?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

We investigated whether adding hypnosis to CBT (CBTH) improved treatment outcomes for MDD with a two-armed, parallel-treated, randomized-controlled trial using anonymous self-report and clinician-blinded assessments. Expectancy, credibility, and attitude to hypnosis were also examined. Participants (n = 66) were randomly allocated to 10-weekly sessions of group-based CBT or CBTH. LMM analyses of ITT and Completer data at post-treatment, six-month and 12-month follow-up showed that both treatments were probably efficacious but we did not find significant differences between them. Analyses of remission and response to treatment data revealed that the CBTH Completer group significantly outperformed CBT at 12-month follow-up (p = .011). CBTH also displayed significantly higher associations between credibility, expectancy and mood outcomes up to 12-month follow-up (all p < .05 or better), while attitude to hypnosis showed one significant association (r = -0.57, p < .05). These results suggest that hypnosis shows promise as an adjunct in the treatment of MDD but a larger sample size is required to fully test its merits.

Nicolino Ramondo, Carmela F. Pestell, Susan Byrne, und Gilles Gignac

Zusammenfassung: In einer zweiarmigen, parallel behandelten, randomisiert-kontrollierten Studie mit anonymen Selbstauskünften und klinisch verblindeten Beurteilungen wurde untersucht, ob die Hinzunahme von Hypnose zur CBT (CBTH) die Behandlungsergebnisse bei MDD verbessert. Untersucht wurden auch die Erwartungshaltung, die Glaubwürdigkeit und die Einstellung zur Hypnose. Die Teilnehmer (n = 66) wurden nach dem Zufallsprinzip 10-wöchigen Sitzungen einer gruppenbasierten CBT oder CBTH zugeteilt. LMM-Analysen der ITT- und Completer-Daten nach der Behandlung sowie nach sechs und 12 Monaten zeigten, dass beide Behandlungen wahrscheinlich wirksam waren, aber wir konnten keine signifikanten Unterschiede zwischen ihnen feststellen. Die Analyse der Daten zur Remission und zum Ansprechen auf die Behandlung ergab, dass die CBTH-Completer-Gruppe bei der 12-monatigen Nachbeobachtung signifikant besser abschnitt als die CBT-Gruppe (p = .011). CBTH zeigte auch signifikant höhere Assoziationen zwischen Glaubwürdigkeit, Erwartungshaltung und Stimmungsergebnissen bis zum 12-Monats-Follow-up (alle p < .05 oder besser), während die Einstellung zur Hypnose eine signifikante Assoziation zeigte (r = -0,57, p < .05). Diese Ergebnisse deuten darauf hin, dass Hypnose ein vielversprechender Zusatz bei der Behandlung von MDD ist, dass aber eine größere Stichprobe erforderlich ist, um ihre Vorzüge vollständig zu testen.

Nicolino Ramondo, Carmela F. Pestell, Susan Byrne, et Gilles Gignac

Résumé: Nous avons cherché à savoir si l’ajout de l’hypnose à la TCC (CBTH) améliorait les résultats du traitement du trouble dépressif majeur dans le cadre d’un essai contrôlé randomisé à deux bras, traité en parallèle, utilisant des évaluations anonymes par auto-évaluation et des évaluations à l’insu du clinicien. Les attentes, la crédibilité et l’attitude à l’égard de l’hypnose ont également été examinées. Les participants (n = 66) ont été répartis de manière aléatoire entre des sessions de 10 semaines de TCC en groupe ou de CBTH. Les analyses LMM des données ITT et Completer après traitement, six mois et 12 mois de suivi ont montré que les deux traitements étaient probablement efficaces, mais nous n’avons pas trouvé de différences significatives entre eux. Les analyses des données relatives à la rémission et à la réponse au traitement ont révélé que le groupe CBTH Completer était significativement plus performant que le groupe CBT lors du suivi à 12 mois (p = 0,011). CBTH a également montré des associations significativement plus élevées entre la crédibilité, l’attente et les résultats de l’humeur jusqu’au suivi de 12 mois (tous p < .05 ou mieux), tandis que l’attitude envers l’hypnose a montré une association significative (r = -0.57, p < .05). Ces résultats suggèrent que l’hypnose est prometteuse en tant qu’adjuvant dans le traitement du TDM, mais un échantillon plus important est nécessaire pour tester pleinement ses mérites.

Nicolino Ramondo, Carmela F. Pestell, Susan Byrne, y Gilles Gignac

Resumen: Investigamos si añadir hipnosis a la TCC (CBTH) mejoraba los resultados del tratamiento para el TDM con un ensayo controlado aleatorio de dos brazos, tratado en paralelo, utilizando autoinformes anónimos y evaluaciones clínico-ciegas. También se examinaron las expectativas, la credibilidad y la actitud hacia la hipnosis. Los participantes (n = 66) fueron asignados aleatoriamente a sesiones de 10 semanas de TCC en grupo o TCCB. Los análisis LMM de los datos ITT y Completer en el seguimiento postratamiento, a los seis meses y a los 12 meses mostraron que ambos tratamientos eran probablemente eficaces, pero no se encontraron diferencias significativas entre ellos. Los análisis de los datos de remisión y respuesta al tratamiento revelaron que el grupo CBTH Completer superó significativamente a la TCC en el seguimiento a 12 meses (p = 0,011). La CBTH también mostró asociaciones significativamente más altas entre los resultados de credibilidad, expectativa y estado de ánimo hasta el seguimiento de 12 meses (todos p < .05 o mejor), mientras que la actitud hacia la hipnosis mostró una asociación significativa (r = -0.57, p < .05). Estos resultados sugieren que la hipnosis es prometedora como complemento en el tratamiento del MDD, pero se requiere una muestra de mayor tamaño para probar plenamente sus méritos.

Translation acknowledgments: The Spanish, French, and German translations were conducted using DeepL Translator (www.deepl.com/translator).

Introduction

The disease burden of major depressive disorder (MDD) is at an unprecedented level with the World Health Organization not only reporting it to be the leading cause of illness and disability worldwide, but also that its occurrence is estimated to have increased a further 25% during the COVID-19 pandemic (World Health Organization [WHO], Citation2022). Hypnosis, which has been around for millennia (Hammond, Citation2013), is a promising approach that has gradually gained acceptance amongst clinicians interested in the treatment of MDD (e.g., Alladin, Citation2005; Chapman, Citation2014; Lynn & Kirsch, Citation2006; Yapko, Citation1992), though it has not been extensively researched.

Background and Theory

Clinical hypnosis has been used in two distinct ways to treat MDD – either as a standalone treatment, as in hypnotherapy (e.g., see Fuhr et al., Citation2021), or as an adjunctive technique combined with another therapy, such as psychodynamic or cognitive behavior therapy (CBT). It is the latter use of hypnosis as an adjunctive technique that offers the most potential to improve treatment outcomes, and at little additional cost (Schoenberger, Citation2000).

Many theories have attempted to explain how hypnosis achieves its therapeutic effects. After reviewing the evidence, Jensen et al. (Citation2015) encouraged a renewed focus on biopsychosocial models, arguing that biological, psychological, and social factors are all associated with hypnotic responding. One theory that spans across psychological and social factors is Kirsch’s (Citation1997) response expectancy theory which is based on the premise that a person will act according to preexisting expectations of what a behavior will achieve and the value they place on that outcome. Expectancy is a psychological mechanism that operates across diverse situations and has profound implications not only for medical and psychotherapy treatments generally, but also for hypnosis and depression specifically (Kirsch & Low, Citation2013; Yapko, Citation2013). The contention that expectancy plays a significant role in treatment outcomes has been supported by research which suggests that it accounts for 25–35% of the variability found in hypnotic responding (Lynn et al., Citation2022).

Clinical Hypnosis as an Adjunctive Treatment

Although hypnosis has been applied extensively to numerous medical and psychological conditions (see Lynn et al., Citation2019), what empirical evidence supports its use as an adjunctive treatment for MDD? The small literature is comprised of case reports and clinical trials. Case reports (e.g., Matheson, Citation1979; Terman, Citation1980) have detailed the successful use of adjunctive hypnosis combined with behavioral and cognitive approaches to treat depressed clients. And while a handful of clinical studies exist, no meta-analysis focused exclusively on the use of adjunctive hypnosis has been published. Indirect meta-analytic evidence comes from Milling et al. (Citation2019) who located 10 studies that compared hypnosis (a combined sample of standalone and adjunctive hypnosis) with various control groups. Not all studies required a formal diagnosis of MDD and not all were randomized clinical trials (RCTs). These authors found a mean effect size of g = 0.71 (p ≤ .001) in favor of the combined hypnosis treatments at post, and g = 0.52 (p ≤ .01) at the longest follow-up. They concluded that hypnosis for depressed mood achieved comparable results to other psychotherapies for MDD.

Further indirect meta-analytic evidence comes from Ramondo et al. (Citation2021), who examined the use of CBT with adjunctive hypnosis (CBTH) to treat various disorders. These authors found a significant effect size advantage to CBTH over CBT of d = 0.25 (p < .001) across 39 post-treatment RCTs and d = 0.41 (p < .003) for 16 higher quality RCTs. At follow-up, there was, again, a significant effect size advantage to CBTH of d = 0.54 (p < .001) across 18 RCTs, and d = 0.59 (p < .002) for 10 higher quality RCTs. When subgroup meta-analyses were performed on post-treatment data, CBTH was significantly better than CBT for pain management (d = 0.50, p < .015) and depressed mood (d = 0.41, p < .003), while at follow-up, it was significantly better in the treatment of obesity (d = 0.51, p < .004). The follow-up obesity result is noteworthy as it was achieved following a non-significant result at post-treatment (d = 0.09, p < .294). Although the subgroup analysis for depressed mood suggests that CBTH improved standalone CBT treatment, it was based on a small sample (k = 4) that included three unpublished dissertations and only one of the studies (Alladin & Alibhai, Citation2007) formally assessed participants for MDD. As this is the only published RCT comparing CBTH with CBT in the treatment of MDD that we could find, we review that investigation in some detail next.

In 2007, Alladin and Alibhai randomly assigned 98 chronically depressed, medicated, and moderate to high hypnotically susceptible outpatients to either CBT or Cognitive Hypnotherapy (i.e., CBTH). They all received 16-weeks of cognitive therapy for depression. In addition, the CBTH group received some hypnosis in the first session, as well as a take-home hypnosis recording containing components such as relaxation, positive mind frame and ego-strengthening. Three outcome measures were used to assess mood (Beck Depression Inventory – BDI II), anxiety (Beck Anxiety Inventory – BAI), and hopelessness (Beck Hopelessness Scale – BHS). Treatment was completed by 84 participants (86%) and both groups showed strong improvements across all three outcome measures. Primary analyses using repeated measures ANOVA on data from baseline to 12-month follow-up observed significant week x group interactions on the BDI-II and BAI but only at post-treatment, and on the BHI only at follow-up. Paired sample t-tests found that the CBTH group improved significantly more at post-treatment than the CBT group on all three measures, and on the BHS at 12-month follow-up, though overall effect sizes were small (η = 0.05, 0.19 and 0.07 respectively). Improving hope in this chronically depressed sample was an important treatment advantage for CBTH.

However, methodological issues may have impacted on this study’s internal and external validity, potentially undermining these results. Some of the issues included: (a) missing information (e.g., randomization; who delivered treatment); (b) there were no blinded, clinician-based assessments (i.e., only self-report used); (c) there were no fidelity assessments; (d) there was no control for the use of hypnosis; and (e) there was no Intention to Treat (ITT) analysis. Finally, notwithstanding the above concerns, the generality of the results is, at best, restricted to a sample of hypnotically susceptible and medicated individuals with chronic MDD.

In summary, there are case reports and indirect meta-analytic evidence suggesting that hypnosis as an adjunct, especially combined with CBT, may improve post-treatment outcomes for depressed mood/MDD, however, more rigorous research is required. Furthermore, if the follow-up results for obesity extend to MDD, then CBTH may prove to be a treatment that outperforms CBT over the longer term.

Summary and Aims

We aimed to contribute to the literature by investigating the treatment of MDD using CBTH. We controlled for the use of hypnosis with Progressive Muscle Relaxation (PMR) based on Edmonston’s (Citation1981) analysis in which he found no significant difference between PMR and “neutral” hypnosis (i.e., induction phase). He only found a significant difference between PMR and the “anesis” phase of hypnosis when the main clinical suggestions were delivered, making PMR an ideal adjunct to control both for the use of hypnosis as well as for the use of an adjunct. Additionally, we aimed to contribute by being the first RCT to examine whether outcome expectancy, along with treatment credibility and attitude to hypnosis (Milling, Citation2012), have any bearing on hypnotic-based treatment of MDD. Finally, we delivered our treatments via group therapy as group outcomes for MDD are not only comparable to individual outcomes (Cuijpers et al., Citation2013), but also we were interested in assessing whether adjunctive hypnosis could be delivered effectively through this modality.

Our primary hypothesis was that CBTH would result in treatment advantages over CBT which, if supported, would be reflected in up to four outcome variables (related to mood, anxiety, and quality of life) at the primary endpoint of 6-month post-treatment (T3). Secondary analyses were performed on the differences between the CBTH and CBT treatments at post (T2) and 12-month post-treatment (T4). As we lacked a no-treatment control group, we compared our results with the CBT literature on MDD. Hypothesis testing was complemented by an examination of rates of remission and response to treatment across time. Finally, we anticipated that CBTH would show a greater expectancy effect compared to CBT.

Method

Study Overview

This RCT was based on a 2 × 4 between groups repeated measures design. It provided group-based CBT psychotherapy to participants with upper mild to severe levels of depression over 10-weekly sessions. Mood and suicide risk were monitored. Outcomes were assessed at pre-treatment (T1), at post (T2), at 6-month (T3) and 12-month post-treatment (T4). Three outcome measures were self-report based, and these were completed online anonymously. The fourth was a clinician-rated mood scale for which the post-treatment and follow-up measures were obtained by an independent assessor blinded to treatment allocation and hypotheses. The trial was registered with the ANZCTR (ACTRN 12,620,000,028,909) before recruitment of participants. The Ethics Committee of the University of Western Australia (RA/4/20/5703) approved the study. CONSORT’s reporting guidelines (Butcher et al., Citation2022) were adopted.

Recruitment

Participants were recruited using traditional methods (e.g., study flyers, newspaper, radio) and social media (i.e. Facebook, Instagram). All promotional material emphasized that CBT was the core treatment for MDD but that unspecified treatment adjuncts were also to be trialed. Hypnosis was not mentioned during recruitment. Five recruitment campaignsFootnote1 were conducted between May 2020 and September 2021. Applicants were directed to the study web page and online survey which included questions on study parameters, two items from the Credibility Expectancy Questionnaire (CEQ, Devilly & Borkovec, Citation2000),Footnote2 and a mood questionnaire (Personal Health Questionnaire-9, PHQ-9, Kroenke et al., Citation2001). Those who answered affirmatively to the study parameters and obtained PHQ-9 scores between 10 and 23 were invited to continue. Only at that time were participants given more information about the CBT treatment, as well as the first mention that the two adjuncts were clinical hypnosis and PMR. Those still interested then completed a background questionnaire and signed a Telehealth Consent Form before proceeding to the clinical interview. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, all interviews were conducted via Telehealth and, when consent was given, were audio recorded.

Study parameters required participants to: (i) be 18–65 years; (ii) have an MDD diagnosis; (iii) be excluded because of co-morbidities (i.e., Bi-polar, Psychosis, OCD, Personality Disorder, PTSD, severe Alcohol/drug Use Disorder, Anorexia/Bulimia Nervosa), severe suicidal ideation or they had received psychotherapy in the previous 12 months; (iv) be competent in English; (v) commit to attend 10 weekly group sessions; (vi) be electronically connected (i.e., access to the internet to enable participation, such as the clinical interview and completion of online measures); and, (vii) agree to follow-up assessments.

Randomization and Masking of Assessments

Once eligibility was established, participants were fully informed about the treatment and research components. Following the signing of Participant Consent Forms and the collection of pre-treatment data, participant research numbers were randomly allocated to either a CBT or CBTH group using computer generated allocation stratified by gender and severity of depression (on PHQ-9). Randomization occurred in the two weeks prior to treatment starting and was conducted remotely by the fourth author who was, otherwise, not involved in the clinical trial during the treatment or data collection phase. The results of the randomization were emailed to the first author who notified participants about their allocation.

Assessment and Outcome Measures

The first author conducted all clinical interviews based on the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI, version 7.0.2 for DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association [APA], Citation2013; Sheehan et al., Citation1997) and the MADRS (Montgomery & Åsberg, Citation1979). At these interviews, responses to the Attitude to Hypnosis Questionnaire (AHQ; Spanos et al., Citation1987) were also collected.

The primary outcome measures were self-reported depression (PHQ-9), clinician-rated depression (MADRS), self-reported anxiety (Overall Anxiety Severity and Impairment Scale, OASIS; Norman et al., Citation2011) and self-reported quality of life (Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire – Short Form, QLESQ-SF; Endicott et al., Citation1993) at 6-month post-treatment (T3). The PHQ-9 is a DSM-IV-based questionnaire developed to measure the severity of depression in adults. Responders rate the frequency of depressive symptoms over the previous fortnight using a 0–3 scale. Scores of 5, 10, 15, and 20 represent mild, moderate, moderate severe, and severe depression. The PHQ-9 has sound reliability and validity. Scores ≥ 10 have a sensitivity and specificity of 88% for MDD (Kroenke et al., Citation2001). The MADRS is a 10-item, clinician-rated instrument designed to measure the severity of depressive symptoms in adults using a 0–6 scale. Scores < 7 indicate no depression, 7–19 mild, 20–34 moderate, and 35–60 severe depression. The MADRS is a reliable and valid measure (Montgomery & Åsberg, Citation1979). It can be completed following a clinical interview to assess mood or it can be used as the basis for a structured interview. For the latter use, the Structured Interview Guide for the Montgomery Asberg Rating Scale (SIGMA) was developed and has demonstrated high inter-rater reliability (Williams & Kobak, Citation2008). The OASIS is a 5-item instrument used to assess the frequency and intensity of anxiety, behavioral avoidance, and functional impairment in adults. Responders rate symptoms over the previous week using a 0–4 scale. Scores < 6 correspond to mild or no anxiety, 6–10 moderate anxiety, 11–15 severe and 16–25 indicate extreme anxiety. The OASIS has good reliability and validity. Seventy-eight percent of responders with anxiety disorders were correctly identified using a cutoff score ≥ 8, with a 69% sensitivity and 74% specificity (Norman et al., Citation2011). The QLESQ-SF is a 16-item quality of life checklist derived from a longer 93-item questionnaire. Responders rate their enjoyment and satisfaction in various areas of functioning over the previous week using a 1–5 scale (items 15 and 16 are excluded from the scoring). Percentage scores within 10% of the community mean score are considered to be within the normal range, while a score ≥ 2 SDs represents severe impairment. The short form has sound reliability and validity (Endicott et al., Citation1993).

As we had two pre-treatment PHQ-9 scores that differed significantly from one another, one at screening and one at baseline (p < .05), we averaged the two scores to obtain a composite pre-treatment PHQ-9 score which we considered was a more reliable estimate of pre-treatment mood. Secondary outcomes involved the same measures as above but at post-treatment (T2) and 12-month post-treatment (T4).

Interventions and Procedures

The CBT treatment was based on a multi-component manual developed by the first author after reviewing the MDD literature and other manuals.Footnote3 It included the following components: (i) psychoeducation; (ii) motivation to change; (iii) goal setting; (iv) graded tasks; (v) implementation intentions; (vi) sleep hygiene/management of insomnia; (vii) automaticity; (viii) self-monitoring; (ix) pleasant activity scheduling; (x) values; (xi) functional analysis of avoidance; (Trigger Response Avoidance Patterns, TRAPs); (xii) alternative coping behaviors (TRACs); (xiii) rumination; (xiv) the power of focus; (xv) the cognitive model/attributional styles; (xvi) managing ambiguity; (xvii) cognitive distortions; (xviii) problem solving; (xix) interpersonal problem-solving; and (xx) prevention relapse.Footnote4

After the first introductory session, subsequent sessions followed a standard CBT structure, starting with a session overview, then a check-in on participants’ experiences over the previous week, followed by a review of assigned homework, before new skills were introduced and practised. Teaching components were delivered as a series of PowerPoint presentations which facilitated same treatment delivery (the only content change was references to hypnosis or PMR being used in their respective groups). Participants were given therapy folders to file weekly session handouts and worksheets. The only treatment differences between the two groups occurred in the concluding 15–20 minutes of each session when the adjuncts were implemented. For their adjunct, the CBT group listened to an audio recording of a PMR script (developed by the lead author based on Jacobson, Citation1938). Two types of PMR recordings were used across the 10 sessions, the first without the self-instruction to “relax” on the breath out, while the second recording (used from session 7) included this intervention. CBTH participants listened to 10 different recordings, each recording based on a hypnosis script prepared by the lead author utilizing the key themes of each session. The scripts maintained a similar structure starting with an induction (i.e. neutral hypnosis), followed by the themes for that session and the basis for the suggestions (i.e., anesis), then a 60-second pause to allow for processing, before ending with post-hypnotic suggestions. The scripts used suggestions, metaphors, stories, and techniques, such as age regression and progression (see Yapko, Citation2012). Two examples of hypnosis scripts are provided in Supplementary Materials A.

After the adjuncts were delivered, each session concluded with the assignment of home-based practice focused on tasks related to that session as well as listening to their respective recording as often as possible in the forthcoming week. It was suggested to both groups that the more they listened to their recordings, the more proficient they would become in utilizing self-relaxation or self-hypnosis. Following their session, participants were emailed a link to download either their PMR (if a new one was used) or their hypnosis script recordings.

In total, five CBT and five CBTH groups were conducted matched in size (between 6–8 participants per group across the intakes), and almost equivalent for mood severity and gender. All groups received the same core treatment, the same number of sessions and the same length of sessions (approximately 120 minutes per session). The groups were all held in the same group therapy room at the Robin Winkler Clinic, an outpatient postgraduate psychology training facility at the University of Western Australia. All group sessions were audio recorded.

Therapists and Treatment Fidelity

All 100 treatment sessions were delivered by the lead author together with a different co-facilitator for each group. The lead author, a clinical psychologist with 40 years’ experience, completed his hypnosis training in 2014. The 10 co-facilitators were provisional psychologist trainees in the Doctoral program at UWA with a variety of prior clinical experience. Due to COVID-19 health protocols, if participants could not attend, make-up sessions were available. These sessions were typically briefer (30–60 minutes duration), were often Telehealth based and conducted by a co-facilitator several days after the group session. Also, weekly clinical supervision sessions were held with the lead author, second author and co-facilitators.

Fidelity assessments were conducted on (a) the initial MADRS scores obtained from the clinical interviews and, (b) on adherence to the treatment manual. Ten percent of interviews and treatment sessions were randomly selected and scored by the same research assistant, but not until all of the six- and 12-month post-treatment follow-up MADRS assessments were completed. The SIGMA schedule was the basis for the fidelity assessment of the pre-treatment MADRS,’ while audio recordings and PowerPoint presentations were used to compare the content and session structure for the CBT and CBTH treatment sessions. We found a significant correlation of r = 0.87 (p < .002) between the two MADRS scores for the clinical interviews. Additionally, there was no significant difference between the treatments delivered to each group (t = −1.57, p = .137), suggesting good adherence to the manual and relative equivalence in the treatment delivered. Finally, the research assistant was not unblinded at any assessment.

Data Analyses

A G-Power analysis was performed using 6-month post-treatment Cohen’s d effect sizes we calculated from Alladin and Alibhai (Citation2007), with a two-tailed α of 0.05. Sample size estimates of 28, 25 and 15 were computed based on the respective mood, anxiety, and hopelessness effect sizes we obtained. Allowing for an attrition rate of 19% for RCTs using group CBT (McDermut et al., Citation2001), we estimated that sample sizes of 18–33 per group would be required (or 15–27 after attrition) depending on the measure being investigated.

Statistical analyses of primary (and secondary) continuous outcome data were analyzed with linear mixed-effects modeling (LMM) using SPSS software (Version 28), both from an ITT and Completer basis. Significant group x time interactions were tested using Pairwise Comparisons in SPSS. We defined ITT as any participant who was randomly allocated to a treatment irrespective of whether they attended any sessions. We defined Completer participants as those who attended at least eight sessions, of which a minimum of five were in person (i.e., not make-up sessions). We monitored for additional treatment, and those participants who engaged in treatment beyond the group program, including starting or increasing medication, were left in the ITT analysis but not the Completer analysis due to its potential to confound the results. To test for a potential confound, we compared the ITT results for participants who received additional treatment with the ITT results of those who did not. Notably, half of the participants (5 of 10) who withdrew before completing treatment provided most outcome measures on exit. The records of those who did not, as is the practice with LMM analysis, remained in the analysis on the assumption that missingness was Missing at Random (Garcia & Marder, Citation2017). Meanwhile, missing data from online self-reporting were analyzed using Little’s Missing Completely at Random test. Non-significant chi squared (χ2) statistics were obtained for those tests indicating that the data were missing completely at random. We used the Expectation Minimisation algorithm in SPSS to impute a total of 28 scores for the four main outcome variables across T1, T2, T3, and T4 (see Supplementary Materials B). Missing data for four MADRS’ and one expectancy question could not be imputed. Outlier scores for the main variables, credibility, expectancy and attitude to hypnosis were also identified at each assessment point using the outlier labeling rule and multiplying the inter-quartile range by a factor of 2.2 (Hoaglin & Iglewicz, Citation1987). Outlier scores were then winsorized to the next nearest score (see Supplementary Materials C). Altogether, 6 scores were winsorized. As there is no agreed definition for remission on either the PHQ-9 or MADRS, we followed recent practice (e.g., Coley et al., Citation2020) and defined remitted mood on the PHQ-9 as a score < 5. With remission scores ranging from < 6 to < 12 on the MADRS (Leucht et al., Citation2017), we used a score < 10 representing the median (9) of this range. The literature (e.g., Cuijpers et al., Citation2023) has defined response to treatment as equal to or greater than 50% reduction in symptoms from pre-treatment, and we did likewise for both the PHQ-9 and MADRS. We used χ2 statistics to test for significance in the independent samples’ proportions. Attitude to hypnosis scores along with the two CEQ questions obtained at screening and repeated following session 1, were analyzed using independent t-tests. Correlational matrices on credibility, expectancy, and attitude with PHQ-9 and MADRS scores for all samples were also performed (see Supplementary Materials D). Finally, to enable a comparison with the CBT literature, Hedges’ g effect sizes were computed by subtracting CBT mean scores (i.e., T2-T1, T3-T1, T4-T1), then dividing the result by the pooled standard deviation (Hedges & Olkin, Citation1985). These are provided in Supplementary Materials E, along with a comparison with CBTH effect sizes.

Results

Participant Flow

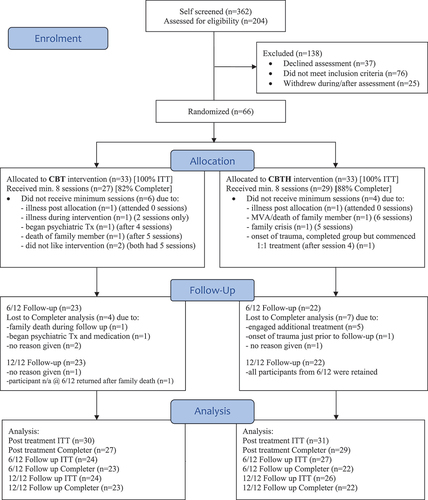

We received 362 partial and completed responses on initial self-screening. Of those, 204 were suitable for interviews and, from this group, 66 participants (76% female) were randomized between June 2020 and September 2021 (see ). All 66 participants were assessed for the primary outcome variables in the ITT sample and, of those, 56 (85%) participants met the minimum requirement for treatment in the Completer group (i.e., 27 CBT and 29 CBTH). At 6-month (T3) and 12-month post-treatment (T4), we assessed 23 (70%) and 22 (67%) CBT and CBTH participants respectively. Reasons for discontinuing treatment are provided in . Both groups provided similar reasons except two CBT participants who stopped due to difficulty engaging with treatment content and/or group process. One person stopped to seek more intensive psychiatric help. Two participants suffered traumas, one in between treatment sessions, and the other just prior to the 6-month follow-up. The first sought individual treatment but wanted to continue with the group, while the latter was wait-listed for individual treatment but commenced medication. As mentioned above, additional treatment seekers were left out of the Completer analysis. To the best of our knowledge, there were no suicide attempts or fatalities during the treatment and follow-up periods.

Participant Characteristics

As can be seen from , social media was the most successful recruitment strategy providing 94% of enrolled participants. Mean age was 45.8 years (SD = 12.2) and Caucasians comprised 83% of the total sample. The largest relationship category was Single (36% never married), while 70% had a tertiary qualification (either undergraduate or postgraduate). Some 95% of participants had experienced more than one episode of depression, 36% were taking at least one anti-depressant, 11% had co-morbid Persistent Depressive Disorder, while 33% had one or more anxiety disorders. With severe alcohol/substance use disorders excluded from the study, 63% of participants reported < 1 standard drink per day and 89% <1 cigarette per day. In terms of physical health, 61% of participants reported at least one inflammatory condition (e.g., asthma, eczema, lupus). Finally, both groups displayed positive attitudes to hypnosis as evidenced by a mean percentile score above 70.

Table 1. Trial Characteristics

Primary Outcomes

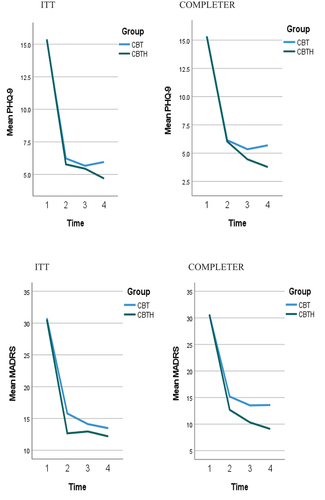

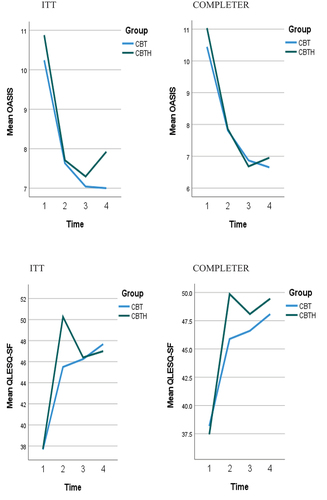

shows the means and standard deviations for the CBT and CBTH groups on the four outcome measures. Lower scores on the PHQ-9, MADRS and OASIS, and a higher score on the QLESQ-SF indicate improvement.

Table 2. Observed Means, Standard Deviations for ITT and Completer at T1, T2, T3, and T4

Based on repeated measures LMM analyses at the primary endpoint (T3), omnibus results for the ITT sample on depression, anxiety, and quality of life showed significant improvement: PHQ-9 F(2, 116.83) = 151.08, p < .001; MADRS F(2, 117.74) = 134.44, p < .001; OASIS F(2, 110.97) = 23.46, p < .001; and QLESQ-SF F(2, 112.69) = 53.76 p < .001. This was also the case for the Completer sample: PHQ-9 F(2, 99.56) = 151.20, p < .001; MADRS F(2, 102.64) = 148.70, p < .001; OASIS F(2, 101.02) = 24.46, p < .001; QLESQ-SF F(2, 96.56) = 54.39, p < .001]. These results suggest a significant effect of time for both samples on all measures, which can be seen in . Additionally, the group by time interaction for the ITT sample was significant, but only on the QLESQ-SF: F(2, 112.69) = 4.54, p = .013; [PHQ-9 F(2, 116.83) = 0.12, p = .888; MADRS F(2, 117.74) = 1.09, p = .34; OASIS F(2, 110.97) = 0.29, p = .747]. In the Completer sample, the group by time interaction was also significant but, again, just on the QLESQ-SF: F(2, 96.56) = 3.13, p < 0.048 [PHQ-9 F(2, 99.56) = 0.12, p = .887; MADRS F(2, 102.64) = 0.90, p = .409; OASIS F(2, 101.02) = 0.24, p = .787]. However, post hoc testing of the group x time interactions at T3 failed to find any significant between group differences on the QLESQ-SF (ITT: SE = 2.08, p = .877; Completer: SE = 2.13, p = .504). Therefore, we were unable able to reject any of the primary null hypotheses.

Figure 2. ITT, Completer Means T1-T4 for PHQ-9 and MADRS

Figure 3. ITT, Completer Means T1-T4 for OASIS and QLESQ-SF

When analyses were performed on ITT data at T3 without the eight participants who accessed additional treatment, the pattern of significance results for time, and for group x time did not change across all four outcome measures. Therefore, the inclusion of those who sought extra treatment into the ITT sample made no difference, at least not on significance testing.

Secondary Outcomes

The means and standard deviations for the CBT and CBTH groups on secondary outcomes are also detailed in . Overall, the pattern of the omnibus results at post-treatment for both samples was similar to the T3 results for both time [ITT: PHQ-9 F(1, 62.19) = 265.70, p < .001; MADRS F(1, 63.15) = 277.34, p < .001; OASIS F(1, 58.67) = 30.59, p < .001; QLESQ-SF F(1, 61.36) = 128.29, p < .001; Completer: PHQ-9 F(1, 54.00) = 229.00, p < .001; MADRS F(1, 54.00) = 257.83, p < .001; OASIS F(1, 54.00) = 27.14, p < .001; QLESQ-SF F(1, 54.00) = 108.26, p < .001] and for the group x time interaction on the QLESQ-SF [ITT F(1, 61.36) = 7.74, p = .007; Completer F(1, 54.00) = 5.93, p = .018]. The remaining interactions were not significant [ITT PHQ-9 F(1, 62.19) = .215, p = .644; MADRS F(1, 63.15) = 2.23, p = .141; OASIS F(1, 58.67) = .40, p = .531; Completer: PHQ-9 F(1, 54.00) = .003, p < .953; MADRS F(1, 54.00) = 1.52, p = .224; OASIS F(1, 54.00) = 0.24, p = .628]. Post hoc testing of the group x time interactions on the QLESQ-SF found significant between group differences favouring both CBTH samples at T2 (ITT: SE = 1.93, p = .009; Completer: SE = 1.98, p = .047), as evident in .

Likewise was the pattern of the omnibus results for secondary outcomes at 12-month follow-up (T4). Improvement over time was maintained at a significant level across all measures for the ITT [PHQ-9 F(3, 160.74) = 125.58, p < .001; MADRS F(3, 158.75) = 91.90, p < .001; OASIS F(3, 150.12) = 17.06, p < .001; QLESQ-SF F(3, 157.88) = 42.22 p < .001] and Completer samples [PHQ-9 F(3, 88.92) = 143.08, p < .001; MADRS F(3, 67.94) = 135.51, p < .001; OASIS F(3, 98.66) = 19.24, p < .001; QLESQ-SF F(3, 75.22) = 51.67 p < .001. The group x time interaction was significant for the ITT sample but, again, only for the QLESQ-SF F(3, 157.88) = 3.84, p = .011 [ITT PHQ-9 F(3, 160.74) = 0.383, p = .765; MADRS F(3, 158.75) = 0.74, p = .530; OASIS F(3, 150.12) = 0.39, p = .759], with the Completer sample just failing to reach significance on the QLESQ-SF F(3, 138.55) = 2.41, p = .070[PHQ-9 F(3, 140.02) = 0.678, p = 0.567; MADRS F(3, 139.98) = 1.15, p = 0.330; OASIS F(3, 137.38) = 0.20, p = .879]. Post hoc testing of the group x time interaction for the ITT sample on the QLESQ-SF did not find a significant between group difference (SE = 2.13, p = .770). These results can also be seen in .

Remission and Response to Treatment

The number of cases that remitted and recovered following treatment and at follow-up are detailed in , along with significance values based on contingency table (χ2) analyses. Due to multiple comparisons, p < .05 values were partially adjusted by dividing by 3 = p < .017. At T2 and T3, the ITT and Completer samples for each treatment group were almost equivalent for remission (PHQ-9 and MADRS), while on response to treatment, the CBTH T3 Completer sample was higher (i.e., 16–19% higher) but failed to reach significance. However, at 12-month follow-up, the CBTH Completer sample achieved significantly better results than CBT on the PHQ-9 for remission (73%) and response to treatment (95%) (both p = .011).

Table 3. Proportion of Remitted and Responded Cases on PHQ-9, MADRS at T2, T3, T4

Participant Credibility, Expectancy, and Attitude

We first analyzed credibility and expectancy scores. At screening, there were no significant differences between the CBT and CBTH on either measure (p > .001). However, following the first session, the CBT credibility score declined while the CBTH score increased, resulting in a significant difference (t = −2.12, p = .038). On expectancy, each group score declined after session 1 and, though the CBTH score declined less, the difference failed to reach significance (t = −1.62, p = .109).

We then conducted a series of correlational matrices on credibility and expectancy with the PHQ-9 and MADRS for all samples (see Supplementary Materials D). These analyses showed that when post-session 1 between-group correlations for credibility and mood were compared, both CBTH samples achieved significantly higher correlations than CBT across T2, T3, and T4 (9 correlations at p < .05). For post-session 1 expectancy, the CBTH ITT sample achieved significantly higher correlations than its CBT counterpart on the PHQ-9 at T2 and T4, and the MADRS at T4 (p < .05or better), while the Completer sample achieved significantly higher correlations on the PHQ-9 and MADRS at T2, and the MADRS at T3 and T4 (p < .05 or better). These data suggest that not only was there a significant association between outcome expectancy and mood improvement in the adjunctive hypnosis group, as one would expect given the literature, but there was also a significant association for treatment credibility.

Finally, we used correlation matrices (see Supplementary Materials D) to investigate the relationship between CBTH, attitude to hypnosis and mood scores. All correlations at T2, T3 and T4 were non-significant, with the exception of the CBTH Completer sample at T4 (MADRS r = −0.57, p < .01). (Note: a negative r denotes improved mood).

Effect Sizes

All effect size calculations can be found in Supplementary Materials E. At the primary endpoint (T3), CBT ITT effect sizes on the PHQ-9 and MADRS were g = 2.40 and g = 2.37 (CBT Completer g = 2.51 and g = 2.39). CBT also achieved similar effect sizes at T2 and T4.

Discussion

The main aim of this RCT was to investigate whether the addition of hypnosis to CBT based psychotherapy resulted in a superior treatment for MDD compared to standalone CBT. LMM omnibus analyses of ITT and Completer samples at the primary endpoint found that differences between the two treatments on self-report and clinician-rated mood measures failed to reach statistical significance and, therefore, we did not reject the null hypotheses. Though both CBTH samples were significantly better than their CBT counterparts on quality of life (QLESQ-SF), the effect occurred only at post-treatment and the between-group difference was not maintained across time. While outcomes related to anxiety were mixed (OASIS), they too were not significant. Similar results were obtained on secondary omnibus LMM analyses of 6-month and 12-month follow-up data.

Our results were achieved with a treatment sample and therapy dose that were similar to other CBT group therapy studies (McDermut et al., Citation2001), and our drop-out rate of 16% compared favorably with the literature (Cooper & Conklin, Citation2015). Interestingly, 61% of our sample reported at least one inflammatory condition, belying the importance of inflammation in the etiology of depression for at least a sub-group of sufferers (Harrison, Citation2018).

As we lacked a no-treatment control group, we cannot definitively state that our treatments were efficacious. However, an extensive meta-analytic literature has consistently shown that CBT is an efficacious treatment for MDD, outperforming various no-treatment control groups by an overall g = 0.79 at post, and g = 0.49 at 10–12-month follow-up (e.g., Cuijpers et al., Citation2023). Even when CBT was compared with the most intense form of active control, there was still an effect size advantage of g = 0.32 (Munder et al., Citation2022). Furthermore, a meta-analysis which focused exclusively on control groups used in MDD research found effect sizes ranging from g = −0.13 for minimal treatment to g = 0.95 for wait-list control (Mohr et al., Citation2014). With our CBT (and CBTH) mood effect sizes all exceeding g = 2.0 across T2, T3 and T4, it is not unreasonable to infer that our treatments were probably efficacious.

Interestingly, the small between-group differences we observed on mood measures at post-treatment generally increased at each follow-up (see ), with CBTH showing continued improvement through to T4 across all four graphs, whereas the CBT samples fluctuated in their performance. The pattern of our results bears some similarity to the meta-analytic results achieved by CBTH in the treatment of obesity, with the main difference being that CBTH for obesity was significantly better than CBT at 12-month follow-up. While neither obesity nor mood treatments were significantly better than CBT at post-treatment, our small sample size (n = 22) may have precluded significant results being achieved at T4.

While it is not possible to make direct comparisons with the Alladin and Alibhai (Citation2007) due to differences in research design, one important observation can be made. Even though this study had a larger sample (n = 98), their results also failed to find significant differences on mood that were maintained at follow-up. This suggests that between-group differences as assessed using an RCT design are small, at best, and that future studies will need to use much larger samples, or a different design, if they are going to detect differences beyond chance.

Our analyses of remission and response to treatment shed further light on how the two treatments performed. At 12-month follow-up, the CBTH Completer sample achieved statistically significant higher levels of remission (73%) and response to treatment (95%) on the PHQ-9 than its CBT counterpart. Several questions arise from these results including, are they spurious or meaningful and, if the latter, how can they be understood?

First, the significant CBTH Completer 12-month follow-up result was achieved after a partial Bonferroni adjustment corrected results that were also favoring CBTH at T2 and T3. This means that the data was trending in the direction of CBTH prior to the 12-month follow-up and, therefore, is less likely to be a one-off, spurious result. Second, the CBTH Completer performance can be understood alongside its ITT result, which also remitted and improved, but to a lesser degree. The ITT sample contained participants (n = 5) who sought additional treatment prior to the T3 assessments. While T3 results for the overall ITT sample did not differ significantly with or without participants who sought additional treatment, that does not necessarily mean that differences between the two groups in terms of their response to CBTH or in terms of how the additional treatment (e.g., medication) may have impacted on them were non-existent. Hence, we would argue that the Completer group was a purer test of CBTH.

Third, in comparing the CBTH and CBT Completer results, as each group received the same core CBT treatment and each received an adjunct that contained a relaxation component, the differences between them may be attributed, at least partially, to the use of clinical suggestions in the anesis stage of hypnosis, which they received via hypnosis at the end of each treatment session as well as during self-hypnosis (part of their home practice). Re-listening to the recordings to promote self-hypnosis was further reinforced as a post-treatment relapse prevention strategy. Doing so may have been more effective than simply asking participants to relax. How suggestions about managing depressogenic triggers became internalized remains unclear. Possibly for some, a one-off in-session exposure may have been sufficient, while for others, repeated exposure through home practice, or a combination thereof, may have resulted in the healthier volitional and non-volitional responses that are commonly observed in hypnosis treatment. Irrespective of how suggestions became internalized, that remission and response data on the PHQ-9 was statistically significant at 12-month follow-up suggests the potential that hypnosis added to CBT has to facilitate better mood outcomes over the longer term.

Secondary aims of this RCT were to explore whether expectancy, credibility and attitude to hypnosis were associated with mood outcome. That both groups’ expectancy scores decreased after the first session can be understood in terms of the dynamic nature of expectancies, which show more state, than trait, like characteristics (Holt & Heimberg, Citation1990; Schulte, Citation2008), and participants’ views of treatment adjusting toward a more realistic appraisal following psychoeducation (Greer, Citation1980; Holt & Heimberg, Citation1990). Interestingly, at the same time, credibility was significantly higher for the CBTH group. Furthermore, CBTH’s post-session 1 expectancy and credibility scores were significantly higher than CBT and were associated with improvement on both the PHQ-9 and MADRS across time. These RCT data are the first to show an association between outcome expectancy, hypnotic enhanced treatment and mood improvement, supporting the views of Kirsch, Yapko and others who have emphasized the significant role that this mechanism plays, though more research is required to better understand what the nature of that association is. That treatment credibility was also enhanced by the use of hypnosis is an original and unexpected finding.

Finally, we found only one significant association for attitude to hypnosis and mood improvement. While this counter-intuitive result may be attributed to our small sample sizes, it is, however, in keeping with other research on attitude to hypnosis (e.g., Green, Citation2012), and also has some parallel with research on tests of hypnotic suggestibility which has failed to find measures that can predict who is likely to benefit from hypnosis (Weitzenhoffer, Citation2002). Taken at face value, our research suggests that a positive attitude to hypnosis, while potentially helpful to some, is not a necessary pre-requisite for participants to experience mood improvement using CBTH. This novel RCT finding echoes the dictum from hypnotic suggestibility research: the best way to find out who is going to benefit from hypnosis treatment is to give them a try.

Strengths and Limitations

By implementing a CBT manual that combined proven treatment components in a unique way, our group-based results were at least commensurate with a largely individual-based treatment literature. Fidelity assessments by an independent rater verified pre-treatment levels of depression and that the same core CBT treatment was delivered to both groups. Anonymous, online self-report assessments helped to reduce bias. We monitored treatment confounds and restricted participants who sought additional treatment to the ITT sample, which left the Completer sample intact for responsivity to our treatments. We also assessed outcome expectancy and treatment credibility at screening without participants’ prior awareness of hypnosis, which allowed us to identify that the label “hypnosis” contributes to both expectancy and credibility of treatment, and its association with mood outcomes. Assessing attitude to hypnosis helped to inform us that a positive attitude is not a necessary prerequisite for a meaningful response to CBTH treatment. Finally, the use of PMR enabled us to control for adjunctive treatment as well as attribute potential between-group differences to anesis.

MDD participants are difficult to recruit at the best of times (Hughes-Morley et al., Citation2015) and we found that offering group therapy at the outset of a global pandemic added a new level of recruitment difficulty. Consequently, our study was probably under-powered, and we potentially failed to reject some null hypotheses, resulting in Type II errors. That we could not enroll more participants within study time frames was an important limitation.

Another limitation was the lack of a no-treatment control group. This meant that we could not state definitively whether our treatments were efficacious or not.

Finally, researcher allegiance may represent another limitation. It can be argued that as the first author was the lead clinician and main investigator, this may have biased our results. Notwithstanding this possibility, it was considered that he afforded the untested manual the best opportunity to benchmark what could be achieved with it. To counter potential bias, co-facilitators not only contributed to all treatment sessions but delivered most of the make-up sessions. Furthermore, all outcome assessments were completed anonymously and online, except for the follow-up MADRS’ which were all completed by a blinded research assistant.

Future Considerations

Given our results, we encourage future RCT researchers investigating CBTH for MDD to aim for larger samples and for post-treatment follow-ups that go beyond 12 months. Also, our hypnosis scripts were based on each session’s content, be it behavioral, cognitive or both, and were largely verbal-based. Future researchers may want to experiment by using more imagery-based scripts in the treatment of depression. While mechanisms of change were not a focus in this study, our experience suggested that the quality of the therapeutic relationship and group cohesiveness are important considerations. It goes without saying that participants who formed good relationships with facilitators appeared to engage better with treatment and, anecdotally, improved more though we could not test for this. Likewise, as Whitfield (Citation2010) observed, the level of personal interest and affiliation between participants are potentially important factors when examining mechanisms of change within group therapy especially, we would argue, for those with MDD.

In conclusion, although we did not find that CBTH was superior to CBT in the treatment of MDD, further research is encouraged given the trend in our results which suggests that the two treatments have the potential to perform differently over the longer term. Based on the current study, practitioners implementing CBTH can do so knowing that CBTH performs at least as effectively as standard CBT for MDD. Additionally, CBTH may have more appeal for those clients who are keen to experience different ways of processing therapeutic suggestions. Furthermore, practitioners can also have confidence knowing that a positive attitude to hypnosis is not a necessary pre-requisite for a client to achieve remission or have an effective treatment response. Finally, our results suggest that CBTH can be delivered in a cost-effective fashion by practitioners using a group psychotherapy format.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (114.5 KB)Acknowledgments

This project would have not been possible without the invaluable support and assistance from several parties. First, Dr. Michael Yapko who reviewed the hypnosis scripts and manual. Second, Dr. Prue Watson who was our research assistant on all follow-up MADRS’ and fidelity assessments. And finally, the ten co-facilitators who assisted with group therapy: Pri Mithal, Tharen Kander, Allegra di Francesco, Jasmine Macleod, Dylan Gilbey, Claudia Ong, Megan Ansell, Phoebe Carrington-Jones, Elmie Janse Van Rensburg, and Lashindri Wanigasekera.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data is available on request from the lead author.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/00207144.2024.2354722.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1. An earlier recruitment campaign in 2020 was discontinued, before undertaking any clinical assessments, due to the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic.

2. The wording was adjusted to reflect that the focus of treatment was depression. Questions: (1) How successful do you think psychological based treatment will be in reducing your depressive symptoms? (range 1 = not useful at all to 9 = very useful); (2) By the end of psychological treatment, how much improvement in your depressive symptoms do you think1 to 10.

will occur? (range 0%–100%). Question 1 is purported to measure credibility, while question 2 is a measure of outcome expectancy (Devilly & Borkovec, Citation2000).

3. By Addis and Martell (Citation2004); Beck et al. (Citation1979); Burns (Citation1999); Centre for Clinical Interventions (Citation2019); Greenberger and Padesky (Citation2016); Hopko et al. (Citation2015); Richards (Citation2020).

4. The treatment manual and hypnosis scripts are available on request from the first author.

References

- Addis, M. E., & Martell, C. R. (2004). Overcoming depression one step at a time: The new behavioral activation approach to getting your life back. New Harbinger Publications Incorporated.

- Alladin, A. (2005). Cognitive hypnotherapy for treating depression. In R. Chapman (Ed.), The clinical use of hypnosis with cognitive behavior therapy: A practitioner’s casebook (pp. 139–187). Springer Publishing Company.

- Alladin, A., & Alibhai, A. (2007). Cognitive hypnotherapy for depression: An empirical investigation. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 55(2), 147–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207140601177897

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. American Psychiatric Publications.

- Beck, A. T., Rush, J., Shaw, B. F., & Emery, G. (1979). Cognitive therapy of depression. Guildford Press.

- Burns, D. D. (1999). Feeling good: The new mood therapy (revised and updated). Avon.

- Butcher, N. J., Monsour, A., Mew, E. J., Chan, A. W., Moher, D., Mayo-Wilson, E., Terwee, C. B., Chee-A-Tow, A., Baba, A., Gavin, F., Grimshaw, J. M., Kelley, L. E., Smith, L., Thabane, L., Askie, M., Williamson, M., Farid-Kapadia, P. R., Tugwell, P., Szatmari, P., Ungar, W. J., & Offringa, M. (2022). Guidelines for reporting outcomes in trial reports: The CONSORT-Outcomes 2022 extension. Journal of the American Medical Association, 328(22), 2252–2264. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2022.21022

- Centre for Clinical Interventions. (2019). Mood management course: A group cognitive behavioural programme. https://www.cci.health.wa.gov.au/~/media/CCI/Mental-Health-Professionals/Therapist-Manuals/Mood-Management-Course–01

- Chapman, R. A. (2014). Integrating clinical hypnosis and CBT: Treating depression, anxiety, and fears. Springer Publishing Company.

- Coley, R. Y., Boggs, J. M., Beck, A., Hartzler, A. L., & Simon, G. E. (2020). Defining success in measurement-based care for depression: A comparison of common metrics. Psychiatric Services, 71(4), 312–318. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201900295

- Cooper, A. A., & Conklin, L. R. (2015). Dropout from individual psychotherapy for major depression: A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Clinical Psychology Review, 40, 57–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2015.05.001

- Cuijpers, P., Berking, M., Andersson, G., Quigley, L., Kleiboer, A., & Dobson, K. S. (2013). A meta-analysis of cognitive-behavioural therapy for adult depression, alone and in comparison with other treatments. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 58(7), 376–385. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371305800702

- Cuijpers, P., Miguel, C., Harrer, M., Plessen, C. Y., Ciharova, M., Ebert, D., & Karyotaki, E. (2023). Cognitive behavior therapy vs control conditions, other psychotherapies, pharmacotherapies and combined treatment for depression: A comprehensive meta-analysis including 409 trials with 52,702 patients. World Psychiatry, 22(1), 105–115. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.21069

- Devilly, G. J., & Borkovec, T. D. (2000). Psychometric properties of the credibility/expectancy questionnaire. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 31(2), 73–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7916(00)00012-4

- Edmonston, W. E., Jr. (1981). Hypnosis and relaxation: Modern verification of an old equation. Wiley Interscience Publications.

- Endicott, J., Nee, J., Harrison, W., & Blumenthal, R. (1993). Quality of life enjoyment and satisfaction questionnaire: A new measure. Psychopharmacology Bulletin, 29(2), 321–326.

- Fuhr, K., Meisner, C., Broch, A., Cyrny, B., Hinkel, J., Jaberg, J., Petrasch, M., Schweizer, C., Stiegler, A., Zeep, C., & Batra, A. (2021). Efficacy of hypnotherapy compared to cognitive behavioral therapy for mild to moderate depression-results of a randomized controlled rater-blind clinical trial. Journal of Affective Disorders, 286, 166–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.02.069

- Garcia, T. P., & Marder, K. (2017). Statistical approaches to longitudinal data analysis in neurodegenerative diseases: Huntington’s disease as a model. Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports, 17(2), 14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11910-017-0723-4

- Green, J. P. (2012). The Valencia scale of attitudes and beliefs toward hypnosis–client version and hypnotizability. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 60(2), 229–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207144.2012.648073

- Greenberger, D., & Padesky, C. A. (2016). Mind over mood: Change how you feel by changing the way you think (2nd ed.). Guilford Publications.

- Greer, F. L. (1980). Prognostic expectations and outcome of brief therapy. Psychological Reports, 46(3), 973–974. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1980.46.3.973

- Hammond, D. C. (2013). A review of the history of hypnosis through the late 19th century. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 56(2), 174–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/00029157.2013.826172

- Harrison, N. (2018). SP0146 the link between inflammation and depression. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 77(Suppl 2), 38.

- Hedges, L. V., & Olkin, I. (1985). Statistical methods for meta-analysis. Academic Press.

- Hoaglin, D. C., & Iglewicz, B. (1987). Fine-tuning some resistant rules for outlier labelling. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 82(400), 1147–1149. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1987.10478551

- Holt, C. S., & Heimberg, R. G. (1990). The reaction to treatment questionnaire: Measuring treatment credibility and outcome expectancies. The Behavior Therapist, 13(213–214), 222.

- Hopko, D. R., Ryba, M. A., McIndoo, C. C., & File, A. (2015). Behavioral activation. In C. M. Nezu & A. M. Nezu (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of cognitive and behavioral therapies (pp. 1–84).

- Hughes-Morley, A., Young, B., Waheed, W., Small, N., & Bower, P. (2015). Factors affecting recruitment into depression trials: Systematic review, meta-synthesis, and conceptual framework. Journal of Affective Disorders, 172, 274–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.10.005

- Jacobson, E. (1938). Progressive relaxation (2nd ed.). University of Chicago Press.

- Jensen, M. P., Adachi, T., Tome-Pires, C., Lee, J., Osman, Z., & Miro, J. (2015). Mechanisms of hypnosis: Toward the development of a biopsychological model. The International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 63(1), 34–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207144.2014.961875

- Kirsch, I. (1997). Response expectancy theory and application: A decennial review. Applied and Preventive Psychology, 6(2), 69–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0962-1849(05)80012-5

- Kirsch, I., & Low, C. B. (2013). Suggestion in the treatment of depression. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 55(3), 221–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/00029157.2012.738613

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2001). The PHQ‐9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

- Leucht, S., Fennema, H., Engel, R. R., Kaspers-Janssen, M., Lepping, P., & Szegedi, A. (2017). What does the MADRS mean? Equipercentile linking with the CGI using a company database of mirtazapine studies. Journal of Affective Disorders, 210, 287–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.12.041

- Lynn, S. J., Green, J. P., Polizzi, C. P., Ellenberg, S., Gautam, A., & Aksen, D. (2019). Hypnosis, hypnotic phenomena, and hypnotic responsiveness: Clinical and research foundations a 40-year perspective. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 67(4), 475–511. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207144.2019.1649541

- Lynn, S. J., Green, J. P., Zahedi, A., & Apelian, C. (2022). The response set theory of hypnosis reconsidered: Toward an integrative model. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 65(3), 186–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/00029157.2022.2117680

- Lynn, S. J., & Kirsch, I. (2006). Depression. In S. J. Lynn & I. Kirsch (Eds.), Essentials of clinical hypnosis: An evidence-based approach (pp. 121–134). American Psychological Association.

- Matheson, G. (1979). Modification of depressive symptoms through posthypnotic suggestion. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 22(1), 61–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/00029157.1979.10404004

- McDermut, W., Miller, I. W., & Brown, R. A. (2001). The efficacy of group psychotherapy for depression: A meta‐analysis and review of the empirical research. Clinical Psychology Science & Practice, 8(1), 98–116. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.8.1.98

- Milling, L. S. (2012). The Spanos attitudes toward hypnosis questionnaire: Psychometric characteristics and normative data. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 54(3), 202–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/00029157.2011.631229

- Milling, L. S., Valentine, K. E., McCarley, H. S., & LoStimolo, L. M. (2019). A meta-analysis of hypnotic interventions for depression symptoms: High hopes for hypnosis? American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 61(3), 227–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/00029157.2018.1489777

- Mohr, D. C., Ho, J., Hart, T. L., Baron, K. G., Berendsen, M., Beckner, V., Xuan Cai, M. S., Cuijpers, P., Spring, B., Kinsinger, S. W., Schroder, K. E., & Duffecy, J. (2014). Control condition design and implementation features in controlled trials: A meta-analysis of trials evaluating psychotherapy for depression. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 4(4), 407–423. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13142-014-0262-3

- Montgomery, S. A., & Åsberg, M. (1979). A new depression scale designed to be sensitive tochange. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 134(4), 382–389. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.134.4.382

- Munder, T., Geisshüsler, A., Krieger, T., Zimmermann, J., Wolf, M., Berger, T., & Watzke, B. (2022). Intensity of treatment as usual and its impact on the effects of face-to-face and internet-based psychotherapy for depression: A preregistered meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 91(3), 200–209. https://doi.org/10.1159/000521951

- Norman, S. B., Campbell-Sills, L., Hitchcock, C. A., Sullivan, S., Rochlin, A., Wilkins, K. C., & Stein, M. B. (2011). Psychometrics of a brief measure of anxiety to detect severity and impairment: The overall anxiety severity and impairment scale (OASIS). Journal of Psychiatric Research, 45(2), 262–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.06.011

- Ramondo, N., Gignac, G. E., Pestell, C. F., & Byrne, S. M. (2021). Clinical hypnosis as an adjunct to cognitive behavior therapy: An updated meta-analysis. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 69(22), 169–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207144.2021.1877549

- Richards, D. A. (2020). COBRA behavioral activation practice manual (part 1), CBT practice manual (part 2). https://www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/hta/hta21460/#/full-report

- Schoenberger, N. E. (2000). Research on hypnosis as an adjunct to cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 48(2), 154–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207140008410046

- Schulte, D. (2008). Patients’ outcome expectancies and their impression of suitability as predictors of treatment outcome. Psychotherapy Research, 18(4), 481–494. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503300801932505

- Sheehan, D. V., Lecrubier, Y., Harnett-Sheehan, K., Janavs, J., Weiller, E., Bonara, I., Keskiner, A., Schinka, J., Knapp, E., & Sheehan, M. F. (1997). Reliability and validity of the MINI international neuropsychiatric interview (M.I.N.I.): According to the SCID-P. European Psychiatry, 12(5), 232–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0924-9338(97)83297-X

- Spanos, N. P., Brett, P. J., Menary, E. P., & Cross, W. P. (1987). A measure of attitudes toward hypnosis: Relationships with absorption and hypnotic susceptibility. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 30(2), 139–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/00029157.1987.10404174

- Terman, S. (1980). Hypnosis and depression. In H. Wain (Ed.), Clinical hypnosis in medicine (pp. 201–208). Year Book Medical Publishers.

- Weitzenhoffer, A. M. (2002). Scales, scales and more scales. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 44(3–4), 209–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/00029157.2002.10403481

- Whitfield, G. (2010). Group cognitive–behavioural therapy for anxiety and depression. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 16(3), 219–227. https://doi.org/10.1192/apt.bp.108.005744

- Williams, J. B., & Kobak, K. A. (2008). Development and reliability of a structured interview guide for the Montgomery-Åsberg depression rating scale (SIGMA). The British Journal of Psychiatry, 192(1), 52–58. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.106.032532

- World Health Organization. (2022, March 2). “COVID-19 pandemic triggers 25% increase in prevalence of anxiety and depression worldwide [ Press release]. https://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2022

- Yapko, M. (1992). Hypnosis and the treatment of the depressions: Strategies for change. Brunner/Mazel.

- Yapko, M. (2012). Trancework: An introduction to the practice of clinical hypnosis (4th ed.). Routledge.

- Yapko, M. (2013). The role of expectancy in treating depression. In M. Yapko (Ed.), Hypnosis and the treatment of depressions: Strategies for change (pp. 117–133). Routledge.