Abstract

The current article is one of the rare studies to specifically focus on the contextual conditions under which the learning-related actions of transformational supervisors’ help retailing supermarkets’ store managers to learn and engage in behaviors that produce creative outcomes. We use a qualitative research approach with the data based on in-depth semi structured interviews with 40 retailing supermarkets’ store managers in Nigeria, South Africa and the UK. Our findings show that transformational supervision significantly boosts store managers’ creativity, facilitated by fostering store managers’ learning orientation, creative role identity (CRI) and creative self-efficacy (CSE), in all three contexts. From our findings, we have developed a model that symbolize the role of transformational supervisors in fostering store managers’ creativity, which provides a baseline for supermarkets in (re)evaluating the significance of their leadership styles on follower creativity.

Introduction

This study examines how transformational supervisors (TSs) facilitate store managers’ (SMs’) creativity, facilitated by fostering SMs’ learning orientation, creative role identity (CRI) and creative self-efficacy (CSE). Transformational supervision—a mentoring-infused supervisory relationship where a supervisor and supervisee are engaged in a connected and collaborative developmental relationship (Johnson Citation2007)—fosters a strong sense of collegiality and a wider range of career and developmental prospects (Johnson, Skinner, and Kaslow Citation2014). Although transformational supervision is not an entirely new concept, empirical data examining the role of TSs in different kind of organizations, is, at best, limited. Yet, by encouraging critical reflection (Carroll Citation2009) and dialectical thinking (Han and Bai Citation2020), TSs foster different perspectives which are crucial when the supervisee is stuck or confused, or the pair are becoming complacent (Churchill Citation2013), and thus helps the supervisee discover their blind spots (Carroll Citation2010; Churchill Citation2013). Therefore, transformational supervision has been linked to self-efficacy (Mielniczuk and Laguna Citation2020; Tse, To, and Chiu Citation2018), improved employees’ well-being (Perko, Kinnunen, and Feldt Citation2014), employee voice (Morrison Citation2014; Wang et al. Citation2019), constructive change-oriented communications (LePine and Van Dyne Citation2001), and thus an enhanced subordinate’s performance in hard times (Phillips et al. Citation2020). Transformational supervision has also been linked to reduced illegitimate absenteeism—staying away from work when well (Frooman, Mendelson, and Murphy Citation2012)—which is high in jobs with high levels of autonomy, such as the store managers. Therefore, adopting the transformational style of supervision [in supermarkets] may help to reduce costs (Frooman, Mendelson, and Murphy Citation2012).

Shoppers have become pickier (Benoit, Evanschitzky, and Teller Citation2019; McTaggart Citation2006; Mitchell Citation2011). Consequently, a more complex and competitive supermarket environment has emerged (McTaggart Citation2006; Mitchell Citation2011). Although SMs are key to supermarket success (e.g., Bartels, Reinders, and Van Haaster-De Winter Citation2015), there is a paucity of empirical data that examines how supervisors can boost the creativity and problem-solving skills of the SMs, and which these authors suggest is a significant omission in the retail supermarkets literature.

Although the retail environment has been evolving (Olsson et al. Citation2019), the 21st century retail environment is even more complex and competitive due to unprecedented challenges caused by digitalization and globalization (Burt Citation2010; Dawson Citation2001). Despite its dynamic and highly competitive nature, creativity in this sector is still relatively under investigated (Olsson et al. Citation2019). Yet, due to shortening product life cycles (Gumusluoglu and Ilsev Citation2009), supermarkets need to be more creative than before to survive (Jung, Chow, and Wu Citation2003). These aspects highlight the need for research that investigates the organizational environment for creativity in the supermarkets. Research that examines how TSs encourage SMs to devise novel ideas (Amabile Citation1983, Citation1988) on new products, services, and processes (Wang, Tsai, and Tsai Citation2014), is also crucial for the theoretical development of the creativity literature.

The creativity literature (e.g., Chamorro-Premuzic Citation2006; see also Gilson Citation2008 for a review) focus more on the academic environment. Therefore, we know relatively little about how the transformational behaviors of supervisors impact their subordinates’ creativity in a non-academic environment (Gong, Huang, and Farh Citation2009), e.g., the supermarkets. Given the significance of transformational leadership behavior on follower creativity (e.g., Gong, Huang, and Farh Citation2009; Wang, Tsai, and Tsai Citation2014) it is surprising that such an impact has been largely overlooked in the non-academic setting. One of the few relevant studies was undertaken by Gong, Huang, and Farh (Citation2009), who (used employee learning orientation and transformational leadership as mediating variables to) examine how employee creativity can impact performance. Gong, Huang, and Farh (Citation2009) omitted employee performance orientation, and their sample was drawn from insurance agents who had relatively low education, and from Taiwan alone. Therefore, the authors call for replications of their findings in other organizations, in different job categories, and with a relatively more educated samples that are drawn from diverse cultural settings. The present article meets such criteria. Unlike some prior studies that drew from manipulated or experimental confederates (Gong, Huang, and Farh Citation2009), participants in the current study are actual store managers from top supermarkets in Nigeria, South Africa, and the UK. Although we are aware that the economies of each of these three countries are unique, we have chosen the British supermarkets for a reason. Due to their colonial legacies (Barnes-Dabban, Van Koppen, and Mol Citation2017), the British system of education has been the driving force for the socio-economic development of many African states (Archibong Citation2019), including Nigeria and South Africa.

Therefore, to help us understand the supervisor-supervisee relationships in these African retailing markets, we need to follow similar developments and trends in the British retailing. Also, selecting cases with same focal phenomenon and from three culturally distinct countries is consistent with Bingham and Eisenhardt (Citation2011) study on Singapore, United States, and Finland. Such a study enhances generalizability (i.e., transferability) of the emergent theory across settings (Eisenhardt Citation2021). Our article offers three important contributions to the extant literature streams on leadership and creativity in organizations. Firstly, it is one of the pioneering studies to highlight the specificities of transformational supervision in retailing sector in African context, while comparing its dynamics at the same time with British retailers. Secondly, the current article is one of the rare studies to theorize and qualitatively assess SM learning orientation, CRI and CSE in fostering creativity linked to transformational supervision. Our findings contribute to the understanding of this complex inter-relationship at sectoral and contextual levels. Finally, rather similar findings from all three countries highlight the significant role of historical ties and educational systems on leadership (including transformational supervision) styles in organizations even though they are physically located in distant and different contexts.

The rest of this article is structured as follows. Section two reviews the relevant literature. Section three presents the method and justifies the choices made. Section four presents and analyses the findings. Section five discusses the result in relation to the extant literature, while section six offers practical implications. The article concludes with presentation of study limitations and future research directions.

Literature review

Theorizing learning orientation

Learning orientation—the personal interest and commitment toward developing competence (Bunderson and Sutcliffe Citation2003) as against demonstrating competence (Dweck Citation1986, Citation2000; Dweck and Leggett Citation1988)—is the foundation for competitive advantage (Harvey et al. Citation2019). Learning oriented individuals are intrinsically motivated (Hirst, Van Knippenberg, and Zhou Citation2009) and self-regulated (Bouffard et al. Citation1995) to acquiring new knowledge while unlearning obsolete skills (Matsuo Citation2020). By this means, they seek incessant self-improvement (Jha and Bhattacharyya Citation2013). Since highly learning-oriented employees are believed to have high challenge seeking behaviors and competency development attributes (Porter, Webb, and Gogus Citation2010), learning oriented behavior is linked to employee creativity (Redmond, Mumford, and Teach Citation1993). In their study of learning-oriented behavior in a marketing agency, Swart and Kinnie (Citation2007) also found learning oriented behavior as key to value creation in a marketing environment. Therefore, highly learning-oriented SMs could be key to sustained competitive advantage in a dynamic environment, such as the supermarket sector studied here.

Although the transformational leadership style has been linked to learning-oriented employees (e.g., Gong, Huang, and Farh Citation2009), followers’ explorative behaviors and followers’ creativity (e.g., Adil, Hamid, and Waqas Citation2020; Afsar and Masood Citation2018; Cai et al. Citation2021; Han and Bai Citation2020; Mielniczuk and Laguna Citation2020; Mittal and Dhar Citation2015), empirical data linking transformational leadership, employee learning orientation and creativity is still relatively lacking (Gong, Huang, and Farh Citation2009). The current article contributes to filling such a research gap. Building on Gong, Huang, and Farh (Citation2009), this study seeks to examine whether, and how, TSs influence SMs’ creativity, facilitated by fostering SM’s learning orientation, CSE and CRI.

Due to the link between creative workplace and attaining a competitive advantage (e.g., Fahy Citation1996; George and Zhou Citation2002; Oldham and Cummings Citation1996), studies, such as Adil, Hamid, and Waqas (Citation2020), Afsar and Masood (Citation2018), Cai et al. (Citation2021), Han and Bai (Citation2020), Mielniczuk and Laguna (Citation2020) and Mittal and Dhar (Citation2015) have stressed the need for supervisors to support employee creativity, by nurturing their CSE. Based on Bandura’s theorizing on self-efficacy, i.e., a person’s belief in his or her own capacity to “organize and execute the courses of action required to produce a given attainment” (Bandura Citation1997, 3), CSE rests on individual’s ability to produce creative outcomes (Gong, Huang, and Farh Citation2009; Ma et al. Citation2021). As a conviction that an individual has the necessary competence to generate creative results (Mielniczuk and Laguna Citation2020; Tse, To, and Chiu Citation2018), CSE, is, thus, a key to high performance in a wide range of tasks (Bandura Citation1986, Citation1997). Yet, there is still a lack of empirical data that examines the role of the TSs in nurturing the SMs’ learning orientation, CRI, CSE and creativity.

Transformational supervisor (TS) and employee creativity

Building a creative workplace requires a culture of autonomy, innovation and trial and error (Elkins and Keller Citation2003)—an ethos which epitomizes the transformational leadership style (Mittal and Dhar Citation2015). By devising a vision for their teams (Bass Citation1985), by fostering employees’ ability to finding creative solutions to problems (Bass Citation1985; Boerner, Eisenbeiss, and Griesser Citation2007), and by invoking additional discretionary effort in employees (Adil, Hamid, and Waqas Citation2020; Afsar and Masood Citation2018; Cai et al. Citation2021; Han and Bai Citation2020), transformational supervisors facilitate employee creativity (Mielniczuk and Laguna Citation2020; Mittal and Dhar Citation2015). Moreover, through delegation of authority and fostering of autonomy (Bass Citation1985), the transformational leadership style not only facilitates better skill acquisition and mastery development (Adil, Hamid, and Waqas Citation2020; Afsar and Masood Citation2018; Cai et al. Citation2021; Han and Bai Citation2020), but higher follower creativity (Gong, Huang, and Farh Citation2009; Mielniczuk and Laguna Citation2020; Mittal and Dhar Citation2015). Due to their tendency to generate novel solutions to tasks at hand (Amabile Citation1983, Citation1996, Citation1988), creative employees have a high drive for tackling organizational challenges (Bandura Citation1986; Royston and Reiter-Palmon Citation2019), and in a lean and efficient manner (Gong, Huang, and Farh Citation2009) that meet customers’ products and service needs (Zhou Citation1998; Zhou and Shalley Citation2003, Citation2008). Therefore, they are highly rated by their supervisors (Oldham and Cummings Citation1996). Yet, empirical data examining the role of transformational supervisors in fostering subordinates’ creativity is still needed, especially, in a more complex and competitive environment like the retail supermarkets.

Although the literature on the antecedents of employee creativity has burgeoned (Wang, Tsai, and Tsai Citation2014), there is still a lack of consensus on both the antecedents and consequences of employee creativity (Gong, Huang, and Farh Citation2009). The influence of transformational leadership on employee creativity has been highlighted (e.g., Mielniczuk and Laguna Citation2020; Mittal and Dhar Citation2015). However, at the same time, scholars argue that it could take quite a while for such an influence to be evidenced (e.g., Gong, Huang, and Farh Citation2009, 766). This is due to the gap between when knowledge is acquired and nurtured, and when creative solutions to problems are established (Weisberg Citation1999). Yet, the transformational leadership outcomes of commitment (e.g., Keskes et al. Citation2018), performance (e.g., Ng Citation2017), visioning and innovation (Bass Citation1985) and effective leadership (Grant Citation2012; Vera and Crossan Citation2004) link transformational supervision to follower creativity (e.g., Koh, Lee, and Joshi Citation2019; Mittal and Dhar Citation2015).

Transformational supervisor (TS), creative self-efficacy (CSE), and creative role identity (CRI)

While CSE demonstrates the degree a person believes (s)he can bring resources to bear to yield innovative results (Mielniczuk and Laguna Citation2020; Orth and Volmer Citation2017), CRI shows whether an individual thinks himself/herself a creative person (Farmer, Tierney, and Kung-McIntyre Citation2003; Wang, Liu, and Shalley Citation2018). Drawing on Bandura’s (Citation1986) social cognitive theory, Christensen-Salem et al. (Citation2020) have linked both CRI and CSE to employee creativity. Farmer, Tierney, and Kung-McIntyre (Citation2003) also view CRI as facilitating employee’s ability to device innovative solutions to work based problems. Although factors that enhance CRI are vast, TS is key. For instance, by stimulating their intellectual curiosity (Bass, Avolio, and Goodheim Citation1987; Bass and Steidlmeier Citation1999; Cai et al. Citation2019; Grosser, Venkataramani, and Labianca Citation2017), TS can encourage SMs to devise innovative products and service standards that meet customers’ expectations (Hu, Kandampully, and Juwaheer Citation2009). This facilitates SMs’ self-identity (Tajfel and Turner Citation1979, Citation1986), and which is particularly crucial in complex and challenging job roles like the supermarket store managers’, where identity, high autonomy, feedback, skill-variety, skill-significance, and intrinsic motivation are key to success (Amabile Citation1988; Oldham and Cummings Citation1996; Shalley, Zhou, and Oldham Citation2004).

Transformational supervisor (TS) and employee creativity: the roles of learning orientation, creative self-efficacy (CSE), and creative role identity (CRI)

The link between employee creativity and leadership style has been emphasized sufficiently (e.g., Shalley and Gilson Citation2004; Amabile et al. Citation2005). Specifically, employee creativity is linked to the transformational leadership style (e.g., Gong, Huang, and Farh Citation2009). Follower high self-confidence (Afsar and Masood Citation2018) and high CSE levels (Mittal and Dhar Citation2015) have also been found to depend on transformational leadership capability. For instance, by encouraging knowledge sharing (Mittal and Dhar Citation2015), learning and inspiring vision (Grant Citation2012; Vera and Crossan Citation2004), independent thinking (Gumusluoglu and Ilsev Citation2009), collective and challenging tasks (Rubin, Munz, and Bommer Citation2005), transformational leadership can boost subordinates’ self-confidence at work (Afsar and Masood Citation2018; Mittal and Dhar Citation2015). By helping subordinates attain such high levels of CSE (Walumbwa and Hartnell Citation2011), transformational leadership, is, thus, a precursor of employee creativity (Gong, Huang, and Farh Citation2009; Mittal and Dhar Citation2015, 896).

Bass and Avolio (Citation1994) have also identified four dimensions to illustrate how the learning-related actions of TSs can influence SM’s learning orientation and creativity. By using behavioral role modeling (Matsuo Citation2020), through idealized influence (Afsar and Masood Citation2018; Bass and Avolio Citation1994), TS can encourage SM to unlearn bad behavior while learning acceptable behavior. Thereby, helping supermarkets adopt appropriate behaviors that suit the fluctuating customers’ preferences. Through inspirational motivation (Bass and Avolio Citation1994), TSs can increase SMs’ self-confidence (Bandura Citation1997; Royston and Reiter-Palmon Citation2019) and CSE levels (Adil, Hamid, and Waqas Citation2020; Afsar and Masood Citation2018; Cai et al. Citation2021; Han and Bai Citation2020). Thereby, fostering SMs’ problem-solving skills (e.g., Han and Bai Citation2020), as SMs can then devise new products, services and processes that meet customers’ expectations, and which typifies high creativity (e.g., Adil, Hamid, and Waqas Citation2020; Afsar and Masood Citation2018; Cai et al. Citation2021; Han and Bai Citation2020; Mielniczuk and Laguna Citation2020; Mittal and Dhar Citation2015). Through intellectual stimulation (Bass and Avolio Citation1994), TSs can stimulate SMs ability to rethink previous problems in novel ways. Thereby, encouraging SMs to challenge the status quo (Gong, Huang, and Farh Citation2009), and which indicates enhanced creativity (Amabile et al. Citation2004). Through individualized consideration (Bass and Avolio Citation1994), TSs can encourage SMs to personally listen to individual staff/customers’ need, and, therefore, providing tailored support for individual circumstances. These learning-related behaviors of the TSs are crucial for providing better quality services (Mohsin and Lockyer Citation2010; Ogaard, Marnburg, and Larsen Citation2008). They are also consistent with the social cognitive theory (Bandura Citation1986), which is the foundation for creative behavior and high-level self-efficacy (Gong, Huang, and Farh Citation2009; Royston and Reiter-Palmon Citation2019). From these viewpoints, TSs can stimulate SMs’ learning orientation, creative thinking, and their ability to generate novel solutions to problems, and which are key to building and maintaining a competitive advantage in a dynamic environment (like the supermarkets’) (Amabile et al. Citation2005; George Citation2007). Yet, there are lack of empirical evidence that link TSs and subordinates’ learning orientation and creativity in non-academic settings. To contribute to addressing this research gap, this study addresses the following research question.

How does transformational supervision impact SM’s learning orientation and creativity?

Research methodology

Given the subjective nature of the above constructs, the uniqueness of the themes and contexts, and the theoretical argument required to address the above research question, an exploratory study through qualitative approach is required. When generating a relationship between complex constructs (e.g., supervisory relationships, learning orientation, CRI, CSE, and creativity), it is recommended that each participant be allowed ample time to elaborate freely on their views without being interrupted (Liu and Rong Citation2015). Therefore, this study has adopted a qualitative method, with an interpretivist philosophy. The qualitative research literature (e.g., Gibbert and Ruigrok Citation2010) emphasizes the standard of rigor required in qualitative studies. Although the standard of rigor (e.g., reliability, internal and external validity, and construct validity) embedded in the positivist approach might be lacking in qualitative studies, qualitative researchers can still prove a strong degree of rigor through a thorough analysis of the actual research actions undertaken (Gibbert and Ruigrok Citation2010). Lee (Citation1999) has used methodological rigor, high degree of transparency, thorough analysis, and good outcome with a long-term validity and reliability, but, most importantly, one that contributes to the existing body of management knowledge, to qualify standard qualitative research. For Lincoln and Guba (Citation1985), transferability, credibility, confirmability, and dependability are the criteria for assessing the validity and reliability of a qualitative research. Following these authors’ recommendations, this section provides a thorough explanation of the genuine research activities (including the methods and processes) undertaken during the data collection and analyses processes, and, therefore, enhances the validity and reliability of this study (Creswell Citation2007; Gioia, Corley, and Hamilton Citation2013; O’Reilly, Paper, and Marx Citation2012).

To enhance validity in the selection of the participating supermarkets, the criteria adopted include (a) the top 10 supermarkets in their respective countries, and which thus implies they are (b) of international standard and are (c) highly competitive. These criteria have allowed the researchers to choose only the best performing supermarkets in these countries.

The purposive sampling method was adopted in choosing the participating SMs. Notwithstanding the contradictions in the theorizing of the purposive sampling method, there is a consensus—the researcher is sampling with a purpose (Saunders, Lewis, and Thornhill Citation2012)—and in this case, to select 40 SMs from top supermarkets in Nigeria, South Africa and the UK. The purposive sampling approach is also appropriate when the target participants are discrete (White et al. Citation2018), e.g., the SMs from the best performing supermarkets in these countries. The criteria adopted to enhance validity in the selection of the participating SMs include: (a) a well-defined managerial hierarchy in each participating supermarket to prove clearly (b) that the participant is not a senior/top manager, rather can easily be identified as a SM in control of a store, and (c) is thus answerable to a supervisor/line-manager. These selection criteria also suit the research questions, i.e., by allowing the study to examine how the learning related actions of the supervisors facilitate each participant’s learning orientation, and how these could be linked to the participant’s creativity. Given many willing participants from the UK, the selection of the UK participants was limited to the UK’s BIG four—Tesco, Asda, Sainsbury’s, and Morrison’s—and where 10 participants were selected. 16 participants were selected from three branches of South Africa’s big chain, and a total of 14 participants from eight different supermarkets in Nigeria. The selection of the African supermarkets was based on the ranking by Chambers of Commerce in both Nigeria and South Africa. The criteria for ranking supermarkets in these three countries are the same—store appearance, queueing time, staff availability, range of products, quality of own-label products, quality of fresh produce, value for money, and customer score.

Data collection

The raw data was collected during store visits between September 2014 and June 2015, via in-depth semi structured interviews. The 40 interviews took (roughly) 88 h to complete, meaning, on average, it took (approximately) 2 h and 20 min to complete each. To solicit their consent and to inform participants about the purpose of the study, each participant received an average of two emails prior to the interview. Originally, 50 participants (i.e., 18 from Nigeria, 18 from South, and 14 participants from the UK) were targeted. Due to such enough communication, willingness to participate were high from both continents, but not without some stipulations. First, participants demanded that the conversations occur during their businesses’ quieter periods. Second, that the conversations be paused midway (at the interviewees’ discretions) to allow them attend to their businesses’ needs. In line with Liu and Rong (Citation2015) recommendations, participants were allowed sufficient time (with minimal interruptions from the interviewer) to discuss extensively how their supervisors support their learning orientation, and if, and how, such support results in the development of new products, services, and processes/procedures in their stores. below illustrates the data collection and data analysis process.

Table 1. Data collection and analysis process.

Data analysis

The role of theoretical argument in building theories that hook the readers’ attention in case study research has been emphasized (e.g., Eisenhardt Citation1989a, Citation2021). Given the theoretical argument required to explain how transformational supervision impacts subordinate’s learning orientation and creativity in these supermarkets, insights from the “Eisenhardt Method” were too compelling to ignore. Yin’s (Citation1984) work on cases (and replication logic) and Glaser and Strauss (Citation1967) iterative process of constant comparison of data and theory (as well as theoretical sampling and saturation) were also drawn upon.

Justifications for adopting the “Eisenhardt method”

This study adopts the “Eisenhardt Method” for the following reasons. First, the chosen method should address a research question for which there is a limited or contradictory prior theory and/or empirical evidence (Eisenhardt Citation2021). Our research question which explores how transformational supervision impacts store managers learning orientation and creativity lacks prior empirical evidence (Gong, Huang, and Farh Citation2009), and is thus very likely to yield fertile opportunities for theory building (Eisenhardt Citation2021).

By linking transformational supervision with subordinate’s creativity, our research question is also investigating an under-represented theory in a well-researched literature (Eisenhardt Citation2021; Gong, Huang, and Farh Citation2009), which Eisenhardt (Citation1989b) refer as a “cool” yet under-studied phenomenon. Our broad question can also be perceived as an attempt to look inside the “black box” of a process (Bingham and Eisenhardt Citation2011). Indeed, an attempt to answer the research question extends into the vast learning literature that links experience to outcomes, but specifically explores how the learning phenomena has evolved over time (Eisenhardt Citation2021). For instance, the present study is probing—how the learning-related actions of the transformational supervisors help store managers learn and engage in behaviors that produce creative outcomes. This phenomenon is also embedded in our interview questions (Eisenhardt Citation2021).

Our research question is also exploring a unique setting (Eisenhardt Citation2021)—top supermarkets in Nigeria, South Africa, and the UK. Through a careful case selection (i.e., theoretical sampling), this method not only eliminates supermarkets that are not of theoretical interest (e.g., lacking the requisite qualities of the top 10 in their respective countries), but enhances generalizability (Eisenhardt Citation2021). Selecting cases with same focal phenomenon and from three culturally distinct countries is also consistent with Bingham and Eisenhardt (Citation2011) study on Singapore, United States, and Finland, which Eisenhardt (Citation2021) believe to enhance generalizability (i.e., transferability) of the emergent theory across settings. Similarities and differences across such cases not only present unexpected theoretical opportunities that enrich theory building (Eisenhardt Citation2021) but sharpens the empirical focus (Eisenhardt Citation2021; Hallen and Eisenhardt Citation2012; Kirtley and O’Mahony 2020). Our samples also share some characteristics (e.g., store appearance, queueing time, staff availability, range of products, quality of own-label products, quality of fresh produce, value for money, and customer score) that have previously predicted successful outcomes from prior research (Davis and Eisenhardt Citation2011).

Researchers using the grounded theorizing have utilized different phrases, such as first- and second-order themes (e.g., Gioia, Corley, and Hamilton Citation2013) or staying closer to the original wording of grounded theory (Glaser and Strauss Citation1967). Regardless of the terminology, the aim of the analysis is to achieve a fit between the data and the dominant theory (Eisenhardt Citation2021) through an iterative organization, grouping, and regrouping of the raw data (Braun and Clarke Citation2006), repetition of logic (Yin Citation1984), continuous comparison (Glaser and Strauss Citation1967), and formation of more abstract conceptualization (Walsh et al. Citation2015). Such a persistent and creative iteration process provides a fit between the theory and cases, surprisingly well (Eisenhardt Citation2021, Citation1989a). To achieve a high level of fit through explicit theoretical arguments that support why particular emergent relationships between constructs are likely to hold (Eisenhardt Citation2021), similar sets of data from multiple cases are combined (e.g., Bechky and Okhuysen Citation2011). This facilitates theoretical arguments that are based on data and logic, and thus addresses the internal validity, which is at the heart of theory building (Eisenhardt Citation2021). To ensure a persistent and creative iteration process that meets the above requirements, the data analysis has drawn on Braun and Clarke (Citation2006) suggestions on the six-stage process of the qualitative data analysis.

The six-stage data analysis process

Data familiarization

The researcher commenced the data analysis process by first listening to the recorded audio interviews several times, until familiarity with the raw data was achieved. This was then followed by transcription of all the audio files into written ones. To ensure a thorough transcription of the data, the researcher crosschecked all the written texts (i.e., the transcripts) against the oral interviews (i.e., the recorded audio) data. Although no significant differences were found, for ease of display, a few amendments (to the interview quotes) were made.

Generating the initial codes

With all the interview data transcribed at this stage, the coding of the interview transcripts began. The coding process involved classifying and segmenting the transcribed data (based on their similarities in meaning) into various units of more meaningful, cohesive categories, and attaching conceptual labels to each data group for ease of identification, and thus enhances their validity. However, the coding process was incessant until enough distinguishing categories emerged between the various data groups (Eisenhardt Citation1989a; Strauss and Corbin Citation2008). This exhaustive coding process has helped the researcher align the relevant raw interview data with their conforming themes during the data analysis (Goulding Citation2002; Strauss and Corbin Citation2008), and thus enhances validity (Eisenhardt Citation2021). Although each group/subgroup of data was coded separately, confusion still emerged on a few occasions, necessitating the raw interview data were revisited for modifications and recoding, before realigning them with their corresponding content-themes.

Searching for themes

At this stage, the researcher needed to create a more meaningful and memorable expression of the data sets. Therefore, based on corresponding theories, four distinctive statements (i.e., the four main themes) were deduced to show how TSs can influence SMs’ creativity. Based on the similarities in meanings (of the data sets) and coupled with their relationship with the corresponding literature and the key issues addressed in this study, the researcher grouped these data sets under the themes. To enhance validity (Alo Citation2020), the data sets and their corresponding themes should be scrutinized. This required using a team of experienced qualitative researchers to vet the data analysis process at this stage.

Reviewing the themes

Accordingly, the expertise of a team of three experienced qualitative researchers were involved for expert checks. Following each peer debriefing meetings with the researcher, acting as both critical friends (Kember et al. Citation1997) and research auditors (Filho and Rettig Citation2016), these well-trained qualitative researchers delivered constructive feedback (to the author) and which often showed a high degree of inter-rater reliability. In a handful of cases, a few data units had to be recoded and regrouped, until consensus was reached between the researcher and the team of three experienced qualitative researchers.

Re-definition and re-naming of themes

To ensure that the names for each regrouped and refined theme were well-defined and clarified (as suggested by the experienced qualitative researchers), the fifth step in the data analysis process involved redefining and renaming the themes. This process has helped this study to maximize each identified theme (Alo Citation2020). This will also help the readers understand the important relationship among these various constructs in study, and thus enhance the validity of the study.

Report writing

With validity reached, a good report writing was needed to ensure a further interpretation of the results. With the painstaking report writing (and coupled with the scrutiny by the team of three experienced qualitative researchers), this study has clarified the connections between the interview responses and the corresponding literature. This was done by moving forward and backward amidst the empirical data and the literature. Liu and Rong (Citation2015) recommend doing so to ensure an exhaustive and reliable data analyses and comparison between the findings and the dominant theory. An exhaustive report writing effort is also evidenced in a very strong literature review section, a relevant discussion section and a robust and quite insightful contributions of this research study.

Study findings

This section uses the raw interview data to examine if, and how, the learning-related actions of transformational supervisors impact store managers’ learning orientation and creativity in top supermarkets in Nigeria, South Africa and the UK. The findings and analysis offer fresh insight into the link between transformational supervision and new products/services development in the retail supermarket environment. Participants tended to focus on (1) how their supervisors support their personal interest and commitment toward developing competence (i.e., their learning orientation), (2) how their supervisors help them identify themselves as creative individuals (i.e., CRI), (3) and how their supervisors help them believe they possess the requisite capacity to “organize and execute the courses of action required to produce a given attainment” (i.e., CSE) (Bandura Citation1997, 3; Royston and Reiter-Palmon Citation2019). Based on this evidence, (4) the article constructs a very rich and highly nuanced understanding of the link between transformational supervision, new knowledge, and innovative approaches to problem-solving (Bass, Avolio, and Goodheim Citation1987; Bass and Steidlmeier Citation1999) and high-quality service and product standards that meet customers’ expectations (Hu, Kandampully, and Juwaheer Citation2009). To help make sense of the data, four themes relating to the data were simply deduced from the literature review section and termed transformational supervision and learning orientation; transformational supervision and creative role identity; transformational supervision and creative self-efficacy; and transformational supervision and creativity. Evidence from the data (as can be seen below) were found to match these themes. For clarity, the supervisors are the senior managers, while the store managers equate to an employee/subordinate/research participant.

Transformational supervision and learning orientation

As no intrinsic differences were identified while comparing participants’ responses from these three countries, we believe that combining the responses/samples would make more sense. Although the supermarkets are drawn from different countries (and which might imply different objectives, staffing compositions and operational strategies), participants commonly described how their supervisors utilize regular one to one dialogue, coaching sessions, and a range of skill acquisition opportunities to stimulate their personal interest and commitment toward developing competence. The quotes below also show that participants are very grateful about the level of developmental opportunities offered:

“I have been opportune to have many responsibilities and authorities delegated to me by my supervisor…I have also developed through mentoring and in-house coaching by my supervisor” (South African participant 5).

“I learn on the job, … and also through regular meeting and dialogue with the company’s board of directors” (Nigerian participant 3).

Although the development of learning-oriented individuals is dependent on a person’s drive to learn from important role models (Matsuo Citation2020, 6), specific behaviors of the manager has been linked with stronger leader-member exchange (LMX) relationship with individual subordinates (Duan et al. Citation2017; O’Donnell, Yukl, and Taber Citation2012). For instance, participants implicitly described their supervisors as important role models that encourage them to explore and acquire new knowledge and innovative approaches to problem-solving (at work) (Bass, Avolio, and Goodheim Citation1987; Bass and Steidlmeier Citation1999). This fosters creativity (Adil, Hamid, and Waqas Citation2020; Afsar and Masood Citation2018; Cai et al. Citation2021; Han and Bai Citation2020; Mielniczuk and Laguna Citation2020; Mittal and Dhar Citation2015):

“…For example, during his [i.e., his supervisor’s] visit earlier today we decided that we are going to introduce more Polish brands to suit the locals in the area that is covered by my store, as this area is quite ethnic…” (UK participant 2).

“… just last week my boss coached me on how to deal with unruly employees, difficult customers, and on other issues such as refunds, complaints, and enquiries, recording transactions and preventing losses on sales…” (South African participant 12).

Hu, Kandampully, and Juwaheer (Citation2009) also noted the crucial link between TS and subordinates’ ability to explore and deliver innovative results that meet customers’ expectations. This helps subordinates build confidence to perform beyond expectations:

“… during his monthly visits I normally walk around [the store] with my operations manager to identify things that need changing in the store (UK participant 2).

“I learn on the job and through personal coaching and mentoring by my senior manager …” (UK participant 1).

Jha and Bhattacharyya (Citation2013) had linked highly learning oriented individuals’ ability to go beyond the acceptable standard required for a day-to-day performance to their strong perseverance for continuous and long-term learning. One of the UK’s BIG four encourages such perseverance for continuous and long-term learning through their virtual community:

“…every store manager in this supermarket belongs to an online network of other store managers who have various experiences to contribute to the group’s learning…this is an initiative of our top management…and that is why everybody has to be a part of it” (UK participant 7).

This perhaps is not surprising as TSs encourage knowledge sharing (Mittal and Dhar Citation2015), collective and challenging (as against individual and routine) tasks (Rubin, Munz, and Bommer Citation2005), and which boosts subordinates’ self-confidence at work (Afsar and Masood Citation2018). However, this UK’s top supermarket also emphasizes performance orientation, through their options programme. The options programme is an inhouse leadership development programme that identifies and rewards highly talented employees through a blend of on-the-job and off-the-job learning opportunities and development programmes to Fastrack their career progressions:

“…as employees are doing what they are assigned as their tasks, managers identify the strongest members of their team [i.e., in terms of individual performance] and recommend such employee for partaking in the options programme so they could be trained to become store managers” (i.e., individualized consideration) (UK participant 8).

Still referring to the options programme, another participant adds:

“In the Options Programme, the participants are first taken to an assessment centre where they spend a full day doing group activities and interviews… Then if they are selected to continue the programme, they would spend the next six months to undergo leadership development sessions, and which include both on-the-job and off-the-job learning” (UK participant 9).

Previous studies also found that highly learning oriented individuals are encouraged and empowered to develop (Gray Citation2005), are offered the freedom and autonomy to learn from their jobs (Dalakoura Citation2010), and are rated highly by their supervisors during performance appraisals (Gong, Huang, and Farh Citation2009; Wang, Tsai, and Tsai Citation2014). Through vicarious reinforcement (Bandura Citation1997), such a high level of support can foster creativity.

Transformational supervision and creative role identity (CRI)

Our analysis also illustrates how transformational supervision helps participants identify and analyze the required changes in their businesses, to device plans, and to control resources to implement such required changes:

“On a weekly basis, I do have meetings with our top management …it involves sitting down to do some evaluations and analysis of previous performances and results and looking into the foreseeable future to forecast future performances and results” (South Africa participant 9).

“I have now realised that delegating some of my responsibilities and authorities to my subordinates allows the business to grow, as it creates some time for me to concentrate on more pressing issues” (South African participant 7). Research links TS’s influence on follower’s work-life management to job autonomy, job enrichment, improved work-family balance, and thus a reduced work-family conflict (Hammond et al. Citation2015) due to a reduced work-to-family spill over (Isenhour, Stone, and Lien Citation2012).

“…the moment I discovered that there are many Asians in the area that is covered by my store I discussed with my team how we should change the store to suit the needs of this special group of customers…” (UK participant 3).

These quotes above typify the role of TS in nurturing subordinates’ CRI. Adil, Hamid, and Waqas (Citation2020), Afsar and Masood (Citation2018), Han and Bai (Citation2020), Mielniczuk and Laguna (Citation2020) and Mittal and Dhar (Citation2015) also emphasize the crucial role of TS in nurturing subordinates’ ingenuity, and thus, helping them deliver creative outcomes. Participants were also prone to comparing their present capabilities with their previous, and which makes them identify and appreciate the degree they believe they have been transformed:

“…I have learnt that in every new environment a manager needs to first identify who their customers are and what their needs are…” (UK participant 3).

“In the Options programme we were taught that each store is unique, so you have to treat each differently depending on the major ethnic setting served by the sore…” (UK participant 9).

“…I am now more capable of guiding my staff on the right paths, even when we are dealing with complex problems” (South African participant 4).

The above quotes have revealed that, by stimulating subordinates’ intellectual curiosity and encouraging them to devise innovative approaches to problem-solving, TS facilitates subordinates’ ability to device high quality product and service that meet customers’ expectations (Hu, Kandampully, and Juwaheer Citation2009), and which is particularly crucial in complex and challenging job roles, such as the supermarkets store managers.

Transformational supervision and creative self-efficacy (CSE)

Although participants now identify themselves as creative individuals, regular and supportive supervision is crucial in boosting their confidence to generate creative results. The quotes below reveal how regular dialogue with their supervisors has evoked the self believe (in participants) that they are creative, and which epitomizes the role of TS in boosting subordinates’ CSE:

“… I often identify where and when necessary actions such as expansion or relocation are needed, or areas that will bring development to the staff or satisfaction to the customers… I also brief the top management on areas that need improvement” (South African participant 7).

“I regularly review the skill set of my team…each time I identify a skill gap I don’t hesitate to advise the top management…” (Nigerian participant 5).

Transformational supervision is crucial in boosting subordinates’ confidence to generate creative results (e.g., Han and Bai Citation2020; Mielniczuk and Laguna Citation2020), and which echoes Bandura (Citation1997) theorizing on helping subordinates belief in their own capacity to “organize and execute the courses of action required to produce a given attainment” (p. 3). Gong, Huang, and Farh (Citation2009) also found highly learning-oriented individuals as having higher CSE when under the influence of TSs. Specifically, TSs have been linked with subordinate’s personal control, creative personality, and thus creativity (Tse, To, and Chiu Citation2018). Evidence from the interview responses below also shows participants must regularly brief their supervisors on each problem or opportunity identified. Although the impact of such a learning culture on creativity might go unnoticed, it can be a powerful stimulus for CSE, as SMs will be intellectually stimulated to think about each issue in a novel way prior to briefing their supervisors. Thereby, resulting in high problem solving (Han and Bai Citation2020) and high creativity (e.g., Adil, Hamid, and Waqas Citation2020; Afsar and Masood Citation2018; Cai et al. Citation2021; Han and Bai Citation2020; Mielniczuk and Laguna Citation2020; Mittal and Dhar Citation2015):

“…I try to figure out our business’s key strengths (i.e., whether it is in our brand, price, etc.) so we can build and capitalize on such assets while facing stronger rivalry… I therefore translated such vision into a plan that I shared with my staff and management team during our monthly meeting…” (South African Participant 10).

“… I visit similar stores to learn from them… in turn I convert the result of such visits into a plan which I share with my top management and staff…” (Nigeria participant 4).

“… I anticipate the future needs of the store on daily basis, and I translate the results of such forecasting into an agenda which I share with staff and management…” (Nigerian participant 1).

As the quotes illustrate, by making followers believe they possess the requisite capability to generate creative results at work, TS can enhance subordinates’ self-confidence at work (Afsar and Masood Citation2018). By helping followers attain such high CSE levels (Walumbwa and Hartnell Citation2011), TS, is thus a precursor of high creativity (Gong, Huang, and Farh Citation2009; Mittal and Dhar Citation2015, 896).

Transformational supervision and employee creativity

Participants link a wide range of skills—team-leading, performance management, visioning, and interpersonal relationships developed—to high quality supervision received. This epitomizes TS as key to employee creativity. The below quotes also illustrate how these skill sets are impacting on organizational performance:

“…ever since I rediscovered some aspects of my personal life such as my temperament and I have received support… my subordinates have been sharing their views freely with me without fear of being reprimanded, unlike before” (Nigerian participant 7).

“…unlike before I am now able to forecast sales and if any changes are noticed I will prepare my team in readiness for such change” (South African participant 7).

“…I have learnt to always make sure that my stores are up to the standard and everything are at their right places…” (UK participant 5).

…, I try to figure out our business’s key strengths i.e., whether it is in our brand, price, etc. so we can build and capitalize on such assets while facing stronger rivalry…” (South African Participant 10).

Some also attributed positive personal changes—particularly self-awareness, self-efficacy (Bandura Citation1997; Royston and Reiter-Palmon Citation2019), locus of control (Afsar and Masood Citation2018) and adaptability—to high level of support and regular interactions with their supervisors. The below quotes also illustrate how such new values have resulted in a new culture of a more collaborative working approach. Thereby, a resultant improvement in team performance:

“…unlike before, now I think deeper before taking actions… I always go back and ask myself, what are my doing that can move this business forward, are my carrying the team along with me to be able to do that with me?” (UK participant 6).

“Through the options programme I have learnt that every new environment requires a manager to adapt by thinking deeper in order to provide the stores that will satisfy the major ethnic setting that dominates such environment so you can move the business forward” (UK participant 8).

“… I have been able to identify the quickest growth areas, the shrinkage areas and the stagnated areas in my store and as a result the team goes into further brainstorming…” (UK participant 7).

Although the creativity literature posit that learning-oriented individuals are driven by self-regulation (Wang, Tsai, and Tsai Citation2014), our analysis has shown that effective supervisory support and role-modeling can boost their creativity level (Adil, Hamid, and Waqas Citation2020; Afsar and Masood Citation2018; Cai et al. Citation2021; Han and Bai Citation2020; Mielniczuk and Laguna Citation2020; Mittal and Dhar Citation2015). This is also consistent with the social cognitive theory (Bandura Citation1986), which is the foundation for creative behavior and high-level self-efficacy (Gong, Huang, and Farh Citation2009; Tse, To, and Chiu Citation2018), and which can have long-term impact on business’s performance:

“…I have realised that shoppers are now making very cute choices regarding their shopping…they have become very sensitive about where, when and what they shop unlike in five years ago…and they are now generally not seen carrying big baskets about, because they are shopping more often…and I need to be evolving with them so we would be heading in the same direction” (UK participant 9).

“… the first time I realised that customers are now shopping more often today than they used to do in the past 5 years or so, I translated such knowledge into a plan which I shared with my team… in order to change with the customers shopping habit…” (UK participant 5).

“… I have been able to identify the quickest growth areas, the shrinkage areas and the stagnated areas in my store and as a result the team goes into further brainstorming, and at times, colleagues undergo further training and development sessions such as, on-the-job coaching, or booking someone on a course to do, or simply briefing the whole team as a result of that” (UK participant 7).

From these empirical viewpoints, we have seen how TSs can stimulate SMs’ creative thinking and their ability to generate novel solutions to problems, and which are key to building and maintaining a competitive advantage in a dynamic environment (like the supermarkets’) (Amabile et al. Citation2005; George Citation2007).

Discussion

This study sought to enhance our understanding of how the learning-related actions of TSs influence subordinates’ learning orientation and creativity. The study found that transformational supervision fosters supermarket SMs’ learning orientation, creative role identity (CRI) and creative self-efficacy (CSE), and thus helps SMs develop novel products, processes, procedures, and services that meet customers’ expectations. This aspect links transformational supervision to employee creativity (Cai et al. Citation2021, Citation2019), and from our findings we can infer a logical sequence of how such a relationship develops.

First, as important role models (Matsuo Citation2020, 6) TSs utilize regular one to one dialogue and a wide range of learning and development interventions to stimulate SMs’ personal interest and commitment to learn and explore. Such quality of support epitomizes the role of TSs in developing subordinates’ learning orientation (Hu, Kandampully, and Juwaheer Citation2009). Moreover, participants from one of the British supermarkets that participated in the study reveal that their supervisors utilize performance orientation. This is done by identifying highly learning oriented individuals and rewarding them through a blend of on-the-job and off-the-job learning and development opportunities to Fastrack their career progressions. Through vicarious reinforcement (Bandura Citation1997), such a high level of support can foster creativity.

Secondly, as participants frequently compared their present capabilities with their previous, they were quick to identify how creative they now are. For instance, they revealed they can now analyze the required changes in their businesses, devise plans, and control resources to implement such required changes, and in a manner that meets customers’ expectations (Hu, Kandampully, and Juwaheer Citation2009). This typifies the role of TSs in nurturing subordinates’ CRI (Tierney and Farmer Citation2002).

Thirdly, participants must brief their supervisors regularly on the situations in their stores. Such a learning culture not only challenges current established ways of knowing but opens a creative space for radical learning to take place (Bosma, Chia, and Fouweather Citation2016), as participants are challenged to think about each issue in a novel way, and thus results in high problem solving (Han and Bai Citation2020), high creativity (e.g., Adil, Hamid, and Waqas Citation2020; Afsar and Masood Citation2018; Cai et al. Citation2021; Han and Bai Citation2020; Mielniczuk and Laguna Citation2020; Mittal and Dhar Citation2015), self-efficacy (Christensen-Salem et al. Citation2020) and locus of control (Bandura Citation1997; Royston and Reiter-Palmon Citation2019; Tse, To, and Chiu Citation2018). This demonstrates how TSs can help subordinates’ belief in their own capacity to “organize and execute the courses of action required to produce a given attainment” (Bandura Citation1997, 3), and which epitomizes the role of TS as key to subordinates’ CSE (Adil, Hamid, and Waqas Citation2020; Afsar and Masood Citation2018; Cai et al. Citation2021; Han and Bai Citation2020; Mielniczuk and Laguna Citation2020; Mittal and Dhar Citation2015).

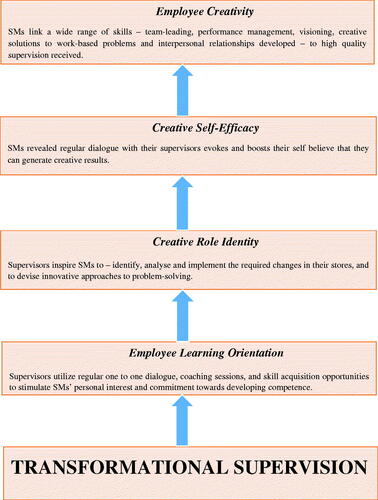

Finally, participants revealed a wide range of skills developed—team-leading, performance management, visioning, interpersonal relationships, self-awareness, and adaptability—and which they linked to the quality of supervision received. This relationship is illustrated in .

These findings symbolize the role of TSs in fostering SMs’ creativity (Cai et al. Citation2019; Tse, To, and Chiu Citation2018), and which are key to building and maintaining a competitive advantage in a dynamic environment (like the supermarkets’) (Amabile et al. Citation2005; George Citation2007).

Conclusions and implications

The present study was motivated by Gong, Huang, and Farh (Citation2009, 774–775) call for research that explores how the learning-related actions of the transformational supervisors impact subordinates’ learning orientation and creativity. Using five theoretical lenses—transformational supervision, learning orientation, CRI, CSE and creativity—the study has shown that transformational supervision impacts subordinates’ ability to devise creative solutions to work-based problems. The study found that, by fostering SMs learning orientation, by helping them identify themselves as creative persons (i.e., CRI), and by helping them believe they can bring resources to bear to produce innovative results (i.e., CSE) (Adil, Hamid, and Waqas Citation2020; Christensen-Salem et al. Citation2020), TSs are helping SMs develop novel products and services that meet customers’ expectations in these supermarkets that participated in this study from both continents. With these empirical results, this study provides a baseline for supermarkets in (re)evaluating the significance of their leadership styles on follower creativity. Since the transformational leadership style can result in better ways of meeting customers’ expectations, it is key to a sustained competitive advantage (Bass and Avolio Citation1990, Citation1994). Therefore, the need for supervisors to be trained to build good working relationship with each subordinate, as this is the foundation for effective and transformational supervision, hence employee creativity and organizational performance.

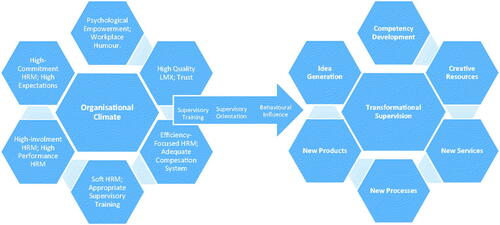

By enlightening the process through which transformational supervision could have such a significant impact on subordinate creativity, these findings have implications for leadership/management behavior, as well as leadership/management development, and more generally how HR can build organizational climate for creativity in supermarkets. By encouraging workplace humor (e.g., Lang and Lee Citation2010), conducive physical work environment (e.g., Hoff and Öberg Citation2015), knowledge transfer (e.g., Zhang and Begley Citation2011), high-involvement HRM practices (e.g., Shin, Jeong, and Bae Citation2018) and high-performance human resource practices (e.g., van Esch, Wei, and Chiang Citation2018), HR can foster employee creativity. The HR literature also suggests individual initiative, skill variety, knowledge specificity and creative resources (e.g., Chen, Shih, and Yeh Citation2011). Shalley, Zhou, and Oldham (Citation2004) link these characteristics to idea generation, and which results in new products, services, and processes, and which are key to sustained competitive advantage in a dynamic environment, such as the supermarket sector studied here.

Furthermore, by fostering appropriate HRM cultures, practices, and key behaviors (Smith et al. Citation2012), such as psychological empowerment (Gumusluoglu and Ilsev Citation2009), and by liberating (rather than controlling) humor (Lang and Lee Citation2010), supervisors can build trust and boost the perceived relationship with subordinates (Bennis Citation2007). Embedding trust and empowerment in a supervisory relationship (e.g., Schuler and Jackson Citation1987), through behaviors that promote good interpersonal relationships (e.g., Qu, Janssen, and Shi Citation2017) is also at the heart of high quality LMX relationship. The creativity literature (e.g., Chen, Shih, and Yeh Citation2011; Shalley, Zhou, and Oldham Citation2004) also links high quality LMX relationship to creative resources, idea generation, new products, services, and processes, and which are key to sustained competitive advantage in a dynamic environment, such as the supermarket sector studied here. HR also needs to encourage supervisors to be setting high (rather than low) expectations (Qu, Janssen, and Shi Citation2017), as this creates challenge (rather than hindrance) stressors, and which Ren and Zhang (Citation2015) found as antecedents of employees’ idea generation.

Other HRM practices relevant to employee learning orientation and creativity include high-commitment HRM practices (McClean and Collins Citation2011) with adequate compensation system that encourages and rewards creative behaviors (Yoon and Chae Citation2012). Through vicarious reinforcement (Bandura Citation1997), such high-commitment HRM system can be crucial in nurturing employee learning orientation and creativity. Other HR practices found to foster idea generation include investing in efficiency focused HRM (Huang and Kim Citation2013), and which is evidenced through sophistication in their use of training (Simsek et al. Citation2009). This can be crucial in nurturing the appropriate capabilities (Ahammad et al. Citation2015) and cognitive abilities (Huang and Kim Citation2013), which are key to new products, services, and processes development, and which are key to sustained competitive advantage in a dynamic environment, such as the supermarket sector studied here.

Although Chakrabarti et al. (Citation2014) found a positive relationship between soft HRM approach, supportive supervision, and employee creativity, drawing on the path-goal theory, earlier studies (e.g., House and Dessler Citation1974) found that a supervisor's effect on employee creativity depends on the characteristics of the individual employee. Similarly, Kohli (Citation1989) also suggests that more experienced employees might be less responsive to supervisory intervention than the relatively inexperienced ones. This suggests a varying level of supervisory behavioral influence on employee creativity, based on employees’ experience level. Further research is therefore needed to establish if, how, and when to vary/tailor supervisory orientation to match individual employee’s experience level, to enhance creative outcome. Deduced from the discussions above, illustrates transformational supervision at the very heart of employee learning orientation and employee creativity.

Limitations of the study and future research directions

Our article does have limitations like in any academic study. Firstly, our research did not unpack how supervisors can be prepared and encouraged to take active interest in the personal (in addition to the professional) development of the employees. Therefore, future research should examine how mentoring functions can be embedded in the supervisory training, such that supervisors are aware that professional and personal developmental needs of their protégé can conjoin. Despite the significance of supervisors who mentor, their presence should be complemented with formal mentoring programmes in organizations. Hence, the future studies can explore the interlinkage between these aspects. Furthermore, our research has not examined the crucial roles of the supervisor’s warmth, humility, emotional intelligence, communication skills, capacity for intimacy, cognitive complexity, competencies (e.g., awareness of the protégé’s developmental stage, self-awareness, cross race and cross-gender skills) and diligence in safeguarding the supervisee’s best interests (Johnson Citation2007). Therefore, future research should explore how to improve supervisory training and supervisee matching, as this will minimize constant nervousness on the part of the protégé, and thus enhance subordinate’s creativity. Finally, the future research can also explore how the pair in a supervisor-supervisee relationship are made aware of when, and how to seek consultation when professional and/or personal boundaries are poorly defined or are becoming porous. Hence, there is a need for more research in different contexts on relationship styles in supervisor-supervisee relationship.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Obinna Alo

Obinna Alo is a Senior Lecturer in Leadership and Management in the Business School at Edge Hill University United Kingdom (UK). Dr Alo received his PhD in Human Resource Development from the University of Sunderland, UK. His earlier research has been published in different academic journals including Africa Journal of Management and International Journal of Organizational Analysis. He regularly reviews for top ranked management journals. He has also taught in many top UK Universities. He is currently an external examiner for Lancaster University and the University of Chester, in the UK.

Sir Cary Cooper

Sir Cary L. Cooper is 50th Anniversary Professor of Organizational Psychology and Health, Manchester Business School, University of Manchester, UK. Prof. Cooper is the author/editor of over 120 books (on resilience, mergers and acquisitions, etc.) and over 400 scholarly articles. He is currently Founding Editor of Journal of Organizational Behavior and Editor-in-Chief of Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance. He served as a guest editor for special issues at Journal of Management Studies, Human Resource Management, International Journal of Human Resource Management, and others. Prof. Cooper's work has been published in such journals as Academy of Management Journal, Journal of Management, Academy of Management Executive, Personnel Psychology, Journal of Management Studies, Human Resource Management, Human Relations, British Journal of Management, Management Learning, Management International Review, and others. He is a Fellow of the British Psychological Society and an Academician of the Academy of Social Sciences. Professor Cooper is past President of the British Academy of Management and one of the first UK based Fellows of the US Academy of Management (AOM). In 2001, he was awarded a CBE in the Queen's Birthday Honors List. In June 2014 he was awarded a Knighthood for his services to social science.

Ahmad Arslan

Ahmad Arslan is currently working as a Professor at Department of Marketing, Management and International Business, University of Oulu, Finland. He also holds the position of Honorary at the Business School, University of Aberdeen, Scotland, UK. His earlier research has been published in prestigious academic journals like British Journal of Management, Human Resource Management (US), IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, International Business Review, International Marketing Review, Journal of Business Research, Journal of International Management, Journal of Knowledge Management, Production Planning & Control, Supply Chain Management, Technological Forecasting and Social Change, and Scandinavian Journal of Management among others. Finally, he holds several editorial board memberships and is currently a Senior Editor of International Journal of Emerging Markets (Emerald).

Shlomo Tarba

Prof. Shlomo Tarba is the Chair (Full Professor) and the former Head of Department of Strategy and International Business at the Business School, University of Birmingham, UK. Prof. Tarba is a Fellow of the Academy of Social Sciences. He is an Associate Editor of Human Resource Management Review and Journal of Product Innovation Management. He has served as a Guest-Editor for the special issues at Journal of Organizational Behavior (US, Wiley), Human Resource Management (US), California Management Review, Journal of Product Innovation Management, International Business Review, and Management International Review. His research interests include cross-border mergers and acquisition resilience, agility, and organizational ambidexterity. Prof. Tarba’s research papers are published/forthcoming in journals, such as Journal of Management (SAGE), Long Range Planning, Academy of Management Perspectives, Journal of Organizational Behavior, Human Relations, Human Resource Management (US, Wiley), British Journal of Management, Journal of Product Innovation Management, Journal of World Business, Management International Review, International Business Review, Journal of Corporate Finance, International Journal of Production & Economics, and others.

References

- Adil, M. S., K. B. A. Hamid, and M. Waqas. 2020. “Impact of Perceived Organisational Support and Workplace Incivility on Work Engagement and Creative Work Involvement: A Moderating Role of Creative Self-Efficacy.” International Journal of Management Practice 13 (2):117–150. doi:10.1504/IJMP.2020.105671.

- Afsar, B., and M. Masood. 2018. “Transformational Leadership, Creative Self-Efficacy, Trust in Supervisor, Uncertainty Avoidance, and Innovative Work Behavior of Nurses.” The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science 54 (1):36–61. doi:10.1177/0021886317711891.

- Ahammad, M. F., S. M. Mook Lee, M. Malul, and A. Shoham. 2015. “Behavioural Ambidexterity – the Impact of Financial Incentives on Employee Motivation, Productivity and Performance of Commercial Bank.” Human Resource Management 54 (S1):S45–S62. doi:10.1002/hrm.21668.

- Alo, O. 2020. “Lost in Transfer? Exploring the Influence of Culture on the Transfer of Knowledge Categories.” Africa Journal of Management 6 (4):350–376. doi:10.1080/23322373.2020.1830696.

- Amabile, T. M. 1983. “The Social Psychology of Creativity: A Componential Conceptualization.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 45 (2):357–376. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.45.2.357.

- Amabile, T. M. 1988. “A Model of Creativity and Innovation in Organisations.” Research in Organisational Behaviour 10 (1):123–167.

- Amabile, T. M. 1996. Creativity in Context. Boulder, CO: Westview.

- Amabile, T. M., S. G. Barsade, J. S. Mueller, and B. M. Staw. 2005. “Affect and Creativity at Work.” Administrative Science Quarterly 50 (3):367–403. doi:10.2189/asqu.2005.50.3.367.

- Amabile, T. M., E. A. Schatzel, G. B. Moneta, and S. J. Kramer. 2004. “Leader Behaviors and the Work Environment for Creativity: Perceived Leader Support.” The Leadership Quarterly 15 (1):5–32. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2003.12.003.

- Archibong, B. 2019. “Explaining Divergence in the Long-Term Effects of Precolonial Centralization on Access to Public Infrastructure Services in Nigeria.” World Development 121 (1):123–140. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.04.014.

- Bandura, A. 1986. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Bandura, A. 1997. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York, NY: W.H. Freeman.

- Barnes-Dabban, H., K. Van Koppen, and A. Mol. 2017. “Environmental Reform of West and Central Africa Ports: The Influence of Colonial Legacies.” Maritime Policy & Management 44 (5):565–583. doi:10.1080/03088839.2017.1299236.

- Bartels, J., M. J. Reinders, and M. Van Haaster-De Winter. 2015. “Perceived Sustainability Initiatives: Retail Managers’ Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motives.” British Food Journal 117 (6):1720–1736. doi:10.1108/BFJ-11-2014-0362.

- Bass, B. M. 1985. Leadership and Performance beyond Expectations. New York, NY: Free Press.

- Bass, B. M., and B. J. Avolio. 1990. “The Implications of Transactional and Transformational Leadership for Individual, Team, and Organisational Development.” Research in Organizational Change and Development 4:231–272.

- Bass, B. M., and B. J. Avolio. 1994. Improving Organisational Effectiveness through Transformational Leadership. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Bass, B. M., B. J. Avolio, and L. Goodheim. 1987. “Biography and the Assessment of Transformational Leadership at the World-Class Level.” Journal of Management 13 (1):7–19. doi:10.1177/014920638701300102.

- Bass, B. M., and P. Steidlmeier. 1999. “Ethics, Character, and Authentic Transformational Leadership Behaviour.” The Leadership Quarterly 10 (2):181–217. doi:10.1016/S1048-9843(99)00016-8.

- Bechky, B. A., and G. A. Okhuysen. 2011. “Expecting the Unexpected? How SWAT Officers and Film Crews Handle Surprises.” Academy of Management Journal 54 (2):239–261. doi:10.5465/amj.2011.60263060.

- Bennis, W. 2007. “The Challenges of Leadership in the Modern World: Introduction to the Special Issue.” American Psychologist 62 (1):2–5. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.62.1.2.

- Benoit, S., H. Evanschitzky, and C. Teller. 2019. “Retail Format Selection in on-the-Go Shopping Situations.” Journal of Business Research 100:268–278. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.04.007.

- Bingham, C. B., and K. M. Eisenhardt. 2011. “Rational Heuristics: What Firms Explicitly Learn from Their Process Experience.” Strategic Management Journal 32 (13):1437–1464. doi:10.1002/smj.965.

- Boerner, S., S. A. Eisenbeiss, and D. Griesser. 2007. “Follower Behavior and Organisational Performance: The Impact of Transformational Leaders.” Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies 13 (3):15–26. doi:10.1177/10717919070130030201.

- Bosma, B., R. Chia, and I. Fouweather. 2016. “Radical Learning through Semantic Transformation: Capitalizing on Novelty.” Management Learning 47 (1):14–27. doi:10.1177/1350507615602480.

- Bouffard, T., J. Boisvert, C. Vezeau, and C. Larouche. 1995. “The Impact of Goal Orientation on Self-Regulation and Performance among College Students.” British Journal of Educational Psychology 65 (3):317–329. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8279.1995.tb01152.x.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2):77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Bunderson, J. S., and K. M. Sutcliffe. 2003. “Management Team Learning Orientation and Business Unit Performance.” The Journal of Applied Psychology 88 (3):552–560. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.3.552.

- Burt, S. 2010. “Retailing in Europe: 20 Years On.” The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research 20 (1):9–27. doi:10.1080/09593960903497773.

- Cai, W., L. Lin, C. Yang, and X. Fan. 2021. “Does Participation Generate Creativity? A Dual-Mechanism of Creative Self-Efficacy and Supervisor-Subordinate Guanxi.” European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 30 (4):541–554. doi:10.1080/1359432X.2020.1864329.

- Cai, W., E. I. Lysova, S. N. Khapova, and B. A. G. Bossink. 2019. “Does Entrepreneurial Leadership Foster Creativity among Employees and Teams? the Mediating Role of Creative Efficacy Beliefs.” Journal of Business and Psychology 34 (2):203–217. doi:10.1007/s10869-018-9536-y.

- Carroll, M. 2009. “From Mindless to Mindful Practice: On Learning Reflection in Supervision.” Australian Journal of Psychotherapy 15 (4):38–49.

- Carroll, M. 2010. “Supervision: Critical Reflection for Transformational Learning (Part 2).” The Clinical Supervisor 29 (1):1–19. doi:10.1080/07325221003730301.

- Chakrabarti, R., B. R. Barnes, P. Berthon, L. Pitt, and L. L. Monkhouse. 2014. “Goal Orientation Effects on Behavior and Performance: Evidence from International Sales Agents in the Middle East.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management 25 (2):317–340. doi:10.1080/09585192.2013.826915.

- Chamorro-Premuzic, T. 2006. “Creativity versus Conscientiousness: Which is a Better Predictor of Student Performance?” Applied Cognitive Psychology 20 (4):521–531. doi:10.1002/acp.1196.

- Chen, C., H. Shih, and Y. Yeh. 2011. “Individual Initiative, Skill Variety, and Creativity: The Moderating Role of Knowledge Specificity and Creative Resources.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management 22 (17):3447–3461. doi:10.1080/09585192.2011.599940.

- Christensen-Salem, A., F. O. Walumbwa, C. I. C. Hsu, E. Misati, M. T. Babalola, and K. Kim. 2021. “Unmasking the Creative Self-Efficacy–creative Performance Relationship: The Roles of Thriving at Work, Perceived Work Significance, and Task Interdependence.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management 32 (22):4820–4846. doi:10.1080/09585192.2019.1710721.

- Churchill, S. 2013. “Transformational Supervision.” Therapy Today 24 (6):33–35.

- Creswell, J. W. 2007. Qualitative Inquiry and Design. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Dalakoura, A. 2010. “Differentiating Leader and Leadership Development.” Journal of Management Development 29 (5):432–441. doi:10.1108/02621711011039204.

- Davis, J. P., and K. M. Eisenhardt. 2011. “Rotating Leadership and Collaborative Innovation: Recombination Processes in Symbiotic Relationships.” Administrative Science Quarterly 56 (2):159–201. doi:10.1177/0001839211428131.

- Dawson, J. 2001. “Is There a New Commerce in Europe?” The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research 11 (3):287–299. doi:10.1080/713770598.

- Duan, J., C. Li, Y. Xu, and C.-H. Wu. 2017. “Transformational Leadership and Employee Voice Behavior: A Pygmalion Mechanism.” Journal of Organizational Behavior 38 (5):650–670. doi:10.1002/job.2157.

- Dweck, C. S. 1986. “Motivational Process Affecting Learning.” American Psychologist 41 (10):1040–1048. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.41.10.1040.

- Dweck, C. S. 2000. Self-Theories: Their Role in Motivation, Personality, and Development. Philadelphia, PA: Psychological Press.

- Dweck, C. S., and E. L. Leggett. 1988. “A Social-Cognitive Approach to Motivation and Personality.” Psychological Review 95 (2):256–273. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.95.2.256.

- Eisenhardt, K. M. 2021. “What is the Eisenhardt Method, Really?” Strategic Organization 19 (1):147–160. doi:10.1177/1476127020982866.

- Eisenhardt, K. M. 1989a. “Building Theories from Case Study Research.” The Academy of Management Review 14 (4):532–550. doi:10.2307/258557.

- Eisenhardt, K. M. 1989b. “Making Fast Strategic Decisions in High-Velocity Environments.” Academy of Management Journal 32 (3):543–576.

- Elkins, T., and R. T. Keller. 2003. “Leadership in Research and Development Organisations: A Literature Review and Conceptual Framework.” The Leadership Quarterly 14 (4–5):587–606. doi:10.1016/S1048-9843(03)00053-5.