ABSTRACT

This paper addresses a call for teachers to promote students’ knowledge of criteria and standards within curriculum domains for self-monitoring and improvement purposes. We present the case for students to develop, as part of their learning in content areas, the evaluative knowledge and expertise of the type that teachers bring to the classroom. The aim is to reduce trial-and-error learning by introducing approaches to systematically lessen student dependence on the teacher as the sole or primary source of feedback. In making the case, we draw on a range of salient, empirical projects conducted from 2005–2016 to illustrate key ideas for embedding criteria and standards into practice using what we refer to as ‘an inquiry mindset’ for teachers and students. Four enabling conditions to develop students’ evaluative expertise are proposed: (1) teachers’ assessment identities—dispositions; (2); students’ assessment identities; (3) the role of artefacts; and (4) social moderation. While learning and assessment are structured within the curriculum, taken-for-granted institutional practices, and policy fields, ‘assessment as critical inquiry’ recognises that teacher and student assessment identities, the associated assessment artefacts and opportunities for focussed discussion on the meaning of criteria and standards can work to either support or inhibit teaching and learning.

Introduction

In 1987, Rowntree posed a historic assessment question through the title of his book: ‘How shall we know them?’. In this paper, we address Rowntree’s question for teachers as well as redirecting the question to how shall students come to know themselves as learners. Rowntree’s question opens the way to consider assessment as an inquiry into student learning, as proposed by Delandshere (Citation2002). Working in the US context, Delandshere was looking for ways to address the increasing focus on measurement of learning outcomes for accountability purposes which can equate to progressing through a curriculum, rather than attending to the actual learning needs of students. This approach involved understanding what is to be known within the curriculum as well as what it means to know. In this paper, Rowntree’s question and Delandshere’s proposal to consider assessment as inquiry are used to investigate how characteristics of quality, and specifically criteria and standards, can be embedded in teaching practices intended to develop students’ evaluative experience and expertise.

We use the term ‘criterion’ in reference to ‘a distinguishing property, or characteristic of any thing, by which its quality can be judged or estimated, or by which a decision or classification may be made’, and ‘standard’ in reference to ‘a definite level of excellence or attainment, or a definite degree of any quality viewed as a prescribed object of endeavour or as the recognised measure of what is adequate for some purpose, so established by authority, custom, or consensus’ (Sadler, Citation1987, p. 194). We discuss ‘embedding’ criteria and standards in teaching practice. This is a purposeful use of the word ‘embedding’ to refer to the state of being enclosed or surrounded (Merriam-Webster dictionary, Citation2018, n.p.). When criteria and standards are ‘embedded’ in practice, they are surrounded by other ways of working that support their functioning within the curriculum.

In our argument, we straddle two conceptualisations of curriculum, perceived as dichotomous. One is the view of curriculum as encapsulating the historically accepted and valued domain knowledge (Young, Citation2014). The other is a view of the curriculum as developing future competencies and capabilities as necessary ways of knowing and being. Both views are focussed on the connection between curriculum and learning, and the relationship between teachers and students, albeit from different epistemologies. We straddle these two perspectives through the collaborative exploration of criteria and standards between teachers and students, which has been described in Boomer’s (Citation1992) model of negotiation as a necessary stage of learning. However, we also acknowledge that there are curriculum-specific literacies such that seemingly common terms are deeply contextualised, requiring students to successfully negotiate the meaning of assessment within each subject (Wyatt-Smith & Cumming, Citation2003). Teachers translate ways of knowing, doing and being within a curriculum domain for students. While this involves content knowledge, it also involves developing expertise in the fluent use of language in ways that are accepted and recognisable within the curriculum. Both content knowledge and control of language in use are therefore necessary to achieve a fine performance.

The argument that we are presenting in this paper is not one in support of attempts to wholly prespecify or anticipate all criteria relevant to a future appraisal. Instead, our interest is in how to enable students to be better learners and how teachers can build in the explicit provision of opportunities to develop students’ evaluative expertise and experience over time. In addition, our argument is based on the premise that evaluative expertise will look different across curriculum domains but that the basic principles for developing this expertise remain the same. Sadler (Citation1989) described students’ evaluative expertise as ‘the capacity to monitor the quality of their own work during actual production’ (p. 191). Since then, authors have described pedagogic practices that develop students’ evaluative expertise to assess their own writing (Hawe & Dixon, Citation2014), or evaluative judgement in higher education assessing the work of self and others (Tai, Ajjawi, Boud, Dawson, & Panadero, Citation2018). We propose that to reduce trial-and-error attempts in students’ efforts to produce ‘good work’, they need to be surrounded by practices and artefacts that develop such experience and expertise relative to a curriculum domain. This involves developing students’ knowledge of how to evaluate or self-assess their own work against stated referents, and expertise in recognising quality and applying this in goal-setting and self-monitoring. Assessment is thus a process in which both teachers and students ‘see’ and ‘use’ criteria to inquire into and improve learning.

In this paper, we address the question: What are the enabling conditions for student learning and teachers’ work whereby teachers share and negotiate criteria and standards with students to develop their evaluative expertise for improvement purposes? Additionally, we explore teaching practices that can be adapted across curriculum domains in which teachers share or download their evaluative expertise and develop students’ evaluative experience. In the discussion we draw on a range of salient, empirical projects we have conducted over the period 2005 to 2016 to illustrate key ideas about the enabling conditions for integrating criteria into pedagogic practice. This is a purposeful focus on criteria being embedded in meaningful tasks that engage students in the collaborative inquiry of the criteria and what quality looks like in the knowledge, skills and artefacts of a curriculum domain.

Transparency of assessment practices and evaluative expertise

Within the literature, developing students’ evaluative expertise has been related to assessment as a ‘transparent’ process that promotes student learning (Jonsson, Citation2014). According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary ‘transparency’ can be taken to mean ‘free from pretense or deceit’, ‘easily detected or seen through’, and ‘readily understood’ (Citation2018, n.p.). In the educational research literature, transparency has been related to fairness in primary and secondary school assessment practices (Murillo & Hidalgo, Citation2017; Tierney, Citation2014), engendering trust in college screencast feedback on written texts (Vincelette & Bostic, Citation2013), and motivation for students to evaluate their own work and develop self-regulatory skills (Clark, Citation2012). For example, Vincelette and Bostic (Citation2013) described the college instructor’s use of video to record their thinking as they read through student work. This openness of teaching practice was said to support student metacognitive strategies including self-assessment. Other researchers have associated a lack of transparency of assessment processes with student test anxiety (Vogl & Pekrun, Citation2016).

However, concerns about transparency have been raised when efforts for transparency conflict with other efforts for fair and inclusive practice. For example, Thrupp and White (Citation2013) provided an example where ‘enthusiasm for transparency seemed to have got out of hand … In one classroom we found a wall display that made individuals who were below or well below stand out like a sore thumb’ (p. 22). The authors were describing the use of data walls in primary (elementary) and intermediate school classrooms where students with lower performance in the National Standards categories (reading, writing and mathematics) were clearly identified, potentially conflicting with issues of student wellness or rights to privacy. In another example, Graham, Tancredi, Willis, and McGraw (Citation2018) explained how efforts to support secondary school students through the provision of fine-grained detail on an English assessment task sheet actually overloaded students, resulting in disengagement and lack of understanding of the requirements of the task. Torrance (Citation2007) associated this form of transparency with instrumentalism ‘where assessment procedures and practices come completely to dominate the learning experience, and “criteria compliance” comes to replace “learning”’ (p. 282). In efforts to help students to succeed, teachers’ overly detailed specifications can take a reductionist view of learning. They can then limit students’ agency in their learning and convey the understanding that criteria and standards function primarily as regulatory checklists. Bearman and Ajjawi (Citation2018) take this position, contesting claims to the transparency of written assessment criteria and the hidden assumptions of, for example, shared meaning, that can impede learning and act to control behaviour. The challenge presented by these critiques of transparency is to find the balance between over-specification of criteria on the one hand, and on the other, the systematic build over time of students’ evaluative experience and expertise in ways responsive to students’ learning needs. Ultimately, the intended goal is to develop students’ knowledge of how to discern the features of quality within the curriculum in their own and others’ work and use this to improve their work and establish learning goals.

Inquiring into the deep structures of judgement-making

Although several writers have addressed the issue of whether the comprehensive prior specification of criteria is necessary or even desirable, considerably less attention has been given to whether language can be used to capture all the influences on an actual appraisal. In his discussion of standards as verbal descriptors of quality, Sadler (Citation1985) acknowledged that judgements can be, and are routinely, made in the absence of stated expectations of quality. Typically, they are informed by prior evaluative experience. Further, he provided three reasons as to why it is difficult to comprehensively list all criteria relevant to an appraisal prior to undertaking the appraisal. His stance is based on the premise that axiological values may, in some instances, override criteria. His first reason was that many of the terms used to construct criteria lack distinct boundaries. He described these as ‘fuzzy’ (p. 287). To illustrate, he referred to the use of value-laden terms such as ‘good work’, and ‘consistent use’. Criteria that prescribe measurable features of say a hard hat as required for use in mining, or criteria associated with specific identifiable tasks such as ‘turn on the motor’, are less open to interpretation. They are less ‘fuzzy’ than others that incorporate more subjective terms.

Sadler’s second reason was based on the argument that ‘the universe of human discourse is not coextensive with the universe of human experience’ (Sadler, Citation1985, p. 294). Thus, there is always a possibility that other previously unanticipated qualities may need to be considered in a judgement. This occurs when criteria are latent, emerging in the act of appraising the performance. When this occurs, the anticipated criteria may not always be wholly sufficient or appropriate to all possible responses. Third, Sadler described criteria as ‘a matter of interpretation and semantics and not, strictly, of logic’ (p. 290). Here he was referring to the abstract quality of criteria which are interpreted through use and experience with various events such as assessment practices, types of assessment, and the content of the assessment. This occurs as the terms used to capture criteria have the meaning ascribed to them through use in contexts, including school and curriculum contexts.

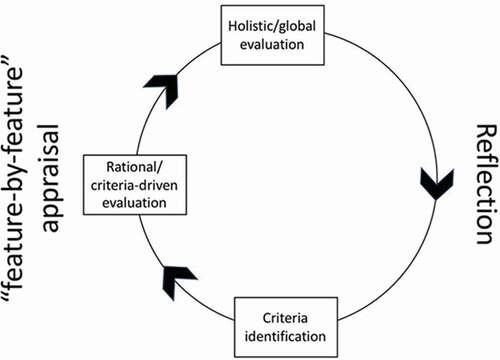

Based on these three reasons, Sadler (Citation1985) argued that while criteria can support ‘feature-by-feature appraisals’ (p. 291), they may not comprehensively capture all considerations in forming a judgement. Similarly, listed criteria do not, in and of themselves, make explicit how they apply or combine in particular cases. It is the global or overall judgement of students’ work that leads to reflection on the other criteria that have come into play in the appraisal process. Since criteria are ‘deeply rooted in experience’ (p. 293), it is ‘recognition, not reason, [that] is the primary evaluative act and predates any criteria’ (p. 291). The implication of this is that when the appraisal process involves subjective descriptors of quality, then the appraisal is not framed entirely by criteria; rather, quality is recognised, and this recognition develops with evaluative experience. This means that typically, teachers’ prior judgements carry forward over time and may impact on subsequent judgements. Without definite boundaries for the interpretation of words used in criteria statements across curriculum domains, historic experiences of appraisal can influence each subsequent judgement.

Criteria have been described as being sourced from three distinct categories; those that are explicit or stated; those that are latent or unstated and emerge during the act of appraising a performance, suggested earlier; and meta-criteria, that is, knowledge of how explicit and latent criteria can be combined (Sadler, Citation1985, Citation2009; Smith, Citation1995; Wyatt-Smith & Klenowski, Citation2013). Explicit criteria are those that are recorded and prescribed. Latent or emergent criteria are the previously unanticipated and unspecified criteria which emerge during an appraisal. Sadler (Citation1985) claimed that in the majority of judgements, stated criteria are appropriate; however, he also acknowledged that latent criteria may legitimately come into play in particular cases. The defence of this stance is that experienced assessors know (1) when and how to apply explicit criteria; (2) how to recognise valid latent criteria that emerge during the act of appraising a piece of work, and (3) how to combine the two, aligned to the purpose of the assessment.

This leads us to question: What is the nature and function of criteria? We propose that the act of assessing, whether it be about a decision to purchase a new car, or decide the quality of a performance or a meal at a restaurant, is arrived at initially through an holistic or global evaluation of the object or experience. Next, this judgement is considered, discussed or reflected on, and in that process the particular features or characteristics of quality that are valued come to be identified. At this point, these characteristics can be thought of as criteria-driven evaluation. From the actual experience and reflection, the salient features that informed the judgement become a feature-by-feature appraisal. Some features may have had more bearing on the judgement than others, and the reasons for this become part of the justification of the overall judgement ().

Figure 1. The cyclical nature of the appraisal process in developing evaluative experience (based on Sadler, Citation1985; Smith, Citation1995)

This conceptualisation of appraisal as combining both the stated criteria and reflection of the global judgement to consider latent influences on the judgement includes recognition that the stated criteria may be the sole source of judgement. However, it also recognises that judgements are complex and acknowledges that other factors do legitimately influence judgements on occasions. The cyclical nature of judgement experience means that over time, the combining of explicit and latent criteria are a more realistic account of what actually occurs during the appraisal process. The interaction of explicit and latent criteria has not however been the subject of sustained research to date, with teacher judgement representing a recent and emerging area of research (Glogger-Frey, Herppich, & Seidel, Citation2018). While there has been much theorizing about standards and evaluation/assessment methods (e.g. Stake, Citation2004), empirical investigation of judgement is a different proposition. It is not surprising that this field of research remains in its infancy given the difficulty in probing the deep structures of judgement-making as identified by Phelps in 1989. We do know, however, that context matters. Australian researchers (Wyatt-Smith, Castleton, Freebody, & Cooksey, Citation2003a, Citation2003b) used the terms In-Context and Out-of-Context to characterise the different judgement practices that teachers relied on, if they were both the student’s teacher and assessor of the work to be appraised. If the teacher-assessor knew the student, then it was described as In-Context. When this occurred, the actual criteria used to appraise the work included knowledge of the student through first-hand observation and knowledge or recollection of the quality of prior performances. However, in the cases when the student was unknown to the teacher and the school context and prior teaching before undertaking the assessment was also unknown, judgements shut down to the stated criteria, the assessor’s knowledge of the official curriculum requirements, and the stated task expectations, including defined criteria.

The above view of fixed criteria as anticipatory or provisional requires a disposition to an inquiry on the part of teachers. The expertise required to employ emergent criteria, that is, criteria that emerge in the course of an assessment, highlights the issue of whether or how it is possible, or even desirable, to share criterial knowledge with students. In learning how to discern quality and to improve learning within a curriculum domain, we propose that students should be taught how to use criteria, both stated and emergent as an inquiry into their learning.

Assessment as an inquiry into learning

Delandshere (Citation2002) based her approach to assessment as inquiry in an understanding of learning as participatory and developed with others where the aim is to reach a shared understanding. Through classroom talk and other interactions, such as teachers modelling the thinking processes required to use criteria for self-monitoring including during completion of a task, teachers can offer students powerful support as they learn about quality—what it actually looks like and how to achieve it—and as they learn how to improve their own learning (Black & Wiliam, Citation2018).

In the remainder of this paper, we advance the argument that the development of students’ evaluative experience and expertise is a critical feature of twenty-first-century curriculum and education. To this end, we present the theoretical framing of assessment as inquiry and discuss the enabling conditions under which this can be achieved. Central to the following discussion is the recognition of ‘quality’ within the curriculum: Who defines it? How is an understanding of quality developed? Does understanding of quality occur within a personal or a shared space?

Theoretical framing of assessment as inquiry

In taking a focus on quality, and specifically the recognition of quality, we draw on Lave and Wenger (Citation1991) and Wenger’s (Citation1998) conceptualisation of ‘communities of practice’ in which meaning is acquired through continual participation in a practice. Our discussion focuses on three cohesive devices within a community of practice: mutual engagement, joint enterprise and a shared repertoire of concepts, tools, and terminology. Skilful participation in a practice occurs through increasingly complex engagements in the practice over time. Learning is thus ‘an integral part of generative social practice in the lived-in world’ (Lave & Wenger, Citation1991, p. 35). Learning is a shared enterprise of active participation in which the collective knowledge of the curriculum group is developed.

The artefacts connected with the curriculum act to support learning within the curriculum. Artefacts are the tools of the social practices of the curriculum domain that embody the philosophy and history of knowing, being and doing within the curriculum. However, over time, the philosophy of the practice and thus aspects of practice may become submerged and hidden in the tools, rather than overtly accessible to interrogation and negotiation. Wenger (Citation1998) used the term negotiation to ‘convey a flavor of continuous interaction, of gradual achievement, and of give-and-take’ (p. 53). For example, one way of representing assessment or performance criteria and standards may be as a graduated sequence in a rubric. The vague terms representing gradation in achievement of the criteria and standard come to have meaning for a particular person or curriculum group which is not evident from the word itself, and while taken as a given within a particular group may not be a common interpretation outside of the curriculum or to newcomers to the group, such as, new teachers or students. Once the meaning becomes integral to the practice, it is more difficult to negotiate any changes to the practice.

When meaning is developed through the interrogation of accepted norms and processes of negotiation, identities and practices may be transformed. Identity, as bound in knowledge, beliefs, and feelings related to a perception of role and empowerment, will affect the interpretation and development of practices for each individual and curriculum group. Thus, practice and identity may change, often innovatively and creatively, as the result of exposure to different artefacts or activities, and this may be different for each individual involved in the practice (Lave & Wenger, Citation1991). Eisenhart (Citation1995) stated that ‘identities can be claimed, modified, rejected, or ignored; they can be developed to a high level of expertise or left unrealized and undeveloped’ (p. 5). Thus, teachers or students can likewise choose to adopt the (assessment) practices of a curriculum group, forming an identity of belonging to that group and its associated practices. In this process, historic ways of working and understanding roles in assessment practices may be transformed through exposure to new situations or concepts, and through active engagement in processes of negotiation of meaning within the group. The recognition of a practice as a shared activity strengthens identity within the practice and thus the practice itself. On the other hand, teachers and students can reject the roles expected of them in a practice. For example, students can resist becoming involved in practices that require them to self-assess or provide feedback to peers (Harris, Brown, & Dargusch, Citation2018). Looney, Cumming, Van Der Kleij, and Harris (Citation2018) have described teacher assessment identity as being more than curriculum knowledge and skills:

They may have knowledge of what is deemed effective practice, but not be confident in their enactment of such practice. They may have knowledge, and have confidence, but not believe that assessment processes are effective. Most importantly, based on their prior experiences and their context, they may consider that some assessment processes should not be a part of their role as teachers and in interactions with students. Teachers can, quite literally, have mixed feelings about assessment. (p. 14)

Xu and Brown (Citation2016) described the construction of teacher assessment identity as a dynamic process that is consequential to learning. The authors did not make a claim for an ‘ideal’ ‘assessment identity’. Instead, their position is that teachers who understand themselves as assessors are more likely to reflect on their assessment practices, and so are open to consider new ways of working as these are introduced. This theorising similarly applies to students developing an identity within assessment practices. Research (e.g. Gao, Citation2009; Peterson & Irving, Citation2008; Remesal, Citation2009) has shown that students are aware of their own and teachers’ identities and purposes about assessment. For example, Gao (Citation2009), presenting a case study of high-achieving girls in a Hong Kong secondary school, found that some students saw assessment as the role of the teacher, resisting practices such as self-assessment. Peterson and Irving (Citation2008) conducted focus groups with 41 Year 9 and 10 students from four New Zealand secondary schools. The authors found that students perceived teachers to be accountable for assessment outcomes, with the main purpose of assessment being to provide feedback to assist their learning.

A key message relevant to this discussion is the necessity of dialogue between teachers and students about assessment. Remesal (Citation2009) presented Spanish primary/elementary students’ conceptions of classroom assessment practices, reminding that assessment may be a disempowering experience for students when they have no input into any aspect of its construction. In studies of formative assessment by Harris, Brown, and Harnett (Citation2014, Citation2015) it was found that students can develop an awareness of their identity as assessors if they perceive feedback as constructive and helpful for their learning. The authors also found a narrowing of students’ conceptions of assessment on entering high school (Harris, Harnett, & Brown, Citation2009).

The conceptual framing of identity, adopted in this paper, is used to provide insight into how teachers and students may work towards acquiring a shared understanding of criteria and standards during teaching and learning, and the role artefacts may play in illustrating criteria within the curriculum. For teachers and students to develop a shared understanding of criteria and standards, they need to understand what ‘good work’ looks like in the sense of a holistic appraisal and in terms of a criteria-driven appraisal. Opportunities need to be identified where the meaning of criteria, and how this appears in different responses can be actively explored and negotiated to promote identities for both teachers and students in assessment practices across different curriculum domains.

The enabling conditions for including students in assessment practices

Four enabling conditions are proposed to support the embedding of criteria into pedagogic practice. These conditions connect teacher and student assessment identity encompassing their knowledge, skills, beliefs and feelings (Looney et al., Citation2018) to their ways of working in curriculum assessment practices (Xu & Brown, Citation2016), and thus the opportunities for students to develop evaluative experience as core to their learning within the curriculum. The conditions include how particular artefacts (such as exemplars and commentaries) and practices (such as social moderation) have been found to support and promulgate an understanding of criteria among teachers and students as they use evidence to inquire into learning. The four conditions are (1) teachers’ assessment identities; (2) students’ assessment identities; (3) the role of artefacts; and (4) social moderation as building judgement experience and expertise (see for an overview of illustrative features of assessment as inquiry in school-based and standards-referenced assessment mapped to the four enabling conditions).

Table 1. Illustrative features of assessment as critical inquiry in school-based and standards-referenced assessment

Description of the conditions is supported by illustrative examples of teacher talk drawn from three research projects conducted by the authors in Queensland, Australia with teachers from the middle years of schooling (Years 4–9, students aged 9 years to 14 years) across the years 2005 to 2016. This phase is a system of standards-referenced assessment in which teachers design the teaching program based on state or national curriculum, design and judge assessment, and participate in moderation discussions with other teachers to determine the consistency of their judgements (for a fuller description of this standards-referenced system, see Brown, Lake, & Matters, Citation2011; Klenowski & Wyatt-Smith, Citation2010; Wyatt-Smith, Klenowski, & Gunn, Citation2010). Thus, the sociocultural context described in this paper is related to that of standards-referenced assessment in a system of school-based assessment. Here we employ an understanding of ‘sociocultural’ as a theory of learning which involves learning as a mutually constitutive sense-making process through discussion, negotiation and the sharing of resources (Rogoff, Citation1995). Within a system of school-based and standards-referenced assessment, there are particular knowledges, skills, beliefs and values about assessment that impact on how assessment is understood and enacted, in terms of, for example, the role of teachers and students, and of standards. This in turn impacts on the formation of an identity, or specifically an assessment identity within this practice. It is acknowledged that teachers and students can take on multiple identities in multiple spaces, but our concern is with the particular sociocultural context of school-based and standards-referenced assessment from which we draw our illustrative examples.

School-based assessment in the Queensland schooling system refers to the delegation of ‘a number of responsibilities to schools with respect to the summative evaluation of students’ achievements’ (Sadler, Citation1986, p. 59) within guidelines provided by the Queensland Curriculum and Assessment Authority (Citation2019). In this context teachers take on roles as designer, teacher, assessor and moderator, drawing on their knowledge of curriculum, assessment practices and processes, and their understanding of the standards within the curriculum domain; students can be viewed as apprentices who are learning what the standards look like within the curriculum domain. For example, a survey conducted by Brown et al. (Citation2011) into the conceptions of assessment purposes of Queensland primary/elementary and secondary teachers found a high degree of similarity among the two groups of teachers. Their findings indicated Queensland teachers’ acceptance of their role as assessors and their ‘responsibility for improving school outcomes and quality’ (p. 218), particularly when working with quality assessments that provided information perceived to be valid for student improvement. In their conclusion Brown, Lake and Matters identified the need for ‘corroborating evidence for these interpretations through other means (e.g., interviews, observations of practice, and assessment samples)’ (p. 219). The following three studies add qualitative data that interrogates teachers’ and students’ use of criteria and standards in judgement-making and as embedded in dialogic practice.

The Standards-driven reform project (2006–2009) funded by the Australian Research Council (LP0668910) involved empirical research with 320 Middle Years teachers (Years 4, 6 and 9) across 120 schools over the duration of the study (for further description of methods see Adie, Citation2013; Adie, Klenowski, & Wyatt-Smith, Citation2012; Connolly, Klenowski, & Wyatt-Smith, Citation2012; Wyatt-Smith et al., Citation2010). The project examined teachers’ judgement-making and moderation discussions to determine the influences on teachers’ judgements and the contribution of moderation discussions to the development of shared understandings of criteria and standards within English, Maths and Science. Data were gathered through a survey to gain an initial understanding of participants’ knowledge of moderation; think-alouds during the process of judgement-making; observations, audio recording and/or videotaping and screen capture of teachers’ talk about student samples of work as they used stated standards to analyse the characteristics of the work during moderation; semi-structured interviews with focus teachers (n = 60) before and after their involvement in a moderation meeting. The focus teachers were among those who had implemented and graded the assessment, and were nominated by the school or through self-selection to participate in moderation. The interviews probed (1) characteristics considered in the initial judgement decision taken prior to the moderation meeting, (2) whether their decision remained the same (confirmed) or changed as a result of moderation; and (3) their perspectives of the moderation processes. The survey data were analysed using SPSS with cross tabs for variables including years of teaching, gender, school type/setting, the model(s) of moderation used and the nature of the samples of student work assessed against the standards. Analysis of qualitative data occurred through a process of constant comparison (Glaser & Strauss, Citation1967; Silverman, Citation1993) to identify themes and reveal similarities, differences, patterns and consistencies of meaning, and the hierarchies that influenced teacher judgements within this standards-referenced system.

The Meeting in the Middle project (2005–2006) involved 273 teachers across 107 schools. The project examined literacy and numeracy practices in the middle years of schooling. The focus of the project was to increase teachers’ knowledge and understanding about best practices in literacy and numeracy assessment, curriculum and teaching instruction for their particular middle years of schooling curriculum contexts. This project investigated the ‘fuzziness’ of human judgements based on standards and identified the use of exemplars and teachers’ written accounts of their judgement-making (cognitive commentaries) to enhance consistency in judgement decisions. Data were collected through a survey, recorded online meetings with teachers, and analysis of collected assessment tasks, student work and teacher judgements (for further description of methods see Wyatt-Smith & Bridges, Citation2007; Wyatt-Smith, Bridges, Hedemann, & Neville, Citation2008). Over the year of the Project (2005), classroom teachers engaged in professional learning about the design of quality assessment tasks and the relationship between curriculum literacies/numeracies and curricular knowledges in the learning areas, and applied this knowledge to their classroom practices. Integral to this professional learning was an appreciation of what students brought to the learning experience, not only from their prior classroom learning but also from the communities in which they lived. Teachers reflected on and discussed ways of aligning curriculum, pedagogy and assessment; considered the desired knowledges and capabilities they wished students to develop; and generated and revised assessment tasks and activities. Teachers analysed the literacy/numeracy demands as well as the curricular knowledge demands of their assessment tasks. They then developed task-specific criteria and standards that related to both curricular knowledges and curriculum literacies/numeracies. The criteria and standards descriptors assisted teachers to identify the features or characteristics of performance that they needed to teach to enable students to succeed at the task. In addition, teachers provided judgements on student work that were based on evidence from shared understandings of explicitly stated standards and criteria. Teachers used the standards specifications to provide a rationale for assigning grades; check for individual consistency in judgements; and communicate judgement decisions to students, other teachers and parents/caregivers.

The Dialogic Feedback project (2016) was an in-depth study of how student agency is supported or inhibited in one-to-one teacher-student feedback conversations. The project involved six teacher-student pairs in three school locations across a range of written and performance assessments in English, Science and Physical Education. The project produced a conceptualisation of dialogic feedback and new coding frameworks to capture dialogic feedback interactions. Teacher-student feedback conversations were recorded and analysed to provide an in-depth coding of interactions. In addition, the videoed recordings were played back, first to the teacher, then to the student with each participating in a video-stimulated recall (VSR) audio-recorded interview in which they paused the video at points in the conversation they identified as salient to them. Analysis of the data examined the alignment of teacher and student pauses and the content of their discussions (for further description of methods see Adie, Van der Kleij, & Cumming, Citation2018; Van der Kleij, Adie, & Cumming, Citation2017, Citation2019). The findings identified how such reflective practices can increase teacher awareness of student learning needs and the social aspects of assessment, and can provide a way for students to voice their perspectives of their learning needs.

Teachers’ assessment identity

Teachers’ assessment identity encompasses their curriculum and pedagogic knowledges as well as their beliefs, feelings and perception of themselves and their role as an assessor, and their beliefs about the relationship between students, learning and assessment (Looney et al., Citation2018). An assessment identity influences how teachers understand criteria and related practices such as ownership, negotiation, and stability. Teachers can perceive assessment as an isolated activity (Elwood & Murphy, Citation2015) with themselves as owners of criteria, where sharing criteria with students is akin to providing the answers to students in a test. We take a different position. We suggest that teachers who approach assessment as inquiry will engage in pedagogic practices that include sharing their knowledge of criteria with students in efforts for students to fully engage and understand themselves as learners within a curriculum domain. The teachers’ critical inquiry into knowledge and knowing within a curriculum commences at the planning stage when teachers come together and share, negotiate and agree on what they are looking for in students’ work as the end product of a teaching episode. This practice has been identified as front-ending assessment (Wyatt-Smith & Bridges, Citation2007) and includes the purposeful alignment of curriculum and assessment. ‘Front-ending’ assessment is a term that captures the conceptualisation of the Assessment Reform Group (2002) who identified the need for teachers to consider strategies for ensuring students understand criteria in their planning. Such processes are also described as constructive alignment (Biggs, Citation2003) and backward design or mapping (Wiggins & McTighe, Citation2005). The purposeful use of front-ending is to focus on assessment as a first consideration in the planning process, looking forward to next stages in the teaching-learning cycle. In this process, teachers start with a notion of the expected characteristics of quality in student work. A preliminary set of criteria are then identified with these being connected to the curriculum and learning objectives. The development of exemplars by teachers or previous student work samples are used to identify different examples of the criteria in action. In most assessments, this will involve conversations about how elements in the assessment combine to demonstrate the criteria, and then recording decisions through annotations (Adie & Willis, Citation2014). It also involves teachers in discussions of how the purpose of the assessment is met, which is the judgement at the holistic level.

In an Australian large-scale study of teacher judgement practices (Standards-driven reform, Klenowski & Wyatt-Smith, Citation2010; Wyatt-Smith et al., Citation2010), it was shown that teachers drew together their knowledge of the curriculum as they had taught it, their school context, the students’ work, and the assessment criteria and standards as evaluative experience. Criteria and standards provided one of a number of information sources that teachers considered when they were looking at student work. For this reason, teachers’ critical and collaborative analysis with colleagues of the assessment demands associated with learning must be an essential aspect of the planning process. Clarifying assessment expectations was critical to the pedagogic role of assessment. The teacher’s understanding of evidence as this relates to quality, interrogated and developed through collegial conversations, enabled the teachers to sharpen their pedagogic focus on features of quality. It was through the collaborative inquiry of teachers, both experienced assessors and novices, into the meaning of criteria and standards within the curriculum domain, that the identity of the teacher developed as one whose work is embedded in a system of standards-referenced assessment. This included the pedagogic practice of using assessment to inform teaching and progress learning (Black & Wiliam, Citation2018).

In a further large-scale study of 107 schools in Australia (Meeting in the Middle, Wyatt-Smith & Bridges, Citation2007; Wyatt-Smith et al., Citation2008) teacher inquiries into assessment practices and processes were conceptualised as the way teachers needed to explore and negotiate the fullness of the meaning of criteria: How do criteria connect to particular curriculum areas, to the learning and teaching program, to the standards that will be applied to judge the work, and to the literacy and numeracy requirements of assessments? Teachers noted the consciousness-raising effects of these analytic processes on their pedagogy with comments such as the following from a mathematics teacher: ‘It very much makes you aware of what I am covering. Am I catering to all the students? Am I delivering all the material?’ (Wyatt-Smith & Bridges, Citation2007, p. 61). Here the mathematics teacher was commenting specifically on the literacy requirements within the mathematics criteria, and reflecting on whether and how all of their students were being supported within their teaching to understand the mathematical terminology and semiotics to successfully learn a topic and to show their learning. When criteria are situated in a learning and teaching assessment ecology it can lead to a change in practice, new knowledge and perspective of their work in a curriculum domain.

In addition, teachers can develop an assessment connoisseurship that moves beyond the stated criteria, to encompass meta-criteria when necessary. Elwood and Murphy (Citation2015) described ‘new cultural scripts’ for school assessment practices where ‘understanding is achieved through individuals appropriating shared meanings through discussion and negotiation’ (p. 187). Crucially, this requires rethinking the taken-for-granted ways of assessing within the curriculum and the relationships between teachers and students in assessment, to assessment as an interactive and dialogic practice that is mutually constitutive. Wenger (Citation1998) discussed mutuality of engagement as ‘the ability to engage with other members and respond in kind to their actions’ (p. 137) which was the basis for the formation of an identity within a practice. The contribution of participants, in this case, the teacher and students, will differ according to their experience within the practice, in this casethe curriculum and associated assessment practices. Through interactive and dialogic practice, teachers and students contribute to the understanding of the other within the practice, that is, the practice is mutually constitutive. Teachers recognise how to provide better support for students to engage in assessment, and students develop an understanding of assessment, standards and criteria in relation to their learning. In this practice, the shift for the teacher is to create the context that will enable students to participate in the assessment as a shared enterprise, rather than assessment as a process that is imposed on students (Boud & Soler, Citation2016; Elwood & Murphy, Citation2015). Brookhart (Citation2016) used the term co-regulation of learning to refer to these social practices and provided a model specific to classroom assessment practices that illustrates how teachers and students may participate in these practices.

When teachers’ assessment identity encompasses the knowledge and skills to embed criteria and standards in their work and share these with their students, as well as value and believe that these practices are fundamental to student learning, then teachers adopt different understandings of control and authority in the classroom. The teachers’ assessment identity shifts to one where students become insiders to assessment knowledge, traditionally the domain of the teacher. When this shift occurs, assessment identity becomes an enabling condition.

Students’ assessment identity

Students’ assessment identity encompasses their curriculum content knowledge and skills as well as their beliefs, feelings and perception of themselves as learners, and their role in assessment practices. For instance, students can identify as ‘being a good student’ or they can identify as a learner who inquires into their own learning processes to understand their strengths and weaknesses, and so where to direct their efforts in learning improvement. Students’ inquiry into the knowledge and knowing in a curriculum domain includes engaging in discussions and activities to reach a shared understanding of the purpose of the assessment, how their learning goals are situated within the activity, and the basis on which judgements will be made; and then applying this understanding to the feedback that they receive to improve their work, and progress or adjust their learning goals. Sadler (Citation1989) stated that ‘It is insufficient for students to rely upon evaluative judgments made by the teacher’ (p. 143); thus, requiring students’ critical engagement in discerning the quality of their work and the criteria and standards against which their work is being judged. Baird, Hopfenbeck, Newton, Stobart, and Steen-Utheim (Citation2014) reiterated this view, stating that ‘The focus is on the learner actively being part of the assessment process through understanding what is being learned, the quality of learning required and the ability to monitor performance against this’ (p. 41). Demystifying assessment practices for students supports students’ understanding of quality as framed within the curriculum and the associated assessment purpose, criteria, standards, learning goals, feedback and self-and peer-assessment.

Research has identified the value of students co-constructing criteria with their teachers (e.g. Andrade, Du, & Wang, Citation2008; Bourgeois, Citation2016), constructing their own criteria (e.g. James & McCormick, Citation2009) or de-constructing criteria (e.g. Torrance, Citation2012). The Meeting in the Middle project (Wyatt-Smith & Bridges, Citation2007) also found that students were much better placed to self and peer assess if they had been engaged in co-developing the criteria with the teacher. The teacher and the students published the criteria in the classroom, and the students looked to see how the criteria, as an anticipatory set, were being applied in their work. The students used the criteria to identify areas for improvement. The teachers reported that class discussions and activities related to developing knowledge of the criteria and standards focussed student learning. Student ability to use criteria was related to the expertise of the teacher in knowing and understanding the curriculum and assessment requirements. The following statement is illustrative of teachers’ comments across the curriculum areas:

I think to a certain extent that we’ve empowered students in the learning process because there’s no secret teacher’s business anymore in terms of what the expectations are, that students are becoming very au fait with the criteria and being able to apply them to their own work(Wyatt-Smith & Bridges, Citation2007, p. 61)

Through a process of demystifying criteria, teachers found that students were able to engage in peer- and self-assessment with improved performance for some of the most at-risk students in the schools evident. Several other studies have identified how the teacher’s role can extend to developing students’ self-regulatory skills. Self-regulated learners are mindful of their thinking, motivations and behaviour as they are learning and take ownership of their learning (Winne, Citation2018). We argue that to do this in an informed manner requires knowledge of quality. This practice has been referred to as developing students’ evaluative skill/experience/expertise (Sadler, Citation1989; Smith, Citation1995) or, more recently, their evaluative judgement (Tai et al., Citation2018). Tai et al. (Citation2018) define evaluative judgement as ‘the capability to make decisions about the quality of work of oneself and others’ (p. 471). Teachers can support the development of this knowledge and skills by supporting students’ efforts to understand criteria and related learning goals, and what the expected standard of performance looks like. Explicit instruction that embraces the use of examples is required to develop this understanding.

Involving students in dialogue including dialogic feedback conversations and encouraging feedback from multiple sources—self, peers, grades, technologies—can support student recognition of quality (Carless, Citation2013; Dann, Citation2015; Lyle, Citation2008; Van der Kleij et al., Citation2017). For example, in the Dialogic Feedback study, which investigated teacher-student feedback interactions, one English teacher reflecting on her feedback commented, ‘we’re having more of a two-way conversation rather than me just telling her things. And so here she’s taken what I’ve said but also added … dialogue as an area that she thinks that she has an issue’ (Van der Kleij et al., Citation2017, p. 1102). The point is that recognition by the teacher of a student’s learning need has arisen through dialogue and would, by the teacher’s own admission, have otherwise gone unnoticed. The teacher went on to note that ‘dialogue’ would be addressed in her future teaching. Whether this occurs as a whole class or an individualised or small group lesson will depend on other conversations with other students in the class as well as observations of work. It is the teacher’s assessment methodology that is critical here, that is, how the development of a student’s assessment identity may be facilitated or inhibited through the teacher’s dialogue with students in the teaching episode (Torrance & Pryor, Citation2001).

On the other hand, in the above example, the teacher could have rejected the student’s identification of dialogue as an area of focus, particularly if this did not directly align with the task-specific criteria. For example, Torrance (Citation2012) warned that assessment (and feedback) can also be ‘deformative’ with a negative impact on learning. The complexity for teachers is at what point to share what level of knowledge of criteria with students. This includes teachers’ identification of criteria, how these combine and contribute to the overall judgement and the use of artefacts in classroom talk and other interactions regarding assessment. Approaching assessment as an inquiry into learning, a process of dialogue and negotiation, and a process involving adjustment and readjustment of teaching plans to meet each student at their point of need is necessary to address the possible deformative impacts of feedback and other assessment processes. Developing a student’s assessment identity includes teaching relevant curriculum knowledge and skills so that students can inquire into their learning and evaluate their learning progress, actively using this data to establish learning goals. Such practices can support students’ participation in a standards-referenced assessment system.

Artefacts

Carefully selected exemplars chosen to illustrate expected features of quality can serve to ‘show’ what quality looks like, demonstrating ‘good work’ in a curriculum domain. They can also support teachers’ and students’ dialogue and appraisal about how these features combine and form configurations or patterns across criteria, the vital point being that criteria and standards can be met in a variety of ways to form an overall judgement. Further, when exemplars are annotated by teachers during their planning discussions, they provide a representation and a reminder of teacher thinking about how they could focus their pedagogy on aspects of learning that may represent barriers to student progress at points in time.

Exemplars, as concrete representations of quality, are of paramount importance in developing students’ recognition of fine performances and hence, their understanding of how criteria apply to curricular learning and performance. To develop students’ evaluative expertise, they need much more than a checklist of criteria; they actually need to be inducted into how teachers assess and judge student work, as well as opportunities to engage in a collaborative critique of the criteria. In that, it is critical that teachers share examples of student work and show what is involved in the next-step learning improvement pathways for students. The interaction of talk and text around criteria in classrooms, including modelling of how to actually use the criteria to inform improvement efforts, is critical.

In addition, we have found that during the judgement-making process, the construction of a commentary of how teachers have arrived at a particular judgement of quality using the criteria, keeping open the prospect of factor X for what they had not anticipated in arriving at the judgement, is a necessary process. We call this explanatory statement, a cognitive commentary (Klenowski & Wyatt-Smith, Citation2014) which is an explanation of how an overall judgement of the quality of student work is reached ().

Figure 2. Example of a year 5 history cognitive commentary from the Meeting in the Middle project (Wyatt-Smith & Bridges, Citation2007, p. 8)

In commentaries such as this, teachers identified the elements that came to the forefront as they appraised student work. The commentary can be attached to the work sample and used by teachers to anchor the judgement to a standard of quality. Cognitive commentaries can also be shared with students to convey how the strengths of a particular piece and the limitations of a piece combine in overall judgement. The commentary and authentic work samples together can enhance efforts to show decision-making, both in how the piece of work is produced, and in how it is appraised. This includes how the criteria contribute to the overall judgement, including any latent criteria that have been brought into play, and how they sit in relation to the overall purpose of the assessment.

While exemplars can play an important role in supporting student understanding and use of criteria, they can also limit understanding. In the Australian Standards-driven Reform project, the types of annotations on exemplars were found to restrict understanding of the variety of ways in which criteria and standards may be demonstrated (Adie et al., Citation2012). At times the annotated samples of middle school student work focussed teachers’ attention on single aspects of the work and a particular criterion. When this occurred, there was a fixation on the individual criterion, without regard for how other features of quality were evident in the work. In the following example, a mathematics teacher is reflecting how in mathematics, questions can be assigned to a standard, for example a B standard question, rather than the standard being evident through the quality of the response, that is, for example, an A or B standard of response, as well as evident across the whole paper.

I had a chat with one of my other colleagues before and he was saying, “You know, this, this question here, that’s an A standard,” and then he turned the page and showed a B standard and the wording was virtually the same. I had to point out to him that what the standard was showing you wasn’t just for that question but for the whole paper. So, you know, the B standard, to my way of thinking, for both questions, the two answers for both questions were a very good answer, but it was in the other questions where the B standard would have come out, not necessarily just in that one question. (Klenowski & Wyatt-Smith, Citation2010, p. 37)

While statements of criteria, annotated exemplars and related commentaries are useful in developing understandings of quality, social moderation practices provide opportunities for teachers to share insights into their judgements and to review how criteria and standards are applied by colleagues and represented in assessments. As discussed below it is through moderation that teachers develop confidence in their own appraisal processes and related confidence to share this with students as part of their learning in the curriculum.

Social moderation

To this point, we have discussed how criteria and standards can be embedded in classroom talk and practices including collaborative critique and construction of annotated exemplars and accompanying cognitive commentaries. A key additional practice to build a sustainable assessment community in a school is through social moderation that involves bringing teachers together for professional conversations about qualities evident in student work (and in the Queensland context with reference to assessment criteria and standards). This practice supports the development of teachers’ evaluative experience and expertise through inquiry into teachers’ judgements of quality and their use of criteria and standards. In moderation meetings, teachers share samples of their student work, engaging in dialogue and analysis of judgements with a focus on how they ‘see’ quality in the work.

Following is a segment of Science teachers’ talk during a moderation meeting (Standards-driven Reform project) in which teachers were reviewing a write-up of a science experiment report. The stated criteria focussed attention on a particular feature of the report, and not on the practical aspects of doing the experiment. The key question here is whether criteria act as rules for what can be recognised and rewarded.

Teacher 1: … because you’re sticking to that criteria, and then you have to give him an E. But I don’t think that’s reasonable because he’s done a good job in prac [practical] work.

Teacher 2: He’s done a good job, I’m saying that, but you’re given a criteria [sic] and you need to be able to say on the criteria, ‘According to the criteria I mark him like that.’ (Wyatt-Smith et al., Citation2010, p. 69)

This opens the question of which variables apply when making criteria-based judgements. In the case cited, is it reasonable to consider the ‘good job’ that the teacher acknowledges the student as doing, or to only consider the explicit criteria and the response at-hand? What happens when the features of the work being assessed are not mirrored in the stated criteria? In this instance, which was the fairest stance to take, that of Teacher 1 or Teacher 2? The discussion raises the critical issue of when criteria should be strictly followed and when latent criteria come into play, and most importantly, how this knowledge is developed among teachers and with students.

The following segment is from an interview with a Year 6 teacher who had been involved in an online moderation meeting of a mathematics task (Standards-driven Reform project). In this segment, we can hear how the teacher describes her initial reaction to having her judgement challenged, and her decision to consider another perspective.

One of the other (assessors) made a comment that … brought in sort of a different aspect … and made me think. And at first, my initial gut reaction was I’m wrong and I didn’t like that, but, you know, I guess I had to sort of swallow that down, and say, ok well let’s look at it from someone else’s point of view and listen to what she said. (Adie, Citation2013, p. 101)

In this segment, we can hear an openness to pausing before going to a final decision about quality. There is also an interest in listening to how colleagues see the quality—their point of view—and how they talk about quality. This is a desired response which can build a shared understanding of quality in a practice. This form of response was not observed in all moderation meetings where teachers at times became defensive to protect their identity as judgement maker.

In the next example, teachers came together in school-based moderation meetings to share student work for the purpose of reviewing the application of criteria and standards, and more specifically, strengthen their confidence in the fairness and consistency of their judgements. In this context, teacher learning became a shared enterprise; it involved active participation in developing collective knowledge of what criteria mean within a curriculum domain, and related knowledge of how they are applied by members of a school group or year level.

… we really did it one by one. We didn’t just mark one and like go for it. We talked through with each other like ‘Oh, I don’t really know what this is’ then talked it out and justified. … It took us a whole day. … I don’t think we were good enough to look at the standards and say ‘they have this’, the sample and the discussion was much better. (Klenowski et al., Citation2007, p. 19)

Through the moderation discussions, teachers grappled with notions of criteria as either fixed or as illustrative. As one English teacher explained,

you never really understand what they’re [criteria and standards] about until you are grading or you are using them. So, until you see them in operation it’s hard to know, but there is a danger of being too detailed and almost verbose with what you’re trying to do … the standards have to reflect really, it hones in therefore on what it is you’re really assessing. (Klenowski & Wyatt-Smith, Citation2010, p. 34)

In this discussion, the teachers have identified that while criteria and standards as written text appear to be fixed and regulatory, they remain open to ‘the surprise’ or ‘factor X’, which is something that they had not anticipated, for example, a student takes a different approach or a different stance. In English, students’ responses to an essay topic, for example, can be widely varied; while there may be a recognised genre, judgement-making in English (and other areas of the Arts) is generally considered far more subjective than in domains such as mathematics or the Sciences. The purpose of the assessment, articulated by the teacher in the above example as ‘what it is you are really assessing’, is, in fact, the foundation of a judgement. Understanding the purpose of the assessment within the curriculum area, at a deep level, is the focus of teacher discussions and discussions with students. This then leads into conversations on the multiple ways in which criteria can be represented and responses could be formulated. However, this form of discussion is not associated specifically with English and the Arts, as the following extract involving two Science teachers illustrates. In this example, the Science teachers discussed the difficulty of pre-specified criteria and the possibility of other or latent criteria that may surface during an appraisal.

Teacher 1: … what I have found is that it is impossible to design criteria that work all the time and what you need to do is that you need to use them more as a …

Teacher 2: … a guideline?

Teacher 1: … a rough guideline and then you need to see. (Wyatt-Smith et al., Citation2010, p. 68)

The domain of Science is often viewed as objective in terms of defined content knowledge and ways of working. By considering criteria as a ‘guideline’, Teacher 1 was referring to Science as an inquiry process involving reasoning and explanation. The teachers’ discussion lends weight to the argument that criteria and standards provide a guide of valued features and quality, but expertise is also required ‘to see’ the multiple combinations and permutations to arrive at a final appraisal of the work. Further, it shows how it is potentially self-limiting within any curriculum to rigidly adhere to prespecified criteria.

Criteria remain abstract constructs; the notion of learning to see (Kress, Citation2000) is critical to how teachers and students come to use criteria and apply them in learning improvement. The practice of teachers sharing ‘the criteria sheet’ or rubric with students is not necessarily sharing or learning about criteria. Learning to see requires dialogue between teachers and students where they talk and apply criteria in producing work. When the assessment is understood as critical inquiry between teachers and students, knowledge and knowing are perceived not as an acquisition but rather as dialogic and transformative. The practices and processes of assessing are embroiled in the social and cultural acts of learning together and understanding oneself as a learner in a curriculum domain. For students, this involves inclusion in the knowledge of the ‘community’—the knowledge domains being assessed, the language of assessment within a discipline, the use of criteria and standards in judgement practice and in moderation discussions. Student engagement with their own learning processes and the expression of their learning needs can, therefore, extend to the construction or co-construction of criteria with teachers, and the active use of criteria in making judgements of quality, and in moderation-style discussions of why an example of work is representative of a particular quality of work.

Conclusion

This paper aimed to answer the question: What are the enabling conditions for student learning and teachers’ work whereby teachers share and negotiate criteria and standards with students to develop their evaluative expertise for improvement purposes? We located this question within the key issue of how an environment can be created in which conversations about criteria and standards are embedded in teaching and learning within curriculum domains. This moved the discussion beyond a notion of pre-set criteria to latching criteria to learning and teaching, and challenged notions of assessment as the domain of teachers alone. In particular, we proposed that a necessary consideration is what transparency means for classroom assessment practices, in terms of the relationship between teachers and students, the development of evaluative expertise, and the relinquishing of teachers’ authority over assessment by sharing their knowledge of criteria and the processes of judgement-making with students. Kress’ (Citation2000) notion of ‘learning how to see’ signals a response for Rowntree’s (Citation1987) challenge of ‘How shall we know them?’. Teachers and students learn to see criteria as features of quality through talk and text that is an embedded part of classroom interactions, and that is explicitly linked to students’ understanding of themselves as learners and their learning improvement within a curriculum domain. This is the type of interaction that we believe will see the shift from ‘good students’ to students understanding and producing ‘good work’ that involves inquiry, deep thinking and seeing differently.

Further, in this paper, we have positioned assessment as inquiry drawing on Delandshere (Citation2002). Inquiry is used by Delandshere as a metaphor to represent assessment as (1) open and without a delineated outcome; (2) critical, informed through data and evidence; and (3) dialogic in ways that challenge the traditional roles assigned to teachers and students. We build on this to advocate for teachers’ work to develop in students inquiry mindsets. This is where criteria and standards can go beyond simply stated expectations of quality to essential illustrations of quality through exemplars and commentaries. While learning and assessment are structured within the curriculum, institutional and policy fields, assessment as critical inquiry recognises that teacher and student assessment identities, the associated assessment artefacts and opportunities for focussed discussion on the meaning of criteria can work to either support or inhibit performance. Rather than providing tighter frameworks in attempts to promote consistency as a primary goal, we advocate for the development of practices that include teachers and students focusing on the meaning of criteria and so coming to see the criteria together. It is in this way that teachers and students may develop ‘a clearer sense of their own identity as assessors’ (Xu & Brown, Citation2016) within their curriculum assessment context. In a system of standards-referenced assessment, the use of criteria in the classroom needs to be rethought, particularly in relation to teacher authority and assessment. The notion of student engagement in teaching and learning has been conceptualised as a dynamic system of social and cognitive constructs as well as synergistic processes. We have provided four enabling conditions to enhance the teacher–student relationship, and teaching that strives to embed the meaning and practice of using criteria and standards in how students routinely learn on a day-to-day basis.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Claire Wyatt-Smith

Claire Wyatt-Smith is Director of the Institute for Learning Sciences and Teacher Education, ACU and Professor of Educational Assessment and Literacy. Her research engages with significant research, policy and practice matters including standards, validity, reliability, fairness, and teacher and system use of data to inform teaching and improve learning. Her most recent work focuses on evidentiary decision-making, professional judgement and expertise. https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1190-9909

Lenore Adie

Lenore Adie is Associate Professor in Teacher Education and Assessment and Senior Research Fellow at the Institute for Learning Sciences and Teacher Education, ACU. Her research focuses on assessment processes as these contribute to supporting teachers’ pedagogical practices and student learning across all phases of education. She has extensive professional experience working in schools as a teacher and in leadership positions, and in teacher education for over 30 years. https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3874-397X Twitter: @LenoreAdie

References

- Adie, L. (2013). The development of teacher assessment identity through participation in online moderation. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 20(1), 91–106.

- Adie, L., Klenowski, V., & Wyatt-Smith, C. (2012). Towards an understanding of teacher judgement in the context of social moderation. Educational Review, 64(2), 223–240.

- Adie, L., Van der Kleij, F., & Cumming, J. (2018). The development and application of coding frameworks to explore dialogic feedback interactions and self-regulated learning. British Educational Research Journal, 44(4), 704–723.

- Adie, L., & Willis, J. (2014). Using annotations to inform an understanding of achievement standards. Assessment Matters, 6, 112–136.

- Andrade, H., Du, Y., & Wang, X. (2008). Putting rubrics to the test: The effect of a model, criteria generation, and rubric-referenced self-assessment on elementary school students’ writing. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 27, 3–13.

- Baird, J.-A., Hopfenbeck, T. N., Newton, P., Stobart, G., & Steen-Utheim, A. T. (2014). Assessment and learning: State of the field review. Lysaker, Norway: Knowledge Centre for Education. Retrieved from https://www.forskningsradet.no/servlet/Satellite?c=Rapport&cid=1253996755700&lang=en&pagename=kunnskapssenter%2FHovedsidemal

- Bearman, M., & Ajjawi, R. (2018). From “Seeing Through” to “Seeing With”: assessment criteria and the myths of transparency. Frontiers in Education, 3(96), 1–8.

- Biggs, J. B. (2003). Teaching for quality learning at university (2nd ed.). Buckingham: Open University Press/Society for Research into Higher Education.

- Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (2018). Classroom assessment and pedagogy. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 25(6), 551–575.

- Boomer, G. (1992). Negotiating the curriculum. In G. Boomer, N. Lester, C. Onore, & J. Cook (Eds.), Negotiating the curriculum: Educating for the 21st century (pp. 4–13). London: Falmer.

- Boud, D., & Soler, R. (2016). Sustainable assessment revisited. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 41(3), 400–413.

- Bourgeois, L. (2016). Supporting students’ learning: From teacher regulation to co-regulation. In D. Laveault & L. Allal (Eds.), Assessment for learning: Overcoming the challenges of implementation (pp. 345–363). Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer.

- Brookhart, S. M. (2016). Section discussion: Building assessments that work in classrooms. In G. T. L. Brown & L. R. Harris (Eds.), Handbook of human and social conditions in assessment (pp. 351–365). New York: Routledge.

- Brown, G. T. L., Lake, R., & Matters, G. (2011). Queensland teachers’ conceptions of assessment: The impact of policy priorities on teacher attitudes. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(1), 210–220.

- Carless, D. (2013). Trust and its role in facilitating dialogic feedback. In D. Boud & E. Molloy (Eds.), Feedback in higher and professional education: Understanding it and doing it well (pp. 90–103). London: Routledge.

- Clark, I. (2012). Formative assessment: Assessment is for self-regulated learning. Educational Psychology Review, 24(2), 205–249.

- Connolly, S., Klenowski, V., & Wyatt-Smith, C. M. (2012). Moderation and consistency of teacher judgement: Teachers’ views. British Educational Research Journal, 38(4), 593–614.

- Dann, R. (2015). Developing the foundations for dialogic feedback in order to better understand the “learning gap” from a pupil’s perspective. London Review of Education, 13(3), 5–20.

- Delandshere, G. (2002). Assessment as inquiry. Teachers College Record, 104(7), 1461–1484.

- Eisenhart, M. (1995). The fax, the jazz player, and the self-story teller: How “do” people organize culture? Anthropology and Education Quarterly, 26(1), 3–26.

- Elwood, J., & Murphy, P. (2015). Assessment systems as cultural scripts: A sociocultural theoretical lens on assessment practice and products. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 22(2), 182–192.

- Gao, M. (2009). Students’ voices in school-based assessment of Hong Kong: A case study. In D. M. McInerney, G. T. L. Brown, & G. A. D. Liem (Eds.), Student perspectives on assessment: What students can tell us about assessment for learning (pp. 107–130). Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

- Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. New York: Aldine De Gruyter.

- Glogger-Frey, I., Herppich, S., & Seidel, T. (2018). Linking teachers’ professional knowledge and teachers’ actions: Judgment processes, judgments and training. Teaching and Teacher Education, 76, 176–180.

- Graham, L. J., Tancredi, H., Willis, J., & McGraw, K. (2018). Designing out barriers to student access and participation in secondary school assessment. Australian Educational Researcher, 45(1), 103–124.

- Harris, L. R., Brown, G. T. L., & Dargusch, J. (2018). Not playing the game: Student assessment resistance as a form of agency. Australian Educational Researcher, 45(1), 125–140.

- Harris, L. R., Brown, G. T. L., & Harnett, J. A. (2014). Understanding classroom feedback practices: A study of New Zealand student experiences, perceptions, and emotional responses. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 26(2), 107–133.

- Harris, L. R., Brown, G. T. L., & Harnett, J. A. (2015). Analysis of New Zealand primary and secondary student peer- and self-assessment comments: Applying Hattie and Timperley’s feedback model. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 22(02), 265–281.

- Harris, L. R., Harnett, J. A., & Brown, G. T. L. (2009). ‘Drawing’ out student conceptions: Using pupils’ pictures to examine their conceptions of assessment. In D. M. McInerney, G. T. L. Brown, & G. A. D. Liem (Eds.), Student perspectives on assessment: What students can tell us about assessment for learning (pp. 321–330). Charlotte, NC US: Information Age Publishing.

- Hawe, E. M., & Dixon, H. R. (2014). Building students’ evaluative and productive expertise in the writing classroom. Assessing Writing, 19, 66–79.

- James, M., & McCormick, R. (2009). Teachers learning how to learn. Teaching and Teacher Education, 25(7), 973–982.

- Jonsson, A. (2014). Rubrics as a way of providing transparency in assessment. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 39, 840–852.

- Klenowski, V., Adie, L., Gunn, S., Looney, A., Elwood, J., Wyatt-Smith, C., & Colbert, P. (2007, November). Moderation as judgement practice: Reconciling system level accountability and local level practice. Paper presented at the Australian Association for Research in Education [AARE] 2007 Conference: Research impacts: Proving or improving, Freemantle, Australia.

- Klenowski, V., & Wyatt-Smith, C. (2010). Standards, teacher judgement and moderation in contexts of national curriculum and assessment reform. Assessment Matters, 2, 107–131.

- Klenowski, V., & Wyatt-Smith, C. (2014). Assessment for education: Standards, judgement and moderation. London: SAGE.

- Kress, G. (2000). “You’ve just got to learn how to see”: Curriculum subjects, young people and schooled engagement with the world. Linguistics and Education, 11(4), 401–415.