?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This paper explores a taxonomy of uses of ‘because’ from the linguistics literature. It traces the apparent semantic differences between content, epistemic, and act ‘because’ to differences in attachment height. But it argues that the fact that these uses of ‘because’ never occur in the same environments is evidence of an underlying semantic unity. Arguments from such a distribution to underlying unity are familiar from phonology and morphology, and they are implicit in Quine's comments on ambiguity in Word and Object, but they have too rarely been deployed in semantics. Here, such an argument points the way towards an underexplored conception of polysemy, while also making progress on the rather more limited topic of the lexical semantics of ‘because’.

Previous work has argued that ‘why’ and ‘because’ exhibit metaphor-generated polysemy: they have primary causal meanings in addition to distinct metaphorical meanings that are used to communicate metaphysical explanations.Footnote1 Here the question arises how many additional senses ‘why’ and ‘because’ have. In this paper, I focus in particular on a taxonomy of uses of ‘because’ investigated by linguists. That taxonomy distinguishes content, epistemic, and act uses of ‘because’, represented by (1), (2), and (3), respectively.Footnote2

| (1) | He brought her moss for her terrarium because he likes her. | ||||

| (2) | He likes her, because he brought her moss for her terrarium. | ||||

| (3) | What are you doing tonight? – because there's a movie on.Footnote3 | ||||

Eve Sweetser has argued that the difference between (1), (2), and (3) involves what she calls pragmatic ambiguity, which ‘depends not on form, but on a pragmatically motivated choice’ between interpretations (Sweetser, Citation1990, 78). I will argue that this is precisely wrong; the difference between these uses of ‘because’ is entirely a difference in form.Footnote4

Theorists, recognizing the distinction between these apparent senses of ‘because’, commonly set epistemic and act uses aside in order to focus on content uses.Footnote5 But I argue below that these uses of ‘because’ require the same semantic contribution of ‘because’ as its content uses. The difference between the categories of uses lies in what is being explained rather than in the explanatory relation at issue. That is, all differences between the uses are traceable to differences in their explananda. Epistemic and act uses of ‘because’, on my view, introduce explanations related in certain ways to speech acts, such as how the speaker was in a position to make an assertion or why she has made it. Thus for a speaker who knows the content meaning of ‘because’ to acquire competence with its epistemic and act meanings, she need only recognize that more kinds of things – her own acts and her ability to perform them legitimately – can be explained. Neither epistemic nor act ‘because’, therefore, expresses a meaning of ‘because’ that content ‘because’ does not express. Adopting this perspective on epistemic and act ‘because’-sentences allows us to avoid positing excessive ambiguity for ‘because’, preserving semantic unity where we can.Footnote6 This benefit brings with it an expansion in what it takes to give a full account of ‘why’-questions: it undermines one justification for excluding, e.g. ‘why’-questions that would be answered by act ‘because’-clauses.Footnote7

The associated perspective on polysemy is also of broader interest, since it bears on our thinking about the relationship between ambiguity and logical form.Footnote8 Viebahn and Vetter (Citation2016), writing about modals like ‘may’, treat differences in logical form as indicative of polysemy, as opposed to the kind of context-sensitivity exhibited by indexicals. But we can separate purely structural or syntactic ambiguities from semantic ambiguities, and in the cases I am going to discuss, I think we should consider the syntactic differences that I identify to explain away any appearance of semantic disunity. This is an important point for philosophers, because theoretical pressure to avoid ambiguity posits can and does needlessly mislead philosophers into accepting theories with substantial theoretical downsides.Footnote9

Here is another way of making the broader point. Consider a formal semantics for English in which a typical lexical entry consists of an expression of a typed lambda calculus, as in (4), where p is the type for physical objects.Footnote10

| (4) | λx: p tree(x) | ||||

Such lexical entries contain logical structure: the lambda operator and its type restriction (in (4), ‘λ x: p’) can be distinguished from what occurs in the scope of the lambda operator (in (4), ‘tree(x)’). Call the former part of such an entry its logical form, and the latter part its semantic content. Lexical ambiguity is already standardly distinguished from syntactic ambiguity.Footnote11 We can extend this distinction inside lexical entries by further distinguishing ambiguities relating to differences in the logical form of a lexical entry from differences in its semantic content.

To see the point, consider what the proper lexical entry for the English word ‘tree’ used when talking about semantic trees should be, imagining that the lambda calculus is also equipped with a type for abstract objects, a. (4) is, let it be stipulated, clearly inappropriate since semantic trees are not physical objects. But should the ambiguity be localized to the logical form of the lexical entry, as it would be if (5-a) were the proper lexical entry for semantic trees? Or does the ambiguity of ‘tree’ also involve a purely semantic difference, in the form of a different non-logical constant in the semantic content half of the lexical entry, as in (5-b)?

| (5-a) | λx: a tree(x) | ||||

| (5-b) | λx: a branchingstructure(x) | ||||

In the cases that this paper will focus on, the difference in lambda types is more dramatic, and even more clearly syntactic rather than semantic, than the difference between p and a in (4) and (5-a). But the point will be that sameness of semantic content – that is, sameness of the second half of the lexical entry, as exhibited by (4) and (5-a) relative to one another – is a kind of lexical semantic unity. Mere differences in logical form, e.g. differences in the lambda type of a lexical entry, can be seen as syntactic ambiguities, even though the syntax with which they have to do is internal to lexical entries. Such differences might even be artifacts of non-essential features of a chosen regimentation into a formalized system, rather than necessary components of a lexical entry.Footnote12 This is, at least, the perspective behind this paper.

Enough preliminaries. On to the data.

1. The basic phenomenon

This section introduces some useful terminology and specifies the intended interpretation of epistemic and act ‘because’ sentences by way of contrast with content ‘because’ sentences.

(1) contains a content ‘because’ clause.

| (1) | He brought her moss for her terrarium because he likes her. | ||||

An utterance of (1) explains his bringing her moss by his liking her. More generally, the explanans phrase – the part after the ‘because’ – in a sentence containing a content ‘because’ clause adduces part of an explanation of whatever is picked out by the explanandum phrase – the part before the ‘because’, which I'll also sometimes call the prejacent. There will be more to say, in Section 5, about potential ambiguities of the ‘because’ in (1), but for the next few sections, this much will suffice.

The epistemic ‘because’ sentences below might appear to involve a non-explanatory sense of ‘because’.

| (2) | He likes her, because he brought her moss for her terrarium. | ||||

| (6) | His brakes failed, because there are no skid marks. | ||||

| (7) | Alma is probably sick, because she didn't show up for work.Footnote13 | ||||

The relationship between (1) and (2) is excellent prima facie evidence that the relationship reported in (2) is not explanatory: if his liking her explains his bringing her moss, then his bringing her moss cannot explain his liking her, on pain of violating a very intuitive asymmetry condition on explanation. But the fact that his bringing her moss does not explain his liking her doesn't mean that (2) cannot communicate any explanatory relationship. Rather, an utterance of (2) offers (something like) an explanation of the speaker's knowing that he likes her. (Thus the label ‘epistemic’ for these kinds of ‘because’ sentences.) Similar comments apply to (6) and (7), though this account of the meaning of these sentences will be refined further below, once we are in a position to say more about it.

It is worth noting that, on paper, native English speakers tend to reject examples like (2) as defective, as if they are just missing something like ‘I know that’ or ‘it must be that’. But we say them all the time, and they are grammatical.Footnote14

The key to making sense of sentences like (2), (6), and (7) is to utter them with the proper intonation. As Couper-Kuhlen (Citation1996) discusses, (2) and (3) are acceptably uttered only with comma intonation or period intonation.Footnote15 By uttering (2) with appropriate prosody, the speaker is readily interpreted as explaining her assertion of the main clause.Footnote16 To see the importance of prosody here, compare (2) with (8).

| (8) | #He likes her because he brought her moss for her terrarium. | ||||

An utterance of (8) – without comma intonation – would only be true if, due to some psychological quirk, the reason he likes her really is that he brought her the moss. (2), uttered with comma intonation, has a content reading with this truth-condition, in addition to its epistemic reading. But (8) has only the content reading.

Moving on from epistemic ‘because’ clauses, (3) contains an act ‘because’ clause.

| (3) | What are you doing tonight? – because there's a movie on. | ||||

An utterance of (3) explains the speaker's having asked the question. Act ‘because’ is not limited to explaining questions; it can also attach to imperatives.

| (9) | Don't bring her here, because Mum will be very upset and Dad will be furious.Footnote17 | ||||

In addition to explaining speech acts, act ‘because’ clauses can explain features of speech acts. For example, act ‘because’ clauses can perform Horn (Citation1985)'s full range of metalinguistic functions.

| (10) | He managed to solve some of the problems, because he didn't manage to solve all of the problems. | ||||

| (11) | You managed to solve the problem, because it was hard. | ||||

| (12) | ‘Mongeese’, because it sounds better than ‘mongooses’. | ||||

| (13) | ‘Indisposed’ rather than ‘feeling lousy’, because it's more polite. | ||||

Utterers of the above sentences explain choices relating to conversational implicature ((10)), phonetic representation ((11)), inflectional morphology ((12)), and style ((13)). Notice that each of these examples requires comma intonation.

I think of speech-act ‘because’ sentences like (3) and (9) and metalinguistic ‘because’ sentences like (10)–(13) as part of a larger class of cases where the speaker explains something about what just happened. So it is important to notice that ‘because’ can also attach to acts other than speech acts.

| (14) | (After knocking) Because I want to talk to them. | ||||

An utterance of (14) explains the action just performed, namely, the speaker's knocking. As with speech acts, utterances of ‘because’ clauses can explain not only why acts were performed, but various features of those acts.

| (15) | (After knocking softly) Because I don't want to wake their baby. | ||||

An utterance of (15) explains a feature of the speaker's knock, namely, its softness.

As the felicity of (14) and (15) show, what the speaker explains with a ‘because’ clause needn't involve anything linguistic. The essential feature, shared by all of these examples, is that the ‘because’ clause comments on some salient act or representation.Footnote18 In what follows, I give a unified treatment of content ‘because’, epistemic ‘because’, and this whole class of cases: whatever differences might be discerned between (1), (2), (3), (9), (10)–(13), (14), and (15), they don't turn out to require different semantic contributions from ‘because’ itself.Footnote19

2. My basic claim

I claim that the ‘because’ has the same meaning, in an important and identifiable sense, in (2) and (3) as it does in (1). In particular, I claim that it is a lexicalization of a discourse relation of Explanation (cf. Asher and Lascarides, Citation1995).

| (16) | He brought her moss for her terrarium. He likes her. | ||||

| (17) | He likes her. He brought her moss for her terrarium. | ||||

| (18) | What are you doing tonight? There's a movie on. | ||||

In each of these cases, the second sentence is an explanation, providing the reason for what went before. In (16), what is explained is the content of the first sentence: the reason why he brought her moss is that he likes her. In (18), however, what is explained is the preceding utterance itself: the reason why the speaker asked what the listener is doing tonight is that there is a movie on. So, for a ‘because’ clause to be used to express the explanations in (18), the clause can't attach to the content of a prejacent, but must attach to the act of uttering it. (17) is a more interesting case, since the explanation is of the speaker's being in the position to assert that he likes her: the reason why the speaker is in the position to assert that he likes her is that (the speaker knows that) he brought her moss for her terrarium.Footnote20 In every case, then, a ‘because’ clause introduces a reason why, and (I am going to argue) a reason why in precisely the same sense.Footnote21 All of the differences between these examples can be attributed to differences in their explananda, rather than differences in the sense in which the reason why is a reason why.Footnote22 What goes for (16)–(18), moreover, goes for (1)–(3), where the discourse relation of Explanation is simply made explicit in the form of the connective ‘because’.

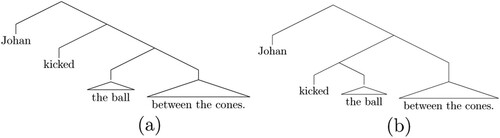

In support of this account, I present evidence that the difference in the “meaning” of ‘because’ in these sentences is due to a syntactic difference, namely, a difference in attachment height. To give a simple example, differences in attachment height account for the different readings of (19).

| (19) | Johan kicked the ball between the cones.Footnote23 | ||||

This sentence exhibits a classic syntactic ambiguity: it can be analyzed by two different parse trees, in which ‘between the cones’ attaches at two different heights, as depicted in Figure . The different attachment heights correspond to what the prepositional phrase ‘between the cones’ modifies. It could attach low in the tree, modifying the noun phrase ‘the ball’, and therefore specifying the location of the ball before Johan kicked it. Or it could attach higher in the tree, modifying the verb phrase ‘kicked the ball’, and therefore specifying where the ball went after John kicked it.

Figure 1. Different attachment heights, different readings. (a) Low attachment. (b) High attachment.

We have already seen some of the evidence that the different uses of ‘because’ involve different attachment heights for the ‘because’ clause: the very need for comma intonation or period intonation to elicit epistemic and act readings is diagnostic of this kind of syntactic difference.Footnote24 In the next section, additional evidence will pile up.

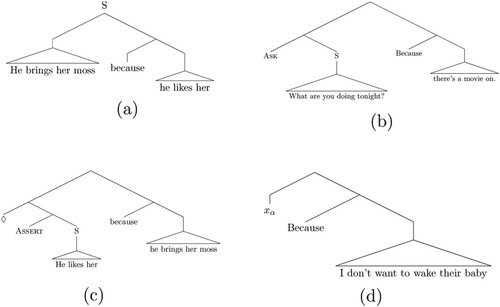

My concrete proposal, represented in Figure , will be that all of this evidence can be accounted for if we posit that act ‘because’ attaches to an act (e.g. of assertion, or of door-knocking), and that epistemic ‘because’ attaches to a modal located above such an act.Footnote25 In the case of non-linguistic acts, the act that is being explained has to be identified from the context, so it is represented in the parse tree in Figure (d) by an act-type variable, . Some philosophers may regard act-type variables, or the idea that speech acts can themselves be part of parse trees, as theoretically dubious. Those philosophers might prefer a view on which epistemic and act ‘because’ clauses do not attach to the tree for their prejacents at all, instead constituting separate utterances and attaching to elided material like ‘I know that’ or ‘I said that’. For present purposes, the details of the right syntactic account don't really matter, so long as it is seen that positing one or another of these accounts would suffice to explain the data adduced below: in particular, no ambiguity of what I earlier called the semantic content of the lexical entry for ‘because’ is required to account for the data.Footnote26 But we need to allow adverbial clauses like ‘frankly’ to modify speech acts anyway, so the solution I propose here has at least some independent motivation.Footnote27 Moreover, since there is no widely accepted, off-the-shelf syntactic solution for dealing with comments on preceding utterances, predicating the present analysis on the full development of a widely acceptable solution would bog us down in an inescapable morass of technical details.Footnote28 But the shape of the proposal, as represented in Figure , should be perfectly clear.

3. Syntactic differences

When we consider the relationship between ‘because’ clauses and their prejacents in content, epistemic, and act uses, we find that the different cases are marked by different grammatical or syntactic relations.Footnote29 There are two different sources of evidence for this claim that I will discuss here.Footnote30 The first source of evidence is the range of constructions in which epistemic and act uses of ‘because’ can occur. The second source of evidence is ordering restrictions on stacked ‘because’ clauses. Once we understand the differences in the syntactic roles of the ‘because’ clause in its content, epistemic, and act uses, we'll be ready for the arguments of Section 4 to the effect that ‘because’ makes the same semantic contribution in all of them.

3.1. Distributional differences

First for the constructions. I focus here on six kinds of constructions – represented by (20-b)–(20-g) – in which content ‘because’ can appear, some of which do not admit epistemic or act readings.Footnote31 The possibility of appearing in all of these constructions is characteristic of a grammatical subcategory of adverbial phrases that Quirk et al. (Citation1985) call adjuncts. The failure of epistemic and act uses of ‘because’ to appear in all of them, then, would be evidence that those uses are somehow grammatically or syntactically distinct from the causal uses of ‘because’ in (20).Footnote32

| (20-a) | Hilda helped Tony because he was injured. | ||||

| (20-b) | It was because he was injured that Hilda helped Tony. | ||||

| (20-c) | Did Hilda help Tony because he was injured or because she wanted to please her mother? | ||||

| (20-d) | Hilda didn't help Tony because he was injured but because she wanted to please her mother. | ||||

| (20-e) | Hilda helped Tony only because of his injury. | ||||

| (20-f) | Hilda helped Tony because of his injury and so did Grace. | ||||

| (20-g) | Why did Hilda help Tony? Because of his injury. | ||||

In (20-b)–(20-g), we see the ‘because’ clause being the focus of a cleft sentence, being the basis of contrast in alternative interrogation or negation, being focused by ‘only’, coming within the scope of the pro-form ‘so did’, and being elicited by a question.Footnote33 Epistemic and act uses of ‘because’ are in fact not possible in some of these constructions.

I will limit my comments here to those constructions in which epistemic and act ‘because’ cannot appear.Footnote34 In particular, epistemic and act ‘because’ cannot appear in the focus of cleft sentences ((21-b)), as the basis of contrast in alternative negation ((21-c)), or within the scope of ‘so VP’ pro-forms ((21-d)).Footnote35

| (21-a) | He likes her, because he brought her moss. | ||||

| (21-b) | ?It was because he brought her moss that he likes her. | ||||

| (21-c) | #He doesn't like her, because he brought her moss but because she's nice to him. | ||||

| (21-d) | ?He likes her, because he brought her moss and so did Grace. | ||||

The only reading of the construction in (21-b), for example, is causal: the construction itself grammatically excludes its being uttered with comma intonation, so no epistemic reading of its ‘because’ clause is available. (I mark the example with a question mark to highlight the implausibility of the causal reading.)

Comma intonation is possible for (21-c), but that does not exactly help make an epistemic use of ‘because’ the subject of alternative negation, as the intonational pattern limits the scope of the negation in (21-c) to its prejacent. Its first ‘because’ clause thus cannot be the focus of alternative negation. In fact, to yield a potentially felicitous sentence, ‘and’ should be used instead of the contrastive ‘but’ to conjoin the two ‘because’ clauses. That felicitous sentence, though, would just be a different construction than the alternative negation of (20-d). The takeaway from (21-c) is thus that alternative negation is a construction in which epistemic ‘because’ cannot appear.

(21-d), when uttered with comma intonation, has a grammatical but extremely implausible reading on which epistemic ‘because’ takes scope over the ‘so VP’ pro-form: the epistemic reading of (21-d) is true only if the conjunctive fact that he and Grace both brought her moss somehow explains the speaker's being in the position to assert that he likes her. But the takeaway from (21-d) is just that we have another construction in which epistemic ‘because’ cannot appear, namely, within the scope of the pro-form ‘so did’.

This is all evidence, assuming that Quirk et al.'s classification scheme cuts the syntactic world at its joints, that epistemic ‘because’ is grammatically distinct from adjuncts like content ‘because’. Similar evidence for act ‘because’, showing that act ‘because’ is similarly grammatically distinct from adjuncts, is easy to produce.Footnote36 The different uses of ‘because’ in the linguists' taxonomy are, in other words, syntactically different, in the way described above in Section 2. But we need not rely on Quirk et al.'s characterization cutting the syntactic world at its joints. We have an independent source of evidence of a difference in attachment height.

3.2. Stacking restrictions

Restrictions on the order in which ‘because’ clauses can be stacked is that independent source of evidence.Footnote37 Let's start with an easy case.

| (22) | Johan kicked the ball on the floor between the cones. | ||||

The prepositional phrases in (22) are stacked so that the interpretation of ‘on the floor’ can restrict the interpretation of ‘between the cones’. If we interpret ‘on the floor’ as modifying the NP ‘the ball’, then ‘between the cones’ can modify either the NP ‘the ball on the floor’ or the VP ‘kicked the ball on the floor’. But if we interpret ‘on the floor’ as an adjunct modifying the VP ‘kicked the ball’, then ‘between the cones’ has to modify the VP ‘kicked the ball on the floor’. That is, it's not possible for ‘between the cones’ to modify the NP ‘the ball’ or the NP ‘the ball on the floor’ if ‘on the floor’ modifies the VP ‘kicked the ball’. To put this in terms of attachment height, if ‘on the floor’ attaches above ‘kicked’ by modifying the VP ‘kicked the ball’, then ‘between the cones’ cannot get back below ‘kicked the ball on the floor’ to modify an NP (namely, ‘the ball’ or ‘the ball on the floor’). It is instead forced higher in the tree.

This example in mind, consider stacked ‘because’ clauses.

| (23) | You went to the casino because you're addicted to gambling, because I saw you. = [Assert (You went to the casino because you're addicted to gambling)] because I saw you.Footnote38 | ||||

The first ‘because’ phrase in (23) has to be interpreted as a content ‘because’, since there's no indication of comma intonation leading into it. The second ‘because’ phrase is most naturally interpreted as an epistemic use of ‘because’, given the content of its explanans phrase (‘I saw you’). But given that the first ‘because’ clause attaches low in the tree, there is no grammatical reason that a second ‘because’ clause can't also attach low enough to receive a causal interpretation.

| (24) | You went to the casino because you're addicted to gambling(,) because your addiction is compelling. = (You went to the casino because you're addicted to gambling) because your addiction is compelling. | ||||

Thus a causal interpretation of the second ‘because’ clause in (24), on which it explains the explanatory connection between the prejacent and the first ‘because’ clause, is available. Notice that the presence of comma intonation is irrelevant to the possibility of interpreting the second ‘because’ clause as causal. All that comma intonation does is make epistemic and act readings possible. Thus, if the second ‘because’ clause of (24) is uttered with comma intonation, the sentence has the following epistemic reading: (the speaker's knowing) that the gambler's addiction is compelling is the reason why the speaker is in the position to know that the gambler's addiction (rather than, say, a rational decision-making process) was the reason why the gambler went to the casino.Footnote39 Convoluted though that reading my seem in the abstract, it can be reasonable in the right context (e.g. an intervention with a gambling addict).

However, a content ‘because’ clause cannot scope over an epistemic or act ‘because’ clause.

| (25) | You went to the casino, because I saw you because you're addicted to gambling. | ||||

On the only grammatical interpretations of (25), ‘because you're addicted to gambling’ modifies the S ‘I saw you’. (The parallel to this for (22) would be for ‘between the cones’ to modify ‘on the floor’ directly, and then for the resulting complex prepositional phrase to modify either the NP ‘the ball’ or the VP ‘kicked the ball’.) The second ‘because’ clause of (25), that is, cannot modify the S ‘You went to the casino, because I saw you’. Now, using comma intonation does allow a second ‘because’ clause to scope outside a first epistemic or act ‘because’ clause, but the second ‘because’ clause cannot then get a content interpretation.

| (26) | You went to the casino, because I saw you, because I am in the habit of reporting my reasons for saying things. | ||||

The second ‘because’ clause in (26) is, as far as I can tell, an act use of ‘because’. It does not seem to be possible for a content ‘because’ clause to take scope outside an epistemic or act use of ‘because’. In fact, I think the right thing to say here is that the act ‘because’ just is the content ‘because’ when it gets high enough in the tree. But for now what is important is that these stacking restrictions are dispositive evidence of a difference in attachment height.

The difference in attachment height established here explains the need for comma intonation in epistemic and act uses of ‘because’. Epistemic and act uses of ‘because’ are so high in the tree that we might well think of them as not even part of the same utterance as their prejacents. Comma intonation, then, would be required to separate what we might think of as a first utterance (of a stand-alone “prejacent”) from a second utterance that follows it and comments on it. This two-utterances conception is an alternative to the high-attachment view generally advanced in this paper; I don't have evidence to rule out the two-utterances alternative, but all I am committed to saying in this paper is that positing attachment to assertions themselves and possibility modals above them would also suffice to explain the data described here. Rather than attempting to adjudicate between these two explanations of the need for comma intonation, I henceforth assume that the existence of some syntactic difference of the kinds discussed has been established, and turn to offering some reasons to think that content, epistemic, and act uses of ‘because’ all involve lexical entries with the same semantic content.

4. Unifying the linguists' taxonomy

In this section, I argue that content, epistemic, and act uses of ‘because’ are not distinguished by a difference in the semantic contribution of ‘because’. A better explanation is that act ‘because’ just is content ‘because’ when it appears above a certain height in a syntactic tree, attaching to, e.g. a speech act. Epistemic ‘because’ is again content ‘because’ when it attaches to a possibility modal above such an act. The difference between these uses is thus in their explananda. That is, content, epistemic, and act ‘because’ are in complementary distribution, which is to say that they are found in mutually exclusive environments. This will be enough to unify them.

Imagine trying to explain, with a content ‘because’ clause, some feature of a speech act you have just made.

| (27) | What are you doing tonight? I'm asking you because there's a movie on. | ||||

The ‘because’ clause of (27) explains why the speaker asked the question. But this is just what utterances of (3) do.Footnote40 So here, where the explanandum of an act ‘because’ clause is explicitly represented, the ‘because’ clause becomes a content use. I claim this is a general feature of act ‘because’ sentences.

| (12) | ‘Mongeese’, because it sounds better than ‘mongooses’. | ||||

| (28) | I said ‘mongeese’ because it sounds better than ‘mongooses’. | ||||

| (15) | (After knocking softly) Because I don't want to wake their baby. | ||||

| (29) | I knocked softly because I don't want to wake their baby. | ||||

Apparent differences between causal ‘because’ and act ‘because’, if this is right, can be attributed to the linguistic contexts in which they appear. This is not polysemy – at least, it is not the kind of polysemy that correlates with any genuinely semantic complexity of ‘because’ – in that the sense of ‘because’ used is precisely the same in both cases. What accounts for the apparent difference in meaning is rather a difference in what is being explained.Footnote41

It is important for the semantic point that I want to make that causal uses of ‘because’ are in complementary distribution with epistemic and act uses of ‘because’. The move I want to make here – explaining away apparent differences in meaning by appealing to differences in what is being explained – is reminiscent of Quine's argument that ‘exist’ is monosemous.Footnote42 ‘Exist’ need not be treated as ambiguous between predicating spatiotemporal existence, as of chairs in (30), and predicating non-spatiotemporal existence, as of numbers in (31).Footnote43

| (30) | Chairs exist. | ||||

| (31) | Numbers exist. | ||||

Rather, material objects and numbers exist in a single sense. The fact that 'some very unlike things' exist is not evidence undermining the semantic unity of ‘exist’.Footnote44 Instead, Quine claims, apparent differences in the meaning of ‘exist’ are due solely to differences in the things that exist themselves. And this is precisely analogous to what I am now claiming about the apparent differences in the meaning of ‘because’ as it appears in its content, epistemic, and act uses.

Let's apply this analysis to an example from the wild.

| (32) | Jann S. Wenner: Did you know [‘I can't get no satisfaction from the judge’ was a line from Chuck Berry's ‘30 Days’] when you wrote [‘Satisfaction’]? Mick Jagger: No, I didn't know it, but Keith might have heard it back then, because it's not any way an English person would express it. I'm not saying that he purposely nicked anything, but we played those records a lot.Footnote45 | ||||

The italicized text in (32) is a real-life example of an act use of ‘because’. The basic idea behind my view is that Jagger is there giving an explanation of why he uttered the prejacent ‘Keith might have heard it back then’. That this is what Jagger is doing is confirmed by his continuation in the last sentence of (32), where he further clarifies the purpose of his utterance. But try to recover a straightforward content reading of the ‘because’ clause in the italicized text in (32). The sentence would then be rather odd, as the fact that English people didn't say ‘I can't get no’ seems like it could have played no explanatory role at all in making it possible for Keith Richards to have heard the Chuck Berry song at the relevant time in the past. But that's the reading of the sentence to which we are forced when we try to interpret the ‘because’ clause as what we have been calling a content use of ‘because’. That is, we are forced to interpret the prejacent of content ‘because’ clauses differently than the prejacents of epistemic and act ‘because’ clauses. Given the syntactic differences between the different kinds of uses of ‘because’ we have been discussing, there is simply no reason to posit, in addition, any differences in the semantic content of lexical entries for ‘because’ itself.Footnote46 Pace Viebahn and Vetter (Citation2016), who take differences in logical form to be evidence of polysemy, it is not that ‘because’ has a different meaning here, but that its single meaning applies to very different things: contents vs. acts of assertion vs. the possibility of those assertions.

By this point, I hope to have convinced you that epistemic and act uses of ‘because’ plausibly involve the same sense of ‘because’ that is operative in its standard content uses. It remains to record the senses of ‘because’ that are not unified by the account presented here.

5. Other sources of polysemy

Polysemy in explanatory talk can arise from other sources than have been considered here.Footnote47 The class of uses of ‘because’ that I discuss at length in Shaheen (Citation2017a, Citation2017b), represented here by (33), involves a non-causal, grounding-related meaning of ‘because’ that is distinct from the meaning of ‘because’ in any of the preceding examples.

| (33) | The pious is pious because it is loved by the gods.Footnote49 | ||||

In particular, Shaheen (Citation2017a) shows that metaphysical explanatory sentences like (33) use a different sense of ‘because’ than causal explanatory sentences, relying especially on conjunction reduction tests that cannot be applied in the cases of interest here.Footnote50 I also set aside for another occasion discussion of examples like (34), which might properly be called evidential uses of ‘because’, where what is expressed is an evidential connection between two propositions rather than the reason why the speaker was in the position to make the assertion.

| (34) | Your keys might be in the desk because I haven't looked yet. | ||||

But ‘because’ is subject to ambiguity on one other dimension that does deserve some comment here.

| (35) | The ice is melting because the temperature is rising.Footnote51 | ||||

| (36) | Joan doesn't lend Ted money because he'd never pay her back.Footnote52 | ||||

One might think that (35) is causal, while the only relevant reading of (36) is reasons-related, just because the prejacent of (36) picks out an action. I don't think this distinction is semantically encoded in ‘because’. For one thing, as discussed above, philosophers generally avoid positing ambiguity in cases of apparent differences in meaning associated with sort-specific readings, and for good reason. For another, conjunction reduction tests do not show the evidence of ambiguity here that the ambiguity theorist would predict they would.

| (37) | Andrew voted for Trump because he dislikes immigrants and can't spot unfitness for office. | ||||

The felicity of (37), which cites both a reason for and a cause of Andrew's voting for Trump, suggests that content ‘because’ is semantically general with respect to the reason–cause distinction at this level. At least, I think there is a sense of ‘because’ for which this is right.

But consider again (36). There is a reading of (36) that is true only if Joan knows that Ted would never pay her back. There is another reading of (36) that does not require Joan to know that Ted would never pay her back. Maybe Joan's occurrent reason for not lending Ted money is that Alex dislikes Ted, while in fact Alex dislikes Ted because Ted would never pay Joan back. In that case, there is an explanation of Joan's not lending Ted money that involves the fact that Ted would never pay Joan back, and thus a true reading of (36) that does not require Joan to know that Ted would never pay her back. The issue here is not that content ‘because’ can only be interpreted as having a non-causal reasons-related sense in sentences with prejacents that refer to actions. The issue here is rather that, in sentences with prejacents that refer to actions, content ‘because’ seems to be ambiguous between a meaning that requires the agent to know her reason and a meaning that does not.Footnote53

This distinction between uses of content ‘because’ that entail the agent's knowledge of her reason, on the one hand, and uses without that entailment, on the other, has been left under the rug so far. Straightening out which of these it is that act and epistemic ‘because’ reduce to is still a matter for future research. One complication in settling the issue is that epistemic and act ‘because’ stereotypically explain things about one's own utterances. So even if epistemic and act uses of ‘because’ do not involve the same sense of ‘because’ as uses of content ‘because’ that entail the agent's knowledge of her reason, speakers can only felicitously assert them when they know them. But there is one consideration we may be able to bring to bear on this question. In the discussions of epistemic uses of ‘because’ in (17) and (24), the parenthetical qualification ‘(the speaker knows that)’ seemed to be important for the plausibility of the analysis. Perhaps this is a reason to think that epistemic uses of ‘because’ are semantically unified with those content uses of ‘because’ that entail that the agent knows her reason. But for act uses of ‘because’, it seems entirely open for theorists to choose either possibility. That is, there may be no fact of the matter here, though there does seem to be a fact of the matter about whether we need to posit an ambiguity in the semantic content of lexical entries for ‘because’ to account for the difference between content, epistemic, and act ‘because’. We do not.Footnote54

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 See Shaheen (Citation2017a, Citation2017b).

2 See, for example, Morreall (Citation1979), Quirk et al. (Citation1985), Sweetser (Citation1990), Kanetani (Citation2007), and Kanetani (Citation2012). My category of act uses of ‘because’ includes, for reasons that will become clear, both Sweetser's speech-act ‘because’ and Kanetani's metalinguistic ‘because’. Though it will not come into play in this paper, linguists discussing epistemic meanings in general (i.e. not specifically for ‘because’) sometimes make a further distinction between meanings having to do with the speaker's knowledge (or other propositional attitudes like belief) and evidential meanings, which have to do with information sources or evidence: see Traugott (Citation1989, 32–33) for citations and some discussion.

3 The example belongs to Sweetser (Citation1990, 31). She sometimes presents the example with different punctuation, e.g. ‘What are you doing tonight, because there's a good movie on.’ at Sweetser (Citation1990, 77).

4 My syntactic proposal is similar to that of Schleppegrell (Citation1991). But on my account, all of these uses retain a common semantic element, whereas Schleppegrell allows the ‘because’ of (2) and (3) to mean something having nothing to do with causal explanation.

5 This is done explicitly for epistemic uses by Schnieder (Citation2011, Section 1.2). Bromberger (Citation1992, 75) sets aside all ‘why’-questions that contain parenthetical verbs in the sense of Urmson (Citation1952), some of which I think are properly thought of as act ‘why’-questions. But it is more common to simply ignore epistemic and act uses. Dakin (Citation1970, 213–214) is the rare exception who recognizes that epistemic ‘because’ sentences can be handled along the lines of content ‘because’ sentences, but he does not develop the idea, which this paper tries to do.

6 Ambiguity posits are to be avoided where possible, in accordance with the Occamist injunction: ‘do not multiply senses beyond necessity.’ (For references, see Shaheen, Citation2017a, fn. 13).

7 I do, however, join others in restricting my attention to indicative ‘why’-questions and indicative ‘because’-sentences. Insofar as the strategy of the present paper is to adduce differences in explananda to explain away apparent differences in the meaning of ‘because’ in various contexts, I would seem to have a promising strategy for extending the treatment to sentences with subjunctive explananda phrases. But working out the details of that treatment is a project for another paper.

8 With respect to lexical semantics, some authors use ‘ambiguity’ in a way that covers homonyms (like ‘bank’) but not polysemes (like ‘healthy’). As in Shaheen (Citation2017a), I use ‘ambiguity’ as an umbrella term for both homonymy and polysemy.

9 Schroeder (Citation2008), which develops an elaborate expressivist semantics in pursuit of the idea that logical connectives require a univocal treatment, is a case-in-point here. The ambiguity posit that Schroeder is trying to avoid is analogous to the distinction between propositional negation and property negation, a distinction that it is costless for expressivists to accept, since it has to be accepted for English ‘not’ by everyone anyway. For the claim that a univocal treatment of connectives is required, see, e.g. Schroeder (Citation2008, 90 and 97).

10 (4) is (4.5) at Asher (Citation2011, 106), given as a standard example of a lexical entry.

11 See, e.g. Cruse (Citation1986, Section 3.6) and Sennet (Citation2016, Sections 3.1–3.2).

12 Cf. fn. 26.

13 Morreall (Citation1979)'s (6).

14 See the discussion of “style disjunct because” at Section 15.21 of the standard American English grammar, Quirk et al. (Citation1985).

15 Sweetser (Citation1990), Section 4.1.2 follows Chafe (Citation1984) in explaining the need for comma intonation by appealing to presuppositional differences between content and epistemic ‘because’ sentences: the sentences with comma intonation do not presuppose their prejacents, whereas the sentences without comma intonation do.

16 An anonymous referee suggests that the speaker might be better interpreted as justifying her assertion. It seems to me that many kinds of reasons can be offered to justify an assertion, only some of which will match my account of epistemic uses of ‘because’, while others might match my account of act uses of ‘because’. All that I want to commit myself to here is that whatever justifications can be offered using ‘because’ can be accounted for without positing ambiguities relating to what, in the previous section, I called the semantic content of lexical entries for ‘because’.

17 From Declerck, Reed, and Cappelle (Citation2006, 553).

18 Metalinguistic uses are plausibly essentially echoic, in the sense that they report something that was said and explain it (cf. Carston, Citation1996 on metalinguistic negation), in a way that (3) does not seem to be and (15) cannot possibly be. Barbara Dancygier (Citation1992, Citation1999) argues, partially on cross-linguistic grounds, that the speech-act ‘because’ of (3) can be distinguished from the ‘because’ of (10), and both of these again from the properly metalinguistic ‘because’ of (11)–(13), which introduces clauses commenting specifically on linguistic form. In any case, my category of act uses of ‘because’ is at least as broad as Dancygier's category of ‘conversational’ uses (see Dancygier, Citation1992, 71), and includes all of what Carston (Citation1999) and Noh (Citation2000) might classify as ‘metarepresentational’ uses.

19 This is not to say that a theory of ‘why’ or ‘because’ sentences must be fully general. For one thing, a ‘why’-question is only felicitously answered with an epistemic or act ‘because’ sentence if the ‘why’-question is an echo, i.e. if it repeats an utterance in asking why it was said. For another, in this paper, I set aside non-indicative ‘why’-questions and ‘because’ sentences. See fn. 7 and Section 5.

20 Discussion of the parenthetical ‘(the speaker knows that)’ raises complicated questions, the full resolution of which is beyond the scope of this paper, but see Section 5.

21 For an account of the relationship between reasons why and explanation, see Skow (Citation2016), especially ch. 2. But nothing here hangs on the correctness of what Skow says there.

22 Some readers might think this means the sentences provide different kinds of explanation, since, e.g. act ‘because’ will provide explanations of acts and content ‘because’ will provide explanations of truths or facts. ((35) is perhaps a better example for illustrating this contrast than (16).) But this turns out not to matter. While it is certainly true that philosophical accounts of explanation often involve commitments about the ontological category of the relata of the explanatory relation, this is a paper about the meaning of ‘why’ and ‘because’, and explanatory terminology is in general just not ambiguous with respect to the ontological category of explananda.

If this is surprising to readers, it is only because many philosophers systematically misunderstand precisifications of concepts to be disambiguations of word meanings. But, as I argue in Shaheen (Citation2017b, Section 2), precisification is not disambiguation. The mere fact that fine distinctions can be drawn between different precise concepts that words could be stipulated to have does not suffice to show that those words actually have those meanings as a matter of empirical fact. Rather, ambiguity claims have to be adjudicated using the kinds of tests for ambiguity discussed in Shaheen (Citation2017a) (Cf. fn. 46). Thus, for instance, Jenkins (Citation2008, 64–65) is correct, as a matter of lexical semantics, about the univocality or semantic generality of ‘explanation’ with respect to the object-fact distinction.

23 Adapted from Sennet (Citation2016, Section 3.2.1).

24 The relationship between prosody and attachment height is explored in a wide variety of works, from Jackendoff (Citation1972, Section 6.6) to Beach (Citation1991), Price et al. (Citation1991), Fodor (Citation1998), Hirschberg and Avesani (Citation2000), Jun (Citation2003), and Grillo and Turco (Citation2016), and the interaction between prosody and quantifier scope (see Herburger, Citation2000, 243, n. 10) is another instance of the same phenomenon. See also the note at Cinque (Citation1999, 32) that ‘higher’ adverbs (e.g. ‘frankly’) can be licensed in otherwise infelicitous positions through the use of comma intonation (Cf. fn. 28). Thanks to an anonymous referee for emphasizing that prosodic differences are themselves already evidence of structural ambiguity.

25 Thanks are due to Maribel Romero for discussion of this proposal.

26 The syntactic suggestions made here and in Section 3 mirror, to an extent, the view of the relationship between epistemic and root modality championed by Hacquard (Citation2010) and endorsed by Kratzer (Citation2012): an epistemic modal is distinguished from the corresponding root modal in that a single uniform lexical entry, written so as to be able to appear at multiple levels of a phrase tree, appears higher in the phrase tree in the epistemic case than in the root case. But in the present case, the attachment site is proposed to be even higher.

27 See, e.g. the treatment of ‘frankly’ and similar phrases as modifiers that attach to ‘the symbol “X”… which can be taken to refer to the speaker's utterance’ at Fortuin and Geerdink-Verkoren (Citation2019, 169–171).

28 A syntactician might hope to nail down a precise attachment site for epistemic and act ‘because’ in the cartographic framework of Rizzi (Citation1997) and Cinque and Rizzi (Citation2010). But Cinque himself forebears from any stronger commitment on the attachment site of ‘frankly’ than to note that it is higher than everything else he considers: see Cinque (Citation1999, 12–13).

29 Thanks are due to Ezra Keshet for discussion of and advice about the matters discussed in this section.

30 Interaction with tense and aspect are additional sources of evidence, not discussed here due to limitations of space.

31 The examples in (20) are adapted from Quirk et al. (Citation1985, Section 8.25).

32 According to Quirk et al. (Citation1985, Section 15.21), the epistemic uses of ‘because’ fall in a distinct grammatical category of style disjuncts, which coheres with the story I tell here.

33 The description of the constructions given here is minimally adapted from Quirk et al. (Citation1985, Section 8.134).

34 I am indebted to Eric Lormand for pressing me to be clear about the importance of comma intonation.

35 I present here the data only for epistemic ‘because’. The data for act ‘because’ is easy to reconstruct starting with (i).

| (i) | ‘Reputed’, because I have never seen it. | ||||

To make it explicit, the data is broadly similar but a bit more extreme, since the act version of (21-b) comes out ungrammatical.

36 See fn. 35.

37 See Bhatt and Pancheva (Citation2006, Section 5.3) for an application of this kind of test to different varieties of ‘if’ clauses.

38 The operator ‘Assert’ here is the act of asserting the prejacent: see Section 2 for discussion.

39 On the parenthetical ‘(the speaker's knowing)’, see Section 5.

40 In fact, (27) is modeled on what Sweetser (Citation1990) claims the meaning of (3) is.

41 As the lexicalization of a discourse relation (cf. Section 2), ‘because’ has to make a semantic contribution that can connect segments of a discourse. As the lexicalization of Explanation in particular, ‘because’ connects segments of a discourse by identifying one segment as the explanation of another. But nothing in the role of a discourse relation requires that discourse relations to be so finely individuated that connecting the content of an assertion to its explanation is a different kind of connection than connecting, say, the act of an assertion to its explanation. In both cases, what ‘because’ says is just that this thing explains that one. The difference in the lambda types of, e.g. contents and acts, then, is consistent with there being no variation in the semantic content of the lexical entry for ‘because’, and with its meaning being, in an important sense, the same across the kinds of cases considered in this paper. Cf. fn. 22. Thanks to an anonymous referee for encouraging me to say more here.

42 It is also reminiscent of the argument in Goodenough (Citation1956) from complementary distribution to underlying semantic unity, which he advances by analogy with the cases of allophones in phonology and allomorphs in morphology: see Goodenough (Citation1956, 197). Schmerling (Citation1978, 310), fn. 9 also alludes to this kind of argument. See the discussion of ‘sort specific readings’ at Pinkal (Citation1995, 94–97) for an overview of the terrain here.

43 Quine (Citation1960, Section 27).

44 Quine (Citation1960, 130).

45 Wenner (Citation1995). Emphasis added. Thanks to Sara Aronowitz for the example.

46 These syntactic differences also explain the behavior of ‘because’ with respect to standard tests for ambiguity. Due to space considerations, a long discussion of such tests has been omitted, but the following claims deserve to be preserved:

| (1) | Contradiction tests, which check whether the same expressions can be simultaneously asserted and denied without contradiction, suggest that ‘because’ is ambiguous in some way; but with respect to the linguists' taxonomy, they do not establish that there is any ambiguity of ‘because’ beyond a difference in type located in the logical form of lexical entries for ‘because’. (The tests, which can be confounded in a variety of ways, are not sensitive enough to establish that.) | ||||

| (2) | Conjunction reduction tests are frustrated in the case of this taxonomy of uses of ‘because’ by the syntactic differences between the uses. So-called crossed readings disappear even before second occurrences of the term ‘because’ are eliminated from partially reduced conjunctions, because the partial reduction leaves only one occurrence of the prejacent, forcing interpretations to settle on a single syntactic position for the conjunction of ‘because’ clauses attaching to it. | ||||

| (3) | The cross-linguistic evidence is too muddled to be useful. For example, Zuffery (Citation2012) shows that French ‘parce que’ has content, epistemic, and act uses, especially in spoken French, contrary to what much of the literature has presupposed. | ||||

But in cases not complicated by syntactic ambiguities, the contradiction and conjunction reduction tests can be very sensitive tests for purely semantic ambiguities, pace the arguments of Viebahn (Citation2018), which implicitly rely upon the false assumption that pragmatically dispreferred readings are not present. Thanks are due to Emanuel Viebahn for discussion (although the reader is free to imagine that he might disagree with the preceding sentence). For discussion of these tests in connection with some of the putative ambiguities of ‘because’ mentioned in Section 5, see Shaheen (Citation2017a) and Cox (Citation2017, Chap. 3).

47 In addition to the cases discussed here for ‘because’, explanatory talk involving ‘explained’ has been argued to have one sense corresponding to an ontic conception of explanation as in (i), and another sense corresponding to an epistemic conception of explanation as in (ii).

(i) (a) The oxygen canisters explained the ValuJet crash in the Florida Everglades.

(b) X explained Y.

(ii) (a) The investigator explained the ValuJet crash in the Florida Everglades [to the panel].

(b) X explained Y [to Z].

See Şerban (Citation2017) for discussion, but note that the verb ‘explained’ in (ii) takes an optional prepositional phrase, though the verb ‘explained’ in (i) does not. This distinction is confined to a footnote in view of the fact that ‘because’ does not allow analogues of (ii). (The examples in this footnote are derived from Wright (Citation2012)'s (7) and (8).)

49 Derived from Plato, Euthyphro 10a.

50 Cf. fn. 46.

51 Morreall (Citation1979)'s (1).

52 Morreall (Citation1979)'s (5).

53 Though it is fine for present purposes if the two readings of sentences like (36) can be explained without positing any ambiguity of content ‘because’, Cox (Citation2017, Chap. 3) argues that ‘because’ is indeed ambiguous along these lines, appealing in part to the tests for ambiguity discussed in Shaheen (Citation2017a) and mentioned in fn. 46.

54 This paper provides a much improved account of data first discussed in Shaheen (Citation2014, Chap. 3). Thanks are due to Sara Aronowitz, Sören Häggqvist, Brendan Balcerak Jackson, Ezra Keshet, Boris Kment, David Manley, Maribel Romero, Stefan Roski, Benjamin Schnieder, Rich Thomason, audiences in Ann Arbor, Barcelona, Hamburg, Stockholm, and Zurich, and three anonymous referees for Inquiry.

References

- Asher, N. 2011. Lexical Meaning in Context: A Web of Words. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Asher, N., and A. Lascarides. 1995. “Lexical Disambiguation in a Discourse Context.” Journal of Semantics 12 (1): 69–108. doi: 10.1093/jos/12.1.69

- Beach, C. M. 1991. “The Interpretation of Prosodic Patterns At Points of Syntactic Structure Ambiguity: Evidence for Cue Trading Relations.” Journal of Memory and Language 30 (6): 644–663. doi: 10.1016/0749-596X(91)90030-N

- Bhatt, R., and R. Pancheva. 2006. “Conditionals: Chap. 16”. In The Blackwell Companion to Syntax, edited by M. Everaert and H. C. van Riemsdijk, Blackwell Handbooks in Linguistics, Vol. 1, 638–687. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

- Bromberger, S. 1992. “Why-Questions: Chap. 3.” In On What We Don't Know We Don't Know, edited by S. Bromberger, 75–100. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Carston, R. 1996. “Metalinguistic Negation and Echoic Use.” Journal of Pragmatics 25: 309–330. doi: 10.1016/0378-2166(94)00109-X

- Carston, R. 1999. “Negation, ‘presupposition’ and Metarepresentation: a Response to Noel Burton-Roberts.” Journal of Linguistics 35 (2): 365–389. doi: 10.1017/S0022226799007653

- Chafe, W. 1984. “How People Use Adverbial Clauses.” In Proceedings of the Tenth Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society, Berkeley, CA, 437–449.

- Cinque, G. 1999. Adverbs and Functional Heads: A Cross-Linguistic Perspective. Oxford Studies in Comparative Syntax, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Cinque, G., and L. Rizzi. 2010. “The Cartography of Syntactic Structures: Chap. 3.” In The Oxford Handbook of Linguistic Analysis, edited by B. Heine and H. Narrog, 51–65. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Couper-Kuhlen, E. 1996. “Intonation and Clause-Combining in Discourse: The Case of Because.” Pragmatics 6 (3): 389–426.

- Cox, R. 2017. “Knowing Why: Essays on Self-Knowledge and Rational Explanation.” PhD thesis, Australian National University.

- Cruse, D. A. 1986. Lexical Semantics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Dakin, J. 1970. “Explanations.” Journal of Linguistics 6 (2): 199–214. doi: 10.1017/S0022226700002607

- Dancygier, B. 1992. “Two Metatextual Operators: Negation and Conditionality in English and Polish.” Proceedings of the Eighteenth Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society: General Session and Parasession on The Place of Morphology in a Grammar, Berkeley, CA, 61–75.

- Dancygier, B. 1999. Conditionals and Prediction: Time, Knowledge and Causation in Conditional Constructions. Cambridge Studies in Linguistics, Vol. 87. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Declerck, R., S. Reed, and B. Cappelle 2006. The Grammar of the English Verb Phrase: Volume 1: The Grammar of the English Tense System: A Comprehensive Analysis. Topics in English Linguistics, Vol. 60.1. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

- Fodor, J. D. 1998. “Learning to Parse.” Journal of Psycholinguistic Research 27: 285–319. doi: 10.1023/A:1023258301588

- Fortuin, E., and H. Geerdink-Verkoren. 2019. Universal Semantic Syntax: A Semiotactic Approach. Cambridge Studies in Linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge Studies in Linguistics. Cambridge University Press.

- Goodenough, W. H. 1956. “Componential Analysis and the Study of Meaning.” Language 32 (1): 195–216. doi: 10.2307/410665

- Grillo, N., and G. Turco. 2016. “Prosodic Disambiguation and Attachment Height.” In Proceedings of Speech Prosody, Boston, MA, 8.

- Hacquard, V. 2010. “On the Event Relativity of Modal Auxiliaries.” Natural Language Semantics 18 (1): 79–114. doi: 10.1007/s11050-010-9056-4

- Herburger, E. 2000. What Counts: Focus and Quantification. Linguistic Inquiry Monographs, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Hirschberg, J., and C. Avesani. 2000. “Prosodic Disambiguation in English and Italian: Chap. 4.” In Intonation, edited by A. Botinis, 87–95. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Horn, L. 1985. “Metalinguistic Negation and Pragmatic Ambiguity.” Language 61 (1): 121–174. doi: 10.2307/413423

- Jackendoff, R. S. 1972. Semantic Interpretation in Generative Grammar. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Jenkins, C. S. 2008. “Romeo, René, and the Reasons Why: What Explanation Is.” Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society 108 (1): 61–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9264.2008.00236.x

- Jun, S.-A. 2003. “Prosodic Phrasing and Attachment Preferences.” Journal of Psycholinguistic Research32: 219–249. doi: 10.1023/A:1022452408944

- Kanetani, M. 2007. “Causation and Reasoning: A Construction Grammar Approach to Conjunctions of Reason.” PhD thesis, University of Tsukuba, Tsukuba, Japan.

- Kanetani, M. 2012. “Another Look At the Metalinguistic Because-Clause Construction.” Tsukuba English Studies 31: 1–18.

- Kratzer, A. 2012. Modals and Conditionals. Oxford Studies in Theoretical Linguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Morreall, J. 1979. “The Evidential Use of Because.” Papers in Linguistics 12 (1–2): 231–238. doi: 10.1080/08351817909370469

- Noh, E.-J. 2000. Metarepresentation: A Relevance-Theory Approach. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Co..

- Pinkal, M. 1995. Logic and Lexicon. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers. Translated by Geoffrey Simmons.

- Price, P. J., M. Ostendorf, S. Shattuck-Hufnagel, and C. Fong. 1991. “The Use of Prosody in Syntactic Disambiguation.” Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 90 (6): 2956–2970. doi: 10.1121/1.401770

- Quine, W. V. O. 1960. Word and Object. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Quirk, R., S. Greenbaum, G. Leech, and J. Svartvik. 1985. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Langugae. London: Longman.

- Rizzi, L. 1997. “The Fine Structure of the Left Periphery.” In Elements of Grammar: Handbook in Generative Syntax, edited by L. Haegeman, 281–337. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Schleppegrell, M. J. 1991. “Paratactic Because.” Journal of Pragmatics 16: 323–337. doi: 10.1016/0378-2166(91)90085-C

- Schmerling, S. 1978. “Synonymy Judgments as Syntactic Evidence.” In Syntax and Semantics, Pragmatics, Vol. 9, edited by P. Cole, 299–314. New York: Academic Press.

- Schnieder, B. 2011. “A Logic for ‘Because’.” The Review of Symbolic Logic 4 (3): 445–465. doi: 10.1017/S1755020311000104

- Schroeder, M. 2008. Being For: Evaluating the Semantic Program of Expressivism. New York: Clarendon Press.

- Sennet, A. 2016. Ambiguity. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2016 Edition).

- Şerban, M. 2017. “What Can Polysemy Tell Us About Theories of Explanation?.” European Journal of Philosophy of Science 7 (1): 41–56. doi: 10.1007/s13194-016-0142-4

- Shaheen, J. 2014. “Meaning and Explanation.” PhD thesis, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

- Shaheen, J. 2017a. “Ambiguity and Explanation.” Inquiry 60: 839–866. doi: doi:10.1080/0020174X.2016.1175379

- Shaheen, J. 2017b. “The Causal Metaphor Account of Metaphysical Explanation.” Philosophical Studies 174 (3): 553–578. doi:10.1007/s11098-016-0696-1

- Skow, B. 2016. Reasons Why. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Sweetser, E. 1990. From Etymology to Pragmatics: Metaphorical and Cultural Aspects of Semantic Structure. Cambridge Studies in Linguistics, Vol. 54. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Traugott, E. C. 1989. “On the Rise of Epistemic Meanings in English: An Example of Subjectification in Semantic Change.” Language 65 (1): 31–55. doi: 10.2307/414841

- Urmson, J. O. 1952. “Parenthetical Verbs.” Mind 61: 480–496. doi: 10.1093/mind/LXI.244.480

- Viebahn, E. 2018. “Ambiguity and Zeugma.” Pacific Philosophical Quarterly 99: 749–762. doi: 10.1111/papq.12229

- Viebahn, E., and B. Vetter. 2016. “How Many Meanings for ‘May’? The Case for Modal Polysemy.” Philosophers' Imprint 16 (10): 1–26.

- Wenner, J. S. 1995. “Mick Jagger Remembers.” Rolling Stone 723.

- Wright, C. D. 2012. “Mechanistic Explanation Without the Ontic Conception.” European Journal of Philosophy of Science 2: 375–394. doi: 10.1007/s13194-012-0048-8

- Zuffery, S. 2012. “Car, Parce Que, Puisque” Revisted: Three Empirical Studies on French Causal Connectives.” Journal of Pragmatics 44 (2): 138–153. doi: 10.1016/j.pragma.2011.09.018