ABSTRACT

This paper attempts to understand the origin of the traditional Korean Ch’ŏnhado map by comparing and critiquing previous scholarship on the map’s origins and by explaining the map’s origins through a geomentality lens. Scholars have argued whether Ch’ŏnhado was to embrace the geographical information from Western nations, a Korean interpretation of this information, or an expression of anti-Western sentiment. This paper argues that: (1) Ch’ŏnhado’s design is evidence that it was likely designed by an educated Korean intellectual in Confucian classics (sŏnbi); (2) it is not a Korean-style interpretation of a Western map and was not designed to embrace new geographical information gained from Western nations; and (3) although the oldest remaining copy of Ch’ŏnhado only dates back to the seventeenth century, the map may have originated much earlier. This research provides evidence to support the argument that Ch’ŏnhado was independently developed by Koreans to reflect traditional Korean ways of understanding of the world.

World maps cannot be entirely accurate as it is physically impossible to represent the surface of a sphere on a flat plane (Whitfield Citation1994, 134). Map designers must inevitably make choices that will distort the world’s surface in some way, such as making land closer to the Poles appear larger than they are (Haynes Citation1981, 35–36). How map designers make these decisions is ultimately up to the purpose and audience of the map itself. While people often believe that map information is unbiased and objective, maps are projections of human ideas about landscapes.

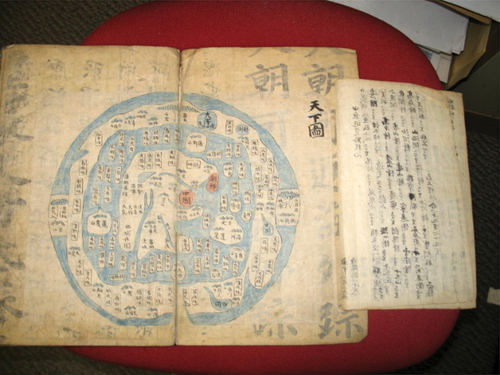

Ch’ŏnhado (天下圖 Map of the World) is probably one of the best known traditional Korean maps. A renowned historian of Korean cartography, Gari Ledyard (Citation1994, 256) pointed out that the foreigners who visited Seoul bookstores in the traditional times, say, early twentieth century were attracted to this traditional Korean map of the world, because it was exotic and curious, and that they have not seen anything like it in China or Japan. The map was likely very popular in Korean society and despite the introduction of more geographically accurate Western maps, the Ch’ŏnhado remained widely used among Koreans.

Ch’ŏnhado () included in the Atlas of the World Maps (Ch’ŏnhachido) () is based on a commonsensical and widely circulating folkloristic Korean interpretation of the world, known as geomentality. Geomentality is an established and lasting frame (state) of mind regarding the geographical environment. It is unique to certain cultural traditions and is reflected in a style of organizing maps, placenames, or in a pattern of the cultural landscape in a particular culture (Yoon Citation1991, 388). Ch’ŏnhado reflects traditional Korean folk attitudes toward foreign and strange land: the map is drawn using traditional folk cartographical skills available in Korea. In this paper, I refer to folk cartography as the unidentifiable authorship of a tradition (maps, knowledge, or stories) that have been transmitted through generations.

My book, Maori Mind, Maori Land (Citation1986) included a brief comparison of Ch’ŏnhado from Korea with the Hereford Mappa Mundi from Britain (). The reason for comparing these two maps here again is to look at them more comprehensively. These two world maps represent the two different traditional geomentalities from East Asia and Western Europe. By comparing and contrasting the geomentality in these two old maps, we can highlight how Korean (East Asian) and British (Western) perspectives differed. Hereford Mappa Mundi (hereafter the Hereford map) is an old British “T and O” map (also known as T-O map, or Ishidoran map) dating from the late-Medieval period in Northern England. It is a large map (133 cm × 158 cm) drawn on a sheet of vellum.

Fig. 3. Hereford mappa Mundi, a medieval T and O type map dating c. 1300, displayed at Hereford Cathedral, England.

Both Ch’ŏnhado and the Hereford map portray the world from a specific point of view. Hereford map has Jerusalem as the center of the world because Britain was a Christian nation, while Ch’ŏnhado has China as the center of the world because Korea was a Confucian state that believed that China was the center of the world. Maori mind, Maori land, contains a comparison of Ch’ŏnhado and Hereford map (Yoon Citation1986, 41–42):

The Western European geomentality in Hereford Mappa Mundi: Represents the Western (Christian) worldview. Jerusalem is located in the center of the world, the Paradise appearing at the top. The North is to the left of Jerusalem; South to the right; West, to the bottom of the map; East to the top. The Ganges River flows to the Easternmost landmass, while the British Isles appear to the northwestern most limits. Neither China nor Korea are indicated.

The East Asian Geomentality in Ch’ŏnhado: Represents the Chinese (Confucian) worldview. China, “the Middle Kingdom” is placed in the center of the world continent, surrounded by the world ocean. The Chinese characters for China on the approximate location of Beijing. To the East of China, there appear the Korean Peninsula, the Island of Japan, and the Island of Ryukyu (Okinawa); to the Southeast, Vietnam; to the Southwest, India. The names such as Land of One-eyed, or that of immortals—are given throughout the world ocean and its surrounding landmass. Neither Europe nor Jerusalem is indicated.

The quote above indicates that both maps are designed with a designated center and that the worldviews or geomentalities that they represent are rather different. People tend to locate the most important and significant place in the center of a map in circle. Thus, the Hereford map represents the Jerusalem centered Christian geomentality, while Ch’ŏnhado, the China centered Confucian one.

Although the early researchers of Ch’ŏnhado were unsure whether this map was from Korea or China, present-day researchers in Korea tend to consider this map was probably of Korean origin and produced in Korea. Lee Chan (Citation1976, 58, and 66) thought that Ch’ŏnhado had probably gradually evolved in Korea as a world map with the idea of China as the center of the world. Other Korean scholars such as Oh Sanghak (Citation2001) and Bae Woo-sung (Citation2000.) also implied that the map is likely of Korean origin. This issue will be discussed more in detail in a later section of this paper.

As of now the author of Ch’ŏnhado is still unknown, although the map is found only in Korea. Until recently the researchers of Ch’ŏnhado mainly focused on identifying the characteristics of the map, rather than the author of the map. This paper attempts to understand who might have authored this map. The aim of this paper is to argue that Ch’ŏnhado is designed and drawn by an educated traditional Korean scholar (sŏnbi). I support my argument by analyzing the map and the later Chosŏn dynasty. Before this, I review existing research on Ch’ŏnhado and critique existing arguments in the literature.

A Review of Previous Research on Ch’ŏnhado

Research on Ch’ŏnhado ranges from the initial encounters of Ch’ŏnhado by American Protestant missionaries toward the end of nineteenth century to a contemporary scene of researchers who argue that Ch’ŏnhado was influenced by Western maps.

Initial Understanding of Ch’ŏnhado by Missionaries

Homer B. Hulbert (1863–1949) was one of the first American Protestant missionaries to the Korean Kingdom in 1886. Hulbert established the first state-run modern school in Korea and became an ardent supporter of Korean independence. He loved studying Korean things including its history, geography, Korean alphabets, and Korean customs in general. It was probably under a missionary’s auspices that a Korean by name, Yi Ik Seup (이익습, 李益習) first introduced Ch’ŏnhado in English to the Christian missionaries in a brief essay. He published “A Map of the World” in 1892 in The Korean Repository, a monthly journal published by North American Protestant missionaries on Korea and Korean missions. Yi Ik Seup believed that the information in the world map was accurate: he argued, “ … so the map goes on to the ‘feathered’ kingdom where the ostriches live, … and many others to the number of nearly one hundred, all of which I have no doubt will be found correct if deeply searched into” (Yi Ik Seup Citation1892, 339).

Yi’s essay introduces Ch’ŏnhado as an ancient Korean map with 63 placenames in it. In Yi’s essay, the placenames are presented in Chinese characters first and followed by an English translation. For example, the essay stated; 一目(國) one eyed (nation), 三首(國) three headed (nation), 食米 rice eaters, 不死 immortals, while providing no notes on how to read (pronounce) those Chinese characters. The meaning of these strange folkloristic names of imaginary nations are translated into English, but there is no literal pronunciation of the Chinese characters in Korean for those placenames, such as Ilmok 一目for one eyed, samsu 三首 for the three head (persons), sikmi 食米 for rice eaters, or pulsa 不死for immortals.

Homer Hulbert then published an article introducing Ch’ŏnhado with title “An Ancient Map of the World” in Bulletin of the American Geographical Society of New York in 1904. His paper was much more substantial than Yi Ik Seup’s and was printed in a proper academic journal of geography. His article also translated the literal meanings of all placenames on the map into English, although he did not give either the Korean pronunciation of those place name or the Chinese characters of them. It is not clear why he did not include the Korean pronunciation of those placenames, but it may have been linked to a lack of clarity concerning the ethnic origin (whether a Chinese or a Korean) of the author of the map. Hulbert is unlikely to have known whether the author of the map was Korean or Chinese, even though the map was only found in Korea. Hulbert considered the map to be low value for obtaining geographical knowledge, but recognized its value as rich resource for folklore when he said (Hulbert Citation1904, 602):

But, seriously, it is impossible to verify more than a few of the places on this map. From a genuinely geographical standpoint it is worthless, but to the student of folk-lore it opens a wide field of study. All these places and peoples are mentioned in one place or another in Chinese and Korean literature—At any rate, this map should be preserved for purposes of reference when the great subject of Chinese lore is thoroughly opened up.

The above quotation hints that Hulbert may have believed that the map originated from China, as he suggested that the map should be preserved until “Chinese lore is thoroughly opened up.” This raises questions of why he suggested that Ch’ŏnhado should be preserved for the study of Chinese lore rather than for Korean lore and why he mentioned Chinese literature before Korean literature unless he believed that Ch’ŏnhado was a Chinese product and using Chinese references. Considering that the center of the world map was China, and all words (placenames) were written with Chinese characters, it is understandable why Hulbert might have thought that the Ch’ŏnhado originated from China rather than from Korea.

More Recent Comments on and Study of Ch’ŏnhado

The first appearance of the Ch’ŏnhado in an English geography textbook was probably in Land of the 500 Million: A Geography of China, by George B. Cressey in 1955. He included a copy of the Ch’ŏnhado map as an illustration with the caption, “All the world under heaven.” He argued that the characters for China appear in the center of the world island, as befitting the location of the “Middle Kingdom” (Cressey Citation1955, 26). Cressey labeled the inner continent in the Ch’ŏnhado map as the world island, probably because it was surrounded by the (world) ocean. He referenced Hulbert’s work but did not mention that Hulbert was an American Protestant missionary to Korea, not to China and he acquired the map in Korea, not in China thus leaving readers to assume that the map was Chinese in origin.

There are three noteworthy works that precede recent research suggesting the influence of Western maps on Ch’onhado: Kim Yangsŏn (Citation1972)and Lee Chan (Citation1976.) published an important article each on Ch’ŏnhado in Korean; Gary Ledyard (Citation1994) in his essay on “Cartography in Korea,” carried out the first substantial and original discussion on Ch’ŏnhado in English. The main points of these papers are as followed:

Kim Yangsŏn (1908–1970) was a collector of old maps and historical geographical literature of Korea. He produced an article on old Korean maps (Kim Yangsŏn (Citation1967) 1972, 216) in which he argued that the map design of Ch’ŏnhado probably derived from the ancient Chinese Yin-Yang School philosopher Zou Yan 鄒衍 (305 BC–240 BC) who thought that China was encircled by the sea. Kim Yangsŏn (Citation1972, 218) postulated that Zou Yan’s idea was introduced in Korea during the Koryŏ dynasty (918–1392), which implied that the origin of Ch’ŏnhado can be traced back to the time of the dynasty (Yoon Citation2022, 171).

Lee Chan (Citation1976, 58) argued that Ch’ŏnhado is probably the result of a gradual evolution through a long period of the time and is a Korean drawn map that adopted a Chinese worldview. Lee’s paper is an early substantial research work among the six important pieces of recent literature. Lee’s descriptive but informative paper examined two old world maps of Korea—Ch’ŏnhado and Honil kangni yŏktae kukdo chi do (混壹疆理歷代國都之圖, Map of integrated regions of historical states and capitals)—the latter being the earliest known Korean world map, dating back to 1402. Lee’s 1976 paper introduced several scholars’ comments on the origins and development of these two old Korean world maps.

Gari Ledyard (Citation1994, 256–266) argued that the Ch’ŏnhado evolved from the Honil kangni yŏktae kukto chi to (Map of Integrated Regions of Historical States and Capitals, abridged as Kangnido), the first known Korean map of the world (1402). He (1994, 266) hypothesized that the outline of the Ch’ŏnhado’s inner continent might have evolved from Kangnido. Three different copies of the Kangnido map survive in Japan, but none in Korea. Ledyard suggested that the copy stored in Tenri University in Japan might be most plausible candidate for being the basis of the Ch’ŏnhado (Ledyard Citation1994, 265). The reasons for this are based on “two principal clues” from the land features in Ch’ŏnhado: “the triangular peninsula on the inner part of the western half of the continent,” which could be an imaginative transformation of the Arabian Peninsula, and “the large body of water just to the northwest of this peninsula”—transformed body of the Mediterranean and the Black seas” (Ledyard Citation1994, 266). The following diagram () illustrates his hypothesis on the evolutionary stages of the Ch’ŏnhado’s inner continent from Kangnido (Ledyard Citation1994, 265).

Fig. 4. Gari Ledyard’s hypothetical evolutionary process from the Kangnido to Ch’ŏnhado. The upper two sketch maps compare the coastal outlines of the Kangnido and the inner continent of Ch’ŏnhado. The bottom sketches show the suggested sequential evolutionary stages. (Ledyard Citation1994, 265). Used by permission of the University of Chicago press © 1994 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved.

Ledyard (Citation1994, 266) acknowledged that “The suggested evolution from the Kangnido’s outer continental coastline is concededly arbitrary, dictated by a ‘known’ target outline.” However, he thought that the shapes of the Kangnido’s Mediterranean/Black, Red, and Arabian seas and the Arabian Peninsula are significant enough to conjecture their evolution into their Ch’ŏnhado counterparts. Once the shape of inner continent is created, Ledyard thought that some “clever spirit” (assuming he meant “the map designer”) would have engrossed it with the placenames (fantasies) of the Shanhai-jing.

While Ledyard’s hypothesis lacks the concrete evidence to support his hypothesis, it is a theory worthwhile for further consideration.

Arguments That Western Maps Influenced Ch’Ŏnhado

Two important recent works on Ch’ŏnhado are articles by Oh Sanghak (Citation2001) and Bae Woo-sung (Citation2000.). Oh Sanghak suggested that the map was an attempt to accommodate newly introduced geographical ideas from the West, while Bae Woo-sung argued that it was a Korean style interpretation of a world map from the West. In addition to these two articles, Japanese scholar Unno Kazutaka (Citation1981) raised an important issue relating to the development of the Ch’ŏnhado map. He argued that the map was born out of Koreans’ anti-Western feeling as well as borrowing “a circle frame around the map” from the West. Following is a discussion one by one in greater detail of the three academic discourse on the nature of Ch’ŏnhado.

Oh Sanghak (Citation2001, 231) argued that the Ch’ŏnhado was developed to accommodate new geographical knowledge introduced from Western Europe in the seventeenth century, because the design of the map is remarkably different from traditional Korean maps. I, however, do not agree with this view because the traditional Ch’ŏnhado map does not clearly display influence from Western geographical knowledge in terms of placenames or the shapes of prominent landmass. Considering the social environment of the later Chosŏn dynasty, Oh Sanghak agreed with Bae Woo-sung and Unno Kazutaka’s view that Ch’ŏnhado was influenced by the introduction of Western culture in Korea. He at least partially contradicted his argument, when he acknowledged that the traditional Ch’ŏnhado is a totally different map from a Western style world map in terms of its contents including map design, and he declared that it is difficult to find any similarities between Ch’ŏnhado and a Western-style world map (Oh Sanghak Citation2001, 235). All three researchers (Oh Sanghak, Bae Woo-sung, Unno Kazutaka) of Ch’ŏnhado accepted that most placenames appeared in the map were from Shanhai-jing, or Classic of Mountains and Seas (山海經: Sanhae kyŏng in Korean).Footnote1

Bae Woo-sung is a well-known Korean historian who published several articles on traditional Korean maps and traditional geographical thought of Korea. Bae Woo-sung (Citation2000, 76) thought that the introduction of Western European culture and the production of Western style maps provided the momentum for the birth of Ch’ŏnhado. He goes on to argue that Korean intellectuals who were influenced by Western culture then interpreted Western world maps using traditional Korean perspectives.

Both Bae Woo-sung (Citation2000, 78) and Oh Sanghak (Citation2001, 235) argue that because Ch’ŏnhado was the first known Korean map with a circular frame, it must have been influenced by Western maps: without dramatic changes in Korean culture thanks to the new Western cultural influence, it would have been impossible to put the map of the world into a circular frame, because no Korean maps were treated so ever before. Their arguments seem logical and plausible. However, Bae Woo-sung’s (Citation2000, 78) arguments especially are seemingly driven by his wish to support his hypothesis of Ch’ŏnhado as a Korean style interpretation of the European world map, but he provides no evidence for the maps that may have influenced Ch’ŏnhado. If Ch’ŏnhado is a Korean interpretation of a Western European world map, he should have pointed out what aspects of which Western map were interpreted by Korean(s) in a Korean way. If Ch’ŏnhado is indeed a Korean interpretation of a European world map, the map should show at least the names of Africa and Europe in Ch’ŏnhado as well as the landmasses that resemble Africa and Europe, for they are prominently featured in Mateo Ricci’s world map, Kunyu Wanguo Quantu (坤輿萬國全圖 Complete Map of All Nations on the Earth, Konyŏmankukchŏndo in Korean) and other European drawn world map from the time.

Although the inner continent of Ch’ŏnhado mostly includes the real placenames that have been in use, it does not include any Western placenames from Mateo Ricci’s Kunyu Wanguo Quantu or any other Western made world maps. The Western made world maps exhibit realistic land shapes comparable to a modern map, while Ch’ŏnhado is a simplistic sketch. If Ch’ŏnhado is an interpreted version of the Western world map, one can expect that the interpreted version would somehow reveal aspects of the original map and be more advanced and more accurate than the original Western map. However, those who read Ch’ŏnhado will quickly realize that it is not an improved or more advanced version than the Western map, but a totally different kind of map with an extremely crude and a childlike whimsical drawing of the world retain no evidence of having referenced the Western map. It shows no relationship to the Western world map. This reality suggests that Ch’ŏnhado is not a Korean’s interpreted version of a world map from Europe.

The Korean Peninsula in the inner continent of Ch’ŏnhado is somewhat exaggerated in size, compared to other parts in the world map. The shape and location of the peninsula are more accurate than any other place, and the eastern coastlines of China are also relatively accurate. This fact may suggest that the map was drawn by someone who was familiar with Korea and eastern parts of China.

In Ch’ŏnhado, there are no signs representing new geographical knowledge brought in by Catholic missionaries from Western Europe. Instead, all placenames and the arrangement of land in the map are close to the traditional East Asian worldview as represented in Shanhai-jing, or the Classic of Lands and Seas. If Ch’ŏnhado was influenced by Western culture (world maps from the West), there should be similarities with the Western world map in terms of placenames or land shapes, but there are hardly any similarities between the two maps (Oh Sanghak Citation2001, 235).

Although Ch’ŏnhado does not resemble Western maps, Bae Woo-sung argued that the inner sea, inner continent, and circular outer continent are the result of Korean interpretation of Asia, Europe, Africa, and North-South America (Bae Woo-sung Citation2000., 78–79). Bae Woo-sung suggests that Africa, Europe, and Asia are combined and miniaturized as the westernmost part of the inner continent in Ch’ŏnhado, while the outer circular continent (ring) represents the North- and South American continents.

I do not agree with Bae Woo-sung’s argument. In terms of the shape of the land, no parts of inner continent of Ch’ŏnhado are similar to Europe or Africa, and there is no evidence that the imaginary circular outer continent of Ch’ŏnhado is North and South America. The inner- and outer continents in Ch’ŏnhado are much closer to the concentric worldview expressed in Shanhai-jing, or Classic of Mountains and Seas (Oh Sanghak Citation2001, 238), with the inner continent in Ch’ŏnhado focusing on East Asia. The eastern end of the inner continent is the Korean peninsula and Japanese islands, and the western end is the Indian subcontinent, with its further west being ocean. This aspect of land arrangement is similar to the Hereford Mappa Mundi, where Jerusalem is the center of the world, and the eastern end is the Ganges River of India.

It is interesting to note that the traditional worldviews of the East and the West both thought that the Indian subcontinent was the end of their known world. This traditional worldview as represented in Ch’ŏnhado and the Hereford Mappa Mundi may indicate that the West did not know well beyond the east of India and the East did not know well beyond the west of India. Designing Jerusalem as the center of the world in Western minds, and China in Eastern minds, has been a popular theme in traditional geographical thinking in both the West and the East, due to the importance of these locations for Catholicism and Confucianism respectively.

Unno Kazutaka was a Japanese geographer who was a specialist in East Asian cartographical history. He argued that while Ch’ŏnhado’s circular frame came from the circular style of a European world map, the placenames in the map came from Daoism or Daoistic ideas of supernatural beings, and that the map was born out of anti-Western atmosphere in Korea at that time (Unno Kazutaka Citation1981, 32–33). His argument might reflect the fact that soon after the arrival of Catholicism in Korea, it was persecuted by the government. Unno’s ideas attracted much attention from Korean scholars, including Bae Woo-sung (Citation2000.)and Oh Sanghak (Citation2001).

Toward the end of nineteenth century, a socioreligious movement called Tonghak, or Eastern Learning, became influential in Korea. Tonghak was based on traditional Korean belief systems and formed to counter 西學Sŏhak or newly introduced Western learning, namely Catholicism. Considering this Korean experience, Unno Kasutaka’s thesis of anti-Western sentiment as the background for the birth of Ch’ŏnhado is a seemingly logical proposition. However, Ch’ŏnhado may have been made long before the arrival of Catholicism in Korea, as I will discuss later. In addition, the circular map frame may not have been borrowed from Western-style maps as various forms of circles were widely used in Korean art, such as the symbol of taegŭk that is adopted in the Korean national flag.

Other Contemporary Research on the Origin of Ch’ŏnhado

To fully appreciate the placenames and their locations in the inner continent of the Ch’ŏnhado map, some basic knowledge in the art of practicing geomancy (fengshui in Chinese and p’ungsu in Korean) is critically important. In East Asian thought, a widely known idea is that the earth reflects heaven—for example, mountain shapes on earth reflect the corresponding stars in heaven (Hanlong-jing, Kim Dukyu trans. 2009, 37). An influential geomancy classic, Hanlong-jing 撼龍經written by Yang Yi 楊益 (834–900) who is also known as Yang Yunsong 楊筠松, states that auspicious sites on earth correspond to those in heaven. The book was very popular in Korean society during the Chosŏn dynasty (1392–1910), becoming an important examination subject to pass for official geomancers in government geomancy bureaus as it expounded on the conditions of auspicious sites on earth as related to astronomical phenomena.

In Ch’ŏnhado, the sacred Kunlun Mountain is placed in the middle of its inner continent, because it was a common understanding to East Asians that the mountain occupied the center of the world. This is stated in Hanlong-jing, which declared it to be the backbone of the world (Hanlong-jing, 1967 edition, 1). When Bae Woo-sung (Citation2000, 76) argued that the author(s) of Ch’ŏnhado placed the famous Kunlun Mountain in the middle of the map, by taking the idea of placing Asian continent in the Western-style world map published in China by Catholic missionary such as Mateo Ricci, his interpretation failed to consider the age-old East Asian geomantic understanding on what mountain occupies the middle of the world.

Unno Kazutaka’s (Citation1981) suggestion that most placenames in Ch’ŏnhado came from Shanhai-jing was not new, as it was suggested so by the authors of earlier studies, including Lee Chan (Citation1976.) and later by Gary Ledyard (Citation1994), Bae Woo-sung (Citation2000.), and Oh Sanghak (Citation2001). Here, it is much more reasonable to think that the author(s) of Ch’ŏnhado chose those placenames from Shanhai-jing, not because of anti-Western sentiment, but for their own folkloristic curiosity on the unfamiliar part of the world to Koreans—remote and unknown places.

Oh Sanghak (Citation2015, 236) suggests that the edge of Ch’ŏnhado is in fact a representation of heaven that surrounds the earth. It is an ingenious suggestion, but those strange names are more likely to reflect their imagination filled with curiosity about a remote and strange land, rather than heaven. Traditionally, Koreans believed geomantic ideas that the earth reflected heaven (Hanlong-jing, Yang Yi Citation1967, 37), so there was no need to create a separate space for heaven on world maps.

It may be more reasonable to think that the encircling continent filled with strange names expresses Koreans’ curiosity about a remote and strange land that they heard about, rather than the world of stars. As stated in geomancy texts, Koreans traditionally understood that heaven and earth reflect each other, so did not need to create a separate space for heaven in the world map. Those strange names more likely refer to strange creatures and inexplicable customs in strange folktales rather than the conditions of stars that are often considered sacred. I see Ch’ŏnhado as a kind of folk geography map, representing traditional Korean’s curiosity about remote and strange faraway lands of the world.

Of the above six important works that I have reviewed, all four except Kim Yangsŏn and Lee Chan’s early works argued that this map was at least in part the result of Western cultural influence. Three out of six works (Unno, Bae, and Oh) also thought that this map originated from the seventeenth century after the arrival of Western missionaries (Catholic priests) who brought Western maps and new geographical knowledge.

Korean Geomentality as Represented in Ch’ŏnhado: It Is a Korean-designed Folk Cartographical Map

The purpose of this section is to present my argument that the Ch’ŏnhado map was not a result of Western cultural influence, but is an indigenous Korean design and drawing. Early researchers of Ch’ŏnhado such as Homer Hulbert (Citation1904, 602) and Kim Yangsŏn (Citation1972, 216) did not know whether it was of a Korean- or Chinese-designed map. This is understandable as the map placed China at the center of the world and wrote all placenames in Chinese characters only. Most recent researchers in Korea consider that Ch’ŏnhado is of Korean origin, although they do not know for sure who might have designed and drawn the map. On this issue, Lee Chan (Citation1976, 58 and 66) suggests that Ch’ŏnhado that embraced the China-centered worldview was a special map made by Koreans. Bae Woo-sung (Citation2000, 52–79) implied that the map was of Korean origin, when he argued that it was a Korean-style interpretation of the Western world map. Oh Sanghak (Citation2001, 231) assumed that Ch’ŏnhado was created to accommodate new geographical information from the West. Oh afterward (2015, 241) clearly argued that Ch’ŏnhado was special world map made in Korea since seventeenth century,” although he did not document evidence to substantiate his argument.

Korean scholars who implied Ch’ŏnhado is a Korean map did not clearly discuss or present evidence to support their suggestions on who might have designed and drawn the map. In a previous article, I have specifically suggested that a traditionally educated person(s) in Confucian classics (Sŏnbi in Korean) might have designed and drawn the map, because the Korean peninsula on the map is somewhat exaggerated in size and the shape and location of the peninsula are more accurate compared with other regions, such as China, Japan, or any other parts of the world in the map (Yoon Citation2022, 170–172). This treatment of Korea as a special place reflects the Korean geomentality of the affection for one’s homeland in a world map. A foreigner such as a Chinese or a Japanese would not have found any special reason to treat Korea so specially, for it was simply a border land just outside their country.

Ch’ŏnhado is not a map that was produced with government initiatives or for the purposes of governing the nation, such as tax collection or drafting laborers (mobilizing work forces), as there are no records of either the publication of or the use of the map by the government for any official purpose during the Chosŏn dynasty. However, the map was very popularly edited and produced in the forms of hand-copied or woodblock printed editions and circulated them among the Korean literati through private networks. Ch’ŏnhado is a world map showing foreign lands and is filled with curious customs and folklore. That is probably why the inner continent—relatively familiar land with real placenames—is treated simply, while outer areas are filled in detail with strange names representing imaginative inexplicable customs. Folklore is elaborated on with the majority of placenames in the map. That is one reason why I consider Ch’ŏnhado as a map of folkloristic imagination on unfamiliar foreign land.

As I have discussed earlier, the most realistic and accurate part in the world map is the Korean Peninsula, and it is somewhat exaggerated in size compared to other regions. This may suggest that the illustrator of the map knew Korea best for it was his home. Compared to Korea, the lands of China, Vietnam, India, or Japan are drawn much more crudely, inaccurately, and in a simplistic way. This fact may indicate that this map was designed and drawn by a Korean. If a Chinese or a Japanese person drew this map, it would be difficult to explain why Korea is treated with such special care. Only the placenames of China and Korea are colored in red in the manuscript copy of Ch’ŏnhado that I have. This coloring also supports the view that this map was designed and drawn by a Korean(s), for the Koreans traditionally believed that China was the center of the world. The illustrator of the map must have picked China as the center of the world and Korea as their home country to treat specially with an exaggerated size and more accurate shape.

This case is paralleled in the Hereford Mappa Mundi. In the map the British Isles are placed on the western edge of the world at the bottom of the map, but they are treated rather specially with an exaggerated size and are drawn with much more detail than other regions. The love and care for one’s homeland might be a universal phenomenon for people anywhere. The mind-sets (geomentalities) of loving and caring for one’s homeland are similar, which could be why the illustrators of Ch’ŏnhado and Hereford map drew their homelands more in detail and somewhat exaggerated in size compared to other countries.

My View on the Origin of Ch’ŏnhado

1) The circle frame of Ch’ŏnhado was not necessarily a Western European influence

Existing scholarship tends to assert that world maps that originated in Europe influenced the creation of Ch’ŏnhado. It is difficult to agree with this view for the following reasons:

Firstly, some scholars claim the circle around Ch’ŏnhado is the first time a circle was used as a frame in any Korean map. However, as I have discussed earlier, a circle in my view is a universal icon to any people in the world and Korean mapmaker(s) did not need to borrow it from the Western mapmakers.

Secondly, the names of key landform features of an auspicious land (site) are from the names of stars. It is a common sense in geomancy that the land or mountain shapes correspond to the stars in heaven. The East Asian (Korean) concept of Ch’ŏnwŏnchibang 天圓地方 “sky is round while the earth is square” can be interpreted as the sky is like a dome, while the earth is flat. Therefore, a circle is not a strange icon or concept to a Korean, and putting the world in a circle framed map was not necessarily borrowed from Western world maps.

In geomancy it was believed that the mountain forms and locations reflect those conditions of corresponding stars in heaven. A well-known geomancy classic, Geomancy that All People Must Know or Diri renzixuzhi地理人子須知 presented the view that all stars in heaven and mountains on earth correspond each other and are from the five elements (wuhang 五行) in the Chinese Yin-Yang and Five Elements Theory. For instance, the names of five basic mountain types or more complicated types of nine mountains are also all from those of stars. Five mountains names—metal (金), wood (木), water (水), fire (火), earth(土)—came from those of five planets and nine mountain names came from the Big Dipper (北斗七星, Puktuchilsŏng in Korean) and two adjacent stars. If Koreans might have thought that sky was round like a ball, then the earth would be round as well, somewhat flattish round. Heaven and earth are alike and corresponding each other. A circle is readily available symbol for Koreans.

2) Ch’ŏnhado is not a Korean style interpretation of a Western world map

Claiming Ch’ŏnhado is a Korean style interpretation of a Western world map infers that it is something of an offspring of a Western map. As such, any aspects of Ch’ŏnhado should show features from Western world maps, namely the shapes of landmasses or placenames. However, there is no evidence of these in Ch’ŏnhado, except Gari Ledyard’s suggestions in his highly imaginative hypothesis (Ledyard Citation1994, 266). A potential reason for why Ch’ŏnhado’s popularity extended beyond the introduction of Western maps was probably that Koreans felt more comfortable with traditional Korean geomentality or the representation of the world that Ch’ŏnhado presented. In other words, Ch’ŏnhado suited the traditional Korean mindset in organizing the world more so than the newly introduced world map from Europe. Reflecting Korean geomentality, Ch’ŏnhado does not have any placenames or shapes of landmasses that are alike any Western world map from that time period. Oh Sanghak (Citation2001, 235) clearly argued that if Ch’ŏnhado originated from a Western world map, there must be matching aspects between the two maps, but there are no such things in terms of placenames or the shapes of land in the map.

3) Progenitor map of Ch’ŏnhado is NOT a Western world map

Both Ch’ŏnhado from Korea and the Hereford Mappa Mundi adopt a center-periphery framework of the world. The Hereford map has Jerusalem as the center of the world and Ch’ŏnhado has China as center of the world. Ch’ŏnhado is based on the China-centered, concentric worldview of Shanhai-jing, with the outer continents being remote parts of the world that Koreans had heard about.

The inner continent in Ch’ŏnhado included China as its center and included Korea, China, Vietnam, Thailand, and the Indian subcontinent outside it. Oh Sanghak (Citation2001, 239) speculated that it would have been impossible for Koreans to draw this map without a reference, and that the Koreans must have acquired from China a map with China in the map’s center. This is a reasonable conjecture, but I do not agree with his argument. During the Chosŏn dynasty in Korea, the Sŏnbi (learned persons) were systematically trained in Chinese classics and Chinese history and would have had a remarkably high degree of understanding of China as the center of the world. Their readings of readily available popular Chinese literature such as Journey to the West (西遊記, Sŏyugi in Korean) and numerous history books on China would have supported the China centered worldview. They would not have needed to import a Chinese map to draw Ch’ŏnhado with China in the center of the map. The geomentality of the world with China at the center was a common and basic worldview that Chosŏn dynasty learned people (sŏnbi) had. The geographical information in the inner continent of Ch’ŏnhado may be a mere expression of a sŏnbi’s knowledge of the world.

People tend to understand the world from the viewpoint where they live, will usually mark or represent one’s home country in the world map they draw. Moreover, to mark their home in the traditional world map, people sometimes exaggerate the size of their home country. In Ch’ŏnhado, the Korean Peninsula is somewhat exaggerated compared to other regions. While Japan is represented as a single roundish island in the sea, the relative size of the Korean Peninsula is larger than in real life, and its landmass shape is represented relatively accurately. This treatment of the Korean Peninsula in Ch’ŏnhado may well be an indication that a Korean designed this map. This situation parallels the treatment of the British Isles in the Hereford Mappa Mundi, which is exaggerated in size compared to other lands in the map. This special treatment of British Isles may well suggest that the Hereford map is a British map authored by a British cartographer.

4) The birth of Ch’ŏnhado must predate the seventeenth century

Oh Sanghak (Citation2001) and Bae Woo-sung (2020) argue that the seventeenth century is the earliest date that Ch’ŏnhado could have been created. Their claims seem plausible since Western cultural influence arrived in Korea through China at that time. They argue that Western influence facilitated the birth of Ch’ŏnhado, and they claim that their argument is supported by the oldest extant Ch’ŏnhado, which was drawn in the seventeenth century. However, it is possible that some earlier and less developed versions of the map may have existed prior. Ledyard (Citation1994, 265), for instance, suggested that the land shape of the continent with China in it in Honil Kangni yokdae kukdo chi to (混壹疆理歷代國都之圖) of 1402 may show some similarities with Ch’ŏnhado, and Lee Chan (Citation1976., 58) argued that Ch’ŏnhado is the result of the gradual evolution of earlier Korean drawn world maps. However, the suggestions by Ledyard have not been seriously considered by contemporary researchers, because the suggested similarities are extremely imaginative and are not about conspicuous landmasses such as European or African continents that are prominently featured in world maps from the West.

The fact that the fully matured Ch’ŏnhado of the seventeenth century is still extant suggests that the map was created at least during or before the seventeenth century, not produced after the seventeenth century. The seventeenth century here is, as commonly used in relative dating in folklore studies, terminus ante quem (the time before which), not terminus post quem (the time after which). This relative dating method is popularly adopted in setting some time frame on oral folklore items such as legends, folktales, and proverbs, when the exact dates of their origins are impossible to know.

5) No evidence for the influence of Western knowledge

As discussed above, the three main recent researchers of Ch’ŏnhado argued that the map was born out of Western cultural influence. In fact, only small groups of Chosŏn dynasty learned Koreans (sŏnbi) showed interest in Western learning knowledge, namely Catholicism. Interested sŏnbi studied the books written by the Catholic missionaries in China and attempted to practice Catholicism without a properly trained and ordained priest. However, it does not mean that the newly introduced western creed changed the whole of Korean society dramatically. When Catholicism was introduced in Korea, Korean society was still conservative and largely practiced neo-Confucianism. Soon after the introduction of Catholicism, the government started persecuting Catholics. This social atmosphere contributed to the confinement of Catholicism and Western learning to a small sect of Korean society. Western learning slowly and only gradually spread out in Korea only 100–200 years after its arrival.

I do not think that Western knowledge influenced the birth of Ch’ŏnhado. As I have discussed earlier, the fully developed Ch’ŏnhado may well have existed before the seventeenth century in Korea. At the least, an ancestral map related to the fully mature Ch’ŏnhado may have existed before the seventeenth century. If the creation of Ch’ŏnhado can be traced back beyond the seventeenth century, before the arrival of Western learning, then we do not need to discuss the influence of Western culture over Ch’ŏnhado. Almost all orthodox Confucian literati at that time did not know about Catholicism and Western geographical ideas introduced then to Korea. Even if we concede that Ch’ŏnhado was created after the arrival of the Western geographical ideas in seventeenth century, I feel that the person who designed Ch’ŏnhado may be one or some of the mainstream Confucian literati who had not been exposed to the newly introduced Catholicism and new geographical ideas from the West. This conjecture is based on the fact that (1) we cannot find anything that could be a sign of Western influence on the Ch’ŏnhado map and (2) the dissemination process of the newly arrived Western culture was extremely slow during the latter part of the Chosŏn dynasty.

The mainstream Confucian literati in Korea at that time of circa seventeenth century were neo-Confucianists who did not embrace Catholicism or the Western culture. Researchers arguing for the influence of Western geographical ideas on the birth of Ch’ŏnhado may be unconsciously exaggerating the influence of Western geographical ideas in Korea at that time. The fact that Ch’ŏnhado shows no signs of Western influence on the map may suggest that the original designer and illustrator of the map was not influenced by Western geographical ideas, although the map might have been drawn after the arrival of these ideas in Korea.

There is a map called ‘Imadu Ch’ŏnhado (利瑪竇天下圖), which literally means the Ch’ŏnhado (World Map) by Mateo Ricci, a Catholic (a Jesuit) missionary to China from Italy. This map is not a traditional Ch’ŏnhado but is a variant form of the traditional Ch’ŏnhado. In this map the inner continent is a rectangular shape that is very different from the one in traditional Ch’ŏnhado. I wonder whether this variant represents an attempt to combine the traditional Ch’ŏnhado (traditional world map from Korea) and Mateo Ricci’s new geographical ideas from the West.

The author(s) of the traditional Ch’ŏnhado must be a Korean scholar(s) who were probably not exposed to Catholicism or the Western culture. The situation could be comparable to my Korean village life experience. Until the mid-1950s, in my rural home village I had never seen a Western style wedding ceremony with a bride and groom wearing the modern (Western) costumes of a wedding dress and gown. At that time, in cities some people had already adopted Western style wedding ceremonies wearing Western-style wedding costumes. It took decades for the Western style custom to reach my village. Similarly, when Western geographical ideas arrived in Korea, it first was accepted by small groups in limited places before spreading out widely over a long period of time. The traditional Ch’ŏnhado was designed by one or some of the sŏnbi, or learned persons, within the mainstream Confucian literati who were not exposed to Catholicism or Western geographical ideas of the world, as the map simply does not show any Western cultural input in it. The newly introduced Catholicism and geographical ideas from the Western world did not change Korean society suddenly in a dramatic way and it took long time before gradually spreading out Korean society in general.

Conclusion

Both maps of Ch’ŏnhado from Korea and Hereford Mappa Mundi are products of their own cultural tradition and project their own worldviews on lands or geomentality. These two maps are not products of science, but products of their own culture to suit their own cultural needs.

An important aspect of the cultural heritage of Ch’ŏnhado is that the map represents traditional Korean geomentality. While Hereford Mappa Mundi represents traditional Western geomantality, Ch’ŏnhado represents an East Asian (Korean) one. The main points of the discussion in this paper are:

A Korean Confucian literati (sŏnbi in Korean) may have designed and drawn Ch’ŏnhado. The main supporting evidence for this argument is the more accurate and somewhat exaggerated size of the Korean Peninsula compared to any other regions in the map. If a non-Korean, such as a Japanese or a Chinese designed this map, there are no reasons why one should have treated Korea so specially with care and more realistically than other regions in the map. This practice is comparable to the Hereford Mappa Mundi, which showcased the British Isles with more detail and larger than other places in the map.

Carto-genetically speaking, Ch’ŏnhado does not belonging to the family tree of a world map from the West Europe.

The circle frame of Ch’ŏnhado is not necessarily a copy from a circular framed Western world map for the symbol of circle was widely used and readily available for any use in Korea.

Even if currently the extant copy of Ch’ŏnhado only dates to the seventeenth century, it does not mean that Ch’ŏnhado was not created before that time period. It is evidence that the map was at latest on or before the seventeenth century, because here the seventeenth century is terminus ante quem (the time before which) and is not terminus post quem (the time after which).

Ch’ŏnhado is not a Korean style interpretation of a Western world map. It is an indigenous Korean folk cartographical sketch map based on Chosŏn dynasty Confucian literati’s folkloristic imagination and information gathered from Shanhai-jing and other East Asian sources.

Ch’ŏnhado is an indigenous Korean world map of folklore that represents the China-centered Korean geomentality effectively.

Acknowledgments

This paper is based on and developed from my earlier paper in Korean: Hong-key Yoon, “Ch’ŏnhado-ŭi kiwŏnŭi ch’atki wihayŏ (In Search of the Origin of ch’ŏnhado, a Traditional Korean Map of the World), Munhwa Yŏksa chiri (Journal of Cultural and Historical Geography) vol. 34, no. 3 (2022) 160–174. I am grateful to Mr Neil Linsay for his critical reading of this manuscript and valuable editorial helps; to the two reviewers of this manuscript, I wish to thank them for their positive feedback with helpful comments and suggestions.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. The ancient Chinese classic dealing with mythical geography of lands, waters, plants, animals and indigenous peoples of imaginative places. The original author and the exact date of the book are unknown, but an early version of the text must have existed several centuries BCE.

References

- Bae Woo-sung. 2000. sŏ’kusik segye chido ui Chosŏnsik haesŏk (Ch’ŏnhado, Koreans’ Own Interpretation on the European World Map in the Late Chosŏn Period). Han’guk Kwahaksahakhwoiji (The Korean Journal for the History of Science) 22 (1): 52–79

- Cressey, G. B. 1955. Land of 500 Million: A Geography of China. New York: McGraw Hill

- Haynes, R. M. 1981. Geographical Images and Mental Maps, (Aspects of Geography). General Editors: J.H. Johnson and Keith Clayton. London: Macmillan Education

- Hulbert, H. B. 1904. An Ancient Map of the World. Bulletin of the American Geographical Society of New York 36 (10): 600–605. 10.2307/197979

- Kim Yangsŏn. 1972. Han’guk Kochido Yŏn’guch’o (Initial Research on Korean Old Maps). (Initial Research on Korean Old Maps). Seoul: Sungsil University Press. (Initial Research on Korean Old Maps).

- Ledyard, G. 1994. Cartography in Korea. In The History of Cartography, edited by H. B. Harley and D. Woodard, Volume Two, Book Two 235–345. Chicago, USA: The University of Chicago Press

- Lee Chan. 1976. Han’gukui Ko Chido: Ch’ŏnhadowa Honil Kangni Yokdae Chi Toe taehayŏ (The Old Maps of Korea: On the Map of the World and Map of Integrated Regions of Historical States and Capitals) Han’guk hakpo韓國學報 2: 47–66

- Oh Sanghak. 2015. Han’guk Chŏnt’ong Chirihaksa 한국전통지리학사 (a History of Traditional Korean Geography). Seoul: Tŭlnyŏk. 227–241

- Oh Sanghak. 2001. Chosŏnhuki wŏnhyŏng Ch’ŏnhado ŭi T’ŭksŏng Kwa Segyekwan (The Characteristics and the Worldview in Circular World Map Made in the Late Joseon Dynasty). Chirihak Yŏnku (Geographical Research) 35 (3): 231–247

- Oh Sanghak. 2008. Circular World Map of the Joseon Dynasty: Their Characteristics and World View. Korea Journal Spring, 8–43. 10.25024/kj.2008.48.1.8

- Ricci, M. 1602. Kunyu Wanguo Quantu ( 坤輿萬國全圖). https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kunyu_Wanguo_Quantu_(%E5%9D%A4%E8%BC%BF%E8%90%AC%E5%9C%8B%E5%85%A8%E5%9C%96).jpg

- Unno Kazutaka 海野一隆. 1981. Richō chōsen Ni Okeru Chizu to dōkyō (Maps and Daoism in the Chosŏn Dynasty) 李朝朝鮮にお ける地圖と道敎”. Tōhōshūkyō (東方宗敎Eastern Religions) 57: 1–37

- Whitfield, P. 1994. The Image of the World: 20 Centuries of World MapsLondon: The British Library

- Yang Yi 陽益 (also Known as Yang Yunsong楊筠松 (834–900)). 1967. Hanlong-jing撼龍經 in Dili Zhengzong地理正宗 卷三 陽益 (also Known as Yang Yunsong楊筠松 (834–900)). Hsinchu City, Taiwan: Zhulinshuju, and Seoul: Pibong Chulpansa

- Yi Ik Seup 李益習. 1892. A Map of the World. The Korean Repository 1: 336–341

- Yoon, H.-K. 1986. Maori Mind, Maori Land. Berne: Peter Lang International Academic Publishers

- Yoon, H.-K. 1991. On Geomentality. Geo Journal 25 (4): 387–392. 10.1007/BF02439490

- Yoon, H.-K. 2022. Ch’ŏnhado-Ui kiwŏnŭl Chatkiwihan yebikoch’al (In Search of the Origin of Ch’ŏnhado, a Traditional Korean Map of the World). Munhwa Yŏksachiri (Journal of Cultural and Historical Geography) 34 (3): 160–174. 10.29349/JCHG.2022.34.3.160