ABSTRACT

Sleep disturbances are a pervasive problem among postmenopausal women, with an estimated 40 to 64% reporting poor sleep. Hypnosis is a promising intervention for sleep disturbances. This study examined optimal dose and delivery for a manualized hypnosis intervention to improve sleep. Ninety postmenopausal women with poor sleep were randomized to 1 of 4 interventions: 5 in-person, 3 in-person, 5 phone, or 3 phone contacts. All received hypnosis audio recordings, with instructions for daily practice for 5 weeks. Feasibility measures included treatment satisfaction ratings and practice adherence. Sleep outcomes were sleep quality, objective and subjective duration, and bothersomeness of poor sleep. Results showed high treatment satisfaction, adherence, and clinically meaningful (≥ 0.5 SD) sleep improvement for all groups. Sleep quality significantly improved, p < .05, η2 = .70, with no significant differences between groups, with similar results for the other sleep outcomes across all treatment arms. Comparable results between phone and in-person groups suggest that a unique “dose” and delivery strategy is highly feasible and can have clinically meaningful impact. This study provides pilot evidence that an innovative hypnosis intervention for sleep (5 phone contacts with home practice) reduces the burden on participants while achieving maximum treatment benefit.

Gary R. Elkins, Julie Otte, Janet S. Carpenter, Lynae Roberts, Lea’ S. Jackson,

Zoltan Kekecs, Vicki Patterson, und Timothy Z. Keith

Zusammenfassung: Schlafstörungen stellen bei Frauen nach der Menopause mit 40 bis 64% berichtetem schlechten Schlaf ein weit verbreitetes Problem dar. Hypnose ist eine vielversprechende Behandlung bei Schlafstörungen. In dieser Studie wurden optimale Dosierung und Anleitung für ein Hypnose Manual zur Verbesserung des Schlafs untersucht. 90 Frauen nach der Menopause mit schlechtem Schlaf wurden nach Zufall einer von 4 Behandlungsgruppen zugewiesen: 5 mal mit persönlichem Kontakt, 3 mal mit persönlichem Kontakt, 5 mal mit Telefonkontakt und 3 mal mit Telefonkontakt. Alle erhielten Audio-CDs mit Anweisungen für Hypnose zum täglichen Üben während 5 Wochen. Die Maße für die Durchführbarkeit beinhalteten Einstufungen der Behandlungszufriedenheit und der Übungspraxis. Die erhobenen Werte bezüglich des Schlafs betrafen die Qualitöt, die objektive und subjektive Dauer sowie das Unbehagen aufgrund schlechten Schlafs. Als Ergebnis zeigte sich große Zufriedenheit mit der Behandlung, Befolgung des Programms und klinisch bedeutsame Verbesserung des Schlafs (≥ 0.5 SD) in allen Gruppen. Die Schlafqualitöt verbesserte sich signifikant, p < 0.5, eta2 = .70, ohne signifikante Unterschiede zwischen den Gruppen und mit ähnlichen Ergebnissen für die anderen Schlafparameter bei allen Behandlungsarme. Vergleichbare Ergebnisse in den Telefongruppen und in den Gruppen mit persönlichem Kontakt legen nahe, dass eine einzige „Dosis“ und Anleitung wirklich machbar und von hoher klinischer Wirksamkeit sein kann. Diese Untersuchung vermittelt erste Evidenz, dass eine innovative Hypnosebehandlung (5 Telefonkontakte mit häuslichem Üben) die quälende Situation der Teilnehmer bessert und zugleich einen maximalen Behandlungsgewinn erbringt.

Alida Iost-Peter

Dipl.-Psych.

Gary R. Elkins, Julie Otte, Janet S. Carpenter, Lynae Roberts, Lea’ S. Jackson,

Zoltan Kekecs, Vicki Patterson, et Timothy Z. Keith

Résumé: Les troubles du sommeil sont un problème omniprésent chez les femmes ménopausées, environ 40 à 64% rapportant un mauvais sommeil. Léhypnose est une intervention prometteuse pour les troubles du sommeil. Cette étude a examiné la quantité et la délivrance optimales pour une intervention d’hypnose pour améliorer le sommeil. Quatre-vingt-dix femmes ménopausées ayant un mauvais sommeil ont été randomisées pour 1 è 4 interventions: 5 en personne, 3 en personne, 5 par téléphone ou 3 contacts téléphoniques. Toutes ont reçu des enregistrements audio d’hypnose, avec des instructions pour une pratique quotidienne pendant 5 semaines. Les mesures de faisabilité comprenaient les degrés de satisfaction envers le traitement et l’observance de la pratique. Les résultats concernant le sommeil étaient basés sur la qualité du sommeil, la durée objective et subjective et la gêne occasionnée par un mauvais sommeil. Les résultats ont montré une satisfaction élevée au traitement, une observance et une amélioration du sommeil cliniquement significative (≥ 0,5 ET) pour tous les groupes. La qualité du sommeil s’est considérablement améliorée, p 0,05, η2 = 0,70, sans différence significative entre les groupes, avec des résultats similaires pour les autres résultats du sommeil dans tous les bras de traitement. Des résultats comparables entre les groupes téléphone et ceux en personne suggèrent qu’une stratégie de «dose» unique et d’administration est hautement réalisable et peut avoir un impact cliniquement significatif. Cette étude fournit des preuves pilotes qu’une intervention d’hypnose innovante pour le sommeil (5 contacts téléphoniques avec une pratique à domicile) réduit le fardeau des participants tout en obtenant un bénéfice maximal du traitement.

Gérard Fitoussi, M.D.

President-Elect of the European Society of Hypnosis

Gary R. Elkins, Julie Otte, Janet S. Carpenter, Lynae Roberts, Lea’ S. Jackson, Zoltan Kekecs, Vicki Patterson, Y Timothy Z. Keith

Resumen: Los disturbios de sueño son un problema generalizado entre mujeres posmenopáusicas. Se estima que entre el 40 y 64% reportan problemas de sueño. La hipnosis es una intervención prometedora para los disturbios del sueño. Este estudio examinó la dosis óptima y la administración de una intervención hipnótica manualizada para mejorar el sueño. Se asignó de forma aleatoria a 90 mujeres posmenopáusicas con problemas de sueño a 1 de 4 intervenciones: 5 en persona, 3 en persona, 5 por teléfono o 3 contactos telefónicos. Todas recibieron la hipnosis mediante audio grabaciones, con instrucciones de práctica diaria durante 5 semanas. Las medidas de viabilidad incluyeron evaluaciones de satisfacción con el tratamiento y adherencia a la práctica. Las medidas para evaluar sueño incluyeron calidad de sueño, duración objetiva y subjetiva, y el grado de molestia ocasionada por los problemas de sueño. Los resultados mostraron altos niveles de satisfacción con el tratamiento, adherencia y una mejora en el sueño clínicamente relevante (≤ .5 DE) para todos los grupos. La calidad de sueño mejoró significativamente, p < .05, η2 = .70, sin diferencias significativas entre grupos y con resultados similares para las otras medidas de sueño en todas las opciones de tratamiento. El que los resultados entre los grupos en persona y por teléfono hayan sido comparables, sugiere que una “dosis” y estrategia de administración únicas son muy viables y que pueden tener un impacto clínicamente significativo. Este estudio provee evidencia piloto de que una intervención hipnótica innovadora para el sueño (5 contactos telefónicos con práctica en casa) reduce el agobio de los participantes y logra un máximo beneficio del tratamiento.

Omar Sánchez-Armáss Cappello

Autonomous University of San Luis Potosi, Mexico

Introduction

Poor sleep is a frequent symptom and considerable public health issue for menopausal women, with 40 to 64% of perimenopausal and postmenopausal women reporting difficulty sleeping (Kravitz et al., Citation2003; National Institutes of Health, Citation2005), which is significantly more than women in premenopause (Young et al., Citation2003). Women with sleep issues report decreased well-being, lower self-reported health, less work efficiency, and relationship strain. Inadequate sleep is also associated with an increased risk of morbidities such as diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular disease (Dennerstein et al., Citation2007; Joffe et al., Citation2010). On a national level, poor sleep contributes to workplace absenteeism, risk for accidents due to daytime sleepiness, and increases in healthcare costs attributable to rising emergency room visits for sleep medicine misuse (Mitka, Citation2013). Current treatment options are predominately pharmacological (e.g., hormone therapies, SSRIs, and sedatives), and most have unfavorable risk/benefit ratios that limit their safety and long-term usefulness (Davari-Tanha et al., Citation2016; Dorsey et al., Citation2004; Heinrich & Wolf, Citation2005; Mitka, Citation2013; Writing Group for the Women’s Health Initiative Investigators, Citation2002). There is a pressing need for safe treatments to alleviate poor sleep in women during menopause.

Given the heterogeneity and interrelatedness of menopause symptoms, an ideal treatment could be individualized and potentially ameliorate multiple symptoms. A promising treatment is clinical hypnosis, a mind-body therapy wherein an enhanced internal focus of attention facilitates an increased ability to respond to therapeutic suggestions. Hypnosis has been used to treat symptoms that are relevant to this population (Elkins et al., Citation2013, Citation2008), and due to promising results with the empirically based program of five in-person, therapist-delivered sessions in these previous studies, clinical hypnosis is recommended by the North American Menopause Society (NAMS) as a first line nonhormonal treatment for menopausal vasomotor symptoms (J. Carpenter et al., Citation2015).

Small trials and case studies of hypnosis for sleep improvement suggest that hypnosis can improve sleep in various populations (Becker, Citation1993; Chamine et al., Citation2018; Farrell-Carnahan et al., Citation2010; Stanton, Citation1989). A single hypnosis administration can alter sleep architecture during naps, increasing time spent in slow wave sleep (SWS) in both young and senior women with no disordered sleep (Cordi et al., Citation2015, Citation2014). Additionally, sleep quality improves following a five-session, in-person hypnosis intervention for hot flashes in postmenopause (Elkins et al., Citation2013). Though the evidence shows that hypnosis can be of great benefit, empirical research is limited on the effects of a hypnosis intervention tailored to improve sleep in individuals with sleep complaints. Furthermore, there is a gap in knowledge of the optimal dose and delivery method for a hypnosis program for poor sleep in any population, including women in menopause (Graci & Hardie, Citation2007).

The purpose of this study was to examine feasibility and acceptability of different delivery methods (i.e., in-person therapist or phone contact) and number of sessions (three or five sessions) for peri- and postmenopausal women experiencing sleep problems, to inform the development of a larger-scale study of efficacy. Primary outcomes included: objective sleep duration, self-reported sleep quality, bothersomeness of symptoms, and the percent of participants who report meaningful improvement in sleep.

Methods

Study Design

This was a single-blind, 2 × 2 randomized, factorial trial comparing two different “doses” (three vs. five) of contact with research therapists and two delivery methods (in-person hypnosis sessions delivered by a therapist or contact via telephone only), with at home practice with audio recordings for all groups. Following informed consent, screening, and baseline data collection, participants were individually randomized to one of the four treatment groups. Outcomes were assessed at baseline prior to beginning the intervention and weeks 4, 6, and 8 following the start of the intervention. The study was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov before data collection started (registry number: NCT02187419).

Participant Selection

Participants were recruited through physician referrals, advertisements, post cards, and press releases from the community of Waco, Texas, and the surrounding areas. Study visits were carried out in the Mind-Body Medicine Research Laboratory (MBMRL) at Baylor University (Waco, TX, US).

Inclusion Criteria

Individuals met the following inclusion criteria in order to participate in this study: Female, aged 40 to 65; postmenopausal (defined as 12 months of amenorrhea) or in the late perimenopausal transition (defined as two or more missed menstrual cycles with an interval of amenorrhea 60 days or more in the past 12 months); self-reported sleep duration of 6 hours or less per day/night for 5 or more nights per week as determined by self-report at screening and confirmed via a 7-day sleep diary.

Exclusion Criteria

Individuals who met any of the following exclusion criteria at screening or baseline were excluded from study participation: sleep apnea or restless legs syndrome; currently using hypnosis for any condition; inability to speak or understand English; depression as defined by the 8-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-8); severe or unstable medical or psychiatric illness; use of hormone therapy or hormonal contraceptives in the past 2 months before enrollment or during the duration of the study; use of any prescription or over-the-counter therapy for sleep in the past 2 weeks before enrollment

Screening was undertaken in a two-step process. In the first step, all eligibility criteria were checked, and after informed consenting eligible participants underwent a screening week, during which poor sleep (6 hours or less per day/night for 5 or more nights per week) was verified using a sleep diary. To prevent bias, screening was conducted by a person not involved in intervention delivery and from whom the allocation sequence was concealed.

Group Allocation and Randomization

After eligibility was determined, a second informed consent was given to participate in the study, followed by group allocation. The allocation sequence was predetermined using computerized randomization. Blocked randomization was used with fixed block sizes of 4 (1:1:1:1 randomization), stratified by the presence of hot flashes (determined as 7 hot flashes per day or 50 hot flashes per week during the screening or baseline week), to achieve roughly equal group sizes. Group names printed on cards were stored in nontransparent sealed, sequentially numbered envelopes and kept in a locked safe until the allocation of the participant. These envelopes were only accessible to authorized study personnel. At the point of group allocation at the end of the baseline data collection appointment, the seal on the envelope was broken by an authorized staff member not involved in either eligibility screening or intervention delivery.

Intervention

Audio Recordings

All intervention arms were instructed on the 5-week, at-home treatment program, which included audio-recorded Hypnotic Relaxation Therapy for sleep. The hypnotic inductions were based on Hypnotic Relaxation Therapy (Elkins, Citation2014) and included mental imagery for coolness and comfort and suggestions for deeper sleep (a sample transcript is included in the Appendix to this article). The theme of the hypnosis induction and mental imagery is different for each treatment week:

Week 1: Hypnotic Relaxation for Sleep: Lake Imagery

Week 2: Hypnotic Relaxation for Sleep: Mountain Imagery

Week 3: Individualizing Hypnotic Relaxation Therapy for Deep Sleep

Week 4: Hypnotic Relaxation for Sleep: Deeper Sleep

Week 5: Learning Self-Hypnosis for Relaxation and Sleep

The same speaker (first author) voiced all recordings. The audio recordings were approximately 20 minutes in duration. Participants in all groups were encouraged to practice at home by listening to the audio recordings at least once per day. At-home practice with the recordings could be done at any time that they were in a safe, quiet environment. Participants were not instructed to listen to the tape at any particular time of day.

Weekly instruction booklets were provided to guide the participants’ in-home practice. In addition to the standard audio recordings and booklets, all participants received contact with a trained research therapist. Standard therapist contact involves discussion of treatment progression, instructions for use of audio materials, and encouragement of home practice. The delivery of each hypnosis intervention group was outlined in detail in session checklists. The therapist-delivered contacts followed the same session checklists as the telephone contacts; the only difference was a “completed hypnotic induction” item to be completed during the in-person, therapist-delivered contacts only. Duration of contacts was approximately 30 minutes. According to group allocation, participants received one of the following four interventions:

Group 1: Standard Audio Recordings for Home Practice, with Five In-Person, Therapist-Delivered Hypnotic Inductions

In addition to home practice with the standard audio recordings, participants met with their therapist for five weekly sessions. During these sessions, a trained therapist guided each participant through a hypnotic induction based on the theme of the treatment for the upcoming week.

Group 2: Standard Audio Recordings for Home Practice, with Three In-Person, Therapist-Delivered Hypnotic Inductions

In addition to home practice with the standard audio recordings, participants met with their therapist for three sessions scheduled every 2 weeks. During these sessions, a trained therapist guided each participant through a hypnotic induction based on the theme of the treatment for the upcoming week.

Group 3: Standard Audio Recordings Only, with Five Telephone Contacts to Encourage Home Practice

In addition to home practice with the standard audio recordings, participants received a telephone call weekly for 5 weeks. During these calls, the therapist facilitated a session with each participant during which topics related to the past week (i.e., the number of practices; issues, problems, and/or questions about the program) were discussed; the theme of the upcoming week was introduced and reviewed; and encouragement in the daily use of the audio-recorded hypnotic inductions was provided.

Group 4: Standard Audio Recordings Only, with Three Telephone Contacts to Encourage Home Practice

In addition to home practice with the standard audio recordings, participants received a telephone call every 2 weeks for three sessions. During these calls, the therapist facilitated a session with each participant during which topics related to the past 2 weeks (i.e., the number of practices; issues, problems, and/or questions about the program) were discussed; the themes of the upcoming 2 weeks were introduced and reviewed; and encouragement in the daily use of the audio-recorded hypnotic inductions was provided.

Measures

Feasibility Measures

The study was designed to determine feasibility and acceptability of the treatment program. Thus, dropout rate, program and treatment satisfaction, adverse events, and adherence to home practice were monitored as benchmarks.

Dropout rate

Dropout rates and reasons for dropouts were recorded by the study staff throughout the study.

Program rating

At weeks 4, 6, and 8, in order to assess participants’ perceptions of the value of the hypnosis program they receive, they were asked “How do you rate this hypnosis program overall in regard to ease of use?” and “How do you rate this hypnosis program overall in regard to improving your sleep?” Responses were given on a 10-point scale ranging from 1 (poor) to 10 (excellent).

Treatment satisfaction

At week 8, participants were asked to rate their overall level of satisfaction with the intervention on a 10-point scale anchored with 0 (completely dissatisfied) to 10 (completely satisfied).

Adverse events

At each study visit, participants were asked to report any adverse events experienced in the prior week.

Adherence to daily home practice

Participants completed the Hypnotic Relaxation Practice Checklist starting from their Week 2 appointment through Week 8. Adherence was determined based on frequency of self-hypnosis practice.

Sleep Outcome Measures

The primary sleep outcomes of the study were sleep quality, objective sleep duration, subjective sleep duration, and bothersomeness of poor sleep. Mean changes over the course of the study and the percent of participants who report meaningful improvement were analyzed.

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index

Participants were asked to complete the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) during the baseline data collection appointment and at weeks 4, 6, and 8 of the study. The PSQI is a 19-item self-report inventory designed to measure sleep quality. Global scores above 4 are normally considered indicative of poor sleep quality (Buysse et al., Citation1989). Previous studies indicate that PSQI total scores are significantly correlated with measures of sleep onset latency, amount of time spent awake after initial sleep onset, and total sleep time as assessed by sleep diary and wrist actigraphy (Grandner et al., Citation2006); alphas for the PSQI range from .70 to .80 (J. S. Carpenter & Andrykowski, Citation1998). PSQI global scores were used to assess the primary outcome, sleep quality.

Wrist actigraphy

Wrist actigraphy is a widely used and well-validated, objective measure of sleep duration (Jean-Louis et al., Citation1999; Martin & Hakim, Citation2011), and has been used to reliably differentiate the sleeping patterns of men and women (Jean-Louis et al., Citation1999). Participants were asked to wear an actigraph, which is comparable in size and weight to a wristwatch, on their nondominant wrist (Actiwatch 2; Phillips Respironics) for the entirety of the study. A motion detection device located within the actigraph records wrist movement. In this study, actigraphy was used to determine the primary outcome: sleep duration.

Daily sleep diary

The information collected from this form is a self-report of sleep patterns. A daily sleep diary (Carney et al., Citation2012) where participants recorded time awake and time to bed was used to verify initial eligibility and to guide actigraphy scoring. Participants were asked to complete the daily sleep diary upon awakening each morning throughout the study.

Bothersomeness Numerical Rating Scale

Participant perception of meaningful change was also assessed by rating of “bothersomeness.” Participants provided ratings of the degree to which their sleep problems were bothersome using a 0 (not at all) to 10 (extremely) point Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) at Week 6 and Week 8. This rating provided data on the amount of change in bothersomeness that participants experience as important.

Sample Size Calculation

The purpose of this study was not to find significant differences between the treatment arms. Rather, target sample size was powered to ensure significant change in sleep outcomes from baseline to endpoint within each treatment arm could be detected. Required sample size was determined based on a-priori power calculation using data from our preliminary study (Elkins et al., Citation2013). This earlier study indicated that participants reported an average 5–6 sleep duration at baseline and showed a 46.91% increase in self-reported duration after the intervention of five therapist-delivered sessions of hypnosis participants. Therefore, a target sample size of n = 80 (20 per group) was determined to be adequate to detect an effect size of f = .49 with a power of 0.96.

Blinding

Data collectors, staff responsible for data entry, and the study statistician remained blind to group allocation. No study personnel involved in data collection had access to the randomization list. Blinding for the participants and therapists was not possible with this study design, as each randomly assigned participant was aware of how the intervention was delivered and how many sessions they attended, based on scheduling.

Data Analysis

All outcomes were compared at baseline to note whether there were differences at baseline between the four randomized study arms. Outcomes were also submitted to formal statistical analyses (repeated measures ANOVAs) to take within-subjects change into account when determining effect size. However, at this preliminary stage we did not expect to find statistically significant differences, thus, p values are used only as secondary information, when determining effectiveness of intervention arms.

Effect sizes (Cohen’s d, calculated via repeated measures ANOVAs) and 95% confidence intervals were calculated at each of two time points (weeks 6 and 8) for primary sleep outcomes. Thus, three effect sizes and corresponding confidence intervals were calculated comparing the “Standard audio recordings for home practice, with five in-person, therapist delivered hypnotic inductions” study arm to each of the other three study arms. Study arms indicating highest similarity to the maximal intervention of five therapist-delivered sessions were deemed most useful for subsequent study.

In order to determine which, if any, of the treatment arms resulted in clinically meaningful improvement of sleep outcomes, the percent of participants with an improvement of 0.5 standard deviation (SD) or greater from baseline was calculated for each outcome and plotted across treatment and follow-up. The use of percentages allows for ranking of effectiveness. Clinically meaningful improvement is identified as improvement of at least 0.5 SD of the norm based on global sleep quality results from our previous study (Elkins et al., Citation2013).

Results

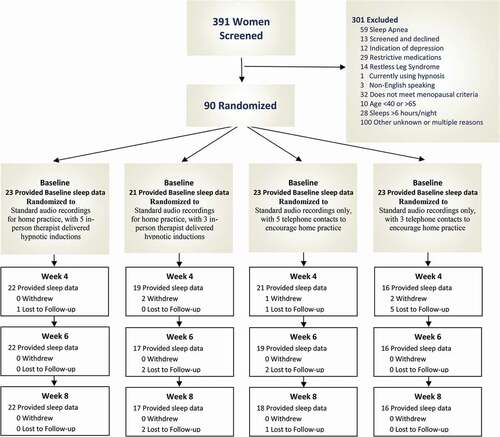

Three hundred and ninety-one postmenopausal or in the menopausal transition stage women were screened for eligibility. Of those, 90 women met the inclusion criteria and were randomized into one of the four study arms (). Groups did not differ significantly in number of dropouts at any time point during the course of the study. In addition, groups did not significantly differ in demographics, as indicated in .

Table 1. Participant Demographics

Program and Treatment Satisfaction

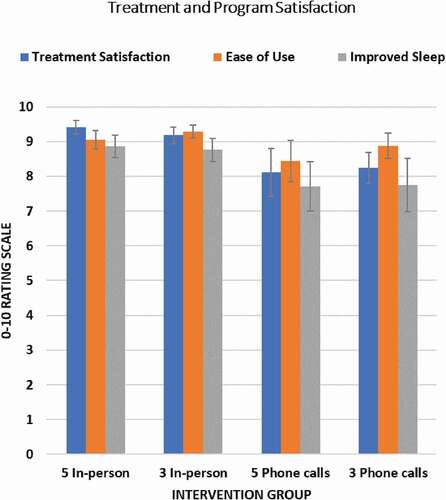

Treatment and program satisfaction were assessed at study completion. Participants were asked to rate their overall level of satisfaction with the treatment and to rate the ease of use of the hypnosis program, respectively. Both treatment and ease of use ratings were high among all groups (see ). Average treatment satisfaction ranged from 8.11 (SD = 2.9) to 9.41 (SD = .91) on a 0-to-10 NRS (0 = highly dissatisfied, 10 = highly satisfied). Average ease of use ratings ranged from 8.44 (SD = 2.5) to 9.29 (SD = .77) on the same NRS. There were no significant differences among groups in regard to treatment satisfaction, F(3, 72) = 2.45, p > .05, η2 = .10, or ease of use ratings, F(3, 72) = .86, p > .05, η2 = .04.

Figure 2. Program Evaluation and Treatment Satisfaction Ratings

Participants were also asked to rate the hypnosis program overall in regard to subjective sleep improvement on the same 0 (highly dissatisfied) to 10 (highly satisfied) NRS. Participants, on average, rated sleep improvements from 7.72 (SD = 3) to 8.86 (SD = 1.5) across all four study arms. There were no significant differences among the four intervention arms, F(3, 72) = 1.3, p > .05, η2 = .05. Program evaluation and treatment satisfaction for both phone-delivered and in-person hypnosis interventions were rated very highly (). Eighty-eight percent of participants receiving self-administered hypnosis rated the program’s ease-of-use 7 or higher. Overall, individuals were about equally satisfied with the phone-delivered intervention as with in-person sessions.

Adverse Events

Adverse events were assessed at each session by participant self-reports. Only four adverse events were likely related to the study. These events included two reports of mild skin irritation from the actigraph watch strap, one concern related to specific hypnotic suggestions (i.e., water and fish), and one report of intense feelings of relaxation. No medical attention was sought for any of these events. There were no other reported adverse events related to the study protocol or interventions.

Adherence to Daily Practice

Participants were asked to record at-home practice of self-hypnosis using the Hypnotic Relaxation Practice Checklist. Adherence to self-administered self-hypnosis was very high. Participants were asked to practice once per day (i.e., seven times per week). On average, participants met or exceeded the adherence criteria. There were no significant differences of total at-home practice between the four groups, F(3, 52) = .24, p = .87; η2 = .014. Means for number of weekly practices ranged from 7.7 (SD = 2.9) at Week 1 to 10.1 (SD = 5.3) during Week 5. At-home hypnosis practice significantly increased over time in all groups, F(5, 260) = 7.31, p < .01, η2 = .12, with an average 9.6 (SD = 4.9) number of practices on the final week, when sessions and phone calls had ended for all groups. Adherence increased across groups demonstrating that personal contact was not needed in order to achieve adherence to self-administered hypnosis.

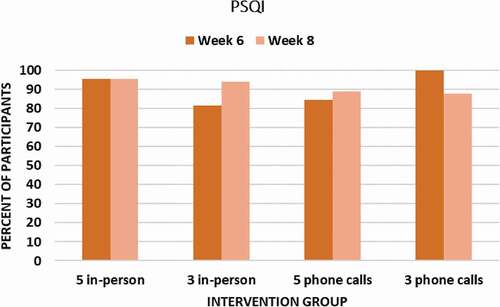

Sleep Quality

The Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) was used to measure improvements in sleep quality. There were no significant between groups differences in sleep quality among the four treatment groups at baseline, p = .076, or other study time points. Sleep quality significantly improved from baseline to end-of-study across all groups, F(3,198) = 148.5, p < .05, η2 = .70. The effect of five phone-delivered sessions on sleep quality was large at Week 6, d = 1.64, and at Week 8 follow-up, d = 1.88, with participants averaging a 1.97 SD improvement in sleep quality. The percent of participants achieving a clinically meaningful (≥ 0.5 SD) improvement in sleep quality (PSQI) from baseline to endpoint ranged from 81.3% to 100% across groups ().

Figure 3. Percent of Participants in Each Group Achieving a Clinically Meaningful (≥ 0.5 SD) Improvement in Sleep Quality (PSQI) at Week 6 Endpoint and Week 8 Follow-Up

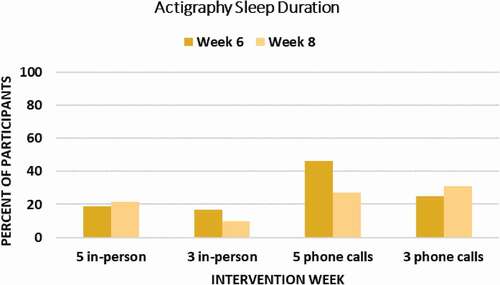

Wrist Actigraphy

There were no significant differences in actigraphy measured sleep duration among the four treatment arms at Week 6 endpoint, p = .77, or at Week 8 follow-up, p = .09. However, participants in both self-administered and therapist-delivered hypnosis groups experienced clinically meaningful improvement with self-administered hypnosis arms showing better sleep duration improvement. At study endpoint, the percent of participants achieving SD of 0.5 or greater improvement in sleep duration ranged from 16.7% (three in-person) to 46.2% (five phone calls; ).

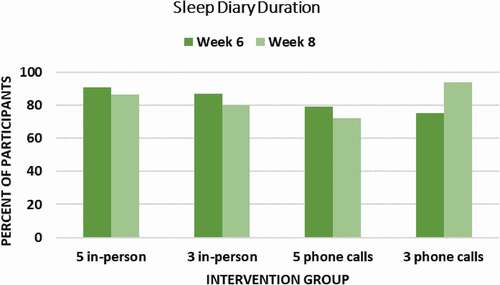

Daily Sleep Diaries

There were no significant between groups differences in sleep diary duration between the four treatment groups prior to intervention, p = .065, or at other study time points. Sleep duration significantly improved from baseline to end-of-study across all groups, F(7,392) = 30.6, p < .001, η2 = .35. The effect of five phone-delivered sessions on sleep quality was d = 1.22 at Week 6, and d = 0.79 at Week 8 follow-up. Participants using self-administered hypnosis via phone-delivered sessions achieved clinically meaningful changes in sleep that are comparable to therapist delivered. The percent of participants achieving a clinically meaningful (≥ 0.5 SD) improvement in sleep duration from baseline to endpoint ranged from 75.0% to 90.9% across groups ().

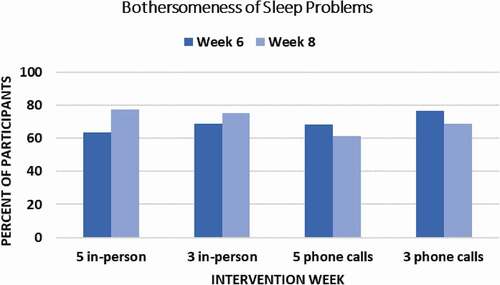

Bothersomeness Numerical Rating Scale

Patient perception of meaningful change was further assessed using a 0 to 10 scale, with higher scores indicating higher levels of distress regarding sleep. There were no significant between groups differences in ratings of sleep problem bothersomeness at baseline, p = .306. Sleep problem bothersomeness significantly improved from baseline to end-of-study across all groups, F(3,198) = 35.11, p < .001, η2 = .35. The effect of five phone-delivered sessions on sleep quality was high at Week 6, d = 1.32, and at Week 8 follow-up, d = 1.07. The percent of participants achieving a clinically meaningful (≥ 0.5 SD) improvement in bothersomeness from baseline to endpoint ranged from 63.6% to 76.5% across groups ().

Discussion

The present study evaluated a manualized 5-week hypnosis intervention for improvement of sleep. Differing ways of delivering the hypnosis intervention (by phone or in-person visits with a therapist) as well as “dose” of three versus five sessions. In addition to feasibility measures, the study used both self-report measures (sleep diaries, sleep quality, rating scales) and objective measures of sleep duration (actigraphy). Both statistically significant results and clinically meaningful change (0.5 SD or greater from baseline; Elkins et al., Citation2013) were evaluated. The results provide strong evidence that the manualized hypnosis intervention is not only feasible but also has a clinically meaningful impact on improvement of sleep duration and quality. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) is a nonpharmacological approach to insomnia (Trauer et al., Citation2015). However, it may be overly burdensome or time consuming for some patients. Therefore, based on the present findings, a hypnosis intervention may be a viable, if not preferable, alternative for some patients.

While all study arms in the current study showed benefit, a five-session, phone-delivered hypnosis intervention may be minimally burdensome (as no in-person visits are needed) and provide improvements in sleep that are comparable or better than in-person delivered sessions when audio recordings for home practice are provided. While the present study was not designed to assess efficacy, the results are very promising for efficacy and indicate much potential for scalability. There are several important aspects of the evidence that should be highlighted.

First, the hypnosis intervention for sleep was relatively brief and well accepted. The intervention compared three versus five visits, and all were rated as highly satisfactory by participants. The average treatment satisfaction ranged from an average of 8.11 (SD = 2.9) to 9.29 (SD = .91) with no significant difference among study arms in regard to treatment satisfaction or program satisfaction. Participants’ self-rated sleep improvements were likewise very positive ranging from 7.72 (SD = 3.0) to 8.86 (SD = 1.5). Program evaluation and treatment satisfaction of phone-delivered hypnosis intervention was rated very highly, and 88% of participants receiving self-administered hypnosis inductions rated the program’s ease-of-use 7 or higher on a 0-to-10-point scale. Individuals were about equally satisfied with phone-delivered and in-person sessions. This brief and highly rated self-administered hypnosis intervention program has the potential to be highly scalable and could be very cost effective in reaching a diverse clinical population.

Second, adherence to daily practice of self-hypnosis was very high. Participants were asked to practice with or without the recordings at least once per day, and on average most participants met, and often exceeded, the minimum practice requirements. There were no significant differences among the groups in adherence and the phone-delivered hypnosis groups resulted in excellent adherence, during many weeks exceeding the therapist-delivered programs. The study also was one of the first hypnosis for sleep trials to assess adverse events. Adverse events were assessed at each session and were very minimal. Only one concern was related to some specific hypnosis suggestions (1 participant did not like the imagery of a fish under water) and one concern was related to feeling so relaxed that alerting was slower than expected. No medical attention was sought for these events, and they were both rated as mild. The hypnosis intervention for sleep appears to be safe and any adverse reactions rated as very mild.

Third, sleep quality is of most importance to many patients and can reflect both sleep duration as well as perceived ease and depth of sleep. Sleep quality was assessed with the Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). Sleep quality significantly improved from baseline to end of study for all treatment arms. The five phone-delivered sessions had a large effect on sleep quality at end of treatment (d = 1.64) and at follow-up (d = 1.88). This effect provides evidence to support a large two-arm clinical trial comparing five phone-delivered sessions to a control condition. The results of the present study suggest a sample size of 112 per arm to compare the intervention to a placebo control with an expected placebo effect of 15 to 20% would likely be sufficient to detect this effect in a future randomized clinical trial.

Fourth, to our knowledge this is the first empirical evaluation of a manualized hypnosis intervention for sleep disturbances that used wrist actigraphy as a primary outcome measure. The present study establishes the feasibility of actigraphy in future trials of hypnosis intervention for sleep. At study endpoint, the percent of participants achieving 0.5 SD or greater improvement in sleep duration ranged from 16.7% (three in-person) to 46.2% (five phone calls). Interestingly, a higher percentage of participants reported clinically meaningful improvement in sleep duration with the sleep diaries than with actigraphy. For the current study, this variance may be due to a higher amount of missing actigraphy data than diary data (e.g., participants removed the actigraphy watches during the day, sometimes forgetting to put them back on before sleeping). It could also be the case that the hypnosis intervention had a larger effect on participants’ subjective experience than on actigraphy-measured sleep duration. As this was primarily a feasibility study, further research would be needed to assess the comparative effects in the different types of measures. While the sample size was small, the findings provide further support for the five phone calls with self-administered hypnosis as 46% of participants in that arm of the study achieved clinically meaningful improvement in sleep duration at the end of intervention (Week 6 of the study). Future studies should include measures of both the objective and subjective changes in sleep duration.

Sleep diaries provide essential information regarding sleep duration and have the advantage of ease of use and reporting. Clinically meaningful improvements in sleep duration were also shown in participants’ daily sleep diaries. Seventy-two percent of participants in all four groups achieved clinically meaningful improvements in sleep duration at Week 6 that were also maintained at Week 8. The difference between phone call sessions versus in-person sessions was negligible, indicating phone or telehealth delivery of the hypnosis intervention may be an effective alternative intervention to other psychological or pharmacological therapies for sleep disturbances.

Lastly, bothersomeness of sleep problems was also investigated. Bothersomness is an important indicator of perceived benefit. It indicates the degree to which symptoms are difficult to deal with or interfere with quality of life. Patient perceptions of bothersomeness of sleep problems was assessed using a 0-to-10 numerical rating. Clinically meaningful improvements were found in 50 to 77% of participants. There was no significant difference among the four treatment groups.

The role of the telephone contacts was both administrative (e.g., to ask participants about adverse events, any new medication use, etc.) and related to participants’ practice and symptoms within the past week (e.g., encouragement for continued daily practice, questions about the program, what they liked or did not like about the imagery in the past week’s audio, etc.). Therefore, it is likely that telehealth/phone contacts played a role in reminding participants to continue practicing with the audio or in providing time for participants to monitor their symptoms from the past week and be more mindful of any effects.

It is noteworthy that in the present study the hypnosis intervention utilized standardized transcripts that provided sleep-specific suggestions. These suggestions included focusing attention, relaxation, and mental imagery designed to facilitate deeper sleep. It is likely that sleep-specific suggestions and imagery are very important in achieving clinically meaningful improvements in sleep. Prior research (Cordi et al., Citation2015, Citation2020, Citation2014) has shown that hypnotic suggestions with specific imagery (such as a dolphin swimming deeper into the ocean) resulted in significantly increased slow-wave sleep in older women during a midday nap, while hypnotic inductions without specific imagery (relaxation alone, neutral images) did not lead to deeper sleep (Cordi et al., Citation2020) in hypnotizable individuals. Future research is needed to further expand upon the relationship between specific imagery suggestions, hypnotizability, and slow-wave sleep during hypnotic interventions.

Hypnosis has been defined as “a state of consciousness involving focused attention and reduced peripheral awareness, characterized by an enhanced capacity for response to suggestion” (Elkins et al., Citation2015). While this definition provides clarity of the meaning of hypnosis for research, the mechanisms by which hypnosis intervention improves sleep is not yet known. Mental over-activity (such as rumination) has been thought to contribute to insomnia (Roth, Citation2007). In addition, poorer sleep has been associated with stress and physiological arousal (Hossain & Shapiro, Citation2002; Morin & Benca, Citation2012). Hypnosis interventions that improve sleep may reduce physiological arousal through relaxation and increased slow-wave sleep (Chamine et al., Citation2018). In addition, hypnotic suggestions that include ego strengthening, present-moment awareness, and focus on imagery may reduce worry and rumination and facilitate a sense of positive expectancy for restful sleep. Research is needed to determine the mechanisms by which hypnosis intervention improves both midday naps and nighttime sleep duration and quality.

A limitation of the present study is that hypnotizability was not measured in participants. It is unknown whether hypnotizability is a significant moderator of hypnosis intervention in improving sleep. Some studies have suggested that hypnotizability may be important in the success of hypnotic interventions (Cordi et al., Citation2015, Citation2014; Elkins, Citation2017). However, other studies have suggested that hypnotizability may not be a potent moderator of therapeutic outcomes and that individuals often have symptom improvements, regardless of hypnotizability level (Abramowitz et al., Citation2008; Johnson et al., Citation2016; Smith et al., Citation1989). There are a number of scales for reliable measurement of hypnotizability such as the Elkins Hypnotizability Scale (Elkins, Citation2017), and future research should include this possible influencing variable.

An additional limitation of the present study is that the participants were limited to postmenopausal women. Sleep disturbances are pervasive and experienced by aging men, caregivers, patients with chronic pain and medical conditions, and individuals with anxiety, depressions, and mental health concerns. Future research is needed to determine the feasibility and efficacy of this hypnosis intervention with such diverse populations. Research is needed to determine populations for which hypnosis may be an optimal intervention for improving sleep and if five sessions of phone-delivered hypnosis intervention can achieve clinically meaningful improvement in sleep in other patient populations.

Hypnosis interventions are flexible and can be delivered by a range of health care providers (i.e., physicians, nurses, psychotherapists, counselors, acupuncturists, chiropractors, appropriately trained and credentialed hypnotherapists) and may be combined with other interventions such as sleep hygiene instructions, cognitive-behavioral therapy, mindfulness, or sleep medications. Additionally, as results from this study show, even a minimal intervention consisting of at-home self-hypnosis practice and three to five telephone contacts can lead to meaningful improvements in sleep in women during the postmenopausal stage. Research into hypnosis interventions for sleep difficulties is in its early stage, and the potential of hypnosis interventions to improve sleep in diverse populations as well as the potential synergistic effect of combining hypnosis with other established interventions deserves further evaluation.

Authors’ Note

Portions of this study preliminary findings were presented at the NIH Collaboratory 2018 Research Conference on “Sleep and the Health of Women Conference” – October 16–17, 2018, in Bethesda, Maryland. Conference presentation was published in Journal of Women’s Health, (https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/full/10.1089/jwh.2020.8327)

Acknowledgments

We thank Robin Boineau, M.D., M.A., Medical Officer, Office of Clinical and Regulatory Affairs, National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, for assistance with study compliance and review of protocol revisions.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abramowitz, E. G., Barak, Y., Ben-Avi, I., & Knobler, H. Y. (2008). Hypnotherapy in the treatment of chronic combat-related PTSD patients suffering from insomnia: A randomized, zolpidem-controlled clinical trial. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 56(3), 270–280. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00207140802039672

- Becker, P. M. (1993). Chronic insomnia: Outcome of hypnotherapeutic intervention in six cases. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 36(2), 98–105. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00029157.1993.10403051

- Buysse, D. J., Reynolds, C. F., Monk, T. H., Berman, S. R., & Kupfer, D. J. (1989). The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Research, 28(2), 193–213. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4

- Carney, C. E., Buysse, D. J., Ancoli-Israel, S., Edinger, J. D., Krystal, A. D., Lichstein, K. L., & Morin, C. M. (2012). The consensus sleep diary: Standardizing prospective sleep self-monitoring. Sleep, 35(2), 287–302. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5665/sleep.1642

- Carpenter, J., Gass, M. L., Maki, P. M., Newton, K. M., Pinkerton, J. V., Taylor, M., Utian, W. H., Schnatz, P. F., Kauntiz, A. M., Shapiro, M., Shifren, J. L., Hodis, H. N., Kingsberg, S. A., Liu, J. H., Richard-Davis, G., Sievert, L. L., & Shifren, J. L. (2015). Nonhormonal management of menopause-associated vasomotor symptoms: 2015 position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause, 22(11), 1155–1174. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/GME.0000000000000546

- Carpenter, J. S., & Andrykowski, M. A. (1998). Psychometric evaluation of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 45(1), 5–13. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3999(97)00298-5

- Chamine, I., Atchley, R., & Oken, B. S. (2018). Hypnosis intervention effects on sleep outcomes: A systematic review. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 14(2), 271–283. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.6952

- Cordi, M. J., Hirsiger, S., Mérillat, S., & Rasch, B. (2015). Improving sleep and cognition by hypnotic suggestion in the elderly. Neuropsychologia, 69, 176–182. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2015.02.001

- Cordi, M. J., Rossier, L., & Rasch, B. (2020). Hypnotic suggestions given before nighttime sleep extend slow-wave sleep as compared to a control text in highly hypnotizable subjects. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 68(1), 105–129. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00207144.2020.1687260

- Cordi, M. J., Schlarb, A. A., & Rasch, B. (2014). Deepening sleep by hypnotic suggestion. Sleep, 37(6), 1143–1152. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5665/sleep.3778

- Davari-Tanha, F., Soleymani-Farsani, M., Asadi, M., Shariat, M., Shirazi, M., & Hadizadeh, H. (2016). Comparison of citalopram and venlafaxine’s role in treating sleep disturbances in menopausal women, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 293(5), 1007–1013. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-015-3900-1

- Dennerstein, L., Lehert, P., Guthrie, J. R., & Burger, H. G. (2007). Modeling women’s health during the menopausal transition: A longitudinal analysis. Menopause, 14(1), 53–62. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/01.gme.0000229574.67376.ba

- Dorsey, C. M., Lee, K. A., & Scharf, M. B. (2004). Effect of zolpidem on sleep in women with perimenopausal and postmenopausal insomnia: A 4-week, randomized, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Clinical Therapeutics, 26(10), 1578–1586. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinthera.2004.10.003

- Elkins, G. (2014). Hypnotic relaxation therapy: Principles and applications. Springer.

- Elkins, G. (2017). Handbook of medical and psychological hypnosis: Foundations, applications, and professional issues. Springer.

- Elkins, G. R., Barabasz, A. F., Council, J. R., & Spiegel, D. (2015). Advancing research and practice: The revised APA Division 30 definition of hypnosis. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 63(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00207144.2014.961870

- Elkins, G. R., Fisher, W. I., Johnson, A. K., Carpenter, J. S., & Keith, T. Z. (2013). Clinical hypnosis in the treatment of post-menopausal hot flashes: A randomized controlled trial. Menopause, 20(3), 291–298. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/GME.0b013e31826ce3ed

- Elkins, G. R., Marcus, J., Stearns, V., Perfect, M., Rajab, M. H., Ruud, C., Palamara, L., & Keith, T. (2008). Randomized trial of a hypnosis intervention for treatment of hot flashes among breast cancer survivors. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 26(31), 5022–5026. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2008.16.6389

- Farrell-Carnahan, L., Ritterband, L. M., Bailey, E. T., Thorndike, F. P., Lord, H. R., & Baum, L. D. (2010). Feasibility and preliminary efficacy of a self-hypnosis intervention available on the web for cancer survivors with insomnia. E-Journal of Applied Psychology, 6(2), 10–23.

- Graci, G. M., & Hardie, J. C. (2007). Evidenced-based hypnotherapy for the management of sleep disorders. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 55(3), 288–302. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00207140701338662

- Grandner, M. A., Kripke, D. F., Yoon, I. Y., & Youngstedt, S. D. (2006). Criterion validity of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: Investigation in a non-clinical sample. Sleep and Biological Rhythms, 4(2), 129–136. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1479-8425.2006.00207.x

- Heinrich, A. B., & Wolf, O. T. (2005). Investigating the effects of estradiol or estradiol/progesterone treatment on mood, depressive symptoms, menopausal symptoms and subjective sleep quality in older healthy hysterectomized women: A questionnaire study. Neuropsychobiology, 52(1), 17–23. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1159/000086173

- Hossain, J. L., & Shapiro, C. M. (2002). The prevalence, cost implications, and management of sleep disorders: An overview. Sleep and Breathing, 6(2), 085–102. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11325-002-0085-1

- Jean-Louis, G., Mendlowicz, M. V., Von Gizycki, H., Zizi, F., & Nunes, J. (1999). Assessment of physical activity and sleep by actigraphy: Examination of gender differences. Journal of Women’s Health & Gender-Based Medicine, 8(8), 1113–1117. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.1.1999

- Joffe, H., Massler, A., & Sharkey, K. M. (2010). Evaluation and management of sleep disturbance during the menopause transition. Seminars in Reproductive Medicine, 28(5), 404–421. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0030-1262900

- Johnson, A. J., Marcus, J., Hickman, K., Barton, D., & Elkins, G. (2016). Anxiety reduction among breast-cancer survivors receiving hypnotic relaxation therapy for hot flashes. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 64(4), 377–390. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00207144.2016.1209042

- Kravitz, H. M., Ganz, P. A., Bromberger, J., Powell, L. H., Sutton-Tyrrell, K., & Meyer, P. M. (2003). Sleep difficulty in women at midlife: A community survey of sleep and the menopausal transition. Menopause, 10(1), 19–28. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsmc.2018.04.011

- Martin, J. L., & Hakim, A. D. (2011). Wrist actigraphy. Chest, 139(6), 1514–1527. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.10-1872

- Mitka, M. (2013). Zolpidem-related surge in emergency department visits. Journal of the American Medical Association, 309(21), 2203. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.6289

- Morin, C. M., & Benca, R. (2012). Chronic insomnia. Lancet, 379(9821), 1129–1141. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60750-2

- National Institutes of Health. (2005). National Institutes of Health State-of-the-Science Conference statement: Management of menopause-related symptoms. Annals of Internal Medicine, 142(12), 1003–1013. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-142-12_Part_1-200506210-00117

- Roth, T. (2007). Insomnia: Definition, prevalence, etiology, and consequences. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 3(5), S7–10. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.26929

- Smith, M. S., Womack, W. M., & Chen, A. C. (1989). Hypnotizability does not predict outcome of behavioral treatment in pediatric headache. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 31(4), 237–241. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00029157.1989.10402778

- Stanton, H. E. (1989). Hypnotic relaxation and the reduction of sleep onset insomnia. International Journal of Psychosomatics, 36(1–4), 64–68.

- Trauer, J. M., Qian, M. Y., Doyle, J. S., Rajaratnam, S. M., & Cunnington, D. (2015). Cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic insomnia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Internal Medicine, 163(3), 191–204. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7326/M14-2841

- Writing Group for the Women’s Health Initiative Investigators. (2002). Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: Principal results from the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 288(3), 321–333. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.288.3.321

- Young, T., Rabago, D., Zgierska, A., Austin, D., & Finn, L. (2003). Objective and subjective sleep quality in premenopausal, perimenopausal, and postmenopausal women in the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study. Sleep, 26(6), 667–672. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/26.6.667

Appendix:

Hypnotic Relaxation for Sleep

This audio recording will guide you in hypnotic relaxation for deeper and more restful sleep with mental imagery of being in the mountains. You should not listen to this recording when you are driving a car or engaged in any activity that required your conscious attention. There is nothing you have to do or have to try to do, hypnotic relaxation is a process of “letting go” of any tension and drifting into a state of deep relaxation. Your sleep environment should be quite, cool, and dark. This recording is intended only to teach hypnotic relaxation therapy for your personal use. The use of this recording for any other purpose is strictly prohibited. This recording is not a substitute for medical or psychological consultation for any condition. You can practice with this recording as often as you like; however, daily use with sleep is recommended. You should not use this recording if you are involved in any activity where vigilance and alertness to one’s surroundings is important, such as when driving a car. You should only practice with this recording when you are in a safe place where you can fully focus your attention on the recording and relax. You may lie down if you prefer, or you may sit in a comfortable chair or recliner with good support for your head, neck, and shoulders.

You can begin the process of hypnotic relaxation now. Begin by focusing your attention on a spot on the wall. As you concentrate, begin to feel more relaxed. Concentrate intensely so that other things begin to fade into the background.

Good. Now, just take a deep breath of air, hold it for just a moment. Now, as you breathe out, let all of the tension out. As this occurs, allowing your eyelids to close and noticing more and more a relaxed and heavy feeling. Good. Now, take another deep breath of air, hold it for a moment, and as you release the air and breathe out, going into a very deep state of relaxation. Each time you breathe out, thinking the word “relax” silently to yourself. Let the mind and the body work together to achieve a deep state of comfort. Comfort and relaxation. And with each breath, let all of the tension go, drift deeply relaxed. Every muscle and every fiber of your body becoming so deeply relaxed.

Now, going on further. Noticing a wave of relaxation. A wave of relaxation that can begin at the top of your head and spread across your forehead, your face, your neck, and shoulders. As you concentrate as you allow this to occur, every muscle and every fiber of your body can become more and more completely relaxed. As you notice this wave of relaxation more and more, just noticing a feeling, a feeling of letting go. Letting go and drifting deeper and deeper relaxed. And while you can hear my voice as your mind goes deeper and deeper relaxed, so you will be able to notice feelings of comfort, cool feeling. Going so deeply relaxed that you just drift further and further. Your eyelids can feel heavy. Your arms can relax, and this can be a good feeling. As you notice a calmness, a feeling of being at peace as your muscles relax. This is a good feeling that allows you to relax and drift even deeper into a hypnotic state, deep hypnotic relaxation. Now, as you become and remain more relaxed finding these feelings of comfort and with it, a feeling of being safe and secure, a peaceful feeling, calm and secure. Feeling so calm that nothing bothers or interferes with this feeling of comfort.

Changes in sensation naturally occur within such a deeply relaxed state. From time to time, you may notice a floating feeling, drifting and floating, as if you were floating on a cloud, more and more relaxed. As you hear my voice count the numbers from 10 to 1, with each number, finding yourself drifting into an even deeper level of hypnotic relaxation. Now, as you can hear my voice, with a part of your mind, with another part of your mind, drifting deeper relaxed.

Drifting to a place where you do feel safe and secure, a place within your own experience where you become so deeply relaxed that you are able to respond to each suggestion just as you would like to, feeling everything you need to feel and experience as you allow that wave of relaxation to become even more complete. Spreading from the top of your head all the way to your feet. Perhaps at times drifting into sleep … good deep sleep … your sleep will be deeper and sounder … restful … and satisfying … good sleep … deep sleep … as you let go … more and more … letting go …

Ten. Deeper and deeper relaxed. Letting all the tension go, from your forehead, your face, you neck and shoulders. All tension begins to drift away and for this time, nothing bothers nothing disturbs this calm feeling. A feeling of being safe and calm and letting go of all tension, letting go of all stress, drifting to deeply relaxed.

Nine. Even deeper relaxed now. Your neck can go limp your jaw can go slack as all the tension drifts away.

Eight. Drifting into an even deeper states of hypnotic relaxation now so that you can notice images and feelings of coolness and calmness. You may notice colors associated with coolness and calmness, just noticing and observing. There are, of course, sounds of relaxation that you could remember. Sounds like the rustle of a cool breeze that drifts through trees, or the sound of water. A part of your mind can remember the sounds of water as it trickles down over a fountain, or the cool water in a little brook or a creek. There may be memories of music that are soft and relaxing. And certainly you could experience a deeper sense of relaxation by allowing that wave of relaxation now to spread into your arms, your shoulders. Arms become so deeply relaxed that they become limp and heavy. All the tension drifts away, draining out through your arms. Down into the hands, all the tension flowing out through the fingertips, so that all that remains is the heaviness, the feeling of letting go, the relaxation, the coolness and the calmness.

Seven. Your upper back and you lower back can become relaxed and calm, filled with comfort. Perhaps, so comfortable and relaxed that from time to time, you just don’t notice your fingers and arms, just the comfort, cool relaxed comfort. All that matters now is the comfort that becomes more and more complete with every breath of air. Calm and comfortable.

Six. Deeper and deeper relaxed, halfway there. Twice as relaxed. All of the tension can drift away. You’re finding a feeling of peace, more peace within yourself. More and more every day. No matter what is going on around you, a feeling of calmness and peace within you. And as you drift into a deeper hypnotic relaxed state, more and more noticing coolness and comfort.

Five, deeper and even more calm. Back and chest, back and stomach, relax. Letting all the tension go, and going deeper and deeper within yourself to find even more comfort.

Four, arms, legs, and feet become so deeply relaxed, as that wave of relaxation spreads down to your legs and to your feet. A wave a relaxation. The legs and the feet may feel heavy, cool and relaxed feeling, going into an even deeper hypnotic state. The deeper the relaxation, the better the response. And perhaps you can notice how relaxed and heavy your arms and legs have become. So pleasant, that you just allow the relaxation to become more and more complete. And with this comes a feeling of control and comfort. Drift and float, deeper and deeper relaxed.

Three. Deeper and more calm and at ease.

Two. Almost there. Deeply relaxed, nothing bothers, nothing concerns within this deep state of hypnotic relaxation.

One. All the way there. Deeply, comfortably relaxed.

And as you are there now, in a moment, I will suggest images that allow you to experience even more comfort and control. Now, seeing that you are in the mountains. A beautiful place in the mountains. It is cool here. In fact, notice that there is snow all around. The air is very cool, and it is pleasant to notice the white now on the trees and on the ground. You are in the mountains in a beautiful place where you can see the snow and the trees and you might want to take a deep breath of the crisp, cool air. And now, feeling cool waves of comfort flowing over you and through you like a cool breeze of crisp, cool air. It’s the kind of day when the coolness and the cold snow feels very good. This is a very beautiful place.

There is a path before you and as you go down that mountain path … with each step drifting deeper and deeper … .there is a little stream in the mountains … cool … fresh water … it is a little creek … it flows down the mountain … starts high up in the rocks … a little stream in the mountains … and it drifts and flows down … over the rocks and stones … drifts down the mountain … .down … down … down … and you may have come to a place where you can see this little stream … .in the mountains … and as it flows down the mountain … effortlessly … so you will drift … effortlessly … into deep sleep … .sleep will be deeper … .sounder … restful … very good …

Now it is possible to enter an even deeper state of hypnotic relaxation deeper and deeper relaxed. Now, letting all the tension go. And as you do, beginning to enter an even deeper level of hypnotic relaxation. As this occurs, you may notice further changes in sensations. A floating sensation, perhaps less aware of any tensions, just floating in space. Your body floating in a feeling of comfort and your mind is so aware of being in that pleasant place where you find a sense of well-being. Just a kind of detached feeling floating within feelings of comfort. Drifting and floating, more and more. As your body floats, find even more comfort.

And as this occurs, it is so natural that your mind blocks from conscious awareness any excessive discomfort. You may feel a kind of detached, feeling of coolness, feeling more and more relaxed. Drifting and floating, feelings of calmness and comfort, more and more. And as you become more comfortable, so you will find a sense of being more relaxed.

With the practice of hypnotic relaxation, you will find more and more that you are able to sleep very well. Your feelings of well-being will improve, and your quality of life will improve. You will not be bothered by any excessive anxiety and any hot flashes will become less and less. Less and less frequent, less and less severe. As time passes, you will be less bothered by hot flashes; you will feel more calm and relaxed and comfortable every day. Each time you experience hypnotic relaxation you will be able to enter a very deep state of relaxation, and within this relaxed state, you will find good … deep … sleep.

Now in a few moments, I will give you suggestions that you may drift deeper into sleep … and when it is best for you … you will be able to return to conscious alertness when you wish … so now as I count the numbers from four to one. You may become more alert … or perhaps, you will just drift deeper relaxed, whatever is best for you,

Four … three … two … and one.