Abstract

Syrian adolescent refugees are one of the largest forced displaced populations in the world. Displaced adolescents experience significant stressors on their mental health, including high poverty and severely limited access to mental health services. Studies show that game-based learning interventions offer the potential for increasing access to mental health supports. We employed a mixed-method pilot and feasibility study to explore how the Happy Helping Hand (HH) game app contributed to improved well-being and emotional problem-solving skills in displaced Syrian adolescents in Lebanon. A 5-week, 10-session digital learning HH psychosocial program was administered by teachers. Adolescent and teacher focus groups were used to assess how emotional problem-solving skills were applied in-depth. A single group pre-post design measured well-being using the World Health Organization’s Well-Being Index (WHO-5). Thematic analysis was used for qualitative analysis. Descriptive and bivariate t-tests were used for quantitative analyses. Qualitatively, adolescents´ demonstrated increased emotional problem-solving skills and well-being, and attributed the changes to the usefulness of the app. Quantitative findings show well-being significantly increased at post-test compared to pretest. The study supports the use of e-health and role-playing games for Syrian adolescents. Future research should examine an up-scaled implementation of the app with displaced adolescents.

Introduction

The ongoing war in Syria has lasted for more than a decade and subsequent displacement has had a profoundly negative effect on Syrians’ mental well-being (Hassan et al., Citation2015). Psychosocial support interventions have been found to improve emotional problem-solving skills and well-being among adolescent refugees living in fragile contexts (Bryant et al., Citation2022; Schuler & Raknes, Citation2022). However many living under conditions of poverty have very limited access to psychosocial supports (Patel et al., Citation2018; Schuler & Raknes, Citation2022). Universal intervention and prevention efforts that enable psychosocial support in the youth’s surrounding environment, especially during post-migration periods could help reduce mental distress and improve psychosocial wellbeing (Dangmann, Citation2022). Given the underlying systemic barriers that prevent access to health and mental health care, education, and sustainable employment facing refugees in Lebanon (DeJong et al., Citation2017), digital interventions accessible both within and outside of school and health environments could be an effective way to lower costs and obstacles to care and offer psychosocial assistance, particularly in contexts where there are high levels of traumatic stress, such as among children who are refugees (Mancini, Citation2020).

Approximately 1.5 million people from Syria are currently displaced in Lebanon, over half of whom are adolescents (World Health Organization, Citation2018a, Citation2022). The Bekaa Valley is an agricultural region in the east of the country, bordering Syria. Due to Lebanon’s prohibition of formal refugee camps, most displaced Syrians lived in informal settlements as they can’t afford regular housing. These unofficial settlements lack official humanitarian support, leaving residents without assured access to stable housing, healthy food, safe water, education, healthcare, and protection. This exclusion has been linked to mental health issues among refugee youth (Habib et al., Citation2020; UNICEF, Citation2014). Previous research has shown that refugees often have settled in areas where there were high preexisting poverty rates with limited opportunities for education, employment, healthcare, and mental health care (DeJong et al., Citation2017; World Health Organization, Citation2018a, Citation2022). As a result of these limitations, Syrian refugee adolescents in Lebanon are at risk for increased stress and subsequent consequences to their mental health and wellbeing (Kazour et al., Citation2017; Sender et al., Citation2023). In addition to economic challenges, substandard housing with overcrowding, and post-migration stress resulting from forced displacement, adolescent refugees face the added social challenges related to not feeling safe in their community, having more social constraints and experiencing social isolation (DeJong et al., Citation2017; Sender et al., Citation2023; Syam et al., Citation2019). As a result, many adolescent refugees in such settings face higher rates of post-traumatic stress (e.g., over 45% have developed post-traumatic stress disorder) (Khamis, Citation2019), anxiety, and depression (Reed et al., Citation2012; Sim et al., Citation2019).

The term “psychosocial” integrates individual psychological aspects with the broader social environment to understand human behavior. Critics (Bracken et al., Citation1997; Bracken et al., Citation1995; Jost, Citation2024) have highlighted issues such as the medicalization of social problems, where focusing on individual mental health might ignore underlying social and political causes. They also criticize the cultural insensitivity of applying Western mental health models universally, potentially disregarding diverse cultural understandings of well-being. Additionally, there’s concern that an overemphasis on individual therapy overlooks the benefits of community and social support, and that individualized approaches may pathologize normal reactions to adversity, leading to unnecessary medicalization. These critiques call for a nuanced approach that balances individual and social factors in addressing human suffering, emphasizing the need for continuous dialogue and reflection in interventions for social and emotional support across cultures and economic divides.

Qualitative research conducted among Syrian refugees in Lebanon provides in-depth information on the major challenges affecting adolescent mental health. For example, in a community mapping and photo elicitation study of n = 118 10–14 year-olds, Syrian refugees described their psychological distress, inclusive of sadness, depression, crying and fear (DeJong et al., Citation2017). The adolescents currently addressed their mental health by expressing their emotions physically (by crying, taking walks), connecting with peers (e.g., seeing friends, going to school), and engaging in independent activities such as reading books or participating in religious activities (DeJong et al., Citation2017). Perceptions of n = 13, 10–14-year-old Lebanese and Syrian adolescents and parents recruited from community centers in northern Lebanon show that sources of stress stem from challenges related to interpersonal violence and abuse, neglect and emotional abuse from parents, tension between Lebanese and Syrian youth (e.g., emotional abuse, bullying), adolescent substance use, poverty, and lack of mental health literacy, awareness and services (Brown et al., Citation2020). Major stressors are further highlighted in interviews with n = 39 Syrian parents and n = 15 children recruited from a humanitarian organization in Lebanon who described the parenting challenges associated with economic hardship and how they can contribute to parenting stress and strained parent-child interactions (Sim et al., Citation2018), factors that can also negatively affect adolescent mental health and wellbeing (Sim et al., Citation2018). Families were also challenged with social constraints, such that they perceived others in their community to be already inundated with their own stressors, and that lack of social support from extended family and lack of trust in the community were added stressors (Sim et al., Citation2018). Qualitative research also provides some in-depth understanding of differences in experiences between boys and girls in this context, indicating perceptions of more perceived social constraints, social limitations, and fears of safety for girls (DeJong et al., Citation2017).

Existing research on psychosocial support interventions among Syrian refugee adolescents in Lebanon is highly limited. In a mixed-methods study of n = 104 refugees living in Central Bequa Lebanon participating in The Happy Helping Hand (HH), a cognitive behavioral digital game facilitated by teachers, was found to improve adolescent depressive symptoms and well-being in both virtual and online formats (Schuler & Raknes, Citation2022). The HH game was found more useful when implemented by well-trained psychosocial support service (PSS) staff than by teachers in a quantitative study of the implementation of the game among Syrian adolescents in Lebanon (Townsend et al., Citation2022). Other limited research on mental health interventions in similar populations of Syrian refugees in Lebanon demonstrates how community-based mental health interventions could help improve adolescent refugee mental health. For example, a therapist-led cognitive behavioral intervention study of 13–17 year-old Syrian adolescent refugees in Lebanon found that participating in 7 weekly 60-min sessions is feasible and acceptable, may reduce depression and anxiety, and increase quality of life (Doumit et al., Citation2020). Another study found that a mental health group intervention may help to reduce anxiety and depression among Syrian adolescent refugees in Lebanon, but could be enhanced by including community members rather than a therapist to deliver the intervention and by incorporating context-specific examples into the curriculum to enhance the cultural relevance of the intervention (Brown et al., Citation2020).

Digital technology has opened up distinct possibilities for mental health initiatives, particularly in delivering mental health support to marginalized communities (Fairburn & Patel, Citation2017). Phones are frequently used among Syrian refugees in Lebanon and play an important role in reviving, maintaining, and leveraging social capital (Diab, Citation2022; Göransson et al., Citation2020; Zijlstra & Liempt, Citation2017). A rapid review of sixteen studies found that digital health technologies have a significant role to play in the mental healthcare for immigrants and refugees by providing mental healthcare in a time-saving and cost-effective way and reducing major stigma and mental health literacy barriers (Liem et al., Citation2021). A study of Syrian refugees in Turkey found that of the subjects that reported a need for psychiatrist, 45.7 percent would accept being treated with telepsychiatry (Jefee-Bahloul et al., Citation2014). In a study of adult Syrian refugees in Germany, Sweden, and Egypt, the use of digital technologies were found to be used among the majority of Syrian refugees (Burchert et al., Citation2018).

Among Syrian refugees, stigma associated with mental health difficulties, in addition to poverty, was found to constitute a major barrier in seeking help from mental health providers (Al Laham et al., Citation2020). Stigma depends largely on people’s awareness about mental health, or health literacy (World Health Organization, Citation2018b). Health literacy methods applied in community and school settings can promote both individual health and community empowerment to reduce social health inequalities (Abel & Benkert, Citation2022; Queroue et al., Citation2021). Promoting health literacy therefore involves the provision of accessible, understandable, and culturally sensitive health information and is intended to enable people to seek help when encountering health-related problems.

Schools play a central role in increasing health literacy and the provision of PSS initiatives for adolescents. Schools restore normalcy and continuity where PSS initiatives can be provided in a safe and child friendly space, without the social stigma associated with mental health. Teaching staff play a central role in school-based PSS initiatives (Mattingly, Citation2017). Social and emotional learning (SEL), the process of acquiring emotional management skills, interpersonal competencies, and life skills, contributes to psychosocial well-being through the development of five key competencies: self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship-building skills, and responsible decision-making (INEE, Citation2016).

The purpose of this study was to examine the utility of the digital psychosocial support (PSS) HH game to improve emotional problem-solving skills and well-being in displaced Syrian adolescents in Lebanon when used in a school-based blended learning PSS program. This is the first known study where a digitalized CBT (cognitive behavioral training) game has been used as a basis for SEL in a school based, universal program among adolescent Syrian refugees living in this context. Specifically, our objective was to examine the utility of the HH game app in improving coping and overall well-being among displaced Syrian adolescents in Lebanon. On the foundation of the master thesis of Al-Khayatm (Citation2021), this study examined whether this cognitive behavioral digital game induced tangible behavioral changes in real-world situations when used in such a setting.

Methods

Study population and data collection

A mixed-method approach was applied to contrast, triangulate, and interpret the results from focus groups with the quantitative results from the pre- and post-tests. The study was ongoing from October to November 2020. A single group pretest-post-test design was used with N = 104 adolescents (n = 56 girls; n = 48 boys) to assess changes in psychological well-being before and after engagement with the HH app intervention. Teacher and adolescent views on the feasibility and impact of a program is known as a central facilitator or barrier for further implementation of a SEL-program. Therefore, both teacher and student perspectives were included to assess feasibility and impact.

The program was implemented by Multi Aid Programs (MAPS), a refugee-led NGO that supports community development programming in eastern Lebanon. The convenience sample included adolescents 10–16 years-old recruited from non-formal education through MAPS in Bekaa or Arsal. A purposive sample of 10 teachers (N = 10; 5 women and 5 men) was selected from the pool of MAPS teachers based on their availability to facilitate the intervention for adolescents. All students who were at the education centers during the time period when this program was implemented, regardless of their mental health, literacy level, digital skills, or access to digital devices at home were eligible to participate. There were no other exclusion criteria for adolescent participation. Eligibility criteria for teachers included having the interest and availability to teach SEL and having approval from MAPS administration. The teachers received training in the form of a digital half-day workshop and had access to the HH program manual (Raknes, Citation2022) prior to the first HH session with adolescents. The intervention was delivered within normal educational programming. No additional payments or incentives were provided for study participation.

The participating adolescents were displaced due to the war in Syria. Information about the participants´ living conditions or what specific losses and traumas they have been exposed to was not collected in this study, but it is widely recognized that Syrian refugees have faced elevated levels of traumatic incidents both before and throughout their migration journey, as well as afterwards (Mancini, Citation2020). For people in Lebanon the situation worsened due to Lebanon’s economic collapse that started in 2019, the aftermath of the Port of Beirut explosion in July 2020, and during Covid-19 (Brun et al., Citation2021; The World Bank, Citation2021).

Intervention

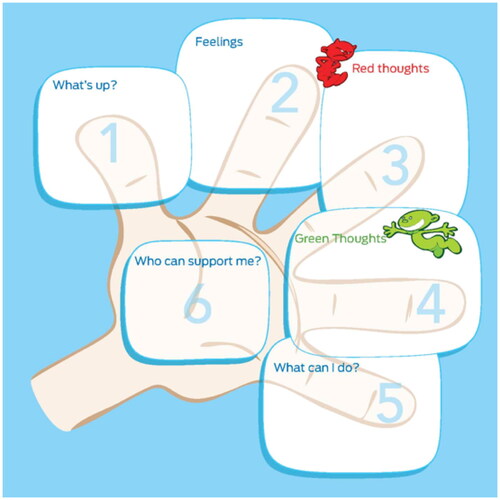

The HH (اليد المساعدة in Arabic) is a digital SEL application (app). The Arabic version of the HH digital game is an app that is free to download on phones and tablets. It was developed by Dr. Solfrid Raknes, and the Norwegian tech company Attensi, funded by Innovation Norway. To avoid cultural stereotyping (Kerbage et al., Citation2020), the intervention was developed in collaboration with members of the Syrian refugee community who were directly involved in administering the program, debriefing during and after, and providing in-depth qualitative feedback reflecting their contributions and perceptions of their experiences. Implementation in Lebanon was supported by The Norwegian Research Council and Innovation Norway. The HH game draws its foundation from analog cognitive self-help resources (Raknes, Citation2010), which are extensively adopted in Scandinavia (Rasmussen & Neumer, Citation2020). This material has been shown to effectively diminish levels of anxiety and depression in adolescents when integrated into school-based programs (Haugland et al., Citation2020). In the HH digital game, the player helps virtual friends to master challenges, such as fear of giving presentations, dealing with criticism, suicidal thoughts, and bad memories. The game guides players through realistic scenarios to promote positive decision-making, encourage discussions about feelings and thoughts, and highlight the importance of seeking help when necessary. The HH Problem Solving System is used to teach adolescents the basic CBT principles. This framework involves problem identification, identifying feelings, identifying unhelpful (“red”) thoughts, cultivating helpful (“green”) thoughts, exploring actions and strategies, and identifying people who can provide support (see ). Based on the HH manual, each scenario in the game is the basis for one SEL-session (Raknes, Citation2022). describes the programs´ themes and learning goals, session by session.

Figure 1. The Helping Hand problem solving system. Note. In the The Helping Hand Problem Solving System the player identifies the problem, names feeling(s) and unhelpful (“red”) thoughts, looks for helpful (“green”) thoughts, explores helpful actions and strategies, and identifies people who can support.

Table 1. Ten Helping Hand scenarios and associated session learning goals.

The HH includes 10 sessions, with 1 scenario covered per session. Each scenario takes about 15 min to play. Following play, each session included group processing and discussions, lasting approximately 60 total min. All 10 sessions in the HH program were provided over a period of five weeks, two sessions weekly, given on the same days of the week for practical reasons. Five of the groups met at MAPS’ education center in Bekaa, and the other five met at MAPS´ education center in Arsal. Teachers were asked to firstly introduce the session’s theme and its relevance in daily life, then enable students to engage with the relevant scenario in the HH game, and then facilitate activities that support in-depth learning related to the session’s learning goal according to the HH manual. The teachers had 4 tablets available per group, and the adolescents typically played the game in groups of 2–5 students. Most students had access to a shared mobile device at home (e.g., one family usually shares one phone). The adolescents were able to access the game from their personal devices.

The HH app was developed from 2017 to 2020, a period when the first author of this study was based in Lebanon, supported by Innovation Norway. User involvement by Syrians in Lebanon played a central role in developing the HH (Raknes, Citation2020). Classroom votes by 90 Syrian adolescents identified preferred game scenarios, contributing to content relevance. Collaborations with Syrian adolescents, teachers, social workers, and psychologists influenced game design, including character representation, settings, and visual elements to ensure cultural and contextual resonance. Feedback sessions led to the customization of characters and the game environment, reflecting the diverse backgrounds of Lebanese and Syrian users. Language choices were informed by discussions with adolescents with Syrians, Lebanese, and Palestinian teachers in Lebanon, aiming for inclusivity among Arabic speakers, with a focus on accessible dialects for Syrian refugees. Both the first and third authors of this study lived in Lebanon during the Covid-19 lockdown, which made the intervention possible to run. The third author of this study was fluent in Arabic and assisted with digital communication and data collection.

Qualitative sample and data collection

Three focus groups were conducted one week after the adolescents and teachers had finished the five-week HH program: two youth-groups; one consisting of female youth (n = 4), one consisting of male youth (n = 6), and one group consisting of teachers (n = 5). A semi-structured focus group guide was developed for the facilitator, whereby a few predetermined questions are asked but follow-up questions were raised pragmatically. The focus groups were conducted digitally on Zoom, recorded, and lasted from 45 to 150 min. The focus groups were conducted by a member of the implementation team in Arabic. The guide for the adolescent focus groups concentrated on their interactions with the HH app, probing their emotional resilience and problem-solving abilities both before and after participating in the SEL program. The complete interview guides can be found in Appendix A. Example questions aimed at the adolescent groups included: How pertinent are the various scenarios in the app to your own life? Could you describe how you previously managed your emotions in challenging situations? How has your coping mechanism changed since using the HH app? In what ways do you assist friends and family in handling tough situations after using the app? Has the app altered the manner in which you convey your emotions?

The guide for the teacher focus groups delved into their insights on teaching experiences related to the implementation of this SEL program, their perspectives on the health and well-being of Syrian adolescents, the program’s impact on these young people, and the feasibility of broader use of the HH app for Syrian adolescents. Example questions for the teacher discussion encompassed: "What is your interpretation of psychological well-being?" and "What factors contribute to or affect the psychological well-being of Syrian refugee adolescents? Can you give examples?" These questions were designed to gather teacher insights on the mental well-being of the adolescents, their experience with the HH app, and how effectively it engaged the students.

Quantitative sample and data collection

Questionnaires were completed anonymously online. Data on adolescents´ age, gender, and well-being were collected. Well-being was assessed by the Arabic version of the World Health Organization’s five-item Well-being Index (WHO-5). This questionnaire measured well-being using positively phrased questions, such as feeling calm, relaxed, active, vigorous, and interested in daily activities. Responses were recorded on a six-point Likert scale from 0 (At no time) to 5 (All of the time). The WHO-5 has demonstrated good reliability (α = .90) and validity, both convergent and factorial (Halliday et al., Citation2017). The Arabic version of the WHO-5 has been validated in Lebanon, showing acceptable reliability (α = .80) (Sibai et al., Citation2009).

Institutional review approval and data security

This paper reports the evaluation of a program designed to collect information about activities, characteristics, and outcomes of the HH program for quality improvement and to inform decisions about future program development and was not an active research study. All participant data have been de-identified for analysis and interpretation. Therefore, approval from an ethics committee is not needed.

Data analysis

The qualitative data was collected in Arabic, by the Arabic-speaking researcher who facilitated the interview (the third author of this paper). To avoid bias, the lead researcher and app developer (Raknes) did not participate in analysis. Written, detailed transcription summaries of each of the interviews were written in English by the same researcher. The summaries of the transcriptions were analyzed through thematic analysis, utilizing an inductive strategy to uncover key themes and topics. This involved identifying, analyzing, and reporting patterns (themes) within our data set by following a six-step method of thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). The quantitative descriptive and bivariate statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 27. Independent samples t-tests were used to examine gender differences in pre and post-test scores. Due to anonymity of data collection, one-sample t-tests were used to compare whether the sample pretest mean was significantly greater or less than the average post-test mean. Furthermore, utilizing Hedge’s g, we evaluated the effect size from pre-intervention to post-intervention assessments. This approach facilitated the quantification of alterations in adolescents’ well-being, as captured by the WHO-5 scale.

Results

Sample characteristics

Most (98%) of the adolescents participated in at least 8 of the sessions. A total of 104 youth participated at baseline (i.e., completed pretest) and n = 73 completed post-intervention assessments, yielding a response rate of 70% for the full sample, 50% for the female sample (pre n = 56, post n = 34), and 63% for males (pre n = 48, post n = 39). At baseline, adolescents were 13.38 years-old (SD = 1.14; range = 10 to 16), on average. Most of the sample was female (n = 56, 53.8%). At pretest only adolescents who had completed the focus groups and obtained parent permission participated in the groups. The lower response rate at post-test is explained by the fact that data were collected digitally from the family’s phone at home. Because post-tests were completed at home, online and there was no consequence of not completing the questionnaire, some participants did not complete the questionnaire at post-test, contributing to missing cases at this data collection period.

Qualitative results

Three primary themes emerged related to the interventions’ impact on adolescents’ emotional and social problem-solving skills, well-being, and usefulness/relevance. These themes are presented below along with sample quotes extracted from focus groups.

Problem-solving in emotional and social domains

Both educators and adolescents perceived the HH app as an instrument that enhanced problem-solving abilities in social and emotional domains and described enhanced identification and expression of feelings, self-management, decision-making, and help-seeking. The adolescents reported that the app aided them in navigating daily challenges, encouraged alternative thinking in the face of dilemmas, and that handling challenging circumstances and openly sharing emotions had become more manageable for them. Illustratively, the adolescents provided the following comments:

It has become easier to ask for help and talk with my teacher about a problem now than before.

I have started to calm myself down when a problem arises. I normally avoid exploding.

Social and emotional problem-solving skills was a consistent theme describing how the adolescents and their teachers explained what mechanisms of change they believed were crucial in the intervention.

Well-being

Following their use of the app, not only did adolescents demonstrate better problem-solving skills, but they also described improvements in well-being, positive affect, reduction of negative affect, increased self-efficacy, improved social recognition, and more optimism. Participants also described their newfound ability to differentiate between positive and negative thoughts. The following quotes shine a light on improved well-being associated with the app based on adolescent interviews:

I experienced happiness while using the app, particularly when I could positively impact the characters.

I was always scared and nervous when I had to say something in front of the class, but now, I feel less afraid. I became more confident.

I have become more confident in myself, also when it comes to talking about my feeling and my difficulties.

I can put words into my emotions now, and it became clearer which thoughts are Red and Green.

As the students learned to distinguish between “red” and “green” thoughts, it improved their ability to manage the “red” ones. This mental organization contributed to their overall well-being.

I experienced that one of my students developed a remarkable ability to support himself… After the app, he began to support himself and switch the dubious thoughts with more motivational thoughts.

After playing the app, the students started talking about their emotions and thoughts.

Usefulness and relevance of the app

Both adolescents and teachers regarded the app as exceptionally useful and relevant to the education of the specific population of displaced young people and described the value of the app as important, useful, meaningful, and easy to understand how to use. Further, the scenarios and main characters were described as engaging, easy to identify with, and relatable for their lives and struggles. The adolescents found the app to be highly captivating, largely appreciating its digital game format and the inclusion of decision-making elements within the game. One young participant articulated the game’s relevance by stating, “The different scenarios resonated with me because they mirror challenges I face in my daily life.” Additional remarks from adolescents further underscore the app’s relevance and practicality:

The HH taught me how to express myself and my feelings.

The game aims to help us deal with problems and teaches us how to find different solutions.

I learned how to deal with school problems, such as bullying and presentation anxiety.

The app facilitated discussions and expressions of opinions. The students have little experience with discussing and expressing their views. But the game gave them this role, and the students developed the ability to provide advice and participate in reflective conversations.

Quantitative results: changes in well-being

Descriptive statistics for WHO-5 raw and percent scores are provided in . WHO-5 raw scores ranged from 0 to 25 and percent scores ranged from 0 to 100 in the full sample and female subsamples at both pre and post-test. For males, WHO-5 raw scores ranged from 4 to 25 at pre and 3 to 25 at post-test. Male’s percent scores ranged from 12 to 100 at pre and 16 to 100 at post-test. In all groups, average WHO-5 scores were higher at post-test than at pretest. As shown in , females had higher average scores at pretest (pre: M = 56.71 SD = 24.79) than males (M = 53.67, SD = 22.76); however this difference was not significant (independent samples t-test p > .05). Each group had higher average scores at post-test, which were similar in the full (M = 63.23, SD = 26.06) and female (M = 66.00, SD = 27.54) samples but slightly lower among boys (M = 60.82, SD = 24.80), however, this was not significant (independent samples t-test p > .05).

Table 2. WHO-5 descriptive statistics in full and male/female subsamples M/n (SD/%)Table Footnotea.

Bivariate analysis show evidence of a statistically significant change in WHO-5 scores from baseline to post-test for the full sample (t = 2.60, p = .01; see ). Although average scores were higher at post-test for both male and female subsamples, the mean differences were not significant. Hedge’s g was used to measure the effect size from the pre- to the post-test, which allowed us to see the effect size of the WHO-5 measuring the change in adolescents’ well-being from pre- to post-intervention. There was a small to medium effect size, with a Hedge’s g of 0.30.

Table 3. Bivariate t-test of mean difference between WHO-5 posttest scores and pretest meana.

Discussion

Our findings, composed of qualitative and quantitative results support existing evidence that interventions in educational settings may help to improve mental wellbeing among children living in disadvantaged settings (Welsh et al., Citation2015). The primary qualitative results suggested that when incorporated into a school-based blended learning program for adolescents regardless of their mental health symptoms or coping abilities the HH app showed promise in improving emotional problem-solving competencies by positively affecting aspects like self-management, decision-making, and help-seeking behavior. Our main quantitative findings show a significant increase in adolescent well-being from before to after the brief, 10-session intervention. Both qualitative and quantitative results highlight the app’s potential on improving social and emotional skills, problem-solving skills, and overall well-being of adolescents. Further, both teachers and adolescents reported positive experiences regarding the app’s usefulness and feasibility.

Social and emotional skills

Both male and female adolescents indicated that their capacity to identify feelings and thoughts, as well as understand their impact on behavior, had improved over 10 sessions. The adolescents noted that the app had educated them on how to detect detrimental, negative thought patterns and manage them effectively. Teachers had noticed an increased tendency toward self-support among the adolescents, indicating increased self-efficacy. The adolescents reported feelings of higher confidence in various day-to-day situations, and some adolescents said that they struggled less with anxiety, hopelessness, depression, relationship problems, bullying, and anger problems after having played the app. Our results suggest that the HH app has had a favorable impact on adolescents’ self-management skills, specifically enhancing their awareness of their own feelings, thoughts, and coping strategies. These observed shifts align well with the theoretical foundations of low-intensity cognitive behavioral programs and their potential to induce change (Bennett-Levy et al., Citation2010).

Notably, the adolescents in our study indicated that managing challenging emotional situations and sharing their feelings became easier after app usage, suggesting practical, day-to-day benefits. This also suggested the game’s tangible impact on real life. Adolecents reported identifying new and better ways to deal with anger, sadness, and anxiety, and generally finding expressing themselves and their emotional needs easier, and help-seeking less difficult. Teachers noted enhanced self-management among the adolescents, as well as improved ability to regulate their emotions, thoughts, and behaviors in diverse everyday contexts. Progress in responsible decision-making was also reported. Adolescents stated that the HH app helped support better decision-making, particularly by teaching them self-control in situations involving conflict or bullying. Teachers observed that the adolescents seemed more inclined to make thoughtful choices after using the app, corroborating previous research that highlights improved problem-solving abilities following the use of CBT tools (Oldershaw et al., Citation2012).

Higher well-being

We found clear indications of the app as a tool that may help increase well-being, in line with results found in previous pilot studies of the HH app (Raknes, Citation2020, Citation2021). Our qualitative data indicate that well-being improved, as adolescents expressed more positive affect, reduced negative affect, better self-efficacy, better social recognition, and more optimism after using the game app. Our findings align with existing research on CBT-based interventions, including data from a randomized, controlled study that examined the analog version of the HH program as a school-based intervention which demonstrated significantly reduced symptoms of anxiety, impairment, and depression among adolescents (Haugland et al., Citation2020). These effects were also observed to persist one year post-intervention (Wergeland et al., Citation2023). Our findings correspond with other studies showing school-based PSS initiatives can be beneficial for adolescents in fragile contexts and emergency settings (Smart et al., Citation2019), and with studies finding that CBT-based tools integrated into short PSS programs can reduce problems and increase well-being (Bennett-Levy et al., Citation2010; Haugland et al., Citation2020). Further, our findings are in line with research documenting the positive impact of digital health tools for adolescents in poverty (Patel et al., Citation2018), and with research on the potential for experiential educational games to promote learning, health, and well-being in adolescents (Carlier et al., Citation2020; Lawrence et al., Citation2020; Sun-Lin & Chiou, Citation2019; Zayeni et al., Citation2020).

Null results in stratified models indicate that improvements in mental wellbeing did not differ by adolescent gender. It is of note that the baseline wellbeing averages were somewhat higher for females than males, which remained true at post-test, however wellbeing scores were not significantly different between males and females at either time point. Although existing research on gender differences in mental health within this population is highly limited, cultural expectations and gender roles in the Syrian refugee context in Lebanon suggest social wellbeing may differ for males and females (DeJong et al., Citation2017). Overall, our findings suggest that the HH app may be applicable for both males and females.

Mental health

Social and emotional learning fosters both individual well-being and the quality of interpersonal relationships (Inter-agency Network for Education in Emergencies, Citation2018). In keeping with these social improvements, teachers indicated that the HH app played a role in enhancing positive social recognition among adolescents. Adolescents noted better relations with friends and family, including reduced instances of conflict and heightened supportiveness. Before the HH app intervention, teachers observed that a considerable number of students were reluctant to talk about their struggles, viewing such openness as culturally taboo—a finding consistent with earlier research on Arab cultural norms (Al Laham et al., Citation2020). Post-intervention, teachers reported a noticeable shift in students’ willingness to seek help and advice. It is therefore reasonable to infer that the HH app heightened adolescents’ recognition of the importance of seeking help, a key mechanism for enhancing problem-solving skills and overall well-being among adolescents at risk. Additionally, teachers mentioned that the HH app facilitated discussions about mental health topics that are generally socially stigmatized. This suggests that the app not only boosted health literacy among adolescents but also enriched teachers’ understanding, thereby raising awareness and openness about mental health issues within the broader school community. These findings are promising and resonate with research showing that interventions aimed at promoting help-seeking can positively alter attitudes, intentions, and behaviors toward seeking professional help, while simultaneously reducing the personal stigma associated with mental health issues (Xu et al., Citation2018).

Strengths and limitations

The present study examines the impact of a mental health intervention on changes in individual adolescent mental health. Even though the HH app could be a useful tool, it is important to acknowledge the underlying structural and political determinants of mental health for Syrian refugees in Lebanon that are not addressed by this intervention. More work is needed to develop multi-level interventions that take into consideration the environmental resources available to address structural and interpersonal violence and education barriers/school dropout rather than only individual resources that contribute to mental health and wellbeing (Miller & Rasmussen, Citation2010, Citation2017). Reducing social and economic discrimination by developing policies that promote rather than constrain employment and education opportunities could be important factors needed to increase program participation and sustain intervention effects (Miller & Rasmussen, Citation2017).

Methodologically, the mixed methods approach allowed for methodological triangulation which enhanced the scope and rigor of our study, providing a more in-depth understanding of the role of the usability, acceptability, and effectiveness of HH. However, the study design was not suitable for drawing firm causal conclusions. Without a comparison group, confounding factors can potentially explain changes from pre- to post. For example, historical exposure to traumatic events and access to other social and economic resources could influence results. These are common limitations of such one-group, pre-post designs typically used in first trials of new SEL interventions. Further, the post-tests were conducted only one week after the last SEL session, hence whether and eventually for how long the impact of the intervention lasted is unknown. Related, future research should examine the feasibility and acceptability of scaling up the intervention with particular attention to dose-response effects. Acknowledging the potential for confirmation bias due to the significant involvement of Dr. Raknes, the main developer of the HH app and the study’s first author, in supervising and facilitating the study, measures were taken to mitigate this risk. Dr. Raknes abstained from engaging in data collection and analysis to ensure objectivity. Instead, the qualitative analysis was entrusted to a single investigator, the third author, who is fluent in Arabic, which allowed for nuanced understanding of the data. However, relying on a single qualitative analyst may have constrained the diversity of interpretations. Additionally, all quantitative analyses were carried out by the second author, thereby further minimizing the risk of confirmation bias in the study’s outcomes.

In the school-year 2020–2021, 49% of refugee children in Lebanon did not attend school (Watkins & Zyck, Citation2014). Digital approaches like the HH app may be best for mental health outreach outside of the school context and delivered by training parents and members of the community. However, technological limitations are common (Hampshire et al., Citation2015; Huang et al., Citation2019; Samuels et al., Citation2020) and of note. The majority of the targeted adolescents did not have access to personal mobile phones; rather, they relied on electronic devices furnished by the education center that implemented the program. Adolescents and teachers with limited digital or reading proficiency may face difficulties in handling the technical elements of such interventions and might thus need specific guidance for optimal utilization. Future research should explore the feasibility and acceptability of involving parents and implementing the HH app in a home-based setting.

Conclusion

When employed as a universal school-based intervention among displaced Syrian adolescents in Lebanon, the HH app seemed to improve general well-being while promoting social and emotional skills, particularly in the domains of emotional self-regulation, decision-making, and help-seeking behavior. These results contribute to the accumulating evidence on digital health interventions and the efforts to develop tools that support well-being for all. Upscaling implementation of psychosocial support interventions for adolescents in a fragile context is urgently needed.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Innovation Norway and The Norwegian Research Council, Vision 2030, for supporting development and proof-of-concepts studies of The Happy Helping Hand. Thanks to Midsund Rotary Klubb, Norway, for covering costs for implementing psychosocial support for the first implementation in this study. Thanks to Multi Aid Programs Lebanon for steady supporting adolescents through implementing programs to and through Syrian refugees and making this study possible.

Disclosure statement

I, Dr. Solfrid Raknes, have the following commercial relationship to disclose: Happy Helping Hand is a self-help material I have commercial interests in, in accordance with the standard sharing rules for innovation in the public and private health sector in Norway. Other authors do not have any competing interests to report.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abel, T., & Benkert, R. (2022). Critical health literacy: Reflection and action for health. Health Promotion International, 37(4), daac114. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daac114

- Al Laham, D., Ali, E., Mousally, K., Nahas, N., Alameddine, A., & Venables, E. (2020). Perceptions and health‐seeking behaviour for mental illness among Syrian refugees and Lebanese community members in Wadi Khaled, North Lebanon: A qualitative study. Community Mental Health Journal, 56(5), 875–884. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-020-00551-5

- Al-Khayatm, A. (2021). Digitalized psychosocial support in education exploring the impact of the Happy Helping Hand app for displaced Syrian adolescents in Lebanon. Oslo Metropolitan University.

- Bennett-Levy, J., Richards, D., Farrand, P., Christensen, H., & Griffiths, K. (2010). Oxford guide to low intensity CBT interventions. Oxford University Press.

- Bracken, P., Giller, J. E., & Summerfield, D. (1997). Rethinking mental health work with survivors of wartime violence and refugees. Journal of Refugee Studies, 10(4), 431–442. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/10.4.431

- Bracken, P. J., Giller, J. E., & Summerfield, D. (1995). Psychological responses to war and atrocity: The limitations of current concepts. Social Science & Medicine, 40(8), 1073–1082. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(94)00181-r

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brown, F. L., Aoun, M., Taha, K., Steen, F., Hansen, P., Bird, M., Dawson, K. S., Watts, S., El Chammay, R., Sijbrandij, M., Malik, A., & Jordans, M. J. D. (2020). The cultural and contextual adaptation process of an intervention to reduce psychological distress in young adolescents living in Lebanon. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 212. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00212

- Brun, C., Fakih, A., Shuayb, M., & Hammoud, M. (2021). The economic impact of the Syrian refugee crisis in Lebanon. https://wrmcouncil.org/publications/research-paper/the-economic-impact-of-the-syrian-refugee-crisis-in-lebanon-what-it-means-for-current-policies/

- Bryant, R. A., Malik, A., Aqel, I. S., Ghatasheh, M., Habashneh, R., Dawson, K. S., Watts, S., Jordans, M. J. D., Brown, F. L., van Ommeren, M., & Akhtar, A. (2022). Effectiveness of a brief group behavioural intervention on psychological distress in young adolescent Syrian refugees: A randomised controlled trial. PLoS Medicine, 19(8), e1004046. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1004046

- Burchert, S., Alkneme, M. S., Bird, M., Carswell, K., Cuijpers, P., Hansen, P., Heim, E., Harper Shehadeh, M., Sijbrandij, M., Van’t Hof, E., & Knaevelsrud, C. (2018). User-centered app adaptation of a low-intensity e-mental health intervention for Syrian refugees. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, 663. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00663

- Carlier, S., Van der Paelt, S., Ongenae, F., De Backere, F., & De Turck, F. (2020). Empowering children with ASD and their parents: Design of a serious game for anxiety and stress reduction. Sensors, 20(4), 966. https://doi.org/10.3390/s20040966

- Dangmann, C. (2022). Good starts: Mental health and resilience in resettled Syrian refugee youth. https://brage.inn.no/inn-xmlui/handle/11250/2977015

- DeJong, J., Sbeity, F., Schlecht, J., Harfouche, M., Yamout, R., Fouad, F. M., Manohar, S., & Robinson, C. (2017). Young lives disrupted: gender and well-being among adolescent Syrian refugees in Lebanon. Conflict and Health, 11(Suppl 1), 23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-017-0128-7

- Diab, J. (2022). Syrian refugee youth in Lebanon FES MENA youth study: Results analysis. F. E. Stiftung. https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/international/19847-20230223.pdf

- Doumit, R., Kazandjian, C., & Militello, L. K. (2020). COPE for adolescent Syrian refugees in Lebanon: A brief cognitive–behavioral skill-building intervention to improve quality of life and promote positive mental health. Clinical Nursing Research, 29(4), 226–234. https://doi.org/10.1177/1054773818808114

- Fairburn, C. G., & Patel, V. (2017). The impact of digital technology on psychological treatments and their dissemination. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 88, 19–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2016.08.012

- Göransson, M. B., Hultin, L., & Mähring, M. (2020). ‘The phone means everything.’ Mobile phones, livelihoods and social capital among Syrian refugees in informal tented settlements in Lebanon. Migration and Development, 9(3), 331–351. https://doi.org/10.1080/21632324.2020.1746029

- Habib, R. R., Ziadee, M., Abi Younes, E., El Asmar, K., & Jawad, M. (2020). The association between living conditions and health among Syrian refugee children in informal tented settlements in Lebanon. Journal of Public Health, 42(3), e323–e333. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdz108

- Halliday, J. A., Hendrieckx, C., Busija, L., Browne, J. L., Nefs, G., Pouwer, F., & Speight, J. (2017). Validation of the WHO-5 as a first-step screening instrument for depression in adults with diabetes: Results from Diabetes MILES–Australia. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice, 132, 27–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2017.07.005

- Hampshire, K., Porter, G., Owusu, S. A., Mariwah, S., Abane, A., Robson, E., Munthali, A., DeLannoy, A., Bango, A., Gunguluza, N., & Milner, J. (2015). Informal M-health: HOW are young people using mobile phones to bridge healthcare gaps IN SUB-SAHARAN Africa? Social Science & Medicine, 142, 90–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.07.033

- Hassan, G., Kirmayer, L., A., M., Quosh, C., el Chammay, R., Deville-Stoetzel, J. B., Youssef, A., Jefee-Bahloul, H., Barkeel-Oteo, A., Coutts, A., Song, S., & Ventevogel, P. (2015). Culture, context and the mental health and psychosocial wellbeing of Syrians. A review for mental Health and psychosocial support staff working with Syrians affected by armed conflict. https://www.unhcr.org/media/culture-context-and-mental-health-and-psychosocial-wellbeing-syrians-review-mental-health-and

- Haugland, B. S. M., Haaland, Å. T., Baste, V., Bjaastad, J. F., Hoffart, A., Rapee, R. M., Raknes, S., Himle, J. A., Husabø, E., & Wergeland, G. J. (2020). Effectiveness of brief and standard school-based cognitive-behavioral interventions for adolescents with anxiety: A randomized noninferiority study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 59(4), 552–564.e2–e552. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2019.12.003

- Huang, K.-Y., Lee, D., Nakigudde, J., Cheng, S., Gouley, K. K., Mann, D., Schoenthaler, A., Chokshi, S., Kisakye, E. N., Tusiime, C., & Mendelsohn, A. (2019). Use of technology to promote child behavioral health in the context of pediatric care: A scoping review and applications to low- and middle-income countries. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10(806), 806. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00806

- INEE. (2016). Psychosocial support and social and emotional learning for children and youth in emergency settings. T. I.-A. N. f. E. i. E. (INEE).

- Inter-agency Network for Education in Emergencies. (2018). Psychosocial support and social emotional learning online module. Creative Associates. https://inee.org/resources/psychosocial-support-and-social-emotional-learning-online-module

- Jefee-Bahloul, H., Moustafa, M. K., Shebl, F. M., & Barkil-Oteo, A. (2014). Pilot assessment and survey of Syrian refugees’ psychological stress and openness to referral for telepsychiatry (PASSPORT study). Telemedicine Journal and e-Health, 20(10), 977–979. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2013.0373

- Jost, J. T. (2024). Grand challenge: Social psychology without hubris. Frontiers in Social Psychology, 1, 1283272. https://doi.org/10.3389/frsps.2023.1283272

- Kazour, F., Zahreddine, N. R., Maragel, M. G., Almustafa, M. A., Soufia, M., Haddad, R., & Richa, S. (2017). Post-traumatic stress disorder in a sample of Syrian refugees in Lebanon. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 72, 41–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2016.09.007

- Kerbage, H., Marranconi, F., Chamoun, Y., Brunet, A., Richa, S., & Zaman, S. (2020). Mental health services for Syrian refugees in Lebanon: Perceptions and experiences of professionals and refugees. Qualitative Health Research, 30(6), 849–864. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732319895241

- Khamis, V. (2019). Posttraumatic stress disorder and emotion dysregulation among Syrian refugee children and adolescents resettled in Lebanon and Jordan. Child Abuse & Neglect, 89, 29–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.12.013

- Lawrence, K., Hanley, K., Adams, J., Sartori, D. J., Greene, R., & Zabar, S. (2020). Building telemedicine capacity for trainees during the novel coronavirus outbreak: a case study and lessons learned. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 35(9), 2675–2679. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-05979-9

- Liem, A., Natari, R. B., Jimmy, & Hall, B. J. (2021). Digital health applications in mental health care for immigrants and refugees: A rapid review. Telemedicine Journal and e-Health, 27(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2020.0012

- Mancini, M. A. (2020). A pilot study evaluating a school-based, trauma-focused intervention for immigrant and refugee youth. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 37(3), 287–300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-019-00641-8

- Mattingly, J. (2017). Approaches to providing psycho - social support for children, teachers and other school staff, and social and emotional learning for children in protracted conflict situations. K. D. H. Report.

- Miller, K. E., & Rasmussen, A. (2010). War exposure, daily stressors, and mental health in conflict and post-conflict settings: Bridging the divide between trauma-focused and psychosocial frameworks. Social Science & Medicine, 70(1), 7–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.029

- Miller, K. E., & Rasmussen, A. (2017). The mental health of civilians displaced by armed conflict: An ecological model of refugee distress. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 26(2), 129–138. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796016000172

- Oldershaw, A., Simic, M., Grima, E., Jollant, F., Richards, C., Taylor, L., & Schmidt, U. (2012). The effect of cognitive behavior therapy on decision making in adolescents who self‐harm: A pilot study. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 42(3), 255–265. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1943-278X.2012.0087.x

- Patel, V., Saxena, S., Lund, C., Thornicroft, G., Baingana, F., Bolton, P., Chisholm, D., Collins, P. Y., Cooper, J. L., Eaton, J., Herrman, H., Herzallah, M. M., Huang, Y., Jordans, M. J. D., Kleinman, A., Medina-Mora, M. E., Morgan, E., Niaz, U., Omigbodun, O., … UnÜtzer, J. (2018). The Lancet Commission on global mental health and sustainable development. Lancet, 392(10157), 1553–1598. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31612-X

- Queroue, M., Pouymayou, A., Pereira, E., Tzourio, C., González-Caballero, J. L., & Montagni, I. (2021). An interactive video increasing French students’ mental health literacy: A mixed-methods randomized controlled pilot study. Health Promotion International, 38(4), 13. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daab202

- Raknes, S. (2010). Psykologisk forstehjelp for ungdom. Gyldendal forlag.

- Raknes, S. (2020). The happy helping hand used by Syrian displaced adolescents in Lebanon: A pilot study of feasibility, usefulness and impact. http://solfridraknes.no/filer/HH_pilotHaidar_2020!.pdf

- Raknes, S. (2021). Does group size and blending matter? Impact of a digital mental health game implemented with refugees in various settings. http://solfridraknes.no/filer/Research/Group%20size%20and%20blending%20matter!.pdf

- Raknes, S. (2022). The happy helping hand manual. https://solfridraknes.no/filer/englishNy%20mappe/HHManual_English_2023.pdf

- Rasmussen, L., & Neumer, S. (2020). Tidsskrift for virksomme tiltak for barn og unge. Ungsinn, 2.utg(1).

- Reed, R. V., Fazel, M., Jones, L., Panter-Brick, C., & Stein, A. (2012). Mental health of displaced and refugee children resettled in low-income and middle-income countries: Risk and protective factors. Lancet (London, England), 379(9812), 250–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60050-0

- Samuels, F., Rost, L., Leon-Himmelstine, C., & Marcus, R. (2020). Digital approaches to adolescent mental health: A review of the literature. https://cdn.odi.org/media/documents/odi_digitalapproachesmentalhealth_final.pdf

- Schuler, B. R., & Raknes, S. (2022). Does group size and blending matter? Impact of a digital mental health game implemented with refugees in various settings. International Journal of Migration, Health and Social Care, 18(1), 83–94. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJMHSC-07-2021-0060

- Sender, H., Orcutt, M., Btaiche, R., Dabaj, J., Nagi, Y., Abdallah, R., Corona, S., Moore, H., Fouad, F., & Devakumar, D. (2023). Social and cultural conditions affecting the mental health of Syrian, Lebanese and Palestinian adolescents living in and around Bar Elias, Lebanon. Journal of Migration and Health, 7, 100150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmh.2022.100150

- Sibai, A. M., Chaaya, M., Tohme, R. A., Mahfoud, Z., & Al-Amin, H. (2009). Validation of the Arabic version of the 5-item WHO Well Being Index in elderly population. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 24(1), 106–107. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.2079

- Sim, A., Bowes, L., & Gardner, F. (2019). The promotive effects of social support for parental resilience in a refugee context: A cross-sectional study with Syrian mothers in Lebanon. Prevention Science, 20(5), 674–683. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-019-0983-0

- Sim, A., Fazel, M., Bowes, L., & Gardner, F. (2018). Pathways linking war and displacement to parenting and child adjustment: A qualitative study with Syrian refugees in Lebanon. Social Science & Medicine, 200, 19–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.01.009

- Smart, A., Sinclair, M., Benavot, A., Bernard, J., Chabbott, C., Russell, S. G., & Williams, J. (2019). NISSEM Global Briefs: Educating for the social, the emotional and the sustainable. UNESCO. Global Education Monitoring Report.

- Sun-Lin, H.-Z., & Chiou, G.-F. (2019). Effects of gamified comparison on sixth graders’ algebra word problem solving and learning attitude. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 22(1), 120–130.

- Syam, H., Venables, E., Sousse, B., Severy, N., Saavedra, L., & Kazour, F. (2019). “With every passing day I feel like a candle, melting little by little.” Experiences of long-term displacement amongst Syrian refugees in Shatila, Lebanon. Conflict and Health, 13(1), 45. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-019-0228-7

- The World Bank. (2021). Lebanon economic monitor: Lebanon sinking (to the Top 3). The World Bank.

- Townsend, D., Raknes, S., & Hammoud, M. (2022). Psychosocial support for Syrian refugee youth. In Psychological perspectives on understanding and addressing violence against children: Towards building cultures of peace (p. 272). Oxford University Press.

- UNICEF. (2014). Syrian refugees staying in informal tented settlements in Jordan. UNICEF.

- Watkins, K., & Zyck, S. (2014). Living on hope, hoping for Education: The failed response to the Syrian refugee crisis. (ODI) Overseas Development Institute Report, 1, 13.

- Welsh, J., Strazdins, L., Ford, L., Friel, S., O'Rourke, K., Carbone, S., & Carlon, L. (2015). Promoting equity in the mental wellbeing of children and young people: A scoping review. Health Promotion International, 30 (suppl 2), ii36–ii76. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dav053

- Wergeland, G. J. H., Haaland, Å. T., Fjermestad, K. W., Öst, L.-G., Gjestad, R., Bjaastad, J. F., Hoffart, A., Husabo, E., Raknes, S., & Haugland, B. S. (2023). Predictors of school-based cognitive behavior therapy outcome for youth with anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 169, 104400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2023.104400

- World Health Organization. (2018a). Country cooperation strategy: Lebanon: 2019-2023. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-EM-PME-009-E

- World Health Organization. (2018b). Health promotion for improved refugee and migrant health. World Health Organization. Regional Office for the Europe.

- World Health Organization. (2022). Annual report 2021: Building back better while leaving no one behind: WHO Lebanon country office crises support. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/365887

- Xu, Z., Huang, F., Kösters, M., Staiger, T., Becker, T., Thornicroft, G., & Rüsch, N. (2018). Effectiveness of interventions to promote help-seeking for mental health problems: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 48(16), 2658–2667. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291718001265

- Zayeni, D., Raynaud, J.-P., & Revet, A. (2020). Therapeutic and preventive use of video games in child and adolescent psychiatry: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 36. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00036

- Zijlstra, J., & Liempt, I. V (2017). Smart (phone) travelling: Understanding the use and impact of mobile technology on irregular migration journeys. International Journal of Migration and Border Studies, 3(2/3), 174–191. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJMBS.2017.083245

Appendix A:

Semi-structured interview guide

Interview guide for students/adolescents

The purpose of this interview is to examine how the Helping Hand app is used by Syrian refugee adolescents in Lebanon and how you experience the app.

Background

Let´s get to know each other.

I will start by presenting myself, my background, what I work with, and why I am doing this research.

1. Can you introduce yourselves?

How old are you?

What grade are you in?

For how long have you been attending school?

Where do you currently live? (House? Apartment? Tent? Other?)

With whom do you live now?

Questions related to the HH app

2. You have been participating in groups where you have been using the HH app.

Can you explain what the HH app is?

How did you experience the app?

Is it difficult/easy to use?

What is your impression of the language used in the app? Is the vocal language.

easy to understand? Is the written language easy to understand?

To what extent is the different scenarios relevant to your lives?

What do you think of the main characters in the game?

Can you relate any of these characters to yourself or any of your friends?

How many times have you used the HH app in the group?

Did you use the HH app at home or in your spare time? If yes, why did you use it?

In your opinion, is it important for you to use the HH app? If yes, why? If not, why?

Question about having used the app

3. Did you first use the HH app before, during, or after attending the HH groups? How?

4. Can you, in your opinion, explain the utility of the HH app?

5. In your opinion, to what extent is the HH app engaging? Why so? And what aspects of the HH app are the most engaging/entertaining?

6. Have you had a life experience that is relatable to the scenarios in the HH app? Can you explain?

7. Have you had any negative experiences related to the HH app? Can you explain?

8. Have you had any positive experiences related to the HH app? Can you explain?

Question about emotional coping before using the HH app

The following questions relate to the time before you started using the HH app.

9. How did you tend to act/behave under difficult circumstances?

How did you react when getting angry? (e.g. at parents, siblings, other kids/adolescents and other adults you live with)

How did you react when you got scared? (e.g. in a specific situation, or school, before holding a presentation)

How did you react when experiencing painful memories?

10. Can you explain how you used to express your emotions under difficult circumstances?

Questions related to emotional coping after using the HH app

The following questions relate to the time after you started using the HH app.

11. You have during the past weeks been using the HH app; a digital game intended to enhance the user´s ability to cope with emotionally difficult circumstances and provide emotional support to friends and family.

How do you cope with difficult circumstances after using the HH app?

Do you do anything differently after having used the HH app?

How do you support friends and family in coping with difficult circumstances after using the HH app? Can you explain?

Has using the app influenced the way you express your emotions? If yes, how? If no, why not?

12. The HH app is also intended to help the user see more options and possibilities when a difficult circumstance emerges.

How have you coped with difficult circumstances arising after using the HH app?

Had the app helped you solve day-to-day problems? Can you explain?

Feedback

13. In your opinion, are digital tools providing emotional support of benefit to adolescents at your age? Why? Why not?

14. Do you have any advice for the producers of the HH app? How can they improve the activities in the game to make it more suitable for adolescents your age?

15. Do you have any more feedback for the producers of the HH app?

Interview guide for teachers and PSS staff

The purpose of this interview is to evaluate the utility of the Helping Hand app in providing psychosocial support in the education of Syrian refugee adolescents in Lebanon. Ím interested in your experiences regarding the training you received in using the Helping

Hand app; your experience in teaching the use of the HH app to students; what observations you have made related to the mental health/mental well-being of the adolescents/students after the implantation of the app.

Background

1. I suggest we start by introducing ourselves. Could you in short tell me…

What is your current position?

How long have you worked with MAPs and your work experience in teaching or as psycho-social support (PSS) staff?

Do you have any experience working with teaching arrangements or projects intended to provide psycho-social support to adolescents? Could you elaborate?

Reflections on the learning, health, and well-being of adolescents

2. What are your thoughts on/understanding of psychological well-being?

What factors affect/influence the psychological well-being of Syrian refugee adolescents? Can you provide examples?

3. What are your thoughts on the role of psycho-social support in education? And what is the significance of psycho-social support in the education of Syrian refugee adolescents?

Question related to the implementation of the HH app

4. How would you describe the HH app?

What is its purpose?

5. Can you talk about how you have used the HH app?

For how long and how much have you worked with HH? Do you have one or more groups?

For how long has your class/group worked with/used the app?

Do you have any experience working with the analog version of HH with children?

How do you present the app for adolescents?

Have you used the HH app in groups physically present, or F2F?

If you used the HH app through online classes, what digital platform did you use?

How did it work?

How did you experience the introductory training arrangements to use the HH app prior to teaching it? Did you feel prepared/comfortable teaching it?

How did you utilize the ten-hour introductory training arrangement related to the HH app? Did you utilize all ten hours? If you included some elements and skipped other elements, please elaborate on why.

Did you follow each scene sequentially/chronologically? If not, in which oden did you follow it, and why?

Did you have sufficient time to conduct the introductory training?

Experiences and observations after implementing the HH app

6. What are your experiences on the utility of the HH app?

7. What are your experiences of the significance of the app on adolescents? Why?

8. To what extent did the app engage the adolescents? How?

9. Can you elaborate on how the app affects/influences adolescents?

Did you notice any situations where you suspect the HH app had an influence?

Can you elaborate on any positive experiences the adolescents may have had when using the HH app?

Have you considered any negative experiences the adolescents may have had when using the HH app?

10. Can you provide any examples of situations where you noticed the adolescents acting in a way you suspected the adolescents were acting in a way you suspected is influenced by the HH app?

11. Did you observe the adolescents using the HH app outside of the PSS classes? At home?

Considerations related to the HH app

12. After having used the HH app can you elaborate on your experience related to:

The relationship between the students/adolescents

The adolescent´s ability to self-soothe.

The adolescent´s ability to solve the daily challenges they encounter.

13. To what extent do you perceive the HH app as being of relevance in the adolescent☐s psychological well-being? If so, how is it relevant?

14. Can you comment on your thoughts on social and emotional learning competency in school, and how important this is for the adolescents in school?

Do you perceive it as easier for adolescents to express their emotions after using the app?

Have you experienced a lower threshold among adolescents in asking for help/support or talking about psychological difficulties after using the app?

Questions on the HH app directed to teachers and PSS staff

15. To what extent do you experience the HH app as a useful tool in the face of the challenges you experience in your work?

16. Has the app influenced how you and your colleagues relate and cooperate?

17. Have you had any negative experiences with the HH app? If so, what?

What do you think contributed to these experiences?

Room for improvement of the HH app and the introductory training

18. Can you comment on how the HH app could be different or improved?

19. Can you comment on the writing instructions for the ten-hour introductory training arrangements? How could it be different or improved?

20. Can you comment on the training to use the app for PSS initiatives? How could it is different or improved?