Abstract

Shifting from a linear sales model to a circular service-based business model is far from straightforward. Many challenges accrue in the transition process, including finding the right market for the recirculated product/service, setting up the reverse supply chain, selecting the right partners, and making sure the new business model is sustainable in the short, medium and long term. This paper discusses the challenges of four companies trying to close the loop while preserving current profit levels. It describes their initial ideas on how the circular business model should be designed, the process they went through, challenges faced, and the eventual outcome. Based on the learnings of the four case companies, we summarise recommendations about preparatory steps required before making the transition towards a circular business model.

Introduction

Circular economy is posited as a solution for decoupling economic growth from negative environmental consequences (EMF Citation2013a, Citation2013b). Products, components, and materials are reused, refurbished, remanufactured, or recycled in a circular economy to minimise resource consumption while providing superior service (Kirchherr, Reike, and Hekkert Citation2017). This captures the value that products still contain after usage. Reasoning further, many have argued that businesses will benefit economically, environmentally and socially from circular business models (e.g. McKinsey Citation2016). However, can these projected macro-economic benefits of circular economy directly be translated to concrete micro-economic benefits or will there be many exceptions and caveats? Which steps will companies need to take to reach a profitable circular business model, i.e. what is a feasible transition path?

A four-year European research project (ResCoM Citation2013) followed four companies in their search for circular business models, to conclude that there is no obvious immediate solution. Starting from the circular business model they envisioned, we explored several options to close the loop without reducing their profitability. It turned out to be difficult to shift to a system where products would be used multiple times via reuse/refurbishment/remanufacturing, sometimes combined with leasing/service-based business models, while preserving current profit levels. Companies strongly depend on external conditions (e.g. legislation, competition, consumer behaviour), making it difficult in the current climate to find a business model as profitable as the traditional linear make-use-dispose one. We conclude that the biggest challenge for the circular economy is to help individual companies find a feasible transition plan capable of reaching a profitable circular state. In this paper, we illustrate these transition challenges using the learnings from our four cases. This allows us to distill common challenges companies will have to address on their path towards the circular economy and to develop a framework to help firms assess their current situation.

Methods

Even though circular economy and circular business models are relatively new concepts (Murray, Skene, and Haynes Citation2017), circular economy practices can build on the closed-loop supply chain concept (Gonzalez, Koh, and Leung Citation2019). The field of closed-loop supply chains has been around for more than 30 years and is concerned with strategic, tactical and operations issues around value recovery and product returns (Souza Citation2013). However, despite the vast amount of knowledge in this research field, it is argued that the research may have preceded the evolution of industry towards closed-loop cycles and that it may have become somewhat detached from real problems faced by companies (Atasu, Guide, and Van Wassenhove Citation2008; Guide and Van Wassenhove Citation2009). Lack of relevance is seen as a growing problem within operations and supply chain management (Simpson et al. Citation2015). More case studies are needed to increase the relevance of closed-loop supply chain research to circular economy managerial practices (Guide and Van Wassenhove Citation2007; Agrawal, Atasu, and Van Wassenhove Citation2019). A multiple case study is carried out here to increase the external validity (Yin Citation1981; Voss, Tsikriktsis, and Frohlich Citation2002).

At the start of the research project, a multiple day visit to each company was organised to get a good understanding of their business, their challenges, and their circular business ideas. The visit combined researchers from different disciplines (e.g. supply chain management, design, information technology) and included multiple departments at each company (sales, purchasing, operations, management, etc.) to provide a holistic overview of their current and possible future circular business. The minutes of these visits were transcribed to provide a collection of field notes for analysis (Voss, Tsikriktsis, and Frohlich Citation2002). The initial circular business idea was assessed on its feasibility using simple evaluation tools developed in this project (for more information on the evaluation tools please see Van Loon, Delagarde, and Van Wassenhove Citation2018; Citation2020 and van Loon and Van Wassenhove Citation2018). Suggestions for improvements were discussed. During the four-year research project, multiple iterations consisting of defining and improving circular scenarios and assessing the economic implications were performed to define a circular business model that could be at least as profitable as their current linear model. Data were collected from different departments using their expert knowledge on what the circular business model would mean for their product, supply chain, remanufacturing process, after-sales services, marketing, etc. and used as input for the economic calculations. The results were shown in a workshop at each company involving multiple departments and a discussion followed on how the circular business model could be further improved. The new ideas were calculated through on their economic performance and compared to the linear business model. Two of the four companies moved beyond this exploratory phase and implemented a pilot to test the circular business model in practice. The number of workshops at the company sites and interviews with them between the workshops are summarised in Table .

Table 1. Overview of workshops and interviews per case study.

Know your customers – baby stroller manufacturer

The first case company is a producer of durable baby strollers, known for their high resale value on second-hand markets. Most of their strollers are owned by multiple users before finally being discarded. Efficient multiple reuse via second-hand markets creates the question whether a company should intervene and create a circular business model via leasing and refurbishment or if the consumer-to-consumer reuse has a better environmental performance. Thanks to the flourishing secondary market, strollers are usually owned by several users before being discarded. Replacing this with a system where strollers are leased by several users with the interference of the OEM between each transaction, does not necessarily lead to an extension of the lifespan (i.e. the number of users per stroller) and hence the circular business model will create additional environmental impacts from transport and other activities like remanufacturing compared to the conventional business of sales and second-hand markets. If the goal is sustainability, these impacts need to be assessed carefully.

From an economic point of view, the second-hand market also limits the potential to profitably move to a lease + refurbish business model using multiple leases. Assuming a rational consumer, the resale value is subtracted from the purchase price when calculating total cost of ownership (TCO). The resale value on the second-hand market increases the willingness-to-pay for the new product and hence allows the manufacturer to set high sales prices, increasing the profit margin (Waldman Citation2003; Oraipoulos, Ferguson, and Toktay Citation2012). To be attractive a lease, though potentially offering additional benefits to consumers, cannot be much more expensive than a purchase. This limits the leasing fees for products with high resale values on the second-hand market, putting pressure on the profitability for the manufacturer. These second-hand markets and related consumer behaviours evolved over a long time and are usually notoriously difficult to change. It will take time and effort to replace this successful model with a more circular business model like leasing.

The lease + refurbish model is already challenging in terms of profitability when customers behave perfectly. Unfortunately, a non-negligible share of the customers attracted to the leasing pilot offered by the company to test the model in practice behaved delinquently, further reducing the profitability of the circular business model. The pilot revealed a surprising share of non-paying customers, non-returned strollers, and products clearly showing misconduct. For circular business models to work, changes in consumer behaviour are needed. Consumers should care for the products and take responsibility to return them in good quality so that reuse is possible. Companies need to better understand their customer segments, needs and behaviours. The assumption was made that the pilot would attract well-behaved consumers who are insensitive to the higher TCO for the convenience of leasing. However, the company appeared to have attracted consumers who wanted to be seen with a high-end stroller but could not really afford it, which subsequently caused challenges due to delinquency in payment or returns. When engaging in circular economy, companies need good marketing information, realistic data-driven evidence on their customer segments, and careful calculations on profitability as a function of consumer behaviour (e.g. the cost of chasing leasers to pay their fees).

In addition to potential limits on feasible leasing fees, the manufacturer incurs higher costs in the lease system. When only leasing new products, these additional costs include credit checks, management of payments and customers queries, and return transport costs, not to mention potentially high maintenance expenses. Part of these costs (if not all) can be recovered by capturing the value remaining in the returned products. By refurbishing them, products can be leased another time without the need to manufacture a completely new product. However, the difference between manufacturing and refurbishing costs needs to be extensive to pay for the higher costs of the lease system. Cost recovery in strollers is relatively small and hence the lease model is less attractive for a profit-seeking company, except perhaps for a few small customer segments. In any case, full transition to the circular economy appears to be elusive for these types of products.

Changes to product design might improve the situation. It was argued by the company that their products are extremely durable and can be used by many customers. The focus of their design was a stroller that could be used by more than ten customers. In practice, the return rate and refurbishment yield rate were less than 100%, which means the number of leases per stroller quickly reduced to two to three users (see Geyer, Van Wassenhove, and Atasu Citation2007 or Van Loon, Delagarde, and Van Wassenhove Citation2018). A product design that focuses on improving the return and refurbishing yield rate would have more impact. For example, a product more difficult to break or lose might increase the number of leases per stroller and therefore be more effective in situations where consumers are not behaving perfectly. Companies need to identify the weak points in the circular business models and address these issues accordingly. Otherwise, the risks of transitioning to these models may just be too high.

Know your supply chain and product – washing machine manufacturer

The second case company produces a wide range of washing machines and other white goods. Instead of selling washing machines, the OEM explored the option to lease and remanufacture washing machines, cascading them to less premium markets as the machine ages. High-end customers pay a premium leasing fee for a brand-new washing machine, while medium and low-end customers obtain a leasing fee discount for accepting older, previously used machines. The initial idea seemed to be attractive, providing medium and low-end customers with high-end washing machines (though a few years old) against affordable leasing fees and high reliability, eliminating the usual high repair costs for these segments. The leasing programme could repair this social inequality where people who cannot afford a good quality washing machine pay more per wash (see van loon et al. Citation2020). However, setting the right leasing fees for the three segments to balance the quantities requested by the market is not easy. Wrongly set fees could lead to significant imbalances between the three segments, i.e. supply constraints could easily lead to additional costs or lower revenues than anticipated. Considerable market knowledge is required to correctly set leasing fees for such a cascading model.

Furthermore, operations that are supposedly simple and small, may add considerable costs to the leasing and remanufacturing programme. Remanufacturing the machine twice during its lifespan, to prevent failures during the leases, is relatively expensive due to the high degree of manual labour, compared to efficient automated production of new machines. Second, additional transportation of washing machines back and forth to customers for remanufacturing purposes increases costs. Maintenance and service costs might also turn out to be larger than expected and these first-mile logistics costs to serve customers are increasing fast. Finally, administration costs to monitor payments are significantly higher in leasing schemes, compared to selling products. The manufacturing company is not set-up to deal with these activities on individual customer level and would likely need to partner with other supply chain players who might capture part (if not all) of the economic benefits.

One exception would be if leasing and remanufacturing leads to an increased lifespan of the washing machine. It is argued that white goods producers might be able to manufacture products with longer lifespans and that leasing would be a key feature to change OEM objectives when manufacturing products (EMF Citation2013a). Longer lifespans, and hence longer total lease durations, would significantly increase revenue and improve profitability. This argument clearly neglects the impact of technological innovation. Washing machines continuously reduce energy and water consumption. Hence, increasing the lifespan of washing machines may have a detrimental effect on the environment (Devoldere et al. Citation2009; O’Connell, Hickey, and Fitzpatrick Citation2013). To benefit from technological improvements and long lifespans at the same time, new designs will have to incorporate technical updates over time, while simultaneously reuse other parts. While this can be envisioned for small to moderate improvements, larger innovations (e.g. washing without water) might still lead to premature obsolescence. This risk of obsolescence is clearly incurred by the OEM in the lease programme since customers may refuse to lease older product types after major technological improvements.

Access to market and material value – automotive component manufacturer

The third case company manufactures automotive parts. While the automotive industry remanufactures components since the 1950s, remanufactured OEM parts represent only a small percentage of the total aftermarket. If an OEM supplier would want to expand its remanufacturing business beyond the OEM controlled return system, it needs to acquire cores and sell remanufactured products on the so-called free market with strong competition. Hence, intelligence about this market including its customers and competitors is vital. The company needs to assess how to access cores, ensure their quality is good, and decide what to pay for those good quality cores. Simultaneously, a thorough assessment of the market for remanufactured products should be performed, including realistic sales prices, the size of the market, the sales channel to use (via third-parties or directly yourself), how to balance demand with supply, etc. This data can then be used to estimate the profitability of a remanufacturing business. Problems like this have been extensively studied in the closed-loop supply chain literature (e.g. Guide, Teunter, and Van Wassenhove Citation2003; Guide and Van Wassenhove Citation2009).

Our assessment in the automotive case involving chassis products showed that the production of new products is relatively inexpensive compared to the costs for acquiring cores on the free market, the return transport costs, and the labour-intensive remanufacturing process where individual items need to be checked, disassembled, cleaned, repaired, assembled, tested, and packed (see van Loon and Van Wassenhove Citation2018). Indeed, new production is highly automated and high volume leading to relatively low manufacturing costs through substantial economies of scale. Remanufacturing tends to be small volume highly manual production and therefore relatively expensive, especially on the labour side. This equation might be different if remanufacturing could benefit from scale economies but this poses the question of how to transition from the current situation to a future state where high demand for remanufactured products would be commonplace.

The amount of material saved in remanufacturing our case company product compared to new production does simply not result in enough savings compared to the additional labour costs associated with remanufacturing. A relatively high material and value recovery in the product is a prerequisite for a profitable remanufacturing business. Indeed, most examples of successful remanufacturing businesses are for heavy, expensive durable assets, for example, Caterpillar and Airbus.

From an environmental perspective, remanufacturing these types of products leads to environmental benefits. Reusing parts and components in a manual remanufacturing process use significantly less energy than production and associated extraction and processing of raw materials. Clearly, environmental impacts are not sufficient for companies to change their business model, especially when this could lead to significantly reduced profits.

Innovation and upgradeability – TV manufacturer

The last case company manufactures high-end TVs. The company wanted to explore remanufacturing. Taking back TV sets for reuse, refurbishment, or remanufacturing requires a market for TVs which are a couple of years old. Technological innovation is fast in this market, with distinguishable new TV models every six months. Consequently, a substantial discount is needed, forcing competition with low priced TVs, which does not make it worth the effort. It is more difficult to apply circular business models in a fast-changing technology environment.

Instead of closing the loop the company subsequently explored product life extension by offering upgrades during the use phase. Workshops were held to discuss what such business model would mean for their product design, marketing, and after sales services and the profitability was calculated. A significant number of upgrades need to be sold to cover the loss in revenue due to longer product use and resulting lower new product sales. In addition, the relative costs will increase when one-off sales are replaced by smaller transactions involving multiple upgrades over time. In this case, the modular product design required to enable upgrades was also more expensive than the conventional TV design. The higher costs and lower revenues made the circular model unattractive from a business perspective. Note that these arguments do not even incorporate consumer behaviour. It may indeed be very hard to convince buyers of expensive high-end TV sets to purchase highly-priced upgrades instead of the newest model.

From an environmental point of view, applying circular economy principles to high-innovation products is also questionable. Creating products that are modular and upgradeable to slow down product sales, can increase obsolescence of product parts and components (Agrawal and Ülkü Citation2013; Agrawal, Atasu, and Ülkü Citation2016). As before, a good understanding of markets and consumer behaviour is needed to ensure that the envisioned effects of the circular economy are reached.

Challenges in the transition towards a circular business model

Even though the four case companies operate in industries with different characteristics, they all faced issues in their search for profitable circular models. Their challenges are summarised in Table . The evaluations in the Table are of course relative and perhaps even somewhat subjective. They merely indicate challenges faced when considering leasing, remanufacturing, product life extension or a combination.

Table 2. Challenges in the transition towards circular models (high means a big concern).

For instance, strollers are heavily susceptive to consumer behaviour. The value that can be recovered from strollers is relatively low since the textile parts as well as the moving parts need to be replaced, essentially leaving only the frame for reuse. Access to good quality returns may not be easy if consumers misuse or damage the product, or fail to return it, a medium concern that may be manageable. However, radical types of innovation are unlikely for strollers. This is not a real concern.

Washing machines are less susceptible to misconduct as it is possible to make them unusable from a distance. This makes it easier to keep control on product returns. However, a good balancing of demand is needed to cascade products in other markets when they age, a medium concern that needs to be carefully managed. The value of used washing machines is relatively high and product life extension is possible, making it worthwhile to invest in circular business models provided that technological innovations can be implemented in existing washing machines, a medium concern for the OEM.

The strong competition for used products in the automotive industry makes it difficult to acquire good quality cores, which is the largest obstacle for this OEM and limits the profitability of the remanufacturing business. Finally, TVs are an example of products with high technological innovation, making it difficult to find a market for used TVs or even for product life extension. A good understanding of the different markets with the different needs is required to be able to offer upgrades to extend the product life without reducing the profitability level.

The first challenge is to understand the market for recirculated products. How big is demand for circular products, which customer segment would you target, what requirements do these customers have, what is their expected behaviour and what are their alternatives (e.g. second-hand market). Unfortunately, not all customers take good care of products that are not their own, especially when the financial consequences of delinquent behaviours are small. For companies it is usually extremely difficult to change customer behaviour. Large deposits will diminish the advantages of leasing, but small deposits do not cover costs in case of misconduct. Realistic assumptions about customer behaviour (and its impact on return rates and remanufacturing yield rates) are required to make reliable cost and profit estimations and assess if the circular offer will be profitable (and environmentally benign).

The second challenge is to keep additional costs of operating a circular business model low compared to the cost savings of remanufacturing instead of new production. Indeed, if the cost difference between manufacturing and remanufacturing is small, the administration costs and return transport costs might dominate these costs savings, leading to higher overall costs (and probably higher levels of uncertainty) for remanufactured products. Given the general need to provide a discount to market remanufactured products (Abbey et al. Citation2017; Guide and Li Citation2010), this will lead to lower profits and hence less interesting business models for a profit-seeking firm. While manufacturing tends to be automated and benefits from economies of scale, remanufacturing is a relatively expensive labour-intensive process. It is argued that a tax shift to reduce the costs of labour and increase the costs of resources might help reduce the relative costs of remanufacturing. Yet, until such taxation is operational (assuming it would be desirable, which is beyond this paper), companies will have to find ways to keep the costs of the circular offers low despite higher labour costs. Low recoverable value was clearly an issue for our stroller company.

The third challenge is to have access to good quality products to be recirculated. Products of high quality need less work (and fewer materials) to make them ‘as good as new’. Higher quality returns might be more expensive to acquire, especially in open markets with competition from third-party remanufacturers. Companies tend to have poor knowledge of the market for used products and third-party remanufacturing competitors. This lack of evidence often leads to over-confidence and incorrect risk estimation. These companies may also suffer from internal resistance from their sales departments fearing cannibalisation of the new product markets by the remanufactured product offer. In our experience, these internal discussions are almost always void of factual evidence. Our car parts remanufacturer wisely decided to kill the project as soon as hard facts were gathered on prices for cores and remanufactured products and our simple analytical models (see section ‘the need for simple evaluation tools’) showed that gains were too small and uncertain compared to the costs of remanufacturing operations. It is argued that a business model like leasing, where the company retains ownership of the product would eliminate this problem. However, the risk that consumers do not return the product to the OEM but instead opt to sell it on second-hand markets increases for higher value products with good resale prices. As mentioned above, the costs of chasing delinquent consumers may be substantial and eat into the expected profits.

The fourth challenge is the speed of technological progress. Innovation leads to obsolescence and puts a limit to the recirculation of products no longer adapted to customer preferences. Innovation can also lead to improved energy efficiency. A product design allowing adaptation to changed consumer requirements and improved energy efficiency, while at the same time allowing reuse of components not affected by innovation might result in the lowest possible environmental impact. However, research on such products and related impact on consumer behaviour is in its infancy. Note that such products may require a more expensive design and consumer acceptance is far from given, as illustrated by our TV manufacturer case.

Table is not a panacea and it is incomplete. Its only purpose is to highlight important potential challenges on the road to circularity and to showcase these are very much context-dependent. They not only differ by sector and product type but also by market segment. Sweeping statements about the attractiveness to transition to circular business models at the firm level are not constructive and perhaps even misleading. The devil may well be in the details and although the end state may look attractive, in the current context it may be very hard and risky to find a feasible transition path. The risks of transitioning to a circular business model are large for many OEMs, and their knowledge of the implications of these decisions tends to be poor. This is not surprising since these circular business models, e.g. repeated leasing with intermediary remanufacturing steps, require knowledge which is relatively far from the business-as-usual model.

Transition to the circular economy requires realism

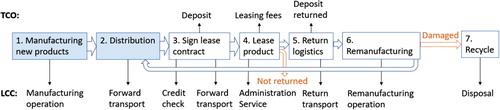

We argued that transition to the circular economy poses several important challenges for most companies. Figure shows additional activities a company will have to perform (or outsource) when switching from a linear-sales to a circular-leasing model. For most companies the stretch is large, i.e. companies will be forced to venture far out of their comfort zone.

Figure 1. Activities in a repeated leasing with remanufacturing business model (based on Van Loon, Delagarde, and Van Wassenhove Citation2018).

Figure (top) illustrates the changes in consumer perspective, using the different elements of the total cost of ownership (TCO). This is new territory for most companies and solid knowledge needs to be gathered on consumer preferences on leasing versus buying at different price levels as well as potential delinquent consumer behaviour (failure to pay lease fees, damaged or non-returned end-of-lease products). The company needs to estimate costs and risks of these elements and acquire competences of managing the additional activities or extend its eco-system with partners to outsource them. Cutting corners by poorly studying these new business models or over-confidence in one’s own products, skills and consumers is risky as illustrated by some of our case examples.

Similarly, Figure (bottom) illustrates the additional activities and cost elements from the perspective of the OEM, i.e. its life cycle cost (LCC). These clearly show the stretch in terms of internal competences. Companies need to carefully evaluate these new activities and their impact on uncertainty and costs.

The need for simple evaluation tools

Although illustrative and rather crude, Figure should make companies aware of the ‘different world’ they are about to enter. This requires careful analysis and perhaps assistance from experts outside their company. The problem is that detailed studies require a lot of data which are simply unavailable. In our opinion, companies need a robust base to align divergent internal opinions around the attractiveness of circular business models before engaging in more costly analyses and perhaps investments to collect data. Simple educational tools assessing the profitability and sustainability of circular versus linear models painting a fair and realistic picture, are badly needed. They can show whether seriously considering a shift to circular models is worthwhile and how much this depends on currently unverified assumptions. These tools should only require aggregate information and data for which ballpark figures can relatively quickly be gathered. For example, when considering a leasing with remanufacturing model, a company needs to estimate the costs of additional transport back and forth to customers, additional administration and financial costs associated with leasing, service/maintenance costs during the lease, and remanufacturing costs (see Figure ). Realistic assumptions about customer behaviour and innovation need to be made to estimate the number of leases and leasing durations per product, since these may have a large impact on revenues. Ballpark figures or reasonable estimates for parameter ranges are sufficient since, for example, the tool will show there is no point in investing in long lifespans if product return rates drop below a certain percentage. This pushes one to verify whether that is likely to happen and what can be done about it. If the outcome is sensitive to this percentage one should invest in a precise estimate through a market study or pilot. It is crucially important to include the TCO for consumers as well as their potential behaviour in the lease versus sales system to stimulate discussions on the profitability of the offer. Frequently, assumptions about consumers are unrealistic and ignore alternative options.

Simple analytical tools, like the ones developed in the ResCoM project, provide an estimate with a minimum of data and effort. See van Loon and Van Wassenhove (Citation2018) for a tool covering the profit and CO2 footprint of remanufacturing for companies like our car parts producer, and van Loon et al. (Citation2018; Citation2020) for estimating the profitability of leasing and refurbishment compared to selling for firms like our stroller or white goods producers. These tools identify the weak spots of the envisioned business model and let companies simulate alternatives. For example, what happens to profitability if we implement ‘design for remanufacturing’, if we outsource return logistics, or if we target other customer segments?

The way forward

Once a potentially profitable business model has been identified the question is how to transition to that state. Several barriers need to be overcome, many outside the influence sphere of the company. These barriers include consumer behaviour, financial constraints and uncertain legislation (Kirchherr et al. Citation2018). Far too little is known on how consumers react to remanufactured products, e.g. in repeated leasing contexts. Research on disgust, the size of the consumer segment refusing to touch a product being used before, is badly needed (Abbey, Blackburn, and Guide Citation2015). Leasing and other circular models completely change cash flows and require alternative funding mechanisms, particularly in the transition period. Finally, legal frameworks are very uncertain and differ across markets, making circular models more fragile than the traditional business-as-usual ones. Companies will need to do their homework to convince owners and money lenders to invest in circular business models. They are advised to carefully pilot their way, learning and adjusting as they move along.

This paper addressed the possibilities and limitations of switching from a linear to a circular model in the current economic setting. With active buy-in of politicians, for example, the circular economy package of the European Commission (EC Citation2018), more possibilities might be created for individual companies to make the change. It should be clear that the combined uncertainties of changing consumer behaviours, financial support, and legal context make it hard for companies to engage, even if the odds look favourable and they essentially believe in sustainability. It is telling that the four case companies in our research were all enthusiastic believers in the circular economy, eager to move forward, but none found an easy transition path at this stage. Indeed, most companies are well established with a long tradition of products, customers and markets, and a potentially strong internal culture. They are not start-ups in a greenfield. More work is needed (as indicated in Table ) to help established companies avoid the potential hurdles and manage the risks of moving to a more sustainable circular state.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abbey, J. D., J. D. Blackburn, and V. D. R. Guide, Jr. 2015. “Optimal Pricing for new and Remanufactured Products.” Journal of Operations Management 36: 130–146. doi: 10.1016/j.jom.2015.03.007

- Abbey, J. D., R. Kleber, G. C. Souza, and G. Voigt. 2017. “The Role of Perceived Quality Risk in Pricing Remanufactured Products.” Production and Operations Management 26 (1): 100–115. doi: 10.1111/poms.12628

- Agrawal, V. V., A. Atasu, and S. Ülkü. 2016. “Modular Upgradability in Consumer Electronics: Economic and Environmental Implications.” Journal of Industrial Ecology 20 (5): 1018–1024. doi: 10.1111/jiec.12360

- Agrawal, V. V., A. Atasu, and L. N. Van Wassenhove. 2019. “OM Forum – new Opportunities for Operations Management Research in Sustainability.” Manufacturing & Service Operations Management 21 (1): 1–12. doi: 10.1287/msom.2017.0699

- Agrawal, V. V., and S. Ülkü. 2013. “The Role of Modular Upgradability as a Green Design Strategy.” Manufacturing and Service Operations Management 15 (4): 640–648. doi: 10.1287/msom.1120.0396

- Atasu, A., V. D. R. Guide, and L. N. Van Wassenhove. 2008. “Product Reuse Economics in Closed-Loop Supply Chain Research.” Production and Operations Management 17 (5): 483–496. doi: 10.3401/poms.1080.0051

- Devoldere, T., W. Dewulf, B. Willems, and J. R. Duflou. 2009. “The Ecoefficiency of Reuse Centres Critically Explored – the Washing Machine Case.” International Journal of Sustainable Manufacturing 1 (3): 265–285. doi: 10.1504/IJSM.2009.023974

- EC. 2018. “Circular Economy: implementation of the Circular Economy Action Plan”. European Commission. Accessed February 19 2018. http://ec.europa.eu/environment/circular-economy/index_en.htm.

- EMF. 2013a. Towards the Circular Economy: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition. Cowes: Ellen MacArthur Foundation.

- EMF. 2013b. Towards the Circular Economy: Accelerating the Scale-up Across Global Supply Chains. Cowes: Ellen MacArthur Foundation.

- Geyer, R., L. N. Van Wassenhove, and A. Atasu. 2007. “The Economics of Remanufacturing Under Limited Component Durability and Finite Product Life Cycles.” Management Science 53 (1): 88–100. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.1060.0600

- Gonzalez, E. D. R. S., L. Koh, and J. Leung. 2019. “Towards a Circular Economy Production System: Trends and Challenges for Operations Management.” International Journal of Production Research 57 (23): 7209–7218. doi: 10.1080/00207543.2019.1656844

- Guide, V. D. R., and J. Li. 2010. “The Potential for Cannibalization of New Products Sales by Remanufactured Products.” Decision Sciences 41 (3): 547–572. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5915.2010.00280.x

- Guide, V. D. R., R. H. Teunter, and L. N. Van Wassenhove. 2003. “Matching Demand and Supply to Maximize Profits From Remanufacturing.” Manufacturing and Service Operations Management 5 (4): 303–316. doi: 10.1287/msom.5.4.303.24883

- Guide, V. D. R., and L. N. Van Wassenhove. 2007. “Dancing with the Devil: Partnering with Industry but Publishing in Academia.” Decision Sciences 38 (4 ): 531–546. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5915.2007.00169.x

- Guide, V. D. R., and L. N. Van Wassenhove. 2009. “OR Forum – the Evolution of Closed-Loop Supply Chain Research.” Operations Research 57 (1): 10–18. doi: 10.1287/opre.1080.0628

- Kirchherr, J., L. Piscicelli, R. Bour, E. Kostense-Smit, J. Muller, A. Huibrechtse-Truijens, and M. Hekkert. 2018. “Barriers to the Circular Economy: Evidence From the European Union (EU).” Ecological Economics 150: 264–272. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2018.04.028

- Kirchherr, J., D. Reike, and M. Hekkert. 2017. “Conceptualizing the Circular Economy: An Analysis of 114 Definitions.” Resources, Conservation and Recycling 127: 221–232. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2017.09.005

- McKinsey. 2016. “The circular economy: Moving from theory to practice” Accessed February 6, 2018. https://www.mckinsey.com/∼/media/McKinsey/Business%20Functions/Sustainability%20and%20Resource%20Productivity/Our%20Insights/The%20circular%20economy%20Moving%20from%20theory%20to%20practice/The%20circular%20economy%20Moving%20from%20theory%20to%20practice.ashx

- Murray, A., K. Skene, and K. Haynes. 2017. “The Circular Economy: An Interdisciplinary Exploration of the Concept and Application in a Global Context.” Journal of Business Ethics 140 (3): 369–380. doi: 10.1007/s10551-015-2693-2

- O’Connell, M. W., S. W. Hickey, and C. Fitzpatrick. 2013. “Evaluating the Sustainability Potential of a White Goods Refurbishment Program.” Sustainability Science 8: 529–541. doi: 10.1007/s11625-012-0194-0

- Oraipoulos, N., M. E. Ferguson, and L. B. Toktay. 2012. “Relicensing as a Secondary Market Strategy.” Management Science 58 (5): 1022–1037. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.1110.1456

- ResCoM. 2013. “Resource Conservative Manufacturing – transforming Waste into High Value Resource Through Closed-Loop Product System”. Accessed February 19 2018. https://cordis.europa.eu/project/rcn/110890_en.html.

- Simpson, D., J. Meredith, K. Boyer, D. Dilts, L. M. Ellram, and G. Keong Leong. 2015. “Professional, Research, and Publishing Trends in Operations and Supply Chain Management.” Journal of Supply Chain Management 51 (3): 87–100. doi: 10.1111/jscm.12078

- Souza, G. C. 2013. “Closed-loop Supply Chains: A Critical Review, and Future Research.” Decision Science 44 (1): 7–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5915.2012.00394.x

- Van Loon, P., C. Delagarde, and L. N. Van Wassenhove. 2018. “The Role of Second-Hand Markets in Circular Business: A Simple Model for Leasing Versus Selling Consumer Products.” International Journal of Production Research 56 (1–2): 960–973. doi: 10.1080/00207543.2017.1398429

- van loon, P., C. Delagarde, L. N. Van Wassenhove, and A. Mihelic. 2020. “Leasing or Buying White Goods: Comparing Manufacturer Profitability Versus Cost to Consumer.” International Journal of Production Research 58 (4): 1092–1106. doi: 10.1080/00207543.2019.1612962

- Van Loon, P., and N. Van Wassenhove. 2018. “Assessing the Economic and Environmental Impact of Remanufacturing: a Decision Support Tool for OEM Suppliers.” International Journal of Production Research 56 (4): 1662–1674. doi: 10.1080/00207543.2017.1367107

- Voss, C., N. Tsikriktsis, and M. Frohlich. 2002. “Case Research in Operations Management.” International Journal of Operations and Production Management 22 (2): 195–219. doi: 10.1108/01443570210414329

- Waldman, M. 2003. “Durable Goods Theory for Real World Markets.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 17 (1): 131–154. doi: 10.1257/089533003321164985

- Yin, R. K. 1981. “The Case Study as a Serious Research Strategy.” Knowledge: Creation, Diffusion and Utilization 3 (1): 97–114. doi: 10.1177/107554708100300106