ABSTRACT

This article focuses on presenting success factors for a group of teachers in carrying out a learning study in mathematics at their school. The research questions are: what are the actions of the school teaching community during development projects? What factors enable a group of teachers to carry out a learning study at their school? Activity theory provides a holistic framework to investigate relationships among the components present in a learning study. The results are based on analysis of interviews with teachers, students, principal organizers of schools and project coordinators, videotaped lessons, students’ tests and minutes taken at meetings of mathematics projects. The results show that the skills of facilitators, the time devoted to collaborative work, the link to learning theory and avoiding overly comprehensive content when teaching lessons are important promoting factors in mathematics teaching. The findings raise important questions about the way in which teacher work within universities.

KEYWORDS:

1. Introduction

A unique investment in mathematics began in Sweden when the National Agency for Education was given a government mandate (U2009/914/G) to allocate project funding to principal organizers of schools in support of local development projects. One of these developmental work covers the projects that used the learning study model (is discussed in the next section) in mathematics teaching. This article is about an analysis of learning study by using activity theory [Citation1–5] with the aim to advance our understanding of learning in social action and the potential for the organizational development of teacher professional development. The research questions are: what are the actions of the school teaching community during development projects? What factors enable a group of teachers to carry out a learning study at their school?

2. Theoretical framework

This section introduces learning studies that underlie teachers' professional development in this study as well as the asset theory used to indicate collected material.

2.1. Theoretical background – professional development and learning study

Current theoretical approaches found in existing studies of mathematics teacher educator development are largely based on constructivist views of teaching and learning. The notion of reflective practice is used in meta-studies where mathematics teacher educators analyse their own learning as part of a larger teacher professional development project (e.g. [Citation6–9]). Rather than appealing to cognitive or constructivist theories that treat learning as an internal mental process, many mathematics education researchers have begun to draw on sociocultural theories.

Sociocultural research has enhanced our understanding of how mathematics teachers learn from their experiences in different contexts (e.g. [Citation10,Citation11]). Sociocultural perspectives have been used to inform that teachers’ learning is better understood as increasing participation in socially organized practices that develop their professional identities [Citation12]. Solving mathematical problems together [Citation13], or using new curricular materials [Citation14], are successful models of mathematics teachers collaborative professional development. Davies and Dunnill [Citation15] found that learning study can develop trainee teachers’ thinking at an epistemic level and to develop thinking about teaching and learning within the school context. Learning study is combination of research and school development efforts [Citation16–19]. In brief, the process surrounding a learning study may be described as a multi-stage iterative process: (1) a group of teachers select something they want students to learn; (2) the content of the selected teaching is analysed as regards what is required to learn it and with respect to the prior understanding of the students involved; (3) the learning-critical aspects of the content (aspects that contribute to the development of subject-specific abilities) are identified; (4) on this basis, the group plans the teaching that is provided, observed and videotaped in one of the participating classes; (5) after the lesson has been taught, the group studies the extent to which the students have improved their understanding of the content and what they are still having difficulties with; (6) the students’ learning is related to how the teaching content was dealt with during the lesson through analysis of how the lesson was taught; (7) new critical aspects are identified and the lesson plan is revised and tested in a new class (see, e.g. [Citation16,Citation20]). The aim of a learning study is to improve students’ opportunities to learn in the classroom and is based on learning theory (variation theory or another theory), research results and proven experience. The most important idea of variation theory is that learning is a function of discernment, and discernment is a function of variation (e.g. [Citation16–18,Citation20,Citation21]).

A key aspect of a learning study is the strong emphasis on the object of learning (what the students are meant to learn) in relation to the development of subject-specific abilities/competencies. The other one is the focus to give the teachers opportunity to be competent in teaching of mathematics. From this perspective the teachers must be capable of interpreting, organizing and teaching according to the goals of the curriculum as well as being able to understand the learning of their students and develop their own teaching. The prevalence of projects directed at creating and maintaining the arrangements of relationships between teachers and research that characterize partnership in mathematics teachers professional development have not been systematically investigated [Citation22].

2.2. Activity theory

To fully understand the relations between different components involved in teachers’ professional development the theoretical framework of this study is activity theory. Activity theory (e.g. [Citation1–5]) provides a framework for considering social and cultural practices and considers the complexity of real-life activity. Edwards and Daniels [Citation23] argue that activity theory also emphasizes action or intervention in order to develop practice and the sites of practice. Activity theory is based on the principle that there is a relationship between humans, environment and the activity in which people are participating. The activity is created out of a genuine need for change. The characteristics of an activity are: (1) it has an object (motive) that describes why activity is taking place; (2) it is a collective phenomenon; (3) it has a subject (individual or group) that understands the object; (4) it has evolved over time; (5) it has conflicts; (6) it is realized through the subject's performance of deliberately useful actions; (7) that relationships within an activity are mediated through artefacts. Mediated artefacts, or tools, are used so that the subject will achieve short-term goals and meet objectives. Those, which can be considered artefacts, include instruments, signs, procedures, methods and forms of work organization [Citation4]. Conflicts that may arise in an activity lead to the evolution and change of the activity.

In this article, learning study is regarded as an activity because it meets the criteria mentioned above. The object of the activity is to improve teaching and it is a collective phenomenon that involves teachers, students, parents, school administrators, project coordinators and principal organizers of schools, etc. The subject of the activity may be teachers, students, project coordinators and principal organizers of schools, depending upon whether they have the same or different objectives in performing the activity. Mathematics teaching has developed over time and is realized through the performance of various actions by the subject. There may be conflicts and several relationships in the activity.

2.2.1. Levels of the activity

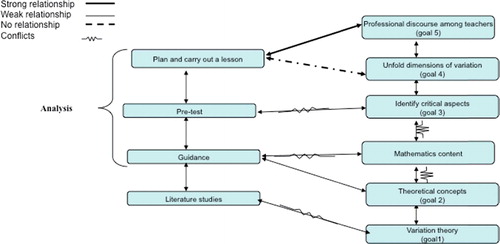

In order to analyse learning study as a mathematics activity based on the project's conditions, implementation and results, it was necessary to analyse the levels and structure of the activity [Citation1–5]. The fundamental idea in the analysis of the levels of the activity is that the activity leads to the performance of certain actions, which are governed by the goal. There may be more than one action, but each action is aimed at a single goal. Each goal is subordinate to others, up through the hierarchy to the main goal of the activity. The actions may include literature studies, guidance, pre-testing, lesson planning, lesson analysis, post-testing and relation of the students’ learning to how the content of teaching was delivered in the lesson. These actions may, for example, be aimed at the following goals: generating awareness of different ways to arrange the teaching/elicit the results of the research concerning students’ difficulties with various elements of mathematics; putting the concepts of the research into practise; identifying critical aspects; reflecting over how patterns of variation can be unfolded; expanding the professional conversation among teachers participating in the project; putting the results of the research into practise; identifying new critical aspects; completing a learning/lesson study cycle.

The characteristics of a joint action are that it is directed from a provider, such as a teacher, to a recipient, such as a student, and that a relationship is formed between these individuals through the action. The individuals have identities, values, norms, preferences, abilities, feelings, intentions and plans, as well as understandings and attention. The action is instrumental, in that the performing actor uses an instrument to transform input into a result [Citation24,Citation25]. The action is central to the activity and, in turn, is made up of operations. The term ‘operation’ refers to a well-defined procedure within the activity. At first, all operations constitute actions, but eventually, actions become operations (that is, they are performed without reflection). Operations are connected to tangible and intangible conditions, which are in turn linked to goals. The operations may include correcting tests, teaching lessons, selecting teaching materials and arranging meetings with facilitators, project coordinators and teachers. The performance of these operations is dependent upon the tangible and intangible conditions that exist at the school/within the municipality.

2.2.2. The structure of the activity

From the perspective of activity theory, people are embedded in a sociocultural context and their actions cannot be understood independently of that context. An activity thus involves not only the actions that constitute the activity, but also the context in which the actions are performed. The concept is used to denote a particular context as perceived by the subject (individual or group). In this context, every individual is involved and influences the situation through their participation. The context is built up of the actions of individuals and depends upon the environment and culture. This context is the basis for analysing the structure of the mathematics activity. The fundamental idea in analysing the structure of the activity is that it is characterized by seven main elements [Citation2,Citation3]:

Subject. Refers to the individual or group of individuals whose perspective is the focus of the analysis. Within the learning study, focus is on the activity of the collective of teachers and not that of the individual. Correspondingly, students, project coordinators and principal organizers of schools are regarded as the subject of the activity if they are the focus of the analysis.

Object. The object is the goal of the activity within the system and is the object of the subject's attention. The object cannot be separated from the motive for creating it. In this article, the goal is to improve the quality of mathematics teaching.

Tools. Tools refer to the internal or external-mediating artefacts with whose help an outcome/result of the activity occurs. The theory used in learning study (variation theory) is the instrument used in mathematics teaching.

Community. The community is made up of one or more individuals who have the same goal as the subject. In this article, the community are students, teachers, parents, headteachers, principal organizers of schools and project coordinators.

Rules. Rules govern actions and interaction within the activity system and may be explicit regulations and implicit norms that exist within the operation. Pedagogical traditions in teaching or in the perceptions of teachers, headteachers, etc., of how learning occurs may be found behind these rules. Traditional mathematics teaching in Swedish compulsory school has been characterized by practise [Citation26–28]; that is, the teacher presents the material to be learned, whereupon the student practises on similar distinct, limited tasks. The difficulty of the tasks increases step-by-step, with only one new difficulty added in each step.

Division of labour. The division of labour indicates the various roles within the system and may, for example, consist of the division of labour at the school and within the project.

Outcomes are teachers’ professional development as a result of using learning study.

There are four sub-systems in an activity system: (1) production refers to the subject–object–tool relationship; (2) exchange refers to the subject–rules–community relationship; (3) consumption refers to the subject–object–community relationship; (4) distribution refers to the object–community–division of labour relationship. Attention should also be paid to two other relationships: the subject–division of labour relationship and the rules–object relationship. We can analyse the components of each sub-system without having to implicate other sub-systems or the activity system as a whole. The focus becomes more restrictive, but the advantage is that fewer variables need to be analysed to understand what is happening in the sub-system. In the production sub-system, focus is on content because the subject (teachers) delivers/performs something based on their motives, which are intended to lead to the goal. The conflicts that may arise here might depend upon the characteristics of the learning study towards the subject achieving the predetermined goal, whether the subject can use learning study in service of their motives and to achieve the goal, or whether or not the goal is realistic. The exchange sub-system includes any changes of the formal rules upon which the activity system is based. The conflicts that may arise depend upon how the rules are interpreted and whose interpretation takes precedence. The object controls the activity in the consumption sub-system. The subject negotiates with the community on the goal of the activity. If the subject does not prevail in the negotiations, a conflict arises that may limit the subject's opportunities to attain the goal. The division of labour is controlled in the distribution sub-system by how the community understands the object and the extent of consensus concerning the object.

3. Research methodology

The methodology section is written according to the decisions made in selecting the data, tools and methods used to identify and collect information utilized to answer the research questions. Also, the analysis of data is presented in this section.

3.1. Methodology

The methods used to collect and summarize the evidence as part of this article are in accordance with the preferred reporting items for systematic meta-analyses guidelines [Citation29]. A mixed approach was adopted to ensure that a wide range of direct experiences with the professional development programs was collected, and the effects of the implementation could be understood from various perspectives of the participants in the projects [Citation30]. The method used in this work is non-experimental mixed methodology design involving a multi-component survey and interviews with selected students, teachers, project coordinators and principal organizers of schools.

3.2. Research questions

As presented in the Introduction section, the research questions in this article are: what are the actions of the school teaching community during development projects? What factors enable a group of teachers to carry out a learning study at their school?

3.3. Research population

A list of applications to start a project concerning learning study (granted and rejected) is found on the National Agency for Education's website. These applications were analysed based on the following criteria: spread across all compulsory school years (1–9), cohesive mathematics content, geographical distribution and schools of different sizes. I removed studies whose title clearly indicated the study did not use learning study. Next, I read the applications from the remaining studies and excluded those that did not meet the above criteria. Finally, three researchers from the National Agency for Education recommended each for inclusion or exclusion. Nineteen schools, 99 teachers and 2191 students were included in the actually study. Eight projects were chosen for future analyses. Nineteen schools, 99 teachers and 2191 students were included in these eight projects.

3.4. Research tools

Group interviews were chosen instead of individual interviews so that teachers would feel more secure and thus be able to speak about their experiences more openly. It was also important to be able to conduct the interviews in the shortest possible time. The interviews were held during the spring 2011 term. The project coordinator in each municipality selected the teachers to be interviewed (one or two teachers from each school year who participated in the learning study). The teachers, in consultation with headteachers and project coordinators, selected one or two students from each class participating in the learning study for a group interview. The interviews were held on school premises and all respondents consented to recording the interview. The purpose of recording the interviews was to enable better interpretation of utterances and to retain the material for future reference as needed. Each group was given brief information about the evaluation and the interviewer assured them that all utterances would be processed so that they could not be traced to a particular individual or school. The interviews began with a brief presentation of what the interviewer intended to discuss with the respondent.

An interview guide was used for all interviews, which were based on several questions about project continuation, learning study as an activity, results, dissemination of results and lasting effects, as well as the conditions required for an effective change process. Semi-structured and focus group interviews were used [Citation31,Citation32]. Interview guides for teachers, students, project coordinators and principal organizers of schools were designed. The main questions were the same but the sub-questions were adapted to each category. The interview questions were tested in one municipality that did not participate in the evaluation and the interview guide was thereafter revised.

A questionnaire was emailed to the project coordinator in early January 2011. The purpose of the questionnaire was to collect information about the conditions and results of national exams before the school visits. This was done to save time and collect any documentation that might have been missed in connection with the school visit. The questionnaire was answered by the individuals who acted as project coordinators.

3.5. Research procedure

The project coordinators were contacted by email to inform them about the overall aim of the evaluation and request an appointment to visit the school. As mentioned earlier, the project coordinator in each municipality selected the teachers to be interviewed, and the teachers selected the students to be interviewed. In each municipality:

The teachers who participated in the project were interviewed as a group for 90–120 min (64 teachers).

One or two students who participated in the project were interviewed (total of 85 students) for 20–40 min.

Principal organizers of schools were interviewed for 20–40 min (8 individuals).

Project coordinators were interviewed for 45–60 min (8 project coordinators).

Questionnaire with regard to project continuation.

Other documentation (results of national exams for years 3, 5 and 9 during 2007–2010, pre-tests, post-tests, videotaped lessons, minutes, teacher questionnaires, student questionnaires).

Applications to the grant.

3.6. Data processing

The applications, interviews and answers to the questionnaires were analysed and interpreted in several steps. Initially, the texts were read as written and annotated as to what the respondent was talking about and the issues raised in the various applications. Sub-categories were created based upon these notes. Words and phrases used by the respondents and discussed in the interviews served as indicators of the sub-categories. The respondents’ answers in each sub-category were rated on a scale of 0–4, where 4 means that the person is highly familiar with the issue raised, 3 means the person is familiar with the issue raised, 2 means the person is slightly familiar with the issue raised, 1 means the person is unable to respond to the issue raised and 0 means the person did not answer the question. The sub-categories were grouped into main categories and the rating of 0–4 made it possible to identify strengths and weaknesses in the relationships between the main categories. Strong relationships (3 and 4), weak relationships (2), no relationship (1 and 0) and conflicts could be identified.

3.6.1. The levels of the activity

For each project, the main goal of the activity is identified based on the following: interviews with teachers, students, project coordinators, principal organizers of schools; answers to the questionnaire; applications. Thereafter, the material was analysed to determine whether there were any interim goals and what actions were performed to achieve these interim goals. Finally, the conditions in each municipality for performing these actions were analysed, as well as which actions occur automatically – that is, which actions became operations.

3.6.2. The structure of the activity

The analysis of the structure of the activity began with the analysis of interviews, questionnaires and applications to identify who is practising the activity (subject) and whether they have the same or different motives (object) for performing the activity (learning study). Thereafter, the fundamental norms and conventions prevailing in the community (rules) were identified. Finally, I analysed who does what: how the work towards the object is performed (division of labour). Four relationships could be identified: strong relationship (S); weak relationship (W); no relationship (N); conflicts (Cx). The relationships are connected to the sub-systems: subject–object–tool; subject–rules–community; subject–object–community; object–community–division of labour; subject–division of labour; and rules–object relationship. Conflicts are observable in the daily flow of actions and are experienced and articulated by the subject.

4. Results

Project conditions and outcomes were analysed with respect to the structure of the activity, while project performance was analysed with respect to the levels of the activity.

4.1. Levels of the activity

Learning study, as used in the projects analysed, is based on a variation theory perspective (e.g. [Citation20,Citation33]) and various levels () were identified in the analysis of the process (i.e. the iterative process). The first level involves reading literature or articles and the aim of this action is for the teachers to become familiar with and understand key concepts in variation theory, such as object of learning, critical aspects and dimensions of variation. It is difficult to determine the extent to which concepts in variation theory were presented by representatives of the university. Too little time was set aside to become familiar with the process and theoretical concepts to be used in carrying out the learning study and the teachers reported that it was difficult to understand based on a single presentation by representatives of the university. Several teachers emphasize that a learning study cannot be carried out successfully with no help other than one lecture, that they need a sounding board. These teachers note that the quality is not the same if there is no time and guidance because they need help in the beginning to transition to this way of thinking.

The second level involves setting boundaries to the mathematics content upon which the learning study is focused. The aim here is to identify the content upon which the design of the pre-test and the teaching of lessons are to be based. The third level is to design a pre-test, whose aim is to identify critical aspects in the students’ learning and what abilities are intended to be developed through the teaching. It emerges from the collected documentation that the teachers in all projects first identified critical aspects and thereafter designed a pre-test. To a great extent, the teachers identified critical aspects as follows:

In our experience, rounding off is mentioned in mathematics textbooks and other materials without any direct context and without any direct connection to students’ situations. (T)

At the fourth level, teachers jointly plan a lesson and videotape it. The aim of this action is to reinforce the professional conversation among teachers participating in the project with focus on the mathematics content. Another aim was to put into practise the way in which dimensions of variation were unfolded in the critical aspects of the learning object. The teachers’ perceptions of collaboration with colleagues are described as follows:

Collaboration and focus on content have increased. Collaboration has improved between different schools, within the same school and between different groups. Collaboration among the headteachers has improved. (T)

Collaboration in terms of talking about content has increased during the project. There was not much of that in the past. We became more aware of each other as educators. (T)

When asked about which dimensions of variation they had unfolded in the critical aspects of the content, most teacher groups reported:

Have not worked with dimensions of variation. (T)

A few teacher groups expressed that:

It takes time to learn how to create these [dimensions of variation]. Which tasks should we choose? Creating dimensions of variation is another way of thinking. (T)

The analysis of the videotapes and PowerPoint presentations made by the teachers shows that they have unfolded various dimensions of variation to a great extent. In spite of this, the teachers have not truly understood what they have done or cannot verbally express what they have done. The most interesting aspect is that the teacher, based on the content addressed, uses various forms of work organization; that is, they use concrete materials, smartboards, small writing boards and other technical equipment.

The fifth and six levels involved analysing the extent to which the students have developed their knowledge about the content and what they still have problems with in relation to the lesson taught. The aims here include strengthening the professional conversation among the teachers with focus on the mathematics content presented in the classroom, as demonstrated by students when they solve various problems on the post-test. Based on the documentation submitted, it is clear that the teachers could identify what needed to be improved in the next lesson and why this needed to be done:

The post-test showed that the children could still not circle the one, the ten and the hundred in a three-digit number. Nor could they create the largest integer out of four given numbers. We used too much concrete material. It took too long. (T)

We see that little details in how we express ourselves can make a difference, for example, “How do you write a half fraction?” or “Can you write a half fraction?” (T)

Based on the analysis of the students’ results on the post-test and how the content was dealt with in the classroom, the teachers planned a new lesson that was analysed in the same way described before.

Differences between operations (the teachers’ routine work) and the conditions for performing these operations could be identified in the analysis of the levels of the activity. The difference refers to the time set aside for reading literature, organization and the guidance the teachers were given by the university during the course of the project. The guidance was provided mainly via email correspondence (lesson plans, pre-tests, etc., were sent to the facilitator) and through seminars with representatives of the university or seminars with municipal mathematics improvement coordinators who had not worked with learning study.

4.2. Structure of the activity

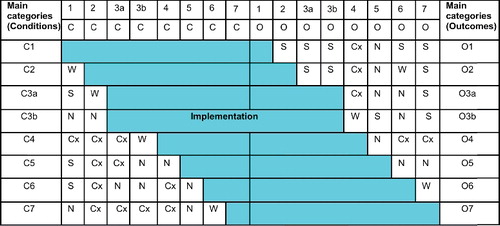

In the analysis of the structure of the activity, which refers to the project conditions/outcomes, the following main categories could be identified: (1) variation theory (tool); (2) project planning/lasting effects for teachers and students (subject); (3) students’ abilities (3a) and teachers’ abilities (3b) (object); (4) conditions at the school (rules); (5) stakeholders (community); (6) role of the principal organizer of schools (division of labour); (7) project goal/achievement goals (outcomes). Instead of using triangles to indicate the relationships among the sub-systems of the activity, I prefer using a table (). The table represents the sub-systems and the identified relationships among each sub-systems.

The project conditions are characterized by strong or weak relationships, no relationships and conflicts. Strong relationships are manifested in clear descriptions provided in the applications about how the process will take place, the aim of performing the learning study, the abilities that will be focused on during the project, the mathematics content and the needs of the school/municipality. Most teachers had not seen the application, but expressed a strong need to improve mathematics teaching due to shortcomings in the attainment of learning targets. It emerges from the interviews with teachers, project coordinators and principal organizers of schools that other students, teachers and staff at the schools mainly had a positive attitude towards the mathematics initiative, but that they had not contributed in any way to implementation of the project. In spite of this, one principal organizer of schools mentioned that there were instances of an ‘envious attitude’ because other teachers who teach other subjects wanted the same opportunity to further develop their teaching.

Several weak relationships could be identified in the analysis, which refer to planning prior to the project and understanding of learning study, such as the link to the theoretical perspective on learning; the content and the number of students stated on the applications and support for the project among teachers. In most projects, the headteachers, who were also the project coordinators, planned the project and drew up the guidelines for carrying out the project. The reason for this was that:

We talked with the teachers, but there were few ideas, so we started this. (PC)

Other weak relationships refer to: conditions at the school, project planning and the abilities that students and teachers were meant to develop through the use of learning study in mathematics teaching; the role of the principal organizer of schools in creating opportunities at the schools in preparation for the learning study and awareness of the goals of the project. Most teacher groups mention that:

He [the principal organiser of schools] signed the application. He is in favour of it, but is not participating actively in carrying out the learning study. (T)

There were several conflicts early in the project, which refer to conditions at the school and the use of learning study in mathematics teaching, project planning and the abilities students and teachers were meant to develop. Most teacher groups bring up lack of time, organizational problems and support for the project among the teachers. Teachers are those who find joint time for analysis, planning, etc. Supply teachers entailed an additional workload because the teachers had to devote additional time to planning lessons for supply teachers. Compensation was provided afterwards, which entailed uneven workloads. Time for working on the project was not set aside in the timetable and most teachers read the literature in their free time:

We were to use supply teachers when we were going to analyse the videos, which is great, but also takes work. We have to plan for supply teachers, it's not just a matter of calling someone in. We must be given time to sit down, plan and analyse. (T)

The teachers read the literature in their spare time and were compensated for the work that was done. We were compensated afterwards and many found that burdensome. (T)

The cost of supply teachers and supervision (which was relatively low compared to, for example, the purchase of materials) was stated on the applications, but in spite of this the projects were added to everything else. The teachers worked full-time and were compensated at a later date.

Conflicts occur as regards the relationship between project planning and the community, the role of the principal organizer of schools and the goals to be achieved by carrying out the project. The project coordinator did not take into account the conditions at the school and the teachers’ participation in other projects on going in the municipality.

Quite a few relationships referring to the structure of the activity were not found early in the project. The most important is the relationship between the use of learning study in mathematics teaching and the development of students’ abilities through teaching.

It could be determined in the analysis of project outcomes that several relationships have become stronger, conflicts have become fewer, but there are still relatively many relationships that are lacking (). In all interviews, it was reported that both teaching quality and target attainment have increased due to the work with learning study. Several principal organizers of schools report that they have observed an increase in target attainment in the municipality and that the schools that participated in the projects were included in the statistics. Carrying out these projects has contributed to the attainment of other goals related to the work of the teachers; for example, that teachers could free up time from planning, performing and further developing pedagogical activities on their own. This is now done collaboratively by focusing on didactic discussions and the content delivered in the classroom. Most teacher groups express that the most positive experience was the opportunity to discuss content-related issues, as a group, which can be directly related to the students’ learning. Some of the teachers’ perceptions of the process they underwent may be a sign of the change in their skills:

It was terrific because it makes things so clear and it was good to discuss the content with others. It is easier to talk to colleagues about the same things. You think the same way, you speak the same language. You don't have to explain various terms over and over again. This has been a tremendous boost to our pedagogical discussions. (T)

Pre-testing is a great way to figure out how we should start. We shouldn't start on the ground floor when the students are already on the third floor. This got us, the staff, thinking. (T)

In a learning study, you examine the content, which you don't do if you use other methods. It is a different perspective compared with other methods. (T)

The following emerged from the documentation submitted and the teacher interviews:

Clear improvement. Everyone has developed. The students who have had problems improved the most. Even those who found maths easy had an “aha” experience. (T)

The analysis of the students’ results on the pre-tests and post-tests show that all students in the classes that participated in teaching based on the learning study model have achieved better target attainment. One teacher describes the effects of learning study on her teaching as follows:

The most remarkable change in my teaching has been the questions I ask myself. The first question I ask myself is “What do I want the students to learn in this lesson?” Although this might seem like an obvious question to ask, I hadn't thought about it before I began the learning study process. The question I used to ask was “What am I going to teach today?”

Overall, the teachers perceive the project work as highly rewarding because they were given the opportunity to work with colleagues in a new way by having didactic discussions about specific mathematics content based on the students’ demonstrated knowledge in the pre-tests and post-tests and the analysis of videotaped lessons. The teacher groups have assumed collective responsibility by jointly planning the teaching.

Figure 2. Project conditions (C) and outcomes (O) – structure of the activities and relationships (S-strong relationship; W-weak relationship; N-no relationship; Cx-conflicts).

The teachers who participated in the projects bring the experiences gained during the projects with them when teaching other subjects. Some municipalities have a thought-out plan for putting teachers’ knowledge to good use, but in most cases there is none. Learning study is integrated into the individual teacher's teaching. The schools’ continued efforts are affected by things such as support from management, guidance and time set aside for joint work.

5. Discussion

Conclusions that can be drawn based on the presented results and which should be considered by a group of teachers who want to use the learning study model as an activity in mathematics teaching are: (1) it is important to understand the theory of learning used in a learning study; (2) the facilitator should be able to run a learning study and have knowledge in mathematics; (3) the focus should be shifted from working methods and procedures to examining how content is delivered to students; (4) project planning is significant; (5) time for meetings and reading literature should be timetabled; (6) the abilities the students should develop through the use of learning study in mathematics teaching; (7) the principal organizer of school's awareness of the goals of learning study.

It is obvious that teachers in the learning study projects are determined to improve mathematics teaching in spite of insufficient understanding of the use of a theory of learning in the process (variation theory in these cases). One explanation for this, offered by several teacher groups, is that the guidance they received was inconsistent and in most cases did not meet the teachers’ expectations – the facilitator should be able to run a learning study and have mathematics knowledge. Good results are impossible if the facilitator cannot provide both. Variation theory is used only to a minor extent and in an unaware way as the point of departure in the collegial collaboration and for lesson planning. In spite of this, teachers have taken the step from mainly discussing work organization and the students’ social and physical environment to truly examining in detail how they can deliver the content in classroom teaching.

Although the actual learning study process did not work well, the teachers have gained an opportunity to talk and reflect about their teaching with colleagues. This, in and of itself, has elevated the standard of teaching. The teachers have shifted focus from work organization and environment to examining how content is delivered to students. All students improved, but those who have made the most progress are the students who have struggled with mathematics and who have had the greatest need for clear explanations. The three abilities with which teachers believe students have made the most progress are: the ability to reason, conceptual understanding and the ability to communicate (with emphasis on written communication). For learning study to produce good results, the organization should be involved in the change and school administrators must, from the outset, allow time in the teachers’ regular timetables for working with learning study. Another fundamental prerequisite is that the facilitator must have knowledge in the fields of mathematics and learning study.

The teachers develop their knowledge about teaching when they are committed to studying their own practise in collaboration with other teachers through focusing on delivery of mathematics content in relation to student learning. The teachers discuss the academic content of mathematics in relation to mathematics at the schools, which gives them the sense, that ‘You think you understand maths, but then you discover how little you understand maths.’ The collegial collaboration involved in analysing the students’ results on various tests and planning the content to be presented to the students leads to reflection and direct feedback about the effects of teaching on students’ learning.

The teachers are enthusiastic, motivated and demonstratively committed to critically examining the content of mathematics teaching and are open to collaborating with others. The quality of teaching can be improved if teachers are offered opportunities to work with other teachers and through a highly focused commitment to student learning. The more learning study becomes standard practise for all teachers, for teachers at a school and part of what teachers do, the greater impact it will have on the quality of mathematics teaching, which results in better learning for the students.

In summary, we can say that a group of teachers can use the learning study model as an activity in mathematics teaching if they have the opportunity to collaborate with colleagues, reflect on the teaching of lessons in relation to student learning, discuss the academic content of mathematics in relation to mathematics at the school, have access to guidance, be given various forms of feedback (from colleagues, facilitators, students, headteachers, principal organizers of schools) and be given the right conditions, such as time blocked out in the timetable. Because teachers from various programmes are often included in the same working group, the issue of time should be resolved as far as possible before the initiative begins.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the school, the teacher and children that participated in this study. Thank you for sharing your experiences and thoughts with me. I would also like to thank the National Agency of Education.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- Bloomfield D , Nguyen HT . Creating and sustaining professional learning partnerships: activity theory as an analytic tool. Aust J Teach Educ. 2015;40(11):22–44.

- Engeström Y . Learning by expanding: an activity-theoretical approach to developmental research. 2nd ed. Cambridge ( UK ): Cambridge University Press; 2015.

- Engeström Y . Learning by expanding – an activity-theoretical approach to developmental research [dissertation]. Helsinki: Orienta-Konsultit; 1987.

- Kuutti K . Activity theory and its application to information systems research and development. In: Nissen HE , Klein HK , Hirschheim R , editors. Information systems research: contemporary approaches and emergent traditions. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science Publishers; 1991. p. 529–548.

- Ladel S , Kortenkamp U . An activity-theoretic approach to multi- touch tools in early mathematics learning. Int J Technol Math Educ. 2013;20(1):141–145.

- Cheng CK . Learning Study: nurturing the instructional design and teaching competency of pre-service teachers. Asia-Pac J Teach Educ. 2014;42(1):51–66.

- Even R . Facing the challenge of educating educators to work with practising mathematics teachers. In: Jaworski B , Wood T , editors. International handbook of mathematics teacher education. Vol. 4, The mathematics teacher educator as a developing professional. Rotterdam : Sense; 2008. p. 57–73.

- Holmqvist M . Teachers’ learning in a learning study. Instr Sci. 2011;39(4):497–511.

- Zaslavsky O , Leiken R . Professional development of mathematics teacher educators: growth through practice. J Math Teach Educ. 2004;7:5–32.

- Bohl J , Van Zoest L . The value of Wenger's concepts of modes of participation and regimes of accountability in understanding teacher learning. In: Pateman NA , Dougherty BJ , Zilliox JT , editors. Proceedings of the 27th annual Conference of the International Group for the Psychology of Mathematics Education. Vol. 4. Honolulu ( HI ): PME; 2003. p. 339–346.

- Graven M . Investigating mathematics teacher learning within an in-service community of practice: the centrality of confidence. Educ Stud Math. 2004;57:177–211.

- Lerman S . A review of research perspectives on mathematics teacher education. In: Lin F-L , Cooney TJ , editors. Making sense of mathematics teacher education. Dordrecht : Kluwer; 2001. p. 33–52.

- Lachance A , Confrey J . Interconnecting content and community: a qualitative study of secondary mathematics teachers. J Math Teach Educ. 2003;6(2):107–137.

- Horn IS . Learning on the job: a situated account of teacher learning in high school mathematics departments. Cogn Instr. 2005;23(2):207–236.

- Davies P , Dunnill R . Learning study as a model of collaborative practice in initial teacher education. J Educ Teach. 2008;34(1):3–16.

- Lo ML , Marton F . Towards a science of the art of teaching: using variation theory as a guiding principle of pedagogical design. Int J Lesson Learn Stud. 2012;1(1):7–22.

- Lo ML , Marton F , Pang MF , et al. Toward a pedagogy of learning. In: Marton F , Tsui ABM , editors. Classroom discourse and the space of learning. Mahwah ( NJ ): Lawrence Erlbaum; 2004. p. 189–225.

- Pang MF , Lo ML . Learning study: helping teachers to use theory, develop professionally, and produce new knowledge to be shared. Instr Sci. 2012;40(3):589–606.

- Runesson U . Focusing on the object of learning and what is critical for learning: a case study of teachers’ inquiry into teaching and learning mathematics. Perspect Educ. 2013;31(3):170–183.

- Marton F . Necessary conditions of learning. New York ( NY ): Routledge; 2015.

- Guo JP , Pang MF , Yang LY , et al . Learning from comparing multiple examples: on the dilemma of “similar” or “different”. Educ Psychol Rev. 2012;24(2):251–269.

- Llinares S , Krainer K . Mathematics (student) teachers and teacher educators as learners. In: Gutierrez A , Boero P , editors. Handbook of research on the psychology of mathematics education: past, present and future. Rotterdam : Sense; 2006. p. 429–459.

- Edwards A , Daniels H . Using sociocultural and activity theory in educational research. Educ Rev. 2004;56(2):107–111.

- Kaptelinin V . The object of activity: making sense of the sense-maker. Paper presented at: Fifth Congress of the International Society for Cultural Research and Activity Theory (ISCRAT 2002); 2002; Amsterdam, Netherlands .

- Vygotsky LS . Mind in society: the development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge ( MA ): Harvard University Press; 1978.

- Lundgren UP . Frame factors and the teaching process. Stockholm : Almqvist & Wiksell; 1972.

- Magne O . Mathematics learning – a trip into the interior. In: Gran B , editor. Mathematics on the student's condition. Lund : Studentlitteratur; 1998. p. 99–124.

- Neuman D . The origin of arithmetic skills. Vol. 62, Studies in educational science. Göteborg : Acta Universitatis Gothoburgensis; 198 7.

- Liberati A , Altman DG , Tetzlaff J , et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. Res Methods Rep. 2009;339:3–50. Available from: http://www.bmj.com/content/339/bmj.b2700.

- Teddle C , Tashakkori A . Major issues and controversies in the use of mixed methods in the social and behavioral sciences. In: Tashakkori A , Teddle C , editors. Handbook of mixed methods in social & behavioral research. Thousand Oaks ( CA ): Sage; 2003.

- Ely M . Kvalitativ forskningsmetodik. Lund : Studentlitteratur; 1993.

- Kvale S , Brinkmann S . The qualitative research interview. Lund : Studentlitteratur; 2009.

- Marton F . Learning study – educational development directly in the classroom. Research of this world –Practical research in education science pedagogisk. Vetenskapsrådets rapportserie. 2004;2:41–45. (Swedish Research Council Report Series 2).