Abstract

Control-oriented HRM, performance appraisal dissatisfaction, and reputation concern are found to have a “muzzling effect” on teachers, partly through leader-member exchange. Does this effect vary with the level of (a) marketization, and (b) school popularity and privilege? These questions are examined using survey data from Norwegian upper secondary school teachers (N = 1055), and analyzed with path analysis and bootstrapping. Results support some, but not all, hypotheses. Analyses show that the inhibiting effects of performance appraisal dissatisfaction and reputation concern on employee voice are stronger in the highly marketized school field of Oslo than in schools in other areas, and vary with marketization level. The inhibiting effect of reputation concern on voice is stronger in privileged than in marginalized schools and varies with the level of privilege. No such patterns for the inhibiting effects of control-oriented HRM and PA dissatisfaction are found. The findings indicate that reputation management theory takes center stage, as voice is regarded as a reputation management tool. Institutional logics are too found to be crucial when understanding the results. Implications are tied to reputation concerns, leading to a stronger muzzling effect on teachers in marketized areas than elsewhere, and in privileged schools as compared to marginalized schools. This calls for caution with regard to differing marketization and privilege levels in school settings.

Introduction

The last decade’s major conflicts related to the school field in the Norwegian capital of Oslo (Malkenes Citation2014; Haugen Citation2020) are the backdrop of this article. Fueled by New Public Management reforms in the 1990s and early 2000s, school authorities “took a neoliberal approach to school policies, resulting in increased assessment, a national test system, per capita funding, and a system of accountability” (Dahle Citation2022, 178; Haugen Citation2021; Krejsler and Moos Citation2021). This neoliberal turn was met with criticism and public debate. The resulting marketization and focus on reputation building and branding have led to restrictions on teacher voice and public silence in upper secondary schools (Dahle Citation2022; Dahle and Wæraas Citation2020). The empirical focus of the present article is on examining whether voice restrictions vary with level of marketization and school privilege.

As public sector schools in Norway serve the public interest by providing quality education for all “regardless of social and cultural background” (Imsen, Blossing, and Moos Citation2017, 568; Myhre Citation2021; Pinheiro et al. Citation2019), teacher silence is unexpected. One could expect that agents for the public interest, here teachers, engaged in public debate. But teachers seldom express their opinions in public forums. Such limited use of voice is arguably linked to the last two decades’ overall educational policy based on deregulation and marketization of the school field (Haugen Citation2020), implying that schools need to build and protect their reputation to succeed in the current quasi-market. Here, the use of voice is seen as a potential hazard, and unwanted use of voice is sanctioned through the HRM function (Dahle and Wæraas Citation2020).

Introducing a free choice of schools with grades as the sole criteria for admission in a city strongly divided along economical, social, and ethnic lines, that is, Oslo (Ljunggren and Andersen Citation2015; Haandrikman et al. Citation2023) has created huge reputational differences, with reputable, privileged schools receiving a wealth of student applications, and less reputable, marginalized schools not receiving enough applications to fill their available places (Haugen Citation2020). Such pronounced differences in market position seem to affect employee voice, so that voice is more restricted in privileged schools than in marginalized schools (Dahle and Wæraas Citation2020). Relatedly, deregulation involves the introduction and use of practices rooted in instrumentality and accountability, including a somewhat control-oriented HRM approach and, relatedly, performance appraisal of teachers, leading to a “muzzling effect” on teachers (Dahle Citation2022).

The present article examines whether factors like reputation concern, control-oriented HRM, and dissatisfaction with performance appraisal have an inhibiting effect on teacher voice in three different geographical areas characterized by different levels of school marketization, reflecting the extent that the inhibiting effect varies with the level of marketization. Additionally, as both reputation concern and control levels seem to differ with school popularity and privilege (Dahle and Wæraas Citation2020), the article examines whether the inhibiting effect on voice differs between privileged and marginalized schools in Oslo.

Relatively few scholars have examined inhibitors to teacher voice (Zeng and Xu Citation2020; Sağnak Citation2017; Alqarni Citation2020). Even fewer have examined whether reputation concern, control-oriented HRM, and performance appraisal dissatisfaction inhibit teacher voice. No studies examining whether this varies with marketization level, level of popularity, or degree of privilege were found. Hence, the overall research question for the present study is:

To which extent does the inhibiting effect of reputation concern, control-oriented HRM and performance appraisal dissatisfaction on teacher voice vary with level of marketization and school privilege?

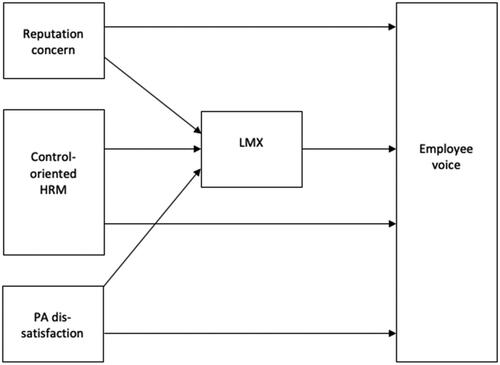

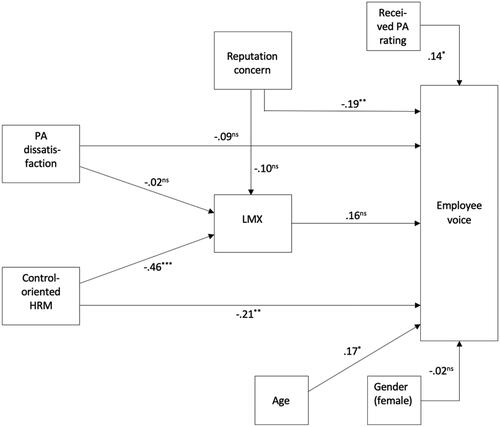

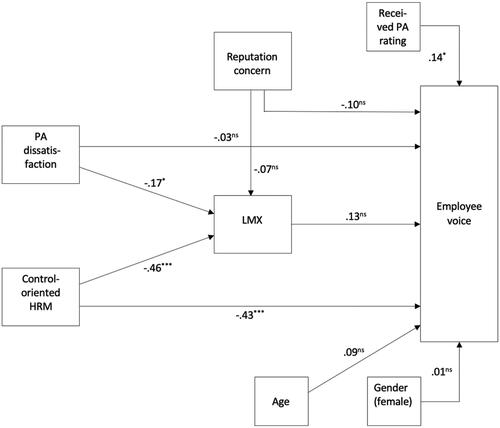

In the following section, the theoretical perspectives and hypotheses for the study are presented, followed by the methodological strategy, empirical findings, and discussion. The conceptual model for the study is shown in .

Theory and hypotheses

In his seminal work, Hirschman (Citation1970, 30) regarded voice as “any attempt at all to change, rather than to escape from, an objectionable state of affairs, whether through individual or collective petition to the management directly in charge, through appeal to a higher authority with the intention of forcing a change in management, or through various types of actions or protests, including those that are meant to mobilize public opinion.” Hirschman’s take on employee voice involves reacting to something which is negative. Later much of the research on voice had a more supportive flair, with improvement as the main goal (Zhang, Liang, and Li Citation2019; Morrison Citation2011; Dyne, Ang, and Botero Citation2003). The present article argues that the voice construct should encompass both a supportive and a less supportive and critical dimension. This is particularly pertinent in settings where organizations are exposed to market pressure and engage in reputation building.

Voice as a reputation management tool

As schools in marketized settings compete for students, their reputation is defined as “a collective representation of a brand’s past actions and results that describes the brand’s ability to deliver valued outcomes to multiple stakeholders” (Harris and de Chernatony Citation2001, 445), and is key to attract high-performing students, and thus, public funding. To build a strong brand, an organization’s identity needs to correspond with its reputation, so the gap between them is as small as possible (Javed et al. Citation2020). If the gap is large, managers need to “work with staff to reduce these gaps and eliminate incongruence” (Harris and de Chernatony Citation2001, 445; De Chernatony Citation1999). In such situations, an imperative is to get employees to speak with “one single voice” (Xiong et al. Citation2019; Argenti and Forman Citation2002), and not act as “brand saboteurs” (Peng et al. Citation2021; Ind Citation2001). Employees’ use of voice arguably carries a risk, as they might communicate something that can harm the desired reputation.

In contrast to traditional views of reputation management, where employees are trusted to be “corporate ambassadors” (Brockhaus et al. Citation2020; Alsop Citation2004), recent studies find that voice restrictions and message control, not corporate ambassadorship, is the preferred strategy by employers eager to get their employees to support and build the brand (Wæraas and Dahle Citation2020; Dahle and Wæraas Citation2020). On this note, voice is defined as not only a means to improve, but also to alter or change the current working of an organization. Building on the work by Hirschman (Citation1970), Bashshur and Oc (Citation2015, 1531) define voice as “the discretionary or formal expression of ideas, opinions, suggestions, or alternative approaches directed to a specific target inside or outside of the organization with the intent to change an objectionable state of affairs or to improve the current functioning of the organization, group, or individual.” They position voice as “problem focused, change oriented, and constructive” (Bashshur and Oc Citation2015, 1531). The constructive dimension is about improving, that is, making contributions to enhance the running of the organization. Objectionable sides of the organization are at the core of the problem dimension, which involves contributing to solving a problem. The change dimension carries a wish to alter the current state of the organization. According to Bashshur and Oc, “a change motive is the common factor across most definitions of voice,” and “changing the current state of affairs should be the most proximal dependent variable of voice” (Bashshur and Oc Citation2015, 1531).

The dimensions correspond with the constructs of promotive and prohibitive voice, developed by Liang, Farh, and Farh (Citation2012). The constructive dimension is mirrored in the promotive voice, defined as “employees’ expression of new ideas or suggestions for improving the overall functioning of their work unit or organization” (Liang, Farh, and Farh Citation2012, 74). Prohibitive voice, defined as “employees’ expression of concern about work practices, incidents, or employee behavior that are harmful to their organization” (Liang, Farh, and Farh Citation2012, 74; Liang, Shu, and Farh Citation2019), mirrors the critical dimension. For reputation management purposes, employers seem to want to restrict the use of prohibitive voice (Dahle and Wæraas Citation2020; Wilkinson, Sun, and Mowbray Citation2020).

Voice restrictions in light of institutional logic responses

The present article advances the argument that organizations’ responses to institutional logics reflect their efforts to build a favorable reputation, which, in turn, may lead to voice restrictions.

As a consequence of the economization of public sector upper secondary schools, the school field works as a quasi-market (Rasmussen and Dovemark Citation2022) induced with an institutional logic commonly present in markets (Ertimur and Coskuner-Balli Citation2015). Not surprisingly, bureaucratic (Costa Oliveira, Lima Rodrigues, and Craig Citation2023; Weber Citation1978), professional (Puaca Citation2021; Hattke, Vogel, and Woiwode Citation2016; Bukve Citation2012), and administrative logics (Selwyn Citation2023; Vican, Friedman, and Andreasen Citation2020) may be active in this particular field, as well, but market logics are found to be particularly influential in the school field (Pietilä and Pinheiro Citation2021; Dahle Citation2020; Pagès Citation2021; Lee, Kwan, and Li Citation2020). Moreover, the perfusing qualities of market logics may differ with the degree of marketization (Dahle Citation2021), and to some extent, with school privilege. As follows, such variations may lead to organizations facing institutional logics in different ways. Different responses may explain why organizations demonstrate different employee voice management strategies: Schools that are highly exposed to market forces may be infused with market logics, and, as a consequence, may be highly concerned about their reputation, which again may lead to restrictions on teacher voice. Schools less exposed to market pressure are probably less affected by market logics and are less reputation sensitive, allowing for teacher voice.

Based on this reasoning, the results in the present article are examined and analyzed in light of institutional logics theory, including responses to institutional logics. The construct of institutional logics is defined as “the socially constructed, historical patterns of material practices, assumptions, values, beliefs, and rules by which individuals produce and reproduce their material subsistence, organize time and space, and provide meaning to their social reality” (Thornton and Ocasio Citation1999, 804). Such patterns materialize as mere belief systems affecting the cognitive, behavioral, and communicative actions of organizational members (Alford and Friedland Citation1985; Friedland and Alford Citation1991; DiMaggio Citation1979; Durand and Thornton Citation2018). Thornton and Ocasio (Citation1999, 804) even see it as a guide to “interpret the organizational reality.” Logics are embedded in vital institutions in society, such as capitalism, bureaucracy, democracy, family, and truth (incorporating religion and science) (Friedland and Alford Citation1991). This was developed by Thornton and Ocasio (Citation1999) and Thornton (Citation2004) to include institutions like the state, the market, the family, religion, the profession, the corporation, and community (Thornton, Ocasio, and Lounsbury Citation2012), comprising a set of potential competing logics, particularly in educational institutions (Shields and Watermeyer Citation2020; Ingstrup, Aarikka-Stenroos, and Adlin Citation2021; Henningsson and Geschwind Citation2022).

In the present article, the spotlight is on how organizations in general and schools in particular deal with and respond to prevailing institutional logics (Anderson-Gough et al. Citation2022). Of particular interest is the categorization of strategic responses to institutional processes done by Oliver (Citation1991). She identifies a set of common responses, namely acquiescence, compromise, avoidance, defiance, and manipulation (Oliver Citation1991, 152). Defiance is an active response, which is about actively resisting institutional pressure or logics through dismissal, challenge, or attack. Manipulation is a less active response, where the primary goal is to change expectations set up by institutional logics or directly exert influence on the forces that express the prevailing logic. Avoidance is a response based on steering clear of logics through precluding, buffering, or escaping from institutional logics pressure. Aiming to reach a compromise, the compromise response strives to balance different logics, accommodate differing institutional elements or logics through pacifying strategies, or bargain between different stakeholders or logics. The response of acquiescence means that organizations either fully adhere to institutional logics (habiting), mimic institutional models based on logics (imitation), or abide by such logics (compliance), and, as such, acquiesce to the reigning logics. The present article argues that schools in marketized areas facing prevailing market logics will acquiesce to logics, while schools in less marketized areas may choose one of the less welcoming responses, and that these differences are linked to different levels of voice restrictions.

Inhibitors of employee voice

Several review articles identify common inhibitors of employee voice, including personality factors like introversion, lack of initiative, little conscientiousness, and self-perceived status (Morrison Citation2023), career risks, instrumental job climate, abusive leadership, work place stressors (Morrison Citation2014; Chamberlin, Newton, and Lepine Citation2017), lack of high-commitment HRM (Marchington Citation2007), dissatisfaction with working conditions and wages, and low levels of organizational support (Ng and Feldman Citation2012). Dahle (Citation2022) found that both control-oriented HRM, performance appraisal dissatisfaction, and reputation concern function as inhibitors of employee voice, partly mediated by the leader-member exchange. Relatedly, schools in a highly marketized area are found to have a markedly stronger concern for reputation and branding than schools in less marketized areas (Dahle Citation2021). In addition, schools exposed to market pressure demonstrated a more differentiating branding than schools that were less exposed to market forces. Based on studies showing a positive relationship between voice and reputation management and branding, respectively (Wæraas and Dahle Citation2020), it is expected that the three independent variables in the present article have a stronger relationship with employee voice in a marketized area like Oslo than in less marketized areas. This leads to the following hypotheses:

The inhibiting effect of reputation concern on employee voice is significantly stronger in Oslo than in the suburbs surrounding the city (H1a), and in the northern county of Troms and Finnmark (H1b).

The inhibiting effect of control-oriented HRM on employee voice is significantly stronger in Oslo than in the suburbs surrounding the city (H2a), and in the northern county of Troms and Finnmark (H2b).

The inhibiting effect of PA dissatisfaction on employee voice is significantly stronger in Oslo than in the suburbs surrounding the city (H3a), and in the northern county of Troms and Finnmark (H3b).

The inhibiting effect of reputation concern on employee voice is significantly stronger in privileged schools than in marginalized schools in Oslo (H4).

The inhibiting effect of control-oriented HRM on employee voice is significantly stronger in privileged schools than in marginalized schools in Oslo (H5).

The inhibiting effect of PA dissatisfaction on employee voice is significantly stronger in privileged schools than in marginalized schools in Oslo (H6).

The mediation effect of LMX on the relationship between reputation concern and employee voice is significantly stronger in Oslo than in the suburbs surrounding the city (H7a), and in the northern county of Troms and Finnmark (H7b).

The mediation effect of LMX on the relationship between reputation concern and employee voice is significantly stronger in privileged schools than in marginalized schools in Oslo (H8).

Methods

The formulated research question was examined using data from public sector upper secondary schools in Norway. Public sector schools in Norway are part of “the Nordic model of education,” and offer education of roughly the same quality to all students (Imsen, Blossing, and Moos Citation2017, 568). Due to a highly regulated private school market (Haugen Citation2020), there is limited competition between private and public sector schools. Fueled by New Public Management reforms, however, neoliberal policies were introduced at the beginning of the new millennium, resulting in widespread student testing, per capita funding, and, partly, free choice of school (Strømmen-Bakhtiar and Timoshenko Citation2021; Imsen, Blossing, and Moos Citation2017). The outcome was marketization and economization of the school field. At the same time, control-oriented HRM practices, including rating of employees and voice restrictions, have crept into Norwegian schools (Paulsen and Moos Citation2020; Dahle and Wæraas Citation2020; Kuvaas and Dysvik Citation2016; Røvik Citation2007)

As free choice of school has been introduced as an option for municipalities and is not mandatory, the level of marketization varies between areas, with Oslo as the most marketized area (Haugen Citation2020; Hovdenak and Stray Citation2015). In the quasi-market in Oslo schools compete for students, a “money follows the student” approach prevails, and accountability is a pronounced feature (Bjordal Citation2022; Haugen Citation2020). As a consequence of market forces, schools’ popularity or market position, both within Oslo and between Oslo and other areas of the country, varies. Since public sector schools carry all these dimensions, they constitute a promising setting for examining relationships between the chosen independent variables and employee voice, and the extent that these vary with marketization and privilege.

Sample and procedure

The main source of data in the present study is survey data from public sector upper secondary schools in areas chosen by strategic cluster sampling (Stratton Citation2021), namely the mostly rural northern county of Troms and Finnmark, the suburban areas of Follo and Romerike in the county of Viken, and the urban capital of Oslo. The areas reflect central dimensions in Norwegian society in general and in the school sector in particular, namely the urban-rural dimension, the north-south dimension (Blossing, Imsen, and Moos Citation2014), and different levels of marketization.

Schools in Oslo were divided into two parts based on market position. In the school system in Oslo, student grades are the only valid admission criteria, and schools are obliged by law to accept students with good enough grades. The grades needed for admission thus function as a measure of schools’ market position, and, as follows, popularity. In the socially, economically, and ethnically divided city of Oslo (Haandrikman et al. Citation2023), there are huge differences in school popularity. Using official admission statistics for 2019/2020 by the Oslo municipal administration, schools were categorized into marginalized schools (requiring 10–37.4 admission points) and privileged schools (35.5–60 admission points). Initially, a middle category was identified, as well. For analytic purposes related to the present article, schools in the middle category were placed into one of the other two categories.

A web-based questionnaire was in October 2018 electronically distributed to teachers in all public sector upper secondary schools in the three areas, in a total of 65 schools. The questionnaire was sent to teachers’ email addresses publicly available on the school websites. Sixty percent of teachers at each school were randomly selected and received the questionnaire, in total 3,414 teachers. Within a month 1,264 responses were received, representing a response rate of 37%. Responses represented a fair coverage of the teachers and their schools. The 397 responses from teachers in Oslo schools represented 37.6% of the teachers who received the questionnaire in that area, while the 422 responses from teachers in the suburbs represented 40.0% of teachers who received the questionnaire. For responses from teachers in the north, the rate was 19.6%. Responses were received from all schools in the three areas, and the average number of responses from each school was 16, indicating a satisfactory coverage of the schools.

After the omission of incomplete responses, 1,055 responses were used. Only responses from respondents who reported that they had been rated were included. Sample characteristics, as seen in , illustrate that the sample was relatively balanced with regard to gender and age, but was dominated by respondents with higher education compared to lower-educated respondents. All respondents were informed that the research project had been approved by NSD—Norwegian Center for Research Data.

Table 1. Sample characteristics.

All items were assessed on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Items had been previously validated and published with satisfactory reliability and internal consistency at the time of measurement. A few scales were adapted to fit the theoretical model. English worded scales were translated into Norwegian, and translated back into English (Brislin Citation1986). Full scales and items are included in Appendix A.

The model and hypotheses were tested with path analysis, which main fore is the facilitation of simultaneous testing of entire models with related regression relationships (MacKinnon Citation2008), including both direct and indirect relationships between variables (Kline Citation2015). AMOS 27.0 was used to analyze the data, and bootstrapping was utilized to test indirect effects and mediation (Preacher, Rucker, and Hayes Citation2007). Mediation was not tested with the causal steps approach by Baron and Kenny (Citation1986), but through simultaneous testing of paths (Meule Citation2019; Zhao, Lynch, and Chen Citation2010). Several fit indices (Vandenberg Citation2006) were applied to assess model fit: First, the likelihood ratio or “Chi-square” test showed CMIN/df values 3.3 (df = 1), indicating a good model fit. Then the absolute root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), the comparative fit index (CFI), and the normed fit index (NFI), both incremental, were applied. Results revealed good model fit: RMSEA = .047, CFI = .997, NFI = .996 (Lei and Wu Citation2007, 36–37).

As common method bias might affect survey data collected at one point in time, several ex ante steps were taken to avoid this: A large sample size (Katou and Budhwar Citation2006), different measures types (Eisenhardt and Tabrizi Citation1995), a large number of items, an exhaustive data collecting process (Kintana, Alonso, and Olaverri Citation2006), and a complex model, all to prevent cognitive mapping by respondents (Chang, Van Witteloostuijn, and Eden Citation2010). Post ante, a common latent factor test was conducted (Podsakoff et al. Citation2003). First, a common latent factor (CLF) was included in the model, and standardized regression weights were extracted after running the model. After running the model again without the CLF, regression weights from both models were compared (MacKenzie and Podsakoff Citation2012). Very small differences (<0.1) between paths were found, indicating little common method bias.

Measures

To assess the usability and reliability of items, a pilot study with 80 respondents was completed first. To explore the factor structure of items, an exploratory factor analysis with principal component factoring was carried out on the full set of data using SPSS 26.0. A confirmatory factor analysis with maximum likelihood estimation was then performed using AMOS 27.0, to assess the factor structure further.

Control-oriented HRM

An adapted version of the HRM scale by Lepak and Snell (Citation2002) was used to measure the HRM approach. A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using non-orthogonal direct oblimin rotation, and a CFA with varimax rotation (Cattell Citation2012; Tabachnick, Fidell, and Ullman Citation2007) showed that factors were uncorrelated. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test showed meritorious/marvelous sampling adequacy (.89) (Kaiser Citation1974). The Bartlett’s test of sphericity revealed significance at the .000-level. All items, as shown in , had an eigenvalue higher than 1 and a factor loading of .60 or higher. The items are loaded on five factors: Compensation, empowerment, performance appraisal, recruitment, and training and development. The factors corresponded with HR practices commonly associated with high-commitment HRM (Boon and Kalshoven Citation2014; Lepak and Snell Citation2002). Reverse coding was applied for the scale to reflect control-oriented HRM. The rotated factors captured 64.11% of the variance, and there were no cross-loadings. The scale consisted of 16 items and had a Cronbach’s alpha value of α = .84.

Table 2. Factor loading analysis based on a principal component analysis with varimax rotation performed with SPSS for 17 items from the high-commitment scale by Lepak and Snell (Citation2002).

Performance appraisal dissatisfaction

The three-item satisfaction with the performance appraisal system scale developed by Giles and Mossholder (Citation1990) was used to measure teacher’s satisfaction with the PA system. Instead of the original 6-point Likert scale a 5-point scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), was used. The coding was reversed to get a scale reflecting dissatisfaction. A sample item is: “Generally, I feel the organization has an excellent performance appraisal system.” A principal component analysis extracted only one component. The Bartlett’s test was significant at the .000-level, and the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin gave a value of .74. The scale had a Cronbach’s alpha of α = .90.

Reputation concern

The schools’ concern for their reputation was measured with a further developed version of the six-item scale by Wæraas (Citation2014, 197). The items were reworded to fit research in all organizations, and three items were adjusted to better reflect concern for reputation in school settings. Items were assessed on a 5-point Likert scale with a range from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). A sample item is: “Management are concerned about improving the organization’s reputation.” Only one component was extracted by a principal component analysis. The Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant at the .000-level, and the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin value was .88. The scale had a Cronbach’s alpha of α = .86.

Leader-member exchange (LMX)

The quality of the dyadic relationship between leader and employee was measured using the scale by Graen and Uhl-Bien (Citation1995). A 5-point scale ranging from “none” to “very high” was used. A sample item is: Regardless of the amount of formal authority your leader has, what are the chances that he/she would “bail you out” at his/her expense. Graen and Uhl-Bien state that “the LMX construct has multiple dimensions, but these dimensions are so highly correlated they can be tapped into with the single measure of LMX” (Graen and Uhl-Bien Citation1995, 237), explaining why two components were extracted by a principal component analysis. The scale had a Cronbach’s alpha of α = .85. The Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant at the .000-level, and the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin value was .83.

Employee voice

The 10 item scale by Liang, Farh, and Farh (Citation2012), translated into Norwegian by Svendsen, Unterrainer, and Jønsson (Citation2018), was used to measure employee voice. The prohibitive and promotive dimensions were measured with five items each, and assessed on a 5-point Likert scale spanning from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Sample items include “I make constructive suggestions to improve the unit’s operation” (promotive) and “I dare to point out problems when they appear in the unit, even if that would hamper relationships with other colleagues” (prohibitive). A principal component analysis extracted two components, one for each of the two dimensions. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin value was .91, and the Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (.000). The Cronbach’s alpha value was α = .88.

Of several control variables included in the questionnaire, the variables gender, age, and received rating were included in the model. Other control variables had no effect on the dependent variable and were thus excluded from the model (Becker Citation2005). Gender was dummy-coded (female = 1, male = 0), age was operationalized in actual numbers, and received rating was operationalized on a high, medium, and low level.

Results

shows means, standard deviations, and correlations for the full set of data. Control-oriented HRM, PA dissatisfaction, reputation concern, and LMX are all significantly correlated to employee voice. The highest are correlations between control-oriented HRM and PA dissatisfaction (r = 0.43) and LMX (r = 0.43). Yet, the variance inflation factor (VIF) for each independent variable is rather low (control-oriented HRM: 1.260, PA dissatisfaction: 1.231, and reputation concern: 1.027) and well below the recommended threshold value of 4.0 (Hair et al. Citation2010), there is little multicollinearity in the data.

Table 3. Means, standard errors, and correlations.

Hypotheses 1–3

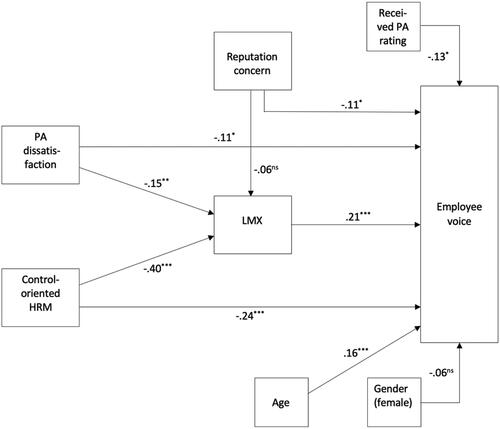

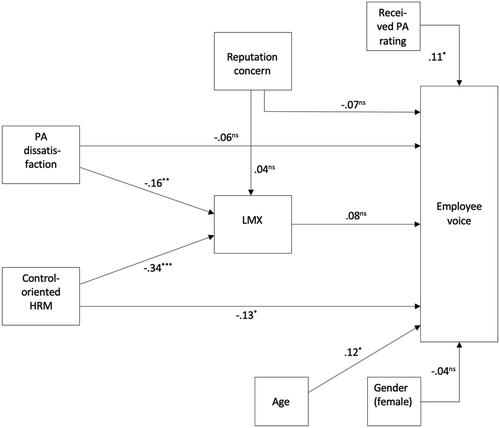

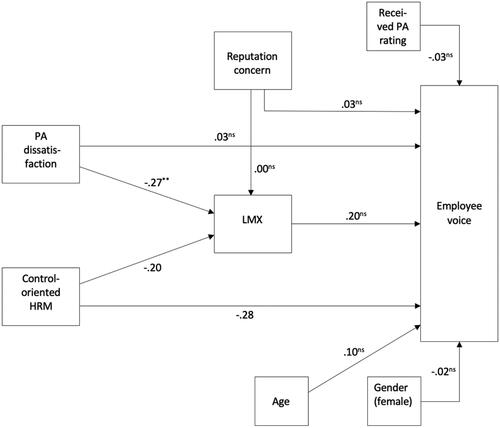

Results for direct and indirect relationships are shown in and . Based on analyses of direct relationships using Amos 26.0, there is a significant negative effect of reputation concern on employee voice in Oslo schools (β = −.113, p = .010), meaning that reputation concern has an inhibiting effect on voice. There is no such effect neither in the suburbs (β = −.066, p = .175) nor in the northern schools (β = .028, p = .678). Hence, hypotheses H1a and H1b are supported.

Table 4. Direct, indirect, and total effects.

Control-oriented HRM has a significant negative effect on voice both in Oslo (β = −.239, p = .001), the suburbs (β = −.131, p = .037), and in the north (β = −.285, p = .001). To test whether the differences are statistically significant, the procedure for testing overlapping confidence intervals, as recommended by Cumming (Citation2009), is utilized. Estimation of 95% confidence intervals via bias-correlated bootstrapping with 1,000 re-samples shows that the confidence intervals for the highest and lowest estimate (north, suburbs) overlap more than 50% (.263 > .181). Hence, differences are not significant, and H2a and H2b are not supported. The negative effect of PA dissatisfaction on voice is significant in Oslo (β = −.108, p = .032), but not in the suburbs (β = −.065, p = .189). In the north, there is an insignificant positive effect (β = .029, p = .690). Thus, H3a and H3b are supported.

Hypotheses 4–6

Turning to differences within Oslo, reputation concern has a significant negative effect on voice in privileged schools in the city (β = −.189, p = .003), but not in marginalized schools (β = −.103, p = .141). This provides support for H4. Control-oriented HRM, on the other hand, has a significant negative effect both in privileged (β = −.212, p = .007) and marginalized schools (β = −.432, p = .001) in Oslo. Again, using the procedure by Cumming (Citation2009), confidence intervals overlap more than 50% (.362 > .322), telling us that differences are not significant. As follows, H5 is not supported. The negative effect of PA dissatisfaction on employee voice is larger in privileged (β = −.086, p = .254) than in marginalized schools (β = −.033, p = .716). However, as none of the effects are statistically significant, H6 is not supported.

Hypotheses 7–8

We note that there is no significant direct effect of LMX on employee voice in either of the models. This can be interpreted as an indication that leadership has a limited impact on employee voice, which contradicts previous findings. Yet, it is important to keep in mind that school teachers in Norway traditionally have been given a certain degree of professional autonomy, and have been subject to moderate levels of direct leadership. This may explain the absence of significant direct effects of LMX on voice. However, this is not the focal point of the present article. Instead, the spotlight is on the mediating qualities of LMX and the indirect effects of the independent variables on voice, plus how these qualities differ with the level of marketization and privilege.

Bootstrapping (95% confidence intervals, z = 5,000 samples) was utilized to test for indirect effects with LMX as a mediator. The indirect effect of reputation concern on voice is significant in Oslo (β = −.029, p = .041), but not in the suburbs (β = −.002, p = .875) or in the north (β = −.008, p = .752). On this, H7a and H7b are supported. The indirect effect of reputation concern is significant in privileged schools (β = −.049, p = .010), but not in marginalized schools (β = −.016, p = .227), which provides support for H8.

Discussion

As summed up in , the findings confirm the assumptions that the negative effect of reputation concern is significantly stronger in the highly marketized school field in Oslo than in the suburbs and in the rural north.

Table 5. Support of hypotheses.

Theoretical and empirical contributions

This result can be explained by regarding voice as a reputation management tool, reflecting an acquiescent response to institutional logics rooted in marked principles. As such, a favorable reputation is key to attract good students, and, thus, secure solid funding. For schools reputation building and maintenance is a necessary part of succeeding in the school market, corresponding directly with the fact that reputation concern inhibits employee voice.

The position of reputation may also explain why the effect of performance appraisal dissatisfaction, too, is stronger in Oslo than in the suburbs and in the north. In schools highly exposed to market pressure and infused with market logics, the relationship between employer and employee may be more instrumental in Oslo schools than elsewhere (Dahle Citation2022), involving both marketization and control-oriented HRM. Such an instrumental climate may influence teachers’ use of voice: PA dissatisfaction may initially trigger dissatisfied employees to speak up in critical ways (Liang, Farh, and Farh Citation2012), but employees may instead choose to stay silent, either as a form of self-protection to avoid hurtful sanctions (Chou and Chang Citation2020), or, perhaps also as a consequence, not to hurt the school’s reputation. The present article argues that such a mechanism is more prominent in market-exposed fields infused with market logics like Oslo, than in less marketized fields like the suburbs or the north.

The negative effect of control-oriented HRM on voice is significant in all three areas, but it is, however, not stronger in Oslo than in the other areas. While this was not as hypothesized, it can be understood in light of the interwoven qualities of reputation, HRM, and voice: High-commitment HRM may promote voice, while the opposite is the case with control-oriented HRM (Marchington Citation2007, 243). We note, as well, that such an HRM approach is found to have a pronounced effect on a diverse set of variables in organizations (Beer, Boselie, and Brewster Citation2015), including employee voice (Bashshur and Oc Citation2015; Marchington Citation2007). In addition, since no studies find the link between control-oriented HRM and voice to vary significantly between school areas, the inhibiting effect of control-oriented HRM will not differ significantly between the three school fields and their different levels of marketization.

Turning to results for privileged vs. marginalized schools, the findings confirm the assumption that the inhibiting effect of reputation concern is stronger in privileged than in marginalized schools. This, too, can be explained by reputation management theory. As school executives regard voice as a reputation management tool, they will use the tool actively to build and protect a favorable reputation. When teachers are not trusted to be reputation or brand ambassadors, this may pan out as voice restrictions. The results are in line with prior studies (Dahle and Wæraas Citation2020; Fredriksson and Pallas Citation2016; Byrkjeflot Citation2015; Christensen, Morsing, and Cheney Citation2008) showing more severe voice restrictions in privileged than in marginalized organizations, probably because the privileged have more to lose. Privilege implies being in a favorable position which needs to be defended and maintained.

Findings do not confirm that the inhibiting effect of PA dissatisfaction and control-oriented HRM, respectively, is stronger in privileged than in marginalized schools. Both variables are found to significantly inhibit voice in both privileged and marginalized schools, but the effect does not differ significantly between the privileged and marginalized schools. No studies show that the inhibiting effect of control-oriented HRM on voice (Marchington Citation2007, 243) varies with level of privilege, which entails that this effect overrides consequences of potential differences in privilege, leading to no significant differences between privileged and marginalized schools. The same argument may be brought forward as a potential explanation to why the effect of PA dissatisfaction does not differ with the level of privilege. In addition, this may indicate that an instrumental climate exists in both popular and less popular schools in Oslo.

Institutional logics and reputation management theory may together shed light on why LMX has a significant mediating effect between reputation concern and voice is stronger in Oslo, but not in the suburbs and in the north. As the school field in Oslo is highly marketized compared to the other two areas, it is permeated by market logics and reputation concerns. More is at stake, and, as a result, school executives do not take the risk of allowing teachers to be organizational ambassadors, but instead impose voice restrictions. In the instrumental climate in Oslo schools, leadership may be regarded as more important than in less marketized school fields, leading to a situation where employees’ perceptions of and reactions to reputation concerns may lower the LMX quality, which in turn may lead to severe voice restrictions among Oslo teachers. Consequently, the position of middle managers should not be ignored. When leaders want to influence employees’ values, attitudes, and behavior, middle managers play a crucial role. Relatedly, as voice restrictions to some extent will be imposed and implemented by middle managers, the leader-member exchange takes center stage, and the dyad between employee and leader takes on mediating qualities.

The same line of argumentation may explain why LMX has a significant mediating effect between reputation concern and voice in privileged schools, but not in marginalized schools (Dahle and Wæraas Citation2020; Fredriksson and Pallas Citation2016; Byrkjeflot Citation2015; Christensen, Morsing, and Cheney Citation2008). Moreover, it does not seem unlikely that the focus on leadership is stronger in privileged schools with a favorable reputation to defend than in marginalized schools with less to defend, which may explain why the mediating effect of LMX differs with privilege.

The findings provide a new and deeper understanding of restrictions on employee voice. First, voice inhibitors like reputation concern, control-oriented HRM, and PA dissatisfaction are examined. Second, the findings contribute by setting up a more theoretical layer of understanding: Employers, in this case, school executives, utilize voice as a tool for building and managing their reputation. In addition, they regulate teachers’ use of voice through the quality of leader-member exchanges, highlighting the management of voice as a social exchange. On a slightly different note, such voice management strategies are understood as ways of responding to reigning institutional logics. The upper secondary school field in Oslo is organized as a market with a predominant market logic built on economic principles. In line with market logics, reputation concerns are high on the agenda, and, as teachers’ use of prohibitive voice represents a reputational risk, employers respond to the existing institutional logic by acquiescing, and, thus, imposing restrictions on voice. This represents insights into why inhibiting effects of the independent variables on voice are weaker in less marketized areas, like the suburbs and the north, than in Oslo: When an institutional field is little infused with market logics, there is little need for voice restrictions as a response. Relatedly, since reputational concerns are regarded as key and voice is somewhat restricted in privileged schools (Dahle and Wæraas Citation2020), the inhibiting effect of reputation concern on voice, viewed as an acquiescing response to market logics, is stronger in privileged than in marginalized schools.

Limitations and directions for research

Possible limitations of the study include data being based on self-reported measures, which may lower the validity of the results. Common-method bias might be a problem, as the data were solely survey-based and collected at one point in time. Yet, no common method bias was detected. Reverse causality is another possible limitation: Employees facing voice restrictions might perceive the HRM approach to be control-oriented and not the other way around. By strategic cluster sampling the sample reflect dimensions relevant to the study, but it might be a limitation that the sample does not represent the entire population. It is not unlikely that moderation or moderated mediation could have been found, but neither moderation nor moderated mediation was part of this study, which may be seen as a limitation. The Norwegian context, with teachers traditionally little accustomed to control-oriented HRM and school reputation, might be another limitation, as the research setting might differ from corresponding settings in other parts of the world. However, this represents a research opportunity. Such a study might have interesting implications in other geographical locations, for example, other countries, eastern parts of the world, and developing countries. Moreover, other implications might be found in other organizations than schools, for example public sector health institutions, welfare institutions, municipal administrations, and the police, among other professions than teachers, and in organizational fields infused with other institutional logics than market logics. Scholars may also find it fruitful to examine inhibitors to different types of voice, to expand the study to include constructs like organizational silence, ignored voice, sanctioning of voice, and different types of outcomes of voice and voice restrictions.

Conclusions

The findings provide insights for both decision-makers and practitioners. Politicians, school administrators, and school executives should note that the negative effects of reputation concern and performance appraisal dissatisfaction on teacher's voice increase with marketization level, limiting teachers’ scope for voice. This calls for some caution when exposing schools to market forces, as public silence from teachers might lead to a less informed public debate and less transparency toward the public, parents, and students. Muzzling teachers may also have unwanted effects, such as less job engagement, lower motivation, and higher turnover intention. Decision makers and practitioners should also note that the negative effects of reputation concern on voice increase with school privilege. As this highlights how teachers in privileged schools are being muzzled by their schools’ concern for reputation, caution is advised when it comes to increasing the differences in privilege between schools. School executives, in particular, should note that the mediating effect of leadership, here in the form of LMX, increases with both levels of marketization and school privilege. A lesson from this is that leadership is a crucial factor in the relationship between reputation concern and employee voice, and that it plays a more important role the more marketized the organizational field is, and the more privileged upper secondary schools are.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data behind the findings of the present study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Dag Yngve Dahle

Dag Yngve Dahle is Associate Professor of Organization and Leadership at Østfold University College, Norway. He has a PhD in Organization and Leadership from the Norwegian University of Life Sciences, and an Mphil in Sociology from University of Oslo. His empirical and theoretical research interests include HRM, employee voice, organizational branding, and reputation management within private and public sector organizations.

References

- Alford, Robert R., and Roger Friedland. 1985. Powers of Theory: Capitalism, the State, and Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Alqarni, Saleh Ali Y. 2020. “How School Climate Predicts Teachers’ Organizational Silence.” International Journal of Educational Administration and Policy Studies 12 (1):12–27. https://doi.org/10.5897/IJEAPS2020.0642

- Alsop, R. J. 2004. The 18 Immutable Laws of Corporate Reputation: Creating, Protecting and Repairing Your Most Valuable Asset. New York, NY: Free Press.

- Anderson-Gough, Fiona, Carla Edgley, Keith Robson, and Nina Sharma. 2022. “Organizational Responses to Multiple Logics: Diversity, Identity and the Professional Service Firm.” Accounting, Organizations and Society 103:101336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2022.101336

- Argenti, Paul A., and Janis Forman. 2002. The Power of Corporate Communication. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- Baron, Reuben M., and David A. Kenny. 1986. “The Moderator–Mediator Variable Distinction in Social Psychological Research: Conceptual, Strategic, and Statistical Considerations.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 51 (6):1173–82. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173

- Bashshur, Michael R., and Burak Oc. 2015. “When Voice Matters a Multilevel Review of the Impact of Voice in Organizations.” Journal of Management 41 (5):1530–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314558302

- Becker, Thomas E. 2005. “Potential Problems in the Statistical Control of Variables in Organizational Research: A Qualitative Analysis with Recommendations.” Organizational Research Methods 8 (3):274–89. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428105278021

- Beer, Michael, Paul Boselie, and Chris Brewster. 2015. “Back to the Future: Implications for the Field of HRM of the Multistakeholder Perspective Proposed 30 Years Ago.” Human Resource Management 54 (3):427–38. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21726

- Bjordal, Ingvil. 2022. “Soft Privatization in the Norwegian School: Cooperation between Public Government and Private Consultancies in Developing ‘Failing’schools.” Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy 8 (1):42–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/20020317.2021.2022079

- Blossing, Ulf, Gunn Imsen, and Lejf Moos. 2014. The Nordic Education Model. ‘A School for All’ Encounters Neo-Liberal Policy. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Boon, Corine, and Karianne Kalshoven. 2014. “How High‐Commitment HRM Relates to Engagement and Commitment: The Moderating Role of Task Proficiency.” Human Resource Management 53 (3):403–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21569

- Brislin, Richard W. 1986. “The Wording and Translation of Research Instruments.” In Field Methods in Cross-Cultural Research, edited by W. J. Lonner and J. W. Berry, 137–64. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Brockhaus, Jana, Laura Dicke, Patricia Hauck, and Sophia Charlotte Volk. 2020. “Employees as Corporate Ambassadors: A Qualitative Study Exploring the Perceived Benefits and Challenges from Three Perspectives.” In Joy (Advances in Public Relations and Communication Management), edited by A. T. Verčič, R. Tench, and S. Einwiller, 115–34. Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Bukve, Oddbjørn. 2012. Lokal og regional styring: eit institiusjonelt perspektiv [Local and Regional Goverment: An Institutional Perspective]. Oslo: Samlaget.

- Byrkjeflot, Haldor. 2015. “Driving Forces, Critiques, and Paradoxes of Reputation Management in Public Organizations.” In Organization Reputation in the Public Sector, edited by Arild Wæraas and Moshe Maor. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Cattell, Raymond. 2012. The Scientific Use of Factor Analysis in Behavioral and Life Sciences. New York, NY: Springer.

- Chamberlin, Melissa, Daniel W. Newton, and Jeffery A. Lepine. 2017. “A Meta‐Analysis of Voice and Its Promotive and Prohibitive Forms: Identification of Key Associations, Distinctions, and Future Research Directions.” Personnel Psychology 70 (1):11–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12185

- Chang, Sea-Jin, Arjen Van Witteloostuijn, and Lorraine Eden. 2010. “From the Editors: Common Method Variance in International Business Research.” Journal of International Business Studies 41 (2):178–84. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2009.88

- Chou, Shih Yung, and Katelin Barron. 2016. “Employee Voice Behavior Revisited: Its Forms and Antecedents.” Management Research Review 39 (12):1720–37. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRR-09-2015-0199

- Chou, Shih Yung, and Tree Chang. 2020. “Employee Silence and Silence Antecedents: A Theoretical Classification.” International Journal of Business Communication 57 (3):401–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/2329488417703301

- Christensen, Lars Thøger, Mette Morsing, and George Cheney. 2008. Corporate Communications: Convention, Complexity and Critique. London: SAGE.

- Costa Oliveira, Helena, Lúcia Lima Rodrigues, and Russell Craig. 2023. “Reasons for Bureaucracy in the Management of Portuguese Public Enterprise Hospitals–An Institutional Logics Perspective.” International Journal of Public Administration 46 (5):344–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2021.1995748

- Cumming, Geoff. 2009. “Inference by Eye: Reading the Overlap of Independent Confidence Intervals.” Statistics in Medicine 28 (2):205–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.3471

- Dahle, Dag Yngve, and Arild Wæraas. 2020. “Silence from the Brands: Message Control, Brand Ambassadorship, and the Public Interest.” International Journal of Organization Theory & Behavior 23 (3):259–80. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOTB-05-2019-0060

- Dahle, Dag Yngve. 2020. “Marks of Distinction: Branding Responses to Market Logics in Schools.” Working Paper 6/2020, Norwegian University of Life Sciences, Aas, Norway.

- Dahle, Dag Yngve. 2021. “Brand on the Run?: Marketization, Market Position, and Branding in Upper Secondary Schools.” In Public Branding and Marketing: A Global Viewpoint, edited by Staci Zavattaro, 175–96. New York, NY: Springer Nature.

- Dahle, Dag Yngve. 2022. “Magic Muzzles? The Silencing of Teachers through HRM, Performance Appraisal and Reputation Concern.” International Journal of Public Sector Management 35 (2):172–94. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPSM-02-2021-0048

- De Chernatony, Leslie. 1999. “Brand Management through Narrowing the Gap between Brand Identity and Brand Reputation.” Journal of Marketing Management 15 (1–3):157–79. https://doi.org/10.1362/026725799784870432

- DiMaggio, Paul. 1979. “Review Essay: On Pierre Bourdieu.” American Journal of Sociology 84 (6):1460–74. https://doi.org/10.1086/226948

- Durand, Rodolphe, and Patricia H. Thornton. 2018. “Categorizing Institutional Logics, Institutionalizing Categories: A Review of Two Literatures.” Academy of Management Annals 12 (2):631–58. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2016.0089

- Dyne, Linn Van, Soon Ang, and Isabel C. Botero. 2003. “Conceptualizing Employee Silence and Employee Voice as Multidimensional Constructs.” Journal of Management Studies 40 (6):1359–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6486.00384

- Eisenhardt, Kathleen M., and Behnam N. Tabrizi. 1995. “Accelerating Adaptive Processes: Product Innovation in the Global Computer Industry.” Administrative Science Quarterly 40 (1):84–110. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393701

- Ertimur, Burçak, and Gokcen Coskuner-Balli. 2015. “Navigating the Institutional Logics of Markets: Implications for Strategic Brand Management.” Journal of Marketing 79 (2):40–61. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.13.0218

- Fredriksson, Magnus, and Josef Pallas. 2016. “Diverging Principles for Strategic Communication in Government Agencies.” International Journal of Strategic Communication 10 (3):153–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2016.1176571

- Friedland, Roger, and Robert R. Alford. 1991. “Bringing Society Back in: Symbols, Practices, and Institutional Contradictions.” In The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis, edited by P. J. DiMaggio and W. W. Powell, 232–67. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Gierlich-Joas, Maren, Thomas Hess, and Rahild Neuburger. 2020. “More Self-Organization, More Control—Or Even Both? Inverse Transparency as a Digital Leadership Concept.” Business Research 13 (3):921–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40685-020-00130-0

- Giles, William F., and Kevin W. Mossholder. 1990. “Employee Reactions to Contextual and Session Components of Performance Appraisal.” Journal of Applied Psychology 75 (4):371–7. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.75.4.371

- Graen, George B., and Mary Uhl-Bien. 1995. “Relationship-Based Approach to Leadership: Development of Leader-Member Exchange (LMX) Theory of Leadership over 25 Years: Applying a Multi-Level Multi-Domain Perspective.” The Leadership Quarterly 6 (2):219–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/1048-9843(95)90036-5

- Haandrikman, Karen, Rafael Costa, Bo Malmberg, Adrian Farner Rogne, and Bart Sleutjes. 2023. “Socio-Economic Segregation in European Cities. A Comparative Study of Brussels, Copenhagen, Amsterdam, Oslo and Stockholm.” Urban Geography 44 (1):1–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2021.1959778

- Hair, J. F., B. Black, B. Babin, and R. E. Anderson. 2010. Multivariate Data Analysis. 7th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

- Harris, Fiona, and Leslie de Chernatony. 2001. “Corporate Branding and Corporate Brand Performance.” European Journal of Marketing 35 (3/4):441–56. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090560110382101

- Hattke, Fabian, Rick Vogel, and Hendrik Woiwode. 2016. “When Professional and Organizational Logics Collide: Balancing Invisible and Visible Colleges in Institutional Complexity.” In Multi-Level Governance in Universities: Strategy, Structure, Control, edited by Jetta Frost, Fabian Hattke, and Markus Reilhen, 235–56. Cham: Springer.

- Haugen, Cecilie Rønning. 2020. “Teachers’ Experiences of School Choice from ‘Marginalised’ and ‘Privileged’ Public Schools in Oslo.” Journal of Education Policy 35 (1):68–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2019.1587519

- Haugen, Cecilie Rønning. 2021. “Accountability Measures in Oslo’s Public Schools. Standardising Curriculum, Pedagogy and Inequality?” Utbildning & Demokrati–Tidskrift För Didaktik Och Utbildningspolitk 30 (2):29–57.

- Henningsson, Malin, and Lars Geschwind. 2022. “Recruitment of Academic Staff: An Institutional Logics Perspective.” Higher Education Quarterly 76 (1):48–62. https://doi.org/10.1111/hequ.12367

- Hirschman, Albert O. 1970. Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Hovdenak, Sylvi Stenersen, and Janicke Heldal Stray. 2015. Hva skjer med skolen?: en kunnskapssosiologisk analyse av norsk utdanningspolitikk fra 1990-tallet og frem til i dag [What Is Happening with the School? A Sociological Analysis of Knowledge in Norwegian Educational Policies from the 1990s and to the Present]. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget.

- Imsen, Gunn, Ulf Blossing, and Lejf Moos. 2017. “Reshaping the Nordic Education Model in an Era of Efficiency. Changes in the Comprehensive School Project in Denmark, Norway, and Sweden since the Millennium.” Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 61 (5):568–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2016.1172502

- Ind, Nicholas. 2001. Living the Brand: how to Transform Every Member of Your Organization into a Brand Champion. London: Kogan Page.

- Ingstrup, Mads Bruun, Leena Aarikka-Stenroos, and Nillo Adlin. 2021. “When Institutional Logics Meet: Alignment and Misalignment in Collaboration between Academia and Practitioners.” Industrial Marketing Management 92:267–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2020.01.004

- Jada, Umamaheswara Rao, and Susmita Mukhopadhyay. 2019. “Empowering Leadership and LMX as the Mediators between Leader’s Personality Traits and Constructive Voice Behavior.” International Journal of Organizational Analysis 27 (1):74–93. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOA-09-2017-1232

- Javed, Muzhar, Muhammad Amir Rashid, Ghulam Hussain, and Hafiz Yasir Ali. 2020. “The Effects of Corporate Social Responsibility on Corporate Reputation and Firm Financial Performance: Moderating Role of Responsible Leadership.” Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 27 (3):1395–409. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1892

- Jiang, Jianwu, Wanling Ding, Rong Wang, and Saisai Li. 2022. “Inclusive Leadership and Employees’ Voice Behavior: A Moderated Mediation Model.” Current Psychology 41 (9):6395–405. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01139-8

- Kaiser, Henry F. 1974. “An Index of Factorial Simplicity.” Psychometrika 39 (1):31–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02291575

- Katou, Anastasia A., and Pawan S. Budhwar. 2006. “Human Resource Management Systems and Organizational Performance: A Test of a Mediating Model in the Greek Manufacturing Context.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management 17 (7):1223–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190600756525

- Kintana, Martin Larraza, Ainhoa Urtasun Alonso, and Carmen García Olaverri. 2006. “High-Performance Work Systems and Firms’ Operational Performance: The Moderating Role of Technology.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management 17 (1):70–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190500366466

- Kline, Rex B. 2015. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. New York, NY: Guilford Publications.

- Krejsler, John Benedicto, and Lejf Moos. 2021. “Danish–and Nordic–School Policy: Its Anglo-American Connections and Influences.” In What Works in Nordic School Policies? Mapping Approaches to Evidence, Social Technologies and Transnational Influences, edited by John Benedicto Krejsler and Lejf Moos, 129–151. Cham: Springer.

- Kuvaas, Bård, and Anders Dysvik. 2016. Lønnsomhet gjennom menneskelige ressurser: evidensbasert HRM. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget.

- Lee, Trevor Tsz-lok, Paula Kwan, and Benjamin Yuet Man Li. 2020. “Neoliberal Challenges in Context: A Case of Hong Kong.” International Journal of Educational Management 34 (4):641–52.

- Lei, Pui‐Wa, and Qiong Wu. 2007. “Introduction to Structural Equation Modeling: Issues and Practical Considerations.” Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice 26 (3):33–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-3992.2007.00099.x

- Lepak, David P., and Scott A. Snell. 2002. “Examining the Human Resource Architecture: The Relationships among Human Capital, Employment, and Human Resource Configurations.” Journal of Management 28 (4):517–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920630202800403

- Liang, Jian, Crystal I. C. Farh, and Jiing-Lih Farh. 2012. “Psychological Antecedents of Promotive and Prohibitive Voice: A Two-Wave Examination.” Academy of Management Journal 55 (1):71–92. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.0176

- Liang, Jian, Rui Shu, and Crystal I. C. Farh. 2019. “Differential Implications of Team Member Promotive and Prohibitive Voice on Innovation Performance in Research and Development Project Teams: A Dialectic Perspective.” Journal of Organizational Behavior 40 (1):91–104. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2325

- Ljunggren, Jørn, and Patrick Lie Andersen. 2015. “Vertical and Horizontal Segregation: Spatial Class Divisions in Oslo, 1970–2003.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 39 (2):305–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12167

- MacKenzie, Scott B., and Philip M. Podsakoff. 2012. “Common Method Bias in Marketing: Causes, Mechanisms, and Procedural Remedies.” Journal of Retailing 88 (4):542–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2012.08.001

- MacKinnon, D. P. 2008. Introduction to Statistical Mediation Analysis. New York, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Malkenes, Simon. 2014. Bak fasaden i Osloskolen [Behind the Facade of ‘The Oslo School’]. Oslo: Res Publica.

- Maor, Moshe, Sharon Gilad, and Pazit Ben-Nun Bloom. 2013. “Organizational Reputation, Regulatory Talk, and Strategic Silence.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 23 (3):581–608. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mus047

- Marchington, Mick. 2007. “Employee Voice Systems.” In The Oxford Handbook of Human Resource Management, edited by P. Boxall, J. Purcell, and P. Wright, 231–50. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Meule, Adrian. 2019. “Contemporary Understanding of Mediation Testing.” Meta-Psychology 3:1–7. https://doi.org/10.15626/MP.2018.870

- Møller, Jorunn, and Guri Skedsmo. 2013. “Modernising Education: New Public Management Reform in the Norwegian Education System.” Journal of Educational Administration and History 45 (4):336–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220620.2013.822353

- Morrison, Elizabeth W. 2011. “Employee Voice Behavior: Integration and Directions for Future Research.” Academy of Management Annals 5 (1):373–412. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520.2011.574506

- Morrison, Elizabeth W. 2014. “Employee Voice and Silence.” Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 1 (1):173–97. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091328

- Morrison, Elizabeth W. 2023. “Employee Voice and Silence: Taking Stock a Decade Later.” Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 10 (1):79–107. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-120920-054654

- Mowbray, Paula K., Adrian Wilkinson, and Herman H. M. Tse. 2015. “An Integrative Review of Employee Voice: Identifying a Common Conceptualization and Research Agenda.” International Journal of Management Reviews 17 (3):382–400. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12045

- Myhre, Hege. 2021. “From Knowledge Promotion Reform to Value Promotion Reform – Norwegian School Leaders and Teachers as Mediators for Democracy in a Time of Contradictions.” In Revisiting New Public Management and Its Effects: Experiences from a Norwegian Context, edited by Abbas Strømmen-Bakhtiar and Konstantin Timoshenko, 125–46. Münster: Waxmann.

- Ng, Thomas W. H., and Daniel C. Feldman. 2012. “Employee Voice Behavior: A Meta‐Analytic Test of the Conservation of Resources Framework.” Journal of Organizational Behavior 33 (2):216–34. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.754

- Oliver, Christine. 1991. “Strategic Responses to Institutional Processes.” The Academy of Management Review 16 (1):145–79. https://doi.org/10.2307/258610

- Pagès, Marcel. 2021. “Enacting Performance-Based Accountability in a Southern European School System: Between Administrative and Market Logics.” Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability 33 (3):535–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-021-09359-7

- Paulsen, Jan Merok, and Lejf Moos. 2020. “Discourses of School Leadership Traveling Across North European School Systems.” In Educational Leadership, Improvement and Change: Discourse and Systems in Europe, edited by Lejf Moos, Nikša Alfirević, Jurica Pavičić, Andrej Koren, and Ljiljana Najev Čačija, 155–166. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Peng, Jiamin, Xiaoyun Yang, Xinhua Guan, Lian Zhou, and Tzung-Cheng Huan. 2021. “Will Catering Employees’ Job Dissatisfaction Lead to Brand Sabotage Behavior? A Study Based on Conservation of Resources and Complexity Theories.” International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 33 (3):973–93. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-09-2020-0991

- Pietilä, Maria, and Romulo Pinheiro. 2021. “Reaching for Different Ends through Tenure Track—Institutional Logics in University Career Systems.” Higher Education 81 (6):1197–213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00606-2

- Pinheiro, Rómulo, Lars Geschwind, Hanne Foss Hansen, and Kirsi Pulkkinen. 2019. Reforms, Organizational Change and Performance in Higher Education: A Comparative account from the Nordic Countries. Cham: Springer Nature.

- Podsakoff, Philip M., Scott B. MacKenzie, Jeong-Yeon Lee, and Nathan P. Podsakoff. 2003. “Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies.” The Journal of Applied Psychology 88 (5):879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Pope, Rachael. 2019. “Organizational Silence in the NHS:‘Hear No, See No, Speak No.” Journal of Change Management 19 (1):45–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2018.1513055

- Preacher, Kristopher J., Derek D. Rucker, and Andrew F. Hayes. 2007. “Addressing Moderated Mediation Hypotheses: Theory, Methods, and Prescriptions.” Multivariate Behavioral Research 42 (1):185–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273170701341316

- Puaca, Goran. 2021. “Academic Leadership and Governance of Professional Autonomy in Swedish Higher Education.” Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 65 (5):819–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2020.1755359

- Rasmussen, Annette, and Marianne Dovemark. 2022. Governance and Choice of Upper Secondary Education in the Nordic Countries: Access and Fairness. Cham: Springer Nature.

- Røvik, Kjell Arne. 2007. Trender og translasjoner: ideer som former det 21. århundrets organisasjon. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Sağnak, Mesut. 2017. “Ethical Leadership and Teachers’ Voice Behavior: The Mediating Roles of Ethical Culture and Psychological Safety.” Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice 17 (4):1101–17.

- Selwyn, Neil. 2023. “There is a Danger We Get Too Robotic”: An Investigation of Institutional Data Logics within Secondary Schools.” Educational Review 75 (3):377–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2021.1931039

- Shields, Robin, and Richard Watermeyer. 2020. “Competing Institutional Logics in Universities in the United Kingdom: Schism in the Church of Reason.” Studies in Higher Education 45 (1):3–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1504910

- Stratton, Samuel J. 2021. “Population Research: Convenience Sampling Strategies.” Prehospital and Disaster Medicine 36 (4):373–4. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X21000649

- Strømmen-Bakhtiar, Abbas, and Konstantin Timoshenko. 2021. Revisiting New Public Management and Its Effects: Experiences from a Norwegian Context. Münster: Waxmann.

- Svendsen, Mari, Christine Unterrainer, and Thomas Faurholt Jønsson. 2018. “The Effect of Transformational Leadership and Job Autonomy on Promotive and Prohibitive Voice: A Two-Wave Study.” Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies 25 (2):171–83. https://doi.org/10.1177/1548051817750536

- Tabachnick, Barbara G., Linda S. Fidell, and Jodie B. Ullman. 2007. Using Multivariate Statistics. Vol. 5. Boston, MA: Pearson.

- Thornton, Patricia H., and William Ocasio. 1999. “Institutional Logics and the Historical Contingency of Power in Organizations: Executive Succession in the Higher Education Publishing Industry, 1958–1990.” American Journal of Sociology 105 (3):801–43. https://doi.org/10.1086/210361

- Thornton, Patricia H., William Ocasio, and Michael Lounsbury. 2012. The Institutional Logics Perspective: A New Approach to Culture, Structure and Process. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Thornton, Patricia H. 2004. Markets from Culture: Institutional Logics and Organizational Decisions in Higher Education Publishing. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Vandenberg, Robert J. 2006. “Introduction: statistical and Methodological Myths and Urban Legends: Where, Pray Tell, Did They Get This Idea?” Organizational Research Methods 9 (2):194–201. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428105285506

- Vican, Shawna, Asia Friedman, and Robin Andreasen. 2020. “Metrics, Money, and Managerialism: Faculty Experiences of Competing Logics in Higher Education.” The Journal of Higher Education 91 (1):139–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2019.1615332

- Wæraas, Arild, and Dag Yngve Dahle. 2020. “When Reputation Management Is People Management: Implications for Employee Voice.” European Management Journal 38 (2):277–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2019.08.010

- Wæraas, Arild. 2014. “Kommunal omdømmebygging som konkurransestrategi [Municipal Reputation Building as Competitive Strategy].” In En strategisk offentlig sektor [A Strategic Public Sector], edited by Åge Johnsen. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget.

- Weber, Max. 1978. Economy and Society: An Outline of Interpretive Sociology. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Wilkinson, Adrian, Jian‐Min Sun, and Paula K. Mowbray. 2020. “Employee Voice in the Asia Pacific.” Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources 58 (4):471–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/1744-7941.12274

- Xiong, Lina, Kevin Kam Fung So, Laurie Wu, and Ceridwyn King. 2019. “Speaking up Because It’s My Brand: Examining Employee Brand Psychological Ownership and Voice Behavior in Hospitality Organizations.” International Journal of Hospitality Management 83:274–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.11.006

- Zeng, Jianji, and Guangyi Xu. 2020. “Linking Ethical Leadership to Employee Voice: The Role of Trust.” Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal 48 (8):1–12. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.9200

- Zhang, Zhenzhen, Qiaozhuan Liang, and Jie Li. 2019. “Understanding Managerial Response to Employee Voice: A Social Persuasion Perspective.” International Journal of Manpower 41 (3):273–88. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-05-2018-0156

- Zhao, Xinshu, John G. Lynch Jr., and Qimei Chen. 2010. “Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and Truths about Mediation Analysis.” Journal of Consumer Research 37 (2):197–206. https://doi.org/10.1086/651257

Appendix A.

Survey instruments

High-commitment HRM (control-oriented HRM reversed) (Lepak and Snell Citation2002):

> Here, employees can routinely make changes in the way that they perform their jobs.

> Here, employees are empowered to make decisions.

> Here, employees have jobs that include a wide variety of tasks.

> Here, the recruitment/selection process focuses on their ability to contribute to our strategic objectives.

> Here, the recruitment/selection process focuses on selecting the best all-round candidate, regardless of the specific job.

> Here, the recruitment/selection process places priority on employees’ potential to learn.

> Here, training activities for employees are comprehensive.

> Here, training activities for employees are continuous.

> Here, training activities for employees strive to develop firm-specific skills/knowledge.

> Here, performance appraisals for employees are based on input from multiple sources (peers, subordinates).

> Here, performance appraisals for employees emphasize employee learning.

> Here, performance appraisals for employees focus on their contribution to our strategic objectives.

> Here, performance appraisals for employees include developmental feedback.

> Here, compensation/rewards for employees include an extensive benefits package.

> Here, compensation/rewards include employee ownership programs.

> Here, compensation/rewards for employees provide incentives for new ideas.

*

Satisfaction with the performance appraisal system (Giles and Mossholder Citation1990):

> In general, I feel the company has an excellent performance review system

> The performance review system does a good job of indicating how an employee has performed in the period covered by the review.

> The review system provides a fair and unbiased measure of the level of an employee’s performance.

*

Reputation concern (adapted from Wæraas Citation2014):

> Management is concerned about improving the organization’s reputation.

> Management thinks that the organization will benefit economically from a favorable reputation.

> According to management a good reputation will turn the organization into a more attractive employer.

> Management would like the organization to have a favorable reputation because it signals that external stakeholders trust the organization.

> In later years management has become more concerned about building a favorable reputation.

> When decisions are made it is natural to consider their consequences for the organization’s reputation.

*

Leader-member exchange (LMX) (Graen and Uhl-Bien Citation1995):

> Do you usually know how satisfied your leader is with what you do?

> How well does your leader understand your job problems and needs?

> How well does your leader recognize your potential?

> Regardless of how much formal authority your leader has built into his/her position, what are the chances that your leader would use his/her power to help you solve problems in your work?

> Regardless of the amount of formal authority your leader has, what are the chances that he/she would “bail you out” at his/her expense?

> I have enough confidence in my leader that I would defend and justify his/her decision if he/she were not present to do so?

> How would you characterize your working relationship with your leader?

*

Employee voice (Liang, Farh, and Farh Citation2012):

> I proactively develop and make suggestions for issues that may influence the unit.

> I proactively suggest new projects which are beneficial to the work unit.

> I raise suggestions to improve the unit’s working procedure.

> I proactively voice out constructive suggestions that help the unit reach its goals.

> I make constructive suggestions to improve the unit’s operation.

> I advise other colleagues against undesirable behaviors that would hamper job performance.

> I speak up honestly with problems that might cause serious loss to the work unit, even when/though dissenting opinions exist.

> I dare to voice out opinions on things that might affect efficiency in the work unit, even if that would embarrass others.

> I dare to point out problems when they appear in the unit, even if that would hamper relationships with other colleagues.

> I proactively report coordination problems in the workplace to the management.