Abstract

Governments continue to narrowly equate improved well-being with economic growth, contrary to decades of development scholarship. The capabilities approach, instead, emphasizes freedom and what individuals are able to do and to be within society. However, it underplays structural determinants of social inequities and says little about violence, a dominant problem in metropolitan areas of Latin America. Framing our analysis around capabilities and theorizing on disadvantage, we examine experiences of inequity and violence in Manaus, a metropolis in the Brazilian Amazon. We show how the threat of physical violence is highly corrosive because it underpins a cluster of disadvantage that profoundly impacts central capabilities, including emotions, bodily integrity, and affiliation. Social isolation is commonplace because interactions are perceived as risks rather than pathways to mutual recognition. Violence begets violence in low-income neighborhoods and this constrains capabilities, causes shame and indignity, and limits potential for self-realization. Policy makers should address how disadvantaged people feel about themselves, relate to others, and are able to decide how to conduct their daily lives.

Keywords:

“When I arrived here, we had little money and few possessions,” said Maria, referring to the neighborhood of São Jorge, Manaus, in the 1960s. “Here was considered Manaus’ periphery, and it looked like people were living in small farms; there were no paved roads or electricity. Our family used to grow food in our garden. I used to swim in the Cachoeiras Igarapé [a river close to her house] and I knew most of our neighbors … The biggest change from those times is more robberies now. … This week a man was killed on my street … A few weeks ago, a man broke into my house. When I encountered him, I was so frightened I thought I’d have a heart attack. I couldn’t move or breathe. Luckily, he left without harming me. … Nowadays, I’m scared of tending my garden because I feel exposed and vulnerable there, and worry about being robbed. I spend most of my time inside my house with all the doors and gates locked.

Maria, like many manauaras, as people from Manaus are known, has tangible reasons to worry about her safety. She lives on Cachoeira Street, considered to be one of the most dangerous in the city, which has 1,660 violent deaths per year (Orellana et al. Citation2017). This equates to almost double Brazil’s national homicide rate (Cerqueira et al. Citation2018). Manauaras are only too aware of the risks of violent death, based on personal experience of violence or stories from family, friends, and the media (Queiroz Citation2019). Consequently, Maria lived in fear of violence because although most of the robberies, assaults, and murders she heard about had affected strangers, she inevitably felt that it could have happened to her or a loved one (Farias Citation2007). Violence, both its potential and lived experience, has become a central part of manauaras’ everyday lives.

In Manaus, the high incidence of violence can be broadly attributed to deep social inequities, deprivation, and policing failures that include institutional racism, abuse of authority, and a disfunctional structure underlying an apparent inability to reduce crime (Riccio et al. Citation2016). Despite some social progress in the decades following the transition to democracy beginning 1985, particularly under Workers Party presidencies, Brazil remains highly unequal, the judicial system slow and ineffectual, and the state largely unaccountable. Poor Brazilians rely on still-inadequate public services and, as argued by Caldeira and Holston (Citation1999), have long been exposed to structural violence. Manaus has the seventh highest gross domestic product (GDP) (IBGE Citation2016) of Brazil’s state capitals, yet social inequality and violence have risen in parallel with economic growth.

The metropolitan centers of Manaus and Belém are central to understanding social, economic, and political change in contemporary Amazonia but have been largely neglected by geographical scholarship. There is, however, a sizable literature exploring the history and consequences of urban-centric development in the region (Seráfico and Seráfico Citation2005; Schor et al. Citation2014; Santos Citation2017). Yet, with few exceptions (for example, Castro Citation2009), there is a relative dearth of qualitative social research in urban Amazonia. This contrasts sharply with the abundance of biophysical research on environmental change in the region (Brondízio et al. Citation2016). Apart from Macdonald and Winklerprins’ (Citation2014) work on peri-urban migration as a “solution” to the limitations of metropolitan life and Lucy Dodd’s (Citation2020) study of rural-urban circulations in eastern Amazonia, we are unaware of any qualitative research exploring the relations between urban development and the lives that urban Amazonian are able to live. Instead, research on urban life and development in Brazil has been centered on favela communities—low-income, informal settlements—in southeastern metropolises, such as Rio de Janeiro. This geographic bias partly reflects uneven development in Brazil and the relative dominance of academic institutions in the southeast. Given the unique social and spatial contexts of southern cities, it is problematic to assume that social practices in their favela communities resonate strongly with urban communities elsewhere in Brazil (Garmany Citation2011).

Methodological Approach

In order to get as close an understanding of the everyday lived experiences of working-class manauaras as possible, we adopted an ethnographic methodology. We used participant observation, and unstructured and semistructured interviews during fieldwork in São Jorge, a working-class neighborhood in Manaus with around 153,000 residents. Social inequalities are striking in São Jorge, with informal housing and veritable mansions within meters of one another. The neighborhood is violent, but not exceptionally. For instance, the homicide rate in São Jorge (40 homicides/100,000 people/year) is only the seventh highest in western Manaus (Nascimento Citation2013).

The first author lived with a local family in São Jorge from August to October 2015, near the notorious Cachoeira Street. During this time, she engaged fully with the host family’s routine, getting to know their neighbors and other locals. She would also walk around the neighborhood stopping at street-food vendors, local markets, small restaurants, and public spaces, conducting around 40 unstructured and semistructured interviews. She visited public schools and healthcare centers, and interviewed staff members, students, and patients.

Qualitative data was coded with ATLAS.ti software, which facilitates the analysis of thematic interconnections. We use the capabilities approach (CA) (Sen Citation1999; Nussbaum Citation2013) to reveal dissonances between economic growth and well-being, understanding the latter in terms of what individuals are able to do and to be within society. Acknowledging the conflicting and diverse effects that development focused on economic growth can have on people’s lives, the CA argues that assessment of well-being should instead be centered on the effective opportunities that people have to lead lives they have reason to value. These opportunities allow for the free exercise of a set of interrelated functionings, which are capabilities that have been realized. Functionings can vary from elementary things, such as being healthy and having a job, to more complex states, such as being happy, having self-respect, or being calm (Sen Citation1999). We used the CA to guide our coding and analysis, as follows. First, we identified the functionings that research participants considered important to their well-being. Then, we analyzed fieldnotes to identify the opportunities (or lack of) that interviewees felt they had to achieve those functionings in their lives. We also noted the reason(s) attributed to achieving, or failing to achieve, a given functioning. We concentrated on these reasons in order to identify capability constraints, finding that violence was the most common.

Theoretical Framing

capabilities approach

The development failures of Manaus’ recent history and Maria’s experience of urban life resonate with the writings of Amartya Sen and others. Low material living standards appeared not to be the main concerns of our research participants, although they were sometimes part of the problem. For this reason, we explore the real opportunities available to the poor in Manaus, using the lens of the CA to interpret our findings. The CA allows us to look at the lives of manauaras in a way that captures the nuances and sources of unfreedoms that constrain their capacities for doings and beings. We find that violence severely constrains people’s capabilities, with grave consequences for well-being, prompting us to engage with additional theorizing on disadvantage. Specifically, Wolff and de-Shalit (Citation2013) help us understand how interactions between structural factors, neighborhood social structures, physical and symbolic violence, and individual capabilities constrain manauaras’ opportunities to flourish.

The CA offers a broader understanding of well-being than traditional economic frameworks. Furthermore, it gives poverty a more nuanced and multidimensional analysis, conceptualizing it as a state of capability deprivation, instead of lack of income or material possessions. This pushes back against dated understandings of urban poverty being simply a lack of basic necessities (Wratten Citation1995). Sen’s (Citation1999) approach recognizes that whether individuals have certain capabilities or not depends on individual features like skills and competencies, and on external conditions, including norms, institutions, and social structures.

Of the ten central capabilities that Martha Nussbaum (Citation2013) considers essential for well-being, we focus on three: emotions, bodily integrity, and affiliation. We do so because our empirical findings suggest these capabilities are the most affected by physical and symbolic violence. Someone has the capability of emotions when their emotional development is not blighted by fear and anxiety, and they are able to have attachments and feelings toward other people. Bodily integrity is defined as being able to move freely from place to place, being secure against violent assault, and having opportunities for reproductive choices. Affiliation is the social basis of self-respect and nonhumiliation, being able to live with others. This includes recognizing and showing concern for other humans and being able to engage in various forms of social interaction.

Agency is central to the CA, both as conceived by Sen (Citation1999) and later reworked by Nussbaum (Citation2013). Indeed, capabilities can be thought of as a sophisticated way of conceptualizing agency (Gangas Citation2016). Agency is linked to an individual’s ability to choose the functionings they value, and their role in society, by participating in economic, social, and political actions (Claassen Citation2016). Hence, the capacity for agency goes together with the expansion of valuable freedoms. In order to be the protagonist of one’s life and contribute to society, a person needs substantive opportunities, including education, to be able to speak in public without fear, and to spend time with others. People can help create such environments and opportunities through their actions; therefore, the capacity of agency is fundamental to assessing what a person can be and do within society (Deneulin and Shahani Citation2009).

The CA is not without its critics. Postcolonial scholars have questioned this approach, emphasizing its continuities with the individualism characteristic of the neoliberal era (Comiling and Sanchez Citation2014; Sayer Citation2014). They suggest the CA tacitly accepts neoliberalism by giving centrality to individual freedom and possessive individualism. Sen acknowledges social arrangements and class concerns, but only as influences that can affect individual freedom and not as structures that restrict it—so the emphasis is on agency rather than structure. We use it to highlight the importance of agency and freedom for the individual’s capacity for beings and doings, whilst not losing sight of the important roles of economic, political, and social structures, which we account for by pairing the CA with corrosive disadvantage, symbolic violence, and recognition. We keep in mind Andrew Sayer’s concern about the standard conceptualization of well-being offered by the CA (Sayer Citation2014, 8): “ … while the aim to set out basic elements of individual flourishing may be appreciated it is likewise essential to determine what forms of social organization enable the condition of the flourishing of each individual to be the flourishing of all.”

corrosive disadvantage

Based on the idea of functionings from the CA, Wolff and de-Shalit (Citation2013) define disadvantage as a lack of genuine opportunity to exercise functionings. They suggest someone has a genuine opportunity, and thus a capability, to do something only if the costs of doing so are reasonable for them to bear. Relevant costs are the impacts on other functionings, and what is reasonable is dependent on context. Designing policies to improve equality, they claim, requires not only identifying those functionings with greatest deficiencies, but also revealing when and why several disadvantages may cluster together. Hence, a more equitable society is one in which disadvantages do not cluster, and it becomes increasingly ambiguous who is the worst off. Wolff and de-Shalit (Citation2013) propose a way of understanding the actions necessary for getting closer to achieving a “society of equals,” in which all people can experience satisfactory levels of well-being. The first step is identifying the least advantaged, which requires understanding the pluralistic nature and interactions of their disadvantages. Assuming that disadvantages are (re)produced by social and political institutions and structures as well as by individuals within communities, or at least be tolerated by them, they advocate analyzing a person’s situation in comparison to others in society. Disadvantage is therefore relational. Their argument is that governments should give special attention to the way in which patterns of disadvantages establish and persist, achievable by searching for corrosive disadvantages and fertile functionings. Corrosive disadvantages generate further detriment, such as unemployment, whereas fertile functionings secure additional benefits, like improved access to employment.

symbolic violence

We propose that violence in Manaus has emerged as a central, corrosive disadvantage in everyday lives, severely constraining people’s capacities for beings and doings. Fear of physical violence was tangible to those we met, yet our understanding of violence is broader and also includes the harm caused by harder-to-see symbolic and structural forms (Farmer Citation2004). Originally conceptualized by Pierre Bourdieu (Citation1989), symbolic violence is that which is “exercised upon a social agent with his or her complicity” (Bourdieu and Wacquant 2002, cited in Lawler Citation2011), relating to the processes and mechanisms for establishing and reproducing relations of domination. Symbolic violence manifests through everyday lived experiences as power relations between those holding greater power over those having lower social status. Accordingly, individuals become constrained through the internalization, acceptance, and reproduction of ideas and structures that subordinate them (Bourdieu Citation1989, Citation2002a). Because symbolic violence is normally without explicit acts of force or coercion, it often goes unrecognized by its victims. Consequently, those affected by it unconsciously act and express themselves—sometimes violently—in ways that contribute to maintaining the sources of unfreedom and inequalities constraining their lives (Bourdieu Citation1989). After identifying violence in its many facets as a corrosive disadvantage, we examine its negative impacts on many functionings that constrain the realization of certain capabilities.

recognition

We also draw on the idea of recognition to highlight the importance of the social (as constituted by relations of mutual recognition) in self-realization (and conversely, how the lack of societal recognition is damaging to the self). Axel Honneth (Citation1995) asserts that the development of self-confidence, self-esteem, and self-respect—the modes by which one can relate to oneself—is only possible and maintained intersubjectively through the recognition of others. Establishing relationships of mutual recognition is, therefore, crucial for self-realization. Achieving mutual recognition goes beyond relations of love and friendship, including legally institutionalized relations of universal respect for the autonomy and dignity of persons, and networks of solidarity and shared values within which the worth of each member of a community can be acknowledged.

circling back to the ca

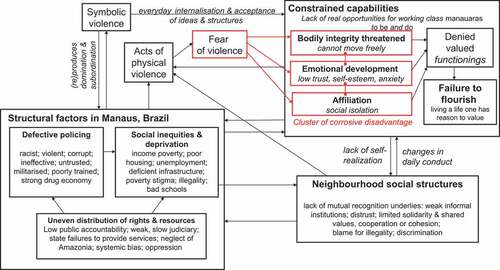

When combined with concepts of corrosive disadvantage, symbolic violence, and recognition, the CA offers a useful way to explore the links between violence and well-being in Manaus from an ethical perspective. We summarize these relationships in a cause-effect diagram (). While we see this approach as being a better alternative to standard growth-focused development models, it is also complementary to more critical perspectives, such David Harvey’s (Citation2016) spatial approach to the dynamics of capital accumulation. Although approaches such as that of Harvey advance a sophisticated critique (in political-ecology terms, the hatchet) of the effects of uneven development that we explore in this paper, he does not advance a positive vision (in political-ecology terms, the seed) against which a just society could look. The CA does this—albeit in individualistic terms—and while Harvey is correct that the CA is reformist rather than revolutionary, to put it bluntly, manauaras and the urban poor elsewhere in Brazil do not, in general, want a revolution. Most people, instead, seek an improvement in their lives and the CA can articulate what needs to change in a way that is at once normative, descriptive, and legible to policy makers (Crocker Citation2008).

Results and Discussion

the backdrop of violence in everyday life

Joelson, 26, recounts that “Many of my friends who grew up with me here were killed because they were involved in drug dealing or street fighting. I used to be a street fighter, too. It was very cool but when I was younger, we used to fight only with our bodies; nowadays, teenagers fight with guns and knives,” Elsewhere in São Jorge, Maura, described a recent incident which had caused her great distress: “The other day my daughter was walking home holding her mobile phone, but when she was close to our house a guy on a motorcycle pulled up and grabbed her mobile and then disappeared. Thank god he didn’t hurt her. Nowadays we hear so many stories about people being killed in that kind of situation, just because of a mobile! It terrifies me.”

Similar incidents are common, with estimates suggesting that in 2016, six people in Manaus were robbed per hour and often injured in the process (Equipe Diário do Amazonas Citation2016). Joelson and Maura’s experiences illustrate how, in Manaus, threats to life and bodily integrity—or related fears—are part of everyday life. Most research participants had experienced such threats or someone close to them had been physically and/or psychologically harmed by them. These experiences are supported by statistics (Orellana et al. Citation2017; Cerqueira et al. Citation2018) and omnipresent reports of violence in Manaus’ newspapers and television stations, ranging from assassinations to thefts with no apparent physical harm, but certainly psychological effects (Queiroz Citation2019). Not surprisingly, constant fear, vulnerability, and anxiety were commonplace. For instance, Andrea, a teenage girl, revealed, “My biggest fear in life is getting shot in my face.” A constant state of worry appears widespread in Brazilian metropolises (Garmany Citation2014; Ferreira Citation2015), clearly undermining people’s emotional well-being and, we posit, individual capacities for free movement and agency.

In order to make their lives safer, the manauara working class attempt to build “precautionary actions” into their daily lives which can severely restrict their freedoms and the exercise of important functionings. For instance, some research participants had quit their jobs or interrupted their livelihoods because they feared becoming a victim. For example, in her previous job, Lena had to regularly deposit money in the local bank. One day when leaving the bank, a woman right next to her was robbed with a gun pointed at her head, naturally leading Lena to worry that this could happen to her, too. Afterward, despite being content with most aspects of her job and happy with the salary, Lena resigned and became unemployed. Andrea used to help her family with its small informal business selling food and drinks at public festivals and events. She said that on many occasions her family had to flee a trading spot because of robberies and street fighting. Juliana Borges (Citation2012) found a similar situation among women who work selling and checking tickets on Manaus’ public buses, which are often robbed, exposing workers to highly dangerous situations. Consequently, many women reported suffering from anxiety and depression, leading some to resign.

This constant perception of risk also resonates with Machado da Silva’s observations on the psychosocial effects of drug trafficking in Rio de Janeiro’s favelas in Homero (Citation2006, 2):

The presence, or the “ghost,” of drug trafficking is constant in the practicalities of everyday life and the subjective preoccupations of favela dwellers … This affects residents’ movements, particularly young people, both where they live and in other urban areas, since they are influenced by places they believe to be permitted to be in, dangerous or not. Thus, the power of drug trafficking appears to be greater than its material ability to impose its “will.”

In Manaus, robberies and other forms of violence are also frequently attributed to drug dealing. Violence is everpresent in manauara lives. This is especially true among the working class whose forms of transport, places of work, and homes—locations relatively insecure compared to the wealthy gated communities—expose them to greater risks of robbery, and the like. Drug trafficking in São Jorge may not be as dominant as in many of Rio’s favelas, yet perceptions of dangerous situations are created and reinforced through personal experiences, the media, and local accounts. For example, there are places in the neighborhood, such as Cachoeira Street, which people try to avoid. People are also acutely aware of the times of the day when it is considered unsafe to be outdoors, whether walking or not, especially if speaking on the phone.

Common to many accounts about life in violent social contexts (Comaroff and Comaroff Citation2006; Koonings and Krujit Citation2007), those affected lose some of their capacity to make decisions and choices that fulfil what they want or need to achieve and perform in life and control their destiny. Accordingly, the tangible risk and fear of violence translates into a loss of access to, and enjoyment from, other capabilities and, hence, undermines individual agency. Violence affects many areas of life and can compound other risks. For example, victims of heat waves in poor and violent neighborhoods in the United States have died because they were afraid of opening their windows and/or leaving their homes to seek help when they felt unwell (Wolff and de-Shalit Citation2013).

Enjoying leisure time and related social and health functionings can be also difficult for working-class manauaras, echoing the reality of many disadvantaged Brazilians. According to official state population surveys, one in four Brazilians has avoided going to recreational places due to fear of violence (PNUD Citation2014), constraining a central capability—to play (Nussbaum Citation2013). Most people interviewed didn’t let children play outside and considered few leisure places, especially outdoors, safe and affordable. This created boredom and frustration for both children and adults because of what one parent described as a “lack of opportunities to do nice things.”

Staying indoors in fortified houses was common in São Jorge, because most people felt unsafe outside their homes. For example, Envira, recently relocated from a provincial town, Tefé, was unemployed and lived in a one-room house, along with her son, grandson, and daughter-in-law. She had barely left her house because she felt Manaus was “too dangerous”; she was terrified to go out alone. She spent days inside with her grandson, watching television. This reorganization of everyday life, with increasing time spent indoors, has also been documented in favelas in Rio de Janeiro (M. Cavalcanti Citation2006).

Fear of violence permeates the lives of all Brazilian social classes, but the poorest are exposed to the greatest threats to life and bodily integrity. For instance, eastern areas of Manaus are renowned for poverty, poor housing, and drug trafficking. Indicative of these socio-spatial inequities, the homicide rate in the relatively wealthy center-south of Manaus was 20/100,000 in 2012, less than a third of the city’s overall rate (66/100,000 inhabitants) (Nascimento Citation2013). “Location” within an urban society is intimately connected with the opportunities people have for minimizing risks to their bodily integrity. Given the Brazilian state’s long-term failure to reduce violence, avoiding becoming a victim is largely a personal task involving changes in daily conduct. Our diagram () illustrates how, for example, the resulting social isolation has neighborhood-scale effects, including widespread distrust and limited cooperation or cohesion.

Wealthier Brazilians can afford safer choices than the poor by living in less violent neighborhoods, relying on private security, avoiding public transport, and paying for private, more-secure schools (Caldeira Citation2000). In contrast, occupying a lower social position within Brazil’s “uncivil democracy”—characterized by a disjunction between a constitution and legal codes, which adhere to the rule of law and democratic values, and citizenship being impaired by the systematic violation of rights, violence, injustice, and impunity (Caldeira and Holston Citation1999, 692)—is associated with greater risks to life and bodily integrity. These risks unsettle the lives of marginalized people and many functionings become insecure (Wolff and de-Shalit Citation2013), serving to aggravate existing disadvantages and creating new ones. For instance, the “choice” of Lena and some participants in Borges (Citation2012) study to become unemployed in order to reduce risks strongly compromised their capacities to support themselves and their families. In São Jorge, community events were canceled after a confrontation between criminal organizations and the police, resulting in five deaths in a single evening (Queiroz Citation2019). In favelas, especially when there are armed conflicts between drug dealers and the police, people miss work and children miss classes, or classes are interrupted, because one cannot leave home or school in the middle of gunfire (Ferreira Citation2015).

Crime and violence in public places on which people depend will impinge a poor person’s capacity to sustain fertile functionings (such as being educated). Violence can trap people in deprivation because they may be unable to improve their socioeconomic condition or capacities for socially transformative agency. The headmaster of a school in São Jorge recounted numerous violent episodes (intimidation, fights, robberies) in and around the school, affecting both students and teachers. In Manaus and Belém, assaults in public schools and robberies on buses are commonplace.

Experiences of violence are inherently unpredictable, despite considerable daily efforts of those living in violent contexts to avoid falling victim (M. Cavalcanti Citation2006; Farias Citation2007). During the first author’s fieldwork, the bakery in front of the house she was staying in was assaulted one morning, leaving its owner dead and two staff members seriously wounded. This surprised many because the immediate area was not thought of as dangerous by local people. Moreover, the morning is generally considered a safe time to be out and about. This atmosphere of uncertainty increases the sensation of lacking control over one’s life, contributing to an overall climate of fear that can lead to disconnection with other people (Ferreira Citation2015).

Finally, the “antipoor” approach of the police in Rio’s favelas (Farias Citation2007) is also a reality in Manaus (Riccio et al. Citation2016), and they largely fail to earn the trust of disadvantaged people. Indeed, police violence in São Jorge was not uncommon. A resident described: “I once saw the police beating a young black guy in front of my house for no reason. He was approached by two policemen who had asked him for his ID, and before he was able to get it to show them, the policemen started to beat him badly. I know this boy and his family. I know he is not involved with crime”.

inequity and the erosion of trust

“Nowadays, I never say hello to people when I am walking in the streets or taking the bus,” said Ivonete, who lived in Alvorada, a low-income neighborhood next to São Jorge.

The fear and anxiety generated by the perceived risk of being killed, harmed, or being robbed affects not only daily routines, but also how people interact with each other. Ivonete is no longer accustomed to saying hello to people on the streets or in public spaces because she fears this might lead to an unwanted close encounter and risk of harm. Related changes in daily conduct and their impacts on neighborhood social structures are illustrated in . Proximity to others was a source of apprehension to many of the research participants in São Jorge. People worried that sharing information and experiences with others could be used for doing maldagem (harm) by those with “bad” intentions. Interactions were therefore permeated by caution and distance, sometimes being close to a total withdrawal from social life, as in the cases of Maria and Envira. This has clearly negative consequences for recognition and therefore affects both self-actualization and the quality of societal relations.

Wariness is understandable, especially because criminal acts can occur even in unlikely public places. Fear of violent robberies in São Jorge means, for example, that local shopkeepers diminish their interactions with customers. Typically, owners fortify storefronts, close off public access to the inside, and serve customers through an iron grill, picking items from the shelves behind them. One such shop owner said that he had been robbed and assaulted many times before and had then fortified his shop because it was the only way to avoid being targeted again. These examples illustrate the social implications of daily struggles to avoid violence in Manaus, sharing commonalities with life in other violent and unequal metropolises (Wilkinson and Pickett Citation2010).

The distrust of others and reducing social interactions erodes the capacity for affiliation, which is based on trust, belonging, respect, and equity. Unfortunately, becoming distrustful emerges from our study as one of the “precautions” people employ to improve their personal security. Distrust can also exacerbate existing problems associated with inequality and class conflicts because people become fearful and strangers to one another, which reinforces social differentiation, stigmatization, and discrimination (Gilligan Citation2000; Farmer Citation2004; Garmany Citation2014). The negative impacts of inequity on affiliation are also prominent in discourses that highlight the global tendency for increasing social inequities and heightened interclass differences (Bourdieu Citation2002a; Sayer Citation2014).

The uneven distribution of rights and resources serve as vivid indicators that select groups with higher social status are more entitled than others to have rights. In highly unequal societies, it is common for disadvantaged people to internalize the association of violence with personal failures to accept or improve their socioeconomic circumstances, rather than linking violence with structural inequities (Caldeira Citation2000; Holston Citation2008). In other words, the manifestation of symbolic violence (see related linkages between structural factors, symbolic violence, and constrained capabilities in ). Hence, Joelson attempts to explain why people commit crimes;

I don’t really know why people become robbers. You can see that in the poorest areas of São Jorge, there are loads of robbers, but there are loads of good and honest people as well. It makes me think about why that happens. If it was because of poverty, then everybody that lives there should be robbers, because everybody there is poor. I think those that go for the crime are opportunistic, they don’t want to work hard, and they are lazy and jealous of others. They want to have what others have without working hard for it.

Like Joelson, Maura also believed that if someone is or wants to be a decent person, and is willing to work hard, then they don’t need to take the “easy” routes. When describing her life trajectory, Maura highlighted many times what a hard-working and “correct” person she has been. However, Maura did not escape related prejudice. She had been verbally abused and humiliated by a neighbor for “looking like” a potential thief when actually she had gone out to deliver cosmetics to the neighbor’s sister. Neither Joelson, Maura, or the majority of the research participants questioned the social conditions that often force people to take the so-called “easy routes,” such as drug trafficking, stealing and robbery, or prostitution. References to the caminho fácil (easy path) or jeito fácil de ganhar a vida (easy way of winning in life [by earning money]) signify dishonest ways of making money, which are perceived not to require the effort and dedication required by “decent” employment. This exemplifies how symbolic violence operates (Bourdieu Citation1989, Citation2002b), obfuscating the awareness of deep structural inequities, such as access to good education, employment, and justice. These experiences are not always articulated yet felt in many ways by the least advantaged, including a lack of opportunities in young adulthood.

Positing personal traits and characteristics as the reasons for committing a crime or succeeding (or not) in escaping poverty is a widespread argument in unequal societies, such as Brazil (Caldeira Citation2000; Holston Citation2008; Garmany Citation2014). Because poverty is widely criminalized, this exerts great pressure on the poor that, in order to have their worth recognized by others, feel the constant need to “prove” that their improved living conditions are the fruits of their hard work and decent character—that they have not come the “easy way” (Caldeira Citation2000). There are racialized dimensions to these notions of “bad” character. The manauara working class, like that of many cities in Latin America, is composed of “new kinds of people,” emerging from the intermingling of Indigenous, European, and Afro-descendant heritages (Salomon and Schwartz Citation1999). The existence of people who combine multiple heritages has challenged and continues to challenge (post)colonial hierarchies based on clear distinctions between discrete racial categories. These categories support the historic and contemporary perception of creolized people as being evil or “of bad character” (Cañizares-Esguerra Citation2009).

violence as a cause and effect of capability failures

We identify negative feedbacks through which urban violence can lead to more violence, as shown in . First, violence contributes to the weakening of neighborhood social structures, limiting opportunities for solidarity and cooperation, thereby exacerbating changes in social norms, low social accountability, and discriminatory social processes. Second, exposure to violence leads some young people to become violent by constraining central capabilities of emotions, affiliation, and bodily integrity. We draw on James Gilligan’s (Citation2000) proposition that violent behavior and crimes arise from the psycho-pathological roots of hidden shame (the opposite of dignity), which severely damages an individual’s self-esteem and self-worth. For Gilligan, violence should be seen as a language that expresses the incapacity of the perpetrators to articulate what they feel and think.

Social structures of mutual recognition (networks, informal institutions) are crucial for fostering personal development and the quality of relationships with others and, overall, these systems strongly shape the levels of violence within societies (Honneth Citation1995; Gilligan Citation2000). Inequalities of opportunities, material wealth, or access to rights serve as constant reminders that individual worth is measured by social position (Marmot Citation2004; Wilkinson and Pickett Citation2010). In highly unequal societies, low social status can impair someone’s capacity to establish healthy relationships with others, breeding feelings of rage, shame, indignity, and distrust. These feelings, if not properly addressed, can manifest destructively as aggressive and violent acts (Honneth Citation1995). Gilligan (Citation2000) and Michael Marmot (Citation2004) argue that shame is not caused by poverty or deprivation in an absolute sense, but relative deprivation because this undermines dignity, self-respect, and pride.

Bodily integrity is essential to a dignified life (Honneth Citation1995; Nussbaum Citation2013) and is clearly threatened by violence. These authors concur that violating bodily integrity is the most profound way to destroy a person’s dignity, self-confidence, and self-respect, with consequences for individual capacities to self-actualize and engage with others. Fear of physical violence can be paralyzing and reinforce distrust and symbolic violence, leading to wariness of people outside of close family and friends, and therefore ultimately limiting self-realization. Consequently, living with everyday disadvantage and the risk of violence can severely constrain capabilities even if someone is not directly affected by physical violence.

Brazil’s young democracy has, on paper, expanded legal rights to all its citizens. However, the state and its institutions continue to privilege the most advantaged and neglect the least advantaged, a process Holston (Citation2008) describes as “differentiated citizenship.” Social inequities remain largely unchanged and most metropolises in Brazil are violent (Cerqueira et al. Citation2019). Although the causes of violence are complex and contested, there is broad agreement that violence disproportionately affects people from lower social classes (Gilligan Citation2000; Marmot Citation2004; Wilkinson and Pickett Citation2010). However, the situation is worse still for the north and northeast of Brazil, historically neglected regions which are the poorest in the country. For example, roughly half (48.8 percent) of children in the north live in poverty, compared to 21.5 percent in the southeast (Cerqueira et al. Citation2019).

Stark social inequities, and weak and largely unaccountable state institutions, impair the lives of the urban poor in Manaus, and other Brazilian metropolises. Not surprisingly, perhaps, these cities have become fertile locations for violence, the drug economy, and other illicit activities with links to violence. Multidimensional deprivation in Amazonian cities fosters increasing drug consumption, dealing, and recruitment into drug-linked criminal organizations (Machado Citation2001). Urban violence in Amazonia has escalated this century, overtaking the southeast (Cerqueira et al. Citation2019). In the decade following the foundation of Família do Norte criminal group in 2006, the homicide rate in Manaus rose 54 percent (Drugowick and Pereda Citation2019). The Brazilian experience resonates with broader arguments that the underlying structural causes of violence are social inequities, deprivation, and defective policing, including how this perpetuates the drug economy (Comaroff and Comaroff Citation2006; Wilkinson and Pickett Citation2010).

policy and police reform

Police brutality and abuse of power over the most disadvantaged is widespread in Brazil, particularly in deprived neighborhoods in large cities (Paes-Machado and Noronha Citation2002; Wacquant Citation2008). This is laid bare by the estimated 3,148 people killed by Brazilian police during the first half of 2020 (Velasco et al. Citation2020). The judiciary and the country’s state police forces epitomize major discrepancies between democratic rules and the institutional practices that disrupt them (Caldeira Citation2000; L. M. L; Ribeiro Citation2013). Arthur Costa (Citation2011) argues that police in Latin America tend to have enormous discretionary power in their interaction with the population, in spite of attempts to legally limit their activities. They contend that policing practices reflect and perpetuate structures of domination and a model of social control that is permeated by a logic of social exclusion, racism, and spatial segregation. In postdictatorship Brazil, police apparatus moved into the hands of state governors and became integral to institutional arrangements which strengthen political elites. Recent work in “southern criminology” also highlights the legacy of United States support of authoritarian policing in Brazil from the 1960s through 1980s (Cavalcanti and Garmany Citation2020).

Paradoxically, though few Brazilians trust the police, there is popular support for police violence. Only 17–18 percent of the Brazilian population trust the civil and military police (CRISP Citation2012), with distrust attributed to perceived bias, inefficiency, and corruption (L. M. L. Ribeiro Citation2013). Support for police violence against suspected criminals is, however, widespread across social classes. This includes the working class who, along with Black people, are the principal victims of police violence (Paes-Machado and Noronha Citation2002). Caldeira’s explanation (Citation2000, Citation2002) is that working-class people often believe violent repression and punishment to be the solution to crime due to historical state disrespect for civil rights, low confidence in the justice system, and the aforementioned perception that criminality reflects weak character and personal failures. Evidently, disadvantaged Brazilians are often denied their right to live safely, although this is guaranteed by the Brazilian Constitution, which asserts that public security is the state’s duty and a right of all citizens. The Program for Public Security with Citizenship (PRONASCI), created in 2007, was an attempt by policy makers to reconcile security issues with human rights through legislation to reform police training, strengthening police links with communities, modernizing the prison system, increasing societal participation in security-related decisions, and creating social programs to prevent violence (Oliveira and Rocha Citation2014).

Amazonas State attempted to institutionalize PRONASCI’s reforms through new neighborhood police patrols: Ronda do Bairro. The program focused on preventive policing, interaction with citizens, technology, and better integration between the military and civil police (Riccio et al. Citation2016). Although interventions such as Ronda do Bairro or police pacification units in Rio de Janeiro claim to be progressive in design, they face familiar struggles on the ground. Most importantly, local policing continues to embody corrupt and discriminatory practices, including abuse of power, stigmatization of the poor and Black people, and a resistance to accept or adopt more humanistic approaches toward security issues (Ribeiro Citation2013). Consequently, these initiatives remain controversial and have largely failed to reduce crime (Drugowick and Pereda Citation2019).

The police and judiciary continue to reproduce the “antipoor approach,” as can be inferred by the profile of the Amazonas prison population. Forty percent of those incarcerated are under 25 years old (MJSP Citation2016), 75 percent did not attend secondary school (an indication of poverty), and 68 percent of prisoners are pretrial “provisional” detainees (Gavirati Citation2018). The latter problem reflects judicial slowness in processing cases, and limited access to legal defense. Amazonas has one of the country’s lowest numbers of “public defenders” available to represent prisoners (Secretaria-Geral Citation2015).

Current prospects for achieving more humanistic public-security policy and practices in Brazil remain gloomy. President Jair Bolsonaro has incentivized repression and violence, and has weakened the already fragile institutional mechanisms for controlling the police. In 2019 he proposed a legal reform to removing the police and army’s obligation to buy ammunition with batch numbers, making it harder to trace deadly shots from the police or army (Globo Citation2020). The crime-prevention package proposed by Sergio Mouro, when Minister of Justice, was criticized for increasing the severity of criminal punishment, enabling imprisonment earlier on in the judicial process and expanding the situations in which police violence against suspected criminals is deemed justifiable (Senado Notícias Citation2019). The challenges in overcoming antidemocratic and exclusionary practices within Brazil’s security apparatus appear intractable and go beyond policy or the judiciary. Sharing similarities with Desmond and Western (Citation2018, 308) analysis in the United States, the existence of “close links between poverty, poor health, violence, and incarceration point to a type of compounded disadvantage that grows out of a vast failure of social policy and state neglect.”

Conclusions

Considering development as “a process of expanding the real freedoms that people enjoy,” as proposed by Sen (Citation1999, 1), we find metropolitan development in Amazonia has failed to deliver. The Amazonian urban working-class’s material standards of living might have improved, but this has not been translated into improved urban life and individual capacities for beings and doings. Manaus’s ten-fold population growth in half a century reflects the aspirations of many poor Amazonians to achieve a better life, yet the well-being of the city’s least advantaged appears to be in decline. Inequities in Manaus and other Latin American cities shape the chances of experiencing material deprivation and opportunities, and exposure to symbolic and physical violence. This violence, in turn, contributes to constrained capabilities, shame, and indignity, and limits potential for self-realization. These negative feedbacks between constrained capabilities and weakened neighborhood social structures are shown in . In capitalist societies where success and personal value is usually measured through one’s capacity for wealth accumulation, it comes to stand in for people’s worth. Related inequities then influence how people feel about themselves and how they relate to each other (Gilligan Citation2000; Bourdieu Citation2002a; Wilkinson and Pickett Citation2010). We have argued these class tensions act in complex ways to constrain individual capabilities, disrupt societal recognition, and perpetuate violence.

A major finding was that fear of violence corrodes the capacity for affiliation, leading to social isolation. We argue that this fear underpins a cluster of corrosive disadvantage (Wolff and de-Shalit Citation2013), which reflects and reinforces structural inequities (Gilligan Citation2000). The dramatic impacts of violence on relations of mutual recognition in poor neighborhoods in Manaus resonates with research showing how these clusters of disadvantage can strengthen discriminatory processes and erode social trust and cohesion (Caldeira Citation2000). Speaking to a global-development discourse, our findings provide empirical support for claims that increases in monetary income do not change oppressive structures (Sen Citation1999; Wolff and de-Shalit Citation2013). Instead, we show that manauaras have responded to growing threats to bodily integrity by severely restricting their movements and social interactions in a bid to preserve even a minimal sense of security. These precautions are costly, causing the sensation for many of “living in a prison.” Accordingly, our article builds on work in Latin America showing that the fear of violence severely restricts life and living, reducing the poor’s capacity for agency and to affect change in their own reality (Koonings and Krujit Citation2007; Kerstenetzky and Santos Citation2009).

Efforts to resuscitate the social life of more deprived neighborhoods in Manaus could confer multiple benefits for individual capacities to be and do. Achieving this is nontrivial, given that many manauaras now perceive social interactions as risks instead of empowering. Evidently, the real and perceived risks of violence impinge on the capacity of individuals to control their destinies (Hojman and Miranda Citation2018). Our field interviews repeatedly demonstrated how violence shapes everyday decisions in Manaus. To avoid danger and preserve bodily integrity, manauaras are often compelled to change their daily conduct—and deepen their disadvantage—by quitting jobs, avoiding leisure activities, and withdrawing from neighborhood social life.

We believe that our theoretically informed study significantly advances current scholarship on Manaus. However, more research is needed into the lived experiences of violence in other disadvantaged, understudied urban contexts in Brazil (Garmany Citation2011). We are encouraged by the growing body of research on violence in Amazonian metropolises, which is predominantly healthcentric and addresses violence against women (see Santos Citation2011) and the rise of drug dealing and its relationship with public security (Riccio et al. Citation2016). Nevertheless, related social science scholarship in Amazonia is scant. This is problematic because designing fair and effective policies to reduce violence requires an understanding of its complex contextual and social causes.

In conclusion, by analyzing the well-being of Amazonian urban working-class citizens using the CA and the notion of corrosive disadvantage, we have shown how threats of violence are corrosive and compose a cluster of disadvantage by profoundly impacting central capabilities, including emotions, bodily integrity, and affiliation. In , we show how this cluster of disadvantage reflects deep social inequities in Manaus, impinges on individual freedoms, and perpetuates the uneven distribution of rights and resources. The fear of violence constrains free, safe movement and limits the abilities of manauaras to enjoy recreational time, be employed, educated, and participate in social life. The novel contribution of our paper is advancing understanding of the social basis and impacts of violence through a nuanced understanding of well-being that accounts for individual capacities and political-economic structures. In understanding the causes and consequences of the violence occurring in Latin American metropolises, we emphasize the importance of considering how disadvantaged people feel about themselves, relate to others, and are able to decide how to conduct their daily lives. We found that the omnipresent threat of violence in a poor neighborhood in Manaus reinforces widespread views that violence and criminality mainly result from character flaws. Logically, then, forceful punishment and state violence becomes one of the only apparent solutions (Caldeira Citation2000; Gilligan Citation2000; Holston Citation2008). This may help explain the election of Jair Bolsonaro as Brazil’s president, whose 2018 campaign agenda sidestepped human rights and poverty alleviation, and pledged increased punishment and unrestrained police force against criminals, and public freedoms to carry guns. Bolsonaro was elected by 55 percent of the Brazilian voters, including 66 percent of manauaras eligible to vote (G1 AM Citation2018). During Bolsonaro’s presidency, state-sanctioned violence against marginalized social groups in Brazil has increased. Combined with infamous failures of governance in Manaus during the covid-19 pandemic, violence in all its forms continues to the erode the vital capacities of disadvantaged people in this rainforest metropolis.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Borges, J. C. 2012. Trabalho, Violência e Sofrimento: Estudo com Cobradoras de Transporte Coletivo Urbana de Manaus/Amazonas. Masters diss., Universidade Federal do Amazonas.

- Bourdieu, P. 1989. Social Space and Symbolic Power. Sociological Theory 7 (1): 14. doi:10.2307/202060

- ———. 2002a. Distinction—A Social Critique of the Judgement of a Taste. 8th ed. London: Routledge.

- ———. 2002b. Language and Symbolic Power. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Brondízio, E. S., A. C. B. de Lima, S. Schramski, and C. Adams. 2016. Social and Health Dimensions of Climate Change in the Amazon. Annals of Human Biology 43 (4): 405–414. doi:10.1080/03014460.2016.1193222

- Caldeira, T. P. R. 2000. City of Walls: Crime, Segregation and Citizenship in São Paulo. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- ———. 2002. The Paradox of Police Violence in Democratic Brazil. Ethnography 3 (3): 235–263. doi:10.1177/146613802401092742

- Caldeira, T. P. R., and J. Holston. 1999. Democracy and Violence in Brazil. Comparative Studies in Society and History 41 (4): 691–729. doi:10.1017/S0010417599003102

- Cañizares-Esguerra, J. 2009. Demons, Stars and the Imagination: The Early Modern Body in the Tropics. In Racism in Western Civilisation before 1700, edited by B. Issac, M. Eliav-Feldon, and Y. Ziegler, 313–325. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press.

- Castro, E. 2009. Cidades Na Floresta. Belém, Brazil: Annablume.

- Cavalcanti, M. 2006. Tiroteios, Legibilidade e Espaço Urbano: Notas Etnográficas de Uma Favela Carioca. Dilemas: 35–59.

- Cavalcanti, R. P., and J. Garmany. 2020. The Politics of Crime and Militarised Policing in Brazil. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy 9 (2): 102–118. doi:10.5204/ijcjsd.v9i2.1157

- Cerqueira, D., R. S. Lima, S. Bueno, P. P. Alves, M. Reis, O. Cypriano, and K. Amstrong. 2019. Atlas da Violência: Retrato dos Municípios Brasileiros. Rio de Janeiro: IPEA.

- Cerqueira, D., R. S. Lima, S. Bueno, C. Neme, H. Ferreira, D. Coelho, P. P. Alves, and others. 2018. Atlas da Violência 2018. Rio de Janeiro: IPEA.

- Claassen, R. 2016. An Agency-Based Capability Theory of Justice. European Journal of Philosophy 25 (4): 1279–1304. doi:10.1111/ejop.12195

- Comaroff, J., and J. L. Comaroff. 2006. Law and Disorder in the Postcolony. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Comiling, K. S., and R. J. M. O. Sanchez. 2014. A Postcolonial Critique of Amartya Sen’s Capability Framework. Perspectives in the Arts and Humanities Asia 4 (1): 1–26. doi:10.13185/AP2014.04101

- Costa, A. T. M. 2011. Police Brutality in Brazil: Authoritarian Legacy or Institutional Weakness? Latin American Perspectives 38 (5): 19–32. doi:10.1177/0094582X10391631

- CRISP. 2012. Datafolha; Ministério da Justiça. Pesquisa Nacional de Vitimização. Results from December 2012. [http://www.crisp.ufmg.br/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/Relat%C3%B3rio-PNV-Senasp_final.pdf].

- Crocker, D. 2008. Ethics of Global Development—Agency, Capability, and Deliberative Democracy. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press.

- Deneulin, S., and L. Shahani, eds 2009. An Introduction to the Human Development and Capability Approach - Freedom and Agency. London: Earthscan.

- Desmond, M., and B. Western. 2018. Poverty in America: New Directions and Debates. Annual Review of Sociology 44 (1): 305–318. doi:10.1146/annurev-soc-060116-053411

- Dodd, L. M. M. 2020. Aspiring to a Good Life: Rural–Urban Mobility and Young People’s Desires in the Brazilian Amazon. The Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Anthropology 25 (2): 283–300. doi:10.1111/jlca.12478

- Drugowick, P., and P. Pereda. 2019. Crime and Economic Growth: A Case Study of Manaus, Brazil. Department of Economics (FEA) Working Paper. São Paulo, Brazil: University of São Paulo.

- Equipe Diário do Amazonas. 2016. Em Dois Meses, Manaus Teve Mais de 10 Mil Roubos, Furtos e Mortes em Assaltos. Diário do Amazonas. [http://d24am.com/noticias/emdoismesesmanaustevemaisde10milroubosfurtosemortesemassaltos/].

- Farias, J. 2007. Quando a Exceção Vira Regra: Os Favelados Como População ‘Matável’ e Sua Luta Por Sobrevivência. Teoria & Sociedade 15 (2): 138–171.

- Farmer, P. 2004. An Anthropology of Structural Violence 1. Current Anthropology 45 (3): 305–325. doi:10.1086/382250

- Ferreira, M. T. 2015. Ensaios da Compaixão: Sofrimento, Engajamento e Cuidados Nas Margens da Cidade. PhD diss., Universidade de São Paulo.

- G1 AM. 2018. Veja Como Foi a Distribuição de Votos de Bolsonaro e Haddad no Amazonas. G1. Rio de Janeiro: Globo.

- Gangas, S. 2016. From Agency to Capabilities: Sen and Sociological Theory. A Sketch for A New Research Program in Sociology. The Capabilities Approach and the Action Frame of Reference. Current Sociology 64 (1): 22–40. doi:10.1177/0011392115602521

- Garmany, J. 2011. Situating Fortaleza: Urban Space and Uneven Development in Northeastern Brazil. Cities 28 (1): 45–52. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2010.08.004

- ———. 2014. Space for the State? Police, Violence, and Urban Poverty in Brazil. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 104 (6): 1239–1255. doi:10.1080/00045608.2014.944456

- Gavirati, V. 2018. AM é o 2o Estado Com Maior Proporção de Presos Provisórios no Brasil, Aponta CNJ. Acrítica [https://www.acritica.com/channels/cotidiano/news/am-e-o-2-estado-com-maior-proporcao-de-presos-provisorios-no-brasil-aponta-cnj].

- Gilligan, J. 2000. Violence: Reflections on Our Deadliest Epidemic. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Globo, A. O. 2020. Projeto no Senado Quer Abolir Marcação de Munições da Polícia. Rio de Janeiro: Exame.

- Harvey, D. 2016. The Ways of the World. The Geography of Capitalist Accumulation. London: Profile Books.

- Hojman, D. A., and Á. Miranda. 2018. Agency, Human Dignity, and Subjective Well-Being. World Development 101: 1–15. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.07.029

- Holston, J. 2008. Insurgent Citizenship: Disjunctions of Democracy and Modernity in Brazil. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

- Homero, V. 2006. Pesquisa Diz Que Favelados São Os Mais Preocupados Com a Violência. [http://www.faperj.br/?id=839.2.6].

- Honneth, A. 1995. The Struggle for Recognition: The Moral Grammar of Social Conflicts. Philosophy and Theology. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

- IBGE [Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística]. 2016. Banco de Dados Cidades.

- Kerstenetzky, C. L., and L. Santos. 2009. Poverty as Deprivation of Freedom: The Case of Vidigal Shantytown in Rio De Janeiro. Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 10 (2): 189–211. doi:10.1080/19452820902940893

- Koonings, K., and D. Krujit. 2007. Fractured Cities—Social Exclusion, Urban Violence & Contested Spaces in Latin America. London: Zed Books.

- Lawler, S. 2011. Symbolic Violence. In Encylopedia of Consumer Culture, edited by D. Southerton, vol. 1, pp. 1423-1424. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: SAGE Publications. [http://sk.sagepub.com/reference/consumerculture/n534.xml].

- Macdonald, T., and A. M. G. A. Winklerprins. 2014. Searching for a Better Life: Peri-Urban Migration in Western Para State, Brazil. Geographical Review 104 (3): 294–309. doi:10.1111/j.1931-0846.2014.12027.x

- Machado, L. O. 2001. The Eastern Amazon Basin and the Coca-Cocaine Complex. International Social Science Journal 53 (169): 387–395. doi:10.1111/1468-2451.00326

- Marmot, M. 2004. The Status Syndrome. New York: Henry Holt.

- MJSP [Ministério da Justiça e Segurança Pública]. 2016. Há 726.712 Pessoas Presas No Brasil. Brasília: Governo Federal. [https://www.justica.gov.br/news/ha-726-712-pessoas-presas-no-brasil].

- Nascimento, A. G. D. O. 2013. Diagnóstico da Criminalidade 2012: Estado do Amazonas. Manaus: Secretaria de Estado de Segurança Pública.

- Nussbaum, M. C. 2013. Creating Capabilities—The Human Development Approach. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

- Oliveira, M. R. D., and A. C. B. Rocha. 2014. A Eficácia das Políticas Públicas de Segurança na Região Metropolitana da Cidade de Manaus. FACEF Pesquisa: Desenvolvimento e Gestão 17: 273–285.

- Orellana, J. D. Y., G. M. da Cunha, B. C. D. S. Brito, and B. L. Horta. 2017. Fatores Associados Ao Homicídio em Manaus, Amazonas, 2014. Epidemiologia e Serviços de Saúde 26 (4): 735–746. doi:10.5123/S1679-49742017000400006

- Paes-Machado, E., and C. V. Noronha. 2002. Policing the Brazilian Poor: Resistance to and Acceptance of Police Brutality in Urban Popular Classes (Salvador, Brazil). International Criminal Justice Review 12 (1): 53–76. doi:10.1177/105756770201200103

- PNUD [Programa das Nações Unidas para o desenvolvimento]. 2014. Relatório do Desenvolvimento Humano 2014. Washington, D.C.: United Nations.

- Queiroz, J. 2019. Medo Toma Conta de População do Bairro São Jorge Após Confrontos e Mortes. Acritica [https://www.acritica.com/channels/manaus/news/medo-toma-conta-de-populacao-do-bairro-sao-jorge-apos-confrontos-e-mortes].

- Ribeiro, L. M. L. 2013. A Democracia Disjuntiva No Contexto Brasileiro: Algumas Considerações a Partir Do Trabalho das Delegacias de Polícia. Revista Brasileira de Ciência Política 11 (11): 193–227. doi:10.1590/S0103-33522013000200008

- Riccio, V., P. Fraga, A. Zogahib, and M. Aufiero. 2016. Crime and Insecurity in Amazonas: Citizens and Officers’ Views. Journal of Emergent Socio-Legal Studies 8 (1): 35–50.

- Salomon, F., and S. Schwartz. 1999. The Cambridge History of the Native Peoples of the Americas—South America. Vol. 3. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press.

- Santos, J. T. D. 2011. Violência Contra a Mulher Nos Espaços Urbanos da Cidade de Manaus (AM): Dois Anos Antes e Dois Anos Depois da Lei Maria da Penha. Masters diss., Universidade de São Paulo.

- Santos, T. V. D. 2017. Metropolização e Diferenciações Regionais: Estruturas Intraurbanas e Dinâmicas Metropolitanas em Belém e Manaus. Cadernos Metrópole 19 (40): 865–890. doi:10.1590/2236-9996.2017-4008

- Sayer, A. 2014. Contributive Justice, Class Divisions and the Capabilities Approach. In Critical Social Policy and the Capability Approach, edited by H. U. Otto and H. Ziegler, 179–189. Opladen, Germany: Barbara Budrich.

- Schor, T., R. R. Marinho, D. P. Costa, and J. A. Oliveira. 2014. Cities, Rivers and Urban Networks in the Brazilian Amazon. Geographical Journal: Geosciences and Humanities Research Medium 5 (1): 254–276.

- Secretaria-Geral da Presidência da República e Secretaria Nacional de Juventude. 2015. Mapa do Encarceramento: Os Jovens do Brasil. Brasília: Presidência da República.

- Sen, A. 1999. Development as Freedom. Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press.

- Senado Notícias. 2019. Pacote Anticrime Recebe Críticas de Especialistas em Audiência Na CCJ. Brasília: Senado Notícias.

- Seráfico, J., and M. Seráfico. 2005. A Zona Franca de Manaus e O Capitalismo No Brasil. Estudos Avançados 19 (54): 99–113. doi:10.1590/S0103-40142005000200006

- Velasco, C., F. Grandin, G. Cesar, and T. Reis. 2020. Número de Pessoas Mortas Pela Polícia Cresce No Brasil No Primeiro Semestre em Plena Pandemia; Assassinatos de Policiais Também Sobem. G1. [https://g1.globo.com/monitor-da-violencia/noticia/2020/09/03/no-de-pessoas-mortas-pela-policia-cresce-no-brasil-no-1o-semestre-em-plena-pandemia-assassinatos-de-policiais-tambem-sobem.ghtml].

- Wacquant, L. 2008. The Militarization of Urban Marginality: Lessons from the Brazilian Metropolis. International Political Sociology 2 (1): 56–74. doi:10.1111/j.1749-5687.2008.00037.x

- Wilkinson, R., and K. Pickett. 2010. The Spirit Level: Why Equality Is Better for Everyone. London: Penguin Books.

- Wolff, J., and A. de-Shalit. 2013. Disadvantage. Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press.

- Wratten, E. 1995. Conceptualizing Urban Poverty. Environment & Urbanization 7 (1): 11–38. doi:10.1177/095624789500700118