Abstract:

This editorial introduces the papers presented in the special issue. In a first point we show the coopetition research rise. Coopetition research really begins with the 21th century. Since the first academic papers on coopetition there is a fast growing trend which is looked as an opportunity for publications. Researches are now specialized in narrow topics, as the link between coopetition and innovation. The second point of this editorial introduces the main elements of the discussion on this topic. The link between coopetition and innovation is driven by “coopetitive dilemma” as a paradox between the need of cooperation to create value, and the attraction to compete for value appropriation. Coopetition should be a real opportunity to develop innovation, but also creates a risk of knowledge transfer to the coopetitors. So cooperating with competitor for innovation is a strategy under tension in a situation of instable equilibrium. The question is to know if firms must or not follow this kind of strategy. The question is also to know if risk created by coopetition for innovation could be successfully managed. Papers presented in this special issue are dedicated to these questions.

“Do you ever feel in competition?”

“No. Our generation …. We believe in coopetition. We believe that metal sharpens metal.

We’re constantly talking to each other.

We’re constantly helping each other.

We believe that it’s through our unity we’re strong, not through division. Competition is an old model.”

Mastin Kipp on “Oprah’s Super Soul Sunday,” January Citation2013

The Rise of Coopetition Research. Using a rigorous selection of the best works presented at the inaugural European Institute for Advanced Studies in Management (EIASM) workshop on coopetition, held in Catania in 2004, Dagnino (Citation2007) guest edited an issue of the International Studies of Management and Organization (ISMO) on coopetition, thereby launching coopetition as a “new category in strategy analysis” (Dagnino Citation2007, 3). The main driving force behind the development of the issue was the straightforward observation that the analytical lenses rooted in competition and in cooperation had proved increasingly inadequate to interpret the high-speed shifting business reality of 2000s. Therefore, the issue’s main contention was that we needed a more comprehensive “description of complex market structures where cooperation and competition merge together to form an entirely new perspective” (Dagnino Citation2007, 4). In this vein, the ISMO issue was truly foundational and open in scope and method, aiming at gathering contributions that could single out the central problems and perspectives on coopetition, as well as to draw together some relevant implications for theory and practice.

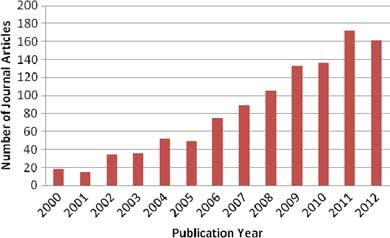

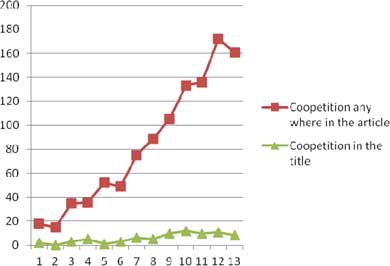

An entire decade has elapsed since the inaugural EIASM workshop on coopetition studies during which the initial contention was put forth, quite strikingly, that we have now a relatively compact but cohesive and expanding community within the field of strategic management that recognizes coopetition as its central theme of research. We also have a growing and evolving body of research on coopetition that originally started with the pioneering volume of Brandenburger and Nalebuff (Citation1996). Authors unanimously observe today that coopetition has experienced remarkable growth and assumed quite a momentum (Srivastava Citation2013; see also Figures and ).

FIGURE 1 Growth in coopetition research: Results of a search in Google Scholar for articles published in journals that have “journal” name in their titles, and include “coopetition” OR “coopetition and firm.”

FIGURE 2 Growth in coopetition research: Results of a search in Google Scholar for the word “coopetition” anywhere in the article OR in the title.

In fact, on October 20, 2013, the number of Google citations amounted to 301,000. The number of articles published in international academic journals has experienced a steep increase (26 from 2009 to the first semester of 2013 as compared with 21 in 2004–2008 and 8 in 1999–2003). Over 100 publications were made in practitioner outlets and newsletters between the first quarters of 2010 and 2013, and three academic books, exclusively devoted to the relevant issue, were numbered in this period.

Furthermore, we observe a burgeoning attention to coopetition in both online media and in traditional media, such as BBC, FT, WSJ, and the Huffington Post. Last, but certainly not least, while it was literally alien to dictionaries just a few years ago, the term “coopetition” appears today, not only in Wikipedia, which was the solitary case in 2007, but also in the Oxford Dictionary and Collins English Dictionary, where it is defined as “cooperation between competitors in business.” In the Financial Times Lexicon, coopetition is defined as “simultaneous competition and co-operation between a company and external players such as rivals, government agencies, suppliers, distributors, and partners.”

While these are a few unambiguous signs of visibility of the concept of coopetition in the last decade, authors also recognize that, currently, coopetition research suffers from the typical “liability of newness” related to an emerging theme of research, which reconnects to the relative lack of conceptual and methodological rigor in examining the underlying phenomenon (Srivastava Citation2013). Actually, while managers constantly face a multitude of tensions in creating and capturing value from coopetitive relationships, the analytical and conceptual models and tools, heretofore conceived and deployed to appreciate this significant phenomenon, are, in fact, rather too simplistic to encapsulate the multifaceted nature of coopetition tensions and the multiple challenges it poses (Padula and Dagnino Citation2007; Bengtsson, Eriksson, and Wincent Citation2010; Yami et al., Citation2010).

In this sense, coopetition research currently tackles a distinct conundrum. On the one hand, interest by both senior and junior academics is rising fast. Especially practitioners, such as executives, entrepreneurs, and consultants, find themselves caught in a manifold of coopetitive situations, which they do not know how to handle. On the other hand, we observe the relative lack of advanced conceptual frameworks and managerial tools to deal with coopetition dynamics and handle them in a proper fashion. This condition may, in fact, push its further development as a research domain within the field of strategic management. For these reasons, and because its momentum is rapidly increasing, we believe that coopetition provides today a tremendous set of opportunities and challenges for both scholars and practitioners.

This issue on coopetition and innovation aims to seize a good portion of the opportunities and challenges that coopetition provides today. In fact, after a rigorous selection and thorough double blind review process, we have managed to gather three of the best articles on the matter that were presented at the Fifth Workshop of the EIASM series on Coopetition Strategy held in Katowice, Poland, on September 12 and 13, 2012.

COOPETITION AND INNOVATION

Past research shows that innovation is one of the most important drivers of coopetition (Fernandez et al. Citation2014). Technological progress appears as a key driver of the decision to collaborate with competitors. The more complex and dynamic the environment, the more coopetition strategies are likely to occur (Gnyawali and Park Citation2011). In highly competitive and resource-poor environments, competing firms develop new technologies by pooling their resources (Jorde and Teece Citation1990). Coopetition strategies are employed by firms that try to develop product innovation (Belderbos, Carree, and Lokshin Citation2004). Innovation becomes more risky, and cooperation with competitors allows firms to share the risks of innovation. In fact, innovation and market performance are fostered by sharing risks and costs between competitors (Ritala Citation2012). When competitors decide to develop projects together, they combine their specialized competencies and create new opportunities, which, in turn, increase their innovation performance (Bouncken Citation2011). Cooperation with competitors is also used to promote the creation of industrial standards, as well as to increase the power of firms (Gnyawali and Park Citation2011).

Ritala and Hurmelinna-Laukkanen (Citation2009) considered the “coopetitive dilemma” as a paradox involving the need of cooperation to create value and the attraction to compete for value appropriation. This tension is particularly true in the innovation process. If firms really want to protect their resources, skills, and technologies, they tend not to share them with coopetitors. In this condition, cooperation is very low and can hardly generate innovation.

For this reason, for authors like Santamaria and Surroca (Citation2011), coopetition cannot be considered as a good strategy for innovation, especially for radical innovation. Indeed, according to these authors, various mechanisms of resource protection under a state of coopetition may reduce partner motivation to share resources and technologies for innovation. Conversely, Ritala (Citation2012) surmises that the benefit of sharing resources and skill in coopetition is higher than the risk of asymmetric learning. Coopeting firms have more similar and complementary resources than firms that are not coopetitors. Therefore, coopetition is potentially the most fruitful strategy for achieving innovation. While we acknowledge that coopetition strategies generate risks of knowledge appropriation by coopetitors, the benefit of coopeting is potentially higher than the risk.

Coopetition is not only a source of opportunity for product innovation, but also a source of tension. Coopetition is a paradoxically dual relationship that creates tensions within and between firms (Fernandez et al. Citation2014). Tensions are generated by the dual nature of coopetition, which is the simultaneous combination of two opposite dimensions of cooperation and competition. These tensions are inherent in coopetition and, while they can be attenuated, to solve them in a consistent fashion is arduous. Accordingly, coopetition may not be seen as the end of a rivalrous game, but rather as a new form of rivalry (Hamel, Doz, and Prahalad Citation1989). Coopetitors have shared interests and opposite interests at the same time, a situation that creates an unstable equilibrium between them (Castaldo and Dagnino 2009).

Coopetition is a compelling way to be acquainted with coopetitors. At the same time, knowledge of coopetitors might be used to overcome the coopetitors. Coopetition brings the opportunity to control and weaken the force of competitors and, as such, may allow gaining an advantage. Allying with a competitor is, on the one hand, an opportunity to win a stream of innovations and technological advancements, and, on the other, an opportunity to appropriate coopetitor knowledge. In this instance, coopetitors might be conquered by the temptation to increase their private knowledge devoid of transferring strategic knowledge to the partner, a process that might begin a learning race (Hamel Citation1991).

Coopetition-driven innovation may also be grounded on a hidden agenda of a coopeting partner according to which his/her goal is to win a short-term or a long-term advantage. Long-term coopetition highly increases opportunities and threats within a highly engaging relationship. The longer and the more intense the cooperation, the greater the possibility of the competitor using the resources and capabilities shared during the partnership to buttress its advantage.

Summing up, whether the benefits exceed the risks in coopetition for innovation is an open question. Should firms avoid competitors when they look for technology partnership? Or, conversely, should they look to their competitors as their best potential partners for innovation? How can firms manage relationships with their competitors to generate innovation? Can best practices be developed to share and protect technology simultaneously in coopetition for innovation? This issue tries to answer some of these questions.

THE ARTICLES IN THIS ISSUE

The three articles included in this special issue have a specific empirical proclivity, especially stemming from the fruitful combination of coopetition studies and technology and innovation management research. In fact, to approach innovation without realizing that most of it is done in cooperation by competing actors appears extremely difficult. As a set, the three articles outline a coopetition stance on innovation that looks at the partners involved, at the determinants of coopetition emergence, and at modeling key issues typical to asymmetric and fast changing settings.

In the first article, Frédéric Le Roy, Marc Robert, and Frank Lasch test, on a large sample of French firms, hypotheses related to coopetition emergence by focusing on the type of partner, type of innovation, and the geographical location of the potential partner. This contribution provides a systematic comparison of the impact of cooperative relations on innovation depending on the type of partner involved. The results identify customers and universities as the best noncompetitor partners and competitors located in Europe or North America as the best competitor partners.

In the second article, André Nemeh and Saïd Yami adopt a case study methodology to unveil several determinants, including context, to explain coopetition in R&D in European wireless telecommunication projects. This study seeks to see how the degree of maturity of technology shapes a firm’s choice of coopetition strategy. The results show that competitors that work together to render the technology more mature do not reach to the development of final products and services stage. This situation creates a time-lag between cooperative and competitive behaviors in coopetition strategy.

In the third article, Daniela Baglieri, David Carfi, and Giovanni Battista Dagnino draw on mathematical modeling and, in more detail, an advanced game theoretical formalization specifically tailored to coopetition, to show how coopetition helps understand the unfolding of R&D alliances that specifically concern high tech environments, such as the biopharmaceutical industry. This contribution proposes a formal coopetitive approach, where coopetition is a vector variable belonging to an n-dimensional Euclidean space. The results show that cooperative efforts are required and beneficial even though partners are potential competitors. Cooperative efforts between competitors shape the common payoff space that they collectively create.

The three articles presented in this special issue study the link between coopetition and innovation. In this global topic, they each focus on a particular question: the link between the type of cooperation and innovation, in the first article; the drivers of coopetition, in the second article; and coopetition dynamics inside R&D alliances, in the third article. The three articles are diverse in their methods: the first one is based on a quantitative analysis of a large sample, the second is based on qualitative case study research, and the last is based on a game theory simulation. Moreover, samples and levels of analysis differ in the articles. This diversity of questions, methods, and samples highlights the fact that we are faced with a multidimensional phenomenon that could be seen as a research program that is still in need of further exploration.

REFERENCES

- Belderbos, R., M. Carree, and B. Lokshin. 2004. “Cooperative R&D and Firm Performance.” Research Policy 33(10):1477–92. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2004.07.003

- Bengtsson, M., J. Eriksson, and L. Wincent. 2010. “New Ideas for a New Paradigm.” In Coopetition: Winning Strategies for the 21st Century, edited by S. Yami, S. Castaldo, G. B. Dagnino, and F. Le Roy, 19–39. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Bouncken, R. 2011. “Innovation by Operating Practices in Project Alliances: When Size Matters.” British Journal of Management 22(4):586–608. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8551.2010.00688.x

- Brandenburger, A. M., and B. J. Nalebuff. 1996. Co-opetition. New York: Doubleday.

- Dagnino, G. B. 2007. “Preface. Coopetition strategy: Towards a New Kind of Inter-firm Dynamics?” International Studies of Management and Organization 37(2):3–10. doi:10.2753/imo0020-8825370200

- Fernandez, A-S., F. Le Roy, and D. Gnyawali. 2014. “Sources and Management of Tension in Coopetition Case Evidence from Telecommunications Satellites Manufacturing in Europe.” Industrial Marketing Management 43(2):222–235.

- Gnyawali, D. R., and B. J. Park. 2011. “Co-opetition Between Giants: Collaboration between Competitors for Technological Innovation.” Research Policy 40(5):650–63. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2011.01.009

- Hamel, G. 1991. “Competition for Competence and Inter-partner Learning within International Strategic Alliances.” Strategic Management Journal 12(S1):83–103. doi:10.1002/smj.4250120908

- Hamel, G., Y. Doz, and C. K. Prahalad. 1989. “Collaborate with Your Competitors and Win.” Harvard Business Review 67(1):133–39.

- Jorde, T. M., and D. J. Teece. 1990. “Innovation and Cooperation: Implications for Competition and Antitrust.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 4(3):75–96. doi:10.1257/jep.4.3.75

- Kipp, M. 2013. “Oprah Super Soul Sunday.” Accessed January 2013. http://on.aol.com/video/meet-the-next-generation-of-spiritual-thought-leaders-517539642

- Padula, G., and G. B. Dagnino. 2007. “Untangling the Rise of Coopetition: The Intrusion of Competition in a Cooperative Game Structure.” International Studies of Management and Organization 37(2):32–52. doi:10.2753/imo0020-8825370202

- Ritala, P. 2012. “Coopetition Strategy—When Is It Successful? Empirical Evidence on Innovation and Market Performance.” British Journal of Management 23(2):307–24.

- Ritala P., and P. Hurmelinna-Laukkanen. 2009. “What’s in It for Me? Creating and Appropriating Value in Innovation-related Coopetition.” Technovation 29(12):819–28. doi:10.1016/j.technovation.2009.07.002

- Santamaria, L., and J. Surroca. 2011. “Matching the Goals and Impacts of R&D Collaboration.” European Management Review 8(2):95–109. doi:10.1111/j.1740-4762.2011.01012.x

- Srivastava, M. 2013. “Coopetition Research: Moving Beyond the Metaphor.” Professional Development Workshop, Academy of Management Annual Meeting, Lake Buena Vista, FL, August 9–13.

- Yami, S., S. Castaldo, G. B. Dagnino, and F. Le Roy, Eds. 2010. Coopetition: Winning Strategies for the 21st Century. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.