Abstract

The Financial Analysts Journal has a history of publishing academic and practitioner articles on environmental, social, and governance (ESG) issues; many appeared decades before the terminology became common. In celebration of the 75th anniversary, the author provides brief reviews of these articles, including reflections on how the insights brought out in this collective body of work remain important today for investors’ decisions.

Over the last 75 years, the Financial Analysts Journal has commonly led other finance journals in featuring articles on environmental, social, and governance (ESG) issues. These articles have been written by academics, practitioners, and the journal’s editors and always include a perspective of how these issues affect finance practice. In particular, the Financial Analysts Journal has been in the forefront with articles on the social responsibility of business and its investors; the performance of firms, investment funds, and indexes that follow ESG (or socially responsible investment [SRI]) principles; the effects of divestment; climate risk; impact investing; and the need for more ESG disclosure. Many of these topics have led to extensive debates over time, and it is notable that the journal typically presents both sides of a question so that its readers can be informed to make their own decisions. In addition, many of the points brought out in this collective body of work remain important today.

In this article, I provide a brief review of the previous Financial Analysts Journal articles in this area, including reflections on how they can provide guidance to investors today in thinking about how these issues relate to their investment decisions. What is particularly striking is that many of the articles written 40, 50, and even more than 60 years ago still have insights that apply to today’s financial markets. That is, reading the early articles provides fresh perspectives on current investments for which social impact can be large. For example, revisiting the South Africa boycott and understanding whether (and how) it made a difference can help today’s investors think through such current issues as the Sudan boycott and the fossil fuel divestment movement, as well as issues that are on the horizon, such as responses to corporate use of prisoner labor. Big social issues that intersect with investment emerge only periodically, so history can be an important reference point.

One challenge for discussions of these issues is the lack of agreement on a conceptual framework for what ESG or responsible investing means or how it should be incorporated into investment decisions. In particular, the conceptual frameworks in which financial market participants consider ESG or responsible investing issues vary not only over time but also across people contemporaneously. These variations are mostly seen across two primary dimensions. The first dimension, and arguably the more important, is whether motivation for ESG or responsible investing derives from pecuniary or nonpecuniary preferences and beliefs. As can be seen through many of the articles discussed in this review, authors vary in their assumptions on whether the issues reflect pecuniary or nonpecuniary effects. It is important to understand that investing according to ESG principles is not equivalent to investing according to SRIFootnote1 principles. The latter originated primarily because of investors’ tastes and preferences (i.e., nonpecuniary motivations), whereas ESG investing can originate from the same sources (tastes and preferences) but can also originate from a solely return/risk objective or even from both of these nonpecuniary and pecuniary motivations simultaneously. One major challenge with understanding ESG investing has been this confusion over the meaning of the concept and the source of investors’ motivations for adopting this investment approach.

The second dimension on which people differ in their conceptual frameworks for ESG investing is their beliefs regarding how investing according to these principles delivers pecuniary or nonpecuniary rewards. For example, some believe that ESG investing can deliver financial rewards through such effects as risk mitigation, return opportunities, or alpha strategies. Yet even within the group of investors who value ESG investing for its financial benefits, there can be divergence in opinions on the potential sources of those benefits.Footnote2 Similarly, there exist differences in opinions on the potential social outcomes of an ESG investment approach. In this review, I consider how these differences in beliefs may affect interpretations of the research studies.

This review contributes to the recent retrospectives on articles in the Financial Analysts Journal authored by Stephen Brown (2020) on the efficient market hypothesis and William Goetzmann (2020) on investment management.

Social Responsibility of Business and Its Institutional Investors

The general idea of the social responsibility of business has been debated for many years, and the first finance journal to publish editorials and articles about the purpose of the corporation and its social responsibility was apparently the Financial Analysts Journal.Footnote3 Current discussions of this issue center around the question of whether corporate purpose should derive from the shareholder primacy view or the stakeholder view. The shareholder primacy view is most famously reflected in the 1970 New York Times Magazine essay by Milton Friedman in which he quoted his 1962 book Capitalism and Freedom as stating, “There is one and only one social responsibility of business—to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game, which is to say, engages in open and free competition without deception or fraud’’ (Friedman 1970). Many have interpreted this quote to imply that he believed business had no social responsibility, but others point out that he makes clear that he is referring to businesses that operate in a competitive market.Footnote4

A common perspective on the shareholder primacy view is that social responsibility entails costs to shareholders, thus lowering their prospective returns. In contrast, the stakeholder perspective is that corporations are obligated to their stakeholders—that is, parties with a “stake” in the corporation’s actions, such as employees, customers, suppliers, regulators, and the community in which it operates—as well as the shareholders. Under this perspective, social responsibility incorporates how corporate managers meet the obligations to their stakeholders.

The shareholder primacy versus stakeholder perspective has come under renewed debate recently, particularly since August 2019, when the Business Roundtable (2019) changed its statement of corporate purpose to emphasize the role of stakeholders in the corporation. The revised statement includes the following:

While each of our individual companies serves its own corporate purpose, we share a fundamental commitment to all of our stakeholders. We commit to:

• Delivering value to our customers. . . .

• Investing in our employees. . . .

• Dealing fairly and ethically with our suppliers. . . .

• Supporting the communities in which we work. . . .

• Generating long-term value for shareholders, who provide the capital that allows companies to invest, grow and innovate. . . .

Each of our stakeholders is essential. We commit to deliver value to all of them, for the future success of our companies, our communities and our country.

The previous Business Roundtable statement of corporate purpose (established in 1997) emphasized the shareholder primacy concept: “The paramount duty of management and of boards of directors is to the corporation’s stockholders.” However, the previous statement also considered stakeholders as important in corporate purpose given the following excerpt: “The interests of other stakeholders are relevant as a derivative of the duty to stockholders.” Thus, the debate surrounds the question of the extent to which incorporating stakeholder interests can be compatible with maximizing shareholder wealth.Footnote5

Early articles in the Financial Analysts Journal addressed these issues. In fact, as early as 1955, discussion centered around the stakeholders. Joseph (1955, p. 72), in an article titled “The New Capitalism,” remarked, “Management is becoming increasingly aware of its responsibilities, to create profits, not only for stockholders, but also for employees, customers and the community.” A decade later, in an article titled “World Food Needs” (Freeman 1967) and in two responses to it (James 1967; Price 1967), the authors discussed the role of the American business private sector in helping solve the problem of meeting the world’s food needs. As part of this discussion, the point was made that corporate management has responsibilities to several groups, including its customers, its employees, its community, and the nation. James (1967, p. 23) noted that “more and more managements are recognizing their responsibilities to the community and the nation—and trying earnestly to live up to them.” James (1967, p. 23) went on to state, “But, beyond this, corporate management has a responsibility to its stockholders—to the thousands of men and women who have invested their money.” Price (1967, p. 25) also argued that the American investment community has joint responsibilities for both the people of less developed countries and the people whose money is being managed. These journal articles written in 1955 and 1967 also show that questions regarding the social responsibility of business were being discussed in the Financial Analysts Journal prior to Friedman’s (1970) essay and, in addition, included the question of institutional investors’ responsibilities.

The current debates regarding the social responsibility of business and corporate purpose echo many of the perspectives put forth in a 1971 Financial Analysts Journal issue in which a set of four articles appeared in a section titled “The Issues in Social Responsibility,” along with the Editorial Viewpoint article “The Institutional Investor and Social Responsibility.” The four articles in the special section were written by financial market participants with diverse perspectives—two economists, a corporate CEO, and an institutional investor—thus contributing to the debate on the social responsibility of business and the social responsibility of institutional investors. In publishing these four articles with his editorial in the same issue, William C. Norby, the Financial Analysts Journal editor, ensured that the journal would allow a full scale of views to be represented and considered by its readers.

In the Editorial Viewpoint article, Norby (1971b, p. 13) started with the following statement: “A year ago many of us were wondering whether the idea of ‘Social Responsibility in Business’ had already reached full bloom and would soon fade away in the continuing parade of social ideas and fads. Today it is clear that the idea has considerable staying power.” In this article, which appeared a year after Friedman’s (1970) essay, the author emphasized that institutional investors should anticipate social problems that corporations are not currently facing, along with the future costs of these problems and the impact of corporate decisions, whether with regard to social issues or other issues. He went on to stress that investors should communicate with management directly rather than through the proxy proposal process; that is, in today’s terminology, he argued for investors to engage corporate management to generate change. Finally, although he did not use the term externalities, Norby (1971b, p. 13) referred to the externalities that businesses impose on each other in that he argued, “In a competitive economy, the best way to assess responsibility for the social costs of business is through legislation and government regulation, so that all companies bear some of the costs.”

In “Standards of Corporate Responsibility Are Changing,” Gray (1971) provided the view of a business economist and management consultant. He argued that because businesses are agencies of the societies in which they exist, they have social responsibilities as well as rights, and he asserted that these responsibilities have been evolving. His arguments basically included the idea that because of externalities, corporations and their shareholders have an interest in the system as a whole rather than the individual corporation. For example, “It is arguable that a corporation that does not accept new social responsibilities for environmental protection, fair employment practices, or creating consumer approval of business conduct, is acting against the interests of the dominant, multi-shareholder, system-investing group” (Gray 1971, p. 29). In addition, he stated that corporations have more than one legitimate constituency whose interests should be considered and that stockholders need “the freely given consent and participation of employees, whose investment in the firm is relatively greater than anyone else’s” (Gray 1971, p. 73). He also argued for consideration of consumers, suggesting that the “whole economic system is predicated on consumer sovereignty” (Gray 1971, p. 73). Thus, he provided basic arguments consistent with the stakeholder view, many of which are from a pecuniary perspective.

Providing the opinion of an academic economist in “The Free-Market System Is the Best Guide for Corporate Decisions,” Heyne (1971) argued against businesses and institutional investors having “social responsibilities.” In the first paragraph of the article, he referred to “the ambiguities, misconceptions, wishful thinking and elitism wrapped up in the doctrine of corporate social responsibilities” (p. 26) and argued that these are multiplied when one considers institutional investors to “have a social responsibility to make corporations socially responsible” (p. 26). He argued, as others argued almost 50 years later, that people in business do not “have a better grasp of the public interest than do other citizens. The economic system is not a playground on which businessmen may exercise their peculiar preferences” (p. 26). Heyne’s arguments suggest that he viewed corporate social responsibilities as reflections of nonpecuniary preferences on the part of those who advocate for businesses to engage in those responsibilities, an argument that is broadly used today as well.

Similarly, taking the conceptual foundation of social responsibility as arising from nonpecuniary preferences and beliefs in the article “The Professional Investor’s View of Social Responsibility,” Hall (1971) argued against investors making decisions based on social responsibility issues that are nonpecuniary. He maintained that because of their legal position, investment fiduciaries face limitations in their consideration of corporate social responsibility in their portfolio decisions. That is, because statutory or case law requiring the fiduciary to consider social responsibility in these decisions does not exist but a legal obligation to put the beneficiary’s interests first does exist, he believes the fiduciary can consider social responsibility issues only in terms of their investment implications. This is the same perspective asserted last year by the US Department of Labor (DOL) with regard to retirement fiduciaries operating subject to the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA). The DOL proposed an amendment in June 2020, in which they specifically highlighted the environmental, social, and governance terms. For example, in a subsection regarding the rules and regulations for fiduciary responsibility titled “Consideration of Pecuniary vs. Non-Pecuniary Factors,” the proposed rule stated,

Environmental, social, corporate governance, or other similarly oriented considerations are pecuniary factors only if they present economic risks or opportunities that qualified investment professionals would treat as material economic considerations under generally accepted investment theories. The weight given to those factors should appropriately reflect a prudent assessment of their impact on risk and return. Fiduciaries considering environmental, social, corporate governance, or other similarly oriented factors as pecuniary factors are also required to examine the level of diversification, degree of liquidity, and the potential risk-return in comparison with other available alternative investments that would play a similar role in their plans’ portfolios.Footnote6

The proposal generated considerable public debate regarding the role of ESG issues in retirement fund investment decisions and garnered over 8,600 comment letters, 95% of which were opposed to the new regulation. The vast majority of the commenters were individuals. In the 229 comment letters from investment-related groups (e.g., asset managers, financial advisers, asset owners), there was also considerable opposition, as 94% were opposed to the rule. Among the key themes identified in an analysis of the comment letters were the arguments that the DOL provided no evidence that investments selected on the basis of ESG criteria would be likely to have lower returns; that the DOL proposal dismissed the financial materiality of ESG issues, ignoring research regarding such materiality; and that the proposal was based on a flawed “assumption that ESG funds give up financial returns in favor of ‘non-pecuniary’ rewards” (Gorte, Hale, McGannon, Dyer, Gridley, Rees, and Zinner 2020, p. 6).

In issuing the final rule amendment in October 2020, the DOL omitted any specific reference to ESG issues, requiring that plan fiduciaries “select investments and investment courses of action based solely on financial considerations relevant to the risk-adjusted economic value of a particular investment or investment course of action.”Footnote7 Thus, some 50 years after the Hall (1971) article, arguments consistent with his are still being made. Further, these arguments will most likely continue to be debated given that the Biden administration plans to reconsider the recent DOL amendment (Quinson 2021).

In the fourth article in the group, “The Corporation Executive’s View of Social Responsibility,” Thorton F. Bradshaw (1971), then CEO of Atlantic Richfield, delivered somewhat contrasting views. His views of the role of the corporation were often in line with what are commonly considered core tenets of corporate social responsibility. For example, he stated that businesses must be good neighbors in the communities in which they operate and that businesses should experiment with new solutions to social problems. Bradshaw (1971, p. 71) also stated that “some day businessmen will be judged on how well they achieve social goals as well as profit goals. Some day all products will be costed to reflect full social costs.” These statements are similar to the 2018 letter that Larry Fink, CEO of BlackRock, sent to the CEOs of underlying portfolio firms, in which he stated, “Society is demanding that companies, both public and private, serve a social purpose. To prosper over time, every company must not only deliver financial performance, but also show how it makes a positive contribution to society.”

Bradshaw (1971) also discussed a topic of significant interest today, racial diversity, again putting the Financial Analysts Journal on the forefront of these issues. Some of the management actions that he reported are noteworthy considering the fact that five decades ago, he was trying to make a difference to improve racial diversity in his company. For example, under his leadership, the management team designed a new hiring rule: If two people, both equal in capability, applied for a job but one was white and one was Black, the Black individual was to be hired. He also initiated a program to ensure that the entire company would have a more diversified employee base. With respect to gender diversity, Bradshaw (1971, p. 70) stated, “Regarding Women’s Lib, we have in our company a lady whose sole task is auditing our personnel policies and practices and making suggestions and recommendations so that women in our company get an even break.”

The Financial Analysts Journal has more recently published an article that is also relevant to the question of the social responsibility of business and capitalism. In “Capitalism and Financial Innovation,” Shiller (2013) pointed out that financial innovations help in achieving society’s goals. He specifically pointed out three financial innovations that have contributed to a positive and lasting impact on these goals: the benefit corporation, crowdfunding, and the social impact bond. Again, the Financial Analysts Journal was leading in discussing these social innovations and their connection to capitalism.

Short-Termism and Institutional Investors

A related issue that was brought up in the journal in 1971 and is still being debated today is the question of investors’ and management’s time horizons—specifically, the question of short-termism. The journal’s editor published an Editorial Viewpoint on the responsibility of business (Norby 1971a), and the article’s emphasis on the investor’s time horizon corresponds to present-day discussions about long-term considerations. The last lines state,

For investment management, the starting point would seem to be the fiduciary concept in the management of other people’s money. The concept implies a concern for conservation of capital as well as its appreciation, and is implemented by adoption of a time horizon for investment funds that is appropriate to the real objectives of the ultimate beneficiary and by careful selection of securities. (Norby 1971a, p. 7)

Many years later in the Guest Editorial “A New Era of Fiduciary Capitalism? Let’s Hope So,” Rogers (2014) reflected on the global financial crisis and the need for fiduciary capitalism from universal owners, long-term-oriented institutional investors, who would affect the general behavior of the financial markets and broader economy. His beliefs were close to those of Norby (1971a) from 43 years earlier:

As universal owners, large fiduciaries recognize that they are owners for the long term, which should suit businesses looking for more stability and consistency from their shareholders. . . . Under fiduciary capitalism, these corporate management teams will have longer-term owners of their shares, who will hold them accountable for long-term performance and for the true environmental and social costs of their activities. (Rogers 2014, p. 9)

Rogers (2014) argued that the universal owners through their fiduciary capitalism would engage with corporate management and public policymakers. In so doing, they would seek to minimize negative externalities and reward positive ones.

The relationship between responsible investing and long-term ownership has also been developed conceptually by Bénabou and Tirole (2010, p. 10), who argued that because corporate social responsibility involves taking “a long-term perspective to maximizing (intertemporal) profits . . . socially responsible investors should position themselves as long-term investors who monitor management and exert voice to correct short-termism.”Footnote8

Similar to the Rogers (2014) and Bénabou and Tirole (2010) arguments regarding the role of long-term investors in shareholder engagement, an important aspect of some institutional investors’ approaches to socially responsible issues is the use of shareholder activism/shareholder engagement to achieve environmental, social, and governance goals for the underlying portfolio companies. Beyond the editorial comments by Norby (1971b) on the role of the institutional investor in engaging corporate management on social and other issues, the Financial Analysts Journal was also early in providing information on and consideration of shareholder activists’ goals. Two of the earliest shareholder activists were the Gilbert brothers, Lewis D. and John J. Gilbert, who began their crusade to reform governance at corporations before World War II. In a short article, “The Gilbert Brothers—Gadflys or Eagles?,” Kahn (1971) provided a description of the brothers’ reform activities, including their attendance at more than 183 annual meetings a year, speeches at different organizations about their activities, and testimony for the SEC and state legislative bodies. Some of the Gilbert brothers’ objectives coincide with those of today’s shareholder activists, such as more informative annual reports, director ownership in firm stock, and reasonable watch over executive salaries, options, and pensions.

ESG Investing, Socially Responsible Investing, and Financial Performance

As mentioned earlier, the Financial Analysts Journal tends to provide alternative perspectives for topics that are highly debated. For example, Schotland (1980) argued that rather than being called socially responsible investing, such investment strategies should be termed “divergent investing for pension funds,” because no one would talk about antisocial or anti-responsible investing. He also discussed the practical problems of implementing such investment strategies, as well as the fiduciary issues. Schotland (1980, p. 37) argued that shareholder activism is a better approach and that, in contrast, divergent investing is “unproductive investing and unproductive social action.”

This perspective that responsible investing is costly leads to the much-debated question of whether social responsibility considerations in corporate decisions and investment decisions enhance portfolio performance or serve as a cost to performance. Again, the Financial Analysts Journal was the first finance journal to provide an analysis focused on the performance of socially responsible funds: The earliest such publication I could find was Hamilton, Jo, and Statman’s (1993) article in the journal, “Doing Well While Doing Good? The Investment Performance of Socially Responsible Mutual Funds,” in which the authors examined the returns of socially responsible mutual funds as compared with conventional alternatives.Footnote9 The authors developed three hypotheses regarding the differences between these sets of returns. The first hypothesis held that no difference should exist between the returns, because social responsibility does not affect the risk of a firm and, therefore, should not be priced. The second hypothesis considered the demand by socially responsible investors, which, in increasing the price of the underlying firms, lowered the subsequent returns, thus imposing a cost to investing in SRI funds. That is, because of their demand for socially responsible stocks, these investors drove down the expected returns and cost of capital of the socially responsible companies, causing the SRI mutual funds to underperform relative to conventional mutual funds. Finally, under the authors’ third hypothesis, SRI funds outperformed conventional funds because investors underestimated the probability of negative events from the companies not considered socially responsible. (These could be called “ESG controversies” in today’s terminology.) During the authors’ sample period (1981–1990), SRI funds were uncommon and those that did exist did not have a long track record. The authors’ sample included six mutual funds as of 1981 and increased to 32 funds by the end of 1990. Using Jensen’s alpha as the measure of performance in their tests, Hamilton et al. (1993, p. 66) found no statistical difference between the returns of the SRI funds and the returns of the conventional funds, concluding that “investors can expect to lose nothing by investing in socially responsible funds.”

Statman (2000) followed this analysis in another Financial Analysts Journal article, in which he again examined the performance of socially responsible mutual funds against the performance of conventional mutual funds by matching 31 socially responsible funds to a set of 62 conventional funds using assets under management as the key matching variable.Footnote10 He found that although both sets of funds exhibited negative alphas over the sample period, there was no statistically significant difference in their return performances. Statman also expanded the analysis by examining the performance of the Domini Social Index (now known as the MSCI KLD Social Index) against three alternatives: the S&P 500 Index, an index constructed of socially responsible companies, and a portfolio of socially responsible mutual funds in the 1990–98 period. He found no significant differences in the performance of these indexes and again concluded that investing for something other than making money is no worse than conventional investing.

Nine years later in another Financial Analysts Journal article, Statman and Glushkov (2009) pointed out that a better test of SRI performance would come from examining the performance of the underlying firms rather than the mutual funds because the returns on the mutual funds would be confounded by managerial skills and fund expenses. Thus, the authors formed portfolios of firms based on industry-adjusted KLD ESG scores and measured the performance of the highest best-in-class firms against the lowest best-in-class firms.Footnote11 The authors measured firm performance using the CAPM, three-factor model, and four-factor model as benchmarks and divided the firms by their scores on the individual ESG characteristics. They also conducted an analysis of long–short portfolios, constructed to be long the highest best-in-class firms and short the lowest best-in-class firms. The authors found significant outperformance of top-rated firms over bottom-rated firms. They also constructed a long–short portfolio in which they shorted “shunned” stocks, which they defined as companies associated with alcohol, tobacco, gambling, firearms, military, or nuclear operations. Consistent with the results of a contemporaneous paper on sin stocks versus other stocks by Hong and Kacperczyk (2009), Statman and Glushkov found that the shunned stocks outperformed other stocks.Footnote12 These results were obtained using equally weighted portfolios. When the authors used value-weighted portfolios, the results were much weaker. Also, when comparing an index of socially responsible firms with the S&P 500, the authors did not find a significant difference in returns. They concluded that the advantage from the social responsibility tilt was largely offset by the exclusion of the shunned stocks, thus consistent with their “no effect” hypothesis.

A more focused analysis of an SRI objective was conducted in one of the most highly cited articles in this survey, “The Eco-Efficiency Premium Puzzle,” in which Derwall, Guenster, Bauer, and Koedijk (2005) focused on firms’ environmental performance. Derwall et al. (2005, p. 51) developed a concept they termed “eco-efficiency,” which they described as “the economic value a company creates relative to the waste it generates.” Using the Innovest Strategic Value Advisors rating database for measuring the environmental performance of the funds, the authors argued that in order to examine differences in return performance, they needed to use the Fama–French–Carhart model to control for style tilts in size, growth, and momentum, because the firms with the highest environmental performance tend to be large growth stocks. The authors’ evidence indicated that companies that perform better along environmental dimensions, on average, earn superior risk-adjusted returns. Examining differences between portfolios of environmental relative outperformers and underperformers and controlling for risk, style, and industry, they found that the average returns on the differences were economically large and statistically significant. The authors concluded that for large-cap companies, the most eco-efficient companies significantly outperformed a less eco-efficient portfolio when measured over their 1995–2003 sample period. Their findings imply that environmentally responsible investing provides both societal and financial benefits.

Again, the Derwall et al. (2005) study showed that Financial Analysts Journal articles reflect evolving, contemporaneous thinking, as the idea of eco-efficiency can be related to the concept of a circular economy, used widely today to describe an economy in which waste is minimized because manufactured products and their materials are reused and repaired or redistributed.Footnote13

An important issue that should be addressed in measuring performance differences between ESG or responsible investing funds and conventional funds is that substantial differences exist across the investment objectives of funds because of variations in investor preferences and beliefs. Some investors have diverse objectives owing to their particular nonpecuniary preferences, such as peace values, religious values, environmental values, or animal rights values, which may be paired with pecuniary preferences. By aggregating fund returns across such diverse objectives to determine how the responsible investing funds differ from other types of funds, we do not get a complete picture of performance. Derwall et al. (2005) addressed this issue by focusing on the environmental performance of funds or firms, but their samples included mixed sets of funds or firms. Statman and Glushkov (2016) addressed this issue in part by pointing out the range of social responsibility across funds. They developed a six-factor model that includes the traditional size, market, value, and momentum factors and adds two social responsibility factors. The first measures the extent to which a fund tilts toward responsible investing by using the difference between the returns of stocks of companies ranked in the top third and the bottom third by five social responsibility criteria: employee relations, community relations, environmental protection, diversity, and products. The second factor is designed to capture the differences in returns due to screening because of undesirable or shunned company investments related to their business in the alcohol, tobacco, gambling, firearms, military, or nuclear industries. The results suggested that future analysis might provide more insights by examining responsible investing funds on a more focused basis. This is particularly important given that many funds are now ESG funds, often having mixed mandates that include both pecuniary and nonpecuniary goals.

Similarly, in more recent work, Brière, Peillex, and Ureche-Rangau (2017) provided a focused analysis of responsible investing fund performance by addressing the potential differences in performance between SRI and conventional mutual funds through an examination of how screening choices affect performance. Using a sample of 284 SRI equity mutual funds over the 2004–15 sample period, the authors decomposed the returns into those arising from market returns, allocation, active management, and socially responsible screening. They found that screening choices had relatively modest effects on the performance variability between the responsible investing funds, in aggregate, and conventional funds and that these effects were about two times smaller than the effects that derived from managers’ active portfolio selections. However, in cross-sectional analyses, they found large differences across the responsible investing funds in terms of the contributions to performance from the screening choices. While a quarter of the sample funds had a contribution from the socially responsibility screening of less than 1% (which they argued could be due to misclassification), the authors found that several funds had a large contribution from screening that exceeded 14%. They also found that the contributions from social responsibility screening differed geographically, being smallest for US funds and highest for global funds.

Khan (2019) explored the relationship between future returns and a new measure of ESG, based on a framework of ESG materiality developed by Khan, Serafeim, and Yoon (2016). Using a global sample of firms, he concluded that the new measure of ESG is associated with future stock returns but also pointed out the caveats to his analysis. Serafeim (2020) took a different, but complementary, approach to exploring relationships between firms’ ESG activities and market valuations of those activities. He concluded that public sentiments toward firms’ sustainability activities can be important in investors’ valuations of the firms.

In summary, the journal’s articles on fund and firm performance with regard to specialized ESG or socially responsible objectives have provided informative analyses regarding the performance of the funds and firms. These analyses correspond to analyses in other finance journals that examined these issues, but given the differences in objectives across the investors, we do not have a complete picture of whether and how these issues have causal effects on performance. For example, recent examinations of the performance and flows of ESG funds and firms during the COVID-19 pandemic have come to mixed conclusions (e.g., Albuquerque, Koskinen, Yang, and Zhang 2020; Döttling and Kim 2021; Capelle-Blancard, Desroziers, and Zerbib 2021).

Divestment

The ultimate screening choice is to divest from companies that are objectionable. Statman (2000) discussed the effects of divestment and provided a conceptual analysis of the differences between investment actions (by withholding capital) and political actions (by getting the government involved). Using tobacco companies as an example, he pointed out that investment actions have difficulty resulting in change because socially responsible investors’ actions can increase a shunned firm’s cost of capital only if the capital supply function is less than perfectly elastic; that is, there must be an absence of sufficient numbers of other investors who are willing to provide that capital. However, as he further asserted, although the capital supply may not be perfectly elastic, it “is probably very elastic.” He argued that the investment actions by themselves are more likely to effect change by serving as banners for subsequent political actions.

The question of whether to divest portfolios of companies that are considered to produce products or engage in behaviors that are unacceptable to the investor has been an investment issue for many years. The Financial Analysts Journal again was in the forefront of addressing ESG issues by publishing articles considering divestment and its effects.Footnote14 Just as today there are pressures on pension funds, university endowments, and foundations to divest their portfolios of fossil fuel companies or private-prison companies, during the 1980s, there were pressures to divest of US companies doing business in South Africa without committing to following the Sullivan Principles, which provided standards for companies operating in South Africa.Footnote15 The Financial Analysts Journal had a series of articles from late 1984 through the summer of 1986 that addressed South African divestment issues.

In “South African Divestment: Social Responsibility or Fiduciary Folly?,” Ennis and Parkhill (1986) provided a thoughtful analysis of the issues involved in the divestment decision, particularly for those asset owners that had political or social exposures, such as public pension funds, college endowments, and foundations. Some of these asset owners had no choice regarding divestment because of US state and municipal legislation that prohibited certain South African investments. The authors discussed issues that are also relevant to questions today, such as the effectiveness of divestment as a social strategy; the portfolio implications of divestment, including costs and effects on portfolio risks; and legal, personal liability, and ethical issues.

As pointed out by Ennis and Parkhill (1986), the idea behind the divestment approach was to withdraw capital in order to pressure companies to bring about change in the South African apartheid system. Beyond the question of whether to divest was the question of which companies to divest: all US companies with any business in South Africa or only the ones that were not trying to change the system from within—that is, those that were not following the Sullivan Principles. This situation can be compared with the decision of asset owners today as to whether to divest of all fossil fuel companies or only companies representing the worst cases of corporate conduct involving negative effects to the environment with regard to climate change.

An important question that is often asked regarding divestment—either to avoid complicity in owning an undesirable product or behavior or to pressure firms into changing their products or behavior—is the cost to the institutional investor’s returns from such a decision. Again, the Financial Analysts Journal was in the forefront by publishing articles that addressed the question regarding South African divestment, including an article with a fable comparing a portfolio without the divested stocks with a cow that has been hit by a car and thus altered, with about 25% of her parts (opportunities for trading profits) missing. In this article, Regan and Love (1985) pointed out that 27 of the top 50 stocks in the S&P 500 Index would be eliminated and that some industries would be mostly gone in terms of their market value, including 99% of industrial equipment, 97% of banks, 87% of chemicals and drugs, 81% of motor vehicles, and 76% of international oils.

While some earlier work had argued that divestment would not be particularly restrictive or important, the articles published in the Financial Analysts Journal more thoroughly considered the issues. The US companies with operations in South Africa were not a small group. Ennis and Parkhill (1986) found that 166 of the S&P 500 companies had business in South Africa, representing 52% of the index’s market capitalization. Moreover, these companies also represented a substantial portion of the A rated (or better) corporate bond market as they issued about one-third of these bonds. However, for most of the companies, the South African part of their business was small, with a limited presence in South Africa. As of 1983, only 3% of South Africa’s industrial plants were operated by US companies.

In “South African Divestment: The Investment Issues,” Wagner, Emkin, and Dixon (1984) examined how divestment of the South African–related companies in the S&P 500, if each one were replaced by the largest other company in the same industry, would affect the portfolio’s characteristics. The replacement portfolio would have 8% more risk (as measured by beta) and 3% less diversification. The authors also calculated that the portfolio would have higher trading and administrative costs because the portfolio constituents would be smaller, riskier, and less liquid.

In “Financial Implications of South African Divestment,” Grossman and Sharpe (1986) took a different approach and constructed a representative divestment portfolio consisting of a value-weighted portfolio of all South African–free (SAF) stocks traded on the NYSE in order to maintain a buy-and-hold strategy and minimize trading costs. They first examined the divestment costs—that is, transitioning from a value-weighted portfolio of all NYSE stocks to a value-weighted portfolio of all SAF NYSE stocks. They concluded that the transaction costs of divestment, while nontrivial, would be less than had been previously estimated, about 50 bps. However, the SAF portfolio would be more concentrated in smaller-capitalization stocks than the full NYSE portfolio, and the authors demonstrated that if the small stock effect persisted, the SAF portfolio would have a slightly higher expected return for the same risk but with considerably less liquidity. Grossman and Sharpe also calculated that if the divestment were applied only to the companies that were noncompliant with the Sullivan Principles, the divestment would involve only about 7.1% of the total value of the NYSE and would thus have only minor effects on the portfolio.

The Financial Analysts Journal articles on divestment provide a range of views, as is typical of the journal’s approach to controversial issues, and include a featured article on the ethics of divestment. In “Ethics in Investment: Divestment,” Hall (1986, p. 7) asked three basic questions: “Is consideration of ethics in investment and divestment principled? Is it practical? Is it prudent?” These are the same basic issues that are being considered today in terms of divestment criteria with respect to climate change. Hall (1986, p. 7) maintained that the motivations behind ethical investment are highly principled but that these objectives that “appear unambiguous in the abstract can turn controversial when considered in the light of the complex and often conflicting demands of real-life implementation.” He then discussed the issues faced by corporate and public pension funds and endowment funds in determining whether they should divest firms according to nonpecuniary rationales. After considering the issues, he stated his opinion: Divestment in such circumstances would be unprincipled, impractical, and imprudent.

As a group, these articles bring up the important aspects of the divestment question: whether divestment is effective in achieving the desired social goals; the portfolio effects from a divestment decision, including costs and changes in portfolio diversification and risk; and the legal, liability, and ethical issues. In work subsequent to these articles, Teoh, Welch, and Wazzan (1999) examined the South African divestment movement and concluded that there were no direct effects from the movement on the affected firms’ share prices, their cost of capital, or the South African financial markets, which brings up the question of whether a divestment movement can be successful in achieving its underlying goal. Davies and Van Wesep (2018) approached this question from a theoretical perspective by examining for a very large divestment campaign whether the firms’ managers’ compensation incentives would cause them to respond to the campaign. They concluded that because divestment campaigns affect short-term stock prices rather than longer-term stock prices, profitability, or stock returns, typical managers’ compensation structures would not provide incentives to respond to the campaigns. The authors speculated that social pressures could have greater effects than financial pressures through divestment. This argument is consistent with that of Statman (2000), presented at the beginning of this section: Investment actions serve better as banners for subsequent political actions.

Divestment and Environmental and Climate Risk

The mid-1980s Financial Analysts Journal articles on divestment issues centered on whether to hold South Africa–free portfolios. More recently, with respect to divestment issues, the interest has centered on whether to hold carbon-free portfolios on account of climate change considerations.Footnote16 Again, the Financial Analysts Journal was at the forefront of finance journals in bringing these issues into conceptual, empirical, and practical consideration. In the Editor’s Corner article “Pricing Climate Change Risk Appropriately,” Litterman (2011) presented an argument that climate risk was not being properly priced—in fact, that it was not being priced at all—and that the risk premium should reflect both known and unknown risks given the fundamental uncertainty about catastrophic risks and the high level of societal risk aversion. He further argued that investor portfolios should be tilting away from companies more subject to climate risk because governments would be taking actions to limit harmful emissions.

In the Editor’s Corner article “David Swensen on the Fossil Fuel Divestment Debate,” Litterman (2015) discussed the fossil fuel divestment issue, providing examples of how some endowments, foundations, and pension funds had been handling the decision. He then referred to the Yale University endowment’s decision not to divest and cited the letter that David Swensen, the chief investment officer of the Yale University endowment, wrote to Yale’s external investment managers. In this letter, Swensen pointed out the risks imposed by climate change and asked that in their investment decisions, the external managers assess an investment’s greenhouse gas footprint and how the direct costs resulting from climate change and the costs from regulatory policies would affect expected returns. Swensen’s letter specifically addressed both engagement and divestment issues through an expectation that the portfolio managers would engage with corporate managers on climate risk and by advising that “Yale asks you to avoid companies that refuse to acknowledge the social and financial costs of climate change and that fail to take economically sensible steps to reduce greenhouse gas emissions” (Litterman 2015, p. 12). Swensen’s letter ended with the following admonition regarding climate risk:

Analyzing the greenhouse gas emissions associated with investments is far from simple and fraught with challenges. As in all aspects of investment analysis, decisions will be based on incomplete, imperfect information. That said, consideration of the risks associated with climate change should produce higher-quality portfolios. (Litterman 2015, p. 12)

In terms of further environmental considerations in investment decisions, the Financial Analysts Journal also brought these issues into context for its readers during early periods, pointing out again the problems with externalities. For example, in 1973, the issue of business and environmental costs was addressed in the article “The Limits of Traditional Economics: New Models for Managing a ‘Steady State Economy.’” In it, Henderson (1973) argued that the full social and environmental costs are not always charged to producers. Moreover, she expressed concerns regarding whether the prevailing economic systems could prevent the industrial growth that was occurring in both developed and developing economies from resulting in ecological harm. This perspective on economic growth and the environment was also debated in 2012 and 2013 in the Financial Analysts Journal (see Siegel 2012; Bernstein 2013).

The Financial Analysts Journal also published a 2016 issue in which climate risk was highlighted in articles on hedging climate risk in equity portfolios and in fixed-income portfolios combined with an editorial perspective. In the Editor’s Corner article “Climate Risk,” Brown (2016) pointed out the differences between viewing the effects of climate change as an opportunity and focusing on the harm that can arise from climate change. Opportunities come from the increasing availability of green energy investments. Alternatively, he pointed out that another approach to climate risk would be to divest carbon-intensive assets from one’s portfolio and to then construct the remaining portfolio in such a way that it mimics its benchmark. Brown (2016, p. 9) noted that this approach is possible only because “carbon footprint securities are small in magnitude and are relatively concentrated in most portfolios.” Thus, one can limit the financial risk that develops from exposure to stranded assets. In the article “Hedging Climate Risk,” Andersson, Bolton, and Samama (2016) considered the climate risk embedded in equity portfolios and provided a dynamic index investment strategy for holding a carbon-free portfolio. In “Weathered for Climate Risk: A Bond Investment Proposition,” de Jong and Nguyen (2016) discussed techniques for hedging against climate risk in a fixed-income portfolio.

Climate risk has been shown to be a prime concern for institutional investors (e.g., Krueger, Sautner, and Starks 2020). As investors have considered how to incorporate climate risk into their investment decisions, the analyses in the journal have helped investors more fully understand the issues with climate risk.

Impact Investing

“Impact investing” has gained significance since 2007, when the term was first developed by the Rockefeller Foundation to signify “investors seeking to generate both financial return and social and/or environmental value—while at a minimum returning capital, and, in many cases, offering market rate returns or better” (E.T. Jackson and Associates Ltd. 2012, p. 1). Although what constitutes impact investing and the boundaries between the impact investing market, the SRI market, and the ESG market are not well defined, most people believe impact investments should deliver both financial returns and intentional social returns (where the term “social” includes both social impacts and environmental impacts).

The settings of the boundaries between impact investing, SRI investing, and ESG investing are important when one considers the expected returns across these types of investment approaches. For example, one impact investor may be willing to accept the prospect of receiving only the return of the capital they have invested, which is a very different requirement from expecting a return that is lower than a market-adjusted rate of return and even more different from expecting a return that is equal to a market-adjusted rate. Differences also exist in whether investors try to achieve the dual goals of financial and social returns through public markets or through private markets. Using random utility/willingness-to-pay models with private equity fund data, Barber, Morse, and Yasuda (2021) found that investors are willing to accept expected returns in their impact investing that are 2.5–3.7 percentage points lower than market returns, depending on the investor.

In “Impact Investing: Killing Two Birds with One Stone?,” Caseau and Grolleau (2020) brought up a challenge regarding individuals’ perceptions about impact investing—that some investors have biases preventing them from believing that impact investing can achieve both financial returns and social returns. The authors stressed that they do not question whether impact investing can achieve success, but rather they discussed why individuals have the perception that success in both areas simultaneously is doubtful. The authors presented three mechanisms for the subconscious biases that individuals may have. The first is a “goal dilution bias,” an effect in which the “more goals the action claims to meet, the less individuals believe that any goal will be successfully accomplished” (Caseau and Grolleau 2020, p. 42). The second mechanism is the “zero-sum heuristic,” which the authors defined for these purposes as the tendency of investors to judge intuitively that if money is invested in one dimension to produce social impact, it will be matched with an equivalent loss of money for the other dimension (financial return), “even if the objective situation is not actually a zero-sum condition” (Caseau and Grolleau 2020, p. 44). The third mechanism is the “presenter’s paradox,” which pertains to the situation in which adding an extra argument will actually weaken the presenter’s proposition. As the authors described, the application of the presenter’s paradox to the impact investing pitch goes as follows: The potential impact investors, who are expecting to receive financial returns, will be less likely to be persuaded to invest after they receive a message that contains both strong and weak arguments as compared with a message that contains the stronger arguments alone.

Using insights from the psychology literature, Caseau and Grolleau (2020) provided suggestions as to how an adviser might counter these mechanisms, such as, depending on the investor, prioritizing one of the goals over the other, reducing the perceptions regarding conflicts between the goals, helping the investor perceive progress toward one goal, and distinguishing information appeals from emotional appeals. They also provided strategies to debias individuals or nudge them away from biases, such as reminding investors that they may have subconscious biases, enhancing information presentation, and framing.

ESG Disclosure

In order for investors to be able to measure the ESG profile and activities of a firm, they need sufficient information about the firm on a number of dimensions. Investors are demanding such information, and many companies are complying. For example, in 2019, 90% of S&P 500 firms issued sustainability reports, as compared with the 20% that did so in 2011.Footnote17 However, these sustainability reports vary quite a bit in their disclosures, resulting in dissatisfaction among many investors who believe that the amount of information being disclosed is insufficient. A contemporary debate surrounds the issue of how much companies should disclose with regard to their ESG profiles and activities.

Again, the Financial Analysts Journal was early in its considerations of these issues. For example, Norby and Stone (1972) discussed what should be included in financial reports, but they also anticipated the idea of companies’ publishing social responsibility reports. In their article, they included a section titled “Social Costs,” in which they pointed out that corporate social responsibility was not clearly defined and that while some investors were including it in their investment decisions, it was not “an important factor in the aggregate” (Norby and Stone 1972, p. 79). They argued that a “social report” should not be included with financial statements because financial statements warrant only the inclusion of economic costs. If a company’s social programs had economic costs, then those would be reflected in the financial statements and perhaps footnoted. Norby and Stone (1972, p. 79) finished this section with the statement, “Let investors make their own judgment and let law and regulation assume responsibility for equalizing social costs.”

The Financial Analysts Journal also contributed to this debate through Amel-Zadeh and Serafeim’s (2018) survey of 400 institutional investors regarding how and why they use ESG information. The authors found that pecuniary motivations were quite high, given that the major rationale for why investors use ESG information is its perceived financial materiality for the expected performance of their portfolios. However, the authors also found that nonpecuniary motivations were high, given that 41% of the European institutional investors surveyed used ESG information because they saw it as an ethical responsibility. There were wide differences on this perspective, as only 19% of the US respondents viewed using ESG information as an ethical responsibility. Further, the use of ESG information in making investment decisions for over 50% of the investors derived from client and stakeholder demand. The biggest concerns the investors reported regarding ESG information derived from lack of comparability across firms, lack of standards, lack of reliability, and lack of quantifiable ESG information.

These results share similarities with those of Ilhan, Krueger, Sautner, and Starks (2021) regarding institutional investor preferences for disclosure of climate risks. In a survey of over 400 institutional investors on these disclosures, Ilhan et al. (2021) found that investors also were highly concerned about the lack of information with regard to climate risk, particularly emission disclosures. This result is important because many of the institutional investor respondents considered climate risk reporting to be as important as financial reporting. The authors pointed out that despite considerable pressure from both investors and regulatory bodies for increased climate-related disclosures, the lack of more voluntary disclosure suggests the existence of costs to such disclosures. Further, differentiating between investors concerned about pecuniary and nonpecuniary effects of climate risk showed that those investors who were especially concerned about the financial effects of climate risk thought that climate risk reporting should be mandatory and standardized, suggesting that these investors believed that the benefits of this disclosure outweigh the costs, which conforms to theoretical predictions about disclosures in Goldstein and Yang (2017) and Christensen, Hail, and Leuz (2019).

Organizations are developing frameworks for standardized ESG disclosures. The World Economic Forum, in collaboration with the International Business Council, Deloitte, EY, KPMG, and PwC, has developed metrics for reporting organized into four pillars: governance, planet, people, and prosperity. These pillars are aligned with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (see World Economic Forum 2020). In addition, five of the global organizations that have been working on corporate disclosure of sustainability measures have announced that they are working together: CDP, the Climate Disclosure Standards Board (CDSB), the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC), and the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) are working toward a shared vision of an integrated reporting framework that includes both financial accounting and sustainability disclosures (CDP, CDSB, GRI, IIRC, and SASB 2020).Footnote18 These collaborations, along with regulators’ work on further reporting, suggest a number of forthcoming innovations.

Conclusion

As can be seen through the articles published in the Financial Analysts Journal for more than 60 years, environmental, social, and governance issues have been topics of much interest and have also generated considerable debate. Importantly, investor interest in these issues has heightened and debate has increased. Many of the points and much of the empirical evidence that were published earlier still have relevance to the topics today. For example, debate on the performance effects of incorporating nonpecuniary preferences into investment decisions has remained front and center.

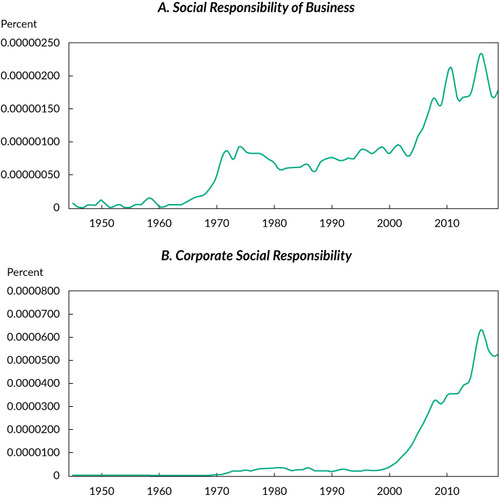

One example of how the Financial Analysts Journal has contributed to and been in the forefront of discussion of these important topics is shown in the usage of the phrases “social responsibility of business” and “corporate social responsibility” over time. As the Google Books Ngram Viewer graph in Panel A of shows, there appears to have been markedly increased relative usage of the phrase “social responsibility of business” in the years just prior to Friedman’s (1970) essay. As the graph further shows, the phrase has been in increased relative usage over time. It can be seen from the graph in Panel B of that the phrase “corporate social responsibility” took off in usage about the time of the Friedman (1970) essay and the 1971 special section in the journal. Moreover, as the magnitudes on the y-axis indicate, “corporate social responsibility” has become relatively more common in books than “social responsibility of business.”Footnote19

These graphs also show how increasingly common these phrases have become over time, suggesting that the idea that corporations have some social responsibility is now embedded in our culture. Further, the increasing focus on ESG issues by investors and corporations is consistent with this argument. The Financial Analysts Journal has been informing and educating market participants for over 60 years on these topics and continues to do so.

Declaration of Interests

Disclosure: The author reports no conflicts of interest.

Submitted 5 May 2021

Accepted 18 June 2021 by William N. Goetzmann

Notes

1 The initialism “SRI” more commonly today refers to sustainable and responsible investing rather than socially responsible investing. Because the articles in the journal refer to socially responsible investing, I have used that terminology.

2 In a review of the ESG and CSR (corporate social responsibility) corporate finance research, Gillan, Koch, and Starks (2021) explained that although empirical evidence indicates firms’ ESG profiles and activities are strongly related to the firms’ markets, leadership, and ownership characteristics, as well as their risk, performance, and values, there still exist conflicting hypotheses and results and, consequently, debates on these relationships.

3 In a search through JSTOR and EBSCO, I did not find any articles in finance journals on this topic earlier than those in the Financial Analysts Journal.

4 See, for example, Zingales (2020).

5 Hart and Zingales (2017) argued that shareholder welfare is not the same as shareholder wealth (from market value) because for many corporate activities, profit and damage are inextricably linked. Thus, rather than shareholder wealth maximization, the appropriate objective function should be shareholder welfare, which combines shareholder wealth with negative externalities generated by the corporation’s profit-making activities. Karpoff (2021) took another stance, arguing that the stakeholder model can lead to more conflict, managerial opportunism, and resource misallocation. He supported the traditional shareholder primacy model except for conditions under which externalities become large, in which case those externalities should be considered by managers.

8 Consistent with this hypothesis, Starks, Venkat, and Zhu (2020) provided empirical evidence that institutional investors with longer horizons have greater preferences for high-ESG firms and that such investors show more patience toward high-ESG firm management when they encounter poor stock or earnings performance.

9 Earlier studies had examined the performance of portfolios with and without South African stocks. See, for example, Grossman and Sharpe (1986), also discussed in this review.

10 The expense ratios of the SRI funds and the matching sample of conventional funds were also close in magnitude.

11 It should be noted that not all firms were included in the analysis; they omitted any firms that had no strength or concern indicators. That is, they omitted the firms with neutral ESG performance, thus focusing on returns to the firms with the best and worst performance.

12 Hong and Kacperczyk (2009) focused on a more narrow set of shunned industries, the so-called sin stocks, which consist of firms in the alcohol, tobacco, and gaming industries.

13 The circular economy can be compared with a linear economy, in which manufacturing products results in resource extraction and subsequent product consumption and disposal.

14 In 1963, the journal published an article that considered whether investors should not invest in tobacco firms given the health warnings about smoking. However, the article did not focus on the social responsibility of investing in tobacco firms but, rather, was centered on a thorough analysis of the expected financial effects of the health warnings and conflicting scientific studies.

15 The Sullivan Principles, developed in 1977 by Dr. Leon Sullivan, consisted of six principles that outlined a corporate code of conduct for doing business in South Africa. These principles had suggestions on nonsegregation, equal and fair employment practices and pay, development of training programs, promotion, and improving the quality of life outside the work environment. See the appendix of Ennis and Parkhill (1986) for more information.

16 See Chambers, Dimson, and Quigley (2020) for a case study discussing one university endowment’s decision regarding divestment and climate change considerations.

17 See Governance & Accountability Institute (2020).

18 In June 2021, the IIRC and SASB merged to become the Value Reporting Foundation.

19 This relative difference in usage is also reflected in global media counts. A search of Factiva showed that both phrases have had increasing usage over time, but “corporate social responsibility” was used in a total of 295,178 articles from newspapers, newswires, industry publications, websites, company reports and other sources from 1978 through 2020 and “social responsibility of business” was used in a total of 1,822 articles over the same period.

References

- Albuquerque, R., Y. Koskinen, S. Yang, C. Zhang. 2020. Resiliency of Environmental and Social Stocks: An Analysis of the Exogenous COVID-19 Market Crash. Review of Corporate Finance Studies 9 (3) 593– 621 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/rcfs/cfaa011

- Amel-Zadeh, A., G. Serafeim. 2018. Why and How Investors Use ESG Information: Evidence from a Global Survey. Financial Analysts Journal 74 (3) 87– 103 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2469/faj.v74.n3.2

- Andersson, M., P. Bolton, F. Samama. 2016. Hedging Climate Risk. Financial Analysts Journal 72 (3) 13– 32 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2469/faj.v72.n3.4

- Barber, B., A. Morse, A. Yasuda. 2021. Impact Investing. Journal of Financial Economics 139 (1) 162– 85

- Bénabou, R., J. Tirole. 2010. Individual and Corporate Social Responsibility. Economica 77 (305) 1– 19 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0335.2009.00843.x

- Bernstein, W. J. 2013. The Paradox of Wealth. Financial Analysts Journal 69 (5) 18– 25 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2469/faj.v69.n5.1

- Bradshaw, T. F. 1971. The Corporation Executive’s View of Social Responsibility. Financial Analysts Journal 27 (5) 30– 31, 70– 72 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2469/faj.v27.n5.30

- Brière, M., J. Peillex, L. Ureche-Rangau. 2017. Do Social Responsibility Screens Matter When Assessing Mutual Fund Performance? Financial Analysts Journal 73 (3) 53– 66 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2469/faj.v73.n3.2

- Brown, S. J. 2016. Climate Risk. Financial Analysts Journal 72 (3) 9– 10 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2469/faj.v72.n3.5

- Brown, S. J. 2020. The Efficient Market Hypothesis, the Financial Analysts Journal, and the Professional Status of Investment Management. Financial Analysts Journal 76 (2) 5– 14

- Business Roundtable. 2019. Business Roundtable Redefines the Purpose of a Corporation to Promote ‘an Economy That Serves All Americans’ (19 August). www.businessroundtable.org/business-roundtable-redefines-the-purpose-of-a-corporation-to-promote-an-economy-that-serves-all-americans.

- Capelle-Blancard, G., A. Desroziers, O. D. Zerbib. 2021. Socially Responsible Investing Strategies under Pressure: Evidence from COVID-19. Working paper, Université Paris (19 February).

- Caseau, C., G. Grolleau. 2020. Impact Investing: Killing Two Birds with One Stone? Financial Analysts Journal 76 (4) 40– 52 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0015198X.2020.1779561

- CDP, CDSB, GRI, IIRC, and SASB. 2020. Statement of Intent to Work Together towards Comprehensive Corporate Reporting (September). www.cdp.net/en/articles/media/comprehensive-corporate-reporting.

- Chambers, D., E. Dimson, E. Quigley. 2020. To Divest or to Engage? A Case Study of Investor Responses to Climate Activism. Journal of Investing 29 (2) 10– 20 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3905/joi.2020.1.114

- Christensen, H. B., L. Hail, C. Leuz. 2019. Economic Analysis of Widespread Adoption of CSR and Sustainability Reporting Standards. Working paper, Chicago Booth School of Business (25 January).

- Davies, S. W., E. D. Van Wesep. 2018. The Unintended Consequences of Divestment. Journal of Financial Economics 128 (3) 558– 75 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2018.03.007

- de Jong, M., A. Nguyen. 2016. Weathered for Climate Risk: A Bond Investment Proposition. Financial Analysts Journal 72 (3) 34– 39 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2469/faj.v72.n3.2

- Derwall, J., N. Guenster, R. Bauer, K. Koedijk. 2005. The Eco-Efficiency Premium Puzzle. Financial Analysts Journal 61 (2) 51– 63 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2469/faj.v61.n2.2716

- Döttling, R., S. Kim. 2021. Sustainability Preferences under Stress: Evidence from Mutual Fund Flows during COVID-19. Working paper (6 May).

- Ennis, R. M., R. L. Parkhill. 1986. South African Divestment: Social Responsibility or Fiduciary Folly? Financial Analysts Journal 42 (4) 30– 38 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2469/faj.v42.n4.30

- E.T. Jackson and Associates Ltd. 2012. Unlocking Capital, Activating a Movement: Final Report of the Strategic Assessment of the Rockefeller Foundation Impact Investing Initiative. www.rockefellerfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/Impact-Investing-Evaluation-Report-20121.pdf.

- Freeman, O. L. 1967. World Food Needs. Financial Analysts Journal 23 (5) 19– 22 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2469/faj.v23.n5.19

- Friedman, M. 1962. Capitalism and Freedom. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

- Friedman, M. 1970. A Friedman Doctrine—The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase Its Profits. New York Times Magazine (September 13): 379 425– 27

- Gillan, S., A. Koch, L. Starks. 2021. Firms and Social Responsibility: A Review of ESG and CSR Research in Corporate Finance. Journal of Corporate Finance 66

- Goetzmann, W. N. 2020. The Financial Analysts Journal and Investment Management. Financial Analysts Journal 76 (3) 5– 21

- Goldstein, I. L. Yang. 2017. Information Disclosure in Financial Markets. Annual Review of Financial Economics 9 101– 25 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-financial-110716-032355

- Gorte, J., J. Hale, B. McGannon, G. Dyer, B. Gridley, B. Rees, J. Zinner. 2020. Public Comments Overwhelmingly Oppose Proposed Rule Limiting the Use of ESG in ERISA Retirement Plans. www.ussif.org/Files/Public_Policy/DOL_Comments_Reporting_FINAL.pdf.

- Governance & Accountability Institute. 2020. 2020 S&P 500 Flash Report. www.ga-institute.com/research-reports/flash-reports/2020-sp-500-flash-report.html.

- Gray, D. H. 1971. Standards of Corporate Responsibility Are Changing. Financial Analysts Journal 27 (5) 28– 29, 73– 74 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2469/faj.v27.n5.28

- Grossman, B. R., W. F. Sharpe. 1986. Financial Implications of South African Divestment. Financial Analysts Journal 42 (4) 15– 29 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2469/faj.v42.n4.15

- Hall, J. P. 1971. The Professional Investor’s View of Social Responsibility. Financial Analysts Journal 27 (5) 32– 34 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2469/faj.v27.n5.32

- Hall, J. P. 1986. Ethics in Investment: Divestment. Financial Analysts Journal 42 (4) 7, 30

- Hamilton, S., H. Jo, M. Statman. 1993. Doing Well While Doing Good? The Investment Performance of Socially Responsible Mutual Funds. Financial Analysts Journal 49 (6) 62– 66 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2469/faj.v49.n6.62

- Hart, O., L. Zingales. 2017. Companies Should Maximize Shareholder Welfare Not Market Value. Journal of Law, Finance, and Accounting 2 (2) 247– 75 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1561/108.00000022

- Henderson, H. 1973. The Limits of Traditional Economics: New Models for Managing a ‘Steady State Economy.’ Financial Analysts Journal 29 (3) 28– 32 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2469/faj.v29.n3.28

- Heyne, P. T. 1971. The Free-Market System Is the Best Guide for Corporate Decisions. Financial Analysts Journal 27 (5) 26– 27, 72– 73 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2469/faj.v27.n5.26

- Hong, H., M. Kacperczyk. 2009. The Price of Sin: The Effects of Social Norms on Markets. Journal of Financial Economics 93 (1) 15– 36 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2008.09.001

- Ilhan, E., P. Krueger, Z. Sautner, L. T. Starks. 2021. Climate Risk Disclosure and Institutional Investors. ECGI Finance Working Paper 661/2020.

- James, P. 1967. World Food Needs: Response. Financial Analysts Journal 23 (5) 22– 24

- Joseph, S. L. 1955. The New Capitalism. Analysts Journal 11 (1) 71– 74

- Kahn, I. 1971. Financial Analysts Digest: The Gilbert Brothers—Gadflys or Eagles? Financial Analysts Journal 27 (3) 89– 92

- Karpoff, J. 2021. On a Stakeholder Model of Corporate Governance. Financial Management 50 (2) 321– 43 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/fima.12344

- Khan, M. 2019. Corporate Governance, ESG, and Stock Returns around the World. Financial Analysts Journal 75 (4) 103– 23 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0015198X.2019.1654299

- Khan, M., G., Serafeim A.. Yoon 2016. Corporate Sustainability: First Evidence on Materiality. Accounting Review 91 (6) 1697– 1724

- Krueger, P., Z., Sautner L.. Starks 2020. Importance of Climate Risks for Institutional Investors. Review of Financial Studies 33 (3) 1067– 1111

- Litterman, R. 2011. Pricing Climate Risk Appropriately. Financial Analysts Journal 67 (5) 4, 6, 8–10 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2469/faj.v67.n5.6

- Litterman, R. 2015. David Swensen on the Fossil Fuel Divestment Debate. Financial Analysts Journal 71 (3) 11– 12 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2469/faj.v71.n3.3

- Norby, W. C. 1971a. Editorial Viewpoint. Financial Analysts Journal 27 (3) 7

- Norby, W. C. 1971b. Editorial Viewpoint: The Institutional Investor and Social Responsibility. Financial Analysts Journal 27 (5) 13

- Norby, W. C., F. G. Stone. 1972. Objectives of Financial Accounting and Reporting from the Viewpoint of the Financial Analyst. Financial Analysts Journal 28 (4) 39– 45, 76– 81 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2469/faj.v28.n4.39

- Price, R. 1967. World Food Needs: Response. Financial Analysts Journal 23 (5) 24– 25

- Quinson, T. 2021. Biden Administration Considers Reversing Trump’s ESG Rule Change. Bloomberg Green (20 January). www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-01-20/biden-administration-considers-reversing-trump-s-esg-rule-change.

- Regan, P. J., D. A. Love. 1985. Pension Fund Perspective: On South Africa. Financial Analysts Journal 41 (3) 14– 15

- Rogers, J. 2014. A New Era of Fiduciary Capitalism? Let’s Hope So. Financial Analysts Journal 70 (3) 6– 12 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2469/faj.v70.n3.1

- Schotland, R. A. 1980. Divergent Investing for Pension Funds. Financial Analysts Journal 36 (5) 29– 39 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2469/faj.v36.n5.29

- Serafeim, G. 2020. Public Sentiment and the Price of Corporate Sustainability. Financial Analysts Journal 76 (2) 26– 46 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0015198X.2020.1723390

- Shiller, R. J. 2013. Capitalism and Financial Innovation. Financial Analysts Journal 69 (1) 21– 25 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2469/faj.v69.n1.4

- Siegel, L. B. 2012. Fewer, Richer, Greener: The End of the Population Explosion and the Future for Investors. Financial Analysts Journal 68 (6) 20– 37 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2469/faj.v68.n6.2

- Starks, L., P. Venkat, Q. Zhu. 2020. Corporate ESG Profiles and Investor Horizons. Working paper (24 December).

- Statman, M. 2000. Socially Responsible Mutual Funds. Financial Analysts Journal 56 (3) 30– 39 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2469/faj.v56.n3.2358