Abstract

Most depressed adolescents in Low and Middle Income Countries (LMICs) like Nigeria have no access to psychological intervention due to lack of trained mental health professionals. This huge treatment gap could be bridged by using non-mental health professionals such as teachers to deliver the interventions. This study evaluated a teacher-delivered Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) programme for depressed adolescents in Nigeria. Forty adolescents (aged 13–18 years) with clinically diagnosed depressive disorder were recruited from two schools (20 from each school). One school was balloted as intervention and the other as control. The intervention group received five sessions of manualised group-based CBT delivered by two teachers who were trained and supervised by a psychiatrist. Primary outcome was BDI score at week 6. Controlling for baseline BDI score, the intervention group had significantly lower post-intervention depressive symptoms {Means 4.60 vs 17.05; t = 4.13; p = 0.0001, F(1, 39) = 16.76, p = 0.0001, Effect Size (Cohen’s d) = 1.3}. Eighty-percent of the intervention group achieved remission compared with only 15.8% of the controls (p < 0.0001). To our knowledge, this is the first study of a teacher-delivered CBT programme for clinically depressed adolescents in a LMIC. The intervention was feasible, well received and showed promising efficacy.

Introduction

Depression is the third most common cause of Years Lived with Disabilities in adolescence (Kyu et al., Citation2016). The condition causes significant functional impairment for affected adolescents, their families and the wider community through poorer educational and social outcomes. Also, depression increases the risk of premature mortality from suicide, which is among the leading cause of death in this age group (WHO, Citation2016). The burden of adolescent depression is high with average worldwide prevalence of 5.6% (Costello et al., Citation2006). The burden is highest in Low and Middle Income Countries (LMICs) (Thapar et al., Citation2012). Despite this high burden, most depressed adolescents in LMICs go untreated (Thapar et al., Citation2012). Over 90% of depressed adults in some LMICs receive no treatment (Patel et al., Citation2016) which suggests that the treatment gap for children and adolescents will be similar or higher (Patel et al., Citation2013). This massive treatment gap means that millions of adolescents in LMICs are experiencing avoidable suffering and increased risk of suicide from depression.

The effectiveness of psychological interventions such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and Interpersonal Therapy (IPT) for adolescent depression is now well established (Weersing et al., Citation2017). These interventions are recommenced as first line in many national guidelines and by the World Health Organization Mental Health Gap Action programme (mhGAP) (WHO, Citation2008). Yet access is very limited in LMICs due to lack of professionals with the expertise to deliver the interventions. Many LMICs have 1.4 mental health workers per 100,000 population compared with a global average of 9.0 per 100,000 (WHO, Citation2016). This huge gap in workforce means that using trained mental health workers to deliver treatment in LMICs would reach only a small proportion of depressed adolescents.

Task-shifting is a strategy to improve treatment access in settings with limited numbers of trained mental health professionals (Javadi et al., Citation2017). For example, a recent systematic review found support for task-shifting as a helpful tool for increasing access to mental health interventions in sub-Saharan Africa (Galvin & Byansi, Citation2020). In relation to depression, several studies in LMICs have demonstrated that non-mental health professionals such as lay counselors (Patel et al., Citation2017), primary health workers (Rahman et al., Citation2008), and lay workers (Chibanda et al., Citation2016) can deliver psychological interventions such as CBT and Behavioral Therapy. However, most studies of successful implementation of task-shifting in the treatment of depression in LMICs have focused on adults. A few studies have used non-mental health professionals to treat adolescents in LMICs but they tended to focus on post-trauma symptoms (van Ginneken et al., Citation2013; Ventevogel & Spiegel, Citation2015).

Teachers are a professional group that have had limited involvement in task-shifted treatment of child and adolescent mental health difficulties in LMICs (van Ginneken et al., Citation2013). Due to increasing school enrollment in LMICs (Fazel et al., Citation2014) which now averages about 70% (World Bank, Citation2020), teachers may be higher in relative numbers compared with trained mental health workers. Unlike mental health clinics which tend to be in urban areas, schools are available in both urban and rural areas of LMICs (Fazel et al., Citation2014). Teachers already have experience of working with children, which means that extending their skill to provide psychological intervention may be easier than for other professionals who are not used to working with children. Studies have shown that teachers can be involved in the delivery of mainly preventative mental health interventions for children (Fazel et al., Citation2014; Franklin et al., Citation2012; Sutan et al., Citation2018). For universal level (Tier 1) intervention, the effect sizes of solely teacher-delivered interventions can be similar to when same interventions are delivered by professionals (Franklin et al., Citation2012). A few studies in LMICs have used teachers to deliver interventions for mainly post-traumatic symptoms (Fazel et al., Citation2014). However to the best of the authors’ knowledge, no previous clinical trial has evaluated a teacher-delivered CBT intervention for adolescents with clinically diagnosed depressive disorder in a LMIC.

Most of the evidence for psychological interventions for adolescent depression is from High Income Countries (HICs) and based on delivery by skilled mental health professionals (Patel et al., Citation2017). While some evidence is emerging from LMICs, there remains a need for further contextualization to close current gaps in knowledge (Patel et al., Citation2017). One such gap is whether CBT delivered by regular teachers can be effective in treating adolescents with clinically diagnosed depression. This gap is important for two reasons. First, existing studies of CBT for adolescent depression in LMICs have tended to use professionals to deliver the intervention (Bella-Awusah et al., Citation2016). This is neither scalable nor sustainable. On the other hand, successful delivery of CBT for adolescent depression by teachers could hugely improve access to treatment in LMICs (Fazel et al., Citation2014). Secondly, if teachers are able to deliver CBT, they may also achieve better sustainability of any treatment gains by reinforcing the key messages through their classroom work (Franklin et al., Citation2012).

The current study was designed to assess whether regular teachers can be trained to effectively deliver CBT for adolescents with clinically diagnosed depressive disorder. The focus in the current study on adolescents with clinically diagnosed depressive disorder is an important distinction from previous studies of teacher-delivered interventions. While studies have shown that teachers can solely and successfully deliver preventative (Tier 1) interventions, this did not apply to students with more specific and complex mental health difficulties (Tier 3) for whom targeted intervention was required by more specialized mental health professionals (Franklin et al., Citation2012). Thus the current study is a major step-up by aiming for teachers to treat “clinical cases” that would otherwise require treatment by mental health professionals.

Methods

Study design and location

This was a controlled two-group intervention study conducted in two secondary schools in Zaria, Kaduna State in North-West Nigeria. Zaria is one of the largest cities in Northern Nigeria with a population of 406,990. The city hosts the Ahmadu Bellow University which is one of the largest Universities in Nigeria. Zaria has 49 publicly funded secondary schools spread across four Local Government Areas (LGAs). Balloting was used to select two LGAs (Sabon gari and Zaria LGAs) for this study. Further balloting was used to designate Sabon gari as the intervention LGA and Zaria as the control LGA. The eleven public co-educational schools in Sabon gari LGA were numbered and SPSS-generated random number used to select one school as the intervention site. Another public co-educational school located in a similar neighborhood and with similar teacher-student ratio was purposively selected from Zaria LGA as the wait-list control school. Ethical approval was given by the Ethical Review Committee, Kaduna State Ministry of Health. Permission was also obtained from the Kaduna State Ministry of Education.

Participants

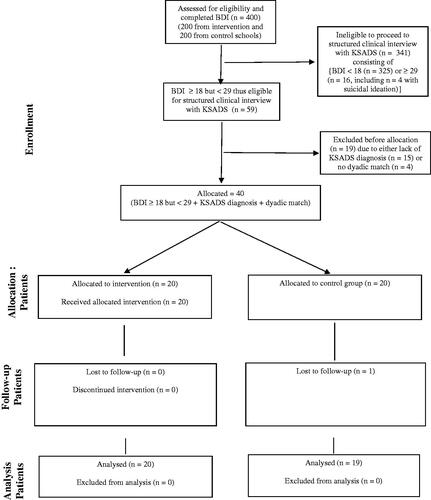

Participants were in-school adolescents aged 13−18 years whose parents or carers provided consent and the students gave assent. Six hundred students in Senior Secondary Classes 1–3 (300 each from the intervention and control schools) were selected by SPSS-generated random numbers and invited to take part in the study. The first 200 students in each school to provide parental consent and personal assent were selected and asked to complete the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI). Students who scored 18 or above on the BDI in both schools were selected for further assessment. A cutoff of 18 was based on a previous study of Nigerian adolescents that identified this figure as being indicative of clinically significant depressive symptoms (Adewuya et al., Citation2007). The selected students had structured clinical interview by a psychiatrist using the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia Present and Lifetime (K-SADS-PL) to confirm a diagnosis of depressive disorder based on DSM-IV criteria. The top 20 scorers on BDI who had a confirmed diagnosis of depressive disorder in the intervention school were recruited for the study. Each student recruited from the intervention school was dyadically matched for gender, BDI score (± 4 points), and a confirmed diagnosis of depressive disorder with a student from the control school. A priori sample size calculation identified a sample of 16 in each group as adequate to detect a reduction of one standard deviation in BDI scores in the intervention group compared with the control group with 80% power and 5% two-sided alpha (Noordzij et al., Citation2010). This figure was increased to 20 in each group to account for potential attrition in the course of the study. Previous intervention studies in this region have shown that a sample of 20 in each group is adequate to idenitfy the level of difference hypothesized in this study (Abdulmalik et al., Citation2016; Bella-Awusah et al., Citation2016). Students were excluded if; their teachers identified them as having learning difficulties, they disclosed past or current history of treatment for a psychiatric disorder, they answered positive to item 9 on the BDI (presence of suicidal thoughts), or they scored 29 or above on the BDI which is suggestive of severe depressive disorder. Students in the latter two categories, and those diagnosed with depresive disorder but not selected for the study were referred to Ahmadu Bello University Teaching Hospital Zaria for treatment. Twenty students in the intervention group and 19 controls completed the post intervention measures. Participants’ flow is shown in .

Procedure

Intervention

This was a manualised CBT intervention delivered by two teachers in the intervention school. The teachers were trained and supervised by the first author (AA) who is a psychiatrist with post-graduate training in Child and Adolescent Mental Health. The CBT manual was developed by the last author (CA) and had been used successfully in three previous studies in Nigeria (Bella-Awusah et al., Citation2016; Isa et al., Citation2018; Taiwo et al., Citation2020). However, this study was the first time it was delivered by non-mental health professionals. The manual is designed to be delivered in groups to enhance cost-effectiveness. The content of the intervention is weighted in favor of behaviorally based strategies. This weighting is informed by evidence of the effectiveness of behavioral intervention for depression (Cuijpers et al., Citation2007) in both HICs (Richards et al Citation2016) and LMICs (Patel et al., Citation2017). It also took into account that behavioral strategies are easier to explain by persons without mental health expertise (Ekers et al., Citation2008). The CBT manual’s development contextualized it to include local metaphors and encouragement of helpful preexisting cultural and religious coping strategies used by both Christians and Muslims in Nigeria.

The intervention school had a staff meeting and nominated two female teachers to be trained to deliver the intervention. Due to a need to balance religious sensitivities in the region, one of the nominated teachers was a Christian and the other was a Muslim. The first author trained the teachers over a three week period. The training took place in the school and consisted of hour-long sessions over eight days. This training included explanation of depression, principles of CBT and more extended explanation of behavioral strategies. Key psychotherapeutic principles such as confidentiality, empathic listening and non-judgmental approach were emphasized and distinguished from usual teachers’ classroom management approaches. The CBT manual was demonstrated for the teachers several times. They practised using the manual repeatedly by role play until they became confident and the trainer was assured of high fidelity against the manual’s content. In addition to the CBT manual, the training materials included two well recognized mental health resources for non-mental health professionals namely, “Where there is no Psychiatrist” (Patel, Citation2003), and the “mhGAP intervention manual” (WHO, Citation2010). At the end of the training, both teachers achieved 100% accurate answers on the Adolescent Depression Knowledge Questionnaire (see description under “Measures”). The teachers were paid a one off honorarium of 5,000 Naira (equivalent to $12) each in acknowledgement of the extra work involved in receiving training and delivering the intervention. The intervention started 10 days after the teachers completed their training. The trainer, both teachers, and all the students were fluent in English and the local Hausa language. The manual was translated into Hausa so that the teachers had the choice of delivery in either language.

The intervention was delivered jointly by the two teachers in a group for all 20 students. The sessions took place in a comfortable room which was not a classroom. The room was made exclusively available for the programme to assure privacy. The intervention consisted of weekly one-hour sessions over five weeks. The sessions were conducted during break periods in order to limit interference with the students’ academic work. The school break normally lasted an hour but for the duration of the study, the school authorities extended the break for all students to 1½ hours so that the participants could still have time to refresh themselves before resumption of their classes.

The first session set ground rules including confidentiality. The assurance of confidentiality was particularly important to enable the students to express their emotional difficulties in the presence of their teachers and peers. This was more so as they were hitherto used to seeing teachers as directive authority figures. The first session also focused on psycho-education including features of adolescent depression, the fact that it is treatable, and the need to avoid self-blame for associated functional impairments. The reciprocal links between cognitions, emotions and behavior were explained. Participants were encouraged to generate helpful positive self-talk which could include religious-based coping strategies commonly used in the local population. The second session explained the basis for behavioral activation. Participants were assisted to identify pleasurable activities for themselves and how to monitor the effect on their mood. Almost all participants identified singing as one of the activities they enjoyed. This observation led the participants to agree unanimously to include brief periods of group singing in subsequent sessions. During the third session, more pleasurable activities were identified and the activity scheduling initiated in the second session was reinforced. The fourth session focused on relaxation strategies including deep breathing exercises, progressive muscle relaxation and positive imagery. The fifth session reviewed all the techniques taught in previous sessions. At the end of each session, participants were given brief assignments to help them to practise the newly learnt skills. New sessions started with a recap of what was discussed in the previous week and to trouble-shoot any difficulties participants encountered in practising the new skills. Light refreshment was offered at the end of each session. The two teachers and all 20 students in the intervention group participated in all the five CBT sessions. The first author observed all sessions and confirmed high fidelity in the teachers’ use of the treatment manual. The teachers consistently described their experience of each session as positive. Students in the control group received no parallel intervention during the programme. Students in both intervention and control groups completed the post intervention outcome measures a week after the last treatment session. Both groups were also clinically re-assessed by a psychiatrist using K-SADS-PL. The psychiatrist was blinded to group assignment.

Measures

Six instruments were used for this study namely, socio-demographic questionnaire, Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Rosenberg self-esteem scale, Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for school-age - Present and Lifetime (K-SADS-PL), Adolescent Depression Knowledge Questionnaire, and a Client Satisfaction Questionnaire. The measures were translated into Hausa language by a linguist in the Department of Hausa Language at Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria. Fidelity of the translation was assured through iterative back translation. The translation allowed students the choice of completing the measures in English or Hausa.

Sociodemographic questionnaire

This was adapted from a sociodemographic questionnaire previously used in the setting (Omigbodun et al., Citation2008). The questionnaire sought the following characteristics: age, gender, religion, parents’ marital status, family type (monogamous or polygamous), who the child lives with, father and mother’s level of education, and father’s occupation (recoded into “manual” or “professional”) ().

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of participants in intervention and control groups.

Beck depression inventory (BDI)

The Beck Depression Inventory is a 21-item self-rated measure of depressive symptoms in the previous two weeks designed for use among individuals aged 13 years and older (Beck et al., Citation1996). The items are rated on a 4-point Likert scale (0−3) giving a maximum score of 63. Scores of 14−19 indicate mild depression, 20−28 moderate depression and 29−63 severe depression (Beck et al., Citation1996). The BDI has been validated among Nigerian adolescents with a cutoff score of 18 and above indicating clinically significant depressive symptoms (Adewuya et al., Citation2007). It showed good internal consistency in the current study (Cronbach Alpha 0.85)

Rosenberg self- esteem scale (RSES)

This is a reliable and widely used self-report measure of global self-worth (Rosenberg, Citation1965). The 10 items are answered on a four point scale - from strongly agree to strongly disagree (scored 0–3) and summed such that higher scores indicate higher self-esteem. Its validity has been demonstrated in a Nigerian population (Loto et al., Citation2009) and it has been used in studies among Nigerian adolescents (Adewuya et al., Citation2007). The internal consistency in the present study was good (Cronbach Alpha 0.83).

Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children- Present and Lifetime (K-SADS-PL)

The K-SADS-PL is a semi-structured diagnostic interview that assesses current and past episodes of psychopathology in children and adolescents between ages 6 and 18 years based on DSM-IV criteria (Kaufman et al., Citation1997). It assesses a wide range of DSM-IV coded psychiatric diagnoses and has been used successfully in several studies of Nigerian adolescents (Adeniyi & Omigbodun, Citation2017; Adewuya et al., Citation2007). The Major Depressive Disorder Module was used is in this study. The interview was administered by a Senior Resident in Psychiatry who was trained in the use of the instrument by a Consultant Psychiatrist.

Adolescent Depression Knowledge Questionnaire (ADKQ)

This 20 item questionnaire was used to assess the adolescents’ knowledge of depression including the etiology, symptoms and treatment. The questionnaire was adapted from a previous study (Hart et al., Citation2014) and has been used among Nigerian adolescents (Isa et al., Citation2018). Five of the questions were based on the intervention manual in order to make the measure more specific for this study. The participants indicated if each statement is “true” or “false.” Correct answers were assigned a score of “1” and incorrect answers “0.” The scores were summed to create a scale such that higher scores indicated better knowledge. This questionnaire was administered only to the intervention group to assess their pre-post understanding of the psycho-educational component of the intervention. The questionnaire was also used to quality control the teachers’ training prior to starting the intervention. The instrument showed good internal consistency (Cronbach alpha 0.79).

Client satisfaction questionnaire

Participants in the intervention group were asked to comment on the following three questions to gain their views on (a) what they liked most about the intervention, (b) what they did not like about the intervention, and (c) any suggestions for improving the programme. The qualitative comments were analyzed thematically.

Data management

The data was analyzed using SPSS version 20. Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages. The BDI, RSES, and ADKQ scores were summarized as Means and Standard Deviations. Between-group differences in sociodemographic characteristics and outcome measures were examined with t-test for continuous variables and Chi-square test for categorical variables. The treatment effect was determined with Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) of post-intervention scores on the BDI and RSES between the groups while controlling for baseline scores. Effect sizes were calculated as Partial eta squared (ƞp2) with 0.01, 0.06 and 0.14 representing small, medium and large effect sizes respectively (Cohen, Citation1988). Within-group difference in the intervention group’s ADKQ pre-post scores was assessed with paired t-test. Post-intervention change in depression diagnostic category based on repeat K-SADS-PL was assessed with Chi-Square test. Level of significance was set at 0.05 two tailed for all tests. Qualitative comments in the client satisfaction questionnaire were analyzed thematically.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics of study participants and baseline scores on outcome measures

The participants ranged in age from 12 to 18 years (M = 15.27 years; SD = 1.63). Ten (25.0%) were males while 30 (75.0%) were females. shows that the two groups were gender and aged matched. Majority of the students in both groups were from monogamous homes, and most had parents who were currently married. Most of their parents had secondary or higher level of education. The two groups were similar in sociodemographic characteristics except for two variables. First, all 20 students in the control group (100%) were Christians while the intervention group had seven students who were Muslims (35%) (p = 0.008). Secondly, students in the intervention group were more likely to have mothers with less than secondary school education (50% vs 10%, p = 0.01).

For baseline outcome measures, the intervention and control groups had similar BDI scores {Mean 24.30 (SD 6.59) vs Mean 24.25 (SD 6.06), t = −0.03, df 38, p = 0.98} but the intervention group recorded significantly lower self-esteem scores than the control group {Mean 12.75 (SD 5.59) vs Mean 16.10 (SD 3.89), t = 2.21, df 38, p = 0.03}.

Effect of the intervention on depression and self esteem

ANCOVA () shows statistically significant differences in the post-treatment BDI and RSES scores between the intervention and control groups controlling for their respective baseline scores. The intervention group scored significantly lower on depressive symptoms than the control group [BDI {F(1, 39) = 16.76, p = 0.0001, (ƞp2 = 0.32}], and higher on self-esteem [RSES {F (1, 36) = 7.47, p = 0.01 (ƞp2 = 0.17}]. Both effects sizes were large. Including age, gender, religion, and mother’s level of education in each model had no significant effect. The post intervention BDI scores between the two groups differed by more than one standard deviation.

Table 2. Comparisons between intervention group and waitlist control group on outcome measures.

Whereas all participants had a confirmed diagnosis of depression as a criterion for inclusion in the study, repeat of the structured clinical interview with K-SADS-PL showed that post treatment, 16 out of the 20 students in the intervention group (80%) no longer met the criteria for a diagnosis of depressive disorder compared with only 3 of the 19 in the control group (15.8%) (Fishers Exact Test, p = 0.0001). The students in both groups who still met clinical criteria for a depressive disorder were referred to Ahmadu Bello University Teaching Hospital for treatment.

Effect of the intervention on knowledge of depression

Paired t-test showed that the intervention group’s knowledge of depression improved significantly after the treatment compared with baseline {Mean 15.45 (SD 2.24) vs Mean 18.0 (SD 1.65), t = −6.17, df 19, p = 0.0001} with a large Effect Size (Cohen’s d) of 1.3.

Participants’ feedback

The treatment group identified what they liked most about the intervention as; relaxation exercises (50%), advice about managing negative thoughts (33%), and the singing that was introduced after the second session (25%). Most participants (92%) indicated that there was nothing they did not like about the intervention. One participant stated that the programme brought back a difficult past memory. Suggestions to improve the intervention included incorporating more physical activities (43%), using video clips to improve the psycho-education (33%) and making the programme longer (33%).

Discussion

This teacher-delivered CBT intervention was effective in treating adolescents with clinically diagnosed depressive disorder. The treatment significantly reduced depressive symptoms in the intervention group by more than one standard deviation compared with the control group. Also 80% of the intervention group no longer met clinical criteria for depressive disorder compared with 15.8% in the control group. The treatment groups’ self-esteem improved with a large effective size (Cohen’s d) of 0.8. The psycho-educational component of the intervention led to a significant improvement in the intervention group’s knowledge of depression with a large effect size (Cohen’s d) of 1.3. These significantly improved clinical outcomes occurred after only five sessions of CBT delivered by teachers with no mental health training prior to the study.

To our knowledge, this study is the first publication assessing the effect of teacher-delivered CBT in adolescents with clinically diagnosed depressive disorder in a LMIC. The uniqueness of the study is highlighted further by the fact that being clinically diagnosed, this cohort of depressed adolescents treated by the teachers would otherwise require care by trained mental health professionals (NICE, Citation2019). Also, these adolescents with clinically diagnosed depressive disorder are less likely to achieve spontaneous recovery in the short term without treatment (Goodyer et al., Citation1997). This is evidenced by the fact that 84% of the control group still met the criteria for clinical depression at the end of the study. Several key aspects of this study have significant implications for global health.

The first and most significant implication is the successful delivery of CBT intervention by regular teachers with no prior mental health training. This is a crucial contribution to the concept of “task-shifting” as a strategy for meeting the huge treatment gap for mental disorders in LMICs. Task-sifting involves the use of non-mental health professionals to deliver mental health interventions (Javadi et al., Citation2017). The strategy is supported by the World Health Organization and experts in global health (Patel, Citation2012). A recent systematic review found support for task-shifting as a strategy for improving access to mental health interventions in sub-Saharan Africa (Galvin & Byansi, Citation2020). Several studies in LMICs have successfully demonstrated the use of lay counselors (Patel et al., Citation2017), primary health workers (Rahman et al., Citation2008), and lay workers (Chibanda et al., Citation2016) to deliver CBT and Behavioral Therapy for adults with depressive disorder. Other studies have used non-mental health professionals to deliver interventions for children and young people with Post-Traumatic Symptoms (Fazel et al., Citation2014; van Ginneken et al., Citation2013; Ventevogel & Spiegel, Citation2015).

However, no studies in LMICs have used regular classroom teachers to deliver CBT for adolescents with clinically diagnosed depressive disorder. The use of teachers in this circumstance has several advantages. First, the relatively high school enrollment in LMICs (World Bank, Citation2020) means that teachers could be among the most widely available professionals in these settings. Secondly, teachers already have skills and experience of working with children. Thus extending teachers’ skills to enable delivery of psychological intervention may be easier than for other professionals whose existing jobs do not involve frequent interaction with children. Thirdly, using teachers to deliver CBT intervention may be more cost effective because a modest financial supplement to their existing wages may be enough to fund the extra work involved. However, the additional cost of training and supervising the teachers may dent the cost-effectiveness.

Despite the advantages of using teachers to deliver CBT intervention, we had a number of concerns about this strategy prior to the study. However, the concerns were not borne out during the study. The first concern relates to confidentiality. The level of confidentiality required for a mental health intervention is much higher than in education-based teacher-student interaction. This is because educational-based interactions do not instigate the types and depth of emotional expression and self-disclosure that can occur in a therapeutic intervention. Bearing this mind, we strongly reiterated the importance of confidentiality during the teachers’ training, and in the first intervention session. The importance of confidentiality was also re-emphasized at the start of each session. These strategies appeared to have sufficiently addressed this concern; hence no student expressed a worry about confidentiality in their feedback. Our second concern was whether teachers would be willing to redeploy their time and skill to deliver the intervention. On the contrary, we were pleasantly surprised by the high level of enthusiasm shown by the two teachers and the whole teaching staff in the intervention school about the project. At the request of several teachers, the first author (AA) organized a one-day workshop on adolescent depression. The session took place at the end of the project and was attended by 43 teachers in the intervention school.

Another important implication of the current study is the delivery of the intervention in-school and during school hours. These factors provide additional advantages over and above the delivery by teachers. First, this arrangement offers further improvement in treatment access because the affected children would not need to make separate, sometimes arduous journeys to a mental health clinic to receive treatment. Moreover, such journeys incur additional financial costs for the family and result in the children missing out on education. Secondly, the children’s parents would not need to accompany them to the clinic thereby avoiding missing out on work and other income generating activities. Thirdly, the affected students may be less concerned about mental health stigma if the intervention is school-based compared with attending a Child and Adolescent Mental Health Clinic (Bella-Awusah et al., Citation2019). These advantages may help to explain why all 20 students in the intervention school attended all five treatment sessions.

Consistent with other recent studies in LMICs, this study adopted a brief intervention strategy that is predominantly behaviorally based (Bella-Awusah et al., Citation2016; Patel et al., Citation2017). A brief intervention is easier to fit into the school timetable with less disruption for students and teachers. We adopted mainly behaviorally based interventions because they are easier to explain by non-specialists and easier for patients to understand (Ekers et al., Citation2008). Also, behavioral interventions have been shown to be as effective as cognitive interventions in depression (Richards et al Citation2016). A recent study in India that involved extensive theory-driven process of developing psychological intervention adopted Behavioral Therapy (Healthy Activity Programme) as most relevant and culturally appropriate in that setting (Chowdhary et al., Citation2016; Patel et al., Citation2017).

Psycho-education is important in the psychological treatment of depression (Donker et al., Citation2009). In the current study, the psycho-educational component was used to address common misconceptions about depression. For example, an adolescent with a depressive symptom of lethargy can be mis-judged by their parents/carers and teachers as being “lazy.” If this interpretation is internalized by the depressed adolescent, the outcome could be increased self-blame for associated functional impairment such as non-completion of tasks. The psycho-education also addressed a common belief that mental illnesses like depression are not treatable. Addressing this nihilist belief can help to engender hope. The fact that the two main components of the intervention in this study namely, psycho-education and behavioral intervention have good evidence base and are relatively easy to explain by non-mental health professionals make them attractive in other resource limited settings.

The strengths of this study include the use of a sample with clinically diagnosed depressive disorder. This minimizes doubts about the reliability of the participants’ diagnosis and confirms the high threshold of their symptoms and impairments. A second strength is the inclusion of an outcome measure based on post-intervention categorical change in diagnostic status. These two strengths represent improvements over previous studies (Bella-Awusah et al., Citation2016; Patel et al., Citation2017) that selected participants and assessed outcomes with depression rating scales. A further strength is that the delivery of the intervention by the two teachers was supervised by a psychiatrist who was in a position to facilitate referral for specialist intervention in the event that a participant deteriorated. The need for such a referral did not arise in the course of the intervention but the teachers felt reassured by knowing that this back-up was in place. Finally, while the intervention involved mainly behavioral strategies, the inclusion of basic cognitive techniques was highlighted positively in the participants’ feedback.

The findings of the current study should be viewed in the light of some limitations. Consistent with other clinical trials of depressed adolescents, we excluded students who were severely depressed and or suicidal. We believe it was more ethical to refer such students for immediate specialist treatment. Furthermore, we did not account for other potential psychiatric co-morbidities or specific psychosocial concerns. These two aforementioned points mean that the treatment effects demonstrated in the study are limited to adolescents with moderately severe depressive disorder in the context of no other known psychiatric or psychosocial concerns. The diagnosis of depressive disorder with K-SADS-PL was based on DSM-IV criteria because the research team did not have access to K-SADS-PL for DSM-5. The sample size is relatively small and derived from two publicly funded schools. This limits the wider generalizability of the findings. Lack of additional follow-up data means that sustainability of the treatment gains is uncertain. The use of an inactive control group as in this study is known to increase the effect size of interventions. The intervention school did not share with the research team the criteria used for nominating the two female teachers other than to represent religious balance. This makes it difficult to advise on what characteristics may be helpful in selecting teachers for future studies. However it would seem appropriate to consider recruiting teachers who are already involved in providing counseling or supporting students with Special Educational Needs. These teachers’ existing roles would have exposed them to more awareness of child and adolescent mental health difficulties.

In conclusion, this teacher-delivered CBT intervention for adolescents with clinically diagnosed depressive disorder showed significant reduction in depressive symptoms and change in categorical diagnosis of depressive disorder. The two teachers who delivered the intervention, and the rest of the teaching staff in the intervention school were enthusiastic about the programme. The intervention was well received by the students. Future research should focus on replicating our findings with larger multicentre randomized controlled trials to assess the wider efficacy, sustainability, and cost effectiveness of using teachers to deliver CBT for clinically depressed adolescents. The trials should include a back-up referral pathway so that students who deteriorate in the course of receiving a teacher-delivered intervention can quickly access specialist mental health intervention.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the students and teachers who participated in the study

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Abdulmalik, J., Ani, C., Ajuwon, A. J., & Omigbodun, O. (2016). Effects of problem-solving interventions on aggressive behaviours among primary school pupils in Ibadan, Nigeria. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 10(1), 31. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-016-0116-5

- Adeniyi, Y., & Omigbodun, O. (2017). Psychometric properties of the self-report strengths and difficulties questionnaire (SDQ) in a Nigerian adolescents sample. International Neuropsychiatric Disease Journal, 10(2), 1–9. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.9734/INDJ/2017/37760

- Adewuya, A. O., Ola, B. A., & Aloba, O. O. (2007). Prevalence of major depressive disorders and a validation of the Beck Depression Inventory among Nigerian adolescents. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 16(5), 287–292. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-006-0557-0

- Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Brown, G. K. (1996). Manual for the Beck depression inventory - II. Psychological Corporation.

- Bella-Awusah, T., Ani, C., Ajuwon, A., & Omigbodun, O. (2016). Effectiveness of brief school-based, group cognitive behavioural therapy for depressed adolescents in south west Nigeria. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 21(1), 44–50. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12104

- Bella-Awusah, T., Ani, C., Ajuwon, A., & Omigbodun, O. (2019). Should mental health be addressed in schools? Preliminary views of in-school adolescents in Ibadan. Nigeria. International Journal of School Health, 6(2), 1–6. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5812/intjsh.85937

- Chibanda, D., Weiss, H. A., Verhey, R., Simms, V., Munjoma, R., Rusakaniko, S., Chingono, A., Munetsi, E., Bere, T., Manda, E., Abas, M., & Araya, R. (2016). Effect of a primary care–based psychological intervention on symptoms of common mental disorders in Zimbabwe: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA, 316(24), 2618–2626. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.19102

- Chowdhary, N., Anand, A., Dimidjian, S., Shinde, S., Weobong, B., Balaji, M., Hollon, S. D., Rahman, A., Wilson, G. T., Verdeli, H., Araya, R., King, M., Jordans, M. J. D., Fairburn, C., Kirkwood, B., & Patel, V. (2016). The Healthy Activity Program lay counsellor delivered treatment for severe depression in India: Systematic development and randomised evaluation. British Journal of Psychiatry, 208(4), 381–388. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.114.161075

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioural sciences (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Costello, E. J., Erkanli, A., & Angold, A. (2006). Is there an epidemic of child or adolescent depression. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 47(12), 1263–1271. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01682.x

- Cuijpers, P., van Straten, A., & Warmerdam, L. (2007). Behavioral activation treatments of depression: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 27, 318–326. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2006.11.001

- Donker, T., Griffiths, K. M., Cuijpers, P., & Christensen, H. (2009). Psychoeducation for depression, anxiety and psychological distress: A meta-analysis. BMC Medicine, 7(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-7-79

- Ekers, D., Richards, D., & Gibody, S. (2008). A meta-analysis of randomized trials of behavioural treatment of depression. Psychological Medicine, 37, 23–27. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291707001614

- Fazel, M., Patel, V., Thomas, S., & Tol, W. (2014). Mental health interventions in schools in low-income and middle-income countries. The Lancet. Psychiatry, 1(5), 388–398. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70357-8

- Franklin, C. G., Kim, J. S., Ryan, T. N., Kelly, M. S., & Montgomery, K. L. (2012). Teacher involvement in school mental health interventions: A systematic review. Children and Youth Services Review, 34(5), 973–982. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.01.027

- Galvin, M., & Byansi, W. (2020). A systematic review of task shifting for mental health in sub-Saharan Africa. International Journal of Mental Health, 49(4), 336–360. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00207411.2020.1798720

- Goodyer, I. M., Herbert, J., Secher, S. M., & Pearson, J. (1997). Short-term outcome of major depression: I. Comorbidity and severity at presentation as predictors of persistent disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 36(2), 179–187. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199702000-00008

- Hart, S. R., Kastelic, E. A., Wilcox, H. C., Beaudry, M. B., Musci, R.J., Heley, K. M., Ruble, A. E., & Swartz, K. L. Achieving depression literacy: The adolescent depression knowledge questionnaire. School Mental Health, 6(3), 213–223. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-014-9120-1

- Isa, E. W., Ani, C., Bella-Awusah, T., & Omigbodun, O. (2018). Effects of psycho-education plus basic cognitive behavioural therapy strategies on medication-treated adolescents with depressive disorder in Nigeria. Journal of Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 30(1), 11–18. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2989/17280583.2018.1424634

- Javadi, D., Feldhaus, I., Mancuso, A., & Ghaffar, A. (2017). Applying systems thinking to task shifting for mental health using lay providers: A review of the evidence. Global Mental Health, 4, e14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2017.15

- Kaufman, J., Birmaher, B., Brent, D., Rao, U., Flynn, C., Moreci, P., Williamson, D., & Ryan, N. (1997). Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): Initial reliability and validity data. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 36(7), 980–988. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021

- Kyu, H. H., Pinho, C., Wagner, J. A., Brown, J. C., Bertozzi-Villa, A., Charlson, F. J., Coffeng, L. E., Dandona, L., Erskine, H. E., Ferrari, A. J., Fitzmaurice, C., Fleming, T. D., Forouzanfar, M. H., Graetz, N., Guinovart, C., Haagsma, J., Higashi, H., Kassebaum, N. J., Larson, H. J., … Vos, T. (2016). Global and national burden of diseases and injuries among children and adolescents between 1990 and 2013: Findings from the global burden of disease 2013 study. JAMA Pediatrics, 170(3), 267–287. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.4276

- Loto, O. M., Adewuya, A. O., Ajenifuja, O. K., Orji, E. O., Owolabi, A. T., & Ogunniyi, S. O. (2009). The effect of caesarean section on self-esteem amongst primiparous women in South-Western Nigeria: A case-control study. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine: The Official Journal of the European Association of Perinatal Medicine, the Federation of Asia and Oceania Perinatal Societies, the International Society of Perinatal Obstetricians, 22(9), 765–769. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/14767050902801660

- NICE. (2019). Depression in children and young people: Identification and management. NICE guideline [NG134] Published date: 25 June 2019. Retrieved July 13, 2020, from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng134/resources/depression-in-children-and-young-people-identification-and-management-pdf-66141719350981

- Noordzij, M., Tripepi, G., Dekker, F. W., Zoccali, C., Tanck, M. W., & Jager, K. J. (2010). Sample size calculations: Basic principles and common pitfalls. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation, 25(5), 1388–1393. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfp732

- Omigbodun, O., Dogra, N., Esan, O., & Adedokun, B. (2008). Prevalence and correlates of suicidal behaviour among adolescents in Southwest Nigeria. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 54, 34–39. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764007078360

- Patel, V. (2012). Global mental health: From science to action. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 20(1), 6–12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/10673229.2012.649108

- Patel, V. (2003). Where there is no psychiatrist: A mental health care manual. RCPsych Publications.

- Patel, V., Kieling, C., Maulik, P. K., & Divan, G. (2013). Improving access to care for children with mental disorders: A global perspective. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 98(5), 323–327. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2012-302079

- Patel, V., Weobong, B., Weiss, H. A., Anand, A., Bhat, B., Katti, B., Dimidjian, S., Araya, R., Hollon, S. D., King, M., Vijayakumar, L., Park, A.-L., McDaid, D., Wilson, T., Velleman, R., Kirkwood, B. R., & Fairburn, C. G. (2017). The Healthy Activity Program (HAP), a lay counsellor-delivered brief psychological treatment for severe depression, in primary care in India: A randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 389(10065), 176–185. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31589-6

- Patel, V., Xiao, S., & Chen, H. (2016). The magnitude of and health system responses to the mental health treatment gap in adults in India and China. Lancet, 388(10063), P3074–P3084. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00160-4.

- Rahman, A., Malik, A., Sikander, S., Roberts, C., & Creed, F. (2008). Cognitive behaviour therapy-based intervention by community health workers for mothers with depression and their infants in rural Pakistan: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 372(9642), 902–909. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61400-2

- Richards, D. A., Ekers, D., McMillan, D., Taylor, R. S., Byford, S., Warren, F. C., Barrett, B., Farrand, P. A., Gilbody, S., Kuyken, W., O'Mahen, H., Watkins, E. R., Wright, K. A., Hollon, S. D., Reed, N., Rhodes, S., Fletcher, E., & Finning, K. (2016). Cost and Outcome of Behavioural Activation versus Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for Depression (COBRA): A randomised, controlled, non-inferiority trial. The Lancet, 388(10047), 871–880. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31140-0

- Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press.

- Sutan, R., Nur Ezdiani, M., Muhammad Aklil, A. R., Diyana, M. M., Raudah, A. R., Fadzrul Hafiz, J., & Khalid, M. (2018). Systematic review of school-based mental health intervention among primary school children. Journal of Community Medicine and Health Education, 8(1), 589. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4172/2161-0711.1000589

- Taiwo, T., Atilola, O., Ani, C., & Ola, B. (2020). Effect of behavioural therapy on depression in adolescents with sickle cell disease. Open Journal of Psychiatry, 10(03), 127–140. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4236/ojpsych.2020.103013

- Thapar, A., Collishaw, S., Pine, D. S., & Thapar, A. K. (2012). Depression in adolescence. The Lancet, 379(9820), 1056–1067. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60871-4

- van Ginneken, N., Tharyan, P., & Lewin, S. (2013). Non-specialist health worker interventions for the care of mental, neurological and substance-abuse disorders in low- and middle-income countries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 11, CD009149.

- Ventevogel, P., & Spiegel, P. (2015). Psychological treatments for orphans and vulnerable children affected by traumatic events and chronic adversity in Sub-Saharan Africa. JAMA, 314(5), 511–512. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.8383

- Weersing, V. R., Jeffreys, M., Do, M. C. T., Schwartz, K. T., & Bolano, C. (2017). Evidence base update of psychosocial treatments for child and adolescent depression. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology: The Official Journal for the Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, American Psychological Association, Division 53, 46(1), 11–43. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2016.1220310

- WHO. (2016). Health statistics and information systems. Global Health Estimates (GHE). Retrieved July 12, 2020, from https://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/en/

- WHO. mhGAP. (2008). Mental health gap action programme. Scaling up care for mental, neurological and substance use disorders. World Health Organization.

- World Bank. (2020). School enrolment, secondary (% gross) - Low & middle income countries. Retrieved July 12, 2020, from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SE.SEC.ENRR?locations=XO&name_desc=false

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2010). mhGAP intervention guide for mental, neurological and substance use disorders in non- specialized health settings: mental health Gap action Programme (mhGAP). WHO.