Abstract

The July/August 1974 issue of Financial Analysts Journal included an article with the provocative title, “Earnings per Share Don’t Count.” Author Joel M. Stern, then a vice-president of Chase Manhattan Bank, was denying the relevance of the central metric of prevailing equity analysis, known by the abbreviation EPS. He encouraged investors to look beyond Wall Street’s customary EPS × P/E multiple = price target model. Stern’s landmark article opened the door for research that offers a broader perspective on the sources of equity value. Today’s wider set of valuation tools is essential in view of the changed composition of the stock universe over the past several decades.

PL Credits:

Stern’s Radical Proposition

Fifty years ago, Joel Stern (1941–2019) challenged the equity research establishment in the pages of Financial Analysts Journal (July/August 1974), penning an article titled, “Earnings per Share Don’t Count.” Stern, at the time a vice president of Chase Manhattan Bank and also a columnist for the Financial Times and an adjunct professor at the University of Wisconsin, presented several illustrations to demonstrate the logical impossibility of stock prices being a function of earnings per share (EPS).

One example involved two companies with equivalent EPS and the same expected growth rate. They are identical in every way, except that one can achieve its growth without raising any additional capital and the other requires one additional dollar of capital for every incremental dollar of sales. If the latter company finances its growth with equity, its earnings will be diluted and its EPS will fall behind the former’s. If, alternatively, the second company raises debt to finance its growth, the added financial risk will reduce its share price. The market cannot logically value these two companies’ shares at the same price.

Rather than the inherently flawed metric of EPS, Stern wrote, the market prices stocks based on “anticipated earnings net of the amount of capital required to be invested in order to maintain an expected rate of growth in profits.” He dubbed this stream “free cash flow” (FCF), which he defined as “the expected future stream of cash flows that remains after deducting the anticipated future capital requirements of the business.”

Stern thus originated a now widely used metric. This is notwithstanding the statement in the work of Bhandari and Adams (Citation2017) that FCF was introduced by Michael Jensen in 1986. In reality, Jensen acknowledged Stern’s coining of the term, although his definition differed. Jensen’s adoption of the concept deeply influenced agency theory, which seeks to explain and resolve problems in the relationship between business principals and their agents.

Elaborating on his novel metric, Stern presented in his article an FCF model consisting of six key variables, meant to represent the process employed by the sophisticated investors who actually determine stock prices:

Net operating profit after taxes.

Amount of new capital invested.

Expected rate of return on new capital invested.

Length of time (in years) the specified levels of (2) and (3) are expected to continue.

The degree of business risk perceived in each of the firm’s product lines by sophisticated investors.

The tax saving provided by debt financing by the deductibility of interest expense.

Variables (1) and (2) indicate the current magnitude of FCF, variables (2), (3), and (4) determine the expected future growth rate of FCF, and variables (5) and (6) determine the appropriate discount rate. (Note that variable (5) highlights risk, which is typically assigned a subordinated role to growth in EPS-based analysis in the assignment of price-earnings multiples.)

By contending that stock prices were discovered via an elaborate model of this sort, Stern called into question the massive investment in time and energy by brokerage firms and asset managers in forecasting EPS. In his effort to dethrone EPS, he also rebuked corporations’ efforts to nudge analysts toward their quarter-by-quarter earnings guidance, typically with an aim of slightly beating it to create a pop in the stock price. Most important, Stern opened the door to the far wider array of valuation tools now available to equity investors.

Reception and Influence

Stern’s broadside against equity analysts’ favorite metric made an immediate and strong impression even on MBA students at Harvard Business School, who were ordinarily more immersed in management-oriented case studies than in academic discussions of financial theory. In the annual student-produced stage show, a character named Ernie Bershear turned out to be innumerate. That set up the theatrical’s admittedly less than uproarious climactic line, “Ernie Bershear don’t count.”

As a more substantive example of the influence of Stern’s iconoclastic article, Rappaport (Citation1979) cited it along with the statement, “The EPS standard, and particularly a short-term EPS standard, is not, however, a reliable basis for assessing whether [an] acquisition will in fact create value for shareholders.” Footnote1

Testifying to the breakthrough represented by “Earnings per Share Don’t Count,” Maditinos, Maranha, and Alonso (Citation2007) wrote, concerning a long-run shift of focus in valuation methods:

Value-Based ManagementFootnote2 gained recognition almost simultaneously with the recognition that accounting data were no longer providing sufficient information about the performance of the company. Stern (Citation1974) was the first to present this recognition and to suggest that sophisticated investors should be focused on free cash flows (FCF).Footnote3

Earnings versus Cash Flow for Analysis

Stern’s title, “Earnings per Share Don’t Count,” coupled with an elaborate model constructed upon FCF, suggested that FCF is more closely linked to stock prices than EPS is. Present-day advocates of FCF contend that it is a superior metric for purposes of equity valuation. For example, Domash (Citation2019) writes:

While most investors and analysts focus on earnings per share at quarterly report time, research has found “free cash flow” to [be] a better predictor of future share price performance.Footnote4

That article’s authors dissect selected accounting practices in their effort to explain why cash flow is not inherently superior to earnings in determining equity value. For instance, if a company promises to provide employees retirement health benefits, which constitute a compensation expense, cash flow is completely unaffected. Earnings, on the other hand, immediately reflect the cost increase by incorporating an expense equal to the deferred compensation’s present value.

Foerster, Tsagarelis, and Wang (Citation2017) compare cash flow and income statement–based measures as predictors of stock returns. They acknowledge, based on previous research, that certain metrics derived from the income statement are useful in predicting stock returns. At the same time, they note that as demonstrated by the Enron and WorldCom bankruptcies, it is possible for a company to report positive Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) income over many years while simultaneously experiencing negative operating cash flow or FCF.

Examining predictors of stock performance not based on income statements, the article’s authors find particularly strong results for direct cash flow measures, which isolate recurring value-creation activities from nonrecurring ones. The direct method, encouraged by both International Financial Reporting Standards and US GAAP but used by a minority of companies, organizes financial data into clusters of homogeneous business activities. Foerster et al. (Citation2017) find that stocks ranked in the highest decile by direct cash flow outperform those in the lowest decile by 10% annually on a risk-adjusted basis.

The Legacy of “Earnings per Share Don’t Count”

Ultimately, the greatest contribution of “Earnings per Share Don’t Count” was its opening of minds to fresh approaches to securities analysis. Deemphasizing EPS represented a major departure from established practice. Writing about per-share earnings just one year earlier, Benjamin Graham observed, “The quarterly figures, and especially the annual figures, receive major attention in financial circles, and this emphasis can hardly fail to have its impact on the investor’s thinking.”Footnote5

Graham noted a lengthy Wall Street Journal discussion of the extent to which “many analysts” were troubled by Dow Chemical’s decision to include a $0.21/share item in its regular profits for 1969 instead of classifying it as an extraordinary item.Footnote6 Evidently, he said, many millions of dollars of Dow’s market capitalization hinged on the precise EPS percentage gain over 1968. The famed father of value investing called this obsessiveness absurd, but it testifies to analysts’ preoccupation with EPS at the time that Stern began criticizing the metric. (The index of the 1973 book in which Graham recounted the Dow Chemical event includes no entry for cash flow.)

As detailed below, various contemporary independent research providers operate entirely outside the EPS × price/earnings multiple (P/E) = price target framework. Moreover, some Wall Street research departments now incorporate cash flow measures into equity reports that continue to focus primarily on EPS. For example, a 2022 survey of research reports on Meta (Facebook) found Barclays including FCF on a per-share basis as the numerator of a metric labeled “FCF yield.” J.P. Morgan provided a variant based on FCF to the firm (before dividend payments): “FCFF yield.” Certain other kinds of non-EPS measures appeared in the Meta reports as well. Phillip Capital related its price target to projections of discounted cash flow. Needham’s summary included a metric called “operating income before depreciation & amortization and stock compensation” (OIBDA).Footnote7

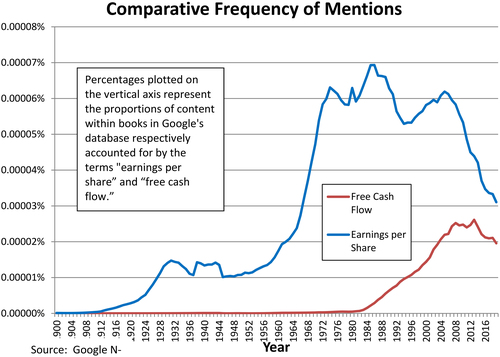

illustrates a further sign of FCF’s growing prominence in the investment conversation. Over time, the number of references to FCF in books within Google’s database has grown relative to EPS references. In 2019, the most recent year for which these statistics are available, FCF received 63% as many mentions as EPS. Twenty years earlier, that ratio was just 24%.

Unsurprisingly in light of that growth, FCF analysis now receives detailed discussion in the CFA® Program curriculum. This is evidence that FCF has become a fixture of thorough equity analysis. After all, the CFA Institute Curriculum Committee surveys practitioners to ascertain which skills are imperative for charterholders to master. Pinto (Citation2024) comment, “Analysts often use more than one method to value equities, and it is clear that free cash flow analysis is in near universal use.”Footnote8

Indeed, one might wonder how analysts could even function in today’s equity market without supplements to EPS. Over time, the universe of stock issuers has shifted increasingly toward companies that derive their success from the creation of intellectual property (IP). The analytics company Clarivate reports, “As of 2018, intangible assets accounted for 84% of market capitalization of S&P 500 companies, compared to just 12% four decades ago.”Footnote9 Many asset-lite enterprises report no earnings because existing accounting standards require them to expense, rather than capitalize, outlays that generate the IP from which profits flow. Using zero or a negative number as the denominator would produce a meaningless P/E, so for companies that lack positive GAAP earnings, analysts must pivot to multiples of other metrics, such as sales or EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization). The fact that profitless-according-to-GAAP companies do not conveniently fit into the traditional EPS × P/E = PT straitjacket has not deterred investors from frequently—and appropriately—awarding them multibillion-dollar valuations.

This transformation was already underway when “Earnings per Share Don’t Count” appeared fifty years ago. Lev and Gu (Citation2016) find a steady, sixty-plus-year decline in the correlation between stock prices and reported GAAP earnings. Fortunately, investors now have access to alternative forms of equity analysis that are well adapted to the changed environment, thanks at least in part to the publication of Joel Stern’s pathbreaking article.

Stern himself became chairman and chief executive officer of Stern Stewart & Co., which developed economic value added, a measure of a company’s net profit less the capital charge associated with funding its investments. Among other research providers that are attuned to contemporary conditions, Credit Suisse HOLT replaces simple indicators such as EPS with cash flow return on investment, an internal rate of return measure derived from proprietary methodology. Valens Research rejects reported earnings in favor of metrics embodied in the Uniform Adjusted Financial Reporting Standards (UAFRS). These constitute “an alternative set of standards for reviewing and analyzing financial statements aimed at creating more reliable and comparable reports of corporate financial activity” described in UAFRS.org (Citation2023). In short, investors who choose not to be limited by one demonstrably imperfect valuation model now have abundant support.

Conclusion

Half a century ago, Joel Stern exposed internal contradictions in the theory underlying that era’s dominant form of securities analysis. He was early in recognizing the inadequacies of GAAP accounting values as determinants of equity values. Stern did not, however, propose replacing the established theory’s central feature, EPS, with a single, similarly simplistic valuation measure. That would not have represented a step forward; some research has found that the metric he criticized in “Earnings per Share Don’t Count” actually explains stock prices better than FCF.

Instead, Stern’s article opened practitioners’ minds to a variety of fresh approaches to equity analysis. By publishing Stern’s conceptual breakthrough, Financial Analysts Journal helped to prepare investment professionals for the subsequent increased prominence of stocks that required newer techniques for evaluation.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Don Chew and Bennett Stewart for their comments and suggestions. Any remaining errors or omissions are solely the authors’ responsibility.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Martin S. Fridson

Martin S. Fridson is Chief Investment Officer, Lehmann Livian Fridson Advisors, New York, New York.

Jack J. Beyda

Jack J. Beyda is a Research Analyst at IGS Investors LLC.

John H. Lee

John H. Lee is a Principal Project Finance Analyst at Sempra Infrastructure, San Diego, California. Send correspondence to Martin S. Fridson at [email protected].

Notes

1 Rappaport (Citation1979)

2 Mind Tools Content Team (Citation2024) provided the following definition: Value-based management (VBM) is a mindset that views the value of an organization as the ultimate measure of success. Successful VBM depends on highly effective strategic planning, supported by a performance management system that drives the value mindset into the organization's overall culture.

3 Maditinos, Maranha, and Alonso (Citation2007, 4).

4 Domash (Citation2019).

5 Graham (Citation1973, 165).

6 Ibid., 170–171.

7 Fridson (Citation2023, 69–70).

8 Pinto et al. (2023, 2).

9 Khaksari (Citation2023).

References

- Barone, Adam. 2023. “What Is an Asset? Definition, Types, and Examples.” Investopedia. October 24.

- Bhandari, Shyam B., and Mollie T. Adams. 2017. “On the Definition, Measurement, and Use of the Free Cash Flow Concept in Financial Reporting and Analysis: A Review and Recommendations.” Journal of Accounting and Finance 1 (17): 11–19.

- Domash, Harry. 2019. “Earnings per Sha vs. Free Cash Flow.” Santa Cruz Sentinel. December 19. https://www.santacruzsentinel.com/2019/12/19/earnings-per-share-vs-free-cash-flow-harry-domash-online-investing/.

- Foerster, Stephen R., John Tsagarelis, and Grant Wang. 2017. “Are Cash Flows Better Stock Return Predictors Than Profits?” Financial Analysts Journal 73 (1): 73–99. doi:10.2469/faj.v73.n1.2.

- Fridson, Martin. 2023. The Little Book of Picking Top Stocks. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Graham, Benjamin. 1973. The Intelligent Investor: A Book of Practical Counsel. 4th Rev. ed. New York: Harper Business.

- Khaksari, Esmaeil. 2023. “Why the Rise of Intellectual Property Value Means IP Leaders Need Better Budget Management.” Clarivate, May 30. https://clarivate.com/blog/why-the-rise-of-intellectual-property-value-means-ip-leaders-need-better-budget-management/#:∼:text=As%20the%20business%20value%20of,just%2012%25%20four%20decades%20ago.

- Lev, Baruch, and Feng Gu. 2016. The End of Accounting and the Path Forward for Investors and Managers. 1st ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Finance.

- Liu, Jing, Doron Nissim, and Jacob Thomas. 2007. “Is Cash Flow King in Valuations?” Financial Analysts Journal 63 (2): 56–68. doi:10.2469/faj.v63.n2.4522.

- Maditinos, DimitriosI, Pedro Maranha, and AzucenaPerez Alonso. 2007. “Investors’ Behaviour and Their Perceptions on Traditional Accounting and Modern Value-Based Performance Measures: Evidence from Greece, Portugal and Austria.” 14th Annual Conference of the Multinational Finance Society – Organised by University of Macedonia and Rutgers University – Thessaloniki, July 1–4.

- Mind Tools Content Team. 2024. “Value-Based Management.” Accessed February 4. https://www.mindtools.com/a4ddcrb/value-based-management.

- Pinto, Jerold E., Elaine Henry, Thomas R. Robinson, and John D. Stowe. 2024. “Free Cash Flow Valuation.” Equity Valuation. Refresher Reading 2024 CFA® Program, Level 2.

- Rappaport, Alfred. 1979. “Strategic Analysis for More Profitable Acquisitions.” Harvard Business Review 57: 99–110.

- Stern, Joel M. 1974. “Earnings Per Share Don’t Count.” Financial Analysts Journal 30 (4): 39–43. [Database] doi:10.2469/faj.v30.n4.39.

- UAFRS.org. 2023. “UAFRS Uniform Adjusted Financial Reporting Standards: Information and Resources on UAFRS Framework and Implementation 2023.” https://www.uafrs.org/