Abstract

Building on person-supervisor fit and implicit leadership theories, we examined the effect of the fit between expected and observed leadership behaviors on employee satisfaction in a cross-cultural context. The data we analyzed had been collected from 237 Chinese employees who reported directly to 40 expatriate senior managers. The results of the polynomial regression analyses and response surface modeling showed that a high degree of fit was associated with a high degree of supervisor satisfaction and that such satisfaction was higher when the expected and observed leadership behaviors exhibited a high level of alignment. Our study’s theoretical contributions and practical implications are discussed.

Introduction

Implicit leadership theories suggest that a good match between the leadership behaviors exhibited by leaders and those expected by their followers can yield higher degrees of employee satisfaction and performance (Lord, Foti, and Phillips Citation1982; Lord and Maher Citation2002; House et al. Citation2013; Herd and Lowe Citation2020). Most research on leader-follower congruence, however, has focused on value, goal, and personality similarities (see, e.g., Audenaert et al. Citation2018; Xu et al. Citation2019; Qin et al. Citation2021; Yue, Men, and Ci Citation2022), while little research has empirically examined the effect on employee outcomes of the fit between expected/needed and observed/received leadership behaviors (Lambert et al. Citation2012), particularly in cross-cultural contexts. As a result, little is known about how the fit between the leadership behaviors that are expected by host country nationals (HCNs) and those actually demonstrated by their expatriate supervisors is associated with employee outcomes.

Research on leadership behavior fit in cross-cultural settings, however, is not needless, given that favorable employee outcomes can result from leaders demonstrating leadership behaviors that match their followers’ expectations (House Citation1971; Masterson and Lensges Citation2015; Yukl Citation2019) and that expatriate supervisor behaviors shape the daily work experience of HCNs and thus can influence their attitudes (Lord and Brown Citation2001; Yukl Citation2019). Empirical research has shown that the expectations and attitudes held by HCNs toward expatriate managers differ from those they have toward local ones (Templer Citation2010; Varma, Budhwar, and Pichler Citation2011; Ciuk and Schedlitzki Citation2022); as such, the effect of the fit between expected and observed leadership behaviors on employee attitudes in the expatriate manager-HCNs dyad may differ from that in the local manager-local employee one. It is thus important, from both the theoretical and practical perspectives, to investigate the relationship between the fit in leadership behaviors and employee work outcomes in cross-cultural settings.

In this study, we examined the effect on employee satisfaction of the fit between expected and observed leadership behaviors in a cross-cultural context. Specifically, drawing from person-supervisor fit and implicit leadership theories, we developed and tested hypotheses pertaining to the effect on job and supervisor satisfaction of the fit between the expatriate manager leadership behaviors expected and observed by HCNs. Moreover, we explored the relationship between different levels of fit (low and high) and employee satisfaction. Our data were collected from 237 Chinese employees who reported directly to 40 expatiate senior managers. We chose to study Chinese employee expectations in regard to the leadership behaviors of their expatriate managers because China is among the top countries for international assignments and is a strategic destination for the international business ventures of many multinational corporations (MNCs) (Luo Citation2007; Enright Citation2016; Grosse, Gamso, and Nelson Citation2021).

Our study contributes to the existing literature in three main ways. First, it contributes to the person-environment (PE) fit literature by examining the person–supervisor (PS) fit with a focus on the fit between expected and observed leadership behaviors. Although the PE fit is the object of a prominent stream of research in the fields of management and psychology, research on the PS fit has hitherto been relatively limited (Kristof‐Brown, Zimmerman, and Johnson Citation2005; Guay et al. Citation2019).

Second, our study contributes to the leader-follower congruence literature by examining the fit between expected and observed leadership behaviors and extending it to cross-cultural settings, which, as stated above, has hitherto been the subject of limited research. In addition, we examined how fit, at different levels, is related to employee satisfaction. This comparison provided us with an opportunity to gain a better understanding of different patterns of congruence effects.

Third, our findings provide practical insights into Chinese employee expectations and satisfactions in relation to leadership behaviors. As the second largest economy in the world, China has attracted a vast amount of foreign investment, and a great number of expatriates are currently working there. Our findings would help expatriate business leaders understand what leadership behaviors they should adopt when working in China to enhance the satisfaction of their Chinese subordinates.

In the sections that follow, we first discuss the two leadership behavior categories and the indicators of employee satisfaction examined in our study. We then present our review of the theories and literature concerning the PE fit and leader-follower congruence, which helped us formulate our hypotheses. We then follow with sections that describe the research methods, report the results of the hypotheses’ testing, and discuss the contributions and implications of the study.

Theoretical groundings and hypotheses

Leadership behaviors and employee satisfaction

Leadership behaviors concern the actions managers undertake in carrying out their roles. Leadership research has most widely focused upon the two categories of task- and relations-oriented leadership behaviors. Task-oriented behaviors, which are mainly aimed at the efficient improvement or accomplishment of tasks (Vroom and Jago Citation2007; Yukl Citation2013; Heimann, Ingold, and Kleinmann Citation2020; Dinić et al. Citation2023), include behaviors, such as organizing and planning work activities, assigning tasks, setting priorities, and monitoring operations and performance to improve efficiency. Relations-oriented behaviors, which are mainly concerned with the establishment of mutual trust, cooperation, commitment, and job satisfaction (Yukl Citation2013; Heimann, Ingold, and Kleinmann Citation2020), include behaviors, such as providing support and encouragement, showing trust and respect, consulting with subordinates, empowering people, and providing coaching and mentoring (Fleishman Citation1953; Vroom and Jago Citation2007; Yukl Citation2019).

Many of the studies conducted in the field of leadership have examined the relationship between leadership behaviors and leader effectiveness (see, e.g., House Citation1971; Argyris and Argyris Citation1976; Zaccaro et al. Citation1991; Yukl Citation2019; Ishaq, Bashir, and Khan Citation2021; Weber, Büttgen, and Bartsch Citation2022). The key proposition holds that leaders can influence individuals and groups by adopting the two types of behaviors reviewed above. In this regard, the most commonly used leader effectiveness indicators are subordinate satisfaction, commitment, and performance (see, e.g., House Citation1971, Citation1996; Bushra, Ahmad, and Naveed Citation2011; Yang, Zhang, and Tsui Citation2010; Ozturk, Karatepe, and Okumus Citation2021; Mifsud Citation2023). Other indicators, such as team and organizational performance, and leader contributions to group process quality have also been used, albeit to a lesser extent (Yukl Citation2013).

Our study examined how the degree of fit between expected and observed task- and relations-oriented leadership behaviors is associated with employee satisfaction. We examined these two categories of leadership behaviors because recent meta-analytic results have shown that they are related to leadership effectiveness criteria (e.g., follower satisfaction and leader job performance) and that they are important and valid for leadership research (see Judge, Piccolo, and Ilies Citation2004; DeRue et al. Citation2011; Heimann, Ingold, and Kleinmann Citation2020).

Employee satisfaction is commonly referred to as the pleasant or positive emotional state employees feel when their work and workplace expectations are fulfilled (Locke Citation1976; Kalleberg Citation1977; Weiss and Cropanzano Citation1996; Weiss Citation2002). Such positive emotional state can be brought about by various different work and workplace elements, such as the job itself, salary, leadership, supervisors, relationships with colleagues, development opportunities, working conditions, and work environment.

Our study was focused on two aspects of employee satisfaction: supervisor and job satisfaction. The former aspect refers to the positive emotional state employees feel as a result of the fulfillment of their expectations by their supervisors. Job satisfaction is defined as “a pleasurable or positive emotional state resulting from the appraisal of one’s job or job experiences” (Locke Citation1976, 1300). We were interested in these two constructs for two main reasons. First, both supervisor and job satisfaction can be directly influenced by leadership behaviors, which constitute the daily experience of employees’ working lives (Lord and Brown Citation2001; Henderson et al. Citation2008; Marstand, Martin, and Epitropaki Citation2017; Yukl Citation2019). Second, job satisfaction is one of the most common outcome variables tested in leadership research (see e.g., Cogliser et al. Citation2009; Zhang, Wang, and Shi Citation2012; Braun et al. Citation2013; Ozturk, Karatepe, and Okumus Citation2021); our inclusion of this construct thus extends the longstanding literature stream that studies the association between leadership and subordinate satisfaction and provides further insights into how the fit between expected and observed leadership behaviors is related to job satisfaction in cross-cultural settings.

The person–supervisor fit

The person–supervisor (PS) fit is one of the five core types of person–environment (PE) fit—the other four being person–organization (PO), person–job (PJ), person–vocation (PV), and person–group (PG) fit. The PE fit concept is based on the notion that people exhibit varying degrees of compatibility with different jobs, supervisors, organization, vocations, etc., and that individuals and their work environments are compatible when their respective characteristics are well-matched (Kristof‐Brown, Zimmerman, and Johnson Citation2005; Edwards and Billsberry Citation2010). It is generally postulated that a good fit or match between individuals and the different aspects of their work environments (e.g., jobs, supervisors, and/or organizations) can lead to positive work and/or employee outcomes; whereas a low degree of fit has a negative effect on employee outcomes. PS fit is concerned with the compatibility between employees and their supervisors (Kristof‐Brown, Zimmerman, and Johnson Citation2005), the most common aspects of which examined in the extant literature are values, goals, and personalities.

Among the five types of PE fit featured in the literature, the PO and PJ fits have been widely examined by researchers; conversely, limited attention has been paid to the PS fit. For example, the extant research has examined how the PO and PJ fits are associated with various work and employee outcomes, such as job satisfaction (e.g., Chen, Sparrow, and Cooper Citation2016; Prysmakova Citation2021), organizational commitment (e.g., Astakhova Citation2016; Naz et al. Citation2020), job performance (e.g., Hoffman and Woehr Citation2006; Choi, Noe, and Cho Citation2020), organizational citizenship behaviors (e.g., Farzaneh et al. Citation2014; Zhao et al. Citation2021) and employee turnover (e.g., Boon and Biron Citation2016; Saleem et al. Citation2021). The number of studies that have examined the PS fit is relatively small compared to that of the studies focused on PO and PJ types of fit (Lambert et al. Citation2012; Marstand, Martin, and Epitropaki Citation2017; Guay et al. Citation2019). Most of the few studies on PS fit have focused on fit in relation to values, personalities, and goals (see e.g., Marstand, Martin, and Epitropaki Citation2017; Guay et al. Citation2019), while only a very small number has examined the fit between the leadership behaviors expected by subordinates and those demonstrated by their supervisors (Lambert et al. Citation2012). Research on PS fit in leadership behavior is thus needed in order to offer meaningful incremental ground for employee outcomes along with the other PE fit dimensions (Oh et al. Citation2014).

Our study examined the fit between expected and observed leadership behaviors and its effect on supervisor and job satisfaction. Based on the PE fit argument—i.e., that a good fit or match between individuals and different aspects of their work environments can lead to positive employee outcomes—we contended that the fit between expected and observed leadership behaviors is a key determinant of the extent to which employees are satisfied with their supervisors and their jobs and that a high degree of fit between the leadership behaviors expected by subordinates and those demonstrated by their supervisors is likely to lead to high degrees of supervisor and job satisfaction. The reason for such contention is that working with a supervisor who represents and is compatible with the traits and skills a subordinate expects in relation to a leadership position can lead to the fulfillment of a desired state (Byza et al. Citation2019; Guay et al. Citation2019; Biermeier-Hanson et al. Citation2020) and thus will elicit feelings of satisfaction with both the supervisor and the job. Implicit leadership theories, which are reviewed in the next section, provided further support for our arguments.

Leader-follower congruence and implicit leadership theories

Research on leader-follower congruence, an important line of research in the field of leadership, is mainly based on Implicit Leadership Theory (ILT), which contends that individuals hold sets of beliefs—or implicit expectations and assumptions—in regard to the traits, characteristics, skills, and behaviors that constitute either effective or ineffective leadership, and that these assumptions affect and guide individual attitudes and responses to leaders (Lord, Foti, and Phillips Citation1982, Lord, De Vader, and Alliger Citation1986; Herd and Lowe Citation2020). ILT suggests that a good match between the followers’ implicit expectations and their leaders’ characteristics can lead to high levels of subordinate satisfaction and performance; by contrast, any discrepancies can lower such levels.

Evolved from ILT, Culturally Endorsed Implicit Theories of Leadership (referred to as CLTs in House et al. Citation2004) go a step further and extend it to cross-cultural contexts. House and his colleagues proposed that beliefs about leadership are shared among individuals from the same cultural background and that expectations pertaining to the best way to lead vary by culture (see, e.g., House et al. Citation2004; Javidan et al. Citation2006; Herd and Lowe Citation2020). For instance, the leadership styles expected and predominantly exercised in China are authoritarian and paternalistic (Walder Citation1988; Bond Citation1996; Li and Sun Citation2015), while those expected in the UK and USA are participative and charismatic/value-based (House et al. Citation2004; Northouse Citation2018). It has been asserted that those expatriate leaders who behave in ways that conform to their followers’ cultural expectations are more likely to be accepted, while those who deviate from such expectations may not, thus resulting in diminished respect and weakened effectiveness (House et al. Citation2004; Yukl Citation2019).

A good volume of research has been conducted on leader-follower congruence; however, similar to those on the PS fit, most studies in this field have examined how leader-follower congruence in terms of values (e.g., ethical values and/or social responsibility), goals (e.g., manager-employee goals), and personalities (e.g., proactive personalities) affects various outcome variables (see, e.g., Brown and Treviño Citation2009; Zhang, Wang, and Shi Citation2012; Lee et al. Citation2017; Audenaert et al. Citation2018; Xu et al. Citation2019; Qin et al. Citation2021). Only a small number of empirical studies has examined congruence in leadership behaviors and found that the greater the agreement between the expected and observed leadership behaviors, the higher the employee outcomes in terms of—among other aspects—performance, commitment, and job satisfaction (see, e.g., Epitropaki and Martin Citation2005; Subramaniam, Othman, and Sambasivan Citation2010; Lambert et al. Citation2012; Hernaus, Černe, and Vujčić Citation2022). However, the effects found in the extant research on congruence in leadership behaviors have been mainly drawn from research conducted in mono-cultural settings; limited studies have examined such relationship in cross-cultural ones.

Empirical research has shown that the expectations and attitudes held by HCNs toward expatriate managers differ from those they have toward local ones, and are influenced by factors, such as the HCNs’ ethnocentric attitudes and the extent to which the expatriates respect local customs and are fluent in the local language (Templer Citation2010; Varma, Budhwar, and Pichler Citation2011; Ciuk and Schedlitzki Citation2022). As such, HCNs may have different expectations of and reactions to the leadership behaviors of their expatriate supervisors, and the effect of the fit between expected and observed leadership behaviors on employee attitudes in the expatiate manager-HCNs dyad may differ from that in the local manager-local employee one. The question this raises is: how is any (in)congruence in the expatiate leadership behaviors expected and observed by HCNs associated with their work-related attitudes?

To summarize, although ILT and CLTs underscore the importance of matching leadership behaviors with follower expectations, empirically, leader-follower congruence research has largely focused on examining value, goal, and personality congruence, and very few studies have investigated the fit between expected and observed leadership behaviors, particularly in cross-cultural settings. Overall, the extant empirical research provides little information on how the fit between the leadership behaviors expected by host country employees and those demonstrated by their expatriate managers related to the former’s work outcomes. This is an unfortunate gap because, although it has been shown that both leader behaviors and effectiveness are influenced by employee expectations (see, e.g., Hofstede Citation2001; Dorfman et al. Citation2012; House et al. Citation2013; Kaluza et al. Citation2021), there still is a lack of empirical evidence from cross-cultural research. Moreover, although the business world is increasingly becoming globalized—with large numbers of managers being assigned to and working in unfamiliar cultural settings—very little is known about whether HCN satisfaction is associated with the fit between the leadership behaviors they expect and those actually demonstrated by their expatriate supervisors. It is thus important to explore whether the fit between the leadership behaviors demonstrated by expatiate managers and those expected by HCNs affects the latter’s work-related attitudes. The findings of such an exploration should offer incremental insights for leader-follower congruence research and provide important understanding of the dynamics of cross-cultural leader-follower interactions.

The fit between expected and observed leadership behaviors and employee satisfaction

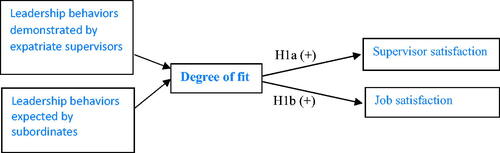

Drawing on the theoretical reasoning of ILT and CLTs and on the empirical evidence presented in the previous section, we postulated that there is a positive correlation between host country employee satisfaction and the fit between the leadership behaviors they expect and the ones they observe. In other words, we proposed that the level of satisfaction experienced by host country employees in regard to their supervisors and their jobs will be high when there is a high degree of fit between the leadership behaviors they expect and those demonstrated by their expatriate supervisors/managers. How managers behave when fulfilling their duties can significantly influence the degree of satisfaction employees feel toward their managers and their jobs (Lord and Brown Citation2001; Henderson et al. Citation2008; Marstand, Martin, and Epitropaki Citation2017; Yukl Citation2019); this is because managers’ duties include various tasks (e.g., allocating resources, setting work targets, conducting performance appraisals, and authorizing raises and benefits) that can directly affect their employees’ daily work experience. Host country employees are likely to be satisfied when the leadership behaviors demonstrated by their expatriate supervisors match their expectations. On the other hand, when the leadership behaviors demonstrated to fail to do so, they are likely to become dissatisfied. We thus expected the satisfaction felt by Chinese employees with their expatriate supervisors and their jobs to be positively related to the degree of fit between expected and observed leadership behaviors. The hypotheses are presented below and the hypothesized relationships are depicted in .

Figure 1. Hypothesized relationships between employee satisfaction and the fit between expected and observed leadership behaviors.

Hypothesis 1a. The satisfaction felt by Chinese employees toward their expatriate supervisors is positively correlated with the fit between the leadership behaviors the former expect and those the latter demonstrate.

Hypothesis 1b. The job satisfaction felt by Chinese employees is positively correlated with the fit between the leadership behaviors they expect and those demonstrated by their expatriate supervisors.

The fit between expected and observed leadership behaviors can be aligned at either a high or a low level. For example, an employee who expects and observes high degrees of task-oriented leadership behaviors would experience fit, as would an employee who expects and observes low degrees of task-oriented leadership behaviors. We expect the such fit to have stronger effects on employee satisfaction when the expected and observed leadership behaviors are aligned at a high level, rather than at a low one. This expectation is based on the conception of metafit, which Edwards and Rothbard (Citation1999) used to explain how higher levels of supplies–values (S–V) fit can help produce supplies that carry high psychological valence for people. Edwards and Rothbard (Citation1999) conducted a survey of 1,758 employees and found that their wellbeing was higher when their experiences of and values for job autotomy were both high than when they both were low.

Based on the concept of metafit, we propose that employee satisfaction is likely to be higher when the alignment of expected and observed leadership behaviors is at a high level (i.e., when employees expect their leaders to demonstrate high levels of task- and relations-oriented leadership behaviors, and such leaders’ observed behaviors are actually in line with those expectations). This is because high task- and relations-oriented leaders are more likely to get things done and to look after the well-being of their employees. In contrast, when such alignment is at a low level (i.e., when employees expect their leaders to demonstrate low levels of task- and relations-oriented leadership behaviors, and their leaders’ observed behaviors meet those expectations), employee satisfaction is likely to be lower because a low task- and relations-oriented leader does not aim at completing tasks or at providing care and support to his/her subordinates.

Furthermore, the findings of previous research show that most Chinese employees expect their leaders to exhibit strong authoritarian and paternalistic leadership styles (see, e.g., Bond Citation1996; Farh and Cheng Citation2000; Li and Sun Citation2015; Lau, Li, and Okpara Citation2020; Huang et al. Citation2023). In other words, for Chinese employees, the ideal leaders are those who, on the one hand, show strong authority and demand that their subordinates effectively complete their tasks while, on the other hand, providing them with care, support, and protection. These two leadership styles have been found to resemble task- and relations-oriented leadership behaviors; the two categories most commonly examined in leadership research (Tsui et al. Citation2004).

Based on the concepts and empirical findings discussed above, we expected the level of satisfaction felt by Chinese employees toward their expatriate supervisors and their jobs in the presence of a high-high alignment (i.e., with employees both expecting and observing high task- and relations-oriented leadership behaviors) to be higher than that elicited by a low-low one (i.e., with employees both expecting and observing low task- and relations-oriented leadership behaviors). Thus, we proposed:

Hypothesis 2a. Chinese employee satisfaction with their expatriate supervisors is higher when the fit between expected and observed leadership behaviors is aligned at a high level than when it is aligned at a low one.

Hypothesis 2b. Chinese employee job satisfaction is higher when the fit between expected and observed leadership behaviors is aligned at a high level than when it is aligned at a low one.

Methods

Sample and research procedure

The data used in our study were collected from 237 Chinese employees (i.e., the followers) who reported directly to 40 expatriate senior managers (i.e., the leaders), with a mean of 5.9 subordinates per leader (range: 3–17). Our sample expatriates worked in a variety of organizations and industries in China and were contacted through LinkedIn, an online professional social network. We included only those in senior job positions (i.e., with job titles, such as CEO, CFO, chairman, managing director, president, and general manager), as these are commonly regarded as leaders and we thus expected them to supervise some Chinese subordinates. We explained the objectives of our research project to the sample expatriates, and we then asked them to email a link to our study’s survey questionnaire to all their directly reporting Chinese subordinates.

Our survey questionnaire was part of a larger research project and was administered through Qualtrics, an online survey platform. Among others, it included questions related to demographics (age, gender, and years of education and tenure) and to the Chinese followers’ views of their expatriate leaders’ current leadership behaviors, the leadership behaviors they expected, and their degree of satisfaction with their jobs and their expatriate supervisors. The research project was introduced and the confidentiality of the information and the voluntary nature of the employees’ participation were assured on the introduction page of the questionnaire. The Chinese subordinates’ respective leader’s names were shown on both the introductory and the second pages so that they would be clearly informed about who they were being asked to assess. The questionnaire was formulated in English, as the Chinese subordinates reported directly to the expatriate leaders and were thus expected to have a good understanding of the language.

presents the statistical profile of our research’s sample: 54.4% of our participants were female, nearly four-fifths (79.3%) were aged between 20 and 39, around 86% held a university degree or higher, and over half (56.1%) had worked in their respective organizations for more than two years.

Table 1. Demographics of the respondents.

Due to the aim of this research (i.e., an examination of the effect on employee satisfaction of the fit between expected and observed leadership behaviors), we followed Lambert et al. (Citation2012) study and asked employees to provide subjective assessments of leadership behaviors and their satisfaction. This was in line with the notion that individuals respond to fit or misfit based on their subjective views and experiences (French, Caplan, and Harrison Citation1982, cited in Lambert et al. Citation2012). To minimize the potential common method variance effects, we used the procedural remedies related to questionnaire and item design recommended by Podsakoff et al. (Citation2003). Specifically, to reduce potential method biases, we used a temporal separation method: we placed the measurements of the dependent and independent variables on different questionnaire pages to create a time lag and to reduce the respondents’ ability and/or motivation to use previous answers to subsequent questions. In addition, we tried to eliminate any item ambiguity, demand characteristics, and social desirability by ensuring that the question items were clear and contained no hidden cues. The result of Harman’s single factor test showed that the total variance explained by a single factor was 28.9%—lower than the 50% threshold—thus indicating that a low likelihood of any substantial common method bias.

Measures

Leadership behaviors

We measured two categories of leadership behaviors: task-oriented (four items) and relations-oriented (five items). The question items were derived from Yukl, Gordon, and Taber (Citation2002). The sample Chinese subordinates were asked to answer the nine question items twice—once to indicate the extent to which their leaders were currently adopting each behavior (observed) and again to indicate the extent to which they felt their leaders should have been adopting each behavior (expected)—on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = to an extremely small extent; 7 = to an extremely large extent). We collected the data of the observed leadership behaviors from subordinates, rather than from third parties because the subordinates’ subjective opinions about the behaviors of their leaders are constructed from what they have seen or felt, which is more likely to affect their attitudes and behaviors than observations made by third parties. A sample item for task-oriented behaviors was “Clarify what results are expected for a task”; and a sample item for relations-oriented behaviors was “Consult with people on decisions affecting them.” The Cronbach alpha (α) values for the observed behaviors (task-oriented and relations-oriented) were found to be 0.90 and 0.93, respectively; and those for the expected behaviors were both found to be 0.97.

Employee satisfaction

We measured two outcome variables: subordinate satisfaction with expatriate supervisor (supervisor satisfaction) and job satisfaction.

Satisfaction with expatriate supervisor (supervisor satisfaction). To measure our sample Chinese employees’ satisfaction with their expatriate supervisors, we adapted Hackman and Oldham (Citation1980) three-item scale. We used a 7-point Likert scale (1 = very dissatisfied; 7 = very satisfied). Example items were “The amount of support and guidance I receive from him/her” and “The overall quality of the supervision I receive from him/her.” The α value was found to be 0.89.

Job satisfaction. To measure the sample employees’ overall job satisfaction, we used Hackman and Lawler (Citation1971) scale (three items). Example items were “I am very satisfied with the kind of work I have to do on my job” and “Generally speaking, I am very satisfied with my job.” We measured this variable on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) (α = 0.86).

Controls

Prior research suggests a correlation between demographic characteristics and employee satisfaction (see, e.g., Lee and Wilbur Citation1985; Clark Citation1997; Audenaert et al. Citation2018). Therefore, in our analyses, we controlled for our sample employees’ genders, ages, educational levels, and organizational tenures. Gender was measured as a dichotomous variable. Age was measured using nine ranges (1 = 20–24; 2 = 25–29; 3 = 30–34; 4 = 35–39; 5 = 40–44; 6 = 45–49; 7 = 50–54; 8 = 55–59; 9 = 60 and above). Tenure was measured using five ranges (1 = <1 year; 2 = between 1 and 2 years; 3 = between 2 and 5 years; 4 = between 5 and 10 years; 5 = 10 years or more).

Analysis

To test our hypotheses, we performed polynomial regression analyses and response surface modeling (Edwards and Parry Citation1993; Edwards and Harrison Citation1993; Edwards Citation1994). Edwards and his colleagues advocated for the use of polynomial regressions and three-dimensional response surfaces to examine the effects of (in)congruence on outcome variables. They stated that the use of polynomial regressions can enable the avoidance of numerous methodological issues associated with the difference scores method (e.g., confounded effects and difficulties in distinguishing the independent effect of each component measure) and is more accurate in assessing how outcome variables are affected by the congruence or incongruence between component measures. The shape and direction of a response surface along the (in)congruence line help to interpret the coefficients drawn from the results of polynomial regression analyses.

We regressed the outcome variables—satisfaction with expatriate supervisor and job satisfaction—on the control variables and on the five polynomial terms for task- and relations-oriented leadership behaviors. For task-oriented leadership behaviors, these five polynomial terms were: observed task-oriented leadership behaviors (OT), expected task-oriented leadership behaviors (ET), observed task-oriented leadership behaviors squared (OT2), observed task-oriented leadership behaviors multiplied by expected task-oriented leadership behaviors (OT × ET), and expected task-oriented leadership behaviors squared (ET2). A similar set of five polynomial terms (OR, ER, OR2, OR × ER, ER2) were computed for relations-oriented leadership behaviors. The polynomial (quadratic) regression equations used were:

Y1 (Satisfaction with expatriate supervisor) = b0 + b1OT + b2ET + b3OT2 + b4OT × ET + b5ET2

Y2 (Satisfaction with expatriate supervisor) = b0 + b1OR + b2ER + b3OR2 + b4OR × ER + b5ER2

Y3 (Job satisfaction) = b0 + b1OT + b2ET + b3OT2 + b4OT × ET + b5ET2

Y4 (Job satisfaction) = b0 + b1OR + b2ER + b3OR2 + b4OR × ER + b5ER2

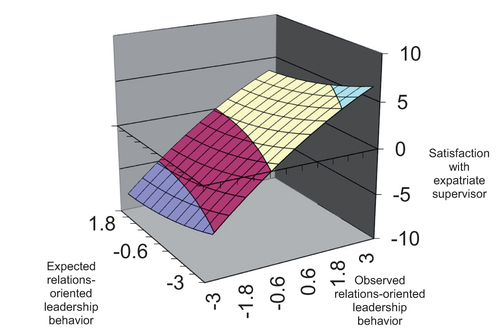

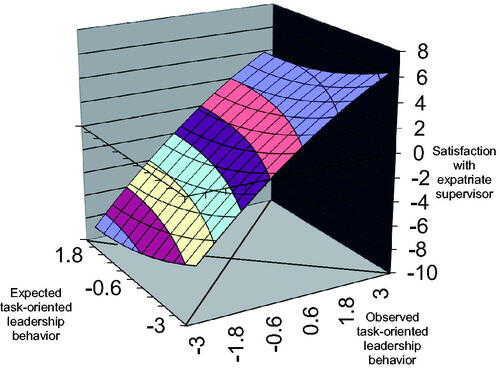

Figure 2. Response surface for the relationship among expected and observed ask-oriented leadership behavior and satisfaction with expatriate supervisor.

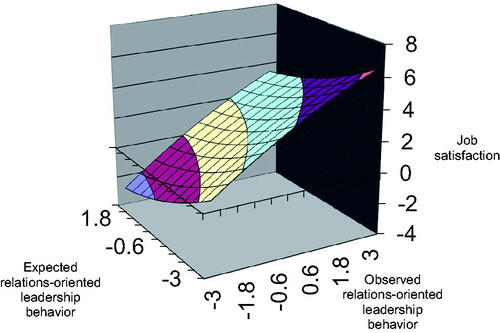

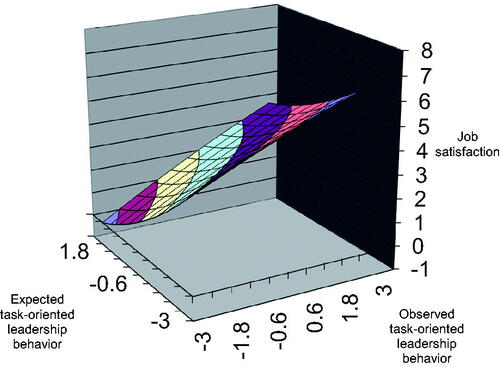

Figure 3. Response surface for the relationship among expected and observed task-oriented leadership behavior and job satisfaction.

Results

presents the means, standard deviations, correlations, and reliability coefficients of the variables. The control variables (age, gender, educational level, and tenure) were found to not be significantly correlated with the dependent ones. Seven out of the eight correlations between the independent variables (expected and observed leadership behaviors) and the dependent variables were found to be significant, with r ranging from 0.13 to 0.80.

Table 2. Means, standard deviations, correlations, and scale reliabilities.

reports the unstandardized coefficients of the control variables and of the five polynomial terms for expected and observed task-oriented leadership behaviors. The slope and curvatures along the congruence and incongruence lines are also reported. presents the unstandardized coefficients and the slopes and curvatures for expected and observed relations-oriented leadership behaviors. illustrate the three-dimensional response surfaces, in which the expected and observed leadership behavior scores are located on the X, Y planes, or the “floor” of the figures. Supervisor satisfaction and job satisfaction are located on the Z-axes, which are the vertical ones extending from the floor of the graph. The lines of congruence, where Y = X, are the lines that run from the front corner to the back corner of the floor. The lines of incongruence, where Y = −X, are the lines that run from the left corner to the right corner of the floor.

Table 3. Polynomial regressions of employee satisfaction on observed-expected task-oriented leadership behavior congruence/incongruence.

Table 4. Polynomial regressions of employee satisfaction on observed-expected relations-oriented leadership behavior congruence/incongruence.

Hypothesis 1a proposed that supervisor satisfaction would be positively correlated with the fit between expected and observed leadership behaviors, and hypothesis 1b postulated that job satisfaction would also be positively correlated with the such fit. To test hypotheses 1a and 1b, we examined the F values of the three second-order polynomial terms, the curvatures along the congruence lines, and the correspondent response surfaces (Kristof‐Brown, Zimmerman, and Johnson Citation2005; Shanock et al. Citation2010). As shown in , both of the F values were found to be jointly significant (F = 33.86, p < 0.001; F = 10.79, p < 0.001). For supervisor satisfaction, the curvature along the congruence line was found to be not significant and the slope of the surface along the congruence line was found to be positive and significant (curvature = −0.01, p > 0.05; slope = 1.54, p < 0.01). For job satisfaction, both the curvature and the slope of the surface along the congruence line were found to be not significant (curvature = 0.07, p > 0.05; slope = −0.09, p > 0.05). These results indicate that supervisor satisfaction is positively correlated with the fit between expected and observed task-oriented leadership behaviors.

also shows that the three second-order polynomial terms were found to be jointly significant (F = 49.86, p < 0.001; F = 13.55, p < 0.001). For supervisor satisfaction, the curvature along the congruence line was found to be not significant and the slope of the surface along the congruence line was found to be positive and significant (curvature = −0.05, p > 0.05; slope = 1.45, p < 0.001). For job satisfaction, both the curvature and the slope of the surface along the congruence line were found to be not significant (curvature = 0.02, p > 0.05; slope = 0.46, p > 0.05). These results indicate that supervisor satisfaction is positively correlated with the fit between the expected and observed relations-oriented leadership behaviors. In line with the above results, the surface plots in and show that the response surfaces have a positive slope along the congruence lines between expected and observed leadership behaviors. The above results provide support for H1a, but not for H1b.

Hypothesis 2a proposed that Chinese employee satisfaction with expatriate supervisors will be higher when the expected and observed leadership behaviors are aligned at a high level. Hypothesis 2b proposed that Chinese employee job satisfaction will be higher when the fit between expected and observed leadership behaviors is aligned at a high level. To test these hypotheses, we examined the slopes along the congruence lines as well as the response surfaces. For supervisor satisfaction, as shown in and , the slopes along the congruence lines were found to be positive and significant (1.54, p < 0.01 for task-oriented behaviors; 1.45, p < 0.001 for relations-oriented behaviors), indicating that a high-high congruence results in higher supervisor satisfaction than a low-low congruence. The response surfaces shown in and indicate that supervisor satisfaction is higher in the back corner (high/high congruence) than in the front (low/low congruence). The results thus support H2a. For job satisfaction, as can be seen from and , the slope along the congruence line was found to be negative and not significant (−0.09) for task-oriented behaviors, and positive but not significant (0.46) for relations-oriented ones. The results do not support H2b.

Taken together, the results presented above provide support for hypotheses 1a and 2a, but not for hypotheses 1b and 2b. To summarize, our results show that (1) Chinese employee satisfaction with expatriate supervisors is high when there is a high degree of fit between the expected and observed leadership behaviors (H1a) and (2) satisfaction with expatriate supervisors is higher when the expected and observed leadership behaviors are aligned at a high level (H2a).

Discussion

Our study addressed gaps in the PE fit and the leader-follower congruence research and represents one of the first attempts to examine how the fit between expected and observed leadership behaviors is correlated with employee outcomes in a cross-cultural setting. Our results show that Chinese employee satisfaction with expatriate supervisors is high when the degree of fit between expected and observed leadership behaviors is high (H1a) and that such satisfaction is higher when the expected and observed leadership behaviors are aligned at a high level (H2a). The results provide empirical support for the implicit leadership theories assertion that a good match between expected and observed leadership behaviors can lead to higher degrees of employee satisfaction.

We did not find a significant association between job satisfaction and the fit in leadership behavior (H1b). As was argued by Kristof‐Brown, Zimmerman, and Johnson (Citation2005), this may be because job satisfaction should be most strongly associated with the person-job fit rather than with constructs indirectly related to jobs, such as the person-supervisor fit, as hypothesized in our study. It also may be due to the fact that many Chinese employees do not regard job satisfaction as a valuable or meaningful aspect of their working lives, and therefore factors, such as leadership behaviors would have a limited influence on it. Using data drawn from the 2015 International Social Survey Program (ISSP) and analyzing a sample of 17,938 individuals in 36 countries and regions, Zhang et al. (Citation2019) found that the top work attributes valued by Chinese employees are high income, promotion opportunities, and job security; while they rank job satisfaction significantly lower than their counterparts in other countries. If job satisfaction is not something employees care about or value, then organizational factors, such as leadership behaviors would have little or no influence on it. Further research conducted in pursuit of this line of inquiry would help to explain how the work attributes valued by Chinese employees may influence the association between leader-follower congruence and job satisfaction. Below, we discuss the theoretical contributions of our study.

Theoretical contributions

Our study contributes to the PE fit and leadership literatures in three ways. Firstly, it extends the scope of the existing person-supervisor (PS) fit research to include the fit in leadership behaviors. Although previous research had found that any fits or similarities between supervisors and subordinates in values, goals, and personalities are significantly related to positive employee outcomes (see the meta-analysis performed by Kristof‐Brown, Zimmerman, and Johnson Citation2005), little was hitherto known about how the fit between expected and observed leadership behaviors affects employee satisfaction. Our study examined the such relationship and found it to be positively correlated with supervisor satisfaction, thus shedding some light on the relationship between the fit in leadership behaviors and employee work outcomes.

Second, our study fills a gap in the leader-follower congruence research by examining fit in leadership behaviors in a cross-cultural setting and provides valuable empirical support for implicit leadership theories. Within the leader-follower congruence literature, research on value and personality similarities is the most notable (see, e.g., Jordan et al. Citation2013; Audenaert et al. Citation2018; Xu et al. Citation2019; Qin et al. Citation2021); there is however a dearth of studies on the fit between expected and observed leadership behaviors, particularly in cross-cultural contexts. Implicit leadership theories contend that a match between expected and observed leadership behaviors should influence employee satisfaction as individuals are likely to feel satisfied when working with supervisors who exhibit the traits and skills they expect from people in leadership positions (Lord, Foti, and Phillips Citation1982; Lord and Brown Citation2001; Henderson et al. Citation2008; Marstand, Martin, and Epitropaki Citation2017; Yukl Citation2019). This match has also been argued to be important in cross-cultural leader-follower dyads (Hofstede Citation2001; House et al. Citation2004; Bird Citation2018); however; few cross-cultural studies have been conducted to provide support for the theoretical assertion. By using data collected from a cross-cultural situation to investigate the effect of fit between expected and observed leadership behaviors on employee satisfaction, our study extends the previous research to a cross-cultural setting and provides empirical support for implicit leadership theories.

Third, this study contributes to the leader-follower congruence literature by examining how, at varying levels, fit is related to employee outcomes. Expected and observed leadership behaviors can be congruent at varying levels, which, in turn, can have varying effects on employee outcomes. Our study examined how the effects of fit at two different levels—high and low—are associated with employee satisfaction. Our results show that behavioral alignment at a high level is associated with a higher supervisor satisfaction. The finding is consistent with Edwards and Rothbard’s (Citation1999) notion of metafit, which describes how higher levels of a fit can help produce supplies for high psychological valence. Our analysis and findings provide insights into different patterns of the effects of leader-follower fit/congruence on employee outcomes.

Practical implications

Our results provide two main practical implications for expatriate business leaders and MNCs. First, our study provides insights into the leadership behaviors expected by Chinese employees and how they are related to their satisfaction. Our results show that Chinese employees expect their supervisors to demonstrate both task- and relations-oriented leadership behaviors at a rather high level (means = 5.50 and 5.53, respectively). The results also show that Chinese employee satisfaction with expatriate supervisors is high when the latter’s task- and relations-oriented leadership behaviors match their expectations. Thus, those expatriate managers who are currently or will be working in China are suggested to demonstrate high levels of task- and relations-oriented leadership behaviors when leading Chinese employees. In other words, when carrying out their leadership roles, expatriate managers would be advised, on the one hand, to exert power over their Chinese subordinates and demand that they efficiently improve or accomplish their tasks; and, on the other hand, to provide their Chinese subordinates with the care, support, and protection suited to establish trust, cooperation, and employee satisfaction.

Second, our finding in regard to the positive effect of the fit between expected and observed leadership behaviors on Chinese employees’ satisfaction with their expatriate supervisors has important implications for MNC training and development programs. We suggest that leadership training and development programs aimed at expatriate managers focus on increasing their understanding of the expectations of local employees and on preparing such managers to behave in ways that match their host country employees’ expectations. This could be achieved by surveying local employees’ expectations for leadership behaviors and providing managers with opportunities to work in cross-cultural teams and with experienced expatriates. Expatriate managers could also be invited to participate in role play exercises that demonstrate how different levels of fit between expected and observed leadership behaviors affect employees’ work-related attitudes and their associated benefits and drawbacks. In addition to providing training for leaders, we recommend that host country employees be provided training programs on the issues related to working with expatriate supervisors. Such programs, which are not commonly provided by MNCs, would help employees understand what to expect of their expatriate supervisors and how to work with them. The provision of training aimed at shaping the expectations held by both leaders and followers would make both more likely to accept each other and work together effectively. This would help MNCs address any potential discrepancies in role expectations and thus enhance leader effectiveness and positive employee outcomes.

Limitations of the study and opportunities for future research

Despite its contributions, our study is not without limitations; these provide opportunities for future research. One such limitation stems from the fact that it was conducted in the single cross-cultural setting in China, which makes it difficult to generalize its findings to other cross-cultural contexts. The unique Chinese cultural characteristics—such as a high-power distance and deference to authority—may lead Chinese employees to provide unduly favorable evaluations of their supervisors’ leadership behaviors, which may result in inflating the effects of congruence. Future studies could validate our findings in different cross-cultural settings.

Another limitation is related to the modest size of our sample. Our analysis was based on data collected from 237 Chinese employees who reported directly to 40 expatriate senior managers. Although this sample size is acceptable for performing statistical analysis and is unlikely to have seriously undermined our findings, we still acknowledge it as a limitation.

An area of organizational research that could benefit from taking into account leadership behavior congruence issues is that of expatriate adjustment, which has hitherto largely focused on exploring the effects of a range of antecedent variables on the degree to which expatriate managers adjust to their host countries in three dimensions—general, social interaction, and work/role adjustment (see, e.g., Black and Stephens Citation1989; Peltokorpi and Froese Citation2012; Ravasi, Salamin, and Davoine Citation2015; Okpara, Kabongo, and Lau Citation2021). Although the work/role adjustment dimension has been examined in this line of research, little information has hitherto been provided for leadership behavior adjustment (Tsai et al. Citation2019). Future research may theorize on and investigate how and the degree to which expatriate managers adjust their leadership behaviors to match the expectations of host country employees, and how such adjustments are associated with various employee outcomes.

Conclusions

In our study, by drawing upon the person-supervisor fit and the leader-follower congruence literature, we examined an important, yet relatively unexplored, aspect of leader-follower congruence—that between expected and observed leadership behaviors—and its effect on employee satisfaction in a cross-cultural context. Our findings reveal that the fit between expected and observed leadership behaviors is an important factor associated with supervisor satisfaction. Given that cross-border and cross-cultural business operations are becoming increasingly common, researchers could conduct similar research in other cross-cultural settings to extend our understanding of the congruence effect. We hope that our study will be a catalyst for more research aimed at uncovering further insights into this important field.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Chin-Ju Tsai

Dr. Chin-Ju Tsai is Senior Lecturer of Human Resource Management at Royal Holloway, University of London, U.K. Her research interests include cross-cultural leadership, HRM and organisational performance, and HRM in SMEs. Her work has appeared in top journals including Human Relations, Human Resource Management Journal, The International Journal of Human Resource Management, International Small Business Journal, Organization, and Work and Occupations.

Kun Qiao

Dr. Kun Qiao is Associate Professor in Management at Dalian University of Technology, China. She has published paper in top journals including Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources and The International Journal of Human Resource Management.

References

- Argyris, C., and C. Argyris. 1976. Increasing Leadership Effectiveness. New York, NY: Wiley.

- Astakhova, M. N. 2016. “Explaining the Effects of Perceived Person-Supervisor Fit and Person-Organization Fit on Organizational Commitment in the US and Japan.” Journal of Business Research 69 (2):956–63.

- Audenaert, M., P. Carette, L. M. Shore, T. Lange, T. Van Waeyenberg, and A. Decramer. 2018. “Leader-Employee Congruence of Expected Contributions in the Employee-Organization Relationship.” The Leadership Quarterly 29 (3):414–22.

- Biermeier-Hanson, B., K. T. Wynne, G. Thrasher, and J. B. Lyons. 2020. “Modeling the Joint Effect of Leader and Follower Authenticity on Work and Non-Work Outcomes.” The Journal of Psychology 155 (2):140–64.

- Bird, A. 2018. “Mapping the Content Domain of Global Leadership Competencies.” In Global Leadership: Research, Practice, and Development, edited by M. E. Mendenhall, J. S. Osland, A. Bird, G. R. Oddou, M. J. Stevens, M. L. Maznevski, and G. K. Stahl, 119–42. New York: Routledge.

- Black, J. S., and G. K. Stephens. 1989. “The Influence of the Spouse on American Expatriate Adjustment and Intent to Stay in Pacific Rim Overseas Assignments.” Journal of Management 15 (4):529–44.

- Byza, O. A., S. L. Dörr, S. C. Schuh, and G. W. Maier. 2019. “When Leaders and Followers Match: The Impact of Objective Value Congruence, Value Extremity, and Empowerment on Employee Commitment and Job Satisfaction.” Journal of Business Ethics 158 (4):1097–112.

- Bond, M. H. 1996. “Chinese Values.” In M. H. Bond (Ed.), The Handbook of Chinese Psychology, 208–26. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press.

- Boon, C., and M. Biron. 2016. “Temporal Issues in Person–Organization Fit, Person–Job Fit and Turnover: The Role of Leader–Member Exchange.” Human Relations 69 (12):2177–200. doi:10.1177/0018726716636945.

- Braun, S., C. Peus, S. Weisweiler, and D. Frey. 2013. “Transformational Leadership, Job Satisfaction, and Team Performance: A Multilevel Mediation Model of Trust.” The Leadership Quarterly 24 (1):270–83.

- Brown, M. E., and L. K. Treviño. 2009. “Leader–Follower Values Congruence: Are Socialized Charismatic Leaders Better Able to Achieve It?” The Journal of Applied Psychology 94 (2):478–90. doi:10.1037/a0014069.

- Bushra, F., U. Ahmad, and A. Naveed. 2011. “Effect of Transformational Leadership on Employees’ Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment in Banking Sector of Lahore (Pakistan).” International Journal of Business and Social Science 2 (18):261–7.

- Clark, A. E. 1997. “Job Satisfaction and Gender: Why Are Women so Happy at Work?” Labour Economics 4 (4):341–72.

- Chen, P., P. Sparrow, and C. Cooper. 2016. “The Relationship between Person-Organization Fit and Job Satisfaction.” Journal of Managerial Psychology 31 (5):946–59.

- Choi, W., R. Noe, and Y. Cho. 2020. “What Is Responsible for the Psychological Capital-Job Performance Relationship? An Examination of the Role of Informal Learning and Person-Environment Fit.” Journal of Managerial Psychology 35 (1):28–41.

- Ciuk, S., and D. Schedlitzki. 2022. “Host Country Employees’ Negative Perceptions of Successive Expatriate Leadership: The Role of Leadership Transference and Implicit Leadership Theories.” Journal of Global Mobility 10 (1):80–104.

- Cogliser, C. C., C. A. Schriesheim, T. A. Scandura, and W. L. Gardner. 2009. “Balance in Leader and Follower Perceptions of Leader–Member Exchange: Relationships with Performance and Work Attitudes.” The Leadership Quarterly 20 (3):452–65.

- DeRue, D. S., J. D. Nahrgang, N. Wellman, and S. E. Humphrey. 2011. “Trait and Behavioral Theories of Leadership: An Integration and Metaanalytic Test of Their Relative Validity.” Personnel Psychology 64:7–52.

- Dinić, B. M., K. Breevaart, W. Andrews, and R. E. de Vries. 2023. “Voters’ HEXACO Personality Traits as Predictors of Their Presidential Leadership Style Preferences.” Personality and Individual Differences 202:111994.

- Dorfman, P., M. Javidan, P. Hanges, A. Dastmalchian, and R. House. 2012. “GLOBE: A Twenty Year Journey into the Intriguing World of Culture and Leadership.” Journal of World Business 47 (4):504–18.

- Edwards, J. R., and R. V. Harrison. 1993. “Job Demands and Worker Health: Three-Dimensional Reexamination of the Relationship between Person-Environment Fit and Strain.” The Journal of Applied Psychology 78 (4):628–48.

- Edwards, J. R., and M. E. Parry. 1993. “On the Use of Polynomial Regression Equations as an Alternative to Difference Scores in Organizational Research.” Academy of Management Journal 36:1577–613.

- Edwards, J. R. 1994. “The Study of Congruence in Organizational Behavior Research: Critique and a Proposed Alternative.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 58:51–100.

- Edwards, J. R., and N. P. Rothbard. 1999. “Work and Family Stress and Well-Being: An Examination of Person-Environment Fit in the Work and Family Domains.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 77 (2):85–129. doi:10.1006/obhd.1998.2813.

- Edwards, J. A., and J. Billsberry. 2010. “Testing a Multidimensional Theory of Person Environment Fit.” Journal of Managerial Issues 22 (4):476–493.

- Enright, M. J. 2016. Developing China: The Remarkable Impact of Foreign Direct Investment. London: Taylor & Francis.

- Epitropaki, O., and R. Martin. 2005. “From Ideal to Real: A Longitudinal Study of the Role of Implicit Leadership Theories on Leader-Member Exchanges and Employee Outcomes.” Journal of Applied Psychology 90 (4):659.

- Farh, J.-L, and B.-S. Cheng. 2000. “A Cultural Analysis of Paternalistic Leadership in Chinese Organizations.” In Management and Organizations in the Chinese Context, edited by J. T. Li, A. S. Tsui, and E. Weldon, 84–127. London: Macmillan.

- Farzaneh, J., Farashah, A. D., & Kazemi, M. (2014). “The impact of person-job fit and person-organization fit on OCB: The mediating and moderating effects of organizational commitment and psychological empowerment.” Personnel Review, 43 (5):672–691.

- Fleishman, E. A. 1953. “The Description of Supervisory Behavior.” Journal of Applied Psychology 37 (1):1–6.

- French, J. R. P. Jr., R. D. Caplan, and R. V. Harrison. 1982. The Mechanisms of Job Stress and Strain. New York, NY: Wiley.

- Grosse, R., J. Gamso, and R. C. Nelson. 2021. “China’s Rise, World Order, and the Implications for International Business.” Management International Review 61 (1):1–26.

- Guay, R. P., Y. J. Kim, I. S. Oh, and R. M. Vogel. 2019. “The Interaction Effects of Leader and Follower Conscientiousness on Person-Supervisor Fit Perceptions and Follower Outcomes: A Cross-Level Moderated Indirect Effects Model.” Human Performance 32 (3–4):181–99.

- Hackman, J. R., and G. R. Oldham. 1980. Work Redesign. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Hackman, J. R., and E. E. Lawler. 1971. “Employee Reactions to Job Characteristics.” Journal of Applied Psychology 55 (3):259.

- Heimann, A. L., P. V. Ingold, and M. Kleinmann. 2020. “Tell Us about Your Leadership Style: A Structured Interview Approach for Assessing Leadership Behavior Constructs.” The Leadership Quarterly 31 (4):101364.

- Henderson, D. J., S. J. Wayne, L. M. Shore, W. H. Bommer, and L. E. Tetrick. 2008. “Leader-Member Exchange, Differentiation, and Psychological Contract Fulfillment: A Multilevel Examination.” The Journal of Applied Psychology 93 (6):1208–19. doi:10.1037/a0012678.

- Herd, A., and K. Lowe. 2020. “Cross-Cultural Comparative Leadership Studies: A Critical Look to the Future.” In The SAGE Handbook of Contemporary Cross-Cultural Management, edited by B. Szkudlarek, L. Romani, D. V. Caprar, and J. S. Osland, 357–74. London and Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Hernaus, T., M. Černe, and M. T. Vujčić. 2022. “Leader–Member Innovative Work Behavior (in) Congruence and Task Performance: The Moderating Role of Work Engagement.” European Management Journal. doi:10.1016/j.emj.2022.03.008

- Hoffman, B. J., and D. J. Woehr. 2006. “A Quantitative Review of the Relationship between Person–Organization Fit and Behavioral Outcomes.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 68 (3):389–99.

- Hofstede, G. 2001. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions and Organizations across Nations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- House, R. 1971. “A Path Goal Theory of Leader Effectiveness.” Administrative Science Quarterly 16 (3):321–39.

- House, R. 1996. “Path-Goal Theory of Leadership: Lessons, Legacy, and a Reformulated Theory.” The Leadership Quarterly 7 (3):323–52.

- House, R., P. J. Hanges, M. Javidan, P. Dorfman, and V. Gupta. 2004. Culture, Leadership, and Organizations: The GLOBE Study of 62 Societies. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- House, R. J., P. W. Dorfman, M. Javidan, P. J. Hanges, and M. F. S. de Luque. 2013. Strategic Leadership across Cultures: GLOBE Study of CEO Leadership Behavior and Effectiveness in 24 Countries. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications.

- Huang, Q., K. Zhang, Y. Wang, A. A. Bodla, and D. Zhu. 2023. “When is Authoritarian Leadership Less Detrimental? The Role of Leader Capability.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20 (1):707.

- Ishaq, E., S. Bashir, and A. K. Khan. 2021. “Paradoxical Leader Behaviors: Leader Personality and Follower Outcomes.” Applied Psychology 70 (1):342–57.

- Javidan, M., P. Dorfman, M. S. De Luque, and R. House. 2006. “In the Eye of the Beholder: Cross Cultural Lessons in Leadership from Project GLOBE.” Academy of Management Perspectives 20 (1):67–90. doi:10.5465/amp.2006.19873410.

- Jordan, J., M. E. Brown, L. K. Treviño, and S. Finkelstein. 2013. “Someone to Look Up to: Executive–Follower Ethical Reasoning and Perceptions of Ethical Leadership.” Journal of Management 39 (3):660–83.

- Judge, T. A., R. F. Piccolo, and R. Ilies. 2004. “The Forgotten Ones? The Validity of Consideration and Initiating Structure in Leadership Research.” Journal of Applied Psychology 89:36–51.

- Kalleberg, A. L. 1977. “Work Values and Job Rewards: A Theory of Job Satisfaction.” American Sociological Review 42:124–43.

- Kaluza, A. J., F. Weber, R. van Dick, and N. M. Junker. 2021. “When and How Health‐Oriented Leadership Relates to Employee Well‐Being—The Role of Expectations, Self‐Care, and LMX.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology 51 (4):404–24.

- Kristof‐Brown, A. L., R. D. Zimmerman, and E. C. Johnson. 2005. “Consequences of Individual’s fit at Work: A Meta-Analysis of Person-Job, Person-Organization, Person-Group, and Person-Supervisor fit.” Personnel Psychology 58 (2):281–342.

- Lambert, L. S., B. J. Tepper, J. C. Carr, D. T. Holt, and A. J. Barelka. 2012. “Forgotten but Not Gone: An Examination of Fit between Leader Consideration and Initiating Structure Needed and Received.” Journal of Applied Psychology 97 (5):913.

- Lau, W. K., Z. Li, and J. Okpara. 2020. “An Examination of Three-Way Interactions of Paternalistic Leadership in China.” Asia Pacific Business Review 26 (1):32–49.

- Lee, D., Y. Choi, S. Youn, and J. U. Chun. 2017. “Ethical Leadership and Employee Moral Voice: The Mediating Role of Moral Efficacy and the Moderating Role of Leader–Follower Value Congruence.” Journal of Business Ethics 141 (1):47–57.

- Lee, R., and E. R. Wilbur. 1985. “Age, Education, Job Tenure, Salary, Job Characteristics, and Job Satisfaction: A Multivariate Analysis.” Human Relations 38 (8):781–91.

- Li, Y., and J.-M. Sun. 2015. “Traditional Chinese Leadership and Employee Voice Behavior: A Cross-Level Examination.” The Leadership Quarterly 26 (2):172–89.

- Locke, E. A. 1976. “The Nature and Causes of Job Satisfaction.” In Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, edited by M. D. Dunnette, 1297–349. Chicago, IL: Rand McNally.

- Lord, R. G., C. De Vader, and G. M. Alliger. 1986. “A Meta-Analysis of the Relation between Personality Traits and Leadership Perceptions: An Application of Validity Generalization Procedures.” Journal of Applied Psychology 71 (3):402–10.

- Lord, R. G., R. J. Foti, and J. S. Phillips. 1982. “A Theory of Leadership Categorization.” In J. G. Hunt, U. Sekaran, & C. A. Schriesheim (Eds.), Leadership: Beyond Establishment Views. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

- Lord, R. G., and D. J. Brown. 2001. “Leadership, Values, and Subordinate Self-Concepts.” The Leadership Quarterly 12:133–52.

- Lord, R. G., and K. J. Maher. 2002. Leadership and Information Processing: Linking Perceptions and Performance. Boston: Routledge.

- Luo, Y. 2007. “From Foreign Investors to Strategic Insiders: Shifting Parameters, Prescriptions and Paradigms for MNCs in China.” Journal of World Business 42 (1):14–34.

- Marstand, A. F., R. Martin, and O. Epitropaki. 2017. “Complementary Person-Supervisor Fit: An Investigation of Supplies-Values (SV) Fit, Leader-Member Exchange (LMX) and Work Outcomes.” The Leadership Quarterly 28 (3):418–37.

- Masterson, S. S., and M. Lensges. 2015. “Leader–Member Exchange and Justice.” In The Oxford Handbook of Leader-Member Exchange, edited by T. Bauer and B. Erdogan. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Mifsud, D. 2023. “A Systematic Review of School Distributed Leadership: Exploring Research Purposes, Concepts and Approaches in the Field between 2010 and 2022.” Journal of Educational Administration and History. doi:10.1080/00220620.2022.2158181.

- Naz, S., C. Li, Q. A. Nisar, M. A. S. Khan, N. Ahmad, and F. Anwar. 2020. “A Study in the Relationship between Supportive Work Environment and Employee Retention: Role of Organizational Commitment and Person–Organization Fit as Mediators.” Sage Open 10 (2):2158244020924694.

- Northouse, P. G. 2018. Leadership: Theory and Practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Oh, I.-S., R. P. Guay, K. Kim, C. M. Harold, J.-H. Lee, C.-G. Heo, and K.-H. Shin. 2014. “Fit Happens Globally: A Meta-Analytic Comparison of the Relationships of Person-Environment Fit Dimensions with Work Attitudes and Performance across East Asia, Europe, and North America.” Personnel Psychology 67:99–1.

- Okpara, J. O., J. D. Kabongo, and W. K. Lau. 2021. “Effects of Predeparture and Postarrival Cross‐Cultural Trainings on Expatriates Adjustment: A Study of Chinese Expatriates in Nigeria.” Thunderbird International Business Review 63 (2):115–30.

- Ozturk, A., O. M. Karatepe, and F. Okumus. 2021. “The Effect of Servant Leadership on Hotel Employees’ Behavioral Consequences: Work Engagement versus Job Satisfaction.” International Journal of Hospitality Management 97:102994.

- Podsakoff, P. M., S. B. MacKenzie, J.-Y. Lee, and N. P. Podsakoff. 2003. “Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies.” The Journal of Applied Psychology 88 (5):879–903. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879.

- Peltokorpi, V., and F. J. Froese. 2012. “The Impact of Expatriate Personality Traits on Cross-Cultural Adjustment: A Study with Expatriates in Japan.” International Business Review 21 (4):734–46.

- Prysmakova, P. 2021. “Contact with Citizens and Job Satisfaction: Expanding Person-Environment Models of Public Service Motivation.” Public Management Review 23 (9):1339–58.

- Qin, X., X. Liu, J. A. Brown, X. Zheng, and B. P. Owens. 2021. “Humility Harmonized? Exploring Whether and How Leader and Employee Humility (in) Congruence Influences Employee Citizenship and Deviance Behaviors.” Journal of Business Ethics 170 (1):147–65.

- Ravasi, C., X. Salamin, and E. Davoine. 2015. “Cross-Cultural Adjustment of Skilled Migrants in a Multicultural and Multilingual Environment: An Explorative Study of Foreign Employees and Their Spouses in the Swiss Context.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management 26 (10):1335–59.

- Saleem, S., M. I. Rasheed, M. Malik, and F. Okumus. 2021. “Employee-Fit and Turnover Intentions: The Role of Job Engagement and Psychological Contract Violation in the Hospitality Industry.” Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 49:385–95.

- Shanock, L. R., B. E. Baran, W. A. Gentry, S. C. Pattison, and E. D. Heggestad. 2010. “Polynomial Regression with Response Surface Analysis: A Powerful Approach for Examining Moderation and Overcoming Limitations of Difference Scores.” Journal of Business and Psychology 25 (4):543–54.

- Subramaniam, A., R. Othman, and M. Sambasivan. 2010. “Implicit Leadership Theory among Malaysian Managers: Impact of the Leadership Expectation Gap on Leader-Member Exchange Quality.” Leadership & Organization Development Journal 31 (4):351–71.

- Templer, K. J. 2010. “Personal Attributes of Expatriate Managers, Subordinate Ethnocentrism, and Expatriate Success: A Host-Country Perspective.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management 21 (10):1754–68.

- Tsai, C. J., C. Carr, K. Qiao, and S. Supprakit. 2019. “Modes of Cross-Cultural Leadership Adjustment: Adapting Leadership to Meet Local Conditions and/or Changing Followers to Match Personal Requirements?” The International Journal of Human Resource Management 30 (9):1477–504.

- Tsui, A. S., H. U. I. Wang, K. Xin, L. Zhang, and P. P. Fu. 2004. “Let a Thousand Flowers Bloom: Variation of Leadership Styles among Chinese CEOs.” Organizational dynamics 33 (1):5–20.

- Varma, A., P. Budhwar, and S. Pichler. 2011. “Chinese Host Country Nationals’ Willingness to Help Expatriates: The Role of Social Categorization.” Thunderbird International Business Review 53 (3):353–64.

- Vroom, V. H., and A. G. Jago. 2007. “The Role of the Situation in Leadership.” The American Psychologist 62 (1):17. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.62.1.17.

- Walder, A. G. 1988. Communist Neo-Traditionalism: Work and Authority in Chinese Industry. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Weber, E., M. Büttgen, and S. Bartsch. 2022. “How to Take Employees on the Digital Transformation Journey: An Experimental Study on Complementary Leadership Behaviors in Managing Organizational Change.” Journal of Business Research 143:225–38.

- Weiss, H. 2002. “Deconstructing Job Satisfaction: Separating Evaluations, Beliefs, and Affective Experiences.” Human Resource Management Review 12:173–94.

- Weiss, H. M., and R. Cropanzano. 1996. “Affective Events Theory: A Theoretical Discussion of the Structure, Causes and Consequences of Affective Experience at Work.” In Research in Organizational Behavior, edited by B. M. Staw and L. L. Cummings. Greenwich, CT: JAI.

- Xu, M., X. Qin, S. B. Dust, and M. S. DiRenzo. 2019. “Supervisor-Subordinate Proactive Personality Congruence and Psychological Safety: A Signaling Theory Approach to Employee Voice Behavior.” The Leadership Quarterly 30 (4):440–53.

- Yang, J., Z. X. Zhang, and A. S. Tsui. 2010. “Middle Manager Leadership and Frontline Employee Performance: Bypass, Cascading, and Moderating Effects.” Journal of Management Studies 47 (4):654–78.

- Yue, L., C. Men, and X. Ci. 2022. “Linking Perceived Ethical Leadership to Workplace Cheating Behavior: A Moderated Mediation Model of Moral Identity and Leader-Follower Value Congruence.” Current Psychology ahead-of-print, 1–13. doi: 10.1007/s12144-022-03279-5.

- Yukl, G. 2013. Leadership in Organiations. 8th ed. England: Pearson Education.

- Yukl, G., A. Gordon, and T. Taber. 2002. “A Hierarchical Taxonomy of Leadership Behavior: Integrating a Half Century of Behavior Research.” Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies 9 (1):15–32.

- Yukl, G. 2019. Leadership in Organizations. 9th ed. Harlow: Pearson.

- Zaccaro, S. J., J. A. Gilbert, K. K. Thor, and M. D. Mumford. 1991. “Leadership and Social Intelligence: Linking Social Perspectiveness and Behavioral Flexibility to Leader Effectiveness.” The Leadership Quarterly 2 (4):317–42.

- Zhang, X., M. Kaiser, P. Nie, and A. Sousa-Poza. 2019. “Why Are Chinese Workers so Unhappy? A Comparative Cross-National Analysis of Job Satisfaction, Job Expectations, and Job Attributes.” PLOS One 14 (9):e0222715. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0222715.

- Zhang, Z., M. O. Wang, and J. Shi. 2012. “Leader-Follower Congruence in Proactive Personality and Work Outcomes: The Mediating Role of Leader-Member Exchange.” Academy of Management Journal 55 (1):111–30.

- Zhao, H., Q. Zhou, P. He, and C. Jiang. 2021. “How and When Does Socially Responsible HRM Affect Employees’ Organizational Citizenship Behaviors toward the Environment?” Journal of Business Ethics 169 (2):371–85.