Abstract

The customer order decoupling point (CODP) is the point in the supply chain where the product is linked to a customer order and is, by definition, the last stock point along the supply chain. The CODP decouples the upstream operations that are made to stock from the downstream operations that are triggered by customer orders. We employed a systematic literature review of the empirical research on the CODP in operations and supply chain management (OSCM). We identified 40 articles that explicitly contributed with empirical results concerning factors and characteristics for the operations upstream versus downstream of the CODP, or between make-to-stock (MTS) and make-to-order (MTO) operations. The 32 factors that were identified were grouped into four main categories: market and product factors, operations factors, supply chain factors, and performance measures. Based on the content analysis, we propose a framework that provides a holistic view on the CODP. The distinctive differences between MTS and MTO characteristics strongly suggest that there are two configurations: one for the upstream MTS-type operations and another for the downstream MTO-type operations. We discuss implications for research and practice and provide suggestions for further research.

1. Introduction

The early works by Sharman (Citation1984) and Hoekstra and Romme (Citation1992) established the customer order decoupling point (CODP) as a strategically important variable that determines significant parts of an organisation’s structure. It should be recognised that Sharman (Citation1984) and later Olhager (Citation2003) used the term order penetration point, which is equivalent to the CODP; we use the term CODP in this article. Sharman (Citation1984) described it as ‘ … the one key variable in every logistics configuration … ’ (75), and Hoekstra and Romme (Citation1992) stated that ‘[t]he selection of the location of the decoupling point is decisive when determining the organizational structure, including the logistic organization, and the type of (unavoidable) risks one is willing to accept within the company’ (8). The CODP is the point in the supply chain material flow at which a specific product becomes associated with a specific customer order (Hoekstra and Romme Citation1992; Sharman Citation1984). The CODP is the last stock point along the supply chain (Sharman Citation1984), and divides the supply chain into two sections. The operations upstream of the CODP focus on replenishing the stock point at the CODP and can therefore be characterised as make-to-stock (MTS) operations, while the operations downstream of the CODP focus on customer order fulfilment and can therefore be characterised as make-to-order (MTO) operations (Olhager Citation2003). The CODP is also the most important stock point along the supply chain since the deliveries of finished goods to customers rely on the availability of all items that are strategically stocked at the CODP (i.e. the right mix of items and in sufficient volumes), irrespective of where the CODP is positioned.

Despite the importance of the CODP, we have only identified three literature reviews related to the CODP published in peer-reviewed journals: Soman, van Donk, and Gaalman (Citation2004), Peeters and Van Ooijen (Citation2020), and Tiedemann (Citation2020). Soman, van Donk, and Gaalman (Citation2004) developed an MTO-MTS production planning and control framework for the food processing industry, Peeters and Van Ooijen (Citation2020) developed a taxonomy for hybrid production control systems, and Tiedemann (Citation2020) developed a conceptual model for demand-driven supply chain operation management strategies. Olhager and Prajogo (Citation2012), van Donk and van Doorne (Citation2016) and Tiedemann (Citation2020) have stressed that the CODP is an important contingency factor for operations and supply chain research and since there are no available reviews of empirical research on the CODP published in peer-reviewed journals, we feel that it is both important and timely to conduct a systematic literature review (SLR) of empirical research on the role of the CODP in the operations and supply chain management (OSCM) area. By reviewing empirical results regarding factors and characteristics associated with operations upstream versus downstream the CODP, as well as for MTS versus MTO operations, we aim to contribute to a higher-level understanding of key perspectives on the CODP in practice. We focus our study on empirical research on real-life evidence of the characterising features and differences between the operations upstream and downstream of the CODP and between MTO and MTS operations. We refer to ‘empirical research’ as defined by Flynn et al. (Citation1990): ‘The term “empirical”, which means “knowledge based on real world observations or experiment”, is used here to describe field-based research which uses data gathered from naturally occurring situations or experiments, rather than via laboratory or simulation studies … ’ (251). Given this background, the objectives of this study are to:

review the empirical research literature on the CODP, as well as MTS vs. MTO, to identify factors and distinguishing characteristics, and develop a classification scheme based on previous scholarly works.

propose a framework that captures factors, characteristics, and multiple perspectives on the CODP (upstream versus downstream the CODP) and MTS versus MTO.

identify suggestions for further research.

Reviewing empirical, real-life results regarding the CODP adds practical relevance to the review, as the results provide an overview of factors that affect, are associated with, or are affected by the CODP position.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. After defining the concept of the CODP, we present the method of the SLR in terms of search strategy, content analysis process, and descriptive statistics. Second, we present the results that emerged from the content analysis. The factors are grouped logically into four categories, capturing the characteristics of (i) markets and products, (ii) operations, (iii) supply chain, and (iv) performance. Third, we synthesise the findings into a framework that provides a holistic view on the CODP based on the collective empirical knowledge on the differentiating characteristics of MTS versus MTO and upstream vs. downstream operations around the CODP. Finally, we discuss managerial and research implications and limitations, and propose some suggestions for further research. Thus, this SLR contributes with two forms of synthesis (Post et al. Citation2020): a framework and research suggestions. This is the first study to combine the empirical findings from extant research articles into a broad framework that explicates how MTS-type operations upstream of the CODP differ from MTO-type operations downstream of the CODP. Since the framework is built up by empirical findings, it provides a concise overview of factors that are of practical relevance for discussions on the CODP and MTS versus MTO.

2. The CODP, MTO and MTS

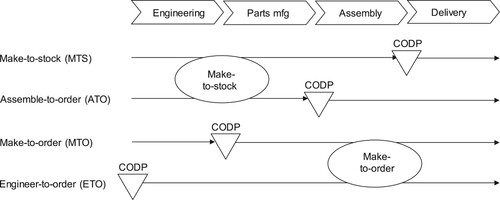

There are four basic alternatives for positioning the CODP along the material flow: make to stock (MTS), assemble to order (ATO), make to order (MTO), and engineer to order (ETO), which are illustrated in Figure . In MTS, the finished goods are stocked at the plant or in the distribution system and ready for immediate delivery once a customer order is received. ATO implies that there is an internal CODP that divides the internal material flow into two sections, with MTS-type operations for parts manufacturing upstream of the CODP and MTO-type operations for the assembly of finished goods downstream of the CODP. In MTO, all manufacturing and assembly operations are driven by customer orders. Finally, ETO implies that the customer can influence the entire product design, and, in addition, some items are typically purchased to order. ETO functions as MTO from a material flow perspective since all manufacturing and assembly activities must be performed while the customer is waiting.

Figure 1. The four basic alternatives for positioning the CODP, with MTS-type operations upstream of the CODP and MTO-type operations downstream of the CODP (based on Olhager Citation2003).

Thus, the two core parts of a supply chain are MTS and MTO operations, as illustrated in Figure ; the characteristics for MTS are the same as for upstream operations, and the corresponding holds for MTO and downstream operations. The ATO situation can be used to exemplify this reasoning: in an MTS situation, the customer order enters at the finished goods inventory and potentially triggers a replenishment order. The very same situation holds for the upstream part in the ATO case; the customer order enters the internal stock point, from where replenishment orders are triggered. Thus, the upstream part (in an ATO situation) reacts in the same way as the pure MTS situation when a customer order arrives. Hence, it is reasonable to conclude that the upstream part has the same set of characteristics as the MTS situation. This implies that the empirical research on the CODP, on one hand, and MTS vs. MTO, on the other hand, are complementary and both add to the same body of knowledge.

3. Research method

The purpose of this SLR is to summarise the state of the art of empirical research on the CODP and MTS vs. MTO, with relevance for OSCM. Conducting a literature review can help attain a comprehensive and novel understanding of the area and enable the identification of further beneficial research opportunities (Denyer and Tranfield Citation2009; Seuring and Gold Citation2012). Furthermore, by synthesising insights gained from the review, a new perspective or point of view on the literature can potentially be developed (Elsbach and van Knippenberg Citation2020). This systematic, content-based literature review follows the general guidelines in Tranfield, Denyer, and Smart (Citation2003), Denyer and Tranfield (Citation2009), Seuring and Gold (Citation2012), and Xiao and Watson (Citation2019). In the following sub-sections, we detail the search strategy and content analysis process, before presenting some descriptive statistics on the characteristics of the literature sources.

3.1. Search strategy

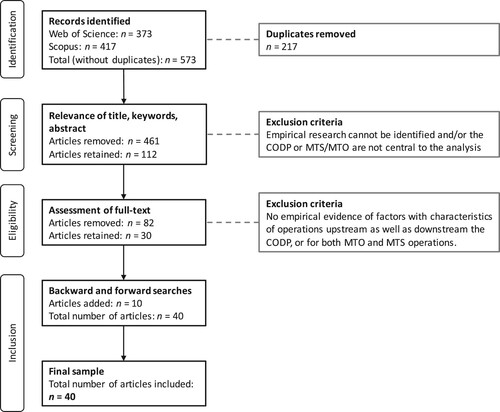

The search strategy was based on two selected databases (Web of Science and Scopus), which were considered the most relevant databases since we limited the search to peer-reviewed papers in high-quality, English-speaking journals. The search string was tailored to the objectives of this study: (‘decoupling point’ OR ‘penetration point’ OR ‘point of differentiation’ OR (make-to-stock AND (make-to-order OR assemble-to-order OR mix-to-order OR engineer-to-order OR build-to-order OR configure-to-order)) OR (‘make to stock’ AND (‘make to order’ OR ‘assemble to order’ OR ‘mix to order’ OR ‘engineer to order’ OR ‘build to order’ OR ‘configure to order’))) AND (operations OR production OR manufacturing OR ‘supply chain’). Thus, we include build-to-order (BTO) as well as configure-to-order (CTO) that are considered to be similar to ATO but are used in some literature, and we use both the hyphenated and unhyphenated versions of the search terms, such as make-to-stock as well as make to stock. The search strategy was applied to the title, abstract, and keywords. Only peer-reviewed articles were selected, while no restrictions or cut-off points regarding year of publication were applied. A final update of the search was conducted in May 2023. The full search strategy is reported in Figure according to the PRISMA statement (Moher et al. Citation2009), and discussed below.

Figure 2. Literature search protocol, in terms of a PRISMA flow diagram (based on Moher et al. Citation2009).

After removing duplicates from the two databases, 573 papers were identified. While 217 articles were identified in both databases, Web of Science contributed with 156 articles (not identified in Scopus) and Scopus with 200 articles (not identified in Web of Science). Thus, the two databases are complementary. In the screening phase, the title, keywords, and abstracts were checked for relevance to the topic area, that is, explicitly discussing the CODP or the MTS–MTO spectrum in the context of operations or supply chains as a central part of the analysis, and utilisation of empirical research. Papers using mathematical modelling or simulation were retained only if they explicitly originated from a real case problem. These criteria brought the number of articles that were retained down to 112.

To further assess eligibility, the papers were read in their entirety to ensure that the empirical results included characterising features of both the upstream and downstream sides of the CODP, or both MTS and MTO operations. Research on only MTS or MTO does not reveal anything about the characteristics of the other. It is only when research explicitly includes and compares the characteristics of operations upstream and downstream of the CODP, or the characteristics of both MTS and MTO operations (e.g. comparing two production systems, one with MTS operations and one with MTO operations), that a researcher can identify differences and similarities between the two types of operations. After this stage, 30 papers remained. We then performed backward and forward searches to identify other relevant papers, which added ten papers. Thus, the final sample included 40 papers. Tranfield, Denyer, and Smart (Citation2003) stated that ‘only studies that meet all the inclusion criteria … and which manifest none of the exclusion criteria need be incorporated into the review. The strict criteria used … are linked to the desire to base reviews on the best-quality evidence’ (Tranfield, Denyer, and Smart Citation2003, p. 215). Hence, the strict use of our criteria limited the selection of articles to 40. Table provides an overview of these articles, distinguishing between those that were identified through the search string and those that were identified through the backward and forward search. Table includes author(s), year of publication, journal, methodology (including country, industry, and number of cases or respondents, if specified), as well as research focus.

Table 1. Overview of the articles in the systematic literature review.

3.2. Content analysis process

The purpose of a content analysis process is to identify, combine, organise, and categorise perspectives on a particular topic (Breslin and Gatrell Citation2023). First, each member of the research team read the sampled papers and analysed and classified the content of the articles in an Excel-based data extraction form, detailing many aspects of the papers, including general information about the source (author, title, journal, and publication year), factors that exhibit different characteristics upstream vs. downstream of the CODP, upstream (MTS) characteristics, downstream (MTO) characteristics, case research details (number of cases, country, and industry), survey research details (number of responses, country, and industry), and the core concept used as the point of departure in the research (CODP, MTS vs. MTO, leagility, postponement, etc.). The coding was inductive, that is, it was based on the data that emerged from the extraction process (Xiao and Watson Citation2019). Then, the researchers compared their findings and resolved any differences in interpretation through thorough discussions. The factors exhibiting different characteristics for upstream (MTS) and downstream (MTO) operations were successively grouped into second-order themes and subsequently into aggregate themes, as illustrated in the coding tree in the Appendix. The findings and interpretations were frequently discussed between the researchers to minimise errors and to provide a credible dataset, analysis, and synthesis. Thus, both researchers participated in all aspects of the content analysis. The categories (aggregate themes), sub-categories (second-order themes), and factors that emerged are presented in section 4 along with their characteristic features for upstream (MTS) vs. downstream (MTO) operations and references to their respective sources.

3.3. Literature over time and across journals

Table lists the articles in chronological order, albeit divided in two sections; first, the articles identified through the search string, and second, the articles from the backward and forward search. The first publication from 1992 is Berry and Hill (Citation1992). The 40 papers included in this review were distributed among 20 international scientific journals; see Table . Most papers are published in operations management journals. The journal with the highest number of publications is the International Journal of Production Research (8), followed by the International Journal of Production Economics (5), and the International Journal of Operations & Production Management (4). Together, these three journals account for 17 papers, or almost half the total number of papers in this review.

3.4. Research methodologies

Among the 40 included studies, there are 31 case studies (12 multiple case and 19 single case studies), seven survey studies, one action research study, and one Delphi study, see Table . In a general sense, the case research articles evaluated the CODP position qualitatively to solve some operational problem or improve the case firm’s ability to meet complex market demands; see, for example, D’Alessandro and Baveja (Citation2000) and Gaudenzi and Christopher (Citation2016). The problem-solving approach also applied to the action research methodology in O’Reilly, Kumar, and Adam (Citation2015). Table illustrates the wide range of products, industries, and countries that are represented among the case studies. Additionally, multiple industries were included in the multiple-case studies by Olhager and Rudberg (Citation2003), van Donk and van Doorne (Citation2016), Tiedemann, Wikner, and Johansson (Citation2021), Agrawal et al. (Citation2022), and Dittfeld, van Donk, and van Huet (Citation2022). Most case studies were concerned with manufacturing, while Rahimnia and Moghadasian (Citation2010) and Trentin (Citation2011) studied hospitals and logistics services, respectively. They discussed how the so-called back-office operations can be decoupled from the customer-facing front-office operations, in line with the distinction between operations upstream and downstream the CODP. This finding supports the claim that the CODP is an important concept regardless of the industrial context (Sharman Citation1984).

All the surveys sampled various industries and the data were gathered from a variety of countries. Prasad, Tata, and Madan (Citation2005) conducted a multinational study, albeit dominated by U.S. firms, while Koh, Gunasekaran, and Saad (Citation2005) and Koh and Simpson (Citation2007) surveyed UK firms, and Olhager and Selldin (Citation2007), Olhager and Prajogo (Citation2012), Mishra et al. (Citation2019), and Ojha et al. (Citation2021) collected data in Sweden, Australia, India, and the U.S., respectively. The seven surveys used the CODP in two different ways. Olhager and Selldin (Citation2007) and Mishra et al. (Citation2019) used a scale to capture the position of the CODP, while the other sources used a categorical division between MTS and MTO (or BTO) operations. A CODP scale can be used to test the CODP as a mediator between independent and dependent variables, while MTS and MTO sub-samples allows for a direct comparison between the two types of operations. Agrawal et al. (Citation2022) analysed quantitative data from a Delphi study to identify differences between MTS and MTO operations.

3.5. Core concepts

Ten articles dealt specifically with the CODP, and 20 articles dealt with MTS and MTO operations. Thus, no less than 75% (30 out of 40 articles) focused directly on the CODP or on MTS versus MTO. In the other articles, postponement and leagility were used as the point of departure, six and four articles, respectively. Postponement is the operational practice of delaying certain activities until a customer order is received. A shift of the CODP upstream leads to more postponement, moving toward MTO operations, while a shift of the CODP downstream leads to less postponement, implying a move toward MTS operations (Ferreira, Toledo, and Rodrigues Citation2021; Harrison and Skipworth Citation2008; Skipworth and Harrison Citation2006; Trentin Citation2011; Wong, Potter, and Naim Citation2011; Yeung et al. Citation2007). These sources discussed how the operations characteristics changed when increasing or decreasing the level of postponement for the section of the supply chain that was affected by the change. Leagility combines lean and agile approaches such that lean is applied upstream of the CODP and agility downstream of the CODP (Drake, Lee, and Hussain Citation2013; Gaudenzi and Christopher Citation2016; Krishnamurthy and Yauch Citation2007; Naylor, Naim, and Berry Citation1999). These sources discussed the characteristics for the operations upstream of the CODP versus those of the operations downstream of the CODP. The specific ways in which postponement and leagility relate to CODP and MTS vs. MTO in these sources are discussed in the results section.

4. Results and analysis

In the following sections, we present the results of the content analysis. The identification of factors and the logical grouping of these into second-order themes and subsequently into aggregate themes emerged from this analysis. The successive grouping of factors is illustrated in the coding tree in the Appendix. The following four distinctly different categories (aggregate themes) of factors were identified: (i) market and product characteristics, (ii) operations characteristics, (iii) supply chain characteristics, and (iv) performance. These four categories included eight, eleven, ten, and three factors, respectively. Thus, altogether, 32 factors were identified. Each category is discussed below in terms of factors, characteristics related to MTS and MTO operations, and the corresponding source(s). The MTS and MTO columns in Tables represent the characteristics for operations upstream and downstream of the CODP, respectively.

Table 2. Market and product factors and characteristics.

Table 3. Operations factors and characteristics.

Table 4. Supply chain factors and characteristics.

Table 5. Performance factors and characteristics.

4.1. Market and product factors and characteristics

The first aggregate theme that emerged from the content analysis was market and product characteristics. Table presents the eight different factors that were identified, the characteristics for MTS/upstream and MTO/downstream operations, and the sources for each factor. There are two main subcategories: market and product aspects. Market factors reflect how the products are received in the marketplace, while product factors relate to the offering of the firm to the market.

There is very strong support for MTO being a response to dynamic and volatile environments, while MTS is used in stable operating conditions. van Donk (Citation2001), Childerhouse, Aitken, and Towill (Citation2002), Perona, Saccani, and Zanoni (Citation2009), Olhager (Citation2010), and Ferreira, Toledo, and Rodrigues (Citation2021) all found that low and high demand uncertainty is associated with MTS (upstream) and MTO (downstream) operations, respectively. van Donk (Citation2001), Childerhouse, Aitken, and Towill (Citation2002), and Perona, Saccani, and Zanoni (Citation2009) discuss demand uncertainty relative to MTS vs. MTO, Olhager (Citation2010) discusses it upstream vs. downstream of the CODP, and Ferreira, Toledo, and Rodrigues (Citation2021) found that higher demand uncertainty drives more postponement, that is, moving the CODP upstream and increasing the MTO part of the supply chain.

Four other author groups identified that low and high demand variability leads to MTS (upstream) and MTO (downstream) operations, respectively. D’Alessandro and Baveja (Citation2000) and Soman, van Donk, and Gaalman (Citation2007) studied MTS vs. MTO operations, Skipworth and Harrison (Citation2006) analysed MTS vs. form postponement (essentially an ATO setup), and Wong, Potter, and Naim (Citation2011) found that higher levels of postponement – by moving the CODP upstream – reduced the demand variability of the items in the decoupling stock point.

Demand volume is an important factor in this context, and there is strong empirical evidence for high demand volumes being associated with MTS (upstream) operations, and low demand volumes being found in MTO (downstream) operations (Akkerman, van der Meer, and van Donk Citation2010; Berry and Hill Citation1992; Childerhouse, Aitken, and Towill Citation2002; D’Alessandro and Baveja Citation2000; Harrison and Skipworth Citation2008; Molina, Velandia, and Galeano Citation2007; Olhager and Rudberg Citation2003; Olhager and Selldin Citation2007; O’Reilly, Kumar, and Adam Citation2015; Perona, Saccani, and Zanoni Citation2009; Soman, van Donk, and Gaalman Citation2007).

Order qualifiers and winners, two additional market-related factors, reflect the internal perception of what the plant needs to do well to successfully meet customer preferences and serve its market. Qualifiers for MTS are quality, lead time, and customer service, while qualifiers for MTO are quality, lead time, and cost (Childerhouse, Aitken, and Towill Citation2002). Interestingly, quality and lead time appear as qualifiers for both MTS and MTO, reflecting that a certain level of quality (typically conformance to product specifications) and delivery dependability is required by customers regardless of the type of market and product (Hill and Hill Citation2009, 192). Childerhouse, Aitken, and Towill (Citation2002) are joined by five other case studies (Cannas et al. Citation2019; Drake, Lee, and Hussain Citation2013; Pereira, Oliveira, and Carravilla Citation2022; van der Vorst, van Dijk, and Beulens Citation2001; Yeung et al. Citation2007) in finding that the order winner is cost related for MTS and flexibility related for MTO. Thus, there is a strong agreement that the dominant order winners are cost for MTS and flexibility for MTO.

The product offering is also concerned with the interface between the market and the firm. The level of product standardisation versus customisation is mentioned by no less than 17 sources (see Table ) as an important factor influencing the choice of the CODP position, such that standard, generic products are produced to stock, while customised products are produced to customer order.

Product variety, or the width of the product range, is a related factor, where MTS is associated with low variety and MTO with high variety (Berry and Hill Citation1992; Ferreira, Toledo, and Rodrigues Citation2021; Skipworth and Harrison Citation2006). Skipworth and Harrison (Citation2006) and Ferreira, Toledo, and Rodrigues (Citation2021) discussed both product variety and standardisation vs. customisation, suggesting that standard products imply low variety, and that customised products are similar to offering high variety. Finally, Soman, van Donk, and Gaalman (Citation2007) found that MTS should be avoided for highly perishable food products, instead requiring an MTO approach, while non-perishable food products were candidates for MTS.

4.2. Operations factors and characteristics

The second aggregate theme that emerged from the content analysis was operations. Table presents the factors, the characteristics for MTS/upstream and MTO/downstream operations, and the sources for each factor. Eleven different factors were identified, and further divided into four main subcategories of operations response (to market and product factors), production process, operations design, and planning and control system.

The first sub-category includes factors that act as the operations response to market and product factors. Production volume per individual item is a direct consequence of demand volume per individual item (Berry and Hill Citation1992) such that high demand volumes translate into high production volumes for MTS items, while low demand volumes translate into low production volumes for MTO items. Lead time is strongly related to offering well-defined standard products vs. customised products (D’Alessandro and Baveja Citation2000; Olhager and Selldin Citation2007). Standard products that are made to stock have short delivery lead times by design (i.e. MTS items), but can also have short production lead times, while customised products that are made to order may have very long production and delivery lead times (Olhager and Selldin Citation2007), driven by the production steps that require customisation. Finally, forecast accuracy is directly related to demand uncertainty (van Kampen and van Donk Citation2014; Wong, Potter, and Naim Citation2011). High demand uncertainty typically implies low forecast accuracy, which favours MTO, while low demand uncertainty can be forecasted with good accuracy, which allows for MTS with small safety stocks.

The production process can be characterised by the process type, the setup times, and the level of process flexibility. Olhager (Citation2010) found that the process used upstream of the CODP was of assembly line type, while a job shop type process was used downstream of the CODP, i.e. applying a higher level of process flow orientation upstream than downstream. Soman, van Donk, and Gaalman (Citation2007) found that short setup times were a requirement for MTO, while long setup times were associated with MTS products. Finally, Mishra et al. (Citation2019) found that MTS operations do not need manufacturing flexibility, while flexibility is important in MTO operations.

The third subcategory is concerned with operations design principles, that is, lean or agile operations, and forecast-driven or customer order-driven operations. All six sources on lean vs. agile – Naylor, Naim, and Berry (Citation1999), van der Vorst, van Dijk, and Beulens (Citation2001), Krishnamurthy and Yauch (Citation2007), Rahimnia and Moghadasian (Citation2010), Nieuwenhuis and Katsifou (Citation2015), and Gaudenzi and Christopher (Citation2016) – utilised the perspectives of decoupling or leagility and found that lean is applied upstream of the CODP and agile downstream, implying that lean is applicable to MTS and agile to MTO. van der Vorst, van Dijk, and Beulens (Citation2001) and Cannas et al. (Citation2019) used a decoupling perspective and noted that operations upstream of the CODP were forecast driven and that those downstream of the CODP were customer order driven, while Trentin (Citation2011) and Ferreira, Toledo, and Rodrigues (Citation2021) noted the same in a postponement context, stating that ‘the portion of the production process performed in a standardized manner being driven by demand forecasting, … the portion driven by customer orders occurring in a more customized manner’ (Ferreira, Toledo, and Rodrigues Citation2021, 17).

Finally, the planning and control system includes sales and operations planning (S&OP), inventory management, and materials planning. A level planning strategy for S&OP was used for MTS, while MTO requires a chase planning strategy for S&OP to avoid building inventory or excessive delivery lead-times (Olhager and Selldin Citation2007). O’Reilly, Kumar, and Adam (Citation2015) found that inventory management focused on the finished goods inventory in MTS operations, while the raw materials inventory (RMI) was the focus in MTO operations (since there is no inventory downstream of the RMI in MTO operations). MRP is the standard approach for MTO since it allows for time-phased planning of individual customer orders, while Kanban is appropriate for MTS, since it acts as a buffer replenishment system (Childerhouse, Aitken, and Towill Citation2002; Olhager Citation2010).

4.3. Supply chain factors and characteristics

The third theme that emerged from the content analysis was supply chain. The research papers typically focused on the core plant and its relationships with first tier suppliers and/or first tier customers when discussing supply chains. Table presents the factors, the characteristics for MTS/upstream and MTO/downstream operations, and the sources for each factor. Ten different factors were identified, grouped into three subcategories: supply chain-related, customer-related, and supplier-related factors. The factors have been treated in only one or two sources. Thus, there is limited empirical evidence on the differences between upstream and downstream operations from a broad supply chain perspective.

The supply chain sub-category includes factors that are concerned with the overall supply chain. The supply chain approaches originate from Fisher (Citation1997), who discussed the alignment between the supply chain strategy and the product characteristics, suggesting that a physically efficient supply chain is appropriate for functional products and that a market-responsive supply chain is appropriate for innovative products. The case company in Olhager (Citation2010) used a physically efficient supply chain upstream of the CODP (MTS-type operations) and a market-responsive supply chain downstream of the CODP (MTO-type operations), while Cannas et al. (Citation2019) identified reliability and efficiency as key dimensions upstream and flexibility downstream of the CODP. Olhager and Prajogo (Citation2012) found that lean practices and supply base reduction had a significant positive impact on business performance for MTS only, while external logistics integration exhibited a significant positive impact on business performance for MTO only. Thus, the ways to improve supply chain operations showed a significant difference for MTS and MTO firms. Demand amplification (from the customer and through the manufacturing stages) was not found for MTO but was always detected when manufacturing generic products to stock in the three cases in Harrison and Skipworth (Citation2008). Dittfeld, van Donk, and van Huet (Citation2022) found that MTS operations stressed redundancy as a risk mitigation strategy, while the need for agility was related to MTO operations. The findings in the Delphi study by Agrawal et al. (Citation2022) indicated that the perceptions on supply chain visibility (SCV) differed substantially between MTO and MTS, such that SCV was perceived as more feasible but less important for MTS, while it was more important but less feasible in MTO environments.

The customer-related sub-category contains two factors, for which the empirical results appear somewhat contradictory. Olhager and Rudberg (Citation2003) found that improvement initiatives taken through e-commerce, as a customer integration technology, had a strong positive effect on delivery performance in an MTO setting but no effect in the MTS situation. Contrary to this result, van Donk and van Doorne (Citation2016) found that MTS firms are integrating more intensely with their customers than MTO firms. This warrants more research into the role of the CODP in the relationship between customer integration and performance.

The supplier-related factors indicate that tight and flexible relationships with suppliers are needed for MTO firms, while MTS firms prefer loose coupling with reliable suppliers (Prasad, Tata, and Madan Citation2005; van Donk and van Doorne Citation2016). Dittfeld, van Donk, and van Huet (Citation2022) observed that MTO firms purchased customised parts, while MTS firms purchased generic raw materials, and that the latter used raw materials inventory as a means for resilience. Ojha et al. (Citation2021) found that the quality of information exchanged with suppliers was significantly related to enhanced flexibility performance for MTO firms but that it had no influence on supplier flexibility performance for MTS firms, arguing that less information exchange was needed in stable environments where supplier flexibility was not as crucial. These sources indicate that MTO operations engage much more with suppliers than MTS operations do.

4.4. Performance factors and characteristics

The fourth and final theme that emerged from the content analysis was performance measures, that is, the results of the operations and supply chain activities associated with the products delivered to the marketplace. Table presents the factors, the characteristics for MTS/upstream and MTO/downstream operations, and the sources for each factor.

It is notable that only cost and delivery performance were identified in the analysed literature as performance effects that differ between MTS and MTO operations. The identified cost element, inventory holding cost, is also very specific and not a measure of overall cost performance. In a case study from the food processing industry, Soman, van Donk, and Gaalman (Citation2007) found that items with high holding costs were also those that were highly perishable and customised and therefore made to order. Items with lower levels of perishability and low inventory holding costs were found to be stronger candidates for being made to stock.

A short delivery lead-time can be offered in an MTS situation, since the products are available in the finished goods inventory for instant supply to the market or customer. In MTO situations, the delivery lead-time tends to be longer since a number of production activities must be performed while the customer is waiting (see Figure ). This distinction is supported by the case study findings in D’Alessandro and Baveja (Citation2000), van Donk (Citation2001), Harrison and Skipworth (Citation2008), Hilletofth (Citation2009), and O’Reilly, Kumar, and Adam (Citation2015), as well as the survey results in Olhager and Selldin (Citation2007). The implications of various forms of uncertainty on on-time delivery (OTD) were investigated by Koh, Gunasekaran, and Saad (Citation2005) and Koh and Simpson (Citation2007). They found that there were few causes of and a low impact of uncertainties in MTS situations, while there were many causes of and a high impact of uncertainties in MTO situations, potentially leading to late product deliveries. It should be noted that they did not report on the OTD performance per se but focused on the implications of uncertainty on OTD performance.

Other measures that reflect operational performance typically include quality (in terms of conformance to specifications) and flexibility (typically volume and product mix flexibility). Quality is typically considered an order qualifier for all types of operations (Hill and Hill Citation2009) and should therefore not appear as significantly different. However, the importance of different forms of flexibility ought to differ between MTS and MTO since MTS requires very little flexibility with respect to its stable conditions and focus on cost, while MTO operations can benefit from flexibility of various forms – as suggested by several factors in Tables . These include (i) order winners (cost for MTS and flexibility for MTO), (ii) process flexibility (low levels for MTS and high levels for MTO), (iii) operations concept (lean for MTS and agile for MTO), (iv) supply chain strategy (physically efficient and reliable for MTS and market-responsive and flexible for MTO), and (v) supplier flexibility (weak and strong effect of information quality on supplier flexibility for MTS and MTO, respectively). Thus, there is strong support for the notion that MTS operations ought to be performing well on costs and MTO operations on flexibility. However, this does not show up in the empirical research on CODP and MTS versus MTO to date.

5. Discussion

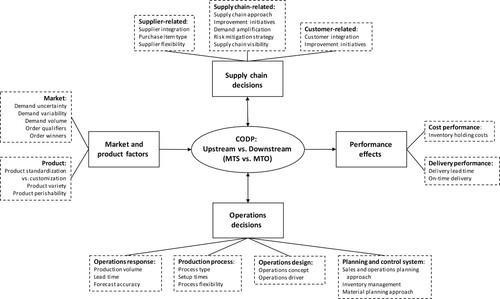

In this section, we propose and discuss a framework, based on the empirical evidence of differences between operations upstream and downstream of the CODP, before discussing research and managerial implications.

5.1. Framework

This SLR identified factors that have distinctly different characteristics for operations upstream and downstream of the CODP, or, alternatively stated, differences between MTS and MTO. These factors are related to (i) market and product characteristics, (ii) operations characteristics, (iii) supply chain characteristics, and (iv) performance effects. The framework in Figure includes the categories, subcategories, and factors.

Figure 3. Framework illustrating the relationships between the categories with key differences between operations upstream and downstream of the CODP (or between MTS and MTO); see Tables for the different characteristics.

The factors that influence the choice of CODP position are found on the left-hand side in Figure . The market factors concern the nature of demand, in terms of volume, variability, and uncertainty, as well as the order qualifiers and winners and must be considered closely when deciding on a CODP position. The same holds for the type of product that the firm offers to the market. It is important to consider the extent to which one will allow customers to customise products, since order-specific customisation can only be available if some operations are left until the customer has expressed his or her preferences.

Next, we turn to the operations factors. The operations response factors are closely related to demand volume and uncertainty, strongly influencing production volume, lead time, and forecast accuracy. Production volume is a direct consequence of demand volume, and lead time is greatly influenced by the choice of offering well-defined standard products or customised products. Forecast accuracy is directly related to demand uncertainty. Low demand uncertainty can translate into high forecast accuracy, which allows for holding products in inventory without excessive safety stocks. However, high demand uncertainty may prohibit keeping products in inventory, forcing these to be offered as customer order goods. The operations designs are very different for MTS and MTO operations. A lean approach is used for the forecast-driven operations in MTS and upstream of the CODP, while agility is used for the customer order-driven operations in MTO and downstream of the CODP. The production process must be considered when deciding on the CODP position unless a new production system is to be set up for a new product or product family. If the product, for which the CODP is to be decided is supposed to be produced in an existing production system, the characteristics of this production system will constrain the positioning of the CODP. For example, a continuous process in a process industry plant implies that the CODP must be positioned either before the process or after the process, but not inside the process, since such processes cannot have an internal inventory position by design. Alternatively, if a new product family is introduced that would require a new production system to be designed, there are more degrees of freedom in deciding the CODP position. Finally, the planning and control systems for MTS and MTO operations are designed differently. MTS uses a level planning strategy for S&OP, focuses inventory management on the finished goods inventory, and uses Kanban for materials planning, which resonates well with high-volume, standard products. MTO uses a chase planning strategy for S&OP, focuses inventory management on the raw materials, and uses MRP for materials planning, instead, which is needed for low volume, highly customised products.

The supply chain factors concern general supply chain perspectives as well as specific relationships with customers and suppliers. Upstream of the CODP, a physically efficient and reliable supply chain is advocated, with improvement opportunities through internal lean practices and supplier rationalisation, and risk mitigation through redundancy, while a market-responsive and flexible supply chain is needed downstream of the CODP, with improvement potential through external logistics integration, and agility for risk mitigation. The customer-related aspects suggest that while customer integration is low for MTO, increasing levels of customer integration can positively impact delivery lead time, whereas the reverse perspectives hold for MTS (i.e. high customer integration but no impact on delivery lead time). The supplier-related aspects indicate that tight coupling, customised purchase items, and a strong relationship between information quality and supplier flexibility are vital for MTO, while loose coupling, generic purchase items, and no effect of information quality on supplier flexibility are found for MTS. The latter finding is probably related to the notion that producing high-volume standard products to stock implies that purchase components and raw materials are standardised such that suppliers do not need to be flexible.

Finally, on the right-hand side in Figure , we have only three performance indicators, which is surprisingly few given that 40 empirical papers were reviewed. MTS is associated with items with low inventory holding costs and with quick and reliable deliveries to customers from finished goods inventory. Finished goods inventories of items with high inventory holding costs should be avoided in MTO, but the customisation of the product to customer order will imply longer and more variable delivery lead times.

The framework, considered in its entirety, also adds a dimension by illustrating how the identified factors interact through the CODP, or the MTS–MTO choice. As the identified market and product factors influence where the CODP ought to be positioned, and the CODP position of a product influences choices regarding operations and the supply chain, it appears that the CODP position functions as a key link between, on the one hand, market and product factors and on the other hand, appropriate operations and supply chain designs.

5.2. Research implications

The findings from this study have implications for researchers. This review complements the two previous reviews on mathematical models for hybrid MTS/MTO production control (i.e. Peeters and Van Ooijen Citation2020; Soman, van Donk, and Gaalman Citation2004) in that we reviewed empirical findings from case and survey research describing the differences (and similarities) between MTS (upstream of the CODP) and MTO (downstream of the CODP).

A key finding is that there is a multitude of factors that exhibit distinctly different characteristics for the upstream (MTS) versus downstream (MTO) parts of the supply chain. The categories, subcategories, and factors are included in the framework in Figure , while the differentiating characteristics for the upstream vs. downstream parts are detailed in Tables , with the accompanying discussion. The characteristics for MTS seem to be internally coherent: that is, high demand volume, low demand uncertainty, standard products, lean operations, and a physically efficient supply chain. MTO represents another set of internally coherent characteristics, such as low demand volume per item, high demand uncertainty, customised products, agile operations, and a market-responsive supply chain. This finding strongly suggests that there are two configurations: one for the upstream, MTS-type operations and another for the downstream, MTO-type operations. Configurations have been described as ‘multidimensional constellations of conceptually distinct characteristics that commonly occur together’ (Meyer, Tsui, and Hinings Citation1993, 1175), and ‘commonly occurring clusters of attributes or relationships … that are internally cohesive’ (Miller and Friesen Citation1984, 12). Configuration theory thus describes an organisation as a set of interrelated activities and is ‘very useful in handling the coalignment or fit among multiple variables … and it is appropriate for handling complex relationships’ (Flynn, Huo, and Zhao Citation2010, 61). The CODP dictates aspects of how operations and supply chains ought to be designed, and if this is done successfully, one may realise the intended performance effects. It is not the CODP position per se that leads to higher or lower levels of performance in general but rather how the operations and supply chains are designed and managed for the MTS and MTO parts of the supply chain.

This resonates well with the concept of equifinality that argues that there are multiple, equally effective ways in which an organisation can achieve environmental or internal fit (Gresov and Drazin Citation1997), and where the configuration approach views fit in terms of ‘gestalts’ or configurations of various elements and their relationships (Drazin and Van de Ven Citation1985). For example, since cost dominates the order winning criteria for MTS operations, the design and management of operations and supply chains should be cost-conscious and subsequently lead to high levels of cost performance. The reverse holds for MTO operations in that flexibility dominates the order winning criteria such that operations and supply chains should be designed and managed from a flexibility perspective, leading to high levels of flexibility performance. If a particular CODP position would lead to the best overall performance – ceteris paribus – then all firms would choose this position for all products. Obviously, this would be a false notion.

The framework depicted here describes only three performance measures: inventory holding cost, delivery lead time, and OTD. Quality (in terms of conformance to specifications) is typically an order qualifier for all firms and industries, and therefore performance should not be distinctly different between MTO and MTS firms. However, it could be expected that more general performance measures related to manufacturing and supply chain costs and flexibility would exhibit a difference between the MTO and MTS settings since cost is a typical order winner for MTS, while the order winner(s) for MTO tends to be related to flexibility. The fact that it is rare to find such a distinction between MTO and MTS when it comes to performance is perhaps due to the common practice of using relative performance scales in the OSCM field in survey research, either asking the respondent to rate performance in relation to its competitors or grading how much one agrees with a statement regarding performance; see Olhager and Prajogo (Citation2012), Mishra et al. (Citation2019), and Ojha et al. (Citation2021) for examples of this. When asked to rate performance relative to competitors, it is plausible that respondents will relate to competitors making products with a similar CODP position. This could explain why there are so few distinct performance differences between MTS and MTO environments reported in the literature.

The many differences between MTO and MTS operations convey a strong message for survey research. If a survey includes factors that most likely are different for MTO and MTS operations and uses a cross-sectional sample (which most likely contains both MTO and MTS plants), then the survey must consider the CODP explicitly. This implies that the survey must include questions on the CODP position, such that the researcher can use the continuum from ETO to MTS as a variable, or create two or more subsamples representing specific CODP position, such as MTS and MTO. If the CODP is not included, the results are over-generalized across all types of plants and may not be representative of the true result for any of the two configurations. Olhager and Prajogo (Citation2012) noted that the effects for the whole sample did not translate to the corresponding effect for MTO or MTS firms concerning lean practices, external logistics integration, and supplier rationalisation. Our findings suggest that there are potentially many other factors that would require that the CODP is accounted for to avoid erroneous conclusions based on an over-generalisation across the sample.

The existing literature does not discuss how operations and supply chain factors are related. There is most likely some kind of dependency since both operations and supply chain factors should be aligned to the CODP position, with different configurations upstream vs. downstream. The order in which these factors are addressed reflects the strategic process of the firm, that is, whether the strategies are developed ‘inside out’ (first internal operations, and then the external supply chain) or ‘outside in’ (first the overall supply chain, and then the internal operations as part of the supply chain), which can be addressed in further research.

5.3. Managerial implications

The CODP framework can be used by practitioners as a guide to which factors to consider when setting CODP positions for new products or when reviewing the appropriateness of the current set of CODP positions for existing products. It is important to recognise and appreciate the multitude of different aspects that influence the strategic positioning of the CODP and the many consequences that follow with this decision. We propose that all four categories – market and product factors, operations factors, supply chain factors, and performance factors – should be investigated for any discussion related to the strategic positioning of the CODP. Some factors influence the strategic decision of the CODP position, while others are typical characteristics associated with the choice of either MTS-type operations (upstream of the CODP) or MTO-type operations (downstream of the CODP).

ATO plants have a particular challenge in that the internal supply chain parts upstream and downstream the CODP should be designed and managed in very different ways. The part of the internal supply chain upstream of the CODP should resemble MTS-type operations, while the part downstream of the CODP should have the character of MTO-type operations (see Figure ). Hence, it is crucial that these two parts are indeed designed and managed differently, and here the framework and Tables can provide guidelines. The CODP ties the two parts together since the role of the upstream operations is to replenish the CODP stock point, and the MTO operations rely on the availability of all items that are strategically stocked at the CODP.

The operations and supply chain factors can take on two different roles. If an entirely new operations and supply chain system is to be designed for a new set of products, the factors in the framework should be included in the decision on MTS versus MTO products or on the positioning of the CODP and be designed accordingly. However, if changes are being made within an existing system, for example when moving the CODP for products, the plant may decide that some operations and supply chain characteristics shall remain the way they are and cannot be changed (for example, for investment reasons), which will influence the decision on the CODP. Such decisions will limit the set of factors that can be designed in alignment with the characteristics of the product and hence constrain the likely performance potential. If items are to be mixed in a single operations system – that is, some MTS items and some MTO items – the managers must acknowledge that such a decision will create operational problems. None of the items will have the best support for its own order winners from the system, and it is likely that there will be constant prioritisation issues between the two item categories. Two options are available. From a strategic perspective, it would be most appropriate to reconsider the CODP positions for all items in the same production system to try to align these to a single decoupling point, and thus remove the tensions between items. If this is not possible, operational production control models for hybrid systems come into play (Peeters and Van Ooijen Citation2020; Soman, van Donk, and Gaalman Citation2004).

The strength of the framework is that all the factors that have contrasted the characteristics for upstream MTS and downstream MTO operations stem from empirical evidence. Many different industries have been investigated in the 40 papers included in this review, which provides evidence of the general applicability of the CODP concept. However, some of the 32 factors identified in this research may be more relevant for some industries than for others. A thorough understanding of the peculiarities of the specific situation is necessary to position the CODP optimally. Nevertheless, the framework can aid such discussions. In fact, the framework encourages an assessment of the current situation for the firm or plant; all relevant factors related to the market and product characteristics, manufacturing operations, and supply chains require explicit consideration. If some characteristics do not align with the expectations according to the configurations for MTS vs. MTO, such mismatches and the corresponding reasons should be analysed.

6. Conclusions, limitations, and further research

We have provided an SLR that investigated the CODP in empirical OSCM research. Given the limited number of papers that met our inclusion criteria, it is fair to say that the CODP is rarely explicitly and extensively investigated in empirical research in the OSCM area. However, when included, it has often proved to contribute to the research with perspectives that are significant. This begs the question of why the CODP is not considered more frequently. One reason could be that a single firm (or plant) often manufactures and sells products with different CODPs, making it very difficult to classify the firm (or plant) as either pure MTS or pure MTO. In case research, when one looks specifically at a certain process or product, it is, in some sense, natural that the analysis does not compare different CODP positions. In survey research, the CODP would need consideration already at the questionnaire design stage. In the seven surveys that were included in this review, the researchers had included the CODP in one of two different ways, that is, either as a CODP scale or as MTO and MTS subsamples, and this choice must be matched to the type of analysis intended.

Through our analysis of the literature, we identified 32 factors and grouped them thematically into four categories (and eleven subcategories) that provide an overview of CODP-related characteristics; the differentiating characteristics for the upstream vs. downstream parts are detailed in Tables . The framework presented in section 5 provides an overview of how these categories of factors relate to the CODP. Our findings indicate that considering the CODP explicitly is of high practical relevance as many aspects of OSCM differ between operations upstream and downstream of the CODP. The novelty of this study lies in that it synthesises empirical findings from 40 research articles that together provide a broad view on how MTS-type operations upstream of the CODP differ from MTO-type operations downstream of the CODP. Hence, the study provides empirical evidence on these differences and the combined insights from these 40 papers suggest that there are distinct configurations for MTS and MTO operations.

6.1. Limitations

Our search strategy may have missed some references related to the CODP with respect to the selection of keywords and since we limited the search to articles in English. However, as countermeasures, we used (i) two well-cited databases (Scopus and Web of Science) and (ii) backward and forward search to identify other relevant papers. The articles in this SLR were drawn from highly ranked international scientific journals, which added credibility to the selection process. Because of potentially missing some references, we may have missed some additional factors that exhibit significant differences between MTS and MTO or the supply chain sections upstream and downstream of the CODP. Hence, we cannot claim that the CODP framework provides a complete view of factors relevant to the CODP, but the framework does provide a broad range of empirical evidence on the important implications of the CODP for OSCM. We acknowledge that the support from literature sources for the factors in the framework vary considerably, in terms of the number of references and over time. Tables shows that the range of supporting sources vary from one to 17 (for standard versus customised products). Some factors with limited empirical support may be specific to its industry; for example, there are a few factors that refer to the food industry where the issue of perishability may affect the generalisability of these factors. Some factors have strong empirical support over many years, and the meaning of terms has not changed. New factors and characteristics have been added over time, which have helped to provide a richer picture. Some of the new aspects have not yet received additional empirical support, but this is probably only a matter of time.

6.2. Suggestions for further research

Based on the findings from this SLR, we have identified six areas that need further research attention. First, we identified 32 factors related to upstream and downstream aspects of the CODP, but we acknowledge that there may be additional factors that have distinctly different characteristics for upstream (MTS) and downstream (MTO) operations. These may even go beyond the four categories that we have identified. A complementary perspective is to identify those factors that do not differ between the two situations since our focus was on the differentiating characteristics.

Second, only three performance-related factors were identified. This is perhaps due to the use of perceptual, as opposed to actual, performance measures. Nevertheless, more examples of performance outcomes in both upstream (MTS) versus downstream (MTO) situations are welcome. Case research that can provide rich descriptions on actual performance in specific environmental situations, using specific operations and supply chain resources, is warranted.

Third, the framework in Figure lends itself to empirical survey testing. All categories and sub-categories can be converted to constructs, and the factors identified in this research can be transformed into survey items. We propose that further survey research ought to include all categories and many factors from this framework to allow for a test of the configurational approach, and potentially shed light on the ‘inside-out’ or ‘outside-in’ aspect for designing operations and supply chains.

Fourth, since the CODP can be operationalised in different ways – as MTO and MTS subsamples or as a continuous variable from ‘pure’ ETO to ‘pure’ MTS – the operationalisation of the CODP must be carefully considered in such models. More research is needed on this methodological issue regarding the implications of how the CODP is captured in survey research.

Fifth, an interesting aspect to consider for further survey research is to focus on ATO plants, that is, those that have an internal CODP. Such research would require a distinction between the upstream and downstream parts in its design so that appropriate variables and characteristics are identified for each. It would be most rewarding to broaden our understanding of how plants design and manage the operations upstream vs. downstream of the CODP, and how they plan for and implement changes in the CODP position – upstream or downstream. A related aspect is how plants act when they are faced with a mix of MTO and MTS items in the same production system. Empirical research is warranted on whether organisations make strategic reconsiderations of the CODP position for some products or apply production control systems developed for such hybrid production systems, and how successful such approaches are.

Sixth, when reviewing Tables , it is noticeable that most supply chain factors and characteristics is mentioned by only one or two sources, and some of these sources are very recent. This suggests that more research on the low-populated sub-categories and factors and their implications on CODP in extended supply chains is warranted. Here, research solely on MTS or MTO can be used to validate these factors and the framework.

Overall, there are many interesting empirical research possibilities for improving our understanding of the role and consequences of the CODP for internal operations and extended supply chains, and we hope that this framework can be a starting point.

Acknowledgments

This article is an extended and updated version of Harfeldt-Berg and Olhager (Citation2022), that was presented at the 22nd International Working Seminar on Production Economics in Innsbruck, Austria.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Jan Olhager, upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Magnus Harfeldt-Berg

Magnus Harfeldt-Berg is a Ph.D. candidate in Supply Chain & Operations Management at Lund University, the Faculty of Engineering. He received a M.Sc. in Economics, specialising in econometrics and regression analysis, from Lund University School of Economics and Management. His research interests involve supply chain strategy, decoupling points in the supply chain, supply chain sustainability and empirical research methods in supply chain and operations management.

Jan Olhager

Jan Olhager is Professor in Supply Chain & Operations Strategy at Lund University. He received an M.Eng. in Industrial Engineering and Operations Research from University of California at Berkeley, and a Ph.D. in Production Economics from Linköping University. He is Fellow of DSI, Decision Sciences Institute, and Honorary Fellow of EurOMA, European Operations Management Association. He is Associate Editor of Decision Sciences and IJOPM and serves on the editorial boards of IJPR and PPC. He has published more than 80 papers in international scientific journals and a couple of books. His research interests include international manufacturing networks, reshoring, operations strategy, supply chain integration, and operations planning and control.

References

- Agrawal, T. K., R. Kalaiarasan, J. Olhager, and M. Wiktorsson. 2022. “Supply Chain Visibility: A Delphi Study on Managerial Perspectives and Priorities.” International Journal of Production Research, https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2022.2098873.

- Akkerman, R., D. van der Meer, and D. P. van Donk. 2010. “Make to Stock and mix to Order: Choosing Intermediate Products in the Food Processing Industry.” International Journal of Production Research 48 (12): 3475–3492. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207540902810569.

- Berry, W. L., and T. Hill. 1992. “Linking Systems to Strategy.” International Journal of Operations & Production Management 12 (10): 3–15. https://doi.org/10.1108/01443579210017204.

- Breslin, D., and C. Gatrell. 2023. “Theorizing Through Literature Reviews: The Miner-Prospector Continuum.” Organizational Research Methods 26 (1): 139–167. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428120943288.

- Cannas, V. G., J. Gosling, M. Pero, and T. Rossi. 2019. “Engineering and Production Decoupling Configurations: An Empirical Study in the Machinery Industry.” International Journal of Production Economics 216:173–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2019.04.025.

- Childerhouse, P., J. Aitken, and D. Towill. 2002. “Analysis and Design of Focused Demand Chains.” Journal of Operations Management 20 (6): 675–689. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-6963(02)00034-7.

- D’Alessandro, A. J., and A. Baveja. 2000. “Divide and Conquer: Rohm and Haas’ Response to a Changing Specialty Chemicals Market.” INFORMS Journal on Applied Analytics 30 (6): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1287/inte.30.6.1.11627.

- Denyer, D., and D. Tranfield. 2009. “Producing a Systematic Review.” In The Sage Handbook of Organizational Research Methods, edited by D. A. Buchanan, and A. Bryman, 671–689. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Dittfeld, H., D. P. van Donk, and S. van Huet. 2022. “The Effect of Production System Characteristics on Resilience Capabilities: A Multiple Case Study.” International Journal of Operations and Production Management 42 (13): 103–127. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOPM-12-2021-0789.

- Drake, P. R., D. Myung Lee, and M. Hussain. 2013. “The Lean and Agile Purchasing Portfolio Model.” Supply Chain Management 18 (1): 3–20. https://doi.org/10.1108/13598541311293140.

- Drazin, R., and A. H. Van de Ven. 1985. “Alternative Forms of Fit in Contingency Theory.” Administrative Science Quarterly 30 (4): 514–539. https://doi.org/10.2307/2392695.

- Elsbach, K. D., and D. van Knippenberg. 2020. “Creating High-Impact Literature Reviews: An Argument for ‘Integrative Reviews’.” Journal of Management Studies 57 (6): 1277–1289. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12581.

- Ferreira, K. A., M. L. Toledo, and L. F. Rodrigues. 2021. “Postponement Practices in the Brazilian Southeast Wine Sector.” International Journal of Logistics Management 32 (1): 6–23. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLM-10-2019-0292.

- Fisher, M. 1997. “What Is the Right Supply Chain for Your Product?” Harvard Business Review 75 (2): 105–116.

- Flynn, B. B., B. Huo, and X. Zhao. 2010. “The Impact of Supply Chain Integration on Performance: A Contingency and Configuration Approach.” Journal of Operations Management 28 (1): 58–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2009.06.001.

- Flynn, B. B., S. Sakakibara, R. G. Schroeder, K. A. Bates, and E. J. Flynn. 1990. “Empirical Research Methods in Operations Management.” Journal of Operations Management 9 (2): 250–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/0272-6963(90)90098-X.

- Gaudenzi, B., and M. Christopher. 2016. “Achieving Supply Chain ‘Leagility’ Through a Project Management Orientation.” International Journal of Logistics Research and Applications 19 (1): 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/13675567.2015.1073234.

- Gresov, C., and R. Drazin. 1997. “Equifinality: Functional Equivalence in Organization Design Source.” Academy of Management Review 22 (2): 403–428. https://doi.org/10.2307/259328.

- Harfeldt-Berg, M., and J. Olhager. 2022. “The Role of the Customer Order Decoupling Point in Empirical Operations and Supply Chain Management Research: A Systematic Literature Review”. In Proceedings, 22nd International Working Seminar on Production Economics, Innsbruck, Austria, February.

- Harrison, A., and H. Skipworth. 2008. “Implications of Form Postponement to Manufacturing: A Cross Case Comparison.” International Journal of Production Research 46 (1): 173–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207540600844076.

- Hill, A., and T. Hill. 2009. Manufacturing Operations Strategy. Basingstoke: Palgrave-Macmillan.

- Hilletofth, P. 2009. “How to Develop a Differentiated Supply Chain Strategy.” Industrial Management & Data Systems 109 (1): 16–33. https://doi.org/10.1108/02635570910926573.

- Hoekstra, S., and J. Romme. 1992. Integrated Logistics Structures: Developing Customer Oriented Goods Flow. Cambridge: McGraw-Hill.

- Koh, S. C. L., A. Gunasekaran, and S. M. Saad. 2005. “A Business Model for Uncertainty Management.” Benchmarking: An International Journal 12 (4): 383–400. https://doi.org/10.1108/14635770510609042.

- Koh, S. C. L., and M. Simpson. 2007. “Could Enterprise Resource Planning Create a Competitive Advantage for Small Businesses?” Benchmarking: An International Journal 14 (1): 59–76. https://doi.org/10.1108/14635770710730937.

- Krishnamurthy, R., and C. A. Yauch. 2007. “Leagile Manufacturing: A Proposed Corporate Infrastructure.” International Journal of Operations & Production Management 27 (6): 588–604. https://doi.org/10.1108/01443570710750277.

- Meyer, A., A. Tsui, and C. Hinings. 1993. “Configuration Approaches to Organizational Analysis.” Academy of Management Journal 36 (6): 1175–1195. https://doi.org/10.2307/256809.

- Miller, D., and P. H. Friesen. 1984. Organizations: A Quantum View. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Mishra, D., R. R. K. Sharma, A. Gunasekaran, T. Papadopoulos, and R. Dubey. 2019. “Role of Decoupling Point in Examining Manufacturing Flexibility: An Empirical Study for Different Business Strategies.” Total Quality Management & Business Excellence 30 (9-10): 1126–1150. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2017.1359527.

- Moher, D., A. Liberati, J. Tetzlaff, D. G. Altman, and the PRISMA Group. 2009. “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement.” PLoS Medicine 6 (7): e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097.

- Molina, A., M. Velandia, and N. Galeano. 2007. “Virtual Enterprise Brokerage: A Structure-Driven Strategy to Achieve Build to Order Supply Chains.” International Journal of Production Research 45 (17): 3853–3880. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207540600818161.

- Naylor, J. B., M. M. Naim, and D. Berry. 1999. “Leagility: Integrating the Lean and Agile Manufacturing Paradigms in the Total Supply Chain.” International Journal of Production Economics 62 (1-2): 107–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0925-5273(98)00223-0.

- Nieuwenhuis, P., and E. Katsifou. 2015. “More Sustainable Automotive Production Through Understanding Decoupling Points in Leagile Manufacturing.” Journal of Cleaner Production 95:232–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.02.084.

- Ojha, D., J. Shockley, P. P. Rogers, D. Cooper, and P. C. Patel. 2021. “Managing Supplier Flexibility Performance as a Relational Exchange Investment in Make-to-Stock Versus Make-to-Order Production Environments.” Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing 36 (11): 2013–2024. https://doi.org/10.1108/JBIM-05-2019-0200.

- Olhager, J. 2003. “Strategic Positioning of the Order Penetration Point.” International Journal of Production Economics 85 (3): 319–329. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0925-5273(03)00119-1.

- Olhager, J. 2010. “The Role of the Customer Order Decoupling Point in Production and Supply Chain Management.” Computers in Industry 61 (9): 863–868. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compind.2010.07.011.

- Olhager, J., and D. I. Prajogo. 2012. “The Impact of Manufacturing and Supply Chain Improvement Initiatives: A Survey Comparing Make-to-Order and Make-to-Stock Firms.” Omega 40 (2): 159–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omega.2011.05.001.

- Olhager, J., and M. Rudberg. 2003. “Manufacturing Strategy and e-Business: An Exploratory Study.” Integrated Manufacturing Systems 14 (4): 334–345. https://doi.org/10.1108/09576060310469716.

- Olhager, J., and E. Selldin. 2007. “Manufacturing Planning and Control Approaches: Environmental Alignment and Performance.” International Journal of Production Research 45 (6): 1469–1484. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207540600635250.

- O’Reilly, S., A. Kumar, and F. Adam. 2015. “The Role of Hierarchical Production Planning in Food Manufacturing SMEs.” International Journal of Operations & Production Management 35 (10): 1362–1385. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOPM-04-2014-0157.

- Peeters, K., and H. Van Ooijen. 2020. “Hybrid Make-to-Stock and Make-to-Order Systems: A Taxonomic Review.” International Journal of Production Research 58 (15): 4659–4688. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2020.1778204.

- Pereira, D. F., J. F. Oliveira, and M. A. Carravilla. 2022. “Merging Make-to-Stock/Make-to-Order Decisions Into Sales and Operations Planning: A Multi-Objective Approach.” Omega 107:102561. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omega.2021.102561.

- Perona, M., N. Saccani, and S. Zanoni. 2009. “Combining Make-to-Order and Make-to-Stock Inventory Policies: An Empirical Application to a Manufacturing SME.” Production Planning & Control 20 (7): 559–575. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537280903034271.

- Post, C., R. Sarala, C. Gatrell, and J. E. Prescott. 2020. “Advancing Theory with Review Articles.” Journal of Management Studies 57 (2): 351–376. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12549.

- Prasad, S., J. Tata, and M. Madan. 2005. “Build to Order Supply Chains in Developed and Developing Countries.” Journal of Operations Management 23 (5): 551–568. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2004.10.011.

- Rahimnia, F., and M. Moghadasian. 2010. “Supply Chain Leagility in Professional Services: How to Apply Decoupling Point Concept in Healthcare Delivery Systems.” Supply Chain Management 15 (1): 80–91. https://doi.org/10.1108/13598541011018148.

- Seuring, S., and S. Gold. 2012. “Conducting Content-Analysis Based Literature Review in Supply Chain Management.” Supply Chain Management 17 (5): 544–555. https://doi.org/10.1108/13598541211258609.

- Sharman, G. 1984. “The Rediscovery of Logistics.” Harvard Business Review 62 (5): 71–79.

- Skipworth, H., and A. Harrison. 2006. “Implications of Form Postponement to Manufacturing a Customized Product.” International Journal of Production Research 44 (8): 1627–1652. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207540500362120.

- Soman, C. A., D. P. van Donk, and G. J. C. Gaalman. 2004. “Combined Make-to-Order and Make-to-Stock in a Food Production System.” International Journal of Production Economics 90 (2): 223–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0925-5273(02)00376-6.

- Soman, C. A., D. P. van Donk, and G. J. C. Gaalman. 2007. “Capacitated Planning and Scheduling of Combined Make-to-Order and Make-to-Stock Production in the Food Industry: An Illustrative Case Study.” International Journal of Production Economics 108 (1-2): 191–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2006.12.042.

- Tiedemann, F. 2020. “Demand-driven Supply Chain Operations Management Strategies – A Literature Review and Conceptual Model.” Production & Manufacturing Research 8 (1): 427–485. https://doi.org/10.1080/21693277.2020.1856012.

- Tiedemann, F., J. Wikner, and E. Johansson. 2021. “Understanding Lead-Time Implications for Financial Performance: A Qualitative Study.” Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management 32 (9): 183–207. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMTM-06-2020-0247.

- Tranfield, D., D. Denyer, and P. Smart. 2003. “Towards a Methodology for Developing Evidence-Informed Management Knowledge by Means of Systematic Review.” British Journal of Management 14 (3): 207–222. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.00375.

- Trentin, A. 2011. “Third-party Logistics Providers Offering Form Postponement Services: Value Propositions and Organisational Approaches.” International Journal of Production Research 49 (6): 1685–1712. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207541003623414.

- van der Vorst, J. G. A. J., S. J. van Dijk, and A. J. M. Beulens. 2001. “Supply Chain Design in the Food Industry.” International Journal of Logistics Management 12 (2): 73–86. https://doi.org/10.1108/09574090110806307.

- van Donk, D. P. 2000. “Customer-Driven Manufacturing in the Food Processing Industry.” British Food Journal 102 (10): 739–747. https://doi.org/10.1108/00070700010362176.

- van Donk, D. P. 2001. “Make to Stock or Make to Order: The Decoupling Point in the Food Processing Industries.” International Journal of Production Economics 69 (3): 297–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0925-5273(00)00035-9.