Abstract

Researchers who are aiming to conduct high quality mental health research in resettled refugee populations are likely to experience multiple challenges in their work. To our knowledge, there is no overview of these challenges and their implications for the quality of research from a researchers’ perspective. We conducted a systematic literature search to further complete the overview of challenges. Lastly, we placed the findings of the thematic analysis and the literature search in a conceptual framework derived from the social ecological model of Bronfenbrenner. Our findings indicate that common research challenges, such as high drop-out rate or low treatment fidelity, must be understood in the light of multiple levels such as the individual, microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem and macrosystem level. This will help future researchers to increase the understanding of the complex interplay of factors that play a role when facing challenges in their work and to create possibilities for improvement.

Introduction

Challenges in conducting mental health research among resettled refugee populations are visible in the limitation section of most published studies. Commonly reported limitations of mental health studies include: a lack of random selection of the participants, the absence of a control group, small sample sizes, high drop-out rates, low treatment fidelity, cultural and linguistic barriers, obtaining meaningful informed consent and overinvolvement of the researchers with subjects (Block et al., Citation2013; Hugman et al., Citation2011; Jacobsen & Landau, Citation2003; Leaning, Citation2001; Mackenzie et al., Citation2007; Slobodin & de Jong, Citation2015). As far as we know, none of the reviews on the ethical and methodological limitations of mental health research in refugees have focused on an overview and a deeper understanding of the interplay between all the challenges that the individual refugee researcher faces. A deeper understanding of the interplay will help researchers to find solutions for common limitations in refugee research.

A widely used theoretical model that generates insight in the multiple factors associated with a complex problem is the ecological model of Bronfenbrenner (Citation1979, Citation1986, Citation1995). This model presents the environmental influences to a problem from multiple levels (i.e., the individual level, microsystem, mesosystem and exosystem). Using the ecological framework to describe multiple levels associated with a certain issue offers the opportunity to provide strategies at multiple levels in order to alleviate the challenges that are faced in complex situations. It has been successfully used in former studies trying to understand complex issues with interrelated factors and relationships such as the mental health of refugee children or the well-being of clinicians during the COVID-19 pandemic (Adibe, Citation2021; Hayes, Citation2021). In the current study, we aim to adapt the ecological model to gain insight in different perspectives, and to describe the challenges faced by researchers when conducting research amongst resettled refugees.

By presenting the challenges of research within an ecological model, we aim to raise the awareness of researchers and policy makers concerning pitfalls that might be faced when conducting refugee research. Moreover, we aim to generate insight in the complex interaction of factors that play a role in these challenges. This new awareness and understanding might help future researchers when they design their protocol of research, thereby improving feasibility and consequently the quality of data.

Methodology

Systematic search

Literature search strategy

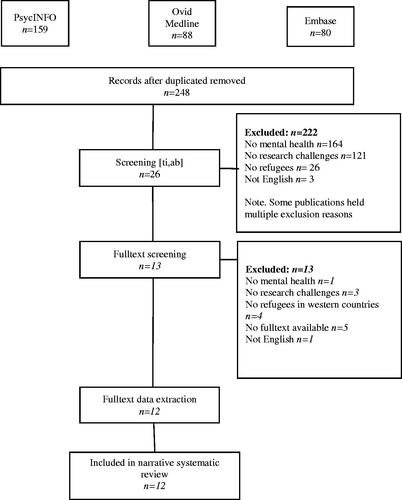

The literature search was conducted using the following databases: PsycINFO, Ovid Medline and Embase and was completed January 17, 2020. The search strategy was designed in accordance with the population, intervention/interest, and outcome (PIO) strategy of the World Health Organization (WHO, Citation2014). The following PIO was formulated: population: refugees; interest: mental health research; outcome: challenges. The full search strategy can be found in .

Table 1. Complete search syntax.

The abstracts of all articles were imported in the online software Rayyan (Ouzzani et al., Citation2016). Duplicates were excluded. Then, the titles and abstracts were independently reviewed for eligibility by CE and AL (inter-rater agreement percentage was 88%). The titles and abstracts of the conflicted articles were then screened by MD. Subsequently, the potential eligible titles and abstracts were full text screened and reviewed to determine final eligibility by MD and NM (inter-rater agreement percentage was 100%).

Selection criteria

To be eligible for our study, the articles needed to be written in English and the published studies had to be conducted on humans. Furthermore, we were exclusively interested in articles describing challenges in conducting mental health research in resettled refugees in western countries.

Data extraction

From the included studies, MD and NM independently extracted descriptions of challenges that the individual refugee researcher may face and placed them at the appropriate level of the Bronfenbrenner model (inter-rater agreement percentage was 83%).

Results

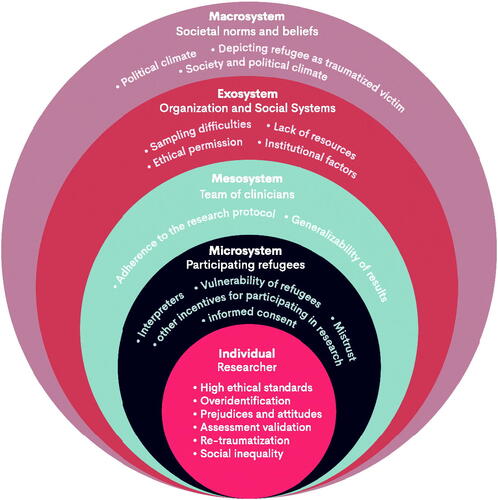

Defining the levels of the ecological model

The “individual” level (first level), focuses on the individual researcher conducting the research. The second level concerns the “microsystem”; the level closest to the individual level. The microsystem interacts directly with the individual level. Within our conceptual framework the microsystem reflects the direct interpersonal interactions between the researcher and the participating refugees. In the third level, the “mesosystem,” we have included the relationships between the researchers and the team of colleagues and clinicians. The fourth level, the “exosystem,” reflects the aspects of the organization and social system of the refugee and the researcher that influence the researcher and the research study. Lastly, the “macrosystem,” is the most distant level that does not directly interact with the individual level, but still may have an indirect impact on the researcher and the research study. In our framework, the macrosystem refers to societal norms and beliefs from the broader environment or society of the researcher and the refugee.

Systematic search

Search results

After removing duplicates, 248 records were screened based on titles and abstracts. Thereafter, 26 studies were reviewed full text. The screening process and the number of studies at each stage of the search are described in . Thirteen studies were included in our study.

Data extraction

The challenges described in the included studies were placed at the appropriate level of the Bronfenbrenner model ().

Table 2. Data extraction of the included studies.

The ecological model of challenges faced in refugee research from a researchers’ perspective

We have placed the challenges in the ecological model. An overview can be seen in .

Figure 2. Socio-ecological model, based on Bronfenbrenners Ecological Systems Theory (Citation1979).

Individual level: the role of the individual researcher

At this level, we focused on the challenges the individual researcher might face while conducting research with a refugee population. While carrying out this type of research, researchers are often faced with misery from all regions of the world (Carlsson et al., Citation2014). Moreover, they might be confronted with unfair consequences from political decision-making processes for an individual refugee. According to several studies, researchers uphold high ethical standards when working with refugee populations (Carlsson et al., Citation2014; De Haene et al., Citation2010; Ellis et al., Citation2007; Goodkind et al., Citation2017). This combination may provoke strong emotions in the researcher (Rousseau, Citation1993).

An example is offered by Goodkind et al. (Citation2017), when researching the effectiveness of a community-based advocacy, learning, and social support intervention, the researchers helped participants access resources. Although this might have interfered with the research design and outcomes, the researchers stated they prioritized ethical standard above the study design, as they felt this was their responsibility. Also, not helping could affect the reputation of the study in the target group. Moreover, the researcher can start to over-identify with the refugees and might decide to carry out activist activities next to one’s research project, leading to being prone to bias and affecting the objectivity of the researcher (Ellis et al., Citation2007; Rousseau, Citation1993).

Furthermore, personality characteristics of the researcher, including prejudices and attitudes, can have an impact on the study. For example, Carlsson et al. (Citation2014) point out that clinicians might hold the opinion that refugees are too vulnerable to participate in research. However, Robila and Akinsulure-Smith (Citation2012) describe that researchers did not necessarily experience that refugees in their sample were too vulnerable or risked re-traumatization. In their study, only 10–15% of the patients chose not to participate, suggesting that it might be a concern of the researcher rather than that of the refugee. Moreover, attitudes of the researchers might be affected by social stereotypes. In addition, researchers can interpret responses based on their own cultural understanding. This can result in bias, for example influencing the formulation of research questions and interpretation of results (Pernice, Citation1994). Robila and Akinsulure-Smith (Citation2012) highlighted the importance of being familiar with the background and context of the research topic, as well as being aware of one’s own political views. Moreover, the researcher should be aware of social inequality existing between the researcher and the participant. For example, if a reward is offered for participation in research, this might coerce participants with financial difficulties to participate in research (Robila & Akinsulure-Smith, Citation2012).

A practical problem many researchers face while designing a research project among refugees, is the choice of the measurement used to answer the research questions. Several issues with assessment validation exist. Most questionnaires are developed in Western countries and are validated in Western samples. Translations are often based on the assumption of similar symptoms across cultures. However, manifestations and expression of mental health symptoms can vary widely across cultures (Pernice, Citation1994). Translation should focus on language, including cultural appropriateness of questions, as well as the translation of concept (Robila & Akinsulure-Smith, Citation2012) Because of these challenges, there is a lack of culturally reliable and valid methods, and often used quantitative assessment might not be adequate for assessing symptoms in the refugee population (Robila & Akinsulure-Smith, Citation2012; Rousseau, Citation1993).

In conclusion, the most important pitfalls we have encountered at this level are: high ethical standards, overidentification, prejudices and attitudes, re-traumatization, social inequality, and assessment validation.

Microsystem: the participating refugee

At the second level, we focused on the participating refugees, and their impact on the individual researcher. As a researcher working with refugees, one can encounter mistrust from the participating refugee. Rousseau (Citation1993) describes the idea that the researcher might “represent” the host country which leads to the possibility that the refugee participant might view the researcher as “powerful.” Undertaking an interview for research goals might remind the participant of interrogations or past experiences of intimidation in a highly political rigid regime (Robila & Akinsulure-Smith, Citation2012).

The role of interpreters is also important as researchers commonly collaborate with interpreters in refugee research studies and can cause challenges in the research process. An interpreter should be able to be familiar with the cultural and social context of the refugee and building trust on the one hand, but also be aware of the research goals and making sure objectivity is held. Vara and Patel (Citation2012) emphasize the importance of investing time in updating the interpreter with the research goals. Interpreters might have great knowledge on contextual factors that researchers might be unaware of.

Another important aspect in the relationship between the researcher and the participant is the informed consent. Researchers must be aware that some refugees might be frightened for the consequences when “not” signing the consent due to past experiences (Pernice, Citation1994). Lastly, the researcher must be aware that other incentives, such as a financial incentive, might play a role in participating in research (Sulaiman-Hill & Thompson, Citation2011). Ellis et al. (Citation2007) suggest to expand the informed consent by involving important community members or leaders to sign the informed consent. These community members can emphasize that there is no relation for instance between immigration status and participation in the study.

To conclude, challenges faced by the individual researcher that concern the participants include: mistrust, interpreters, informed consent, and other incentives for participating in research.

Mesosystem: the role of the team

At the third level of our conceptual framework, we refer to all the factors and mechanisms that influence the researcher and the research design at team level. For example, treatment fidelity is essential in order to increase both internal and external validity of the research study. Carlsson et al. (Citation2014) explain that standardized treatments often mismatch the complex system of problems refugees face. Several studies discuss issues regarding adherence to the research protocol within this population (Baird et al., Citation2017; Carlsson et al., Citation2014; Goodkind et al., Citation2017). For example, Baird et al. (Citation2017) describes that many adjustments were needed during their research process, limiting the feasibility of future replication studies. Furthermore, they state that they were uncertain how the refugee participants understood questionnaires, such as Likert-scales. Such issues emphasize problems with generalizability of the results.

In conclusion, important pitfalls we have encountered on this level include treatment fidelity, adherence to the research protocol, and generalizability of results.

Exosystem: the role of institutional factors

At the fourth level, we describe challenges at the level of organizational and social systems. One important challenge is the lack of resources in research amongst refugees. Organizations and institutions working with refugees are often underfunded, which makes research a second priority (Carlsson et al., Citation2014). This might be due to the fact that in general, mental health care for refugees is more time consuming because of language barriers, cultural differences, and the interplay of mental health and social problems. This makes it difficult to apply cost-effective mental health interventions.

Although good research ethics are most important in conducting research among refugees, (Eggerth & Flynn, Citation2010), obtaining ethical permission for refugee research can be quite challenging. In their paper, Eggerth and Flynn (Citation2010) describe a couple of important ethical decisions to take into account when conducting research. Interestingly, they highlight the importance of recognizing the importance of the community context in ethical decision making. As an example, it is suggested to consider whether a research proposal is relevant for the community rather than filing literature and theoretical gaps only.

Other issues reflect methodological difficulties to meet scientific standards when conducting mental health research in refugee populations. For example, there are issues concerning sampling. Refugees in governmental care are on the move, they go from institution to institution depending on their asylum procedure status. This makes it difficult to trace back people after an initial meeting and perform longitudinal measurements (Pernice, Citation1994). Often, recruitment relies on key-informants who will promote the research among their peers. This can easily lead to a biased sample. However, as census data is not available, it is complex to assess whether a representative sample has been selected (Ellis et al., Citation2007; Goodkind et al., Citation2017; Pernice, Citation1994; Rousseau, Citation1993; Sulaiman-Hill & Thompson, Citation2011).

To conclude, institutional factors we encounter when conducting refugee mental health research include lack of resources, sampling difficulties, scientific standards, and ethical permission.

Macrosystem: the role of the society and the political climate

In our ecological model, we interpreted the level of the macrosystem as the societal norms and beliefs from the broader environment of the researcher. Working in the Netherlands, we used the Dutch context as our starting point. Carlsson et al. (Citation2014) mentions the political climate in a country could impact research with refugees. Norms and beliefs can result in changes in policies regarding the resources and care for refugees, for instance regarding accommodation of refugees, waiting time for juridical decisions, fees for medical consultations, funds for research and (governmental) grants for clinical departments. These policy decisions, in turn, impact the possibilities to conduct research.

Another societal factor includes ethical principles for conducting research. Notably, the Declaration of Helsinki of the World Medical Association, the most important declaration regarding ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects, does not include an addendum to address specific issues concerning research among refugee populations (Leaning, Citation2001). This makes it difficult to create awareness among researchers regarding the specific challenges which are linked with conducting research with refugees, to address these challenges, and to obtain meaningful informed consent.

Lastly, Ellis et al. (Citation2007) points out the risk of depicting refugees as “traumatized victims.” On the one hand, describing refugees as “traumatized victims” could be helpful for both the researcher (in order to get access to funding) as well as the refugee to gain extra resources that might help (e.g., more access to important health services). But on the other hand, this downplays the fact that refugees can be resilient and have strengths that are not shown in this way (Apfel & Simon, Citation1996). By presenting refugees as “victims” in research studies, the overall view of a refugee might become more negative and more pathologized then necessary.

In conclusion, we face pitfalls in refugee mental health research linked to societal norms and beliefs, such as changing political decisions, changes in policies, limited specific ethical principles for conducting research with refugees, and media attention affecting the public opinion. The political climate, ethical principles, and depicting a refugee as a traumatized victim were the most important pitfalls we have encountered at this level.

Discussion

In this clinical practice paper, we have conceptualized the challenges of refugee mental health research in an ecological model, based on the social-ecological framework (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1979, Citation1986, Citation1995). We presented pitfalls that can play a role in refugee research at different levels. So far, challenges in refugee research have been mainly discussed in the discussion sections of individual research papers, and reflections of specific challenges have been discussed in review papers. As far as we know there was no clear integration of these challenges and their association with common study limitations, and no conceptual model of these challenges. Therefore, the main aim of this paper was to provide the challenges in refugee research, which might contribute to a better understanding of the difficulties that researchers are facing in this field.

Summary of the results and addition of our own experiences

At the first level, the level of the individual researcher, we indicated that challenges when conducting refugee research include over-identification, and prejudices and attitudes, and might create high personal ethical standards that are difficult to handle in a field full of social inequality. Moreover, the individual researcher might choose measurements that do not fit the research populations and even. Even when the instrument is validated across different linguistic groups, it often remains unclear whether this questionnaire will address the most important psychological symptoms experienced by the participant (De Jong, Citation2006; Kaiser et al., Citation2015; Wind et al., Citation2017). In addition, from our own clinical and research practice, we think that processes of (counter-)transference may often take place at this level. Psychological transference refers to the unspoken wishes, fears and emotions from the patient, in this case the refugee, that are projected on the therapist, in this case the researcher. Counter-transference refers to the unspoken reactions and emotions of the researcher that are projected on the participating refugee (Gabbard, Citation2014). It is possible that (counter-)transference could result in a wish of the researcher to protect the refugee. Furthermore, these processes may complicate research as the researcher might wish to be more distant from the project. For the researcher, it can be difficult to face and handle the complex, and at times intense emotions, that are linked to working with refugees. Even feelings of demoralization may arise (Kramer et al., Citation2015).

At the second level (microsystem), we focused on the role of the participating refugee, and how this might affect the individual researcher. The relationship between the researcher and the refugee might be linked to concepts such as difficulties obtaining meaningful informed consent, and facing current daily stressors whilst conducting research. Also, there might be difficulties with using interpreters and a problem with the incentive to participate in research. Trust is a key area of concern when working with refugees (Hynes, Citation2003). As stated by Daniel and Knudsen (Citation1995): “the refugee mistrusts and is mistrusted”. During pre-migration, refugees often face several problems that might affect their trust (Ní Raghallaigh, Citation2014). Most refugees flee their country as a result of conflict, persecution, or violations of human rights, such as torture (UNHCR, Citation2019). They leave behind their homes, loved ones and familiar surroundings because they do not trust their lives and their environment. Moreover, they might be faced with human traffickers. As a result of these experiences, mistrusting others can be developed as a coping- or survival strategy (Ní Raghallaigh, Citation2014). During the post-migration phase, this mistrust can be encountered when conducting research with refugees. As part of the APA Ethics code (Knapp & VandeCreek, Citation2003) participants in human research have the right to informed consent. Informed consent is the procedure of clearly informing participants regarding the methods, aims, benefits and risks of research in order to correctly inform, and thereby protect, participants. The Western informed consent procedure assumes that participants understand the offered information well and are able to accept this information. However, in practice we have noticed that refugee populations often have difficulties reading this information as a result of language barriers or illiteracy, which might make it difficult to make a well-informed decision on participating in research (Czymoniewicz-Klippel et al., Citation2010). Moreover, refugees are often unfamiliar with Western research methods. The current informed consent procedure is therefore often described as Western and culturally bound (Block et al., Citation2013; Mackenzie et al., Citation2007). As suggested by Mackenzie and colleagues (Citation2007; pp. 306): “Not only are such procedures often culturally inappropriate, in refugee settings they may expose participants to increased risk, arouse mistrust and suspicion of researchers, and undermine the possibilities for negotiating genuine ethical engagement with participants.” From our own experiences we would like to add the challenge daily stressors such as financial problems, language barriers, forced relocations and a stressful asylum procedure. These might complicate treatment- and research procedures (Lahuis et al., Citation2019). We have often worked with families who sometimes face daily affairs that take up time, such as compulsory registrations, having to bring children to school, and meetings with institutions such as school, the council for refugees, and immigration and naturalization services. As a result of the aforementioned issues, it can be difficult to prioritize research, recruitment and inclusion (Fazel & Betancourt, Citation2018).

At the third level (mesosystem), the level of the team working with the individual researcher, issues such as difficulties in treatment fidelity, adherence to the protocol were presented. In research as well as in clinical practice, problems with adhering to the treatment protocol, better known as “therapist drift,” are documented. Most central are the beliefs that the therapeutic alliance “will do the work,” the patient is “too complex” for the standard treatment protocol, black-white thinking, and magical thinking (Waller, Citation2009). However, this could diminish the generalizability of the results. We think that emotional processes experienced by the therapist, including (counter-)transference and overinvolvement, may play a role in treatment fidelity (Waller, Citation2009). One study showed that counselors working with refugees experience high levels of isolation and impotence as a result of (counter-)transference (Century et al., Citation2007). In the treatment of refugees in particular, processes of overinvolvement and overidentification have been reported by therapists (Mirdal et al., Citation2012).

The fourth level (exosystem) focused on institutional factors. Issues concerning lack of resources (e.g. time and financial strains), difficulties adhering to current scientific standards, including sample difficulties and getting ethical permission, were raised. Typically, first a research topic is identified, the proposal is then written and submitted for review. When the proposal and informed consent form have been approved, the research can start according exactly to the project plan. However, conducting research in a refugee population is a process where many unforeseen challenges arise along the way. Informed consent forms sometimes need to be adjusted, the sampling methods may not work, adherence to the original research protocol can be found difficult because of the social problems. However, if you describe these challenges already beforehand in the proposal, it is more difficult to get the permission and start the project. This creates a dilemma for the individual researcher.

Lastly, the fifth level (macrosystem), included political climate and societal norms and beliefs. Challenges presented at this level included continuous changes in political decisions and the political climate regarding factors such as the asylum procedure, resources and care for refugees. Also, the role of media attention and ethical principles was described. Lastly, the pitfall of depicting refugees as a “traumatized victim” is discussed. Although challenges faced at this level might directly impact the other levels of the ecological model, this level, including political decision, can hardly be influenced by the individual researcher. Changes in this policy lead to changes in the stability of the study population. For example, a study on post-migration factors emphasized that certain factors that impact refugee research are difficult to address by an individual researcher. These factors include, among others: high mobility of refugees, a trend of a more restrictive asylum policy, mandatory detentions and temporary statuses (Li et al., Citation2016). From our own experiences, we have seen that media attention also can play an important role in enhancing the visibility of the stressors of refugee populations in society, and sometimes can cause the public opinion to change swiftly. For example, the media attention for the adverse situation of two Armenian children in the Netherlands seems to have directly facilitated the introduction of the definite form of the aforementioned Regulation for Long-term Resident Children. This shows the power of public opinions and media on policy, and indirectly on the course of research.

Research example

The different levels presented in our conceptual framework can mutually affect each other, which in turn may result in several study limitations. This is illustrated in the following case example, encountered in a treatment intervention study of Djelantik et al. (Citation2020):

In this study, we aimed to investigate the associations between post-migration stressors and symptom reduction and non-completion in a treatment for traumatic grief among refugees. At times, due to a negative asylum decision, a refugee can lose their house and financial support while taking part in a treatment study. This decision, made at the level of societal norms and political climate (macrosystem) will create difficulties in several other levels of the model. At the institutional level (exosystem), this will result in a financial challenge because the costs of the treatment are not fully funded anymore. At the level of the mesosystem, clinicians may identify with the social problems of the refugee, resulting in more time spent on social work in the treatment hours, for example arranging refunds, travel costs or emergency housing. Because the clinician spends time on arranging solutions for these social problems, they have more difficulties to follow a strict protocol. Eventually, this could result in a drop-out of treatment and the research study. Furthermore, because the research program may not offer a solution for the social problems, the refugee (micro level) might feel mistrust and the informed consent may be interpreted incorrectly. The refugee may sign informed consent because they hope it will help him or her with their social problems. The clinician, the institution and the refugee might present the dilemmas they are facing to the researcher. For the researcher, this may result in challenges regarding inclusion, ethical considerations and doubts whether the participant is too vulnerable to take part in research, which can ultimately affect the research process.

This example illustrates clearly that the researcher faces challenges at all different levels presented within the model. The etiology of problems such as a high drop-out rate, low protocol adherence and difficulties concerning obtaining meaningful informed consent can be best addressed by improving collaboration between the different levels. In order to provide good collaboration between each level, a possible suggestion is to introduce regular meetings within the research institute to establish interrelations between the researcher, the refugee, the clinical team and the institution.

Possible solutions

More awareness of the challenges within the institution might help to ensure that there is a clear understanding of the possible pitfalls in refugee research. Furthermore, it is important to increase awareness regarding the possible effect of (counter-)transference and low treatment fidelity on research. For instance, providing training or regular information meetings to the therapists and colleagues involved in the research project might help in order to raise awareness of the emotional and cognitive processes that are involved in treatment. Furthermore, transparency is the key to conduct ethical sound refugee research. Because of the challenges faced by the individual researcher, it can be very difficult to follow your own pre-designed research protocol. Therefore, it is of importance to discuss and report on methodological choices and challenges beforehand and also during the research process.

Building trust seems highly important. Thorough information about the community’s values, beliefs, practical concerns and social context is essential in order to gain mutual trust between the participant and the researcher (Bailes et al., Citation2006). Bailes et al. (Citation2006) state that including “cultural advisors” and communicating the findings of the study to the community can be very important. De Haene et al. (Citation2010) describe that listening to concerns and questions of the participants, giving words to underlying fears or distrust was effective in establishing trust in the relationship.

Lastly, we indicated that conducting research in resettled refugee populations can be a complicated process. Dealing with several factors that play a role in conducting research, such as linguistic, transference and social problems, can require more time and effort, compared to mental health research with a more Western population. Therefore, we urge that these specific challenges will be taken into account while funding and planning research projects focused on refugees.

Limitations

Our results need to be interpreted in the light of some important limitations. First, we are all researchers conducting research in the same country, within the same organization. Challenges we face could be linked to this context. Therefore, we cannot be sure that our findings are generalizable to a broader context. However, as we indicated in the model and the presented literature, we assume that the challenges we face are experienced in a broader context. Secondly, this opinion paper is not a comprehensive review of the scientific literature. Our goal was to provide an overview of the challenges we face in our daily work, and how these challenges are connected to each other. This paper can therefore be observed as a starting point for open discussion and awareness, which eventually might help to find solutions to overcome these challenges.

Conclusions

In this paper we have provided an overview of the most important challenges in refugee mental health research. Study limitations and challenges such as high a drop-out rate, the treatment fidelity, recruitment difficulties and financial limitations, are affected by different processes and factors at several levels. To find ways of improving the quality of refugee studies, specific targets on specific levels should be addressed in a wider perspective.

Author contributions

MD, CE, AL and NM were responsible for the design of the study. MD, CE, AL and NM were responsible for the systematic review, data-analysis, and interpretation of the data. MD, CE, AL and NM wrote the drafts of the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article [and/or] its supplementary materials.

References

- Adibe, B. (2021). COVID-19 and clinician wellbeing: Challenges and opportunities. The Lancet. Public Health, 6(3), e141–e142. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00028-1

- Apfel, R. J., & Simon, B. (1996). Psychosocial interventions for children of war: The value of a model of resiliency. Medicine and Global Survival, 3(1), 1–16.

- Bailes, M. J., Minas, I. H., & Klimidis, S. (2006). Mental health research, ethics and multiculturalism. Monash Bioethics Review, 25(1), S53–S63. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03351447

- Baird, M., Bimali, M., Cott, A., Brimacombe, M., Ruhland-Petty, T., & Daley, C. (2017). Methodological challenges in conducting research with refugee women. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 38(4), 344–351.

- Block, K., Warr, D., Gibbs, L., & Riggs, E. (2013). Addressing ethical and methodological challenges in research with refugee-background young people: Reflections from the field. Journal of Refugee Studies, 26(1), 69–87. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fes002

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development. Harvard University Press.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1986). Ecology of the family as a context for human development: Research perspectives. Developmental Psychology, 22(6), 723–742. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.22.6.723

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1995). Developmental ecology through space and time: A future perspective. In P. Moen, G. H. Elder, Jr., & K. Lüscher (Eds.), Examining lives in context: Perspectives on the ecology of human development (pp. 619–647). American Psychological Association.

- Carlsson, J., Sonne, C., & Silove, D. (2014). From pioneers to scientists: Challenges in establishing evidence-gathering models in torture and trauma mental health services for refugees. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 202(9), 630–637. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000000175

- Century, G., Leavey, G., & Payne, H. (2007). The experience of working with refugees: Counsellors in primary care. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 35(1), 23–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069880601106765

- Czymoniewicz-Klippel, M. T., Brijnath, B., & Crockett, B. (2010). Ethics and the promotion of inclusiveness within qualitative research: Case examples from Asia and the Pacific. Qualitative Inquiry, 16(5), 332–341. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800409358872

- Daniel, E. V., & Knudsen, J. C. (Eds.). (1995). Mistrusting refugees. (p. 1). University of California Press.

- De Haene, L., Grietens, H., & Verschueren, K. (2010). Holding harm: Narrative methods in mental health research on refugee trauma. Qualitative Health Research, 20(12), 1664–1676. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732310376521

- De Jong, J. (2006). (Ed.). Trauma, war, and violence: Public mental health in socio-cultural context. Springer Science & Business Media.

- Djelantik, A. A. A. M. J., De Heus, A., Kuiper, D., Kleber, R. J., Boelen, P. A., & Smid, G. E. (2020). Post-migration stressors and their association with symptom reduction and non-completion during treatment for traumatic grief in refugees. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 407.

- Eggerth, D. E., & Flynn, M. A. (2010). When the third world comes to the first: Ethical considerations when working with hispanic immigrants. Ethics & Behavior, 20(3–4), 229–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508421003798968

- Ellis, B. H., Kia-Keating, M., Yusuf, S. A., Lincoln, A., & Nur, A. (2007). Ethical research in refugee communities and the use of community participatory methods. Transcultural Psychiatry, 44(3), 459–481. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461507081642

- Fazel, M., & Betancourt, T. S. (2018). Preventive mental health interventions for refugee children and adolescents in high-income settings. The Lancet. Child & Adolescent Health, 2(2), 121–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(17)30147-5

- Gabbard, G. O. (2014). Psychodynamic psychiatry in clinical practice. American Psychiatric Pub.

- Goodkind, J. R., Amer, S., Christian, C., Hess, J. M., Bybee, D., Isakson, B. L., Baca, B., Ndayisenga, M., Greene, R. N., & Shantzek, C. (2017). Challenges and innovations in a community-based participatory randomized controlled trial. Health Education & Behavior: The Official Publication of the Society for Public Health Education, 44(1), 123–130. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198116639243

- Hayes, S. W. (2021). Commentary: Deepening understanding of refugee children and adolescents using Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological and PPCT models - A Commentary on Arakelyan and Ager (2020). Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 62(5), 510–513. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13403

- Hugman, R., Bartolomei, L., & Pittaway, E. (2011). Human agency and the meaning of informed consent: Reflections on research with refugees. Journal of Refugee Studies, 24(4), 655–671. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fer024

- Hynes, T. (2003). New issues in refugee research. The issue of ‘trust’or ‘mistrust’in research with refugees: choices, caveats and considerations for researchers. Evaluation and Policy Analysis Unit, The United Nations Refugee Agency.

- Jacobsen, K., & Landau, L. B. (2003). The dual imperative in refugee research: some methodological and ethical considerations in social science research on forced migration. Disasters, 27(3), 185–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-7717.00228

- Kaiser, B. N., Haroz, E. E., Kohrt, B. A., Bolton, P. A., Bass, J. K., & Hinton, D. E. (2015). “Thinking too much”: A systematic review of a common idiom of distress. Social Science & Medicine, 147, 170–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.10.044

- Knapp, S., & VandeCreek, L. (2003). An overview of the major changes in the 2002 APA Ethics Code. Professional Psychology, Research and Practice, 34(3), 301–308. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.34.3.301

- Kramer, S., Hoogsteder, M. H H., Olsman, E., & van Willigen, L. (2015). Handreiking ethische dilemma’s in de GGZ voor asielzoekers.

- Lahuis, A. M., Scholte, W. F., Aarts, R., & Kleber, R. J. (2019). Undocumented asylum seekers with posttraumatic stress disorder in the Netherlands. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 10(1), 1605281. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2019.1605281

- Leaning, J. (2001). Ethics of research in refugee populations. Lancet (London, England), 357(9266), 1432–1433.

- Li, S. S., Liddell, B. J., & Nickerson, A. (2016). The relationship between post-migration stress and psychological disorders in refugees and asylum seekers. Current Psychiatry Reports, 18(9), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-016-0723-0

- Mackenzie, C., McDowell, C., & Pittaway, E. (2007). Beyond ‘do no harm’: The challenge of constructing ethical relationships in refugee research. Journal of Refugee Studies, 20(2), 299–319. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fem008

- Mirdal, G. M., Ryding, E., & Essendrop Sondej, M. (2012). Traumatized refugees, their therapists, and their interpreters: Three perspectives on psychological treatment. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 85(4), 436–455. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8341.2011.02036.x

- Ní Raghallaigh, M. (2014). The causes of mistrust amongst asylum seekers and refugees: Insights from research with unaccompanied asylum-seeking minors living in the Republic of Ireland. Journal of Refugee Studies, 27(1), 82–100.

- Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z., & Elmagarmid, A. (2016). Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 5(1), 210.

- Pernice, R. (1994). Methodological issues in research with refugees and immigrants. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 25(3), 207–213. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.25.3.207

- Robila, M., & Akinsulure-Smith, A. M. (2012). Psychological ethics and immigration. In M. M. Leach, M. J. Stevens, G. Lindsay, A. Ferrero, & Y. Korkut (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of international psychological ethics (pp. 191–200). Oxford University Press.

- Rousseau, C. (1993). The place of the unexpressed: Ethics and methodology for research with refugee children. Canada's Mental Health, 41(4), 12–16.

- Slobodin, O., & de Jong, J. T. V. M. (2015). Mental health interventions for traumatized asylum seekers and refugees: What do we know about their efficacy? International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 61(1), 17–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764014535752

- Sulaiman-Hill, C. M. R., & Thompson, S. C. (2011). Sampling challenges in a study examining refugee resettlement. BMC International Health and Human Rights, 11(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-698X-11-2

- UNHCR (2019). Global trends: Forced migration. https://www.unhcr.org/statistics/unhcrstats/5ee200e37/unhcr-global-trends-2019.html

- Vara, R., & Patel, N. (2012). Working with interpreters in qualitative psychological research: Methodological and ethical issues. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 9(1), 75–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2012.630830

- Waller, G. (2009). Evidence-based treatment and therapist drift. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 47(2), 119–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2008.10.018

- WHO (2014). WHO handbook for guideline development. World Health Organization.

- Wind, T. R., van der Aa, N., de la Rie, S., & Knipscheer, J. (2017). The assessment of psychopathology among traumatized refugees: measurement invariance of the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire and the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 across five linguistic groups. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 8(sup2), 1321357. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2017.1321357