ABSTRACT

Despite the increasing popularity of studies on teachers’ national curriculum adaptations, there is no comparative study elucidating teachers’ adaptations in centralized and decentralized educational contexts through sense-making theory lenses. This paper presents a comparative case study of Turkish and Swedish senior classroom teachers’ curricular adaptations concerning sense-making theory. We get data through non-participatory lesson observations, interviews, and document analysis from two teachers teaching third-grade mathematics in each country (İzmir and Malmö). Findings reveal that both Turkish and Swedish senior teachers frequently extend, replace/revise and omit the mathematics curriculum. Turkish teachers provided extensive evidence about their adaptations and even tried explaining their reasons whereas Swedish teachers perceived the changes they made in the classroom as teaching rather than adaptations, due to different levels of centralization. Additionally, Turkish teachers responded with parallel structures and assimilation to the national curriculum, and Swedish teachers responded only with assimilation. However, a Turkish teacher’s assimilation mediated fewer adaptations while both Swedish teachers’ assimilation mediated more adaptations (extension and replacing/revising). We conclude by drawing implications for research on teachers’ adaptations and sense-making.

Introduction

Although national or local/school level curricula are prepared with great premises in many countries, teachers rarely implement them as they are written. As stated by Drake and Sherin (Citation2006), no curriculum is ‘teacher-proof’, therefore, teachers inevitably make some adaptations (neglect, add or revise, etc.) regardless of their beliefs and experiences during the implementation (Bümen & Yazıcılar, Citation2020; Burkhauser & Lesaux, Citation2017; Fogo et al., Citation2019; Li & Harfitt, Citation2017; McCarthey & Woodard, Citation2017; Troyer, Citation2017). The curriculum adaptation explains the ways teachers make important changes on subjects, activities or the purpose of the lesson (Sherin & Drake, Citation2009). Despite the vast amount of research on curriculum implementation in general, there is still a need for more understanding on teachers’ adaptation in different cultures especially comparing centralized and decentralized countries. Since teaching as cultural practice nests cultural scripts of society and it is difficult to interpret these scripts, cross-cultural studies allow us to recognize and define them, and to investigate assumptions and experiences that cultural insiders often take for granted (Remillard, Citation2019). In a cross-cultural study, the researchers carrying their own cultural scripts provide insight into the case they come from, which assists to develop a cross-case synthesis in the end. In this sense, having a role both as an insider and an outsider, we would like to understand teachers’ curriculum adaptation in centralized and decentralized contexts. Hence, we focused on two distinct educative contexts, Türkiye and Sweden with a cross-cultural viewpoint.

In this study, we view the curriculum as a participatory sense-making process rather than a linear operation of transmitting or resistance (Remillard, Citation2005). The process by which teachers’ previous understandings, cultural norms, and routines influence how teachers emphasize, make sense of, and act on particular components of a curriculum is referred to as sense-making (Coburn, Citation2004). Besides, educational policies are not neutral since they are shaped by various attitudes and beliefs about teaching. In that case, even if a curriculum has a concrete rationale and a plan to follow, its actual implementation (or lack thereof) will be determined by the individual and collective sense-making processes of school personnel (März & Kelchtermans, Citation2013).

We attempted to report on the cases from two countries (Sweden and Türkiye) comparatively through the lenses of the sociological theory of sense-making (Weick, Citation1995) in this study. The countries were chosen as they differ significantly in how the curricula are designed, and because we as authors are both insiders and outsiders in the two contexts. The study is specifically aiming to understand the curriculum implementation process and observe how the teachers adapt the curriculum into classroom practices through planning and teaching in both Swedish and Turkish contexts, the following questions were raised: (1) How does the curriculum adaptation occur in the Turkish and Swedish elementary school contexts? (2) How do the teachers’ individual sense-making mediate their curriculum adaptations?

Despite many studies on curriculum adaptations in the USA (e.g. Burkhauser & Lesaux, Citation2017; McCarthey & Woodard, Citation2017), no comparative study has explored adaptations with sense-making theory lenses. Even though the role of context in using curriculum materials is well-known (Burkhauser & Lesaux, Citation2017), teachers’ sense-making is often underestimated in curriculum adaptation research (Troyer, Citation2017), which leads to the lack of understanding on teachers’ curriculum adaptation across different contexts. As teachers’ sense-making plays a mediating role in determining how they perceive curriculum and what they adopt from it in implementation (Li, Citation2019), sense-making theory lenses can capture the actual processes shaped by the meanings they build. While we know that teachers adapt curricula with their pre-existing orientation towards teaching and learning (Troyer, Citation2017), no comparison has been made in the two countries that differ greatly in both governance arrangements and educational traditions (Curriculum and Didaktik). Moreover, all comparative studies on this topic have examined teachers within relatively decentralized contexts (Ahl et al., Citation2015; Hemmi et al., Citation2018; Remillard, Citation2019; Remillard et al., Citation2016). However, teachers’ adaptations are not linked to only decentralized countries; it is confirmed that teachers make adaptations in highly centralized countries such as Türkiye (Bümen & Yazıcılar, Citation2020; Li & Harfitt, Citation2017; Yazıcılar & Bümen, Citation2019). Therefore, the profile of curriculum adaptations in comparison with centralized and decentralized countries is a matter of our interest. Second, the above-mentioned comparative studies focus on more teacher-curriculum interaction rather than the patterns of adaptation (omitting, extending, and replacing or revising). Since teachers’ adaptations are inevitable (Roth Mcduffie et al., Citation2018), a comparative study of the patterns with a deepening perspective through sense-making theory can also point to fruitful areas for future research. Filling these gaps, this comparative study may reveal findings to play critical roles in taking action on curriculum adaptation and teacher education in both countries. In addition to broadening perspectives on adaptation in different contexts, particularly by comparing centralized and decentralized countries, it may deepen scholars’ and policymakers’ understanding of the conditions for successful ways to encourage their agency to diversify the curriculum.

Theoretical background

Teachers’ curricular adaptations

Teachers are preoccupied with balancing their instructional responsibilities with the demands and limits imposed by local and national governments. Therefore, state-based curriculum-making (as in Türkiye) determines what teachers should, can, and will do with curricular documentation. Nevertheless, various individual factors, such as the teacher’s knowledge, beliefs, and goals, pedagogical competence, perceptions of curriculum and students, tolerance for discomfort, as well as experience and professional identity impact the relationship between teacher and curricular resources (Bernard, Citation2017; Brown, Citation2009; Hemmi et al., Citation2018; Li & Harfitt, Citation2017; McCarthey & Woodard, Citation2017; Remillard & Bryans, Citation2004; Westwood Taylor, Citation2016). While the formal curriculum referred also to as the written curriculum appears in state frameworks pacing guidelines and packaged materials, the enacted curriculum is what happens in the classroom (Remillard, Citation2005). The interactions between teachers and formal curriculum generate the enacted curriculum through their adaptations such as adding, omitting, modifying, or substituting instructional activities (Troyer, Citation2017).

Curriculum adaptation is also explained as the process in which changes and modifications are made in conjunction with a new curriculum, and there are three key ways (reading, evaluating and adapting) adopted by teachers (Sherin & Drake, Citation2009). Though each of them is crucial and interconnected, Land et al. (Citation2015) posit that there is a slight chance of teachers to evaluate and adapt curriculum effectively without effective reading of curriculum materials. Curriculum materials are educational resources, providing curriculum and instructional design. Meanwhile, teachers’ abilities to use curriculum materials to maximize students’ learning is limited by their resources and the environments in which they work (Burkhauser & Lesaux, Citation2017). The knowledge base argues adaptation in mainly three patterns as omitting, extending, and replacing or revising (Bernard, Citation2017; Bümen & Yazıcılar, Citation2020; Drake & Sherin, Citation2006; Li & Harfitt, Citation2017; Sherin & Drake, Citation2009; Tokgöz Can & Bümen, Citation2021; Troyer, Citation2017). In Appendix 2, definitions and examples of these patterns are provided.

In Türkiye, teachers use the above-mentioned adaptation patterns in high school mathematics courses and the reasons for adaptations are related to the perceived student profiles, centralized education system, curriculum structure, and nationwide high-stakes tests (Bümen & Yazıcılar, Citation2020; Yazıcılar & Bümen, Citation2019). For Sweden, steering documents outline a general framework and teachers are free to choose the resources they want to employ. Teachers’ responsibility is just selecting and using such materials in lessons in a way that enhances students’ learning based on the national core curriculum (Hemmi et al., Citation2018). Examining Swedish teachers’ focus on the new curriculum objectives, Selin and Holmqvist Olander (Citation2015) found that the teachers’ first focus is on the planned activities, secondly on the content, and finally the students’ knowledge. However, this order has changed to the opposite by the use of learning study in their reported intervention. Despite some studies on the relationship between teachers’ interpretations of reform messages (Bergqvist & Bergqvist, Citation2016; Boesen et al., Citation2014) and curriculum materials (Hemmi et al., Citation2018) as well as teachers’ interaction with a research-based curriculum in the Swedish educational context (Van Steenbrugge & Ryve, Citation2018), no studies have explored adaptations based on the sense-making theory.

The sense-making theory

Collective and individual sense-making, as well as objective features, impact actual innovating actions, according to the cultural-individual perspective. Because the actual implementation is always influenced by a complex interplay between the innovation content, the local workplace conditions (contextualization), and the sense-making by the employees, schools rarely respond to educational innovations uniformly (März & Kelchtermans, Citation2013). Sense-making refers to not only how people perceive, choose, and interpret ideas in their environment, but also how they implement them to make them meaningful (Weick, Citation1995). As Rom and Eyal (Citation2019, p. 63) state, ‘it determines what people see and do, how they perceive the real, and why they make different interpretations to the same events, or why they give the same interpretations to different ones’. Individuals and groups make sense of their environments through an (inter) active and dynamic process that guides their behaviours (Coburn, Citation2004). People’s actions are based on how they perceive or select information from the environment, understand it, and then act on it, resulting in the development of culture, social structures, and routines over time (Weick, Citation1995). Similarly, building the type of appropriate reactions and priorities, patterns of social interaction with colleagues, learning environments in school, and local workplace norms all influence teacher sense-making (Coburn, Citation2004). The theory sees teachers as active implementation agents who initially process policy signals in their minds, construct the meaning of the reforms, and then decide to enforce or disregard the changes—based on their interpretation of reform policy—rather than simply reacting to the availability of educational resources and external funding (Chimbi & Jita, Citation2019). Educational researchers use the sense-making theory to explain teachers’ reactions to new policies and/or initiatives implemented into their schools (e.g. Coburn, Citation2001, Citation2004; Coburn & Woulfin, Citation2012; Rom & Eyal, Citation2019). Similarly, Troyer (Citation2017) revealed that teachers respond to the curriculum, with their pre-existing orientations towards teaching and learning, which then serves the formal curriculum adaptation.

The knowledge base explains teachers’ sense-making processes in reaction to policy messages with five possible responses: Rejection, symbolic response, parallel structures, assimilation and accommodation (Coburn, Citation2004; Coburn & Woulfin, Citation2012; Troyer, Citation2017). Rejection is the response in which the teacher does not implement any part of the reform. Symbolic response explains teacher’s changes without any substantive changes in actual instructions, which indicates as if a new policy was being implemented. The teacher implements new practices alongside his/her existing practices in parallel structures; in assimilation, s/he takes aspects of an initiative, but transforms them to fit his/her underlying beliefs; and finally, in accommodation, s/he changes his/her beliefs and practices according to the new policy (Troyer, Citation2017). As it is demonstrated, teachers respond to the curriculum with their pre-existing orientation towards teaching and learning, which then serves for formal curriculum adaptation (Troyer, Citation2017) and therefore we use this theory to capture the actual processes (curriculum adaptations) shaped by the meanings they build. Although teacher sense-making about instructional policy is not solely an individual matter and is also influenced by the social, contextual and political factors (Coburn, Citation2001, Citation2004; März & Kelchtermans, Citation2013), we focused on teachers’ sense-making at the individual-level since the observations of professional development meetings, interviews with principals and team leaders were not conducted in the study, as Coburn did (Coburn, Citation2001; Citation2004). We draw on sense-making theory for guidance in exploring how teachers adapt messages and pressures about curriculum in their professional communities, and how these meanings shape classroom practice.

Turkish educational context

Curriculum reforms putting a major emphasis on the student’s active participation were introduced in 2005 firstly and they were updated in 2017/18 with an emphasis on eliminating curricular overload and enhancing 21st-century skills in Türkiye. However, teachers, who participated in the OECD review report, display some degree of fatigue from the rapid pace of curriculum reforms that are not supported with enough guidance (Kitchen et al., Citation2019). Moreover, a competency-based curriculum requires teachers in all countries to exercise greater autonomy over what happens in their classrooms. Yet, Türkiye has one of the most centralized education systems among the OECD countries (OECD, Citation2017). The development of curricula, the approval of students’ textbooks, the professional development of teachers and the framework for evaluation practices are all centrally determined (Yazıcılar & Bümen, Citation2019).

According to many studies, the autonomy of teachers in Türkiye is quite limited (e.g. Canbolat, Citation2020; Çelik et al., Citation2017). For example, all students’ textbooks are designed by the Ministry of Education (MoNE) and teachers have no right to make any choice in this process (Canbolat, Citation2020). Additionally, the curricula have such a detailed structure that they even include the amount of time to be allocated to each unit (Kitchen et al., Citation2019). Thus, teachers prepare their annual plans by only reiterating the learning outcomes within the curriculum and updating the time of the month and weeks for achieving the learning outcomes. Consequently, this restrictive structure gives teachers a space of autonomy limited only to classroom activities.

Swedish educational context

The Swedish Education Act of 2011 outlines fundamental principles as well as a new overall curriculum for compulsory education, kindergarten, and leisure centres (OECD, Citation2015). The Swedish education system has been thoroughly changed over the last two decades. Accordingly, with decentralization and deregulation distributing responsibilities in different ways, municipalities are now primarily responsible for compulsory and upper secondary schools. Curricula, syllabi, and control and assessment systems exist at the national level, but the amount of detail and degree of precision has changed over time (Forsberg et al., Citation2017).

A new national curriculum for compulsory schools was introduced in 2011 and revised in 2018 by The National Agency for Education (Skolverket, Citation2018). There is no national authority over the curricular materials, which are commercially created (Hemmi et al., Citation2018). The teacher’s guide is brief and refers to one or two pages of explanations, half of which contains a representation of the corresponding textbook page for students. In students’ books, teachers are presented with detailed knowledge about the activities, but with little guidance on how to enact them (Van Steenbrugge et al., Citation2018). Boesen et al. (Citation2014) reveal that Swedish teachers are in general positive attitudes towards the curriculum reform, but most of the teachers’ classroom practices have not changed accordingly and they assimilate the reform message. Seeking the reasons behind this assimilation, Bergqvist and Bergqvist (Citation2016) find that the reform message is presented to a large extent in the policy documents, but that it is vague and developed with complex wording.

It is noticeable that there are many differences in historical, cultural, and pedagogical aspects when the two countries are compared. From a historical perspective, method-oriented and assessment-intensive Curriculum tradition is dominant in Türkiye (Aktan & Serpil, Citation2018), while more teacher-oriented and content-focused Didaktik tradition is dominant in Sweden (Tahirslaj, Citation2021). The PISA 2015 results indicated that school leaders in Sweden reported the highest level of autonomy in their schools (ranked ninth out of 72 countries). In contrast, autonomy was considered to be limited in Türkiye with 71st ranked (OECD, Citation2016). Moreover, schools in Sweden have become increasingly autonomous and are controlled by municipalities as a result of many school reforms; also, these reforms have resulted in the emergence of so-called independent schools (Heinz et al., Citation2017). Teachers have more flexibility in planning their lectures, and the official guidelines do not propose any specific assessment methods (International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA), Citation2012). On the other hand, in Türkiye, public schools lack autonomy in terms of resource distribution, students’ textbook selection, instructional time allocation, personnel deployment, and programme selection. Teachers also claimed that their national curriculum, tight legal constraints, and extensive course content were obstacles to their autonomy (Hammersley-Fletcher et al., Citation2021). Consequently, Türkiye has a centralized system according to the governance arrangements and Sweden has a central with local, in which local authorities (municipalities) might have broad responsibility for delivering education services (Gomendio, Citation2017). In sum, the autonomy of teachers in both countries is framed by many other policy instruments such as central examinations and guidance materials at the local or national level. Nevertheless, Swedish teachers can be considered more autonomous than their Turkish counterparts.

Method

Design and participants

To capture sense-making, we used multiple (comparative) case study design. In multiple case studies, more than one situation per se can be perceived and each situation is handled holistically in itself, and then, compared with each other (Yin, Citation2003). The reason for choosing elementary school mathematics in this study is that the mathematics curriculum in both countries changed in 2018. Additionally, both authors have research experiences related to primary school mathematics teaching.

The criterion sampling was applied to reflect the differences in adaptation patterns in learning-teaching processes, to reveal richer data for the comparison of both countries’ contexts, and to understand the research problem in-depth and multi-dimensionally (Glesne, Citation2011). Accordingly, the year of teaching, the level of school and the curriculum were identified as predetermined characteristics. Because of the researchers’ previous experiences with mathematics curriculum at the primary school level, it was thought that they would be able to understand the contexts better as well as develop validity. Furthermore, Burkhauser and Lesaux (Citation2017) found that experienced teachers appeared better able to adapt curriculum materials to meet instructional goals. Therefore, data were collected from the classroom teachers teaching third-grade mathematics in public primary schools with at least 20-year experience in teaching, to have a broad experience of both current and previous curricula. Attending the study voluntarily, the study group consisted of four teachers from İzmir, Türkiye, and Malmö, Sweden. Turkish teachers are both women (Pseudonyms: Gül and Selen) with 32 and 35 years of experience and their weekly course load is 28 to 30 hours. Similarly, Swedish teachers are both women (Pseudonyms: Ann and Belle) with 27 and 30 years of experience and their weekly course load is 35 hours. The class sizes in Türkiye are 32 and 31, while they are 25 and 26 in the Sweden context. Since sampling logic should not be used in multiple case design, the typical criteria regarding sample size are also irrelevant (Yin, Citation2003). In this sense, the study was conducted with two contradicting cases and the teachers were selected according to the criterion sampling strategy above-mentioned. The number of teachers who participated in the study might be a limitation; however, we tried to overcome this limitation by establishing the chain of evidence (Yin, Citation2003). Besides, in prior studies, analyses were undertaken on two to four teachers (Bümen & Yazıcılar, Citation2020; Drake & Sherin, Citation2006; Li & Harfitt, Citation2017; Troyer, Citation2017; Yazıcılar & Bümen, Citation2019).

Study context

The data for this study came from the second year of implementation of the Turkish and Swedish primary school mathematics curricula, which were both updated in 2017/18. Although they share the similarity concerning reform initiation year, the structures of the curricula and teaching contexts are totally different. In the Turkish third-grade mathematics curriculum with 77-pages, there are learning domains (numbers and operations, geometry, measurement, data processing), units, points to be considered in the teaching process, the time to be allocated to the subjects, detailed objectives for each learning area and suggestions for the measurement approach (MoNE, Citation2018). Textbooks of all subjects in K-12 are distributed to students free of charge by MoNE (Canbolat, Citation2020). Without any teacher’s guidance book, teachers are demanded to create their daily lesson plans; however, in this study, the teachers did not prepare daily plans, only yearly plans are available to study. Long story short, the teachers in Türkiye are required to be loyal to the curricula. To do this, they need to report on what they teach daily by writing learning outcomes specified with some symbols in the curricula into the classroom notebooks. Meanwhile, they are constantly monitored by school administration to check whether they follow the curriculum or not. When an inconsistency is detected, the school administration has the authority to conduct a formal investigation of teachers. Thus, constant monitoring on conducting lessons according to the curricula can be stated for the Turkish context, which was supported by the findings of this study as well. The participant teachers mentioned that they filled in the classroom notebook according to the curricula and their vice principal checked them regularly.

In Sweden, the primary level mathematic syllabus consisting of 10 pages includes the aim of teaching, core contents in the years 1–3, 4–6, 7–9, knowledge requirements from grade E to A at the end of years 6 and 9 (Skolverket, Citation2018). The focus is on the goals to be achieved, which are the same for all students. However, how the teacher designs the instruction is not prescribed in the curriculum, nor what textbooks or learning materials to use. By that, the third-grade mathematics curriculum outlines the general structure of the goals (consisting of only two pages), and teachers can choose the materials they want to use quite autonomously. As Hemmi et al. (Citation2018) said, teachers especially at the primary level, prefer to collect textbooks once or twice a month and detect incorrect solutions. Consequently, Swedish teachers are freer than their Turkish colleagues to conduct their lessons based on their students and school’s needs as the curriculum only outlines the general targets, which was supported by the findings of the study. Swedish teachers explained that they prepared their daily plans based on their students’ needs and had the opportunity to select the course book. Another thing related to the Swedish context is the fact that the teachers work collaboratively. Whenever they need to plan a lesson, they hold meetings and discuss it. However, in the Turkish context, any collaboration between the teachers was not observed. Consequently, when comparing the two contexts, it is clear that the Swedish context provides more autonomy to teachers with an opportunity to select textbooks, and with a curriculum comprised of the targets in general. In Türkiye, the curricula with their content, objectives, learning environments, and even students’ textbooks are all predetermined by the Turkish MoNE, and the teachers have no option other than following the strict curricula.

The cases are two public primary schools and the students are placed in these schools according to their registered addresses in both countries. While the Turkish primary school (K-4) had 43 teachers and 842 students in İzmir, the Swedish school was a K-6 with 550 students and about 80 teachers. Although this case study cannot possibly represent all the schools in Türkiye and Sweden, these two urban schools can still be taken as an indication of how the mathematics curriculum has been adapted in both countries.

Data sources

Multiple measures (triangulation) were used to look for evidence of adaptations and how teachers make adaptations in both Swedish and Turkish contexts. To acquire a better understanding of how the curriculum is adapted in classrooms, we used observations, semi-structured interviews, and document analysis. Data were collected in October-December 2019 in Türkiye, whereas in Sweden, it was collected in March-April 2020.

Observations

Experiences with observations might be facilitating since the first author had previously conducted similar research in Türkiye (Bümen & Yazıcılar, Citation2020; Yazıcılar & Bümen, Citation2019). Before the observations in a non-participant style (Creswell, Citation2014), the aim of observation was first presented to the teachers, and then the teachers conveyed it to their students. Planning and announcing each observation at the convenience of the teacher, the data collection by the observation started, in which Turkish teachers were observed seven (for each) by the first researcher only and Swedish teachers eight times (for each) during the semester. Each observation also lasted a full class period. Meanwhile, the COVID-19 pandemic did not affect the data collection process in Sweden, as Sweden kept schools open during the pandemic. Hence, the lessons were recorded in video by both researchers to be used in the comparisons with the lesson plans for the analysis of adaptations.

Teacher interviews

Following the observations in both countries, interviews were held with the teachers on a predetermined date. The first question was about how the teachers in both countries responded to the changes in the curricula 2018, what was changed and what was kept unchanged. Furthermore, questions about textbooks were only relevant for the Turkish teachers as the Swedish teachers are free to choose textbooks and learning material by themselves. The questions were designed to capture teachers’ experiences of changes in the curricula, and how this affected their instructions. To increase the internal validity, previous studies have been used in the preparation of interview questions (Bümen & Yazıcılar, Citation2020; Coburn, Citation2004; Coburn & Woulfin, Citation2012; Yazıcılar & Bümen, Citation2019; see Appendix 1). By doing this, we aimed to reach the logic linking data (Yin, Citation2003) to establish the relationship between teachers’ sense-making and their curriculum use. The interviews were managed in the teachers’ native language. While the face-to-face interviews with Turkish teachers were managed by the first author in Turkish, in Sweden, they were conducted online by the second author in Swedish due to the pandemic. Each interview lasted between 33 and 60-minutes and they were all recorded and transcribed.

Documents

Comparing them with observation records, the annual and daily lesson plans prepared by the teachers were used to determine adaptations as well. Before the observations, these documents were obtained with the participant teachers’ consent. The yearly plans are prepared based on the mathematics curriculum in Türkiye and all teachers must use it. Swedish teachers, on the other hand, have emailed their own designed plans before their lesson observations because they mostly develop them for daily usage. Their plan is an outline of how the design the instruction to make sure all students in their classroom reaches the goals of the curriculum. The goals are not possible to adjust for the Swedish teachers, but the design of instruction and other learning materials are decided by the teachers.

Data analyses

Data were coded deductively, as the adaptation patterns omitting, extending and replacing were searched for during the analysis of the interviews and lessons. We conducted separate analyses from both countries with the same coding list, and then, compared the coding. Being familiar with the literature due to similar studies on adaptation (Bümen & Yazıcılar, Citation2020; Yazıcılar & Bümen, Citation2019), the first author developed the coding list integrating the definitions and examples of three adaptation patterns in the literature (Drake & Sherin, Citation2006; Li & Harfitt, Citation2017; Troyer, Citation2017; see Appendix 2). For the coding of the observations, all adaptations from each lesson were identified by comparing with the lesson outlined in the teachers’ yearly or daily plan (documents). For instance, as in previous studies, if new objectives other than those specified in the plan were taught in the lesson observations, it was coded as extending. Similarly, if the teachers skipped teaching an objective in the lesson, it was coded as an omitting. By counting the adaptations in each lesson, the adaptations in both countries were determined with the help of these definitions and examples. When there is consistency between the plans and observation records, that is coded as unadapted.

To answer the second research question, we classified the interview data using a typology produced from the previous studies (Coburn, Citation2004; Coburn & Woulfin, Citation2012; see Appendix 3). Hence, we used a theory elaboration strategy like Coburn (Citation2004) by which existing theory is challenged, refined, modified and further specified through an iterative dialog with data from a contrasting case. Gül, for example, changed her teaching in reaction to the mathematics curriculum, but she did so by combining new ideas with old ones rather than changing them entirely. This change corresponds to our description of parallel structures. The Swedish teachers did not need to establish parallel structures as they are supposed to interpret the curriculum with broad and general goals, which can imply curriculum assimilation. Lastly, the interviews were employed before the analyses, so, they included the teachers’ reflections on how they have carried out the lesson plans.

It is critical, in cross-cultural studies, that the research team has both outsiders and insiders (e.g. Hemmi et al., Citation2018), which was the case in our study. Firstly, it is important for validity that the interviews were managed in the teachers’ native language. We also had considerable experience in the research field, as well as practical knowledge of both countries’ educational systems. For internal validity, triangulation was applied by looking for evidence across multiple methods including interviews, observation notes and documents (Yin, Citation2003). Additionally, data analysis is highlighted in the related literature to increase internal reliability (Miles & Huberman, Citation1994). Finally, we did our best to address concerns about external validity by specifying thoroughly the study design, participants, data sources, analysis, and interpretation.

Findings

Turkish and Swedish teachers’ adaptations

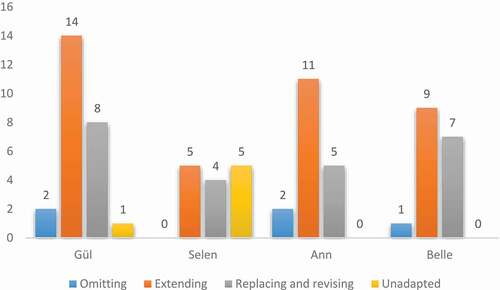

According to the 560-minute lesson observations (14 lessons) in Türkiye and 640-minute observations (16 lessons) in Sweden, the adaptation patterns we have determined are as follows.

Interviews with Turkish teachers also confirm the observation results above. Gül stated that she made mostly extending and replacing in her classes:

I stick (to the curriculum), but expanding it. I am putting pluses in it. Let’s say now … what we did the last time; the charts. Graph reading, graph making and interpretation. After I present everything, I take out all the questions from different sources (materials), the more resources I have the more questions I can prepare for my students. I am definitely making additions (Interview, 29 November 2019).

If a teacher doesn’t make changes (on what is written in the curriculum) there is a malfunction somewhere.:))) Why? As I said, there are deficiencies in all sources in the market, including MoNE. There is no perfect source (material) … (Interview, 28 November 2019)

Similarly, Selen explained that she preferred extending and replacing mostly. However, Selen was more loyal to the programme and timider about adapting

I feel that (implementing) the curriculum is mandatory … so if the programme is given, I must process it. Let me put it in this way … we don’t have much trouble with time. For example, we cover a topic for a week. For example, that week we couldn’t hold the subject. We can move it to the next week. We have no trouble with time. We’re setting it by ourselves. (Interview, 21 November 2019)

Swedish teachers mainly used extending when they taught, and adaptations were identified as replacing content with activities other than Mathematical activities. Movement exercises, used as breaks, to make students move and get new energy was inserted during the lessons. This means that they spent up to five-minute dancing or having some kind of training from a video-based instruction at the Smartboard. Such adaptations were very frequently used and they were not mentioned as an adaptation by the teachers. Based on the teachers’ lesson plans, the teachers did not extend their instruction because they had the opportunity to use their examples and build their teaching on theoretical perspectives unspecified in the curriculum or textbooks. Even if the teacher at this school decides to use textbooks, it is not mandatory:

… so you work differently at different schools, but we have chosen to work with textbooks. (Interview, Belle, 31 March 2020)

By that, adaptations are understood as extending. Belle also explains how she associated what happened in the class with the curriculum by combining several different goals rather than using the curriculum to design lessons:

… the central content was then simple tables, diagrams and it can be used to sort data and describe results for simple surveys. And so, the purpose, I thought it was … bring and follow mathematical reasoning because it was … there was a lot of discussion in the class during the whole lesson. Using mathematical expressions to talk and argue and account for questions, calculations, and conclusions, I felt … argue logically and make mathematical reasoning, it comes again there. (Interview, 31 March 2020)

Teachers’ individual sense-making and adaptations

Turkish and Swedish teachers did not respond to the national mathematics curriculum in the same way. Drawing on a typology (Coburn, Citation2004; Coburn & Woulfin, Citation2012), we identified only two of the five responses that Turkish teachers had to the national curriculum: parallel structures and assimilation. For Sweden, only assimilation was found. There was no evidence of rejection, symbolic response, or accommodation responses in both countries’ classrooms concerning the third-grade maths curriculum. In the next section, we describe each response across teachers.

Turkish teachers’ findings

Parallel structures. Encountering messages that conflicted with her pre-existing practices, Gül responded to the curriculum by creating parallel structures. Since she found the curriculum content in the third grade inadequate, she said that she taught the subjects of the upper classes and used problems from the 4th-grade books. Gül’s enactment of the curriculum represents parallel structures as she ‘adds the new approach to her instructional programme without changing the existing programme’ (Coburn & Woulfin, Citation2012, p. 14).

When I first started teaching, we used to solve such difficult questions … The subjects were too much, the students got more and more. Now there is no subject, the information has decreased, the subject has decreased, the depth has also decreased. So now I am looking, we used to present all seventh-grade subjects in primary school. Now it feels very poor (to me). It is against my soul … I say it seriously. Children are bored, too. For a week, the same topic … (it) cannot be the same topic … (we) should do something different … (Interview, 28 November 2019)

Confirming the findings of the interviews, observation records also showed activities such as providing more challenging problems that require more than one operation in addition to the objectives in the curriculum.

She wrote a subtraction question with a symbol on the blackboard as follows, ■ ■ ■ - ♥ ♥ ♥ = 111. According to this operation, which of the following cannot be said? A) ■ - ♥ = 1, b) if ■ is an even number, then ♥ is an odd number c) if ■ is an odd number, then ♥ is an odd number. She wrote the rule (if an odd number is subtracted from an even number, it remains an odd number) on the board. She then wrote another rule (if an even number is subtracted from an even number, the even number remains) on the board and solved the problems about it. (Observation record, 7 November 2019)

In the lesson quoted above, the target of the day was ‘estimating and comparing the result of subtraction with natural numbers’ according to the annual plan, but the problems of making different subtractions with odd and even numbers were resolved though. Gül explained this addition by referring to the curriculum and students’ textbooks as poor and the problems included were simple. With 32 years of experience, Gül seemed to have created a parallel curriculum for herself using too many extra materials as she considered the content of the mathematics programme and textbook inadequate.

Assimilation. Assimilating the new message into her existing scheme or ways of her teaching, Selen proclaimed, ‘I think that educational unity is needed’. Indeed, she was the most faithful to the formal curriculum -the number of lessons she did not adapt during the observations was five in seven (see, ). She appeared to understand the mathematics curriculum as a programme to apply with faithfulness, despite her 35 years of teaching experience. Her instructional focus was on following the curriculum’s objectives in the correct order. She explained, ‘Yes … I am not going out of the desired (in the programme) right … I am not very critical’. According to Selen, there is not much change in the elementary school mathematics curriculum and it is appropriate to reduce the topics in the curriculum. Thus, she treats the curriculum change positively.

No … topics have been reduced, but I think it’s appropriate. It is normal, because in a classroom with 35 persons, for example, the success rate in mathematics is not one hundred percent. So, students can grapple even this curriculum. I mean this is even barely practiced. (Interview, 15 December 2019)

However, Selen’s observations reflected her old practices and her understandings rather than the activities proposed by the new curriculum. While the new curriculum includes the objectives related to creating a multiplication table or rhythmic counting instead of memorization, Selen stated that it should be memorized as it is done before the following:

For example, I believe in memorizing the multiplication table. Some things demand memorization. Otherwise, they cannot quickly solve problems. Memorizing makes their job easier. The curriculum says, for example, ‘teach multiplication by rhythmic counting’. Yes, we also count rhythmic. But you give children a certain amount of time on the exam. The child is jumping somewhere while counting in rhythmic counting. Suddenly, they get confused. But if s/he memorizes 7 times 9, 63, s/he answers instantly. (Interview, 21 November 2019)

Moreover, she highlighted the national exam at the end of the eighth grade in Türkiye as a reflection of the advantages of her old practices, which are illustrated in the following:

I am passionate about old books.:)) I have my archive. Old books are books that I still cannot leave. The previous programme (curriculum) was of course heavier; the current one is very shallow. The programme is very nice, we will do it without boring the kids, but you are faced with a reality like LGS (national high stakes test in secondary school). Then, the parents will ask me, ‘What are we doing in the national exam?’. So I am already solving problems for many years. (Interview, 15 December 2019)

Confirming the interview findings above, her observation records revealed her usage of three or four-process problems in her teaching as stated in the previous year’s curriculum ‘working with two-process problems while solving problems that require addition’ (MoNE, Citation2018). Similar observation records are quoted as follows:

She began asking questions about the sets from a book she had taken out of her closet. She said that she would distribute copies because the children did not have that book or material. The material describes the definition and properties of the sets and asks if the samples are sets. (Observation record, 14 November 2019)

In the interviews, she stated that she had taught the subject of sets for many years and that the students had problems in secondary school due to the exclusion of this subject from the programme. Thus, Selen responded to the curriculum with assimilation, transforming most curriculum activities to fit with her pre-existing practices (Coburn, Citation2004, p. 224).

Swedish teachers’ findings

Assimilation. Overall, the Swedish teachers interpret the curriculum and enact the goals in a way that they decide themselves. By that, assimilation is the prominent response to the curriculum. Each lesson started with the presentation and description of the curriculum goal by the teachers. For instance, a goal was to interpret and understand diagrams/charts. It was written on the blackboard and teachers explained what the children are supposed to learn during the lesson. Meanwhile, she presented a task to solve at the beginning of the lesson as well as at the end of the lesson, which makes it possible for the teacher to follow the children’s knowledge development. During the interviews, the teachers were asked to reflect upon the coming changes in the curriculum, regarding their interpretations of the changing goals:

… we have worked with this earlier in grade two, so I knew what prior knowledge they had. But, as it said in the lesson planning, we had an entrance ticket first because I wanted to check it out anyway to see. Because it was still maybe a year since they worked with it. So I had an entrance ticket and then I quickly determined what they had remembered and what I needed to focus on. So that … that’s how I did. (Interview, 31 March 2020, Ann)

There were no changes in any lesson regarding the initially presented goals, which were exactly written or verbally presented as in the curriculum. The teachers were allowed to read the planned changes in the new curriculum in mathematics and they found that it correlates very well with how they teach

Ann: Yes, there’s no problem. I feel that it could have been done the same with the new curriculum. It says about … let’s see here, we had underlined under … ‘use and describe mathematical concepts’. Yes, that was about what I was doing in the last lesson. ‘Mathematical methods for making calculations’ …

Belle: We did that when solving problems.

Ann: Yes, that was the problem-solving task we had. ‘Amount of length and older units of measurement’ … it also remains as before. We also had a lesson about that. ‘Simple tables and charts, how it can be used to sort data and describe results from surveys. Both with and without digital tools’. No, I feel I could have done … I could have done these lessons with the new curriculum, (Interview, 16 April 2020, Ann and Belle)

As the curriculum comprised only what the students are expected to achieve in different grades without any detailed instructions about the content, the teachers do not need rejection, symbolic response, or parallel structures. To capture such acts, need for a normative template of how teachers’ instruction is expected to be carried out, which does not exist in Sweden. Without such a template, the analysis becomes hesitant and speculative. The teachers conduct the goals in the curriculum based on their understanding of how instruction should be designed to promote what learning the students are supposed to develop. Since everything is up to the teacher’s decision, there is no possibility of following a plan for instruction or textbook and detecting when s/he deviates from the plan.

However, the interview data revealed just an example showing how the teachers reacted to a new goal, programming in the mathematics curriculum initially. The excerpts below illustrate how these reactions led to both rejection and accommodation, however, it was not found in the data from the teachers’ classroom observations. Even if the rejection was not found in the data material from the participant teachers, the teachers mentioned their dialog with some of their colleagues who had some questions about new goals in Mathematics, programming, which is a retrospective of reflections on how the teachers in the project experienced their colleagues’ reactions about the new goal in the mathematics curriculum:

It was probably a bit-mixed reactions … the reactions that you said that some who thought ‘wow, this is great and this is the future but also those who thought that ‘I do not need to do this’ so … but it is … We have also taken courses, so now I think that more and more people are positive about it as well. (Interview, Ann, 26 March 2020)

Similarly, accommodation was found only in the interview data. As the Swedish curriculum gives the flexibility for teachers’ interpretations and enactment instead of describing in detail what and how they should teach, teachers rarely have to adjust their instructions based on the government’s decisions. Forcing teachers to teach programming in Mathematics (the example above) might intrude on teachers’ self-determination. Although the participant teachers described how other colleagues were doubtful of the change, they changed their way of teaching and developed new content knowledge to meet the new requirements:

But the three of us, we talk with each other almost all the time about how we work and so on. And we do a lot together with our classes. So, for example, when we had programming, we divided them into each third and then we mixed the classes and then we do not have to do the same thing for all of us. But then you do everything three times [once for each group of pupils] and then you do something new so that … and we were acquainted with this and I feel that this will be the same thing … if this comes, we will get acquainted with this and then discuss in groups, and so on ‘how should we now coach the students and how will this affect our assessment’ and so on. So that we get to know it, it will be like that. Just like we did when the programming came. (Interview, Belle, 26 March 2020)

Discussion

The findings of the first research question surprisingly indicate that both Turkish and Swedish classroom teachers frequently use the same adaptation patterns; respectively extending, replacing/revising, and omitting. Nevertheless, it is expected that teacher adaptations will differ owing to their educational contexts (i.e. centralized or decentralized). This finding can be explained through the inevitability of teachers’ adaptations (Roth Mcduffie et al., Citation2018) and the experienced teachers’ ability to adapt materials better (Burkhauser & Lesaux, Citation2017). Despite the similarity in adaptation patterns, the study revealed that Turkish teachers are more faithful to the textbook by making only minor changes from time to time, unlike their Swedish counterparts. Since Swedish teachers are not obligated to use textbooks and there is no instruction about content or teaching in the curriculum (Hemmi et al., Citation2018), no results regarding fidelity could be obtained. Additionally, Turkish teachers provided sufficient information about their adaptations and they even tried to explain their rationale. Having given a detailed curriculum on what to do in the classroom and a textbook that they have to use (Canbolat, Citation2020; Kitchen et al., Citation2019), Turkish teachers might feel the need to explain they do not do anything wrong. In contrast, Swedish teachers perceive the changes they made in classes as teaching, not as adaptations.

These findings confirm that national policies have a significant impact on classroom teaching, which is illustrated by other comparative case studies on mathematics curriculum (Lui & Leung, Citation2013; Pepin et al., Citation2013) since educational and cultural traditions from the policy-level influence classroom practices through textbooks. Traditions at the heart of teacher education in Sweden and Türkiye (Didaktik vs. Curriculum) affect the understanding of teaching as well. While the Didaktik tradition, which is dominant in continental and northern Europe, is more teacher-oriented and content-focused, the Curriculum tradition, which is dominant in English-speaking countries and North America, is method-oriented and assessment-intensive (Tahirslaj, Citation2021). The dominance of the Curriculum tradition in Türkiye (Aktan & Serpil, Citation2018) and the Didaktik tradition in Sweden (Tahirslaj, Citation2021) seem to have influenced the perceptions of the curriculum adaptation quite differently.

When comparing the two countries, Türkiye ranks 71st whereas Sweden is ninth in the level of perceived autonomy according to the school principals’ reports in PISA 2015 (OECD, Citation2016). Although Turkish students’ scores in PISA 2018 increased compared to 2015, Türkiye remained below the OECD average in all areas of reading, mathematics, and science. In contrast, in the same year’s results, Swedish 15-year-old students performed above the OECD average on all of the reading, mathematics, and science tests (OECD, Citation2019). As the PISA findings show, increased school autonomy tends to allow teachers to adjust their instruction to the needs of their students rather than following a prescriptive curriculum (Gomendio, Citation2017), it is necessary to increase the autonomy of teachers in Türkiye and support them for adaptations (Canbolat, Citation2020; Tokgöz Can & Bümen, Citation2021). Turkish teachers, like their Swedish counterparts, should be free to choose teaching content and make curricular decisions.

The findings revealed that Turkish teachers responded with parallel structures and assimilation to the curriculum and Swedish teachers responded only with assimilation. There is no similar study in Türkiye, nevertheless, the findings on Swedish teachers’ assimilation concurred with the previous studies conducted in Sweden (Bergqvist & Bergqvist, Citation2016; Boesen et al., Citation2014). Despite the similarity between Selen (Turkish participant) and Swedish senior teachers regarding assimilation, the mediation of this orientation to adaptations seems to be different. Why did Selen’s assimilation mediate fewer adaptations (see, ) while Swedish teachers’ assimilation mediated more adaptations (extension and replacing/revising)? The fact that Turkish teachers find their autonomy insufficient might be an answer to this question as they are hesitant to make adaptations. Indeed, Turkish teachers with low perceptions of autonomy -just like Selen- do not omit at all and make replacing/revising as they find it less risky (Tokgöz Can & Bümen, Citation2021). Unlike Türkiye, Swedish teachers perceived their autonomy was high in the educational domain at the classroom level due to the rapid decentralization in the 1990s (Paulsrud & Wermke, Citation2020). Another important thing is the local collectivism as a characteristic shared by many Swedish teachers (Helgøy & Homme, Citation2007) since the adaptations of the two Swedish teachers are very similar as seen in the findings (see, ). According to Coburn and Woulfin (Citation2012), the structural and social factors of the workplace, as well as patterns of social interaction with others in the school, influence teacher sense-making concerning instructional policy. This interaction determines which components of policy teachers perceive, how they pay attention to some policy messages while ignoring others, and how they comprehend the policy and its implications for their classroom instruction, all of which affect their implementation. Thus, collectivism among Swedish teachers may have caused the assimilation of the curriculum to mediate more adaptations. In contrast, the weak collaboration among teachers in Türkiye (Gümüş et al., Citation2013; Özdoğru, Citation2021) may have led to a different understanding of policy messages and individual adaptation of the curriculum with this sense-making.

Besides, it was detected that since Gül did not approve of the textbook, she adapted much more than Selen and created a parallel curriculum for herself, whose reason is that the subjects are very easy and few compared to the ones in the previous curriculum. She was making adaptations by providing the subjects and skills in the next year’s curriculum because she fears that the students’ mathematical skills will remain poor. Coburn (Citation2001, Citation2004) argued that teachers’ perceptions of the degree of congruence between institutional pressures (curriculum) and pre-existing beliefs and practices are particularly crucial in sense-making. Previous studies (Bernard, Citation2017; McCarthey & Woodard, Citation2017; Remillard & Bryans, Citation2004) also revealed that teachers adapt curriculum when they find it problematic. Therefore, like some teachers in Troyer’s (Citation2017) study, the sense-making process of Gül’s disappointment in the mathematics curriculum and textbook (parallel structures) has led her to extend and replace/revise more. Gül’s experiences undoubtedly played a role in making better adaptations. Yet, interestingly, she made more adaptations and created parallel structures without hesitation and even by being aware of the formal investigation if she did not adhere to the curriculum. Perhaps this can be explained by the principled resistance of teachers when they perceive the proposed curriculum changes as detrimental to their students and society in general, as Koşar Altınyelken (Citation2013) elicited.

Conclusion

The findings expand on previous national-based adaptation studies (e.g. Bümen & Yazıcılar, Citation2020; Burkhauser & Lesaux, Citation2017; Li & Harfitt, Citation2017) and allow the comparison of adaptation patterns in two countries with quite different contexts. As the only study, to our knowledge, addressing teacher adaptations in comparison with centralized and decentralized countries, it has elucidated curriculum adaptations rather than curriculum-teacher interactions. Using sense-making theory lenses in cross-cultural settings, it was discovered that teachers’ adaptations are the result of their curricular sentiments. Turkish findings demonstrated that teachers make adaptations based on their curriculum orientations no matter how centralized the educational context is. Therefore, it comes to mind that Turkish students in different classes get very different experiences within the same curriculum and school. In contrast, Swedish teachers perceive the changes they make in the classroom as their teaching style, not as ‘adaptation’ since there are no detailed instructions on content or teaching in the curriculum. Thus, the study confirms and expands on Troyer’s (Citation2017, p. 22) assertion that ‘curriculum is not as a static document, nor as a linear process of transmission or resistance, but as an interactive process of sense-making’. As a consequence, teachers adapt the formal curriculum by employing their pre-existing orientations towards teaching and learning as a lens on it.

We conclude by acknowledging some methodological limitations as it included only two teachers from both countries. We were unable to find more volunteer teachers during the days full of uncertainties and risks since the Swedish data were collected during the COVID-19 pandemic’s first year (March-April 2020). Future research should collect comprehensive data from a broader sample of teachers with varied expertise across disciplines to expand on the findings of this study.

Implications and further research

Classroom teachers are responsible for all or various school subjects in several countries. Accordingly, they have difficulty designing lessons with high quality as they have to make all decisions by themselves and also they do not have expert knowledge in all areas. Our senior teachers from both countries in this study struggle with similar challenges, however; Turkish teachers are not free enough to implement changes needed for their students’ knowledge development. When better-grasping teachers’ sense-making, future research and practice should provide the opportunity to motivate accommodation as the most critical pedagogical elements of a curriculum. With curricular change especially including complex messages, teachers need time and support to complete the systematic process necessary for accommodation. Therefore, curriculum and professional development designers should pay more attention to the teachers’ sense-making. Further research on the relationships between teachers’ adaptations and student learning is also required. Instead of focusing on the sense-making process from the viewpoint of the individual as in this study, collective sense-making comparisons can enhance better understanding in culturally diverse contexts.

Appendices.docx

Download MS Word (17.5 KB)Acknowledgments

This publication is part of the first author’s research work at Malmö University, thanks to a Swedish Institute scholarship, registration number 25829/2018. We are also grateful to the Turkish and Swedish teachers for allowing us to observe their lessons and taking their time with us.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2022.2121178

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Nilay T. Bümen

Nilay T. Bümen, PhD., is currently a professor of Curriculum and Instruction at Ege University Faculty of Education, Izmir, Türkiye. Her research interest includes curriculum studies, effective teaching and teacher education.

Mona Holmqvist

Mona Holmqvist, PhD., is currently a professor of Educational Sciences at Malmö University, Faculty of Education and Society, Malmö, Sweden. Her research interest includes conditions of learning, in different contexts such as the age and cognitive conditions of the learners, content focus and levels of education.

References

- Ahl, L., Gunnarsdóttir, G. H., Koljonen, T., & Pálsdóttir, G. (2015). How teachers interact and use teacher guides in mathematics – Cases from Sweden and Iceland. Nordic Studies in Mathematics Education, 20(3–4), 179–197. http://ncm.gu.se/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/20_34_179198_ahl.pdf

- Aktan, S., & Serpil, H. (2018). Didactic in continental European pedagogy: An analysis of its origins and problems. International Journal of Curriculum and Instructional Studies, 8(1), 111–134. https://doi.org/10.31704/ijocis.2018.006

- Bergqvist, E., & Bergqvist, T. (2016). The role of the formal written curriculum in standards-based reform. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 49 (2), 149–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2016.1202323

- Bernard, A. M. (2017). Curriculum decisions and reasoning of middle school teachers. [ Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Brigham Young University. http://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/6488

- Boesen, J., Helenius, O., Bergqvist, E., Bergqvist, T., Lithner, J., Palm, T., & Palmberg, B. (2014). Developing mathematical competence: From the intended to the enacted curriculum. The Journal of Mathematical Behavior, 33, 72–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmathb.2013.10.001

- Brown, M. W. (2009). The teacher-tool relationship: Theorizing the design and use of curriculum materials. In J. T. Remillard, B. A. Herbel-Eisenmann, & G. M. Lloyd (Eds.), Mathematics teachers at work: Connecting curriculum materials and classroom instruction (pp. 17–36). Routledge.

- Bümen, N. T., & Yazıcılar, Ü. (2020). A case study on the teachers’ curriculum adaptations: Differences in state and private high school. Journal of Gazi Education Faculty, 40(1), 183–224. https://doi.org/10.17152/gefad.595058

- Burkhauser, M. A., & Lesaux, N. K. (2017). Exercising a bounded autonomy: Novice and experienced teachers’ adaptations to curriculum materials in an age of accountability. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 49(3), 291–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2015.1088065

- Canbolat, Y. (2020). Professional autonomy of high school teachers in Turkey: A retrospective and prospective policy analysis. Education and Science, 45(202), 141–171. http://egitimvebilim.ted.org.tr/index.php/EB/article/view/7833/3038

- Çelik, Z., Gümüş, S., & Gür, B. S. (2017). Moving beyond a monotype education in Turkey: Major reforms in the last decade and challenges ahead. In Y. K. Cha, J. Gundara, S. H. Ham, & M. Lee (Eds.), Multicultural education in glocal perspectives (pp. 103–119). Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

- Chimbi, G. T., & Jita, L. C. (2019). Willing but unable? Teachers’ sense-making of curriculum-reform policy in the early implementation stage. Pedagogika, 3(3), 52–70. https://doi.org/10.15823/p.2019.135.3

- Coburn, C. E. (2001). Collective sense-making about reading: How teachers mediate reading policy in their professional communities. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 23(2), 145–170. https://doi.org/10.3102/01623737023002145

- Coburn, C. E. (2004). Beyond decoupling: Rethinking the relationship between the institutional environment and the classroom. Sociology of Education, 77(3), 211–244. https://doi.org/10.1177/003804070407700302

- Coburn, C. E., & Woulfin, S. L. (2012). Reading coaches and the relationship between policy and practice. Reading Research Quarterly, 47(1), 5–30. https://doi.org/10.1002/RRQ.008

- Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design, qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approach. SAGE Publications.

- Drake, C., & Sherin, M. G. (2006). Practicing change: Curriculum adaptation and teacher narrative in the context of mathematics reform education. Curriculum Inquiry, 36(2), 153–187. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-873X.2006.00351.x

- Fogo, B., Reisman, A., & Breakstone, J. (2019). Teacher adaptation of document-based history curricula: Results of the reading like a historian curriculum-use survey. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 51(1), 62–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2018.1550586

- Forsberg, E., Nihlfors, E., Pettersson, D., & Skott, P. (2017). Curriculum code, arena, and context: Curriculum and leadership research in Sweden. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 16(2), 357–382. https://doi.org/10.1080/15700763.2017.1298811

- Glesne, C. (2011). Becoming qualitative researchers: An introduction. Canada, Longman.

- Gomendio, M. (2017). Empowering and enabling teachers to improve equity and outcomes for all, international summit on the teaching profession. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264273238-en

- Gümüş, S., Bulut, O., & Bellibaş, M. S. (2013). The relationship between principal leadership and teacher collaboration in Turkish primary schools: A multilevel analysis. Education Research and Perspectives, 40, 1–29. https://www.erpjournal.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Teach-Collab-inTurkey-Gumus.pdf

- Hammersley-Fletcher, L., Kılıçoğlu, D., & Kılıçoğlu, G. (2021). Does autonomy exist? Comparing the autonomy of teachers and senior leaders in England and Turkey. Oxford Review of Education, 47(2), 189–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2020.1824900

- Heinz, J., Enghag, M., Stuchlikova, I., Cakmakci, G., Peleg, R., & Baram-Tsabari, A. (2017). Impact of initiatives to implement science inquiry: A comparative study of the Turkish, Israeli, Swedish and Czech science education systems. Cultural Studies of Science Education, 12(3), 677–708. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11422-015-9704-6

- Helgøy, I., & Homme, A. (2007). Towards new professionalism in school? A comparative study of teacher autonomy in Norway and Sweden. European Educational Research Journal, 6(3), 4. https://doi.org/10.2304/eerj.2007.6.3.232

- Hemmi, K., Krzywacki, H., & Liljekvist, Y. (2018). Challenging traditional classroom practices: Swedish teachers’ interplay with Finnish curriculum materials. Journal of Curriculum Studies. 51 (3), 342–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2018.1479449

- International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA). (2012). TIMSS 2011 encyclopedia: Education policy and curriculum in mathematics and science: (Volumes 1 and 2). http://timssandpirls.bc.edu/timss2011/downloads/TIMSS2011_Enc-v1.pdf

- Kitchen, H., Bethell, G., Fordham, E., Henderson, K., Li, R. R., et al. (2019). OECD Reviews of evaluation and assessment in education: Student assessment in Turkey. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/5edc0abe-en

- Koşar Altınyelken, H. (2013). Teachers’ principled resistance to curriculum change: A compelling case from Turkey. In A. Verger, H. K. Altınyelken, & M. Koning (Eds.), Global managerial education reforms and teachers: Emerging policies, controversies and issues in developing contexts (pp. 109–126). Education International Research Institute.

- Land, T. J., Tyminski, A. M., & Drake, C. (2015). Examining elementary mathematics teachers’ reading of educative curriculum materials. Teaching and Teacher Education, 51, 16–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2015.05.009

- Li, Y. (2019). Teacher sense-making of English curriculum reform in China: A sociocultural perspective on teacher change and development. [ Doctoral dissertation]. The University of New.

- Li, Z., & Harfitt, G. J. (2017). An examination of language teachers’ enactment of curriculum materials in the context of a centralized curriculum. Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 25(3), 403–416. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2016.1270987

- Lui, K. W., & Leung, F. K. S. (2013). Curriculum traditions in Berlin and Hong Kong: A comparative case study of the implemented mathematics curriculum. ZDM Mathematics Education, 45(1), 35–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-012-0387-0

- März, V., & Kelchtermans, G. (2013). Sense-making and structure in teachers’ reception of educational reform. Teaching and Teacher Education, 29, 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2012.08.004

- McCarthey, S. J., & Woodard, R. (2017). Faithfully following, adapting, or rejecting mandated curriculum. Pedagogies: An International Journal, 13 (1), 56–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/1554480X.2017.1376672

- Miles, M. B., & Huberman, M. A. (1994). Qualitative data analysis. SAGE Publications.

- MoNE. (2018). Matematik dersi öğretim programı, ilkokul ve ortaokul 1–8. sınıflar. [The mathematics curriculum of grade 1–8]. Talim Terbiye Kurulu Başkanlığı.

- OECD. (2015). Improving schools in Sweden: An OECD perspective. http://www.oecd.org/education/school/improving-schools-in-sweden-an-oecd-perspective.htm

- OECD. 2016. PISA 2015 results (Volume II): Policies and practices for successful schools. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264267510-en

- OECD. (2017). Education at a Glance 2017: OECD indicators.

- OECD. (2019). PISA 2018 results (Volume I): What students know and can do. https://doi.org/10.1787/5f07c754-en

- Özdoğru, M. (2021). Cooperation between teachers: Current situation, barriers and solutions. Journal of Education and Humanities, 12(23), 125–147. https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/download/article-file/1488436

- Paulsrud, D., & Wermke, W. (2020). Decision-making in context: Swedish and finnish teachers’ perceptions of autonomy. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 64(5), 706–727. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2019.1596975

- Pepin, B., Gueudet, G., & Trouche, L. (2013). Investigating textbooks as crucial interfaces between culture, policy, and teacher curricular practice: Two contrasted case studies in France and Norway. ZDM Mathematics Education, 45(5), 685–698. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-013-0526-2

- Remillard, J. T. (2005). Examining key concepts in research on teachers’ use of mathematics curricula. Review of Educational Research, 75(2), 211–246. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543075002211

- Remillard, J. T. (2019). Teachers’ use of mathematics resources: A look across cultural boundaries. In L. Trouche, G. Gueudet, & B. Pepin (Eds.), The ‘resource’ approach to mathematics education (pp. 173–194). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-20393-1

- Remillard, J. T., & Bryans, M. B. (2004). Teachers’ orientations toward mathematics curriculum materials: Implications for teacher learning. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 35(5), 352–388. https://doi.org/10.2307/30034820

- Remillard, J. T., Van Steenbrugge, H., & Bergqvist, T. (2016). A cross-cultural analysis of the voice of six teacher’s guides from three cultural contexts. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Washington, D.C.

- Rom, N., & Eyal, O. (2019). Sense-making, sense-breaking, sense-giving, and sense-taking: How educators construct meaning in complex policy environments. Teaching and Teacher Education, 78, 62–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2018.11.008

- Roth Mcduffie, A., Choppin, J., Drake, C., & Davis, J. (2018). Middle school mathematics teachers’ noticing of components in mathematics curriculum materials. International Journal of Educational Research, 92, 173–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2018.09.019

- Selin, P., & Holmqvist Olander, M. (2015). Transforming new curriculum objectives into classroom instruction with the aid of learning studies. International Journal for Lesson and Learning Studies, 4(4), 401–415. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLLS-01-2015-0006

- Sherin, M. G., & Drake, C. (2009). Investigating patterns in teachers’ use of a reform-based elementary mathematics curriculum. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 41(4), 467–500. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220270802696115

- Skolverket. (2018). Curriculum for the compulsory school, preschool class and school-age educare. https://www.skolverket.se/download/18.31c292d516e7445866a218f/1576654682907/pdf3984.pdf

- Tahirslaj, A. (2021). Teacher responsibility over intended, taught, and tested curriculum, and its association with students’ science performance in PISA 2015 across Didaktik and curriculum countries. In E. Krogh Qvortrup & S. T. Graf (Eds.), Didaktik and curriculum in ongoing dialogue (London: Routledge) (pp. 222–233). https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003099390

- Tokgöz Can, M., & Bümen, N. T. (2021). Turkish teachers’ autonomy in using and adapting curriculum: A mixed methods study. Issues in Educational Research, 31(4), 1270–1292. https://www.iier.org.au/iier31/tokgoz-can.pdf

- Troyer, M. (2017). Teachers’ adaptations to and orientations towards an adolescent literacy curriculum. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 51(2), 202–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2017.1407458

- Van Steenbrugge, H., Remillard, J., Krzywacki, H., Hemmi, K., Koljonen, T., & Machalow, R. (2018). Understanding teachers’ use of instructional resources from a cross-cultural perspective: The cases of Sweden and Flanders. In V. Gitirana, (Ed.), Proceedings of There(s) sources 2018 international conference (pp. 117–121). ENS de Lyon.

- Van Steenbrugge, H., & Ryve, A. (2018). Developing a reform mathematics curriculum program in Sweden: Relating international research and the local context. ZDM Mathematics Education, 50(5), 801–812. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-018-0972-y

- Weick, K. (1995). Sense-making in organizations. Sage.

- Westwood Taylor, M. (2016). From effective curricula toward effective curriculum use. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 47(5), 440–453. https://doi.org/10.5951/jresematheduc.47.5.0440

- Yazıcılar, Ü., & Bümen, N. T. (2019). Crossing over the brick wall: Adapting the curriculum as a way out. Issues in Educational Research, 29(2), 583–609. http://www.iier.org.au/iier29/yazicilar.pdf

- Yin, R. K. (2003). Case study research: Design and methods. Sage.

Appendix 1

Interview questions

1.How many years have you been teaching?

2.Which school types or cities have you worked in before? Did you experience the differences between the types of school or city when implementing the mathematics curriculum? What differences did you experience?

3. What did you think when the maths curriculum (in elementary school) changed? What have you done? What have you been through?

4. How do you react when a curriculum changes in general? How do you behave? Are your thoughts and behaviours the same for such curriculum changes? Is it different? How do you behave? Can you give an example of what lies in your mind or not?

5. How would you describe your teaching practices compared to your past 10 years? Do you think there is any change?

6. Can you give some examples of what looks like or doesn’t resemble your old practices when programmes change? For example, how do you examine whether the things proposed in the book or programme are similar to your previous practices?

7. Will your pedagogical approach to teaching mathematics change when the curriculum changes? If he comes by, why? If it is not observed, why?

8. What do you and your colleagues in the department talk about the curriculum and textbooks? What do you share? What do you discuss?

9. What do you talk about with the school management (principal or vice-principal) about the curriculum? What do you share? What do you discuss?

10. What do you talk to parents about using textbooks or additional resources? What do you share?

11.How do you prepare your yearly plan, or if you are using a ready-made plan where do you get it from?

12.Do you make any changes while following the yearly/unit plan?

Alternative questions:

a. Although some subjects take part in the curriculum, some teachers think that some subjects are not suitable for the class/type of school and they omit them. Do you have such or different implementations? When and how do you plan these changes?

b. It is said that the sequence of learning domains, sub-learning domains and objectives in the curriculum should be considered as the order of processing. Are you doing a different sort of content? Why is that?

c. Do you make any changes in the recommended time for an objective or a subject? How?

13.Do you keep your changes? How? (Do you save and then reflect on your plans or your own materials?)

14. What do you consider when changing the curriculum by class? How do you determine the changes? Can you give some examples? How do you take them into account?

a. Students (let’s open here)

b. School management

c. Teachers in the department

d. Parents

e. Exams and so on.