ABSTRACT

This paper is an exploratory study of the personal and systematic influences over the curriculum decision-making process of teachers of students with severe or profound and multiple learning difficulties in Australia. The way in which these influences impact teacher perceptions of the mandated curriculum and its day-to-day operationalization are discussed. The paper draws from both a national survey (n = 46) and in-depth case studies (n = 5) of teachers who work in government-funded specialist educational settings. Findings show that teachers have prominent levels of emotionality, a drive for creativity and dedication to inclusive practice, but ultimately work within a context perceived through conflict and dilemma. Previous related decision-making models are used to compare results, with some distinct differences emerging. Findings indicate that rather than enabling inclusion, standardized curriculums create an environment of professional (self)exclusion and reduce access to professional support. Increases in responsibility burden and negative emotional effects are explored. Although teachers view access to standardized curriculum programs as vital to educational inclusion and the enhancement of their professional expertise, the utilization of the current offering in Australia is makeshift at best and fraught with internal conflict. The implications of these findings are discussed, and future recommendations for research are prioritized.

Introduction

Teachers of students with severe or profound and multiple learning difficulties have consistently been shown to work in a professional environment where there is a consistent tension between professional role obligations, student-led learning practices and their own personal value orientations (Brunsting et al., Citation2022; Stewart & Walker-Gleaves, Citation2020). Previous research has shown that teachers who work in specialist educational settings and support students with severe or profound and multiple learning difficulties experience internal conflict in their decision-making and enactment of duties in pedagogy, relationships with school and executive leadership, policy, and the application of evidence-based practices through to curriculum content and structure (Cook et al., Citation2008; Lawson & Jones, Citation2018; Siuty et al., Citation2018; Timberlake, Citation2016).

Australia is a signatory to the United Nations Salamanca Statement, supported by national legislation, The Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (DDA) and The Disability Standards for Education 2005 (DSE) (Australian Government, Citation2022b, Citation2022a). When analysing the impact of these policies, we must consider the experiences of inclusion and exclusion experienced by those students with the most complex needs and their teachers. In 2023, the findings of the Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability (DRC) were released, stating,

Students with disability face multiple barriers to inclusive education, underpinned by negative attitudes and low expectations. Schools systematically exclude students with disability. They do this by not providing appropriate adjustments and supports to enable their participation in classrooms and in the broader school community. In many cases, through gatekeeping, students with disability are channelled into special/segregated schools and classes (Commonwealth of Australia, Citation2023, p. 10).

Students with severe intellectual disabilities or profound and multiple learning difficulties are likely to have a combination of the following characteristics: severe intellectual disabilities, emergent and idiosyncratic communication profiles, non-traditional sensory processing, physical disabilities, complex medical profiles and/or challenging behaviours. These students will need elevated levels of adult and peer support throughout their lives (Colley & Tilbury, Citation2022; Nind & Strnadova, Citation2020). The terminology used to describe these students internationally can often include ‘students with extensive support needs’ or ‘complex learners’. In Australia, most students with severe intellectual disabilities or profound and multiple learning difficulties attend schools for specific purposes (SSPs), which are self-contained, segregated schools that serve the needs of students with similar disabilities exclusively.

In Australia, there is a national curriculum that mandates teachers, on the one hand, use the same standardized curriculum structure to plan, assess and report for all students but, on the other hand, provide a clear recommendation for students with disabilities to be supported through the development of Individual Education Plans (IEPs) (Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority [ACARA], Citation2023). IEPs are formal documents that specify a student’s individual skills development goals, strengths, and interests, and are developed in partnership with parents/guardians, other teachers, and professionals (ACARA, Citation2023). IEPs formally document a student’s development and articulate an agreed educational growth plan for students with disabilities. Teachers are placed at the centre of a negotiation process with a dual responsibility to enact, assess and report the mandated standardized curriculum as well as expected to facilitate the design and implementation of a student’s IEP in a collaborative environment with parents, the student, school peers and school-based and external professionals (Rendoth et al., Citationn.d).

The process of individualized curriculum programming in the context of standardized curriculum structures cultivates an environment where a teacher must navigate multiple opportunities for both professional and personal ethical tensions. These points of tension where conflicting purposes and motivations can be in relationships between teacher-system, teacher-professional, teacher-leadership, teacher-parent, and teacher-student. Although individualized education planning is not a singularly Australian responsibility for teachers, the work of Rendoth et al. (Citation2024), Datta et al. (Citation2019) and Walker et al. (Citation2018) find that there is insufficient support and considerable inflexibility of Australia’s standardized curriculum framework in providing support for teachers to undertake their professional duties of weaving together these often-competing responsibilities.

This study examines the priorities, feelings and motivations of Australian teachers who support students with severe or profound and multiple learning difficulties in specific schooling placements and who are secondary-aged. Seeking to uncover and then compare these experiences to the prior work in this field done internationally, this research explores the professional choice-making and expression, operationalization of professional expectations, and how Australian teachers negotiate this dynamic and complex paradigm.

Ruppar et al. (Citation2015) have proposed a theoretical framework for teacher decision-making regarding literacy curriculum for students with severe disabilities, which was then adopted and modified by Siuty et al. (Citation2018) in investigating the relationships between curriculum and teacher decision-making for students with disabilities more generally within teacher populations in the United States. Both Ruppar et al. (Citation2015) and Siuty et al. (Citation2018) articulate the decision-making process as a formal model reflecting the process of making decisions teachers undertake when making curriculum choices for students with disabilities. These models act as the most contemporary formal expression of teacher decision-making processes for teachers of students with more complex levels of disability. Both models were developed in the United States and reflect the processes and influencing characteristics of choice-making specific to the United States contextual features of the curriculum policy, frameworks, and structures. The present study investigates the experiential contexts of teacher decision-making in Australia and, relates findings to the models proposed by both Ruppar et al. (Citation2015) and Siuty et al. (Citation2018) so to try and articulate the shared commonalities, and differences between teacher experiences internationally.

The choice to focus on the population of teachers working in specialist settings was made as the enrolment profile of these schools is specific to students with severe or profound and multiple learning difficulties. Brunsting et al. (Citation2014) and Jones and Youngs (Citation2012) both elucidate that special education teachers are at higher risk of burnout than their mainstream teaching peers. Brunsting et al. (Citation2022) show that this is an active consideration when understanding a special education teacher’s role pressures and professional life, and therefore decision-making, citing workload manageability and emotional exhaustion as key influences. The work of Blackley et al. (Citation2020) links elevated levels of teacher negative affect during decision-making junctures to increases in cognitive load pressures, lessening reflexive self-development, higher stress rates, and lower self-efficacy rates. Resulting teacher affect reinforces the need to understand the dynamic nature of teacher emotionality and their relationship to decision-making in an environment defined by negotiation between professional role obligations, their support, and their personal value orientations.

By understanding teachers’ personal values and moral perspectives within the context of their professional roles, we can begin to understand the way that they influence a student’s experienced curriculum through how these teachers embody and activate personal and/or professional responsibilities through their choice-making (Derryberry & Thoma, Citation2005; Vink et al., Citation2015). Although Brunsting et al. (Citation2022) specifically focus on teachers who support students with emotional-behavioural disorders in specialist environments, we also reflect on the professional responsibility for individualized curriculum planning, as well as the known ineffective support and inflexible system requirements that Australian special education teachers experience (Datta et al., Citation2019). Prioritising the capturing of these teachers’ experiences and emotional motivations will give insight into how to support them best and the students they teach. The teachers’ personal and professional motivations and priorities are the first step in defining their educational value orientations compared to the professional system requirements and demands and how best to cultivate an environment of professional safety and support.

Methodology

Method

This study constitutes an initial, exploratory, small-scale investigation into the beliefs and practices of teachers who support secondary students with severe or profound and multiple learning difficulties, combining both survey and case study data collection methods (Anderson & Lighfoot, Citation2022). The data collected within this process was intentionally broad to gather information on multiple curriculum decision-making, planning, and implementation aspects of teaching practice. This paper presents a multi-staged, mixed-methods research consisting of a survey and in-depth interviews with volunteer survey respondents. It reports the findings related explicitly to teacher perspectives on identifying and prioritizing areas of need for their students, their self-perception of their role as a teacher, and how this influences their planning and implementation practices. In the context of a broader research study, the data reported herein relates to this question; What are the influences upon teachers’ curriculum-related decision-making when using current national and state-endorsed curricula and supporting documents to support students with severe intellectual disabilities or profound and multiple learning difficulties in specialist education settings?

Participants

Recruitment for survey participants was through email distribution lists from peak organizational bodies, the Australian Special Education Principals Association (ASEPA), the Australian Association of Special Education (AASE) and the Special Education Principals and Leaders Association (SEPLA) as well as other professional networks and social media posting by the researchers. Although over 1600 people initially commenced the survey, only 51 were deemed eligible after responding to screening questions, with 46 eligible participants completing the survey. Screening questions specifically asked participants if they worked in specialist educational settings, and if they had direct responsibility for curriculum planning for students with severe or profound and multiple learning difficulties. Five of the 46 participants went on to become case study participants. The survey had respondents from four states/territories in Australia. Respondents worked in major centres (41.3%), followed by regional areas (32.6%) and state capitals (26.1%). The average teaching experience with students who have severe or profound and multiple learning difficulties was 6.9 years. Respondents had an average of 7.7 students with whom they had primary curriculum planning responsibilities. Almost half of the respondents (45.6%) reported not holding any qualifications in special education, or they were currently studying to obtain a qualification in inclusive and special education. Respondents were recruited through professional peak representative bodies and other professional networks nationally.

Procedures for data collection and analysis

Data collection

As a survey of this kind has yet to be undertaken in Australia, it was first developed by the research team and then in consultation with peak organizational bodies to ensure the survey tool correlated to their members’ contemporary professional and practice contexts. The survey was accessible online from 20 July 2021 until 20 October 2021.

Before completing the survey, respondents were given full disclosure information, and informed consent was obtained. The survey consisted of four main sections aligning with the broader study: a) Demographics and experience; b) Personal and professional identities; c) Curriculum use and d) Professional learning and support. The survey was designed using a mixed methods approach with a mix of open responses, Likert scale, ranking and multiple-choice questions. At the end of the survey, respondents were asked to self-select into stage two of the research, where they would become an individual case study. A total of 22 survey participants volunteered to do so, with five being selected to participate in stage two case studies. Five case-study participants undertook three 30–60-minute extended interviews in the second research stage. These interviews were conducted via Zoom, recorded, and transcribed. outlines the demographic information of the case study participants and relevant details, including assigned pseudonyms. Before interviews were conducted, informed consent was obtained that guaranteed individual anonymity and data confidentiality. Survey data of the case study participants were analysed and used to shape the topics for discussion in the proceeding interviews as well as a formal but flexible structure of topics discussed mapped out across the program of interviews prior to their commencement. This structure was designed in a way to build rapport between case study participant and the researcher, but also more specifically stage and detail the ways in which these case study teachers were constructing their curriculum-making, and what was influencing these decisions

Table 1. Case study participant demographic information.

In the first interview, participants were asked about the general perceptions of their role, what influences their prioritization and decision-making for their students, and their relationship with the teaching profession more generally. Interview two focussed on the curriculum and how they use and operationalize it on a day-to-day and planning level. Interview three focussed on the level of support participants currently received and what or how this could be improved.

Analysis

Survey data were analysed using a hybrid mixed-methods design approach. Qualitative analysis was undertaken using the constant comparative method to map thematic patterns across multiple open-ended response questions (Glaser & Strauss, Citation1967; Maykut & Morehouse, Citation1994) using NVivo 13 (Lumivero, Citation2020). Quantitative analysis was completed by descriptive analysis of all yes/no, rating and Likert questions as well as specific correlational analysis of results to identify patterns and relationships between responses related to the research question.

Case study data were analysed using reflexive thematic analysis in NVivo 12. Reflexive thematic analysis is an iterative process that includes data familiarization, initial coding, the creation of themes and then a process of reflection, leading to revision and refinement (Braun & Clarke, Citation2021; Nowell et al., Citation2017). Reflexive thematic analysis allows researchers to effectively respond to questions that investigate the behaviours and motivations of individuals and explore underpinning factors of influence central to the intention of the second stage of the research (Braun & Clarke, Citation2019).

A final analytical stage was performed by combining the case study and survey qualitative data sets using a hybrid thematic analysis process (Fereday & Muir-Cochrane, Citation2006). A deductive a priori template codebook was developed as described by Crabtree and Miller (Citation1992). The researchers reflected on the models already proposed by Ruppar et al. (Citation2015) and Siuty et al. (Citation2018) and identified the consistent themes across both, which were translated into the primary codes used to analyse data. These primary codes were then combined with the inductively produced sub-codes and recontextualised into a codebook thematic analysis process. This approach allowed the study’s phenomenological underpinnings and context-specific findings to remain intact while also developing an analytical framework with a high level of relationality to the field (Fereday & Muir-Cochrane, Citation2006).

Ethics

The research was approved by the University’s Human Ethics Research Committee H-2020–0161.

Results

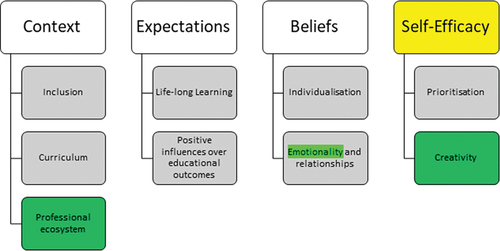

In response to answering the question, what are the influences upon teachers’ curriculum-related decision-making when using current national and state-endorsed curricula and supporting documents to support students with severe intellectual disabilities or profound and multiple learning difficulties in specialist education settings?, the following themes and sub-themes emerged and are displayed in . These themes were developed in the final analysis stage, with primary themes adapted from existing theoretical frameworks first developed by Ruppar et al. (Citation2015) and then adapted by Siuty et al. (Citation2018).

Figure 1. Primary themes as adapted from Ruppar et al. (Citation2015) and Siuty et al. (Citation2018) and sub-themes. Shading is used to differentiate newly introduced (yellow) or adapted thematic findings from previous research conducted in other countries (green).

Adaptations to the frameworks

Due to the nature of the research being conducted within the Australian context and specifically with teachers who work in specialist education settings (SSPs), the research team felt the need to include additional thematic constructs that were found in the data, compared to those seen in the consistent themes across Ruppar et al. (Citation2015) and Siuty et al. (Citation2018). These modifications are reflected in through differential shading.

Context

Inclusion

Case study participants were asked about their definitions of inclusive education as educators working in traditionally perceived most exclusionary school placement settings. All case study participants reframed the idea of inclusive education into a philosophical rather than structural motivator, linking their interpretations with creating a sense of value, respect and belonging in their students rather than that of a structural or systems concern. Rob articulated a personal positioning as, ‘Inclusion is just about appreciating the person or the individual … my focus is giving the kids independence, treating them like human beings’. Tally, Maya and Sophie also referenced the movement towards full inclusion in education but were apprehensive about the capacities of the current system to provide a truly inclusive experience, and each discussed the need for specialist education settings, citing structural, resourcing and skills limitations of the current system; Tally reflecting that ‘inclusion for these guys is probably different to what the Department of Education line is … I don’t think it would be successful for all these kids here … I want them to be recognized and represented in [curriculum] planning, so inclusion is about their needs being met’, and Kate echoed this ‘I feel like we have that fight with the department. The department is championing [full] inclusion again, and that is great, but there is no one that is down at our level to understand the abilities and capacities of our students’. Maya reflected on the role SSPs play within the system of supports,

I would love it if we lived in a world where we didn’t have SSPs. A lot needs to happen before we are ready to do that, so inclusion isn’t just grabbing all the kids and chucking them into a support unit or mainstream setting and saying good luck, for inclusion, that would be terrible.

Rob went on to celebrate how inclusive his experience of working in an SSP has been ‘It may look exclusive, but then I’ve never felt happier with teaching. This is the only setting that encapsulates what I feel inclusive teaching is, and that this is purely student centred’.

Most case study participants raised concerns about exclusionary elements a full inclusion model could have on their students.

I’m all for inclusivity. I want that, but with our kids, we need to weigh up how much damage we could do to them … we have young men who have been known to smear faeces on them or put bodily fluids around the school due to their sensory needs, how would that be responded too … it’s not appropriate behaviour, but here we can take our time to teach them that … like, if they were having a meltdown, is a school going to suspend them?.

Curriculum

Each case study participant similarly viewed their formal curriculum structures and referred to it as a framework they need to report to, but that it is not something they perceive to have meaning for their students. Maya and Sam reference the support that a curriculum can provide in terms of structural guidance but consistently referred to the problematic nature of it not including relevant content and/or age-appropriate outcomes to work towards. There was another shared concern regarding the differential interpretation of achievement for these students, and their progress not being able to be quantified and celebrated by the system.

…it’s hard when we have kids who are stage 5 (13–15 years old). There isn’t a (relevant) life skills curriculum for them, so we go back and look at early stage 1. It sucks that they sometimes can’t achieve at that level; it’s so disheartening for the child - Rob

The need for high levels of adaptation to the curriculum, all case study participants spoke about inconsistency in student learning and their concern for gaps in quality programming, with Sam noting, ‘Some teachers just go in and do what they want, you know, and make it up because obviously there is a gap. It might be a good lesson, but does it mean anything [in the long term]?’

Professional ecosystem

Case study participants expressed a feeling of otherness or isolation from the professional teaching ecosystem but conveyed this in numerous ways. Rob and Kate both viewed this disconnection as a privileged one, defining themselves as being ‘lucky’ not to be in mainstream environments and expressing sympathy for their teaching peers who work outside of SSPs, Rob reflected on the differences between his own and mainstream teaching peers’ priorities.

Our mainstream colleagues have got it tenfold worse than us … I feel they have been let down, I feel like so many teachers want to be student centred, but they are dancing to the beat that is now business orientated, not teaching-orientated … I can come in and be student focussed, try new things; it’s what I imagined teaching to be.

Maya, Tally and Sam each referenced a disconnection that raises conflict, ‘I just feel like the Department or NESAFootnote1 does not consider us … it just makes me indignant, like I want to stamp my foot and say this is not fair. This is not right’.

Expectations

Life-long learning

In the survey data, there was a significant trend in participant responses that reflected a whole-of-life positioning to their choice-making regarding curriculum design.

[My role] is so they [the student] can make choices for their own needs post-school. Communicate their needs, aspirations and choose the outcomes best for them. Be able to access the world around them and enjoy their life and have good strong relationships with friends, family and community.

Kate, Tally and Maya all expressed their dedication to the provision of space for students through the curriculum they designed to explore their own identities as a pathway to social and emotional inclusion in adulthood, ‘I want to be able to provide a place and a space for their identity and independence to be explored … to learn to be visible in the community and be loved, just to enjoy it’ (Kate). Survey respondents and case study participants related these more broadly holistic intentions of education to the day-to-day activities of the classroom, particularly when articulating the motivations behind curriculum choices and academic skills development;

If they can’t read or write by the time they get to year 11 (age 17), I’m not going to be able to advance them too much … So, it’s not just A, B, C, but it’s about understanding that a train starts with T so that when you are looking for a train station, you’re looking for the letter T.

Kate, who is in a regional setting, raised the issue of post-school opportunities, and the lack of availability motivated her, even more, to focus on designing a curriculum that focuses on skills for living and independence.

It’s about giving them a toolbox, what I worry about with my students is that they can’t carry their own toolbox. They often need people there. We have spent so much time working with them, then suddenly let them go, and what do they have in the current situation? There is not a lot, that’s a whole other issue.

Positive influences over educational outcomes

Survey respondents were asked what they thought had the most influence over a positive educational experience for their students. They ranked options from most influential to least influential, as shown in . When analysed concerning how long a participant had spent in an SSP environment, it was shown that these perceptions are reliably consistent and do not change when compared to experience level (p = 0.5).

Beliefs

Individualisation

Across both stages of data collection, individualization for students was central to all responses regarding decision-making. The process of individualization was always referred to as a necessity of the role, but participants viewed its impact on their decision-making schema from different perspectives. Some participants viewed individualization as being a time-intensive and almost ‘blind’ process of trial and error, while others conceptualized individualization practices as the opportunity for creativity and positive risk-taking when planning and implementing their teaching programs. Sam combines this idea of constant trial and error with the idea of being able to plan for failure; however, being one of the most stimulating qualities of their role,

I find it extremely frustrating because you are trying to teach them something and you think, come on, you did this yesterday, or this worked for X, why can’t you do it? But I like the challenge of it … it’s an opportunity to try a different format and it’s amazing to see when you finally get the right thing … if I wanted to teach everything the same way, I’d be working in mainstream, it’s that thinking outside the box that I really enjoy.

With so many individual programs to manage, Maya and Tally referred to how they have seen some staff fall into less considered choice-making patterns to cope with such a complex environment, with a reliance on repetition and falling into habits that promote learned helplessness in their students, or transitioning away from the role of teacher, and skewing more towards making choices from a caring/carer position.

Emotionality and relationships

It is evident in all qualitative responses collected in both phases of the research that participants have a deep emotional connection to their students and place deep importance on the relationships they form. When asked about the way they see their lifelong connection to their students, a survey respondent expressed the profound importance they place on their role, ‘I can offer them someone who listens, cares for, and supports, loves them, and someone who believes in them. Sometimes our students don’t ever get this’ (survey participant). All five case study participants spoke about reciprocity and trust with their students and that they were co-facilitators in the success of their educational journey. Kate explained that these positive emotions keep her in her role,

That’s what keeps me coming back … giving these kids just a great opportunity, fun days … I love imparting knowledge with these kids to be able to make their way in the world … I’ve still got that in my heart. That drives me.

Conversely, Rob-related trust between teachers and students as formative to the learning process, ‘the curriculum can’t start, or the teaching itself can’t start until you have that relationship and that trust’.

Evident in the case study interviews was the presence of some significantly negative feelings of anger, frustration, isolation, guilt, and fatigue. Two of the five case study participants have had to take considerable time off work due to fatigue or the emotional impacts felt in their role, with all five expressing deep concern over the lack of support offered to them as a staffing cohort due to a lack of directed support from either internal leadership or the system. Of the five, Rob was the only one enthusiastically positive about their support, linking this to his positive emotional well-being.

One of the five case study participants raised and discussed relationships with parents and/or caregivers. Maya saw parent relationships and collaboration as central to her work,

Most of the time it’s about building up a good rapport with parents, and it comes down to trust. They trust me. At the end of the day, that will lead to better outcomes for students if the families are on board and feel supported.

Other participants either did not reference this relationship at all or only minimally articulated it as a consideration. The results seen in the quantitative data reinforce this trend, with survey respondents rating home and school links as being of only mid to low-level influence on educational experiences () and then again rating family/home needs and wants as being the seventh lowest element prioritized when making curriculum choices ().

Self-Efficacy

Prioritisation

Survey respondents were asked to rank a series of pre-determined factors that influence their decisions when planning a student’s individualized curriculum. displays the rank order of responses, from highest influencing factor to lowest. These data were analysed in relation to how long a participant had spent in an SSP environment, a p = 0.369 was calculated, indicating that these perceptions are reliably consistent and do not change when compared to experience level. One finding is that teachers with less experience in the SSP setting presented a slightly different profile, with safety, well-being and independence factors attracting much greater prioritization. There was a correlation between respondents who rated their curriculum less favourably and their prioritization behaviours (p = 0.036). demonstrates this relationship, with respondents who rated their curriculum less favourably more strongly de-prioritizing academic skills and curriculum outcomes. Across all response categories, the factors that are based on teacher/student interactions have a more substantial influence (safety, strengths and interests, independence, well-being, and happiness) over community engagement (Parent/home relationship, community access) and academic learning and development (skills, curriculum outcomes and academic skills).

Creativity

All case study participants referred to the foundational need for creativity in their roles, highlighting this as a primary motivator for their sustainability and enjoyment. The need for creativity was seen as a product of the amount of structural support they received, with Rob detailing, ‘Like it’s more creative and it’s more fun, but because you don’t have something prescriptive, you know, you’ve actually got nothing to guide you’. Rob continued to also speak about the creative nature of having to teach across all KLAs (Key Learning Areas), articulating that extending beyond his original scope of speciality (PD/H/PE) has been a motivating feature of the role for him. Kate expanded this creative agility into everyday decisions, giving an example of how creative agility and the prioritization of different outcomes are enacted.

[We] were mucking around a bit, and one of our students who doesn’t always interact with everybody comes in. He’s like, hey guys, he put his hands out, and he was just laughing his head off, and we stopped our lesson just to have that fun, playful interaction. I’m not going to say stop; we’ve gotta do numbers now, Yeah, I’m gonna continue that interaction.

Maya also referenced, ‘I can do all the planning in the world, but if a kid comes in and has a meltdown, then we just have to think on our feet, and just adjust without notice’.

Discussion

While most results are similar to work previously conducted by Ruppar et al. (Citation2015) and Siuty et al. (Citation2018) some clear differences have been explored. New themes, or re-definitions of them, have emerged from this research, with the differential findings within the Professional Ecosystem, and emergent themes of Creativity and Emotionality and Relationships being introduced. Each will be examined in terms of their differential positioning or emergence. Emergent trends will also be discussed.

Professional eco-system

The professional eco-system in which a teacher works is of significant influence over the choices they need and want to make. Although not presenting a formal model of decision-making, the work of Timberlake (Citation2016) introduces the concept of aloneness and isolation as a significant factor of influence over feelings of connectedness between teachers and their profession. Siuty et al. (Citation2018) explore these feelings in their discussion, but do not directly include these factors in the model presenting their findings. The analysis of the findings of this study has centralized the need to consider these features explored by Timberlake (Citation2016) which were more generally perceived as being restrictive to teacher efficacy and practices. This study has shown that although this feeling of disconnection exists, it has been translated by participants in a manner that indicates feelings of freedom and a sense of professional privilege over their mainstream peers regarding administrative burdens and relational opportunities. Similarly, there was anger at the lack of support offered to them by the system, but it was not defined necessarily through negative conceptualizations as seen in Siuty et al. (Citation2018) and Timberlake (Citation2016), but with a broader positivity to the future. This finding is in contrast to expectations when considering the known higher rates of burnout and negative psychological stress as seen in the work of Brunsting et al. (Citation2014, Citation2022) and Lerner et al. (Citation2015), which will be explored in more detail later, but are evidenced in the data with some case study participants needing to take time off work or being diagnosed with compassion fatigue. This differential finding raises the question of whether it is due to the system structures of working in an SSP that these teachers are more susceptible to negative emotional and psychological impacts of their work or if it is related to something else. Alongside the differential interpretations compared to previous work, some important influencing features to the professional eco-system influence these teachers’ attitudes, engagement, and usage of the curriculum.

The desire for connection and support

Participants showed strong trends in maintaining focus on professional standards of practice and quality but were mostly of the mindset that current professional structures do not allow for this to be upheld. Participants often referred to a professional distance between ‘us’ and them (mainstream teachers), and a lack of inclusive professional development and support tailored to their needs. However, participants consistently expressed a personal motivation and willingness to engage and participate with mainstream teachers and the supports provided.

The psychological gap

By not feeling included in professional discussions, training or development activities regarding curriculum, participants of this study were able to positively contextualize a psychological separation from curriculum centralization and the inherent role responsibilities expected of curriculum entitlement and standardization. This real and envisaged psychological gap extends to how participants articulated success, achievement, and intentionality of teaching. Although potentially reinforcing for these teachers’ choices, these differential interpretations to the definitions as articulated by the system, play into decreasing feelings of self-efficacy, with frequent ‘in comparison to’ statements regarding not being cared about or forgotten. Often, when participants were asked to justify or uphold standardized system requirements, it was expressed as a professional shrug and only minimal positive connection, indicating an isolation from the profession and feelings of professional exclusion, a feature of the work of Timberlake (Citation2016), who found that the feeling of aloneness is a pervasive feature to the identities of teachers who support students with severe or profound and multiple learning difficulties.

Emotionality and relationships

The level of emotional connection and everyday relational attributes of work that these teachers feel is a core component of success when designing effective curricula for their students. Its central prevalence in most aspects of discussions and survey responses required a new theme to be added to the existing model as defined by Siuty et al. (Citation2018). Emotionality and relationships with students are discussed in a way that allows for a nuanced tailoring of experience and developmental progression. It also increases nuanced communicative reciprocity, and its importance as an active agent of positive experiences for students and teachers. This newly added component is somewhat parallel to the emergent proposition of Ljungblad (Citation2021) of Pedagogical Relational Teachership (PeRT). PeRT is a multi-dimensional model of teaching that focusses on the relationality between student and teacher as the central feature to inclusive educational practice that allows space for student’s voices and identities to emerge as active agents of participation, equity, and access (Ljungblad, Citation2021).

In acknowledging the positive impacts this feature of teachers decision-making schema, the level and centralization of emotionality between student and teacher expressed within these findings is concerning, considering the known higher rates of burnout in similarly placed teacher populations (Brunsting et al., Citation2014, Citation2022). With the emergence choice maximalisation through minimally active structural supports, the decision-making process for this population of teachers evolves into a high stake, high stress state of professional activity (Dar-Nimrod et al., Citation2009; Lerner et al., Citation2015). Stress and perceived singular levels of responsibility is further heightened with the emotional driver of student relationality at the heart of these teachers’ daily choice-making as an unevenly influential feature comparative to less emotively empowered structures and role requirements (Brunsting et al., Citation2014, Citation2022; Ljungblad, Citation2021).

Creativity

All case study participants expressed a sustaining and important engagement with creativity as a central positive feature of their work in curriculum decision-making. Creativity is borne from the need for fully individualized responses to students regarding curriculum planning and implementation. However, creativity is also given space to grow within the gap that exists between the role and expectations of policy and practice. It is important to note that this newly added theme is defined through Ripple’s (Citation1989) term of ordinary creativity which captures the unique thinking and choice-making behaviours people display when within an everyday context of problem-solving. Although most teachers will display aspects of ordinary creativity, it is heightened by the need to design specifically individual programming within an environment of dilemma and to overcome obstacles and conflict within the system in which they work (Bramwell et al., Citation2011).

Emergent trends

Prioritisation of curriculum entitlement

There is a significant conflict between what participants think has a positive impact on students’ curriculum experiences and how they themselves prioritize when making decisions. Evidenced in curriculum being placed in the top three features of what they think has the most positive impact on student learning, but then when asked how they themselves prioritize features to their decision-making, curriculum is significantly deprioritised. With the significant gap between practice and professional obligations already discussed, as well as the apparent lack of meaningful professional motivations to engage with the curriculum as it is, this is an unsurprising result. What it reveals is two-fold. One, the overarching influence of intuitive and holistic prioritization considerations that influence curriculum constructions, and two, an underestimation of the power of curriculum inclusion. By recognizing the importance and power effective curriculum structures can have over student outcomes, but then moving rapidly away from engagement within these structures, reveals an underestimation by the system itself of these teachers’ critical want for curriculum entitlement and inclusion, revealing a conflict of curriculum ideologies at the heart of these findings (Schiro, Citation2013).

Parent relationships

There are minimal references to parent relationships with only one case study participant, Maya, directly discussing the value and importance of this relationship to their decision-making schema. The survey results also list this as a significantly deprioritised component for consideration in curriculum design. This is a feature at odds with both contemporary policy directives, and best practice evidence for individualized curriculum development protocols (Downing & Peckham-Hardin, Citation2007; Harkins, Citation2013; Weiss et al., Citation2018).

Due to the explorative nature of this study, there are many recommendations for future areas of research that are borne from the results and a lot of questions remain unasked, and or unanswered.

Recommendations for future research

Current supports

It is recommended that a thorough examination of the supports available for these teachers currently be audited and assessed. This should include a discussion with teachers about what they feel is needed in terms of support, from professional learning to resourcing and advice. With the motivation for the provision of an education system that is fully inclusive of all student needs; the investigation of current supports for teachers and schools supporting students with severe or profound and multiple learning difficulties would be of high impact and usefulness, as there is little reported of effective ongoing learning and support for teachers in the most specific schooling environments. This is of specific relevance considering the DRC recommendations regarding the eventual closure of SSP settings, where teachers in mainstream settings will be expected to support students with higher levels of acuity and a thorough program of professional learning will be needed to equip teachers with the right skills and experiences to include all students (Commonwealth of Australia, Citation2023). The researchers query whether, with the motivation for a fully inclusive education system, we are equipped with enough foundational support for all teachers to understand, plan and respond to the needs of the students with the most complex of needs in less restrictive educational spaces if we cannot yet even address the needs of those in the schools perceived and designed to be the most specifically equipped to support them in both resources and teacher capacity. This would require significant policy and resourcing commitments for change, and extensive collaborative design processes between policy makers, teachers from both mainstream and SSP environments, students and families, and researchers. With the current systemic underfunding of public education, and a lack of precedence in holistic curriculum reform in Australia, the researchers lament the capacity of the system to implement the changes required.

Moral conflict and the dilemmic space

Teachers of students with severe or profound and multiple learning difficulties are often placed in a position of ongoing, continuous negotiation between their systems policy and structural requirements for curriculum entitlement and inclusion, and the need for student-centred planning and implementation practices. According to Vink et al. (Citation2015) moral conflict occurs when a person’s professional role exists within an environmental context where they are asked to negotiate between two or more conflicting value propositions, norms, and/or responsibilities to fulfil their role expectations and support their own professional expectations in a consistent and ongoing basis. There is an alignment here to the recent work of Norman (Citation2022) and the premise of Foucault’s counter-conduct, positioning this discussion not as a negative attribute to practice but one in response to upholding moral imperative.

Although this study focuses specifically on the curriculum planning and implementation environment for teachers, the results show a much more pervasive set of influences that define teacher practices sitting at odds with not just professional expectations, but with deep philosophical and relational foundations that speak to a core set of value orientations. These sit in opposition to the current educational climate, structure, and policy frameworks. Fransson and Grannas’ (Citation2013) conceptual proposition of the dilemmatic space relates to an overarching environment of ethical conflict that teachers may operate within, rather than limited to formal professional interactions or operational choices. The authors feel this would be a worthwhile conceptual framework for any further investigation in this field.

Burnout and psychosocial safety

Brunsting et al. (Citation2022) show higher rates of burnout and fatigue within similarly aligned teaching populations in specific learning environments. It is recommended that this is investigated specifically in relation to teachers of students with severe or profound and multiple learning difficulties as well as with a scope to identify the primary reasons for emotional stress and burnout. Similarly, with ordinary creativity being established as a core feature of these teachers’ practices, the issues of time availability and community support (school leadership and cultural climate) required for environments for psychosocial safety to develop, and for creative practice to be sustainable, need to be prioritized areas (Bramwell et al., Citation2011).

Parent–teacher relationship

The misalignment between results captured and known importance of teacher–parent relationships needs further specific study. The overwhelming motivations of whole-of-life outcomes and inclusion that participants expressed as being highly influential to their decision-making is indicative of strong home–school partnerships; and perhaps due to the specific nature of curriculum as the framing topic of discussion limited participant expressions of these important relationships.

Limitations

Broadening the workplace location would offer a larger participant base and provide the opportunity to compare experiences across the settings to assess whether all teachers of students with severe intellectual disabilities or profound and multiple learning difficulties have a shared perspective or if it is specific to those working in specialist government funded schooling environments. The survey was only open for a three-month period and was released during a COVID-19 lockdown in Australia, which may have limited the enthusiasm for engagement or influenced responses. There were limitations related to recruitment, the use of peak organizational bodies as primary distribution partners which restricted recruitment reach. Using peak organizations as distribution partners meant that the research team could only contact participants indirectly, reducing the potential participant pool.

Conclusion

This paper sought to present the factors of influence over Australian teacher’s decision-making when curriculum planning for students with severe or profound and multiple learning difficulties. Aligning with work done internationally, there are some significant areas of variation that need to be further investigated and some specific gaps than need rigorous attention. The results profile a professional space defined by multiple curriculum conflicts, and that bear both highly positive and highly detrimental implications for teacher professional practice, curriculum enactment, and personal wellbeing. From this study we have learnt that this group of teachers is highly passionate, skilled, and committed to their student’s educational development and personal wellbeing and hold a high sense of professionalism. We have learned that the curriculum, as it is, is critically underperforming for teachers and students alike. We have learned that these teachers are operating in a professional space filled with ethical, role and system misalignments that needs an immediate response and immediate resourcing support at all levels of policy, research, and practice activities if our teachers and schools are to be equipped with the skills, financial and practical capacity to provide best quality curriculum inclusion for all students.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. New South Wales Education Standards Authority.

References

- Anderson, J., & Lighfoot, A. (2022). Exploratory research methods. In K. Dikilitas & K. M. Reynolds (Eds.), Research methods in language teaching and learning: A practical Guide (1th ed., pp. 182–199). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority. (2023). Student diversity. The Australian curriculum. Retrieved July 18, 2023, from https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/resources/student-diversity/

- Australian Government. (2022a). Disability discrimination act 1992. Federal register of legislation. Retrieved December 20, 2023, from https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2018C00125

- Australian Government. (2022b). Disability standards of education 2005. Department of education skills and employment. Retrieved December 20, 2023, from https://www.education.gov.au/disability-standards-education-2005

- Blackley, C., Redmond, P., & Peel, K. (2020). Teacher decision-making in the classroom: The influence of cognitive load and teacher affect. Journal of Education for Teaching, 47(4), 548–561. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2021.1902748

- Bramwell, G., Reilly, R. C., Lilly, F. R., Kronish, N., & Chennabathni, R. (2011). Creative teachers. Roeper Review, 33(4), 228–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/02783193.2011.603111

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qualitative Research in Psychology, 18(3), 328–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238

- Brunsting, N. C., Bettini, E., Rock, M., Common, E. A., Royer, D. J., Lane, K. L., Xie, F., Chen, A., & Zeng, F. (2022). Working conditions and burnout of special educators of students with EBD: Longitudinal outcomes. Teacher Education and Special Education, 46(1), 44–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/08884064221076159

- Brunsting, N. C., Sreckovic, M. A., & Lane, K. L. (2014). Special education teacher burnout: A synthesis of research from 1979 to 2013. Education and Treatment of Children, 37(4), 681–711. https://doi.org/10.1353/etc.2014.0032

- Colley, A., & Tilbury, J. (2022). Enhancing well-being and independence for young people with profound and multiple learning difficulties: Lives lived well. Routledge.

- Commonwealth of Australia. (2023). Royal commission into violence, abuse, neglect and exploitation of people with disability final report. Volume 7: Inclusive education, employment and housing summary and recommendations. Retrieved December 22, 2023. from https://disability.royalcommission.gov.au/system/files/2023-09/Final%20Report%20-%20Volume%207%2C%20Inclusive%20education%2C%20employment%20and%20housing%20-%20Summary%20and%20recommendations.pdf

- Cook, B., Tankersley, M., & Harjusola-Webb, S. (2008). Evidence-based special education and professional wisdom: Putting it all together. Intervention in School and Clinic, 44(2), 105–111. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053451208321566

- Crabtree, B. F., & Miller, W. F. (1992). A template approach to text analysis: Developing and using codebooks. In B. F. Crabtree & W. L. Miller (Eds.), Doing qualitative research (pp. 93–109). Sage.

- Dar-Nimrod, I., Rawn, C. D., Lehman, D. R., & Schwartz, B. (2009). The maximization paradox: The costs of seeking alternatives. Personality and Individual Differences, 46(5–6), 631–635. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2009.01.007

- Datta, P., Aspland, T., & Talukdar, J. (2019). Curriculum, assessment and reporting practices in Australia towards students with special educational needs and disabilities. Curriculum & Teaching, 34(1), 23–41. https://doi.org/10.7459/ct/34.1.03

- Derryberry, W. P., & Thoma, S. J. (2005). Moral judgement, self-understanding, and moral actions: The role of multiple constructs. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 51(1), 67–92. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23096050

- Downing, J. E., & Peckham-Hardin, K. D. (2007). Inclusive education: What makes it a good education for students with moderate to severe disabilities? Research & Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 32(1), 16–30. https://doi.org/10.2511/rpsd.32.1.16

- Fereday, J., & Muir-Cochrane, E. (2006). Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(1), 80–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690600500107

- Fransson, G., & Grannäs, J. (2013). Dilemmatic spaces in educational contexts : Towards a conceptual framework for dilemmas in teachers work. Teachers & Teaching, 19(1), 4–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2013.744195

- Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory. Strategies for qualitative research. Routledge.

- Harkins, S. (2013). Inclusive education as a lived experience: School career studies of students with mild, moderate, and severe disabilities. The International Journal of Diversity in Education, 12(3), 43–52. https://doi.org/10.18848/2327-0020/CGP/v12i03/40064

- Jones, N., & Youngs, P. (2012). Attitudes and affect: Daily emotions and their association with the commitment and burnout of beginning teachers. Teachers College Record, 114(2), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811211400203

- Lawson, H., & Jones, P. (2018). Teachers’ pedagogical decision-making and influenced on this when teaching students with severe intellectual disabilities. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 18(3), 196–210. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-3802.12405

- Lerner, J. S., Li, Y., Valdesolo, P., & Kassam, K. S. (2015). Emotion and decision making. Annual Review of Psychology, 66(1), 799–823. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115043

- Ljungblad, A. (2021). Pedagogical relational teachership (PeRT) – a multi-relational perspective. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 25(7), 860–876. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2019.1581280

- Lumivero. (2020). NVivo (Version 14). www.lumivero.com

- Maykut, P., & Morehouse, R. (1994). Beginning qualitative research: A philosophic and practical guide (Vol. 6). Falmer Press.

- Nind, M., & Strnadova, I. (2020). Changes in the lives of people with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities. In M. Nind & I. Strnadova (Eds.), Belonging for people with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities (pp. 1–21). Routledge.

- Norman, P. (2022). Good teachers and counter conduct. Critical Studies in Education, 64(4), 301–317. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2022.2142627

- Nowell, L., Norris, J. M., White, D. E., & Moules, N. J. (2017). Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917733847

- Rendoth, T., Duncan, J., Foggett, J., & Colyvas, K. (2024). Curriculum effectiveness for secondary-aged students with severe intellectual disabilities or profound and multiple learning difficulties in Australia: Teacher perspectives. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities. https://doi.org/10.1177/17446295241228729

- Rendoth, T., Foggett, J., & Duncan, J. (n.d). Curriculum decision-making for students with severe intellectual disabilities or profound and multiple learning difficulties. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education.

- Ripple, R. E. (1989). Ordinary creativity. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 14(3), 189–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/0361-476X(89)90009-X

- Ruppar, A. L., Gaffney, J. S., & Dymond, S. K. (2015). Influences on teachers’ decisions about literacy for secondary students with severe disabilities. Exceptional Children, 81(2), 209–226. https://doi.org/10.1177/0014402914551739

- Schiro, M. (2013). Curriculum theory: Conflicting visions and enduring concerns (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

- Siuty, M. B., Leko, M. M., & Knackstedt, K. M. (2018). Unravelling the role of curriculum in teacher decision making. Teacher Education and Special Education, 41(1), 39–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/0888406416683230

- Stewart, C., & Walker-Gleaves, C. (2020). A narrative exploration of how curricula for children with profound and multiple learning difficulties shape and are shaped by the practices of their teachers. British Journal of Special Education, 47(3), 350–375. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8578.12313

- Timberlake, M. T. (2016). The path to academic access for students with significant cognitive disabilities. The Journal of Special Education, 49(4), 199–208. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022466914554296

- Vink, E., Tummers, L., Bekkers, V., & Musheno, M. (2015). Decision-making at the frontline: Exploring coping with moral conflicts during public service delivery. In D. Alexander & J. Lewis (Eds.), Making public policy decisions (pp. 112–128). Routledge.

- Walker, P. M., Carson, K. L., Jarvis, J. M., McMillan, J. M., Noble, A. G., Armstrong, D. J., Bissaker, K. A., & Palmer, C. D. (2018). How do educators of students with disabilities in specialist settings understand and apply the Australian curriculum framework? Australasian Journal of Special & Inclusive Education, 42(2), 111–126. https://doi.org/10.1017/jsi.2018.13

- Weiss, S., Markowetz, R., & Kiel, E. (2018). How to teach students with moderate and severe intellectual disabilities in inclusive and special education settings: Teachers’ perspectives on skills, knowledge and attitudes. European Educational Research Journal, 17(6), 837–856. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474904118780171