?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This study develops an integrated model to investigate how resource-based factors interact with country-level antecedents pertaining to the regulatory quality and uncertainty avoidance in shaping venture creation. Drawing upon an institutional approach, this research examines formal and informal institutions as contingency variables on the association between entrepreneurial resources and startups. The analytical results based on 41,156 observations from 46 countries suggest that entrepreneurial startups are significantly affected by resource factors in terms of human, financial, and social capitals. The results also show that national regulatory quality and uncertainty avoidance serve as moderating factors on such decision-making. The results largely support our hypotheses and suggest significant theoretical and political implications.

Introduction

Entrepreneurship is broadly associated with economic growth (Estrin, Korosteleva, and Mickiewicz Citation2013). The increasing importance of entrepreneurship has been acknowledged by both researchers and practitioners (Aragon-Mendoza, del Val, and Roig-Dobón Citation2016; Hitt, Haynes, and Serpa Citation2010; Li Citation2020; Citation2023). In fact, Audretsch and Thurik (Citation2001) emphasized a fundamental policy and institutional shift from the 20th century’s managed economy to a 21st century entrepreneurial economy. Despite the significance of the entrepreneurial economy, more recent empirical work shows that the rate of entrepreneurial startups, which act as the foundation for contemporary economies, has decreased over the last 15 years in advanced economies. However, in emerging countries, domestic entrepreneurial activity appears to be growing (Li Citation2023). The heterogeneous entrepreneurial rates across countries suggest the need for additional in-depth studies to develop a more nuanced understanding of the important antecedents for entrepreneurship.

In recent years, the resource-based view (RBV) has become a primary research paradigm that is guiding inquiries into the determining factors of entrepreneurship. Extant studies have looked at the influences of individual-level resource antecedents on entrepreneurship, such as financial capital (Linder, Lechner, and Pelzel Citation2020), human capital (Sahasranamam and Nandakumar Citation2020), and social capital (Neumeyer et al. Citation2019). These existing studies have found that resource-based factors are an essential element of entrepreneurship. However, what is less studied in extant literature is how resource-based factors might influence individuals’ choice of entrepreneurship differently within varying institutional contexts. Past research has acknowledged that theoretical and empirical investigations focusing exclusively on a single level of analysis of resources is liable to produce an incomplete understanding of entrepreneurial startups (Boudreaux and Nikolaev Citation2019). In response, this research seeks to develop a multi-level framework that investigates how country-level institutional environments might be instrumental in unlocking individual-level resource-based factors.

There is bountiful empirical research suggesting that macro-level antecedents such as institutional environment can alter entrepreneurial behavior (Simón-Moya, Revuelto-Taboada, and Guerrero Citation2014; Thai and Turkina Citation2014). National institutional environments are one of the most extensively researched institutional dimensions and act as the elements of the “profound structure” of institutional differences (Uriarte, Espinoza-Benavides, and Ribeiro-Soriano Citation2023). Within the entrepreneurial domain, it appears that country-level institutional differences give rise to distinct levels of entrepreneurial activity across nations. For example, early research by Baumol (Citation1990) revealed that institutions generate the macro-structure of motivations that affect individuals’ choice of entrepreneurship over wage employment. Similarly, drawing on a national institutional profile, Castaño, Méndez, and Galindo (Citation2015) and Simón-Moya, Revuelto-Taboada, and Guerrero (Citation2014) reveal that institutional profiles play distinct roles in promoting entrepreneurship across countries. By developing and validating a measure of national institutional profiles, Chowdhury, Audretsch, and Belitski (Citation2019) identified that institutional differences lead to variations in new business activities.

Institutions can be formal and informal (North Citation1990). Entrepreneurial environments are often defined by formal institutions comprising legal, political and economic structures. However, formal institutions do not adequately explain differences in entrepreneurship and there is a need to consider informal institutions such as culture, underlying norms, and codes of conduct that collectively affect entrepreneurial activities (Brinkerink and Rondi Citation2021). While acknowledging individual-level antecedents and institutional environments contribute to better understanding entrepreneurship, very few studies have considered how resource-based factors, and formal and informal institutions jointly affect entrepreneurial startups in a single framework. Therefore, this research considers the effects of interaction between formal and informal institutions among resourceful entrepreneurs in both emerging and developed economies.

The regulatory quality provides the formal legal foundation for economic exchanges through entrepreneurial activities. The existing literature, however, has not unpacked cross-country differences in formal institutions in terms of how the regulatory quality can potentially modify individuals’ choices when it comes to entrepreneurship entry. This gap in the literature provides an opportunity for further inquiry, because like economic freedom and corruption, the existence of the regulatory quality is also an institutional measure that can be applied across countries. Contributing to the emerging studies on the significant role of formal institutional environments in the aforementioned relationship, this paper aims to understand: How do differences in the strength of the regulatory quality across countries, on the one hand, and micro-level resources, on the other hand, operate as interacting determinants that influence entrepreneurial startups?

In parallel, recent literature has contended that informal institutions can alter entrepreneurial behavior (Calza, Cannavale, and Nadali Citation2020). In that, uncertainty avoidance serves as one of the cultural elements of the profound structure within informal institutions across countries. However, it has received much less attention than other cultural dimensions, such as individualism-collectivism, in the literature (Canestrino et al. Citation2020). Uncertainty avoidance is defined as “the extent to which the members of a culture feel threatened by uncertain or unknown situations” (Hofstede Citation1991, 113). Entrepreneurial startups embrace a step into the unknown, away from the stable employment situation (Costa, Caetano, and Santos Citation2016). If individuals start the entrepreneurial ventures, the potential legitimacy cost of entrepreneurial entry increases in the countries in which societal uncertainty avoidance is high. Under such environment, the impact of formal institutional environments on the association between resources and entrepreneurship could be bounded. This research advances a three-way interaction hypothesis in that the moderating effects of regulatory quality on the entrepreneurial resources and startup relationship as posited as contingent on the cultural practice of uncertainty avoidance. Therefore, it further questions: How does national culture, i.e. the extent to which individuals feel threatened in ambiguous situations affects in countries affect entrepreneurial startups and how do differences in the degree of national uncertainty avoidance provide boundary conditions for the moderating role of regulatory quality on such a relationship?

Drawing upon a sample of 41,156 individuals from 46 countries included in the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor–Adult Population Survey (GEM–APS), along with institutional environment data taken from the Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) dataset and Hofestede Cultural Index (HCI) dataset, the results provide support to the theoretical framework and research hypotheses, offering new insights both for scholars and for policymakers.

This research makes theoretical and empirical contributions to the extant literature. First, this research contributes to the institutional avenue of research by responding to a recent call for empirical work that considers the combined effects of formal and informal institutions (Brinkerink and Rondi Citation2021; Li et al. Citation2022). In line with studies that focus on various institutions in explaining entrepreneurial behavior (e.g. Ljunge and Stenkula Citation2021; Sahasranamam and Nandakumar Citation2020; Urbano, Aparicio, and Audretsch Citation2019), this research investigates how regulatory quality and uncertainty avoidance provide boundary conditions on the association between resource-based factors and startups across countries. The examination of formal institutions reveals how the relative strength of a country’s commitment to the regulatory quality manages resource allocation by forming shared expectations and economic rewards vis-à-vis entrepreneurial outcomes. The examination of informal institutions captures that uncertain institutions lead to differences in terms of how individuals recognize entrepreneurial opportunities and threats within socio-economic environments and how they react to them through the utilization of resources.

Second, this research synthesizes ideas from the literature on resource-based View (RBV) (Barney Citation1991) and institutional approaches to economics (North Citation1990; Williamson Citation2000) to develop an integrated model (Martínez-Fierro, Biedma-Ferrer, and Ruiz-Navarro Citation2019). It takes an important step in the literature by bringing these two levels of development together and extending the extant research. It suggests that cross-level analysis involves acknowledging that there is a specific individual-environment relationship, and that the impact of resource-based antecedents on starting new businesses cannot be fully captured if the entrepreneurs and/or the institutional environments are treated as separate entities. It creates an integrated framework model for examining how resource-based antecedents might interact with formal and informal institutional contexts, and thus to explain the heterogeneous entrepreneurial rates in different countries.

Third, RBV has been criticized for its limited ability to establish appropriate contexts (Li Citation2018). RBV can be complemented by introducing the macro environment perspectives to comprehensively assess the mechanisms of institutions that are required to release the potential of resources. RBV and institutional views diverge substantially their focus—one is moving toward a more individual-level analysis and the other is reinforcing the importance of macro-level institutional factors in driving entrepreneurial startups. This study argues that introducing a form of RBV that is also receptive to the ideas of macro theories such as institutional theory will advance both theoretical and empirical knowledge of what drives entrepreneurial startups.

Conceptual framework and hypotheses development

An institutional approach

The environment in which entrepreneurial startups take place plays an important role in understanding how entrepreneurship originates (Dutta and Sobel Citation2021). The institutional approach explains entrepreneurial behavior as individuals’ responses to the supports and constraints of institutional contexts (Abdul, Kelley Donna, and Jonathan Citation2020). Institutional environments influence the nature of business opportunities and individuals who recognize and exploit these opportunities around them.

Institutions contain legal, political, social, economic and cultural structures that underlie entrepreneurial activities (Abdul, Kelley Donna, and Jonathan Citation2020; Liñán and Fernandez-Serrano Citation2014). Country-level institutions can be formal, with regard to regulations, policies, and laws that regulate entrepreneurial activities, and informal, in terms of norms, values, and cultures that encompass socially acceptable behavior (Papageorgiadis et al. Citation2021). The extant literature emphasizes exploring formal and informal institutional effects in order to reveal their significance to entrepreneurial activities (Webb, Khoury, and Hitt Citation2020). Recent studies revealed crucial characteristics of formal institutions fundamental for venture creation, economic performance, and the legislation of business activities (e.g. Boudreaux and Nikolaev Citation2019; Lee et al. Citation2022; Sahasranamam and Nandakumar Citation2020; Uriarte, Espinoza-Benavides, and Ribeiro-Soriano Citation2023). A more developed formal institutional environment reduces uncertainties and promotes entrepreneurial efforts necessary to start a new venture (Ferreira et al. Citation2023). Informal institutions are socially accepted norms of behavior and are derived from mutual exchanges among individuals (Chan and Du Citation2022). Based on these interactions, social norms and values, which reflect applied standards of conduct, can enter into effect and start to restrict individuals’ behavior.

Formal and informal institutions contribute to establishing an equilibrium in the economy (Gimenez-Jimenez, Calabrò, and Urbano Citation2020). Williamson’s (Citation2000) institutional theory proposes the “embeddedness” of informal institutions in society, which is intertwined with formal institutions and jointly define the “rule of game.” Formal and informal institutions might interact in two different ways, with informal institutions either complementing or substituting for formal ones (Webb, Khoury, and Hitt Citation2020). Informal institutions are complementary if they generate incentives, and in turn, solve problems of social interaction and increase the efficiency of formal institutions. On the other hand, informal institutions might undermine formal institutions when incentives are provided in a way that it is incompatible with the latter, which are weakened or not enforced. Significantly, Williams and Vorley (Citation2015) found that while reforms to formal institutions foster entrepreneurship, if they are not congruent with informal institutions, economic development is not positively influenced.

Moreover, entrepreneurial startups require resources, such as human, financial, and social capitals (Linder, Lechner, and Pelzel Citation2020; Neumeyer et al. Citation2019; Sahasranamam and Nandakumar Citation2020). Individual access to and ownership of resources informs the intention of people to start new businesses. Despite a general assumption that differences in institutional contexts explain heterogeneity in entrepreneurship, how the interaction between formal and informal institutions affects the resource-entrepreneurship relationship remains largely unexplored. While resource endowment matters, the allocation of resources to the pursuit of venture creation cannot be viewed from the standpoint of formal and informal institutional contexts as isolated units. To address this literature gap, this research employs multilevel models that take the role of resources, as well as the boundary conditions jointly shaped by formal and informal institutions, into account. It develops a nuanced understanding of the effects of resource endowments for venture creation that is theoretically and empirically lacking in extant work.

Resource-based view in entrepreneurship

In line with Barney (Citation1991), new ventures possess specific resources that shape their “competitive” or “monopolistic” advantages. The RBV provides a conceptual framework in which “resource” is conceived of as “anything that can be thought of as a strength or a weakness of the firm” (Wernerfelt Citation1984:172) and variables can be anchored. In line with early studies (e.g. Barney Citation1991; De Clercq, Lim and Oh Citation2013) and based on RBV, this paper adopts measure of resources as the aggregation of financial, human, and social capital resources.

Financial capital serves an important role in venture creation, especially fulfilling the need for initial cash flow. Extant research shows that resource constraints of financial capital became a primary factor prohibiting entrepreneurial startups (Bischoff, Gielnik, and Frese Citation2020). Entrepreneurs typically lack legitimacy, collateral, and credibility. They thus find it difficult to secure financial backing from external bodies such as venture capitalists, bank, and informal investors. Venâncio and Jorge (Citation2022) found financial capital determines the survival and growth of a startup. Firms with larger financial assets are more likely to start on a larger scale, overcome managerial mistakes and temporary hardships, and obtain better resources. The choice of funding can also diminish information asymmetries by signaling the value of the startup to external entities and investors.

Human capital refers to the knowledge and skills that an individual has accumulated over time, which are heterogeneously distributed (Sahasranamam and Nandakumar Citation2020). People are more likely to form entrepreneurial when they believe themselves to have knowledge and skills relevant to entrepreneurship. Jafari-Sadeghi, Kimiagari, and Biancone (Citation2020) asserted that greater levels of educational attainment assists individuals in accumulating explicit knowledge, receiving profitable opportunities, and engaging in entrepreneurial activities. Skills and knowledge, in the form of human capital, contribute to greater foresight competencies. Through formal education, individuals obtain fundamental abilities to understand technology and markets, and better recognize opportunities surrounding them.

Social capital is a resource that people derive from social structures (Neumeyer et al. Citation2019). It explains social interactions in the entrepreneurial process at multiple levels. The exposure to entrepreneurial role models enhances self-efficacy, reduces uncertainty that surround venture creation, and provides a source of emotional support (Manolova et al. Citation2007). Therefore, taking these arguments together, it will be posited:

Hypothesis 1: Resource-based factors are positively related to entrepreneurial start-ups.

Regulatory quality

The literature has recognized the significance of institutional environments as a determinant of entrepreneurial behavior (Pacheco et al. Citation2010), with empirical studies focusing on particular institutional dimensions like institutional development (Wu and Chen Citation2014), property rights and regulatory frameworks (Uddin et al. Citation2019), and economic freedom (Boudreaux, Nikolaev, and Klein Citation2019). Despite the recognition that commitment to the regulatory quality represents a more comprehensive measure for delineating the legal and political conditions of a country (Yang Citation2023), the impact of cross-country differences with respect to the regulatory quality on entrepreneurial startups has been under-theorized.

The regulatory quality embodies the overarching public policies and institutions that form a framework for economic, social, and legal relations (Radaelli and De Francesco Citation2007). It defines a country’s investment environment, and has a profound impact on the benefits and costs of becoming an entrepreneur. A stronger commitment to the regulatory quality contributes to the more effective market functioning, thereby decreasing transaction costs for economic exchanges in entrepreneurial activities (North Citation1990). Consequently, holding the impact of individual differences constant, a strong commitment to the regulatory quality should promote the expected return of entrepreneurship, given the benefit arising from low-cost business environments. For instance, China’s rise in the past 40 years can be largely attributed to the unleashing of the Chinese people’s spirit of entrepreneurialism (Redding Citation1993). This increased entrepreneurial spirit can be linked, in turn, to significant improvements in the regulatory quality; these improvements have reduced the costs of doing business substantially, and thereby increased the benefits of becoming self-employed.

By contrast, in the former Soviet Union, where legal protections are weak, capital investment via entrepreneurship entry is much lower than in countries in which the rewards of entrepreneurial activities are protected more effectively (Aidis, Estrin, and Mickiewicz Citation2008). Thus, whereas the substantially improved regulatory quality has led to increased expected return and reduced switching costs of becoming an entrepreneur in China, the weak regulatory quality has contributed to the lack of entrepreneurship in the former Soviet Union.

Recent studies have acknowledged that entrepreneurship is a multi-level phenomenon (Yang, Li, and Wang Citation2020), and that rewards accruing to an individual’s assembly and mobilization of resources are sensitive to formal institutional contexts (Estrin, Mickiewicz, and Stephan Citation2016). New institutional economics (NIE) posits that the relative strength of a country’s commitment to the regulatory quality regulates resource allocation by shaping shared expectations and economic rewards vis-à-vis entrepreneurial outcomes (Williamson Citation2000). Moreover, an important function of formal institutions is to diminish cognitive uncertainty by constructing socially rationalized rules for business exchanges (Scott Citation1995). A stronger commitment to the regulatory quality provides macro environments that enhance people’s mental schemas, and thus capture market opportunities better. It can also nurture entrepreneurial opportunities by fostering the development of factor inputs and regulatory resources (McGahan and Victer Citation2010).

In countries where institutional environments are less deficient, individuals might anticipate fewer impediments and uncertainty to open a business, thereby influcing the extent to which entrepreneurs value firms’ resources and release the forces of resources. For instance, Kirca et al. (Citation2011) argue that well-developed institutions produce strong national economies that can provide entrepreneurs with support to develop tangible and intangible resources for achieving competitive advantages in their business operations. Similarly the study by Chen et al. (Citation1998) on business founders and non-business founders suggests that supportive institutions increase the opportunity discovery and exploitation among business owners, which might further facilitate their venture creation and growth, because business founders assess their resources and capabilities more favorably in regard to perceived opportunities and conditions in the market. By contrast, a weak commitment to the regulatory quality will result in an uncertain environment, which undermines perceived opportunities for starting businesses (Manolova, Eunni, and Gyoshev Citation2008). Such an environment will weaken the positive impact of resource-based factors on entrepreneurship. Taking these arguments together, it posits:

Hypothesis 2: Regulatory quality is positively related to entrepreneurial start-ups.

Hypothesis 3: Regulatory quality moderates the relationship between resource-based factors and entrepreneurial start-ups, in that the positive relationship is strengthened when the regulatory quality is stronger.

Uncertainty avoidance

Uncertainty avoidance is defined as the extent to which individuals’ intention to avoid situation of risk (Hofstede Citation1991). Individuals from countries with cultures characterized by high uncertainty avoidance are more risk averse and tend to have greater fear of failure and a lower tolerance for ambiguity (Canestrino et al. Citation2020). They tend to consider entrepreneurship as more of a risk than an opportunity. As a result, individuals consider starting a business as demanding and troublesome and become more sensitive to the risks and costs involved in entrepreneurship. Thus, it posits that high uncertainty avoidance in a given country constitutes a major impediment to individuals deciding to become entrepreneurs.

The previous section has suggested that a stronger commitment to the regulatory quality leads to an environment that enables individuals to capture and utilize market resources and capabilities better. Nonetheless, recent research found that the impact of same formal institution on entrepreneurship might vary across countries within different cultural environments (Fuentelsaz, González, and Maicas Citation2019). This can be at least partially due to the fact that formal and informal institutions coexist and their interdependences need to be taken into account for the correct interpretation of their impacts. The impact of formal institutional environments might be subordinated to informal ones in that formal institutions are the means used to establish the interactions of the society according to the norms and cultural values that the informal institutions represent.

A stronger commitment to the regulatory quality leads to greater availability of entrepreneurial opportunities in countries. An institutional environment in which entrepreneurs could recognize their own latent opportunity motivation could offer entrepreneurs an auto-system that enables them to control their own resources in their entrepreneurial behavior. Uncertainty avoidance reflects the differences in how people recognize such entrepreneurial opportunities and threats within certain institutional environment and how people react to them. In countries where uncertainty avoidance is high, there will be less tolerance of risk and ambiguity. Consequently, individuals will become less responsive to incentives provided by a strong regulatory quality and tend to be more concentrated on activities with less uncertain outcomes such as wage-employment. Therefore, we expect that uncertainty avoidance weakens the positive impact of regulatory quality on individuals’ utilization of resources and inhibits the social desirability of entrepreneurship.

Hypothesis 4: Uncertainty avoidance is negatively related to entrepreneurial start-ups.

Hypothesis 5: The moderating effect of regulatory quality on the relationship between resource-based factors and entrepreneurial start-ups will be weaker when the national uncertainty avoidance is higher.

Method

Data and sample description

The dataset is constructed by merging main variables adopted from the GEM-APS with country-level variables associated with the regulatory quality and uncertainty avoidance; these latter variables were adopted from Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) and Hofestede Cultural Index (HCI). Operated by the Global Entrepreneurship Research Association (GERA) since 1998, GEM continuously collects country-level data alongside individual-level data; these data capture the determinants and incidence of entrepreneurship in participating countries. Matching datasets from GEM-APS, WGI, and HCI, this research selected individuals in the GEM-2015 survey who were wage-employed in full-time work, excluding those who responded that they were employed in the voluntary sector. The sample includes 41,156 individuals from 46 countries.

Dependent variable

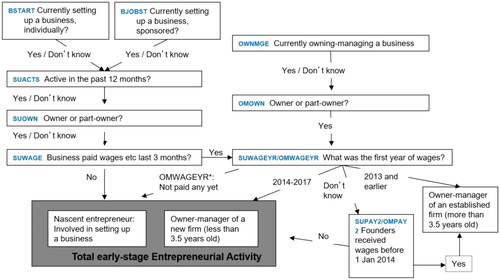

Adopting prior measurement approach from Stenholm, Acs, and Wuebker (Citation2013) and Urbano and Alvarez (Citation2014), entrepreneurial startups is captured by total entrepreneurial activity (TEA). TEA is a widely accepted entrepreneurial startup indicator, conceptualizing entrepreneurs as someone actively involved in starting a new firm (nascent entrepreneur) or owning and managing an operating business up to 3.5 years old (business owner). illustrates the detailed generation of TEA index across participating countries.

Independent variables

Following prior research (De Clercq, Lim, and Oh Citation2013), the resource-based factor was measured using GEM-APS, which includes three questions in relation to the financial capital, human capital, and social capital resources. In line with Autio and Acs (Citation2010), financial capital was measured by asking if individuals belong to the lower, middle, or higher tier of household income in the countries. Human capital assesses if respondents have indicated that they had skills, knowledge and experience required for entrepreneurial startups (De Clercq and Arenius Citation2006). Social capital was captured by assessing whether the respondents personally knew someone who had experience of venture creation in the past (Klyver and Hindle Citation2007). To build a composite measure, we re-centred these variables to range from “0” to “1” and took their sum to create a single overall proxy of resource-based index scaled from “0” to “3.” In WGI, the regulatory quality index (RQI) captures the extent to which the perceptions of the ability of the government to formulate and implement sound policies and regulations. The World Bank developed this index by aggregating individual variables from different data sources. Appendix A lists the individual variables from each data source used to construct this measure in the WGI. Uncertainty avoidance index (UAI) is collected from Hofstede’s well-known study of cultural dimensions across countries. This study was first published in 1980, and the newest edition published in 2015 provides more information on cross-validation and stability of the data. Since this study was comprised of multiple data sources, the measures of RQI and UAI were established in those countries that consistently appeared in the GEM-APS, WGI, and HCI in the year of 2015.

Control variables

A set of micro-level controls are included in the empirical model to alleviate omitted variables bias. Previous research suggests young people tend to be self-employed, but this association is non-linear (Parker Citation2004). This paper includes age and its quadratic term to verify this non-linear relationship. Gender is included in the models, given that existing studies have identified gender-based differences in decisions about becoming entrepreneurs (Volodina and Nagy Citation2016). Individuals’ education have likewise been shown to be related to entrepreneurial decisions (Muralidharan and Pathak Citation2016), it thus includes respondents’ educational attainments. In addition, at the country-level, prior research suggests that levels of national socio-economic development drive the distribution of entrepreneurship (Stel, Carree, and Thurik Citation2005). This paper, therefore, includes controls for countries’ Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita at purchasing power parity (PPP) and the natural logarithm of a country’s total population. details the measures and definitions of the studied variables.

Table 1. Description of model variables.

Model specification

Because the data has a hierarchical nature—individual observations are nested in countries—this research performs a multilevel analytical approach. Employing a multilevel modeling technique allows us to deal with unobserved heterogeneity within a cross-country and cross-individual dataset. There are several reasons for performing multilevel models over pooled regression models.

First, disregarding the interdependency between individual-level and country-level characteristics leads to bias in the coefficients and standard errors (Snijders and Bsoker 2012), because observations within countries are correlated. Multilevel approaches offer a framework that deals with the hierarchical nature of the data, thus correcting bias in the estimated parameters resulting from country clustering. Second, multilevel techniques generate systematic estimates of the effects across levels, as well as cross-level interaction effects (Echambadi, Campbell, and Agarwal Citation2006). In this research, the fixed effects capture the impact of individual and country-level antecedents. The application of random effects examines country-level variance by allowing the intercept and slope to vary across countries.

The model has a binary dependent variable, Yij, constructed from the dataset that captures an individual’s intention to start a new business, where

is an unobservable latent variable that represents the probability of individual i in country j starting a new business. The causal relationship is determined by the following linear model:

The parameter represents the intercept of individuals who are nested in the countries.

and

are the slopes to be estimated.

is the error term.

In the multilevel regression models, and

are treated as random variables, which allows them to be modeled as outcome variables that are regressed on institutional variables and control variables at the country level.

and

are estimated intercept and slope that vary at country level.

and

are country-level effects. The overall model is as follows:

Analysis and results

presents correlation matrix. provide the estimates for the effects of micro-level, macro-level, and cross-level predictors on the dependent variable. Empirical models provide estimates for the fixed effects (i.e. coefficient estimates) and random effects (i.e. variance estimates) with model fit statistics. In line with Bettis et al. (Citation2016), the hypothesis testing should not be simply based on a specific threshold of p-value. Therefore, standard errors are reported. In addition, estimates are interpreted using odds ratios (OR) in order to obtain the effect size estimates that provide information in regard to the direction and magnitude of the relationship between two variables. If the ratio is greater than one, this suggests a positive association, whereas ratio less than one implies a negative relationship. In order to obtain power calculations, the Akaike information criterion (AIC), the Bayesian information criterion (BIC), and the log-likelihood are reported in each model. The likelihood ratio test is also performed and presented in order to reveal the goodness of model fit.

Table 2. Correlation matrix.

Table 3. Multilevel logistic regression analysis results.

Table 4. Multilevel logistic regression analysis results.

Table 5. Multilevel logistic regression analysis results.

Null model

Given that the country-level heterogeneity in the empirical model requires a multi-level approach; this approach yields an intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) of 19.77% for the entrepreneurship (Model 1), which captures the proportion of variance in entrepreneurial startups that can be found among countries owing to country-level factors. This model is used as the “null model” and observes significant variance at higher level. Model 1 implies significant variance therefore demanding a multi-level approach that captures the variance of country-level predictors on outcome variable.

Baseline model

In Model 2, the fixed effect estimates suggest that demographic factors exert significant impacts. For instance, male employees are more likely than female employees to select entrepreneurship (β = 0.418, OR = 1.518, p < 0.001). The degree of educational attainment is significantly related to entrepreneurial startups (β = 0.051, odds ratio = 1.051, p < 0.001). The GDP and national population are macro indicators of entrepreneurial expectations, and appear to affect entrepreneurship significantly (β = 0.642, OR = 1.900, p < 0.1; β = 0.176, OR = 1.192, p < 0.1). Turning to the random effects, there is a reduction from Model 1 to Model 2 in the variance component of random intercept, implying the inclusion of control variables explains 23.45% ((0.81–0.62)/0.81) of the country-level variance. The resource-based factor is significantly and positively related to entrepreneurial startups (β = 0.264, OR = 1.302, p < 0.001), therefore supporting H1.

Adding country-level regulatory quality and the Cross-level interaction term

The country-level predictor, regulatory quality, is entered in Model 3. The estimate effects of control variables in Model 3 are consistent with Model 2, when the impact of country-level predictor is controlled. In comparing the base model and Model 3, the inclusion of the country-level predictor explains more variance, explaining an additional 10.61% (((0.66–0.59)/0.66))*100) of the country-level variance in the outcome variable. The regulatory quality appears to significantly and positively affect entrepreneurship (β = 0.336, OR = 1.399, p < 0.05), supporting the hypothesis that a stronger legal system creates a more favorable business environment in which individuals have more incentives to explore entrepreneurial opportunities. Hypothesis 2 is thus supported.

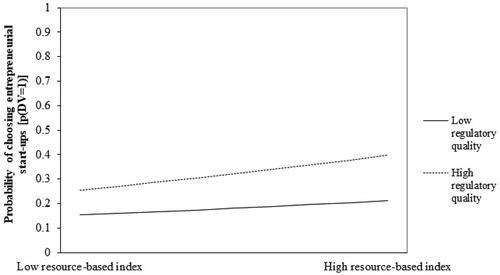

The interaction term between entrepreneurial resource and country-level difference regarding commitment to the regulatory quality is tested in Model 4. The analytical results confirm the hypothesis that country-level commitment to the regulatory quality can moderate the associations between individuals’ entrepreneurship entry and their resources. More specifically, where there is a stronger commitment to the regulatory quality, the association between resource and entrepreneurship is strengthened. In countries that more strongly uphold the regulatory quality, the effect of perception of business opportunities on the probability of individuals switching into entrepreneurship enhances by a factor of 1.044 in odds (β = 0.044, OR = 1.044, p < 0.001). Therefore, Hypothesis 3 is supported.

Adding country-level uncertainty avoidance and the Three-way interaction term

Model 5 refers to a random-coefficient regression model in which country-level uncertainty avoidance was entered. It found no statistical significant association between the measure of uncertainty avoidance and entrepreneurship (β = –0.718, OR = 0.510, p > 0.1). Hypothesis 4 is not supported. Model 6 includes a three-way interaction between resource-based factor, regulatory quality, and uncertainty avoidance. The estimation implies that the positive impact of regulatory quality on opportunity-motivated individuals’ desirability of becoming entrepreneurship is weakened by 16.80% in odds (β = –0.184, odds ratio = 0.831, p < 0.01). Hypothesis 5 is therefore supported.

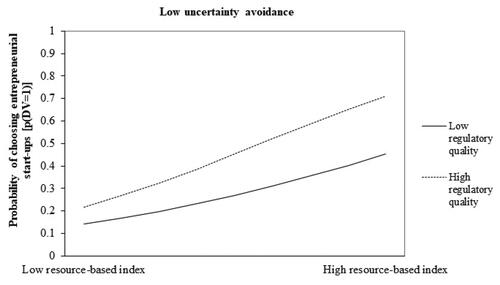

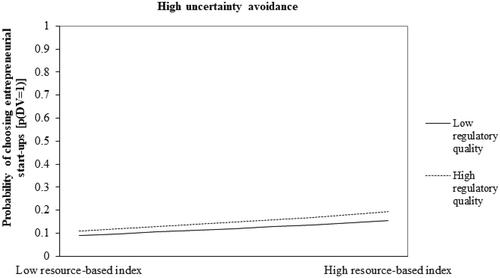

Furthermore, this research uses a median split analysis that involved splitting the dataset into “low uncertainty avoidance” and “high uncertainty avoidance” regimes, and then performing separate binomial logistic regressions for the two subsets. These tests are shown in . The effect of resources on entrepreneurial startups reduces considerably when moving from countries in low regimes to high regimes, but it remains positive and significant throughout (Low uncertainty avoidance regime: β = 0.811, OR = 2.250, p < 0.001; High uncertainty avoidance regime: β = 0.302, OR = 1.352, p < 0.001). Also, the moderating effect of formal institution becomes weaker as a function of the strength of a country’s commitment to the regulatory quality (Low uncertainty avoidance regime: β = 0.193, OR = 1.212, p < 0.001; Strong regime: β = 0.025, OR = 1.025, p < 0.1).

Simple slopes and graphic depiction of the moderating effects

Adopting the procedure developed by Preacher et al. (Citation2006), this paper performs slope tests. illustrates the significant interaction between opportunity perception and regulatory quality on entrepreneurship. Individuals’ opportunity perception had a greater positive, significant effect on their propensity of being self-employed in a country with a stronger commitment to the regulatory quality, as shown in the dashed line in .

and show the three-way mitigating effect between resource-based index, regulatory quality, and uncertainty avoidance on entrepreneurial startups. In , for countries with high degree of uncertainty avoidance, regulatory quality exerts a significant moderating effect on the relationship between opportunity perception and entrepreneurship (β = 0.193, p < 0.001). In comparison, the regulatory quality has a much weaker moderating impact on this relationship in the countries where uncertainty avoidance is high as shown in (β = 0.025, p < 0.1).

Test of endogeneity

This research takes the possibility of endogeneity into account in two steps (Wooldridge Citation2002). First, it identifies valid and relevant instrument variable and runs two-stage least squares (2SLS) regression analysis with an identified instrumental variable as the second step. According to Reeb, Sakakibara, and Mahmood (Citation2012), a good instrument must be relevant and excludable. The selection of instrument variable relies on theoretical reasoning as well as instrument validity test. This research used question “Q. Have you, in the past three years, personally provided funds for a new business started by someone else, excluding any purchases of stocks or mutual funds?” as the instrument variable. Given that this variable focuses on offering the funds for another business, such effects influence the dependent variable via the effect of resource-based index. This research performs relevance and validity tests of the instrumental variable. The correlation between the personal funds for a new business on the one hand, and resources on the other is significant while the relationship between this instrument and the dependent variable is not. Wald test returns the F statistic of 13.83 (p < 0.001), concluding the relevance of the selected instrument variable. By identifying this appropriate instrument variable, this research performs Wu-Hausman specification test. The result shows the F statistic of 2.27 (p = 0.131). The null hypothesis that the resource-based index is exogenous cannot be rejected, suggesting that the existence of endogeneity problem has a minimal concern in the models.

Robustness check

This study performs a sensitivity analysis. It collects the newest wave of GEM-2019 dataset and replicates the study. Multilevel binomial logistic regressions are then performed. The results are presented in Appendix B and Appendix C. The estimates did not systematically differ from those of the initial models.

Discussion

Theoretical contributions

This study is among the first to theoretically explain and especially examine how the impact of resource-based antecedents on entrepreneurship is subject to formal and informal contextual environments. While the significance of different resources on entrepreneurial startups has been acknowledged, this paper deals with recent calls to integrate resources and contextual antecedents in the analysis of entrepreneurial startups (Camelo-Ordaz et al. Citation2020; Lamine et al. Citation2021). The proposed theoretical framework gives rise to more nuanced insights on the effects of macro institutions. It theoretically explains and empirically assesses how the significant effects of country-level regulation can be bounded by a country’s cultural values on the relationship between resource-based factors and entrepreneurship. In particular, this research reveals that uncertainty avoidance weakens the impact of resources generated by strong commitment to regulatory quality and inhibits the social desirability of entrepreneurship. By adding this under-studied institutional interaction to the model, the present paper adds to the emerging research on how both formal and informal institutions can collectively channel micro resources toward activities related to entrepreneurship entry.

Moreover, the resource-based view has been criticized for its little effort to establish appropriate contexts (Peng et al. Citation2023). This research reveals that institutions might complement the instrumentality of individual resources. By embracing a multilevel approach, it extends the work of extant studies to provide a more comprehensive foundation. Using this foundation, researchers can investigate entrepreneurial startups that are affected not only by heterogeneous resources, which was the primary consideration in past research (e.g. De Clercq, Lim, and Oh Citation2013), but also by the external environment. Research that focusses on a single level only cannot make precise inferences about the dependence of entrepreneurial startups on higher-level contexts. These omissions lead to an incomplete understanding of entrepreneurship, since the hurdles and uncertainty that prohibits venture startups, even among resourceful entrepreneurs, might be overcome according to the extent that institutional arrangements offer and provide combination of resources across players. The results support the theoretical conjecture that there are some underlying macro mechanisms that link financial, human, and social capital to the outcome of entrepreneurship. Employing a multilevel empirical model to analyze individuals’ decisions helps us develop a more coherent explanation and assessment of venture startups.

Implications for management practice

This study has political implications for better understanding the heterogeneous rate of entrepreneurship. This research suggests that country-level institutions, particularly those marked by a stronger or weaker commitment to the regulatory quality and national cultural dimensions, determine individuals’ entrepreneurial entry. This research findings suggest that countries should promote entrepreneurial role models that highlight entrepreneurial startups as a cultural norm, which could be helpful to diminish the negative impact of uncertainty avoidance on entrepreneurship. These patterns reveal the importance of having administratively capable governments as well as the significance of having a better understanding of the impact of cultural values on entrepreneurial activity, so that countries can reap the benefits of starting new businesses. Moreover, in cultures characterized by high levels of uncertainty avoidance, government might concentrate not only on offering easier access to different capitals but also make sure that external resources can be combined efficiently with experience and knowledge that is already possessed by resourceful entrepreneurs. Otherwise, entrepreneurial skills might be channeled toward alternative activities that confront less uncertainties and require less efforts.

Limitations and Future research

Venture creations require dynamic capabilities, and country institutions are also evolving (Williamson Citation2000). Although they provide a large cross-country database, the GEM surveys only offer snapshots of individuals’ traits, intentions, and behaviors, throwing up a major barrier for longitudinal research. Future research might use alternative research designs and databases to investigate how entrepreneurial behavior and institutional arrangements co-evolve over time. Taking this kind of dynamic approach to the study of entrepreneurial startups presents a promising avenue for future research.

Conclusions

Blending research on the RBV and ideas from institutional approaches to economics into an integrated model, this study examines how financial, human, and social capitals interact with country-level formal and informal institutional characteristics in shaping entrepreneurial entry. Using 41,156 observations from 46 countries, this paper reveals that entrepreneurial startups are significantly influenced by resource-based factors. In addition, the results show that a country’s commitment to the regulatory quality strengthens the positive effects of resources on the choice of entrepreneurship, but this positive moderating effect becomes less significant in the countries with high level of uncertainty avoidance.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Tianchen Li

Dr Tianchen Li is a Senior Lecturer in International Management and Innovation at Middlesex University, UK. His research focuses on central questions in the fields of entrepreneurship, international business, and innovation. Dr. Li has published his work in leading journals such as Journal of World Business, International Business Review, Journal of Business Research, Management Decision, among others.

References

- Abdul, A., J. Kelley Donna, and L. Jonathan. 2020. “Market-Driven Entrepreneurship and Institutions.” Journal of Business Research 113:117–28.

- Aidis, R., S. Estrin, and T. Mickiewicz. 2008. “Institutions and Entrepreneurship Development in Russia: A Comparative Perspective.” Journal of Business Venturing 23 (6):656–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2008.01.005.

- Aragon-Mendoza, J., M. P. del Val, and S. Roig-Dobón. 2016. “The Influence of Institutions Development in Venture Creation Decision: A Cognitive View.” Journal of Business Research 69 (11):4941–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.04.056.

- Audretsch, D., and A. R. Thurik. 2001. “What’s New about the New Economy? Sources of Growth in the Managed and Entrepreneurial Economies.” Industrial and Corporate Change 10 (1):267–315. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/10.1.267.

- Autio, E., and Z. Acs. 2010. “Intellectual Property Protection and the Formation of Entrepreneurial Growth Aspirations.” Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 43:234–51.

- Autio, E., and Z. Acs. 2010. “Institutional Influences on Strategic Entrepreneurial Behavior.” Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 4 (3):234–51. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.93.

- Barney, J. 1991. “Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage.” Journal of Management 17 (1):99–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700108.

- Baumol, W. J. 1990. “Entrepreneurship: productive, unproductive, and destructive.” Journal of Political Economy 98 (5):893–921.

- Bettis, R. A., S. Ethiraj, A. Gambardella, C. Helfat, and W. Mitchell. 2016. “Creating Repeatable Cumulative Knowledge in Strategic Management.” Strategic Management Journal 37 (2):257–61. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2477.

- Bischoff, K. M., M. M. Gielnik, and M. Frese. 2020. “When Capital Does Not Matter: How Entrepreneurship Training Buffers the Negative Effect of Capital Constraints on Business Creation.” Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 14 (3):369–95. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.1364.

- Boudreaux, C. J., B. N. Nikolaev, and P. Klein. 2019. “Socio-Cognitive Traits and Entrepreneurship: The Moderating Role of Economic Institutions.” Journal of Business Venturing 34 (1):178–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2018.08.003.

- Boudreaux, C. J., and B. Nikolaev. 2019. “Capital is Not Enough: Opportunity Entrepreneurship and Formal Institutions.” Small Business Economics 53:709–738.

- Brinkerink, J., and E. Rondi. 2021. “When Can Families Fill Voids? Firms’ Reliance on Formal and Informal Institutions in RandD Decisions.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 45 (2):291–318. https://doi.org/10.1177/1042258719899423.

- Calza, F., C. Cannavale, and I. Z. Nadali. 2020. “How Do Cultural Values Influence Entrepreneurial Behavior of Nations? A Behavioral Reasoning Approach.” International Business Review 29 (5):101725. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2020.101725.

- Camelo-Ordaz, C., H. P. Diánez-González, N. Franco-Leal, and J. Ruiz-Navarro. 2020. “Recognition of Entrepreneurial Opportunity Using a Socio-Cognitive Approach.” International Small Business Journal 38 (8):718–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242620939843.

- Canestrino, R., M. Ćwiklicki, P. Magliocca, and B. Pawełek. 2020. “Understanding Social Entrepreneurship: A Cultural Perspective in Business Research.” Journal of Business Research 110:132–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.01.006.

- Castaño, M. S., M. T. Méndez, and M. Á. Galindo. 2015. “The Effect of Social, Cultural, and Economic Factors on Entrepreneurship.” Journal of Business Research 68 7:1496–500.

- Chan, C., and C. Du. 2022. “Formal Institution Deficiencies and Informal Institution Substitution: MNC Foreign Ownership Choice in Emerging Economy.” Journal of Business Research 142:744–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.01.016.

- Chen, C. C., P. G. Greene, and A. Crick. 1998. “Does entrepreneurial selfefficacy distinguish entrepreneurs from managers?” Journal of Business Venturing 13:295–316.

- Chowdhury, F., D. B. Audretsch, and M. Belitski. 2019. “Institutions and Entrepreneurship Quality.” Entrepreneurship Theory, and Practice 43 (1):51–81.

- Costa, S., A. Caetano, and S. Santos. 2016. “Entrepreneurship as a Career Option: Do Temporary Workers Have the Competencies, Intention and Willingness to Become Entrepreneurs?” Journal of Entrepreneurship 252:129–54.

- De Clercq, D., D. S. Lim, and C. H. Oh. 2013. “Individual-Level Resources and New Business Activity: The Contingent Role of Institutional Context.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 37 (2):303–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2011.00470.x.

- De Clercq, D., and P. Arenius. 2006. “The Role of Knowledge in Business Start-up Activity.” International Small Business Journal 24 (4):339–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242606065507.

- Dutta, N., and R. Sobel. 2021. “Entrepreneurship, Fear of Failure, and Economic Policy.” European Journal of Political Economy 66:101954. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2020.101954.

- Echambadi, R., B. Campbell, and R. Agarwal. 2006. “Encouraging Best Practice in Quantitative Management Research: An Incomplete List of Opportunity.” Journal of Management Studies 438:1801–20.

- Estrin, S., J. Korosteleva, and T. Mickiewicz. 2013. “Which Institutions Encourage Entrepreneurial Growth Aspirations?” Journal of Business Venturing 28 (4):564–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2012.05.001.

- Estrin, S., T. Mickiewicz, and U. Stephan. 2016. “Human Capital in Social and Commercial Entrepreneurship.” Journal of Business Venturing 314:449–67.

- Ferreira, J. J., C. I. Fernandes, P. M. Veiga, and S. Gerschewski. 2023. “Interlinking Institutions, Entrepreneurship and Economic Performance.” International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-07-2022-0640.

- Fuentelsaz, L., C. González, and J. P. Maicas. 2019. “Formal Institutions and Opportunity Entrepreneurship. The Contingent Role of Informal Institutions.” BRQ Business Research Quarterly 22 (1):5–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brq.2018.06.002.

- Gimenez-Jimenez, D., A. Calabrò, and D. Urbano. 2020. “The Neglected Role of Formal and Informal Institutions in Women’s Entrepreneurship: A Multi-Level Analysis.” Journal of International Entrepreneurship 182:196–226.

- Hofstede, G. 1991. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind. Newbury: McGraw-Hill.

- Hitt, M., K. Haynes, and R. Serpa. 2010. “Strategic Leadership for the 21st Century.” Business Horizons 53 (5):437–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2010.05.004.

- Jafari-Sadeghi, V., S. Kimiagari, and P. Biancone. 2020. “Level of Education and Knowledge, Foresight Competency, and International Entrepreneurship: A Study of Human Capital Determinants in the European Countries.” European Business Review 32 (1):46–68. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-05-2018-0098.

- Klyver, K., and K. Hindle. 2007. “The Role of Social Networks at Different Stages of Business Formation.” Small Enterprise Research 15 (1):22–38. https://doi.org/10.5172/ser.15.1.22.

- Kirca, A. H., G. T. M. Hult, K. Roth, S. T. Cavusgil, M. Z. Perryy, M. B. Akdeniz, et al. 2011. “Firm-specific assets, multinationality, and financial performance: a meta analytic review and theoretical integration.” Academy of Management Journal 54 (1):47–72.

- Lamine, W., A. Anderson, S. Jack, and F. Alain. 2021. “Entrepreneurial Space and the Freedom for Entrepreneurship: Institutional Settings, Policy and Action in the Space Industry.” Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 15 (2):309–40. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.1392.

- Lee, C. K., J. Wiklund, A. Amezcua, T. J. Bae, and A. Palubinskas. 2022. “Business Failure and Institutions in Entrepreneurship: A Systematic Review and Research Agenda.” Small Business Economics 584:1997–2023.

- Li, T. 2018. “Internationalisation and its determinants: A hierarchical approach.” International Business Review 27 (4):867–76.

- Li, T. 2023. “What Explains Entrepreneurial Start-Ups Across Countries: An Integrative Model.” Journal of General Management 48 (2):195–209. https://doi.org/10.1177/03063070221081577.

- Li, T. 2020. “Institutional Environments and Entrepreneurial Start-Ups: An International Study.” Management Decision 59 (8):1929–53. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-01-2020-0031.

- Li, D., L. Q. Wei, Q. Cao, and D. Chen. 2022. “Informal Institutions, Entrepreneurs’ Political Participation, and Venture Internationalization.” Journal of International Business Studies 53 (6):1062–90. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-021-00402-9.

- Liñán, F., and J. Fernandez-Serrano. 2014. “National Culture, Entrepreneurship and Economic Development: Different Patterns across the European Union.” Small Business Economics 42 (4):685–701. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-013-9520-x.

- Linder, C., C. Lechner, and F. Pelzel. 2020. “Many Roads Lead to Rome: How Human, Social, and Financial Capital Are Related to New Venture Survival.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 445:909–32.

- Ljunge, M., and M. Stenkula. 2021. “Fertile Soil for Intrapreneurship: Impartial Institutions and Human Capital.” Journal of Institutional Economics 17 (3):489–508. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1744137420000612.

- Manolova, T. S., R. V. Eunni, and B. S. Gyoshev. 2008. “Institutional Environments for Entrepreneurship: Evidence from Emerging Economies in Eastern Europe.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 32 (1):203–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2007.00222.x.

- Manolova, T. S., N. M. Carter, I. M. Manev, and B. S. Gyoshev. 2007. “The differential effect of men and women entrepreneurs’ human capital and networking on growth expectancies in Bulgaria.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 31 (3):407–426.

- Martínez-Fierro, S., J. M. Biedma-Ferrer, and J. Ruiz-Navarro. 2019. “Impact of High-Growth Start-Ups on Entrepreneurial Environment Based on the Level of National Economic Development.” Business Strategy and the Environment 29 (3):1007–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2413.

- McGahan, A. M., and R. Victer. 2010. “How Much Does Home Country Matter to Corporate Profitability?” Journal of International Business Studies 41 (1):142–65. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2009.69.

- Muralidharan, E., and S. Pathak. 2016. “Informal Institutions and International Entrepreneurship.” International Business Review 26 (2):288–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2016.07.006.

- Neumeyer, X., S. C. Santos, A. Caetano, and P. Kalbfleisch. 2019. “Entrepreneurship Ecosystems and Women Entrepreneurs: A Social Capital and Network Approach.” Small Business Economics 53 (2):475–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-9996-5.

- North, D. C. 1990. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Pacheco, D. F., J. G. York, T. J. Dean, and S. D. Sarasvathy. 2010. “The Coevolution of Institutional Entrepreneurship: A Tale of Two Theories.” Journal of Management 364:974–1010.

- Papageorgiadis, N., F. McDonald, C. Wang, and P. Konara. 2021. “The Characteristics of Intellectual Property Rights Regimes: How Formal and Informal Institutions Affect Outward FDI Location.” “ International Business Review 291:1–11.

- Parker, S. C. 2004. The Economics of Self-Employment and Entrepreneurship. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Peng, Mike W., Joyce C. Wang, Nishant Kathuria, Jia Shen, and Miranda J. Welbourne Eleazar. 2023. “Toward an Institution-Based Paradigm.” Asia Pacific Journal of Management 40 (2):353–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-022-09861-6.

- Preacher, K. J., P. J. Curran, and D. J. Bauer. 2006. “Computational tools for probing interactions in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis.” Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics 31 (4):437–448.

- Radaelli, C. M., and F. De Francesco. 2007. Regulatory Quality in Europe: Concepts, Measures, and Policy Processes. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Reeb, D., M. Sakakibara, and I. P. Mahmood. 2012. “From the Editors: Endogeneity in International Business Research.” Journal of International Business Studies 43 (3):211–8. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2011.60.

- Redding, G. 1993. The Spirit of Chinese Capitalism. New York: Walter de Gruyter.

- Sahasranamam, S., and M. K. Nandakumar. 2020. “Individual Capital and Social Entrepreneurship: role of Formal Institutions.” Journal of Business Research 107:104–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.09.005.

- Scott, W. R. 1995. Institutions and Organizations. Thousand Oaks, London: SAGE.

- Simón-Moya, V., L. Revuelto-Taboada, and R. F. Guerrero. 2014. “Institutional and Economic Drivers of Entrepreneurship: An International Perspective.” Journal of Business Research 67 (5):715–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.11.033.

- Snijders, T., and Bsoker, R. Eds. 2012. Multilevel Analysis: An Introduction to Basic and Advanced Multilevel Modeling, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Ltd.

- Stel, A., M. Carree, and R. Thurik. 2005. “The Effect of Entrepreneurship on National Economic Growth.” Small Business Economics 24 (3):311–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-005-1996-6.

- Stenholm, P., Z. J. Acs, and R. Wuebker. 2013. “Exploring Country-Level Institutional Arrangements on the Rate and Type of Entrepreneurial Activity.” Journal of Business Venturing 28 (1):176–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2011.11.002.

- Thai, M. T. T., and E. Turkina. 2014. “Macro-Level Determinants of Formal Entrepreneurship versus Informal Entrepreneurship.” Journal of Business Venturing 29 (4):490–510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2013.07.005.

- Uddin, M., A. Chowdhury, S. Zafar, S. Shafique, and J. Liu. 2019. “Institutional Determinants of Inward FDI: Evidence from Pakistan.” International Business Review 28 (2):344–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2018.10.006.

- Urbano, D., and C. Alvarez. 2014. “Institutional Dimensions and Entrepreneurial Activity: An International Study.” Small Business Economics 42 (4):703–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-013-9523-7.

- Urbano, D., S. Aparicio, and D. B. Audretsch. 2019. “Twenty-Five Years of Research on Institutions, Entrepreneurship, and Economic Growth: What Has Been Learned?” Small Business Economics 53 (1):21–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-0038-0.

- Uriarte, S., J. Espinoza-Benavides, and D. Ribeiro-Soriano. 2023. “Engagement in Entrepreneurship after Business Failure. Do Formal Institutions and Culture Matter?” International Entrepreneurship Management Journal 19:941–73.

- Venâncio, A., and J. Jorge. 2022. “The Role of Accelerator Programmes on the Capital Structure of Startups.” Small Business Economics 59 (3):1143–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-021-00572-8.

- Volodina, A., and G. Nagy. 2016. “Vocational Choices in Adolescence: The Role of Gender, School Achievement, Self-Concepts, and Vocational Interests.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 95:58–73.

- Webb, J., T. Khoury, and M. A. Hitt. 2020. “The Influence of Formal and Informal Institutional Voids on Entrepreneurship.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 44 (3):504–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/1042258719830310.

- Wernerfelt, B. 1984. “A Resource-Based View of the Firm.” Strategic Management Journal 5 (2):171–80. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250050207.

- Williams, N., and T. Vorley. 2015. “Institutional Asymmetry: How Formal and Informal Institutions Affect Entrepreneurship in Bulgaria.” International Small Business Journal 338:840–861.

- Williamson, O. E. 2000. “The New Institutional Economics: Taking Stock, Looking Ahead.” Journal of Economic Literature 38 (3):595–613. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.38.3.595.

- Wooldridge, J. M. 2002. Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Wu, J., and X. Chen. 2014. “Home Country Institutional Environments and Foreign Expansion of Emerging Market Firms.” International Business Review 23 (5):862–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2014.01.004.

- Yang, M. M., T. Li, and Y. Wang. 2020. “What Explains the Degree of Internationalization of Early-Stage Entrepreneurial Firms? A Multilevel Study on the Joint Effects of Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy, Opportunity-Motivated Entrepreneurship, and Home-Country Institutions.” Journal of World Business 55 (6):101114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2020.101114.

- Yang, J. 2023. “A Middle-Range Theory of Acquirer Corporate Governance and Host-Country Institutional Infrastructure in Cross-Border Acquisitions.” International Studies of Management and Organization 532:77–103.

Appendix A.

Individual variables for regulatory quality index

Appendix B.

Robustness test-multilevel logistic regression analysis

Appendix C.

Robustness test-multilevel logistic regression analysis