ABSTRACT

Field teaching is an essential component of botany and ecology; however, field classes were among the most likely to be cancelled during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Virtual alternatives that could be used to meet learning outcomes for botany (e.g. plant identification, surveying skills development) were largely unavailable at this time. To address this, a semi-immersive virtual botanical fieldtrip was developed using H5P. The resource consists of a 360 site tour, an interactive book with a series of interactive videos to mimic quadrat analysis and plant identification, and a plant identification guide to aid students in identifying species. Students responded largely positively to the resource, although they had a clear preference to undertake fieldwork in person in a more traditional manner. The resource is the first such virtual botanical fieldtrip and allows the retention of most learning outcomes for a traditional field class. This type of resource has considerable potential in a post-pandemic world to widen participation and let students experience ecosystems that they might otherwise not have the opportunity to investigate. The resource is available for use under a CC BY-NC-SA licence.

Introduction

Teaching and learning ‘in the field’ is a core component of many ecologically-focused degree programmes including botany, zoology, environmental sciences and physical geography. Field classes have been shown to improve academic performance (Goodenough et al. Citation2015; Gamarra et al., 2010; Beltran et al. Citation2020) and enhance student learning (Eaton Citation2000; Easton and Gilburn Citation2012; Dillon et al. Citation2006; Hix Citation2015) as well as providing important social bonding for students (Anderson and Miskimins Citation2006; Race et al. Citation2021). Fieldwork and training in identification of plants for botany and ecology students is particularly important given evidence that the skills associated with identifying plants are declining and being taught less at university level but remain sought after in industry and important in a variety of areas to aid understanding of ecosystems (Stroud et al., 2022; Stagg and Donkin Citation2013; Peacock and Bacon Citation2018). However, field trips were the most likely activity in ecological teaching to be cancelled outright in the immediate wake of COVID-19 (Bacon & Peacock, Citation2021) in 2020, raising concerns about how to facilitate learning during local and national lockdowns and how to continue to train students in important field techniques.

This increased likelihood for field classes to be cancelled compared to other teaching formats, was largely due to the difficulty of moving them online and the amount of work required to do so (Bacon & Peacock, Citation2021). Aside from the difficulty of moving field classes online, there was also a lack of freely available and suitable resources to do this easily or quickly. Among the options available to instructors were using students’ local area (McKinnon Citation2021) or own home (Schnell et al. Citation2021) and online participatory science platforms (Gerhart et al. Citation2021). Another option was virtual field courses.

Virtual or online fieldwork is not a new concept but it has not been widely applied, particularly in plant ecology. There are some clear potential benefits to online field classes (Cooke et al., 2020), such as enabling remote fieldwork for students with mobility impairments (Stokes et al. Citation2012) or reducing costs and removing financial barriers to participation in field classes (Cliffe Citation2017); however, some studies have found that there are either no additional benefits to student learning from online field classes (Moreno and Mayer Citation2002) or that they can even be detrimental to learning (Makransky et al. Citation2017). Freely available resources to set up virtual field trips are not always easy to find or even available at all, and many may be held behind institutional barriers and not openly accessible. For physical geography and geology, there are some excellent resources such as Virtual Glaciers Citation2020 (https://vrglaciers.wp.worc.ac.uk/wordpress/) and the University of Leeds’ Virtual Landscapes Citation2020 (https://www.see.leeds.ac.uk/virtual-landscapes/) as well as the possibility of using GoogleEarth and GoogleMaps among other resources. However, when trying to teach botany virtually, there are very few resources that are available to simulate fieldwork activities such as quadrating (identifying and estimating abundance of plant species within a defined, usually centimetre to metre-scale area square area), identifying species, or using field guides. Many otherwise good resources (e.g. Virtual Glaciers) do not have good, interactive online material for conducting plant surveys or viewing the close-up details of plants needed to identify them. There are many datasets that can be used (e.g. the National Biodiversity Data Centre https://www.biodiversityireland.ie/) but resources that show the process of botanical field work were lacking.

In plant ecology, some of the most fundamental field skills that students need to develop are plant identification, quadrating, and site description and classification. Existing online resources did not meet the needs of students to undertake these tasks in an Irish context in 2020. In order to address this, a virtual field trip to Salthill, Galway was developed in July – August 2020. This area includes embryonic dunes at Griffith beach and a small parkland (Celia Griffin Park) with both ‘managed’, often and easily mowed, and ‘unmanaged’, less often mowed grassland areas. The site is surrounded by Galway bay on three sides and the urban area of Salthill on one side. The aim was to replicate, as much as possible, the process of identifying and assessing the vegetation of the area at three ‘sites’ (Dunes, Managed Grassland and Unmanaged Grassland) and retain the intended learning outcomes for students ().

The aim of this paper is to describe the resource developed, consider student responses to the resource, and consider whether the intended learning outcomes for the module were addressed with the switch to online learning as well as how (or if) to incorporate virtual learning in future years. A link to the primary resource components, which are free to use, is provided below in . Resources are IP protected as the copyright of the author and the National University of Ireland, Galway/University of Galway but are free to use once properly credited.

Table 1. Links to the H5P resources.

Methods

The virtual field session was created using Blackboard and H5P. The resource included multiple interactive recordings, detailed interactive 360 tours and a photographic plant guide to the most common species students might encounter in each quadrat. The videos were recorded using a Samsung S9 smartphone with audio recorded using a lapel mic and Samsung S9+ smartphone. Photographs were taken on the Samsung S9 phone. Videos were edited using the freely available Blender software (https://www.blender.org/features/video-editing/). The videos were then uploaded to YouTube and linked to Blackboard via H5P, where they remain hosted. The videos were collated into an interactive book resource. This allows the addition of ‘interactions’ that can include a pause in the video for students to answer a question, text or a photograph appearing to provide some context or draw attention to a particular feature (in this case often a close-up of a plant or plant part) and summary questions at the end of the video. A 360 tour of the site was also included to place the quadrat locations in context to each other and to provide a fuller view of the area.

In order to assess student engagement with the resource, students were asked to complete an anonymous survey via a GoogleForms online. Links to the resources are provided in and can also be found at https://plantecologypalaeoecologylab.wordpress.com/. The student survey can be found in Appendix 1.

Results

Resource output

Content was available to students via Blackboard in both the H5P as an interactive book and 360 tour. Links to the YouTube version of the videos, which are higher resolution that that supported by H5P were also provided to students. In total, 21 videos were made available through the resource.

Learning outcomes and student feedback

Feedback was collected from the student cohort via optional surveys (appendix 1). Of the 17 students in the cohort, 10 answered the survey. shows that students who answered the survey generally considered themselves to have acquired the core skills associated with the field day.

Figure 2. Student responses to question: Do you think you learned the following skills from session? Tick all that apply. (n = 10).

shows a strong response from students that most of the specific tasks were learned – all were confident that they could take a quadrat, be safe in the field, assess a grassland habitat and identify some common Irish grassland and dune plant species. They were also confident about comparing between managed and unmanaged grasslands. One student did not feel that the resource allowed them to learn how humans effected the area and two were not confident that they had learned how to write a site description.

shows students responses to whether or not they enjoyed the activity and felt that they had missed anything by doing it online rather than in person. This was more mixed than responses to the question shown in . Students were very mixed on whether they would like to do a similar activity again, with 60% saying yes or yes but that they would prefer a shorter version (30% each), while the other 40% did not wish to do this type of activity again (20% no and 20% only if there was no field option available). Generally, students were mixed on whether they thought they had missed any learning opportunities by doing the session online but only 20% were sure that they had (). Additionally, 60% of students recognised benefits of doing the remote field work over traditional in person sessions. These included being able to go back over the recordings ‘It was easy to go back over if I didn’t understand something’; ‘You can watch the videos as many times as you want’, and ‘The videos allow you to listen to the material again so you don’t miss anything’. However, students also highlighted difficulties with the approach including, ‘difficult to ascertain abundance cover from video + photograph’ and ‘Much more difficulty identifying plants without a close, prolonged examination, including touch’.

Figure 3. a) Would you like to do this type of activity again?; b) Do you think you missed out on any learning objectives by doing this type of activity remotely?; c) Do you think this type of activity has any benefits over a traditional field session? (n = 10) Black = yes; White = no.

Students who answered ‘yes’ or ‘not sure’ to the question ‘Do you think you missed out on any learning objectives by doing this type of activity remotely (2b)?’ were asked to elaborate in a free text box. Students highlighted that they had not been able to physically interact with the plants ‘Much more difficulty identifying plants without a close, prolonged examination’ and ‘I think that if we did the field day in person I would remember all the plants and techniques far better’.

When asked if they would recommend keeping the activity in future years, only 10% (1 student) gave an outright no, while all others gave some level of support to keeping the virtual field session (). Two students agreed that the activity could be recommended if it were shortened but the majority of students (50%) felt that it should only be used as a backup in case in person field sessions were not possible.

Figure 4. Responses to the question: Would you recommend keeping this activity for future years?

Discussion

Student experience

Virtual field classes have been widely regarded as opening up field learning to students who have accessibility challenges (Stokes et al. Citation2012) and some recent research has also highlighted that it can improve engagement from minority students (Beltran et al. Citation2020). However, it has also been shown to decrease the ‘community’ benefit for students (Anderson and Miskimins Citation2006; Race et al., Citation2021), which was clearly felt by students on this module, and it may also reduce student learning compared to in person classes (Makransky et al. Citation2017). Reduced learning outcomes were not observed for students in this study but as this was the first year the course ran, they were not assessable.

Students engaged well with the virtual field session, with 16/17 students on the course completing the associated course work. The session aimed to mimic an in person field day where students would spend approximately five hours in the field collecting data. The videos came to approximately 2 hours 45 minutes of recorded material that included 15 quadrats and six additional videos. The additional videos consisted of site introductions, field safety, ‘how to’ for making a quadrat and ‘how to’ identify plants in the field using a common Irish botanical resource, Webb’s An Irish Flora (Parnell and Curtis Citation2012), the most complete botanical key to the Irish flora and a standard resource used in training botanists and ecologists in Ireland. Quadrats were filmed from the point of view of the person examining the flora, as much as possible, in order to attempt to mimic the process of physically investigating low-growing flora in a quadrat. Students were appreciative of the resource ‘I think the way it was filmed and executed was really good and helpful’; ‘It was perfectly laid out and everything was clear and easy to understand’, although some would have preferred more professional camerawork ‘some video was shaky which made it difficult to watch for extended periods, h5p limits the resolution of the videos and only displays 480p when actual video resolution is higher’. Students did have access to higher resolution videos via links to YouTube if they wanted them but informal discussions with students indicated that this was not used by most students.

The virtual field day allowed students to learn the skills that were the focus of the session (plant identification, habitat assessment and quadrating) but the majority of students felt that they would have learned more or learned easier in the field, similar to the findings of Citation2022). Several students highlighted that the recorded material was ‘too much’ and one unanticipated impact of the recorded material, was that students spent much more time than intended on the tasks. They appreciated being able to watch things again and pause videos, but this has led to them spending more time on quadrats than they would in the field. Students also pointed out the loss of engagement between course participants in the online version ‘[missed] team work’ and the lack of being physically able to interact with the plants, ‘You don’t actually get to see the plants’; ‘I think that if we did the field day in person I would remember all the plants and techniques far better’. This highlights that the affective domain is the one perhaps most impacted by virtual learning and needs to be considered in designing these types of online activity. Students can learn the techniques, but will still not be as prepared for fieldwork if they do not get to experience the field in person.

Virtual resource positives

There are many clear benefits to virtual fieldwork including reducing novelty effect (Cooke et al. Citation2021), preparing students for future in person field work, and increasing inclusivity (Morales et al., 2020). Students highlighted a number of benefits to the online resource, including that they could look at videos again or pause to look something up. Many of them liked the online resources, particularly the plant guide and 360 tour and liked that they could ensure that they had really seen and heard everything of importance. From an instructor perspective, the resource can be reused and repurposed for future sessions.

Virtual resource negatives

From the instructor perspective, creating the resource took a considerable amount of time, particularly given that the instructor had no previous experience in making and editing videos. Recording the videos and putting the resource together took several weeks of work. Compared to a traditional, in person field course, there is a much greater workload on the instructor. It is also far less interactive for the instructor with no real-time student feedback or more informal discussions with students. While the resource can be used again, it does still represent a very high time input to set it up initially.

Students noted in particular that they did not get to ‘touch’ or ‘really look at’ the plants. For some plants, touch and smell are important components of identification. For example, rowan (Sorbus aucuparis) is often described as ‘downy to touch’ and hedge woundwort (Stachys sylvatica) is noted for its ‘unpleasant’ smell (Parnell and Curtis Citation2012). This clearly impacts the affective domain of learning, which is of considerable importance in field sciences. Students also noted that they did not get to ‘chat’ with each other, highlighting that the virtual field class does not support the development of student community as an in person session would (Race et al. Citation2021). An additional, unanticipated negative was that students also took longer than intended to complete the videos. Many noted that it took a long time but this was often because they paused and replayed the videos multiple times. This means that they spent far longer than intended on the resource and needs to be addressed in future use. Future use of the resource will require students to examine three, rather than five, quadrates to attempt to reduce this problem and the instructor will emphasise the time that is intended to be spent on the quadrats.

Recommendations and Implications

The online resource provides an additional means of engaging students with plants. There is clear potential to expand this type of resource to bring students closer to ecosystems that are not in their immediate areas without physical attendance, prepare them for fieldwork and as open educational resources – perhaps as massive open online courses (MOOCs). This type of resource has the potential to bring different plants and ecosystems to a very wide audience. If the resources are made open access, as this one is, it also provides a valuable educational resource without paywall or geographic boundaries.

Creating such a resource does not need to be expensive if done locally but it is time-expensive and that should be considered. All of the technology used to create the resource was either already owned by the author (e.g. phone and lapel mic) or open access (e.g. use of Blender and H5P). It is recommended that a similar approach be taken by anyone else attempting to create this type of resource to keep costs low. Student co-creation is another possibility that could be investigated, with students making or contributing to a video as part of a module assessment. This could be a valuable addition to the resources and to student learning and engagement. Key recommendations for creating a similar resource are:

Use already available equipment (e.g. Smartphone cameras) where possible

Utilize open software (e.g. Blender, H5P – others available)

Consider student co-creation of resources

In summary

The pedagogy for online teaching is developing rapidly with improvements and changes in technology (Stickney et al. Citation2019) and the resource that was created to support students’ botanical learning would not have been possible a few years ago. However, this resource represents an emergency move to online teaching due to the COVID-19 pandemic is not the same as more usual online teaching, which can be several years in development (Youmans Citation2020). There are doubtless many things that could be improved or further developed time-permitting.

In this small cohort of students, the experience of the virtual field day was quite mixed. One student found it extremely difficult, describing it as ‘prohibitively difficult’ to identify plants and two students found it quite stressful. Others found it to be a good resource that they considered to be high quality ‘I liked the very clear camera work, the historical background and the helpful identification guide!’ and facilitated them learning the skills well (). The range of experiences highlights that, while this is a good option for some students and was certainly considered better than cancelling a field day, it is not something that works for everyone.

The resource will be used again in future years either as a replacement for an in person field day if there are restriction on travel or in a shortened format to help prepare students for future in person field days. The resource was shown to be successful in meeting the desired learning outcomes but student feedback on the length of time spent on the existing resource will be acted upon. Additionally, although virtual field work can and does increase inclusivity in many ways, internet access and digital poverty, particularly when students were required to work from home, is a significant issue. This was not an issue for this cohort of students but one student did raise it as a concern. However, at the time, the university was allowing students to use on-site computers if needed. This is something that needs to be considered carefully when asking students to complete virtual field sessions.

It is also worth noting that the cohort of students who used the resource did not chose online learning but had it forced upon them due to circumstances. It is possible that the resource would be of significant benefit to a course designed to teach botany or ecology online and that students, knowing that they have chosen an online learning option, would be more interested and engaged with this online version of a field class. The possibilities for this type of virtual botanical fieldtrip in terms of widening participation and exposing students to these (and indeed different) habitats are not trivial. Theoretically, similar field courses could be created in habitats around the world and offer students the possibility of immersing themselves in botanical fieldtrips in a variety of different ecosystems. To the author’s knowledge, this is the first attempt at a semi-immersive virtual botanical fieldtrip.

Conclusion

It is important to remember that this resource was created in the backdrop to COVID-19 and was a response to an emergency situation that needed to be created and implemented quickly. However, the virtual field day was successful in meeting the learning outcomes for students (how to take a quadrat, learning some relevant Irish plant species; learning key species in Irish embryonic dunes and coastal grasslands; identifying plant species) and students engaged well with the resources provided. The resource will be used in future years to introduce students to vegetation analysis but the aim will be to use it to prepare students for in person field work or as an alternative to in person field work if students are unable to attend a session for any reason.

Acknowledgments

Kate Molloy, NUI Galway, is thanked for help and support with H5P and helpful discussion. Jan Smith NUI Galway is thanked for helpful comments/discussion. David Wood is thanked for assistance with filming/video production/field support and helpful discussion. Writing the paper was supported by the Erasmus+ Digilego project (2020-1-DE01-KA226-005814).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anderson, D. S., and J. L. Miskimins. 2006. “Using Field-Camp Experiences to Develop a Multidisciplinary Foundation for Petroleum Engineering Students.” Journal of Geoscience Education 54 (2): 172–178. doi:10.5408/1089-9995-54.2.172.

- Bacon, K. L., and J. Peacock. 2021. “Sudden Challenges in Teaching Ecology and Aligned Disciplines During a Global Pandemic: Reflections on the Rapid Move Online and Perspectives on Moving Forward.” Academic Practice in Ecology & Evolution 11 (8): 3551–3558. doi:10.1002/ece3.7090.

- Beltran, R. S., E. Marnocha, A. Race, D. A. Croll, G. H. Dayton, and E. S. Zavaleta. 2020. “Field Courses Narrow Demographic Achievement Gaps in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology.” Ecology and Evolution 10 (12): 5184–5196. doi:10.1002/ece3.6300.

- Cliffe, A. D. 2017. “A Review of the Benefits and Drawbacks to Virtual Field Guides in Today’s Geoscience Higher Education Environment.” International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 14 (1): 28. doi:10.1186/s41239-017-0066-x.

- Cooke, J., Y. Araya, K. L. Bacon, J. M. Bagniewska, L. Batty, T. R. Bishop, M. Burns, et al. 2021. “Teaching and Learning in Ecology: A Horizon Scan of Emerging Challenges and Solutions.” Oikos 130 (1): 15–28. doi:10.1111/oik.07847.

- Dillon, J., M. Rickinson, K. Teamey, M. Morris, M. Y. Choi, D. Sanders, and P. Benefield. 2006. “The Value of Outdoor Learning: Evidence from Research in the UK and Elsewhere.” The School Science Review 87 (320): 107–113.

- Easton, E., and A. Gilburn. 2012. “The Field Course Effect: Gains in Cognitive Learning in Undergraduate Biology Students Following a Field Course.” Journal of Biological Education 46 (1): 29–35. doi:10.1080/00219266.2011.568063.

- Eaton, D. 2000. “Cognitive and affective learning in outdoor education.” Dissertation Abstracts International – Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences.60 (10–A): 3595.

- Gerhart, L. M., C. C. Jadallah, S. S. Angulo, and G. C. Ira. 2021. “Teaching an Experiential Field Course via Online Participatory Science Projects: A COVID-19 Case Study of a UC California Naturalist Course.” Academic Practice in Ecology & Evolution 11 (8): 3537–3550. doi:10.1002/ece3.7187.

- Goodenough, A. E., R. N. Rolfe, L. MacTavish, and A. G. Hart. 2015. “The Role of Overseas Field Courses in Student Learning in the Biosciences.” Bioscience Education. doi:10.11120/beej.2014.00021.

- Hix, D. M. 2015. “Providing the Essential Foundation Through an Experiential Learning Approach: An Intensive Field Course on Forest Ecosystems for Undergraduate Students.” Journal of Forestry 113 (5): 484–489. doi:10.5849/jof.14-065.

- Makransky, G. Makransky, T. S. Terkildsen, and R. E. Mayer. 2017. “Adding Immersive Virtual Reality to a Science Lab Simulation Causes More Resence but Less Learning.” Learning & Instruction 60: 225–236. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2017.12.007.

- McKinnon, L. 2021. “YIMBY—Yes, in My BackYard!—the Successful Transition to a Local Online Ecology Field Course.” Academic Practice in Ecology & Evolution 11 (22): 12542–12548. doi:10.1002/ece3.6881.

- Moreno, R., and R. Mayer. 2002. “Learning Science in Virtual Reality Multimedia Environments: Role of Methods and Media.” Journal of Educational Psychology 94 (3): 598–610. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.94.3.598.

- Pagani-Núñez, E., M. Yan, Y. Hong, Y. Zeng, S. Chen, P. Zhao, and Y. Zou. 2022. “Undergraduates’ Persecutions on Emergency Remote Learning in Ecology in the Post-Pandemic Era.” Ecology and Evolution 12 (3): e8659. doi:10.1002/ece3.8659.

- Parnell, J., and T. Curtis. 2012. Webb’s an Irish Flora. 8th ed. Cork, Ireland: Cork University Press.

- Peacock, J., and K. L. Bacon. 2018. “Enhancing Student Employability Through Urban Ecology Fieldwork.” Higher Education Pedagogies 3 (1): 440–450. doi:10.1080/23752696.2018.1462097.

- Race, A. I., M. De Jesus, R. S. Beltran, and E. S. Zavaleta. 2021. “A Comparative Study Between Outcomes of an In-Person versus Online Introductory Field Course.” Academic Practice in Ecology & Evolution 11 (8): 3625–3635. doi:10.1002/ece3.7209.

- Schnell, L. J., G. L. Simpson, D. M. Suchan, W. Quere, H. G. Weger, and M. C. Davis. 2021. “An At-Home Laboratory in Plant Biology Designed to Engage Students in the Process of Science.” Ecology & Evolution 11 (24): 17572–17580. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.8441.

- Stagg, B. C., and M. Donkin. 2013. “Teaching Botanical Identification to Adults: Experiences of the UK Participatory Science Project ‘Open Air Laboratories’.” Journal of Biological Education 47 (2): 104–110. doi:10.1080/00219266.2013.764341.

- Stickney, L. T., R. F. Bento, A. Aggarwal, and V. Adlakha. 2019. “Online Higher Education: Faculty Satisfaction and Its Antecedents.” Journal of Management Education 43 (5): 509–542. doi:10.1177/1052562919845022.

- Stokes, A., T. Collins, J. Maskall, J. Lea, P. Lunt, and S. Davies. 2012. “Enabling Remote Access to Fieldwork: Gaining Insight into the Pedagogic Effectiveness of ‘Direct’ and ‘Remote’ Field Activities.” Journal of Geography in Higher Education 36 (2): 197–222. doi:10.1080/03098265.2011.619004.

- University of Leeds’ Virtual Landscapes. Accessed 14th June 2020. https://www.see.leeds.ac.uk/virtual-landscapes/

- Virtual Glaciers. Accessed 29 October 2020. https://vrglaciers.wp.worc.ac.uk/wordpress/

- Youmans, M. 2020. “Going Remote: How Teaching During a Crisis is Unique to Other Distance Learning Experiences.” Journal of Chemical Education 97 (9): 3374–3380. doi:10.1021/acs.jchemed.0c00764.

APPENDIX Appendix 1:

Student Survey

This survey is one of several that will be conducted throughout this course to assess your expectations and experiences of moving though what will now be a “virtual” fieldwork module with some real world activities. It is important that you are developing the key skills required for plant/environmental scientists and that you are meeting our planned learning outcomes. This (and the other) survey(s) will help me to track your engagement and learning throughout the course. The data collected may form part of an academic publication on how teaching this type of course in higher education works out (this is a very new format for teaching botany). If you do not wish your data to be included in this potential study, please indicate this in the relevant question below. No identifying data will be collected or used in any study. Please ask me if you have any questions. Dr Karen Bacon ([email protected])

Participant Information Sheet

Investigating student experiences of ecological field work in a virtual and blended context

You are invited to take part in this research project that aims to investigate the effectiveness of blended and online learning in BPS3101 (Techniques in field ecology and conservation). Participation is voluntary; you do not need to take part and, even if you agree to take part, you can withdraw from the study at any time with no negative effects for you. Please read this sheet carefully so that you know what you are being asked to do, and feel free to ask any questions you wish before deciding whether to go ahead or not.

Research purpose

In this project, I am interested in finding out how well the blended and online components of the course have helped you to develop ecological techniques and skills. I am particularly interested to know if you think some of the online material should be retained for use in future years and what improvements could be made.

Your involvement. To do this, I am asking volunteers to complete some online surveys during the year. Your involvement should take no longer than approximately 10 minutes per survey. I will also seek volunteers for a 30 minute focus group to discuss how you felt the module has gone and to get your thoughts on improvements, particularly in relation to the online and blended components of the course. Data collected are intended to improve this course and may also be used as part of an academic publication. Participation in all aspects is entirely voluntary.

Benefits

The benefits of taking part in this project are that you will provide valuable information on the new structure of the course and help to improve it for future students.

Risks

The risks associated with this project are none for participants.

What next?

Thank you for taking the time to read this information. If you would like any further information, please contact Dr Karen Bacon ([email protected]). If you wish to take part in this research, please tick the relevant box in question 1.

Survey

Question 1:

Are you willing for your answers to be included in an academic study of how this course runs? (Your name or any other identifying information will NOT be included).

Question 2:

With what gender do you identify?

Question 3:

For the Salthill (Grassland and Sand Dunes) field day (fully online), did you complete all of the online material?

Yes

No

Most (over 50%)

Some but not all (Less than 50%)

Question 4:

For the Salthill (Grassland and Sand Dunes; fully online) field day, do you think you learned the following skills from this session (tick all that apply)

How to take a quadrat

How to ensure your safety in the field

How to assess a grassland habitat

How to identify some common Irish grassland plants

How to compare between different management regimes in grasslands

How to identify some common Irish sand duen plenat

How management effects these areas (sand duens and grasslands)

How human interactions effect these areas

How to write a site description

Question 5:

Please comment on what you liked or did not like about the Grassland and Sand Dunes field day.

Question 6:

Would you like to do this type of activity again?

Yes

No

Yes but a shorter version

Yes but only if it was because it wasn’t possible to run an in person field day

Question 6:

Do you think this type of activity has any benefits over a traditional field session?

Yes

No

Question 7:

What benefits or not do you think this type of activity has/misses over a traditional field session

Question 8:

Do you think you missed out on any learning objectives by doing this activity remotely?

Yes

No

Not sure

Question 9:

If yes or not sure – which ones and why?

Question 10: Would you recommend keeping this activity for future years?

Yes – as it is

Yes – but in a shorter version

Yes – but in a longer version

Yes – wit modifications (please elaborate below)

Yes – but only as a backup

No

Question 11: Please elaborate on your answer above

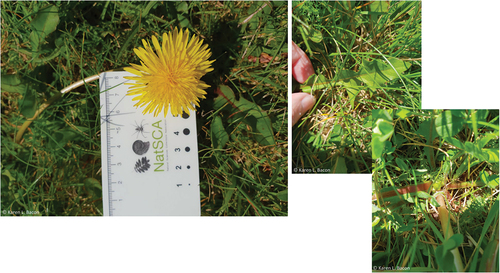

Salthill Vegetation Guide (2020). This file provides some examples of key flora found in the Salthill, Co. Galway area. They are not in any particular order and you will need to look at their features and look them up to determine where they may grow and what family they are in. You can use these photos in your reports but include copyright information (this is to encourage good practice). This is also not an exhaustive list – there are many more species of flowering plant found in the area. You may see other species in the videos too but this should help you with many of the most common species.

All photographs are copyrighted © Karen L. Bacon (2020). https://digilego.eu/oer/23

Species name:

Eriphorum angustifolium

Species name:

Taraxacum agg.

Species name:

Ranunculus repens

Species name:

Ranunculus acris

Species name:

Trifolium pratense

Species name:

Trifolium repens

Species name:

Trifolium dubium

Species name:

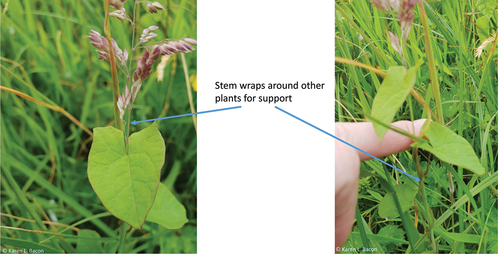

Calystegia soldanella or C. sepiumThis one is a little tricky because it looks more like hedge bindweed but by location and plant form it is more likely to be sea bindweed. Hedge bindweed usually has white flowers but these are a very pale pink. The leaves are more similar to hedge bindweed.

Species name:

Calystegia sepium

This species can be confused with the invasive Japanese knotweed (Reyonutria japonica) due to the size and shape of its leaves. However, bindweeds wrap around other plants to support themselves.

Species name:

Cymbalaria muralis

Species name:

Geranium robertianum

Species name:

Anagallis arvensis

Species name:

Veronica chamaedrys

Species name:

Raphanus raphanistrum ssp. maritimus

Species name:

Raphanus raphanistrum ssp. Raphanistrum or a white occurrence of Raphanus raphanistrum ssp. maritimus It is a little difficult to tell which exact variety this is.

Species name:

Lotus corniculatus

Species name:

Vicia sepium

Species name:

Vicia cracca

Species name:

Capsella bursa-pastoris

Species name:

Cakile maritima

Species name:

Atriplex laciniata

Species name:

Prunella vulgaris

Species name:

Chamaenerion angustifolium

Species name:

Epilobium hirsutum

Species name:

Senecio sp;

probably Senecio jacobaea There are probably a couple of different species of closely related ragworts in the area.

Species name:

Achillea millefolium

Species name:

Heracleum sphondylium

Species name:

Rubus fruticosus

Species name:

Plantago lanceolata

Species name:

Plantago major

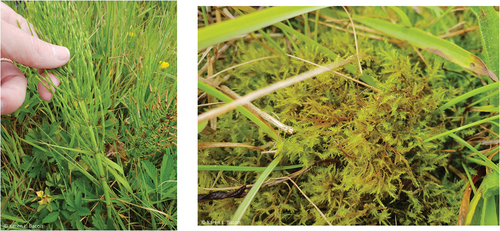

Note on grasses: It was almost always quite windy when I was filming/photographing so the grasses are particularly difficult to photograph.

When identifying grasses, there are numerous factors to consider, but some of the simple ones are:

Is the flowering head a spike or a panicle and does the inflorescence have a clear “front and back” as in the photo opposite.The first two seminars in the Irish grasslands project (BSBI) are particularly helpful for the basics. See link on Blackboard.

Species name:

Dactylis glomerata

Species name:

Holcus lanatus

Species name:

Lolium perenne

Species name:

Fescue sp. (probably)

Species name:

Agrostis sp. (probably)

These are not particularly good photographs. Check on wildflowersofireland.net for better examples.

Species name:

Cirsium vulgare

Species name:

Cirsium palustre

Species name:

Leucanthemum vulgare

Species name:

Bellis perennis

Species name:

Tripleurospermum maritimum

This seems like the most likely mayweed species, though it could also be T. chamomilla; however, location makes this less likely and the receptacle at the centre of the flower head does not look hollow (though this could be checked in more detail).

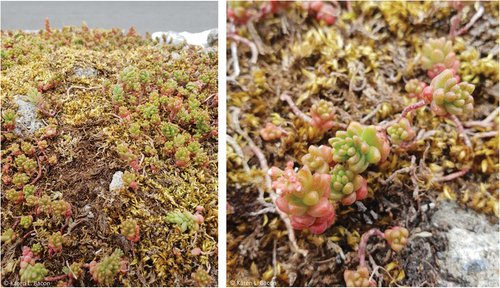

Species name:

Sedum sp (unclear which species)

Species name:

Equisetum sp; a type of horsetail

Species name:

This is a bryophyte; a type of moss.

We are more interested in flowering plants in this session, but feel free to try to assign a better classifications to either of these species. The horsetail was found in a damp, grass-rich meadow.