ABSTRACT

Korowai of Indonesian Papua have shifted their political order from rejecting relations of authority, to actively subordinating themselves to government patrons and implementing state structures locally. This shift was caused by how internal complexities of the past Korowai egalitarian system have interacted with dramatic macrostructural changes in the intruding state. Previously, I linked Korowai ideas about opacity of minds to political egalitarianism. Analyzing the new political shifts here, I emphasise again how opacity doctrines are embedded in wider processes of exchange and kinship that involve attributing thoughts to others, trying to influence those thoughts, and trying to deal in egalitarian ways with unequal economic conditions, as well as with the intrinsically power-laden dynamics of intersubjectivity itself. The Korowai example suggests wider lessons in how state formation takes hold at extreme colonial and market peripheries, and how doctrines of the knowability of minds articulate with practical institutionalisation of state administrative hierarchy.

Introduction

The question of government and mental opacity sits within a larger question of government and consciousness. Buitron and Steinmüller in their Introduction to this issue identify Scott’s category ‘legibility’ as a useful resource for bridging statecraft and knowledge of minds. A complication is that Scott’s analysis of modernist planning was not focused on consciousness. Scott (Citation1998) describes governments as concerned with the legibility of how populations materially live, and only indirectly with their thoughts. Relatedly, the processes he describes are top-down.

Modernist planning’s failures are widely criticised by policy workers themselves, not just academics. Two common responses today are ‘decentralization’ and ‘community-driven development’, both rationalised as better aligning ruling institutions with consciousness of the ruled. These policies even aspire to foster upward influence: peripheral citizens will shape government to their needs. Yet in reality, these trends often fail to improve the lives of the governed (e.g. Dasgupta and Beard Citation2007; Grossman and Lewis Citation2014). Extending Scott’s pessimism, and in the spirit of Foucault’s influential idea of governmentality, we could hypothesise that these programmes just go a few steps further down the same path as modernist planning. Decentralisation and community-driven development simplify populations in ways legible to the state, by reshaping people’s practical activity and thought into the very form of that state.

Among all countries, Indonesia is probably where decentralisation and community-driven development have been instituted most intensely and on the greatest scale. The most extreme implementation has been in Papua, at the country’s eastern limit. Coincidentally, Papua is also a region where many people disavow being able to know others’ thoughts. In my earlier contribution to a discussion of Melanesian cultural emphasis on the ‘opacity of other minds’ coordinated by Rumsey and Robbins (Citation2008), I drew on fieldwork with Korowai of Papua to suggest that disavowing knowledge of others’ thoughts may often be linked to valuing autonomy (Stasch Citation2008). When Korowai refuse to speculate about what someone else is thinking or planning by saying ‘She has his own thoughts!’ or ‘It’s not as though we share the same mind!’, the response is simultaneously epistemological and political. It affirms others’ authority to decide and speak for themselves.

Papua is Indonesia’s poorest region, and Korowai live at an outer edge of that region’s administrative, transport, and market networks. Korowai have recently undergone a drastic change in the political order, within the state environment of decentralisation and community-driven development.Footnote1 Where Korowai a generation ago rejected all authority relations, by the late 2010s they were participating enthusiastically in local state formation, subordinating themselves to distant government patrons, and instituting divides of ruler and ruled among themselves.

In this article, I examine this change to make three simultaneous contributions. One is an account of how decentralisation and community-driven development can unify government and local consciousness. Ethnographic examination of just one setting may broaden scholars’ imaginations about the practical life of these global organisational trends. The changes that have rippled across Papua in particular due to these policies are barely known in international academic literature (with exceptions touched on below). I thus hope to add to the visibility of this regional transformation, particularly as experienced by people on the rural periphery.

A second contribution concerns the pattern that the new alignment with state order is a result of Korowai making themselves legible. This is puzzling, since their past ethos of rejecting relations of authority meant Korowai closely matched typifications of anti-state anarchists advocated by Clastres (Citation1977), Graeber (Citation2004), and Scott (Citation2009). Those models predict that Korowai would flee the state, so how can their recent political trajectory have instead been enthusiastic embrace of it? My answer involves tracing how internal complexities of past Korowai egalitarian political sensibilities have paradoxically fuelled the move toward authority structures. Here my account joins wider literature documenting how state power often grows from extra-state dimensions of local social life (e.g. Sykes Citation2001; Jorgensen Citation2007; Timmer Citation2010; Street Citation2012; Jansen Citation2014; Oppermann Citation2015; Herriman and Winarnita Citation2016; Tammisto Citation2016; Schwoerer Citation2018; see also Stasch Citation2021, a companion piece to this article).

Third, I try to advance understanding of the relation between political order and knowing others’ mental intentions. Buitron and Steinmüller suggest that forms of government correlate with doctrines of mental opacity or legibility. Writing about another part of Indonesia, Donzelli (Citation2019) has demonstrated that decentralisation and a burgeoning neoliberal NGO sector can foster shifts in popular models of subjectivity, including a shift from routine disavowal of personal agency to routine profession of ‘dreams’, ‘hopes’ and ‘aspirations’ (see also Buitron’s article in this issue). Researching Korowai political change, I have so far not seen correlations like this, or even been able to isolate opacity ideas as a self-contained trait that could be correlated with other variables. My earlier article did present a kind of correlation between opacity ideas and a political ethos of egalitarian autonomy, but I also described Korowai opacity statements relationally, as part of an overall political and epistemological dialectics that included attributing mental states to others, and regularly impinging on others in autonomy-violating ways.Footnote2 My suggestion here will be that understanding Korowai people’s active role in changing their political order in the 2010s requires keeping the opacity doctrine situated in its practical context: a general intersubjective politics of everyday exchange, kinship, and religion.

Structural Change Across Papua

What is most known about Papua internationally is army and police violence against Papuans, racial stigmatisation of Papuans in Indonesian national society, and Indonesian immigrant settlers’ demographic and economic dominance of indigenous Papuans in the region’s towns. However, these structural conditions have been complicated across the last fifteen years by a further set of profound transformations: the reorganisation of all aspects of civil government administration under the combination of a nationwide policy of ‘decentralization’ and a specifically Papua-focused policy of ‘special autonomy’.

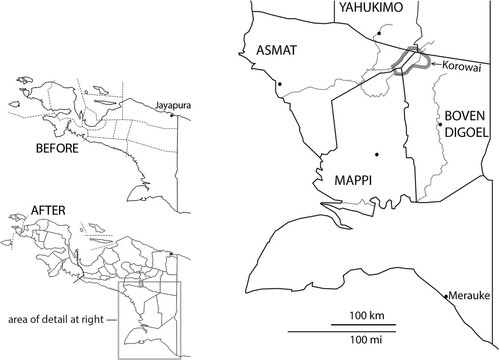

In the wake of the 1998 collapse of the authoritarian Suharto regime, Indonesia undertook a wide-ranging devolution of government power and finances from Jakarta to more local levels, widely described by observers as a ‘big bang’ decentralisation process. The most salient form of this devolution has been splitting off of new administrative units at all territorial levels (Provinces, Regencies, Districts, and Villages).Footnote3 The overall decentralisation policy was rationalised as speeding development by bringing state offices and programmes closer to the people they served, but it also had a function of supporting national integrity by placating grievances and aspirations of people on the country’s dominated peripheries, and its practical implementation has regularly been energised by local elites’ desires for expanded patronage opportunities (Ostwald et al. Citation2016: 5). Nationally, by far the greatest proliferation of new administrative units has taken place in Papua. In 2000, Papua consisted of one Province and twelve Regencies. By 2010, it consisted of two Provinces and forty-two Regencies. When I began fieldwork in 1995, the vast southern lowland plain of Papua was one Regency, headquartered at Merauke, two hundred miles distant from Korowai. After redistricting, the Korowai area is divided between four Regencies, and different Korowai settlements orient to four different Regency seats, each associated with an individual ‘Regent’ (bupati) who is the head of government there. Those administrative centres remain geographically distant, but are much closer than Merauke ().Footnote4 Another new development is that Regents and village heads are elected rather than appointed. It is Papuan men who occupy the Regent posts, putting them socially closer to rural constituents as well. Since late 2019, there has been a further wave of public debate about what goals and political classes are served by this proliferation of new administrative units, after President Jokowi signalled support for certain Papuan elites’ campaigns to hive off two further new provinces (see for example Editorial Board Citation2019).

Figure 1. Left, Regencies in Papua before and after redistricting processes of the early 2000s. Right, Korowai lands divided across four Regencies, with Regency seats as dots.

Another major form taken by decentralisation is Jokowi’s emphasis, since his first election in 2014, on large infrastructure projects at the national margins, and on direct disbursement of annual Village grants for locally chosen development initiatives (Vel et al. Citation2017).Footnote5 This latter programme is called ‘community-driven development’ in World Bank parlance and is administered by Indonesian state agencies as ‘community empowerment’ (pemberdayaan masyarakat).

Compounding the policy of decentralisation, another new twenty-first-century policy of the Indonesian state that was specific to Papua was ‘special autonomy’, instituted to dampen Papuan separatism. This policy would transfer some decision powers from Jakarta to regional institutions, and reallocate most mining royalty revenues to the Papuan regional government rather than the national centre. Many decision-making aspects of the special autonomy law were blocked from implementation by Jakartan power-holders (partly through President Megawati’s precipitous creation of a new province in 2003, the complex machinations behind which are described by Timmer Citation2007). The legislation’s main effects have been dramatic increase of regional government budgets, and dramatically increased Papuan access to public sector jobs. Funding levels on the state periphery have been further bolstered since the mid-2010s by a policy of Papua province’s governor of allocating most special autonomy funding (and associated responsibility for services) directly to Regencies, while cutting Province-level office budgets and staffing.

Papuans widely say that special autonomy has failed in its supposed goal of improving Papuan lives through provision of health care, education, or entrepreneurial chances. This judgment was voiced with greater intensity in the years preceding the first special autonomy law’s expiration in 2021, and in Papuan responses to the form and manner of the law’s renewal (see for example Editorial Board Citation2021). Yet decentralisation and special autonomy have profoundly transformed rural Papua’s political landscape, through vast increase in numbers of salaried jobs associated with new Regencies, Districts, and Villages, and the flow to these units of unprecedented sums of money. The suite of paid jobs linked to a new government administrative unit, and the money controlled by its heads, led local rural Papuans and their emergent elites to focus great attention on establishing new governmental units for themselves (Suryawan Citation2020; Chauvel Citation2021; compare Vel Citation2007; Eilenberg Citation2016). Additionally, the new processes of electing candidates to Regent offices in control of large discretionary budgets meant rural Papuans were newly invited into patronage relations: they give votes to a Regent, and he gives them cash, consumables, and infrastructure.Footnote6 Fiscal flows via Regency administrative centres have also sometimes come to include large lump payments to village leaders, equivalent to many thousands of euros per village annually. Leaders partly consume the money in the administrative centres, and partly bring it back to outlying villages for distribution. These disbursements have meant that villages on the Papuan super-periphery have gone from a general condition of cashless deprivation, relative to towns, to sites of episodic ability to make major purchases.

The practical repercussions of these policy processes are poorly known outside of Papua, not only due to government restrictions on foreign research access, but also due to the vast diversity of social contexts across which the repercussions have been felt. However, two new bodies of work on practical effects of these policy structures in Papua are worth summarising as background to the Korowai example I consider below.Footnote7

One is Yulia Sari’s recent study of community-driven development across Papua (Sari Citation2018). She carried out ethnographic research with actors at all levels of the policy’s implementation, from Jakarta elites to local Papuans in four highland and north coastal villages. What she found was that the felt goals of the policy shifted dramatically across these different positions (Sari Citation2018: 166–169 and passim). World Bank staff define community-driven development as making government downwardly accountable to the people, and as productively grounding government-organised development in local social relations. National ministerial officials define the policy around upward accountability of communities and field administrators for timely submission of reports that will yield quantifiable development achievements. Provincial figures like the governor define the policy around reorganising its administrative procedures to emphasise their level’s importance. The contract workers serving as semi-autonomous ‘facilitators’ (pendamping) between regional government centres and target communities define the policies around timely completion of projects and financial reports, achieved by choosing easily completed small infrastructure projects over more complex undertakings of actual use to host communities. Village leaders and community groups understand the programme as unilateral state distribution of resources, including in the form of ‘monuments’ like toilets, buildings, tanks, or bridges that are valued much less for their concrete usefulness than for the wages or other goods received as part of the construction process.

Sari’s account thus highlights how far apart central state actors and ruled populations can be in their consciousness about a governance programme’s definition, while harmonising in its implementation. By comparison, the account of ‘decentralization’ presented by Jacob Nerenberg (Citation2018; Citation2019), based on intensive fieldwork in and around the highland city of Wamena, focuses on the policy’s observable effect rather than its stated rationales. The model he arrives at is relatively unitary, and elaborates on what Sari observed about the ‘community’ level in community-driven development. Nerenberg describes decentralisation and related policy processes as intensifying Papuan people’s integration into extra-local market and state organisational forms, by involving them in new state-organised networks of commodity distribution. This also involves separating Papuans from direct production of their own livelihoods (see also Nerenberg Citationforthcoming, on Papuan critical unease about the devaluing of agricultural labour entailed in these shifts).

Paralleling what Nerenberg documents in depth for the Wamena region, we will see that commodity distribution is also the core focus of Korowai people’s attention, in their thinking about relations of government.

State Formation at an Extreme Periphery: Korowai Desire to ‘Become Like’ Others

Korowai number roughly four thousand persons, and they historically lived dispersed across five hundred square miles of forest, in single or paired houses standing in garden clearings separated by large expanses of forest. Their landscape was a patchwork of roughly two hundred distinct clan-owned territories. People’s standard explanation for their residential dispersion was that it helped everyone avoid situations of being told what to do by others, or being impinged upon by others in their control of food and intimate family life. Living separately was part of a larger pattern of rejecting relations of authority. There were no named stable leadership roles. People were often quick to reject any suggestion that one person could tell others what to do and expect to be automatically obeyed (Stasch Citation2014a: 86–88; Stasch Citation2015b: 530–531; see wider literature on similar societies referenced in contributions to this issue by Buitron, Widlok, and Laws).

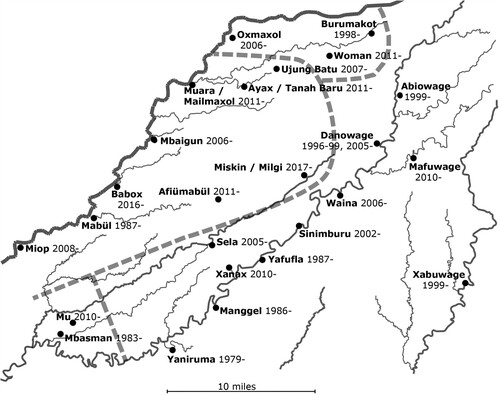

Korowai people’s land is difficult to reach, and it was only in the 1980s that extralocal institutions and actors began to intrude there. The new processes of articulation started in the southwest, centred first on Dutch missionaries and their Papuan church co-workers, and then on international tourists. To Korowai, interactions with these figures were a radical rupture in history, initially provoking millennial fear and xenophobic repulsion. The most prominent practice through which Korowai engaged with the new orders was the making of ‘villages’, an entirely new spatial form (compare Buitron, this issue). From 1980 through the early 2000s, Korowai in different areas gradually formed these new centralised permanent settlements (). They strongly associated the new type of space with hoped access to imported consumer goods, with a new ethos of living peaceably rather than jumping quickly to anger, and with learning the new lingua franca of Indonesian (Stasch Citation2013). Across these decades, most Korowai oscillated residentially between the new settlements and the contrasting ‘forest’ organisation of space, associated with the older political system prioritising autonomy. Actual agents of the Indonesian state, like police, civil servants, or health and education workers, rarely came to the Korowai area in this period, and when they did they only made short visits to a few southwestern villages. In 1996, I was once staying on the forest land of families who were working for several months to put on a feast, and when police from a faraway District seat were expected to visit the nearby village of Manggel, the feast sponsors sent other relatives to go sit in their village houses. This would make the police think Korowai were all compliantly present in the village and participating in state order, and prevent them from hearing about the feast. The police visit never happened. But the ruse was typical of a Korowai pattern of holding state structures at arm’s length.

Figure 2. Selected Korowai villages, 2017. Dashed lines indicate differences in direction of travel to Regency seat.

More recently, in the changed environment of government cash disbursements, Korowai have increased their dedication to village living, and weakened their ‘forest’ activities. There are now about forty centralised villages, all across the Korowai region. By the time of my last visit in 2017, 90% of Korowai were dominantly living in centralised villages, and visiting forest territories mostly on day-trips.

Also in the last ten years, Korowai swung from shunning authority relations to embracing them. By the late 1980s, southwestern Korowai understood creating a physical village as also entailing a goal of eventual government recognition of the settlement as an administrative entity, via installation of local officers such as a ‘Village Head’ (kepala desa; I underline Indonesian words and italicise Korowai ones, across this article). Korowai also quickly identified authority relations as the signature social form of city-dwelling ‘foreigners’, by describing those foreigners’ social world as centred on ‘heads’ who work in ‘offices’ and tell subordinates what to do. (Korowai prolifically discuss the figure of ‘foreigners’ or ‘city people’ in highly generic ways, often indiscriminately lumping together international tourists and missionaries, Indonesian government officials or traders, Papuan church workers or tour guides, and other long-distance strangers. There are also contexts in which some speakers carefully contrast different categories of these kinds.) But during my visits in 2011 and 2017, I encountered a markedly new pattern of Korowai intensely desiring relations of subordination to Regents or other foreign patrons, and even setting up divisions of ruler and ruled among themselves.

Before describing these now-prominent relations, I will foreground a main way Korowai explain being attracted to them: wanting to ‘become like’ other people. For example, it is common to explain individual or collective desires to form a village, or to participate in community-driven development projects for wages, in terms of wanting to ‘be like our people’. Here ‘our people’ refers to other Korowai or to members of neighbouring ethnic groups, who are already doing those activities. Also common are ‘out-group’-focused exhortations such as ‘Let’s live like city people!’, ‘Let’s become village people!’, or ‘Let’s live like foreigners!’Footnote8 Individual Korowai quote these statements as expressing the motivations of Korowai at large for wanting to form villages, create patronage relations with a Regent, or otherwise gain access to consumer goods. Phrases like ‘city people’ in these expressions again stand in highly generic ways for an imagined overall organisation of life around effortless consumption, contrasting with hardships of gardening and hunting.

These explanations echo a characteristic scenario of everyday Korowai affairs: expressing desire to be ‘like’ other relatives, in material activities and possessions. This is a concrete emotional, moral form taken by egalitarianism, as a past Korowai political order. People want what others have, and want to do what others are doing.

What is new is dense Korowai involvement with global market networks, in which Korowai see themselves as occupying an inferior position. Embrace of authority structures has arisen through applying old egalitarian values to this new macrostructure of deprivation. Paradoxically, egalitarian, anti-authority political sensibilities have played into the shift toward authority structures. Korowai are attracted to relations of hierarchical subordination of certain kinds, as a path to fixing even more troubling subordination in the new system of consumer wealth (Stasch Citation2021).

This explanation was explicitly given to me in 2017 by many Korowai whom I asked about their comfort with a new division in their own social field between ‘heads’ and ‘people’. Instituting this division has been closely linked to participation in community-driven development, and other intensified village-making practices.

Until the 1990s, the Korowai word xabian ‘head’ was used only to talk about anatomical heads or head-like parts of objects, not political roles. But influenced by the Indonesian word kepala (as in kepala desa ‘village head’ or kepala kantor ‘office head’), Korowai started using their own word xabian also to mean ‘leader’, defined as a person who tells others what to do and is obeyed. Initially, it was urban strangers like tour guides or government officials who were mainly identified as ‘heads’. But more recently, ‘heads’ has started being heavily used as a designation for Korowai men holding any of an expanding range of titled roles in the state template of village government, such as ‘Village Head’, ‘Secretary’, ‘Head of Civil Defense’. ‘Neighborhood Head’, or ‘Village Council Member’. What startled me during 2017 fieldwork was that in Korowai discourse these ‘heads’ now prominently stand in a polar contrast with ‘people’ or ‘community’ (referred to by the borrowed Indonesian word masyarakat). In Korowai eyes, part of what defines the ‘heads’ as a role position is that those men receive a stipend (honor). This can be a focus of resentment by others, and is also why ‘head’ roles often are held by owners of land near the village, to the exclusion of people whose clan land is farther away (see Stasch Citation2009 on tensions between landownership and egalitarianism generally). The rise of a polarity of ‘heads’ versus ‘people’ has involved a transition to officeholders actually telling other Korowai what to do, and being heeded. Korowai say they embrace the new division because it is by accepting subordination to ‘heads’ that the ‘people’ will get money, consumer goods, metal-roofed buildings, and the like.

The ‘head’ position tends to be masculine. An in-built patriarchal assumption of the Indonesian administrative system is that salary-bearing village offices are almost entirely gendered male. This harmonises with Korowai women’s socialisation into intense feelings of ‘shame’ or ‘embarrassment’ (xatax) at the prospect of speaking freely amidst mixed-sex, extra-familial audiences. A woman whose father, son, brother, or husband occupies a village office may at times strongly identify herself with the ‘head’ positionality via that man’s role, or at other times distance herself as merely of the ‘people’. Often, women and men alike speak as if sheer kinship distance – independently of gender – is the crux of their access or exclusion in relation to ‘head’ positions and associated resources.

One pattern instituted in the Korowai area since roughly 2015 is for a Korowai village head and his other supporting officeholders to receive instructions about what physical infrastructure project to carry out, from a visiting ‘facilitator’ (pendamping) or from District or Regency officials. Typical community-based development projects include clearing new village lanes, digging gutters, building wooden docks, bridges, or walkways, or carrying lumber and other materials for visiting carpenters contracted to build houses, offices, schools, or clinics. ‘Heads’ organise and record the labour of their ‘people’, and provide verbal or photographic testimony of completed work to purse-string holders at faraway administrative centres, often via ‘facilitators’ or other intermediaries, who incorporate heads’ documentation into more polished reports. Part of the circulatory system is the posting of signboards at completed project sites (). These signs are sent out from Regency centres, and list information about the location and budget of the project. Ideally the signs and completed projects are then re-photographed for the benefit of officials back at Regency seats, where they might enter election campaign publicity. (These signs bear comparison to Widlok’s discussion in this issue of contrasts between embodied pointing and state modes of territorialisation. While the dominant address of the signs is toward faraway, ‘higher’ nodes of administrative hierarchy, and many Korowai living amidst the signs cannot read them, the signs are potent sentinels of the state’s wealth-mobilising power even for non-literate villagers.) When lump monies are disbursed, the heads divide it out to their ‘people’, including women and children, who are typically among the enthusiastic labourers. A partial dietary transition away from garden produce and toward rice, noodles, and coffee has been an important enabling condition of the extensive local politicking required to coordinate this labour, and of people’s availability for the work itself. Like people in some other peripheral parts of Papua, Korowai now look strongly toward a national aid programme of distributing so-called ‘Welfare Rice’ ().Footnote9 In conversations among Korowai for whom village life is new, the dominant way they talk about community-driven development is the category ‘paid work’, expressed by the new Korowai word kelaja, borrowed from Indonesian kerja ‘work’. Korowai involved in the small labour projects describe themselves as ‘taking hold’ of paid work, or being ‘given’ paid work (kelaja ati- and kelaja fedo-, respectively).

Figure 3. District Head of Mabül with sign listing budget and labour arrangements for the new lane of an outlying village, August 2017. This Papuan man from fifty miles southeast has been posted to a new District comprising the northwest third of the Korowai area. He was touring upstream villages to inspect labour projects, for reporting to Asmat Regency.

Figure 4. Village Head of Sinimburu (left), throwing ashore ‘Welfare Rice’, September 2017. The motorboat was also village aid.

Korowai embrace of this labour pattern and its entailed structures of state hierarchy has been fuelled by the above-noted desire to ‘become like others’, but also by a related past Korowai transactional sensibility of presenting oneself enthusiastically to others in a form they desire, as a means to achieve new good relations and material outcomes. The value of being ‘like’ others and the value of performing to others’ desires both fit within a larger overall pattern of Korowai feeling themselves to be intensely answerable to others and their relations with them. This also means that the political emphasis on ‘autonomy’ that I have described earlier is something different from the political order of European liberal individualism. Rather, sensitivity about autonomy is complexly intertwined with a foundational commitment to being interrelated (a complexity I sought to understand in Stasch Citation2009). In any case, the past sensibility that meeting others on their own transactional terms is intrinsically good now informs how energetically Korowai seek to make themselves legible to government officials (Stasch Citation2015a; see also Stasch Citation2014b).

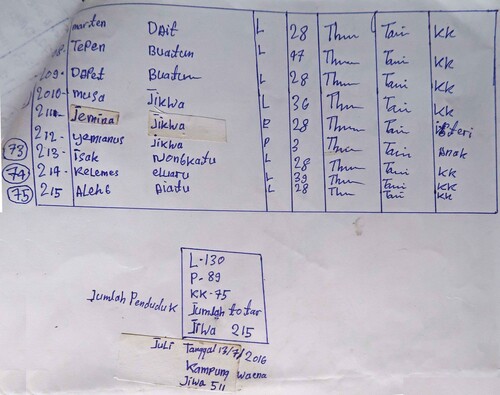

State formation on the village level is Korowai-led in many different practical contexts, not just the community-driven development programmes. Government staff still only rarely visit a few villages in the Korowai area, and have only hazy ideas of concrete conditions there. (The District Head shown in is exceptional in often living locally, and in sometimes visiting outlying villages or even forest territories.) It tends to be Korowai themselves who take initiative in making themselves legible to state officials, by deciding to form a village in the first place, physically opening clearings, compiling lists of village residents to take to administrative centres, and lobbying intermediary officials for help with seed resources to support the village-making process ().

Figure 5. Last page of a list of residents of Waena village, written in July 2017 to seek recognition by Regency administrators.

There is an upward quality to Korowai performances to government officials’ desires, that was not as prominent in past kinship and exchange contexts. I turn now to this quality, particularly in the context of Korowai concern with ‘Regents’, who are today imaginatively prominent. The historical change to seeking hierarchical subordination to such figures has again been paradoxically fuelled by sensibilities that underpinned past shunning of authority relations.

Poverty Village: Anticipating Thoughts of the Powerful

While Korowai were not previously familiar with patron-client or ‘big man’ leadership structures, such personalistic models of authority have turned out to be relatively easy for them to adopt in the new state environment (compare Dalsgaard Citation2019: 261, 263). One context in which emerging Korowai ideas about patronage are visible is again founding villages, or efforts to get them better recognised.

A striking case of village-making occurred in 2017. Almost all Korowai villages have been given the name of a nearby stream, the only kind of land feature bearing proper names in the Korowai language. However, in mid-2017, founders of a new village in the eastern Korowai area decided to name their settlement by the Indonesian word miskin, meaning ‘Poor’ or ‘Poverty’.Footnote10 They had a specific audience in mind for this name. As one man explained to me in Korowai (with interspersed Indonesian words indicated here by underlining):

The reason for calling it Poverty is because so many years went by and Boven Digoel Regency did not look at us. We thought, ‘So our little village, let’s call it Poverty.’ Government, they will think, ‘Why is that? Why are you doing that?’ And we will explain, ‘Why didn’t you look at us? Our village, we wanted it to grow. You were going to give us a village. We were waiting. And you didn’t look at us.’ That’s why.

There had been no prior village close to the Poverty site, but some residents did previously have houses in Waena, established ten years earlier at a site three miles south. For this breakaway faction, the new location had the advantage of being next to their own clan land, which meant it would be easier to get food while living in their village houses, and easier to persuade clanmates to join them in village living. But founding Poverty was also an act of switching affiliations away from the Regency seat of Boven Digoel forty miles southeast, to which Waena village was affiliated, in favour of the different Regency seat of Agats, 130 miles west. As part of this manoeuvre, the name Poverty was meant to dramatise past failings of one Regent, to spur another competitively. As the same Korowai man elaborated: ‘The Agats Regent will think, “Poverty, why are they calling it that?” [We will explain,] “It’s because the Boven Digoel Regent didn’t give a village.” And he will think, “Okay, no problem, I will give to them.”’

Association of village space with a hoped new social order of easy consumption means that any practical act of creating or joining a village expresses desired affiliation to foreigners’ system of wealth. All villages signify, in effect, ‘We are impoverished, and we hope you city people will give us aid.’ Most residents of Poverty were monolingual in Korowai. But almost all Korowai know the Indonesian word miskin ‘poor’, since it is iconic of who they understand themselves to be, within the new wealth hierarchy. The name matched and clarified the core idea of a village as a physical entity: presenting oneself as poor to outsiders, in the outsiders’ own terms of inequality and possible uplift.

This name ‘Poverty’ was criticised by other Papuan intermediaries, including the District Head of Mabül fifteen miles to the west, who was mediating the villagers’ case upward to Asmat Regency. The intermediaries rejected the name because of its uncomfortable self-abasement. Possibly it was too honest, as a description of patron-client inequalities. The nascent village is now officially known as Milgi, a stream-derived name, and the faraway Regent likely never heard the name ‘Poverty’. Yet by the time intermediaries objected, this name was in wide use among Korowai, and will probably keep being used.

Widespread Korowai preoccupation with Regents follows the already-outlined trend of Korowai actively presenting themselves as a legible population in forms they understand to be desired by state officials, within an overall bargain of Korowai accepting hierarchical subordination to superiors in order to ameliorate the painful inferiority they feel at being excluded from urban wealth. This Korowai pattern broadly matches Ferguson’s (Citation2013) account of the value of ‘declarations of dependence’ in southern Africa, but with nuances distinctive to Melanesian responses to colonial and postcolonial experiences of relative deprivation. One exploration of these region-specific nuances was the discussion of ‘humiliation’ convened by Robbins and Wardlow (Citation2005). A feature of the regional patterns that is underscored by the story of Poverty village is that experiences of humiliation may take particularly sharp form as expressive performances toward another person, who stands in a superior position of potential benefactor.

The Poverty story also illustrates that Korowai directly model the thoughts of this potential benefactor. The founders of Poverty were bold not just about predicting other people’s thought but even trying to influence it. The name was intended, we have seen, to provoke a puzzled train of reasoning: ‘They will think, “Why is that? Why are you doing that?” … . The Agats Regent will think, “Poverty, why are they calling it that?”’ This would be an opening for a didactic Korowai reply, describing the failings of the rival Regent. As an effect of this reply, ‘He will think, “Okay, no problem. I will give to them.”’

Such modelling of a Regent’s thoughts seems in line with wider comparative tendencies for subordinates to labour more to know the subjectivity of superiors than the reverse (discussed by Steinmüller in this issue; see also for example Ochs Citation1988: 142). But how does the boldness square with the pattern of Korowai disavowing knowledge of others’ subjectivity, and with my and others’ discussions of ‘opacity of other minds’ as a widely elaborated Melanesian cultural model (Stasch Citation2008)? As far as I know, Korowai are not newly expanding their reasoning about others’ thoughts. Doing something deliberately startling, to provoke a certain chain of reasoning in another, was a frequent past Korowai practice. So in this respect, the namers of Miskin village followed an established model of action. Also common were gestures of self-lowering, particularly around material deprivation. For example, there are many Korowai whose parents or other senior relatives gave them names like ‘Famine’ (luntep) ‘Lacking People’ (mayox-alin), ‘Houseless’ (op-alin), ‘Hungry’ (xo-lep), ‘Lacking Sago’ (xo-alin), or ‘Bad’ (lembuf). The names registered abasement in the old system of most valued possessions: sago and relatives. Adults conferred such names because they found intense aesthetic and emotional poignancy in the child’s described condition of lack. So too it is a common everyday interactional pattern for people to emphasise their own lack of articles, relatives, skills, beauty, or other good attributes. Korowai egalitarianism often takes the form of desire to avoid being seen as a focus of special attention or as claiming to be better than others, and high sensitivity to the possibility that others are mocking oneself. But self-lowering was also an invitation to others to feel ‘love, longing’ (Kor. finop, Ind. sayang), and to give food or durable objects, in a gesture of equalising care. A common Korowai account of why international tourists want to visit them is that the tourists have heard that Korowai lack imported consumer goods, and out of ‘love, longing’ they come to divide articles to Korowai to ameliorate this lack. All these patterns involve attributing specific psychological processes to other people, something basic to Maussian exchange processes generally.Footnote11

In an example like anticipating a Regent’s response to the name ‘Poverty’, the boldness of speculation about another’s thoughts might be reconcilable with a value of egalitarian autonomy partly thanks to its self-deprecatory element. With that name, the villagers were positioning themselves as subordinates to a benefactor. Claiming knowledge of someone’s thoughts violates autonomy less, when done within an overall gesture of self-lowering relative to that other. As a non-threatening way to try controlling someone else, the self-lowering is also here modelled as inviting the other into an interpretive process. Villagers were not speaking for the other man, or telling him what to decide, but putting before him a puzzling sign. They wanted to lead him in a certain direction, but he is meant to get there by his own reasoning. Sensitivity about impinging on another’s autonomy of mind coexists, across these patterns, with a sense that some degree of aggressive impingement can be relationally generative (Stasch Citation2009).

My answer to the puzzle of anarchists for the state likewise combines two opposed ideas. Korowai have drastically changed their political sensibilities. The new environment of exogenous state structures and market connections have caused rapid Korowai transition from repelling to embracing authority relations. Yet at the same time, kernels of this new comprehension, toleration, and embrace of authority relations were present in their old egalitarian, anarchist system. A prominent aspect of past and ongoing Korowai political thought is the image of one person ‘hearing’ (dai-) or ‘fulfilling’ (kümo-) the talk of another. This is how Korowai describe new stable authority relations, but it is also how they described past patterns of highly valued (if difficult to achieve) social coordination, in which one person was seen to do another’s bidding, in a mode of voluntaristic goodwill. Their past aversion to subordination, and techniques of trying to level inequalities, involved also strong sensitivity to subordination as a relational possibility (see also Stasch Citation2014a: 87).

State-Like Domination in Traditional Religion: From Avoidance to Transaction

The complexity of the historical change can be further grasped by considering dynamics of subordination in Korowai thought about divinities. In this final ethnographic section, I outline religious patterns parallel to the shift toward being attracted to Regents. These patterns further illustrate how kernels of new practice were present in older sensibilities, even while the new is a revolution.

I take an initial cue from Sahlins’ (Citation2017a) argument about the universality of human domination by ‘metahuman’ powers (critically assessed in other essays in this issue, guided by Buitron and Steinmüller’s use of Sahlins’ thesis to bridge issues of mental opacity and state legibility). Korowai are a good match to Sahlins’ point that intra-human egalitarians often see themselves as subject to harsh domination by nonhuman powers. The most powerful divinity in past Korowai religious thought, sometimes termed ‘World Creator’ (lamol fuboləxaabül), was a bad-tempered tyrant who episodically destroyed his creation. More prosaically, people often explained their past ‘forest’ practices of land use, kinship norms, and so on by saying they were ‘fulfilling the talk’ of the World Creator or ‘fulfilling the talk of our parents’, this last in reference to memories of when parents were alive and carrying out the same practices. Here, living culturally and historically is conceived a system of ‘discourse’ or ‘talk’ (aup), which is tantamount to self-subordination to others’ exhortations.

A closer focus of religious concern than the ‘World Creator’ was a population of ‘taboo site people’. These are angry, embarrassed refugees of earlier cycles of creation, who now hide at ‘taboo sites’ (wotop) on each Korowai clan territory. Outbreaks of illness or death were attributed to them. To prevent such misfortunes, landowners periodically left them propitiatory offerings of pig fat, which were received by the divinities as a whole carcass. The main feature of relations between humans and these divinities, though, is that the two should avoid each other. Korowai kept away from the sites where the divinities live. When leaving offerings near the sites, landowners’ verbal request to the divinities was that they should ‘turn their backs’. The divinities themselves desire not to be seen or interfered with, and grow angry if Korowai encounter them. If subjection to these divinities resembled state rule, actual Korowai religious practice followed an anti-state, anarchist mode of relating to power-holders by staying separate from them (see the brief exchange between Howell Citation2017 and Sahlins Citation2017b: 162–163). This even included epistemological avoidance and opacity: people’s knowledge of these divinities is fragmentary, and transgressive to discuss, another mode of coping with power by keeping it at arm’s length.

The image of ‘turning backs’ is an unusually standardised element, in people’s otherwise unstable ideas about ‘taboo place people’. The other prototypic context of exhorting someone to ‘turn their backs’ is the relation between mother-in-law and son-in-law. Such persons carefully observe a suite of everyday bodily and linguistic avoidances, which register the man’s intrusion into the woman’s relation with her daughter, and his ongoing state of obligation toward her. To help these pairs avoid seeing each other, houses were divided by a middle wall. But it is also a common interactional event for a seated person to physically ‘turn their back’ when warned to do so by others because his mother-in-law (or her son-in-law) is about to come into sight. I have argued elsewhere that mother-in-law and son-in-law pairs, through these avoidances, paradoxically make sensory separation a means of intensified social involvement (Stasch Citation2003; Citation2011). Matching Widlok and Laws’ ideas about the centrality of avoidance practices to egalitarian politics (in this issue), I portrayed the mother-in-law relationship as paradigmatic of a wider Korowai pattern of making otherness a positive focus of social bonds (Stasch Citation2009). The repetition of the ‘turning backs’ image and overall avoidance structure in relations with divinities is a case of strong continuity between people’s models of their intra-human social relations and their models of their relations with metahuman powers.

What Sahlins’ discussion helpfully foregrounds is a point I already introduced: being egalitarian does not mean lacking concepts or experience of authoritarian domination. Rather, it means being distinctively sensitive to such domination, as a pervasive feature of life. Yet there is a difference between knowing about higher powers to which one’s life is subject and trying to avoid them, versus seeking interactional proximity to those powers.

In 2017, I encountered a sharp illustration of the larger Korowai shift from avoidance to attraction, in relation to superior powers. The example again involved the recently established District seat of Mabül, a centre of state-formation processes along the northwestern side of the Korowai area. One symptom of Korowai enthusiasm for accessing a new economic system through patronage ties is the constant circulation of rumours that a Regent will be visiting (Stasch Citation2015a; Citation2021). Exceptionally, Mabül has actually been visited by a Regent several times. He comes by speedboat or helicopter, from Agats. When a visit by him is expected, hundreds of Korowai gather from outlying villages or forest territories.

During my 2017 fieldwork, I stayed for about two weeks in a forest clearing five miles southeast of Mabül, with a senior married couple named Bolumale and Mailalun. These two were unusual for still living mainly on their forest territory, and only visiting villages transiently. The woman Mailalun is also a spirit medium. In the mid-2010s, she shocked her husband by informing him during a mediumship session that the Agats Regent is a ‘taboo site person’ from Bolumale’s own clan land. The fact that the Regent appears to occupy another identity and to arrive in the Korowai area from elsewhere is here understood as a pretense he maintains, to uphold the principle of avoidance and separation between visible humans and the divinities. Bolumale’s own hopeful interpretation is that beneath this affectation, the Regent’s actual connection to Bolumale and his land means he is intent on bringing articles and prosperity to him. When the Regent visits, Bolumale is among the people who gather at Mabül. Bolumale forwards himself prominently in traditional dress, and the press entourage stages photos of the Regent with him, as an iconic Korowai man (). Bolumale also makes a point of averting his gaze from the Regent, following the old avoidance principles.

Figure 6. Regent of Agats (centre left) facing his videographer for an interview with the village head (centre), on departure from Mabül village, December 2017. Bolumale looks on in traditional dress, without understanding the Indonesian talk.

This example is idiosyncratic to a small kin network, but harmonises with wider innovations. For example, in the 1980s when villages were entirely knew, ‘taboo site people’ were always said to be offended by the physical existence of these centralised settlements, but today Korowai commonly say that the ‘taboo site people’ themselves live in villages.Footnote12 Bolumale’s ideas entail a basic change of evaluation toward the divinities. The idea that ‘taboo site people’ are angry agents of harm slightly declines, while emphasis on possible positive transactions with them slightly increases. Among other Korowai kin networks, I have regularly encountered under-the-breath speculation that international tourists or TV filmmakers who visit their land are the ‘taboo site people’ from there. The fact that the strangers are from that specific clan territory is again what explains the strangers’ action of bringing exchange valuables to that specific kin network.

In the overall sweep of Korowai engagement with foreign institutions, talk about occult divinities arises only occasionally. But this imagery is consistent with wider patterns of thought about subordination, opacity, and legibility that we have already glimpsed. Associating a Regent with a type of divinity standing in an avoidance relation to humans construes agents of power and wealth as intrinsically opaque.Footnote13 This opacity is a surrounding context of anyone’s gestures of presenting themselves to each another in the visible terms of a patronage relation. Along the lines of points also developed by Bovensiepen (this issue), opacity and making legible are dialectically intertwined.

Related to this dialectical intertwining, Bolumale’s story again involves both a rupture in conceptions of divine power, and elaboration of ideas already present in the older system. In that system, divinities’ powers meant they were diffusely a condition and source of Korowai well-being, even if this was mainly reflected in Korowai trying to placate their potential anger, to avoid loss of life. Avoiding direct encounter with the powerful beings, Korowai elaborately related to them. I suggest again that two interpretations of these historical processes are both true. Prior religious experience has supplied a model of subjection that Korowai are newly following in relations with the state (a possibility suggested by Sahlins’ thesis of the state-like character of religious compacts). But additionally, religious representations are shifting, under the influence of a changed order of state and market forces.

Conclusion

The ethnographic impetus of this article has been Korowai people’s initiatives of making themselves legible to state administrators, in the strangers’ own terms. From this, I have drawn theoretical lessons about egalitarian polities, and about historical change and articulation. When large-scale exogenous structures of wealth and power became a new horizon of life, old Korowai egalitarian principles worked as pathways into subordination, and as tools for dealing with unprecedented feelings of deprivation (compare Buitron Citation2020). This analysis has involved recognising complications and ambivalences within past Korowai forms of anti-state, anti-authority political order. Patterns of wishing to ‘be like’ other people, self-lowering as a transactional strategy, and avoidance or identity-masking in diplomacy with divinities illustrate that Korowai people’s past was full of acute sensitivity toward inequality, and involvement with it. Being averse to authority relations meant also knowing them well. This complexity has shaped their polity’s susceptibility to rapid transformation, in interaction with state and market structures.

About the articulations between Korowai political sensibilities and new exogenous institutions, another important pattern is the compatibility between Korowai sensibilities and the ‘politics of distribution’ (Nerenberg Citation2018) that has become a new main mode of state power in Indonesian Papua. There is a ‘good enough’ fit, or ‘working misunderstanding’, between what Korowai see themselves to be doing when making overtures to state agents, and those agents’ models of the relation (also like the chain of disparate perspectives documented by Sari Citation2018). When rulers or the ruled emphasise legibility or put themselves legibly forward, there is still much in the government relation that differs from those portrayals. Ideas of intentional dissimulation (tipu ‘deceive’) are a popular motif in discussions of governance and state-society relations in Papua. Even if people were not mainly striving at intentional deception, much success of government order-making flows from the selectivity of intentions anyone attributes to others in efforts to coordinate socially with them, when the overall field of ideas in play is much more heterogeneous.

Finally, concerning how large-scale political change intersects with ‘opacity’ in the narrow sense of certain egalitarian people’s patterns of disavowing knowledge of others’ thoughts, my suggestion has been that in the Korowai case there has not been a sudden switch of orientations. Rather, emphasis on others’ autonomy of mind was an element within practices of relation-making through exchange, within practices of kinship, and even within political and transactional relations with divinities. Keeping the opacity pattern connected to the wider contexts where people practically experience it, like the intersubjective dynamics of exchange, is crucial in turn to understanding what is happening in historical shifts like the new Korowai performances of self-subordination and thought-attribution toward government rulers.

Acknowledgements

This article is based on two years of fieldwork in the Korowai area since 1995, and a year of cumulative experience in the Jayapura area and other places in Papua. Above all I am thankful to different Korowai who shared their views with me in ten villages and five forest homes I visited during four and half months of research in 2017. I also benefited from logistical support from the Johnson family in Danowage, the de Vries family in Sinimburu, and Wayap Dambol everywhere. I am very grateful for helpful ideas and suggestions offered by Natalia Buitron, Hans Steinmüller, Sophie Chao, Yulia Sari, Jacob Nerenberg, other contributors to this issue or participants in the LSE workshop, and everyone who has engaged with the argument of my 2008 article on Korowai talk about others’ thoughts.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Another site of state-society realignment across peripheral Indonesia has been fitful institutionalisation of ‘indigenous’ (adat) bodies, as government entities or interlocutors, somewhat modifying the older constitution of adat as ‘customary law’ under Dutch colonial rule, or as ‘tradition’ under the Suharto dictatorship. Initiatives in this vein have been important in the wider southern lowlands region (as they are across Papua more widely), and are being occasionally imported or explored in the Korowai area. However, the state formation processes I discuss in this article were much more prominent, at least in the 2010s.

2 Danziger and Rumsey (Citation2013: 247) helpfully underline that opacity doctrines exist within ‘an architecture of nested levels’. For example, disavowing knowledge of another’s intentions still means holding a model of the other as having intentions. See also Laws (this issue) for a valuable account of variation in whether and how people model others’ intentions, or experience themselves as autonomously unconstrained in relating, across different relations within a single ‘egalitarian’ social world. De Vries (Citation2013) valuably discusses a range of Korowai linguistic patterns relating to thought and feeling.

3 In Indonesian, the hierarchy of civil government administrative levels is provinsi, kabupaten, distrik (syn. kecamatan, no longer used in Papua), and desa. To underline that these categories are administrative units, I capitalise Province, Regency, and District throughout this essay, as well as ‘Village’ when referring to the idea of a bureaucratically recognised desa unit (as against villages as physical settlements, many of which do not have desa status). The Indonesian word kampung is widely used by Korowai as a term for villages as physical settlements, but is not prominent in talk about settlements as state entities (whereas kampung has become the more prominent term in some administrative settings elsewhere in Papua).

4 The boundaries and names of the four Regencies that were created from the earlier single Merauke Regency are a close match to Dutch administrative division of the lowlands into several onderafdeeling (‘subdistricts’) in the mid-twentieth century, during an initial phase of state formation prior to Indonesia’s 1963 takeover.

5 The infrastructure project most dramatically felt in the Korowai area was construction of a massive asphalted airfield at the eastern Korowai village of Danowage in the late 2010s. An especially high-profile focus of Jokowi’s Papua policy has been renewed investment in road construction, and many Korowai are enthusiastic about anticipated road connections.

6 For an example of a larger-scale version of the concrete encounters this has involved, see the widely disseminated April 2021 Tiktok video of the Bupati of Yahukimo distributing a car-sized mountain of cash to District or Village leaders under his jurisdiction, before an assembled crowd of a few thousand (e.g. https://youtu.be/Umc_OLPLjGo, accessed 20 April 2021).

7 See also the earlier contributions of Timmer (Citation2007) and McWilliam (Citation2011).

8 The Korowai-language statements I am generalising about take many forms. The meaning ‘like’ is typically expressed by the clitics -xaxo or -ülop, suffixed to admired others like ‘our relatives’ (noxu-mayox or noxu-yanop, lit. ‘our people’), ‘city people’ (kota-anop), ‘village people’ (xampung-anop), ‘white people’ (xal-xeyo-anop), or ‘foreigners’ (laleo-alin, lit. ‘zombies’). ‘Let’s become … !’ is often expressed by the inflected clause-final verb -telafon.

9 In Indonesian, the rice is called raskin, a portmanteau of beras miskin, where beras is ‘rice’ and miskin is ‘poor’. The first government benefit received by residents of Poverty village was an allocation of fifty sacks, which they carried to their settlement by a two-day walk.

10 In standard Indonesian, ‘poverty’ is kemiskinan, but most Korowai do not use the morphology that is added to miskin ‘poor’ to form this word. Translating miskin as both ‘poor’ and ‘poverty’ gives a good approximation of what Korowai hear in the word.

11 See for example Munn (Citation1986), on intertwining of exchange with opacity and intersubjective influence. See also Laws (this issue) on San people’s understanding that care between kin is a matter of ‘thinking about’ each other. This is also a prominent Korowai model.

12 In the early decades of village formation, clans whose land was near a new village mostly abandoned making pig fat offerings at ‘taboo sites’ on their land, because the now-enraged ‘taboo site people’ were held to understand villages’ presence as a basic cosmological violation of existing order that made the sacrificial transactions unwelcome. More recently, increasing church participation and Christian conversion has fed into abandonment of the sacrifices.

13 I have explored elsewhere recurrent Korowai linking of urban wealth to bereavement, which also involves a painful conjoining of identificatory desire and opaque separation, in relation to foreign power (Stasch Citation2016).

References

- Buitron, Natalia. 2020. Autonomy, Productiveness, and Community: The Rise of Inequality in an Amazonian Society. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 26:48–66.

- Chauvel, Richard. 2021. Pemekaran: Fragmentation, Marginalization and Co-Option. In Emansipasi Papua: Tulisan Para Sahabat untuk Mengenang dan Menghormati Muridan S. Widjojo (1967–2014), edited by R. Tirtosudarmo and C. Pamungkas, 273–289. Jakarta: IMPARSIAL, the Indonesian Human Rights Monitor.

- Clastres, Pierre. 1977. Society Against the State. New York: Urizen Books.

- Dalsgaard, Steffen. 2019. Local Government and Politics: Forms and Aspects of Authority. In The Melanesian World, edited by Eric Hirsch and Will Rollason, 255–268. London: Routledge.

- Danziger, Eve & Alan Rumsey. 2013. Introduction: From Opacity to Intersubjectivity Across Languages and Cultures. Language & Communication, 33:247–250.

- Dasgupta, Aniruddha & Victoria A Beard. 2007. Community Driven Development, Collective Action and Elite Capture in Indonesia. Development and Change, 38(2):229–249.

- de Vries, Lourens. 2013. Seeing, Hearing and Thinking in Korowai, a Language of West Papua. In Perception and Cognition in Language and Culture, edited by Alexandra Aikhenvald and Anne Storch, 111–136. Leiden: Brill.

- Donzelli, Aurora. 2019. Methods of Desire: Language, Morality, and Affect in Neoliberal Indonesia. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press.

- Editorial Board. 2019, November 12. Divide and Rule Papua. Jakarta Post. https://www.thejakartapost.com/academia/2019/11/12/divide-and-rule-papua.html.

- Editorial Board. 2021, July 21. New Deal, Old Approach. Jakarta Post. https://www.thejakartapost.com/academia/2021/07/20/new-deal-old-approach.html.

- Eilenberg, Michael. 2016. A State of Fragmentation: Enacting Sovereignty and Citizenship at the Edge of the Indonesian State. Development and Change, 47(6):1338–1360.

- Ferguson, James. 2013. Declarations of Dependence: Labour, Personhood, and Welfare in Southern Africa. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 19(2):223–242.

- Graeber, David. 2004. Fragments of an Anarchist Anthropology. Chicago, IL: Prickly Paradigm Press.

- Grossman, Guy & Janet Lewis. 2014. Administrative Unit Proliferation. American Political Science Review, 108(1):196–217.

- Herriman, Nicholas & Monika Winarnita. 2016. Seeking the State: Appropriating Bureaucratic Symbolism and Wealth in the Margins of Southeast Asia. Oceania, 86(2):132–150.

- Howell, Signe. 2017. Rules Without Rulers? HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory, 7(2):143–147.

- Jansen, Stef. 2014. Hope for/Against the State: Gridding in a Besieged Sarajevo Suburb. Ethnos, 79(2):238–260.

- Jorgensen, Dan. 2007. Clan-Finding, Clan-Making and the Politics of Identity in a Papua New Guinea Mining Project. In Customary Land Tenure and Registration in Australia and Papua New Guinea: Anthropological Perspectives, edited by James F. Weiner and Katie Glaskin, 57–72. Canberra: ANU E Press.

- McWilliam, Andrew. 2011. Marginal Governance in the Time of Pemekaran: Case Studies from Sulawesi and West Papua. Asian Journal of Social Science, 39:150–170.

- Munn, Nancy D. 1986. The Fame of Gawa: A Symbolic Study of Value Transformation in a Massim (Papua New Guinea) Society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Nerenberg, Jacob. 2018. Terminal Economy: Politics of Distribution in Highland Papua, Indonesia (PhD dissertation). Department of Anthropology, University of Toronto.

- Nerenberg, Jacob. 2019. Regulating the Terminal Economy: Difference, Disruption, and Governance in a Papuan Commercial Hub. Modern Asian Studies, 53(3):904–942.

- Nerenberg, Jacob. forthcoming. ‘Start from the Garden’: Distribution, Livelihood Diversification and Narratives of Agrarian Decline in Papua, Indonesia. Development and Change, https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12691.

- Ochs, Elinor. 1988. Culture and Language Development: Language Acquisition and Language Socialization in a Samoan Village. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Oppermann, Thiago. 2015. Fake It Until You Make It: Searching for Mimesis in Buka Village Politics. Oceania, 85(2):199–218.

- Ostwald, Kai, Yuhki Tajima & Krislert Samphantharak. 2016. Indonesia's Decentralization Experiment: Motivations, Successes, and Unintended Consequences. Journal of Southeast Asian Economies (JSEAE), 33:139–156.

- Robbins, Joel & Holly Wardlow (eds). 2005. The Making of Global and Local Modernities in Melanesia: Humiliation, Transformation, and the Nature of Cultural Change. Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

- Rumsey, Alan & Joel Robbins. 2008. Introduction: Cultural and Linguistic Anthropology and the Opacity of Other Minds. Anthropological Quarterly, 81(2):407–420.

- Sahlins, Marshall. 2017a. The Original Political Society. HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory, 7(2):91–128.

- Sahlins, Marshall. 2017b. In Anthropology, It’s Emic All the Way Down. HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory, 7(2):157–163.

- Sari, Yulia Indrawati. 2018. The Building of ‘Monuments’: Power, Accountability and Community Driven Development in Papua Province, Indonesia (PhD dissertation). Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University.

- Schwoerer, Tobias. 2018. Mipela Makim Gavman: Unofficial Village Courts and Local Perceptions of Order in the Eastern Highlands of Papua New Guinea. Anthropological Forum, 28(4):342–358.

- Scott, James C. 1998. Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Scott, James C. 2009. The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Stasch, Rupert. 2003. Separateness as a Relation: The Iconicity, Univocality, and Creativity of Korowai Mother-in-Law Avoidance. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 9(2):311–329.

- Stasch, Rupert. 2008. Knowing Minds is a Matter of Authority: Political Dimensions of Opacity Statements in Korowai Moral Psychology. Anthropological Quarterly, 81(2):443–453.

- Stasch, Rupert. 2009. Society of Others: Kinship and Mourning in a West Papuan Place. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Stasch, Rupert. 2011. Word Avoidance as a Relation-Making Act: A Paradigm for Analysis of Name Utterance Taboos. Anthropological Quarterly, 84(1):101–120.

- Stasch, Rupert. 2013. The Poetics of Village Space When Villages are New: Settlement Form as History-Making in West Papua. American Ethnologist, 40(3):555–570.

- Stasch, Rupert. 2014a. Powers of Incomprehension: Linguistic Otherness, Translators, and Political Structure in New Guinea Tourism Encounters. HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory, 4(2):73–94.

- Stasch, Rupert. 2014b. Toward Symmetric Treatment of Imaginaries: Nudity and Payment in Tourism to Papua's ‘Treehouse People’. In Tourism Imaginaries: Anthropological Approaches, edited by Noel B. Salazar and Nelson H. Graburn, 31–56. Oxford: Berghahn.

- Stasch, Rupert. 2015a. From Primitive Other to Papuan Self: Korowai Engagement with Ideologies of Unequal Human Worth in Encounters with Tourists, State Officials, and Education. In From ‘Stone-Age’ to ‘Real-Time’: Exploring Papuan Mobilities, Temporalities, and Religiosities, edited by Martin Slama and Jenny Munro, 59–94. Canberra: Australian National University Press. http://press.anu.edu.au/titles/from-stone-age-to-real-time/.

- Stasch, Rupert. 2015b. How an Egalitarian Polity Structures Tourism and Restructures Itself Around It. Ethnos, 80(4):524–547.

- Stasch, Rupert. 2016. Singapore, Big Village of the Dead: Cities as Figures of Desire, Domination, and Rupture Among Korowai of West Papua. American Anthropologist, 118:258–269.

- Stasch, Rupert. 2021. Self-Lowering as Power and Trap: Wawa, ‘White’, and Peripheral Embrace of State Formation in Indonesian Papua. Oceania, 91(2):257–279.

- Street, Alice. 2012. Seen by the State: Bureaucracy, Visibility and Governmentality in a Papua New Guinean Hospital. The Australian Journal of Anthropology, 23(1):1–21.

- Suryawan, I Ngurah. 2020. Siasat Elite Mencuri Kuasa: Dinamika Pemekaran Daerah di Papua Barat [Elite Tactics for Stealing Power: The Dynamics of Territorial Redistricting in West Papua]. Yogyakarta: Basabasi.

- Sykes, Karen. 2001. Paying a School Fee is a Father's Duty: Critical Citizenship in Central New Ireland. American Ethnologist, 28(1):5–31.

- Tammisto, Tuomas. 2016. Enacting the Absent State: State-Formation on the Oil-Palm Frontier of Pomio (Papua New Guinea). Paideuma: Mitteilungen zur Kulturkunde, 62:51–68.

- Timmer, Jaap. 2007. Erring Decentralization and Elite Politics in Papua. In Renegotiating Boundaries: Local Politics in Post-Suharto Indonesia, edited by Henk Schulte Nordholdt and Gerry van Klinken, 459–482. Leiden: KITLV.

- Timmer, Jaap. 2010. Being Seen Like the State: Emulations of Legal Culture in Customary Labor and Land Tenure Arrangements in East Kalimantan, Indonesia. American Ethnologist, 37(4):703–712.

- Vel, Jacqueline. 2007. Campaigning for a New District in West Sumba. In Renegotiating Boundaries: Local Politics in Post-Soeharto Indonesia, edited by Henk Schulte Nordholt and Gerry van Klinken, 91–119. Leiden: KITLV Press.

- Vel, Jacqueline, Yando Zakaria & Adriaan Bedner. 2017. Law-Making as a Strategy for Change: Indonesia’s New Village Law. Asian Journal of Law and Society, 4(2):447–471.