ABSTRACT

From mega-projects to small-scale repairs, many construction projects in Kenya are characterised by delays and false starts. One such case is the renovation of the Kamariny stadium, where since the 1960s world-class long-distance runners have prepared for international races. Part of the government’s Vision 2030 development agenda, the renovation promised to turn old athletics tracks into an imposing modern stadium. However, the construction was started and then suspended. Suspension as an ethnographic observation and an analytical framework provides a nuanced account of infrastructural development, one that complicates state-sanctioned narratives of vision and emergence. Conceptualised as a process and a deliberate political action – rather than an ontic condition – suspension is a resource for political performance and economic speculation, a tool for the state to assert itself as a provider of development, but also a method of civic dissent.

‘Have you seen what they have done to the place?!’, Kemboi told me, disapprovingly.Footnote1 A former professional long-distance runner, he walked with me over the tracks of the Kamariny stadium, near the Elgeyo Marakwet County capital Iten, where many well-known Kenyan athletes trained. In line with Kenya’s Vision 2030 development agenda, the government’s selected contractor broke ground in 2017 and started building a modern stadium on the site of the former dirt track. However, the funds seemed to have run out and construction was obviously stalled, and now Kemboi and I were observing the protruding stones, dug-out trenches and skeletons of concrete grandstands left behind.

Despite his criticism, Kemboi also spoke about the planned project with anticipation. He had heard that the government made it an absolute priority to finalise the construction of a world-class modern stadium in a place that deserves it the most – a county that has nurtured some of the world’s most successful athletes. Since the 1960s, Kenya’s outstanding runners have dominated international competitions, from 3.000-meter track competitions to marathons (Bale & Sang Citation1996). Most of them trained and lived around Iten. It was unavoidable that the government would recognise those who have so prominently represented Kenya on the international stage by investing in Elgeyo Marakwet County, Kemboi suggested.

I was surprised by his tone and assessment. Only a few days earlier, we had discussed the reconstruction project, and he had been critical. In order to satisfy international standards, the government had decided to build a modern track with a hard surface that was unfavourable according to many seasoned athletes. ‘We prefer dirt tracks’, Kemboi told me, referring to a softer surface that many athletes felt was easier on their knees and joints. Not only was the governments’ stalling annoying, the entire planned construction project was misguided. Yet, as we found ourselves avoiding the rubble at the suspended construction site, Kemboi betrayed a sense of pride that the county would be granted a state-of-the-art stadium and running track.

Kemboi’s wavering attitude raises questions about stalled construction projects – of which there are many amid Kenya’s vision-driven development – and how they provoke apparently contradicting desires and positions. Was Kemboi frustrated because the new running track was left unfinished, or because, when finally finished, it will not effectively serve its intended purpose? If he was frustrated, why was he also excited about the prospect of an apparently inferior piece of infrastructure? Furthermore, why did the controversial project stall, and who exactly stalled it? Was it the government that started construction without sufficient funds, or was it the dissenting athletes and coaches who could have organised and stopped the construction? In other words, there is a need to carefully examine the nuances of people’s responses to state development promises beyond outright rejection or support, as well as to investigate the temporality, materiality and especially politics of suspended construction – why do projects stall, who are the political agents of this stalling, and what are the political consequences.

In the last two decades, studies of infrastructure and its complex temporalities, materialities and politics have proliferated in anthropology, geography and science and technology studies (Anand et al. Citation2018; Graham Citation2010; Graham & McFarlane Citation2015; Harvey et al. Citation2017; Hetherington Citation2019). Only recently however have scholars started explicitly theorising topics like infrastructures’ incompleteness, unfinished-ness and suspension. Akhil Gupta (Citation2018), for instance, writes how infrastructure development projects, especially in the cities of the global South, tend to be started and then seemingly eternally delayed, leaving behind rubble and ruins that slow down traffic and circulation of people and goods (instead of speeding them up, as infrastructure is meant to). Suspension is here a particular kind of temporality characterised by a sense of in-between-ness – between proverbial beginnings and ends of construction projects, but also between the promises of a prosperous modernity in the future, the relinquishment of the supposedly underdeveloped past, and the material reality of rubble and half-built structures in the present (see also: Hetherington Citation2017). Rather than thinking of it as a temporary and exceptional liminal state (Turner Citation1967: 93–111), or a dilapidating station on a one-way train ride towards modernity, Gupta insists that suspension should be dealt with as ‘a condition in its own right’ (Citation2018: 70), a temporal state with its own logic and contradictions. In a similar way, Ashley Carse and David Kneas (Citation2019) discuss unfinished and unbuilt infrastructure projects as producing ‘suspended presents’ (Citation2019: 18–20), temporal states in which construction delay results in contradictions between short-term and long-term futures, uncertain horizons and experiences of deferral, but also possibilities of ‘alternative renderings of project completion’ (Citation2019: 20). A related approach has been taken up by urban geographers who discuss infrastructures’ incompleteness. For instance, for Prince Guma (Citation2020), infrastructure is in a ‘never-ending state of becoming’ (Citation2020: 733). Guma, who draws on Francis Nyamnjoh’s notion of incompleteness (Citation2017) and AbdouMaliq Simone’s work on urban infrastructures (Citation2015), recovers infrastructural incompleteness from pejorative associations with failure and lack, and excavates its possibilities and creative potential.

This work is useful to analyse construction delays and interruptions like the one in Kamariny: it emphasises the processual character of infrastructure, questions the linear promise of modernity, interrogates multiple temporalities and open futures and considers both possibilities and constraints of suspension. Suspension is a useful concept because it captures affective states of uncertainty, instability, speculation and heightened attention that come with interruption and delay. It provokes questions: how fast is the project progressing? What will it look like in the future? Will the construction continue, or will it be abandoned? Will the proposed project be useful to the citizens? These are important questions to ask about infrastructural development in Kenya, especially in relation to contemporary Africanist anthropology that often argues that time in Africa is not a linear progression, but rather an ‘interlocking of presents, pasts, and futures’ (Mbembe Citation2001: 16); that African futures are plural and open-ended (Goldstone & Obarrio Citation2016); and that African social realities are in precarious but potent states of emergence and becoming (Péclard et al. Citation2020; Rubin et al. Citation2019; Van Wolputte et al. Citation2022). Such affective states of instability, anxiety and hope are however not exclusive to Africa, and are most vividly depicted in Simón Uribe’s ethnographic film about a protracted road construction in the Colombian Amazon, aptly titled Suspensión (Citation2019), in which we see the slow progress of a promising infrastructural project and the hopes and anxieties that come with it, but also the construction workers who have to navigate the unfinished bridges like tightropes, suspended in air, negotiating high altitudes and unruly landscapes. Suspension is a dizzying experience.

This work is less useful, however, when it claims that ‘infrastructures are always incomplete, always in process’ (Gupta Citation2018: 75), when it considers ‘the nature of infrastructure as inherently incomplete’ (Guma Citation2020: 729), or when it proclaims ‘the condition of suspension as an inherent state of infrastructure’ (Uribe Citation2021: 206). While all these authors account for human agency and politics, suspension or incompleteness often comes through as an abstract state of being, an almost inevitable ontic state that shapes infrastructure and human lives, rather than one produced by particular actors through their actions and labour (or refusal of labour). Carse and Kneas (Citation2019) suggest this critique when they show skepticism towards a sweeping proposition that ‘everything is unfinished’ (Citation2019: 13) and emphasise that suspension is ‘not a state of being but rather a social process’ (Citation2019: 18). Suspension as a political and social process especially comes through in Isaac Marrero-Guillamón’s (Citation2020) ethnographic treatment of the protracted building of a huge monument in the Canary Islands: here suspension is not an abstract state, but rather a result of actions of particular groups and individuals with differing values and goals, such as environmental activists, artists and government officials. After all, the word ‘to suspend’ also captures an action that refers to actively stopping or blocking a piece of work in its tracks, or otherwise postponing an undesirable outcome (Alexander Citation2023; Ramella et al. Citation2023), perhaps indefinitely, perhaps not. Furthermore, when enacted by state institutions, suspense can even be a mode of governance over marginalised subjects (Chatterjee et al. Citation2023). All this allows us to ask questions about politics: who is doing the suspending, for what reasons, and who are its winners and losers. It is therefore crucial to examine the human and institutional agents of suspension – who does it, who maintains it, and to what ends – and resist thinking of unfinished-ness as an abstract and inevitable state inherent to infrastructure, or to non-human entities, or to the proverbial global South, or to anything really.

The Kamariny stadium and running track, located in Kamariny village at the edge of Elgeyo escarpment near Iten town, is part of an elaborate sports infrastructure that has gradually developed in Kenya’s Elgeyo Marakwet County over the last six decades. This infrastructure, a socio-technical assemblage of physical forms and know-how that allows for the possibility of circulation of people, goods and ideas (Edwards Citation2003: 187–8; Harvey Citation2018: 84; Howe et al. Citation2016: 549; Larkin Citation2013: 327), includes material entities like running tracks, roads, forest paths, schools and housing complexes for (aspiring) athletes, as well as a knowledge network of coaches, experienced (former) athletes, sports managers and sports apparel companies. All these elements together provide women and men with training in athletics, as well as management of contracts and networks that allow them to travel abroad, take part in running events and competitions, and earn a living from athletics. Moreover, it is an infrastructure that is ‘relational and ecological’ (Star Citation1999: 377), not so much in the sense that it commodifies, exploits, or re-shapes the forces of nature (Carse Citation2012), but rather in the sense that it is in mutual entanglement (Ingold Citation2008) with the natural environment: Iten and its surroundings are situated at an altitude of roughly 2,400 metres, where the ‘thin air’ of the highlands makes long-distance running more difficult, but beneficial for training (Crawley Citation2020; Kovač Citation2023). The sports infrastructure is therefore made meaningful and effective by the natural environment in which it is set, as well as the know-how of experienced athletes and coaches (Kenyan and otherwise) who have over the decades developed training methods to harness the altitudinal potential of the highlands. Finally, as a whole, this regional sports infrastructure is largely effective, differing significantly from accounts of chronic infrastructural breakage and collapse in the proverbial global South (Anand Citation2017; De Boeck Citation2011; Mains Citation2012; McFarlane Citation2009; Schwenkel Citation2015; Smith Citation2020): Kenyan long-distance runners have for long famously dominated (and continue to dominate) international athletics, rivaled only by Ethiopian athletes, and Iten and its surroundings has been a training ground and a home to some of the most successful runners. The town itself has become a destination for international journalists and sports scientists who seek to uncover the ‘secrets’ of eastern Africa’s athletic success, and, as others have observed (Bale & Sang Citation1996; Crawley Citation2020; Gaudin & Wolde Citation2017), often end up with reductive and fallacious myths about ‘natural’ ability and motivating poverty, ignoring the impact of socio-technical and ecological infrastructure developed over decades. Elgeyo Marakwet’s sports infrastructure therefore largely continues to work – although, as we have seen in the opening vignette, the athletes increasingly need to deal with interruption and suspension.

While suspension in Kamariny is exceptional in the context of Iten’s sports infrastructure, it is not exceptional in Kenya (Kovač & Ramella Citation2023). Throughout the country, many impressing and imposing infrastructure projects that promise future prosperity seem to be perpetually under construction: they are outlined, started, or partially constructed, but eventually interrupted, delayed, or aborted. For instance, in Elgeyo Marakwet County, the construction of two mega-dams in Arror and Kimwarer was announced in 2016, but indefinitely suspended in 2019. The planners and constructors promised employment, electricity, tourism and irrigated agriculture to the region, however the construction stalled due to allegations of corruption and uncertainties over displacement of local residents (Bii Citation2022; Kahura & Bagnoli Citation2022). Elsewhere in Kenya, LAPSSET (Lamu Port – South Sudan – Ethiopia Transport Corridor), an enormous development corridor that in theory will include a seaport, an airport, a resort, highways and oil pipelines, has been planned since the late 2000s, and promises a bright future of regional connectivity and economic progress. Yet its execution has stalled, and its future is uncertain (Browne Citation2015; Chome Citation2020; Elliott Citation2016; Kochore Citation2016; Mkutu et al. Citation2021). The capital Nairobi is experiencing a construction boom, led by the Kenya Vision 2030 development plan that seeks to transform the city into a ‘world class African metropolis.’ A prominent example is Konza Tech City, a proposed IT hub and a hyper-modern technopolis, under construction around 60 kilometres from Nairobi. Announced in 2008 by the government as the ‘best-planned’ city in Africa, its construction is far behind schedule, and it is unclear whether this is a bad thing, and for whom: the techno-city will likely serve multinational IT and construction development companies, rather than the majority of local residents who will not be able to afford to live in it (Baraka Citation2021; Van den Broeck Citation2017). In general, the execution of infrastructural development in Nairobi has been wildly uneven (Smith Citation2019), leading many Kenyans to joke that the Vision 2030 plan is likely to turn into Vision 3020. Beyond the mega-projects, national newspapers frequently report about stalled construction projects all over the country: tarmacked roads, hospitals, markets, mortuaries, irrigation schemes, stadiums, schools, bridges, bus parks, water pipelines; in sum, infrastructure projects supposed to deliver public goods (Gisesa Citation2019). Beyond Kenya, one can find infrastructures that appear to be always under construction in eastern Africa (Mains Citation2019), the ‘global South’ (Gupta Citation2018), and practically everywhere (Carse & Kneas Citation2019). Kamariny therefore offers a case study of suspension that is anthropologically relevant for infrastructures everywhere, while also resistant to facile claims of incompleteness as unavoidable and typical.

If the temporality of suspended construction is marked by a sense of instability and in-between-ness, its materiality is largely represented by ruins, rubble and leftover materials, scattered around unfinished construction sites. In suspended Kamariny, these are the protruding stones of unfinished running tracks, skeletons of concrete grandstands, scattered unused raw construction materials, and dilapidating half-finished structures. Numerous analysts have interpreted ruins and rubble as signifiers of long-term deterioration or decay, material and affective residue of the past, remnants of colonialism, imperialism, warfare and capitalist exploitation that exert violence (Gordillo Citation2014; Hastrup Citation2023; Navaro-Yashin Citation2009; Stoler Citation2008) or inscribe forms of belonging (Fontein Citation2011) on subjects in the present. Here I am rather concerned with contemporary ruins and rubble: those produced by infrastructure and development projects that break ground to make material claims to a modernist future, but then stall, indefinitely (Gupta Citation2018; Harms Citation2016). Akhil Gupta once again writes about half-finished urban infrastructure projects as a ‘future in rubble’ and ‘ruins of the future’ (Citation2018: 65), and Vyjayanthi Rao examines ruins of development projects as ‘phantom debris of the project of modernization’ (Rao Citation2013: 314). These are useful theories, because they regard ruins and rubble as not exclusively products of the past. We are still however largely left with an abstract idea of ‘ruins’ as ‘immanent in the completion of projects’ (Gupta Citation2018: 72), and very little sense about who are the authors of these ruins, rubble and leftovers of the future, who is maintaining them and why, and what do people do with them (however, see: De Jong & Valente-Quinn Citation2018; Kopf Citation2022; Yarrow Citation2017). This is relevant for the case of Kamariny because, as we shall see, some form of rubble can be a desirable material state for certain actors, leftover materials are products of a specific kind of labour of maintenance, and ruins can also represent monuments to possibilities of civic contestation and protest.

Below I will unpack the temporality, materiality and politics of stalled construction in Kamariny: how people navigate its uncertainties, and how they engage with its ruins, rubble and leftover materials. As I will show, in Kamariny, ordinary Kenyans build their futures not necessarily from the possibilities opened up by the new construction project, but from the rubble of its suspension. Moreover, while the Kenyan state might promote its future-driven development agenda through promises of construction, relying on narratives of linear progress and modernity, these promises become meaningful and forceful through political performances amid the dizzying uncertainty of suspension. Finally, people’s discursive and corporeal engagement with ruins and rubble can signal frustration with stalled development, but also possibilities for contestation and protest. Suspension is, therefore, not an abstract or unavoidable state of being inherent to infrastructural development; rather, it is a political action and a political process, a tool through which a state can assert itself as a unique provider of development, but also a tool that can open up possibilities for civic dissent. Findings reported here draw from seven months of ethnographic research in Kenya’s Rift Valley, interrupted by COVID-19 pandemic-related travel restrictions, as well as from archival research in Kenya National Archives, Nation Centre newspapers archive and McMillan Memorial Library newspapers archive, all in Nairobi.

Nostalgia, Enchantment, Exclusion: Imagining the Future from Rubble

In 2017, the suspension of Kamariny stadium largely came courtesy of Kenyan national government and its Kenya Vision 2030 development plan. Officially launched in 2006, the plan promises to transform Kenya into a middle-income industrialised country. Globally, the plan is hardly an exception: many countries have adopted similar plans, drawing on powerful and notably open-ended language of ‘vision’ and ‘emergence.’ Hence, in Asia one finds Andhra Pradesh Vision 2020 (now Vision 2029) and Malaysia Vision 2020 (now Shared Prosperity Vision 2030), and in Africa Rwanda Vision 2020 (now Vision 2050) and Plan Sénégal Émergent, among many others. Kenya Vision 2030 has been described by geographers, anthropologists and journalists as at least partly neoliberal, in the sense of being driven by competition and market deregulation, inspired by the aesthetics of contemporary financial capitals like Dubai, Shanghai and Singapore, largely designed by international consultancy companies to accommodate global capital (Baraka Citation2021; Smith Citation2019; Watson Citation2014). At the same time, Kenya Vision 2030 is largely state-planned, and inspired by visions of state-driven and centrally planned growth and modernisation typical of Kenya’s (and Africa’s and Asia’s) 1960s post-independence period (Mosley & Watson Citation2016). Elsje Fourie (Citation2014), for instance, interviewed Kenyan elites involved in creation and implementation of the development plan, and found that they were inspired by countries like Singapore and Malaysia, not only because of these countries’ economic success, but also because of their colonial heritage and post-independence period of state-driven modernisation and economic growth, a history they shared with Kenya.

How did suspension in Kamariny come about? In 2013, with devolution, Kenya’s administrative and political decentralisation programme, the county governors were given extensive powers to drive and organise infrastructural development in their counties. In Elgeyo Marakwet County, the governor promised to ‘rehabilitate’ and ‘modernize’ the Kamariny stadium (Gekara Citation2014). The construction was started, but then interrupted in 2017. Notably, 2017 was another election year, and the national government had set aside ksh2 billion for the renovation of seven county stadiums, including close to ksh288 million for the one in Kamariny. The reported goal was to provide modern facilities for athletes, but also to bring the sports infrastructure in the entire country to an ‘international standard’, so that Kenya could host international sports competitions.Footnote2 The national government thus wanted to bring Elgeyo Marakwet into global circuits of people and capital – a strange reasoning, given that the area was already deeply enmeshed in those circuits by way of its internationally famous community of athletes. The Kamariny stadium construction was now dubbed a ‘flagship’ project of Kenya Vision 2030. A billboard sign depicting a computer-generated model of a modern stadium with imposing grandstands and parking lots was put up at the roadside, not unlike many other similar posters raised throughout Kenyan (Smith Citation2019) and African (De Boeck Citation2011) cities that have instilled the promises of prosperity and modernisation into the material fabric of everyday life (). After only a few months of work, the contractor, a Kenyan company, left the construction site. The workers demolished the old tracks, dug out the enlarged space for the new stadium, started levelling the grounds for the new building, but then left. The company cited lack of payments from the government. My interlocutors around Kamariny (quite reasonably) speculated that the government invested in the ambitious construction just before general elections in another case of performance of development and progress, only to later reveal that the funds were insufficient to continue with the construction.Footnote3 Like many other projects in the country, the Kamariny stadium construction was stopped, but not (yet) abandoned: it was suspended ().

Figure 1. A promising model: Road sign in Kamariny depicting the future stadium, 2019. Photo by Uroš Kovač.

How did the suspension of the Kamariny stadium and the rubble that the contractor left behind affect the Kenyans who were supposed to use the infrastructure? In 2019, Kenyan athletes, former athletes and coaches in Iten frequently reflected on the state of construction, and had a range of opinions and expectations, often contradictory, about what the stadium should look like in the future. This is what Kemboi (already quoted earlier) had to say about it:

Rudisha was training there. My training mate […] We did 90 percent of all our workouts here in Kamariny. […] It’s a famous track. […] This government wants to build so that every county has a Tartan track. But if it was me, they should have left Kamariny. They could have built somewhere else, maybe inside Iten [town]. Leave Kamariny the way it is, because Kamariny was wonderful for us.Footnote4

Athletes’ objections were far from universal: not everyone was nostalgic about the old Kamariny track and stadium. Consider how Elias, a 23-year-old aspiring runner who had moved to Iten a year before to train, responded to whether building a modern stadium was a good idea:

That would be excellent. In fact, that would be the best stadium in the region, and it would be perfect. They need to build it, and it is good that it is here, because this is a central place for athletes. All the champions are from here. […] If there are people saying there should not be a good Tartan here, these people themselves are the problem. Why would you not want to have a modern place of training here in Iten?

Suspended construction of the Kamariny track, authored by the Kenyan government, therefore provoked both enchantment and dissent (and at times simultaneously, as we can glean from the opening vignette). Imposing and impressive infrastructural projects that promise – but not immediately deliver – connectivity and progress indeed have a ‘capacity to enchant’ (Harvey & Knox Citation2012: 521), and especially to invigorate the idea of a nation state as a provider of future prosperity and inclusion, even when an earlier piece of infrastructure did the job well, or better. There was also dissent: as Claudia Gastrow (Citation2017) shows with a study of urban development in Angola, construction might be an easy way for states to perform capacity, but it can also be aesthetic fodder for citizens to voice critiques of the state. While in Angola it was the aesthetics of global world-class city-making that provoked people’s critiques, leading Gastrow to discuss ‘aesthetic dissent’ (Citation2017), in Kamariny the aesthetics of international sport and Vision 2030 seemed largely persuasive; it was rather the materiality of the running track that came into immediate contact with runners’ bodies that provoked dissent and reflection about governance, the future and the state, making dissent much more grounded in human bodies rather than in design and appearances.

It is important to underline that these athletes’ reflections were taking place in the context of rubble of suspended construction. All my interlocutors invariably pointed to the dug-out pipes, precariously scattered stones and leftover piles of sand and rock to emphasise that the track was in a horrendous state. While athletes had different perspectives on the track’s future, the rubble was their central source of frustration and a crucial material setting for reflection. For some, the rubble exemplified a disgraceful destruction of a once famous and useful piece of infrastructure; for others, it was a sign of the coming modernist future, and a source of frustration that this future was delayed or might never arrive. The main source of anxiety for many athletes was that the important stadium and its track would potentially end up like many other construction projects in Kenya: eternally delayed, never finished. The key issue for them was a possibility that a piece of infrastructural heritage, once famous, and potentially modern, could in the future remain in rubble, eternally suspended.

Notably, for some other athletes, this future of suspension was not the worst imaginable prospect. Despite the bad state of the Kamariny’s murram track that threatened injuries, a number of athletes in 2019 continued using it for their speedwork trainings (). After the contractor left, a group of athletes organised, cleared up some of the immediate rubble that occupied the track, and temporarily levelled the inner lanes to make them accessible for training. Some of them were poor, young, aspiring Kenyans who had moved to the area to pursue athletics for a living: Iten was a home to hundreds of young aspiring women and men who had moved there at considerable financial expense to their families and had no additional jobs to support themselves.Footnote5 For many of them, the Kamariny track remained a site where they could conduct their speedwork trainings for free. Kamariny was not the only track in the area, however other tracks either demanded a steep fee, or were far away from athletes’ lodgings around Iten and Kamariny and entailed paying for a transport ticket. Many aspiring athletes with no official managers or income had difficulties paying these fees on a regular basis and resorted to the Kamariny track as a free place for training.

Notably, some of these athletes argued that the newly planned Kamariny stadium was best permanently left ‘unfinished’. While they invariably lamented the government project’s destruction of the former track, they also feared that the completion of the new track would mean an imposition of entrance fees. It was not clear whether the new stadium, when ‘finished’, would impose fees for the use of the track. On the one hand, the stadium was promoted as a public good; on the other, modern tracks in other stadia throughout Kenya demanded frequent maintenance in order to retain international standard, and some of it was financed by charging entrance fees. The young athletes thus feared that the completion of the modern stadium would exacerbate the inequalities between athletes sponsored by management companies and poor aspiring athletes who had no income. They also presented an argument against the possibility of usurping the public nature of a piece of infrastructure.

The temporality of suspension therefore stretches beyond simply being between the projects’ beginning and the planned completion: suspending construction rather introduces the possibility that the state of in-between-ness might indefinitely extend into the future, and, for better or worse, leave the future open and uncertain. Aspiring athletes, like many other Kenyans (Smith Citation2019), are forced to confront this possibility and to struggle to productively inhabit and forge futures from it. Notably, rubble here is not a result of long-term deterioration (Gordillo Citation2014), but of suspended infrastructuring and, in particular, the chasing of material and aesthetic form that is purported to bring modernity to rural Elgeyo Marakwet. As such, it is a result of (so far) undelivered promise of modernity. At the same time however, the young athletes’ concerns about the consequences of ‘finished’ construction point to a larger issue that such modernist infrastructure in its ‘final’ form can bring about new forms of inequality. It is not that the young athletes were fond of the suspended running track; it is rather that, once the construction had already been suspended, they found that maintaining and using the site in its unfinished form (by clearing up immediate rubble and roughly levelling the track) was more expedient than pushing the government for a finished result that could mean their exclusion. For some, the uncertainty of indefinite suspension is a more advisable choice than a likelihood of exclusion. Suspension can therefore stand for the gap ‘between what was promised and what will be delivered’ (Gupta Citation2018:70), but also for strategic efforts to postpone the exclusion and inequality that the promised future might bring.

Caring for Remainders: Suspension and the Labour of Waiting

The potentials and uncertainties of suspension in Kamariny were perhaps most visible in stories and experiences of workers hired as ‘caretakers’ on the stadium’s construction site. The workers had a variety of positions: some were hired by the county government, others by different companies contracted at various times to construct parts of the stadium; some were regularly paid, others were not. Stories of these workers exemplified the dynamics of promise, opportunity and ‘stuckedness’ (Hage Citation2009b) characteristic of suspended infrastructuring, as well as a variety of interests of different actors invested in suspended construction.

Take, for instance, Edwin and Kibor, men in their early 50s, who moved from their home villages in Marakwet (some 90 km away) when they heard of a construction boom in and around Iten. They came looking for work, and quickly found one as caretakers for the company contracted to build the Kamariny stadium. As detailed in sections above, the work was started, but then suspended, and the construction workers left the site. Edwin and Kibor were hired in this period of suspension, and their main job was safeguarding the raw materials that were left behind, scattered around the construction site – iron rods, piles of sand and stone, pipes and planks of wood (). Edwin and Kibor moved into temporary mabati (‘corrugated iron sheets’) houses on the site that the company constructed for their workers, and were paid ksh400 per day, a common salary for casual workers. However, this lasted only for a few months, when the company stopped with salary payments. In 2020, Edwin and Kibor were still living on the site, two years after they had received the last payment. Communication with their ‘employer’ was scant. They resorted to temporary livelihood strategies: collecting seedlings from surrounding trees and selling them to families in the neighbourhood, clearing land for neighbouring farm owners for a small compensation, collecting logs and selling them to restaurants as firewood. They relied on short-term crops for subsistence: they used the land around the stadium to fence small farms, where they grew maize, potatoes, beans and managu (leafy green vegetables).

I often wondered why Edwin and Kibor would not leave the construction site and either look for salaried work elsewhere or return to Marakwet and farm. Another site caretaker, employed by the county government and handsomely paid, implied that they were lazy and enjoyed living on company’s premises for free. Edwin and Kibor acknowledged the benefits of free lodging and space they would not have as workers in urban settings: ‘At least here there is some land where I can plant [crops]. If I was in town, I could not.’ In contrast to accusations of laziness, they also argued that living in Kamariny allowed them to ‘keep hustling,’ if only for small jobs around neighbouring farms and hotels. However, Edwin also explained that their position was more akin to stuckedness in a liminal space:

I cannot leave this place now. It is not good for me, not good for [the contracted company]. Because we have been here now for so long. If we just leave we will not get any compensation, and the materials will be taken away. So we are just waiting for them to come back.

Furthermore, Edwin’s response that they were ‘just waiting’ was grounded in a promise: the company claimed that the construction project was stalled, and not abandoned, and that the caretakers would receive their backlogged salaries once the construction resumed in the future. It remained uncertain whether that would really be the case. It was clear, however, that the longer the caretakers stayed on the site, the more time they invested in the promise of compensation, making it increasingly unbeneficial for them to leave, and leaving them stuck: ‘the more one waits and invests in waiting, the more reluctant one is to stop waiting’ (Hage Citation2009b: 104).

Edwin’s and Kibor’s story demonstrates the contradictions between the promises of mobility and progress (the promise of a construction boom that attracts migrants; the promise of compensation that may come in the future; the promise of a modern piece of infrastructure) and the experience of stuckedness. This contradiction is not abstract, but is materially grounded: inscribed in the raw materials that demanded and produced labour, while also forcing the men to stay put; in the small pieces of land and the mabati houses that allowed the men to sustain a living, albeit a temporary one; in the imposing half-finished grandstand that towered over their dwellings that simultaneously suggested movement and stasis.

It is important to observe that Edwin’s and Kibor’s (unpaid) labour was not so much contingent on the construction of the stadium, but rather on its suspension. The men were driven to move to Kamariny by rumours of a construction boom, but eventually found work in its suspension. Their labour was grounded in the company’s struggle to prevent the materials from devolving into project leftovers or ‘remainders’ (Bize Citation2020) that the Kamariny residents would feel entitled to use for personal gain, and contingent on the company’s efforts to maintain the site and the materials in states of suspension and potentiality, rather than abandonment. This made the caretakers’ position even more uncertain: it was not clear whether they would receive the compensation if the company abandoned the project, or whether they would be out of work if the construction resumed. Here the agent of suspension was the construction company that sought to suspend ultimate failure and death of the project. The suspension materialised in the scattered materials, but was not contained by the materials themselves, rather by the unpaid labour of the caretakers who were tasked with guarding them and preventing them from deteriorating into free-for-all leftovers.

Notably, the labour of waiting that maintains suspension, exemplified here by the caretakers’ stories, is inextricable from politics and speculation: ‘waiting is not only shaped by the person waiting; it is also shaped by those who are providing whatever one is waiting for’ (Hage Citation2009a: 3). In Kamariny, this became clear in the summer of 2020, when the Kenyan government reportedly resumed the funding of the stadium construction. The Sports Chief Administrative Secretary gave promises: ‘soon athletes will be smiling because of good facilities’ (Rotich Citation2020a). The construction briefly resumed. Soon, however, the government officials issued an ultimatum to the contracted company to complete the construction in one month. ‘We are tired with dealing with rogue contractors who paint the Jubilee government as not delivering on its promises,’ said the Sports Kenya Director General (Kanyi & Kipkura Citation2020). Three months later, the contractor was accused of not making progress, and the contract was scrapped: ‘[W]e want the contractor to leave the site instead of wasting time and giving false hopes,’ a County Commissioner said (Kipkura Citation2020). Note here that these government officials’ political performances would not have been possible if the construction had not been suspended: the developmentalist state reproduces itself as a deliverer of growth and progress not only through construction, but also through suspension. It remained unclear how much money exactly the Kenyan government invested in the project, how one could reasonably build an entire stadium in 1–3 months, why the company resumed the work despite the unfeasible deadline, and what would happen with workers like Edwin and Kibor. It is clear however that suspension is a resource for political performance and economic speculation, a particular mode of action that demands labour and maintenance, and a tool that can be actively used in service of a variety of political and economic interests, rather than an inherent or inevitable property of infrastructural development.

The ‘Governor’s House:’ Ruin as Monument

Historically, the Kamariny stadium has always been more than a training ground. Since its construction in 1959 by the British colonial administration,Footnote6 it has been a place where Kenya’s wananchi (Swahili for ordinary citizens) came in contact with those who governed them. In 1959 the Queen of England (Elizabeth II) visited the area, and the colonial administration used the newly built stadium to organise a welcoming event that brought together the queen and the local residents, whom the British settlers called ‘the cliff-dwellers,’ referring to the Kalenjin groups (Keiyo and Marakwet) who occupied the edge of the escarpment.Footnote7 Nowadays, Kamariny residents speak fondly of the fact that the stadium hosted the queen, and Kenyan reporters have become particularly fond of contrasting the glory and the glitz of the queen’s visit to the deteriorating state of the stadium in recent times (For example, Rotich Citation2020b; Too Citation2010). Starting with November 1959, the new stadium also hosted biennial agricultural shows, in which livestock owners and farmers exhibited farm produce and pedigree livestock. The shows would attract more than 10.000 visitors,Footnote8 and the colonial District Commissioner at the time especially appreciated the amount of alcohol being sold.Footnote9 In a report, he opined about the 1959 show: ‘For two days a large section of the Elgeyo enjoyed themselves thoroughly and forgot about being governed.’Footnote10 He also wrote that the stadium and the showground ‘will prove a good investment and a constant source of publicity in the future.’Footnote11 After independence in 1963, the stadium continued to host agricultural shows. These were jovial events, as well as an apt stage for local and national politicians. Presidents and ministers gave speeches, praising government development plans and policies, namely Harambee during the presidency of Jomo Kenyatta in the 1970sFootnote12 and Nyayo during the presidency of Daniel arap Moi (who hails from the region) in the 1980s.Footnote13 The agricultural exhibitions finally dwindled in mid-1990s, and in 2019 one could still find remains of exhibition stalls around the running track (). Like other infrastructural and construction projects through which states and governance become visible (Dalakoglou Citation2017; Harvey & Knox Citation2015; Larkin Citation2008; von Schnitzler Citation2016), Kamariny stadium was a place where governors interacted with citizens through political performances and state-affirming rituals. If the British colonial administrators invested in the stadium and the showground hoping that ordinary Kenyans would forget about being governed,Footnote14 the postcolonial political elite hoped that they could keep reminding them.

In 2019, the suspended construction site in Kamariny was also marked by the presence of a prominent ruin, one that the residents referred to as the ‘governor’s house.’ At first glance, the deteriorating structure had little to do with the suspended stadium, however it was deeply intertwined with the broader sports infrastructure that made the region internationally famous and attractive to visitors from abroad, and was a striking presence on the piece of land that was, according to Kamariny residents, public land allocated to the new stadium. It is worth considering its short history to understand how suspending construction can also be a method of contestation and dissent.

In 2013 devolution in Kenya created responsibilities for the new county governments. They were now responsible for producing their own visions of progress and development, in line with the government’s Vision 2030 programme. In Elgeyo Marakwet County, the focus became the increasing number of sports-related tourists, both amateur and professional athletes who flocked to the county to train with Kenyan athletes, inspired by their international success. The county started emphasising sports-related tourism and reconstruction of sports-related infrastructure. It was also highlighting its huge potential for tourism in general, and was promising tourism-related infrastructure: a game reserve was being developed in the lowlands, and a large cable car that would transport tourists between the highlands and the lowlands was being planned. In 2019 the game reserve was almost unreachable, due to lack of road infrastructure, and the cable car was only spoken about as a potential project.

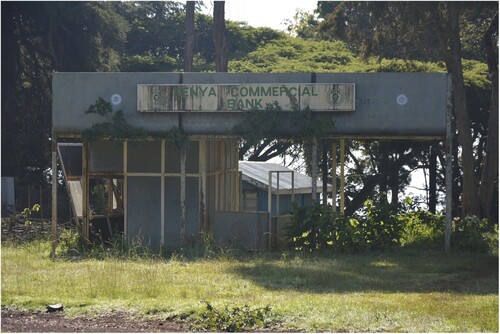

Moreover, devolution transformed the newly elected county governors into highly prominent figures with a range of new jurisdictions and power. In 2015, the office of the county governor of Elgeyo Marakwet County reportedly received 12 million shillings from the national government to purchase a piece of land, and another 50 million shillings were earmarked to construct a residence and an office for the ruling governor and his successors. In the second half of 2015, however, it appeared that the structure was not going to be built on a purchased piece of land: the construction was started on land that had been designated as public, allegedly allocated to the construction of the modernised Kamariny stadium, on the edge of escarpment in Kamariny, overlooking the lowlands of the Kerio Valley (Suter Citation2015a). The construction was, however, swiftly suspended: in 2019, the unfinished skeleton of the started construction was left behind a steel fence to deteriorate and merge with the surrounding overgrown grass. It was left to become a ruin ().

On the surface, the ruin reflects another stalled project, one among many reported by the Kenyan media. Elgeyo Marakwet County was not an exception: it was reported that the construction of similar offices was stalled in several North Rift counties despite the millions of shillings invested. Journalists reported on the ‘risk of the projects becoming white elephants.’ They emphasised that the projects were still ‘skeleton structure[s]’ despite the investments, ‘abandoned’ and ‘homes to a range of creatures’ (Bii & Matoke Citation2018). Auditor reports emphasised that such projects ‘remain undone’ and ‘continue to deteriorate’, and expressed ‘concern that the county has not obtained value for money’ (Bii Citation2019). Such reports take suspension and ruins as evidence of corruption and mismanagement of funds.

Broadly speaking, these interpretations are not incorrect, but the story of the Kamariny ruin is more complex. The issue of the ‘governor’s house,’ as it was called by the locals, first came about in my fieldwork when I interviewed one of the Kamariny ward representatives, who referred to the ruin as a ‘monument.’ He explained that the Kamariny residents suspected that the governor pocketed the money and grabbed a piece of public land. The reference to a ‘house,’ rather than ‘office’ (which would have been the county government’s preferred term), reflected their conviction that the structure was being built for the sake of private profit: they suspected that the governor was building a personal house and a tourist resort with a view over the escarpment that would bring him tremendous financial benefit. Their suspicions were related to the structure’s location on the edge of escarpment. Over the last two decades, the land on the edge of Elgeyo escarpment has come to be in high demand. With the first construction of a lavish resort by a mzungu (white foreigner), it became increasingly clear that the panoramic view had tourist potential.Footnote15 Since then, the price of land along the escarpment has sky-rocketed: according to some estimations, it increased 10-fold in the last decade, and much of it was bought by the Iten’s wealthy residents, such as famous runners, or visiting Westerners who could afford the high prices. Moreover, some Kamariny locals speculated that the ‘governor’s house’ was being built close to where a previously mentioned cable car was to be constructed. The edge of escarpment was therefore a prime site in which a tourist boom could be exploited. The Kamariny residents clearly saw the county governor as a member of the local elite who sought to use their position to exploit the promises of the tourist industry.Footnote16 In September 2015, they protested and forcefully stopped the construction (Suter Citation2015c), and later won a case at the Kenya’s High Court and legally prevented the construction to continue.Footnote17 The Kamariny ward representative, one of the protest organisers, thus referred to the ruin of the ‘governor’s house’ as a ‘monument’ to a victory over nepotism and corruption.

It was therefore the organised residents who suspended the construction, in the sense of blocking it and stopping it in its tracks, perhaps indefinitely. They suspected that individuals with access to future development plans and public resources could predict how exactly the area would develop in the future, and could begin setting themselves up to reap financial profits. They were therefore concerned with the possibility of hidden motives and agendas that drove public projects, aware that their implementation might have much more to do with restoration of patron-client relations than fulfilment of technical objectives (see Larkin Citation2013: 334; Mbembe & Roitman Citation1995: 334–5). In other words, the ruin represents concerns that the local ‘economy of anticipation’ (Cross Citation2015), i.e. the economy driven by anticipation of future possibilities opened up by development projects, was rigged. The ruin also represents suspicions over the ‘underneath of things’ (Ferme Citation2001; Smith Citation2020), i.e. the possibility that the implementation of public projects was not driven by their surface-level use, but instead by concealed political and economic motives. But more than this, the ruin represents possibilities of local politics to enact dissent through suspension. As Madeleine Reeves (Citation2017) argues, construction projects designed to deliver public goods tend to generate all kinds of politics, not only in the sense of materialising particular political aspirations, but also in the sense of producing temporary political communities that rally around desires for – or rejections of – particular projects (Citation2017: 716–717). The latter has indeed happened in the case of the ‘governor’s house,’ and suspension was a method of political action.

A caveat is necessary here: not all Kamariny residents protested against the construction of the ‘governor’s house,’ as few saw it as a potential impetus for further construction of tarmac roads in the rural area. Regardless, the ruin of the ‘governor’s house’ (or ‘governor’s office,’ depending on the perspective) stands for anticipation of speculative politics, a material remnant of the likelihood of nepotism that many Kenyans have grown to expect from political elites. But more than that, it is a gesture towards political contestation: the possibility of local level politics and protest. Ruins and suspension can thus signal deterioration, graft, or unfulfilled promises, but also possibilities for political action and dissent.

Conclusion: Temporality, Materiality and Politics of Suspension

‘Time of construction is also a time of destruction’ (Mains Citation2019: 6), argues Daniel Mains in a book about infrastructure and state-driven development in Ethiopia, and offers construction as an analytical framework to understand change in Africa beyond narratives of ‘abjection’ (Ferguson Citation1999) and the ‘bright continent’ (Olopade Citation2014). This idea certainly applies to Kamariny, where breaking the ground for the construction of the new stadium threatened destruction of a useful piece of infrastructure that was considered local heritage. It does not however capture the variety of practices of stopping, stalling and waiting that surrounded the construction project, one of many in Kenya, but a jarring exception in Iten’s elaborate and effective sports infrastructure. Suspension as an ethnographic observation and an analytical framework therefore allows us to ‘tell richer narratives about the life of infrastructure’ (Gupta Citation2018: 72), as well as nuanced accounts of temporality of development in Kenya, Africa, and everywhere else, accounts that complicate state-sanctioned narratives of vision and emergence.

Suspension as a framework becomes especially meaningful if we carefully consider who does it, who maintains it, or who has an interest in it: in Kamariny, these are the state (and its different levels), the runners, the construction company, the caretakers and the local residents, all different actors invested in – or frustrated by – suspension in different ways and for different reasons. Considered as such, suspension is more than an ontic condition, and more than a gap between promises of progress and realities of under-deliverance, but rather a process and a multiple, political and with a variety of meanings. It can represent strategic efforts to postpone a finished result, active attempts to avoid ultimate failure and death of a project, a stage for political performance of development, or a resource for political action and dissent. All these instances point to suspension as a key temporal characteristic of infrastructural development, not inevitable and immanent, but rather a product of deliberate political action.

In the time–space of suspension, ruins, rubble and scattered materials are material starting points for action and reflection. Ruins can signify stalled and uneven development, but also possibilities for contesting a rigged economy of anticipation. Rubble can stand for frustration with suspended construction, but also strategic attempts to avoid exclusion. Scattered materials can be invested with labour in order to render them as things with potentiality, rather than remainders or inert objects. All these ethnographic examples point to vibrancy, vitality and agency of matter itself (Bennett Citation2010), but one that only acquires force and meaning when it is imbued with particular human or institutional labour and political action. As Mary Douglas (Citation1966) famously argued in her analysis of pollution, dirt might be a ‘matter out of place’ (Citation1966: 36), but its out-of-place-ness is not inherent to its materiality: ‘[t]here is no such thing as absolute dirt: it exists in the eye of the beholder’ (Citation1966: 2), and ‘[d]irt is the by-product of a systematic ordering and classification of matter’ (Citation1966: 36). More recently, similar arguments have been made by Yael Navaro-Yashin (Citation2009: 14–15) and Madeleine Reeves (Citation2017: 729–730) about ruins and infrastructures respectively, namely that their materiality becomes socially meaningful through the ways they are imbued with disparate affects and practices – hopes, fears and political desires. Contradictions of suspension therefore become tangible through matters of ruin, rubble and leftover, but only because these are imbued with particular affects, politics and labour.

At the time of writing of this article, the question whether Kamariny stadium will be finished, and in which form, remains open. In 2021, members of Kenya’s political elite publicly showed efforts to finish construction projects in order to secure their legacy before the next round of elections (Koech & Atieno Citation2021). In 2023, members of the newly elected Elgeyo Marakwet County government ordered minor maintenance work to make the Kamariny running track more appropriate for athletics training, while leaving the possibility and the promise of a future state-of-the-art stadium open (Rutto Citation2023). This underlines the point that suspension is political: grounds for political performance and state-affirming rituals designed to maintain the state’s role as a provider of future prosperity. In the meantime, ordinary Kenyans continue to anticipate, negotiate and contest the future in and through suspension.

Acknowledgements

My deepest gratitude goes to my friends and interlocutors – athletes, coaches, journalists, their friends and families, and many others – in Kenya’s Elgeyo Marakwet County for their knowledge, time and patience. This paper is a result of a workshop entitled ‘Living with Ruins: Future-Making and Infrastructuring in Contemporary Kenya,’ organised in March 2020 at the British Institute in Eastern Africa (BIEA) in Nairobi, by Anna Lisa Ramella and I. I thank BIEA, Anna, and all the participants for engaging discussions and input on earlier drafts: Léa Lacan, Mario Schmidt, Prince Guma, Wangui Kimari, Franziska Fay, David Greven and Eric Kioko. I presented earlier versions of this article at the ‘Future Rural Africa’ Collaborative Research Centre online meeting in February 2021 and at the European Conference on African Studies (ECAS) in June 2023 in Cologne. I thank all the participants for their feedback, especially Arvid van Dam, Gideon Tups, David Anderson, Detlef Müller-Mahn, Kennedy Mkutu and Marie Müller-Koné. I thank Dorothea Schulz for supporting my ethnographic research in northwest Kenya and my academic work at the University of Münster. Special thanks go to Gladys Serem and Winnie Cheruiyot for assistance with interviews in Kamariny, to Magrine Chepkiyeng for hosting me in Iten, and to Alfred Anangwe for assistance in Kenya National Archives in Nairobi. Finally, thank you to Nils Bubandt and the Ethnos editorial team for their guidance and efficiency, and to the five anonymous reviewers (three for this submission and two for an earlier version) who provided constructive criticism and generous feedback.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 All names, except for well-known public figures, have been changed to pseudonyms in order to maintain anonymity.

2 ‘Government Sets Aside Sh2bn for Renovation of Seven County Stadiums,’ Daily Nation, June 26, 2017; Rotich (Citation2019).

3 Stalled development of stadia in particular were often brought up by Kenyan media to illustrate undelivered campaign trail promises. For example: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UXr0VmQVOUA. Accessed April 16, 2021.

4 I reproduce this quote from another publication of mine (Kovač Citation2023), where I explain in detail the matters of the running surface and the physical impact of the materiality of the running track. Here I focus instead on the athletes’ nostalgia.

5 Many athletes argued that the only way to succeed in athletics was to solely focus on the sport and the very demanding trainings.

6 Elgeyo-Marakwet District Annual Report 1959, Kenya National Archives (KNA) DC/ELGM/1/7.

7 ‘Nakuru to Equator ‘Most Beautiful Journey in the World.’’ East African Standard, February 16, 1959; ‘Climax to Tribal Dancing by Elgeyo: Colourful Spectacle for Royal Visitor.’ East African Standard, February 17, 1959; Matheson (Citation1959).

8 Elgeyo-Marakwet District Annual Report 1959, KNA DC/ELGM/1/7.

9 Elgeyo-Marakwet Monthly Report, November 1959. In ‘Elgeyo-Marakwet reports 1956–1959,’ KNA DC/TAM/2/1/29.

10 Elgeyo-Marakwet District Annual Report 1959, KNA DC/ELGM/1/7.

11 Elgeyo-Marakwet District Annual Report 1959, KNA DC/ELGM/1/7.

12 ‘Exploit Your Land, Urges Dr. Onyonka,’ Daily Nation, February 17, 1971.

13 ‘Land of Many Contrasts,’ Daily Nation, January 26, 1989.

14 The social and political context in which the British administration built the stadium and the showground in 1959 is relevant. Until the mid-1930s, the colonial government, in agreement with the white British and Afrikaner settlers, forbid the indigenous Keiyo to settle in the region’s highlands. The white settlers reserved the fertile highlands for themselves and confined the Keiyo to a ‘native reserve’ in the semi-arid tsetse fly-infested valley floor. The imposed Keiyo reserve served the administration as a supply of manual labour for work on the settlers’ enormous farms. Some Keiyo workers protested the low wages and labouring under a whip by stealing settlers’ cattle. In the 1930s the administration gradually relaxed the rules, and a number of ‘pioneer’ Keiyo farmers and herders ‘climbed the cliff’ and started settling in the highlands along the escarpment (including today’s Iten and Kamariny), where they started farming, building modern houses, and opening shops and kiosks. In the 1950s these rules of settlement relaxed even more. This was likely a response to unrest elsewhere in British Kenya: with the experience of the Mau Mau rebellion escalating in the 1950s, the colonial administrators likely sought to avoid further rebellion from the Keiyo whom they had already considered disobedient cattle thieves (Chebet & Dietz Citation2000: 136–63; see also: Lynch Citation2011; Massam Citation1927).

15 Europeans have long admired the area’s scenery: an Elgeyo-Marakwet District colonial administrator wrote in 1927 that Kamariny offered ‘possibly the finest view in Kenya’ (Massam Citation1927: 2).

16 This interpretation is not far-fetched in the context of several simultaneous allegations of abuse of public funds. See: Suter (Citation2015b).

17 Judgment on Petition No. 18 of 2015 at the Environment and Land Court of Kenya at Eldoret. http://kenyalaw.org/caselaw/cases/view/121069. Accessed March 26, 2021.

References

- Alexander, Catherine. 2023. Suspending Failure: Temporalities, Ontologies, and Gigantism in Fusion Energy Development. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 29(S1):114–132. doi:10.1111/1467-9655.13905.

- Anand, Nikhil. 2017. Hydraulic City: Water and the Infrastructures of Citizenship in Mumbai. Durham: Duke University Press. doi:10.1215/9780822373599.

- Anand, Nikhil, Akhil Gupta & Hannah Appel (ed). 2018. The Promise of Infrastructure. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Bale, John & Joe Sang. 1996. Kenyan Running: Movement Culture, Geography and Global Change. London: Frank Cass.

- Baraka, Carey. 2021, June 1. The Failed Promise of Kenya’s Smart City. Rest of World. https://restofworld.org/2021/the-failed-promise-of-kenyas-smart-city/#:~:text=While%20the%20government%20promised%20that,the%20country’s%20average%20annual%20income.

- Bennett, Jane. 2010. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Bii, Barnabas. 2019, January 27. North Rift Counties Face the Heat Over Irregular Spending. Daily Nation.

- Bii, Barnabas. 2022, January 5. Land Pay Pain for Arror, Kimwarer Residents after Mega Dams Project Stall. Business Daily Africa.

- Bii, Barnabas & Tom Matoke. 2018, March 19. Millions Wasted in Incomplete Governor’s Residences. Daily Nation.

- Bize, Amiel. 2020. The Right to the Remainder: Gleaning in the Fuel Economies of East Africa’s Northern Corridor. Cultural Anthropology, 35(3):462–486. doi:10.14506/ca35.3.05.

- Browne, Adrian J. 2015. LAPSSET: The History and Politics of an Eastern African Megaproject. London: Rift Valley Institute.

- Carse, Ashley. 2012. Nature as Infrastructure: Making and Managing the Panama Canal Watershed. Social Studies of Science, 42(4):539–563.

- Carse, Ashley & David Kneas. 2019. Unbuilt and Unfinished: The Temporalities of Infrastructure. Environment and Society: Advances in Research, 10(1):9–28. doi:10.3167/ares.2019.100102.

- Chatterjee, Syantani, Luciana Chamorro & Fernando Montero. 2023. Held in Suspense: Promise, Threat and Revocability as Modalities of Governance. The Cambridge Journal of Anthropology, 41(1):1–16. doi:10.3167/cja.2023.410102.

- Chebet, Susan & Ton Dietz. 2000. Climbing the Cliff: A History of the Keiyo. Eldoret: Moi University Press.

- Chome, Ngala. 2020. Land, Livelihoods and Belonging: Negotiating Change and Anticipating LAPSSET in Kenya’s Lamu County. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 14(2):310–331. doi:10.1080/17531055.2020.1743068.

- Crawley, Michael. 2020. Out of Thin Air: Running Wisdom and Magic from Above the Clouds in Ethiopia. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Cross, Jamie. 2015. The Economy of Anticipation: Hope, Infrastructure, and Economic Zones in South India. Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East, 35(3):424–437. doi:10.1215/1089201X-3426277.

- Dalakoglou, Dimitris. 2017. The Road: An Ethnography of (Im)Mobility, Space, and Cross-Border Infrastructures in the Balkans. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- de Boeck, Filip. 2011. Inhabiting Ocular Ground: Kinshasa’s Future in the Light of Congo’s Spectral Urban Politics. Cultural Anthropology, 26(2):263–286. doi:10.1111/j.1548-1360.2011.01099.x.

- de Jong, Ferdinand & Brian Valente-Quinn. 2018. Infrastructures of Utopia: Ruination and Regeneration of the African Future. Africa, 88(2):332–351. doi:10.1017/S0001972017000948.

- Douglas, Mary. 1966. Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concept of Pollution and Taboo. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Edwards, Paul N. 2003. Infrastructure and Modernity: Force, Time, and Social Organization in the History of Sociotechnical Systems. In Modernity and Technology, edited by Thomas J. Misa, Philip Brey and Andrew Feenberg, 185–225. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Elliott, Hannah. 2016. Planning, Property and Plots at the Gateway to Kenya’s “New Frontier”. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 10(3):511–529. doi:10.1080/17531055.2016.1266196.

- Ferguson, James. 1999. Expectations of Modernity: Myths and Meanings of Urban Life on the Zambian Copperbelt. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Ferme, Mariane C. 2001. The Underneath of Things: Violence, History, and the Everyday in Sierra Leone. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Fontein, Joost. 2011. Graves, Ruins, and Belonging: Towards an Anthropology of Proximity. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 17(4):706–727.

- Fourie, Elsje. 2014. Model Students: Policy Emulation, Modernization, and Kenya’s Vision 2030. African Affairs, 113(453):540–562. doi:10.1093/afraf/adu058.

- Gastrow, Claudia. 2017. Aesthetic Dissent: Urban Redevelopment and Political Belonging in Luanda, Angola. Antipode, 49(2):377–396. doi:10.1111/anti.12276.

- Gaudin, Benoit & Bezabeh Wolde (ed). 2017. Kenyan and Ethiopian Athletics: Towards an Alternative Scientific Approach. Addis Ababa: IRD.

- Gekara, Emeka-Mayaka. 2014, April 13. Governor: Judge Me on Health This Year. Daily Nation.

- Gisesa, Nyambega. 2019, March 31. Counties Pump Billions into Stalled Projects. Daily Nation.

- Goldstone, Brian & Juan Obarrio (ed). 2016. African Futures: Essays on Crisis, Emergence, and Possibility. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. doi:10.7208/chicago/9780226402413.001.0001.

- Gordillo, Gastón R. 2014. Rubble: The Afterlife of Destruction. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Graham, Stephen (ed). 2010. Disrupted Cities: When Infrastructure Fails. London: Routledge.

- Graham, Stephen & Colin McFarlane (ed). 2015. Infrastructural Lives: Urban Infrastructure in Context. London: Routledge.

- Guma, Prince K. 2020. Incompleteness of Urban Infrastructures in Transition: Scenarios from the Mobile Age in Nairobi. Social Studies of Science, 50(5):728–750. doi:10.1177/0306312720927088.

- Gupta, Akhil. 2018. The Future in Ruins: Thoughts on the Temporality of Infrastructure. In The Promise of Infrastructure, edited by Nikhil Anand, Akhil Gupta and Hannah Appel, 62–79. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Hage, Ghassan. 2009a. Introduction. In Waiting, edited by Ghassan Hage, 1–14. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press.

- Hage, Ghassan. 2009b. Waiting Out the Crisis: On Stuckedness and Governmentality. In Waiting, edited by Ghassan Hage, 97–106. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press.

- Harms, Erik. 2016. Luxury and Rubble: Civility and Dispossession in the New Saigon. Oakland: University of California Press.

- Harvey, Penny. 2018. Infrastructures in and out of Time: The Promise of Roads in Contemporary Peru. In The Promise of Infrastructure, edited by Nikhil Anand, Akhil Gupta and Hannah Appel, 80–101. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Harvey, Penelope, Casper Jensen & Atsuro Morita (ed). 2017. Infrastructures and Social Complexity: A Companion. London: Routledge.

- Harvey, Penny & Hannah Knox. 2012. The Enchantments of Infrastructure. Mobilities, 7(4):521–536. doi:10.1080/17450101.2012.718935.

- Harvey, Penny & Hannah Knox. 2015. Roads: An Anthropology of Infrastructure and Expertise. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Hastrup, Kirsten. 2023. The End of Nature? Inughuit Life on the Edge of Time. Ethnos, 88(1):13–29. doi:10.1080/00141844.2020.1853583.

- Hetherington, Kregg. 2017. Surveying the Future Perfect: Anthropology, Development, and the Promise of Infrastructure. In Infrastructures and Social Complexity: A Companion, edited by Penelope Harvey, Casper Jensen and Atsuro Morita, 40–50. London: Routledge.

- Hetherington, Kregg (ed). 2019. Infrastructure, Environment, and Life in the Anthropocene. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Howe, Cymene, Jessica Lockrem, Hannah Appel, Edward Hackett, Dominic Boyer, Randal Hall & Matthew Schneider-Mayerson, et al. 2016. Paradoxical Infrastructures: Ruins, Retrofit, and Risk. Science Technology and Human Values, 41(3):547–565. doi:10.1177/0162243915620017.

- Ingold, Tim. 2008. Bindings Against Boundaries: Entanglements of Life in an Open World. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 40(8):1796–1810. doi:10.1068/a40156.

- Kahura, Dauti & Lorenzo Bagnoli. 2022, April 11. Arror and Kimwarer: Theft on a Grand Scale. The Elephant.

- Kanyi, Joseph & Evans Kipkura. 2020, July 1. Government Issues Ultimatums for Work on Kamariny, Ruring’u Stadiums. Daily Nation.

- Kipkura, Evans. 2020, September 17. Why Work on Kamariny Stadium Has Been Suspended. Daily Nation.

- Kochore, Hassan H. 2016. The Road to Kenya?: Visions, Expectations and Anxieties Around New Infrastructure Development in Northern Kenya. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 10(3):494–510. doi:10.1080/17531055.2016.1266198.

- Koech, Gilbert & Effie Atieno. 2021, February 3. Uhuru Deploys Cabinet Secretaries to Speed Up Legacy Projects. The Star.

- Kopf, Charline. 2022. ‘Dakar-Bamako: Waiting for a Train Ride Back to the Future’. Leuven, Oslo: KU Leuven, University of Oslo.

- Kovač, Uroš. 2023. “A Place for Training, Not for Competition”: Negotiations of Competition and Agency among Long-Distance Runners in Kenya. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 29(3):648–669. doi:10.1111/1467-9655.13961.

- Kovač, Uroš & Anna Lisa Ramella. 2023. From Ruins and Rubble: Promised and Suspended Futures in Kenya (and Beyond). Journal of Eastern African Studies, 17(1–2):141–164. doi:10.1080/17531055.2023.2245263.

- Larkin, Brian. 2008. Signal and Noise: Media, Infrastructure, and Urban Culture in Nigeria. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Larkin, Brian. 2013. The Politics and Poetics of Infrastructure. Annual Review of Anthropology, 42:327–343. doi:10.1146/annurev-anthro-092412-155522.

- Lynch, Gabrielle. 2011. I Say To You: Ethnic Politics and the Kalenjin in Kenya. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Mains, Daniel. 2012. Blackouts and Progress: Privatization, Infrastructure, and a Developmentalist State in Jimma, Ethiopia. Cultural Anthropology, 27(1):3–27. doi:10.1111/j.1548-1360.2011.01124.x.

- Mains, Daniel. 2019. Under Construction: Technologies of Development in Urban Ethiopia. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Marrero-Guillamón, Isaac. 2020. Monumental Suspension: Art, Infrastructure, and Eduardo Chillida’s Unbuilt Monument to Tolerance. Social Analysis, 64(3):26–47. doi:10.3167/sa.2020.640303.

- Massam, J. A. 1927. The Cliff Dwellers of Kenya. London: Seeley, Service, and Co. Limited.

- Matheson, Alastair. 1959, January 30. Cliff Dwellers Will Welcome the Queen Mother. East African Standard.

- Mbembe, Achille. 2001. On the Postcolony. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Mbembe, Achille & Janet Roitman. 1995. Figures of the Subject in Times of Crisis. Public Culture, 7(2):323–352. doi:10.1215/08992363-7-2-323.

- McFarlane, Colin. 2009. Infrastructure, Interruption, and Inequality: Urban Life in the Global South. In Disrupted Cities: When Infrastructure Fails, edited by Stephen Graham and Simon Marvin, 131–144. London: Routledge. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/rug/detail.action?docID=452313.

- Mkutu, Kennedy, Marie Müller-Koné & Evelyne Atieno Owino. 2021. Future Visions, Present Conflicts: The Ethnicized Politics of Anticipation Surrounding an Infrastructure Corridor in Northern Kenya. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 15(4):707–727. doi:10.1080/17531055.2021.1987700.

- Mosley, Jason & Elizabeth E. Watson. 2016. Frontier Transformations: Development Visions, Spaces and Processes in Northern Kenya and Southern Ethiopia. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 10(3):452–475. doi:10.1080/17531055.2016.1266199.

- Navaro-Yashin, Yael. 2009. Affective Spaces, Melancholic Objects: Ruination and the Production of Anthropological Knowledge. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 15(1):1–18. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9655.2008.01527.x.

- Nyamnjoh, Francis B. 2017. Incompleteness: Frontier Africa and the Currency of Conviviality. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 52(3):253–270. doi:10.1177/0021909615580867.

- Olopade, Dayo. 2014. The Bright Continent: Breaking Rules and Making Change in Modern Africa. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Péclard, Didier, Antoine Kernen & Guive Khan-Mohammad. 2020. États d’émergence. Le Gouvernement de La Croissance et Du Développement En Afrique. Critique Internationale, 89(4):9–27. doi:10.3917/crii.089.0012.

- Ramella, Anna Lisa, Mario Schmidt & Megan A. Styles. 2023. Suspending Ruination: Preserving the Ambiguous Potentials of a Kenyan Flower Farm. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 17(1–2):165–185. doi:10.1080/17531055.2023.2231785.

- Rao, Vyjayanthi. 2013. The Future in Ruins. In Imperial Debris: On Ruins and Ruination, edited by Ann Laura Stoler, 287–321. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Reeves, Madeleine. 2017. Infrastructural Hope: Anticipating “Independent Roads” and Territorial Integrity in Southern Kyrgyzstan. Ethnos, 82(4):711–737. doi:10.1080/00141844.2015.1119176.

- Rotich, Bernard. 2019, January 19. Speed up! Echesa Urges Kip Keino Stadium Contractors. Daily Nation.

- Rotich, Bernard. 2020a, June 7. Flicker of Hope as Work Resumes at Kamariny Stadium. Daily Nation.

- Rotich, Bernard. 2020b, July 8. Kamariny Coming Up From Scratch. Nation.

- Rubin, Joshua D., Susanna Fioratta & Jeffrey W. Paller. 2019. Ethnographies of Emergence: Everyday Politics and Their Origins Across Africa Introduction. Africa, 89(3):429–436. doi:10.1017/S0001972019000457.

- Rutto, Stephen. 2023, February 8. Kamariny Stadium to Open for Training Six Years after Closure. The Standard.

- Schwenkel, Christina. 2015. Spectacular Infrastructure and Its Breakdown in Socialist Vietnam. American Ethnologist, 42(3):520–534. doi:10.1111/amet.12145.

- Simone, AbdouMaliq. 2015. Passing Things Along: (In)Completing Infrastructure. New Diversities, 17(2):151–162.

- Smith, Constance. 2019. Nairobi in the Making: Landscapes of Time and Urban Belonging. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer. doi:10.2307/j.ctvfrxrms.

- Smith, Constance. 2020. Collapse: Fake Buildings and Gray Development in Nairobi. Focaal, 2020(86):11–23. doi:10.3167/fcl.2020.860102.

- Star, Susan Leigh. 1999. The Ethnography of Infrastructure. American Behavioral Scientist, 43(3):377–391.

- Stoler, Ann Laura. 2008. Imperial Debris: Reflections on Ruins and Ruination. Cultural Anthropology, 23(2):191–219. doi:10.1525/can.2008.23.2.191.

- Suter, Philemon. 2015a, October 2. Assembly Wants Ritual in Governor’s House Saga. Daily Nation.

- Suter, Philemon. 2015b, October 5. Tolgos Sacks Accounts Chief, Warns Other Staff. Daily Nation.

- Suter, Philemon. 2015c, September 30. Work on Tolgos’ Sh50m House Halted. Daily Nation.

- Too, Emmanuel. 2010, March 5. Showground Queen Opened Now a Ghost Field. The Standard.

- Turner, Victor. 1967. The Forest of Symbols: Aspects of Ndembu Ritual. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Uribe, Simón (director). 2019. Suspensión (ethnographic film). Icarus Films (distributor).

- Uribe, Simón. 2021. Suspension: Space, Time and Politics in the Never-Ending Story of an Infrastructure Project in the Andean-Amazon Region of Colombia. Antipoda, 2021(42):205–229. doi:10.7440/antipoda42.2021.09.

- van den Broeck, Jan. 2017. “We Are Analogue in a Digital World”: An Anthropological Exploration of Ontologies and Uncertainties Around the Proposed Konza Techno City near Nairobi, Kenya. Critical African Studies, 9(2):210–225. doi:10.1080/21681392.2017.1323302.

- Van Wolputte, Steven, Clemens Greiner & Michael Bollig. 2022. Futuring Africa: An Introduction. In African Futures, edited by Clemens Greiner, Steven Van Wolputte and Michael Bollig, 1–16. Leiden: Brill. doi:10.1163/9789004471641_002.

- von Schnitzler, Antina. 2016. Democracy’s Infrastructure: Techno-Politics and Protest After Apartheid. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Watson, Vanessa. 2014. African Urban Fantasies: Dreams or Nightmares? Environment and Urbanization, 26(1):215–231. doi:10.1177/0956247813513705.

- Yarrow, Thomas. 2017. Remains of the Future: Rethinking the Space and Time of Ruination through the Volta Resettlement Project, Ghana. Cultural Anthropology, 32(4):566–591. doi:10.14506/ca32.4.06.