ABSTRACT

This article explores how efficiency—a seemingly universal economic narrative—traverses through the realm of diverse economies via the efforts of Qoin, a Dutch social enterprise specialised in designing alternative currencies. Such currencies in North-West Europe are, by and large, professionally designed and instituted via cross-sectoral partnerships of private enterprises, public sector organisations, and municipalities. Hence for these alternative currency practitioners, corporate standards have become the backbone whereupon ideals, expectations, and visions of society are articulated. This article focusses specifically on efficiency; although central to neoliberal capitalism, the notion is rarely critically examined in anthropology. The ethnography of Qoin’s alternative currency provides an instance of how the work of economic alterity becomes entwined with, yet not necessarily co-opted by, logics of market efficiency. What emerges is a different ontology of efficiency: rather than being predicated on values of competition, the social efficiency Qoin aims for means cooperation on various levels.

Introduction

The Dutch consultancy firm QoinFootnote1 aims to transform local economies and civil society by transforming money. The small team, based in Amsterdam, works to implement an alternative currencyFootnote2 by engaging in intense interactions with municipalities, public institutions and businesses, as well as with financial legislation and regulatory bodies. Whereas alternative currencies have been researched primarily as grassroots systems of finance creating heterogeneous economic spaces (see Gibson-Graham Citation2006; North Citation2007), this social enterprise designs, builds and manages city currencies that explicitly interact with established actors in society and economy. This article explores how an alternative economy is managed through the terms and parameters of a business. I specifically detail how efficiency, as a central rationale of businesses, is understood and applied differently by discussing one of Qoin’s currencies, called the WoolsePas. How is efficiency manifested in attempts to build a diverse local economy?

Efficiency is an intriguing notion to ‘follow’ (Marcus Citation1995), because it is both a trope of bureaucratic (corporate) rationalities (Weber Citation[1922] 1978) as well as of principal market mentalities (Hayek Citation1980; Friedman Citation1962). Today, efficiency is a seemingly non-negotiable law: it is rarely questioned and its meaning is assumed to be a transferable, natural fact. Moreover, as economist Richard D. White JR (Citation1999) observed already two decades ago, ‘the close entwinement of efficiency and rationality have separated the discourse on efficiency from social values’. Simultaneously, most analysts of heterodox economies (for example Caldwell Citation2000; Hart, Laville, and Cattani Citation2010; Gregory Citation1997) have located alternative currencies in the sphere of the moral economy—thereby illustrating the division that long haunted economic anthropology (see Hann and Hart Citation2011; Zelizer Citation1994, Citation2005) where money draws the morally charged boundaries between exchange (the market), redistribution (the state) and reciprocity (the community). This article takes a different approach by showing how efficiency, a central tenet of modern life, is apprehended and applied variously in the creation of an alternative economy.

Practices in diverse economies lay bare the silent assumptions and paradigms in the way economies function. The consultancy work of Qoin emphasises that efficiency is always a relationship; it represents a ratio between what is valued as costs, and what is valued as benefits. As such, it means different things in different contexts. Indeed, the work of alternative currency practitioners shows how it is, in fact, construed as a trade-off between values that do not necessarily follow the logic of capital. Rather than being a contextually transferable, natural fact of economising logics, I argue that there are various ontologies of efficiency at play in the enactment of economy and society.

The article also provides an ethnographic window into the changing local currency landscape in North-West Europe. The discussion is based on my PhD research (Kanters Citation2021), particularly thirteen months of fieldwork (January 2016 – February 2017) in the Netherlands, during which I worked as a ‘currency consultant’ with Qoin.Footnote3 Founded in 2008 by two pioneers in the Dutch alternative finance landscape, Qoin is now one of the key service providers in the European local currency field, which is increasingly geared towards professionally designed, city-wide implemented, and financially sustainable currencies. Besides the WoolsePas, Qoin has been involved in the Bristol Pound and the Brixton Pound (United Kingdom), SoNantes (France), Troeven (Belgium), and the time currency Makkie in Amsterdam. These currency schemes, along with numerous other initiatives in Europe, demonstrate that alternative economies do not float in a liberated, non-capitalist, space, but are thoroughly institutionalised in the discourse, practices and processes of states and markets.

As such, I depart from earlier analyses by currency researchers and the ‘diverse economies’ research agenda (e.g. Dodd Citation2016; Gibson-Graham Citation1996, Citation2006; Greco Citation1990; Lietaer Citation2001; North Citation2007) who stress that alternative currencies present a route towards a moral economy beyond financial and political regulatory capture. Similarly, I argue that the anthropological critique that money is imbued with social meaning, rather than being an abstractifying market force (e.g. Akin and Robbins Citation1999; Graeber Citation2011; Guyer Citation2004; Hart, Laville and Cattani Citation2010; Maurer Citation2005; Zelizer Citation1989, Citation1994), side-lines the plurality of actors and institutional frameworks that work to regulate and manage economic flows. I show that, rather than operating in a political and regulatory void, alternative currencies move alongside the networks of power and control that permeate economies. This institutional perspective draws attention to the prevalence and centrality of corporate agency in regulating economic life.

By unpicking the ontology of efficiency, I uncover, not only how alternative currencies might be hindered or ‘co-opted’ by the very economic structure they aspire to change, but also how, in a number of ways, they work with and through this system to reach their goals. As such, the ambition of this article is to delineate how the social might be made efficient by disentangling efficiency from the container category of neoliberalism. The first section briefly situates the WoolsePas in relation to my inquiry into efficiency within a broader framework, introducing the perspective of managerial governance in order to capture efficiency ethnographically. The ethnography then examines the way Qoin’s alternative currency frames communities of citizens—and society at large—as companies which should be made more efficient and, in the process, recalibrates the values attached to what it means to be classified as such.

Efficiency as a Managerial Strategy

The project team of the alternative currency the WoolsePas, Renee, Jasper and me, stare at a flip chart, where CEO Nico just drafted the juridical bodies that together will operate as Qoin’s latest alternative currency.Footnote4 We are in the principal meeting room of Qoin, one floor down from the main office space in Amsterdam. Behind the massive wooden table, the entire wall portrays larger-than-life cows eating wads of bright green grass against a blue sky. The mural probably serves to draw attention away from the windows looking out onto an uninspiring gas station and parking lot. Today, however, the view is almost obscured by a grey drizzle typical of Dutch winters. Currently we are looking at neither, as we try to solve the puzzle of not only Nico’s handwriting, but the complex of responsibilities and risk-spreading between two organisational forms, the social enterprise Qoin, and the local government of the Dutch municipality Woolse as they set out to collectively implement an alternative money. The WoolsePas, as written in the project plan, intends to be ‘the “new money” of Woolse: an innovative social enterprise offering City Marketing, a Loyalty programme and a regional payment system aimed at strengthening the social economy of Woolse’.

This new local currency in a quiet, countryside city near the border with Germany is typical of Qoin’s ‘build once, deploy many’ approach. This means that their digital currency platform has been developed once, to be implemented and adjusted according to the needs and desires of any locality. In their business statements, Qoin writes: ‘after several concentrated one-off investments, Qoin has a service at its disposal which can be deployed multiple times against minimal costs in different environments’. This service is called CAAS: Currency as a Service. The CAAS documentation specifies that it includes ‘a fully operational ICT system, an implemented legal structure, administrative and financial processes, and a helpdesk’. Qoin is a for-profit enterprise and they position themselves as currency professionals, calling themselves ‘specialists in regional economies’, who develop business cases for potential users—with a price to match. Dependent on the business case of the customer, the basic costs of CAAS are about €50.000 per year.Footnote5 The alternative money is fully digital and sold as a commodity in a marketplace.

To be sure, the connection between money and markets has featured prominently in scholarship about money and the economy (Callon Citation1998; Hart Citation1986; MacKenzie Citation2008; Miyazaki Citation2013; Slater and Tonkiss Citation2001). Yet the ways in which money developed as an institutionalised project has, by and large, been overlooked in anthropological analysis.Footnote6 The focus has been, instead, on moneys ‘repertoires, pragmatics, and indexicality’ (Maurer Citation2006: 30) through everyday encounters and regimes of value. Such an approach does not question, and hence effectively upholds, some naturalised connection between money, markets and neoliberalism. Alternative currencies, in turn, have been largely understood as antithetical to both markets and state (Gibson-Graham Citation1996, Citation2006). However, for one, as legal historian Christine Desan argues in in her account on making money in the English world (Citation2015), modern money arose as a ‘highly engineered project’, rather than ‘the happy by-product of spontaneous and decentralised decision’ in free markets (Citation2015: 8). And, second, not only modern money but alternative currencies, too, are—legally, economically, and culturally—highly institutionalised. By drawing attention to the institutional design and managerial organisation of the WoolsePas, rather than providing an ethnography of its use and users (see Guyer Citation2004; Maurer Citation2005; Zelizer Citation1994), I seek to outline how money is imbued with value by way of its very design and management.

The way the WoolsePas is developed and instituted through CAAS deploys a particular ‘managerial governance’ (Hathaway Citation2020; Knafo et al. Citation2019), which redefines the relationships between different actors in the marketplace. It does so, as I will demonstrate throughout this article, by redefining what it means to be efficient. If we think of efficiency as a purposeful process to reach a particular goal, it becomes possible to disentangle the term from the neoliberal rationalities it is usually equated with (Peck, Theodore and Brenner Citation2012). In fact, as Quinn Slobodian shows, the notion of neoliberalism itself as a logic or rationality intent on unshackling the market from any constraints is mistaken. ‘The neoliberal project’, he writes, ‘focused on designing institutions—not to liberate markets but to encase them’ (Slobodian Citation2018: 2). In line with Slobodians argument (Citation2018) that the role of governance has been systematically neglected in intellectual histories of the neoliberal project, I track efficiency as one element that is usually equated with ‘neoliberal rationality’—revealing as such how its goal, the parameters to reach it, and the decision when it has been met, are in fact managerial decisions. Moreover, I maintain that these decisions are not necessarily imbued with the values of competition and profit.

Efficiency is a highly elusive term that travels across social fields and academic disciplines and comes to mean slightly different things in each domain. These nuances are rarely noted, perhaps because it has become a common-sense term. Its meaning, however, is not neutral. Efficiency, from the Latin ‘efficere’, is etymologically bound to the presence of an operative agent through the verbs ‘to bring about’, ‘to accomplish’, and ‘to execute’ (Jollands Citation2006: 360). Early theological use of efficiency refers to control and purposefulness as properties of God being ‘the prime mover’ (Karns Alexander Citation2008: 9; see also Jollands Citation2006). This agency then shifted in the spirit of the Enlightenment to the scale of human agents and machines. When experiments on waterwheels in the late 1700s established that managing the movement of water is key (Karns Alexander Citation2008: xii), efficiency became a force expressing and controlling the (optimal) operation of a machine. Its current use, as a controllable ratio between energy input and energy output within deterministically balanced systems (Saslow Citation2020), stems from nineteenth century developments in classical thermodynamics and mathematical physics.

This root meaning of efficiency, involving both purposefulness and motion control, reverberates through the formalisation of the concept in machine design and its broader applications in economics and society. Yet importantly, in these applications, purpose is collapsed onto efficiency itself, so that efficiency is the purpose rather than a means to achieve a particular purpose set by an operative agent. To be sure, the fundamental assumption of thermodynamics, that systems tend towards equilibrium, became reflected in the notion of the rational, and hence efficient, tendency of markets. This is particularly evident in neoclassical conceptualisations of power and power relations in free markets, where businesses emerge—almost ‘naturally’—because it is the most efficient way to organise the distribution of resources: firms exist because of the free market (Coase Citation[1937] 1991; Friedman Citation1962). Businesses, noted both Hayek (Citation1980) and Friedman (Citation1962), should compete on the basis of efficiency and prices. Indeed, in the Chicago School,Footnote7 monopolies and oligopolies became sanctioned by virtue of being efficient businesses and therefore beneficial to consumer welfare (Hathaway Citation2020). These are moral arguments that obscure agency in economic decisions.

If efficiency bridges, or glues together, organisational processes with free market mechanisms, surely anthropology would have something to say about efficiency in corporate culture, values, beliefs and rituals? Alas, in anthropological studies the notion of efficiency is obliquely mentioned, and understood as simply a means for neoliberal ends; namely ‘a matter of rational deliberation about costs, benefits and consequences’ (Brown Citation2003: 15, quoted in Muehlebach Citation2012: 24), fuelling competition under free market ruleFootnote8 (Peck Citation2010; Brown Citation2015; Davies Citation2014). Money, here, is a tool enabling this kind of efficiency. Carrier (Citation2016) argues that anthropological analysis has come to share, often too intimately, a particular footing with neoliberal economics. Here too, businesses are too often seen as an extension of the neoliberal project and, in both laudation and critique, efficiency is uncritically collapsed onto the notion of (market) competition.

Another approach, I suggest, is to investigate efficiency ethnographically, as a managerial strategy. I stress that efficiency, as ‘an intellectual artefact, as doctrine or as ideology’ (White Citation1999: 8), is central to understanding how economies function—and particularly how they are managed. Efficiency is not ‘the ghost in the machine’, but concerns the purposeful management of an economy in motion. This ‘managerial governance’ is predicated on shared imaginaries and practices, artefacts and routines. I propose this perspective in order to grasp what it means to envisage and manage an alternative economy through the terms and parameters of a business.

Discussions in political economy on the misrepresentation of corporate agents in economies (Hathaway Citation2020; Knafo et al. Citation2019) provide an avenue for analysing the professionalisation of alternative currencies as they strive to become ever more ‘business-like’. The perspective of managerial governance is rooted precisely in disentangling the rationale of firms from the notion of free markets by unearthing the history of businesses. ‘The firm’, as a distinct entity in modern society, was established through the work of Peter Drucker (Citation1946), who described it as ‘a social institution organising human effort to a common end’, whereby its purpose does not lie ‘in its economic performance or in its formal rules but in human relationships both between the members of the corporation and between the corporation and the citizens outside of it’ (Citation1946: 12–13). Indeed, Drucker (Citation1946: 253) emphasises that the notion of an absolute and universal market ignores organised society and decision-making. Disputing the assumption that firms exist because of the free market (Coase Citation[1937] 1991), includes a different theory on the relationship between firms and efficiency.

Historian Alfred Chandler (Citation1977) situates the rise of what he calls ‘managerial capitalism’ and the vertically-integrated business enterprise in the United States of 1840-1880—long before the term neoliberalism was coined. Moreover, other than vaguely defined understandings of efficiency as embedded within the invisible hand of market mechanisms, Chandler (Citation1977) exposed the centrality of ‘the visible hand’ of hierarchically managed firms by achieving efficiency through coordination. The majority of economies, he stated, ‘result from the careful coordination of flow’ (Citation1977: 490). Similarly, Knafo et al. (Citation2019) detail the development of managerial governance as an ‘expertise of decision-making’ which ‘had much more to do with empowering policy-makers and top managers than with a neoliberal project focused on instituting markets, or market competition, as a tool of social regulation’ (Citation2019: 236). Born in the defence sector and meant for large corporations in post-war US, a scientific approach to management provided managers with tools for benchmarking and standardisation—such as cost-benefit analysis and key performance indicators—to actually determine what their objectives were in the first place and set out the most efficient way to reach these objectives. In other words, managerial governance arose as a way to foreground decision-making about ‘which course to follow’, rather than ‘simply optimising a given operation’ (Knafo et al. Citation2019: 241). Managerial governance is a set of social technologies concerned with operating an enterprise and pursuing its interests—which are not necessarily about generating profit or competing on markets (Eagleton-Pierce Citation2020: 6; Drucker Citation1946). This is key.

Rather than positing a dichotomous conceptual framework wherein a straw man of neoliberalism (Slobodian Citation2018) is pitted against its alternatives (what), my approach is concerned with the how and the who. It directs attention to the agents enacting governance within economies. These are, to a large extent, organisations and their managers. I transpose the perspective of managerial governance onto the ethnographic present—namely the enterprise of alternative currencies—to argue that their managerial rationalities cannot, and should not, be analysed in oppositional terms. Instead, I highlight ‘efficiency’ as a route to understand how Qoin employs their managerial structure to determine which course to follow in the implementation of an alternative currency.

This is an act of ‘interdisciplinary redefinition’ of efficiency (Repko and Szostak Citation2020: 336), rooted in ethnography. I delineate efficiency as a value-laden ratio, a moral judgement made by managing agents, which requires careful ethnographic attention. In what follows, I discuss Qoin’s drive to become a ‘proper business’ and I outline the legal framework within which Qoin operates. Understanding how the WoolsePas is legally embedded clarifies how and why its operational design is structured the way it is. What I call its ‘ontology of efficiency’ should engender cooperation between stakeholders: an amalgam of local companies and institutions such as nursing homes, sport conglomerates, as well as the municipality. According to Qoin, cooperation is brought about by a particular managerial structure, which should engender inter-institutional conversation in order to withstand the monopoly forces of the global economy.

Running a ‘Proper Business’

The get-together between me, Renee, Jasper, and Nico in Qoin’s principal cow-decorated meeting room had been planned in our Outlook agenda’s in advance. We brought white mugs of freshly made coffee and tea into the room, placed our notepads and laptops on the table, and arranged ourselves according to the hierarchy of the WoolsePas project team: three employees facing Nico, the CEO, who stood next to a flip chart wearing a chequered shirt and smart jeans. He explained, we asked questions and wrote down to-do lists to be checked off before the next meeting. These were all the protocols, rituals, and behavioural rules that ‘fit’ a professionally-run business environment. Qoin’s directors and employees work very hard to professionalise their operations according to well-established ideas of what it means to be, in Jaspers’ words, ‘a proper business’. This is a continuous and laborious process that profoundly defines office relations; particularly those between management and staff.

During my time as currency consultant with Qoin, I came to know its team as young, impact-driven, idealists; all of them deeply loyal to the company’s cause. ‘Although we work in the economic sector’, one of the employees had told me, ‘none of us are economists. Most of us are political scientists and we all work with ideals. What drives us here has many reasons, but mostly we want to have a positive impact on the world.’ This impact, they feel, is best achieved if the organisation functions ‘as efficiently as possible’. Yet Qoin’s founders, Nico and Gerard, did not originally envisage they would operate a local currency model through an incorporated organisation, and often struggled with their formal tasks as management. During our first interview together, Qoin’s technology director Brian reflects on the central place this development continues to have within the team:

[…] if you look at Qoin’s history actually I mean […]. Nico quite often has said to me that he and probably Gerard, they probably never imagined that they would be running an organisation in this way. So they were both individuals who wanted to do this kind of work, and sort of accidentally ended up with a larger organisation without really knowing how to effectively manage it. So I think there has been a lot of wasted effort and inefficiency over the years. We are just slowly figuring out how to improve, but it is an open question whether it is changing fast enough.

In Amsterdam, the team at Qoin acts upon these difficulties by stressing that increasing organisational efficiency would greatly benefit their performance. Qoin’s directors responded by introducing more procedures, rules and norms according to corporate logics—not leaving management to common sense, but moving towards a managerial governance and executive decision-making based on facts (Knafo et al. Citation2019). Gerard explains the ways in which he and Nico work to transform the company: ‘It has been a profound transition from a subsidy-driven organisation to a for-profit enterprise. We are formalising our operations; starting at 09.00 am on Mondays; deepening our professional framework.’ For Qoin, the path towards becoming a professionally functioning entity is paved with corporate logics of efficiently organising work.

Simultaneously, however, there is a discourse of resistance within Qoin to the very same capitalist framework that glorifies efficiency as the rational approach to increasing accumulation and a disposition of ‘survival of the fittest’. Gerard once lamented there is little space for anything beyond economising in the current economy: ‘fundamental to everything we do at Qoin is changing this paradigm.’ Gerard is particularly critical of the growth-impetus at the core of the economy, and its competitive behaviour. The organisation attracts employees who share this same value system. Seeing a changing world facing many crises, Qoin’s team aims to improve the social and economic resilience of communities because, to them, capitalism is a faulty system that does not work. ‘None of us wants to work in an irrelevant place’, they tell me. During lunch I prompted Frank, the newest addition to Qoin’s management team, on the workings of the mainstream economy. He said, ‘Its efficient, definitely, but what is it efficient at? I’ll tell you. Increasing wealth-gaps. Making people hungry. Individualising societies.’ This is a pointed critique of efficiency as a neoliberal technique and ideology wherein competition is a core concept.

In order to grasp the particular reality that is brought about through this efficiency-paradox (aspiring towards efficiency whilst critiquing it), in the section that follows I focus on the product Qoin aims to bring about, which is a particular social, economic and physical space that is facilitated by their alternative currency. I aim to emphasise a conceptualisation of efficiency as a means to best enact and achieve ideals and values—wherein neither competition nor market share are central values. Early management theorist Chester Barnard (Citation[1938] 1962) states that efficiency is about the way resources are exchanged: it is a process.

Where productivity is about increasing output, efficiency at its core refers to a process; a way of doing things in such manner that the end result is produced with the least amount of waste of time, energy and materials along the way. So what does it mean to say that economies are efficient? Importantly, what is considered efficient or inefficient depends on what is considered wasteful in relation to the best possible way to achieve the particular end result around which corporate processes are organised. For Qoin, the end result is an efficient economy—a way of exchanging resources—as much as it is for neoliberal imaginings of the economy. Yet these are efficiencies of a different kind, which bring about a different reality, and have different forms of socially binding consequences (Butler Citation2010: 147); hence it is about different ontologies of efficiency.

In addition to attending to the specificities of alternative-currencies-as-enterprises, which institute a particular kind of economy, without ‘backsliding into a general critique of capitalism (or neoliberalism instead)’ (Foster Citation2017: 112), this foray into efficiency is a way to re-entwine the distinction Urban and Koh (Citation2013) have made in their analysis of the anthropology of corporations. In their much-cited review they identify one body of ethnographic work that focuses on the inner dynamics of businesses, and a second body of work that is concerned with the impact corporations have on their wider socio-cultural and economic environment. As such, the analysis of firms in anthropology misses the crucial perspective that the managerial governance I described above does provide: corporations are, in a very real empirical way, agents; they act upon their environment from a particular position that is informed by their inner values, beliefs, rites and stories. Indeed, as Welker, Partidge and Hardin (Citation2011: S6) note, ‘corporate forms can be put to many uses besides being vehicles for the accumulation of wealth’ (see also Maier Citation1993; Drucker Citation1946). One example is the social enterprise, which Sherry Ortner (Citation2017: 531) defines as ‘a type of business that actively seeks to do good works within a capitalist framework’. Yet the agentive power of the firm in shaping social realities is rarely scrutinised, neither have the consequences of organising an alternative currency as a social enterprise been explored. It is through this dynamic, then, that I trace efficiency as it translates from internal managerial processes and values into the socio-economic community work of Qoin: instituting an alternative currency.

Incorporating the WoolsePas

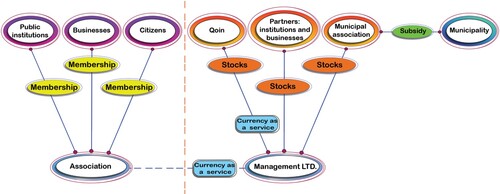

Let us return once more to that meeting room adorned with cows, where tiny raindrops now create intricate pathways on the windows as they slide down. Renee pours herself another cup of tea; Jasper rearranges a tress of black hair, damp from smoking outside. What Nico is explaining to the consultancy team of the WoolsePas is the legal structure which Qoin developed for the implementation of an alternative currency in Woolse. The structure consists of two new organisations: an association and a limited company.Footnote9 These entities are connected to each other and a range of other actors through a complex of monetary flows and responsibilities. This legal structure, ‘the WoolsePas consortium’, stipulates the—very real, though not physical—borders of the community by including certain actors and not others; such as ‘local’ companies and not multinationals; urban citizens and not those who live outside of the city; and public institutions that work in local service provision, such as nursing homes and various sport associations. The drawing Nico drafted on the flip chart eventually became digitalised [Footnote10].

Everyone who uses the currency in any way, is included as actor in one of the white ovals in the visualisation. For example, using the local currency as a citizen means that you will automatically become a member of the Association. All financial and decision-making partners in Woolse, moreover, hold a financial stake in the Management ltd. This means that, through the very design of the alternative currency, the image of ‘the community’ is recast in the image of a company; the epitome, as Roland Coase would say, of efficiently organising the distribution of resources.

The reason for such a structure is to comply with financial legislation and to attain financial sustainability, effectively recasting community relationships. I will show how the alternative currency introduces a particular notion of efficiency that weaves through this renewed, formalised and bounded community. First, however, it is important to understand the conditions that require Qoin to implement and manage an alternative currency in the shape of a business consortium: why and in what way is it formalised and bounded? There is one key legal article that lies at the core of the answer:

It is illegal in the Netherlands to attract, attain, or hold outstanding financial claims which belong to others than professional market parties while running a business outside of closed circles. [my translation]

The WoolsePas holds a deposit fund that contains the counter value of circulating alternative currency in euros. As a miniature central bank, this is how the consortium issues an alternative currency and manages the way it flows. However, the law stipulates that convertible digital money of any kind is a form of electronic money. And all electronic money is regulated by the Wft. Qoin’s efforts concerning compliance are completely directed at ensuring regulation by the DNB or AFM will not label the currency as outstanding financial claims, so that the WoolsePas is not audited.Footnote12 Crucially, not being audited is not equivalent to not being regulated. The financial regulations demand, effectively, the institution of an alternative currency through a consortium of legal persons.

The WoolsePas is therefore designed precisely so that transactions in alternative currency occur within closed circles. The Wft defines the notion of a ‘closed circle’ in article 1.1. as ‘a circle, which consists of persons or companies of which a person or company receives financial claims’ [translation mine]. The closed circle is further elaborated upon in article 1.5a, which defines cases that are not considered a ‘payment service’ and therefore are exempt of regulation:

Conducting payment transactions to buy goods or services that are executed with payment instruments that can be solely used … on the grounds of a trade agreement with the issuing institution within a limited network of service providers for a limited number of goods and services. [translation mine]

Institutionalising Cooperation

‘The theory is a simple one’, says historian Morgen Witzel, ‘efficient businesses survive while inefficient ones go to the wall’ (Citation2002: 38). There is no doubt that efficiency, interwoven with productivity and profitability, is a core business value. So too for the business of alternative currencies such as the WoolsePas—yet not in the way efficiency is typically understood. As I recount below, the need for financial stability, or profit, of the scheme is wound-up with a particular managerial structure that is steered towards engendering positive societal change through economic cooperation at a city scale.

Nico is clicking swiftly through the slides of his PowerPoint, glasses balancing on the tip of his nose. I am walking around him, arranging chairs alongside a long table. Everything in the room is of the deep, dark wooden colour that characterises traditional Dutch pubs, or bruine kroegen. The atmosphere breathes a certain warmth, similar to a living room where friends and family gather in an intimate setting. This morning, the project team of WoolsePas travelled from Qoin’s office in Amsterdam to the eastern, more rural part of the Netherlands where Woolse is located. It is an important day, because the stakeholders of the WoolsePas will come together to discuss the plans and progress of the alternative currency in their city. The patron of the pub is an avid supporter of the initiative, and has agreed to host the meeting in his establishment.

Soon, people start to trickle in and Nico gets up from his seat to welcome them enthusiastically. The guests greet each other with handshakes and amicable pats on the shoulder and find their spot around the table: the manager of the local housing institution; representatives of different fractions of the municipality; the CEO of the social work agency; local business owners; the representative of a volunteer agency. Woolse is not a large city, so they know each other’s position and faces; yet it is quite extraordinary that they have all come together in a local pub this afternoon. Slowly, the chatter quiets down. Nico kicks off the meeting by reiterating the crucial role of money in society as a social technology, and the benefits of preventing value from leaking away from Woolse. He reminds his audience of why they are all here, together. Why would a municipality purchase an alternative form of money from a consultancy firm? Which logic justifies spending a portion of the—increasingly dwindling—budget of public institutions on implementing an alternative currency? Nico touches upon all these points:

[Our] currencies are interesting first because they channel decisions and actions of people. On top of that, they incentivise a particular social organisation. Citizens taking more action, taking care of each other and the environment […] a currency can be designed for example to meet the policy goals of retreating governments with little budget. The currencies have incentives to create a closer community, so together they reach their goals. It is much more efficient.

The financial security of the alternative currency in Woolse pivots around the for-profit enterprise I have called Management ltd.: this legal person holds the actual ownership of the currency model in the city and the prospective board consists of a selection of the very people that came together in the pub in Woolse. The holding is intended to secure financial sustainability in the long run by introducing the possibility of investment and the need for profit. In the project plan Jasper devised together with Nico, the aims of Management ltd. are outlined as follows:

The company aims to strengthen the community of Woolse. This is done by helping to build a community where people, businesses, governments and institutions can make a meaningful impact on social, economic, or environmental areas. These goals are achieved through the exploitation of a community currency platform. [emphasis mine]

First, businesses and institutions pay a fee to be a member of WoolsePas because it brings them financial benefit: ‘more customers, more profit’, says a flyer of the currency model in a different city. Second, Qoin strongly believes capital should be generated through investments. This means the investors need to be able to retrieve their investment as well as be compensated for their risk. It follows that, in the words of Chief Currency Officer Gerard, ‘the most efficient way to arrange such a set-up is through the creation of a holding, which supplies stocks over which dividend is received.’ Investors co-own Management ltd. and can receive dividend over their shares. Hence there needs to be a return on investment. In other words: the alternative currency in Woolse brings profit to its users and also needs to generate profit by itself.

Such developments might easily be analysed as an instance of commodification, of the neoliberal steamroller hijacking creative innovation once again (Brown Citation2015). It is true that Qoin promotes the local currency by emphasising the various ways in which it smoothens, eases and accelerates the internal business processes of participant institutions. As such they offer a Weberian type of efficiency, somehow interchangeable with rationality as well as financial gain. Yet, the reality of what it means to be efficient for Qoin is more complex than our general assumptions of the term. The efficient management of alternative currencies is one that interlaces, explicitly, the financial with the social. Indeed, to Qoin, and to the institutions of Woolse, profit is not the ultimate goal.

In outlining their core business, Qoin notes that they offer a solution for local authorities and institutions, who face pressure due to a restructuring state; small and medium sized enterprises, who need new ways to connect to their market due to competition of global markets in the form of chain stores and online shopping; and civil society organisations, who need new business cases in a difficult financial context. These actors tend to work towards their own interests in their own domains. It is Qoin’s premise that having them work together to align their interests into a greater goal of creating stronger communities, it is possible to better serve these primary interests and simultaneously achieve positive socio-economic change on a local scale. As a Qoin consultant mentioned: ‘What I like about [our currency] the most is the merging of different interests. Through a complementary currency mutual advantages can be created. As such, we open possibilities for unusual collaborations.’

The idea is that Management ltd. works to bring together a variety of partners within the city, who contribute to the foundation of local knowledge that Qoin considers necessary for the successful implementation of the currency. This structure, they argue in the project plan, produces ‘a shared responsibility for creation of the platform and local excitement so that institutions, businesses and citizens will use the program’. In their practitioner literature ‘People Powered Money’ (NEF Citation2015: 118), my interlocutors write:

A currency project’s organisational structure should reflect the values that the currency represents. Broadly speaking, this requires a governance structure that brings stakeholders together to participate in dialogue, decision-making, and the implementation of solutions to common problems or goals.

As such, through incorporation, the Amsterdam-designed monetary framework becomes locally owned and directed. By holding stocks in Management ltd., the cash flow major companies or institutions bring into the currency also entrenches their interests, values and goals into the design and course of WoolsePas. I have outlined how the precise way of incorporation is interlaced with values of institutional cooperation, rather than merely securing financial sustainability for the alternative currency. Because this cooperation, according to Qoin, increases efficiency. How, then, does this managerial structure work upon the communities in which it is active? The final section of this paper details how efficiency is a value-laden ratio, decided upon by managers.

Valuing Efficiency

Rather than being a grassroots citizen initiative, WoolsePas came into being as a professional organisation with institutional stakes. It is managed through a consortium of local institutions, businesses, and the project management. These institutions are approached by Qoin as interlocutors and managers of local economic life. As such, they are financially most intensively involved and determine the strategy of WoolsePas, assess its results, and decide upon its operational plans. Individual users of the currency are not consulted or included in these decision-making processes. Yet, the figures of ‘the citizen’, ‘the tenant’, and ‘the volunteer’ are at the core of the currency’s aims. More specifically, the networked behaviour of the collective forms the deliberate object of change, consistent with the thesis that societal change means changing how people relate to each other through institutionalised ways (Douglas Citation[1987] 1994). The actual goal of WoolsePas as a governing practice is to shape the conduct of institutional practice. To be sure: through the discourse of efficiently organising the local economy, it is public and private sector organisations that start to regulate and frame their own behaviour in terms of added communal, social, value.Footnote13

Qoin’s notion of ‘value proposition’ renders visible how their currency model aims to align the individual interests of institutions and other partners into a cross-sectoral common purpose that brings positive socio-economic change. All stakeholders join the project from the perspective of their own goals, desired actions, and timeline. This can (and has) result(ed) in tensions or mismatched expectations. For example, a municipality works at a different timeline than a business would. Resolving these rhythms requires the consolidation of each of the stakeholders’ stake in the project. Value propositions are, quite literally, the added value that according to Qoin, stakeholders and users should experience when using the alternative currency. They are story lines, anecdotes in a cause-and-effect form, describing which challenge is solved, or how a situation was improved for each separate stakeholder; stating the (in)tangible advantages of the WoolsePas over using euros. Hence there are value propositions for the housing sector, the care sector, municipal services, schools, culture- and sports clubs, and waste management companies. I paraphrase an example of Qoin’s cause-and-effect narrative for for-profit businesses:

[T]he business shows social and regional commitment. As such it also is a more effective marketing mechanism than other outlets. Citizens and charities find your shop through the platform … Existing customers become more loyal and buy more. The improved image, together with new customers and more loyal customers, results in more sales.

For a non-profit institution, like a nursing home, the story goes like this:

The possibility to reward volunteering work results in citizens volunteering more often and doing more and diverse tasks. This reliefs workload pressure for professionals, who now have more time for specialised tasks. This improves service and client wellbeing. Moreover, there are less operational costs as professionals are less overworked and take fewer sick days.

These value propositions show how the alternative currency is expected to increase efficiency and add value, following the logic of productivity and profit. The initial grant proposal that funded the currency model states that the programme aims for ‘economic return on social investment’. A member of the operational team explains:

Yes, the focus is on deepening added value for the partners. It sounds commercial, but that is because the declining subsidies and scarce resources and time, self-investments are crucial for all partners. In the end, using this money makes the whole community more resilient.

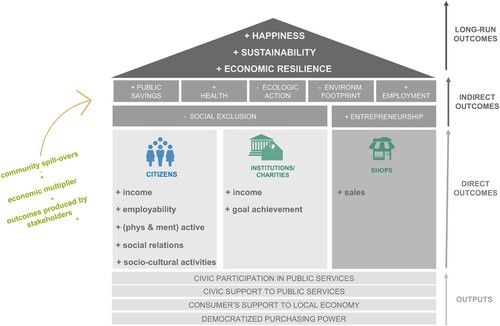

The ‘Outputs’ foundation at the bottom of the figure stipulates practical behavioural changes. These should result in direct outcomes, differentiated by type of user. Here the individualised value propositions per stakeholder are articulated; namely each stakeholder allegedly joins because the WoolsePas allows them more efficiently to reach their goals. The indirect outcomes and long-run outcomes then are visualised as gains that add up to a common purpose of social, economic and environmental resilience. Through the alternative currency, the value of entrepreneurship is strengthened and people perceive less social exclusion. This means that the value of health is increased and there are more employment opportunities. Municipalities and institutions can save money and more easily reach their goals. In the end, the ultimate goals are happiness, sustainability and economic resilience. All of these come within reach precisely because of the institutional design of the WoolsePas. The determined objective is not (only) financial gain, competition, and market rule; rather, the alternative currency becomes a managerial tool for the pursuit of public goals.

As any economic practice, the WoolsePas is infused with morality and value judgements about which goals are worth pursuing. According to this visualisation, the monetary outcomes for institutions, charities and shops are directed towards intangible indirect and long-term outcomes such as health and less social exclusion, and finally happiness, sustainability, and economic resilience. Indeed, (their) money is a measure of value. David Graeber (Citation2001) notes how money is earned, in the sense that it represents the value of one’s contribution to the community. Through the WoolsePas, this contribution is supposed to be more efficiently directed into specific behaviour, so that the collective action within the community adds to its overall resilience. This goal is complementary to, or even includes, gaining individual profit.

For example, Qoin has thought a lot about internal competition, such as when two different bakeries decide join the scheme. The narrative is that both will thrive due to WoolsePas, because the currency’s cross-sectoral networked structure uplifts the entire community. In these efforts to uplift the community, organisations and institutions are allegedly invited to set the rules for appropriate behaviour—and as such delineate their own social responsibility and activities in community building. It is precisely this central tenet of the alternative currency—namely social organisation through cooperation—that reveals a different ontology of efficiency in the work of Qoin. It is about structuring management to such an extent, that the processes it executes are as clean-cut and waste-free as possible because cooperation, both across and within sectors, is encouraged.

Conclusion

This ethnography of Qoin’s design and communication of the WoolsePas reveals the ways in which the goals and values of alternative currencies are translated into their institutional design and managerial structure. In conversation with the tight regulatory framework that defines money and steers its course, Qoin created a business model that includes networks of agents across different fields in society. Whereas studies of alternative economies tend to gloss over their institutionalisation and regulatory embeddedness, I have shown that unpicking the way in which they are embedded in (financial) regulation and existing economic structures uncovers the complexities and entanglements of (economic) values and practices. Imbuing value and morality through money’s institutionalisation is central not only to alternative currencies, but to the global monetary system as well. Morality, as Andrea Muehlebach argues, is indispensable to market orders (Citation2012: 6). This becomes evident from the cultures of financial centres such as Wall Street (Ho Citation2009) and the communication strategies of central banks (Holmes Citation2013). Moreover, morally informed decisions by commercial banks on which businesses, institutions or people receive a loan directly feed into the modern money supply: around 80 percentFootnote15 is created through such fractional reserve lending practices.

My interlocutors wish to create a new institutional environment in which money is allowed to flow; like ‘mini-me central banks’. The legal structure of Qoin’s currency model envisions a financially sustainable business model based on profit. Within this new network of institutions, corporate rationalities such as ‘efficiency’ traverse into the realm of the new economy; yet its meaning changes along the way. I showed how this difference in meaning is predicated on the concept of cooperation. As understood in neoliberal theory, market actors compete with each other by working as efficiently as possible in order to ‘survive’ (Witzel Citation2002). Here, the ontology of efficiency is the ability to reach the highest productivity or gain the most (financial) value with the least amount of resources; and failure to do so results in the business ceasing to exist because others can do it better. This means that efficiency is predicated on the assumption that growth (in productivity, in business size, in profit) is the highest achievable value and a guarantee of resilience to outside competition.

Yet it is precisely this entrenched necessity of growth and lack of diversity that Qoin criticises and hopes to change with their alternative currencies. I detailed their goal of creating a healthy and diverse local economy, by showing how their ideas and values become materialised into the institutional design and managerial governance of the WoolsePas. Through the discourse and practice of efficiency, neoliberal logics interlace with recalibrations of societal value. The problem is that competition, to Qoin, ultimately leads to monocultures (and multinationals) because it is essentially a practice of elimination. Within the WoolsePas, efficiency materialises, rather, as an attempt to connect and align; as a way for diverse actors in the economy to strengthen each other. By fundamentally being a ratio between costs and chosen values, efficiency has the capacity to contain multiple values and order them in relation to each other. This different understanding of efficiency is made visual in the model of ‘value outcomes’. Qoin’s currencies are social policy tools that wish to direct the behaviour of citizens as well as of institutions, enacting managerial governance by focusing on the logic of collaboration. The community, and the way in which it is managed, becomes more efficient because it becomes more cooperative within itself.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my gratitude to both reviewers for their insightful and constructive feedback. I presented an early version of the article at the 2019 Association of Social Anthropologists conference and thank the panellists and attendees for their generous input. The research for this paper was funded by the Dutch Research Council NWO under Grant 406-15-143, ‘Citizenship and the institutionalisation of community currencies in Europe’. Opinions expressed are the author’s own.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 I do not use a pseudonym for Qoin. However, names of individuals working for Qoin have been changed. I have also omitted the names of involved institutions.

2 I use the adjective ‘alternative’ to emphasise that these currencies are designed and managed with a different purpose and scale from conventional, fiat, currencies. My interlocutors use the same term, as well as local currencies, complementary currencies, or community currencies.

3 This ethnographic fieldwork forms part of my PhD research, for which I also worked an additional eleven months (February 2017 - January 2018) at a currency organisation called ‘The Social Trade Organisation’ in Utrecht, the Netherlands. In 2018 I spent a little over three months (February 2018 - April 2018) with the alternative currency ‘the Bristol Pound’ in Bristol, the United Kingdom.

4 In English: ‘The WoolseCard’. Woolse is a pseudonym for the actual name of the city.

5 Estimated costs based on documentation from 2015; this amount has fluctuated over the years. The actual quotation for the WoolsePas remains undisclosed per the nondisclosure agreement with Qoin.

6 The work of Christine Desan (Citation2015) illuminates precisely this institutional basis of modern money and the processes that led to obscuring its design as a monumental constitutional undertaking—a project to which anthropologists, it seems, were not impervious.

7 The Chicago School is associated with neoclassical economics, of which Roland Coase and Milton Friedman formed part.

8 See for example discussions on audit cultures, which examine the ways in which efficiency is made measurable through evaluation tools (Shore and Wright Citation2015).

9 By ‘association’ I refer to a particular legal form, which in Dutch is called vereniging. Another term for this type of collective would be ‘non-profit organisation’. I use the direct translation ‘association’ because it evokes a form of connectedness of its members (to associate) the same way the Dutch vereniging does (verenigen can be translated as to unite).

10 Structural design by Qoin; names are adapted by me to maintain confidentiality. Visual design by Harry Kanters.

11 I focus specifically on financial regulation. Fiscal law or regulations concerning labour and social security apply to the currency schemes, but are beyond my scope. In general, compliance with such regulation is also sought after but involves fewer complex structures.

12 Note that this is particular to the Dutch system. There is for example a difference with the UK regulatory framework, where the local digital currency of ‘The Bristol Pound’ is labelled as pounds sterling.

13 See also Holmes (Citation2013) on the way central banks use communication strategies to enlist the public in the execution of their aims.

14 Both the workshop and the resulting are created by Constança Morais.

15 Number based on updated information from the Bank of England (03 December 2020) webpage ‘How is Money Created?’. URL: https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/knowledgebank/how-is-money-created

References

- Akin, David & Joel Robbins. 1999. Money and Modernity: State and Local Currencies in Melanesia. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Barnard, Chester I. [1938] 1962. The Functions of the Executive. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Bohannan, Paul. 1955. Some Principles of Exchange And Investment Among The Tiv. American Anthropologist, 57(1):60–70. doi:10.1525/aa.1955.57.1.02a00080

- Brown, Wendy. 2003. Neo-liberalism and the End of Liberal Democracy. Theory & Event, 7:1.

- Brown, Wendy. 2015. Undoing the Demos: Neoliberalism's Stealth Revolution. New York: Zone Books.

- Butler, Judith. 2010. Performative agency. Journal of Cultural Economy, 3(2):147–161. doi:10.1080/17530350.2010.494117

- Caldwell, Caron. 2000. Why Do People Join Local Exchange Trading Systems. International Journal of Community Currency Research, 4(1):1–16.

- Callon, Michel. 1998. The Laws of the Markets. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Carrier, James G. 2016. Neoliberal Anthropology. In After the Crisis, edited by James Carrier, 54–77. London: Routledge.

- Chandler, Alfred D. Jr. 1977. The Visible Hand: The Managerial Revolution in American Business. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Coase, Ronald H. [1937] 1991. The Nature of the Firm. In The Nature of the Firm: Origins, Evolution, and Development, edited by Oliver Williamson and Sidney Winter, 18–33. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Davies, William. 2014. Neoliberalism: A Bibliographic Review. Theory, Culture & Society, 31(7/8):309–317. doi:10.1177/0263276414546383

- Desan, Christine. 2015. Making Money: Coin, Currency, and the Coming of Capitalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dodd, Nigel. 2016. The Social Life of Money. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Douglas, Mary. [1987] 1994. How Institutions Think. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press.

- Drucker, Peter. 1946. Concept of the Corporation. New York: The John Day Company.

- Eagleton-Pierce, Matthew. 2020. The rise of managerialism in international NGOs. Review of International Political Economy, 27(4):970–994. doi:10.1080/09692290.2019.1657478

- Foster, Robert J. 2017. The Corporation in Anthropology. In The Corporation. A Critical, Multi-Disciplinary Handbook, edited by Grietje Baars and André Spicer, 111–133. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Friedman, Milton. 1962. Capitalism and Freedom. Chicago: University of Toronto Press.

- Gibson-Graham, J. K. 1996. The End of Capitalism (As We Knew It): A Feminist Critique of Political Economy. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

- Gibson-Graham, J. K. 2006. A Postcapitalist Politics. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Graeber, David. 2001. Toward an Anthropological Theory of Value: The False Coin of Our Own Dreams. New York: Palgrave.

- Graeber, David. 2011. Debt: The First Five Thousand Years. New York: Melville House.

- Greco, Thomas. 1990. Money and Debt: A Solution to the Global Crisis. Tucson: Thomas Greco.

- Gregory, C. A. 1997. Savage Money: The Anthropology and Politics of Commodity Exchange. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic.

- Guyer, Jane I. 2004. Marginal Gains: Monetary Transactions in Atlantic Africa. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Hann, Chris M. & Keith Hart. 2011. Economic Anthropology: History, Ethnography, Critique. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Hart, Keith. 1986. Heads or Tails? Two Sides of the Coin. Man 637–656. doi:10.2307/2802901

- Hart, Keith, Jean-Louis Laville & Antonio David Cattani. 2010. The Human Economy: A Citizen's Guide. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Hathaway, Terry. 2020. Neoliberalism as Corporate Power. Competition & Change, 24(3–4):315–337. doi:10.1177/1024529420910382

- Hayek, Friedrich August. 1980. Individualism and Economic Order. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Ho, Karen. 2009. Liquidated: An Ethnography of Wall Street. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Holmes, Douglas. 2013. Economy Of Words: Communicative Imperatives in Central Banks. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Jensen, Michael C. & William H. Meckling. 1976. Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4):305–360. doi:10.1016/0304-405X(76)90026-X

- Jollands, Nigel. 2006. Concepts of efficiency in ecological economics: Sisyphus and the decision maker. Ecological Economics, 56(3):359–372. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2005.09.014

- Kanters, Coco Lisa. 2021. The Money Makers: The Institutionalisation of Alternative Currencies in North-West Europe (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Leiden University, Leiden.

- Karns Alexander, Jennifer. 2008. The mantra of efficiency: From waterwheel to social control. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

- Knafo, Samuel, Sahil Jai Dutta, Richard Lane & Steffan Wyn-Jones. 2019. The Managerial Lineages of Neoliberalism. New Political Economy, 24(2):235–251. doi:10.1080/13563467.2018.1431621

- Lietaer, Bernard A. 2001. The Future of Money: A New Way to Create Wealth, Work and a Wiser World. London: Century.

- MacKenzie, Donald A. 2008. An Engine, Not a Camera: How Financial Models Shape Markets. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Maier, Charles S. 1993. Accounting for the Achievements of Capitalism: Alfred Chandler's Business History. The Journal of Modern History, 65(4):771–782. doi:10.1086/244725

- Marcus, George E. 1995. Ethnography in/of the World System: The Emergence of Multi-Sited Ethnography. Annual Review of Anthropology, 24(1):95–117. doi:10.1146/annurev.an.24.100195.000523

- Maurer, Bill. 2005. Mutual Life, Limited: Islamic Banking, Alternative Currencies, Lateral Reason. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Maurer, Bill. 2006. The Anthropology of Money. Annual Review of Anthropology, 35:15–36. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.35.081705.123127

- Miyazaki, Hirokazu. 2013. Arbitraging Japan: Dreams of Capitalism at the End of Finance. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Muehlebach, Andrea. 2012. The moral neoliberal. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- NEF. 2015. People Powered Money. Shaftesbury: Blackmore.

- North, Peter. 2007. Money and Liberation: The Micropolitics of Alternative Currency Movements. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Ortner, Sherry B. 2017. Social Impact without Social Justice: Film and Politics in the Neoliberal Landscape. American Ethnologist, 44(3):528–539. doi:10.1111/amet.12527

- Peck, Jamie. 2010. Zombie Neoliberalism and the Ambidextrous State. Theoretical Criminology, 14(1):104–110. doi:10.1177/1362480609352784

- Peck, Jamie, Nik Theodore & Neil Brenner. 2012. Neoliberalism Resurgent? Market Rule After the Great Recession. South Atlantic Quarterly, 111(2):265–288. doi:10.1215/00382876-1548212

- Repko, Allen F. & Rick Szostak. 2020. Interdisciplinary Research: Process and Theory. London: Sage Publications.

- Saslow, Wayne M. 2020. A history of thermodynamics: the missing manual. Entropy, 22(1):77. doi:10.3390/e22010077

- Shore, Cris & Susan Wright. 2015. Governing by Numbers: Audit Culture. Rankings and the New World Order. Social Anthropology, 23(1):22–28.

- Slater, Don & Fran Tonkiss. 2001. Market Society: Markets and Modern Social Theory. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Slobodian, Quinn. 2018. Globalists. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Urban, Greg & Kyung-Nan Koh. 2013. Ethnographic Research on Modern Business Corporations. Annual Review of Anthropology, 42(1):139–158. doi:10.1146/annurev-anthro-092412-155506

- Weber, Max. [1922] 1978. Economy and Society: An Outline of Interpretive Sociology. Translated and edited by Guenther Roth and Claus Wittich. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Welker, Marina, Damani J. Partridge & Rebecca Hardin. 2011. Corporate Lives: New Perspectives on the Social Life of the Corporate Form: An Introduction to Supplement 3. Current Anthropology, 52(S3):S3–S16. doi:10.1086/657907

- White, D. Richard. Jr. 1999. More than an Analytical Tool: Examining the Ideological Role of Efficiency. Public Productivity & Management Review, 23(1):8–23. doi:10.2307/3380789

- Witzel, Morgen. 2002. A Short History of Efficiency. Business Strategy Review, 13(4):38–47. doi:10.1111/1467-8616.00232

- Zelizer, Viviana A. Rotman. 1989. The Social Meaning of Money: ‘Special Monies’. American Journal of Sociology, 95(2):342–377. doi:10.1086/229272.

- Zelizer, Viviana A. Rotman. 1994. The Social Meaning of Money. New York: BasicBooks.

- Zelizer, Viviana A. Rotman. 2005. The Purchase of Intimacy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.