ABSTRACT

The study contributes to the nascent field of principals’ curriculum leadership of cross-curricular teaching. While principals’ curriculum leadership is often mentioned as a precondition when implementing cross-curricular teaching, it is a role rarely explored. This qualitative study examined Finnish Lower Secondary School (grades 7–9) principals’ experiences implementing cross-curricular teaching. Finnish principals are granted significant professional autonomy and trust from the curriculum and society. However, the latest national curriculum reform (2014) mandates them to implement cross-curricular teaching, providing only general guidelines and no extra funding or resources. Interviews with six principals were analysed hermeneutically to understand how they mediated within and between internal (e.g. faculty) and external (e.g. curriculum) demands. Non-affirmative education theory informed the analysis exploring curriculum leadership’s multi-level, interpersonal and mediating aspects. The implications are that principals’ curriculum leadership means complex mediation between affirmation and non-affirmation while considering epistemic practices (e.g. work agreements, teaching practices) and values (e.g. teacher autonomy). Collaboration on several educational levels (faculty, municipality) may support principals’ curriculum leadership when organizing new pedagogical practices, interpreting the curriculum, and evaluating student learning.

Introduction

Transnational organizations (e.g. OECD) have promoted cross-curricular or interdisciplinary approaches in education since the 1970s, often leading to changes in national curricula and school teaching practices (Klausen & Mård, Citation2023; Scott, Citation2015). The rationale for cross-curricular teaching includes addressing global problems (e.g. poverty, climate change, immigration) and fostering a range of skills among students (e.g. critical thinking, citizenship, motivation) (Klausen & Mård, Citation2023; Lenoir & Hasni, Citation2016; Voogt & Roblin, Citation2012). By combining different school subjects, teachers and students are supposed to be able to address complex issues better than within one subject (Lysberg, Citation2022; Scott, Citation2015).

Previous research on cross-curricular teaching has often investigated the pupils’ and teachers’ perspectives, leaving the principal’s role less explored. However, principals’ leadership is considered a precondition for implementing cross-curricular teaching (Braskén et al., Citation2020; Haapaniemi et al., Citation2021; Wallace et al., Citation2007). Principals are the ones who lead the schools in the transition from individualistic school culture to cross-curricular teacher collaboration, requiring new ways of organizing, planning, teaching, and evaluating education (Hargreaves, Citation2019; Lysberg, Citation2022; Mård & Hilli, Citation2022). We understand these aspects of the principal’s work as a curriculum leader. The reason for examining principals is that Finnish principals must be teachers at the school level they lead. In other words, principals have a dual role as teachers and principals when implementing curriculum reforms, which may cause tensions and challenges. This study aims to contribute to the nascent field of principal’s curriculum leadership when implementing cross-curricular teaching.

There is no shared or commonly agreed-upon definition of curriculum leadership. We follow the suggested conceptualization of Uljens (Citation2023b) that curriculum leadership includes selecting the aims, contents, and methods of schooling. These are central notions in how the curriculum is intended, practised, and experienced in a public school system. Curriculum leadership should create directions and conditions for changes in the curriculum to influence the faculty member’s learning about, for example, cross-curricular teaching. Therefore, curriculum leadership covers initiating, developing, implementing, and evaluating educational measures. Furthermore, this study argues that curriculum leadership must be created on several educational (e.g. classroom, school, municipality, national) levels, with a long-term commitment to providing resources and links within the school and other actors (Uljens et al., Citation2016; Wallace et al., Citation2007).

Transnational organizations and international tests have influenced many national curricula, stipulating that new skills and knowledge are required in an increasingly globalized world (Haapaniemi et al., Citation2021). The study explored the experiences of Swedish-speakingFootnote1 Finnish Lower Secondary (grades 7–9) principals when implementing cross-curricular teaching within their faculty. While Finland has been a high-performing country in international tests (e.g. PISA and PIRLS), the results have steadily declined (Symeonidis & Schwarz, Citation2016). In such a light, Finland has undertaken a significant education reform process, renewing the core curriculum for pre-primary, primary, and secondary education to emphasize specific skills and knowledge, with one example being the introduction of mandatory cross-curricular teaching in 2014.

The research question for the study is: How do principals experience their role as curriculum leaders when mediating between the curriculum and educational levels in the school and municipality when implementing cross-curricular teaching? We analysed six interviews hermeneutically, supported by non-affirmative education theory (NAT henceforth). NAT allowed us to explore pedagogical aspects of curriculum leadership and dynamics between and within different educational levels, something previous research often disregards (Lantela et al., Citation2024; Neumerski, Citation2013; Sebastian et al., Citation2017). We were specifically interested in curriculum leadership as a mediating activity where the principal responds to external (e.g. curriculum) and internal (e.g. faculty) demands (Shaked & Schechter, Citation2017).

From a NAT perspective, mediation means principals make decisions while considering relevant epistemic practices (e.g. teaching practices, curriculum) and values (i.e. teacher autonomy), sometimes by affirming the status quo and sometimes by challenging it, i.e. by not affirming it (Benner, Citation2023). One of the goals of a principal’s curriculum leadership is to influence and support teachers’ professional development. To understand how principals can support teachers pedagogically, we submit that a theory of learning in an organizational context, something NAT offers, is needed. A NAT perspective invites different educational actors (e.g. principals and faculty members) to reflect on and analyse what should be preserved or changed, mediating between affirmative and non-affirmative positions (Benner, Citation2023).

We continue the study by setting the scene for cross-curricular reforms in Finland. The study then provides a literature review of curriculum leadership and the theoretical framework of curriculum leadership and professional learning from a NAT perspective. The article continues with a description of the study’s context, methodology, and findings and concludes with a discussion of the implications of this study.

The case of cross-curricular teaching in Finland

Cross-curricular teaching attempts to bridge the gap between the school and the surrounding world by making learning more meaningful and connected to phenomena that students find interesting (McPhail, Citation2018). As many definitions exist (for example, multi-, inter-, and transdisciplinary teaching, integrated teaching, and fused curricula), cross-curricular teaching is difficult to define as a concept (Klausen & Mård, Citation2023; Lenoir & Hasni, Citation2016). For example, Gresnigt et al. (Citation2014) define it as a continuum, with isolated subjects on the one hand and the complete abandonment of subjects on the other. Here, we use the term cross-curricular teaching, meaning that teachers individually or collaboratively combine two or more school subjects in their teaching. Cross-curricular teaching functions as a meta-concept,Footnote2 encompassing all teaching approaches crossing subject boundaries (Klausen & Mård, Citation2023).

The national core curriculum in Finland is the organizational and intellectual centrepiece of education (Lähdemäki, Citation2018). The Finnish National Agency for Education (FNAE) is responsible for creating and governing national objectives and the distribution of lesson hours within each subject (Pietarinen et al., Citation2017). The core curriculum works as a soft governance tool. It purposely formulates vague goals and guidelines for the education providers (usually the municipalities) to interpret and transform to suit the local context (Chong & Graham, Citation2017). Soft governance in Finland means considerable variation in education between different municipalities depending on the region’s political, financial, and pedagogical visions. Thus, there is no national solution for how education is organized, and education providers and principals need to be sensitive to the local and contextual nuances (Norman & Gurr, Citation2020).

Subsequently, a decentralized model gives local practitioners considerable autonomy. For example, Finland has no state or municipality-level school inspections, and trust in educational practitioners is considered quality assurance (Mäkiharju & Smeds-Nylund, Citation2023). However, introducing cross-curricular teaching as a mandatory feature in the curriculum in 2014 was a change that affected subject teachers’ professionalism because cross-curricular activities cannot be opted out of. According to Frederiksen and Beck (Citation2014), cross-curricular teaching challenges the didactical positions of subject teachers, covering their understanding and implementation of the subjects in the curriculum. In cross-curricular teacher collaboration, didactical positions must be respected and re-negotiated for new teaching practices to form (Mård & Hilli, Citation2022).

The Finnish curriculum is presented through a subject-centred framework (cf. Lehrplan), establishing content for each subject (Haapaniemi et al., Citation2021). Such a subject-based curriculum creates a particular division of labour, knowledge processes and subject-teacher identities. In Finland, subject teachers in Lower Secondary schools usually teach their subjects individually and do not have experience or training in integrative or cross-curricular teaching (Niemelä & Tirri, Citation2018). Furthermore, the curriculum reform fits into existing collective agreements of teacher work, and no extra resources are provided, thus leaving it to municipalities and schools to organize and potentially fund cross-curricular teaching (Pöntinen, Citation2019).

The principal’s roles include engaging practitioners in shared sense-making to reform a curriculum and encouraging cross-curricular teacher collaboration by trusting and respecting the autonomy of the teachers collaborating (Hargreaves, Citation2019; Pietarinen et al., Citation2017). School leaders must consider faculty members’ professionalism, didactical positions, and organization by providing time and resources for cross-curricular teaching (Mård & Hilli, Citation2023), suggesting mediation between school and faculty levels.

Finnish principals must be qualified teachers at their teaching level, meaning they usually have teaching and curriculum leadership experience on a classroom level. In larger schools, there may be, besides a principal, a vice-principal and more supporting staff. Principals in larger schools usually do not have teaching responsibilities and work as full-time leaders (Lähdemäki, Citation2018). In rural areas, it is common for subject teachers to teach on several school levels and for principals to lead several small schools (Karlberg-Granlund, Citation2023). Principals from both rural and urban schools participated in this study. There was a considerable variation in how cross-curricular activities are conducted between schools. Some schools had long-term and school-based projects spanning over one or several years, involving many teachers and pupils; others had short-term cross-curricular projects involving only some pupils and teachers (see ).

Table 1. Contextual information on participants.

A literature review of curriculum leadership

Often, leadership has an almost mythological character, and leaders are usually considered to influence their followers and the organization positively and, in a top-down manner, disregarding organizational and contextual factors (Alvesson, Citation2019). There has been an upsurge in educational leadership research worldwide (Bush & Glover, Citation2014; James et al., Citation2020) and in a Nordic context (Ahtiainen et al., Citation2023; Gunnulfsen et al., Citation2022, Citation2023; Moos et al., Citation2020). Despite this, it is still an under-theorized field (Alvesson, Citation2019; Evans, Citation2022; Wang, Citation2018). Thus, to avoid conceptual confusion, we will define how we understand leadership’s educational and pedagogical aspects in this study.

Educational leadership refers to any activity in leadership, management, and governance of organizational activities aimed at human learning (James et al., Citation2020; Uljens, Citation2023b). For a principal, this includes, for example, financial, political, infrastructural, and pedagogical dimensions. Pedagogical leadership describes the activities a leader, a teacher or a group intend to influence someone else’s learning (Uljens & Ylimaki, Citation2017). Curriculum leadership is connected explicitly to schooling since it covers aims, contents, and teaching methods relating to the curriculum as intended, practised, and experienced.

Previous research indicates that curriculum leadership relates to social processes between leaders and followers (Glatthorn et al., Citation2018; Shan & Chen, Citation2022). A curriculum leader can be a teacher, a principal, or a superintendent. Consequently, curriculum leadership is separate from a formal position or person and can emanate anywhere. Such a perspective acknowledges a multiperspectival point of view, recognizing the ambitions and motivations of all actors involved in the activity (Spinuzzi, Citation2015). In this sense, curriculum leadership consists of multiple people working to ensure the curriculum is vertically and horizontally aligned (Glatthorn et al., Citation2018).

Curriculum leadership is contextually bound and not something a principal can transfer mechanically from school to school (Alava et al., Citation2012). A successful leader in one school might be less impactful in another. This view on curriculum leadership suggests an interest in interconnected leadership processes in specific contexts rather than a narrow focus on individual activities performed by school principals alone (cf. Alvesson, Citation2019). Furthermore, curriculum leadership is related to managing and reflecting on administrative, instructional, sociocultural, and political aspects of educational content—in other words—what is taught, why it is taught, to whom and by whom (Ylimaki, Citation2012). Thus, curriculum leaders need contextual awareness about what, who is being led, and on which level (Norman & Gurr, Citation2020). In this sense, curriculum leadership is not only concerned with teaching and evaluating school subjects, but it also may involve implementing new school systems or new ways of teaching (DeMatthews, Citation2014).

In this study, we argue that curriculum leadership is not an isolated activity in a closed school system. Instead, it is contextually interconnected and open to many variables (infrastructure, interpersonal relations, curricula, pedagogy, finances) (Shaked & Schechter, Citation2017). We agree with Tian and Risku (Citation2019) that although curriculum reforms incorporate leadership elements, few studies connect these two kinds of research. NAT explains the multi-layered nature of curriculum leadership and the dynamics within and between different levels (Uljens, Citation2023a). In other words, NAT explains the pedagogical qualities of curriculum leadership, something we address in the following sections.

Curriculum leadership as processual and multi-level mediation

We understand principals’ curriculum leadership as a processual and multi-level phenomenon, including actors from different educational levels (DeMatthews, Citation2014; Glatthorn et al., Citation2018; Shan & Chen, Citation2022). We draw upon the non-affirmative theory of education (NAT) to explore the mediation of principals’ curriculum leadership. According to NAT, curriculum leadership mediates between epistemic practices and values. Epistemic practices refer to a principal’s knowledge of teaching practice, infrastructure, demography, and financial and judicial systems. Values refer to how principals relate to and reflect on ethics and politics, discussing what education is or what it could be (Benner, Citation2023). For example, cross-curricular teaching means principals must organize their schools according to demands from transnational and national stakeholders, faculty members, and pupils’ needs while considering how the school can contribute to pupils’ subject knowledge, personal development (e.g. Bildung) and democratic skills (Mård & Hilli, Citation2023).

Curriculum leaders discern curricular directives and political motivations without an obligation to endorse them unequivocally. They are encouraged to reflect critically and propose alternative perspectives for comprehending and engaging with these directives, such as curricular guidelines about cross-curricular teaching and political incentives regarding teacher work agreements. However, non-affirmativity is not a binary concept, an all-or-nothing proposition, or an end in itself (Benner, Citation2023). The overarching objective is not to scrutinize every facet exhaustively, as such an approach would prove excessive. Instead, the aim is to invite others to debate what should be preserved or changed (Benner, Citation2023), mediating between affirmative and non-affirmative positions. However, this is not always an easy task. In complex organizations, such as a school, there are always moments of uncertainty, where the only option is to rely on feelings and instinct, often improvising around the problems being presented instead of acting on theory-based knowledge (Raelin, Citation2016).

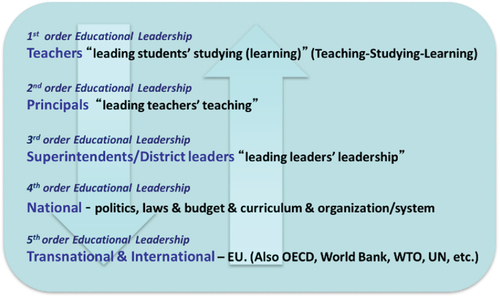

From a non-affirmative perspective, curriculum work is conducted on several educational levels and in different ways to prepare children to become active, responsible, and participatory members of society. Thus, NAT is concerned with the societal aims of education and the political steering mechanisms that influence the school’s work. Curriculum reform is one way for principals to transform societal and political interests into pedagogical practice at the school level. We follow the multi-level perspective suggested by NAT, where educational leadership in schools and society can be divided into five levels (see ): classroom, school, municipality, national and transnational. In this study, we focus on the role of principals as mediators in this multi-level network. Please see Benner (Citation2015); Benner (Citation2023) and Uljens (Citation2023a) for an extended discussion on NAT.

Figure 1. A multi-level and processual perspective on curriculum leadership (Uljens, Citation2018).

One way to explain NAT is to apply it to a Finnish context. In Finland, the curriculum reform process is not conducted top-down on a national level, nor are teachers seen as passive followers (cf. Alvesson, Citation2019). Instead, teachers are trusted and active co-creators in developing the curriculum and the activities in the school (Lonka et al., Citation2018; Rönn-Liljenfeldt et al., Citation2023). The reform processes aim to make every stakeholder a curriculum expert and co-creator to build a stronger sense of commitment, ownership, and sense-making (Lähdemäki, Citation2018; Salonen-Hakomäki & Soini, Citation2023). Shared sense-making in curriculum work attempts to bridge the gap between new and old understandings across all levels of the education system (Pietarinen et al., Citation2017). The Finnish curriculum reform process generally takes several years and includes comments from individuals and organizations. About 30 work groups participated in the latest curriculum reform process for basic education (Lähdemäki, Citation2018; Säily et al., Citation2021).

Several local actors take part in transforming the national guidelines into pedagogical practice in schools, among other associations and interest groups. For a curriculum reform to be successful, most teachers, students and parents need to accept the reform idea (Braskén et al., Citation2020; Byrne & Prendergast, Citation2020). The municipality is responsible for creating a local curriculum in collaboration with school actors. Local educational leaders (e.g. principals and superintendents) know that a curriculum reform’s success largely depends on the teachers’ inclination to adopt new ideas (Lonka et al., Citation2018; Pietarinen et al., Citation2017). Reforms must also consider the school as a historical, political, cultural, and social institution (Simola, Citation2015), meaning that the reforms must fit into the existing institutional practices and traditions. Subsequently, the contexts of schools are essential to address in any curriculum reform.

Curriculum leadership as pedagogical interventions

NAT views curriculum leadership as a pedagogical intervention that intends to challenge someone else’s understanding and builds on the assumption that individuals are self-active and constantly interacting with the surrounding world. In these interactions, individuals may challenge their understanding of themselves and others (i.e. learn) (Benner, Citation2023). Through a pedagogical intervention, a leader can invite or provoke a learner to direct their attention in a specific direction to engage the learner in a self-active learning process. The definition also aligns with curriculum leadership’s dynamic nature, as anyone can invite or provoke someone else to a self-active process of learning (Crevani, Citation2018; Evans, Citation2022). One example is the curriculum challenging the status quo by introducing a new teaching practice, such as cross-curricular teaching. It can be understood as a provocation that might invite practitioners to a self-active learning process and understand their role and teaching in a new light.

NAT uses the concept of summons to self-activity to explain how learning may become a result of pedagogical interventions within the interplay between the context, the summons, and the interpretations of the summoned (Elo & Uljens, Citation2022). In short, leaders do not do curriculum leadership to followers (Evans, Citation2022). Instead, curriculum leadership invites someone to reflect on the curriculum in a particular context to understand it differently. Thus, curriculum leadership is both an intersubjective and subjective process. Intersubjective because a leader summons someone to a self-active learning process. Subjective because the other is invited to be self-active. It recognizes the other as an undetermined subject, free and actively relating to the world, with the capability to transcend one’s current understanding of the world and learn new things (Benner, Citation2023). NAT builds on hermeneutic and reflective approaches in education, echoing the methodology of hermeneutics in this study. In the following sections, we discuss contextual and methodological matters further.

Method – contextual information

The six participating principals worked in Swedish-Finnish lower secondary schools in Finland. One reason for choosing lower secondary schools is the difference between subject and class teachers. Teachers in grades 1–6 are generalists and usually teach an array of subjects, while subject teachers in lower secondary typically teach one or a few subjects (Niemelä & Tirri, Citation2018). Furthermore, subject teachers have a master’s degree in their subject (e.g. history) and a major (60 ECTS3) in pedagogy, while class teachers have a master’s degree (300 ECTS) in pedagogy.

The Finnish national curriculum states that cross-curricular teaching means the pupils can focus on a phenomenon or theme for a more extended period:

In order to safeguard every pupil’s possibility of examining wholes and engaging in exploratory work that is of interest to the pupils, the education provider shall ensure that the pupils’ studies include at least one multidisciplinary learning module every school year. The duration of the modules must be long enough to give the pupils time to focus on the contents of the module and to work in a goal-oriented and versatile manner.

The curriculum gives examples of cross-curricular activities, from functional activities (theme days, study visits and school camps) to holistic approaches. In other words, cross-curricular teaching is mandatory but viewed as a continuum ranging from isolated activities to fully embedded and integrated teaching modules. Since the curriculum does not stipulate how to implement cross-curricular teaching, it is up to the municipality and schools to negotiate how to organize it within the given frames. To implement cross-curricular teaching, ‘cooperation is required between subjects representing different approaches’ (Finnish National Agency of Education, Citation2014, p. 60). We have provided contextual information about the participants, including the cross-curricular projects in their schools, in .

A critical hermeneutic approach

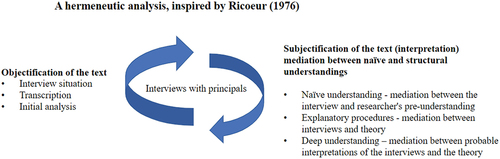

The study employed hermeneutics as a qualitative and interpretative approach to analyse the interviews, embracing the ontological, epistemological, and methodological dimensions that capture being in the world as a human, constantly interpreting new understandings about past experiences (cf. NAT; Porter & Robinson, Citation2011). Hermeneutics aims for a profound understanding by iteratively and abductively moving between empirical material and theories to attain a deep, trustworthy comprehension, expanding the horizon of understanding. Drawing from critical hermeneutics by Paul Ricoeur (Citation1976), the study unravels the complexities of human experience, viewing language as the conduit for articulating being-in-the-world. Ricoeur suggests that while experience is subjective, meaning becomes public through communication, although interpretations may differ. Mediation is a dialectical process between naïve, explanatory procedures and deep understanding and comprehension (Ricoeur, Citation1976), progressing from an open interpretation of texts to structured understanding informed by emerging themes and theoretical frameworks. When analysing the interviews, our naïve understanding was formed by what the principals said about leading cross-curricular work. They explained their experiences differently, such as organizational matters (scheduling, resources) and teachers’ professional attitudes (i.e. didactical positions). These explanations provided probable interpretations during the structural analysis of the whole interview. Thus, we were not concerned with what the authors meant but rather what the entire text opened regarding curriculum leadership (Ricoeur, Citation1976).

However, using hermeneutics in empirical research poses challenges due to the absence of a prescribed methodology, as scholars often navigate between data and theories to grasp human experiences within specific contexts (Claesson et al., Citation2011). Ricoeur did not address empirical materials such as interviews that the interviewer prepares, steers, and transcribes and where the content is co-created with the participants. Claesson et al. (Citation2011) suggest that for researchers to become open to the text in a Ricoeurian sense means being humble and respectful towards the different meanings of the text so a study can offer new understandings of a phenomenon. The aim is not to reach an objective explanation but to try to understand the phenomenon in a broader sociocultural context and to give the participants a voice, which requires an open and judgement-free approach. The researchers are interpreters throughout the study, not merely during the analysis. All stages of the research process (choosing a scope, preparing and conducting interviews, transcribing, translating, and analysing) contribute to the study’s interpretations, implications, and trustworthiness. In other words, we reflected on how the interviewer, the participant, and their answers affected the interviews and our interpretation of the transcribed texts.

The trustworthiness of a qualitative study relies on the researchers providing enough information about the design and context of the study, including ethical considerations and the analysis done so readers can understand the implications and limitations of the study (Lincoln et al., Citation2011). The authors’ theoretical understanding (NAT) and contextual information about the study (Finland) are included in the paper to make the analysis transparent and trustworthy. The findings include quotes from the interviews to confirm the analysis further. Below, we explain how the authors analysed the data.

Mediation as an analytical approach

We have visualized our interpretive process in and , building on Ricoeur’s (Citation1976) approach to mediation. We first tried to distance ourselves from the text by objectifying it by transcribing oral speech to written texts and performing an initial analysis of the interviews. We then approached the interviews again subjectively to establish naïve and structural understandings of them where we considered probable interpretations of the principals’ mediation between affirmation and non-affirmation. While Ricoeur refers to the hermeneutic circle, our visualization (see ) suggests that new interpretations move in spiral-like movements, opening different meanings in the interviews and new understandings of curriculum leadership.

Figure 2. A visualisation of the hermeneutic analysis, inspired by Ricoeur (Citation1976).

Table 2. Examples of the naïve and deep analysis regarding the principal’s mediation between and within classroom and school levels and the theoretical input.

The principals shared negative and positive experiences, indicating that not only principals in favour of cross-curricular teaching participated and that conflicts were connected to the curriculum reform, further confirming a critical hermeneutic approach. Mediation is helpful in hermeneutical research because it is not a technical aspect per se but requires continuously discerning experiences and weighing actors’ different interests and ambitions (Mielityinen-Pachmann & Uljens, Citation2023).

The interviews were semi-structured (Cohen et al., Citation2017) and based on themes relating to multi-level curriculum leadership (see Appendix 1). Author 1 conducted the interviews onsite or online via Zoom during the spring of 2023 and transcribed the interviews verbatim. Twenty-five principals in Swedish-Finnish Lower Secondary Schools were invited to participate; six agreed (for more information on participants, see ). Author 1 did a pilot interview to test the interview guide. The interviews were 45–70 minutes long.

Both authors performed the analysis in shared documents, and as a quality criterion, the authors discussed the relevant meanings continually, trying to reach an intersubjective agreement (Lincoln et al., Citation2011). We also presented the analysis at different stages to other researchers to focus it further. below shows an example of the analytical process.

Ethical considerations

The study followed the ethical guidelines provided by the Finnish National Board on Research Integrity (Citation2019). All participants signed an informed consent agreement before the interviews. Author 1 also informed them during the interviews of their rights to withdraw from the project and the ethical considerations regarding the research materials. The interviews were recorded on a safe server of the university, and during transcription, all identifiers were removed. When presenting the schools, we refrain from specific details about the school, municipalities, and cross-curricular projects to avoid identification. Only author 1 had access to all information about the participants.

Findings

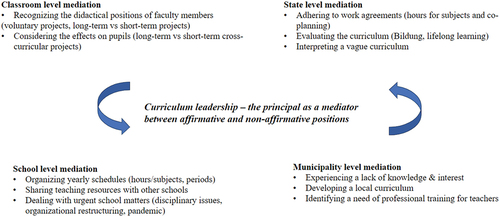

In this section, we discuss the findings of the study. During the naïve analysis, we identified principals’ multi-level mediation regarding curriculum leadership at classroom, school, municipality, and state levels. The structural analysis focused on curriculum leadership within and between these levels and different tensions relating to the complex realities of the principals. In , we have visualized the mediating and interconnected processes identified in the analysis. The figure is not a hierarchical construct; it is hermeneutic and thus non-linear. It shows the principals’ mediation between and within the educational levels, mediating between affirmative and non-affirmative positions. We present the two-level analysis and provide excerpts from the interviews to give voice to the participants.

As curriculum leaders in the school, the principals mediated between the needs of the teachers and pupils on the classroom level. Some principals identified with the subject teachers’ didactical positions and often chose to refrain from affirming the extensive cross-curricular suggestions in the curriculum. Others affirmed the curriculum demands by highlighting the potential benefits of cross-curricular teaching for pupils, and these principals usually created long-term opportunities for teacher cross-curricular collaboration. On the school level, principals mediated between previous epistemic practices (organizing school resources, schedules) and values (urgent matters); some, but not all, created opportunities for cross-curricular teaching in the faculty. The principals in the urban schools had a more manageable task in implementing school-wide cross-curricular teaching, probably because they did not share the teaching resources with other schools.

Moreover, the lack of mediation between schools and municipalities was largely evident in the interviews, resulting in a significant deficit of professional training on cross-curricular teaching for faculty members. This absence of collaboration creates an intriguing conflict, particularly for principals with limited interactions with superintendents (see ). Despite recognizing the potential benefits of more professional training for cross-curricular teaching, the principals were often uncertain about who should take the initiative—the principal or the superintendent. The ambiguity is exacerbated by the vague formulations in the curriculum regarding cross-curricular teaching, leaving schools without clear examples of implementation. Thus, there is a need for non-affirmative discussions to cultivate new epistemic practices within the local curriculum.

On the state level, cross-curricular teaching should integrate several subjects into longer sequences (Finnish National Agency of Education, Citation2014). However, work agreements stipulated three hours for co-planning per week and school subjects were allocated between 18–24 hours per week and a maximum of 500 hours of teaching per year according to the Finnish Teacher’s Work Agreement (2022–2025)4, leading to issues with scheduling at the school level. The work agreements were guidelines that the principals had to affirm. However, some principals created conditions for cross-curricular teaching, suggesting they mediated non-affirmatively between the national and school levels, challenging the epistemic practices (teaching practices, work agreements, scheduling, curriculum) and values (school culture, teacher autonomy) at hand.

Classroom level mediation

The principals mediated between the demands of the curriculum and the didactical positions among faculty members. To the principals, subject teachers identified with their subject and were proud to be experts in a specific subject. All principals felt that the didactical positions might complicate cross-curricular initiatives if teachers must plan, teach, and evaluate something other than their subject(s). As many principals held teaching roles, they often emphasized the subject didactic perspectives of teachers rather than challenging them in their capacity as curriculum leaders within the school. For instance, they may have overlooked opportunities to develop evaluating methods for cross-curricular teaching. This dynamic illustrates the mediation between epistemic practices, such as cross-curricular teaching, and deeply ingrained values, such as teachers’ didactical positions.

We should remember that these are subject teachers who all think their subject is the most important. I still think the subjects I teach are the most important, and nothing should interfere with that.

Most principals sympathized with the teachers, understanding the importance of teaching one’s subject. Often, it made the principals reluctant to push for more cross-curricular teaching because it would lead to a shortened amount of time spent on the subject. Thus, these principals did not affirm the national curriculum guidelines. In these cases, cross-curricular teaching was disregarded or limited to a few theme days.

The main thing is that teachers see a connection between these [cross-curricular teaching and their subject teaching, authors comment]. If a teacher says that they will talk about interest and a math teacher says that we are also doing interest now. That is an automatic collaboration, without teachers changing their whole lesson plan to have a cross-curricular approach.

The structural analysis identified the principal’s mediation within the classroom level, between faculty and pupil positions. Tensions occurred when many teachers preferred to organize short-term rather than long-term cross-curricular activities. Similarly, most principals identified challenges with intense projects that spanned over a few days or weeks because they proved too demanding for the pupils. The principals’ evaluation follows the suggestions in the national curriculum that the pupils should be allowed enough time to focus on cross-curricular topics (Finnish National Agency of Education, Citation2014, pp. 58–59). However, many principals also concluded that there was insufficient time, resources, and, in some cases, interest.

Curriculum leadership meant that the principals evaluated the effects of cross-curricular teaching on the pupils’ learning, making them envision but not necessarily providing conditions for long-term classroom projects. In most cases, a lack of time, resources or planning made the principals opt for short-term projects affirming the subject teacher’s position rather than the pupils. This illustrates how principals’ values influence the implementation of new epistemic practices (i.e. cross-curricular teaching).

School level mediation

The principals in rural schools struggled to plan schedules that supported cross-curricular teaching due to the school context. In the smaller and rural schools (see ), teachers often taught at different school levels, either in grades 1 to 6 or upper secondary school. The schools’ schedules were usually divided into periods offering certain subjects, making it even more complicated to provide schedules that opened for teacher collaboration and cross-curricular teaching. In these schools, curriculum leadership entailed collaboration regarding teaching resources, suggesting mediation between several schools and the municipal level.

They [The teachers, authors comment] started by trying to solve the problem of co-planning time for the teachers. We realised it was not that easy to combine different subject matters. We have three periods when we work with cross-curricular teaching and assess the pupils’ work. It meant that teachers had to sit down and think together about it, which is not always easy. It does require a mindful school leader who specifies how you want teachers to work. You need to be present during the start-up phase so you do not run out of steam and return to how it was before, teaching behind closed doors and not communicating about your work.

Principal’s curriculum leadership meant mediating within the school context regarding schedules and structures that might create opportunities for cross-curricular planning and teaching. Principals 2, 4 and 6 worked in schools where cross-curricular approaches had become part of the school culture with time. They supported previous initiatives at their schools and created new ones by adapting schedules and providing structures for cross-curricular teaching. Principal 2 provided information to pupils about the cross-curricular school project, reduced administrative tasks for teachers and evaluated the cross-curricular efforts in the school. Principal 2 had initiated new ways to organize the efforts (e.g. a cross-curricular steering group) to keep a dialogue with the teachers involved and develop the project according to the teachers’ workload. The teachers in this school seemed to manage one hour of planning per week, perhaps since the cross-curricular project had been running for several years and many structures were already in place.

Similarly, Principal 4 initiated a school-based cross-curricular project spanning several years. It involved guest lectures, a collaboration between subjects and field trips to other schools with similar long-term projects. The project’s first year was mainly about creating drafts with the faculty and allowing the teachers time to adapt to the project. Principal 4 described the process as successful, and teachers and pupils liked the project. However, after the pandemic, they had challenges starting new long-term projects mainly due to concurrent difficulties within the school, which consumed considerable time and resources, highlighting the precarious nature of cross-curricular teaching.

For Principal 6, the yearly plan for the school was a way to envision and ground new initiatives within and between several educational levels (school, municipality). All six principals agreed that initiatives for cross-curricular teaching could emanate from anywhere in the faculty, often from the teachers or the principals, but sometimes from projects in the municipality or societal changes.

As a principal, you plan the yearly schedule with the teachers. It is a draft that the faculty comments discuss and can change. Then, we agree and present it to the superintendent, who can suggest changes. It is also ratified on the municipality level and active for a year, like a joint document or plan. It is a co-planning between the faculty and the municipality. Development work can be teachers who take the initiative, or I, as a principal, can make suggestions. Society is in constant development, so there are always new cultural programs and new events that you may want to get involved in.

Tensions regarding curriculum leadership arose when the principals faced urgent school matters, such as disciplinary issues among pupils, COVID-19-related issues or moving to new school buildings. These urgent issues seemed to overshadow attempts at cross-curricular teaching, and many principals concluded that they did not have the time or the energy for new projects. Although the principals acknowledged the importance of cross-curricular teaching, urgent matters often took centre stage, halting or hindering cross-curricular activities, further confirming that cross-curricular teaching may need long-term planning and structures over several years.

We recently moved to a new school, so cross-curricular teaching has been on hold because of moving, technical issues, etc. Cross-curricular projects are going on, but fewer than before. A lot of thinking and energy has gone into building the new school. We have a spring planning day to discuss how to start more cross-curricular collaboration. The teachers and I feel it has been too little lately, and everyone is too occupied with their subject to start.

The structural analysis confirmed that curriculum leadership was a processual phenomenon involving various stakeholders, such as teachers, principals, and municipal projects. Principals 3, 4 and 5 explained the lack of long-term cross-curricular projects with other issues within the school (disciplinary issues, construction of a new school), limiting cross-curricular teaching to a few theme days. Principals can affirm cross-curricular teaching as curriculum leaders by creating schedules conducive to such teaching practices. However, when other pressing issues also required teachers’ energy and effort, the principals hesitated to increase teachers’ workload and postponed cross-curricular teaching. This hesitation underscores the principals’ role in mediating between established and emerging epistemic practices and values, including the ethical dimension of education.

The mediating role is particularly evident in Finnish schools because principals are not sanctioned for not adhering to the curriculum. Consequently, principals can decide to which extent cross-curricular teaching is affirmed, leading to variability in its implementation across schools. Often, the cross-curricular activities were not enough to allow students to work with a theme in a ‘long-term and versatile manner’ (Finnish National Agency of Education, Citation2014, p. 59). The autonomy of local providers opened for contextual relevance, meaning that current projects or visions in the municipality positively inspired cross-curricular activities in some schools.

Municipality level mediation

Mediation between school and municipality levels were usually lacking or limited. The superintendents in the municipality were often portrayed as passive or absent. Some principals felt it was positive since the school could develop whatever projects they felt were relevant to pupils rather than getting top-down suggestions from the municipality. However, Principal 5 questioned the lack of interest.

I chair the Swedish section [for education in the municipality, authors’ comment], and I would appreciate more questions from the others. We decided on teaching resources for the school some months ago, and there were no questions: A) How did you decide on the numbers for each school? B) Are the resources enough? C) What about special needs education? Are there resources for that? It was decided without discussion. I would expect more interest if you ran for a position in the section. The collaboration and communication work, but more curiosity in the school’s work would not hurt.

The structural analysis suggested that the autonomy and level of trust in the principals and teachers might be one reason for the lack of dialogue between principals and superintendents in some municipalities. While the relationship is based on trust in practitioners, some principals also preferred to keep the projects within the school without input from the municipality. Unless the superintendent knew the projects, some principals questioned how constructive their feedback could be suggesting that a trusting dialogue between educational levels build on knowledge about the local epistemic practices.

I am glad we get the time to work in our way. Someone who comes from the outside might not have time to get acquainted with our project and might come with input that might make us lose momentum.

Principals 2 and 4 explained that the superintendents in the municipality knew about the local curriculum and cross-curricular teaching the schools had developed. Still, the superintendents did not want to intervene or question the school’s epistemic practices. The curriculum leadership in most municipalities became one-sided since most superintendents remained passive or trusting, neither challenging nor supporting principals to develop cross-curricular teaching.

Principal 6 experienced a different situation where all the school principals in the municipality and the superintendent continuously discussed school-related matters. The trust between the principal and the superintendent seemed mutual and supportive of the curriculum leadership. Due to the close collaboration at the school and municipal levels, they were able to develop joint visions regarding children and youth for the region. These visions became cornerstones for the school’s cross-curricular projects.

We have a very active and profound dialogue, and the principals [in the municipality, authors’ comment] meet once a month. We have contact with the educational department, office, and superintendent almost daily – close collaboration and dialogue. I think it is great support for the principal. You are the only principal at the school, so you are alone. We have a school campus with the upper secondary school, and we stay in touch and have a collegial dialogue. Nevertheless, it is essential to have the municipality as a foundational support. It works well.

The inadequate mediation between the school and municipality levels created tensions because professional training was seldom arranged for the faculty members. The principals generally assumed that professional training was absent due to a lack of knowledge about cross-curricular teaching on the municipality level. However, the principals did not initiate dialogues on professional training with the educational leaders in the municipality either, thereby contributing to the lack of dialogues between the school and municipality levels.

Our city has enough funding for cross-curricular teaching, so the conditions are favourable. However, basic knowledge is sometimes lacking, and I think we could do better with professional training because many teachers have excellent ideas.

Joint professional training on cross-curricular teaching could facilitate the development of shared visions between the school and the municipality. Principals acknowledged varying opinions among faculty members regarding cross-curricular teaching. Some teachers were positive about cross-curricular teaching, while others were hesitant or negative; the eager teachers were often involved in the projects. Principal’s curriculum leadership meant considering epistemic factors such as funding and values such as shared knowledge to conduct cross-curricular activities successfully.

During my four to five years here, we have not had any professional training [in cross-curricular teaching, authors’ comment]. I think we start from the point that everyone knows what cross-curricular teaching is, and I do think everybody knows, but I do not think everyone knows how to do it well. (Principal 4)

The absence of shared cross-curricular visions within the schools contributed to ambiguity regarding curricular aims in pedagogical practice. The structural analysis indicated that most principals sought dialogues with superintendents to support new practices in the school. Negotiating the goals and methods of cross-curricular teaching proved challenging. These findings also highlight the varying preferences among principals, with some prioritizing collaboration with the municipality while others favoured internal school initiatives. Instead of mandating collaboration, many principals adopted a non-affirmative approach by encouraging teachers to share successful cross-curricular teaching examples, inviting others to experiment with them and introducing new educational practices.

State level mediation

The principals mediated between state-level work agreements when planning the yearly schedule and cross-curricular teacher collaboration on the school level. The national curriculum and collective agreements at the state level stipulated how many hours per week different subjects were to be taught, which hindered cross-curricular teaching initiatives. All principals, apart from principal 2, explicitly expressed that a work agreement based on full-time (40-hour week) or clauses in current agreements (e.g. one hour a day for planning) would support the principals’ work because it would provide more planning and collaborative activities. The structural analysis suggests that curriculum leadership requires principals to organize new structures on the school level for teachers’ co-planning, for example, by considering long-term collaboration and co-planning over several years.

Nonetheless, the existing work agreements forced most principals to affirm rather than challenge previous epistemic practices. Changing the collective agreements is a long-winding affair that calls for state and municipality-level actors and teacher unions to negotiate. It illustrates the limitation of principals’ leadership because work agreements are not within their direct sphere of influence.

If you had a whole workday, it would be easier to plan for teacher collaboration between one to two hours. That would provide different tools to work with cross-curricular teaching. We have co-planning [three hours/week, authors’ comments], which is too little. As a teacher, you have your schedule and work agreement, meaning some days you stop working at 12.00 and your colleague stops working at 14.00, and it is hardly reasonable to ask teachers to wait two hours at the school. However, this is how the Finnish school works. We have the work agreement and co-planning time, and we must work with that.

Principal’s curriculum leadership meant mediation between work agreements and evaluating curriculum-related goals for pupils. Cross-curricular projects were often related to general goals (e.g. Bildung, lifelong learning) rather than subject-specific ones and supported pupils’ interests (Finnish National Agency of Education, Citation2014). Curriculum leadership can benefit from building a foundation for cross-curricular teaching on Bildung and supporting every student to reach their potential.

The vision for this school is to open the minds of all pupils. We must consider lifelong learning; lower secondary school provides a foundation for that. Moreover, lift the topic of Bildung into the discussion. It is not merely much knowledge to be fed to pupils. Bildung means the pupils realise their potential and become their best version. We are a big school, but we try to meet every pupil as far as possible.

Principals 1, 3 and 4 experienced the current curriculum as vague about cross-curricular teaching, which created tensions for their curriculum leadership. The principals found it easier to implement something if it was explicitly written in the curriculum. Otherwise, teachers may object to extracurricular activities because their work agreements do not require them to work beyond certain weekly hours. An organization built on vague directions in the curriculum was challenging to change. However, the national curriculum offers examples of cross-curricular activities, allowing local authorities to apply them suitably. The analysis submits that the vagueness perceived by many principals is perhaps due to their difficulties in shouldering a curriculum leadership role where they non-affirmatively negotiated the curriculum with the faculty and created conditions for new epistemic teaching practices. While all principals enjoyed running the school as they saw fit, the teachers’ autonomy and reluctance to participate in unclear cross-curricular activities sometimes challenged the principals’ curriculum leadership.

For us to implement anything, it must be written clearly in the curriculum. It becomes easier if we can refer to what the curriculum demands.

The structural analysis suggests that curriculum leadership requires principals to mediate between state-level requirements and their practical effects on the school level. It also portrays the limitations of principals’ curriculum leadership, as it can be challenging to implement curricular guidelines due to ideas created on national and transnational levels. The general goals in the curriculum supported the schools’ cross-curricular initiatives from the pupil’s learning perspective. However, epistemic practices (i.e. teachers’ work agreements, scheduling) and values (teacher autonomy, school culture) made it difficult for the principals to involve the faculty in cross-curricular teaching due to issues with subject-based schedules and co-planning time.

Discussion

This study explored principals’ experiences of curriculum leadership as a mediating activity when implementing cross-curricular teaching. The study confirms that the principals moved between affirmative and non-affirmative positions while considering epistemic practices (work agreements, scheduling, curriculum, teaching practices) and values (teacher autonomy, didactical positions, urgent matters, school culture) (cf. Benner, Citation2023). The study also confirms that curriculum leadership is a processual phenomenon at several educational levels, with other actors (teachers and superintendents) exercising it, too (cf. Glatthorn et al., Citation2018). The study adds to previous research by highlighting that a principal’s curriculum leadership means mediation between national policies, planning education on a municipal level, and the practical work in the school when implementing cross-curricular teaching.

Cross-curricular teaching is not only a different way of teaching compared to subject-centred teaching. This study indicates that non-affirmative negotiations within the faculty and new ways to organize, plan, teach and assess education are needed (cf. Lysberg, Citation2022). Finland’s decentralized educational system meant there were few conclusions to be drawn from the contextual specificities within each school because all municipalities organize basic education differently. However, the findings point towards similar complexity and limitations of principals’ curriculum leadership, as it is embedded in individual beliefs, organizational structures, and national policies (cf. Uljens & Ylimaki, Citation2017; Wallace et al., Citation2007). Principals must affirm some epistemic practices, such as work agreements, while others can be scrutinized at the school and municipality levels, such as organizing school schedules and cross-curricular teaching. Moreover, principals’ educational values influence the implementation of cross-curricular teaching, attempting to align the curriculum reform with the existing school culture.

The study points to a lack of coherence between transnational influences and national policies and their effects on the realities of principals’ curriculum leadership. While all principals agreed that cross-curricular activities benefitted pupils’ personal development (e.g. Bildung), the national structures limited the principals to create more collaboration at the school level. The teacher’s work agreements and the Basic Education Act are organizational structures principals must affirm. As a solution, most principals opted for non-affirmative models that gave teachers more opportunities to collaborate without transforming the school organization (Glatthorn et al., Citation2018). If the national aim is to work towards a collaborative and cross-curricular school culture, we argue that work agreements must align with the curriculum’s vision and aims (cf. Mård & Hilli, Citation2023). Otherwise, principals may be left with the challenging task of leading the school towards a more collaborative school culture with a limited mandate (cf. Mård & Hilli, Citation2022).

The findings indicate the importance of negotiating curriculum leadership at the school and municipality levels. Principals in smaller schools, often located in rural areas, that share teaching resources with other schools may face additional challenges in scheduling co-planning time (cf. Karlberg-Granlund, Citation2023). In such circumstances, the efforts of one principal are not enough; instead, curriculum leadership requires conscious and collective efforts on multiple levels, for example, shared cross-curricular aims for all schools in the municipality (DeMatthews, Citation2014; Glatthorn et al., Citation2018). The principals in this study rarely initiated dialogues with the superintendents or problematized the municipality’s current structures (e.g. a lack of professional training and a jointly written local curriculum). Better organizational models for cross-curricular teaching in the municipality can be developed by involving other actors, such as the superintendents. Previous research confirms that school development improves student achievement by creating successful and trusting multi-level collaboration between school and municipality levels (Uljens et al., Citation2016). Further, this study points to the importance of knowledge on the municipality level about the epistemic practices (e.g. cross-curricular teaching, local curriculum) in the schools.

On the school level, the teachers’ didactical positions (cf. Frederiksen & Beck, Citation2014) influenced principals’ curriculum leadership. Finnish principals are also teachers, which may provide them with first-hand knowledge of cross-curricular teaching and an in-depth understanding of the curriculum (Glatthorn et al., Citation2018; Harris et al., Citation2020). However, we submit that their teaching background might make principals reluctant to challenge teachers’ understanding of cross-curricular teaching because they identify with the subject teachers’ values and preferences for teaching one’s subject. While principals may want to change the epistemic practices in the school and challenge the teachers to see the benefits of more collaboration, they may avoid challenging values that an individualistic school culture builds on, e.g. subject teacher’s autonomy and professionalism (cf. Mård & Hilli, Citation2022).

Despite voicing concerns regarding pupils’ learning after short-term cross-curricular projects, some principals did not intervene to create conditions for long-term projects, providing teachers and pupils enough time for cross-curricular activities. The study confirms that the principal’s involvement in organizing and scheduling cross-curricular teacher collaboration is important (cf. Mård & Hilli, Citation2023). The Finnish curriculum offered general goals related to the pupil’s interest and personal development (e.g. Bildung, lifelong learning) (Finnish National Agency of Education, Citation2014), and some schools found it challenging to assess these goals because they differed from the subject-specific ones. Professional training for teachers and school leaders and non-affirmative faculty discussions might support schools when developing new evaluation practices.

The principals juggled many urgent matters, and in some cases, it left little energy or interest for cross-curricular teaching, implying that long-term visions and structures may ease principals’ implementations of new epistemic practices. The principals generally agreed that cross-curriculum teaching was necessary because the curriculum demanded it and could benefit pupils, thus affirming the curriculum. However, some principals confessed that they knew little about classroom activities or did not have the energy to lead new cross-curricular projects, suggesting a non-affirmative approach to cross-curricular teaching due to too many other matters. Many principals stated that the post-pandemic era had been challenging, and long-term projects require much time and energy to develop. A school is a complex organization, and unexpected events, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, may cause plans of action to be altered and changed, demanding efforts to adapt to new circumstances (Raelin, Citation2016).

Principals’ pedagogical leadership involves providing opportunities for teachers to develop professionally. The vague formulations in the curriculum made it harder for the principals to require teachers to participate in cross-curricular efforts. A few principals created shared visions for cross-curricular teaching, allowing teachers time to acclimate to and develop new teaching practices (Pietarinen et al., Citation2017; Simola, Citation2015). The principals who successfully implemented school-wide cross-curricular activities had also allowed them to develop for several years, making gradual changes as necessary, often through open and non-affirmative discussions with faculty members. Scheduling and professional training were essential for the schools to develop cross-curricular teaching (cf. McPhail, Citation2018). Furthermore, principals need to negotiate aims that can be evaluated on several educational levels, indicating a strategic approach to foster a cross-curricular school culture attuned to the contextual nuances of local needs and conditions (cf. Alava et al., Citation2012; Mård & Hilli, Citation2023; Norman & Gurr, Citation2020). This study suggests that the principals’ curriculum leadership may set school-wide cross-curricular initiatives in motion through new epistemic practices (i.e. scheduling and long-term structures), thus reducing the teachers’ and principals’ workloads and supporting student learning.

Limitations and future studies

The study presents a hermeneutic and, therefore, in-depth but still limited view on curriculum leadership based on interviews with six principals and their perceived experiences, not observed activities or interviews with other actors (teachers, superintendents). Few empirical studies use NAT as a theoretical and analytical framework, and more studies are needed to explore the mediation between affirmation and non-affirmation on different educational levels, preferably using different research methods (Benner, Citation2023). We submit that NAT is a suitable theoretical framework for empirical studies on individual experiences. However, the central concepts (e.g. affirmation, non-affirmation, and mediation) can be challenging to apply to complex collective realities in schools that are affected by many external (e.g. teacher’s work agreements, sharing school resources) and internal (urgent school issues, unexpected events) demands. The study confirms curriculum leadership as a multi-level phenomenon and the importance of understanding education as a system constructed on many levels. Future studies could explore curriculum leadership as a multi-level process in schools and municipalities as cases or development projects to understand cross-curricular teaching in different settings and countries. The collaboration between principals and other actors (e.g. teachers, superintendents, and local and national stakeholders) would also be a relevant topic for future research.

Conclusions and implications

This study confirms that curriculum leadership should be understood in the light of the specific context of education: who is leading, who is being led, what is being led, where it is being led, and how it is being led. School leaders, superintendents, and teachers must create visions for the school and align other curricular aims with such a vision. Cross-curricular teaching benefits from long-term initiatives, allowing different forms of collaboration between schools and local and regional actors.

The study was set in a Finnish context, meaning the curriculum is decentralized, building on trust in practitioners as curricular experts. New reforms are encouraged through soft governance, not top-down demands. The vaguely formulated curricular guidelines resulted in variance in how schools interpreted cross-curricular teaching. Some schools had a year-round, holistic approach to cross-curricular teaching, while others had occasional theme days or short and intense projects. Many principals struggled to shoulder the role of a curriculum leader given the professional autonomy of the teachers, lack of support from the superintendents, the vague curriculum, and teachers’ subject-based work agreements. Thus, while principals’ curriculum leadership is a central component for cross-curricular teaching, it is only one part of a multi-level phenomenon influenced by individual beliefs, organizational structures, institutional norms, and policies. By viewing leadership as a collective phenomenon affected by structures and culture, changing a school culture rests on both leaders and the educational collective. Such a view can also alleviate the pressure on the individual leader, further underscoring the importance of understanding curriculum leadership as a mediating activity.

We submit that cross-curricular teaching brings dialogues between different educational levels to the fore, from the teachers and pupils in the classroom to principals in schools and superintendents in the municipalities to national and transnational curriculum stakeholders. The principal’s role means complex mediation between affirmation and non-affirmation while considering the local context, national policies, and transnational influences.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank those who provided valuable feedback on the text. Special thanks are due to the reviewers, as well as to Alexia Buono, Sofia Jusslin, Maria Rönn-Liljenfeldt and Mindy Svenlin for their insightful and constructive comments on the draft.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. The demographic composition of Finland includes a Swedish-speaking population, comprising approximately 5% of the total populace. Both Finnish and Swedish hold the status of national languages, and education is available in both languages across various levels of instruction.

2. For an extended discussion on cross-curricular teaching, please see, for example, Frodeman et al. (Citation2017); Klausen and Mård (Citation2023).

References

- Ahtiainen, R., Hanhimäki, E., Leinonen, J., Risku, M., & Smeds-Nylund, A.-S. (2023). Leadership in educational contexts in Finland: Theoretical and empirical perspectives. Springer. Educational Governance Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-37604-7

- Alava, J., Halttunen, L., & Risku, M. (2012). Changing school management: Status review - May 2012. Oppaat ja käsikirjat/Opetushallitus. Finnish National Board of Education.

- Alvesson, M. (2019). Waiting for Godot: Eight major problems in the odd field of leadership studies. Leadership, 15(1), 27–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/1742715017736707

- Benner, D.(2015). Allgemeine Pädagogik. Juventa.

- Benner, D. (2023). On affirmativity and non-affirmativity in the context of theories of education and Bildung. In M. Uljens (Ed.), Non-affirmative theory of education and Bildung (pp. 21–59). Springer.

- Braskén, M., Löfwall Hemmi, K., & Kurtén, B. (2020). Implementing a multidisciplinary curriculum in a Finnish lower secondary school – the perspective of science and mathematics. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 64(6), 852–868. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2019.1623311

- Bush, T., & Glover, D. (2014). School leadership models: What do we know? School Leadership & Management, 34(5), 553–571. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2014.928680

- Byrne, C., & Prendergast, M. (2020). Investigating the concerns of secondary school teachers towards curriculum reform. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 52(2), 286–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2019.1643924

- Chong, P. W., & Graham, L. (2017). Discourses, decisions, designs: Special education policy-making in New South Wales, Scotland, Finland and Malaysia. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 47(4), 598–615. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2016.1262244

- Claesson, S., Hallström, H., Kardemark, W., & Risenfors, S. (2011). Ricœurs kritiska hermeneutik vid empiriska studier [Ricœur’s Critical Hermeneutic in Empirical Studies]. Pedagogisk forskning i Sverige, 16(1), 18–35.

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2017). Research methods in education. Routledge.

- Crevani, L. (2018). Is there leadership in a fluid world? Exploring the ongoing production of direction in organizing. Leadership, 14(1), 83–109. https://doi.org/10.1177/1742715015616667

- DeMatthews, D. E. (2014). How to improve curriculum leadership: Integrating leadership theory and management strategies. The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues & Ideas, 87(5), 192–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/00098655.2014.911141

- Elo, J., & Uljens, M. (2022). Theorising pedagogical dimensions of higher education leadership—a non-affirmative approach. Higher Education, 85(6), 1281–1298. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00890-0

- Evans, L. (2022). Is leadership a myth? A ‘new wave’ critical leadership-focused research agenda for recontouring the landscape of educational leadership. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 50(3), 413–435. https://doi.org/10.1177/17411432211066274

- Finnish National Agency of Education. (2014). National core curriculum for basic education 2014. Opetushallitus.

- Finnish National Board on Research Integrity. (2019). The ethical principles of research with human participants and ethical review in the human sciences in Finland. Tenk Publications. https://www.tenk.fi/en

- Frederiksen, L. F., & Beck, S. (2014). Didactical positions and Teacher collaboration: Teamwork between possibilities and frustrations. Alberta Journal of Educational Research, 59(3), 442–461. https://doi.org/10.11575/ajer.v59i3.55749

- Frodeman, R., Klein, J. T., & Pacheco, R. C. D. S. (Eds.). (2017). The oxford handbook of interdisciplinarity. Oxford University Press.

- Glatthorn, A., Boschee, F., Whitehead, B., & Boschee, B. (2018). Curriculum leadership – strategies for development and innovation. Sage Publications, Inc.

- Gresnigt, R., Taconis, R., Keulen, H., Gravemeijer, K., & Baartman, L. (2014). Promoting science and technology in primary education: A review of integrated curricula. Studies in Science Education, 50(1), 47–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057267.2013.877694

- Gunnulfsen, A. E., Ärlestig, H., & Storgaard, M. (Eds.). (2023). Education and democracy in the Nordic Countries: Making sense of school leadership, policy, and practice. Springer Nature.

- Gunnulfsen, A. E., Jensen, R., & Møller, J. (2022). Looking back and forward: A critical review of the history and future progress of the ISSPP. Journal of Educational Administration, 60(1), 5–20. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEA-04-2021-0088

- Haapaniemi, J., Venäläinen, S., Malin, A., & Palojoki, P. (2021). Teacher autonomy and collaboration as part of integrative teaching – reflections on the curriculum approach in Finland. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 53(4), 546–562. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2020.1759145

- Hargreaves, A. (2019). Teacher collaboration: 30 years of research on its nature, forms, limitations and effects. Teachers & Teaching, 25(5), 603–621. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2019.1639499

- Harris, A., Jones, M., & Crick, T. (2020). Curriculum leadership: A critical contributor to school and system improvement. School Leadership & Management, 40(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2020.1704470

- James, C., Connolly, M., & Hawkins, M. (2020). Reconceptualising and redefining educational leadership practice. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 23(5), 618–635. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2019.1591520

- Karlberg-Granlund, G. (2023). The heart of the small Finnish rural school: Supporting roots and Wings, Solidarity and autonomy. In K. E. Reimer, M. Kaukko, S. Windsor, K. Mahon, & S. Kemmis (Eds.), Living well in a world worth living in for all: Volume 1: Current Practices of Social Justice, sustainability and wellbeing (pp. 47–67). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-7985-9_4

- Klausen, S., & Mård, N. (2023). Speaking and thinking about cross-curricular teaching: Terms, concepts, and conceptions. In S. Klausen & N. Mård (Eds.), Developing a didactic framework across and beyond school subjects: Cross- and trans-curricular teaching (pp. 7–18). Routledge.

- Lähdemäki, J. (2018). Case study: The Finnish national curriculum 2016 – a Co-created national education policy. In J. Cook (Ed.), Sustainability, human well-being, and the future of education (pp. 397–422). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lantela, L., Pietiläinen, V., & Korva, S. (2024). Examining contradictions for the development of competencies in school leadership. In R. Ahtiainen, E. Hanhimäki, J. Leinonen, M. Risku, & A. Smeds-Nylund (Eds.), Leadership in educational contexts in Finland (pp. 257–279). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-37604-7_13

- Lenoir, Y., & Hasni, A. (2016). Interdisciplinarity in primary and secondary school: Issues and perspectives. Creative Education, 7(16), 2433–2458. https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2016.716233

- Lincoln, Y. S., Lynham, S. A., & Guba, E. G. (2011). Paradigmatic controversies, contradictions, and emerging confluences, revisited. The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research, 4(2), 97–128.

- Lonka, K., Makkonen, J., Berg, M., Talvio, M., Maksniemi, E., Kruskopf, M., Lammassaari, H., Hietajärvi, L., & Westling, S. K. (2018). Phenomenal learning from Finland. Edita.

- Lysberg, J. (2022). Unpacking capabilities for professional learning: Teachers’ reflections on processes of collaborative inquiry in situated teamwork. Journal of Workplace Learning, 35(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1108/JWL-01-2022-0008

- Mäkiharju, A., & Smeds-Nylund, A.-S. (2023). Finland: A structure of trust. In A. E. Gunnulfsen, H. Ärlestig, & M. S (Eds.), Education and democracy in the Nordic Countries: Making sense of school leadership, policy, and practice (pp. 29–44). Springer.

- Mård, N., & Hilli, C. (2022). Towards a didactic model for multidisciplinary teaching - a didactic analysis of multidisciplinary cases in Finnish primary schools. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 54(2), 243–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2020.1827044

- Mård, N., & Hilli, C. (2023). Cross-curricular teacher collaboration actualizing teacher professionalism – revisiting a didactic model. In S. Klausen & N. Mård (Eds.), Developing a didactic framework across and beyond school subjects: Cross- and trans-curricular teaching (pp. 47–58). Routledge.

- McPhail, G. (2018). Curriculum integration in the senior secondary school: A case study in a national assessment context. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 50(1), 56–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2017.1386234

- Mielityinen-Pachmann, M., & Uljens, M. (2023). Hermeneutics in the Non-affirmative Theory of Education. In M. Uljens (Ed.), Non-affirmative theory of education and Bildung (pp. 199–214). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-30551-1_9

- Moos, L., Nihlfors, E., & Paulsen, J. M. (2020). Re-centering the Critical Potential of Nordic School Leadership Research. Springer.