Abstract

This was an observational study of hospitalized patients with dementia who developed COVID-19. The disease course, dietary intake, and disease severity (mild/severe) were evaluated. Twenty-nine patients with a median age of 84 years, with both mild (18) and severe conditions, (11) were evaluated. Mild group had decreased food intake from the day of symptom onset. In the severe group, the decline began the day before symptom onset. On day 30 of the disease, the median food intake of the mild group returned to levels observed prior to symptom onset, in contrast to those in the severe group.

Introduction

As of June 2022, over 530 million individuals have contracted coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), and six million individuals have died from the condition (COVID-19 Global Tracker Citation2021). The dissemination of vaccines is expected to slow the spread of the virus; however, similar to the influenza virus, the number of COVID-19 cases may continue to increase at regular intervals, necessitating continuous countermeasures.

Common symptoms of acute COVID-19 infection include fever, upper respiratory tract symptoms, and taste and olfactory dysfunction (Guan et al. Citation2020; Huang et al. Citation2020). COVID-19 differs from other viral diseases that cause upper respiratory tract infections in that it affects patients both acutely and chronically. Of those infected with COVID-19, 87.4% experience after-effects for up to two months, such as fatigue, dyspnea, and joint pain (Carfì, Bernabei, and Landi Citation2020). In addition to physical after-effects, 48.7% of patients similarly reported mental and emotional symptoms for up to two-month post-discharge, including insomnia and anxiety (Chopra et al. Citation2021). Moreover, older patients with COVID-19 exhibit acute symptoms, including malaise, fever, delirium, and lack of appetite. Of these older patients, 33.1% continue to report poor appetite in the chronic phase for up to three months after discharge (Vrillon et al. Citation2020; Carrillo-Garcia et al. Citation2021). Reduced dietary intake is believed to be a result of other symptoms and may exacerbate sarcopenia or frailty in older patients (Volkert et al. Citation2019). However, older patients with dementia rarely complain of symptoms, requiring healthcare providers to manage these patients appropriately.

Previous studies have reported that COVID-19 causes a general loss of appetite (Ungaro et al. Citation2020; Vrillon et al. Citation2020; Carrillo-Garcia et al. Citation2021; Zeng et al. Citation2021). However, to the best of our knowledge, no reports tracking dietary intake before and after the development of COVID-19 symptoms have been published. It was considered important, especially in elderly patients, to know how their eating habits decline and whether they subsequently recover. Therefore, this study aimed to determine changes in dietary intake over time in older patients with dementia and COVID-19.

Methods

Setting and Patients

This is a single-center, retrospective, observational study of post-admission COVID-19 infection in elderly patients with dementia hospitalized between December 17 and 26, 2020. While the routes of transmission of COVID-19 could not be completely identified, all patients had been hospitalized for at least seven days prior to the onset of COVID-19 symptoms, including fever. The study setting was a chronic care ward with approximately 100 beds, specializing in elderly patients with dementia who are often hospitalized for 30 days or more.

Therefore, the inclusion criteria are patients hospitalized during the above period and who contracted COVID-19 during their hospitalization. The researcher excluded the following patients: those affected by COVID-19 who (1) had normal cognitive function and (2) had no symptoms of COVID-19. One author maintained the ID and password data under lock and key; the other two authors extracted patient information details from the electronic medical records, each checking the other’s data after extraction. Finally, the corresponding author checked the data. We assessed the changes in dietary intake of enrolled patients from seven days before COVID-19 symptom onset to 30 days after.

Ethics

The study protocol was approved by the institutional ethics committee of the hospital (No. 111-32). This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. A consent form was posted on the institution’s website and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Variables

As a primary outcome, we collected patients’ dietary intake (see below). We also collected the data on patient characteristics, including age, sex, and comorbidities (presence or absence of cardiovascular disease, hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, bronchial asthma, chronic kidney disease, diabetes mellitus, and malignant tumor), were collected.

Cognitive function was evaluated using the Japanese version of the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE-J), with dementia defined as a score of ≤23 (Sugishita et al. Citation2018). Dementia was also diagnosed by psychiatrists according to clinical course and symptoms as well as based on results of cerebral blood flow single-photon emission computed tomography, head magnetic resonance imaging, and other examinations. In addition, COVID-19 was diagnosed based on positive reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction tests. Based on symptoms and clinical course, delirium was diagnosed by psychiatrists using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of the American Psychiatric Association (DSM-5). Nurses recorded the occurrence of falls.

Definition of COVID-19

The onset of COVID-19 was defined as the development of fever (axillary temperature ≥37.3 °C) or upper respiratory tract symptoms. Outside of Japan, fever is generally defined as a temperature of ≥37.5 °C. The criteria for severe disease included an oxygen saturation ≤93% or a respiratory rate ≥30 breaths/min (World Health Organization Citation2019). The disease was considered mild when neither of these conditions were met (World Health Organization Citation2019).

Prednisolone, heparin, and antimicrobial agents were administered in severe cases, as deemed necessary by the COVID-19 medical team, which consisted of members from the departments of general medicine, respiratory medicine, and psychiatry. As this cohort was older and often frail, ventilators were rarely used and only administered after explaining the patient’s condition to and obtaining consent from families. Oral supplements, peripheral infusions, or central venous catheters were used for patients with poor dietary intake at the discretion of the COVID-19 team.

Enteral nutrition was not administered to any patients without obtaining consent from families. Patients who died during the study period were excluded from the assessment of oral intake over time.

Evaluation of Dietary Intake

Dietary intake was evaluated at each meal by a nurse, as described in a previous study (Komatsu et al. Citation2017). The intake of main dishes and side dishes was evaluated on a 10-point scale, and was divided by the number of meals to obtain the dietary intake for one day (maximum score of 10) (Komatsu et al. Citation2017).

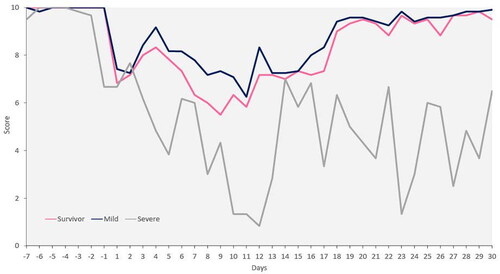

Missed meals or meals not ordered were treated as missing data and not included in the overall number. Changes in dietary intake from seven days prior to symptom onset to 30 days after were determined and compared after dividing the patients into three groups: all survivors, survivors with mild disease (mild group), and survivors with severe disease (severe group).

At admission and discharge, oral intake and frailty were evaluated using the Functional Oral Intake Scale (FOIS) and Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) (Crary, Mann, and Groher Citation2005; Morley et al. Citation2013).

Data Analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as median values (interquartile range [IQR]). Normal and non-normal distributions were compared using t-tests and Mann–Whitney U tests, respectively.

Categorical variables were expressed as proportions (%) and were analyzed using chi-squared tests. As daily dietary intake was non-normally distributed, median values were used to create graphs. All calculations were performed using JMP PRO software (version 13.0; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

A total of 31 symptomatic patients tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 and were diagnosed with COVID-19 at our geriatric medical center during the study period. Of these, two patients were excluded due to MMSE-J scores of >24. Ultimately, 29 patients were included in the study, of whom 18 and 11 had mild and severe disease, respectively. Four patients died during the period due to COVID-19 exacerbations.

Among the patients, 16 were women (55.2%), and the median age was 84 (IQR: 78–87) years. Prior to COVID-19 symptom onset, median CFS and MMSE-J scores were 6 (IQR: 5–7) and 13 (IQR: 7–16) points, respectively. Additionally, the median FOIS score was 6 (IQR: 5–7) points. The most common type of dementia was Alzheimer’s disease (55.2%), and the most common comorbidity was hypertension (44.8%). No steroids, immunosuppressants, tube feedings, peripheral infusions, or central venous catheters were administered prior to symptom onset ().

Table 1. Baseline patient characteristics.

shows the course of treatment for patients. All patients exhibited fever, approximately half presented with upper respiratory tract symptoms, and approximately one-third presented with dyspnea. Nineteen patients (65.5%) exhibited delirium after disease onset, and three patients (10.3%) experienced falls. The median FOIS score was 6 (IQR: 5–7) points among all survivors 30 days after symptom onset. Eleven patients (37.9%) met the World Health Organization’s criteria for severe disease, with conditions becoming severe at a median of eight days after symptom onset (IQR: 6–12 days) ().

Table 2. Effects of coronavirus disease 2019.

shows the changes in dietary intake among the patients from seven days before to 30 days after symptom onset. The appetite of patients with mild disease tended to start declining from the first day of symptoms, reaching a nadir on day 11. In patients with severe disease, appetites tended to decline before symptoms appeared, reaching a nadir on day 12. Among all survivors, appetites started declining when symptoms appeared, reaching a nadir on day 9. The median dietary intake of patients with mild disease and that of all survivors mostly recovered by day 30 post-symptom onset. However, the median at 30 days after symptom onset was approximately 60% of pre-disease levels in patients with severe disease ().

Discussion

This study evaluated the changes in dietary intake associated with COVID-19 in older patients with dementia. Our results demonstrated that appetite levels declined after symptom onset in patients with mild disease and in all survivors. In contrast, declines in appetite began prior to symptom onset in patients with severe disease. In all patients, appetites were at their lowest on days 9–12, after which they improved in all survivors and patients with mild disease, but not in patients with severe disease.

Reduced dietary intake exacerbates frailty and sarcopenia in older individuals (Volkert et al. Citation2019), with weight loss affecting their survival prognoses (Huffman Citation2002). Furthermore, unlike younger patients, the elderly have many comorbidities, and it is necessary to assume that if their nutritional status deteriorates over the medium to long term, death will result not from COVID-19 itself but from the progression of nutritional status and comorbidities. Therefore, considering the dietary intake levels in older individuals with COVID-19 is essential. A previous study that administered both tube feedings and non-tube feedings to older patients whose dietary intake declined by 50% after COVID-19 onset reported that malnutrition persisted for up to six months in the tube-feeding group (Ramos et al. Citation2021). Another study revealed that the early use of oral dietary supplements was critical in older patients with COVID-19 (Schuetz et al. Citation2019). Moreover, the following four focus areas may improve dietary intake during recovery from COVID-19: (1) properly functioning senses, (2) familiar foods, (3) eating environments, and (4) a properly functioning gastrointestinal system (Høier, Chaaban, and Andersen Citation2021). When dietary intake is low, dietary supplements and strategies that address these four areas are vital.

Furthermore, patients with severe COVID-19 in our study exhibited reduced appetite prior to symptom onset. Approximately 57% of older patients with COVID-19 exhibit a loss of appetite in the early stages of infection (Vrillon et al. Citation2020), and dietary intake has been found to be a predictor of in-hospital bacteremia (Komatsu et al. Citation2017). Collectively, these findings suggested that changes in dietary intake may help predict disease severity early in older patients with COVID-19.

In a previous study, confusion and delirium were observed in 70% of older patients with COVID-19 (Vrillon et al. Citation2020), which was consistent with the results of our study, where approximately 65% patients experienced delirium. Isolation due to COVID-19 increases the behavioral and psychological symptoms in approximately 60% of older patients with dementia and leads to increased stress in two-thirds of caregivers (SINdem COVID-19 Study Group, 2020). Therefore, both physical and mental health considerations must be given in cases of hospital infections.

In our study, the mean baseline CFS was higher than that in other populations. High CFS scores are associated with increased mortality within one month of contracting COVID-19. In a previous study, 37.6% of patients with a mean CFS score of 6 died, which was 2.13 times more than those with CFS scores between 1–3 (95% confidence interval, 1.34–3.38) (Aw et al. Citation2020). The mortality rate in our study was 13.8%, which differs from that of previous studies. However, direct comparisons are difficult due to differences such as race.

Hospital-acquired SARS-CoV-2 infections, such as those in our study, are likely to occur worldwide. For instance, one study reported that 66% of the older individuals in assisted-living facilities contracted SARS-CoV-2, 29% of whom died (Bernadou et al. Citation2021). Similarly, another report showed a mortality rate of 34% (Bernadou et al. Citation2021,Public Health–Seattle and King County, EvergreenHealth, and CDC COVID-19 Investigation Team, 2020). Several patients are also believed to have contracted SARS-CoV-2 in hospitals and long-term care facilities for older patients. Initially, when assuming the frequency of death after COVID-19, it is necessary to include baseline dietary intake and level of independent living, as well as the subsequent recovery of diet and independent living.

Our study had several limitations. First, the sample size was relatively small; thus, definitive conclusions could not be drawn from our data alone. Second, as we did not consider patient characteristics for each underlying disease or backgrounds prior to contracting SARS-CoV-2, appetites may have decreased due to other reasons. Finally, this was a single-center study; therefore, external validity could not be confirmed. Despite these limitations, our findings were important and novel, particularly as the first study to evaluate changes in dietary intake over time in older patients with dementia who developed COVID-19. Dietary intake decreased after the onset of symptomatic COVID-19, with the greatest reduction occurring 9–12 days after onset. Dietary intake improved over time in all survivors, particularly in patients with mild disease. Moreover, patients with severe disease did not appear return to pre-disease levels of appetite, indicating the potential need for long-term treatment and care. Therefore, a better understanding of appropriate dietary supplementation and recovery timing in these patients may be a topic for future research. Moreover, with respect to various diseases that occur in the hospital, in treating the elderly in the future, it is essential to investigate their dietary intake.

In conclusion, this study investigated dietary intake before and after COVID-19, and the severity of COVID-19 may be related to the degree of recovery of diet. Therefore, dietary intake may be involved in assessing COVID-19 severity in the future.

Authors’ Contributions

TM and TW made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work. TM, TW, SY, NA, KS, NS, YK, and KSY made significant contributions to the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data. TM, TW, and TN contributed to the creation of new software used in the work. TM, TW, and TN drafted the work or substantively revised it. All authors have approved the submitted version. All authors have agreed to be personally accountable for their contributions and to ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work, even ones in which the author was not personally involved, are appropriately investigated and resolved and that the resolution is documented in the literature.

Ethics Approval and Informed Consent

The institutional ethics committee of Juntendo Tokyo Koto Geriatric Medical Center approved the study protocol (No. 111-32). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. A consent form was posted on the institution’s website and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

| Abbreviations | ||

| COVID-19 | = | coronavirus disease 2019 |

| SARS-CoV-2 | = | severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 |

| MMSE-J | = | Mini-Mental State Examination |

| FOIS | = | Functional Oral Intake Scale |

| CFS | = | Clinical Frailty Scale |

| IQR | = | interquartile range |

Acknowledgments

We thank all the medical professionals who worked together amidst the COVID-19 pandemic.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aw, D., L. Woodrow, G. Ogliari, and R. Harwood. 2020. Association of frailty with mortality in older inpatients with Covid-19: a cohort study. Age and Ageing 49 (6):915–22. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afaa184.

- Bernadou, A., S. Bouges, M. Catroux, J. C. Rigaux, C. Laland, N. Levêque, U. Noury, S. Larrieu, S. Acef, D. Habold, et al. 2021. High impact of COVID-19 outbreak in a nursing home in the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region, France, March to April 2020. BMC Infectious Diseases 21 (1):198. doi: 10.1186/s12879-021-05890-6.

- Cagnin, A., R. Di Lorenzo, C. Marra, L. Bonanni, C. Cupidi, V. Laganà, E. Rubino, A. Vacca, P. Provero, V. Isella, SINdem COVID-19 Study Group, et al. 2020. Behavioral and psychological effects of coronavirus disease-19 quarantine in patients with dementia. Frontiers in Psychiatry 11:578015. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.578015.

- Carfì, A., R. Bernabei, and F. Landi. 2020. Persistent symptoms in patients after acute COVID-19. JAMA 324 (6):603–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.12603.

- Carrillo-Garcia, P., B. Garmendia-Prieto, G. Cristofori, I. L. Montoya, J. J. Hidalgo, M. Q. Feijoo, J. J. B. Cortés, and J. Gómez-Pavón. 2021. Health status in survivors older than 70 years after hospitalization with COVID-19: observational follow-up study at 3 months. European Geriatric Medicine 12 (5):1091–4. doi: 10.1007/s41999-021-00516-1.

- Chopra, V., S. A. Flanders, M. O’Malley, A. N. Malani, and H. C. Prescott. 2021. Sixty-day outcomes among patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Annals of Internal Medicine 174 (4):576–8. doi: 10.7326/M20-5661.

- COVID-19 Global Tracker 2021. https://graphics.reuters.com/world-coronavirus-tracker-and-maps/ja/. Accessed June 24 2022; Reuters.

- Crary, M. A., G. D. Mann, and M. E. Groher. 2005. Initial psychometric assessment of a functional oral intake scale for dysphagia in stroke patients. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 86 (8):1516–20. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.11.049.

- Guan, W.-J., Z.-Y. Ni, Y. Hu, W.-H. Liang, C.-Q. Ou, J.-X. He, L. Liu, H. Shan, C.-L. Lei, D. S. C. Hui, et al. 2020. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. The New England Journal of Medicine 382 (18):1708–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032.

- Høier, A. T. Z. B., N. Chaaban, and B. V. Andersen. 2021. Possibilities for maintaining appetite in recovering COVID-19 patients. Foods 10 (2):464. doi: 10.3390/foods10020464.

- Huang, C., Y. Wang, X. Li, L. Ren, J. Zhao, Y. Hu, L. Zhang, G. Fan, J. Xu, X. Gu, et al. 2020. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet (London, England) 395 (10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5.

- Huffman, G. B. 2002. Evaluating and treating unintentional weight loss in the elderly. Am Fam Phys 65:640–50.

- Komatsu, T., E. Takahashi, K. Mishima, T. Toyoda, F. Saitoh, A. Yasuda, J. Matsuoka, M. Sugita, J. Branch, M. Aoki, et al. 2017. A simple algorithm for predicting bacteremia using food consumption and shaking chills: a prospective observational study. Journal of Hospital Medicine 12 (7):510–5. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2764.

- McMichael, T. M., D. W. Currie, S. Clark, S. Pogosjans, M. Kay, N. G. Schwartz, J. Lewis, A. Baer, V. Kawakami, M. D. Lukoff, Public Health–Seattle and King County, EvergreenHealth, and CDC COVID-19 Investigation Team, et al. 2020. Epidemiology of Covid-19 in a long-term care facility in King County, Washington. The New England Journal of Medicine 382 (21):2005–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2005412.

- Morley, J. E., B. Vellas, G. A. van Kan, S. D. Anker, J. M. Bauer, R. Bernabei, M. Cesari, W. C. Chumlea, W. Doehner, J. Evans, et al. 2013. Frailty consensus: a call to action. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 14 (6):392–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2013.03.022.

- Ramos, A., C. Joaquin, M. Ros, M. Martin, M. Cachero, M. Sospedra, et al. 2021. Impact of COVID-19 on nutritional status during the first wave of the pandemic. Clin Nutr 41 (12):3032–7. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2021.05.001.

- Schuetz, P., R. Fehr, V. Baechli, M. Geiser, M. Deiss, F. Gomes, A. Kutz, P. Tribolet, T. Bregenzer, N. Braun, et al. 2019. Individualised nutritional support in medical inpatients at nutritional risk: a randomised clinical trial. Lancet (London, England) 393 (10188):2312–21. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32776-4.

- Sugishita, M., Y. Koshizuka, S. Sudou, et al. 2018. The validity and reliability of the Japanese version of the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE-J). Ninchi Shinkei Kagaku 20:91–110. (in Japanese).

- Ungaro, R. C., T. Sullivan, J. F. Colombel, and G. Patel. 2020. What should gastroenterologists and patients should know about COVID-19? Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology: The Official Clinical Practice Journal of the American Gastroenterological Association 18 (7):1409–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.03.020.

- Volkert, D., A. M. Beck, T. Cederholm, A. Cruz-Jentoft, S. Goisser, L. Hooper, E. Kiesswetter, M. Maggio, A. Raynaud-Simon, C. C. Sieber, et al. 2019. ESPEN guideline on clinical nutrition and hydration in geriatrics. Clinical Nutrition (Edinburgh, Scotland) 38 (1):10–47. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2018.05.024.

- Vrillon, A., C. Hourregue, J. Azuar, L. Grosset, A. Boutelier, S. Tan, M. Roger, V. Mourman, S. Mouly, D. Sène, et al. 2020. COVID-19 in older adults: a series of 76 patients aged 85 years and older with COVID-19. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 68 (12):2735–43. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16894.

- World Health Organization. 2019. Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection when novel coronavirus. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/330893. Accessed June 24 2022; nCoV Infection is Suspected: interim guidance.

- Zeng, Q., H. Cao, Q. Ma, J. Chen, H. Shi, and J. Li. 2021. Appetite loss, death anxiety and medical coping modes in COVID-19 patients: a cross-sectional study. Nursing Open 8 (6):3242–50. doi: 10.1002/nop2.1037.