ABSTRACT

Introduction

Tooth decay is the most common reason for non- emergency hospital admissions in 5–9 year olds. As such, it is included in the England school curriculum at 8–9 years to facilitate improved oral hygiene and prevent tooth decay.

Aim

Measure student and teacher baseline oral hygiene knowledge; determine effect of the e-Bug oral hygiene lesson on student knowledge; explore teacher views on the lesson.

Methods

Mixed methods evaluation. Baseline student and teacher knowledge questionnaires. Intervention classes received the e-Bug lesson. Post-intervention student questionnaires and semi-structured teacher focus groups.

Results

121 students completed baseline questionnaire – results indicate high knowledge about which foods/drinks are bad for teeth; low knowledge about tooth decay and appropriate tooth brushing behaviours; confusion over what foods and drinks contained sugar. 58 students received the intervention; 10 out of 17 questions in lessons showed significant increase in correct responses (p < 0.05). No significant improvements reported in the control. Overall teachers were very positive about the lesson and suggested some improvements.

Conclusion

Children have gaps in oral hygiene knowledge. Teachers acknowledge oral hygiene as a priority which should be taught more frequently, citing e-Bug as a valuable oral hygiene educational resource. Curriculum leaders should be encouraged to increase oral hygiene education using a whole school approach.

Introduction

Oral disease is a significant worldwide public health problem (WHO, Citation2017) estimated to affect 3.9 billion people worldwide (Marcenes et al. Citation2013). Untreated caries (tooth decay) in permanent teeth is the most common oral condition in both men and women (Marcenes et al. Citation2013). Although tooth decay in England has decreased, almost a quarter of 5 year olds (equivalent to ~165,000 children) experienced tooth decay in 2014/15, making tooth extraction under general anaesthetic the most common reason for non-emergency hospital admission in 5 to 9 year oldsoften (PHE, Citation2016). Tooth decay is preventable by reducing dietary sugar, improving oral hygiene and increasing fluoride (PHE, Citation2014). Therefore, improving these behaviours in children should help to reduce tooth decay and the associated health burden.

Educating children at a young age can set healthy behaviours for life. e-Bug is an international educational resource for children and young people aged 4–18 years which aims to set healthy behaviours around microbes, hygiene, prevention of infection and antibiotics (McNulty et al. Citation2011). Operated by Public Health England, the e-Bug resources include teacher packs containing interactive lessons. The teacher packs are complemented by student websites with online games, quizzes and revision guides to facilitate students learning at home. All the e-Bug resources are free to download from the e-Bug website at www.e-Bug.eu and the materials are available in 23 different languages. Previous evaluations of e-Bug lessons and activities including community resources, online games, farm hygiene, peer education, and science shows demonstrate they significantly improve knowledge in young people (Eley et al. Citation2018, Citation2019; Hale et al. Citation2017; Hawking et al. Citation2013; Lecky et al. Citation2014, Citation2010; Young et al. Citation2017).

To help address the gap in interactive oral hygiene teacher resources, the Dental Public Health Department at Bart’s and the London School of Medicine and Dentistry collaborated with the e-Bug team at Public Health England in 2015 to develop an educational lesson on oral hygiene for Key Stage 2 junior school students (7–11 years old) in England. The lesson was developed by a multi-disciplinary group including dentists, a dental public health consultant and researchers, using evidence based prevention advice (PHE, Citation2014). Teachers and students were involved closely in lesson plan development (Weston-Price et al. Citation2015).

The e-Bug oral hygiene lesson contains worksheets, a PowerPoint presentation and video and is linked to the science and Personal, Social and Health Education (PSHE) curriculum for Key Stage 2. The lesson focuses on how to prevent dental caries by demonstrating the importance of limiting sugar intake and brushing teeth twice a day with fluoride toothpaste. Reference with: http://www.e-bug.eu/junior_pack.aspx?cc=eng&ss=2&t=Oral%20hygiene. (Appendix A; full lesson. Appendix B; detailed information on the lesson activities and learning outcomes). The webpage was viewed 3,557 times in the first two years (average page view time of 1 minute 18 seconds) which is an adequate amount of time for educators to download the resource. French, German and Romanian translations are available.

This study aimed to measure student and teacher baseline knowledge around oral hygiene, determine the effect of the e-Bug oral hygiene lesson on student knowledge, and evaluate teacher views on the lesson to explore possible improvements.

Methods

Research design

The study was a mixed methods evaluation using quantitative baseline and post-intervention student knowledge questionnaires, teacher baseline knowledge questionnaires, and qualitative post-intervention teacher focus groups.

Sampling and recruitment

The study aimed to recruit six schools across two sites: one rural (Gloucestershire) and one urban area (Greater London). All primary schools teaching 7–11 year olds in Gloucestershire (129) were invited to participate by email. Researchers failed to recruit three schools in this area due to a lack of financial incentive; therefore researchers agreed that one school per area would suffice for a pilot study. A convenience sample of two schools was recruited to reflect rural and urban areas.

The intervention

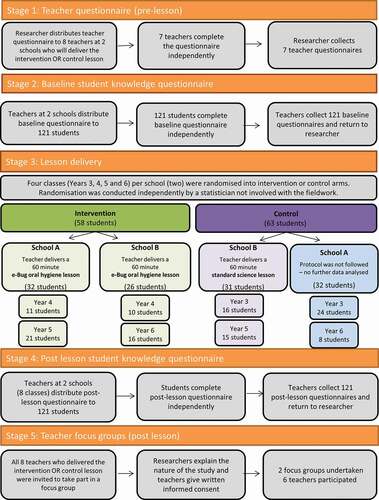

Four classes (Years 3, 4, 5 and 6) in each of the two schools were randomised into intervention or control arms as can be seen in . Randomisation was conducted independently by a statistician not involved with the fieldwork. Intervention classes received the e-Bug oral hygiene lesson by their class teacher. Control classes received a standard science lesson that was not an oral hygiene lesson by their class teacher.

Table 1. Randomisation of classes per school.

Ethics

Queen Mary University London Ethics Research Committee provided ethical approval (QMERC2015/75) and PHE provided approval for the service evaluation. After schools agreed to participate, teachers and parents were approached prior to the lesson to provide written informed consent for their schools children to participate; participants could opt out at any point. Questionnaires were collected in line with the Data Protection Act 1998 regulations including audio recording of teachers and the publishing of anonymised quotes. All researchers who observed the sessions had a Disclosure Barring Check (DBS), through PHE or QMUL, to work with children.

Data collection and analysis ()

Data collection took place between September 2015 and July 2016; see for the full data collection process. A researcher was present during each lesson to oversee data collection and answer any teacher queries.

Student baseline and post-intervention knowledge data

A ten item questionnaire (Appendix C), piloted with schools in 2015, was modified and used to collect oral hygiene knowledge data from students across intervention and control classes, (i) immediately before the lesson (baseline knowledge) and (ii) directly after the lesson (post-lesson knowledge).

Baseline and post-intervention knowledge questionnaire data were analysed by author SWP using descriptive statistics for frequencies of proportions of correct responses () separated by those children who received the e-Bug lesson (n = 58) and those who were deemed per-protocol controls (n = 31). The statistical difference between correct responses before and after the lessons was calculated by applying the McNemars test for paired data. All statistical analysis was completed in SPSS version number 23.

Table 2. Oral hygiene baseline knowledge for all students (n = 121).

Teacher baseline knowledge data

Teachers due to deliver the intervention or control lesson completed a validated quantitative baseline questionnaire (Petersen et al. Citation2004) exploring their oral hygiene knowledge prior to lesson delivery (Appendix D). Data was inputted into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet; analysis consisted of descriptive statistics based on frequencies of responses.

Teacher qualitative data

Within one week of the lessons, teachers who delivered the intervention or control lessons participated in face-to-face semi-structured focus groups facilitated by researchers who are trained in qualitative research methods. The researchers (CE and SWP) had both been involved in the development of the oral hygiene lesson. The 30 minute focus groups explored teachers’ views on oral health education, knowledge around the topic of oral hygiene, opinions on the e-Bug lesson and suggestions for improvements. The topic guide for the focus groups was developed and agreed between researchers prior to the focus groups (Appendix E). Both focus groups were observed by a second researcher who recorded notes. Focus groups were audio recorded, transcribed verbatim, and checked for accuracy by SWP and VY.

A researcher (SWP) thematically analysed (Braun and Clarke, Citation2006) the focus group transcripts by hand and a second researcher (VY) double coded using NVivo 10 qualitative data software. The researchers discussed the data and coding to identify emerging themes prior to developing a thematic framework. Any discrepancies between researchers were resolved through discussion until an agreement was reached.

Results

Data was collected from four classes in one Gloucestershire primary school and four classes in one Greater London primary school. provides information on student demographics.

Table 3. Student demographics.

Student results

Baseline knowledge

121 students participated in the study and completed the baseline knowledge questionnaires; 64 from Gloucestershire and 57 from Greater London (). shows the baseline oral hygiene knowledge of the children participating in the study (n = 121). Children had variable baseline knowledge (12–99% correct responses) about which food and drink contained sugar and could be bad for your teeth. Over 90% of children answered correctly that fizzy drinks contained sugar (94%) and could be bad for your teeth (96%); and that water (99%) and milk (96%) are not bad for your teeth. However, a quarter of children incorrectly responded that diet fizzy drinks were not bad for your teeth, and one fifth incorrectly responded that biscuits did not contain sugar. There were also gaps in knowledge regarding other foods and drinks; only 12% responded correctly that milk contains sugar; cornflakes contain sugar (41%); and fruit juices could be bad for your teeth (41%).

Three quarters of children had high baseline awareness that you should brush your teeth twice a day (82%). However, only half of children understood that you can protect your teeth from tooth decay (52%), and that tooth decay can make your teeth hurt (48%). Less than half of the children correctly answered that just before bedtime is the most important time of day to brush your teeth (31%), 40% correctly answered that it is better to use toothpaste with fluoride in it and 31% knew that after brushing your teeth you should spit rather than rinse toothpaste out of your mouth.

Effect of interactive e-Bug oral hygiene lesson

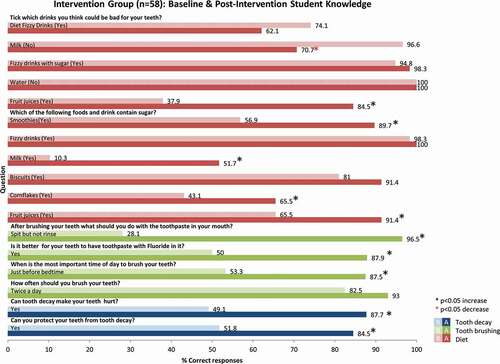

and show baseline and post-intervention knowledge of children who received the e-Bug oral hygiene lesson (n = 58), as well as the difference in correct responses and levels of significance.

Table 4. Intervention group baseline knowledge, post-intervention knowledge and knowledge change (n = 58).

58 students received the e-Bug oral hygiene lesson and completed a baseline and post-intervention questionnaire. An increase in correct responses was reported for 14 out of 17 questions, of which 10 were significant changes (p < 0.05). These significant improvements in knowledge were seen in the following ten questions: you can protect your teeth from tooth decay; tooth decay makes your teeth hurt; fruit juices, cornflakes, milk and smoothies contain sugar; fruit juices could be bad for your teeth; the most important time of day to brush your teeth is just before bedtime; it is better to have toothpaste with Fluoride in it; after brushing your teeth you should spit the toothpaste out but do not rinse.

Four questions showed an increase in correct responses but were not significant as they had high baseline figures (>75%) for correct responses (biscuits and fizzy drinks contain sugar; fizzy drinks with sugar are bad for your teeth; brush your teeth twice a day). Therefore, it is difficult to report a significant increase in knowledge based on the sample size of 58 children. One question ‘could water be bad for your teeth’ could not see an improvement as there was 100% correct responses before and after the lesson.

When children were asked to ‘tick which drinks you think could be bad for your teeth’, two of the correct responses (milk and diet fizzy drinks) decreased following the lesson. Milk decreased from 97% to 71% (p = 0.000); diet fizzy drinks decreased from 74% to 62% (p > 0.05). These responses are directly related to the Activity 1A and 1B which were dependent on diet diaries and the common soft drinks brought into class. Students appeared to understand the link between sugar and tooth decay; i.e. that drinks that contain sugar can damage our teeth. They did not however demonstrate the distinction between ‘free sugars’ which damage our teeth and ‘milk sugars’ which are not harmful to our teeth; nor did they demonstrate knowledge that acid in diet fizzy drinks can damage our teeth. ‘Free sugars’ refer to sugars added to foods and drinks by the manufacturer, cook or consumer, and sugars naturally present in honey, syrups, and fruit juices (WHO, Citation2015). ‘Milk sugars’ refer to the lactose in milk which is considerably less harmful to teeth. Although diet fizzy drinks are ‘sugar-free’ they have a low pH, and these acidic drinks damage tooth enamel; any fizzy drinks, diet fizzy drinks, and fruit juices are examples of acidic drinks which are harmful to teeth.

Intervention compared to control

31 control students received a standard science lesson with no oral hygiene component and completed the baseline and post-intervention questionnaire. No significant increases in correct responses were reported. However a significant decrease in correct responses was seen for whether fruit juices contain sugar. As reported in , 32 control students incorrectly received a non-e-Bug oral hygiene lesson created by the teacher rather than a non oral hygiene science lesson, therefore their post-intervention knowledge data was excluded from the analysis.

Teacher results

Quantitative results

shows the questions asked in the baseline teacher questions. Baseline questionnaire results (Appendix F) from seven teachers show that their knowledge on the causes of dental caries appeared strong, with all seven teachers being aware that bacteria and sugar caused tooth decay. Teachers correctly identified that sugar, sweets, soft drinks and smoking could damage teeth, as well as milk, tea or coffee with added sugar. All teachers understood that tooth brushing was important and all but one noted dentist visit and fluoride as preventative measures; but only half identified avoiding sugar as a way to prevent tooth decay. All seven teachers reported that they had good or very good knowledge and skills with which to teach children about teeth and care of teeth, and that they had received this from a variety of sources including dentists, books and relatives.

Table 5. Questions from teacher baseline questionnaire.

Five out of seven teachers described their students’ dental condition as fair or poor and four felt that children in their class needed ‘a lot’ or ‘some’ dental treatment. Teachers reported that oral hygiene education was important and they acknowledged that they had a responsibility to deliver the topic. The majority expressed that they are happy to be involved in oral health education. However, currently only two teachers of the seven reported teaching about teeth in the past year; five teachers reported instructing children in tooth cleaning less than once every month, and two teachers reported never discussing tooth cleaning in class.

Qualitative results

Two teacher focus groups were conducted post-teaching with three teachers in Gloucestershire and three teachers in Greater London. Five key themes emerged from the qualitative data (reported in ): Teachers’ knowledge and attitudes towards oral health; access to materials and advance preparation; lesson timings; linking to the National Curriculum; lesson activities. Participant teachers voiced that oral health education is multidisciplinary; being delivered by dentists, parents and teachers, and they were satisfied to be involved in oral health education for children. Teachers agreed that oral health education is a priority and should be taught regularly in schools; if oral hygiene was included in Science National Curriculum at every year group then teachers would be able to prioritise this topic. Teachers viewed the e-Bug lesson overall very positively and provided suggestions for improvement about lesson length; all teachers thought the e-Bug lesson contained too much for a 1 hour lesson, it would have been better if a longer duration was allocated to the lesson or perhaps broken down into smaller units. Teachers suggested removing the diet and brushing diaries as it was not realistic to ask children (especially younger children) to complete this at home. They added that e-Bug should make the advanced lesson preparation clearer, so that teachers can collect empty drinks and juice bottles prior to the lesson for the sugar activity.

Table 6. Thematic findings and quotes from teacher focus groups.

Discussion

Main findings

This study indicates that children (7–11 years) have low baseline knowledge about tooth decay and appropriate tooth brushing behaviours. There is confusion over which foods and drinks contain sugar, highlighting the need for more oral health education in schools. Currently, teeth are only in the National Curriculum in Year 4 (8–9 year olds) however, the e-Bug oral hygiene lesson is a suitable resource to assist in the delivery of oral hygiene education for 7–11 year olds.

This study indicates that the e-Bug oral hygiene lesson led to significant (p < 0.05) improvement in students’ correct responses on the learning outcomes:-

You can protect your teeth from tooth decay

Tooth decay can make your teeth hurt

Fruit juices, cornflakes, milk and smoothies contain sugar

Fruit juices could be bad for your teeth

Just before bedtime is the most important time of the day to brush your teeth

Toothpaste with fluoride is better for your teeth

After brushing your teeth you should spit but not rinse

Even though teachers’ oral hygiene knowledge was not consistent with national guidance (i.e. only half identified that avoiding sugar is a way of preventing tooth decay (PHE, Citation2014)), teachers perceived their knowledge as ‘good’. Most teachers were happy to be involved in oral health education for children; they saw oral health education as a combined responsibility between dentists, parents and teachers. However, very few teachers had taught oral hygiene topics in the last year. The English National Curriculum only mandates that pupils in year 4 (8–9 year olds) need to be taught to identify the different types of teeth in humans and their simple functions (Department of Health Citation2015;). The research presented in this study suggests that oral hygiene should be explicitly included in the English curriculum, not just as a section in ‘human teeth’ in year 4, but in its own merit as a priority for children in England. Feedback from the teacher focus groups about the e-Bug oral hygiene lesson was overall very positive with some suggested improvements.

Strengths and limitations

This study followed a mixed method approach; using both quantitative and qualitative methods of enquiry assessing baseline and post-intervention student knowledge, teacher baseline knowledge and teacher views. Baseline knowledge questionnaires from 121 students across two local authorities allowed researchers to evaluate baseline knowledge about oral hygiene in children; the only sample of this type in England. Baseline knowledge can be used to inform educational needs in different age groups within NICE recommendations (NICE, Citation2014) and the National Curriculum (Department of Health Citation2015). This study enabled the testing of the e-Bug oral hygiene lesson in two varied settings across England, one rural and one inner city, to a range of student ages (7–11 year olds).

Half of the control group were excluded from post-intervention analysis as they did not receive the control lesson outlined in the protocol; they received an oral hygiene lesson developed by their teacher which was not the agreed control. This meant that the control sample for further analysis was small (n = 31) and only represented one geographical region. Furthermore, the randomisation of classes meant that the control group was made up of Year 3, 5 and 6 and no Year 4’s; whereas the intervention group was made up of Year 4, 5 and 6 and no Year 3’s. Nevertheless, the e-Bug oral hygiene lesson was designed for 7–11 year olds so should be suitable for all students in the study. But, it should be noted that the statistical analysis did not account for any differences in age.

Qualitative focus groups with teachers explored a range of teacher views, which consequently brought synergism, snowballing of ideas, and stimulation of participants. Reoccurring themes emerged in both teacher focus groups (for example around lesson timings and curriculum links, suggesting data saturation had been reached) however, further interviews may have helped to enrich the data. The results from the focus groups identified strong themes with which to inform the modification of the lesson. However, the small number of questionnaires completed limits the generalisability of the questionnaire findings regarding teachers’ knowledge and attitudes to oral health education; hence the results should be viewed with caution.

The student questionnaire had been piloted previously as part of a Master’s thesis and refined for this study; however, teachers reported that the language used in the questionnaire was difficult for the younger children to understand. With this in mind, future work should consider modifying the language to be more suitable for children. The teacher questionnaire had been developed and validated in a previous WHO study (Petersen et al. Citation2004); however, the responses should be taken with care due to the small sample size, particularly as only Year 4 teachers currently have to teach about teeth as per the National Curriculum.

Comparison with existing literature

The authors believe this study is the first of its kind to evaluate children’s baseline oral hygiene knowledge in the England primary school setting and highlight potential gaps in children’s understanding to inform educational needs. This study provided an evidence-based lesson to address the gaps in knowledge by educating children on tooth decay, tooth brushing and limiting sugar intake; aiming to give children the knowledge, confidence and skills to adopt life-long appropriate and healthy oral hygiene behaviours.

Previous research has shown improvements in student knowledge about other infection related topics after the delivery of an e-Bug lesson, activity and e-Bug online games (Lecky et al. Citation2010; Hawking et al. Citation2013; Lecky et al. Citation2014; Hale et al. Citation2017; Young et al. Citation2017; Eley et al. Citation2018; Eley et al. Citation2019) and this study contributes to this growing literature.

This e-Bug oral hygiene lesson fits into current NICE recommendations (NICE Citation2014) that primary schools introduce specific schemes to improve and protect oral health in areas where children are at high risk of poor oral health, and consider supervised tooth brushing schemes in areas where children are at high risk of poor oral health. NICE (Citation2014) also recommend that primary and secondary schools raise awareness of the importance of oral health as part of a ‘whole-school’ approach.

Teacher views on the e-Bug lessons, including the oral hygiene lesson, have also been documented (Eley et al. Citation2017). In this 2015 survey of 695 educators, 97% rated the e-Bug oral hygiene module as excellent or good (Eley et al. Citation2017). Only 28% of educators had previously used the lesson, which could be attributed to the fact that the survey was conducted in 2015, not long after the release of the oral hygiene lesson online. Our study provides an in depth understanding of teacher feedback and improvements that could be made to the oral hygiene lesson.

Many studies have looked at teacher oral health knowledge, and studies in India, Saudi Arabia and Nigeria have reported mixed results (Jain et al. Citation2016; Aljanakh, Siddiqui, and Mirza Citation2016; Sekhar et al. Citation2014; Mota et al. Citation2016; Dedeke et al. Citation2013). Teachers in Saudi Arabia appeared to have a good knowledge (Aljanakh, Siddiqui, and Mirza Citation2016), whereas knowledge in India (Jain et al. Citation2016; Sekhar et al. Citation2014; Mota et al. Citation2016) and Nigeria (Dedeke et al. Citation2013) was reported as low, with less than half of teachers surveyed correctly knowing that bacteria and sugar cause tooth decay, or that fluoride toothpaste can be used to prevent tooth decay. Our study can be used as a pilot to inform larger studies to look at teachers’ oral hygiene knowledge in England.

Implications for e-Bug lesson

The e-Bug oral hygiene lesson had a significant positive effect on students’ knowledge overall, except for understanding about whether milk and diet fizzy drinks can be bad for your teeth. Children understood the important association between sugar in food/drink and tooth decay in the lesson (i.e. that drinks that contain sugar can damage our teeth) but students lack knowledge on ‘free’ sugars, and also the damage acid can have on our teeth. Cow’s milk naturally contains ‘free’ sugars that do not damage our teeth, these are classified as ‘milk sugars’ and are distinguished from other ‘non-milk extrinsic sugars’ (NMES) which are damaging to teeth (Moynihan Citation2002). Diet fizzy drinks do not contain sugar but they have a low pH level so are high in acidity which also damages our teeth (Tahmassebi et al. Citation2006). Currently, these topics of ‘milk sugars’ and ‘acid’ are not fully covered in the lesson. Modifications to the lesson should consider developing: (1) an activity to educate children about how acid in diet drinks can damage your teeth and (2) an activity to clarify that ‘milk sugars’ do not cause tooth decay and are not bad for our teeth.

The e-Bug lesson contained too much content for a 1 hour session; therefore modifications to reduce the duration of the lesson need to be considered. Diaries are an evidence based tool for assessing diets by clinicians; however, the diet and brushing diary exercises did not work well in the classroom setting as student completion rates were very low. Therefore, we recommend removing the diaries from the e-Bug oral hygiene lesson; this would also reduce the lesson time which was highlighted as a problem by teachers.

Based on the teacher knowledge questionnaires, the ‘background information’ section for teachers will be modified to cover areas that teachers had a lack of knowledge in, including avoiding sugar to prevent tooth decay. Furthermore, the ‘Advanced Preparation’ section will also be modified, highlighting more clearly that drinks bottles should, if possible, be saved and collected in advance. This would reduce preparation time needed in the immediate run up to the lesson and also reduce cost, as the teacher would not need to purchase drinks specifically for the lesson.

Implications for schools, teachers and department for education

Children’s baseline knowledge around tooth decay and appropriate tooth brushing behaviours for a healthy mouth appear low. Therefore, future guidelines and curriculum leaders should consider addressing this by implementing oral hygiene teaching into the curriculum at an earlier age and in a cyclical nature. Oral hygiene should be directly included in the English curriculum, so that teachers can prioritise delivering this important topic and help improve the burden of tooth decay on public health.

Overall, the e-Bug oral hygiene lesson was well-received by teachers and fits into aspects of the Key Stage 2 (ages 7–11 years) National Curriculum for science in England. This study suggests that this lesson could be focused to Year 4 as teeth are explicitly named in the science curriculum and therefore the oral hygiene lesson may be more readily accommodated. Additionally, teachers across both sites indicated that the food labelling and tooth brush timing exercises contributed to practical maths elements of the curriculum which could expand the lesson’s appeal beyond science.

Appendix_E_-_Teacher_topic_guide.docx

Download MS Word (23.5 KB)Appendix_D_-_Teacher_questionnaire.docx

Download MS Word (46.7 KB)Appendix_C_-_Student_questionnaire.docx

Download MS Word (183.8 KB)Appendix_B_-_Lesson_activities.docx

Download MS Word (673.7 KB)Appendix_A_-_Oral_Hygiene_Lesson.doc

Download MS Word (1.8 MB)Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Catherine Hayes from the Public Health England Primary Care Unit for assisting with this study and Emma Eley for assisting with pre acceptance copy-editing. Final thanks to the schools, teachers and students who took part in the research. This work was supported by Public Health England.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary material

The supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

References

- Aljanakh, M., A. A. Siddiqui, and A. J. Mirza. 2016. “Teachers’ Knowledge about Oral Health and Their Interest in Oral Health Education in Hail, Saudi Arabia.” International Journal of Health Sciences 10 (1): 87–93.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101. doi:https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Dedeke, A. A., M. E. Osuh, F. B. Lawal, O. Ibiyemi, O. O. Bankole, J. O. Taiwo, O. Denloye, and G. A. Oke. 2013. “Effectiveness of an Oral Health Care Training Workshop for School Teachers: A Pilot Study.” Annals of Ibadan Postgraduate Medicine 11 (1): 18–21.

- Department of Health. 2015. “National Curriculum in England: Science Programmes of Study.” https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-curriculum-in-england-science-programmes-of-study/national-curriculum-in-england-science-programmes-of-study#lower-key-stage-2–years-3-and-4

- Eley, C. V., V. L. Young, B. A. Hoekstra, and C. A. M. McNulty. 2017. “An Evaluation of Educators’ Views on the e-Bug Resources in England.” Journal of Biological Education 52 (2): 166–173. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00219266.2017.1285808.

- Eley, C. V., V. L. Young, C. V. Hayes, G. Parkinson, K. Tucker, N. Gobat, and C. A. M. McNulty. 2018. “A Mixed Methods Pilot of Beat the Bugs: A Community Education Course on Hygiene, Self-Care and Antibiotics.” Journal of Infection Prevention 19 (6): 278–286. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1757177418780990.

- Eley, C. V., V. L. Young, C. V. Hayes, N. Q. Verlander, and C. A. M. McNulty. 2019. “Young People’s Knowledge of Antibiotics and Vaccinations and Increasing this Knowledge Through Gaming: Mixed-Methods Study Using e-Bug” JMIR Serious Games 7 (1): e10915. doi:https://doi.org/10.2196/10915.

- Hale, A. R., V. L. Young, A. Grand, and C. A. M. McNulty. 2017. “Can Gaming Increase Antibiotic Awareness in Children? A Mixed-Methods Approach.” JMIR Serious Games 24 (5): e5. doi:https://doi.org/10.2196/games.6420.

- Hawking, M. K., D. M. Lecky, N. Q. Verlander, and C. A. M. McNulty. 2013. “Fun on the Farm: Evaluation of a Lesson to Teach Students about the Spread of Infection on School Farm Visits.” PloS One 8 (10): e75641. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0075641.

- Jain, S., N. Bhat, K. Asawa, M. Tak, A. Singh, K. Shinde, N. Gandhi, and A. Doshi. 2016. “Effect of Training School Teachers on Oral Hygiene Status of 8–10 Years Old Government School Children of Udaipur City, India.” Journal of Clinical and Diagnosistic Research 10 (8): ZC95–9.

- Lecky, D. M., C. A. McNulty, P. Touboul, T. Koprivova Herotova, J. Benes, P. Dellamonica, N. Q. Verlander, P. Kostkova, and J. Weinberg. 2010. “Evaluation of e-Bug, an Educational Pack, Teaching about Prudent Antibiotic Use and Hygiene, in the Czech Republic, France and England.” The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 65 (12): 2674–2684. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkq356.

- Lecky, D. M., M. K. Hawking, N. Q. Verlander, and C. A. M. McNulty. 2014. “Using Interactive Family Science Shows to Improve Public Knowledge on Antibiotic Resistance: Does It Work?” PLoS One 9 (8): e104556. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0104556.

- Marcenes, W., N. J. Kassebaum, E. Bernabe, A. Flaxman, M. Naghavi, A. Lopez, and C. J. L. Murray. 2013. “Global Burden of Oral Conditions in 1990–2010: A Systematic Analysis.” Journal of Dentistry Research 92 (7): 592–597.

- McNulty, C. A., D. M. Lecky, D. Farrell, P. Kostkova, N. Adriaenssens, T. Koprivova´ Herotova´, J. Holt, et al. 2011. “Overview of e-Bug: An Antibiotic and Hygiene Educational Resource for Schools.” The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 66 (5): v3–12. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkr119.

- Mota, A., L. K. C. Oswa, D. A. Sajnani, and A. K. Sajnani. 2016. “Oral Health Knowledge, Attitude, and Approaches of Pre-Primary and Primary School Teachers in Mumbai, India.” Scientifica. doi:https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/5967427. 5967427.

- Moynihan, P. J. 2002. “Dietary Advice in Dental Practice.” British Dental Journal 193: 563–568. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4801628.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). 2014. “Oral Health: Local Authorities and Partners.” https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph55/resources/oral-health-local-authorities-and-partners-pdf-1996420085701

- Petersen, P. E., B. Peng, B. Tai, and M. Fan. 2004. “Effect of a School-Based Oral Health Education Programme in Wuhan City, Peoples Republic of China.” International Dentistry Journal 54 (1): 33–41.

- Public Health England. 2014. “Delivering Better Oral Health: An Evidence-Based Toolkit for Prevention.” https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/605266/Delivering_better_oral_health.pdf

- Public Health England. 2016. “National Dental Epidemiology Programme for England: Oral Health Survey of Five-Year-Old Children 2015.” http://www.nwph.net/dentalhealth/14_15_5yearold/14_15_16/DPHEP%20for%20England%20OH%20Survey%205yr%202015%20Report%20FINAL%20Gateway%20approved.pdf

- Sekhar, V., P. Sivsankar, M. A. Easwaran, L. Subitha, N. Bharath, K. Rajeswary, and S. Jeyalakshmi. 2014. “Knowledge, Attitude and Practice of School Teachers Towards Oral Health in Pondicherry.” Journal of Clinical Diagnostic Research 8 (8): ZC12–5.

- Tahmassebi, J. F., M. S. Duggal, G. Malik-Kotru, and M. E. Curzon. 2006. “Soft Drinks and Dental Health: A Review of the Current Literature.” Journal of Dentristy 34 (1): 2–11. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdent.2004.11.006.

- Weston-Price, S., V. Young, B. Hoekstra, T. Gadhia, V. Muirhead, L. Robinson, and C. Pine. 2015. “Development and Evaluation of Online Oral Hygiene, Prevention of Infection Module in e-Bug: European Project.” 62nd Congress of the European Organisation for Caries Research, Queen Mary University, Brussels, Belgium.

- World Health Organisation. 2015. “Sugar Guidelines.” http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2015/sugar-guideline/en/

- World Health Organisation. 2017. “What Is the Burden of Oral Disease?” http://www.who.int/oral_health/disease_burden/global/en/

- Young, V. L., A. Cole, D. M. Lecky, D. Fettis, B. Pritchard, N. Q. Verlander, C. V. Eley, and C. A. M. McNulty. 2017. “A Mixed-Method Evaluation of Peer-Education Workshops for School-Aged Children to Teach about Antibiotics, Microbes and Hygiene.” The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 72 (7): 2119–2126. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkx083.