ABSTRACT

Numerous reviews have synthesized the empirical research on the effectiveness of teacher education, highlighting teacher education effectiveness research (TEER) as an emerging research paradigm. Our systematic search identified 27 reviews related to TEER, wherein teacher education is broadly understood as comprising all stages of teacher professionalization—namely, initial teacher education, teacher induction, and teacher professional development. In reviewing these reviews, we carry out a synthesis of existing research on TEER. Guided by four research questions (RQ), we focused major frameworks (RQ1), outcome measures (RQ2), processes (RQ3), and central research gaps (RQ4). Highlights: Only few reviews provide a background or macro framing, whereas most reviews apply TEER for examining a specific topic (RQ1); outcome measures often relate to the notion of teacher competence, making increased competence the true outcome of TEER (RQ2); coursework is the most dominant category of characteristics-forming processes (RQ3); the frameworks underlying the outcome measures appear to be an object of criticism on a theoretical but even more on a methodological level. Building on these findings, we suggest a processes-and-criteria classification (PCC) grounded in basic distinctions of the various studies synthesized by the reviews. We discuss perspectives on how this classification may provide an orientation for future TEER studies.

Introduction

Teachers play a significant role in providing their students with adequate learning opportunities and thereby affecting student learning progress. This is supported by scientific evidence reported by meta-analyses of empirical studies relating to teacher effectiveness (e.g. Hattie, Citation2012; Seidel & Shavelson, Citation2007) and, more recently, by an increasing number of empirical studies expanding the analysis of teacher effectiveness using direct measures of teacher competence (e.g. Baumert et al., Citation2010; Blömeke et al., Citation2022). Scholars broadly agree that both initial teacher education (ITE) and teacher professional development (TPD) may serve to improve teachers’ competence and effectiveness for classroom teaching (e.g. Hill et al., Citation2021; Kaiser & König, Citation2019). Further benefits of ITE and TPD relate to teacher well-being (e.g. Hascher & Waber, Citation2021) and the implementation of innovations in education, such as digitalization at school (e.g. Fernández-Batanero et al., Citation2022) or fostering inclusive education (e.g. Florian & Camedda, Citation2020). However, doubts regarding such benefits have regularly been expressed. For example, almost two decades ago, Sultana (Citation2005, p. 236) stated, ‘Perhaps the most disheartening news for teacher educators is the overwhelming evidence of their ineffectiveness’. More recently, König and Blömeke (Citation2020) concluded that research on teacher education effectiveness has not yet succeeded in clearly defining and conceptualizing an evidence-based theoretical framework of effective teacher education. Whether teacher education still has ‘low impact’ as Lortie (Citation1975, p. 81) stated as early as half a century ago is a question that is still worth addressing today. For example, Hattie (Citation2012) found only a small effect size (d = .11) for ITE in his meta-meta-studies on effective teaching. In addition to formal learning opportunities, the evidence clearly indicates that non-formal learning and experience gained from teaching practice, during both ITE and in-service teaching, contribute to teachers’ successful performance in the classroom (e.g. Berliner, Citation2004; Stigler & Miller, Citation2018; Werquin, Citation2010).

Nonetheless, empirical educational research has made remarkable progress in recent decades. Numerous empirical studies have been conducted with the aim of providing empirical evidence for the effectiveness of teacher education programmes, learning opportunities, interventions, and trainings. For example, in their oft-cited review, Cochran-Smith and Villegas (Citation2015) found more than 1,500 studies worth considering with respect to ‘mapping the landscape’ of teacher education research. They included teacher education effectiveness research (TEER) in their framework as one of the major fields of empirical research on teacher education. In addition to ‘handbook’-style articles providing overviews, other authors have synthesized the literature to offer more systematic insights into the field of empirical teacher education research, often connected to the question of teacher education effectiveness (e.g. Scheerens & Blömeke, Citation2016).

Although such reviews make significant contributions to the question of what empirical research on teacher education may comprise—including with regard to how teacher education is expected to be effective in preparing and educating teachers—, our scientific understanding of teacher education effectiveness as a research field remains limited regarding a more general and overarching perspective. This may be partly attributed to the heterogeneous approaches, which are difficult to compare (e.g. Kennedy, Citation2016). To the best of our knowledge, however, it is still necessary to synthesize the state of empirical teacher education research more specifically with regard to teacher education effectiveness, providing a better foundation for the following research questions:

What major theoretical frameworks are used?

Which outcome measures serve as criteria for teacher education effectiveness?

What measures and characteristics form the processes that are regarded as effective?

What central research gaps should be addressed in future research?

How TEER is grounded in overarching theories, frameworks, and conceptualizations is of particular interest, for example to fully understand how the ‘large number of small scale but often disconnected studies of teacher education practice’ can be evaluated (Rowan et al., Citation2015, p. 275). Following design principles of educational effectiveness research and the central assumption of educational productivity (as will be outlined in more detail in the next section), TEER conceptualizes learning outcomes as a dependent variable and processes as independent variables. Both the outcomes that serve as effectiveness criteria and the processes explaining these outcomes are the core constituents of TEER (König & Blömeke, Citation2020) and are, therefore, worth considering by specific research questions. Since we aim at identifying research gaps that should be addressed in future TEER, the fourth research question is most relevant with respect to any future efforts in the specific field of TEER. Answering these questions based on evidence that emerges from the existing syntheses of the literature may illuminate the orientation that future research efforts should prioritize. Findings may thus support the more systematic advancement of knowledge and strengthening the quality of research in the field of teacher education effectiveness, which is important for both the research discourse and educational policy (e.g. Blömeke et al., Citation2008; Grossman, Citation2008; Kaiser & König, Citation2019).

Given that empirical research on the effectiveness of teacher education has been synthesized by numerous reviews in recent decades, the present paper applies a systematic search of such literature reviews. Using 27 reviews relating to TEER that were identified through our search strategy, we adopt a broad understanding of teacher education (as a process of lifelong learning, following Day, Citation1999) as comprising all stages of teacher professionalization—namely, ITE, teacher induction, and TPD. Based on findings related to the four research questions mentioned, we ground a classification of basic distinctions for the various studies that the reviews synthesize. We discuss perspectives on how this classification might provide an orientation for future TEER studies.

Teacher education as an object for effectiveness examination

Research on teacher education effectiveness might be viewed in analogy to the research on teachers’ effectiveness: Empirical educational research on teachers’ effectiveness has largely focused on effective teaching (e.g. Hattie, Citation2012; Kyriakides et al., Citation2013; Muijs & Reynolds, Citation2005; Seidel & Shavelson, Citation2007), which is generally understood as those observable classroom processes, mostly attributable to teacher behaviour, that result in expected student learning outcomes (e.g. Brophy & Good, Citation1986). Applying the basic model assumptions of process-product examination, the relevant components of classroom instruction and learning environment characteristics (i.e. the process) are analysed in relation to their influence on student learning (i.e. the product). Research on effective teaching originated with Carroll (Citation1963), whose model considered time for learning, instructional quality, and learners’ cognitive prerequisites to be essential. Hitherto, many meta-analyses have sought to integrate findings from numerous effective teaching studies to identify the most crucial factors (e.g. Hattie, Citation2012; Seidel & Shavelson, Citation2007), thus offering systematic and integrated perspectives of multiple studies’ findings. Owing to the extensive empirical investigation into effective teaching and the significant role for the broader field of research on teaching, corresponding approaches have established the scientific status of a process-product research paradigm (e.g. Brophy & Good, Citation1986; Doyle, Citation1977; Gage & Needels, Citation1989).

In contrast to research on effective teaching, far less common is teacher education effectiveness research (TEER), although an increasing interest among researchers using teacher education as an object for examining effectiveness can be assumed (Cochran-Smith & Villegas, Citation2015; Hill et al., Citation2021; König & Blömeke, Citation2020; Scheerens & Blömeke, Citation2016). TEER generally follows the characteristics of effective teaching research (Scheerens & Blömeke, Citation2016, p. 72), whereby ‘the educational system is seen as a “black box”, within [which] processes or “throughput” take place to transform inputs into outputs’, completed by accounting for an environmental or context dimension. Similar to effective teaching, teacher education effectiveness holds the central assumption of educational productivity (Walberg, Citation2003), such as conceptualizing the statistical explanation of a learning outcome (dependent variable) using an equation that combines a set of variables (and their interaction) that serve as explanatory variables (independent variables).

TEER subjects teacher education to a degree of scrutiny. One reason for this lies in economic contexts that may require teacher education to exercise accountability regarding its productivity (e.g. Cochran-Smith & Villegas, Citation2015; Sultana, Citation2005). The various conceptions of ITE serve as another starting point. For example, Zeichner (Citation1993) distinguished four traditions in ITE programmes (see also Sultana, Citation2005): teachers as artists (implying that the individuals are innately gifted teachers); teachers as skilful individuals who can be trained; teachers as professionals tied to an academic tradition; and teachers as researchers or intellectuals. Sultana (Citation2005) considers the skilful and trained teacher to be most closely linked to a neo-liberal discourse in education. The development of standards and the testing of teachers’ abilities and skills—as part of the competencies they are expected to acquire during ITE and further develop as early career and in-service teachers during induction or TPD—cannot be considered independently from the economic, social, and cultural developments that have shaped teacher education over time (e.g. Staiger & Rockoff, Citation2010). In the discussion that follows, we consider this as an important discourse for the background or macro conditions for TEER.

Teacher competence as an outcome of teacher education effectiveness

Expectations of teacher education effectiveness have been linked to teacher competence. For example, international large-scale assessments—as conducted in the Teacher Education and Development Study in Mathematics (TEDS-M 2008, Tatto & Senk, Citation2011)—build on teacher competence frameworks to deploy survey instruments. For the first time, teacher professional knowledge was directly assessed on the basis of representative samples of future teachers from 17 countries worldwide, whereby the future teachers were assessed shortly before they became fully certified as professional teachers. Their professional teacher knowledge test scores were related to survey data on the learning opportunities to which the future teachers had been exposed during their ITE. The processes and characteristics of ITE programmes that future teachers had followed were related to the outcomes of ITE, thus examining teacher education effectiveness (Blömeke et al., Citation2011).

Further developments in teacher competence research, also influenced by TEDS-M, have fostered empirical research aimed at modelling and measuring teacher competence (Blömeke et al., Citation2015). Scholars broadly agree on the understanding that competences are context-specific, cognitive performance dispositions that are functionally responsive to situations and demands in certain domains (Kaiser & König, Citation2019). Models of professional competence highlight both cognitive and affective-motivational areas (Blömeke, Citation2017), typically with reference to Shulman’s (Citation1987) widely recognized work—in particular, his classification of teacher knowledge. More recently, substantial progress has been made towards the understanding that teacher competences comprise individual dispositions that remain relatively stable across different classroom situations—in particular, teacher professional knowledge—but that they also include situational facets, such as teacher noticing (König et al., Citation2022) or lesson planning (König & Rothland, Citation2022). Such ‘situation-specific skills’ are regarded as highly relevant in social contexts, determining how dispositions such as teacher knowledge translate into classroom performance (Blömeke et al., Citation2015).

Models outlining expected effects and relations between processes and outcome variables

Early approaches to teacher education effectiveness may be found in those studies that investigated how teachers’ certificates and qualifications relate to student learning (e.g. Cochran-Smith & Zeichner, Citation2005; Darling-Hammond et al., Citation2005). A major limitation, however, was that these teacher indicators appear distal in terms of explaining the statistical variation of instructional quality and students’ learning progress. As teachers transition from pre-service training to in-service teaching, processes of their further career development that are difficult to control in empirical study designs come to light. The further back in time teachers’ certificates and qualifications date, the noisier the relationship between teacher indicators and student achievement data is likely to be (e.g. Darling-Hammond et al., Citation2005). By contrast, study designs that link directly assessed teacher knowledge to processes of instructional quality and student achievement data potentially allow more substantial and precise correlations (e.g. Baumert et al., Citation2010; Blömeke et al., Citation2022). Even if such studies do not address the precise relevance of teacher education to the teaching profession, they constitute an important reference for the assumption that teacher knowledge—which is considered to be a valid predictor for the successful completion of professional tasks such as teaching—may also be used as a measure for evaluating pre-service teacher learning outcomes of ITE (Darling-Hammond, Citation2006; Guerriero, Citation2017).

Educational researchers have used these assumptions to develop theoretical frameworks. For example, Kaiser and König (Citation2019) suggest including measures of teacher professional competence as both an explanatory and a dependent variable within an integrated overall model (see ). In other words, teachers’ professional competence is regarded as an outcome of TEER and a predictor for effective teaching. As a dependent variable, the model suggests that teachers acquire their professional competence through a complex interplay of learning dispositions upon entry to ITE (including, e.g. their motivation for choosing teaching as a career choice) and the learning opportunities to which they are exposed during ITE. Regarding teacher professional competence as an explanatory variable, the model suggests that it influences the process characteristics of teaching and learning in the classroom in addition to other professional demands, such as teacher well-being or professional school development. Given that the model highlights the principles of how teacher education can relate to professional competence and teachers’ mastery of professional tasks, a broad application seems possible in addition to extensions, therefore implying that the model can also be used to describe effectiveness of teacher education in the broad sense, including ITE, induction, and TPD.

Figure 1. Teachers’ professional competence as an outcome of TEER and predictor for effective teaching (Kaiser & König, Citation2019).

Research questions

Owing to the need to synthesize the state of empirical teacher education research more specifically with respect to teacher education effectiveness, we aim to provide better insights by answering the following research questions (RQ):

RQ1: What major theoretical frameworks are used?

RQ2: Which outcome measures serve as criteria for teacher education effectiveness?

RQ3: What measures and characteristics form the processes that are regarded as effective?

RQ4: What central research gaps should be addressed in future research?

Regarding RQ1, we assume that, in our literature review, it will be necessary to distinguish at least three levels of framework from one another: framing TEER on the very broad level of macro conditions (e.g. socio-economic conditions) that have shaped teacher education over decades, with implications for TEER (Staiger & Rockoff, Citation2010); theories, theoretical frameworks, or models that have a more general scope but are directly significant for understanding TEER (e.g. classification of teacher knowledge; Shulman, Citation1987); and the theoretical framing for a specific topic to be examined and applied in the context of TEER (e.g. effectiveness of mathematics as a subject in teacher education; Tatto & Senk, Citation2011).

Regarding RQ2, we consider that the rigorous measurement of outcomes is essential for TEER. We expect that several study outcomes will rely on the concept of teacher competence—comprising both cognitive and affective-motivational dispositions and situation-specific skills—being extended by outcomes that reflect long-term effectiveness, such as indicators of teaching practice or student learning outcomes (). However, it will also be important to investigate what topical focus on TEER has been prioritized in recent decades.

Regarding the complexity of teacher education that must be accounted for in TEER, with RQ3, we anticipate considerable variance in the measures and characteristics that form the processes under investigation as potentially effective treatments in TEER. A hierarchy may be regarded as having, first, structural elements, such as a training phase or a training sequence (e.g. bachelor and master structure or the transition from pre-service teacher training into in-service professional teaching); second, the level of programmes (e.g. a study programme in ITE, a systematic/long-term TPD programme), whereby the research either focuses on the effectiveness of a specific programme (compared to other programmes) or is located within a specific programme (e.g. interventions targeting primary school teachers); third, coursework as the typical level of opportunities to learn, which may take diverse forms, including seminars, lectures, or concrete training interventions in ITE and/or TPD; and fourth, practical learning opportunities, such as practicum, internship, or other types of field placement. Independent of such a hierarchy of effective processes, a topical focus might constitute the effective processes or characteristics rather than a clear-cut outline of coursework or programme intervention.

Finally, RQ4 concerns research desiderata to be addressed in the future, and we expect that these will be related to at least three dimensions: theory development, the methodology of the reviewed studies, and the topical focus of TEER.

Methodology

To address our research questions, we began preparing a systematic search for existing literature reviews on TEER. That is, we intentionally refrained from conducting a systematic search of individual empirical studies related to TEER for two reasons: First, well-known reviews, such as the frequently cited overview of teacher education research by Cochran-Smith and Villegas (Citation2015), have already demonstrated the existence of hundreds of empirical studies that would potentially fall into consideration, leading to an excessively complex and fine-grained database that would not be suited to the investigation of our research questions, at least for the capacity of our research team. Second, more importantly, a quick literature search revealed a sufficient number of literature reviews to be acknowledged in the field of TEER, at least, when viewed from the broader standpoint that underlies our research questions. However, to the best of our knowledge, no synthesis of such literature reviews has yet been carried out. For various reasons, as mentioned in the introduction, such a synthesis is particularly timely.

Our approach to synthesizing such literature reviews may permit broad comprehensive insights into the current state of TEER for the first time. We consider this overarching level appropriate to our research questions, in that it allows us to draw relevant conclusions on a more general, overarching level. However, even on the basis of a preliminary search for literature reviews related to TEER, it became clear that the intended synthesis should build on reviews of various types to account for the plurality of synthesis methods mirroring the diversity of approaches that is typical of teacher education research (Cramer et al., Citation2023). This was supported by following recommended classifications into systematic, scoping, and narrative reviews (e.g. Horsley, Citation2019). Moreover, we did not differentiate between qualitative and quantitative reviews. To ensure a clear presentation, we followed Page et al. (Citation2021) ‘PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration’.

Systematic literature search

For our systematic literature search, conducted in March 2023, we used two literature databases: Web of Science (WoS) and Education Resources Information Center (ERIC). Given that the two databases differ with respect to structure, search function, and ability to export the results, we shall first describe the procedure followed for each database before merging the results of the different searches.

Initially, we performed the search on WoS using the search term ‘teacher education’ AND ‘effectiveness’, with the quotation marks indicating a fixed pair of terms to be searched in the education section. We checked for consistency in titles, abstracts, and author keywords. ‘effectiveness’ was used to filter studies that address the effectiveness of teacher education. The 510 results were further filtered by ‘document type’ (Article) and ‘Language’ (English and German as frequently used languages) using WoS’s automation tools and then exported to Excel. We repeated the same procedure for the combinations ‘teacher training’ AND ‘effectiveness’ (n = 414) and ‘professional development’ AND ‘teacher’ AND ‘effectiveness’ (n = 737).

For the ERIC database, we used the ERIC API to simplify the result export process and performed six individual search queries using the same search terms as used for WoS. For example, we searched for matching results within the titles using title: ‘teacher education’ AND title: ‘effectiveness’ and retrieved 55 peer-reviewed articles, which we exported to Excel. Similarly, we searched for matching results in abstracts using description: ‘teacher education’ AND description: ‘effectiveness’ and exported 789 peer-reviewed articles. It was necessary to use ‘description’ rather than ‘abstract’ because the labels differ between the traditional ERIC search query and the query via the API. The results for the other combinations in title and abstract were obtained in the same way. In the case of description: ‘professional development’ AND description: ‘effectiveness’ AND description: ‘teacher’, several export cycles were necessary, given that only 2,000 entries can be exported per cycle. In total, 3,497 peer-reviewed articles were identified. Filtering by peer-review was performed in Excel only. The corresponding articles are automatically marked with ‘T’ for ‘true’ during export. The actual number of exported articles is therefore significantly higher but not relevant for the focus on peer-reviewed chosen here.

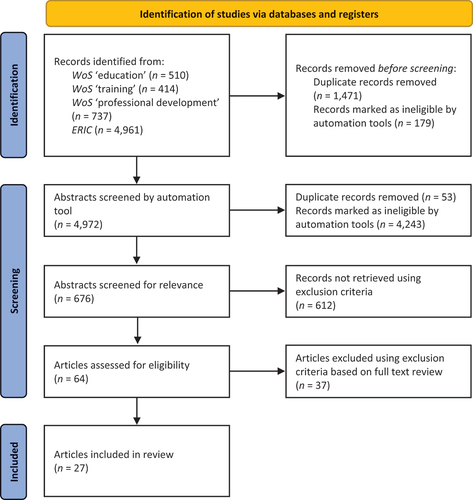

After merging the results from both databases and eliminating 1,471 duplicates, we filtered the remaining 4,972 records using automation tools. For this purpose, we used the search function in Excel and marked all those abstracts that contained ‘review’ (n = 452) or ‘defin’ (n = 277) to include only those articles that were reviews themselves. Our rationale for conducting an additional search for the term ‘defin’ was based on our experience that reviews often present the definition of the construct under investigation. To accommodate for the different variations of the terms ‘define’ and ‘definition’, we utilized the root word in our automated search. This left 729 articles, of which 53 were duplicates. Therefore, we identified 676 articles for screening (). Their references were exported to Excel. At least two members of our author team screened all titles and abstracts carefully and narrowed down the selection to articles containing a literature review related to TEER, using the following exclusion and inclusion criteria.

Figure 2. Flow diagram (following the guidelines of Page et al., Citation2021).

Exclusion criteria: (1) We excluded articles that reviewed teaching or teacher effectiveness research but did not provide a synthesis of findings on TEER. Several of these articles only briefly discuss the implications of teacher effectiveness research for teacher education, which may explain why they were first identified for screening. (2) We excluded numerous articles that turned out to be single empirical studies (e.g. intervention study in ITE) that used the term ‘review’ in their abstract only in relation to the introductory section that sought to briefly familiarize the reader with previous research rather than synthesizing or further analysing the results of multiple studies in appropriate depth. Moreover, we excluded articles that (3) had a different topic or thematic focus to teacher education effectiveness, (4) portrayed teacher education programmes without any clear consideration of TEER, or (5) turned out to be commentaries rather than narrative reviews of empirical studies on TEER (e.g. Darling-Hammond, Citation2020).

Inclusion criteria: We included those publications that (1) provided a synthesis and (2) based their syntheses on relevant empirical investigations of teacher education effectiveness. Accounting for the plurality of methods applied in educational research, such syntheses may vary with respect to systematic level (ranging from narrative via scoping to systematic review; e.g. Horsley, Citation2019). (3) Even reviews that did not emphasize the term ‘effectiveness’ were included if they reviewed relevant empirical studies contributing to the broader field of TEER (e.g. Hogan et al., Citation2003).

The application of the exclusion and inclusion criteria in screening the abstracts eliminated 612 articles, leaving 64 articles whose abstracts generally met the inclusion criteria. Again, at least two members of our author team then reviewed the full texts of these 64 articles for eligibility and excluded a further 37 for which it had been difficult to apply our exclusion and inclusion criteria exclusively on the basis of title, abstract, and keywords. As such, the final corpus for this review comprises 27 articles ().

Table 1. Classification of papers, including number of reviewed studies and citation.

The articles included in our review were published between 1993 and 2023 (we abstained from using publication year as an exclusion criterion), thus encompassing three decades of TEER studies. They relate to ITE, induction, and/or TPD and vary with respect to systematic level: 19 are systematic, 2 may be denoted as scoping, and 6 are narrative reviews. The articles’ topical focus varies: some publications synthesize the state of TEER from a broad perspective, thus providing overviews, which closely approaches the major aim of our review. These overview publications can be regarded as the most valuable to our review goals. Two further publications (Hogan et al., Citation2003; Kyriacou, Citation1993) are related to teacher expertise development during teacher education, therefore also providing another type of overall perspective. Most of the publications, however, adopt a particular topical focus. Priority is given to diversity and educational technology, but lesson studies and lesson planning are also of substantial interest. Other topics, such as assessment or moral reasoning, are more specific.

The 27 reviews were created by authors from various countries (see Appendix 2), with three reviews created by authors from two different countries respectively. Nearly every second review originates from North America (13 out of 27 papers), followed by those originating from Europe (8 papers) and Asia (6 papers). Only two papers originate from Oceania and only one paper originates from South America, and there is no paper with authors from Africa (see Appendix 2, for assigning countries to continents). Although the perspective of the Western world is strongly represented, it is evident that publications from various countries and continents are part of our corpus, which might show that TEER has international significance.

Data analysis

Given that our approach to synthesizing the various forms of literature reviews aims to map TEER across its entire breadth and depth, we decided to define our approach as ‘scoping review’ rather than ‘systematic review’. Our synthesis should serve to summarize the evidence from existing literature reviews while also focusing on the identification of knowledge gaps, the scope of the existing literature from a broader standpoint, and the need to clarify concepts (Munn et al., Citation2018).

To analyse the reviews in relation to the focus of our research questions, we developed analysis categories: first, we drafted these categories and after having applied them to all publications, we then refined the categories and applied them once again as final analysis categories (). Appendix 1 provides short descriptions for each category, and Appendix 2 contains an overall summary table from which our results are derived.

Table 2. Analysis categories (for short descriptions, see Appendix 1).

Owing to the heterogeneity of the studies, we decided to apply thematic analysis using the analysis categories as guidelines. Where possible, we applied low-inference coding of the analysis categories that would be typical of content analysis (Dixon-Woods et al., Citation2005). In most cases, however, analytical categories required a thorough thematic analysis for which we produced summaries that provided descriptions of key points (see Appendix 2). The breadth of analysis categories made it necessary to provide detailed description of the approaches deployed in each review in the following section ‘Findings’.

Findings

A general reading of the publications reveals that teacher education, broadly understood, relates to both the ITE and TPD segments, and even intermediate stages, such as induction, are addressed (see ). Several of the reviews focus either on ITE or on TPD, but given that several reviews highlight the overlap, TEER cannot be associated exclusively with a single segment. Regarding their function in the teachers’ career and professionalization of teachers it is clear that ITE, which concerns the provision of training programmes, is integral to the teacher qualification process, whereas induction and TPD serve as modes of support or training for early career or in-service teachers (e.g. Perry et al., Citation2021). For this reason, outcome expectations may differ: Whereas ITE is aligned with pre-service teacher outcomes that may be a part of teacher certification, TPD depends on the student outcomes of the supported or trained teacher (Kennedy, Citation2016).

RQ1: What major theoretical frameworks are used?

Our analysis relating specifically to RQ 1 is based on three analytical criteria (see and Appendix 1 and 2). First, we wish to investigate relevant descriptions of background or macro conditions influencing TEER. Sultana (Citation2005) and Cochran-Smith and Villegas (Citation2015) provide such a framing in relating TEER to information-based economy-influencing educational systems. They highlight that the need for evidence cannot be separated from social, cultural, and economic movements that have shaped society’s expectations of educational institutions in general and, more specifically, the teaching profession and the ways in which teachers are prepared, qualified, and supported. Teachers are central agents who play a decisive role in implementing innovations in the educational system, and modern society’s conception of teaching and learning has (implicitly) incorporated constructivist ideas, raising expectations regarding the individual teacher’s responsibility. Whereas only two overview publications (Cochran-Smith & Villegas, Citation2015; Sultana, Citation2005) provide background or macro condition framing, others at least briefly take up the discourse on teacher education effectiveness and use it as a reference point for the overall framing of their publication—for example, linking TEER to lesson planning competence (König & Rothland, Citation2022) or the high costs of TPD (Kraft et al., Citation2018).

Second, in our analysis relating to RQ 1, we found that some publications ground their review in a theoretical framework—that is, a model, framework, or theory significant for understanding TEER. Cochran-Smith and Villegas (Citation2015) suggest a taxonomy that structures empirical research on teacher education. They assign TEER to a component that comprises research on teacher education accountability and policy as well. In doing so, they position TEER within an overall theoretical/analytical framework of research on teacher education. Sultana (Citation2005) underpins his narrative review with the classification of key traditions of teacher professionalism, as introduced by Zeichner (Citation1993): teachers as artists (implying that the individuals are innately gifted teachers); teachers as skilful individuals who can be trained; teachers as professionals tied to an academic tradition; and teachers as researchers or intellectuals. In their reviews, Kyriacou (Citation1993) and Hogan et al. (Citation2003) relate assumptions regarding TEER to teacher expertise, using the well-known classification of teacher knowledge developed by Shulman (Citation1987, p. 8), which highlights teachers’ pedagogical content knowledge as the ‘amalgam of content and pedagogy’, and this classification serves as an organizational framework for the selection of studies in their reviews. Scheerens and Blömeke (Citation2016) present a specific TEER model, supported by principles of educational effectiveness research.

Less concise, but nonetheless relevant, the reviews on TEER in the field of lesson studies frame the topic as a constructivist approach (Kanellopoulou & Darra, Citation2019) or introduce it as a TPD model for enhancing agency and reflective practice among language teachers (Ustuk & Çomoglu, Citation2019). In their review on lesson planning, König and Rothland (Citation2022) frame their developed definition of lesson planning competence in the context of TEER, with justifying references to competence models, teacher expertise research, and, again, the teacher knowledge classification by Shulman (Citation1987).

However, all other studies abstain from providing a background or macro framing, choosing not to position their review within a TEER theoretical framework. Rather, they apply a topical focus, whereby a specific topic is examined and applied in the context of TEER (e.g. CRP definition provided; Bottiani et al., Citation2018). While these are relevant for the particular focus (e.g. moral reasoning, special educational needs, assessment literacy, etc.), they provide no theoretical framing of TEER as a fundamental approach.

RQ2: Which outcome measures serve as criteria for teacher education effectiveness?

As the reviews concerning the development of expertise as part of the pre-service teacher qualification and early career or in-service teacher professional learning process show (Hogan et al., Citation2003; Kyriacou, Citation1993), teacher cognition and teachers’ cognitive representation of typical teaching problems are an essential reference for the definition of possible outcome measures in teacher education. For example, Kyriacou (Citation1993, p. 79) not only reports on 13 empirical studies that provide information about ‘the type and nature of the expertise that develops’ among pre-service teachers during initial teaching and when they enter the teaching profession, but also analyzes nine studies that highlight key factors that emerge during ITE and affect such development.

Kyriacou (Citation1993, p. 85) concludes that the term ‘classroom expertise’ is itself complex and problematic. It seems to combine notions of both a sound knowledge base and skilled performance. Such a conception of expertise has been explicitly addressed and articulated within the aims of many initial training courses and can be seen to lie at the heart of the wider notion of ‘professionalism’ (see Woolfolk, 1989). As this definition of classroom expertise goes beyond knowledge, Kyriacou (Citation1993, p. 85) suggests that ‘key teaching skills’ should be fostered by the end of ITE, such as ‘planning and preparation, lesson presentation etc.’, backed up by empirical evidence outlined in his review of studies on novice teachers’ expertise.

Hogan et al. (Citation2003) focused on those studies that, on the basis of comparisons between novice and expert teachers, provide insights into how the two groups may mentally represent features of the classroom. Like Kyriacou (Citation1993), they analysed several studies retrieved from novice-expert teacher research, first in the field of content knowledge/pedagogical content knowledge, then in the field of general pedagogical knowledge, suggesting implications for expert teachers’ knowledge and skills as possible learning outcomes of teacher education. However, they draw no direct link to teacher education effectiveness.

Scheerens and Blömeke (Citation2016) see TEER from the perspective of school effectiveness and teaching effectiveness research. They argue that outcomes of TEER should be teacher variables that have turned out to be important in school and teaching effectiveness research. In modelling teaching effectiveness (Scheerens, Citation2023), teacher characteristics comprise knowledge, motivations, beliefs, whereby, similar to reviews by Kyriacou (Citation1993) and Hogan et al. (Citation2003), Shulman’s (Citation1987) classification of professional knowledge serves as a major point of reference (Scheerens & Blömeke, Citation2016, p. 73). These teacher characteristics are synthesized by the term ‘professional competencies’ in relation to pre-service teachers and are systematically related to teacher education, using a ‘multi-level teacher education effectiveness model’ (Scheerens & Blömeke, Citation2016, p. 76).

Most reviews espouse this notion of teacher competence as comprising knowledge, skills, and attitudes: Explicitly, 21 reviews account for knowledge, 18 for skills, and 16 for attitudes (see Appendix 2). This is applied to the particular topic under review—for example, special educational needs/inclusive education (Kurniawati et al., Citation2014), blended learning (Ma et al., Citation2023), lesson planning (König & Rothland, Citation2022), promoting health (Shepherd et al., Citation2016), and STEM (Zhang et al., Citation2022). Significantly, about two-third of the studies reveal explicitly the drive to change those constructs (see Appendix 2), making increased competence the true outcome of TEER (e.g. Bottiani et al., Citation2018; Gentry et al., Citation2008; König & Rothland, Citation2022; Kurniawati et al., Citation2014; Menekse, Citation2015; Mesutoglu & Baran, Citation2021; Shepherd et al., Citation2016; Spooner-Lane, Citation2017). Moreover, several reviews go a step further and also consider instructional practice and/or student achievement (Snell et al., Citation2019; Spooner-Lane, Citation2017, Kraft, Citation2018; Vernon-Dotson et al., Citation2014) as external criteria. In particular, those reviews prioritize TPD, wherein instructional practice and student achievement relates to the professional context of the in-service teachers participating in the TPD. The fact that instructional practice and student achievement are rarely used as external criteria for TEER among pre-service teachers may be the result of ITE’s curricular limitations, whereby pre-service teachers, even if provided with practical learning opportunities, still have little responsibility for classroom teaching (König & Rothland, Citation2022).

RQ3: What measures and characteristics form the processes that are regarded as effective?

Based on our analyses categories (), surprisingly few reviews include structural elements that were examined with respect to their effectiveness. Cochran-Smith and Villegas (Citation2015) highlight those empirical studies that compared the effectiveness of traditional and alternative pathways into the teaching career. Kyriacou (Citation1993) related changes in teacher knowledge as part of teacher expertise and effective outcomes of teacher education to the specific transitions taking place within teacher training and early career system (see also Spooner-Lane, Citation2017). We expected explorations of TEER, for example, in relation to the bachelor-master-induction career structure, but none of the reviews specifically approached TEER from this perspective. Scheerens and Blömeke (Citation2016) were alone in referring to TEER on the level of teacher education systems, with implications of educational governance issues on the state level—a perspective that is only exemplified by TEDS-M (Tatto & Senk, Citation2011).

The level of programmes (e.g. a study programme in ITE, a systematic/long-term TPD programme) appears in several reviews that aim to provide an overview (Cochran-Smith & Villegas, Citation2015; Sultana, Citation2005). The more specific the topical focus of a review is, the less the programme appears to come into play. Exceptions include Cummings et al. (Citation2007), Kurniawati et al. (Citation2014), Vernon-Dotson et al. (Citation2014), and Zhang et al. (Citation2022). For example, Vernon-Dotson et al. (Citation2014) included studies in their review that evaluate distance/hybrid programmes or compare distance education delivery and traditional/face-to-face programmes.

The most dominant category of measures and characteristics-forming processes that is regarded as particularly effective, however, is coursework, which is prioritized in 22 of the 27 reviews (i.e. more than 80% of reviews). This is true of both professional development programmes (Bottiani et al., Citation2018; Menekse, Citation2015; Snell et al., Citation2019; Perry et al., Citation2021; Juanjuan & Mohd Yusoff, Citation2022; Gentry et al., Citation2008, Kraft, Citation2018; Mesutoglu & Baran, Citation2021; Zhang et al., Citation2022) and courses in ITE serving as the unit of treatment (Kyriacou, Citation1993; Ma et al., Citation2023; Shepherd et al., Citation2016; Vernon-Dotson et al., Citation2014). In relation to this particular topic, the two reviews on lesson study focused on coursework linked to practice (Kanellopoulou & Darra, Citation2019; Ustuk & Çomoglu, Citation2019). Appendix 2 provides some more details about the content of the coursework examined by the reviews.

However, the category of teaching practice appeared less frequently than that of coursework (8 out of 27 reviews, i.e. about 30% of reviews), though several reviews did take it up as a relevant field of TEER (Kurniawati et al., Citation2014; Kyriacou, Citation1993; Sultana, Citation2005). Teaching practice may offer the opportunity to apply what coursework has sought to convey, but this is not necessarily intended systematically (see, e.g. Perry et al., Citation2021; Shepherd et al., Citation2016; Vernon-Dotson et al., Citation2014). Interestingly, Scheerens and Blömeke (Citation2016) highlight the high expectations that teaching practice must fulfil in teacher education, but research has identified several negative side-effects (e.g. Sultana, Citation2005, p. 231), such as the danger that student teachers tend to orient themselves towards ‘what works’, which would clearly follow the apprenticeship model of teacher education while dismissing any notion of teachers as professionals or intellectuals (Zeichner, Citation1993). Practice has been related to both lesson study and investigation into teachers’ lesson planning competence (Kanellopoulou & Darra, Citation2019; König & Rothland, Citation2022; Ustuk & Çomoglu, Citation2019).

RQ4: What central research gaps should be addressed in future research?

The reviews’ conclusions relate to the need for methodological rigour rather than theory development in TEER. The theoretical frameworks underlying the outcome measures appear to be an object of criticism on a theoretical but even more on a methodological level.

For example, as early as Hogan et al. (Citation2003), it was criticized that cognitive representations are not clarified by existing research. Although two decades have since passed, this issue has been taken up by a growing research field of investigating teacher competence (e.g. König & Rothland, Citation2022; Scheerens & Blömeke, Citation2016), the point made by Hogan et al. (Citation2003) still appears to relate to the open question of whether assessments of professional knowledge as an outcome of teacher education are sufficiently aligned with the professional demands of the teaching profession. In their review on lesson planning competence, König and Rothland (Citation2022) criticize existing models that describe teachers’ professional competence on the grounds that they are partly underspecified with respect to the complex demands of lesson planning and argue that theory development is required to integrate those facets of competence in teacher competence models that go beyond mere teacher knowledge. The need to develop or expand theories of how teachers learn, as facilitated by ITE and TPD, is emphasized (Avalos, Citation2011; Kennedy, Citation2016; Parkhouse et al., Citation2019), and appears to be highly relevant to further attempts to profile TEER in general.

Some methodological concerns arise in relation to the limitations of outcome measures, as noted above on the level of theoretical desiderata. In this sense, further desiderata emerge on the level of topical focus. Therefore, specific content should be addressed by the conceptualization of outcome measures, such as dealing with diversity or information technology (Knight & Wiseman, Citation2005; Sultana, Citation2005). This criticism has been less prominent in more recent reviews.

Most methodological concerns relate to the various limitations of study designs appropriate to TEER. Study designs that provide more detailed insights in teacher education effectiveness are required (Cochran-Smith & Villegas, Citation2015). Overall, the investigation or evaluation of the effectiveness of specific teacher education characteristics in terms of ‘differential effectiveness’ (Scheerens & Blömeke, Citation2016) is highlighted as a research desideratum. For example, detailed analyses of the relationship between indicators of specific learning opportunities, such as characteristics of coursework and effectiveness outcomes, are sparse (König & Rothland, Citation2022), and it is thus necessary to identify the salient features of teacher education programmes (Vernon-Dotson et al., Citation2014). Clearly, evidence for teacher education effectiveness may be provided on a global level, but the more specific processes underlying such effectiveness must be accounted for by future research.

Regarding TPD, Kennedy (Citation2016) has criticized the fact that while numerous TPD articles are published annually, most do not provide any empirical evidence. For TEER in the field of TPD, several reviews have concluded that follow-up measurements and the integration of student learning data are important (Bottiani et al., Citation2018; Kurniawati et al., Citation2014) that replication studies are required (Juanjuan & Mohd Yusoff, Citation2022; Parkhouse et al., Citation2019), and that more rigorous experimental designs should be implemented (Kraft et al., Citation2018). The latter also relates to TEER desiderata in the ITE field (Shepherd et al., Citation2016; Vernon-Dotson et al., Citation2014). Innovative interventions and training in both ITE and TPD require rigorous research designs that account for typical standards in experimental research (Campbell & Stanley, Citation1963). This includes, for example, placing greater emphasis on the role that teacher motivation plays in TPD participation (Kennedy, Citation2016).

Discussion

Over decades, the quality of teaching and teacher education has recurrently become subject to public scrutiny and various educational policy and reform debates in many countries worldwide (Darling-Hammond, Citation2020; Kaiser & König, Citation2019; OECD, Citation2018). Many researchers have conducted empirical studies on the effectiveness of teacher education. As a consequence, reviews were published synthesizing the findings from those empirical studies (as early as three decades ago; Kyriacou, Citation1993). The present synthesis now brings together a substantial number of those reviews that relate to TEER. As we understood TEER broadly, all stages of teacher professionalization, from ITE to induction and TPD, were accounted for by our synthesis.

Considering teacher education as an object of effectiveness examination, we focused the general question of how processes of qualifying and training of pre-service or in-service teachers affect intended learning outcomes (products) relevant for the teaching profession. A systematic search for 27 reviews fulfilling various inclusion criteria allowed us to apply analysis categories and synthesize findings finally deriving from over 2,000 single studies covered by these reviews. Based on this, we aimed to find answers to four research questions: findings on major frameworks (RQ1), findings on outcome measures (RQ2), findings on processes (RQ3), and what central research gaps would exist in the field of TEER (RQ4).

Regarding RQ1, our findings show that descriptions of background or macro conditions influencing TEER were sparse. At least some publications took up briefly the discourse on teacher education effectiveness and used it as a reference for the overall framing of their publication. A good number of reviews used a theoretical framework significant for understanding TEER. However, most of the reviews abstained from providing a background or macro framing. They did not position their review within a TEER theoretical framework. Instead, they chose to apply a topical focus, that is, a specific topic is examined and directly applied in the context of TEER. Although such applications are doubtlessly relevant for the particular topical focus, the discourse on theoretical framing of TEER as a central approach is virtually not addressed. Therefore, we conclude that a rough distinction of reviews can be made between those highlighting the relevance of a topic with the need for investigating teacher education effectiveness focusing that topic specifically and, in contrast to this, reviews that build on models that frame teacher education effectiveness with its underlying research from a more general standpoint. Whereas the first review type applies effectiveness research, the second intends to provide appropriate grounding for TEER.

RQ2 referred to the outcome measures served as criteria for TEER. One of the major findings is that perspectives from the research on teacher cognition, expertise, and knowledge (Hogan et al., Citation2003; Kyriacou, Citation1993; Shulman, Citation1987) have early shaped our understanding for teachers’ professional knowledge and skills as relevant learning outcomes of teacher education. However, only more recent reviews directly link these outcomes to teacher education effectiveness, also with extensions of motivations and beliefs, and synthesized by the term ‘professional competencies’ (Scheerens & Blömeke, Citation2016). Most reviews espouse this notion of teacher competence as comprising knowledge, skills, and attitudes, being applied to a range of topics (e.g. lesson planning, promoting health, STEM). Numerous studies aiming at changing those constructs, making increased competence the true outcome of TEER. Besides, some of the reviews, especially those addressing TPD, go even a step further and also account for instructional practice and/or student achievement as external criteria. This shows that outcome measures of TEER are complex and multidimensional, which corresponds to the recent developments already mentioned in the introduction—for example suggesting the modelling of teacher competence as continuum (Blömeke et al., Citation2015) from teacher disposition (such as knowledge), through situation-specific skills (such as lesson planning, König & Rothland, Citation2022, or teacher noticing; König et al., Citation2022), to teacher performance affecting instructional quality and student learning (Blömeke et al., Citation2022).

With RQ3, we asked for processes that are regarded as effective according to the reviews’ findings. Few reviews contained structural elements that were examined regarding their effectiveness (e.g. traditional vs. alternative pathways; transition from training into teaching; teacher education systems) or the level of programmes (e.g. comparison of distance education delivery of programmes and traditional/face-to-face programmes). However, coursework was the most dominant category of measures and characteristics-forming processes (22 out of 27 reviews). Whereas coursework was in three reviews even structurally linked to practice (by both reviews on lesson study and investigation into a teacher’s lesson planning competence), the category of teaching practice was far less accounted for than coursework (8 out of 27 reviews), clearly showing a lacuna in TEER (Lawson et al., Citation2015).

We used RQ4 to identify research gaps that future research should address. One of the major findings seems to be that the reviews highlight in their conclusions the need for methodological rigour rather than theory development in TEER. The theoretical frameworks underlying the outcome measures appear to be an object of criticism on a theoretical but even more on a methodological level. This relates to development of existing models describing the professional competence of teachers (e.g. König & Rothland, Citation2022) as well as developing or expanding theories of how teachers learn as facilitated by ITE and TPD (Kennedy, Citation2016; Parkhouse, Citation2019). Another major concern relates to limitations of study designs. More detailed insights in teacher education effectiveness, in-depth analyses of ‘differential effectiveness’ (Scheerens & Blömeke, Citation2016) are highlighted as research desiderata. Whereas evidence for teacher education effectiveness might exist on a global level, future research should disseminate findings on the level of the more specific processes underlying such effectiveness. Several other methodological concerns are addressed (e.g. in particular related to TPD: follow-up measurements, inclusion of student learning data, fulfilling standards of experimental research etc.) showing that TEER still has to be pushed forward to a significantly higher state of rigorous empirical educational research.

Teacher education effectiveness as an emerging research paradigm

Our synthesis of 27 reviews on TEER published over three decades shows that TEER has its own history of theory and methodology. Such problems may impede our idea to systematically compare and analyse the selected reviews and their findings, but our analysis at the same time proliferated findings that relate to four relevant research questions at least on a more global level. These findings are promising, because of the fact that across all reviews, assumptions could be identified that more or less contribute to a shared understanding of conceptual framing of TEER. Researchers were able to construct to some extent well-organized studies in various educational contexts, which were synthesized by narrative, scoping, and systematic reviews. At the same time, further development in theoretical foundations in the field of TEER is clearly needed. Moreover, TEER must be profiled to reach a methodologically more advanced level. If developments that we were able to trace back over the last three decades will continue systematically over another decade and beyond, we conclude TEER can be considered as an emerging educational research paradigm. This conclusion is supported by the fact that the number of reviews published until 2023 has clearly increased when looked at in five-year-long intervals ()—alongside with their citations (, last column), indicating their impact.

To promote the development of theoretical foundation in the future, we in the following suggest a first processes-and-criteria classification (PCC) of basic distinctions of the various studies synthesized by the reviews (). Although this PCC remains on a global level and does not claim to be comprehensive, it nevertheless may provide an orientation for future TEER. Since the PCC grounds in the various findings from our synthesis, it may support to systemize future empirical studies of TEER as already suggested by Rowan et al. (Citation2015) who for example similar to Blömeke et al. (Citation2008) criticized that TEER studies often remain disconnected. The PCC may support further theoretical development in the field of TEER, facilitating to connect studies to each other in the future.

First of all, in our analysis we were able to find information on processes (RQ3) and criteria (RQ2) as part of model assumptions and even theoretical frameworks (RQ1). This leads us to a matrix of processes and criteria () that are general constituents of TEER. Criteria are operationalized into outcomes, as our findings for RQ2 showed. Typically, they are construct-related when considering outcomes per se. As already suggested by (Kaiser & König, Citation2019), most of the 27 reviews conceptualize outcome measures with reference to the notion of teacher competence. Although scientific progress in the field of teacher competence over the last decade can be observed (e.g. Blömeke et al., Citation2022), further efforts have to be made. Theoretical foundations of constructs are needed as well as theoretical frameworks addressing relationships between such constructs (Darling-Hammond, Citation2006). In TEER, however, constructs have to be related to a curriculum (e.g. learning opportunities of an ITE programme; a training programme for TPD; e.g. Flores, Citation2016), with the important implication for driving change of the constructs (e.g. knowledge that can be acquired by pre-service teachers through specific learning opportunities they are exposed to). At the same time, in many reviews, outcomes were justified by linking them to professional demands of teachers. Again, further efforts have to be made regarding specifying (e.g. Darling-Hammond & Bransford, Citation2007) and updating (e.g. Karsenti, Citation2019) those professional demands.

How processes are shaped can be looked at from at least three perspectives: First, following our RQ3 analysis criteria, there are important variables on a structural level (e.g. segments, transitions, programmes), but coursework was most dominant, which fits best to the level of intervention. Beyond structural and interventional levels, adaptive level such as individual coaching of in-service teachers may form another more global category of institutional organization that needs to be considered as processes in TEER as well. Taking together methodological findings, but also research desiderata related to research designs (RQ4), a general distinction can be made between survey studies (e.g. TEDS-M, Scheerens & Blömeke, Citation2016) and experimental studies (e.g. Kraft et al., Citation2018). Finally, following Galluzzo and Craig (Citation1990), we distinguish TEER towards its scope, that is, whether it aims at programme evaluation only or goes beyond towards programme validation. Programme evaluation studies mainly focus on possible relationships between processes and criteria within ITE or TPD, whereas approaches aiming at programme validation may aim at validating evaluation findings by further evidence in teachers’ mastering of professional demands as suggested by (Kaiser & König, Citation2019). For example, some research studies investigated teacher education effectiveness by following teacher education graduates into classroom teaching (Rowan et al., Citation2015). The vast majority of empirical studies underlying our synthesis is restricted to programme evaluation, whereas the need for programme validation has been clearly stressed as a research gap (RQ4) that future TEER designs should address.

Limitations and outlook

Our approach to synthesize reviews in the field of TEER has several limitations. We know that more reviews exist that may contribute to the discourse on designing ITE or TPD, also related to how teacher competence development can be fostered. However, through the literature selection process, we identified reviews that did not relate their approach to TEER sufficiently (e.g. Fernández-Batanero et al., Citation2022) or had a particular focus on a specific topic (e.g. Hascher & Waber, Citation2021) rather than relating this to the TEER discourse. Future approaches to synthesize reviews might find appropriate solutions of integrating those reviews that were, due to their heterogeneous approaches, not feasible for our synthesis. Even the 27 reviews included in our synthesis made up a heterogeneous data corpus for analysis. As a consequence, findings were disseminated on a more global level (for more details on the findings of the 27 reviews, see Appendix 2). Future approaches could go into depth, for example, by selecting a smaller number of reviews for their analysis or looking more closely to particular topics such as the content and quality of coursework as the most dominant category of processes (see Appendix 2). Also, since ITE and TPD may be shaped by cultural contexts (e.g. Townsend & Bates, Citation2007), future research could address the question how TEER might be shaped by different cultures in a globalized world, going beyond the perspective of the Western world which clearly dominated the present corpus of 27 reviews. However, with the present synthesis and suggestion of the PCC, we aimed at providing a global view, demonstrating the overall richness of TEER, that—highlighted as an emerging paradigm in educational research—may give rise for future directions, even in the area of reviews in the field of TEER.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (559.8 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2023.2268702

Additional information

Funding

References

- (titles included into the review marked by an asterix)

- *Avalos, B. (2011). Teacher professional development in teaching and teacher educati on over ten years. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(1), 10–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2010.08.007

- Baumert, J., Kunter, M., Blum, W., Brunner, M., Voss, T., Jordan, A., Klusmann, U., Krauss, S., Neubrand, M., & Tsai, Y.-M. (2010). Teachers’ mathematical knowledge, cognitive activation in the classroom, and student progress. American Educational Research Journal, 47(1), 133–180. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831209345157

- Berliner, D. C. (2004). Describing the behavior and documenting the accomplishments of expert teachers. Bulletin of Science, Technology and Society, 24(3), 200–212. https://doi.org/10.1177/0270467604265535

- Blömeke, S. (2017). Modelling teachers’ professional competence as a multi-dimensional construct. In S. Guerriero (Ed.), Pedagogical Knowledge and the Changing Nature of the Teaching Profession (pp. 119–135). Paris: OECD.

- Blömeke, S., Felbrich, A., Müller, C., Kaiser, G., & Lehmann, R. (2008). Effectiveness of teacher education: State of research, measurement issues and consequences for future studies. ZDM, 40(5), 719–734. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-008-0096-x

- Blömeke, S., Gustafsson, J.-E., & Shavelson, R. J. (2015). Beyond dichotomies: Competence viewed as a continuum. Zeitschrift für Psychologie, 223(1), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1027/2151-2604/a000194

- Blömeke, S., Jentsch, A., Ross, N., Kaiser, G., & König, J. (2022). Opening up the black box: Teacher competence, instructional quality, and students’ learning progression. Learning and Instruction, 79, 101600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2022.101600

- Blömeke, S., Suhl, U., & Kaiser, G. (2011). Teacher education effectiveness: Quality and equity of future primary teachers’ mathematics and mathematics pedagogical content knowledge. Journal of Teacher Education, 62(2), 154–171. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487110386798

- *Bottiani, J. H., Larson, K. E., Debnam, K. J., Bischoff, C. M., & Bradshaw, C. P. (2018). Promoting educators’ use of culturally responsive practices: A systematic review of inservice interventions. Journal of Teacher Education, 69(4), 367–385. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487117722553

- Brophy, J., & Good, T. L. (1986). Teacher behavior and student achievement. In M. C. Wittrock (Ed.), Handbook of research on teaching (3rd ed., pp. 328–375). Macmillan.

- Campbell, D. T., & Stanley, J. C. (1963). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for research. Ravenio Books.

- Carroll, J. B. (1963). A model of school learning. Teachers College Record, 64(8), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146816306400801

- *Cochran-Smith, M., & Villegas, A. M. (2015). Framing teacher preparation research: An overview of the field, part 1. Journal of Teacher Education, 66(1), 7–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487114549072

- Cochran-Smith, M., & Zeichner, K. M. (Eds.). (2005). Studying teacher education. The report of the AERA Panel on research and teacher education. Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Cramer, C., Brown, C., & Aldridge, D. (2023). Meta-reflexivity and teacher professionalism: Facilitating multiparadigmatic teacher education to achieve a future-Proof profession. Journal of Teacher Education, 002248712311622. https://doi.org/10.1177/00224871231162295

- *Cummings, R., Harlow, S., & Maddux, C. D. (2007). Moral reasoning of in‐service and pre‐service teachers: A review of the research. Journal of Moral Education, 36(1), 67–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240601185471

- Darling-Hammond, L. (2006). Assessing teacher education. The usefulness of multiple measures for assessing program outcomes. Journal of Teacher Education, 57(2), 120–138. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487105283796

- Darling-Hammond, L. (2020). Accountability in teacher education. Action in Teacher Education, 42(1), 60–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/01626620.2019.1704464

- Darling-Hammond, L., & Bransford, J. (Eds.). (2007). Preparing teachers for a changing world: What teachers should learn and be able to do. John Wiley & Sons.

- Darling-Hammond, L., Holtzman, D. J., Gatlin, S. J., & Heilig, J. V. (2005). Does teacher preparation matter? Evidence about teacher certification, teach for America, and teacher effectiveness. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 13, 1–48. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.v13n42.2005

- Day, C. (1999). Developing teachers: The challenges of lifelong learning. Falmer Press.

- Dixon-Woods, M., Agarwal, S., Jones, D., Young, B., & Sutton, A. (2005). Synthesising qualitative and quantitative evidence: A review of possible methods. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 10(1), 45–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/135581960501000110

- Doyle, W. (1977). 4: Paradigms for research on teacher effectiveness. Review of Research in Education, 5(1), 163–198. https://doi.org/10.3102/0091732X005001163

- Fernández-Batanero, J. M., Montenegro-Rueda, M., Fernández-Cerero, J., & García-Martínez, I. (2022). Digital competences for teacher professional development. Systematic review. European Journal of Teacher Education, 45(4), 513–531. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2020.1827389

- Flores, M. A. (2016). Teacher education curriculum. In J. Loughran & M. L. Hamilton (Eds.), International handbook of Teacher education (pp. 187–230). Springer.

- Florian, L., & Camedda, D. (2020). Enhancing teacher education for inclusion. European Journal of Teacher Education, 43(1), 4–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2020.1707579

- Gage, N. L., & Needels, M. (1989). Process-product research on teaching: A review of criticisms. The Elementary School Journal, 89(3), 253–300. https://doi.org/10.1086/461577

- Galluzzo, G. R., & Craig, J. R. (1990). Evaluation of preservice teacher education programs. In W. R. Houston (Ed.), Handbook of research on teacher education (pp. 599–616). Macmillan.

- *Gentry, L. B., Denton, C. A., & Kurz, T. (2008). Technologically-based mentoring provided to teachers: A synthesis of the literature. Journal of Technology & Teacher Education, 16(3), 339–373.

- Grossman, P. (2008). Responding to our critics: From crisis to opportunity in research on teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 59(1), 10–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487107310748

- Guerriero, S. (Ed.). (2017). Pedagogical knowledge and the changing nature of the teaching profession. OECD.

- Hascher, T., & Waber, J. (2021). Teacher well-being: A systematic review of the research literature from the year 2000–2019. Educational Research Review, 34, 100411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2021.100411

- Hattie, J. (2012). Visible learning for teachers: Maximizing impact on learning. Routledge.

- Hill, H., Mancenido, Z., & Loeb, S. (2021). Effectiveness research for teacher education. (EdWorkingPaper: 21-252). Annenberg Institute at Brown University.

- *Hogan, T., Rabinowitz, M., & Craven, J. A., III. (2003). Representation in teaching: Inferences from research of expert and novice teachers. Educational Psychologist, 38(4), 235–247. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326985EP3804_3

- Horsley, T. (2019). Tips for improving the writing and reporting quality of systematic, scoping, and narrative reviews. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 39(1), 54–57. https://doi.org/10.1097/CEH.0000000000000241

- *Juanjuan, G., & Mohd Yusoff, N. (2022). The shared features of effective improvement programmes for teachers’ assessment literacy. Pedagogies: An International Journal, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/1554480X.2022.2084398

- Kaiser, G., & König, J. (2019). Competence measurement in (mathematics) teacher education and beyond: Implications for policy. Higher Education Policy, 32(4), 597–615. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41307-019-00139-z

- *Kanellopoulou, E. M. D., & Darra, M. (2019). Benefits, difficulties and conditions of lesson study implementation in basic teacher education: A review. International Journal of Higher Education, 8(4), 18–35. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v8n4p18

- Karsenti, T. (2019). Artificial intelligence in education: The urgent need to prepare teachers for tomorrow’s schools. Formation et profession, 27(1), 105–111. https://doi.org/10.18162/fp.2019.a166

- *Kennedy, M. M. (2016). How does professional development improve teaching? Review of Educational Research, 86(4), 945–980. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654315626800

- *Knight, S. L., & Wiseman, D. L. (2005). Professional development for teachers of diverse students: A summary of the research. Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk (JESPAR), 10(4), 387–405. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327671espr1004_3

- König, J., & Blömeke, S. (2020). Wirksamkeits-Ansatz in der Lehrerinnen-und Lehrerbildung [Effectiveness approach in teacher education]. In C. Cramer, J. König, M. Rothland, & S. Blömeke (Eds.), Handbuch lehrerinnen- und lehrerbildung [handbook of Teacher education.] (pp. 172–178). Klinkhardt/UTB.

- König, J., Heine, S., Jäger-Biela, D., & Rothland, M. (2022). ICT integration in teachers’ lesson plans: A scoping review of empirical studies. European Journal of Teacher Education, 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2022.2138323

- *König, J., & Rothland, M. (2022). Lesson planning competence: Empirical approaches and findings. Zeitschrift Für Erziehungswissenschaft, 25(4), 771–813. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11618-022-01107-x

- König, J., Santagata, R., Schreiner, T., Adleff, A.-K., Yang, X., & Kaiser, G. (2022). Teacher noticing: A systematic literature review on conceptualizations, research designs, and findings on learning to notice. Educational Research Review, 36, 100453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2022.100453

- *Kraft, M. A., Blazar, D., & Hogan, D. (2018). The effect of teacher coaching on instruction and achievement: A meta-analysis of the causal evidence. Review of Educational Research, 88(4), 547–588. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654318759268

- *Kurniawati, F., De Boer, A. A., Minnaert, A. E. M. G., & Mangunsong, F. (2014). Characteristics of primary teacher training programmes on inclusion: A literature focus. Educational Research, 56(3), 310–326. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2014.934555

- *Kyriacou, C. (1993). Research on the development of expertise in classroom teaching during initial training and the first year of teaching. Educational Review, 45(1), 79–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/0013191930450107

- Kyriakides, L., Christoforou, C., & Charalambous, C. Y. (2013). What matters for student learning outcomes: A meta-analysis of studies exploring factors of effective teaching. Teaching and Teacher Education, 36, 143–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2013.07.010

- Lawson, T., Çakmak, M., Gündüz, M., & Busher, H. (2015). Research on teaching practicum–a systematic review. European Journal of Teacher Education, 38(3), 392–407. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2014.994060

- Lortie, D. C. (1975). Schoolteacher: A sociological study. University of Chicago Press.

- *Ma, K., Zhang, J., Chutiyami, M., Liang, L., & Dong, J. (2023). Effectiveness of blended teaching in preservice teacher education: A meta-analysis. Distance Education, 44(3), 495–521. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2022.2155617

- *Menekse, M. (2015). Computer science teacher professional development in the United States: A review of studies published between 2004 and 2014. Computer Science Education, 25(4), 325–350. https://doi.org/10.1080/08993408.2015.1111645

- *Mesutoglu, C., & Baran, E. (2021). Integration of engineering into K-12 education: A systematic review of teacher professional development programs. Research in Science & Technological Education, 39(3), 328–346. https://doi.org/10.1080/02635143.2020.1740669

- Muijs, D., & Reynolds, D. (2005). Effective teaching: Evidence and practice. Sage.

- Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), 143.https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

- OECD. (2018). Effective teacher policies: Insights from PISA. OECD Publishing.

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hrobjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S. … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. PLOS Medicine, 18(3), e1003583. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003583

- *Parkhouse, H., Lu, C. Y., & Massaro, V. R. (2019). Multicultural education professional development: A review of the literature. Review of Educational Research, 89(3), 416–458. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654319840359

- *Perry, T., Findon, M., & Cordingley, P. (2021). Remote and blended teacher education: A rapid review. Education Sciences, 11(8), 453. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11080453

- Rowan, L., Mayer, D., Kline, J., Kostogriz, A., & Walker-Gibbs, B. (2015). Investigating the effectiveness of teacher education for early career teachers in diverse settings: The longitudinal research we have to have. The Australian Educational Researcher, 42(3), 273–298. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-014-0163-y

- Scheerens, J. (2023). Theory on teaching effectiveness at meta, general and partial level. In Theorizing teaching: Current status and open issues (pp. 97–130). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- *Scheerens, J., & Blömeke, S. (2016). Integrating teacher education effectiveness research into educational effectiveness models. Educational Research Review, 18, 70–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2016.03.002