ABSTRACT

War photographs have remained essential to the propaganda machinery of the Iranian state since the inception of the war with Iraq. These photographs contribute to the visual culture of martyrdom and are celebrated within a dominant meaning-making regime. However, there are rare counter-narratives that unsettle the master narrative of the Iranian state and I turn to that of a war photographer whose work is side-lined by the state. I explore this counter-narrative to discover the workings of the state-sanctioned narrative through modes of reception of the photographs by Iranians both inside and outside Iran. I strive to trace the reception of the pain of others through politics of frame and the ethnography of the visual culture of martyrdom after almost three decades since the war.

Eight years of war and bloodshed drew the Western borders of Iran and Iraq with the blood of more than 200,000 combatants and non-combatants. The war has become the permanent mark of the last month of the summer in the Iranian calendar, when commemoration of the war turns cities colourful. The central squares, main thoroughfares and every alleyway are covered with posters of martyrs, flags and various commemorative installations. Iran is immersed in an intense collective remembering for seven days. Hafteye Defa’ Moqadas (The Week of the Sacred Defence) celebrates the ceasefire treaty and recalls tales of martyrdom, sacrifice and battlefields. In September 2012, Isfahan’s municipality commissioned a creative agency to turn Chaharbagh – the main and longest street in the city – into an open-air museum in memory of its martyrs and in commemoration of the war.

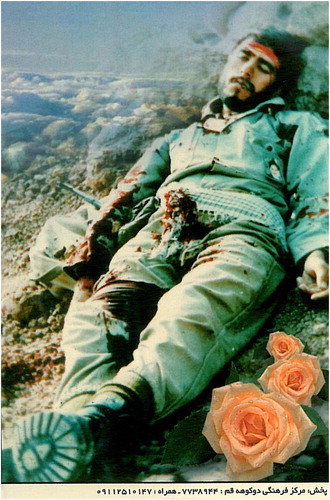

The street became a long and crowded stretch of commemoration through which everyone had to navigate while walking to their destinations. The challenge of passing through the crowds was not due to the art installations and military equipment that were on display. It was those who stopped to take selfies with various installations who slowed the stream of people walking towards their destinations. I noticed a group of teenagers gathered around an installation that resembled a combat foxhole, with sandbags protecting a combatant in it. It seemed like the usual recreation of battlefields and trenches but it was the startling recreation of the picture of Amir Haj AminiFootnote1 ().Footnote2 The image of his tranquil but bloody face after he was shot in the trenches is one of the most circulated posters among Iranian revolutionary youth. His picture stands for what a martyr, fallen on the battlefield, looks like in Iranian social imaginaries.

The installation was unsettling because an artist had recreated the scene with a life-size mannequin draped in a uniform stained with the blood. The mannequin truly looked like the bloodied corpse of Haj Amini, who had fallen in the middle of the trench. The teenagers took turns to lie beside the mannequin and take photos of each other. They noticed my unsettled stare and rolled with laughter. The one who lay beside the mannequin turned and asked with a smirk ‘Have you come from behind the mountains, Sir? Death lives in our neighbourhood.’ The one who was taking the photo then answered with a line from a poem, without looking at me: ‘Har Anche dideh binad del konad yad’ (Whatever the eyes see then the heart desires). The implications of the poem provoked a stream of questions in my mind: ‘So he sees death and then he desires martyrdom or maybe he sees martyrs and then he wants to become a martyr?’ The questions evolved around the inner workings of seeing: the ways of seeing and the desire to be seen and to see were succinctly summarised in the poem. His remark intrigued me and led me to trace the link between the desiring heart and the wondering eyes that provoked the heart to desire. However, I learned later that this link is not limited to meanings represented and that a detailed observation of the process of seeing and desiring should include the ways of seeing and how the viewers ‘situate themselves in it’ (Berger Citation2008: 11). Hence, I looked beyond the question of signification and turned towards the ways of seeing and of receiving framed visual signifiers. This article brings together an ethnography of the visual culture of martyrdom by exploring the reception of photographs of a celebrated Iranian war photographer.

I start by situating my journey and debate within the context of the visual culture of martyrdom that emerged following the Iran–Iraq war in order to explain my method and anthropological ways of seeing. The article then expands the notion of framing the pain of others through two basic questions: I ask, on the one hand, how a visual anthropologist could treat the frame, its reception, circulation and configuration. Then, on the other, I question how the visuality of pain occurs and how the politics of this issue highlights the complexity of framing the pain of others in post-conflict societies. These questions are substantiated through the work of Mahdi Mon’em, a war photographer whose work portrays the lives of non-combatants who suffered injuries because of but not necessarily during the war. Finally, I share my ethnography of the reception of these photographs both inside and outside Iran to address the inner workings of photographic framing and regimes of visuality within the visual culture of martyrdom. Thus we can learn how the ways of seeing and the imaginaries of pain are influenced by the state and its culture industry in order to maintain the flows of power and to control the historical narratives and memories.

The ethnography focuses on Iranians’ reception of war photography to highlight what Mitchell (Citation2002) calls ‘the invisible and the unseen’ in the visual culture of martyrdom. However, I neither place the unseen within the signification and meaning-making regime nor trace the reception of the invisible within the frame through the responses of the beholders/viewers. I trace the ontogenesis of frames of war photography through ‘the interactive convocation of existing entities’ (Ingold Citation2012: 437) such as images, semiosis, photographers and international and national politics, to craft an approach in visual anthropology. My approach seeks the configuration of a frame beyond its photographic appearance and semiotic contents and redefines the frame beyond the well-known rectangular fixture around an image. Through an ethnography of framing and photo-elicitation, I encourage a form of visual anthropology that treats a frame as an emergent property of the assemblage of visual culture rather than focusing on single elements such as symbolism, iconology, meanings and intentions framed within images. Therefore, I place the conceptual frame of my approach in inspiration from the two larger strands of reception studies, though I follow neither of them. The current trends in reception studies either limit the configuration of a frame to authorial intentions (Culler Citation1992; Fetveit Citation2001) or they discount the author and hand over the meanings of a frame to the eyes of the beholder and to cultural semiosis (Barthes Citation1971; Iser Citation1978; Machor & Goldstein Citation2001). I attempt to draw from both these approaches though I do not abandon the framed pain of others within the multiplicity of viewings and how meanings are devised in a multitude and diversity of receptions. Instead, I trace the ontogenesis of a frame, the production of a production – in other words, I follow the modes of engagement with the framed pain of others in war photography to highlight how the socio-cultural life of an image shapes its appearance. It is not enough to ask what a frame means, what people see in it and what the affective responses towards it are. Instead, we should seek the complexities of a frame by asking how it is configured as such and what people do with the frames.

Pain in the Symbolic Vortex of Martyrdom

In this section, I introduce the cultural folds and social configurations of the Iranian visual culture of martyrdom and ask how the ways of seeing correspond to the orchestrations of the visual culture by the Iranian state and how the visual culture of martyrdom is received in different temporal and socio-political contexts. I stress the orchestration of visual culture not to highlight the workings of propaganda but to point at what Möller (Citation2013) and Saramifar (Citation2016) call the ‘surplus of meanings’. Möller identifies the surplus of meanings in the image by broadening Susan Sontag’s idea of repeated exposure and Saramifar focuses on the surplus by applying Deleuzian ‘becoming’ to narrative and biography analysis. The surplus or, in other words, the recurring meaning becomes the central point/intensified fold that is sedimented in the frame/text and ties all socio-cultural semiotic qualities together that reside within the frame/text despite their diverse reception by the people. The people receive the frames differently through their diverse ways of seeing because ‘the surplus of meanings carr[ied] with … [frames] does not evaporate; it is there to be discovered and rediscovered’ (Möller Citation2013: 41). Hence, I trace the reception of a frame to inquire about this surplus of meanings, these settings and the orchestration of the visual culture of martyrdom and to trace how certain meanings are infused into the frames and take on recurring meanings.

Fischer sees the surplus meanings via Iranian Shi’i sensibilities that are emotionally charged by ‘the abstraction from history and the different evaluations [of history]’ (Citation1980: 314). The abstraction and re-narration of this history since the 1979 Revolution has brought about a regime of signification among Iranians – a regime which imposes a symbolic vortex of martyrdom through what Fischer and Abedi call ‘small media’ (Citation1990) of the Islamic revolution in Iran. Posters and photographs that circulate within the symbolic vortex reveal ‘indices of consciousness’ (Citation1990: 339) that condense meanings within a frame in the assembly of a multifaceted co-creation of meanings. In Debating Muslims (Citation1990) they show that Iranians encounter meanings in the creative tension that is framed in posters, graffiti and insignias. They trace the regime of signification and stress to the obsessive fascination of many Iranians with deciphering signifiers and symbols. Fischer and Abedi remain within the politics of meanings of small media but the question of how those meanings and frames emerge from the circulation of small medias remains unattended. I agree with their emphasis on the multiplicity and diversity of obsessive decoding of the meanings by Iranians but, for me, the more urgent questions are which and whose meanings tend to overcome and become determinant in the circulation of small media. In other words, they have considered what Butler (Citation2016) calls the ‘intelligibility’ of frames to determine the historical schema that constitute the historical a priori that is culturally operated. However, they have neglected to look at how ‘apprehending [is] … bound up with sensing and perceiving’ (Butler Citation2016: 6). Interestingly, the small media in Iran runs counter to what Gilman (Citation2015) traces in the afterlife of the martyr pop genre and video clips produced during Arab Uprisings in Egypt. The regime of visuality propagated by Egyptian small media depoliticised ‘potential subversive and counter-hegemonic meanings’ (Citation2015: 706) carried in martyred bodies. However, the ways of seeing propagated in Iran intensified the politics of martyred bodies by turning them to explicit symbols and myths. Chelkowski and Dabashi explored ‘the plethora of collectively constructed myths and symbols’ (Citation2001: 6) in the Islamic Republic of Iran’s (hereafter IR) visual culture. They emphasised the construction of meanings with reference to Islamic connotations and the creative appropriation of Islam by people, despite what the IR propagates and disseminates. However, their framework remains rather static, with meanings that are constructed and fixed rather than evolving along socio-cultural pathways that shape meaning-making processes. These authors engage with a religious and historical narrative that is rooted in Shi’i practices and determines the parameters of martyrdom in Iranian Shi’i culture. Usually, this master narrative – encouraged and propagated by the IR – has been the first step for others seeking to speak of visual culture martyrdom in Iran.

However, I here explore the visual culture of martyrdom through a counter-narrative to the master narrative, rather than merely mapping modes of signification and semiotics of the latter. I question configurations of the visual culture via the counter-narrative to highlight how Iranians’ social imaginaries are restrained and limitations are imposed on their religious-political subjectivities by an incessant regime of signification. The impositions are detected through an analysis of a photographic counter-narrative that offers different frames of representation through the portrayal of the pain of non-combatants beyond the conventional rhetoric of martyrdom in Iran. I strive to achieve the proposed notion via the issue of how photographs of non-combatants who suffered war injuries are framed by a war photographer and how these frames are received by Iranians. The recurring questions in my research focus on how rather than what and why by following Mieke Bal’s (Bal & Bryson Citation2001) attempt to see visuality as semiotic and meaning-making rather than scenic and unitary. It is achieved by placing the meaning-making in the fabric of socio-cultural life and dis-aligning the power dynamics embedded in the frame. The power dynamics between the photographer, the state, the propaganda, the spectator and the history/memory should be dis-aligned in order to show how frames behave socially and ‘enable subjects to communicate without giving themselves away’ (Bal Citation2007). How does visuality happen? is the question that has driven my ethnography of reception of the visual culture of martyrdom in southern regions of Iran and amongst Iranian refugees in Western Europe.

I preferred war photography out of many different visual expressions in the realm of Iranian visual culture of martyrdom, a preference which, despite Iranian war films, has been creative, vibrant and controversial among viewers. My choice of photography remains inspired by Metz (Citation1985), who recognised the ability of photographs to become a fetish in comparison with the cinema. He names various differences between photography and the cinema that make the former capable of becoming a fetish – differences such as the lack of temporal size, social uses of photographs that make them more accessible to ‘ordinary’ people, the immobility and silences of the content of photographs and also their ‘deeply rooted kinship with death’ (Metz Citation1985: 83). Indeed, photographs of martyrs and the framed pain of others have turned into a fetish that incessantly appears in the lives of Iranians in the form of notebook stickers, T-shirts, posters, murals, wall-paintings, advertising banners, coffee-table books, daily newspapers and magazines. The IR perpetuates an orchestrated ‘vortex of symbolic investment’ (Rigney Citation2005: 18) through various visual means like wall-paintings, graffiti, banners and murals that include Quranic verses, quotes from supreme leaders, depictions of martyrs and various programmes in national broadcasts. It is an orchestrated effort that imposes its overwhelming presence and affective assembly over viewers and constitutes the visual culture of martyrdom, a visual culture that penetrates everyday affairs beyond mere images, posters and murals: imagine an office worker whose daily commute features martyrs’ depictions staring down at him or her from high-rise buildings and banners as s/he takes a taxi to a street named after martyrs, endures the traffic while passing memorials planted at every intersection and bridge, to finally arrive at a building dedicated to martyrs. There are few corners untouched by the visual culture of martyrdom that represents sacrality and calls on viewers to be attentive to the gaze of Allah and the path of salvation. Viewers become hostage to a regime of signification that traces itself to the annals of Shi’i history and Islamic traditions of sacrifice. The viewers may not comply with the gaze or grow numb against the regime of signification but the incessant presence restrains them within the enforced meaning regardless of their resistance or acceptance. This incessant presence turns into a symbolic vortex that challenges the desensitised response to the collective memory of the war and emerges more creative than before to captivate and attract viewers to itself ().

Figure 2. The largest mural commissioned from a creative agency in a high traffic zone in front of the college of journalism. © FardaNews.

The large machinery of meaning-making and fabricating ways of seeing is not limited to names of streets, wall-paintings, posters, memorials or murals. Iranian war photographers contributed to this regime through their ways of framing and photographing the war. The news and photographs from the frontlines of the Iran–Iraq war were controlled and distributed mostly by the IRNA (Iranian News Agency), which maintained a list of 14 approved photographers. Nowadays, they are accorded prestige because of their depictions of the sacrality of martyrdom during the war – prestige that other photographers did not receive. I focus on the work of one of these photographers, Mehdi Mon’em, whose work portrays and frames a counter-narrative to the dominant visual culture of martyrdom. I explore Mon’em’s work in War Victims (2009, hereafter WV) in order to provide a platform for further discussions of how some Iranians receive this counter-narrative and how it appears framed, authentic or mere fabrication to them. I address details of some of his photographs that I viewed and discussed with Iranians in light of the politics of war photography in Iran since the 1980s to highlight how they contrast with the manufactured visual culture of martyrdom. I focus particularly on the politics of war photography and representation in order to consider shadows that touch meanings in various ways – by congealing pain into suffering, freezing life into victimhood and translating death into martyrdom. The politics that I trace shape the pain of others into what Kleinman (Citation1992) calls ‘naturalizing or sentimentalizing suffering’ through a dominant discourse that articulates ‘collective modes of experience that shape individual perceptions and expressions’ (Citation1992: 169).

Dauphinée (Citation2007) highlights the politics of bodies in pain and collective modes of experience with regard to the ethics of using war imageries that strive to project counter-narratives to the mainstream perception of wars. She points at the incessant symbolic vortex of imagery to explain the ‘festishization of pain through the recirculation of imagery’ which objectifies bodies ‘toward the service of particular kinds of politics’ (Citation2007: 140). Both Kleinman (Citation1992) and Dauphinée (Citation2007) follow the sociality of pain and attempt to broaden the approaches to it so that the pain of others can be accessed. Kleinman looks at chronic illness and corporeal inflictions to address how the pain becomes ‘sociosomatic processes that inscribe history and social relations’ (Citation1992: 169). He begins with the sufferings of the individual and reveals how his or her pain becomes social; Dauphinée follows the social circulation of the controversial images of prisoners’ bodies at Abu Gharib in order to address ‘whether it is possible for us to recognize pain in the body of another’ (Citation2007: 140). For her, this question remains ‘without a solution’ (Citation2007: 153) because she prefers a mode of engagement with the framed pain of others that is linked with the ‘logics and economies’ (Citation2007: 153) of violence. However, I trace the framed pain of others regardless of its accessibility (economics) or the kind of violence it propagates or masks. I follow the pain of others within the frame of war photography to show that it is the circulation of images which produces the frame and not the correspondence between the one in front of the camera and the one who holds it. I conducted an ethnography by collecting Iranians’ interpretations and receptions of the visual culture of martyrdom in Khuzestan (a province to the south-west of Iran) while preparing for my current project, ‘Memory and narrativity in post-war Iran’. The project concentrated, in particular, on those of the second generation of the Islamic revolution who have remained committed to the value system propagated by the state. I realised later the need to include those who became disenchanted with the value system but who did not oppose it radically. I found that most of those who were disenchanted by the system tended to become apathetic or became political refugees who continued their activism abroad.

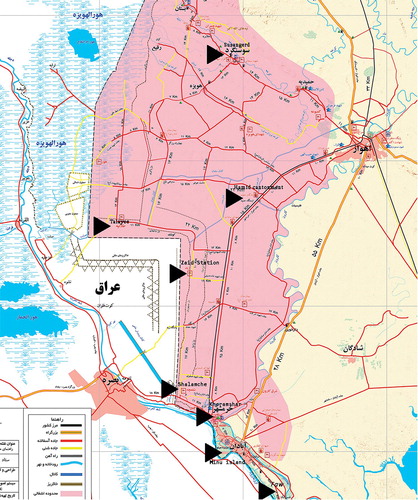

I was able to continue my ethnography in Western Europe, two years after the first part of my fieldwork was conducted in Khuzestan. My encounters were scattered across three years, during which I was engaged in different projects in Iran and Western Europe. In order to substantiate the discussion of the visual culture of martyrdom, I arranged 5 in-depth interviews with war photographers and social media activists, 3 focus-group discussions around the visual–public representation of martyrs and 10 one-to-one explorations of the war photographs (photo-elicitation). The in-depth interviews began with the simple act of exploring photographs together with my familiars and informants, who often continued till midnight discussing martyrdom, mysticism and regional politics. The group discussions remained more animated and became heated conversations with revolutionary young men who were mostly volunteers and helped those visiting the war memorials in Khuzestan. Iranians who I spoke with and observed in Khuzestan were paying homage to martyrs during a month-long commemoration tour known as Rahiyan Noor. This tour resembles a pilgrimage and homage paid to the sacred grounds usually takes place in the last week of the last month of the Iranian calendar and extends into the New Year holidays.Footnote3 Some Iranians travel to border areas and visit former combat zones to pay their respects to martyrs – in so doing, they are acting as pilgrims who acknowledge the sacrality of martyrs’ blood beyond the rhetoric of nationalism and nationhood. They claimed firm allegiance to the Islamic revolution and expressed their affinity with the rhetoric of martyrdom-as-the-path-to-salvation ().

Arranging interviews was easier in Iran because of my networks and familiarity with the country. However, it remained challenging in Europe because of the limitations for Iranians of obtaining a visa and travelling to Europe. I sought those of the revolution’s second generation who become political refugees due to their activism. The Iranian refugees whom I met during the second part of my ethnography implied that their displacement and sufferings were the legacy of the same revolution which the young revolutionaries today revered and remained committed to. These refugees belong to the generation that experienced Iran during the war, when it took new shapes in Iran, but they had recently taken refuge along with the flow of Syrian refugees who reached Western Europe. I arranged 10 in-depth interviews and photo-elicitations with Iranian political refugees, using the opportunities of travelling for conferences and of fieldwork in refugee camps in Western Europe. Here, I refer to the field notes that were compiled from the conversations and arguments with young Iranian revolutionaries in Iran and Iranian refugees in the Netherlands, Germany and France.

Photographing Combatants and the Representation of Martyrdom

While the Iran–Iraq war officially ended in 1988, Khomeini conveyed that the battle was over but that the war would continue because the enemy remained standing – a notion that ‘would not cause Khomeini to lose power but would in fact help him to consolidate his rule’ (Farhang Citation1985: 659). Consequently, the high-intensity combat that dominated the frontlines began to take on another form as it was transferred to the frontiers of visual culture, memory and remembering (Khosronejad Citation2012). Kaveh Ehsani explains how ‘a vast culture industry was set up to frame the war as “Sacred Defense” and to memorialize and extoll its virtues through public art, murals … and dedication of the two available official television channels to war propaganda’ (Citation2017: 2). As already mentioned, images of martyrs of the war are ubiquitous and constantly reproduced by the vast propaganda machinery of the Iranian state. For instance, the capturing of U.S. Navy sailors by Iranian military forces on January 2016Footnote4 was commemorated recently by commissioning Danial Farokhi, a celebrated graphic designer who is associated with the IR’s culture industry, to create and install the largest mural in Iran. The murals usually follow similar patterns of a martyr gazing into the horizon, blue sky in the background, white doves and red tulips around the portrait, Iranian flag alongside flags with the names of religious figures etc. Very little about the sacrality of the image is left to the imagination by the addition of Quranic verses and prophetic quotes. Captions and slogans inscribed over the paintings convey the jubilance of martyrs who have reached salvation and have indulged in the absolute truth. However, if Quranic verses are not inscribed over the paintings, the images of supreme leaders appear in the corners to infuse political sacrality.

The combination of murals commissioned by the Martyrs’ Foundation, war photographs and exhibitions broadcast by the IRNA, war storytelling in the Iranian media, and war paraphernalia sold in a market dominated by religious affiliations all enforce a regime of remembrance through Iranians’ ways of seeing and imagining. The regime of remembrance depicts the fallen as martyrs who have reached a state of grace. It constantly reminds us that they are not mere dead bodies; rather they are blessèd sacred souls who shall awaken and enlighten the living. The regime of remembrance and signification drawn across Iran finds its semiotic traces within Shi’i religiosity that proposes rasteghari (salvation) through sacrifice and martyrdom. This form of religiosity finds its meanings in tales of the battle of Karbala in 680 AD and the martyrdom of Hussain, who was the cherished grandson of the prophet Muhammad. Khosronejad takes various steps in his œuvre to show how Shi’i religiosity and the war are intertwined. He states that his research reveals that those who advocate Shi’i religiosity firmly believe those values and ideologies to be divine interventions that ‘changed all of the previous strategies, techniques and values of all wars and fronts’ (Khosronejad Citation2013: 4). A seasoned war veteran’s explanation of martyrdom resonated with Khosronejad’s observation. He mentioned that ‘martyrdom was a blessing … [and] the divine tactic that jammed Iraq’s war machine’.

Iranians experience and receive the propagated visual culture of martyrdom within the tension that rises from the aporia, wonder and admiration for martyrdom which is promoted in various seductive depictions by the Iranian state. Varzi (Citation2006) states that the murals and images that populated post-war Iran turned the country into an ‘image machine’. War photography and the stream of images that appeared during the war contributed to this image machine and the visual culture of martyrdom that was portrayed by it. The IRNA’s war photographers, such as Ali Feridouni, Kazem Akhavan, Mehdi Mon’em, and Ahmad Nateqi were amateurs driven by their ideology and allegiance to the Islamic Revolution.

They were not professionals who were intent on reporting news; rather they reflected the tales of martyrs who were their fallen heroes. Pictures of combatants praying or occupied with rituals are familiar frames taken by these war photographers. For instance, Ali Ferydouni found recognition via images of a high casualty operation and said in an interview: ‘I was able to take my good and serious photos when we [Iranians] offered many martyrs.’Footnote5 His award-winning photographs of this operation are crowded with corpses, blood and gore. However, his photographs were type of frames that Iranian image machine and propaganda system found appropriate. These photographs were framed by the photographers’ religiosity and revolutionary subjectivity rather than their interest in portraying a war through a curious lens while calculating the depth of field, aperture and shutter speed. Therefore, the works of IRNA war photographers could be described as ‘the frame [that] takes part in the interpretation’ (Butler Citation2005).

The war photographers contributed to the production of the visual culture of martyrdom by framing and depicting fallen ones and combatants, as this resembled the master narrative of martyrdom in Shi’ism. The fallen bodies, severed heads, missing hands, bloodied foreheads and praying combatants resembled the stories of the battle of Karbala and the martyrdom of the prophet’s grandson and his disciples. This is not to imply a conspiracy but to highlight the impact of ideologically driven eyes behind the camera and expose their tensions with the eyes of beholders. The IRNA’s war photographers saw the frontlines not as the arena of combat between invaders and defenders of life and land but as the sacred realm where ‘Allah’s enemies’ threatened believers’ faith. Therefore, their work encouraged believers to embrace the grace of martyrdom in order to understand their work rather than view the fallen as those who had perished in the pages of history. I do not dwell on the histories and religiosity that stand behind these frames to concentrate on the counter-narrative in frames and step into the emergence of the visual culture in encounters with ‘everyday practices of seeing’ (Mitchell Citation2002: 170) that commemorate and advocate martyrdom.

I prefer to address the framed visual signifiers and their reception instead of stressing the embedded meanings in the frames by going back into Shi’i history and limiting myself to religio-cultural specificities. This means that I trace the production of a production and the emergent property of the network within which images circulate. In other words, the frame is the result of the circulation of an image and the way in which the content is presented by the photographer. Therefore, instead of asking what the frames do to people, I ask what people do with these frames via representation to highlight the circulation and importance of the reception of the frame within the limits of its circulation. In sum, a frame comes together by way of its production (see Reinhardt et al. Citation2007), reception (see Fetveit Citation2001), circulation (see Butler Citation2016) and the surplus of meanings (see Möller Citation2013). Such a path is taken to find a place for my ethnographic tales in between two major strands of reception studies. I neither see a framed visual signifier in the form of a text whose meaning could be decoded only by finding out the authorial intention nor follow the strand that turns to only finding meanings in the reception of a text through subject-centred descriptions.

Whose Frame is It Anyway?

Möller (Citation2013) proposes the reception of the frames according to the first and second moments of photographic reception. He suggests following the moments of viewers’ engagement with the frame in order to ask how they become ‘participant witness[es]’ (Möller Citation2013: 34). He suggests that ‘the second moment of photographic reception may, indeed, be more important than the first moment … tricking the viewer into patterns of inquiry … [that] may help to transform viewers into participant witnesses’ (Citation2013: 124). In such an approach, the workings of a frame are dependent on how the viewer receives the frame. Similarly, some theories in literary studies treat the text as an open structure that a reader would receive and engage with it. Iser (Citation1972) insisted that ‘a sense of the text is no longer regarded as authoritatively given [by the authors] but rather an open structure demanding understanding’ (Iser cf. Jauss Citation1992: 55) and that the readers would find their way towards the meanings via their own craft and imaginative devices. However, stressing such an open structure gets us closer neither to understanding how the viewers/readers receive the text/frame nor to learning how they are persuaded to receive the signification projected by the text/frame. In other words, it is not enough for visual anthropology to see how the viewers receive the frames, be it at the first or second moment; indeed, we need to go a step further and connect the modes of reception to the emergence of the frame – the emergence that occurs in the act of composition of a scene, the circulation of a frame across cultural variations and finally the encounter between a frame and the viewers. Therefore, any frame that carries semiotic contents, be they a text or an image, should neither be limited to the authors/photographers/composers/inventors of the frame nor be abandoned to those recipients/beholders/viewers who encounter the frame.

To follow the emergence of a frame, we should not assign the burden of meaning only to culturally situated individuals without considering how authorial intentions or propaganda guided the mode of receptions of individuals. Fetveit compares these strands of reception studies to encourage consideration of the reception of semiotic contents beyond the ‘claim that the text has no meaning other than those meanings actual readers make in their meeting with the text’ (Citation2001: 179). Simultaneously, it is not sufficient to find meanings in the fixed frame, compositions and texts that an author or a photographer has intended. The application of reception theories beyond literary criticism has been the concern of other disciplines such as history and sociology but not enough in anthropology. Thompson traces the application of these theories in the interpretation of historical meaning by encouraging a middle way between the two strands of reception theories. He states ‘It is not that if the one is correct, then the other must be false. This misrepresents the different insights which each offers’ (Citation1993: 272).

I consider the frame that emerges from authorial intentions, Iranians’ interpretations of those intentions and, finally, the surplus meanings that are the sediment of Iranian state propaganda and master narrative. Hence, I propose an ontology of frame that shows how the sociality of frames of the pains of non-combatants in Mon’em’s authorial intentions and Iranians’ reception of his project. The ontology of frame will prevent us from being blind to ‘the conditions of production’ (Hohendahl & Silberman Citation1977: 62) and disregards notions such as ‘There is no text, there is no audience, there is only the process of viewing’ (Fiske Citation1989: 57). I stress that the propaganda machinery of the Iranian state is central in bringing to the fore both the authorial intentions of war photographs and Iranians’ reception of them in the context of the visual culture of martyrdom. Thus, the wider aim of this article is to highlight the impositions of the master narrative via counter-narratives. In sum, Mon’em’s œuvre is explored with regard to the politics of war photography and the authorial intentions of his book. I then turn to the ethnography and discuss how Iranians received Mon’em’s photographs. I add my own ethnographic encounters to show how Iranians’ various modes of reception are influenced by and point at the visual culture of martyrdom.

The Pain of Others in the Frames of Mon’em

The master narrative of martyrdom has been regulated by the IR according to religious leaders’ reading of Shi’i history and religiosity. This singular reading of history imposes restrictions on socio-cultural and religious imaginaries and has succeeded in remaining the dominant discourse by suppressing any contestation through the state. Similarly, the visual culture of martyrdom has remained within the control of the state since the start of the revolution and the consolidation of Iranian political Shi’ism (Fischer Citation1980; Akhavi Citation1983; Arjomand Citation1986; Roy Citation1994). For instance, a media agency – Owj – directly associated with the Iranian revolutionary guard corps, controls the banners and media installations of all prime locations and main thoroughfares in most Iranian metropolises. This agency produces posters, banners, documentaries, animations, computer games and any form of media aligned with the propaganda and foreign policies that are encouraged by the Conservative Right in the Iranian state. All other agency either comply with their production style and agenda or are pushed out of the market.

The Owj agency is an example of the Iranian culture machine that disseminates a master narrative saturated by Shi’i history; accordingly, during the war, this master narrative determined the semiotic construction of war photographs. Mon’em, whose photography was celebrated during the war, has now been side-lined by the IR and cultural authorities. His publications, exhibitions and photographs are not sponsored by the IR, unlike many of his colleagues in the IRNA and are given minimal press coverage. Mon’em has turned his camera away from the master narrative to convey a counter-narrative that disturbs the regime of signification sanctioned by the IR. He began an unsponsored project 14 years ago in the western provinces of Iran, which Iraqi forces targeted with chemical weapons (CW) during the war.

His project focused on non-combatants who had no direct role in the war but who were injured because of exposure to CW at the time or to anti-personnel landmines after the war. Mon’em deems these non-combatants to be the ‘real’ victims of war in comparison with combatants who participated in the battle. He photographed women, men and children who lost limbs or eyes because of landmines – the lethal heritage of the war. Mon’em wrote in the statement for his recent photography exhibition ‘I am a photographer who began his work on the battlefields and I recall unpleasant memories of those days. But, I have encountered the bitter face of the war after its end. I have recorded some of them with my camera’ (2016, personal communication).Footnote6 He believes his work is not far removed from state policy and mentioned in an interview with Farsnews: ‘My work is aligned with the larger agendas of our country. However, we dislike encountering cautionary tales and we want to see pleasant stuff.’Footnote7 He points to the dominant narrative that concentrates on sacrality, heroism and martyrdom and categorises all of those killed in the war as martyrs, to deny the suffering inflicted by the war. However, Mon’em’s frames of suffering document ‘the victimhood of Iranians’.Footnote8 His photographs unsettle statesmen and warmongers who turned their backs on him because they insist on ‘divine victory’. He offered to exhibit his photographs of landmine victims in the Iranian parliament to increase awareness of the pain endured in border provinces. His offer was rejectedFootnote9 and the Minister of Culture and Islamic Guidance even told him that he needs to move on because ‘the time for such work has now passed’.Footnote10

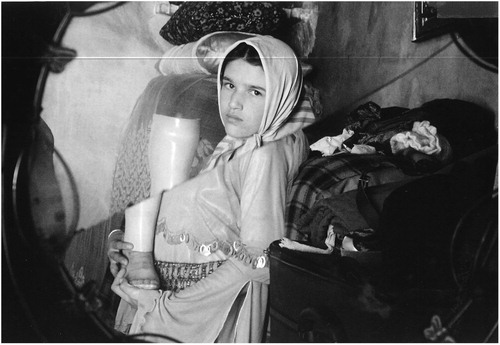

I explore Mon’em’s modes of framing not merely within War Victims but also in the trajectory of his work and the realities that he projects through his lectures, weblogs and posts on social media. Hence, I explain his photographic journey with an eye towards the politics that appear not in his photographic compositions but in the frames of his work. He follows victims and enters into their lives like an ethnographer. He engages with them beyond his photographic composition and even remains in touch with them for many years. Mon’em broadens the story of those in front of his camera beyond the presented frames. One example of this is the tragedy depicted in one his photographs () showing a seven-year-old girl who lost her leg as she played outside and stepped on a landmine. Initially touched by the image, I was disappointed because I felt that he had tried to frame only her suffering and reduce her to a mere victim, particularly because he photographed her reflection and her sorrowful eyes through a cracked mirror rather than photographing the girl herself. His composition echoed Bal’s claim (Citation2007) that the framed pain of others disturbs their subjectivity or Reinhardt’s (Citation2012) strong disagreement in that he finds the aesthetic presentation of the pain of others to be essentially ‘mistreating the subject and inviting passive consumption … or even sadism on the part of viewer’ (Citation2012: 34). However, I later realised while following him beyond WV that, in his photo-blog, he had placed that 2005 photograph next to a 2013 photograph of the same girl, by then a beautiful woman pursuing higher education in law with the goal of taking landmine manufacturers to court.Footnote11

Mon’em portrays pain, not martyrdom; he neither refutes nor complies with the master narrative. Consequently, he is not as celebrated or supported as his other brethren behind the camera. Mon’em breaks with romanticised, mystical notions of martyrdom by turning the pain that is overshadowed by the blood of martyrs and the governance of death into a living reality that demands attention. He offers pristine black and white compositions that bear the imposed silenced through the plentitude of negative spaces in frames that speak of life lived despite the pains endured every day. The recurring lost limbs and banal composition stress the agony of a war that has apparently ended but which has actually remained unfinished for many in the Iranian borderlands.

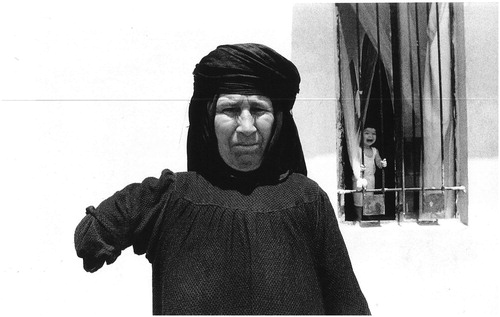

I noticed that he specifically intensifies the sense of despair through the gaze of others or some unexpected elements in the background in WV. The ‘victims’ are placed in the frame’s centre foreground, holding a prosthetic hand or leg while another pair of eyes unsettles the frame. These elements direct ‘the intensity of presentational form – the fragments of experience, reality, happening (whatever you want to call it) contained through framing’ (Edwards Citation2001: 17). ‘Victims’ remain in the depths of the field; their sharp and in-focus presence restrains imaginative interpretations and story-making beyond what the frame conveys.

An old woman, amputated hand clearly visible and wearing Kurdish attire, stands in the centre of the frame while a child cries behind a window, holding its iron bars. The latter appears to be trying to reach out towards a white over-exposed foreground and to escape the black abyss of the background (). Mon’em puts across his notion of suffering and despair by including ordinary elements to add metaphors and guide the viewers’ eyes, normally immersed in the bloody and gory images of martyrs, with different modes of visual composition.

Figure 5. The victim’s canted frame and the crying child that appears like a telling metaphor. © Mone’m.

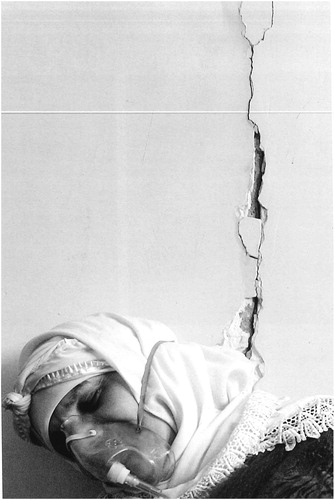

Mon’em’s frames challenge the critique of those such as Strauss (Citation2003) who condemns war photography and the photography of the pain of others in general with accusations of the aestheticisation of politically charged subjects. Mon’em’s aesthetic presentation of the pain of others works against decades of brute framing of the blooded corpses and crushed bodies of combatants. He returns to aesthetics in collaboration with the subjects, who offer their subjectivities to be framed in order to present a counter-narrative to what the state propagates. That is to say, the option ‘not to aestheticise does not exist’ (Möller Citation2013: 39) for Mone’m and striving for representation is the only mode of crafting a counter-narrative for him. His photograph () of Zeynab, who was exposed to CW during the war and suffers from respiratory problems, exemplifies his inclusion of metaphors. Mon’em photographed her as she slept, leaning against a wall. She is wearing an oxygen mask but the outline of her tilted head is a continuation of a deep crack in the wall. He uses the crack to reflect the pain that shattered the smooth surface of a life that, before the war, did not need assistance to simply breathe. Mon’em plainly writes in the caption: ‘One of her daughters died due to the severity of the damage. Her husband, too, passed away in 2006 from injuries caused by a chemical reaction (sic)’ (Citation2015: 129.). His simple statement is beyond the epistemological coherence that the state’s propaganda encourages. Mon’em offers no sacrality, poetics or glory to death but rather tries to let the pain of the woman remain apparent via a frame captioned with the simplicity of death and nothing else.

Overall, Mon’em attempts to avoid freezing the lives of people in front of his camera in their framed pain by capturing the flows of life. This is apparent to anyone who follows his work beyond the limits of WV and sees it in the context in which Mon’em, the war photographer, is placed. However, the question is why Mon’em does not include in his book War Victims the photograph of the girl who has grown into a blossoming law student or the smiling father who shares his jubilance with his son. Why does he include them and share them on his personal weblog but excludes them from his book? I wonder why Mon’em intensifies the sense of despair and suffering in the book and why he turns away from photographing the victims’ resilience in order to ‘appeal to the humanity of those in war rooms’.Footnote12 WV frames the non-combatant he photographed within the limits of victimhood and suffering, unlike his usual approach in his online activities. I detected a threshold of change in Mon’em’s work which appeared after he presented his 14-year-long project at the International Court in The Hague. His presentation was a reaction to the Iranian cultural authorities’ lack of interest and support. The Dutch representative to the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) told him that ‘These photographs are proof of the suffering of Iranians during the war. The photos expose the oppression inflicted on Iranians.’Footnote13 The Dutch representative promised support for the publication of Mon’em’s book and the ICRC logo appeared on the cover. Mon’em juxtaposed his frames within the discourse of victimhood to secure the support and attention of international bodies such as the ICRC.

The book is an example of the tension woven into the imposing politics of suffering and fluid notions of pain. The IR places the pain of non-combatants and combatants within a singular framework of suffering. There is only one narrative that defines anyone impacted on by the war. A woman, a man or a child killed in the war is as much a shahid (martyr) as a combatant killed in action. The industry of suffering in Iran is represented through a visual culture that conveys the master narrative, which begins and ends with martyrdom and remains in denial of death. Mon’em challenges the master narrative by avoiding the language of martyrdom but he employs ICRC-supported notions of victimhood in his book, only to return to narratives of pain and resilience in his photo-blog. The oscillation of ideas between war photographers, viewers, the Iranian state and international organisations (in the case of Mon’em) produces the representation and narration of the pain of others and shapes the politics of visual representation of ‘war victims’. It is through this oscillation that the frame emerges – the frame that is the emergent property of the assemblage of the multitude of components that bring about the visual culture of martyrdom.

Looking Through the Framed Pain

I found the opportunity to conduct fieldwork and explore receptions of Mon’em’s work while I was employed in Khuzestan. I worked as a documentary photographer there at the request of a few veterans who organised pilgrimage caravan trails to the Iranian frontiers. The Iranian state has turned the southern frontiers and former combat zones into pilgrimage sites. I was asked to compile a photo-documentary about the caravans while they toured these former combat zones and paid their respects to the fallen. My camera and the responsibility of ‘documentation’ enabled me to interact with men and women of different ranks and standing, all temporarily living in caravans. I used the opportunity to look through WV with them, observed their emotional reactions and asked their opinions about the photographs. Haj Jafar, a war veteran in his mid-sixties and retired from his position as a major in the revolutionary guard, demanded to see WV after he overheard my conversations with the young volunteers. He was the guide for the caravans and shared war stories of the courage and piety of martyrs. He saw the martyrs as exemplars of salvation and purity and was renowned for his ability to elicit tears and strong emotional responses from his audience through narratives of martyrdom. Some called him a master of tears, more as an honour than in humour.

His demand to see WV concerned me because he could have stopped me from pursuing my research further. He sat calmly next to me in the tour bus, looked through each photograph, read the captions attentively and said: ‘They are khafeh-shodeh (suffocated) portraits of the wounded. There is no reality in them.’ Amazed, I replied, ‘This is the reality as it exists in the border provinces. These are people who lost hands, legs and eye-sight. What else is their reality?’ Agitated, I pressed him further: ‘How are they suffocated? They are just bare tales of the pain of others.’ He replied:

Just look through it and you find more women and children in WV. The photographer wants to provoke pity. We are not a pitiful nation. We offered martyrs and stood behind our leaders. We found the path of salvation by following them. These photographs humiliate us.

Oh that? Look at them. Martyrdom aside; just look at them. Every photo shows someone with an injury and sorrow. These photos are inappropriate. It is not appropriate to show someone holding their prosthetic leg or standing next to it. There is no dignity in the photographs.

Haj Jafar walked away and I saw the ghost of photography critiques standing by him. Rancière (Citation2009), Bal (Citation2007), Dyer (Citation2007) and others suggest that the photography of political violence restrains the individual in front of the lens as ‘they are reduced to their dignity’ (Dyer Citation2007: 103). Struk (Citation2011) articulates this more anthropologically while questioning the genre of war photography and why it has not treated photographs taken by soldiers as the realities of war (Citation2011). She stresses that, in war photography such as Mon’em’s, the victims are portrayed as passive and devoid of agency. I would agree with her in a world without politics and limited to the poetics, but visual anthropology requires us to follow the frame beyond the rectangular phenomenological appearance of a photograph.

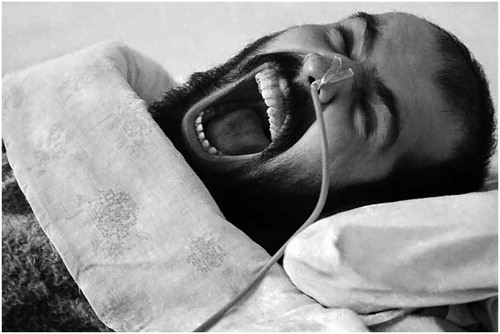

Haj Jafar returned to me few days later and handed me his smart phone. He asked me to google Mon’em for him – in other words, the photographer who had dared to publish such an insulting book in the Islamic Republic. I showed him Mon’em’s blog and, a few minutes later, his eyes were red and tears were rolling down from his eyes. He was stuck on the picture of a wounded veteran () known as ‘sleeping beauty’.Footnote14 The veteran was stricken by the impact of a high-intensity explosion and fell into a coma for 18 years, just waking every now and then to scream before falling back into his coma while tears streamed down his face. This is a well-known story in the circle of veterans but Haj Jafar shared trenches with the sleeping beauty and recalled many stories about him. Haj Jafar struggled to close the google page while murmuring ‘These are evidence of victimhood,’ without noticing my surprise and the fact that I could speculate that he would see the book now in a different light. It was the frame that emerged beyond the book published by Mon’em, the frame which captivated Haj Jafar, who preferred the victory narrative of martyrdom to the narrative of suffering of victimhood. The frame emerged not in Haj Jafar’s reception of the photographs nor in Mon’em’s authorial intentions but in the wider circulation of the frame across the visual culture that is contested by the state and those who encourage counter-narratives against state-sponsored propaganda.

Haj Jafar was not the first person I spoke to but his opinion summed up what I heard from many. Most reacted negatively toward the photographs. For instance, Saïd, who was studying cinematography at a prestigious art school, said ‘These are unnecessary frames of suffering.’ I frowned in response and he continued, ‘Every war has casualties but our history should not be documented only through them.’ I explained how Mon’em documents the side of history that is less documented but he interrupted,

You are right but he has not maintained any balance. He could show the martyrs and non-combatants but, instead, he just fills the book with photographs that make viewers feel sorry for us … I think his ideology and his personal issues are stopping him from being objective. He is in his frames.

There were others who were less eloquent than Saïd. A few times, Amin, an energetic and passionate revolutionary man in his early twenties, insisted that WV only shows the dark face of the war rather than its reality. Amin was from Qum, the city known for its conservative atmosphere and he was not shy in expressing his strong belief in martyrdom and the IR’s propagated values. He stressed that the war was the occasion for reaching salvation and that we need to depict martyrs in this way rather than as suffering. I then asked how one should frame and photograph landmines and the crisis at hand. I showed him Mon’em’s interviews in which he mentioned that the crisis is so dire that anyone could end up in a hospital at any time because landmine explosions are so frequent in the border provinces.Footnote15 He said,

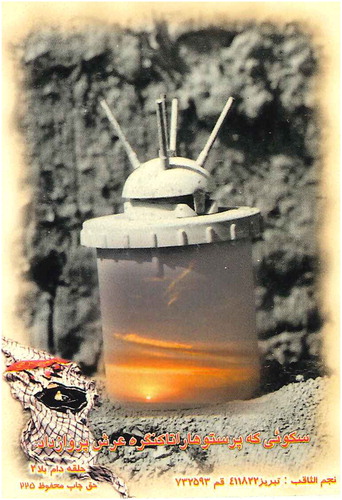

I don’t know how to say it but there is something wrong with these photographs. They are too sad to be believable. Our martyrs used to call the Valmara 69Footnote16 the Italian bride because it was their Sakooye Behesht (step to heaven).

Figure 8. Valmara 69, the lethal landmine that is supposed to be the step to heaven. © Najm Desginers.

There was an emotional resistance against Mon’em’s photographs. Many of those who were committed to the Islamic revolution found the photographs, on the one hand, unaligned with the regime of signification that they have accepted as their way of seeing martyrdom. On the other hand, they found that the counter-narrative implied within the photographs went against the representations that they preferred to perceive of themselves and of martyrs. They insisted on not-being-victims and thus they refused the counter-narrative as having no consideration for non-combatants and silenced voices. However, there were moments, like the story of Haj Jafar, when the viewers were unsettled because they saw beyond the book and the inconsistencies and oscillations of the frame challenged their perceptions.

I spoke with only three women because of the restrictions of the women’s dormitory being separate and female volunteers maintaining constant barriers between men and women. I spoke to Khadijah, who pointed to a picture of an old woman who died because of CW injuries when I asked which photograph she finds intriguing. She said ‘At least a red death is better than just dying in bed.’ Shocked, I responded ‘She could not breathe without a mask for years and then passed away. How is that a red death? It is years of pain!’ As she walked away, fixing her hijab firmly, she replied: ‘Pain is good; pain gives meaning. You think pain is suffering. That’s why you cannot see the depth of her death.’ Khadija did not find the photographs of living appealing enough but those of the dead were ‘admirable’. There was nothing unusual in her choice because it complied with the regime of signification that masks the pain within the sacrality of martyrdom. Others, like Khadijah, saw a depth in death because the visual culture of martyrdom translates death into a glory and grace that cannot be found in living, let alone living in pain and suffering.

Iranians who had no allegiances to the Islamic revolution reacted very differently to WV. Most Iranians in Europe –where I spoke with political asylum-seekers about the book – blamed Iranian religious leaders’ ideology and revolution for the war and Iranians’ suffering. This was a view shared by many other Iranians. The reactions of Iranian refugees I met in centres in Amersfoort (the Netherlands), Bramsche and Bielefeld (Germany) were, at first, political and then emotional. Mariam, who had run way from Iran after Ahmadinejad’s campaign against Christian evangelists, explained to me that the war was prolonged because Khomeini wanted to propagate his religious agenda. She said, ‘Naturally, Iraq would retaliate. I am not saying Saddam needed to use CW or landmines but this is the natural progress of any war. Tit for tat.’ She looked through WV with more attention and said,

I don’t have an ideal life. Just look around. My life is limited to the refugee centre but I feel their pain and want to cry. They are really strong photographs that tell the truth. Their suffering never ends. I become grateful for my shitty life when I see their suffering.

Soma, a young Iraqi teenager who lived next door to Mariam, passed us and asked if she could look at WV. She carefully studied the photographs, lingering on each page for a minute or two before saying ‘I want to take such photographs. They are so alive and beautiful.’ Mariam was surprised. ‘Beautiful? What is wrong with you? This is the atrocity that Iranians suffered because of the war and I am not saying that because you are from Iraq.’ Soma calmly apologised, ‘I don’t mean to diminish the catastrophe or their pain but I mean that they are aesthetically beautiful. Look at the black and white tones. Look at the way the children are framed.’ Soma became quiet and handed me the book. She looked at Mariam while pointing at the refugee centre. ‘We both suffer in this madhouse. We have similar issues but photography has kept me sane. I don’t care about the content … the form matters to me, the skill of the photographer matters to me and not the story told.’ Mariam, who is far older than Soma, seemed convinced; ‘These photographs convey a political message.’ Soma’s reply was sharp,

Of course not, they are just photographs. Tell me what can we do about it? Absolutely nothing. They are just stories. We look at them and we feel bad about the people in the frame. But we cannot do fuck about it. At least, I try to find an artistic value in them instead of becoming emotional.

My conversations with other Iranians who did not subscribe to the rhetoric of martyrdom followed similar patterns. Most of them recognised the photographs within the frames of suffering and never mentioned anything about martyrdom or heroism. My conversation with Parisa, a student of sociology at Bielefeld University (Germany) in her late twenties, added new patterns to the conversation. She was born in Iran of an Iranian mother and an Afghani father whose precarious situation helped them to take refuge in Germany. I was invited to their home to explore Mon’em’s book with them.

Parisa’s mother was a nurse during the war and had seen the troubles of war as a medical worker; her father experienced the violence of war directly before seeking refuge in Iran and later in Germany. Parisa and her husband had spent their childhood in Iran during the war and were familiar with the propagated regime of signification. I was in a home where opinions about war and violence were plentiful. Macabre feelings overwhelmed the room as WV was handed around while dinner was served. Parisa’s father spoke first, ‘These photographs are nothing special to my eyes. These are the frames that many Afghans have lived through and grew up with. I have seen worse.’ Then, Parisa’s mother, who seemed affected by WV, added ‘Yes, but our war was different. We did not shoot at each other.’ Parisa’s father immediately reacted; ‘Iranians talk as if they are the only ones who have suffered and encountered war and invasion. Afghans have not had one day of peace in many decades.’ Parisa turned to me while her parents debated whose suffering was worse and said ‘I must say that I am impressed by WV but I suggest that you look through the photographs instead of looking at them.’ She seemed more curious to find out about the photographer beyond the frames of photographs before sharing her opinion within the limits of what WV revealed to her. The conversation in Parisa’s home recalls the dilemma that Eco encountered in proposing a distinction between the use and the interpretation of a text (and, in this case, images) to strike a balance between the authorial intention and readers’ interpretation of it. Parisa’s father, like Mariam, used the photographs and the pain of others to authenticate their own pain and then interpreted them accordingly. Thus, Eco stresses ‘It is very hard to keep the boundaries between use and interpretation’ (Citation1990: 162). However, Parisa preferred some symbolic closure via authorial intentions to be able to find meanings in the framed pain of others. The receptions of the framed visual signifier are better seen through the movement of recipients between what is in the frames and how they use them to perceive networks of reality around them.

The pain of others within Mon’em’s photographs was a political matter for the Iranian political asylum-seekers with whom I spoke. They turned away from the regime of signification and the shadows of politics were more visible than anything else for them. However, one man stood apart when we looked at WV together. Ahmed had a different reaction. I pursued him, in particular, and finally found a chance to talk to him because he drew much attention to his and other Iranians refugees’ troubles at the Greece–Macedonia border. He sewed his lips closed in protest at the fences that Europe was erecting against refugees and the hierarchies of suffering Europe was creating among refugees. He left because of the troubles that the IR brought on the mystic Sufi order to which he belonged in Kurdistan. He wept while looking through the photographs, as if Mon’em’s authorial intentions reached him – I wondered if his troubles had made him sensitive to the pain of others. However, the regime of signification spoke through him differently. He said ‘These are shahidan zende (living martyrs). They are the ones who embody the grace of martyrs everyday.’ He traced the outline of faces in the frames and said ‘I envy their dignity … they have turned pain into the dignity of lives.’ I asked what he meant by martyrs and whether he did not think that their sufferings are due to the interests of the Iranian state from which he had run away. He stressed

Let aside politics, I am a refugee because of the warmongers who caused suffering, but we are more than that. The pain becomes yours after all the suffering is inflicted. The martyrdom is yours even if you are led into it by evil. They cannot take that away from you.

Ahmed spoke of the pain of others with the vocabulary that the regime of signification uses to speak of martyrdom across Iran in various ways, including representations through the visual culture of martyrdom. However, he borrowed the language to express the mystical teachings of his own order, which promote any pain as a way of purification. His reception of the photographs was not affected by the master narrative but remained influenced by it. The authorial intentions of Mon’em, the language of propaganda and his mystic-religious subjectivity all lead him to a frame that is neither dictated by WV nor entirely culturally-politically situated. He resonates with the office-goer that I asked him to imagine; he is neither numb nor de-sensitised nor in compliance. He finds meanings in the shadows of the visual culture of martyrdom, where he can see martyrdom-in-itself regardless of the politics that overwhelm the concept. Of the 10 Iranian refugees with whom I spoke, Ahmed was just one who expressed such a different response. However, there may well be others who think in a similar way, which would imply the need for further research.

Concluding by Looking at the Pain of Others

Mehdi Mon’em was not pleased when I asked permission to use his photographs in this article. My outright assertion that I did not intend to look at the aesthetics of his work disturbed him. He said ‘You want to look at my work by way of ehsas (feelings).’ However, he granted me permission when I explained my idea about the politics of visual culture. Thus, I drew together the tale of Mon’em beyond his book, the reactions of committed Iranian revolutionary youths and the refugees to highlight the challenging terrain of framing the pain of others somewhere between authorial intention and the ways in which the viewers/beholders receive it.

I sought out the Iranian visual culture of martyrdom in this article in order to demonstrate the polyvalence of photographs according to the impositions of the regime of significations. The visual culture infused with certain significations persuades viewers to receive photographs in a specific mode, aligned with the master narrative, be it refusal or agreement. Some viewers abide by the imposed signification and limit their view to the defined categories of the visual culture of martyrdom; others dismiss them and impose their own political subjectivity. Viewers such as Mariam and Parisa’s father bring their pain to the frames in order to comprehend or articulate the pain of others. However, their modes of viewing were linked to the ways which Mone’m had composed his photographs. Therefore, the frame must be seen beyond the rectangular fixture that conveys the semiotic contents. The frame is an emergent property of circulation, of in-betweenness and the travels of the content and the intentions. Consequently, the reception of the frame should be decontextualised from its culturally specified meanings and, instead, should be traced in the yo-yo movements of icons, symbols, metaphors, the gaze of viewers, the intention of the authors, the politics of the state, the poetics of time and even the advancement of photographic equipment, social media and print culture.

To a great extent, the visual culture of martyrdom remains almost uncontested in Iran. Alternative voices, such as Mon’em’s, have very little opportunity to emerge and express their counter-narratives to challenge the master narrative. They are pushed to the margins to such an extent that they would mould their photographs and juxtapose their frames as a way of attracting support from international organisations. Therefore, one should seek these rare counter-narratives to highlight the workings of master narratives in light of both their dismissal and of confirmation of alternative voices. Such an approach encourages an ontology of frame by asking how we chase the possibility of the frame, what the elements are that the frame is contingent upon and, finally, how a frame has found its way into the semiotic content and ways of seeing. Therefore, visual anthropology would be able to address how the political subjectivities of victims and viewers are entangled in the emergence of the frame and how that entanglement can become an arena of reflexivity, resistance, dialogue and stepping towards changing the ways of seeing. I end with an enchanting line from the late Sohrab Sepehri, a renowned Iranian poet, who said: ‘Eyes must be washed, the way of seeing must be changed, the word must be washed … the word must be the rain itself.’Footnote17

Acknowledgments

This article is the expression of my admiration for non-combatants of the Iran–Iraq war who were affected by Chemical Weapon bombardment and still carry the pain of the eight-year war. Also, many thanks for the patience and suggestions of Dr Freek Colombijn, Dr Ton Salman, two anonymous reviewers and Academic Freedom Initiative of Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam that supported my research generously.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

ORCID

Younes Saramifar http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8553-4463

Notes

1. http://www.wisgoon.com/pin/6773035/ (accessed 13 January 2017).

2. All the captions below the figures are the author’s.

3. This usually falls in mid-March until the first half of April, according to the Gregorian calendar.

4. https://www.navytimes.com/story/military/2016/01/14/us-sailors-mistakenly-steered-into-iranian-waters/78796140/ (accessed 13 January 2017).

5. http://www.tasnimnews.com/fa/news/1394/07/13/877777 (accessed 17 August 2016, emphasis added).

6. I often translate the statements that Mon’em prepares for his exhibitions as a way to express my gratitude for his permission to use his photographs in my articles.

7. http://www.farsnews.com/newstext.php?nn=13920613000306 (accessed 17 August 2016).

8. http://www.farsnews.com/newstext.php?nn=13920613000306 (accessed 17 August 2016).

9. http://www.farsnews.com/newstext.php?nn=13920613000306 (accessed 17 August 2016).

10. http://monem.akkasee.com/20171/plist/33 (accessed 17 August 2016).

11. http://monem.akkasee.com/20100/plist/48 (accessed 17 August 2016).

12. http://www.farsnews.com/newstext.php?nn=13920613000306 (accessed 17 August 2016).

13. http://www.siasatrooz.ir/vdcg7y9t.ak9qn4prra.html (accessed 17 August 2016).

14. http://monem.akkasee.com/20241/plist/21 (accessed 25 October 2017).

15. http://www.farsnews.com/newstext.php?nn=13920613000306 (accessed 17 August 2016).

16. Valmara 69, an Italian anti-personnel landmine, was used frequently in the Iran–Iraq war. This lethal mine is placed in a web and connected with wires to other mines. Triggering one of them causes the rest of the connected mines to explode and creates many more casualties than an average SB-33 mine. For further information see Hidden Death: Land Mines and Civilian Casualties in Iraqi Kurdistan, a Landmine Monitor Report 1999: Toward a Mine-free World, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4pdghyf-ZUs.

17. http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/sepehri-sohrab (accessed 25 October 2017).

References

- Akhavi, Shahrough. 1983. The Ideology and Praxis of Shi’ism in the Iranian Revolution, Comparative Studies in Society and History, 25(2):195–221. doi: 10.1017/S0010417500010409

- Arjomand, Said Amir. 1986. Iran’s Islamic Revolution in Comparative Perspective, World Politics, 38(3):383–414. doi: 10.2307/2010199

- Bal, Mieke. 2007. The Pain of Images. In Beautiful Suffering: Photography and the Traffic in Pain, edited by Mark Reinhardt, Holly Edwards & Erina Duganne, 93–115. Williamsburg/Chicago: Williams College Museum of Art/The University of Chicago Press.

- Bal, Mieke & Norman Bryson. 2001. Looking in: The Art of Viewing. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Barthes, R. 1971. From Work to Text. In The Novel: An Anthology of Criticism and Theory, 1900–2000, edited by Dorothy J. Hale, 236–241. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Berger, J. 2008. Ways of Seeing (Vol. 1). London: Penguin.

- Butler, Judith. 2005. Photography, War, Outrage, PMLA, 120(3):822–827. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25486216 doi: 10.1632/003081205X63886

- Butler, Judith. 2016. Frames of War: When is Life Grievable? New York: Verso.

- Chelkowski, Peter & Hamid Dabashi. 2001. Staging a Revolution: The Art of Persuasion in the Islamic Republic of Iran. New York: New York University Press.

- Culler, Jonathan. 1992. In Defence of Overinterpretation. In Interpretation and Overinterpretation, edited by Stefan Collini, 109–123. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Dauphinée, Elizabeth. 2007. The Politics of the Body in Pain: Reading the Ethics of Imagery, Security Dialogue, 38(2):139–155. doi: 10.1177/0967010607078529

- Dyer, Geoff. 2007. The Ongoing Moment. London: Abacus.

- Eco, Umberto. 1990. The Limits of Interpretation. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

- Edwards, Elizabeth. 2001. Raw Histories: Photographs, Anthropology and Museums. Oxford: Berg.

- Ehsani, Kaveh. 2017. War and Resentment: Critical Reflections on the Legacies of the Iran–Iraq War, Middle East Critique, 26(1):5–24. doi: 10.1080/19436149.2016.1245530

- Farhang, Mansour. 1985. The Iran–Iraq War: The Feud, the Tragedy, the Spoils, World Policy Journal, 2(4):659–680.

- Fetveit, Arild. 2001. Anti-essentialism and Reception Studies: In Defense of the Text. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 4(2):173–199. doi: 10.1177/136787790100400203

- Fischer, Michael M. 1980. Iran: From Religious Dispute to Revolution. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Fischer, Michael M. & Mehdi Abedi. 1990. Debating Muslims: Cultural Dialogues in Postmodernity and Tradition. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Fiske, John. 1989. Moments of Television: Neither the Text nor the Audience. In Remote Control: Television, Audiences and Cultural Power, edited by Ellen Seiter, Hans Borchers, Gabrielle Kreutzner & Eva-Maria Warth, 50–78. London: Routledge.

- Gilman, Daniel. 2015. The Martyr Pop Moment: Depoliticizing Martyrdom, Ethnos, 80:692–709. doi: 10.1080/00141844.2014.938676

- Hohendahl, Peter Uwe & Marc Silberman. 1977. Introduction to Reception Aesthetics. New German Critique, 10(1):29–63.

- Ingold, Tim. 2012. Toward an Ecology of Materials. Annual Review of Anthropology, 41:427–442. doi: 10.1146/annurev-anthro-081309-145920

- Iser, Wolfgang. 1972. The Reading Process: A Phenomenological Approach, New Literary History, 3(2):279–299. doi: 10.2307/468316

- Iser, Wolfgang. 1978. The Act of Reading: A Theory of Aesthetic Response. Baltimore/London: The John Hopkins University Press.

- Jauss, Hans Robert. 1992. The Theory of Reception: A Retrospective of its Unrecognized Prehistory. In Literary Theory Today, edited by Peter Collier & Helga Geyer-Ryan, 53–73. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Khosronejad, Pedram. 2012. Iranian Sacred Defense Cinema: Religion, Martyrdom and National Identity. London: Sean Kingston Publishing.

- Khosronejad, Pedram. 2013. Unburied Memories: The Politics of Bodies of Sacred Defense Martyrs in Iran. London: Routledge.

- Kleinman, Arthur. 1992. Pain and Resistance: The Delegitimation and Relegitimation of Local Worlds. In Pain as Human Experience: An Anthropological Perspective, edited by Mary-Jo DelVecchio Good, Paul Brodwin, Byron J. Good & Arthur Kleinman, 169–197. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Machor, J.L. & P. Goldstein (eds). 2001. Reception Study: From Literary Theory to Cultural Studies. Psychology Press.

- Metz, Christian. 1985. Photography and Fetish, October, 34:81–90. doi: 10.2307/778490

- Mitchell, William John Thomas. 2002. Showing Seeing: A Critique of Visual Culture, Journal of Visual Culture, 1(2):165–181. doi: 10.1177/147041290200100202

- Möller, Frank. 2013. Visual Peace: Images, Spectatorship, and the Politics of Violence. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mon’em, Mehdi. 2015. War Victims 2. Iran: Self-published.

- Rancière, Jacques. 2009. The Emancipated Spectator, translated by G. Elliott. London/New York: Verso.

- Reinhardt, Mark. 2012. Painful Photographs: From the Ethics of Spectatorship to Visual Politics. In Ethics and Images of Pain, edited by Asbjørn Gronstad & Henrik Gustafsson, 33–56. New York: Routledge.

- Reinhardt, Mark, Holly Edwards & Erina Duganne (eds). 2007. Beautiful Suffering: Photography and the Traffic in Pain. Williamsburg/Chicago: Williams College Museum of Art/The University of Chicago Press.

- Rigney, Ann. 2005. Plenitude, Scarcity and the Circulation of Cultural Memory, Journal of European Studies, 35(1):11–28. doi: 10.1177/0047244105051158

- Roy, Olivier. 1994. The Failure of Political Islam. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Saramifar, Y. 2016. The Bodies Who Tell Stories: Tracing Deleuzian Becoming in the Auto/Biographies Iranian Female Refugees, Prose Studies, 38(3):205–219. doi: 10.1080/01440357.2016.1267014

- Sontag, Sonta. 1990. On Photography (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1977). New York: Anchor-Doubleday.

- Strauss, David Levi. 2003. Between the Eyes: Essays on Photography and Politics. Aperture.

- Struk, Janina. 2011. Private Pictures: Soldiers’ Inside View of War. London/New York: I.B. Tauris.

- Thompson, Martyn P. 1993. Reception Theory and the Interpretation of Historical Meaning, History and Theory, 32(3):248–272.

- Varzi, Roxanne. 2006. Warring Souls: Youth, Media, and Martyrdom in Post-Revolution Iran. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.