is able to use the caregiver as a secure base from which to explore their environment (Ainsworth et al. Citation1978; Rees Citation2005).

The establishment of a secure attachment between the parent and child in infancy is critical with evidence to suggest that it is predictive of aspects of child development such as cognitive performance (West et al. Citation2013; Schore Citation2001), emotion regulation (Zimmer-Gembeck et al. Citation2017; Brumariu Citation2015), social competence with peers (Groh et al. Citation2014; Bohlin et al. Citation2000) and duration of sleep (Cheung et al. Citation2017; Bordeleau et al. Citation2012). The use of mobile touch screen devices requires investments of both time and attention by the user. There is a potential for the interactions between a parent and infant that are necessary for the formation of a secure attachment to be influenced by the use of mobile touch screen devices (Beamish et al. Citation2019). Parents and professionals alike express concern and seek guidance about potential developmental impacts from the use of mobile touch screen devices and evidence informing these concerns remains scant but would be useful in guiding advice.

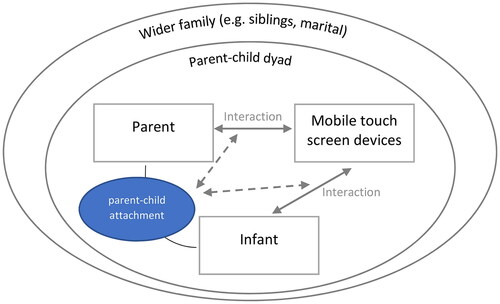

Previous models of human-computer interaction provide a framework for considering the influences of device use within the family system (Straker and Pollock Citation2005; Straker et al. Citation2014). depicts a new proposed integrated model of human-computer interaction within a family context, with solid line arrows showing the interaction and flow of information. The double-headed arrows between the parent or infant and the mobile touch screen device represent the parent/infant sending information to the device (e.g. launching an App) and the device sending information to the parent/infant (e.g. music playing through the device’s speakers). The dashed line arrows depict the potential influence of parent-device or infant-device interaction on parent-infant attachment.

Figure 1. Model of the potential influence of mobile touch screen device use on parent-child attachment in an integrated family system.

The proposed model expands on the theories of parent-child attachment, family systems and the bioecological model by exemplifying possible mechanisms by which parent and/or child use of mobile touch screen devices may influence parent-child interactions and attachment.

Possible mechanisms for device use to have a positive influence on attachment are by enhancing connectedness through: using devices collaboratively such as playing games together (Padilla‐Walker et al. Citation2012); and maintaining relationships when physically apart (Leung and Wei Citation2000; Graham and Sahlberg Citation2021). Possible mechanisms for device use to have a negative influence on attachment are by increasing distractedness through: disrupting parental sensitivity and responsiveness to the child’s cues and signals for attention (Kildare and Middlemiss Citation2017; Wolfers et al. Citation2020; Gutierrez and Ventura Citation2021); displacing interactions such as face-to-face communication (Lepp et al. Citation2016), lowering conversation quality (Przybylski and Weinstein Citation2013) and being a source of family conflict (Rhodes Citation2017). These mechanisms may be bi-directional, as indicated by the finding that higher scores of mother-child interaction quality at 18 months were positively associated with less child screen time at 2 and 3 years of age (Detnakarintra et al. Citation2020).

Much of the related research on mobile touch device screen use has focussed on adults with a recent systematic review finding only very limited evidence concerning associations between time spent using devices by parents and/or children and parent-child attachment (Hood et al. Citation2021). This calls for more quality evidence in this area, including from qualitative research to explore the nature of use, to better understand the potential impacts of device use on parent-child attachment.

This study aimed to explore how and why families with infants use mobile touch screen devices; what influence they perceived this use had on their parent-child attachment; and the mechanisms by which device use may have influenced attachment. An infant age of around 12 months (9–15 months) was chosen as this age is within a critical period for the formation of attachment (6–24 months of age) (Bowlby Citation1980). In addition, research suggests many children at this age are exposed to some use of devices themselves (Ahearne et al. Citation2016; Kabali et al. Citation2015) which may enable a broader understanding of family device use and parent-child attachment.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study design

A qualitative design was used to gain an understanding of parent practices of mobile touch screen device use and their perspectives on the influences of device use on parent-child attachment and family interactions.

Participants were recruited using convenience sampling from a larger longitudinal birth cohort study titled The ORIGINS Project (Silva et al. Citation2020). This unique long-term study, a collaboration between Telethon Kids Institute and Joondalup Health Campus, is one of the most comprehensive studies of pregnant women and their families in Australia to date, recruiting 10,000 families over a decade from the Joondalup and Wanneroo communities of Western Australia. Recruitment of families who were 18 weeks pregnant and attended private and public health services at a general hospital in Perth, Western Australia commenced in 2017.

It is important to note that this study was conducted several months after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, which may have implications for the study outcomes. In addition, Perth in Western Australia is one of the most isolated major cities in the world, and there are more people employed in positions that require them to work at remote job sites than in the general Australian population which may have influenced findings e.g. these families may be more familiar with communicating with family and friends via mobile touch screen devices.

2.2. Recruitment

Participants were eligible if they were available for a qualitative interview either by audio call or video call (due to COVID-19 restrictions), had an infant aged 9–15 months of age at the time of the interview, had sufficient English proficiency and had not previously participated in the prenatal qualitative study and were therefore all new to the research aims and interview questions.

All families who had consented to be part of the ORIGINS Project and had an infant aged 9 to 15 months at the beginning of July 2020 were contacted by mobile phone message. They received brief information about a study on mobile touch screen device use and attachment and were provided with an opportunity to opt-out from further contact within five days of receiving the message. Participants who did not opt-out were grouped into child age in months (from 9 to 15 months at the time of being interviewed) and equal numbers of parents for each age group were contacted via email with detailed information. This was followed by a phone call a few days later to invite them to participate and schedule an interview. Interviews were conducted between July and September 2020. Participants were remunerated with an AUD$50 voucher for participation.

Verbal informed consent was obtained from participants included in the study. Ethics approval was provided by Joondalup Health Campus Human Research Ethics Committee (approval # 1804) and Curtin University Human Research Ethics Committee (approval # HRE2018-0065).

2.3. Data collection/instrument

An interpretive description approach (Thorne et al. Citation1997) was used as a form of qualitative inquiry with the aim of generating knowledge with practical outcomes for family mobile touch screen device use practices and family interactions. This methodological approach (which typically involves one-on-one interviews) leads to broader theorising and contextualising of data compared to sorting and coding, and leads to descriptions of themes that emerge from the analysis as well as themes from existing theory (Klem et al. Citation2022). Using this approach, an interview schedule of questions was designed based on findings from prior research on young children’s screen technology use and in consultation with experts in the field (Appendix A: Interview Schedule). This schedule of interview questions was also reviewed by the ORIGINS Project community reference group.

The interview schedule included open-ended questions pertaining to: (1) family structure, (2) typical mobile touch screen device use practices, (3) perspectives on family device use practices, (4) perspectives on parent-infant attachment in general, and (5) perspectives on perceived influences of device use on parent-infant attachment and other family interactions. Questions related to parent-infant attachment were adapted from the Maternal Postnatal Attachment Scale (Condon Citation2015) and covered the same constructs of attachment as the quantitative scale but in a qualitative approach using open-ended questions on the parent’s thoughts, feelings and behaviours towards their infant. For example, parents were asked: ‘What can you tell me about your relationship with your child? (Further prompts: How you think and feel towards your child? How you behave towards your child?)’

The interviews were conducted by RH under the supervision of JZ and LS. The format of semi-structured interviews was chosen to enable reflective listening and the ability to prompt for further information or clarification to gain an in-depth understanding of participant perspectives and experiences. The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

2.4. Data analysis

Interview transcriptions were entered into the qualitative data analysis software NVivo (QSR International Pty Ltd, 2020) to facilitate organisation and analysis of data. Data were analysed alongside completion of interviews, to monitor whether data saturation was being reached.

Data were analysed by RH using thematic analysis to code and identify emerging themes in an inductive manner, including familiarising with the data via transcribing, reading and re-reading the data, generating codes, searching for themes, reviewing and defining themes (Braun and Clarke Citation2006). To enhance the trustworthiness and credibility of data interpretation, the approach of peer debriefing was used (Lincoln and Guba Citation1985). A second researcher (JZ) independently reviewed the primary analyst’s interpretation of the data. Before themes and sub-themes were finalised, a third reviewer (LS) was consulted.

Data are reported in accordance with the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) Checklist (Tong et al. Citation2007). Once all interviews were completed, participants were contacted by phone for member-checking purposes. Fourteen participants were presented with a summary of key themes and asked if they perceived it to be a reasonable summary; no new information was provided by the participants.

3. Results

3.1. Sample and interview details

There were 282 participants of the ORIGINS Project who were parents of infants aged 9–15 months at the commencement of interview recruitment and were therefore eligible for this sub-project. One hundred potential participants who did not opt-out to further contact received an email and phone call. Thirty of these were willing and able to participate in the interview, providing a response rate of 30%.

For all 30 interviews, the interview was conducted with the mother. Although interviews were available to either/both parent(s), no interviews with fathers were completed. The characteristics of parents who took part are shown in . Interviews were conducted by RH with sixteen conducted by audio-call and fourteen by video-call, according to the preference of the interviewee. On average, the length of the interviews was 56 minutes, ranging from 30 to 76 minutes.

Table 1. Characteristics of mothers.

The mean (range) age of mothers was 34 years (21–42 years) and the mean (range) age of infants was 12.5 months (9–15 months). Most participants were married, and all were currently living with the father of the infant. Half of the participants had one child only, and the other half had between two and five children. The ages of the older children ranged from 3 years to 9 years of age.

Just over half of the participants were currently working in full-time, part-time or casual position, and three of these were also studying concurrently. Six participants were employed but on maternity leave. Most husbands/partners (n = 28) were employed in full-time position. One was employed in a part-time role and one in a casual role. Five husbands/partners had Fly-In-Fly-Out (FIFO) work positions, a term used to describe someone with a work roster that entails flying to a remote job site for a period of time before flying home.

Due to the interviews taking place during the COVID-19 pandemic, questions related to the influence of the pandemic on family interactions and technology use were included and are reported elsewhere (Hood et al. Citation2021).

3.2. Parent-infant attachment

All participants described emotions, perspectives and behaviours that demonstrated affection and commitment towards the infant such as feelings of connection, love and happiness. For example, one participant described: P1 [21yo, 9 mo, no other children] ‘I love him [infant] to bits. He makes me so happy. I can be having a really bad day and then he just smiles at me and then I’m all good.’

Although no participants described ambivalent or affectless thoughts and feelings towards their infants, several parents described challenges they faced while adjusting to parenthood. This included postnatal anxiety and depression, breastfeeding issues, and not being able to go to work due to caring for their infant. For example, one mother described: P27 [41yo, 13 mo, no other children] ‘I had problems breastfeeding at the start and then she was braced [for hips dysplasia] at 10 weeks. So, you know, you kind of lose your newborn cuddles in a way. She was premmie [premature]. There’s like a lot along the way and recently I've kind of imploded from just one too many challenges I think. But hopefully, we’re coming through the other side…But my attachment with her is very strong.’

When asked about ways in which they connect with their infant, parents most frequently described: spending time together, playing, talking, singing songs, reading books, breastfeeding, physical contact, bath time, eye contact and observing their development. The most frequently described hindrances to connecting with their infants included: attending work, having older children to care for, lack of sleep, household chores and infant teething issues.

3.3. Typical device use practices by infants and mothers

3.3.1. Infant use of devices

Televisions were the most commonly used screen device for this age group. Almost all infants routinely viewed television, particularly while parents were preparing for the day and during mealtimes. For example, one participant described: P12 [29yo, 13 mo, no other children] ‘At night-time when [infant] comes home from day-care, we probably put the TV on between when he has his dinner and when he has his bath. So, because he sort of sits in his high chair and watches TV while he eats his dinner.’

For some households, a television was regularly on throughout the day in the background. For example: P4 [38yo, 11 mo, no other children] ‘I'll turn it [television] on generally in the morning and it will just be on all day until we go out.’ In contrast, three mothers stated that their infants had never viewed television and they purposely did not turn the television on while their infants were awake. For example: P6 [38yo, 13 mo, no other children] ‘We actually haven’t put on the TV at all yet. We’re trying to hold off as much as we can. So the TV is never on when she’s awake.’

In terms of mobile touch screen devices, two-thirds of infants (n = 19) were regularly included in family video calls, including calls to extended family in the Eastern States of Australia and overseas, and calls to their mother or father while at their workplace (including parents in FIFO positions). For example: P10 [39yo, 14 mo, no other children] ‘My son uses a lot the mobile because all the family is abroad. So what we usually do during the afternoon, we do video calls with the grannies, auntie, uncles…This is on a daily basis.’ Another described: P26 [33yo, 12 mo, 3yo, 5yo, FIFO husband] ‘That’s the only kind of interaction with my phone that she [infant] has. And it’s obviously, you know, she gets so excited and happy…My mum will play like the piano to her and she’ll, you know…She’ll make happy noises and offer things to the people on my phone. It’s very sweet.’ In all descriptions of family calls involving infants, device use was fully supervised by family members.

Around a third of infants (n = 11) had experienced other uses of mobile touch screen devices including watching nursery rhymes and children’s cartoons, using a colouring-in or flashcard app, taking or viewing photos. For example: P12 [29yo, 13 mo, no other children] ‘She [infant] just takes my phone and walks around with it. Like a lot. She can access the camera which she likes to play with…There’s all these like little videos of me doing things…We have like a couple of little game apps on my phone, which she likes to sometimes play with…She likes to play flashcards, which we will do for like half an hour every day because I couldn’t find any of the good ones, like the physical ones. So I got them on my phone…She watches music videos on YouTube for about an hour.’

For many of the infants who used mobile touch screen devices for purposes other than video calls, device use was rare and constrained to specific situations such as taking medicine, having their nails cut, or on long car journeys. For example: P25 [31yo, 12 mo, 8yo] ‘I think the longest we’ve ever kind of had her in front of it is maybe 15 min watching an episode of Bluey if we’re, you know, trying to get her to take medicine or something equally awful.’ Another described: P4 [38yo, 11 mo, no other children]: ‘Sometimes the iPad is used when we drive and we put it where the mirror is for her, so that she can watch nursery rhymes or listen to music.’ All infant device use for purposes other than video calls was in the direct company of a parent and under their supervision.

A couple of families described placing a mobile touch screen device in their infant’s bedroom overnight to play white noise to aid their infant’s sleep.

3.3.2. Maternal use of devices

There was a broad range of mobile touch screen device use practices among the parents interviewed including limited, moderate and frequent use. For example, one mother explained: P3 [31yo, 10 mo, no other children] ‘I won’t be on my phone unless I've got a call or message or something to attend to.’ In contrast, another parent described: P5 [26yo, 14 mo, no other children] ‘I’m on it pretty much all the time, whether it’s Facebook or emails, or just in general.’

When asked how they felt about their family use of devices, around half described feeling satisfied with their current level of device use. The remaining half stated that they would prefer less use of devices within their family. For example: P13 [37yo, 11 mo, no other children] ‘I definitely feel like my usage is over the top and I would love to cut back…The barrier is my own self-discipline.’

A common theme that emerged was parents being mindful of their own device use in front of their child. For example: P24 [34yo, 12 mo, 3yo, 5yo] ‘I'm very conscious that I don’t use my phone a lot when I'm around the children. That’s one of my things. I don’t like him [infant] seeing me be on the phone all the time.’ Several parents described feelings of guilt, regardless of the duration of use: P27 [41yo, 13 mo, no other children] ‘I really hate it when I'm on it [smartphone], because I feel like she’s just sitting there and doesn’t know what I'm doing and it takes me away from her. So I feel really guilty about that.’ A few parents mentioned being conscious of role modelling their own use of devices to their infants: P22 [41yo, 12 mo, 4yo] ‘I need to be a healthy role model to them. So both in the sense that I don’t want them looking, I don’t want to miss moments with them. I don’t want them looking back or feeling that the phone is more important than them.’

Several parents described routinely using devices while infant feeding. For example: P30 [35yo, 12 mo, 3yo] ‘When I'm breastfeeding, I use a Kindle. Like at the moment she’s only down to feeding at night. But I'd always use it when I'm feeding her at night before bed time…I probably used the phone more when she was first born. And then the Kindle I've been using for six to eight months.’ However, a few other parents mentioned not using devices while infant feeding due to the light from their phone distracting their infant, wanting to make eye contact with their infant while feeding, or it being too difficult to hold the device while feeding: P29 [35yo, 12 mo, 3yo] ‘It’s hard to hold the bottle and him [infant]. I need two hands. I think too, like I did try to use, to not look at my phone as much while feeding, because I’d read that it was really important to make eye contact with them when you’re feeding.’

3.4. Perceived influences of device use on parent-infant attachment and family relationships

3.4.1. Influences of device use on parent-infant attachment

Several participants initially described devices as having no influence on their relationship with their infant. However when given further time for reflection, all described some influence of device use on their interactions and relationship with their infant.

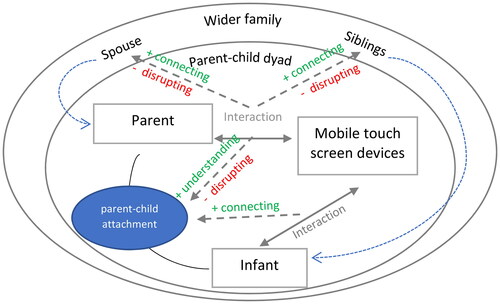

Analysis of the data yielded three key themes in relation to the influence of device use on parent-infant attachment. These themes (which are not mutually exclusive) are displayed in along with example quotes:

Table 2. Influences of device use on parent-infant attachment.

Enabled a better understanding of infancy by accessing information about child development online (e.g. learning about developmental milestones such as when to expect their infant to start crawling or pulling up to stand) and accessing ideas for infant activities online (e.g. learning sensory activities to engage in with the child such as filling water bottles with rice and other materials for the infant to shake and observe);

Enhanced interactions by playing music for the infant (e.g. playing action nursery rhymes on a smartphone and the mother copying the actions), capturing and viewing photos together (particularly in the evening while reflecting on their day together), and connecting to parent at work (e.g. an infant taking part in a video call with a FIFO father that they otherwise would not see for an extended period of time); and

Disrupted interactions by taking the parents’ attention away from their infant (e.g. attending to a device rather than the infant), disrupting the flow of interactions (e.g. receiving a smartphone notification while playing with their infant) and affecting mood/behaviour (e.g. a parent becoming frustrated with their infant for interrupting them while replying to a text message).

Almost all participants (n = 28) contributed data to the first two themes which represent perceived benefits, and two-thirds (n = 21) contributed data to the third theme of perceived downsides of device use in parent-infant attachment.

Devices were also described by a couple of parents as a useful means to view infant images at any time and place, which enhanced the parent experience of connectedness when apart: For example: P5 [26yo, 14 mo, no other children]: ‘You take photos and they’re always stored on your phone. So, you have them as your backdrop or your background, you know, so you’re always looking at her [infant].’

One mother expressed that as a result of being mindful of her own device use, her relationships with her friends had been impacted: P17 [35yo, 15 mo, 3yo] ‘With the time difference on top of the fact that I'm not really on my phone, by the time the kids are in bed it’s too late for me to call friends. So I think I've probably done the reverse, rather than my relationship with the kids suffering, it’s more that my personal relationships suffer.’

3.4.2 Influences of device use on other family relationships

Analysis of the data yielded two key themes in relation to the influence of device use on other family relationships. These two themes (which are not mutually exclusive), displayed in along with representative quotes, were:

Table 3. Influences of device use on other family relationships.

Enhanced interactions between parents (e.g. communicating with each other throughout the day while not physically together), between the parent and older child (e.g co-playing games on a tablet computer), and between siblings (e.g. co-viewing kids shows on a tablet computer); and

Disrupted interactions between parents (e.g. using devices independently while in the company of each other, particularly while watching television together in the evenings), between the parent and older child (e.g. the older child communicating with a parent who is also attending to their device), and between siblings (e.g. one child being absorbed with a device and not responding to their sibling’s attempts for attention).

For parent relationships, several participants described the benefits in maintaining connections during the day, especially for families with a FIFO father. However, almost half of the participants described poorer communication with their partner due to device use. For example: P4 [38yo, 11 mo, no other children] ‘They [devices] help in that when he’s away, we can actually still see each other face to face by video calling each other. So we can feel connected in that way. But I think when he’s around, we probably feel disconnected when we’re in the same room and we’re both just looking at our phones or the TV and not really communicating with each other. So it helps and it doesn’t help, if that makes sense.’

Between parents and their older children, the co-use of a device was described as a benefit by one participant. However, disrupted interactions were described by a few participants, particularly due to the parent attending to their phone while the child was trying to get their attention.

Between siblings, a couple of participants mentioned enhanced interactions between siblings due to shared experiences while using devices. However, several families mentioned that the use of a device by their older child hampered communication and interactions between the older child and their infant sibling by leading them to be less responsive or frustrated when interrupted.

4. Discussion

Overall, the 30 participant families described secure attachment relationships with their infants, characterised by emotions, perspectives and actions that demonstrate affection and commitment to their infant. When asked about influences on parent-child attachment, device use was found to both enhance connection and increase distraction between parents and infants and between other family members.

Two-thirds of infants were routinely involved in family video calls via mobile touch screen devices, which may in part be influenced by the COVID-19 pandemic and related travel restrictions that were ongoing at the time of the study. A third of infants had experienced other uses of mobile touch screen devices and were able to actively engage with the device, supporting other findings where children as young as 12 months old were found to be able to unlock, swipe, and actively look at touch screen devices (Ahearne et al. Citation2016). Overall, the use of devices by infants in this study was for education or maintaining communication and relationships, was constrained to certain situations and was in the company of a parent. Infant device use was typically infrequent and during specific circumstances such as distracting the child while giving them medicine, cutting their nails or taking them on long car journeys. This supports other research of families with some screen exposure by 6 months of age, where almost half of the parents (44%) used devices with their infant while trying to calm them, and a third (30%) used devices while in the company of an adult caregiver during infant mealtimes when putting infants to sleep, and when waiting (p. 2021). Device use by infants for video calls and other purposes was heavily restricted and in the company of a family member and under their close supervision in all descriptions. There is limited available research on the context of device use by children aged around 12 months to enable a comparison. However, a naturalistic observational study of 21 toddlers aged 12–24 months fount that parental mediation of smartphones and tablet computers was primarily focussed on restricting child access, suggesting that this is not uncommon for this age group (Domoff et al. Citation2019).

Among the interviewed mothers, all used devices for a multitude of purposes and there was a broad range of device use practices from minimal to frequent use. Around half of parents were satisfied with their current level of device use, and half stated they would prefer to use their devices less. Similar to other findings (Hiniker et al. Citation2015) many described being mindful, concerned or guilty about their use of devices, regardless of their duration of use.

When looking at the influence of device use on parent-child interactions, the findings provide support for the proposed integrated model of human-computer interaction within a family context, whereby parent and/or child use of mobile touch screen devices may influence parent-child interactions and attachment through a series of potential mechanisms. These mechanisms served to either enhance understanding and connection or disrupt through distraction, as represented in .

Figure 2. Model of perceived influence of mobile touch screen device use on parent-child attachment showing positive (understanding infancy, connecting) and negative (disrupting) mechanisms within the parent-child dyad and wider family system.

The mechanisms that had a positive influence on parent-child attachment included a better understanding of infancy through parent-device interaction for accessing information about child development and accessing ideas of infant activities online, and enhanced connection through child-device interaction of playing music for the infant, capturing and viewing photos together, and connecting to parents while at work. These findings support other qualitative research findings where the main reason for parents using digital devices with their young children was for the purposes of bonding with them (Chen et al. Citation2019). In particular, devices were found in the current study to be a useful tool for refreshing memories of nursery rhyme lyrics and actions, which is a known way of facilitating emotional communication between a mother and child (Creighton Citation2011). For example, an empirical study with 96 mother-infant dyads exploring the effect of music and movement on mother-infant attachment found that mothers in the experimental group who learnt a variety of songs and lullabies and physical actions had a greater perception of the attachment bond than those in the control group (Vlismas et al. Citation2013).

The enhanced connection through parental co-use including viewing of infant photos on a device is supported by the findings of a small laboratory study of 6 mothers where mothers who viewed images of their own infants had increased activation of their orbitofrontal cortex (which correlates to pleasant mood ratings) during functional magnetic resonance imaging compared with mothers who viewed photographs of other infants (Nitschke et al. Citation2004). The ability to view infant photographs on a portable device may be particularly important for parents who are separated from their children while at work or in FIFO positions.

The findings indicate that devices may facilitate mothers’ abilities to develop the necessary characteristics for establishing attachment security (Condon and Corkindale Citation1998) by providing a means to seek: needs gratification and protection (by accessing information online on how to meet the infant’s needs appropriate to their developmental stage); knowledge acquisition (by enabling the parent to better understand their infant and feel a sense of competency as a result) and pleasure in proximity (by interacting with the infant via viewing photos and videos together).

The mechanisms that had a negative influence on parent-child attachment disrupted interactions through taking the parents’ attention away from their infant, disrupting the flow of interactions, and indirectly by affecting mood or behaviour. These results support a recent experimental study of Israeli mothers and their 24- to 36-month-old toddlers, where mothers were found to be less responsive to child bids for attention and exchanged in fewer conversational turns when engaged with a smartphone than during uninterrupted free-play (Lederer et al. Citation2022). The finding that parents in the current study were less attentive and less present with their infants while engaged with their device and experienced altered child mood and behaviour adds further evidence to the theory of the ‘Still Face Paradigm’ which posits that initiating and responding to child social cues is important for connection (Braungart-Rieker et al. Citation1998), and a lack of these parent reactions is associated with increased negative affect such as infant distress and confusion (Myruski et al. Citation2018). The use of smartphones by parents while in the company of their infant may disrupt parent-infant engagement and lead to a still face, as evidenced by a recent scoping review where the use of smartphones by parents of 0–5-year-olds was found to be associated with decreased parental sensitivity and responsiveness (Braune-Krickau et al. Citation2021), which are key elements in the formation of a secure attachment (Ainsworth et al. Citation1974). This decreased parent responsiveness and subsequent infant distress have been exemplified in a TED Talk demonstrating the impact of parent device use during parent-infant interactions (Mindaroo Foundation, Citation2021). Although not evident in the findings of the current study it is possible that the reverse relationship may be true, whereby infants’ behaviours, temperaments and responses to devices may shape how and when mothers use their devices. No perceived negative effects of child device use on parent-child attachment was described in this study. However, this may be due to the low levels of infant device use among families included in the study.

When asked about the influence of device use on other family relationships, similar mechanisms of enhanced connection when devices were used collaboratively and increased distraction when used independently while in the presence of each other were found, for both spouse and sibling interactions (see ). For example, devices appeared to enhance parents’ relationships with their spouse when used as a tool for communicating when physically apart but served to disrupt relationships when used independently in each other’s company. This supports the findings of other qualitative research on 66 married couple dyads which found that interactive technologies (mobile phones, internet and social networking sites) facilitated communication and connection, yet also led to distraction and challenged marital boundaries (Vaterlaus and Tulane Citation2019).

The findings indicate that influences on the wider layer of other family relationships should also be considered when investigating influences of device use on the inner parent-child dyad layer of the proposed model of device use in an integrated family system. This is because there may be links between wider family relationships and the security of parent-child attachment, as represented by the curved dotted arrows in . For example, marital relationship dissatisfaction is associated with an increased risk of depression and anxiety (Pilkington et al. Citation2015), which in turn is associated with lower levels of parent-child attachment security (Teti et al. Citation1995; Badovinac et al. Citation2018). In addition, higher scores of sibling attachment are associated with fewer depressive symptoms and greater self-worth (Noel et al. Citation2018), and child depression symptoms have been found to be associated with insecure attachment to primary caregivers (although this association is likely to be bi-directional) (Spruit et al. Citation2020). These potential indirect mechanisms highlight the complex interactions influencing parent-child interaction.

Overall, the findings of this study indicate that how families interact with mobile touch screen devices is important in whether device use is beneficial or detrimental to parent-child and other family relationships. In particular, the nature of how parents interacted with screens was important rather than simply the amount of screen use. The intentional use of devices for the purposes of accessing infant-related information, playing music for the infant and capturing and viewing photos together appeared to enhance connectedness between parents and their infants, whereas general use of devices for checking notifications and scrolling through social media while in the company of their infant served to disrupt interactions.

Although parents may have traditionally acquired child development knowledge or been less engaged with their child due to other means (e.g. reading a hard copy book), there are some key differences with mobile touch screen devices. The portability and ease of access to devices may lead to increased opportunities for both enhanced connection and distraction.

The mechanisms may be the same for wider family relationships, however, other factors such as autonomy and access to devices for older family members (e.g. between marital partners) may play an important role. In addition, relationships between device use and family connectedness are likely to be bi-directional in nature (Detnakarintra et al. Citation2020), and there is evidence to suggest that families with inherently strong bonds are more likely to be enriched by the use of devices in terms of social interaction whereas families with inherently vulnerable bonds are more likely to be weakened by the use of devices (Dmitrii Citation2020).

5. Implications of the findings

The implication for theoretical work in this area is that the proposed model of human-computer interaction in a family system that is based on concepts of human-computer interaction (Beamish et al. Citation2019), family systems theory (Bronfenbrenner and Morris Citation2006), the bio-ecological model (Bowlby Citation1980) and parent-child attachment (Ainsworth et al. Citation1978) was a useful framework for investigating and reporting potential mechanisms and demonstrates that the nature of screen use is important to consider rather than simply the amount of screen use.

In terms of practical implications, this study provides unique information on human-computer interactions within a family systems context among families of infants, and what influences parents perceive this interaction has on their thoughts, feelings and behaviours towards their infant and on wider family relationships.

As represented in , the findings suggest that some engagement with technology can improve forming a bond between the mother and infant, particularly when devices are used specifically for accessing information about child development and parenting online using well-known and trusted sources of information, accessing ideas for infant activities online, playing music for the infant, learning lyrics and actions to nursery rhymes, capturing and viewing photos together, and connecting with parents virtually while they are at work. The results also indicate that while there are some potential benefits to using devices during among families with infants, parents should also be mindful of what they are using devices for as they can be distracting, especially when used without a specific purpose. Given the importance of parent-infant attachment to future child outcomes (including cognitive, physical and socio-emotional outcomes), this knowledge is useful in guiding families and professionals who provide services to families in order to optimise future child development.

In terms of wider family relationships (e.g. siblings and the marital relationship), the practical implications are that using devices collaboratively while together or to communicate while apart can enhance interactions and perceptions of connectedness, while using devices independently while in each other’s presence can diminish interactions and lead to feelings of disconnectedness.

6. Strengths and Limitations

6.1. Strengths

This paper advances research on the influence of device use on parent-infant attachment, an area in need of research due to the rapid advancement in technology use among families of young children, and highlights the importance of using technology wisely.

The qualitative interview approach enabled reflective listening and further prompting when required, which provided rich and detailed information of family perspectives and experiences. Parents were asked to reflect on their current family experiences which may have led to reduced memory bias while participating in the interviews. Further strengths include the involvement of a consumer group in refining interview questions to ensure the relevance of the content, and member checking to enhance the trustworthiness of the data.

In addition, the study proposed and refined a model of family human-computer interaction that acknowledges the importance of considering an additional layer of the wider family on parent-child attachment and device use which recognises that influences do not occur in isolation but as part of a family system.

6.2. Limitations

A limitation was that a convenience sample was used which did not include families with some characteristics that could influence device use and parent-child attachment e.g. single parents, fathers, and parents with perceived insecure attachments. The study participants had high levels of education, occupation and income which may be associated with higher levels of attachment and lower levels of technology use by both parents and infants. There were no perceived negative effects of child device use on parent-child attachment found in this study which could have been caused by sample bias. In addition, the participation rate of the convenience sample was relatively low which may have introduced selection bias where those who participated may have differed to those who did not.

A further limitation of the study is the potential for social desirability bias where participants are inclined to provide what they perceive to be socially desirable responses instead of expressing true device use practices and perspectives on perceived attachment to their infant. Interviews were conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, and there is a potential for social changes associated with the pandemic to influence device use and family interactions, which may affect the generalisability of findings. For example, infants may have been involved in family video calls via touch screen devices to a greater extent than usual due to pandemic-related restrictions.

7. Future research

Our work here suggests several lines of future research. To better inform tailored technology use the advice to families, studies of attachment and mobile touch screen device use entailing large, more representative samples of families differentiated by diverse family structures and stratified by developmental ages (e.g. toddlers, pre-schoolers and grade-schoolers) are needed. In addition, the use of time diaries, touch technology time-stamps or observational studies in situ would be useful to address to address potential biases in self-reports of mobile device use.

Further areas of research could include longitudinal studies of parent-child attachment, mobile touch screen device use and child developmental outcomes to inform directions of associations, investigation of other potential factors that influence parent-infant attachment, and randomised control trials to explore the use of technology to support attachment security. Exploring reasons for why parent use devices while in the company of their child would also be useful for better informing family device use guidelines.

The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on mobile touch screen device use and parent-child attachment is also important to explore, as there is the potential for pandemic-related restrictions to have an influence on both the use of devices and family dynamics.

8. Conclusions

The findings shed light as to how parent and/or infant mobile touch screen device use may affect the parent’s perceived relationship with their infant. Reasons for which devices were used appeared to be important, rather than simply the amount of screen time. When used for the for the purposes of accessing infant-related information, virtual communication, playing music for the infant and capturing and viewing photos together, devices were perceived to enhance feelings of connectedness between parents and their infants.

However, the general use of devices for checking notifications and scrolling through social media while in the company of their infant served to disrupt interactions and led to parents feeling a sense of disconnection to them. Among other family members such as siblings and the marital relationship, device use enhanced feelings of connectedness when used collaboratively together or for communication purposes while apart, and led to feelings of distractedness and disconnectedness when used independently in the presence of each other.

The findings will be useful for providing information for families with infants on how they can take advantage of devices for the purposes of enhancing interactions and relationships while being aware of potential downsides.

Acknowledgements

The ORIGINS Project is only possible because of the commitment of the families in ORIGINS. We are grateful to all the participants, health professionals and researchers who support the project. We would also like to acknowledge and thank the following teams and individuals who have made the ORIGINS Project possible: The ORIGINS Project team; CEO Dr Kempton Cowan, executive staff and obstetric, neonatal and paediatric teams, Joondalup Health Campus (JHC); Director Professor Jonathan Carapetis and executive staff, Telethon Kids Institute; Mayor Tracey Roberts, City of Wanneroo; Mayor Albert Jacobs, City of Joondalup; Professor Fiona Stanley, patron of ORIGINS; members of ORIGINS Community Reference and Participant Reference Groups; Research Interest Groups and the ORIGINS Scientific Committee. The authors thank the ORIGINS Project community reference group for their advice regarding the interview schedule. RH, JZ and LS are members of the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for the Digital Child (CE200100022).

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

This research was supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) Scholarship. The ORIGINS Project has received core funding support from the Telethon Perth Children’s Hospital Research Fund, Joondalup Health Campus, the Paul Ramsay Foundation and the Commonwealth Government of Australia through the Channel 7 Telethon Trust. Substantial in-kind support has been provided by Telethon Kids Institute and Joondalup Health Campus and costs associated with the current study were funded by a Curtin University Early Career Grant led by JZ. SRZ is supported by a Centre of Excellence grant from the Australian Research Council (CE140100027).

References

- Ahearne, C., S. Dilworth, R. Rollings, V. Livingstone, and D. Murray. 2016. “Touch-Screen Technology Usage in Toddlers.” Archives of Disease in Childhood 101 (2): 181–183. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2015-309278.

- Ainsworth, M., M. Blehar, E. Waters, and S. Wall. 1978. Patterns of Attachment: A Psychological Study of the Strange Situation. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Ainsworth, M.D.S., S.M. Bell, and D.F. Stayton. 1974. “Infant–Mother Attachment and Social Development: Socialization as a Product of Reciprocal Responsiveness to Signals.” In The Integration of a Child into a Social World, edited by Richards M. P. M., 99–135. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Alzhrani, A. M., K. R. Johnstone, E. A. H Winkler, G. N. Healy, and M. M. Cook. 2022. “Using Touchscreen Mobile Devices—When, Where and How: A One-Week Field Study.” Ergonomics 65 (4): 561–572. doi:10.1080/00140139.2021.1973577.

- Badovinac, S., J. Martin, C. Guérin-Marion, M. O'Neill, R. Pillai Riddell, J.-F. Bureau, and R. Spiegel. 2018. “Associations between Mother-Preschooler Attachment and Maternal Depression Symptoms: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” PLOS One 13 (10): e0204374. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0204374.

- Beamish, N., J. Fisher, and H. Rowe. 2019. “Parents’ Use of Mobile Computing Devices, Caregiving and the Social and Emotional Development of Children: A Systematic Review of the Evidence.” Australasian Psychiatry 27 (2): 132–143. doi:10.1177/1039856218789764.

- Bohlin, G., B. Hagekull, and A. Rydell. 2000. “Attachment and Social Functioning: A Longitudinal Study from Infancy to Middle Childhood.” Social Development 9 (1): 24–39. doi:10.1111/1467-9507.00109.

- Bordeleau, S., A. Bernier, and J. Carrier. 2012. “Longitudinal Associations between the Quality of Parent Child Interactions and Children’s Sleep at Preschool Age.” Journal of Family Psychology 26 (2): 254–262. doi:10.1037/a0027366.

- Bowlby, J. 1980. Attachment and Loss. Loss, Sadness and Depression. 3 Vols. New York: Basic Books.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Braune-Krickau, K., L. Schneebeli, J. Pehlke-Milde, M. Gemperle, R. Koch, and A. von Wyl. 2021. “Smartphones in the Nursery: Parental Smartphone Use and Parental Sensitivity and Responsiveness within Parent-Child Interaction in Early Childhoon (0–5 Years): a Scoping Review.” Infant Mental Health Journal 42 (2): 161–175. doi:10.1002/imhj.21908.

- Braungart-Rieker, J., M.M. Garwood, B.P. Powers, and P.C. Notaro. 1998. “Infant Affect and Affect Regulation during the Still-Face Paradigm with Mothers and Fathers: The Role of Infant Characteristics and Parental Sensitivity.” Developmental Psychology 34 (6): 1428–1437. doi:10.1037//0012-1649.34.6.1428.

- Bronfenbrenner, U., and P. Morris. 2006. “The Bioecological Model of Human Development.” In Handbook of Child Psychology: Vol. 1. Theoretical Models of Human Development, edited by R. M. Lerner & W. Damon, 6th ed., 793–828. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Brumariu, L.E. 2015. “Parent-Child Attachment and Emotion Regulation.” New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development 2015 (148): 31–45. doi:10.1002/cad.20098.

- Chen, C., M.H. Teo, and D. Nguyen. 2019. “Singapore Parents’ Use of Digital Devices with Young Children: Motivations and Uses.” The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher 28 (3): 239–250. doi:10.1007/s40299-019-00432-w.

- Cheung, C.H.M., R. Bedford, I.R. Saez De Urabain, A. Karmiloff-Smith, and T.J. Smith. 2017. “Daily Touchscreen Use in Infants and Toddlers is Associated with Reduced Sleep and Delayed Sleep Onset.” Scientific Reports 7 (1): 46104–46104. doi:10.1038/srep46104.

- Coenen, P., H. van der Molen, A. Burdorf, M. Huysmans, L. Straker, M. Frings-Dresen, and A. van der Beek. 2019. “The Association of Screen Work with Neck and Upper Extremity Symptoms: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis.” Occupational and Environmental Medicine 76 (7): 502–509. doi:10.1136/oemed-2018-105553.

- Condon, J. 2015. Maternal postnatal attachment scale [Measurement instrument]. http://hdl.handle.net/2328/35291

- Condon, J. T., and C. J. Corkindale. 1998. “The Assessment of Parent-to-Infant Attachment: Development of a Self-Report Questionnaire Instrument.” Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology 16 (1): 57–76. doi:10.1080/02646839808404558.

- Creighton, A. 2011. “Mother-Infant Musical Interaction and Emotional Communication: A Literature Review.” Australian Journal of Music Therapy 22: 37–58.

- Detnakarintra, K., P. Trairatvorakul, C. Pruksananonda, and W. Chonchaiya. 2020. “Positive Mother-Child Interactions and Parenting Styles Were Associated with Lower Screen Time in Early Childhood.” Acta Paediatrica 109 (4): 817–826. doi:10.1111/apa.15007.

- Dmitrii, D.I. 2020. “Information and Communication Technologies and Family Relations: Harm or Benefit?” Social Psychology and Society 11 (1): 72–91.

- Domoff, S.E., J.S. Radesky, K. Harrison, H. Riley, J.C. Lumeng, and A.L. Miller. 2019. “A Naturalistic Study of Chid and Family Screen Media and Mobile Device Use.” Journal of Child and Family Studies 28 (2): 401–410. 10.1007/s10826-018-1275-1

- Fleming, S. E., R. Vandermause, and M. Shaw. 2014. “First-Time Mothers Preparing for Birthing in an Electronic World: Internet and Mobile Phone Technology.” Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology 32 (3): 240–253. doi:10.1080/02646838.2014.886104.

- Graham, A., and P. Sahlberg. 2021. Growing up Digital Australia: Phase 2 Technical Report. Sydney: Gonski Institute for Education, UNSW.

- Groh, A.M., R.P. Fearon, M.J. Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.H. van IJzendoorn, R.D. Steele, and G.I. Roisman. 2014. “The Significance of Attachment with Security for Children’s Social Competence with Peers: A Meta-Analytic Study.” Attachment & Human Development 16 (2): 103–136. doi:10.1080/14616734.2014.883636.

- Gurcan, F., N.E. Cagiltay, and K. Cagiltay. 2021. “Mapping Human-Computer Interaction Research Themes and Trends from Its Existence to Today: A Topic Modeling-Based Review of past 60 Years.” International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction 37 (3): 267–280. doi:10.1080/10447318.2020.1819668.

- Gutierrez, S., and A. Ventura. 2021. “Associations between Maternal Technology Use, Perceptions of Infant Temperament, and Indicators of Mother-to-Infant Attachment Quality.” Early Human Development 154: 105305–105305. doi:10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2021.105305.

- Han, H., S. Lee, and G. Shin. 2019. “Naturalistic Data Collection of Head Posture during Smartphone Use.” Ergonomics 62 (3): 444–448. doi:10.1080/00140139.2018.1544379.

- Harris, C., and L. Straker. 2000. “Survey of Physical Ergonomics Issues Associated with School Children’s Use of Laptop Computers.” International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics 26 (3): 337–346. doi:10.1016/S0169-8141(00)00009-3.

- Hiniker, A., K. Sobel, H. Suh, Y. C. Sung, C. P. Lee, and J. A. Kientz. 2015. April). “Texting While Parenting: How Adults Use Mobile Phones While Caring for Children at the Playground.” In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 727–736.

- Hood, R., J. Zabatiero, D. Silva, S.R. Zubrick, and L. Straker. 2022. “There’s Good and Bad”: Parent Perspectives on the Influence of Mobile Touch Screen Device Use on Prenatal Attachment.” Ergonomics 65 (12): 1593–1608. doi:10.1080/00140139.2022.2041734.

- Hood, R., J. Zabatiero, D. Silva, S.R. Zubrick, and L. Straker. 2021. “Coronavirus Changed the Rules on Everything”: Parent Perspectives on How the COVID-19 Pandemic Influenced Family Routines, Relatinoships and Technology Use in Families with Infants.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18 (23): 12865. doi:10.3390/ijerph182312865.

- Hood, R., J. Zabatiero, S.R. Zubrick, D. Silva, and L. Straker. 2021. “The Association of Mobile Touch Screen Device Use with Parent-Child Attachment: A Systematic Review.” Ergonomics 64 (12): 1606–1622. doi:10.1080/00140139.2021.1948617.

- Kabali, H.K., M.M. Irigoyen, R. Nunez-Davis, J.G. Budacki, S.H. Mohanty, K.P. Leister, and J.R.L. Bonner. 2015. “Exposure and Use of Mobile Media Devices by Young Children.” Pediatrics 136 (6): 1044–1050. doi:10.1542/peds.2015-2151.

- Kildare, C. A., and W. Middlemiss. 2017. “Impact of Parents Mobile Device Use on Parent-Child Interaction: A Literature Review.” Computers in Human Behavior 75: 579–593. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2017.06.003.

- Klem, N.-R., N. Shields, A. Smith, and S. Bunzli. 2022. “Demystifying Qualitative Research for Musculoskeletal Practioners Part 3: Phenomeno-What? Understanding What the Qualitative Researchers Have Done.” The Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy 52 (1): 3–7. doi:10.2519/jospt.2022.10485.

- Lederer, Y., H. Artzi, and K. Borodkin. 2022. “The Effects of Maternal Smartphone Use on Mother-Child Interaction.” Child Development 93: 556–570.

- Lepp, A., J. Li, and J. E. Barkley. 2016. “College Students’ Cell Phone Use and Attachment to Parents and Peers.” Computers in Human Behavior 64: 401–408. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2016.07.021.

- Leung, L., and R. Wei. 2000. “More than Just Talk on the Move: Uses and Gratifications of the Cellular Phone.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 77 (2): 308–320. doi:10.1177/107769900007700206.

- Lincoln, Y., and E. G. Guba. 1985. Naturalistic Inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Mindaroo Foundation. (2021, August 9). Molly Wright: How every child can thrive by five TED Talk. [Video file]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aISXCw0Pi94

- Myruski, S., O. Gulyayeva, S. Birk, K. Pérez-Edgar, K.A. Buss, and T.A. Dennis-Tiwary. 2018. “Digital Disruption? Maternal Mobile Device Use is Related to Infant Social-Emotional Functioning.” Developmental Science 21 (4): e12610. doi:10.1111/desc.12610.

- Nitschke, J.B., E.E. Nelson, B.D. Rusch, A.S. Fox, T.R. Oakes, and R.J. Davidson. 2004. “Orbitofrontal Cortex Tracks Positive Mood in Mothers Viewing Pictures of Their Newborn Infants.” NeuroImage 21 (2): 583–592. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.10.005.

- Noel, V. A., S. E. Francis, and M. A. Tilley. 2018. “An Adapted Measure of Sibling Attachment: factor Structure and Internal Consistency of the Sibling Attachment Inventory in Youth.” Child Psychiatry and Human Development 49 (2): 217–224. doi:10.1007/s10578-017-0742-z.

- Padilla‐Walker, L. M., S. M. Coyne, and A. M. Fraser. 2012. “Getting a High‐Speed Family Connection: associations between Family Media Use and Family Connection.” Family Relations 61 (3): 426–440. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3729.2012.00710.x.

- Pew Research Centre. 2021. Internet and Technology: Mobile Fact Sheet. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/mobile/

- Pilkington, P., L. Milne, K. Cairns, J. Lewis, and T. Whelan. 2015. “Modifiable Partner Factors Associated with Perinatal Depression and Anxiety: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Affective Disorders 178: 165–180. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2015.02.023.

- Przybylski, A., and N. Weinstein. 2013. “Can You Connect with Me Now? How the Presence of Mobile Communication Technology Influences Face-to-Face Conversation Quality.” Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 30 (3): 237–246. doi:10.1177/0265407512453827.

- Rees, C. A. 2005. “Thinking about Children’s Attachments.” Archives of Disease in Childhood 90 (10): 1058–1065. doi:10.1136/adc.2004.068650.

- Rhodes, A. 2017. Screen Time: What’s Happening in Our Homes? Detailed Report. Melbourne, Victoria: The Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne. https://www.childhealthpoll.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/ACHP-Poll7_Detailed-Report-June21.pdf.

- Rhodes, A. 2017. Screen time: What’s happening in our homes? https://www.childhealthpoll.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/ACHP-Poll7_Detailed-Report-June21.pdf

- Schore, A. N. 2001. “Effects of a Secure Attachment Relationship on Right Brain Development, Affect Regulation, and Infant Mental Health.” Infant Mental Health Journal 22 (1–2): 7–66. doi:10.1002/1097-0355(200101/04)22:1<7::AID-IMHJ2>3.0.CO;2-N.

- Silva, D. T., E. Hagemann, J. A. Davis, L. Y. Gibson, R. Srinivasjois, D. J. Palmer, L. Colvin, J. Tan, and S. L. Prescott. 2020. “Introducing the ORIGINS Project: A Community-Based Interventional Birth Cohort.” Reviews on Environmental Health 35 (3): 281–293. doi:10.1515/reveh-2020-0057.

- Spruit, A., L. Goos, N. Weenink, R. Rodenburg, H. Niemeyer, G. Jan Stams, and C. Colonnesi. 2020. “The Relation between Attachment and Depression in Children and Adolescents: A Multilevel Meta Analysis.” Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review 23 (1): 54–69. doi:10.1007/s10567-019-00299-9.

- Straker, L., and C. Pollock. 2005. “Optimizing the Interaction of Children with Information and Communication Technologies.” Ergonomics 48 (5): 506–521. doi:10.1080/00140130400029233.

- Straker, L., R. Abbott, R. Collins, and A. Campbell. 2014. “Evidence-Based Guidelines for Wise Use of Electronic Games by Children.” Ergonomics 57 (4): 471–489. doi:10.1080/00140139.2014.895856.

- Teti, D.M., D. Gelfand, D. Messinger, and R. Isabella. 1995. “Maternal Depression and the Quality of Early Attachment: An Examination of Infants, Preschoolers, and Their Mothers.” Developmental Psychology 31 (3): 364–376. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.31.3.364.

- Thorne, S., S. Reimer Kirkham, and J. MacDonald-Emes. 1997. “Interpretive Description: A Noncategorical Qualitative Alternative for Developing Nursing Knowledge.” Research in Nursing & Health 20 (2): 169–177. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-240X(199704)20:2<169::AID-NUR9>3.0.CO;2-I.

- Tong, A., P. Sainsbury, and J. Craig. 2007. “Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ): A 32-Item Checklist for Interviews and Focus Groups.” International Journal for Quality in Health Care 19 (6): 349–357. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzm042.

- Vaterlaus, J.M, and S. Tulane. 2019. “The Perceived Influence of Interactive Technology on Marital Relationships.” Contemporary Family Therapy 41 (3): 247–257. doi:10.1007/s10591-019-09494-w.

- Vlismas, W., S. Malloch, and D. Burnham. 2013. “The Effects of Music and Movement on Mother-Infant Interactions.” Early Child Development and Care 183 (11): 1669–1688. doi:10.1080/03004430.2012.746968.

- West, K., B. Mathews, and K. Kerns. 2013. “Mother-Child Attachment and Cognitive Performance in Middle Childhood: An Examination of Mediating Mechanisms.” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 28 (2): 259–270. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2012.07.005.

- White, J., and D. Klein. 2008. The Systems Framework. Family Theories. 3rd ed., 151–177. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Wiltshire, C.A., S.V. Troller-Renfree, M.A. Giebler, and K.G. Noble, p 2021. “Associations among Average Parental Educational Attainment, Maternal Stress, and Infant Screen Exposure at 6 Months of Age.” Infant Behavior and Development 65: 101644. doi:10.1016/j.infbeh.2021.101644.

- Wolfers, L., S. Kitzmann, S. Sauer, and N. Sommer. 2020. “Phone Use While Parenting: An Observational Study to Assess the Association of Maternal Sensitivity and Smartphone Use in a Playground Setting.” Computers in Human Behavior 102: 31–38. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2019.08.013.

- Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., H. J. Webb, C. A. Pepping, K. Swan, O. Merlo, E. A. Skinner, E. Avdagic, and M. Dunbar. 2017. “Review: Is Parent-Child Attachment a Correlate of Children’s Emotion Regulation and Coping?” International Journal of Behavioral Development 41 (1): 74–93. doi:10.1177/0165025415618276.

Appendix A.

Interview Schedule

“It helps and it doesn’t help”. Maternal perspectives on how the use of smartphones and tablet computers influences parent-infant attachment – by Hood et al.

Prior to initiating the interview: Researcher introduces themselves, gives a summary of the project aim and procedures (including audio recording), clarifies any queries participant may have about the study, provides definitions for terms used (e.g. screen devices) and obtains participant consent to be interviewed and for the information we collect as part of this study to be shared with the ORIGINS Databank.

Can you tell me about your family?

Where do you live?

Who lives with you? (e.g. adults and marital status, children (gender, age))

Working status for yourself and your partner (if applicable), school/kindy status for children (if applicable), typical weekly routines (work/school/kindy) (pre-pandemic)

Have your family’s work/child care arrangements changed as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic?

Can you tell me about the type of screen devices you and your family have in the home?

How many screen devices and what type?

Where these screen devices are located in the home?

Who has access to the screen devices and when?

Are any of these screen devices used outside of the home (e.g. car trips, shops, work/school, parks, family and friends’ houses)

Can you tell me what a typical week of screen device use would look like for you and each of your family (partner and child(ren) if applicable)?

Let’s start with your week – on Mondays what devices do you use in the morning….are the other week days similar? Is your use of screens different on Saturday? on Sunday?

Home vs outside of the home (work/school)?

What types of programmes or activities/apps are watched/done with each screen device and by whom?

How are the screen devices used (individually/collaboratively)?

How do you feel about your family’s current screen use practices?

How has your family’s technology use practices changed from pregnancy to now? Is your family’s current use of technology different to what you expected it to be?

Has your family’s use of screen devices changed as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic?

Can you tell me about the reasons why you and your family use screen devices?

What do you and your family use the screen devices for?

You, partner, each child (if applicable)

What do you and your family expect from the use of screen devices?

Can you tell me more about how you and your family manage the use of screen devices?

Have you considered or discussed any strategies you and your family use to decide how or when to use screen devices?

If so, can you tell me more about it (who developed them? How are they used?)

What else has influenced your decisions around screen use?

We would like to better understand what your relationship is like with your infant.

What can you tell me about your relationship with your child? (e.g. how you think and feel towards your child? How you behave towards your child?)

How has your relationship with your child changed from pregnancy to now?

What do you think helps you connect with your child?

What do you think hinders you from being connected with your child?

Has your relationship with your child changed as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic?

We would like to know your thoughts on how the use of screen devices, particularly mobile touchscreen devices, by you and/or other members of your family may influence, in any way…

The relationship between you and your child? e.g. how you think and feel towards your child? How you behave towards your child? What screen device use practices help you connect with your child? What screen device use practices distract you from being connected with your child?

The interactions between the family members?

e.g. You and your partner/family members other than children: how you think/feel/behave towards each other; how much time you spend together

e.g. Your partner and your child(ren)(if applicable): how he/she thinks/feels/behaves towards the child; how much time he/she spends with the child

e.g. Your children (if applicable): how they think/feel/behave towards each other; how much time they spend together

How do you think the influence of device use on relationships in your family has changed from pregnancy to now? Do you think the influence of device use on relationships is different to what you expected it to be?

How do you think the influence of device use on the relationship between you and your child (and other relationships within your family) has changed as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic?

We would like to know your thoughts on how the use of screen devices, particularly mobile touchscreen devices, by you and/or other members of your family may influence, in any way…

How your child(ren) learns (e.g. how they explore the environment, learn to solve problems, copy/mimic your actions such as scribbling with a pen on paper)

How your child(ren) communicates with other people (e.g. play games such as peekaboo, clap hands, wave bye-bye, says words other than mama and dada, points at objects, hugs a doll or stuffed animal)

How your child(ren) develops physically (e.g. how they learn to hold different objects, throw a ball, turn pages of a book, sit/crawl/stand up/walk)

How do you think the influence of device use on how your child is developing these skills has changed as a result of the coronavirus?

How do you think the influence of device use on how your child is developing these skills has changed as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic?

What kind of information would you find useful to help guide your family’s use of mobile touch screen devices?

How would you like to receive that information? (e.g. online seminar, brochure, through your playgroup)