ABSTRACT

New York Stories aims to research and represent the realms of inner expression that constitute people's lived experiences of urban space but remain beneath the surface of their public activity. The capacity for a complex inner lifeworld – consisting of inner speech, inchoate trajectories of thought, unarticulated moods, random urges, unsymbolised thinking, imagination, sensation, memory – is a distinctive feature of human experience that mediates many realms of everyday life, action and practice. By placing the problem of interiority directly into the field and turning it into an ethnographic, practice-based question to be addressed in collaboration with informants, New York Stories can be seen as an ethnographic attempt to research and represent the everyday experience of living with HIV/AIDS in New York's Lower East Side by examining the complex trajectories of thinking and being that are played out in public spaces but are not necessarily externalised.

‘Anthropology Is Philosophy with the People in’ (Ingold Citation1992: 696) in that it explores fundamental questions about the human condition but does so by grounding these in the social, moral and political lives of people around the world. Anthropology is simultaneously a fieldwork science and documentary art (Davis Citation2000) that carries out practical research in the midst of other people's lives, and then uses written texts, images, objects and recordings to communicate its theories and findings. One of the earliest considerations of anthropology, both as a philosophical and practical discipline, was Kant's course on anthropology that he taught for 23 continuous years from 1772 until 1796. Anthropology was a completely new field at the time and Kant's course and subsequent book, Anthropology: From a Pragmatic Point of View (1798) was one of the very first attempts to offer a systematic, anthropological approach to understanding humanity.

For Kant, a fundamental obstacle for the development of anthropological science was how to establish the theoretical and practical grounds for understanding the relationship between people's inner beings and their observable actions. Accordingly, Anthropology: From a Pragmatic Point of View is organised into two distinct but related parts: Part One: ‘Anthropological Didactic: On the Way of Cognising the Interior as Well as the Exterior of the Human Being' and Part Two: ‘Anthropological Characteristic: On the Way of Cognising the Interior of the Human Being from the Exterior’.

In organising his book along these lines, Kant anticipates some of the major epistemological and methodological problems encountered by anthropologists in the field, including how to relate people's subjective perceptions and moral understandings to their public utterances, observable actions and communal behaviours. Although, contemporary anthropology would not postulate such a strict division between inner and outer, the central problem of how to interpret people's observable and audible actions remains. Although Kant saw anthropological observation as necessary for understanding the practical basis of human knowledge and action, he freely acknowledged the methodological limitations of this approach, including how the observer can never fully participate in any social situation if they are observing or analysing it, even if the object of observation is oneself insofar as when observing ‘his inner self [he] can only recognise himself as he appears to himself, not as he absolutely is’ (Kant Citation2006: 30).

While related to his philosophy, anthropology is its own discipline that uses empirical observations of everyday social life and practice, alongside the kinds of knowledge about human beings that can be gleaned from sources such as literature, biographies world history, plays, poetry and travel accounts of other cultures (which Kant also saw as valid sources). It is instructive that more than two centuries after Kant's attempts to offer a systematic understanding of the relationship between the ‘sensus interior’ of human beings and their outward appearances, a major problem for anthropology remains how to read, understand and theorise other people's intentions, actions and practices when carrying out participant observation in the field. The presence of an inner lifeworld beyond third-party observation and knowledge is fundamental to many aspects of social life, action and practice, and is an essential part of what makes us human. Without inner modes of expression and experience, including inner dialogue and internally represented speech (see Irving Citation2007, Citation2011, Citation2013, Citationforthcoming; Hogan & Pink Citation2010) there would be no social existence or understanding – at least not in a form we would recognise – and many routine aspects of daily life and social interaction would be severely compromised, including people's abilities to theorise, understand and plan their actions or when making interpretations about other persons and situations. Social relationships, acts of strategy, deception and secrecy would be rendered impossible, as persons would be unable to simultaneously hold thoughts, intentions and knowledge that differ from their public expressions.

From Evans-Pritchard's declaration that individual perceptions have ‘no wider collective validity’ and that the ‘subject bristles with difficulties’ (Citation1969: 107), through Geertz's (Citation1973) long-standing commitment to external, publicly observable symbols as the primary realm of anthropological study, to Bourdieu's dismissal of interest in lived experience as a complacent form of ‘flabby humanism’ (Citation1990: 5), the potential problems and pitfalls that are encountered when making anthropological claims about people's inner lifeworlds mean that they remain unrepresented within many ethnographic accounts. A possible reason why people's interior expressions (Irving Citation2007) and imaginative lifeworlds are ‘virtually absent’ (Csordas Citation1997: 79) as topics of ethnographic research is their potential to invalidate anthropological truth claims concerning people's intentions, actions and worldviews. At times, the constitution and character of people's inner expressions might even be diametrically opposed to their public expressions – an experience no doubt familiar to many anthropologists in the field and their own social lives – thereby threatening to undermine the evidential grounds for making claims based upon the observation and interpretation of extrinsic forms.

The epistemological privilege frequently granted to the exterior within contemporary philosophy and social science (Johnson Citation1999) has allowed social theorists to claim knowledge about people's lived experiences and worldviews by theorising their contents as being formed through the internalisation and embodiment of wider social and cultural forces, rather than providing empirical evidence about the content and possibly oppositional character of people's private expressions. For anthropology, this might be as much a question of disciplinary authority, authorship and ventriloquism (Appadurai Citation1988) as the erroneous, but epistemologically convenient, practice of inferring people's experiences and worldviews from the surrounding social context.

Shared social contexts and seemingly congruent activities might be differentiated by diverse inner lifeworlds that remain largely uncharted by anthropology. Such is the complexity and diversity of people's inner lives that five people walking around a neighbourhood might be engaged in radically different forms of inner speech and imagery with one person trying to remember if they locked their front door while others are respectively fantasising about an actor, deciding where to go for lunch, communing with God or dealing with a major life change such as having lost their job or their spouse having been diagnosed with an illness. The extent to which these people are engaged in the same practice remains an open question, but to dismiss the empirical reality and individuality of their interior and imaginative lifeworlds is to risk only telling half the story of human life.

In response, this article attempts to research and represent the everyday experience of living with HIV/AIDS in New York's Lower East Side by examining the complex trajectories of thinking and being that are played out in urban spaces but are not necessarily externalised or made public. Here, I am specifically interested in excavating a kind of ‘deep’ memory that lives beyond the immediate surfaces and materiality of the city and is held individually and collectively by New York's citizens. This does not entail a static dichotomy of inner and outer or of the bounded person but a model of lived experience that comprises ongoing interaction and feedback (Bateson Citation1972; Clark Citation2008) that flow back and forth across the boundaries of brain, body and world to create our moment by moment sense of ourselves and surroundings. However, although such experiences are constituted and shaped through continuous interaction with the world, as noted by Michael Polanyi:

‘no one but ourselves can dwell in our body directly and know fully all its conscious operations but our consciousness can be experienced also by others to the extent to which they can dwell in the external workings of our mind from outside' (Citation1969: 220).

This suggests that while there is no independent, objective access to another person's consciousness or experience, we can use the performative and collaborative imperative of ethnography to develop practical approaches to knowing, theorising and representing the modes of inner expression, experience and memory that are fundamentally constitutive of daily life but would not otherwise be externalised or made public. This not only generates empirical and ethnographic data for investigation and analysis but also helps ensure that the debate is not conducted at levels of theoretical and discursive abstraction remote from people's lives and concerns.

The method created for New York Stories draws on the artist Jean Cocteau and the anthropologist Jean Rouch in order to understand how people's experiences of urban space are mediated by complex trajectories of thought, memory and expression. The idea of combining walking, performance and photography in urban space stretches as far back as Picasso's walking tour of Paris as staged and photographed by Jean Cocteau during the First World War on 12 August 1916, and was further developed in Rouch and Morin's film Chronicle of a Summer in the summer of Citation1960 where the new technology of synchronous sound opened up new creative possibilities for combining film, walking and narration. Rouch and Morin used a combination of participatory film practice, interviewing, life history and performance in order to construct a type of truth about their subjects that would otherwise remain dormant. During the making of Chronicle of a Summer they filmed Marceline, a young Jewish woman who was arrested during the German occupation, as she walked around Paris some 15 years after the occupation. A famous scene begins as Marceline is walking alone down Place de la Concord talking to a tape-recorder hidden in her coat and filmed from a camera mounted on a Citroen 2CV, which was pushed rather than driven so as to minimise noise and create a mobile dolly (see Henley Citation2009). Marceline walks and speaks until she reaches a deserted market building, Les Halles, where she looks up towards the roof and begins talking about the day she was deported to the concentration camp at Birkenau as a 15-year-old girl. In the same way that Camus (Citation2000) described a man on his way to the guillotine, incidentally noticing the shoe laces on his executioner's feet amidst the intensity of a moment otherwise overshadowed by death, Marceline sees the heavy iron girders in the roof of Les Halles, which remind her of the iron girders that hung overhead in the train station on the day she was deported to Birkenau. Marceline then begins to talk about the very moment at the train station when she and her father saw each other for the very last time.

Here, perception and reality of the surrounding neighbourhoods and city is not constituted in terms of what is immediately perceived by the senses but by a past that no longer exists and an imagined present whose very possibility was cut off by the contingent events of history; thereby rearticulating the ongoing tension between Western epistemology's habitual linkage of the senses and objective shared reality, vis-a-vis the invisible memories, unheard reverie and unsensed emotional biography of people's everyday lives. Marceline's experience of walking through Paris is constituted by a past that no longer exists, a present in which her farther is no longer alive and streams of memory and emotional reverie that are intertwined with the city's material surroundings, which are freely substituted in exchange for other buildings/memories, once more cautioning us against conflating environment and experience or over-determining the notion of shared social context.

More recently, Kim Nicolini, attempted to map her ‘self’ onto the streets of her native San Francisco in order to identify and explore certain fractures and moments of transformation in her personal history where her life was subject to disruption, defamiliarisation or reflection only to find that ‘mapping my life with its never ending string of melodrama, is at best an impossible task' (Citation1998: 79). With this problem in mind, New York Stories attempts to create a specific kind of ethnographic context for the production of speech, memory and imagery by establishing a new relationship between people, their bodies and their surroundings. A person is asked to walk around their local neighbourhood narrating their thoughts about their life and their past as they emerge in the present tense into a voice-recorder, while a second person interjects, asks questions and takes photographs, thereby creating a moving, performative dialogue in which transient thoughts and memories are articulated and then reflected upon in the public domain. The verbalisation of the person's thoughts and memories is carried out in the actual locations in which the original events and experiences occurred. As such the method plays upon the capacity of urban places in a person's everyday environment to elicit interior-lifeworlds and verbal testimonies, and attempts to offer a practical fieldwork approach to explore the associative properties of inner expression that emerge when moving through familiar surroundings.

The following section is an excerpt of one such staged journey I conducted around New York's Lower East Side. I asked Neil Greenberg, an HIV+ choreographer and dancer to walk round his immediate neighbourhood while narrating events from his past and present into a tape-recorder, while another informant Frank H. Jump (whom Neil did not know and also HIV+) to be the interlocutor/photographer that accompanied him. Frank (b.1960) is of the same age as Neil (b.1959) and both participants were of a generation of gay men that came of age in the brief window that existed after Stonewall but before the onset of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, and both were diagnosed HIV+ in their 20s during the mid-1980s. This meant that Frank could ask questions of Neil's life experience and memories that I could not even conceive of as a straight European without HIV. This not only created a dialogue that emerged out of Frank and Neil's embodied experiences of living with HIV but also allowed for the field and resulting ethnography to be defined in relation to issues that were relevant and important to Frank and Neil. As I was interested in capturing the historical nuances and collective deep memory of HIV/AIDS, it was important for this particular piece of fieldwork that the two central protagonists were ‘strangers’ to each other and thus were therefore required to articulate themselves without relying upon the shared, often unspoken, understandings that exist between persons who are familiar with each other's life and history. Thus while I knew both Frank and Neil independently and had worked with them over the previous months, this not only meant that they had to establish a sense of each other during the course of their journey around the neighbourhood but also meant the performative content and direction of the piece was contingent upon both parties actions, responses and certain shared life experiences.

The process was very simple and began with Neil and myself constructing a map of the neighbourhood. I asked Neil to identify a number of key events and locations drawn both from his everyday life in the neighbourhood and his history of living there. Then the idea was to walk this life biography with Frank.

I met Frank at the subway station and we then proceeded to Neil's place on E 2nd Street. When we arrived at Neil's place, Frank soon started looking at the photographs on display around the apartment to see if he knew anyone. Frank did not recognise any of the faces but after Neil mentioned their names he was not only familiar with some of their names from mutual acquaintances but also knew something of their life history and circumstances. Neil mentioned that out of the 15 photographs on display in his room, 14 were dead. However, the photographs were not actually intended to be memorials but were simply snaps of his friends that he had put up when he was younger. Neil explained that they were the type of friends he made in his late teens and early twenties that often become the close, intimate friends that someone carries throughout adult life, to which Frank, identifying with the experience, observed ‘but not since AIDS’. One by one the young faces in the photographs had died and the images became memorials, illustrating the extent to which HIV/AIDS decimated a generation of significant relationships. The manner in which memory had already started to ‘open up’ before the journey around the neighbourhood had properly begun could be described as being akin to the moment ‘before’ the text, in the way that the first lines of a play, film or novel already assume that certain actions have taken place beforehand. Only in this case it was an identification predicated upon certain commonalities in Neil and Frank's life histories. At this point I took a back role, only occasionally interrupting to ask a questions or to obtain some background information.

The excerpt begins at the point where Neil, Frank and I were trying to track down the very building where Neil might have caught HIV.

Narrating the Neighbourhood

This is Lucky Cheng's, an Asian restaurant with drag waiters. But Lucky Cheng's isn't really Lucky Cheng's. To me Lucky Cheng's still is The Club Baths a bathhouse chain that had a baths in every major city. When I first moved into my apartment I used to say I lived right between The Club Baths and St. Mark's bathhouse … which is now Kim's Video a video store I use on East 8th St. I frequented both baths a lot. At The Club Baths there was shag carpet everywhere … St. Mark's was much more cushy, stream-lined and younger guys. There was a whole thing going on … orgies, anonymous sex … and when AIDS arrived I was in a group of men who all assumed they had been put at high risk. One of these places will be the place where I caught HIV.

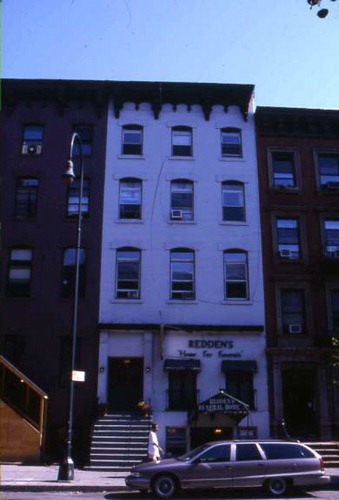

So well, here it is … my brother's apartment building, right across the street from Lucky Cheng's and just round the corner from mine and also a fifth floor walk-up. Jon was three years older than me, gay. Actually I got him the apartment, a friend of mine died there from AIDS and afterwards my brother ended up moving in. And then my brother died from AIDS. My brother actually died in the hospital but this is where he was for the couple of months before. There was a lot of vomiting, a lot of diarrhoea. He lived in apartment 25 I'm almost certain. How do you forget things like that? And his friend Risa lived across the hall. First my friend died in that apartment and then when my brother moved in, he died too. This is my path to the subway station. Very often I'll pass right by here. And I almost always glance over to see if I'm passing his building and very often I'm not. I've already passed his building by …

My brother had this weird discrepancy and probably contradiction in his own mind … he wanted a public funeral without being political. He wanted us to burn him in the street and for people to eat his flesh. His friends wanted to try and come up with a public funeral that was as close to his wishes as was possible. And the closest thing that would cover his wishes was that the body should be visible and that it should be public. The funeral started somewhere near here … it was Friday July 16th and people congregated by the park by the subway station. His body was in a van – because it is illegal to do something like this in New York. It was a non-violent political action, it was peaceful. Then four or five of us took my brother out of the van and carried the coffin up 1st Avenue

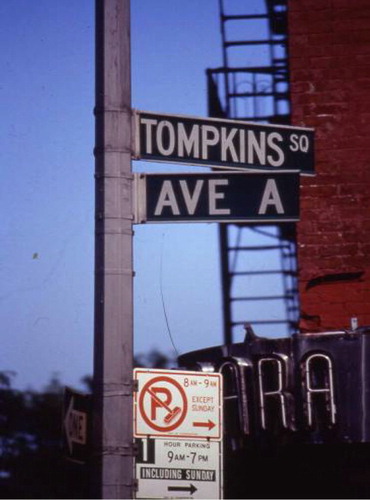

At Tompkins Square Park the coffin was set on a stand and my brother was dressed in a flowered halter top, which was chosen by his friend Risa. People sat down here and watched and we went spoke one at a time. Somebody did a Jewish prayer, and it really touched my parents that somebody would do that. Actually my brother Jon would have liked that too. People talked about him, somebody said something hyper political and somebody came up and said this wasn't a political thing. I can't walk by there without it being reminded of my brother. When I first met my current partner we went for dinner at a place on 7th street and then we took a walk and we ended up sitting in the park and it was a wild thing on our first date to be in Tompkins Square Park. And I couldn't be there with this guy on a first date without thinking that right over there was where my brother's funeral was.

Afterwards we loaded the coffin back into the van and they drove it back to the funeral hall and then it was cremated. Then what happened to the ashes is another story! We ate part of the ashes as per his wishes. It felt … I don't know what it felt like. I mean I can tell you that there were little pieces of bone left, that crunched and were the consistency of a pretzel. Which is shocking but you know, it's just ashes, there's nothing unhealthy about eating it as far as I can tell … then we went back up to Risa's and we had potato salad and we found out she had put some ashes in the potato salad. So the people who chose not to eat ashes ended up eating the ashes …

Memory, Materiality and Movement

The most meticulously detailed account of public walking and movement in New York is that of William H. Whyte who walked around New York for 16 years from the 1960s to the 1980s as part of his revolutionary ‘Street Life Project’. Whyte and his fellow researchers and students spent thousands of hours watching how people move, interact and use urban space within Manhattan, including intersections, malls, plazas and squares, and meticulously documented how pedestrians actively create their relationship to the street as they make their way around the city. Whyte noted how by mid-day, 1.2 million people, a population greater than some nations, cram into a square mile of midtown Manhattan, with pedestrians averaging up to 300 feet per minute as they walk along the 22.5-foot-wide sidewalks (Whyte Citation1980). However, in Whyte's project, as in most public urban spaces, persons encounter each other as strangers and we get to know little about the inner thoughts, existential concerns and imaginative lives of our fellow citizens as we pass on them on the street.

The short excerpts aboveFootnote1 can be seen as an attempt to establish a practical, ethnographic basis from which to understand how everyday urban surroundings are mediated by modes of internally represented experience, expression and memory that often remain beneath the surface of people's public activities. Although the resulting testimony can only offer the merest glimpse into those aspects of thinking and being that can be articulated and approximated in language, it nevertheless emerges from the embodied, empirical reality of Neil's experience of walking around his neighbourhood. Thus rather than present a speculative or abstract account of how memory and place shape people's senses of being when moving through urban space, the aim here has been to offer an ethnographically grounded, ‘experience near’ description that can be used as a basis for analysis and argument, about the relevance of inner expression (or otherwise) to anthropology. This addresses the potential of anthropology not only as a means of theorisation and documentation but also as a way of forming socially inclusive dialogues and moral collaborations with persons who are accorded an equal role in shaping the research.

Neil's testimony reveals how intense but nevertheless recurring, moments of thinking and being are generated through his everyday engagement with his surroundings. His words reveal a personal and collective history of the Lower East Side and speak of such things as loss and contingency, the politics of disease, sexual life and death, and portray an experience of the Lower East Side that many other people in the neighbourhood would recognise. At the same time, Neil's narrative about the Lower East Side describes a social and cultural history of places and buildings that remains unknown to large numbers of its inhabitants. The commonalities and discrepancies that exist between the local population's experiences and understandings of the neighbourhood expose a foundational diversity that lies at the heart of all neighbourhoods: as such, Neil's ongoing experience of the Lower East Side needs to be understood as one that co-exists alongside countless other experiences of the very same shops, restaurants, buildings and streets.

The Club Baths and the St Mark's Baths, whose emotional traces are still found in the sites now occupied by Lucky Cheng's and Kim's Video Store, were closed by Mayor David Dinkins’ administration under a city-wide public health order so as to prevent the spread of HIV/AIDS. Tellingly, a number of bath houses located in Harlem escaped the ban and remained open; an oversight or otherwise that reflects the wider political, racial and economic realities, different life expectancies and unequal exposure to risk across the USA. Likewise, HIV/AIDS does not extend equally across New York's neighbourhoods or communities, and its differential distribution is reflected upon the city's surfaces as testified to by the concentrations of adverts for antiretroviral medications, posters for HIV clinics and free HIV-related magazines, such as Poz, in certain parts of the city, such as Chelsea and the Lower East Side.

Neil and Frank are part of a generation of young men who came of age shortly before HIV/AIDS began to decimate New York's gay population. Both were diagnosed in their mid-20s during the 1980s. By 1990, AIDS patients took up 8.5% of all hospital beds and by the turn of the millennium there had been 72,207 known deaths from AIDS in New York out of 116,316 people diagnosed, including almost 10,000 infants (American Council on Science and Health). For every person diagnosed, there are tens, even hundreds of other persons who are affected, including friends, family, parents, children, neighbours, work-colleagues, counsellors and medical staff. As such these persons could also have been said to be ‘living with HIV/AIDS’ insofar as their lives became intertwined with an unpredictable and life threatening disease. The changing demographic of persons with HIV/AIDS over last 25 years has formed a polythetic population of infected and affected persons that crosses sexualities, genders, generations comprising a substantial proportion of the city's entire population. HIV/AIDS is a disease that condenses many meanings and over the years many different ideas, opinions and attitudes have become attached to it; some have been short-lived and their moment has now passed, while others have endured and some have become part of the city's consciousness. It is a diversity that is reflected on the Lower East Side's streets which combines traces of its immigrant, artistic and ghetto past with gentrification in a coeval assemblage that reinforces how a neighbourhood's material, mnemonic and emotional constitution can never be fixed or mapped insofar as places only ever come into being through the activities of its inhabitants over time.

The content and character of any given neighbourhood in a particular moment needs to be understood as incorporating the simultaneous co-presence of many different qualities of inner expression, dialogue and memory that range from the ordinary to the extraordinary and on occasion encompass both. Some of these may be recurrent and ongoing to the extent that they define a sense of personal or collective experience and understanding, while others are destined to remain inconsequential and unarticulated or even unarticulatable. This reinforces William James's notion that the spectrum of consciousness ranges from inchoate, barely graspable and transitory forms of thinking and being that exist on the periphery of our conscious and bodily awareness to those more defined, purposeful and stable forms that are more readily articulated in language and can enable persons to establish senses of self and continuity, even amidst radically changing conditions or disruption (Crapanzano Citation2004; Irving Citation2009). Although many realms of experience may remain unformed, abject and beyond the reach of language, others coalesce and become articulated into stable symbolic forms for particular purposes, including intentional, descriptive, analytical and communicative purposes, thereby forming a basis for narrative expression to oneself and others, as in the case of Neil's account to Frank and myself as we walked around the neighbourhood. While many kinds of experience can be articulated in linguistic, narrative form (Carr Citation1986; Good Citation1994; Becker Citation1997; Jackson Citation2002), it is not possible to understand people's narratives as simple representations (Berger Citation1982) unless one adopts a misplaced commitment to referential models of language and correspondence theories of truth (Quine Citation1960; Kleinman et al. Citation1997). This highlights how internally represented forms of experience and expression are subject to many of the same limits as external speech and also incorporate various expressive conventions that inhere in people's public utterances and conversations, including rhetorical statements, illocutionary speech-acts, passing observations or long-standing moral narratives about other people.

As Neil's performative recreation of his everyday experience of walking around his local neighbourhood suggests, inner speech moves between many different moods and registers of expression. This does not reveal an immutable reality but one that remains in process and can be reshaped through interior (as well as exterior) expression. People's ongoing conversations with themselves are a critical site of narrative expression and understanding that are used to negotiate life events, crisis and significant moments of disruption. Moreover, even when people's interior expressions remain publicly unarticulated, their imagined audience often extends beyond the person, for example, to friends, family and specific persons in one's social life, as well as to distantly imagined and unknown others, or symbolic and religious figures (see Bakhtin Citation1986; Davies Citation2006; Irving Citation2010).

Once social life is understood as being constituted by different forms internally represented speech, emotional reverie and expression, then is necessary to attend to the specificity of those expressions and the ways in which shared social environments are on occasion radically differentiated (Irving Citation2010). Nowhere is this more obvious than when Neil walks to the subway station on First Avenue and Houston. To do so he must walk past Lucky Cheng's, where he most likely caught HIV, as well his dead brother's old apartment building across the road: an act that far more often than not brings forth the deep memory of the past. The other people Neil passes in the street have no idea that the person walking by them might be conjuring up the graphic image of nursing his dying brother or contemplating his own HIV infection, for despite these being intensely experienced in his being and body the traces of these events mostly remain unseen and ambiguous in terms Neil's public appearance (see Rosen Citation1996).

On some days Neil inadvertently forgets about his brother's death (not to overlook his friend John Vasquez who also died in the same building) and afterwards feels guilty. On other days he does not want to engage with the emotional intensity of walking down First Avenue and will take the long way round the block or use another subway station further away, thereby avoiding both Lucky Cheng's and his brother's old apartment. However, such acts of taking the ‘long way round’ elicit a different type of emotion, which for Neil suggests denial and a lack of respect and as such he mostly chooses the direct way, both to remember and acknowledge his brother but also as a kind of daily existential test of his moral fortitude. This shows how even the simple act of turning right or left when leaving his apartment building presents multiple possibilities for engaging with and shaping the past, present and future. A person's daily movements through the neighbourhood open up many different emotional contexts for remembering, forgetting and experiencing, insofar as certain streets and buildings have the capacity to elicit depths of personal experience and memory, while other streets are much less defined in relation to the past and offer the possibility of deadening the past or at least making the neighbourhood less emotionally active.

The types of emotion, mood and memory that are brought to life through a person's movements helps shape the empirical content and character of their lived experience and establishes different possibilities of being and expression. Consequently, by deciding to walk down one street rather than another, by staying inside or choosing to go out, by going to friend's house or public park, Neil not only creates his experience of the neighbourhood but his life with HIV/AIDS as well. The modes of thinking and being, for example, that are generated by walking down First Avenue past Lucky Cheng's or by visiting Tompkins Square Park, demonstrate what is at stake by in people's everyday movements and how different places have the capacity to generate realms of experience, emotion and mood that are qualitatively different from being elsewhere. Although Neil's account of walking around his local neighbourhood reveals the impossibility of removing oneself entirely from the emotional and mnemonic power of certain places, it also demonstrates how people's lived experiences of the moment are creatively defined through everyday movements on an ongoing basis and how these help establish a person's sense of being-in-the-world.

Memory is formed through repetition but it is also inherently unstable right down the proteins and molecules in the brain, meaning that even long-term, repetitively embodied memories, enter a labile state every time they are retrieved before being re-patterned back into the brain (Rose Citation2003). Moreover as both the process of retrieval and re-patterning take place in relation to the specific emotional context of the moment (Nader Citation2003), it means that each time Neil walks by his brother Jon's old apartment, he is not only maintaining a complex set of memories, feelings and associations about his brother's life and death, but also that these are subtly transformed in each and every act of recollection. At the moment of recollection, memory enters a indeterminate state in which past events and episodes are intertwined with a person's current mode of being be that happiness, sadness, boredom or more accurately a complex assemblage of emotions that are indivisibly experienced and which while linguistically and analytically separable are experienced simultaneously at the level of one's body. This means that every occasion of walking past Jon and John's apartment has the potential to refashion or add a new quality of experience to the past which is then incorporated into being and body. For Neil this includes, most tragically, the development of effective triple combination antiretroviral medications shortly after John Vasquez and Jon Greenberg died that would have had a good chance at keeping them alive. Thus while antiretrovirals have stabilised Neil's health so that he no longer walks past the apartment thinking about his own impending death, his memories of John and Jon are now intimately intertwined with the knowledge that had they lived a couple of years longer they might still be alive today.

Beyond such modes of individual memory and cognition, there are also various shared forms of memory that define people's collective experience and understanding of the neighbourhood. Jon's public funeral is now part of the Lower East Side's local folklore and continues to shape the social landscape. This is not restricted to people who witnessed it in that I have met a number of people living in the neighbourhood who still ‘remember’ Jon's funeral even though they have never met him and did not observe the funeral. ‘Oh yeah’ one informant who lives on E14th St told me ‘I know Jon Greenberg. He had that public funeral that blocked off the whole of First Avenue and speeches were read out’; while another informant, who lives only a few yards from Jon's apartment but did not know him, said that once he heard about Jon's dead body being publicly paraded along First Avenue he realised that people continue to have a political responsibility even in death and made a decision to politically choreograph his own funeral if he felt it necessary. As such Jon Greenberg maintains a kind of presence in the neighbourhood's collective memory, including among people who never knew him but heard about somebody whose corpse was carried along First Avenue. In establishing a type of being-in-abstentia (see Sartre Citation1996) that extends beyond those that knew him, Jon is now part of Lower East Side's social, political and emotional fabric.

Ending

By responding to Kant's notion of anthropology as being focused upon a pragmatic understanding of the relationship between the interiority and exteriority of the person, this piece attempts to think ethnographically about those realms of thinking and being that mediate the experience of urban space, as articulated in public against the backdrop of the actual places where the original events took place. The thoughts, emotions and expressions that emerge as Neil and Frank journey around the Lower East Side are social, historical and political and speak of the night-time that descended upon New York City during the 1980s and 1990s when AIDS exposed many thousands of people – both gay and straight – to death and cut across the dominant cultural narrative of life as something that extends out into old age. The strange discrepancy of healthy, young people succumbing in large numbers to disease and death, in relation to an overall population steadily getting older, reversed the established order of life. Since then HIV/AIDS has continued to occupy a place in many New Yorkers’ imaginations and has transformed the social lives and sexual practices of many of its inhabitants.

Many of Neil's friends and contemporaries died during New York's ‘night-time’. Neil salvaged some meaning from their deaths by using their life stories as an inspiration for an extraordinary dance he choreographed called ‘Not About AIDS’, which takes the form of a diary that chronicles all the losses he experienced in 1993, the year that his brother died. Although seemingly about AIDS, Neil entitled it ‘Not About AIDS’ insofar as it is about the existential dilemma of life and death that all humans face, and as such its success lies with its ability to communicate beyond the specifics of AIDS to a broad audience. Interestingly, when I pressed Neil to describe this work as a politically motivated piece, he insisted that it was not and instead described it as an ‘ontological protest’. One of the most powerful scenes in the dance is when Neil tries to recreate his brother's facial expression at the moment of his death: but of course having already revealed to the audience that he himself has AIDS is asking the audience to imagine his own impending death.

Things did not turn out that way because, two years later, the arrival of effective antiretroviral medications transformed the experience of HIV/AIDS and re-opened time and space for thousands and thousands of New York men and women living with HIV/AIDS, triggering a massive shift of mind, body and emotion in the city, among many thousands of people, away from death and back towards life. People like Neil and FrankFootnote2 have had to learn how to ‘live’ again, however many found it impossible to return to their previous lives and having prepared for death living with the type of knowledge that emerges in the face of mortality and bodily instability, including the consequences of irreversible decisions that were made at the time, and are now working towards forging a future.

Timetable

Narrating the Neighbourhood took place on 25 July 1999 – six years after Jon Greenberg's death on 12 July 1993 and public funeral on 16 July 1993 – and was re-narrated with Neil in 2011.

Acknowledgements

My sincerest thanks go to Neil, Frank, the Wenner Gren Foundation and the Economic and Social Research Council of the UK (RES-000-22-4657) without whom neither the original research nor the subsequent writing of this paper would have been possible. Thank you also to Nelson Santos, Amy Sadao, Barbara Hunt at Visual Aids for their outstanding cooperation, work and support over the years.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

† Dedication: The paper is dedicated to Jon Greenberg, John Vasquez and Frank Myer.

1. As Neil and Frank's journey around took a whole afternoon, and generated over an hour of recorded narrative and many images, it has only been possible to present a short excerpt as an illustration of how forms of internally represented expression and deep memory – that are at once biographical and cultural – shape people's experience and understanding of New York's Lower East Side.

2. Neil is now a Professor of Dance at the New School in New York. Frank is now a published author (see Frank Jump: Fading Ads of New York, 2011; History Press) who teaches at his local elementary school.

References

- Appadurai, Arjun. 1988. Introduction: Place and Voice in Anthropological Theory. Cultural Anthropology, 3(1):16–20. doi: 10.1525/can.1988.3.1.02a00020

- Bakhtin, Mikhail. 1986. Speech Genres and Other Late Essays (Vern W. McGee, Trans.). Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

- Bateson, Gregory. 1972. Steps to an Ecology of Mind: Collected Essays in Anthropology, Psychiatry, Evolution, and Epistemology. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Becker, Gaye. 1997. Disrupted Lives: How People Create Meaning in a Chaotic World. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Berger, John. 1982. Another Way of Telling. New York: Pantheon.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1990. In Other Words: Essays Toward a Reflexive Sociology. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Camus, Albert. 2000. The Myth of Sisyphus. London: Penguin Classics.

- Carr, David. 1986. Time, Narrative and History. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Clark, Andy. 2008. Supersizing the Mind: Embodiment, Action and Cognitive Extension. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Crapanzano, Vincent. 2004. Imaginative Horizons: An Essay in Literary-Philosophical Anthropology. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Csordas, Thomas. 1997. The Sacred Self: A Cultural Phenomenology of Charismatic Healing. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Davies, Douglas. 2006. Inner-Speech and Religious Traditions. In Theorizing Religion, edited by James Beckford & John Wallis. pp. 211–223. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Davis, Christopher. 2000. Death in Abeyance. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Evans-Pritchard, Edward. 1969. The Nuer. Oxford: Clarendon.

- Geertz, Clifford. 1973. The Interpretation of Cultures. New York: Basic Books.

- Good, Byron. 1994. Medicine, Rationality and Experience: An Anthropological Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Henley, Paul. 2009. The Adventure of the Real. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Hogan, Susan & Sarah Pink. 2010. Routes to Interiorities: Art Therapy and Knowing in Anthropology. Visual Anthropology, 23(2):158–174. doi: 10.1080/08949460903475625

- Ingold, Tim. 1992. Editorial. Man, NS, 27(4):693–696.

- Irving, Andrew. 2007. Ethnography, Art and Death. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute (n.s.), 13:185–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9655.2007.00420.x

- Irving, Andrew. 2009. The Color of Pain. Public Culture, 21(2):293–319. doi: 10.1215/08992363-2008-030

- Irving, Andrew. 2010. Dangerous Substances and Visible Evidence: Tears, Blood, Alcohol, Pills. Visual Studies, 25(1):24–35. doi: 10.1080/14725861003606753

- Irving, Andrew. 2011. Strange Distance: Towards an Anthropology of Interior Dialogue. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 25(1):22–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1548-1387.2010.01133.x

- Irving, Andrew. 2013. Bridges: A New Sense of Scale. The Senses and Society, 8(3):290–313. doi: 10.2752/174589313X13712175020514

- Irving, Andrew. forthcoming. Random Manhattan: Thinking and Moving Beyond Text. In Beyond Text: Critical Practices and Sensory Anthropology, edited by Rupert Cox, Andrew Irving & Christopher Wright. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Jackson, Michael. 2002. The Politics of Storytelling: Violence, Transgression, and Intersubjectivity. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum.

- Johnson, Galen. 1999. Inside and Outside: Ontological Considerations. In Merleau-Ponty, Interiority and Exteriority, Psychic Life and the World, edited by Dorothea Olkowski & James Morley. pp. 25–35. New York: SUNY Press.

- Kant, Immanuel. 2006. Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View. Cambridge: University of Cambridge Press.

- Kleinman, Arthur, Veena Das & Margaret Lock (eds.). 1997. Social Suffering. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Nader, Karim. 2003. Neuroscience: Re-recording Human Memories. Nature, 425(9 October):571–572. doi: 10.1038/425571a

- Nicolini, Kim. 1998. The Streets of San Francisco: A Personal Geography. In Bad Subjects: Political Education for Everyday Life, edited by Bad Subjects Production Team. pp. 78–83. New York: New York University Press.

- Polanyi, Michael. 1969. Knowing and Being. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Quine, Willard. 1960. Word and Object. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Rose, Steven. 2003. The Making of Memory: From Molecules to Mind. London: Vintage.

- Rosen, Laurence (ed.). 1996. Other Intentions: Cultural Contexts and the Attribution of Inner States. Santa Fe, NM: School of American Research Press.

- Rouch, Jean & Edgar Morin (directors). 1960. Chronicle of a Summer (Film).

- Sartre, Jean-Paul. 1996. Being and Nothingness (H. E. Barnes, Trans.). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Whyte, William, H. 1980. The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces. New York: Project for Public Spaces, Inc.