ABSTRACT

The purpose of this conceptual paper is to posit a possible reason why non-Indigenous educators are seen to be ‘cautious’ in their pedagogic engagement with First Nations perspectives in curriculum, why interventions and programmess around reconciliation and truth-telling have limited traction in affecting change in school culture, and why the Australian education system is constructed to be, and remains, largely hostile to First Nations Peoples and perspectives. Despite several decades of studies exploring these phenomena and concerted efforts to ‘fix the problem’, there has been a systemic failure to shift discourses and practice beyond the completely absent, tokenistic, or superficial inclusion of First Nations narratives in Australian education. We argue that power-knowledge relations of settler-colonial discourses are fundamentally at play and that by examining how disciplinarity and settler-colonial frameworks of knowledge control operate in education, we conceptualize a possible reason to the pedagogical challenges faced in the decision-making and integration of First Nations narratives in curriculum.

Introduction

The notion of epistemic inertiaFootnote1 as a reason for non-Indigenous educators’ being resistant and/or hesitant to integrating First Nations perspectives and content into curricula and learning has been present in educational research for several decades (Craven, Citation2012; Lampert, Citation2012; Sammel et al., Citation2020; Weuffen & Willis, Citation2023). It has been argued that this is due to feelings of being hamstrung by what is not known about First Nations perspectives. A degree of social amnesia and/or guilt permeates socio-cultural relations in Australia, and other settler-colonialist jurisdictions, which results in inclusive pedagogical practices leaning towards shallowness/tokenism or simply being absent altogether (Howard, Citation2016; Phillips, Citation2012). While this is a known and persistent problem, the failure of concerted efforts to ‘fix the problem’ and find ‘solutions’ that elicit sustainable change on a wider scale tells us something else is at play, something hidden in the shadows that we have not identified yet. In this conceptual paper, we argue that the notion of pedagogical narratives currently sits in those shadows, and by raising it, there is the potential to transform collective pedagogical practices of First Nations studies to all students across Australia.

In this paper, we conceptualize ‘pedagogical narratives’ as the collective storying of interlinked concepts conveyed about a particular topic across/within the whole or part of teaching profession for the purpose of facilitating group/year/cohort learning about key events/propositions. Even though educators make decisions about pedagogies that may be operationalized to achieve desired learning outcomes, they are shaped by cultural norms (Buehl & Beck, Citation2015; Howard, Citation2016) and political or social discourses (Hickling-Hudson & Ahlquist, Citation2003; O’Dowd, Citation2011) of the educational system. As normative practice, pedagogical narratives generally reflect curriculum syllabus and dictate the learning journeys of students across the Australian education system. We argue that they are—implicitly and explicitly—imbued with power-knowledge relations of settler-colonial discourses, which are fundamentally entwined with cultural relations of Australia and woven into multiple layers of educational practice—curriculum, pedagogy, and assessment. In this paper, we extend upon international scholarship (Bagelman, Citation2020; Leddy & O’Neil, Citation2022, Howard, Citation2016; Zemylas, Citation2021) to conceptualize that there is a need to shift scholarly understandings of non-Indigenous educators’ epistemic inertia when it comes to First Nations narratives to consider how decolonial, critical, and nourishing pedagogical practices may be sustained in Australian education. We do this by examining how disciplinarity and settler-colonial frameworks of knowledge control impact pedagogical decision making where First Nations narratives are concerned.

Controlling the educational narrative

The key function of education is to (re)enforce a particular citizenship within a society, one where there are shared ideologies, images and messages about the foundational moral virtues of a nation. It is a continuous and cyclical process of ‘conditioning [an individual’s] activities and experiences so that they are prepared to lead a meaningful adult life in society’ (Schiro, Citation2013, p. 69). In formal education, these messages become woven into the social consciousness and are communicated as norms through the pedagogical tools associated with curriculum, pedagogy and assessment. While appearing to be three separate aspects of education, they are inextricably tied to the disciplines (e.g. Sciences, Humanities, Languages, Arts, etc.) and legitimate power-knowledge relations around what content logically fits within particular curricula, how teaching ought to occur to ‘enculturate the official state version of reality’ (Mayes, Citation2020, p. 17), and the measures by which student success is determined. Over time, these relations (re)enforce foundational narratives within education in response to socio-political pressures and agendas. These narratives then come to underpin the ways in which citizens understand their positionality, the socio-political environment, and knowledge shared within society. We refer to this understanding as social consciousness (Schiltz et al., Citation2010), not as an inherent state of being that citizens either have or do not have about their existence, but rather the collective sense making about normative and accepted ways of being and knowing within a society.

As a socio-political tool of education, curriculum is mobilized to present an official and unquestioned narrative around topics of interest, aka disciplines (Rollo, Citation2022). These interest areas are ‘contaminated by representation’ (Green, Citation2018, p. 28) in that they are a carefully curated to tell a particular story. When examined critically, curriculum is the most powerful story that a nation-state tells ‘again and again as a form of mass communication’ (Green, Citation2018, p. 88). In this story, there is a centralizing lens through which the nation-state presents a descriptive story deemed important for its citizenship to know and value. As Schiro (Citation2013) highlights, curriculum conveys more than just knowledge; it communicates the ways of thinking, being and feeling associated with such knowledge all for the end goal of initiating and acculturating. But ‘knowledge is not neutral’ (Salinas et al., Citation2012, p. 19). Curriculum is used as the foundational instrument of obedience and conformity work enacted on individuals that ‘begins in school, continues at university and rules in all departments in which the nation-state has [authority]’ (Mayes, Citation2020, p. 115). Despite the reality that knowledge contained within the curriculum is ‘not stable or set in stone and can change at any given time’ (De Beer & Mothwa, Citation2016, p. 455), it is used as a self-referential technique by the nation-state to (re)present worldviews that are ontologically and epistemologically aligned with desired notions of ‘productive’ citizenship. Contained within the official document are accepted ways of operationalizing it, implicit hidden messages, particular ideas excluded, and extracurricular learnings associated that normalize what it means to live, and how one ought to function, within a particular society (Mayes, Citation2020; Zemylas, Citation2021).

The resultant and long-term consequence of a nation-state constructing and mandating curriculum becomes visible when examining practices of the profession. When educators are given responsibility for enacting curriculum, they are (as employees of the nation-state) inevitably complicit in perpetuating the desires of the nation-state, whether they are aware of this process or not (Weuffen et al., Citation2022). In this context, educators are not free or neutral agents (Dyches & Boyd, Citation2017). The social nature of teaching is communicatively and discursively constructed within the ‘broader social and cultural contexts with its changing institutional norms, practices, beliefs and discourses’ (Arvaja, Citation2016, p. 393). PedagogyFootnote2 as practices that educators use in their professional work and therefore inform their identity is used to convey knowledge in the curriculum and sets out the parameters for designing learning and determining impact on student comprehension. For many educators, and those who do not undertake critical professional development, this often occurs from a dualist perspective where knowledge is either true or false and comes from an authority source such as the curriculum, experts, or textbooks (Deng et al., Citation2014; Zemylas, Citation2021). The resultant outcome is that the nation making narratives conveyed in such official sources become so powerfully embedded in pedagogical discourses of infallible truth in ways that mirror the overarching curriculum trajectory and constitute the means by which settler-colonialism remains hidden at the same time.

The power of pedagogy is most visible in relation to knowledge, particularly in the ways that it is constructed as conceptually significant, generalizable and valid, or practically bounded by time, place and context (Laughran, Citation2019). Pedagogy, as an authority tool of the teaching profession is powerfully held in place by educational discourses and discipline-endorsed identities so that it underpins all learning and teaching practices, curriculum, and associated policies to constrain the capacity for conceptualizing, let alone speaking back to, institutionalized subject positionalities and the assumed normative ways of being, thinking, and doing (Arvaja, Citation2016; Morris & Imms, Citation2021; Weuffen et al., Citation2022). In this vein, the educational stories—whether explicit, written, or assumed—conveyed by the curriculum, professional standards, and/or policies influence the collective pedagogical consciousness. While it may appear that curriculum drives the nation-state narrative, it is the skills and knowledge assessed relating to descriptions that validates its truth.

The combined techniques of curriculum and pedagogy are underscored by assessment. Essentially, assessment criteria indicates what knowledge ‘counts’ ultimately in the curriculum and holds educators and students accountable to acquiring that knowledge. The combination of curriculum, pedagogy, and assessment leads to the ‘acculturing of students into society in such a way that they become good citizens’ (Schiro, Citation2013, p. 15) who embody the constructed worldviews of the nation-state. In Australia, students become good citizens when they learn under a neo-liberal paradigm that privileges westernized knowledge in the prescribed curriculum and rewards their academic performance against peers. The notion of ‘good citizenship’ is solidified in the ‘doing’ of education where pedagogical planning happens by a backward-by-design process from assessment standards to define and scaffold knowledge-making that aligns with the social norms of the nation. But, the end point always remains—to measure the degree of students’ understanding and conformity to the validity of knowledge presented (Schiro, Citation2013). Yet, educator positionality (their values, beliefs, backgrounds and experiences) influences decision-making, and therefore, the pedagogies employed to understand and present First Nations narratives and processes of sense-making and knowledge acquisition for students (Burgess et al., Citation2022; Lampert, Citation2012; Weuffen & Willis, Citation2023). The relationship of positionality and relational practices to combat epistemic inertia is current work being undertaken by the authors and will appear in forthcoming scholarship. In this paper, we build upon the significant theorizing work of others (Burgess et al., Citation2022; Hofer, Citation2016; Laughran, Citation2019; Lowe & Galstaun, Citation2020; Morris & Imms, Citation2021; Prete & Lange, Citation2021; Salinas et al., Citation2012; Thorpe, Citation2017), to conceptualize how decolonizing practices might be operationalized in Australian education right now by examining how notions of disciplinarity and settler-colonial frameworks influence decision making where First Nations narratives are concerned.

Foundations of pedagogical narratives

Focusing on curriculum as the sole driver of pedagogical practice ignores the socio-political influences of power-knowledge relations in neo-colonial nations (Lowe et al., Citation2022). Pedagogical narratives are much more complex than an isolated teaching practice where curriculum statements are translated. They are ontological assertions of the moral certainty and legitimacy of being within a nation-state. They contain the knowledges required to understand the cosmos of experiences, worldviews, histories, socialization, and conditioning that are developed and reinforced over time. Because of this, the practice of crafting pedagogical narratives is often a contradictory hidden and explicit practice of the education profession established within the disciplines. The atomization of First Nations content all over the curriculum in disconnected ways is one of the key reasons we and others argue that epistemic inertia or outright refusal to engage with such content in teaching practice emerges (Lowe & Galstaun, Citation2020; Lowe et al., Citation2022).

Our proposition about an absence of cohesive narratives that support the socio-political realities of First Nations People’s experiences of colonial exclusion in teaching and learning has been an ongoing conceptual project by members of the authorship team for the past decade. Genealogically, it started with an interrogation of curriculum structure to analyse how First Nations content is described culturally, cognitively, and socio-politically (Lowe & Yunkaporta, Citation2013), and ways in which educators are subjectively positioned in the Australian education system (Weuffen, Citation2019). This was followed by examination of the ways in which relationality and reciprocity between educators and local Aboriginal community members may disrupt typical settler-colonial power relations in the classroom (Bishop et al., Citation2019) in order to rethink how pedagogical narratives may be developed if examined from the perspective of student learning rather than curriculum practice (Lowe & Galstaun, Citation2020). More recently, the larger conceptual project has sought to uncover the complexities associated with non-Indigenous educators’ engagement with First Nations perspectives in curriculum (Weuffen, Citation2022), which has been argued to be predicated on a fundamental misunderstanding and/or misappropriation of the dynamics surrounding hospitality and exchange (Weuffen et al., Citation2023). The issues highlighted above, namely the purposeful exclusion of any counter storying to the ‘outcome’ of settler-colonialism, means that pedagogical narratives have been skewed from the beginning. This is further complicated by, the nominal time afforded for professional activities that critiques curriculum knowledge and interrogates the educational stories being conveyed to students. Yet, to do so would disrupt/challenge the settler-colonial narrative. As Dyches and Boyd (Citation2017) express, ‘at every step, instructional decisions [are made] that either work to promote a more equitable society, or under the guise of “neutrality”, [to] perpetuate hegemony’ (p. 479). While it is a normative pedagogical practice to build school-based curriculum around the end-of-year achievement standards, it is reinforced by the seemingly logical sequencing of curriculum statements guided by textbook studies (Weuffen & Willis, Citation2023). This is not an accidental process. It is situational design of western thought operationalized via power-knowledge relations of disciplinarity (Foucault, Citation2004) and rationale for why further conceptualization of factors impacting pedagogical decision-making where First Nations narratives are concerned is needed.

According to Foucault (Citation2004), disciplinary power is representational and relational. Representation to define truth and relational force to ensure conformity to that truth. Established in the latter years of the Age of Enlightenment (18th Century) and rapid expansion of Europeanism across the globe, settler-colonial nations prioritized the construction of cohesive citizenship by formalizing knowledge of phenomena via public university education. Knowledge was categorized and validated according to a discipline—a process where particular forms of knowledge was privileged over others and organized via pillars of normalization, selection, hierarchy and centralization (Foucault, Citation2004). Knowledge was assembled as having a logical and hierarchal sequence of scaffolded learning; essentially, a narrative was constructed about that body of knowledge. This disciplinary framework set the conditions for reinforcing and protecting the overall structure of western empirical knowledge which, over time, became synthesized into normative ways of thinking and acting within the bounds of specific disciplines. Such organisation and control around knowledge continues today; while curriculum content drives the story, disciplinarity assembles that story to validate it as truth (Salinas et al., Citation2012). It is these systematic and disciplinarity processes of knowledge production and acquisition that solidifies the pedagogical processes of creating and disseminating narratives in the field of education. These systemic structures uphold the settler-colonial agenda and continue to (re)colonize First Nations thoughts and minds (Dyches & Boyd, Citation2017).

Underpinning the operationalization of pedagogical narratives are an individual educators’ values (axiology), worldviews (ontology) and beliefs about knowledge (epistemology). They influence professional decision-making processes on a daily basis as they inform understandings according to a normative sense of relevance or irrelevance to individuals’ lifeworld’s and experiences (Buehl & Fives, Citation2016; Hofer, Citation2016; Maggioni & Parkinson, Citation2008). Such categorization is said to happen according to the broad categories of ‘the self, the immediate context, state and national contexts, and cultural norms and values’ (Deng et al., Citation2014, p. 246). Essentially, educators’ personal and professional positionality influences how they understand, interpret, place importance on, and devise learning and assessment tasks associated with the official curriculum. For many non-Indigenous Australian educators of European descent, they have been caught up in processes of indoctrination to settler-colonial ideologies which becomes (re)presented in their pedagogical narratives in ways that not only align with the legitimized story of European supremacy but also the primacy of western empirical thought as natural (Brookfield, Citation2014). For some non-white or migrant educators in Australia, a different form of attempted indoctrination occurs all towards the goal of irradicating their ‘native’ onto-epistemologies (Bagelman, Citation2020; Leonardo, Citation2002). For First Nations educators, such ideologies are an absurd divergence from their own lifeworlds and experiences, and thus, their pedagogical narratives often push back against the overarching stories presented in the settler-colonist curriculum (Burgess et al., Citation2022). This is because ‘personal epistemology is sensitive to cultural context’ (Deng et al., Citation2014, p. 245). Understanding how narratives are underpinned, informed, and created by positionality is critical to unpacking the pedagogical possibilities of creating a holistic story about First Nations Peoples, perspectives, sciences, cultures, and histories in an environment when the State mandated curriculum atomizes, sporadically interacts with, and decontextualizes First Nations presence throughout (Lowe & Yunkaporta, Citation2013).

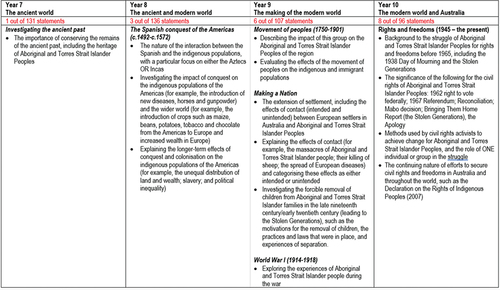

Similar to other settled-colonized-invaded countries, in Australia, curriculum, pedagogy, assessment, and teaching standards dictate that First Nations content and perspectives ought to be engaged with, but in reality, such policy does little more than pay lip-service. Settler-colonial onto-epistemologies always permeate (Bagelman, Citation2020; Zemylas, Citation2021). This is despite discourses of reconciliation touting that First Nations Peoples and perspectives should be respected and recognized as ‘the world’s oldest continuous living cultures’ (Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority [ACARA], Citation2021). In this manner, First Nations presence is acknowledged and tolerated so long as it does not disrupt the foundational narrative of settler-colonialism and advancement of western civilisation (Lowe et al., Citation2021; Salinas et al., Citation2012). For example, if we take the subject of Australian History (version 8.4 released October 2018), at the secondary level (Years 7–10), First Nations presence in level overviews, content descriptions, and achievement standards appears 18 out of 470 items. This is despite 60,000+ years of First Nations presence on the Australian continent and surrounding islands compared to the 240 years of European occupation. Of what does appear, there is a sense of initial neutrality or support for the importance of exploring ancient heritage in Year 7 before constructing First Nations Peoples’ achievements and resistance as relationally conditional to settler-colonialism in Year 9 and then promoting activism in Year 10 (see ). captures the content descriptors appearing across Years 7–10 curriculum that specifically reference First Nations Peoples using the nouns Aboriginal, Torres Strait Islander and Indigenous. They were retrieved from the Australian Curriculum website, navigating to the History curriculum via the Humanities and Social Sciences domain, selecting the targeted year levels, and manually reading through the descriptors (ACARA, Citation2021).

By themselves, these content descriptors lean towards the consumption of a historical nation-making story of passivity and victimhood of First Nations Peoples and communities. That is, up until the past seventy years where First Nations Peoples are constructed as struggling to gain human and civil rights. It is arguable that these content descriptors present an infallible pedagogical narrative that post-1788, the Australian nation making story cannot be understood without colonization and dominion over First Nations Peoples as its backdrop. Explorations of these curriculum statements are important because they illuminate quite clearly the difficult task faced by First Nations and non-Indigenous educators in their decision-and-sense-making of First NationhoodFootnote3 across the historical story of a settled and colonised Australia—a story that is conveyed for the ‘construction of collective memory in contemporary society’ (Salinas et al., Citation2012, p. 18).

An uncritical reading of the curriculum would suggest there IS First Nations presence. Albeit sporadic and seemingly underpinning all discipline areas as a cross-curriculum focus area, this belief holds true because of the epistemic cognitive conditioning that the State has mandated about general knowledge, disciplinary perspectives (truth and validity), and disciplinary knowledge (Hofer, Citation2016; Salinas et al., Citation2012). Rather than a holistic story, the curriculum presents disjointed narratives of First Nationhood that are often centred in deficit viewpoints and always in contrast to the veracity of settler-colonialism. As has been reported by a range of scholars (Brookfield, Citation2014; Lowe & Galstaun, Citation2020; Lowe & Yunkaporta, Citation2013), when such reductive practices are highlighted—often during in-service professional learning—overwhelmingly a sense of pedagogical blindsiding emerges because exposure to the new information about First Nationhood results in epistemic inertia or a hyper-attentiveness to needing to know everything before doing anything.

The power of settler-colonial narratives

Adherence to the settler-colonial narrative that western empirical thought and Eurocentrism is dominant and privileged plays out in professional practice via classroom pedagogies, disciplinary norms, and teaching standards. For instance, out of the 37 professional standards for educators only two reference specifically the need for understanding First Nations students and/or perspectives (Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership [AITSL], Citation2017). While many of the standards may also apply to First Nations students and contexts, the specification of these two culturally-focused standards invites assumptions and generalizations to be made. Additionally, while it has become a State mandate for ITE programs to ensure pre-service educators study at least one First Nations specific course across their entire degree (Lowe & Galstaun, Citation2020), similar professional learning is not afforded to in-service educators, unless they or their schools arrange it. This is where the problem of pedagogical narratives that reductively position or silence First Nations presence in Australian education is visible; there can be a perception that First Nations education has already been covered so further learning is unnecessary. Such ideology creates an environment for professional complicitness in the ‘programme of socially engineering students into objects of the state’ (Mayes, Citation2020, p. 180). This happens as pedagogical narratives of settler-coloniality are conveyed via schooling, whether educators personally associate with them, or are even cognizant of their influence on every function of professional practice. Professional teaching practices associated with curriculum, pedagogy, and assessment are often an unconscious rendering, but clear example, of how narratives constructed by the nation-state are interposed across all aspects of education. Where First Nations counter/narratives are presented, they contrast, and simultaneously reinforce, the power, truth, and validity of settler-colonialism and Western empirical evidence as the foundational knowledge-base of citizenship. Where counter/narratives are included in the curriculum they are arguably a benign nod to First Nations knowledges and perspectives that complement the broader story being presented (Lampert, Citation2012). For example, while First Nationhood is present in content descriptors, elaborations, and the cross-curriculum priority area, it is always in contrast to Imperialistic onto-epistemologies with investigations focused on questioning the civility and validity of First Nations knowledges. While appearing to be inclusive, such positioning is a strategic technique of assimilation ‘covered by the blanket of friendliness and sympathy’ (Rollo, Citation2022, p. 12). In order to have a colonizing and conquering narrative of European supremacy, the counter/narrative of passive First Nationhood needs to be presented in ways that legitimate the constructed power-knowledge relations. This was/is foundationally based on racist assumptions about a logic of elimination of prior occupation by First Nations Peoples by ‘including’ their perspectives within the framework but in ways that (re)enforce the unquestionable logic of European supremacy (Weuffen et al., Citation2022). At all levels, First Nations presence in the national curriculum is both troubling and complementary (Lowe & Galstaun, Citation2020).

For educators who have been raised and educated within neo-colonial systems, their onto-epistemological alignment to the prescribed mindset is almost a certainty unless deep critique is undertaken (De Beer & Mothwa, Citation2016). Because the system is self-referential, it is purposely difficult for institutionalized subjects within the profession to ‘see’ the overarching settler-colonial narrative of the curriculum. The curation of curriculum to enforce compliance is where power subtly and overtly puppeteers the teaching profession to (re)enforce socio-political narratives of Eurocentric nationhood and enculture the next generation of citizens (Salinas et al., Citation2012). The State uses education agendas and outcomes to constantly (re)orientate pedagogical practice towards the validity and certainty of settler-colonial power-knowledge relations and restrict the capacity of reconceptualizing a different way of engaging with First Nations knowledges and perspectives. In this manner, any content, pedagogies, and assessments that sit outside the enforced norms are not supported.

Mayes (Citation2020) argues that, as a collective, humans create stories for common and logical understandings of reality and cohesive social functioning, but as individuals, humans develop narratives within these stories that are reasoned to their internal biographical, cultural, and external schemas. Essentially, narratives are a means of making sense of phenomena and conveying socially acceptable ways of thinking, being, and doing. Language used to convey knowledge in curriculum is ‘embedded in cultural assumptions and historical processes and deterministic to how knowledge is apprehended’ (De Beer & Mothwa, Citation2013, p. 455). This process begins at birth and becomes more complex throughout the lifespan with exposure to ancestral histories, media outputs, and formal education, among other things (Brookfield, Citation2014). As a citizen in a settler-colonial controlled state, the stories that individuals encounter beyond their immediate family are constructed, driven, and sanctioned by the State and passed down as immutable nation-making truths or lore. While not a completely passive process, a citizen becomes the recipient of the constructed narrative until such a time as they develop a critical consciousness that begins to critique the stories they have been fed by the State. As Thorpe (Citation2017) posits, development of critical consciousness is more likely to emerge in communities of practice where learning within a collective and with a critical lens is prioritized.

While many parts of the world experienced the social, cultural, and economic impacts of European imperial desire and exploitation, in particular locations such as Australia, Aotearoa/New Zealand, Canada, and the Americas experienced the total subversion of their First Nations inhabitants through invasion and colonization. While such discourses are more visible in these countries, the twin evils of Eurocentric imperialism and settler-colonization has created a global ecology of neoliberal politics to which many countries across the world, in some way, attempt to conform to meeting standardized expectations and being competitive in the education sphere. Discourses of settler-coloniality are not about a past moment of conquest but an ongoing, structural desire for elimination (Wolfe, Citation2006). They are mobilized, within these countries, as a ‘weapon within the political field’ (Foucault, Citation2004, p. 189) to enforce juridical conformity to the narrative of Eurocentric nationhood. All knowledges, practices, and policies associated with schooling are designed to perpetuate this Eurocentric narrative. Curriculum, pedagogy, and assessment are interconnectedly used to communicate an unproblematised story about the making of the settled nation, that is underscored by onto-epistemological truths that are deeply embedded within ideologies of race and nationalism (Clark, Citation2006; Ditchburn, Citation2012, Hart et al., Citation2012; Parkes, Citation2007). As Green (Citation2018) describes, these tools are forms of representational epistemologies that are consistently validated by educational knowledge-making practices so that the right and logic of European thought and supremacy are unquestioned and unseen; they simply are.

While it is recommended that First Nations content be engaged with, in Australia, educators are not required to assess such knowledge or produce reports on such interactions. The non-assessed nature by which First Nations content is included in the curriculum reinforces the validity of western empirical thought that is so deeply woven throughout the disciplines. Lowe and Yunkaporta (Citation2013) highlighted that when the curriculum first came out, across the entire syllabus, there were only 142 matches to the word Aboriginal and that many of these items referenced ‘simple factual content rather than Aboriginal ways of thinking and doing’ (p. 4). Since then, with subsequent curriculum reviews and iterations, the response has been to ‘dump’ more First Nations content into specific discipline areas or remove specific disciplinary accounts in favour of cross-curriculum statements on the assumption that increasing the sheer volume will shift pedagogical practice. However, these strategies have not elicited sustainable change.

While ‘edge’ changes and positioning of First Nations studies as a cross-curriculum priority area appear to make them more visible in the curriculum, the creation and reinforcement of socio-political discourses around curriculum and disciplinary knowledge is a deliberate strategy designed to orientate the ‘national and historical setting … always representing [the] choices, purposes, [and] interests traditionally to elite interest and social roles’ (Yates et al., Citation2017, p. 17). It keeps conversations diverted from exploring, critiquing, and challenging the foundational ‘corrupt lay control or complex power structures inside and outside schools’ (Schiro, Citation2013, p. 34) aligned to the settler-colonialist statehood. This has directed a narrow focus on curriculum within academic scholarship towards retrofitting First Nations presence into an adversarial settler-colonial structure. In doing so, it has constrained exploration of the resultant impact of settler-colonial narratives within disciplinary structures on learning and teaching practices. This is exemplified by settler-colonists funding large-scale projects focused on adapting curriculum content and the development of supplementary teaching materials (Australians Together, Citation2023; CSIRO, Citationn.d.; Hogarth, Citation2022, The Living Knowledge Project, Citation2018; Langton & Barry, Citation2021). While such work is important for conducting educational reform in ways that are responsive to prioritizing and legitimating First Nations presence across the disciplines, it is unclear to what extent these projects assist non-Indigenous educators in feeling more enabled to approach First Nations topics. The underlying problem that these projects and resources do not tackle is the epistemic dissonance within the curriculum or the reality that westernized disciplinary thinking is always presented as normative. Essentially, this renders First Nations knowledges disembodied from onto-epistemological contexts and the critical localized relational connections to Country and communities from which such knowledge originates. Furthermore, such hyper-attentiveness to curriculum design and content has constrained the very possibility of developing cohesive pedagogical narratives that critically engages with First Nations content (Lowe & Galstaun, Citation2020).

The need for First Nations narratives

As we have conceptualized, the influence of disciplinarity and settler-colonial frameworks on pedagogical decision-making where First Nations narratives are concerned triggers a rethink about how schools and educators may create different education experiences for all students in ways that are a potential mechanism for enabling First Nations students’ self-determination. We propose that positioning of First Nations content and perspectives currently in the curriculum (i.e. disjointed, piecemeal) ought to shift to focus on conveying coherent and holistic First Nations narratives in such a way that it is treated as a discipline (or body of knowledge) unto itself—for example, as a mandatory ‘key learning area’ (KLA) in ‘Indigenous Studies’. As a thought experiment, imagine for a moment if any other discipline—say, Mathematics—were considered a ‘cross-curriculum priority’ rather than a comprehensive fundamental body of knowledge. Students would learn Mathematics via integration into other KLAs and be tasked with making conceptual connections to existing content. For example, imagine the absurdity and almost impossibility of assigning students the task of creating an architectural design before they had learned the fundamentals of arithmetic, measurement, and geometry. While the argument could be made that students had been exposed to Mathematics via this particular task, the question would remain as to whether they had been provided the required knowledges and skills to fully comprehend and complete the task to success. Obviously, such a line of thinking is patently ridiculous. It would call into question whether the education profession had done ‘an honest day’s work’ of ensuring the next generation of citizens were prepared for the world in which they live. Thus, equally so is the assumption that First Nations knowledges—which have a coherent axiological, ontological and epistemological foundation that exists in relational terms—cannot be understood in isolation, with elements splintered from each other and reconstituted in piecemeal fashion (Yunkaporta & Shillingsworth, Citation2020).

In postulating that First Nations studies might be better understood and taught as a subject curriculum with defined knowledges, skills, and assessments, we recognize that such a suggestion continues to position First Nations knowledges within the disciplinary structured and settler-colonial ideologically infused frameworks of schooling. There is the potential that such a move would only continue to (rein)force First Nations onto-epistemologies into the western order of things and thus ultimately in the service of settler-colonialism. However, given that the positioning of First Nations knowledges as a cross-curriculum priority area initially, and subsequently via increased specific referencing statements within the disciplines, has continued to result in epistemic disjuncture-where inconvenient truths reify Australian stories of triumph over the adversity of making the modern state-and have failed to shift pedagogical practices significantly, perhaps this is the next logical step in trialling how First Nations studies may be better learnt within the Australian education system. However, there is a paradox in this work, and in our examination of disciplinarity and the ideological influences on pedagogical practices relating to First Nations narratives in this paper, in that there is both a disruption and continuation of settler-colonial ontologies. Such alternative theorizing to the educational status quo is important as it forces an exposition about the interplay of power/knowledge relations, the continuing epistemicide of First Nations knowledges, and ways in which onto-epistemological sovereignty may be operationalized (Bagelman, Citation2020; Prete & Lange, Citation2021; Sammel et al., Citation2020; Zemylas, Citation2021). Yet, the foundation of any work by non-Indigenous educators attempting to comprehend coherent narratives of First Nationhood requires deep embodied learning about the limiting conditions of settler-colonial ideologies. The reality of the Australian school system is that it was never originally designed to sustain First Nations students’ connections to their communities and cultures, or align with First Nations onto-epistemologies. For that to happen, the system must fundamentally change.

In lieu of a systemic overhaul, or even the elevation of First Nations studies to its own subject area, we suggest that it’s plausible to envision short-term and achievable solutions for what is possible within the current system. While it is beyond the scope of this paper to explore in detail what changes and interventions may be beneficial for more comprehensive representations of First Nationhood, research postulates that a combination of whole-of-school approaches, high-level pedagogical thinking, and culturally responsive practices may provide insights into what is possible. Deeper understanding of socio-cultural dynamics surrounding schooling emerging from whole-of-school reform thinking (Amazan et al., Citation2023) has been shown to transform cognition of pedagogies towards generative knowledge construction via the notion of big ideas (Grant & Gradwell, Citation2009; Shulman & Sherin, Citation2007), and adoption of culturally responsive practices (Castagno & Brayboy, Citation2008). For example, Burgess et al. (Citation2022) and Lowe et al. (Citation2019), Lowe et al. (Citation2021). report how Community and Country-led professional learning is fruitful in assisting schools and educators in moving beyond epistemic inertia to make meaningful and situated understanding of curriculum, in particular, aspects dealing specifically with First Nations matters that are critical for improving schooling experiences for ALL students. There is tangible and unequivocable evidence highlighting the enhancement of pedagogical practices and conceptual understanding when relationships with local communities are prioritized towards listening to and learning from First Nations Peoples (Bishop et al., Citation2019; Thorpe et al., Citation2021). Essentially, there is a move towards pedagogical narratives of First Nationhood that are holistically responsive to local community knowledges and nourishing for all students’ understandings (LeGrange, Citation2020).

Currently, there are four significant projects happening in the Australian education landscape that are seeking to explore the sustained success-orientated changes that may occur as a result of developing more holistic First Nations pedagogical narratives. The Culturally Responsive PedagogiesFootnote4 project, led by Professor Lester-Irabinna Rigney (Citation2023), focuses on devising a framework that educators can use to redesign curriculum and pedagogy so that they are situated in unique socio-economic contexts. The Culturally Nourishing Schooling project (Lowe et al., Citation2022), led by Associate Professor Kevin Lowe, is a multi-dimensional study that employs direct and indirect strategies to empower community, school leaders, and educators to refashion education that prioritizes meaningful relationships, connections with Country, and localized First Nations knowledges, histories, and experiences. The Cultural Residents Project,Footnote5 led by Dr. Rose Amazan, which seeks to strengthen school-community relationships via the employment of a First Nations Cultural Educator to improve the teaching of local First Nations perspectives in schools. And the Indigenous curriculum content in the Australian curriculum project, also led by Associate Professor Kevin Lowe, which aims to investigate attitudes and approaches that may be barriers for educators engaging with First Nations studies. As these projects are still in-progress, publications using original empirical data are slowly becoming available; however, emerging evidence indicates identification of a range of factors that have a positive effect for moving beyond epistemic inertia and taking up professional practices around curriculum and pedagogy that prioritizes and holistically makes sense of First Nations knowledges, ways of thinking, and being (Gollege, Citation2022; Rigney, Citation2023). The problem remains however that schools and educators continue to work with the fractured narratives of First Nationhood presented in the current curriculum.

While this paper has sought to explore how disciplinarity and settler-colonial frameworks impact pedagogical decision-making where First Nations narratives are concerned, in future publications, this authorship team will present empiricial examples how such work has assisted educators in identifying structures to developing curriculum that tackles settler-colonialist overtures/undertones. The examination undertaken in this paper suggests that the first reality to be acknowledged as non-Indigenous educators wrestle with epistemic inertia is that the settler-colonial system consistently works self-referentially to uphold disciplinary power-knowledge relations. This is exemplified in the atomization of First Nations knowledge in curriculum which remains a key element to reinforcing pedagogical narratives embedded in the Australian story. Even when such glaring inequalities that have been identified time and again (Craven, Citation2012; Dyches & Boyd, Citation2017; Lowe & Galstaun, Citation2020), the State’s systems and policies are designed so they appear to be supporting inclusion but in reality continue to (re)create conditions of exclusion. As Carola (Citation2018) explains from a Latin American context, the enduring epistemological effects of Eurocentrism restrains possibilities of pedagogical thought about others and that only by drawing attention to this very fact is transformation possible. The second reality to address is that education is generally more focussed on neo-liberal achievement standards than equipping students with knowledge that empowers them with critical skills for operating in a global world (Brookfield, Citation2014; Burgess et al., Citation2022; De Beer & Mothwa, Citation2016). Rather than focusing on the minutia of pedagogical practice and the epistemic inertia that emerges from a sense of ignorance or fear of First Nations content, and persisting with increasing the amount of First Nations specific references in the curriculum, ready-to-use resources, or professional development offerings, we suggest that a rethinking of how pedagogies may convey a coherent and holistic First Nations presence, cultures and space in Australia would be a fruitful endeavour.

In light of these arguments, we provocate that a critical element to tackling epistemic inertia and the shadowy space of endless funding to ‘fix the problem’ and finding ‘solutions’ that don’t result in systemic or sustained change is Community and Country-led professional learning. This is becuase such learning replicates that which would/should have been received in formal education if First Nations presence was authentically prioritized. This would provide avenues for taking action against forced complicitness to the disciplinary foundations of settler-colonialism upon which pedagogical practice occurs in Australia. This work is critical because the very foundation of settler-colonialist frameworks rests on the adherence of its citizens to work within the normalized practices of the system in order to maintain the status quo despite educational declarations to the contrary (Lowe et al., Citation2021; Rollo, Citation2022; Weuffen et al., Citation2022). In this context, there is a desperate need for coherent and holistic First Nations narratives to presented within the curriculum and pedagogical practice as a means of moving beyond the smallness of what’s possible within education. Otherwise, continued complicitness to current practices will always default to a notion of cultural competence within a biased settler-colonial system.

Conclusion

The arguments presented in this paper propose the need for developing contextualized, coherent, and holistic First Nations pedagogical narratives in settler-colonial education systems where compliance to the nation-making story is settled, and continuously self-referenced in curriculum and policies. We do not assert that the development of coherent and holistic First Nations pedagogical narratives is the singular answer to epistemic inertia or lack of sustainable change in the Australian education system. Rather, it is one aspect that may be operationalized to challenge the perpetuating (re)colonizing techniques of the State. While this paper conceptualizes how disciplinarity and settler-colonial frameworks of knowledge control impact educators’ pedagogical decision making where First Nations narratives are concerned, further conceptual and empirical research is needed to unpack how these manifest within particular disciplines and for different cohorts. The prospect of understanding, let alone disseminating, coherent narratives about First Nationhood, before, and since, contact is an impossibility unless deep work pushes and challenges the foundations of settler-colonialism. As long as fractured and incomplete pedagogical narratives of First Nationhood continue to be operationalized in Australian schooling, the rhetoric of inclusion, rather than systemic change, will hold strong. To combat this, we believe a holistic reconceptualision is necessary based on (1) the notion of disciplinarity and the ways in which knowledge is constructed and validated, and (2) a coherent pedagogical narrative that ‘sees’ First Nations stories as a whole not as fragmented events that prop up the settler-colonial narrative. We argue that to create opportunities for more coherent and expansive pedagogical narratives about First Nationhood, there needs to be, in the long-term, major systemic changes, and in the short-term, targeted interventions that assist pedagogical shifts to occur in ways that more deeply and holistically situates knowledge about First Nationhood in their axio-onto-epistemological foundations.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Cognitive inaction to interact with content and move beyond a fear of getting it wrong, offending, or being labelled racist (Weuffen & Willis, Citation2023; Weuffen et al., Citation2023)

2. The science of teaching that combines theory and practice relating to a specific discipline.

3. The ways of being, knowing, and doing associated with First Nations communities.

References

- Amazan, R., Wood, J., Lowe, K., & Vass, G. (2023). Pathways to progress? - collective conscientisation and progressive school reform in aboriginal education. Critical Studies in Education, Published online 06 Nov. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2023.2275771

- Arvaja, M. (2016). Building teacher identity through the process of positioning. Teaching and Teacher Education, 59(1), 392–402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2016.07.024

- Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority [ACARA]. (2021). About the Australian Curriculum. https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/about-the-australian-curriculum/

- Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership [AITSL]. (2017). Australian professional standards for teachers. https://www.aitsl.edu.au/standards

- Australians Together. (2023). Curriculum Resources. https://australianstogether.org.au/curriculum-resources/

- Bagelman, C. (2020). ‘Dreaming new visions’: Indigenous thinkers on decolonising education. Educational Futures, 11(2), 41–62. https://educationstudies.org.uk/?p=12893

- Bishop, M., Vass, G., & Thompson, K. (2019). Decolonising schooling practices through relationality and reciprocity: Embedding local Aboriginal perspectives in the classroom. Pedagogy Culture & Society, 29(2), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2019.1704844

- Brookfield, S. (2014). Teaching our own racism: Incorporating personal narratives of whiteness into anti-racist practice. Adult Learning, 25(3), 89–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/1045159514534189

- Buehl, M. M., & Beck, J. S. (2015). The relationship between teachers’ beliefs and teachers’ practice. In H. Fives & M. G. Gill (Eds.), International handbook of research on teachers’ beliefs (pp. 66–84). Routledge.

- Buehl, M. M., & Fives, H. (2016). The role of epistemic cognition in teacher learning and praxis. In J. A. Green & S. I. Braten (Eds.), Handbook of epistemic cognition (pp. 247–264). Routledge.

- Burgess, C., Thorpe, K., Egan, S., & Halwood, V. (2022). Learning from country to conceptualise what an Aboriginal curriculum narrative might look like in education. Curriculum Perspectives, 42(1), 157–169. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41297-022-00164-w

- Carola, C. R. (2018). Precursors of decolonial pedagogical thinking in Latin Ameria and Abya Yala. In O. Bernad Cavero & N. Lievot-Calvet (Eds.), New pedagogical challenges in the 21st Century: Contributions of research in education (pp. 97–140). IntechOpen.

- Castagno, A. E., & Brayboy, B. M. J. (2008). Culturally responsive schooling for indigenous youth: A review of the literature. Review of Educational Research, 78(4), 941–993. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654308323036

- Clark, A. (2006). Teaching the nation: Politics and pedagogy in Australian history. Carlton, VIC: Melbourne University Publishing.

- Craven, R. (2012). Seeding success: Getting started teaching Aboriginal studies effectively. In Q. Beresford, G. Partington, & G. Gower (Eds.), Reform and resistance in aboriginal education: The Australian experience (pp. 335–378). UWA Publishing.

- CSIRO. (n.d.). About the Project. https://www.csiro.au/en/education/Programs/Indigenous-STEM-Education-Project/About-the-Project

- De Beer, J., & Mothwa, M. (2016). Indigenous knowledge in the Science classroom: Science, pseudoscience, or a missing link? Proceedings: Towards Effective Teaching and Meaningful Learning in Mathematics, Science and Technology. ISTE International Conference on Mathematics, Science and Technology Education. 21-24 October. https://uir.unisa.ac.za/handle/10500/22514

- Deng, F., Chai, C. S., Tsai, C.-C., & Lee, M.-H. (2014). The relationships among Chinese practicing teachers’ epistemic beliefs, pedagogical beliefs and their beliefs about the use of ICT. International Forum of Educational Technology & Society, 17(2), 245–256. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/jeductechsoci.17.2.245

- Ditchburn, G. (2012). A national Australian curriculum: In whose interests? Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 32(3), 259–269. https://doi.org/10.1080/02188791.2012.711243

- Dyches, J., & Boyd, A. (2017). Foregrounding equity in teacher education: Toward a model of social justice pedagogical and content knowledge. Journal of Teacher Education, 68(5), 476–490. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487117705097

- Foucault, M. (2004). Society must be defended: Lectures at the college de France, 1975-76. Penguin Books.

- Gollege, C. (2022, November 30). What Makes a Culturally Nourishing School? [blog]. EduResearch Matters: A voice for Australian educational researchers. https://www.aare.edu.au/blog/?p=15275

- Grant, S. G., & Gradwell, J. (2009). The road to ambitious teaching: Creating big ideas units in history classess. Journal of Inquiry & Action in Education, 2(1). https://digitalcommons.buffalostate.edu/jiae/vol2/iss1/1

- Green, B. (2018). Engaging curriculum: Bridging the curriculum theory and English education divide. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/97813156509444

- Hart, V., Whatman, S., McLaughlin, J., & Sharma-Brymer, V. (2012). Pre-service teachers' pedagogical relationships and experiences of embedding Indigenous Australian knowledge in teaching practicum. Compare, 42(5), 703–723. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2012.706480

- Hickling-Hudson, A., & Ahlquist, R. (2003). Whose culture? The colonising school and the miseducation of Indigenous children: Implications for schooling in Australia. Journal of Postcolonial Education, 2(2), 11–31.

- Hofer, B. (2016). Epistemic cognition as a psychological construct. In J. A. Green, W. A. Sandoval, & I. Braten (Eds.), Handbook of epistemic cognition (pp. 19–38). Routledge. https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9781315795225.ch2

- Hogarth, M. (2022). Ngarrngga. Our knowing: A collaborative partnership. https://about.unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0026/372086/UoM-Fact-Sheet_Ngarrngga_FINAL99.pdf

- Howard, G. R. (2016). We can’t teach what we don’t know: White teachers, multiracial schools. Teachers College Press.

- Lampert, J. (2012). Becoming a socially just teacher: Walking the talk. In J. Phillips & J. Lampert (Eds.), Introductory indigenous studies in education: Reflection and the importance of knowing (pp. 81–96). Pearson Education Australia.

- Langton, M., & Barry, R. (2021). Indigenous Knowledge Resources for Australian School Curricula Project. https://indigenousknowledge.unimelb.edu.au/curriculum#home

- Laughran, J. (2019). Pedagogical reasoning: The foundation of the professional knowledge of teaching. Teachers & Teaching, 25(5), 523–535. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2019.1633294

- Leddy, S., & O’Neil, S. (2022). Learning to see: Generating decolonial literacy through contemporary identity-based Indigenous art. International Journal of Education & the Arts, 23(9). https://doi.org/10.26209/ijea23n9

- LeGrange, L. (2020). The (post)human condition and decoloniality: Rethinking and doing curriculum. Alternation, 31(1), 119–142. https://doi.org/10.29086/2519-5476/2020/sp31a7

- Leonardo, Z. (2002). The souls of white folk: Critical pedagogy, whiteness studies, and globalization discourse. Race Ethnicity and Education, 5(1), 29–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613320120117180

- The living knowledge project. (2018). Living Knowledge: Indigenous Knowledge in Science Education. https://livingknowledge.anu.edu.au/index.htm

- Lowe, K., Burgess, C., Vass, G., Woods, A., Martin, A., Amazan, R., & Durksen, T. (2022). 27: Culturally nourishing schooling (CNS) for Indigenous education [research brief]. https://www.unsw.edu.au/content/dam/pdfs/unsw-adobe-websites/arts-design-architecture/education/research/project-briefs/2022-07-27-ada-culturally-nourishing-schooling-cns-for-Indigenous-education.pdf

- Lowe, K., & Galstaun, V. (2020). Ethical challenges: The possibility of authentic teaching encounters with indigenous cross-curriculum content? Curriculum Perspectives, 40(1), 93–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41297-019-00093-1

- Lowe, K., Harrison, N., Tennent, C., Guenther, J., Vass, G., & Moodie, N. (2019). Factors affecting the development of school and indigenous community engagement: A systematic review. The Australian Educational Researcher, 46(1), 253–271. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-019-00314-6

- Lowe, K., Moodie, N., & Weuffen, S. (2021). Refusing reconciliation in Indigenous curriculum. In B. Green, P. Roberts, & M. Brennan (Eds.), Curriculum challenges and opportunities in a changing world: Transnational perspectives in curriculum inquiry. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-61667-0_5

- Lowe, K., & Yunkaporta, T. (2013). The inclusion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander content in the Australian national curriculum: A cultural, cognitive and socio-political evaluation. Curriculum Perspectives, 33(1), 1–14.

- Maggioni, L., & Parkinson, M. M. (2008). The role of teacher epistemic cognition, epistemic beliefs, and calibration in instruction. Educational Psychology Review, 20(4), 445–446. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-008-9081-8

- Mayes, C. (2020). Archetype, culture, and the individual in education: The three pedagogical narratives. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429423758

- Morris, J. E., & Imms, W. (2021). ‘A validation of my pedagogy’: How subject discipline practice supports early career teachers’ identities and perceptions of retention. Teacher Development, 25(4), 465–477. https://doi.org/10.1080/13664530.2021.1930126

- O’Dowd, M. (2011). Australian identity, history and belonging: The influence of white Australian identity on racism and the non-acceptance of the history of colonisation of indigenous Australians. International Journal of Diversity in Organizations, Communities & Nations, 10(6), 29. https://doi.org/10.18848/1447-9532/CGP/v10i06/38941

- Parkes, R. J. (2007). Reading history curriculum as postcolonial text: Towards a curricular response to the history wars in Australian and beyond. Curriculum Inquiry, 37(4), 383–397. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-873X.2007.00392.x

- Phillips, J. (2012). Indigenous knowledge perspectives: Making space in the Australian centre. In J. Phillips & J. Lampert (Eds.), Introductory indigenous studies in education: Reflection and the importance of knowing (pp. 9–25). Pearson Education Australia. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/unsw/detail.action?docID=5729102

- Prete, T., & Lange, E. (2021). Indigenous voices and decolonising lifelong education. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 40(4), 303–309. https://doi.org/10.1080/02601370.2021.1968240

- Rigney, L. (2023). Global perspectives and new challenges in culturally responsive pedagogies: Super-diversity and teaching practice. Routledge.

- Rollo, T. (2022). Beyond curricula: Colonial pedagogies in public schooling. In S. D. Styres & A. Kempf (Eds.), Troubling truth and reconciliation in Canadian education: Critical perspectives (pp. 121–138). University of Alberta.

- Salinas, C., Blevins, B., & Sullivan, C. C. (2012). Critical historical thinking: When official narratives collide with other narratives. Multicultural Perspectives, 14(1), 18–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/15210960.2012.646640

- Sammel, A., Whatman, S., & Blue, L. (2020). Indigenizing education: Discussions and case studies from Australia and Canada. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-4835-2

- Schiltz, M. M., Vieten, C., & Miller, E. M. (2010). Worldview transformation and the development of social consciousness. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 17(7–8), 18–36.

- Schiro, M. S. (2013). Curriculum theory: Conflicting visions and enduring concerns. SAGE Publications.

- Shulman, L. S., & Sherin, M. G. (2007). Fostering communities of teachers as learners: Disciplinary perspectives. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 36(2), 135–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/0022027032000135049

- Thorpe, K. R. (2017). Narratives of learning at the cultural interface: The influence of Indigenous studies on becoming a teacher. [ Doctoral Thesis]. http://hdl.handle.net/2123/17641

- Thorpe, K., Burgess, C., & Egan, S. (2021). Aboriginal community-led preservice teacher education: Learning from country in the city. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 46(1), 55–73. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.202v46n1.4

- Weuffen, S. (2019). Surveying the landscape five years on: An examination of how teachers, and the teaching of Australia’s shared-history, is constructed within Australian academic literature. Teaching and Teacher Education, 78(1), 117–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2018.11.010

- Weuffen, S. (2022). ‘You’d be surprised how some people probably feel uncomfortable’: The compliance-resistance continuum of planning integrated Australian history curricula. Teacher Development, 26(2), 221–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/13664530.2022.2027266

- Weuffen, S., Lowe, K., Burgess, C., & Thompson, K. (2023). Sovereign and pseudo-hosts: The politics of hospitality for negotiating culturally nourishing schools. The Australian Educational Researcher, 50(1), 131–146. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-022-00599-0

- Weuffen, S., Maxwell, J., & Lowe, K. (2022). Inclusive, colour-blind, and deficit: Understanding teachers’ contradictory views of Aboriginal students’ participation in education. Australian Educational Researcher, 50(1), 89–110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-022-00517-4

- Weuffen, S., & Willis, K. (2023). The fallacy of cultural inclusion in mainstream education discourses. In Weuffen, S., Burke, J., Plunkett, M., Goriss-Hunter, & Emmett, S. (Eds.), Inclusion, equity, diversity, and Social Justice in education: A critical exploration of the sustainable development goals (pp. 91–107). Springer.

- Wolfe, P. (2006). Settler colonialism and the elimination of the native. Journal of Genocide Research, 8(4), 387–409. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623520601056240

- Yates, L., Woelert, P., Millar, V., & O’Connor, K. (2017). Knowledge at the crossroads?: Physics and history in the changing world of schools and universities. Springer.

- Yunkaporta, T., & Shillingsworth, D. (2020). Relationally responsive standpoint. Journal of Indigenous Research, 8(1), 1–14. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/kicjir/vol8/iss2020/4

- Zemylas, M. (2021). Sylvia Wynter, racialized affects, and minor feelings: Unsettling the coloniality of the affects in curriculum and pedagogy. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 54(1), 336–350. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2021.1946718