ABSTRACT

Teacher education quality and effectiveness have been at the centre of policy discussions in the last decades. As part of efforts to improve teacher preparation, law 20.903 requires Chilean universities to design and apply diagnostic tests assessing the construct of their choice to all first-year preservice teachers. Based on these results, universities must design strategies to support their students. However, universities are facing challenges in implementing these tests, primarily due to the complexity, time and cost associated with developing high-quality tests. In collaboration with three universities, we developed three diagnostic tests: Social Thinking Test, Attitudes Towards Diversity Questionnaire, and Mathematics test for Teaching in Primary Education. Unlike many of the tests currently used by universities, these instruments were specifically designed to measure core teaching skills and attitudes defined by the national standards for Chilean teachers. To collect validity and reliability evidence, the tests were piloted with over 850 Chilean preservice teachers. Reliability was analysed using Cronbach’s alpha, with results ranging between 0.67 and 0.92. Validity was examined based on content and internal structure evidence. The analysis of content evidence indicated good coverage of the target domains as defined by the assessment frameworks, and internal structure results point towards the presence of multidimensionality in two of the three tests. This paper discusses the results of these pilot studies and how diagnostic tests that are constructed and analysed from the perspective of the standards (American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association y National Council on Measurement in Education, 2014) can provide valuable information to improve the effectiveness of teaching education.

Introduction

With the return to democracy after 17 years of military dictatorship in Chile, the 1990s marked the beginning of an extensive educational reform comprising various initiatives aimed at enhancing the quality and equity within the Chilean educational system (García-Huidobro & Cox, Citation1999). Alongside a substantial investment in infrastructure and the modernization of the existing national school curriculum, the educational reform placed significant emphasis on strengthening the teaching profession, initially focusing on the incumbent teaching staff (e.g. Jiménez & Taut, Citation2015; Ministerio de Educación, Citation2004).

Furthermore, during the early 1990s, the number of students pursuing education degrees decreased by nearly half when compared to the early 1980s. The quality of the training provided suffered a significant decline and the devaluation of the teaching profession, marked by factors like a sharp drop in teacher salaries, dampened the enthusiasm of young individuals considering pedagogical studies (Ávalos, Citation2003). Additionally, a host of challenges, including the lower academic calibre of pedagogy programme entrants, outdated and disjointed teacher training programmes, unfavourable student perceptions of their educational experiences, institutional concerns, inadequate preparedness of teacher trainers, resource and infrastructure deficiencies, and a lack of coordination among academic departments responsible for teacher training, further compounded the difficulties in enhancing teacher education (Ávalos, Citation2002). As an emblematic starting point to address this issue, a national programme for enhancing teacher training was launched in 1997. This five-year initiative involved collaborative efforts from selected programmes across 17 universities in Chile, aimed at elevating the quality of their teacher training programmes. Spanning a broad geographic reach, this programme served approximately 80% of students enrolled in pedagogy degree programmes (Ávalos, Citation2003).

Afterwards, several programmes have been launched over the past 20 years to strengthen public policy in the teacher profession and initial teacher training (Jiménez & Taut, Citation2015), including the development of standards for initial teacher training (first introduced in 2011 and with a revised version launched in 2022) and the introduction of higher accreditation requirements for institutions offering these programmes. These efforts aimed to address the quality problems that persisted during the nineties due to the lack of regulation within tertiary education, while also expecting accountability from the training institutions. As a crucial milestone in addressing that issue, Law 20.903 was promulgated in 2016, concerning the establishment of a teacher professional development system. This legal framework mandates that education students must undergo two diagnostic assessments: the first, administered by each programme or university at the beginning of their studies, and a national standardized test, centrally defined and conducted by the Center for Improvement, Experimentation, and Pedagogical Research within the final 12 months prior to graduation.

The former is the focus of this paper, and it forces all Chilean universities to meticulously craft and administer diagnostic assessments tailored to their preferences for every first-year preservice teacher. Subsequently, based on the outcomes of these assessments, universities are tasked with crafting strategies to level and provide support for their students.

If Chilean universities do not implement the diagnostic assessments, they would be in violation of one of the regulations established since 2019 in the mandatory accreditation of teacher training programmes, potentially leading to programme closure.

As an important contextual element, it is worth noting that Chile has a diverse higher education system, with both public and private universities offering teacher education programmes. These programmes encompass a wide range of subjects and educational levels, including primary and secondary education, special education, and early childhood education. There are 58 universities within the higher education system, 18 public and 40 private, and as of 2023, nearly 32,973 students were enrolled in teacher education programmes (Higher Education Information Service, Citation2023).

Chilean universities have considerable flexibility in implementing diagnostic assessments. They can decide the type of tests to apply (for example, whether the tests are specifically related to teacher preparation or not), when to administer them (with specific dates and times determined by each university), and how to conduct them (including options for paper-based or online assessments). In essence, Law 20.903 respects the autonomy of each university, allowing them to develop diagnostic tests based on their individual interests, needs, and resources.

Probably due to the internal nature of these evaluations, there is very little existing literature regarding the attributes being assessed and the instruments used for assessment. However, studies have shown that universities are encountering challenges in implementing these assessments, primarily due to the complexity, time, and cost associated with developing high-quality tests (Giaconi et al., Citation2019, Citation2022). Consequently, many universities have not clearly defined the purposes of these tests, other than mere compliance with the law, and have not focused on fundamental knowledge and skills required for pedagogy (Giaconi et al., Citation2019).

Furthermore, since 2015 in Chile, teacher education programmes can only be offered by universities, which means that the vast majority of students must take the standardized national tests used for admission to higher education. However, approximately four months later, when the formal teacher education programme begins, diagnostic tests are administered to first-year students to meet the regulatory requirements mandated by the law mentioned below. Often, these tests assess general skills such as reading comprehension or logical reasoning and end up being merely an extension of those applied to all students entering the university that year (Giaconi et al., Citation2019). These challenges undoubtedly compromise the quality of the diagnostic tests being implemented and the potential impact of this Chilean policy on teacher preparation. Clarity regarding the evaluative purpose is essential for guiding the development or selection of assessment instruments and ensuring valid inferences and interpretations can be drawn from them (AERA, APA & NCME, Citation2014).

In terms of the specificity of the instruments, it is well-established that both the training and evaluation of future teachers should focus on knowledge and skills specific to the teaching profession (Darling-Hammond et al., Citation2009; Mourshed et al., Citation2010; Musset, Citation2010). This approach aligns with the advancements made in recent years regarding the understanding of these competencies and their implications for initial teacher education (Guerriero, Citation2017; Schleicher, Citation2016; Townsend & Bates, Citation2007). Teaching competence is currently conceptualized as a multidimensional construct, encompassing various knowledge, skills, and beliefs that manifest during teaching practice (Yang et al., Citation2018). This comprehensive perspective can be further elucidated by recognizing it as an outcome derived from effective teacher education (Kaiser & König, Citation2019). In addition to the traditional knowledge, beliefs, and motivations recognized in the teaching profession (e.g. Ball et al., Citation2008; Freeman et al., Citation2015; Richardson, Citation1996; Shulman, Citation1986; Thompson, Citation1992; Weinert, Citation2001), more context-specific skills have been incorporated. These include a teacher’s ability to perceive, interpret, and manage complex classroom situations, ultimately influencing their observable performance (Blömeke & Kaiser, Citation2017; Blömeke et al., Citation2015).Footnote1

Given its complexity and multidimensionality, assessing teaching competence requires a range of assessments. Until recently, Chile lacked comprehensive evaluation efforts in this regard, with initiatives primarily focusing on developing instruments to measure partial aspects of teaching competence.

In this context, the FONDEF project ‘Initial Diagnostic Evaluation in Pedagogy: Collaborative Construction of Instruments for Enhanced Teacher Training’ was conducted for nearly three years. It stood out as a holistic endeavour involving four universities collaborating to contribute to the improvement of the diagnostics tests. The project involved (1) the development of a battery of instruments addressing facets relevant to teacher training, in line with the Standards of Teacher Training, (2) adherence to rigorous technical standards, including the collection of validity evidence, and (3) the design of results reports that, in addition to providing scores, included sample items and descriptions of performance levels to better support the formative use of data.

Collaboration played a pivotal role, with the aim of resource optimization. Each participating institution could bring forth their prior knowledge and expertise in developing assessment instruments related to these constructs. Furthermore, it enabled the integration of a larger and more diverse sample, streamlining efforts for validation and pilot studies. This approach facilitated robust psychometric analyses, which may not have been attainable with smaller sample sizes.

This paper seeks to elucidate the creation of three assessment instruments meticulously designed for Chilean primary teaching education students. These instruments are fortified by substantial evidence of their validity and reliability, firmly anchored in empirical research, and are intended for diagnostic applications. Validity is the most fundamental consideration in developing tests and refers to the degree to which evidence and theory support the interpretations of test scores for proposed uses of tests (American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association y National Council on Measurement in Education, Citation2014, p. 11). Reliability refers to the consistency of scores across replications of a testing procedure (American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association y National Council on Measurement in Education, Citation2014).

Background

While the diagnostic tests conducted within the first month of teacher training are independently determined and implemented by each university, this approach offers the advantage of institutional autonomy in selecting the constructs to be assessed, choosing assessment formats and methodologies, and determining the utility of results in students’ formative progress. However, this decentralized system has its drawbacks. It lacks specific additional funding and technical support for test development, resulting in many cases in assessments that fall short of providing high-quality and relevant solutions to the challenge at hand. Furthermore, this dispersion of efforts hampers the ability to maintain essential quality control. The limited number of students undergoing these assessments does not suffice to ascertain the psychometric characteristics necessary to evaluate test quality. Consequently, this situation has led many universities to administer tests primarily to meet regulatory requirements, often neglecting the intended formative purpose as mandated by the law.

As mentioned before many universities had already been conducting initial diagnostic assessments for all their programmes and extended these assessments to pedagogy programmes solely for compliance purposes. Consequently, these assessments are of a general nature and do not address specific knowledge or skills of the teaching profession. Within this context, diagnostic assessments often resemble the college admission tests that the same students took a few months earlier, providing limited additional relevant information at that time.

Moreover, most of these tests are primarily designed to identify areas requiring academic enhancement for levelling, with the main focus being on helping students overcome challenges in aspects necessary for successful engagement in the educational process, such as improving retention and graduation rates. However, the full potential of diagnostic tests for formative purposes in initial teacher training remains largely untapped. These assessments can be harnessed to measure the knowledge and skills that will be pertinent to a future teacher’s professional practice, enabling ongoing monitoring throughout the programme and thereby ensuring the achievement of the graduate profile and enhancing overall professional performance.

Why are these constructs relevant in primary teaching training?

In the case of students entering Primary Education teaching programmes, all the addressed issues are exacerbated and have greater consequences. On one hand, this is one of the most massive teaching programmes nationwide, with 7,442 students in training and 1,867 students entering each year (Consejo Nacional de Educación, Citation2023).

Mathematics for teaching and Beliefs

Since Primary Education teachers need to be prepared to teach all subjects in that curriculum, it becomes challenging to diagnose them in all of these subjects. While there is broad consensus on the inclusion of mathematics tests, it is difficult to justify the utility of evaluating the contents of Secondary Education (already assessed by the compulsory Mathematics university admission test) as currently done, instead of focusing on the mathematical content of Primary Education, which they will need to teach later and therefore master and deeply understand or or the mathematical knowledge for teaching.

Social thinking and attitudes towards diversity

In addition, Primary Education teachers are especially influential in shaping their students’ development in all aspects that cut across different disciplines, acting as role models. The role of a teacher also encompasses a commitment to the education and development of attitudes, values, and skills that enable the comprehensive growth of students (Fuentes Pino, Citation2021) In a world that increasingly values environmental respect, diversity, transparency, inclusion, equity, and within a society that reacts more forcefully to behaviours that violate these values, the teacher’s role as a good role model becomes crucial. The speed of these changes in social consciousness has not allowed for the implicit biases ingrained in our subconscious to change, and therefore, teacher education should consider their detection and the acquisition of specific tools for their conscious and skilful management. While it would be desirable for all professionals to receive this type of training, in the case of teachers, it is particularly important due to their significant contribution to the reproduction of cultural patterns.

Attributes such as openness to diversity, inclusion, and critical thinking have been explicitly highlighted as relevant characteristics for school teachers and, consequently, for their education. For this reason, these characteristics are included in the graduation profiles of most initial teacher education programmes in Chile aligned with the Standards for Primary teaching Programs (Ministerio de Educación, Citation2022); they are both relevant and challenging in the context of the so-called 21st-century skills and an inclusive approach to education.

After analysing teacher training policies and initial teacher training programmes in seven Latin American countries, including Chile, a study by UNESCO-OREALC (Citation2018) concluded that initial teacher training should systematically incorporate 21st-century competencies and inclusive pedagogical strategies into the regulatory frameworks. This integration should encompass specific content, rather than being limited to a transversal approach. It should also be achieved through a well-articulated combination of pedagogical and disciplinary courses, providing not only knowledge but also equipping future teachers with the necessary tools for effective classroom teaching in these areas. The study emphasized the importance of exposing future teachers to opportunities and experiences that increase their awareness of vulnerable or socially disadvantaged contexts. Additionally, it highlighted the need to equip them with pedagogical knowledge and skills essential for successful teaching within these contexts (UNESCO-OREALC, Citation2018).

In a study that examined the presence and relevance of inclusive education in three Primary Education pedagogy programmes in Chile, San Martín et al. (Citation2017) found that although all of them include elements of this approach in their graduation profiles, their approach to inclusive education is fundamentally based on discourse (rather than on the implementation of specific pedagogical practices) and that there is not enough internal coherence regarding what is meant by inclusive education and how it should be developed in the initial teacher training.

On the one hand, developing social thinking in the first school years is essential; it is then when the foundations of the knowledge, skills, attitudes and values essential for a democratic coexistence that aspires to social justice are established (Blondheim & Somech, Citation2019; Fry & O’Brien, Citation2015).

The importance of social thinking and attitudes towards diversity for teacher education is recognized in the requirements of the Chilean National Standards for Primary Teacher Education (Ministerio de Educacion, Citation2022). These Standards explicitly mention that educators play a crucial role in promoting the cultivation of skills and attitudes that nurture the development of a school community and a society founded on principles of respect, transparency, cooperation, and freedom. This entails not only modelling these attributes in interactions with students but also setting clear expectations for student participation in diverse classroom and educational activities.

Standard 6 refers to the teacher’s ability to promote the personal and social development of their students, their participation in democratic life and appreciation of diversity; and Standard 11 highlights teachers’ commitment to continuous learning, through systematic reflection, participation and collaboration. Additionally, the skills involved in social thinking are mentioned in support of the disciplinary Standards of History, Geography and Social Sciences for Primary Teachers Education (Mineduc, 2022).

Moreover, the National Standards for Teaching Profession (Mineduc, 2022) state that teachers must plan inclusive and culturally relevant learning experiences (Standard 3), in addition to creating respectful and inclusive classroom environments (Standard 5). In this context, being able to assess the attitudes towards diversity that students at early stages of teacher education allows universities to implement training plans and strategies to promote learning consistent with an inclusive understanding and appreciation of diversity. This is important because it has been shown that the attitudes with which faculty work have a relationship and impact on the implementation of inclusive practices within the school system.

Conceptual background

Social thinking

Social Thinking refers to a set of higher-order skills that enable elementary school teachers to analyse social reality in the pursuit and promotion of social justice within the educational space (Gutierrez & Pagés, Citation2018; Pagès, Citation2022; Pipkin & Sofía, Citation2005; Westheimer & Kahne, Citation2004). This set of skills allows teachers to contextualize social issues related to their professional practice, develop explanations for them, critically interpret evidence addressing these issues, and propose possible solutions to address them (Gutierrez & Pagés, Citation2018; Pagès, Citation2022; Pipkin & Sofía, Citation2005; Ross, Citation2017).

Specifically, when teachers are confronted with social problems such as child abuse, gender discrimination, delinquency among their students, or educational disparities, for instance, they have the ability to contextualizing them historically and spatially from social, economic, political, and cultural perspectives. Furthermore, they can explain these issues based on the multiple causes that generate them. In addition to critically interpreting evidence of information on these issues, they can ultimately propose educational solutions that consider the complexity of the problems all while adhering to a perspective based on human rights (Gutierrez & Pagés, Citation2018; National Council for the Social Studies NCSS, Citation2013).

From this definition, it is possible to identify four aspects that come into play when teachers engage in social thinking: contextualization of social problems, explanation of social problems, analysis of information on social problems, and development of proposals to address social problems.

These four aspects are captured in the assessment instrument. It is important to mention that in the dimension of ‘development of proposals to address social problems’, the skills of ‘proposing solution ideas’ and ‘maintaining consistent positioning’ can indeed be better and more deeply evaluated through open-ended response questions, primarily because these skills are associated with cognitive domains linked to creation (Marzano, Citation2011). However, the use of closed-ended responses has obvious advantages in terms of simplicity and speed of data processing. Therefore, an option was made to develop. Closed-ended questions in which students select their proposed approach or position. In this regard, the proposed instrument addresses these skills in the sense of selecting predefined responses, but which allow recognizing students’ decisions regarding the skills that are expected to be identified.

Attitudes towards diversity

Attitudes can be conceptualized as a predisposition to evaluate, in a relatively stable and global manner, an object of appraisal as favourable or unfavourable (Briñol et al., Citation2007). In other words, attitudes refer to the degree of positivity, negativity, or ambivalence with which individuals tend to judge a particular object of attitude (Haddock & Maio, Citation2012). According to the multicomponent model of attitudes, attitudes are conceived around three components: the cognitive, affective, and behavioural components. The cognitive component refers to the beliefs that a person expresses about the object of appraisal; the affective component pertains to the feelings and emotions associated with that object; and the behavioural component encompasses both a person’s behaviours towards the object of appraisal and their intentions or action predispositions regarding it (Haddock & Maio, Citation2012). Based on this model, this questionnaire measures the expression of beliefs, affects, and action predispositions held by first-year students majoring in Primary Education.

The object of appraisal regarding which we want to understand attitudes is diversity, understood as the heterogeneity within human groups. This instrument is based on the assumption that diversity is a constitutive property of such groups and is also a valuable and desirable characteristic of them. In this sense, unfavourable attitudes towards diversity are those that, as described by Matus et al. (Citation2019), are based on a reductionist understanding of differences and hierarchize ‘the different’ based on an unproblematic, static, and naturalized reference of normalcy. In short, these are attitudes that would favour the reproduction of hegemonic values that govern systems of differentiation. In contrast, favourable attitudes towards diversity are those that assume a positive valuation of the heterogeneity within human groups, recognizing that differences are constructed relationally and do not privilege certain identities or markers of difference over others. In other words, they would be attitudes consistent with an inclusive conception and valuation of diversity. In addition to these two extremes of the continuum, individuals can also hold ambivalent attitudes towards diversity. In such cases, beliefs, affects, and action predispositions that favour diversity coexist with beliefs, affects, and action predispositions that are unfavourable to it.

Mathematics

The construct to be measured is part of what is referred to as teachers’ competence in teaching mathematics, which is conceptualized as a set of attributes manifested in the execution of teaching and includes all the resources necessary to carry it out (Koeppen et al., Citation2008). Among these resources are the skills, knowledge, attitudes, and motivational variables that form the basis for effective performance in complex situations, in this case, the teaching of mathematics (Kunter et al., Citation2013). Blömeke et al. (Citation2015) consider this competence as a continuum, ranging from the disposition to teach mathematics to actual performance in doing so, with the skills to execute it effectively in between.

Dispositions encompass cognitive characteristics such as the teacher’s professional knowledge, as well as affective and motivational aspects, such as beliefs. In the case of teaching mathematics, the necessary knowledge for effectiveness is diverse (Ball et al., Citation2008) and constructed at different points in the learning trajectory. Beliefs, on the other hand, include conceptions about the nature of mathematics, ideas about what it means to teach and learn mathematics, as well as elements of self-efficacy perception and attitudes towards the discipline.

Now, considering the timing of the assessment to be applied, i.e. at the entry into the teaching programme, it is worth asking whether it is pertinent to measure each component of the described model. In terms of the teaching dispositions of those entering teacher education for Primary education, both in the cognitive and affective domains of competence, it would seem relevant to know their beliefs about mathematics, its teaching and learning, as well as their level of mathematical knowledge of the contents they will teach according to the current official curriculum. This can be accomplished through a standardized ‘pen-and-paper’ test that allows for obtaining high-quality information across various programmes participating in the assessment (Martinez et al., Citation2017).

Taking into account the elements presented earlier, the research question addressed in this work is: Is it possible to characterize Chilean first-year primary education preservice teachers in terms of social thinking, attitudes towards diversity, and mathematics knowledge and beliefs, while making valid inferences from the corresponding test scores for diagnostic purposes?

Methods

In this section, we describe the steps we undertook to develop the three diagnostic assessments. In the first stage, the design of the instrument is described and, in the second stage, the process of collecting evidence of validity is presented. The study expects to report favourable evidence regarding the content, internal consistency of the scores, as well as evidence on the internal structure of the dimensions that compose the construct of each diagnostic assessment.

Stage 1: design of assessment instruments

The development of each diagnostic assessment was guided by the Assessment Framework. The Assessment Framework encompasses various crucial elements. These include the definition of the construct that each test aims to measure, identification of the target population, evaluation of the pertinence of measuring each construct within the context of teacher training in Chile, determination of the administration format, among others. We conducted extensive literature searches including journal articles, handbooks and reviews in Social Thinking, Attitudes Towards Diversity and Mathematics to conceptualize the construct that measures each test and to create the items. Specifically, we conducted exhaustive searches using appropriate keywords to identify relevant peer-reviewed articles, reports, and other scholarly sources. Upon retrieving a substantial pool of sources, the team meticulously reviewed each document, extracting key findings, methodologies, and theoretical frameworks. They synthesized the information obtained from the literature, identifying common themes, trends, and ideas relevant for the elaboration of diagnostic tests.

Each instrument was developed by specialists in social science, attitudes towards diversity, and mathematics, who also work as academics in various teacher education programmes. The entire construction process was guided and monitored by members of the project’s research team. The construction process comprised individual elaboration of items based on the assessment frameworks and collaborative engagement in group work with the project’s research team, facilitating the resolution of uncertainties and refinement of items.

We developed 36 multiple-choice items to measure Social Thinking of pre-service teachers, 55 likert-type items with four options of answer (Strongly Agree, Agree, Disagree, Strongly Disagree) for the Attitudes Toward Diversity Questionnaire and 49 multiple-choice items to measure Mathematical knowledge and 47 likert-type items with four options of answer (Strongly Agree, Agree, Disagree, Strongly Disagree) to assess beliefs of pre-service teachers about mathematics. Closed-ended questions formats were selected to ensure quickly delivery of results reports to participating universities and encourage their timely use.

Stage 2: collection of validity evidence

Sample

The target population for each pilot study comprises students enrolled in pre-service teaching programmes in Chile. The sample design employed a non-random and non-representative convenience sampling approach with the objective of extending invitations to various Chilean universities offering the Pedagogy in Primary Education programme. The primary goal was to secure a significant number of students to facilitate robust psychometric analyses for each of the assessments

The sampling frame is based on the information of the enrolment of the year 2020 in the programme of Pedagogy in Primary Education obtained from the Centro de Estudios Mineduc. In total, during that year, 36 universities in Chile offered the Pedagogy in Basic Education degree, with a combined enrolment of 1120 students.

More than 470 students from 15 different universities participated in the first pilot application. The number of students and universities varies by test, because the institutions were allowed to choose which instruments they wished to participate in. Of the 36 universities, 15 accepted to participate in the pilot. Of these fifteen universities, eight belong to Santiago, the capital of Chile, and seven to other regions of the country. In the second pilot, 489 students from seven universities participated, following the same flexibility to apply assessments according to the interests of each institution. presents the number of valid answers for each assessment and year (2021 and 2022).

Table 1. Number of valid answers per assessment.

Application

The first pilot study was conducted between March 29 and 30 April 2021 and the second between April 4 and 29 April 2022. In both applications, the schedule was variable, as different universities were granted flexibility to participate in the applications at their convenience. Originally, an on-site application was considered, but due to the COVID-19 situation, pre-service teachers completed the assessments from their respective homes. This proved to be convenient, so the tests were also administered in an online format in the next pilot study. On both occasions each participant provided an informed consent before taking the test.

Analysis of validity evidence

We examined the reliability of each assessment, evidence of validity in terms of content and their internal structure. Most of the analyses were carried out using the RStudio software version 3.6.0.

Reliability

To study the reliability, we estimate the reliability of each diagnostic test using Classical Test Theory and we employed Cronbach’s α index (Cronbach, Citation1951). The closer the α value is to 1, the greater the internal consistency of the analysed items. In contexts that do not carry high stakes for examinees, a minimum coefficient value of 0.7 is recommended (e.g. Shultz et al., Citation2013; Celina, H., & Campo, A Citation2005), which is consistent with the diagnostic assessments applied in this study. Additionally, we estimate the reliability using the separation reliability (Wilson, Citation2023) based on the expected a-posteriori (EAP) using Item Response Theory (IRT).

Content

Content based validity of the tests can be obtained from an analysis of the relationship between the content of a test and the construct it is intended to measure (AERA, APA & NCME, Citation2014, p. 14). This involves empirical scrutiny of how well the test content represents the domain being assessed, and its relevance to interpreting test scores. Expert judgements can also contribute to content based validity by assessing the relationship between test components and the underlying construct.

To analyse the content based evidence of validity of assessments, the research involved six distinguished Chilean researchers (two per each instrument) specifically chosen for their extensive expertise in the theory and assessment of Social Thinking, Attitudes Toward Diversity, and Mathematics as they relate to pre-service teachers. They had extensive experience doing research in the constructs that measure each assessment and teaching in Chilean universities. Consequently, these experts were well-qualified to assess the alignment of the items with the designated constructs. In addition, another group of six Chilean measurement experts played a pivotal role, primarily focusing on evaluating the clarity of the test items. These measurement experts were in closer proximity to the intended test takers, the pre-service teachers, underscoring the importance of their precise comprehension of the items.

All experts were invited to join the research via email and the revision of both groups of experts was developed at the same time. Upon their consent to participate, they were provided with three documents containing the instructions to develop the revision, the items from each of the assessments and a Spreadsheet with the criteria to evaluate each item. The first group of experts checked the alignment of items with the constructs and disciplinary aspects such as ‘the ability measured by the item is related to what is stated in the assessment framework’; ‘the item response options are related to the content measured by the item’; ‘the answer options are plausible to be chosen in terms of discipline’, among others. The second group of experts checked measurement aspects such as ‘the item measures the indicator or sub-dimension stated in the assessment framework’; ‘the wording of the item is in the form of a question’; ‘the answer options are plausible to be chosen since they respond logically and effectively to the statement’, among others.

Both groups of experts used a three-point scale for their evaluations, with options including ‘Approved’, ‘Approved with modifications’, and ‘Rejected’. Additionally, experts were encouraged to provide comments on each individual item.

Internal structure

Evidence based on internal structure can indicate the degree to which the relationships among test items and test components conform to the construct on which the proposed test score interpretations are based. The specific types of analyses and their interpretation depend on how the test will be used (AERA, APA & NCME, 2014, p.16).

Item analysis

We use the Rasch Model for Social Thinking Test and Mathematics (knowledge section) and Partial Credit Model for Attitudes Toward Diversity Questionnaire and Mathematics (beliefs section). Infit, Outfit and difficulty statistics were calculated from these IRT models. Then, the final estimation of the difficulty parameters of the items and of the preservice’ ability was carried out, obtaining the Wright maps for each of the assessments.

Factor analysis

To examine the internal structure of each instrument, we analysed the relationships between the items, expecting a unidimensional structure in all of them. Specifically, confirmatory factor analyses were performed to verify the unidimensionality of the tests. In evaluation, particularly in the context of measuring constructs such as attitudes, beliefs, or skills, we often aim to ensure that the assessment tools we use have a unidimensional internal structure. This means that the items or questions within the evaluation instrument are all measuring the same underlying construct or dimension. When all items within an evaluation instrument are measuring the same underlying construct, it ensures clarity in what is being assessed. This clarity is crucial for both the evaluator and the respondent. Respondents can better understand the purpose of the evaluation, leading to more accurate responses. Similarly, evaluators can interpret the responses more reliably when they know that each item is contributing to the measurement of a single construct. For this purpose, several goodness-of-fit measures were reviewed, which were examined based on a series of cut-off points established in the literature (Hooper et al., Citation2008). If the model shows goodness-of-fit indices within the ranges established by these cut-off points, it is considered that the factor structure examined shows an adequate fit to the data.

Findings

The evidence presented below provides background information for improvement regarding the validity of the scores for each assessment. The results are presented in three sections: content based validity, reliability and internal structure evidence.

Validity evidence based on content

The items of each assessment were individually analysed in their content by six specialists in each of the areas of the construct and in teacher training. They agreed on the ability of each assessment to evaluate social thinking, attitudes towards diversity, knowledge and beliefs towards mathematics. The following is an example of an item from each assessment instrument.

Example of a Social Thinking Test item

Example of an Attitudes Toward Diversity Questionnaire item

Example of a Mathematics Knowledge item

Table

Examples of a Mathematics Beliefs item

Reliability of each assessment

The results of the reliability analysis presented in show that in the pilot conducted in 2021, Attitudes Toward Diversity Questionnaire and both Mathematics assessments (knowledge and beliefs) have an acceptable reliability coefficient, more than 0.7. These results are similar using a de Cronbach and the separation reliability based on EAP. The Social Thinking Test, on the other hand, did not reach 0.7 in 2021, but it did in 2022 (), being acceptable with a de Cronbach and separation reliability based on EAP. The other assessments remained relatively similar to the previous year.

Table 2. Reliability of diagnostic tests for pre-service teachers, pilot 2021.

Table 3. Reliability of diagnostic tests for pre-service teachers, pilot 2022.

Validity evidence on the internal structure of each assessment:

From the analysis of the IRT models from the Wright maps, it was identified that the difficulties of the items of each evaluation behave as expected. Preservice teachers are distributed throughout the response space in both applications (2021 and 2022), as observed in the following Wright maps.

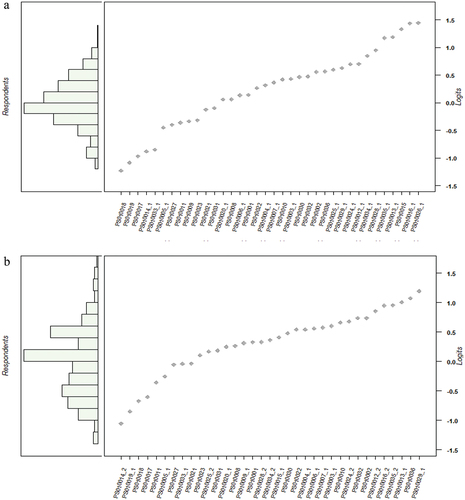

The Wright map represents both items and respondents on the same scale, with individuals displayed in the left histogram and items positioned on the x-axis, arranged from easiest to most difficult. Since the social thinking test consisted of multiple-choice questions with a single correct answer, in the grey points indicate the estimated difficulty of an item corresponding to the respondent’s ability estimated with a 0.5 probability of answering it correctly.

Figure 1. a: Wright map social thinking test, pilot 2021 ; b: Wright map social thinking test, pilot 2022.

In this case, we observe that the scale’s coverage is quite good, with a slight improvement in 2022 over 2021. This suggests that the test is well-adjusted in terms of item difficulty to the target population, as it gathers information across the entire difficulty range. For further test development, it might be possible to add some items at the high difficulty end to improve precision when studying respondents on that tail.

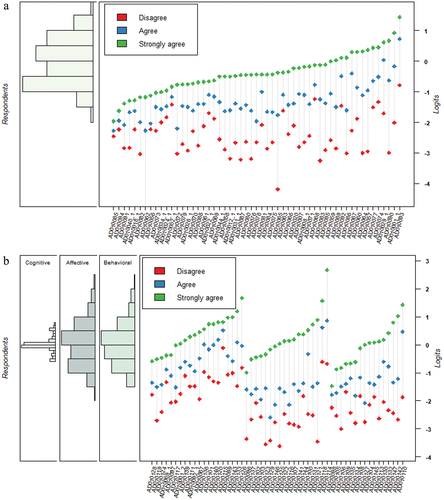

In the attitudes to diversity test, data were initially estimated as unidimensional for the first pilot and multidimensional for the second pilot to better align the analytical approach with the conceptual one (see below). Since the response format corresponds to a 4-level agreement scale, the coloured points represent the thresholds between the response categories for each item, as indicated in the legend of . It’s worth noting that two items with a difficulty level easier than −4 logits were excluded from the map representation to improve visual clarity. There is room for improvement in terms of item difficulty, as the items appear to be relatively easy compared to the ability demonstrated by the target population. This may be attributed to a certain degree of social desirability in the responses to the questions (Krumpal, Citation2013).

Figure 2. a: Wright map attitudes toward diversity questionnaire, pilot 2021; b: Wright map attitudes toward diversity questionnaire, pilot 2022.

Table 4. Classification of goodness of fit indicators.

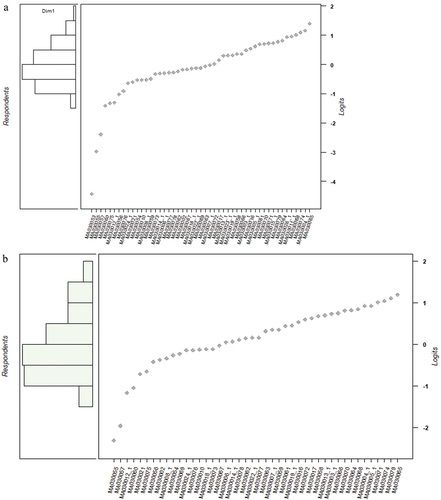

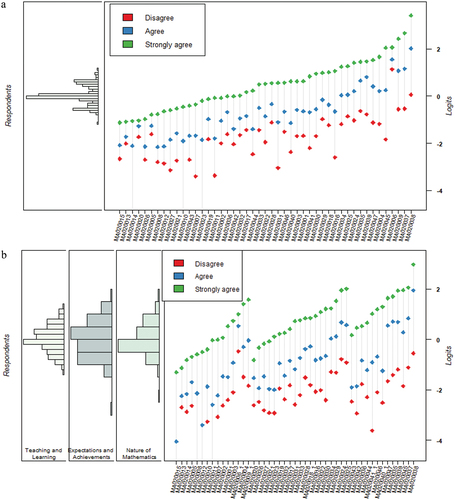

In the context of the mathematics test, the knowledge section appears to be generally well-balanced in terms of coverage (). However, it’s worth noting that the first three items appear to be too easy for the target population, as indicated by the results of both pilot studies. To enhance the precision for future test development, it may be advisable to consider adding some items at the higher difficulty to improve precision when studying respondents in that range.In the mathematics beliefs section (), the data analysis initially assumed unidimensionality for the first pilot but shifted to a multidimensional approach in the second pilot to align with the conceptual framework (refer to below). To enhance visual clarity, two items with a difficulty level below −4 logits were excluded from the mapped representation.

Figure 3. a: Wright map mathematics (knowledge section), pilot 2021; b: Wright map mathematics (knowledge section), pilot 2022.

Figure 4. a: Wright map mathematics (beliefs section), pilot 2021; b: Wright map mathematics (beliefs section), pilot 2022.

There is potential for improvement, particularly within the ‘teaching and learning dimension’, where the items appear to be relatively easy in comparison to the demonstrated abilities of the target population. This discrepancy may be influenced by a degree of social desirability bias in respondents’ answers (Krumpal, Citation2013) and should be addressed for future improved versions of the test.

Additionally, we conducted confirmatory factor analysis to verify the uni-dimensionality of each assessment. The results of goodness of fit indicators show that Social Thinking Test demonstrates a goodness of fit to data and it is unidimensional. For Attitudes towards Diversity Questionnaire and Mathematics we could not verify the uni-dimensionality ()It means that the assumption that all items within the test measure a single underlying construct or dimension did not hold true. In other words, the analysis revealed that the items in the instrument were not all tapping into the same concept as initially we hypothesized. This could occur due to various reasons such as unclear item wording, overlapping constructs, or inherent multidimensionality of the concept being measured. Based on these results, the analytical approach was adjusted for the second pilot study, and a multidimensional approach was adopted to model the data for assessing attitudes towards diversity and mathematics beliefs.

Summary and final discussion

From the analysis of these results, we can point to the themes associated with the objective of the research initially posed. With respect to the validity evidence based on content, we find favourable evidence from experts that the items of the three diagnostic assessments measure the social thinking, attitudes towards diversity, knowledge and beliefs towards mathematics as we expected. Regarding the internal consistency of test scores, our findings indicate the presence of satisfactory reliability coefficients across all three diagnostic assessments, underscoring the precision inherent in each test for diagnostic purposes. In the context of evidence based on internal structure and a comprehensive examination of the Item Response Theory (IRT) models through the Wright maps, our analysis revealed that the item difficulties within each assessment conformed to our expectations. Specifically, preservice teachers exhibited a distribution across the response space in both the 2021 and 2022 pilots. It is noteworthy that a uni-dimensional structure was identified in the social thinking test; however, our initial expectation of uni-dimensionality in the attitudes towards diversity questionnaire, as well as in the knowledge and beliefs towards mathematics, could not be substantiated.

In light of the findings discussed, several key improvements can be made to enhance the quality and precision of the diagnostic assessments. First and foremost, while the evidence from experts supports the content based validity of the tests developed, further steps should be taken to continuously update and refine the test items to ensure that they accurately measure social thinking, attitudes towards diversity, and knowledge and beliefs towards mathematics. This could involve regular expert reviews and periodic revisions to keep the content in line with the evolving field of study and their alignment with the Chilean National Standards for Teaching Profession. Additionally, with regard to the identification of a uni-dimensional structure in the social thinking test, it may be beneficial to revisit the design and structure of the attitudes towards diversity questionnaire, as well as the knowledge and beliefs towards mathematics sections. A more nuanced approach, potentially incorporating a multidimensional perspective, may be necessary to better capture the complex nature of these constructs. Exploring potential subdomains or factors within these assessments could provide a more comprehensive understanding of preservice’ teachers responses. Moreover, a continuous monitoring and improvement process for each test’s internal consistency should be established. Ensuring that reliability coefficients remain consistently satisfactory over time is essential for maintaining the precision and trustworthiness of the diagnostic assessments. Regular checks for any potential sources of inconsistency or error in scoring should be part of the ongoing quality control process (American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association y National Council on Measurement in Education, Citation2014).

The findings of this study illuminate the pivotal role that diagnostic assessments play in safeguarding the quality and efficacy of teacher education programmes in the Chilean educational context. By methodically assessing the knowledge, skills, and dispositions of prospective educators, these examinations serve as instruments for the discernment of competencies and areas necessitating enhancement. This discernment empowers universities to individualize their curricula to better cater to the distinctive requirements of their preservice teachers. Furthermore, within the backdrop of Chile’s recent comprehensive educational reforms, diagnostic tests for preservice teachers assume paramount significance in aligning teacher training with the nation’s educational objectives and standards. Consequently, these evaluations provide empirical foundations for informed decision-making among policymakers pertaining to curriculum design, teacher preparation, and professional development initiatives. Additionally, these assessments are instrumental in identifying disparities in the preparedness of preservice teachers hailing from diverse backgrounds. Subsequently, the acquired insights can be strategically employed to institute targeted support and interventions, thereby ensuring equitable access to the requisite resources and training for all aspiring educators to thrive in their future classrooms.

On the other hand, the findings confirm the relevance of the measurement of these constructs for the teacher education programmes. As the literature shows, social thinking refers to a set of higher-order skills that enable elementary school teachers to analyse social reality in the pursuit and promotion of social justice within the educational space (Gutierrez & Pagés, Citation2018; Pagès, Citation2022; Pipkin & Sofía, Citation2005; Westheimer & Kahne, Citation2004). The measurement of social thinking in teacher education is crucial in preparing teachers to facilitate conversations and critical thinking around topics such as social justice, inequality, and civic engagement, empowering students to become informed and engaged citizens. Additionally, social thinking in Chile is relevant to promote inclusive education. Chile, like many other countries, is increasingly embracing the principles of inclusive education. This approach emphasizes the inclusion of students with diverse backgrounds, abilities, and needs within mainstream classrooms. Social thinking skills are essential for teachers to create inclusive and supportive learning environments, ensuring that all students can thrive regardless of their individual differences. In addition, Chilean society places a significant emphasis on democratic values and active participation in civic life. Social thinking skills help teachers cultivate students’ understanding of democratic principles, critical thinking, and their ability to engage in constructive dialogue and debate. These competencies are pivotal for shaping responsible, informed, and engaged citizens. Finally, many countries use international standards to guide their educational policies and practices. Social thinking aligns with these standards by fostering well-rounded, globally competent teachers who can meet the evolving demands of education worldwide.

Regarding attitudes towards diversity, the Chilean National Standards for Teaching Profession defines that teachers must plan inclusive and culturally relevant learning experiences as well as creating respectful and inclusive classroom environments (Mineduc, 2021). As a consequence, in teacher education, fostering cultural sensitivity and awareness is vital. A positive attitude towards diversity instilled during a teacher’s training enables them to appreciate and respect the cultural, ethnic, and social diversity they will encounter in their future classrooms. This, in turn, helps in creating an inclusive and welcoming environment for all students, regardless of their background. Additionally, attitudes towards diversity are closely linked to the ability to implement inclusive teaching practices. Teachers with positive attitudes towards diversity are more likely to adapt their instructional methods, materials, and assessments to meet the diverse needs of their students, thus ensuring equitable educational opportunities for all. Moreover, in Chile, as in many other countries, classrooms often include students with various learning styles, abilities, and backgrounds. Teachers with positive attitudes towards diversity are better equipped to tailor their teaching methods and interventions to meet the unique needs of each student, thereby increasing student success and engagement. Finally, attitudes towards diversity are essential for promoting civic education and global competence. Encouraging students to embrace diversity cultivates empathy and the ability to engage in constructive dialogue about social and global issues, all of which are vital for active and responsible citizenship.

Furthermore, as the literature suggests, initial teacher training should incorporate specific content well-articulated with a combination of pedagogical courses, providing not only knowledge but also equipping future teachers with the necessary tools for effective classroom teaching in these areas (UNESCO-OREALC, Citation2018). The measurement of knowledge and beliefs in Mathematics is relevant to prepare future educators to provide high-quality mathematics instruction. For teachers, it is not sufficient to have a deep understanding of a subject; they must also possess pedagogical content knowledge, which includes knowing how to teach the subject effectively. Teacher education should equip future educators with the pedagogical skills and strategies required to make mathematical concepts accessible and engaging to students. This involves understanding the challenges students might face in learning mathematics and how to address those challenges. In addition, the measurement of mathematics is relevant to promote positive attitudes towards the subject in students. Teachers who hold positive beliefs about mathematics and its relevance can contribute to shaping their students’ attitudes towards the subject. Enthusiastic and knowledgeable teachers are more likely to inspire students to appreciate and engage with mathematics. This is especially vital in dispelling negative stereotypes and maths anxiety. Moreover, in many educational systems, including in Chile, there are specific content standards that students are expected to meet at various grade levels. Teachers must be well-versed in these standards to ensure their instruction aligns with curriculum requirements. A strong knowledge of mathematics and a belief in its significance are foundational for maintaining this alignment. As a result, the initial measurement of that knowledge in preservice teachers is key to guarantee that.

Finally, one limitation of this study pertains to the potential influence of social desirability bias on the results obtained through the attitudes towards diversity questionnaire and the mathematics beliefs section. As with any self-report assessment, there exists the risk that respondents may provide responses they believe align with societal expectations or values, rather than reflecting their true attitudes. Preservice teachers may be inclined to present themselves in a favourable light, particularly in a context related to diversity and inclusion in educational contexts, leading to response patterns that may not fully represent their genuine perspectives. While efforts were made to minimize this bias, such as ensuring confidentiality, the inherent challenge of gauging true attitudes, especially on sensitive topics, remains a limitation that should be acknowledged when interpreting the findings of this study. Future research may benefit from exploring additional methods or triangulating data to mitigate the potential impact of social desirability on the assessment’s outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The research project on which this paper is based was funded by the Ministry of Education of Chile, through the Fund for the Promotion of Scientific and Technological Development (Fondo de Fomento al Desarrollo Científico y Tecnológico), project: FONDEF ID19I10050, years 2020-2022).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. According to this perspective, professional competence can be also conceived as an explanatory variable for processes and outcomes, such as teaching characteristics and students’ outcomes among others (Kaiser & König, Citation2019)

References

- American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association y National Council on Measurement in Education. (2014). Standards for educational and psychological testing. American Educational Research Association.

- Ávalos, B. (2002). Profesores para Chile: Historia de un Proyecto. Ministerio de Educación.

- Ávalos, B. (2003). La formación docente inicial en Chile. In [Initial teacher education in Chile]. Digital Observatory for Higher education in Latin America and the Caribbean. https://www.cfe.edu.uy/images/stories/pdfs/comisiones/autoevaluacion/for_doc_chile.pdf

- Ball, D. L., Thames, M. H., & Phelps, G. (2008). Content knowledge for teaching: What makes it special? Journal of Teacher Education, 59(5), 389–407. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487108324554

- Blömeke, S., Gustafsson, J.-E., & Shavelson, R. (2015). Beyond dichotomies: Competence viewed as a continuum. Zeitschrift für Psychologie, 22(3), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1027/2151-2604/a000194

- Blömeke, S., & Kaiser, G. (2017). Understanding the development of teachers’ professional competencies as personally, situationally, and societally determined. In D. J. Clandinin & J. Husu (Eds.), International handbook of research on teacher education (pp. 783–802). Sage.

- Blondheim, G. F., & Somech, A. (2019). Student organizational citizenship behavior: Nature and structure among students in elementary and middle schools. Teaching and Teacher Education, 83, 110–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2019.04.010

- Briñol, P., Falces, C., & Becerra, A. (2007). Actitudes. Psicología social, 3, 457–490.

- Celina, H., & Campo, A. (2005). Aproximación al uso del coeficiente alfa de Cronbach. Revista Colombiana de Psiquiatría, 34(4), 572–580. http://redalyc.uaemex.mx/pdf/806/80634409.pd

- Consejo Nacional de Educación. (2023). Tendencias de pedagogía en Chile. https://www.cned.cl/sites/default/files/ppt_tendenciaspedagogias.pdf

- Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16(3), 297–334. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02310555

- Darling-Hammond, L., Wei, R. C., & Johnson, C. M. (2009). Teacher preparation and Teacher learning: A changing policy landscape. In G. Sykes, B. L. Schneider, & D. N. Plank (Eds.), Handbook of education policy research (pp. 613–636). American Educational Research Association and Routledge.

- Freeman, D., Katz, A., Gomez, P. A., & Burns, A. (2015). English-for-teaching: Rethinking teacher proficiency in the classroom. ELT Journal, 69(1), 129–139. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccu074

- Fry, S. W., & O’Brien, J. (2015). Cultivating a justice orientation toward citizenship in preservice elementary teachers. Theory & Research in Social Education, 43(3), 405–434. https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2015.1065530

- Fuentes Pino, A. (2021). Lazos significativos entre educadores y estudiantes. Herramientas para fortalecer el vínculo pedagógico. Organización de Estado Iberoamericano.

- García-Huidobro, J. E., & Cox, C. (1999). La reforma educacional chilena 1990–1998. Visión de Conjunto. In C. Cox (Ed.), La reforma Educacional Chilena (pp. S. 7–50). Popular.

- Giaconi, V., Gómez, G., Jiménez, D., Gareca, B., Durán Del Fierro, F., & Varas, M. L. (2022). Evaluación diagnóstica inicial en la formación inicial docente en Chile y su relación con contextos institucionales. Pensamiento educativo, 59(1), 00104. https://doi.org/10.7764/pel.59.1.2022.4

- Giaconi, V., Varas, L., Ravest, J., Martin, A., Gómez, G., Queupil, J. P., & Díaz, K. (2019). Estándares técnicos para el diagnóstico inicial de los futuros docentes. Una propuesta basada en evidencia. Informe Final Proyecto 170009, Undécimo Concurso FONIDE. Recuperado de https://centroestudios.mineduc.cl/wp-content/uploads/sites/100/2021/08/009-Giaconi-FINAL.pdf. MINEDUC.

- Guerriero, S. (Ed.). (2017). Pedagogical knowledge and the changing nature of the teaching profession. OECD.

- Gutierrez, M. C., & Pagés, J. (2018). Pensar para intervenir en la solución de las injusticias sociales (Primera Edición). Editorial UTP. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/328878279_Pensar_para_intervenir_en_la_solucion_de_las_injusticias_sociales

- Haddock, G., & Maio, G. R. (2012). The psychology of attitudes. Sage.

- Higher Education Information Service. (2023). Informes matrícula en educación superior en Chile. https://www.mifuturo.cl/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Matricula-_en_Educacion_Superior_2023_SIES.pdf

- Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., & Mullen, M. R. (2008). Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 6(1), 53–60.

- Jiménez, D., & Taut, S. (2015). Das bildungssystem in Chile unter besonderer berücksichtigung der Rolle der lehrerinnen und lehrer als schlüssel der bildungsqualität [the education system in Chile with special consideration of the role of teachers as key to educational quality. In V. Oelsner & C. Richter (Eds.), Bildung in Lateinamerika: Strukturen, Entwicklungen, Herausforderungen [Education in Latin America: Structures, Developments and Challenges] (pp. 98–118). Waxmann-Verlag.

- Kaiser, G., & König, J. (2019). Competence measurement in (mathematics) teacher education and beyond: Implications for policy. Higher Education Policy, 32(4), 597–615. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41307-019-00139-z

- Koeppen, K., Hartig, J., Klieme, E., & Leutner, D. (2008). Current issues in competence modelling and assessment. Zeitschrift für Psychologie / Journal of Psychology, 216, 60–72. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Dominique-Rauch/publication/232495759_The_concept_of_competence_in_educational_contexts/links/00b7d537c6f1c7ec23000000/The-concept-of-competence-in-educational-contexts.pdf

- Krumpal, I. (2013). Determinants of social desirability bias in sensitive surveys: A literature review. Quality & Quantity, 47(4), 2025–2047. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-011-9640-9

- Kunter, M., Klusmann, U., Baumert, J., Richter, D., Voss, T., & Hachfeld, A. (2013). Professional competence of teachers: Effects on instructional quality and student development. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105(3), 805. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032583

- Martinez, M. V., Rojas, F., Chandía, E., Ortiz, A., Perdomo, J., Reyes, C., & Ulloa, R. (2017). Informe final. Diagnóstico de las creencias y conocimientos iniciales de estudiantes de pedagogía básica sobre la matemática escolar, su aprendizaje y enseñanza. https://bibliotecadigital.mineduc.cl/bitstream/handle/20.500.12365/16122/FONIDE-FX11624-Martinez.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Marzano, R. J. (2011). Formative assessment & standards-based grading. Solution Tree Press.

- Matus, C., Rojas-Lasch, C., Guerrero-Morales, P., Herraz-Mardones, P. C., & Sanyal-Tudela, A. (2019). Difference and Normality: Ethnographic Production and Intervention in Schools/Diferencia y normalidad: producción etnográfica e intervención en escuelas. Magis: Revista Internacional de Investigación en Educación, 11(23), 23–39. https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.m11-23.dnpe

- Ministerio de Educación. (2004). La educación chilena en el cambio de siglo: políticas, resultados y desafíos. MINEDUC.

- Ministerio de Educación. (2022). Estandares Pedagogicos y Disciplinarios para Carreras de Pedagogia en Educacion General Basica. MINEDUC.

- Mourshed, M., Chijioke Ch, Y., & Barber, M. (2010). How the world’s most improved school systems keep getting better. McKinsey & Company. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/education/our-insights/how-the-worlds-most-improved-school-systems-keep-getting-better

- Musset, P. (2010). Initial Teacher Education and Continuing Training Policies in a comparative perspective: Current practices in OECD countries and a Literature Review on Potential Effects. OECD Education Working Papers, No. 48. OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/5kmbphh7s47h-en

- National Council for the Social Studies (NCSS). (2013). College, Career & Civic Life C3 framework for social studies state standards: Guidance for enhancing the rigor of K-12 civics, economics, geography and history. (Silver Spring, MD: NCSS, 2013). https://uknowledge.uky.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1000&context=edc_reports

- Pagès, J. (2022). Enseñar a enseñar historia: la formación didáctica de los futuros profesores. Reseñas de Enseñanza de la Historia, (2), 175–209. https://revele.uncoma.edu.ar/index.php/resenas/article/view/3994

- Pipkin, D., & Sofía, P. I. (2005). La Formación del Pensamiento Social en la Escuela Media: Factores que Facilitan y Obstaculizan su Enseñanza. Clío & AsociadosLa Historia enseñada, 1(8), 85–94. https://doi.org/10.14409/cya.v1i8.1593

- Richardson, V. (1996). The role of attitudes and beliefs in learning to teach. In J. Sikula (Ed.), Handbook of research on teacher education (pp. 102–119). Macmillan.

- Ross, W. (2017). Rethinking of social studies: Critical pedagogy in pursuit of dangerous citizenship. Information Age Publishing.

- San Martín, C., Villalobos, C., Muñoz, C., & Wyman, I. (2017). Pre-service teacher training for inclusive education. Analysis of three Chilean programs of pedagogy in elementary education that enfasize inclusive education. Calidad En La Educación, 46(46), 20–52. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-45652017000100020

- Schleicher, A. (2016). Teaching excellence through professional learning and policy reform. OECD.

- Shulman, L. S. (1986). Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educational Researcher, 15(2), 4–14. https://doi.org/10.2307/1175860

- Shultz, K. S., Whitney, D. J., & Zickar, M. J. (2013). Measurement theory in action: Case studies and exercises. Routledge.

- Thompson, A. (1992). Teachers’ beliefs and conceptions. Handbook of research on mathematics teaching and learning: A project of the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, 127–146. https://books.google.com/books?hl=es&lr=&id=N_wnDwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA127&dq=Thompson,+A.+(1992).+Teachers’+beliefs+and+conceptions:+A+synthesis+of+the+research.+In+D.+A.+Grouws+(Ed.),+Handbook+of+research+on+mathematics+teaching+and+learning.+New+York:+MacMillan.&ots=zlZucqvL_H&sig=p7Tq1mMV3vG1zHpEa7KH5ek57xY#v=onepage&q&f=false

- Townsend, T., & Bates, R. (2007). Handbook of teacher education: Globalisation, standards and professionalism in times of change. Springer.

- UNESCO-OREALC. (2018). Formación inicial docente en competencias para el siglo XXI y pedagogías para la inclusión en América Latina. Análisis comparado de siete casos nacionales. Estrategia Regional sobre Docentes OREALC-UNESCO Santiago. https://bibliotecadigital.mineduc.cl/handle/20.500.12365/17604

- Weinert, F. E. (2001). Concept of competence: A conceptual clarification. In D. S. Rychen & L. H. Salganik (Eds.), Defining and selecting key competencies (pp. 45–66). Hogrefe.

- Westheimer, J., & Kahne, J. (2004). Educating the “good” citizen: Political choices and pedagogical goals. PS: Political Science & Politics, 37(2), 241–247. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096504004160

- Wilson, M. (2023). Constructing measures: An item response modeling approach. Taylor & Francis.

- Yang, X., Kaiser, G., König, J., & Blömeke, S. (2018). Professional noticing of mathematics teachers: A comparative study between Germany and China. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 17(5), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10763-018-9907-x