ABSTRACT

When South Africa’s credit/debt landscape expanded during the 1990s, this was justified by some as a new form of inclusion but alleged by others to have intensified the power and profit of capitalism and acted to the detriment of householders, thus perpetuating ‘credit apartheid’. Yet, blame cannot be so easily assigned. Forces of state and market have intertwined to create a redistributive neoliberalism, enabling brokers – who have played a key role in establishing the current credit/debt landscape – to insert themselves into the interstices of the system, making money by adding interest at every point in the value chain. Apartheid’s spatial separations meant that traders – and later informal moneylenders – relied on agents to bridge the gap between themselves and the rural/township world of economic informality. Even attempts at credit reform have been complicated, and stalled, by the ongoing presence of intermediaries. The paper explores these dynamics, illustrating how difficult it is to separate bad from good protagonists or perpetrators from victims.

Introduction

Scholars critical of new techniques and discourses of development, through which the poor and marginal have been included through ‘bottom of the pyramid’ (BoP) techniques, and through which ‘everyday life’ has been financialised (Martin Citation2002; Langley Citation2008; Krige Citation2014), maintain that these techniques obscure new forms of exploitation. They point to the ‘regressive social and distributional effects’ of attempting to incorporate informality and of drawing on the labour resources of the informal economy’ to benefit the formal one (Meagher Citation2013; see also Dolan Citation2013). The effects go beyond mere exploitation. Elyachar writes of how loans made to Egyptian youths induced aspirations for market-oriented trade, yet brought disappointment as promised forms of citizenship and inclusion failed to deliver (Elyachar Citation2005). In similarly insidious vein, new credit-based development regimes in Bangladesh reconfigured ‘wages’ or ‘grants’ as ‘loans’ and made newly recruited NGO agents ‘repay’ rather than designating them as ‘earners’ (Huang Citation2015). Financialisation, seen as ‘highly detrimental to significant numbers of people around the globe’ (Epstein Citation2005: 5), seems even more sinister in these newer incarnations; it is driving vulnerable people with few other livelihood options to help capitalists fleece other, equally poor, people. Newly configured intermediaries, in the process of creating novel spaces in which their own advantage may be sought, are simultaneously acting to disenfranchise – and undermine the opportunities of – others.

This paper, set in South Africa, investigates three cases in which such intermediaries operate. It explores some of the dynamics through which indebtedness, building on or reacting to earlier exclusionary ‘credit apartheid’ regimes, has intensified; and examines the limits to planned reforms aimed at addressing the debt problem in both its original and its later incarnations. It shows how accounts critical of new forms of financial inclusion, while pertinent to some degree, also have some limitations. First, they overestimate the novelty of these credit regimes and the extent to which they are linked to post-1980s economic liberalisation. Second, they often focus primarily on people in poorer and more marginalised settings (Elyachar Citation2005; Han Citation2012) rather than exploring those in the ‘new middle classes’ who have their roots in such settings but for whom credit has been seen as furnishing the means to transcend them. Third, they seem to imply that, if reform was undertaken, it might be possible once again to return to a simpler world. In such a world, capitalists might be more visibly counterposed against those who are exploited by them (as labourers or consumers); and development planners might be more readily challenged by those who are subjected to their inappropriate interventions. This starker opposition might then more easily enable resistance. Countering such assumptions, the paper illustrates the deep-seated nature of the role played by brokers in assembling the diverse components of financial assemblages, bringing those at the BoP into inevitable complicity with its workings.

Relating to the first of these limitations: the cases presented here show how small-scale entrepreneurs and intermediaries have long been able to take advantage of opportunities arising because of the racial/spatial disconnections of apartheid. Countering the critical tone of accounts of the new financial inclusion, it is noteworthy that the role of these small-scale agents – often viewed as a sign of the sudden recent breakdown of law and order – might rather be seen as deeply entrenched, constitutive of, and helping to reproduce a particular social order with a longue durée. From a period even before the race-based separation of the population into spatially separate territories or homelands, there was extensive reliance by traders, commercial operators and the like on agents who bridged the gap between the world of business and the township world of economic informality. These agents were often difficult to classify since, chameleon-like, they assumed the features of those employing them or those to whom they were representing their employers. Such people then started setting up on their own, acting less as intermediaries and more as informal entrepreneurs in their own right, to purvey a range of goods to others from similar backgrounds and always relying on credit to do so. They acquired agents in turn who drew yet further groups of clients into their ambit – and so these arrangements acquired a self-perpetuating character. When attempts were later made to regulate ‘credit apartheid’, such agents adapted their operations, enabling them to exist in parallel with new regimes. Relating to the second limitation, accounts critical of the new financial inclusion are more attentive to the plight of poor borrowers than to that of those who are upwardly mobile or ‘middle class’: this paper addresses the latter situation in particular. But what of the third limitation – the possibility of restoring a world in which the battle lines are more clearly drawn? The cases presented here illustrate that it is ‘difficult to distinguish between victims and accomplices’ (Gambetta Citation1988: 170), since many who lend money borrow it as well; borrowers are also lenders.

‘Mediating’ or ‘brokering’ has ambivalent connotations (Lindquist Citation2015): it can be construed as positive (producing peaceful outcomes to difficult confrontations) or negative (suggesting operators who insert themselves between diverse parties so as to gain opportunistically). In classic studies of broker-style relationships, the latter valence has predominated. Clients, it is argued, abandon their potentially open access to the state and/or major markets in order to gain the benefits of going through an intermediary (Eisenstadt & Roniger Citation1980; Randeraad Citation1998; James Citation2011; Lindquist Citation2015). In doing so, such clients are often unaware that a direct connection to, and trust in, state officials or businessmen might be possible; their recognition of such a possibility would likely put such intermediaries out of business (Gambetta Citation1988: 172). Indeed, those who seek to combat the dependency inherent in intermediation have been inspired by just such a vision: that of re-establishing, or newly establishing, open access and public trust. Doing so would restrict the ability of brokersFootnote1 to reproduce the circumstances which enable them to continue operating. However, the actions of such brokers are rarely prompted by a wish for profit or power alone. Their creative ability to respond to situations of inequality and/or social disruption often involves the weaving together of diverse threads to construct a plausible story which they tell those who depend upon them – and indeed themselves – about the morality of their own motivations (Piliavsky Citation2014). Although much of the writing on intermediaries, like Arce and Long’s classic paper (Citation1993), has been concerned with scenarios of political legitimacy, in which small-time leaders or low-level civil servants seek support among those unable to act on their own, I have argued elsewhere that the role of entrepreneurs (James Citation2011) – and, I would now add, of financial agents and intermediaries – is equally usefully considered in economic settings, or those where the boundaries between state and market, the political and the economic, are increasingly difficult to determine. This paper shows how a proliferation of agents have taken up their roles in the credit/debt machinery, becoming its essential components.

To characterise matters in this way might sound deterministic, but there are many sources of variation and flux. Worldwide, there is the notoriously unpredictable character of the global financial system; locally there are elements that might be analysed as capitalist and commodified in character (using a more Marxist perspective) and others involving local solidarity-based or reciprocal forms of exchange (using a more Maussian one). Brokers strive to bring these two sets of elements, and their associated modalities of payment or exchange, into the same frame. Their efforts interweave the formal world of capitalist values with an informal one made of household-based connections and small-scale relationships which are more reciprocal in character.

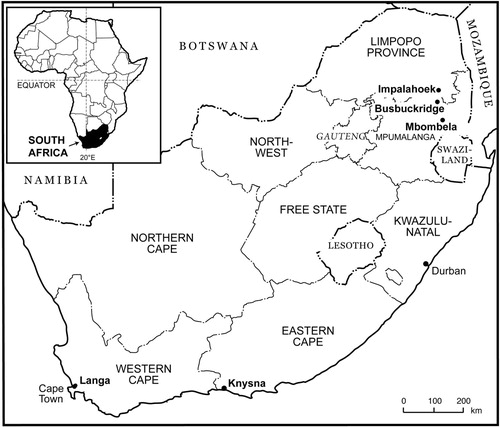

Following a short context-setting section which discusses features of South Africa’s new lending, the paper presents three instances. These are drawn from ethnographic fieldwork conducted between 2008 and 2010, well as from ethnographically informed readings (see Comaroff & Comaroff Citation1992) of parliamentary submissions and sources such as memoirs, novels and journalistic accounts. The nature of the topic called for multi-sited rather than single-location fieldwork. To understand how the alleged abolition of ‘credit apartheid’ affected its former victims, participant observation and interviews were conducted both in settings where it had prevailed – in spaces originally sequestered from white cities and farmlands by apartheid’s social engineering, such as the low- to middle-income neighbourhood of Sunview in Soweto, and Impalahoek village in Mpumalanga – as well as in newly integrated post-apartheid settings in larger urban centres such as Knysna and Pretoria (see ). Informants included medium to well-paid employees of the government as well as low- to middle-income earners. Attentive to policy issues and the pronouncements of agents in the state, the corporate sector, and the world of human rights and NGOs, I interviewed employees in the banking sector, registered micro-lenders, some community lenders (mashonisas), and the debt counsellors who seek to regulate, curb or counter their activities.

Each case illustrates the role played by intermediaries in South Africa’s particular version of financialised indebtedness at a different point in time. The first outlines how agents who work for furniture and appliance retailers act as brokers who assemble formality and social embeddedness. The second gives an account of illegal moneylending – the context where one might most expect a version of informal entrepreneurialism – which took its use of agents from the furniture trade. The third discusses state attempts to cut out these small-scale agents, analysing contestations over the attempted regulation of creditors’ ‘reckless lending’.

Context – The New Lending

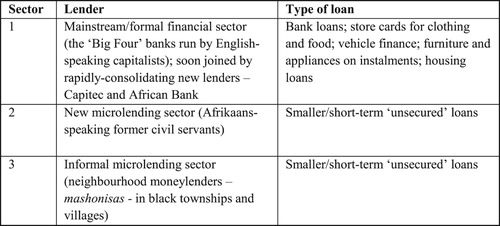

South Africa saw rising levels of consumer indebtedness from the 1990s onwards, especially among those people who are – or seek to be – upwardly mobile. The situation is not unique: similar levels of personal indebtedness, often twinned with aspiration, are evident worldwide. In this setting, however, the phenomenon took on a specific character, arising as it did at the moment of democratic transition in 1994. The move away from – and the concerted attempt to abolish – credit apartheid, combined with the progressive liberalisation and financialisation of the economy, a massive rise in expectations for personal material wealth and all that it can provide, and the sudden availability of short-term loans at high rates of interest (offered by moneylenders both registered and unregistered) meant that a huge demand was met by a burgeoning supply. My interviews revealed a startlingly racialised credit/debt landscape, schematically represented in . White, Afrikaans-speaking civil servants were steadily ousted and their places taken by black members of the electorate. Flush with cash from their redundancies and emboldened by the repeal of the Usury Act that for many decades had capped the interest rate and that had been now abolished in the interests of extending credit to all, many of these ousted civil servants established ‘micro-lending’ businesses (sector 2 in ), charging high interest rates (Roth Citation2004: 41–5).Footnote2 In an ironic twist, this enabled these former civil servants to continue drawing parts of the salaries of those who had now replaced them, as well as the social grants of those lower down the scale. Replacing the fixed assets that lenders traditionally require by way of security (Roth Citation2004: 62), these payments from the state came to serve as collateral for what are misleadingly known as ‘unsecured’ loans (see Anders Citation2009 for similar cases in Malawi; Parry Citation2012 for India). The new civil servants and grant recipients in turn, despite receiving regular payments, needed more than what those could buy. The only option was to ‘borrow speculative resources [from the] future and transform them into concrete resources to be used in the present’ (Peebles Citation2010: 226). Lenders, having direct access to the bank accounts into which the salaries of this new swath of civil servants (or the grants of welfare recipients) were paid, were easily able to recoup their debts. Some, in sector 2, made liberal use of garnishee or emoluments attachment orders, as described below. Others used the system – only outlawed at the end of the 1990s, and hence no longer used by creditors in sector 2, but still widespread in sector 3 – of confiscating a debtor’s ATM card and identity document in order to ensure repayment (see Breckenridge 2005, 2010 for a similar practice in India, see Parry Citation2012). All-in-all, this precipitous transition opened up new gaps which intermediaries were able to bridge, by matching creditors who had never previously lent money with debtors who had not formerly borrowed it to the same degree.

Possible sources of credit have thus proliferated since the end of apartheid. A consumer is able to borrow from many banks, use many credit cards, buy a car with finance and furniture on hire purchase (HP), and hold store cards from an array of retailers, as well as having access to micro-loans, both formal (legal) and informal (illegal). Often, consumers, having been able to take out loans with very few checks being made on their income or creditworthiness, borrow from one source in order to repay another: a practice that has not noticeably reduced despite attempts at state regulation (James Citation2015a: 85, 157).

The precipitous onset of borrowing and lending possibilities that were unleashed by these neatly intersecting forces resulted, however, not in a classic free-market situation, but in a mediated form of capitalism – one partly modelled on its earlier precedents. Forces of state and market intertwine. Intermediaries, their patrons and their clients, using free-market style savvy, divert state resources such as civil servant salaries and welfare grants or use these as security in their lending operations, thus enabling them to make ‘money from nothing’ (James Citation2015a) in a redistributive version of neoliberalism.Footnote3 Put differently, ‘neoliberal means … ensure the ever wider spread of redistribution’ (James Citation2012: 37).

Assembling Credit Scams in the Furniture Retail Trade

In South Africa, during the twentieth century, where increasingly draconian racial separation created captive markets and where loans from the mainstream financial sector were mostly unavailable to black people, a system evolved of selling them furniture and appliances on HP. Agents, mostly drawn from black township settings themselves, helped facilitate such sales. (Brokers more generally have often been ‘drawn into new forms of translocal relations’ (Lindquist Citation2015).) Cash-strapped consumers sometimes bought (and buy) more than they can afford, and are regularly sent reminders to repay outstanding debts, failing which their wages may be attached or their goods repossessed. Not all, however, are as passive in the face of the powerful furniture industry as might be supposed. My interviews revealed how many have used the fact of being contracted to pay retailers on instalment to enhance, rather than contradict, frugality, by carefully paying off each item in its turn while selectively avoiding relatives’ requests for money. In cases of default, furniture-store agents sometimes opportunistically exploit the spatial and social gap between (white) retailer and (black) buyer. But they have also found – and helped customers to find – room for manoeuvre in the fact that, when goods are bought on instalment, time elapses between present possession and future payment. The concept of ‘trust’ – often implicitly denying the inherent mistrust that would otherwise be inevitable (Gambetta Citation1988; Shipton Citation2007) – is elaborated as a moral discourse by both the corporate interests that expect timely repayment and the wily salesmen that help customers to evade this, or pocket proceeds for themselves. The business, all in all, is characterised by a mixture of racist paternalism, sharp practice, and intimacy.

Such sales practices are of long standing, especially amongst the early-urbanising black middle class. ‘On all sides’, observed American social worker Ray Phillips in Johannesburg in the 1930s, ‘one is informed that the “hire-purchase” system of acquiring pianos and furniture is responsible for much of the indebtedness of the Africans’. Furniture dealers routinely sold items to customers, on instalments, without checking their ability to repay; the inevitable result was that the latter, after paying some accounts would be ‘unable to make ends meet. He goes to another shop where he contracts another debt and so on continually’ (Phillips Citation1938: 41). Those ‘to whom money is owing and to whom promises have been made’, would be paid as long as they arrived before other creditors: ‘the rest are put off with various promises until a later time’ (Phillips Citation1938: 40). The embedding of similar practices in more recent times has been documented by Miriam Tlali in her novel Muriel at Metropolitan (Citation1988), which talks of the moral dilemmas faced by a black employee in a furniture business, and journalist David Cohen in his book People who have stolen from me (Citation2004).

Some 80 years later, black people continue to rely on the furniture retail sector for credit: something that must be understood in its broader context. Their century-long exclusion from land ownership, and limited possession of movable property, meant that other sources of collateral were sought: the repossession of furniture became routine. Credit was offered on unfavourable terms, via a ‘dysfunctional market’ (DTI Citation2004: 22). Interest rates are high (Schreiner et al. Citation1997), and added ‘charges’ for credit insurance inflate them still further (DTI Citation2002, see Gregory Citation2012). Impalahoek school teacher Muzila Nkosi told me ‘you’ll pay R15,000 for something that only costs R5,000’. Having suffered the ignominies of this system when a furniture store placed a garnishee order on his bank account – at significant cost – for allegedly missing a monthly repayment, he and his co-teachers started a savings club, Thiakene Machaka (build yourselves, relatives). ‘I wanted to prevent members from buying goods on credit’, he said.Footnote4 These high costs, according to retailers, helped compensate for frequent defaults or pay the costs of repossessions, making up for their exposure to financial risk given the financial insecurity, and/or occasional resistance to making these payments, of their targeted buyers. Many householders I spoke to, despite their exploitation via this form of ‘credit apartheid’, have doggedly kept up their repayments and waited to buy the next item only once the previously purchased one had been paid off. Often buying household items as part of a trousseau on the occasion of a daughter’s marriage, their participation in this market arose within a ritualisation of the life-course, and exposed them to gradually increasing expenditure, and expanding credit access, over time.

Although the business is characterised by great formality, with meticulous record keeping and regular mailing out of invoices in brown envelopes to remind purchasers of what they owe, it also involves personalised relationships and ‘trust’: especially between the retailer and his agents who hail from the neighbourhoods in which sales were being made and on whom that retailer relies to facilitate the steady payment of instalments or repossess items in cases of default (Cohen Citation2004: 63). But the commission-based character of agents’ work, combined with the perceived unfairness of the terms offered to clients, meant that ‘scams’ became common. Both employees and agents conspired or entered into complicity with such clients (Cohen Citation2004: 42–6) or were tempted to do so (Tlali Citation1979: 82–3). These, from the agents’ point of view, made up for employers’ alleged meanness by enabling them to top up their meagre salaries (Tlali Citation1979: 151–2). In one case, agents set off into the township on a hazardous quest to repossess an electric cooker, only to find that it had been sold on. After driving still further into a more remote township area, they ran out of petrol and were unable to make the return trip since their employer refused to cover the cost of their fuel (Cohen Citation2004: 58–61). When agents colluded with customers in such situations, it was not only to enhance their earnings but also to compensate them for the negative way they were viewed by fellow members of the black community for being complicit in ‘squeezing money out of [clients] to swell the coffers of their white bosses’ (Tlali Citation1979: 82–3). From the customers’ perspective, these ‘scams’ made it possible, at least temporarily, to escape the terms laid down and interest rates charged by the furniture outlets. Relying on such intermediaries gave the business a personalised character despite its reliance on documentation, written records and the like (Tlali Citation1979: 58).

In Impalahoek, agent/customer collusion was common. Ace Ubisi described a typical situation, involving a well-known store, Ellerines, which has a branch in a nearby plaza. Repossession agents visit an errant client, explaining that the furniture is soon to be confiscated. The client agrees that he has defaulted, but pleads for some more time to pay. Attempting to avoid having furniture carted out of the house, the client pays the agent a bribe to return to his employers and say ‘there is no-one in the house’. If, however, the defaulting client is unwilling or unable to pay a bribe, the agent embarks on another scam. Repossessing the furniture, he sells it to another client, who is unaware that the agent, acting on his own, has now become the seller. Pocketing the difference between the original amount owed and what he gleaned from the new sale, he paid it at Ellerines ‘as if it was the original owner of the furniture who was paying’. Store owners and managers found themselves in a sort of arms race as they attempted to outwit their agents (see Cohen Citation2004: 149), and customers could be disadvantaged in the process. The crooked agent mentioned in the story above, for example, was exposed and fired, but continued to travel around to prospective buyers, benefiting from villagers’ ignorance of his dismissal, requesting deposits and offering reassurance that the items would soon be delivered. When the furniture failed to arrive, he was forced to leave town once outraged villagers discovered the trickery.Footnote5

Overall, then, these brokers assemble elements of business acumen and formal record-keeping formality with elements of social embeddedness and community-mindedness. The personalised relationships they construct with customers are relied on by the retailers who employ them: it makes up for these customers lack of a more generalised trust in the broader credit system overall (see Gambetta Citation1988). Meanwhile the reliance on agents, and the forms of collusion-but-dissembling which they practice, has spread into other realms.

Loansharks and Their Intermediaries

Blurred boundaries exist between informal moneylending (sector 3, ) and its recently regularised and regulated counterpart, ‘micro-lending’ (sector 2), with borrowers frequently confusing the two and using the same term – mashonisa – to describe them both. Both increased during the 1990s (Siyongwana Citation2004), though the rate of the unregistered variety is more difficult to track than its registered counterpart. There were estimated to be 30,000 such moneylenders in operation in 2004 (Ardington et al. Citation2004: 619), but such figures obscure the fact that those in sector 3 include both salaried civil servants and social grant recipients (and indeed many other kinds of employees) who lend money alongside their other forms of livelihood; and also that many rotating credit savings clubs also lend out money at interest (Bahre Citation2007; James Citation2015b) while its members also borrow from other sources. Borrowers and lenders, or ‘victims’ and ‘accomplices’ (Gambetta Citation1988: 170), thus cannot be easily distinguished. Moneylenders, operating beyond the system and aware of the illegality of their activities, nonetheless aim at greater economic formality themselves. Ironically, policy-makers’ attempts to ‘bank the unbanked’ were here at odds with state regulation of illegal moneylending. A teacher of financial literacy told me that she was often approached by mashonisas for advice on how to bank their own proceeds and securely store the proceeds of their enterprise without their illicit activities becoming visible to the authorities.Footnote6

Were such lenders purposefully preventing their clients from getting open access to the market (Eisenstadt & Roniger Citation1980; Gambetta Citation1988)? Initially at least, these lenders’ businesses arose as a result of black householders’ inability to access credit from the formal sector except by buying furniture on instalment, inclining them instead towards community lenders who often offered more reasonable terms in any case (Roth Citation2004: 52). These lenders often had a personal connection to borrowers, whose requests for loans were, in many cases, why these lenders started doing business in the first place (Krige Citation2011). This community embeddedness effectively caps the interest rate, with lenders often extending the loan past month-end without calculating an accompanying escalation. To insist on full repayment would make repayment difficult, give the lender a reputation for unfairness, increase the chances that violence be used against him/her, and prompt complaints to the authorities (Krige Citation2011: 154–8). Some lend only small amounts (less than R300), must adjust their collection arrangements to fit in with local norms (charging 15% interest monthly, being flexible in calculating interest over time, lacking formal collateral).Footnote7 Since ‘the termination of future contracts’ by neighbours acts to regulate such moneylending (Roth Citation2004: 99), the local mashonisa does not necessarily resemble the unscrupulous baseball bat-wielding loan shark of literary accounts, since his desire to stay in business controls the terms under which he seeks repayment.

It is in the case of bigger moneylenders, who typically charge 50% interest monthly, and many of whom similarly combine this income source with others, that the employing of agents and intermediaries has taken hold, showing strong similarities to what happens in the HP furniture business. Solomon Mahlaba told me that moneylending in and around the village of Impalahoek was initiated by a white farmer, Jaap Fourie, in the late 1980s. Some of Solomon’s nieces, who worked on Jaap Fourie’s farm, approached their employer via the farm foreman or induna to give them an advance on their meagre wages. The induna advised the farmer that he could make money by charging interest at the rate of 20% per month: a practice already well known in the townships. Unbeknown to the farmer, he then inserted himself as a broker or agent, charging R30 for the service. Encompassing this commission, the rate of interest went up to 50% per month, which is where it remains for larger moneylenders nationwide. The induna, Nkuna, started using the proceeds to lend money in his own right, eventually enabling him to leave behind his farm job altogether. He became the pre-eminent moneylender in the area.Footnote8

When Nkuna became a moneylender, he acquired a new agent who set up independently. Mathebula, an air force employee, needed to pay for a family funeral and was given a loan by Nkuna – of R15,000. Later needing a further loan, he went to another mashonisa, who lent him R10,000 and confiscated his card. From 1999 until 2005 ‘he was working for mashonisa … After 2005 he went to the very same mashonisa. He was looking for a part-time job … . He said ‘people know that I’m a regular customer, they know that I was owing you a lot of money. … I will bring in some of your money and I will do the job’. His claim that, having the trust of community members, he would be in a good position to follow-up unpaid loans using trust rather than more violent means, persuaded Nkuna. But his new agent, Mathebula, started generating extra profit using his knowledge of the differentiated timing of government salary payments.

… this guy will lend to teachers who are paid on the 22nd and his colleagues will be paid on the 15th. All the hospitals, air force, soldiers are paid on the 15th. So he will lend money from the 1st up to the 15th. So those who are getting paid on the 15th, they will give it to him. He will take the money as well and lend to the teachers – those who are paid on the 22nd – from the 16th up to the 22nd. Then on the 22nd he collects. From the 23rd he will lend the money to the police who are paid on month-end. So he can make R85,000, but the mashonisa is looking for R60,000 … unaware that that guy is making a profit. … he was making money for himself now but the mashonisa didn’t know. So he was working for mashonisa for more than 2 years.

When informal moneylending expanded in the 1980s, and even more so from the mid-1990s onwards (Siyongwana Citation2004; Barchiesi Citation2011: 200, 210), credit apartheid was, in theory, coming to an end, but financialisation or ‘making money from nothing’ had become the only game in town (Ardington et al. Citation2004; Daniels Citation2004; Porteous & Hazelhurst Citation2004). Around this time, moneylenders also began to acquire their financialised technique of keeping borrowers’ ATM cards, aping the system that had been used by the new micro-lenders (sector 2) shortly before this was outlawed at the end of that decade. These arrangements involve a combination of willing engagement by borrowers, on the one hand – again involving an element of moral embedding and ‘trust’ – with resentment on the other hand, as they find themselves gradually drawn in and with little choice but to borrow again. ‘In the long run’ said one Impalahoek resident, ‘they exploit you because the interest they are charging is so high. You won’t ever finish paying. You pay and pay, and then you realize “now I’m being exploited”.’Footnote10

It was liberalisation that had enabled South Africa’s credit/debt revolution and allowed lenders of all kinds to extend loans with impunity. The attempts at regulation and registration that followed turned some of these lenders more explicitly into outlaws than they might have been. They were now planted more squarely in the informal domain where community embeddedness had once been a key feature of their business (see Hart Citation1973). But these mashonisas, previously involved (often via their agents) in relationships of trust, had now become beings for whom the ready and uninhibited flow of cash through accounts – facilitated by financial inclusion and especially by financialised techniques such as ATM-linked bank accounts – enabled ready payment and made things more financially formal. This automation might have diminished the opportunities for agents like Mathebula, while keeping his dealings secret from his ‘employer’, to craft his own personalised relationships with clients. But, it might equally have served him as a strategy in his endeavour of assembling a livelihood by bringing together increasingly formalised and bureaucratic arrangements with ever more informal and trust-based ones.

If the cases above show the origins of the credit/debt system and illustrate how it played out in the post-democracy period, the proposed solutions gave brokers further opportunities – or consolidated existing ones – to profit from hybridising the formal and the informal.

Credit ‘Post-Apartheid’: Reformers and Small-Time Creditors

Reformers, conscious of the moral transgressions inherent in credit apartheid, proposed to establish new systems of lending from which all might benefit. These were intended to obviate the need for black people to depend on HP agreements as they had done for decades, or rely on community moneylenders as they had started to do more recently (Ardington et al. Citation2004: 607). They would put in place new arrangements which would work for all and promote trust in the public good rather than forcing people to rely, instead, on informal, often violent, relationships with intermediaries (Gambetta Citation1988). These reforms worked less well than their designers intended, however, an outcome that owed much to the way multiple protagonists were invested in the continuation of the system-as-it-was, or were ready to shape-shift and assemble financial elements in new ways.

Attempting to find a solution to problems of indebtedness, government officials in the Department of Trade and Industry had entered into collaborations with human rights activists-turned-debt activists. One of these, Xolela May, told me how he had been spurred into action by his own embeddedness in the township community of Langa, near Cape Town, where he had gained an intimate knowledge of how new lenders (in sector 2) beyond the usual furniture retail sector were extending credit.Footnote11 With debtors being taken to court and repossessions carried out in record numbers, it was a broad spectrum of problems relating to ‘reckless lending’ that he and other designers of the National Credit Act (NCA), effective from 2007, intended to tackle.Footnote12 The act was ambiguous; however, it aimed not only to protect vulnerable and financially uninformed borrowers from unscrupulous creditors, but also, in the new spirit of affirmative action, to open up new possibilities for black business in fields which had previously been dominated by whites and other settler groups. Given that these new opportunities inevitably involved small-scale entrepreneurs extending credit in one way or another, the two aims proved to be at odds with each other.

As interested parties debated the proposed bill in parliament, details came to light of the earlier – and continuing – operations of credit apartheid. One problem was the way creditors had become accustomed to securing direct and involuntary repayment: they were no longer standing in line to ‘get the money’ as had been the case when observed by Ray Philips in the 1930s. Clerks in Magistrates’ Courts were readily, and in epidemic numbers, issuing garnishee orders.Footnote13 Creditors who present an employer with a garnishee order authorised by the clerk and countersigned by the indebted employee are entitled to take a portion of the debtor’s monthly pay before the employee receives it. But employers and policy-makers alike were noticing the negative consequences of this trend for the well-being of civil servants and factory workers. BMW, with its large car factories in the Eastern Cape, commissioned research which established the illegality of many practices used by debt collectors to attach workers’ salaries: the pressurising of debtors into signing the ‘consent to judgment’, normally required in proof of their having agreed to the arrangements, or the blatant use of forged signatures on these forms (Haupt et al. Citation2008; Haupt & Coetzee Citation2008); and the passing of orders by retailers in courts far from employees’ places of work which were then impossible to challenge without travelling long distances. ‘Debt administrators’ – some of them discredited lawyers – were also using practices of equally dubious legality, for example by charging a fee each time a garnishee order was granted on the wage or salary of the debtor (Smit Citation2008: 1–2; James Citation2015a: 62, 73). If one reads the judgement in a class action court case, brought to the Western Cape High Court, that eventually ruled against some of these practices in 2015, the list of respondents gives a sense of the odd bedfellows – with proliferating sub-intermediaries interpolating themselves into each gap that opened up – that had been gleaning rich pickings from these arrangements. Drawn from among the new micro-lending companies in sector 2, they included Mavava Trading, Onecor, Amplisol, Triple Advanced Investments, Bridge Debt, Las Manos Investments, Polkadots Properties, Money Box Investments, Maravedi Credit Solutions, Icom, Villa Des Roses, Triple Advanced Investments.Footnote14 The names, even without further information, give an indication as to the fly-by-night character of these businesses. All-in-all, the negative consequences of debt (they ranged from people resigning from their jobs to escape creditors, through cashing in their pensions, to tragic measures such as suicide) were here being intensified by illegal and unregulated collection practices. In response, some employers were resorting to paying wages directly in cash, or using pre-paid money cards delinked from bank accounts, in order to avoid creditors’ getting their hands on the money.Footnote15

Human rights lawyers like Xolela May were inspired with reforming zeal by a sense of moral outrage. They had watched their neighbours suffer furniture repossessions, the confiscation of earnings, and the stripping bare of bank accounts, by creditors (and their agents) in defiance of the law. During the parliamentary debates on the NCA, it was suggested, rather than passing new legislation, that the Magistrates’ Court Act simply be amended by making it mandatory to have judgments ‘dealt with in an open court of law’ rather than being given, either fraudulently or in ignorance, by uneducated clerks of the court.Footnote16 But this suggestion was not taken up, and it would take another 10 years before the Western Cape High Court case definitively established the illegality of these practices.

As reforms aimed at curbing these excesses, and as related practices of ‘reckless lending’, were debated in parliament, assorted micro-lenders in sector 2 energetically contested these to protect their innovative lending assemblages. An organisation representing their interests, Balboa, argued that to curb the activities of lenders would be to outlaw the livelihoods of many low-income people (including financial intermediaries). The well-worn practice of ‘direct selling’ on credit and on commission by salesmen visiting employees’ places of work came up for debate. Balboa vigorously defended the rights of such sellers, pointing out that the reason why they visit the ‘work places of potential consumers to enter into loan agreements’ is largely because such ‘consumers are not able during office hours to attend at the credit provider’s physical premises’, and hence that visiting them at the workplace offers a ‘convenient, speedy and efficient’ solution. Prohibiting such a practice, they argued, would result in the closure or restructuring of ‘many small credit operator businesses relying solely on agents to sell their goods and/or products to employees at their work’ and in these agents’ loss of livelihood: ‘a large section of the economy will effectively be destroyed overnight.Footnote17

The high-minded tone of this submission, which defends the needs of small-scale entrepreneurs, obscures moral ambivalences about borrowing and lending. Balboa Finance is one of those organisations offering unsecured loans at high rates of interest. Yet, it is likely that many of its clients, operating along the same lines as ‘Avon ladies’ (Dolan & Scott Citation2009) and other multi-level marketers in schemes that are pervasive in South Africa, are using the money they borrow to establish their petty enterprises: yet another case of borrowers-become-lenders. As it turned out, these sellers’ practices were left unregulated by the act: preventing them from selling on credit might well have circumscribed their activities while leaving bigger lenders untouched. In the same year, a case came to court in which a small-scale creditor of this kind instructed a lawyer to repossess the house of a borrower in order to recoup outstanding debts. The judge ruled that it was unconstitutional to deprive people of their right to housing, but the Minister of Justice protested, observing that removing the right to repossess such property would act not only against ‘big firms’ but also against informal sellers-on-credit, often barely better off than their customers.Footnote18

Some of the points noted in this section might seem to substantiate the claim that South African law is biased in favour of creditors (Boraine & Roestoff Citation2002: 4). Whether lenders hail from large corporations from sector 1, or smaller ones in sector 2, little seems to stand in the way of their having loans repaid. Although they must calculate rates of non-repayment, or run risks imposed by their reliance on agents embedded in local contexts, such disadvantages seem to be outweighed, more recently, by the freedom to recoup loans using techniques such as garnishee orders; and by the prevalence of intermediaries, debt administrators, and collectors willing to facilitate the collection of loans. In other respects, however, the contradictory character of the reforms that were implemented is revealed. For every piece of protection offered to borrowers, one of the semi-formal income-generating opportunities embraced by brokers inhabiting marginal spaces might be forfeit. All-in-all, it is the roles they play that must qualify any claim of creditor advantage, since so many people merge the role of lender with that of borrower.

Conclusion

Is people’s powerlessness in the face of initiatives undertaken by powerful interests augmented if neoliberal forces persuade them into complicity, such that their daily livelihoods depend both on their participation in it (and on their drawing others, as brokers, into its ambit, making its techniques intimate rather than remote)? Where critical accounts emphasise the newness of such schemes of inclusion (Dolan Citation2013; Elyachar Citation2005; Huang Citation2015; Meagher Citation2013), individuals in South African society have long devised ways to challenge the terms of their exclusion by incorporating themselves into money-making activities. Attempts to tackle the problem of credit apartheid by incorporating the marginal and previously politically disenfranchised in fact ended up entrenching the embeddedness of agents, go-betweens and petty entrepreneurs in the system as-it-was – or enabled them to seize on new opportunities. In this setting of rapid change, where forces of state and market have intertwined to create a redistributive neoliberalism, brokers do not merely negotiate between fixed positionalities, or translate between and merge previously irreconcilable points of view. Instead they bring into being new socio-economic positions and identities, as I have argued elsewhere (James Citation2011). Countervailing discourses – of disembedded financial formality versus trust and intimacy – play their part in perpetuating, while enabling the continual readjustment, of a set of systemic yet creatively innovative arrangements. Intermediaries, repossession agents, and moneylenders use personalised relationships to challenge the restrictions of formal inclusion by assembling new terrains in which to operate.

Gaining access to the money – however small the amount – of the widest possible range of people is essential to generate profit in a system based more on consumption and rent-seeking than production. This paper has shown some of the underpinnings and contradictory aspects of the situation, bearing out Gambetta’s observations about the difficulty of distinguishing ‘between victims and accomplices’ (1998: 170). The onset of borrowing and lending possibilities unleashed by South Africa’s credit/debt revolution produced a peculiarly mediated kind of capitalism.

Acknowledgements

Opinions expressed are my own. Thanks to Isak Niehaus, Sputla Thobela, Eliazar Mohlala, Xolela May, and all those who spoke to me in the field; and my gratitude for feedback in the following fora: the session at EASA 2013 which the editors of this volume convened; Chris Harker and those attending the workshop on Precarious relations: obligations and mutuality, Geography Department, Durham University; Dimitra Kofti and those attending the Colloquium at the Max Planck Institute, Halle, Germany; Preben Kaarsholm and Bodil Folke Frederiksen and those attending the symposium on ‘Consumerism, regulation and informality in South Africa and Kenya: A discussion of two African settings’, Roskilde, Denmark.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 I use the terms ‘broker’, ‘intermediary’, and ‘agent’ interchangeably. See the introduction for further explanation on how these figures act as assemblers, as connective agents who bring together assemblages that consist of different actors, institutions, and resources.

2 “Micro-lending” is locally defined as oriented only to consumption, as distinct from development-oriented “micro-credit” (see Kar Citation2013) which is known for its relative lack of popularity in South Africa (Reinke Citation1998).

3 Seekings and Nattrass have used the term ‘distributional regime’ (Citation2005, 314) to discuss this extensive reliance on state resources.

4 Muzila Nkosi, Impalahoek, 26 March 2009.

5 Ace Ubisi, Impalahoek, 16 August 2008.

6 Rebecca Matladi, Johannesburg, 15 April 2010.

7 Samuel Kgore, Impalahoek, 22 August 2008; see also James (Citation2015a: 111).

8 Solomon Mahlaba, Impalahoek, 26 March 2009.

9 Ace Ubisi, Impalahoek, 23 August 2008.

10 Solomon Mahlaba, Impalahoek, 26 March 2009.

11 Xolela May, Knysna, 8 October 2008.

13 These are known as debt recovery orders in the UK.

14 University of Stellenbosch Legal Aid Clinic and Others v Minister of Justice and Correctional Services and Others (16703/14) [2015] ZAWCHC 99 (8 July 2015), http://www.saflii.org/za/cases/ZAWCHC/2015/99.html#.

15 Tony Beamish, personal communication.

16 Commentary By Vincent Van Der Merwe, J C Grobler & Burger Inc., 5 August 2005, presented to the portfolio committee for Trade and Industry.

17 Balboa submission on the National Credit Bill, 28 July 2005, presented to the portfolio committee for Trade and Industry.

18 Jaftha v. Schoeman and Others; van Rooyen v Stoltz and Others, 2005(2) SA 140 (CCT 74/03), http://www.saflii.org/za/cases/ZACC/2004/25.html. Thanks to Glenda Webster for bringing the case to my attention.

References

- Anders, Gerhard. 2009. In the Shadow of Good Governance: An Ethnography of Civil Service Reform in Africa. Leiden: Brill.

- Arce, A. & N. Long. 1993. Bridging Two Worlds: An Ethnography of Bureaucrat-Peasant Relations in Western Mexico. In An Anthropological Critique of Development: the Growth of Ignorance, edited by M. Hobart, pp. 179–208. London: Routledge.

- Ardington, Cally, David Lam, Murray Leibbrandt & James Levinsohn. 2004. Savings, Insurance and Debt Over the Post-Apartheid Period: A Review of Recent Research. South African Journal of Economics, 72(3):604–640. doi: 10.1111/j.1813-6982.2004.tb00128.x

- Bähre, Erik. 2007. Money and Violence: Financial Self-Help Groups in a South African Township. Leiden: Brill.

- Barchiesi, F. 2011. Precarious Liberation. Workers, the State and Contested Social Citizenship in Postapartheid South Africa. Albany: SUNY Press.

- Boraine, André & Melanie Roestoff. 2002. Fresh Start Procedures for Consumer Debtors in South African Bankruptcy law. International Insolvency Review, 11(1):1–11. doi: 10.1002/iir.95

- Breckenridge, Keith. 2005. The Biometric State: The Promise and Peril of Digital Government in the New South Africa. Journal of Southern African Studies, 31(2):267–282. doi: 10.1080/03057070500109458

- Breckenridge, Keith.. 2010. The World’s First Biometric Money: Ghana’s E-Zwich and the Contemporary Influence of South African Biometrics. Africa, 80(4):642–662. doi: 10.3366/afr.2010.0406

- Cohen, David. 2004. People Who Have Stolen From Me: Rough Justice in the new South Africa. London: St Martin’s Press.

- Comaroff, John L. and Jean Comaroff. 1992. Ethnography and the Historical Imagination. Boulder: Westview Press.

- Daniels, Reza. 2004. Financial Intermediation, Regulation and the Formal Microcredit Sector in South Africa. Development Southern Africa, 21(5):831–849. doi: 10.1080/0376835042000325732

- Dolan, Catherine. 2013. ‘Capital’s ‘Great Leap Downward’: Remaking Africa’s Informal Economies at the Bottom of the pyramid’, paper delivered at ECAS Conference, Lisbon.

- Dolan, Catherine & L. Scott. 2009. Lipstick Evangelism: Avon Trading Circles and Gender Empowerment in South Africa. Gender and Development, 17(2): 203–218. doi: 10.1080/13552070903032504

- DTI (Department of Trade and Industry)/Reality Research Africa. 2002. Credit Contract Disclosure and Associated Factors. Pretoria: Department of Trade and Industry.

- DTI (Department of Trade and Industry). 2004. Consumer Credit law Reform: Policy Framework for Consumer Credit. Pretoria: Department of Trade and Industry.

- Eisenstadt, S.N. & L. Roniger. 1980. Patron–Client Relations as a Model of Structuring Social Exchange. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 22(1): 42–77. doi: 10.1017/S0010417500009154

- Elyachar, J. 2005. Markets of Dispossession: NGOs, Economic Development, and the State in Cairo. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Epstein, Gerald A. 2005. Introduction: Financialization and the World Economy. In Fincialization and the World Economy, edited by Gerald A. Epstein, pp. 3–18. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Gambetta, Diego. 1988. Mafia, the Price of Distrust. In Trust: Making and Breaking Co-Operative Relations, edited by D. Gambetta, pp. 158–175. Oxford University Press.

- Gregory, Chris A. 2012. On Money Debt and Morality: Some Reflections on the Contribution of Economic Anthropology. Social Anthropology, 20(4):380–396. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8676.2012.00225.x

- Han, Clara. 2012. Life in Debt: Times of Care and Violence in Neoliberal Chile. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Hart, Keith. 1973. Informal Income Opportunities and Urban Employment in Ghana. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 11(1):61–89. doi: 10.1017/S0022278X00008089

- Haupt, Frans and Hermie Coetzee. 2008. The Emoluments Attachment Order and the Employer. In Employee Financial Wellness: A Corporate Social Responsibility, edited by E. Crous, pp. 81–92. Pretoria: GTZ (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit).

- Haupt, Frans, Hermie Coetzee, Dawid de Villiers and Jeanne-Mari Fouché. 2008. The Incidence of and the Undesirable Practices Relating to Garnishee Orders in South Africa. Pretoria: GTZ (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit).

- Huang, Juli. 2015. “Detachment and Relational Work in a Social Enterprise: The iAgents of Bangladesh.” unpublished seminar paper, LSE.

- James, Deborah. 2011. The Return of the Broker: Consensus, Hierarchy and Choice in South African Land Reform. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 17:318–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9655.2011.01682.x

- James, Deborah.. 2012. Money-go-round: Personal Economies of Wealth, Aspiration and Indebtedness in South Africa. Africa, 82(1):20–40. doi: 10.1017/S0001972011000714

- James, Deborah.. 2015a. Money from Nothing: Indebtedness and Aspiration in South Africa. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.

- James, Deborah.. 2015b. ‘Women use Their Strength in the House’: Savings’ Clubs in an Mpumalanga Village. Journal of Southern African Studies, 41(5):1–18. doi: 10.1080/03057070.2015.1062263

- Kar, Sohini. 2013. Recovering Debts: Microfinance Loan Officers and the Work of “Proxy-Creditors” in India. American Ethnologist, 40(3): 480–493. doi: 10.1111/amet.12034

- Krige, Detlev. 2011. Power, Identity and Agency at Work in the Popular Economies of Soweto and Black Johannesburg (Unpublished D.Phil. dissertation). Social Anthropology, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. http://wiredspace.wits.ac.za/handle/10539/10143 (Accessed 30 January 2013).

- Krige, Detlev.. 2014. Letting Money Work for us: Self-Organization and Financialisation From Below in an all-Male Savings Club in Soweto. In People, Money and Power in the Economic Crisis, edited by Keith Hart and John Sharp, pp. 61–81. New York: Berghahn Books.

- Langley, Paul. 2008. The Everyday Life of Global Finance: Saving and Borrowing in Anglo-America. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lindquist, Johan. 2015. Brokers and Brokerage, Anthropology of. In International Encyclopedia of Social and Behavioral Science, edited by James D Wright, 2nd ed., pp. 870–874. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- Martin, Randy. 2002. The Financialization of Daily Life. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- Meagher, Kate. 2013. ‘The Trouble That Lurks Beneath: Globalization, African Informal Labour and the Employment illusion’, paper delivered at ECAS Conference, Lisbon.

- Parry, Jonathan. 2012. Suicide in a Central Indian Steel Town. Contributions to Indian Sociology, 46(1–2):145–180. doi: 10.1177/006996671104600207

- Peebles, Gustav. 2010. The Anthropology of Credit and Debt. Annual Review of Anthropology, 39:225–240. doi: 10.1146/annurev-anthro-090109-133856

- Philips, Ray. 1938. The Bantu in the City. Johannesburg: SAIRR.

- Piliavsky, Anastasia. 2014. Introduction to Patronage as Politics in South Asia, edited by A. Piliavsky, 1–38. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Porteous, David & Ethel Hazelhurst. 2004. Banking on Change: Democratizing Finance in South Africa, 1994-2004 and Beyond. Cape Town: Double Storey Books.

- Randeraad, N. 1998. Introduction. In Mediators Between State and Society, edited by N. Randeraad, 8–16. Hilversum: Verloren.

- Reinke, Jens. 1998. How to Lend Like Mad and Make a Profit: A Micro-Credit Paradigm Versus the Start-up Fund in South Africa. Journal of Development Studies, 34(3): 44–61. doi: 10.1080/00220389808422520

- Roth, James. 2004. Spoilt for Choice: Financial Services in an African township (PhD dissertation). University of Cambridge, Cambridge.

- Schreiner, Mark, Douglas H. Graham, Manuel Cortes Font-Cuberta, Gerhard Coetzee and Nick Vink. 1997. ‘Racial Discrimination in Hire/Purchase Lending in Apartheid South Africa’, paper presented at AAEA Meeting, Toronto, Canada.

- Seekings, Jeremy and Nicoli Nattrass. 2005. Class, Race, and Inequality in South Africa. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Shipton, Parker. 2007. The Nature of Entrustment: Intimacy, Exchange and the Sacred in Africa. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Siyongwana, Paqama Q. 2004. Informal Moneylenders in the Limpopo, Gauteng and Eastern Cape Provinces of South Africa. Development Southern Africa, 21(5):861–866. doi: 10.1080/0376835042000325741

- Smit, Anneke. 2008. Administration Orders Versus Debt counselling (LLM dissertation). University of South Africa, Pretoria.

- Tlali, Miriam.1979. Muriel at Metropolitan. Johannesburg: Ravan Press.