ABSTRACT

Different goals and assumptions enable and legitimise the ways that climate change is understood and governed through increasingly urgent, experimental, and heterogeneous interventions. We examine the ontological politics of ‘piloting’ Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+) by weaving together stories from our ethnographic fieldwork in Central Suau, Papua New Guinea and Central Kalimantan, Indonesia. Weaving partial stories is a methodological technique to examine encounters and disputes over REDD+ activities that entangle land, livelihoods, people, non-human beings, sorcery, and carbon among other entities. We propose the term ethical distance to conceptualise and foreground how governance experimentation in REDD+ intersects with local lives in ways that can reproduce and reinscribe inequalities. By attending to more-than-human entanglements and partiality, we underscore ethical dilemmas and the need to slow down our reasoning in proposing solutions to climate change.

Introduction

Global environmental and climate objectives are translated and implemented through diverse modalities of power, logics, materials, and discursive strategies. At regional and national scales covering tropical forests in Oceania and Southeast Asia, countries like Papua New Guinea (PNG) and Indonesia have been framed as ‘frontiers’ of climate change mitigation, where multiple interventions intersect with landscapes, livelihoods, and the lives of Indigenous and forest communities (Tehan et al. Citation2017). Internationally-funded forest conservation and climate mitigation efforts are situated within frontier resource extraction and a constellation of activities, actors, landscapes, histories, and ideologies (Li Citation2007).

Endorsed by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), we approach Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+) as a form of governance experimentation. While environmental governance experiments can in some circumstances foster learning and creative practices (Braun Citation2015), they often reinscribe dominant assumptions and solutions. When the design or logic of an intervention imposes fixed categories – for example, nature/culture, non-human/human, animate/inanimate (Blaser Citation2014) – this limits or forecloses reciprocal learning and engagement with ontological differences (Blaser Citation2013b; Di Giminiani & Haines Citation2020). These 'experiments' can reproduce patterns of environmental governance that universalise categories and erase particularities (Carrier & West Citation2009; West Citation2020). This then feeds the impetus for ‘governance experimentation’ that supposedly generates new possibilities, but in practice tends to reinforce inequalities and ethical dilemmas that we explore in this paper.

A large body of ethnographic research has highlighted power asymmetries and diverse local experiences that come into friction with the global framing of REDD+ and its legal norms and discourses (e.g. Miles Citation2021; Nantongo Citation2017; Pascoe Citation2018). Many authors have identified how REDD+ projects exacerbate social tensions (Milne et al. Citation2019) and how multi-level governance processes for translating REDD+ enrol diverse actors among extractive industries and competing land claims (Astuti & McGregor Citation2017; Eilenberg Citation2015; Lounela Citation2019; Sanders et al. Citation2019). Common threads of argument have focused on the oversimplification of REDD+ ‘models’ and policy persistence of REDD+ (Asiyanbi & Lund Citation2020; Asiyanbi & Massarella Citation2020; Massarella et al. Citation2018), the disconnect between global commitments and local interventions (Bull et al. Citation2018), and the repeated failure of such models to incorporate notions of justice (Myers et al. Citation2018). However, there has been limited engagement with the ethics and ontological politics of such projects – how these interventions generate new possibilities while at the same time limiting or foreclosing other options and alternatives (Mol Citation1999).

Existing REDD+ literature has explored messy and contingent efforts to translate global environmental and climate objectives at different scales (Pasgaard Citation2015; Ramcilovik-Suominen & Nathan Citation2020; Sanders et al. Citation2017). Building on the ideas of translation in this literature, we examine how the ‘piloting’ of projects brings together different goals and assumptions in ways that are riven with inequalities and give shape to uncertain environmental futures (Di Giminiani & Haines Citation2020; West Citation2020). Collaboratively reflecting on ethnographic fieldwork at different time intervals between 2013 and 2019, we pose ethical questions about ‘piloting’ REDD+ in the Central Suau REDD+ Pilot Project (CSRPP) in Milne Bay Province, PNG and the Kalimantan Forests and Climate Partnership (KFCP) in Central Kalimantan Province, Indonesia. We ask: What kind of ethical dilemmas emerge from ‘piloting’ these projects? Through what modes of reasoning and intervention are ‘governance experiments’ performed? Ethically, what does it mean to ‘experiment’ with REDD+ and intervene in the lives of local and Indigenous peoples?

Experimenting with REDD+

REDD+ is governed through complex, heterogeneous, and experimental arrangements in developing countries (La Viña et al. Citation2016). In 2005, PNG and Costa Rica, on behalf of the Coalition for Rainforest Nations, first proposed the idea of ‘Reducing Emissions from Deforestation’ (RED) to the UNFCCC, which was subsequently adopted and expanded to include forest degradation and co-benefits for biodiversity and local livelihoods. Early enthusiasm for ‘avoided deforestation’ as a relatively ‘fast’ and cost-effective (Stern Citation2006) way to mitigate climate change and halt tropical deforestation contributed to the formal inclusion of REDD+ at the 2007 Bali Conference of Parties (COP13). Following the 2015 Paris Agreement (COP21), REDD+ implementation has continued under the UN-REDD Agency, World Bank Forest Carbon Forestry Partnership (FCFP), and bilateral partnership agreements.

Since its inception, REDD+ has been described as a ‘frontier’ of climate law (Lyster Citation2009) and an experiment of transformative climate governance (Korhonen-Kurki et al. Citation2017). While many projects have been characterised as ‘pilots’ or ‘demonstration’ activities using donor funds, some ‘for-profit’ REDD+ projects have progressed to implementation under voluntary markets. However, the rapid scaling-up of local interventions has not been realised. While it was anticipated that REDD+ ‘pilots’ would be transformative and experimental, many authors challenged the economic policy arguments and assumptions that REDD+ would be easy to implement (Howes Citation2009) due to the political economy of tropical deforestation in developing countries (Corbera et al. Citation2010; Fry Citation2008; Humphreys Citation2008). Incremental, technical and short-term measures have been justified based on ‘lessons learned’ to inform future approaches (Jagger et al. Citation2009). An emphasis on testing, trialling, and learning lessons has positioned local people and environments as the experimental subjects (or ‘guinea pigs’) of short-term pilots (Sanders et al. Citation2017). Our focus on ethical implications foregrounds the ways that REDD+ experimentation intersects with local lives and ontological politics in PNG and Indonesia.

Piloting REDD+ in Papua New Guinea

PNG has played a prominent role in international negotiations at the UNFCCC since proposing the idea in 2005. The country was seen as an ideal site for REDD+ because it has the third-largest tract of intact tropical forest in the world; approximately two-thirds of the country is covered in forest. Almost all of the country’s greenhouse gas emissions are from land use activities driven by commercial logging and oil palm plantations, while most land is held under customary land tenure (Babon & Yansom Gowae Citation2013; Filer et al. Citation2000). As a pilot country for the UN-REDD Program and World Bank FCPF, these multilateral agencies have allocated funding to build the country’s capability to implement REDD+ . The Government of PNG has undertaken REDD+ ‘readiness’ activities, including the development of institutional frameworks, organisational capabilities, and demonstration activities (Filer Citation2015).

To date, the Climate Change and Development Authority (CCDA) has been established to coordinate REDD+ across sectors, while the PNG Forest Authority (PNGFA) undertakes implementation and monitoring (Bingeding Citation2014). A national REDD+ strategy, safeguards, an investment plan to facilitate results-based payments and activities towards a national forest monitoring system have also been developed. Whilst the institutional arrangements are in place, the national REDD+ strategy is yet to be fully implemented and national policies have been critiqued for failing to consider the potential implications of REDD+ for Indigenous and forest communities (Babon Citation2014). Although the majority of the population live in rural areas and rely on subsistence agriculture (Bourke & Harwood Citation2009; Laurance et al. Citation2012), local people have had no formal role in REDD+ decision-making and limited input into the piloting of projects on their land (Cadman et al. Citation2016).

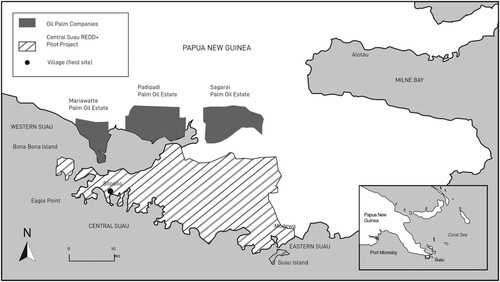

‘Testing’ and ‘demonstrating’ have been key elements of the national REDD+ programme in PNG including pilot projects. In Milne Bay Province, covering the south-eastern tip of the mainland and island region, the Central Suau REDD+ Pilot Project (CSRPP) was one of PNG’s five original demonstration sites for REDD+ . The CSRPP was proposed in 2013 ‘to test a range of REDD project types’ (SPC/GIZ Citation2013: 11). The German aid agency in the Pacific (SPC/GIZ) was the main project proponent, working alongside the PNG Forest Authority (PNGFA). The pilot project initially covered 64,000 hectares of lowland forest, comprising 23 wards and an estimated population of 7,000 people (SPC/GIZ Citation2015). Originally, it was intended to become a pilot site for Reduced Impact Logging (RIL). As there were no established methods for ‘reduced impact’ logging in PNG as a basis for carbon accounting, the focus subsequently shifted to testing ‘whether emissions would occur beyond a reasonable doubt in the absence of carbon financing; in essence whether this particular project would generate emissions reductions that wouldn’t have happened otherwise’ (SPC/GIZ Citation2013: 14).

The project design documents describe the CSRPP as an ‘incubator of ideas and testing ground for monitoring and revenue distribution methods’ (SPC/GIZ Citation2013: 8). The ‘lessons learned from projects’ are intended to accelerate the ‘development of various national REDD components’, ‘along with helping to inform policy enactment and reform’ (SPC/GIZ Citation2013: 8). Piloting has involved various tests of land stratification (SPC/GIZ Citation2014) to calculate greenhouse gas emissions, including the trialling of procedures for maintaining and measuring carbon plots. While project verification was meant to begin in 2017, work on the CSRPP stalled due to lack of funding and staff resources. By 2022, the project had not reached the implementation stage and people in Suau remained confused about how it would operate and its potential impacts on their lives and land in the future.

We situate the CSRPP within the frontier context of colonisation and missionisation in Suau, which began in the early twentieth century (Armstrong Citation1922; Williams Citation1933). The colonial encounter in Suau was focused on the extraction of resources and labour; authorities introduced waged labour on rubber plantations and relocated villages to enable easier administration (Demian Citation2004; Citation2007). Missionisation involved processes of cultural alienation (Kaniku Citation1977) where the Church banned customary practices like mortuary feasts, traditional dancing, singing and drumming (Armstrong Citation1922; Williams Citation1933). Although the missionaries adopted the language from Suau Island itself, at least six mutually-intelligible Suau dialects (Cooper Citation1975) are spoken alongside English. As social and economic obligations shifted toward the Church, people in Suau moved away from traditional networks of reciprocity. For example, most clans no longer participate in the Kula Ring, a ceremonial gifting and exchange system in the Massim region (Demian Citation2006). People continue to rely on subsistence agriculture and fishing along the coast and uphold the matrilineal land tenure system, although missionisation and colonisation have influenced the gendered division of labour and the traditional authority of women to make decisions over land. While oil palm plantations and logging concessions in Eastern and Western Suau have brought promises of development, people often travel by sea due to limited road infrastructure. Central Suau remains geographically isolated from other parts of PNG. Similar to PNG, REDD+ projects in Indonesia unfold within local villages and continuing frontier processes nearby to extractive industries .

Piloting REDD+ in Indonesia

Indonesia is a pilot country for REDD+ and has received significant international attention due to high greenhouse gas emissions from deforestation. Commercial logging under Suharto’s New Order regime accelerated after decentralisation in 1999 with the expansion of oil palm and mining concessions (Brookfield & Byron Citation1990; Resosudarmo Citation2004; Resosudarmo et al. Citation2014). REDD+ activities have concentrated on the ‘frontier’ islands of Kalimantan, Sumatra, and Papua, where carbon-rich tropical peatlands provide mitigation opportunities (Page et al. Citation2011).

In the lead up to COP13 in 2007, the Indonesian Forest-Climate Alliance (IFCA) initiated national policy processes for REDD+ . Similar to PNG, Indonesia has received funding under the UN-REDD Program and World Bank FCPF as well as development agencies and bilateral agreements. In 2010, Central Kalimantan was selected as the official REDD+ Pilot Province based on the Norwegian funding (Gallemore et al. Citation2014; Irawan et al. Citation2019; Sanders et al. Citation2017). A national REDD+ strategy was released in 2012, and a national REDD+ institution was established in 2013 but disbanded within two years (Korhonen-Kurki et al. Citation2017). Vast areas of land and forest are claimed by the state and occupied by corporations with limited recognition of customary land claims, and REDD+ progress within decentralised forest and land allocation policies has been slower than anticipated (Brockhaus et al. Citation2012; Korhonen-Kurki et al. Citation2017; Luttrell et al. Citation2014).

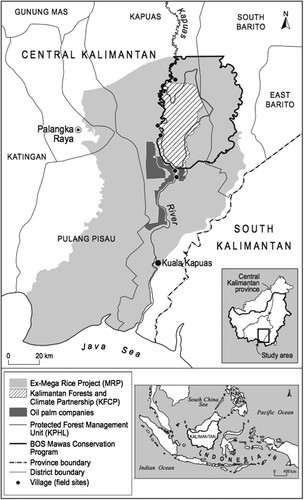

Central Kalimantan is one of five provinces in the former Dutch controlled part of Indonesian Borneo and sparsely inhabited compared to Java. In the southern peatlands, the Kalimantan Forests and Climate Partnership (KFCP) was first announced in 2007. The project encompassed 120,000 hectares of intact forest and degraded peatlands with an estimated population of 10,000 people living in village settlements along the Kapuas River. Following large-scale clearance and drainage canals in a previous failed state attempt to establish industrial rice production in the 1990s, illegal logging and oil palm expansion have exacerbated the severe peatland fires and land conflicts among the overlapping attempts of forest conservation and restoration of degraded peatlands (McCarthy Citation2013; Sanders et al. Citation2019). This is a difficult and contested location for an ambitious and experimental project like the KFCP.

Under a bilateral agreement, the Australian Government invested approximately AUD 40 million (Sanders et al. Citation2020). According to the project design documents, the KFCP was ‘intended to be a learning activity in which technical, scientific, and institutional innovations are tested, refined, and communicated to add to the body of REDD+ knowledge and experience’ (Indonesia Australia Partnership Citation2009: 2). The project involved ‘testing equitable and practicable payment mechanisms to channel financial payments’ into villages, building ‘institutional and technical readiness’ to implement REDD+, and testing, scaling up, and replicating greenhouse gas monitoring systems (Indonesia Australia Partnership Citation2009). The initial village consultations took longer than expected (Miles Citation2021; Mulyani & Jepson Citation2015). Criticisms of the KFCP in both Indonesia and Australia prompted an independent review (Barber et al. Citation2011). The Australian Government withdrew its support, and the KFCP ended in 2014. The following year, severe fires devastated the region while releasing millions of tonnes of greenhouse gasses and blanketing Southeast Asia (Astuti Citation2020).

Similar to the CSRPP, the KFCP is situated within the frontier context of trade, resettlement and colonisation (van Klinken Citation2006). The main ethnic group is Dayak Ngaju, but other Dayak groups are locally identified (Riwut Citation2007: 83). Banjarnese and other groups settled in Kapuas for trade in the early twentieth century, followed by landless Javanese and farmers from other parts of Indonesia through transmigration schemes. Dayak people engaged in pre- and colonial-era trade, but maintained relative independence from Dutch colonial rule due to mobility along rivers (Klokke & Mahin Citation2012; Kurniawan Citation2016; Riwut Citation2007). Dayak languages are spoken in local dialects as well as Indonesian language, while customary leadership is maintained alongside of state and village administrative structures. Many people have converted to Islam or Christianity. Religious practices are maintained alongside of formal religion and locally described as ‘Gama Helu’ or ‘Gama Ngaju’, whereas the term ‘Kaharingan’ is unified as a religion also referred to as Hindu Kaharingan (Schiller Citation1996). Subsistence agriculture continues to be a source of livelihoods, but traditional swidden has declined. The burning practices to open up land were adapted to peat ecologies that have been altered throughout successive interventions (Galudra et al. Citation2011; Goldstein et al. Citation2020; McCarthy Citation2013). This history within local villages is important to understand the frontier processes and ontological politics in which REDD+ is entangled .

Ontological Politics, Ethics, and More-than-Human Entanglements

Ontological politics is visible at the points where different goals and assumptions are challenged through encounters and disputes over REDD+ that entangle land, livelihoods, people, non-human beings, sorcery, and carbon among other entities. Mol’s (Citation1999; Citation2002; Citation2010) work on ontological politics underscores that if reality is multiple and performed, then struggles over the prevailing conditions of possibility are political. Ontological politics occurs when different assumptions about reality intersect and compete for primacy (Blaser Citation2010; see also Blaser Citation2013a; Citation2013b). Mol (Citation1999: 79) grapples with ethical questions: Where are the options? What is at stake? Are there really options? How should we choose? Building on Mol’s questioning, Blaser (Citation2014) asks: what is at stake in binary categorisations such as human/non-human, animate/inanimate, and nature/culture? In these questions, ethical dilemmas can arise when such binary categorisations are foregrounded over other ways of being and acting (Blaser Citation2009) and thereby close down other options. We see this, for example, in the REDD+ project design documents that enable and legitimise certain modes of intervention that intersect with local lives.

We situate our focus on ethics and ontological politics within recent work on multispecies justice and posthuman ethics of more-than-human relations (Bocci Citation2017; Celermajer et al. Citation2020; Scaramelli Citation2019). Extensive ethnographic research in Oceania and Southeast Asia (Chao Citation2018; Citation2022; Minnegal & Dwyer Citation2017; Tsing Citation2005; West Citation2006) disrupts and expands human-centred moral claims. Indigenous scholars have long questioned the imposition of universalising categories and conceptions of human agency (Todd Citation2016; Watts Citation2013). We engage with the work of Oceanic scholars like Hau’ofa (Citation1994), Māhina (Citation1992) and Nabobo-Baba (Citation2008) who have complicated the boundaries imposed and reproduced in colonial framings of the ‘Pacific’, land, sea, and people. This work not only challenges colonial legacies, but also highlights the ethical dilemmas and historical injustices imbued in these manoeuvres (Davis & Todd Citation2017).

The term ‘more-than-human’ draws attention to the ways that people navigate interventions that pre-define the boundaries separating nature and culture (Braun Citation2008; Howe Citation2019; Stensrud Citation2016), as well as the boundaries around land (Jacka Citation2015; Weiner Citation2013). As Minnegal and Dwyer (Citation2017: 252) explain through their ethnography with Kubo and Febi people in PNG, boundaries and relations are co-existing potentialities, but in certain situations people may choose to foreground either boundaries or relations. These lines of questioning have been extensively developed in anthropological engagement with ontological difference (Blaser Citation2014; Holbraad & Pedersen Citation2017; Todd Citation2016), but are not developed in ethnographic research on REDD+ . Following Gesing (Citation2021: 1), we apply a more-than-human approach to look at the ontological politics of ‘piloting’ REDD+ . In this approach, the terms ‘human’ and ‘non-human’ become adjectives, highlighting processes of categorisation, rather than ‘people’ and ‘things’.

We specifically engage with more-than-human approaches to draw attention to the categorising of human/non-human (and similarly culture/nature) in ways that are not limited to a focus on human actors and include spirits, ancestors, forests, rocks, carbon, and other more-than-human entities. A more-than-human approach, we argue, encourages us to remain open to different ways of being and acting, and to call into question rigidly imposed distinctions, universalising categories, and boundaries that enable and legitimise certain types of intervention and forms of environmental governance (Pascoe et al. Citation2021; Stensrud Citation2016; Whatmore Citation2013; Whitaker Citation2020).

Weaving Partial Stories as a Methodology

We propose a methodological technique of ‘weaving partial stories’ to organise our ethnographic thinking and leave room for other interpretations (Yates Doerr Citation2019). Our emphasis on partiality, partial stories, and weaving, and not answering/resolving these questions tries to open up thinking, reflecting, and attending to ethical dilemmas and the ontological politics of ‘piloting’ REDD+ .

Our partial and retrospective stories (Winthereik & Verran Citation2012) emerged from collaboratively discussing and reflecting on our fieldnotes, observations, and interview transcripts from fieldwork in PNG and Indonesia. By weaving together small ‘vignettes’ or ‘fragments’ of interviews, we engage with ‘storytelling’Footnote1 as an Indigenous methodology and form of knowledge transmission to guide relationships, accountability, and responsibility (Backhaus et al. Citation2020). Just as Haraway (Citation2016: 14) explored how Navajo string games are a form of ‘continuous weaving’ and practice of storytelling – a making practice as well as an ontological performance – we pay attention to how stories weave different assumptions of reality. This fits with Strathern’s (Citation1988; Citation2004) work on partial connections and ontological multiplicity based on her ethnography in PNG. Strathern’s method of comparison across difference provides a way to actively engage with Melanesian and other ontological assumptions on their own terms. Further, it is within the weaving of stories from our reflections that the salience of categories and relations becomes visible (Minnegal & Dwyer Citation2017).

This ‘weaving’ technique is different from ‘comparing’ between two cases insofar as we leave the stories incomplete. A possible disadvantage of this technique is that it limits our description of each project context. Across the REDD+ literature, there is a tendency to draw conclusions about why projects fail. To examine ontological politics and foreground ethical dilemmas that are not prominent in this existing literature, we weave ethnographic fragments as ‘partial stories’ from our fieldwork. In emphasising partiality, we do not attempt to draw conclusions and recognise the limitations of ethnographic understandings and our positionality as outsiders to the communities where we undertook fieldwork between 2013 and 2019.Footnote2

Ethical Relations and More-than-human Entanglements in Suau and Kapuas

Sitting together, a group of Dayak farmers in Indonesia explained the settlement of their village along the Kapuas River – they are the descendants of three families who travelled more than ten days upriver on a jukung (wooden canoe) to find land suitable for swidden and establishing gardens. They described their ancestors travelling inland to escape the constraints of Dutch colonial rule in Kuala Kapuas, today a district capital surrounded by oil palm plantations. In another story, they described the happy sound of the selehei bird that co-shapes relations among soil, food, plants, animals, and spirits:

If peteng mayat bird is there, we don’t use the land. Otherwise, it will be bad luck for us. We may face death. If pantis bird is in the land, our land won’t get burned because the rains will come, but that bird is a sign that our swidden will fail to have a satisfactory harvest. Selehei is black and red on the neck, it makes sound like laughing – cuit cuit cuit. This is the good bird. It has long tail looks like an arrow. This bird brings luck. If this bird is present in an area where we do fishing and swidden, we will get so much fish and harvest a lot of rice. You will feel happy to have selehei, and they always bring a happy sound. (April 2015)

Kolobi too used to cry, that bird’s name is kolobi. They cry and give us time. We don’t have time before; these things give us time… Some, they hear from the birds, you know. Birds give them signs, like debole saima [high tide] or margoon itiwah [low tide]. That bird [the ooh’ooh bird], when it cries, they know that it is asking for death. Somebody is very sick, and they are going to die very soon. He or she will die very soon. (September 2017)

In Suau, people retell and reproduce origin stories that emphasise the importance of following custom and negotiating relations between people and the environment. For example, an origin story of Tauhou describes a half-human, half-pig who travelled along the Suau coast and established the pig trading system that connects people and places. A local leader and businessman from Fife Bay, Arna, described the story of Tauhou in this way:

We look at Tauhou number one as an animal, as a pig; number two as a person or a spirit, a big spirit and it empowers into groups of people and becomes realities. So they all speak the same language and they call themselves as part of this because the spirit of Tauhou is passed onto different people in the way they receive and see Tauhou in the environment they belong to. (October 2017)

Custom also plays a role in establishing and stabilising these boundaries in Kapuas. In a village several hours boat ride from the district capital, an elderly man and Mantir (customary leader) described the importance asking permission from the spirits that live in the land:

In the past, we always conducted a small ceremony whenever we entered the forest. We offered some food, eggs, chicken, and so on, to the forest guardian. The purpose of that was to ask permission and to let the spirit in the forest know our activities. For example, when we went to the forest for harvesting latex or timber, we conducted a small ceremony beforehand. Also, if we wanted to conduct swidden agriculture, we had to do a ceremony first, as our ritual, to ask for permission of the inhabitants of the area. There is a spirit who lives in the land, and we have to ask for permission for conducting activity in the area. When we conducted ceremonies, the spirits would give a sign if they permitted us [to conduct swidden] or not. Usually, the sign is given in the rice that we use for the ceremony. We communicate with the spirit as well. If the spirit doesn’t allow us and we insist to conduct the activity in the area, we are highly likely to get problems, either the swidden will fail, or we will get sick, or other types of problems. Sometimes, the spirit can come to our dream when we’re sleeping. They can talk to the person and let the person know the condition, such as types of offering that he/she needs to fulfil. If the spirit doesn’t allow us to do activity in the area, they will explain the reason in your dreams. It took us seven days to prepare for the swidden, and after seven days, the spirit will communicate to us. (March 2015)

When sharing and discussing these partial stories, we here reflected on how the Mantir’s description of dreaming extended to spirits, trees, birds, and other non-humans (such as rice in the ceremony). The disruption to knowledge and ethical relations was closely entwined within resource extraction, labour, and economic relations. The village where the Mantir lives was one of the worst impacted by the failed attempt to establish industrial rice production in the 1990s and subsequent fires. Swidden is seldom practised. Young people periodically leave in search of plantation and mining work as well as educational opportunities. Describing the multiplication of land documents within oil palm negotiations, the Mantir explained that these documents were created from their former swidden area. He added:

Well, the practice in the past was different from today. We established swidden together with our friends. So, they could witness the land was ours. Today, you have to have the land document of ‘hitam di atas putih’ [‘black ink on a white page’ referring to a written agreement] to show that the land is yours. Today’s generation no longer remembers or practises the tradition of our ancestors. (March 2015)

Before they have like leaders who… believe on custom. And they use those powers to control… the nature… Today, we are careless, we are just like living, not following the custom beliefs and all that – that also destroys the environment… Those were beliefs which people respect the environment and what is in it, like to keep it like intact or something. (June 2017)

Our position is in-between; we are confused. We are afraid if there is no one giving us recommendation what to do – what steps that we need to take – because of the confusion we could take a step that might lead to damage in the future for us. (March 2014)

In both Kapuas and Suau, people foregrounded negotiating relations as central to establishing and stabilising boundaries. These relations – the happy sound of the selehei bird in Kapuas and the warning cry of the kolobi in Suau – did not predefine the separation of land and forest from human sentience and agency. Weaving these partial stories, we observed that local sense of time and temporality were being disrupted by the speed of the changes. Birds no longer guide swidden cultivation in Kapuas, and the kolobi bird struggles to tell the time through the changing climate and tides in Suau. These bird stories are ethnographic fragments from our fieldwork: as outsiders, we were able to glimpse in these fragments the complexities of how people manoeuvre within frontier processes as well as the breakdown of chains of belonging.

Ontological Politics of Experimental Environmental Governance

Our entry point for examining the ontological politics of ‘piloting’ REDD+ came from our attempts to weave together stories about converging assumptions, including a story about tree ‘rubbish’ and sorcery. In Suau, after gaining consent over several days of community consultation, a REDD+ project team comprising international and national scientists and practitioners went to the forest to establish a test plot for the CSRPP. The team took samples of biomass to measure the carbon stored in the trees. A staff member at a government agency explained:

I was summoned by the landowners to walk ten kilometres to explain to them why we are doing that kind of activities. Because we are collecting the biomass, leaves and all those kind of things. That we did not explain to them… I had to go back, because in their custom, collecting rubbish is very offensive to them. If you collect somebody’s rubbish that means you are going to do something bad to them. (February 2017)

In Kapuas, those who participated in the KFCP’s reforestation trials were given the choice to select from local (endemic) tree species to trial approaches to peatland restoration. The seedlings were collected from intact forest in the northern section of the project site to be grown in village nurseries. The proximity of one of the trial sites to Donald’s attempted oil palm smallholding sparked fears that the reforestation might impose rules, restrict livelihood options, and exacerbate social breakdowns. It contributed to threats being made against project staff, a village hall being destroyed, and the KFCP’s withdrawal from this village.

Field staff explained that the dispute was about a small faction – a ‘tyranny of the minority over the majority’. In their explanation, the project’s withdrawal from Donald’s village was due to the competing environmental and economic rationalities. Donald offered a layered explanation. The dispute was partly about inadequate compensation from the project. It was partly about frustration over state claims to customary land. It was also about broken trust and disappointment over successive interventions. Accumulated feelings of anger and frustration contributed to the cessation of project activities in Donald’s village. In neighbouring villages, many of those who participated in the reforestation trials appreciated the income; particularly, women were able to grow the seedlings close to home whilst caring for children. But many struggled to understand why they were planting the seedlings:

We did the reforestation, but I couldn’t understand the logic. When we did the reforestation, we had to cut down all the trees in that area. Meanwhile, we could not tell whether the seedlings that we planted in that area will grow. I couldn’t understand it… if we want to protect the environment, why did we have to cut down the trees that grew big over there? And also, why we were never asked to take care of the trees that already grew, instead of planting the seedlings when we didn’t know whether the trees could grow there or not? (October 2013)

Returning to Suau, another proposed conservation plot for the CSRPP was disputed by local landowners because of attempts to draw boundaries around land and trees. Gabu, a youth leader who accompanied the project team and witnessed the dispute, described:

We got the knife, we cut the marks of the trees, the sign of X. And then they were trying to what, make the GPS… how many kilometres down here and right about there and the square one, they were trying to mark the square block… So when they got the GPS around like this, there are some boundaries, I mean the [land] owners are not really sure… They got angry… They know their land and that is where they dispute. (March 2017)

Other fears and disputes were expressed within complicated and evolving relationships of ‘commodities’ – palm oil and carbon among other entities – to local lives and livelihoods. In Kapaus, Sarifan, an elderly Javanese man had originally joined the village through marriage to a local Dayak Kaharingan woman and embraced Dayak lifeways and customary practices throughout his life. Sitting with his wife, Sarifan described oil palm investors travelling to this village to enlist local supporters:

To some degree, [those interested in oil palm] are right, we cannot eat peatland. I remember when the KFCP came to this village, the oil palm investors also came to this village at the same time. The guy from hydrology from KFCP was also invited to the oil palm company’s meeting. The former Head of Village criticised what the KFCP guy said in that meeting, saying, ‘I’ve been trying hard to find investor for oil palm plantations to be meeting established in this village, but people want us to eat peatland instead’. (March 2015)

In Suau, people’s fears about producing enough food and survival were linked to concerns about outsiders stealing land and air (‘carbon’ was understood as ‘air’). As Tani, who was involved in REDD+ awareness programmes, explained: ‘Every time you say [project proponents] are coming, they [village people] say “they are coming to steal our land; they are coming to give our land away”. Or, “they are coming and tricking us, bullshitting us”’. (June 2017). Gabu, who participated in some of the project meetings in the village, discussed these fears:

People were thinking that… these people might come here and they’ll like steal the land or something like that… Like maybe some of them think like the project was based on the carbon, that’s why people were a bit confused. They might get all the land, all the air, the oxygen of our whole logs or our whole area, area from here to Suau or from here down towards [Western Suau]. They were confusing this. They might come and get our good oxygen and they’ll go and market it overseas or in the European countries. (March 2017)

Ethical Distance in Piloting REDD+

While ethnographic research on REDD+ has shown how globally-oriented design features can downplay the potential impacts on the lives of local people (Milne et al. Citation2019), little attention has been placed on the ethics and ontological politics of ‘piloting’ REDD+ . We propose the concept of ethical distance to understand the gaps or spaces between the converging assumptions and world-making practices in pilot and demonstration sites. Following Stensrud (Citation2016), we understand that governance experimentation in REDD+ brings together differently performed realities that are continuously in the making, always emerging and precariously entangled with each other. In both the KFCP in Indonesia and the CSRPP in PNG, we observed that ‘piloting’ REDD+ implied a sequential movement: first, knowledge and ideas circulate downward from the global scale to ‘test’ methodologies, ‘trial’ instruments, and ‘pilot’ projects; and second, the ‘lessons’ circulate upward from the local scale to guide future policies and projects. This sequential movement increased the ethical distance between the worlds entangled in REDD+ experiments.

The global architecture, funding instruments, technologies, and so on, emerging from international climate negotiations, were geographically, culturally, linguistically, and ethically distant from negotiated relations (more-than-human entanglements) among people, birds, and other beings in Suau and Kapuas. Different goals and assumptions of donors, scientists, conservationists, among many others, to initiate REDD+ activities came into friction with differently performed realities. For example, the inscription of ‘peatland’ as ‘carbon’ in the KFCP meant that the commodity (carbon) could be measured, stored, sold, and profited from, but it remained ‘immeasurable and invisible by local means’ (Miles Citation2021: 15). Here, ethical distance refers both to the way these pilot projects tie together entities that are geographically, historically, and culturally removed from each other, and to the distant ‘centres’ of decision-making separating the donors, experts, and many others, from the pilot and demonstration sites. This ‘distance’, in which REDD+ experiments are ‘far away’ from those allocating funding and bringing their expertise, encircles the spatial imaginaries of resource frontiers that were relationally distant from their colonial centres (Blomley Citation2003; Prout & Howitt Citation2009; McCarthy Citation2013).

Ethical distance helps to describe the ways in which categories of land, carbon, and people were foregrounded as fixed and static in each project. Drawing on Minnegal and Dwyer’s (Citation2017: 252) description of boundaries and relations from PNG, the methodologies and technologies being tested inscribed fixed boundaries between the human and non-human with respect to land and land use (see also Jacka Citation2015; Weiner Citation2013). When certain categories of ‘land’ or ‘forest’ are foregrounded at the expense of others, this can work to deny people the ability to negotiate relations in ways that stabilise boundaries. Thus, in stories about marking trees and the dispute caused by collecting ‘tree rubbish’ in Suau, people contested the imposition of boundaries through the methodologies and technologies being tested. In this dispute, we distinguish between boundaries that were assumed to be a priori such as related to carbon measurement, and those that emerged through continually negotiated relations, where the distinction between human and non-human sentience and agency is not pre-defined (Māhina Citation1992; Todd Citation2016; Watts Citation2013).

Reflecting on debates over radical alterity and emphasising the pragmatic and affective dimensions of ontological politics (Vigh & Sausdal Citation2014), we do not posit ‘local’ or ‘Indigenous’ as radically other than ‘Western’ or ‘global’ objectives and assumptions in these REDD+ projects. In other words, we do not artificially set up a binary between ‘local’ and ‘ethical’ environmental relations in relation to ‘externally imposed’ and ‘immoral’ projects (see also Scaramelli Citation2019). Instead, the concept of ethical distance helps to foreground how ethics may take different forms and imply different degrees of responsibility and care. This is not to say that distant ethical relations are inherently bad, or that ethical proximity is inherently good. Rather, we argue that careful attention to the disparities of climate change and environmental governance experiments is essential for understanding ethics as relational and situated in histories of colonisation and frontier resource extraction.

Conclusion

The ideas of experimentation and learning that we have explored with a focus on REDD+ are reflected in global environmental governance more broadly (Armeni Citation2015; Overdevest and Zeitlin Citation2014). These ideas extend to other areas from cities and urban climate experimentation (Kern Citation2019; Liu & Lo Citation2021) and climate adaptation strategies (Rocle et al. Citation2021; Warner et al. Citation2018) to calls for a transition from incremental to transformational adaptation in forest-related climate actions (Djoudi et al. Citation2022). A proliferation of frameworks and policy models can risk reinscribing dominant assumptions while proposing solutions that do not address the inequalities and histories that contribute to climate change (Braun Citation2015; Haraway et al. Citation2016; Tsing et al. Citation2017; West Citation2020). Indigenous scholars like Todd (Citation2016) and Watts (Citation2013) have drawn attention to how the affective, material, and embodied dimensions of ethics can help to slow down our reasoning, so that we are better able to recognise when what people say and do cannot – and should not – be assimilated into global environmental and climate objectives.

Proposing the concept of ethical distance, we have explored ethical dilemmas and ontological politics in misunderstandings and disputes in the CSRPP in PNG and the KFCP in Indonesia. From a Western ontological standpoint, it may appear strange that measuring carbon would constitute a threat. While a dispute about ‘land’ is not necessarily an ontological conflict (Blaser Citation2013a; Citation2013b), it may, in some instances, conceal struggles over the conditions of possibility, options, and alternatives. Within the REDD+ project designs, there was no way to account for biomass as a tool used in the practice of sorcery: the dominant framings of monitoring, reporting, and verification (MRV) and carbon measurement did not allow room for this possibility. For example, the dispute over a carbon measurement plot in Suau centred on the different assumptions and interpretations of ‘collecting biomass to measure carbon’ and ‘collecting rubbish to perform sorcery’. This dispute is ‘ontological’ and ‘political’ (Mol Citation1999). It is also ‘ethical’ in questions concerning what options are afforded in these projects. Slowing down our reasoning here entails questioning: What do we mean by options? Are these options that people really want? Sometimes options can lead people into uncomfortable ethical situations or entangle them in much deeper discomfort than is visible within experimental designs (Warner et al. Citation2018).

By foreclosing the possibilities of learning from and together with local and Indigenous communities, the universalising tendencies of environmental governance are enabled and legitimised (West Citation2020). This is not a new process, as Davis and Todd (Citation2017) highlight, frontier processes of extraction, destruction, and transformation have been occurring over centuries, disturbing more-than-human, situated knowledges, and ethical relations. By weaving partial stories, without resolving or tying down a narrative of events, we have sought to recognise the ethical dilemmas of how people manoeuvre within patterns of environmental governance and extractive industries. We have interwoven stories from PNG and Indonesia to draw attention to contestations over REDD+ activities where it is not just boundaries or relations that are disputed, but the very conditions of possibility that are at stake. Weaving partial stories – an acknowledgement that other stories could have been possible – opens up possibilities for generative critique (Winthereik and Verran Citation2012). Our collaborative and partial ethnographic approach to fieldwork in Suau and Kalimantan emphasises the productive possibilities of dialogue between ethics and ontological politics: Better when, how, for whom? (Yates Doerr Citation2019: 307).

Our concern with ontological politics has sought to focus attention to the material and ethical implications of attempts to govern tropical forests and climate change in ‘frontier’ regions of Indonesia and PNG. We have further sought to focus attention on the ways that reality is performed and people live, questioning:

What is at stake when someone’s land is being colonised by oil palm, while other trees are planted in orderly rows for carbon measurement? What is at stake when someone is fearful that their land and oxygen will be stolen, or that leaf litter will be used to perform malign acts of sorcery?

Acknowledgements

This article brings together three separate research projects. Each author was actively involved in the writing and conception. The second author was responsible for fieldwork in Papua New Guinea. The first, third, and fourth authors were responsible for fieldwork in Indonesia. We thank the people of Suau and Kapuas for sharing their stories and lives with us, and our research supervisors for their guidance and mentoring. We are grateful to the many people who gave their time and advice in preparation of this manuscript, in particular Monica Minnegal and Sophie Chao, and Chandra Jayasuriya and Thor Jensen for preparation of the maps. We also thank the Editor and two anonymous reviewers for their detailed and constructive advice. Results and conclusions represent the views of the authors rather than supporting organisations.

Disclosure Statement

There are no relevant financial or non-financial competing interests to report.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Research in Suau, PNG explicitly engaged with local forms of storytelling known as pilipili dai, which encompass the sharing of origin stories and daily practices of engaging in reciprocal relations, negotiation, and contestation (Pascoe et al. Citation2021).

2 The research Indonesia involved fifteen months of cumulative fieldwork in two separate research projects (Sanders et al. Citation2017; Citation2019; Citation2020). The research in PNG involved twelve months of cumulative fieldwork (Pascoe Citation2018; Pascoe et al. Citation2021). Information about field methods and ethnographic descriptions are included in these publications. We have used pseudonyms when referring to individuals.

References

- Armeni, Chiara. 2015. Global Experimentalist Governance, International Law and Climate Change Technologies. International and Comparative Law Quarterly, 64(4):875–904.

- Armstrong, W.E. 1922. Anthropology (Report No. 1) Report on the Suau-Tawala. Territory of Papua, Native Taxes Ordinance. Government Anthropologist, London.

- Asiyanbi, Adeniyi & Jens Friis Lund. 2020. Policy Persistence: REDD+ Between Stabilization and Contestation. Journal of Political Ecology, 27(1):378–400.

- Asiyanbi, Adeniyi & Kate Massarella. 2020. Transformation Is What You Expect, Models Are What You Get: REDD+ and Models in Conservation and Development. Journal of Political Ecology, 27(1):476–495.

- Astuti, Rini. 2020. Fixing Flammable Forest: The Scalar Politics of Peatland Governance and Restoration in Indonesia. Asia Pacific Viewpoint, 61(2):283–300.

- Astuti, Rini & Andrew McGregor. 2017. Indigenous Land Claims or Green Grabs? Inclusions and Exclusions Within Forest Carbon Politics in Indonesia. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 44(2):445–466.

- Babon, Andrea. 2014. Our Carbon, Their Forest: The Political Ecology of Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+) in Papua New Guinea. PhD Thesis. Australia: Charles Darwin University.

- Babon, Andrea & Gae Yansom Gowae. 2013. The Context of REDD+ in Papua New Guinea: Drivers, Agents and Institutions. Occasional Paper 89. Bogor, Indonesia: Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR).

- Backhaus, Vincent, Nalisa Neuendorf & Lokes Brooksbank. 2020. Storying Toward Pasin and Luksave: Permeable Relationships Between Papua New Guineans as Researchers and Participants. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19:1–11.

- Barber, David, John Hudson & Agus P. Sari. 2011. Indonesia-Australia Forest Carbon Partnership Independent Progress Report. Jakarta, Indonesia-Australia: Forest Carbon Partnership.

- Bingeding, Nalau. 2014. Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation of Forests in Papua New Guinea: Issues and Options. NRI Discussion Paper. Boroko, Papua New Guinea, National Research Institute.

- Blaser, Mario. 2009. The Threat of the Yrmo: The Political Ontology of a Sustainable Hunting Program. American Anthropologist, 111(1):10–20.

- Blaser, Mario. 2010. Storytelling Globalization: From the Chaco and Beyond. Durham/London: Duke University Press.

- Blaser, Mario. 2013a. Notes Towards a Political Ontology of ‘Environmental Conflicts’. In Contested Ecologies: Dialogues in the South on Nature and Knowledge, edited by Lesley Green, 13–27. Cape Town: HSRC Press.

- Blaser, Mario. 2013b. Ontological Conflicts and the Stories of Peoples in Spite of Europe. Current Anthropology, 54(5):547–568.

- Blaser, Mario. 2014. Ontology and Indigeneity: On the Political Ontology of Heterogeneous Assemblages. Cultural Geographies, 21(1):49–58.

- Blomley, Nicholas. 2003. Law, Property, and the Geography of Violence: The Frontier, the Survey, and the Grid. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 93(1):121–141.

- Bocci, Paolo. 2017. Tangles of Care: Killing Goats to Save Tortoises on the Galápagos Islands. Cultural Anthropology, 32(3):424–449.

- Bourke, Michael R. & Tracy Harwood. 2009. Food and Agriculture in Papua New Guinea. Canberra: ANU Press.

- Braun, Bruce. 2008. Theorizing the Nature-Society Divide. In The SAGE Handbook of Political Geography, edited by Kevin Cox, Murray Low and Jennifer Robinson, 189–204. London: SAGE Publications.

- Braun, Bruce. 2015. From Critique to Experiment? In The Routledge Handbook of Political Ecology, edited by Tom Perreault, Gavin Bridge and James McCarthy, 102–114. London: Routledge.

- Brockhaus, Maria, Krystof Obidzinski, Ahmad Dermawan, Yves Laumonier & Cecilia Luttrell. 2012. An Overview of Forest and Land Allocation Policies in Indonesia: Is the Current Framework Sufficient to Meet the Needs of REDD+? Forest Policy and Economics, 18:30–37.

- Brookfield, Harold & Yvonne Byron. 1990. Deforestation and Timber Extraction in Borneo and the Malay Peninsula. Global Environmental Change, 1(1):42–56.

- Bull, G. Q., A. K. Boedhihartono, G. Bueno, B. Cashore, C. Elliott, J. D. Langston, R. A. Riggs & J. Sayer. 2018. Global Forest Discourses Must Connect with Local Forest Realities. International Forestry Review, 20(2):160–166.

- Cadman, Timothy, Tek Maraseni, Hugh Breakey, Federico López-Casero & Hwan Ma. 2016. Governance Values in the Climate Change Regime: Stakeholder Perceptions of REDD+ Legitimacy at the National Level. Forests, 7(12):212.

- Carrier, James G. & Paige West. 2009. Virtualism and the Logic of Environmentalism. In Virtualism, Governance and Practice: Vision and Execution in Environmental Conservation, edited by James G. Carrier and Paige West, 1–23. New York/Oxford: Berghahn Books.

- Celermajer, Danielle, David Schlosberg, Lauren Rickards, Makere Stewart-Harawira, Mathias Thaler, Petra Tschakert, Blanche Verlie & Christine Winter. 2020. Multispecies Justice: Theories, Challenges, and a Research Agenda for Environmental Politics. Environmental Politics, 30(1-2):1–22.

- Chao, Sophie. 2018. In the Shadow of the Palm: Dispersed Ontologies among Marind, West Papua. Cultural Anthropology, 33(4):621–649.

- Chao, Sophie. 2022. In the Shadow of the Palms: More-Than-Human Becomings in West Papua. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Cooper, R. E. 1975. Coastal Suau: A Preliminary Study of Internal Relationships. In In Studies in Languages of Central and South-East Papua, edited by T.E. Dutton, 227–278. Canberra: Australian National University.

- Corbera, Esteve, Manuel Estrada & Katrina Brown. 2010. Reducing Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation in Developing Countries: Revisiting the Assumptions. Climatic Change, 100:355–388.

- Davis, Heather & Zoe Todd. 2017. On the Importance of a Date, or Decolonizing the Anthropocene. ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies, 16(4):761–780.

- Demian, Melissa. 2004. Seeing, Knowing, Owning: Property Claims as Revelatory Acts. In Transactions and Creations: Property Debates and the Stimulus of Melanesia, edited by E. Hirsch and M. Strathern, 60–82. New York/Oxford: Berghahn Books.

- Demian, Melissa. 2006. ‘Emptiness’ and Complementarity in Suau Reproductive Strategies. In In Population, Reproduction and Fertility in Melanesia, edited by S.J. Ulijaszek, 136–158. New York/Oxford: Berghahn Books.

- Demian, Melissa. 2007. ‘Land Doesn’t Come from Your Mother: She Didn’t Make It with her Hands’: Challenging Matriliny in Papua New Guinea.”. In Feminist Perspectives on Land Law, edited by H. Lim and A. Bottomley, 155–170. New York: Routledge-Cavendish.

- Di Giminiani, Piergiorgio & Sophie Haines. 2020. Introduction: Translating Environments. Ethnos, 85(1):1–16.

- Djoudi, Houria, Kate Dooley, Amy E. Duchelle, Antoine Libert-Amico, Bruno Locatelli, Michael Bessike Balinga, Maria Brockhaus, et al. 2022. Leveraging the Power of Forests and Trees for Transformational Adaptation. SSRN Electronic Journal, 1–26.

- Eilenberg, Michael. 2015. Shades of Green and REDD: Local and Global Contestations Over the Value of Forest Versus Plantation Development on the Indonesian Forest Frontier. Asia Pacific Viewpoint, 56(1):48–61.

- Filer, Colin. 2015. How April Salumei Became the REDD Queen. In Tropical Forests of Oceania: Anthropological Perspectives, edited by Joshua A. Bell, Paige West and Colin Filer, 179–210. Canberra: ANU Press.

- Filer, Colin, Navroz K. Dubash & Kilyati Kalit. 2000. The Thin Green Line: World Bank Leverage and Forest Policy Reform in Papua New Guinea. NRI Monograph 37. Boroko, Papua New Guinea: Australian National University.

- Fry, Ian. 2008. Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation: Opportunities and Pitfalls in Developing a New Legal Regime. Review of European Community & International Environmental Law, 17(2):166–182.

- Gallemore, Caleb T., H. Rut Dini Prasti & Moira Moeliono. 2014. Discursive Barriers and Cross-Scale Forest Governance in Central Kalimantan, Indonesia. Ecology and Society, 19(2):18. http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol19/iss2/art18/

- Galudra, G., M. Van Noordwijk, S. Suyanto, I. Sardi, U. Pradhan & D. Catacutan. 2011. Hot Spots of Confusion: Contested Policies and Competing Carbon Claims in the Peatlands of Central Kalimantan, Indonesia. International Forestry Review, 13(4):431–441.

- Gesing, Friederike. 2021. Towards a More-Than-Human Political Ecology of Coastal Protection: Coast Care Practices in Aotearoa New Zealand. Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space, 4(2):208–229.

- Goldstein, Jenny E., Laura Graham, Sofyan Ansori, Yenni Vetrita, Andri Thomas, Grahame Applegate, Andrew P. Vayda, Bambang H. Saharjo & Mark A. Cochrane. 2020. Beyond Slash-and-Burn: The Roles of Human Activities, Altered Hydrology and Fuels in Peat Fires in Central Kalimantan, Indonesia. Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography, 41(2):190–208.

- Haraway, Donna, Noboru Ishikawa, Scott F. Gilbert, Kenneth Olwig, Anna L. Tsing & Nils Bubandt. 2016. Anthropologists Are Talking – About the Anthropocene. Ethnos, 81(3):535–564.

- Hau’ofa, Epeli. 1994. Our Sea of Islands. The Contemporary Pacific, 6(1):148–161.

- Holbraad, Martin & Morten Axel Pedersen. 2017. The Ontological Turn: An Anthropological Exposition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Howe, Cymene. 2019. Greater Goods: Ethics, Energy, and Other-Than-Human Speech. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 25(S1):160–176.

- Howes, Stephen. 2009. Cheap but Not Easy: The Reduction of Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation in Papua New Guinea. Pacific Economic Bulletin, 24(1):130–143.

- Humphreys, D. 2008. The Politics of Avoided Deforestation: Historical Context and Contemporary Issues. International Forestry Review, 10(3):433–442.

- Indonesia Australia Partnership. 2009. Kalimantan Forest and Climate Partnership (KFCP) Design Document. Jakarta, Indonesia-Australia: Forest Carbon Partnership.

- Irawan, Silvia, Triyoga Widiastomo, Luca Tacconi, John D. Watts & Bernadinus Steni. 2019. Exploring the Design of Jurisdictional REDD+: The Case of Central Kalimantan, Indonesia. Forest Policy and Economics, 108:101853.

- Jacka, Jeremy. 2015. Alchemy in the Rain Forest: Politics, Ecology, and Resilience in a New Guinea Mining Area. New Ecologies for the Twenty-First Century. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Jagger, Pamela, Stibniati Atmadja, Subhrendu K. Pattanayak, Erin Sills & William D. Sunderlin. 2009. Learning While Doing: Evaluating Impacts of REDD+ Projects. In Realising REDD+: National Strategy and Policy Options, edited by Arild Angelsen, 281–292. Bogor, Indonesia: Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR).

- Kaniku, Anne. 1977. Religious Confusion. Yagl-Ambu, 4(4):264–283.

- Kern, Kristine. 2019. Cities as Leaders in EU Multilevel Climate Governance: Embedded Upscaling of Local Experiments in Europe. Environmental Politics, 28(1):125–145.

- Klokke, Arnoud H. & Marko Mahin. 2012. Along the Rivers of Central Kalimantan: Customary Heritage of the Ngaju and Ot Danum Dayak. Leiden: Museum Volkenkunde, National Museum of Ethnology.

- Korhonen-Kurki, Kaisa, Maria Brockhaus, Efrian Muharrom, Sirkku Juhola, Moira Moeliono, Cynthia Maharani & Bimo Dwisatrio. 2017. Analyzing REDD+ as an Experiment of Transformative Climate Governance: Insights from Indonesia. Environmental Science & Policy, 73:61–70.

- Kurniawan, Nanang Indra. 2016. Local Struggle, Recognition of Dayak Customary Land, and State Making in Central Kalimantan, Indonesia. Unpublished PhD Thesis. University of Melbourne, Australia.

- Laurance, William F., Titus Kakul, Memory Tom, Reza Wahya & Susan G. Laurance. 2012. Defeating the ‘Resource Curse’: Key Priorities for Conserving Papua New Guinea’s Native Forests. Biological Conservation, 151(1):35–40.

- La Viña, Antonio G.M., Alaya de Leon & Reginald Rex Barrer. 2016. History and Future of REDD+ in the UNFCCC: Issues and Challenges. In Research Handbook on REDD+ and International Law, edited by Christina Voigt, 11–29. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Li, Tania Murray. 2007. Practices of Assemblage and Community Forest Management. Economy and Society, 36(2):263–293.

- Liu, Minsi & Kevin Lo. 2021. Governing Eco-Cities in China: Urban Climate Experimentation, International Cooperation, and Multilevel Governance. Geoforum, 121:12–22.

- Lounela, Anu Kristiina. 2019. Erasing Memories and Commodifying Futures Within the Central Kalimantan Landscape. Dwelling in Political Landscapes: Contemporary Anthropological Perspectives (Studia Fennica Anthropologica, 4:53–73.

- Luttrell, Cecilia, Ida Aju Pradnja Resosudarmo, Efrian Muharrom, Maria Brockhaus & Frances Seymour. 2014. The Political Context of REDD+ in Indonesia: Constituencies for Change. Environmental Science & Policy, 35:67–75.

- Lyster, Rosemary. 2009. The New Frontier of Climate Law: Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation. Environmental and Planning Law Journal, 26(6):417–456.

- Māhina, Ōkusitino. 1992. The Tongan Traditional History Tala-Ē-Fonua: A Vernacular Ecology-Centred Historico-Cultural Concept. Canberra: Australian National University.

- Massarella, Kate, Susannah M. Sallu, Jonathan E. Ensor & Rob Marchant. 2018. REDD+, Hype, Hope and Disappointment: The Dynamics of Expectations in Conservation and Development Pilot Projects. World Development, 109:375–385.

- McCarthy, John F. 2013. Tenure and Transformation in Central Kalimantan After the Million Hectare Project. In Land for the People: The State and Agrarian Conflict in Indonesia, edited by Anton Lucas and Carol Warren, 183–214. Southeast Asia Series 126. Athens: Ohio University Press.

- Miles, Wendy B. 2021. The Invisible Commodity: Local Experiences with Forest Carbon Offsetting in Indonesia. Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space, 4(2):499–524.

- Milne, Sarah, Sango Mahanty, Phuc To, Wolfram Dressler, Peter Kanowski & Maylee Thavat. 2019. Learning from 'Actually Existing' REDD+: A Synthesis of Ethnographic Findings. Conservation and Society, 17(1):84–95.

- Minnegal, Monica & Peter D. Dwyer. 2017. Navigating the Future: An Ethnography of Change in Papua New Guinea. Canberra: ANU Press.

- Mol, Annemarie. 1999. Ontological Politics. A Word and Some Questions. In In Actor Network Theory and After, edited by John Law and John Hassard, 74–89. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

- Mol, Annemarie. 2002. Cutting Surgeons, Walking Patients: Some Complexities Involved in Comparing. In In Complexities: Social Studies of Knowledge Practices, edited by John Law and Annemarie Mol, 218–257. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Mol, Annemarie. 2010. Actor-Network Theory: Sensitive Terms and Enduring Tensions. Kölner Zeitschrift Für Soziologie Und Sozialpsychologie. Sonderheft, 50:253–269.

- Mulyani, Mari & Paul Jepson. 2015. Social Learning Through a REDD+ ‘Village Agreement’: Insights from the KFCP in Indonesia. Asia Pacific Viewpoint, 56(1):79–95.

- Myers, Rodd, Ashwin Ravikumar, Anne M. Larson, Laura F. Knowler, Anastasia Yang & Tim Trench. 2018. Messiness of Forest Governance: How Technical Approaches Suppress Politics in REDD+ and Conservation Projects. Global Environmental Change, 50:314–324.

- Nabobo-Baba, Unaisi. 2008. Decolonising Framings in Pacific Research: Indigenous Fijian Vanua Research Framework as an Organic Response. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 4(2):140–154.

- Nantongo, Mary Gorret. 2017. Legitimacy of Local REDD+ Processes. a Comparative Analysis of Pilot Projects in Brazil and Tanzania. Environmental Science & Policy, 78:81–88.

- Overdevest, Christine & Jonathan Zeitlin. 2014. Assembling an Experimentalist Regime: Transnational Governance Interactions in the Forest Sector. Regulation & Governance, 8(1):22–48.

- Page, Susan E., John O. Rieley & Christopher J. Banks. 2011. Global and Regional Importance of the Tropical Peatland Carbon Pool. Global Change Biology, 17(2):798–818.

- Pascoe, Sophie. 2018. Interrogating Scale in the REDD+ Assemblage in Papua New Guinea. Geoforum, 96:87–96.

- Pascoe, Sophie, Wolfram Dressler & Monica Minnegal. 2021. Storytelling Climate Change – Causality and Temporality in the REDD+ Regime in Papua New Guinea. Geoforum, 124:360–370.

- Pasgaard, Maya. 2015. Lost in Translation? How Project Actors Shape REDD+ Policy and Outcomes in Cambodia. Asia Pacific Viewpoint, 56(1):111–127.

- Prout, Sarah & Richard Howitt. 2009. Frontier Imaginings and Subversive Indigenous Spatialities. Journal of Rural Studies, 25(4):396–403.

- Ramcilovik-Suominen, Sabaheta & Iben Nathan. 2020. REDD+ Policy Translation and Storylines in Laos. Journal of Political Ecology, 27(1):436–455.

- Resosudarmo, Ida Aju Pradnja. 2004. Closer to People and Trees: Will Decentralisation Work for the People and the Forests of Indonesia? The European Journal of Development Research, 16(1):110–132.

- Resosudarmo, Ida Aju Pradnja, Ngakan Putu Oka, Sofi Mardiah & Nugroho Adi Utomo. 2014. Governing Fragile Economies: A Perspective on Forest and Land-Based Development in the Regions. In In Regional Dynamics in a Decentralized Indonesia, edited by Hal Hill, 260–284. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

- Riwut, Tjilik. 2007. Kalimantan Membangun Alam Dan Kebudayaan. Yogjakarta, Indonesia: NR Publishing.

- Rocle, Nicolas, Jeanne Dachary-Bernard & Hélène Rey-Valette. 2021. Moving Towards Multi-Level Governance of Coastal Managed Retreat: Insights and Prospects from France. Ocean & Coastal Management, 213:105892.

- Sanders, Anna J.P., Rebecca M. Ford, Rodney J. Keenan & Anne M. Larson. 2020. Learning Through Practice? Learning from the REDD+ Demonstration Project, Kalimantan Forests and Climate Partnership (KFCP) in Indonesia. Land Use Policy, 91:104285.

- Sanders, Anna J.P., Rebecca M. Ford, Lilis Mulyani, Rut Dini H. Prasti, Anne M. Larson, Yusurum Jagau & Rodney J. Keenan. 2019. Unrelenting Games: Multiple Negotiations and Landscape Transformations in the Tropical Peatlands of Central Kalimantan, Indonesia. World Development, 117:196–210.

- Sanders, Anna J.P., Håkon da Silva Hyldmo, H. Rut Dini Prasti, Rebecca M. Ford, Anne M. Larson & Rodney J. Keenan. 2017. Guinea Pig or Pioneer: Translating Global Environmental Objectives Through to Local Actions in Central Kalimantan, Indonesia’s REDD+ Pilot Province. Global Environmental Change, 42:68–81.

- Scaramelli, Caterina. 2019. The Delta Is Dead: Moral Ecologies of Infrastructure in Turkey. Cultural Anthropology, 34(3):388–416.

- Schiller, Anne. 1996. An "Old" Religion in "New Order" Indonesia: Notes on Ethnicity and Religious Affiliation. Sociology of Religion, 57(4):409–417.

- SPC/GIZ. 2013. REDD Feasibility Study for Central Suau, Milne Bay, Papua New Guinea. Suva, Fiji: SPC/GIZ.

- SPC/GIZ. 2014. Forest Carbon Inventory in Proposed Central Suau REDD+ Area, Milne Bay Province, Papua New Guinea. Suva, Fiji: SPC/GIZ.

- SPC/GIZ. 2015. Proposed Benefit Sharing System for REDD+ Pilot Project in Central Suau, Papua New Guinea. Suva, Fiji: SPC/GIZ.

- Stensrud, Astrid B. 2016. Climate Change, Water Practices and Relational Worlds in the Andes. Ethnos, 81(1):75–98.

- Stern, Nicholas. 2006. The Economics of Climate Change: The Stern Review. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Strathern, M. 1988. The Gender of the Gift: Problems with Women and Problems with Society in Melanesia. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Strathern, M. 2004. Partial Connections. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press.

- Tehan, Maureen F., Lee C. Godden, Margaret A. Young & Kirsty A. Gover. 2017. The Impact of Climate Change Mitigation on Indigenous and Forest Communities: International, National and Local Law Perspectives on REDD+. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Todd, Zoe. 2016. An Indigenous Feminist’s Take on the Ontological Turn: ‘ontology’ Is Just Another Word for Colonialism. Journal of Historical Sociology, 29(1):4–22.

- Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. 2005. Friction: An Ethnography of Global Connection. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Tsing, Anna, Heather Swanson, Elaine Gan & Nils Bubandt. 2017. Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- van Klinken, Gerry. 2006. Colonizing Borneo: State-Building and Ethnicity in Central Kalimantan. Indonesia, 81:23–49.

- Vigh, Henrik Erdman & David Brehm Sausdal. 2014. From Essence Back to Existence: Anthropology Beyond the Ontological Turn. Anthropological Theory, 14(1):49–73.

- Warner, Jeroen F., Anna J. Wesselink & Govert D. Geldof. 2018. The Politics of Adaptive Climate Management: Scientific Recipes and Lived Reality. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 9(3):e515.

- Watts, Vanessa. 2013. Indigenous Place-Thought & Agency Amongst Humans and Non-Humans (First Woman and Sky Woman Go on a European World Tour!). Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 2(1):20–34.

- Weiner, James F. 2013. The Incorporated What Group: Ethnographic, Economic and Ideological Perspectives on Customary Land Ownership in Contemporary Papua New Guinea. Anthropological Forum, 23(1):94–106.

- West, Paige. 2006. Conservation Is Our Government Now: The Politics of Ecology in Papua New Guinea. Durham/London: Duke University Press.

- West, Paige. 2020. Translations, Palimpsests, and Politics. Environmental Anthropology Now. Ethnos, 85(1):118–123.

- Whatmore, Sarah J. 2013. Earthly Powers and Affective Environments: An Ontological Politics of Flood Risk. Theory, Culture & Society, 30(7–8):33–50.

- Whitaker, James Andrew. 2020. Climatic and Ontological Change in the Anthropocene among the Makushi in Guyana. Ethnos, 85(5):843–860.

- Williams, F.E. 1933. Depopulation of the Suau District. Territory of Papua, Port Moresby.

- Winthereik, Brit Ross & Helen Verran. 2012. Ethnographic Stories as Generalizations That Intervene. Science & Technology Studies, 28(1):27–51.

- Yates Doerr, Emily. 2019. Whose Global, Which Health? Unsettling Collaboration with Careful Equivocation. American Anthropologist, 121(2):297–310.