?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

We use household survey data from Nepal to investigate relationships between women’s empowerment in agriculture and production diversity on maternal and child dietary diversity and anthropometric outcomes. Production diversity is positively associated with maternal and child dietary diversity, and weight-for-height z-scores. Women’s group membership, control over income, reduced workload, and overall empowerment are positively associated with better maternal nutrition. Control over income is positively associated with height-for-age z-scores (HAZ), and a lower gender parity gap improves children’s diets and HAZ. Women’s empowerment mitigates the negative effect of low production diversity on maternal and child dietary diversity and HAZ.

1. Introduction

An extensive literature demonstrates that the linkages between agriculture, health and nutrition are dynamic and multifaceted (Headey, Citation2012; Kadiyala, Harris, Headey, Yousef, & Gillespie, Citation2014; Ruel & Alderman, Citation2013; Von Braun & Kennedy, Citation1994). Drawing on this literature, Ruel and Alderman (Citation2013) identify six pathways through which agricultural interventions can impact nutrition: i) agriculture as a source of food for own consumption, ii) agriculture as a source of income, iii) agricultural policies on prices of food and non-food crops, iv) the effect of women’s social status and empowerment on their access to and control over resources, v) the impact of women’s participation in agriculture on their time allocation, and vi) the impact of women’s participation in agriculture on their own health and nutritional status. The first three pathways relate directly to agriculture. In rural subsistence or semi-subsistence households that consume the bulk of their own production, diversity of crops grown contributes directly to dietary diversity and improved nutrition. The last three pathways highlight the importance of women’s roles in agriculture, and of women’s empowerment in general, to achieving health and nutrition outcomes. Kadiyala et al. (Citation2014), using a similar framework, emphasise the role of the gender division of labour in agriculture, which influences women’s time for taking care of herself and young children, the intrahousehold allocation of food, which affects women’s nutritional status with its intergenerational effects on nutrition outcomes, and women’s power in decision-making, which influences whether gains in income translate into nutritional improvements.

Drawing from this framework, we hypothesise that both production diversity and women’s empowerment are important determinants of maternal and child nutrition in rural semi-subsistence households such as in Nepal. Using a 2012 survey of 4,080 rural Nepali households, we test whether women’s empowerment modifies the impact of production diversity on nutritional outcomes, and in which direction: does women’s empowerment mitigate the effect of low production diversity on nutrition, or does it exacerbate it? We use a newly-developed index, the Women’s Empowerment in Agriculture Index [WEAI] and its component indicators (Alkire et al., Citation2013), to assess the extent of women’s empowerment in agriculture, diagnose areas where gaps in empowerment exist, and examine the relationship of the underlying empowerment indicators with dietary diversity and nutritional status. The WEAI, a survey-based index using individual-level data collected from primary male and female respondents within the same households, is similar in construction to the Alkire-Foster group of multidimensional poverty indices (Alkire & Foster, Citation2011a, b). We use the aggregate measure of women’s empowerment, its component indicators in dimensions where women are most disempowered, and the empowerment gap between men and women in the same households, to better identify areas for policy intervention to improve maternal and child nutrition.

Our results show that production diversity at the household level is strongly associated with mothers’ and children’s dietary diversity and children’s weight-for-height [WHZ] z-scores. Indicators of empowerment are somewhat more strongly associated with maternal rather than child outcomes. We find that engagement in the community, control over income, reduced workload, and the overall empowerment score are positively associated with better maternal nutrition. Control over income is associated with better height-for-age z-scores [HAZ], and a lower gender parity gap improves children’s diets and long-term nutritional status. Women’s empowerment also mitigates the negative effect of low production diversity on maternal and child dietary diversity and HAZ, indicating that women’s empowerment has greater potential to improve nutrition outcomes in households with less diverse production.

2. Conceptual Framework

2.1 Linkages between Empowerment, Production, and Nutrition

Production diversity may directly influence nutrition in agricultural households, not only through incomes generated from agricultural production, but also through home consumption. If households consume a large share of the food products they produce, more diverse production portfolios may increase the availability of different types of food for household consumption, in turn improving dietary quality among household members. Various studies (see Arimond et al., Citation2010 and resources cited therein) have documented associations between dietary diversity indicators and micronutrient intakes or adequacy in developing countries.

However, decisions on how and what to produce are mediated by gender roles. Accumulating evidence shows that men and women within households do not always pool their resources nor have the same preferences (Alderman, Chiappori, Haddad, Hoddinott, & Kanbur, Citation1995; Haddad, Hoddinott, & Alderman, Citation1997). The nonpooling of agricultural resources within the household creates a gender gap in control of agricultural inputs, which several empirical studies have identified as a constraint to higher productivity (Kilic, Palacios-Lopez, & Goldstein, Citation2013; Udry, Hoddinott, Alderman, & Haddad, Citation1995). Evidence from sub-Saharan Africa suggests that women’s control of resources has also been linked to larger allocations of resources to food. In Cote d’Ivoire, Hoddinott and Haddad (Citation1995) and Duflo and Udry (Citation2004) find that increasing women’s share of cash income significantly increases the share of household budget allocated to food. In Ghana, Doss (Citation2006) shows that women’s share of assets, particularly farmland, significantly increases food budget shares. In Bangladesh, greater empowerment of women, also measured using the WEAI, is associated with higher per adult-equivalent calorie availability and dietary diversity (Sraboni, Malapit, Quisumbing, & Ahmed, Citation2014).

Links between greater control of resources by women and child outcomes have also been documented in both observational and experimental studies (see Quisumbing, Citation2003; Yoong, Rabinovich, & Diepeveen, Citation2012). An expanded version of the 1990 UNICEF framework illustrates how several types of maternal resources may operate as key determinants of child nutritional status by influencing care practices such as feeding small children (Engle, Menon, & Haddad, Citation1997; UNICEF, Citation1990). In addition to caregiver education, physical health, and mental health, this framework includes the domains of maternal autonomy and control of household resources, workload and time availability, and social support networks (see Cunningham, Ruel, Ferguson, & Uauy, Citation2013a for a review of evidence from South Asia).

Although the above-mentioned studies have investigated the links between women’s empowerment and nutritional outcomes, and between production diversity and dietary quality, to our knowledge, no study has investigated whether and how women’s empowerment mediates the impact of production diversity on nutrition. The literature on maternal education and nutrition suggests that socioeconomic status and maternal education interact (see Leroy, Habicht, Gonzalez De Cossio, & Ruel, Citation2014 and resources cited therein), although the direction of interaction may vary across socioeconomic status. In Benin, Reed, Habicht, and Niameogo (Citation1996) find that the effect of maternal schooling was insignificant in the lowest stratum, positive and significant in the intermediate socioeconomic stratum, and weakly positive in the best socioeconomic category. In Mexico, Leroy et al. (Citation2014) find that maternal schooling mitigates the potentially negative association between increasing wealth and maternal weight, while fostering the positive association between household wealth and child linear growth. Evidence from Bangladesh suggests that the effect of women’s empowerment varies with wealth: Sraboni et al. (Citation2014), using the WEAI, have shown that the positive effect of different dimensions of women’s empowerment on calorie availability and dietary diversity is greater for smaller landowners, that is, for less well-off households.

2.2 Measuring Empowerment Using the WEAI

Linkages between women’s empowerment and nutrition have been more difficult to quantify owing to the difficulty of measuring empowerment. Kabeer (Citation1999) defines empowerment as expanding people’s ability to make strategic life choices, which encompasses three dimensions: resources, agency, and achievements (wellbeing outcomes). The WEAI focuses on the ‘agency’ aspect (input in decision-making), rather than on the value of income and other assets or on achievements such as educational levels or nutritional status. The WEAI differs from measures of empowerment derived from nationally-representative surveys such as some demographic and health surveys, because decision-making questions typically refer to the domestic sphere, not the productive and economic spheres. Most surveys also do not have identical questions for men and women (Alkire et al., Citation2013), making it difficult to compare men’s and women’s empowerment within the same household. Lastly, the WEAI captures control over resources within the agricultural sector, which is not covered by existing indices.

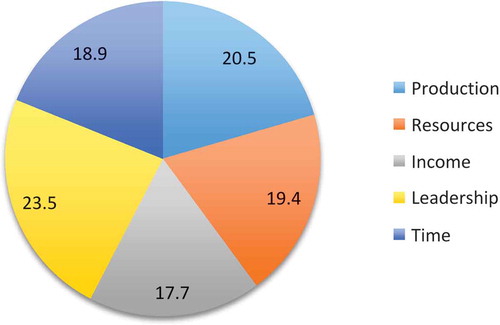

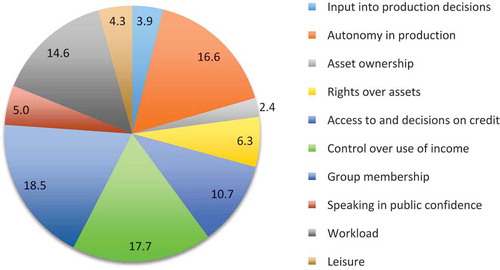

As an aggregate indicator, the WEAI is composed of two sub-indexes: (1) the five domains of women’s empowerment [5DE] and (2) gender parity (the Gender Parity Index [GPI]).Footnote1 The 5DE sub-index measures the roles and extent of women’s engagement in the agricultural sector in five domains: (1) decisions over agricultural production, (2) access to and decision-making power over productive resources, (3) control over use of income, (4) leadership in the community, and (5) time use. It assesses the degree to which women are empowered in these domains, and for those who are not empowered, the percentage of domains in which they are empowered.Footnote2 These domains are constructed using 10 indicators, defined in . The GPI reflects the percentage of women who are as equally empowered as the men in their households. For those households that have not achieved gender parity, the GPI shows the empowerment gap that needs to be closed for women to reach the same level of empowerment as men. (For details regarding the construction and validation of the index, see Alkire et al., Citation2013). In this paper, we use the individual-level women’s 5DE score and its component indicators, as well as the gender parity gap (men’s 5DE minus women’s 5DE), as measures of women’s empowerment.

Table 1. The five domains of empowerment in the WEAI

3. Country Context and Data

While rates of undernutrition among children under five years old have decreased dramatically in the past decade, current rates of undernutrition in Nepal still remain high: 41 per cent of children are stunted, 29 per cent are underweight, and 11 per cent are wasted (MOHP Nepal et al., Citation2012), with substantial regional variations. Socio-economic, demographic, cultural, gender, and ethnicity/caste factors also generate stark contrasts among different population subgroups’ health and nutritional outcomes (Joshi, Agho, Dibley, Senarath, & Tiwari, Citation2012; MOHP, Nepal, New ERA, & ICF International Inc., Citation2012; Nepal Global Health Initiative Strategy, Citation2010). Compounding these is women’s low social status, which is a key contributor to undernutrition among women and children in South Asia (Ramalingaswami, Jonsson, & Rohde, Citation1996; Smith, Ramakrishnan, Ndiaye, Haddad, & Martorell, Citation2003).

3.1 Survey Design

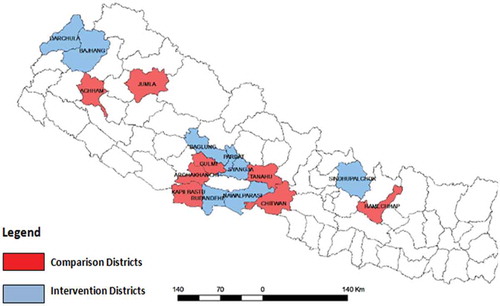

We use data from a baseline survey conducted as a part of the evaluation of Suaahara, a USAID-funded multisectoral nutrition programme in Nepal (Cunningham et al., Citation2013b). A total of 4,080 rural households with children below five years old were surveyed from June-October 2012, across the three agroecological zones of mountains, hills, and terai (). The survey collected information on household characteristics, agricultural practices, maternal and child health and nutrition, food security, and empowerment in agriculture. The WEAI module was administered to the mother of the index child and her husband, or other male primary decision maker if the husband was unavailable.Footnote3 Although autonomy in production is one of the 10 indicators over which empowerment is measured (), if a male or female respondent reported ‘Self’ to the question ‘Who normally takes the decision regarding [agricultural activity]?’ the survey skip pattern instructed the interviewer not to administer the rest of the questions on autonomy to the self-identified sole decision maker. Thus, in households where decision-making is not shared (because of a sole female decision maker) the complete female WEAI cannot be computed, although information in other domains was collected and analysed. (In case of a sole male decision maker, complete information was collected for the spouse.) We discuss the implications for our estimation samples below.

Figure 1. Suaahara baseline survey districts in Nepal

Since our study focuses on women’s empowerment in agriculture, we restrict our analysis to 3,332 out of 4,080 households (82%) where the female WEAI respondent reports working in agriculture as a primary or secondary occupation (). The sample is also characterised by substantial heterogeneity in household type: 834 are sole male decision maker households (type I), with complete female WEAI scores. In Type II households (n = 844), both male and female decision makers are present and have empowerment scores. Owing to extensive male outmigration, consistent with the migration patterns documented in the NDHS 2011 (Ministry of Health and Population [MOHP] Nepal, New ERA, & ICF International Inc., Citation2012), 676 out of 2,383 households do not have a male respondent, but the female respondent does not claim to be the sole decision maker. These households (household type III) – those with a female decision maker, but no coresident male decision maker – have complete female WEAI scores. For the remaining households with female sole decision makers (type IV), the autonomy indicator is missing so we cannot compute the complete WEAI, but we have information on other domains. This implies that we can only test a household bargaining model for households with information on both male and female decision makers (household type II). However, we conduct a more extensive analysis of the other measures of women’s empowerment for the other household types, which is useful because, owing to the context-specificity of gender relations, empowerment in one domain does not imply higher overall empowerment.

Figure 2. Sample sizes by household type

3.2 Sample Characteristics

presents summary statistics for key variables by household type (see Section 4.1 for variable definitions). Overall, mothers consume an average of 3.8 out of 9 food groups, while children consume 3.5 out of 7 food groups. Mothers and children in dual-decision maker households have more diverse diets. Mothers in households where they are the sole decision maker are more likely to have higher body mass index (BMI) but lower dietary diversity compared with other household types. Children’s average z-scores are highest in absent male decision maker households, followed by dual-decision maker households. The prevalence of stunting (44%, HAZ < −2 SD), wasting (13%, WHZ < −2 SD), and underweight (36%, weight-for-age z-score [WAZ] < −2 SD) in our Suaahara estimation sample are all higher than the national average for rural areas (Ministry of Health and Population [MOHP] Nepal, New ERA, & ICF International Inc., Citation2012).

Table 2. Summary statistics by household type

Agriculture in the survey sample is primarily rainfed and subsistence oriented, with about half of the households cultivating fruits and vegetables. Only four per cent of production is sold, while the rest is consumed or stored. The top field crops grown by households include maize, rice, wheat, millet, potatoes, while the top fruits and vegetables include green leafy vegetables, pumpkin/zucchini leaves, green beans, sponge gourds and chilli/garlic. Milk and milk products are the most important animal source foods produced by the household, followed distantly by eggs and meat. Households produce an average of 4.4 food groups, although production appears to be more diverse among dual-decision maker households (4.7), and least diverse in households where women are sole decision makers (3.8).

Women who are sole decision makers appear to be more empowered: they belong to more groups, have more control over income decisions, and spend less time working. Women in other types of households have similar scores for aggregate empowerment, control over income and workload. Women in households where men are sole decision makers are the least likely to be group members, but appear to have greater autonomy in production. On average, the gap between men and women’s empowerment scores is 25 per cent. Dual-decision maker households tend to have more children under two years of age. Women in households without a male decision maker tend to be younger and more educated, while women who are sole decision makers tend to have fewer household members and higher dependency ratios.

4. Empirical Specification

Nutritional status is determined by a complex interaction between individual dietary intake (quantity and quality) and health status, in turn determined by household food security, caring capacity and child care practices, and access to adequate health services and sanitation (UNICEF, Citation1990). We hypothesise that production diversity and women’s empowerment are positively associated with improved dietary practices (for example quality and quantity of diets consumed) and nutritional status.

Because most households in our sample consume what they produce, we expect that mothers and children in households with more diverse production portfolios are also more likely to have diverse diets. Dietary diversity, the most widely used measure of diet quality, has been associated with nutrient adequacy among both women and children (Arimond et al., Citation2010; Ruel, Citation2003; Torheim et al., Citation2004), and with child growth (Arimond & Ruel, Citation2004). Similarly, we expect that women who are empowered in agriculture are able to make decisions that ensure their own and their children’s dietary diversity and nutritional status.

We also test whether women’s empowerment and production diversity have interactive effects beyond the independent additive effects of production diversity and women’s empowerment on nutrition. For example, empowered women in households with more diverse production strategies may have more resources to direct to child nutrition, in which case empowerment enhances the effect of production diversity; conversely, women’s empowerment may be able to mitigate the limiting effects of less diverse production strategies.

To investigate the relationships between nutrition (N), women’s empowerment in agriculture, and diversity in agricultural production, we estimate the following:

One possible source of bias in our analysis is the endogeneity of the empowerment and production diversity measures, which may be affected by the same factors that influence dietary diversity and nutrition status. We attempted to address this issue with standard instrumental variables [IV] techniques using the proportion of sons out of the total number of children and cluster-level distance to markets to identify women’s empowerment, and long run district-level climate averages to identify production diversity. However, the IV diagnostics suggest that the instruments perform unsatisfactorily across different specifications.Footnote4 We therefore estimate EquationEquation (1)(1)

(1) using OLS and interpret our results as correlations rather than causal relationships. We also recognise that household type is endogenous, but similar to production diversity and empowerment, do not have instruments to model selection into household type.Footnote5

4.1 Outcome Variables

Maternal dietary diversity

Mothers’ diet quality is measured using the individual dietary diversity score (Swindale & Bilinsky, Citation2006). We compute individual dietary diversity scores using 24-hour dietary recall data of mothers’ own consumption from nine food groups: starchy staples; beans, legumes, and nuts; dark green leafy vegetables; vitamin A-rich fruits, vegetables, and tubers; other fruits and vegetables; milk and milk products; eggs; fish; and meat (Arimond et al., Citation2010).

Children’s dietary diversity

Dietary diversity of children 6–59 months of age is measured as the number of food groups consumed in the last 24 hours out of seven food groups: grains; pulses; vitamin A-rich fruits and vegetables; other fruits and vegetables; dairy; eggs; and all flesh foods including meat, fish, and poultry.

Maternal BMI

Women’s weight and height measurements are used to derive their BMI, expressed as the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in metres (kg/m2).

Child anthropometry

Trained enumerators took duplicate weight and height/length measurements and obtained information on age of the child in months for all children under 5 years old. Each child’s anthropometric measurements were compared to the 2006 WHO child growth standards reference for his/her age and sex to compute HAZ, WHZ, and WAZ (WHO Citation2006).

4.2 Key Independent Variables

Production diversity

The production diversity index is defined as the number of food groups produced by the household, parallel to the nine food groups used for measuring maternal dietary diversity using 24 hour recall (see above). We expect production diversity to be positively associated with maternal and child nutrition outcomes.

Women’s empowerment in agriculture index

We use six alternative measures of women’s empowerment; five of which rely only on the women’s scores, while the sixth compares the empowerment of men and women within the same household. The first measure is the woman’s aggregate empowerment score, defined as:

Model 1: Aggregate empowerment score: The weighted average of achievements in the 10 indicators () if she is disempowered, and equal to one if she is empowered.

Model 2: Group membership: The number of community social groups where the woman is an active member.

Model 3: Control over income: The number of household agricultural and non-agricultural activities in which the woman has some input in income decisions or feels she can make decisions.

Model 4: Autonomy in production: The woman’s average Relative Autonomy Index [RAI]Footnote6 score over various activities linked to household agricultural production.

Model 5: Workload: The total time spent by the woman in market (paid) and nonmarket (unpaid) activities, including domestic chores and caring for children and the elderly.

Model 6: Gender parity gap: The gap between the man and woman’s empowerment scores, and is equal to zero if the woman is empowered.

In the first four measures, higher numbers imply greater empowerment. For the workload and the gender parity gap indicators, on the other hand, higher numbers imply greater disempowerment. By construction, the workload indicator enters the WEAI negatively; a woman who is overburdened by paid and unpaid work is considered to be disempowered (Alkire et al., Citation2013). We hypothesise that the coefficients on the women’s empowerment measures in Models 1–4 are positive, and those in Models 5–6 are negative. We estimate Models 1–5 for household types with complete female WEAI data, and Model 6 for the subsample of dual-decision maker households. We estimate only Models 2, 3 and 5 for households with the missing female autonomy indicator.

4.3 Controls

We include the following controls in our regressions: child sex, age, age squared, and a dummy for whether the child is under 2 years old; mother’s age, age squared, years of education, and height; household size, dependency ratio (number of household members < 15 and > 64 as a proportion of those of working age [ages 15–64]), socioeconomic status index (measured using principal components analysis of assets and housing characteristics), rainfall and temperature variables, and dummies for household type (for combined samples), caste, intervention/control community, and agroecological zones.

5. Results

Key findings from the OLS regressions are found in –. and present results on maternal dietary diversity and BMI, respectively, presents results on child dietary diversity, and – present results on child anthropometry (HAZ, WHZ, WAZ). Full OLS results for the combined sample with complete female WEAI data are available in the Online Appendix Tables A2–A7.

Table 3. Summary of coefficient estimates: Mother’s dietary diversity, production diversity, women’s empowerment and interactions

Table 4. Summary of coefficient estimates: Mother’s body mass index, production diversity, women’s empowerment and interactions

Table 5. Summary of coefficient estimates: Children’s dietary diversity, production diversity, women’s empowerment and interactions

Table 6. Summary of coefficient estimates: Children’s height-for-age z-score, production diversity, women’s empowerment and interactions

Table 7. Summary of coefficient estimates: Children’s weight-for-height z-score, production diversity, women’s empowerment and interactions

Table 8. Summary of coefficient estimates: Children’s weight-for-age z-score, production diversity, women’s empowerment and interactions

5.1 Production Diversity and Maternal and Child Outcomes

Maternal outcomes

In almost all specifications and subsamples, production diversity is significantly positively correlated with maternal dietary diversity (), but has insignificant associations with maternal BMI in most specifications (). Production diversity is only weakly positively associated with maternal BMI in the specification with control of income (for sole male-decision maker households). However, the negative and significant association of production diversity with maternal BMI in households with female decision makers but absent male decision makers (Model 5) raises the possibility that, in households where labour may be scarce, production diversity may entail higher work intensity, affecting the woman’s nutritional status.

Child outcomes

We also find highly significant positive correlations between production diversity and children’s dietary diversity in households across most household types and the combined samples, except in households where male decision makers are absent (). We find positive, though weaker, correlations between the production diversity and the weight-based measures WHZ () and WAZ (). Production diversity is not a significant correlate of HAZ, with the exception of a weak correlation in the specification using control of income in households with absent male decision makers; this result is likely driving the results for the combined sample.

5.2 Women’s Empowerment and Maternal and Child Outcomes

Maternal outcomes

Different aspects of women’s empowerment matter for maternal nutrition outcomes, with significant associations in household types where women participate in decision-making. Group membership and overall empowerment are positively associated with maternal dietary diversity in shared decision-making households and absent male decision maker households, respectively (), while high workload is negatively associated with maternal BMI in absent male decision maker households (). In the combined sample with complete women’s WEAI data, overall empowerment is positively associated with women’s dietary diversity and BMI; control over income and lower workload is also associated with higher BMI.

Child outcomes

Women’s empowerment appears to have a weaker and more limited influence on child diets and nutritional status in comparison to production diversity. The gender parity gap is weakly significant and negative in the dietary diversity and HAZ regressions, suggesting that children have better diets and long-term nutritional status in households where there is greater equality between women and men. Only control over income is significantly associated with HAZ in dual-decision maker households; mothers with greater control over expenditures are more likely to have children with better long-term nutritional status.

5.3 Interactions between Women’s Empowerment and Production Diversity

Maternal outcomes

In the maternal dietary diversity regression, the interaction term between the aggregate empowerment score and production diversity is significant and negative in absent male decision maker households and the combined sample with complete women’s WEAI data (). The interaction term between the number of groups and production diversity is also negative and significant in the maternal diet diversity regression for dual-decision maker households. This suggests that greater overall empowerment and group membership may mitigate the negative impact of low production diversity on maternal diets. The positive sign of the interaction term with workload (in the sole decision maker and both combined sample regressions) also indicates that greater empowerment (lower workload) mitigates the negative effects of low production diversity; however, this result is inconsistent with the negative coefficient in absent male decision maker households. The workload interactions should be taken with caution, however, because all of them are weakly significant (10%). Only one interaction coefficient is significant in the maternal BMI regression (): the positive and significant coefficient of the workload-production diversity interaction in households with absent male decision makers, the only household type where production diversity is negatively associated with BMI. The sign of the interaction term suggests that higher empowerment (lower workload) would help to offset the negative effects of higher production diversity on BMI in these households where fewer household members are working-age males (11%) compared with male-decision maker (18%) and dual-decision maker households (21%).

Child outcomes

Similar to the maternal outcome regressions, there is indicative evidence that women’s empowerment mitigates the negative impact of less diverse production on child nutrition outcomes. A smaller gender parity gap counteracts the negative impact of lower production diversity on child diets in dual-decision maker households, but lower workloads appear to improve child diets in sole male decision maker households with greater production diversity (). Greater control over income and a lower gender gap offset the negative effects of lower production diversity on child HAZ in dual-decision maker households (). Greater control over income also mitigates the effects of less diverse production portfolios on WHZ and WAZ in female sole decision maker households (–).

6. Discussion and Policy Implications

Our results support the positive associations between production diversity at the household level and maternal and child dietary diversity and WHZ and WAZ, suggesting that policies that promote diversification can improve nutrition for mothers and children. However, the magnitudes of our estimates for the dietary diversity regressions imply that production diversity must increase by at least four food groups to increase dietary diversity by one food group. Our results also suggest that increasing production diversity, if increasing work intensity of women in labour-scarce households, may not necessarily improve maternal BMI.

Aggregate empowerment, group membership, control over income, and hours worked are significantly associated with both maternal dietary diversity and BMI. Control over income and the gender parity gap emerge as significant correlates of child outcomes, particularly for dietary diversity and HAZ. These results suggest that the domains of empowerment that are significant for women and children’s diet and nutrition outcomes may not always overlap. Different aspects of empowerment may be important for different nutrition outcomes, consistent with other findings in the empowerment literature (Kabeer, Citation1999; Sraboni et al., Citation2014).

We also find suggestive evidence that the interactions between production diversity and women’s empowerment are significant. Where significant, the interactions suggest that women’s empowerment has a greater positive effect on child diets and HAZ in households with lower production diversity, that is, women’s empowerment mitigates the negative consequences of less diverse production portfolios. This implies that, in communities where diversification of production portfolios may be limited by biophysical and agroecological characteristics, women’s empowerment may be another avenue for improving child diets and long-term nutritional status. Bundling women’s empowerment interventions with agricultural interventions may make the latter more effective in improving nutrition in households with low production diversity.

Online Appendix.pdf

Download PDF (55.5 KB)Acknowledgements

This work was undertaken as part of the CGIAR Research Program on Agriculture for Nutrition and Health [A4NH]. The authors are grateful to Suaahara (funded by the United States Agency for International Development [USAID] and managed by Save the Children, Nepal) for funding the survey, and to New Era for their capable data collection efforts. USAID supported Kenda Cunningham through Suaahara and Hazel Malapit and Agnes Quisumbing under the Feed the Future program’s partnership with IFPRI on the Women’s Empowerment in Agriculture Index through USAID Grant Number: EEM-G-00-04-00013-00. Support for open access, Suneetha Kadiyala and Parul Tyagi was provided as part of the research generated by the Leveraging Agriculture for Nutrition in South Asia [LANSA], research consortium, and is funded by UK aid from the UK government. Suman Chakrabarti and Wahid Quabili from IFPRI provided excellent research assistance. The authors thank the editors of the special issue, two anonymous referees, Benjamin Davis, therticipants of the ‘Farm Production and Nutrition Workshop’, and others who have provided valuable comments and suggestions. The data and code used in the regressions are available from the authors upon request. The contents are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or offical policies of CGIAR, A4NH, USAID, the US government or the UK government.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. This description draws from Alkire et al. (Citation2013).

2. Empowerment within a domain means that the person has adequate achievements or has achieved adequacy in that domain.

3. Throughout this paper, we refer to women’s and mother’s empowerment interchangeably.

4. The IV results are available upon request.

5. A multinomial probit regression on the probability of the household’s type is presented in the Online Appendix Table A1. While we do not have credible instruments to implement a selectivity correction, we note that, relative to other household types, dual-decision maker households are more likely to have younger and more educated household heads, have more working-age members, belong to the lower caste, and reside closer to markets.

6. The RAI is a measure of autonomy that reflects a person’s ability to act on what he or she values, and probes the person’s own understanding of the situation and how he or she balances different motivations (Alkire, Citation2007).

References

- Alderman, H., Chiappori, P. A., Haddad, L., Hoddinott, J., & Kanbur, R. (1995). Unitary versus collective models of the household: Is it time to shift the burden of proof?. The World Bank Research Observer, 10, 1–19. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/10.1.1

- Alkire, S. (2007). Measuring agency: Issues and possibilities. Indian Journal of Human Development, 1, 169–178.

- Alkire, S., & Foster, J. (2011a). Counting and multidimensional poverty measurement. Journal of Public Economics, 95(7–8), 476–487. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2010.11.006

- Alkire, S., & Foster, J. (2011b). Understandings and misunderstandings of multidimensional poverty measurement. Journal of Economic Inequality, 9, 289–314. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10888-011-9181-4

- Alkire, S., Meinzen-Dick, R., Peterman, A., Quisumbing, A. R., Seymour, G., & Vaz, A. (2013). The women’s empowerment in agriculture index. World Development, 52, 71–91. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.06.007

- Arimond, M., & Ruel, M. T. (2004). Dietary diversity is associated with child nutritional status: Evidence from 11 demographic and health surveys. The Journal of Nutrition, 134, 2579–2585.

- Arimond, M., Wiesmann, D., Becquey, E., Carriquiry, A., Daniels, M. C., Deitchler, M. … Torheim, L. E. (2010). Simple food group diversity indicators predict micronutrient adequacy of women’s diets in 5 diverse, resource-poor settings. The Journal of Nutrition, 140, 2059S–2069S. doi:https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.110.123414

- Cunningham, K., Kadiyala, S., Chakrabarti, S., Malapit, H. J., Menon, P., Singh, K. … Quabili, W.(2013b). Suaahara baseline survey report. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute.

- Cunningham, K., Ruel, M. T., Ferguson, E., & Uauy, R. (2013a). Literature Review on Women’s Empowerment and Child Nutrition in South Asia. Manuscript submitted for publication.

- Doss, C. (2006). The effects of intrahousehold property ownership on expenditure patterns in Ghana. Journal of African Economies, 15, 149–180. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/jae/eji025

- Duflo, E., & Udry, C. (2004). Intrahousehold resource allocation in Cote d’Ivoire: Social norms, separate accounts and consumption choices (Working Paper No. w10498). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Engle, P. L., Menon, P., & Haddad, L. (1997). Care and nutrition: Concepts and measurement. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute.

- Haddad, L., Hoddinott, J., & Alderman, H. (1997). Intrahousehold resource allocation in developing countries: Methods, models, and policy. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Headey, D. D. (2012). Developmental drivers of nutritional change: A cross-country analysis. World Development, 42, 76–88. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2012.07.002

- Hoddinott, J., & Haddad, L. (1995). Does female income share influence household expenditures? Evidence from Côte d’Ivoire. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 57, 77–96. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0084.1995.tb00028.x

- Joshi, N., Agho, K. E., Dibley, M. J., Senarath, U., & Tiwari, K. (2012). Determinants of inappropriate complementary feeding practices in young children in Nepal: Secondary data analysis of demographic and health survey 2006. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 8(Suppl 1), 45–59. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-8709.2011.00384.x

- Kabeer, N. (1999). Resources, agency, achievements: Reflections on the measurement of women’s empowerment. Development and Change, 30, 435–464. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-7660.00125

- Kadiyala, S., Harris, J., Headey, D., Yousef, S., & Gillespie, S. (2014). Agriculture and nutrition in India: Mapping evidence to pathways. Annals of New York Academy of Sciences, Advance online publication. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.12477

- Kilic, T., Palacios-Lopez, A., & Goldstein, M. (2013). Caught in a Productivity Trap: A Distributional Perspective on Gender Differences in Malawian Agriculture (Policy Research Working Paper No. 6381). Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Leroy, J. L., Habicht, J.-P., Gonzalez De Cossio, T., & Ruel, M. T. (2014). Maternal education mitigates the negative effects of higher income on the double burden of child stunting and maternal overweight in rural Mexico. Journal of Nutrition, 144, 765–770. doi:https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.113.188474

- Ministry of Health and Population [MOHP] Nepal, New ERA, & ICF International Inc. (2012). Nepal demographic and health survey (NDHS) 2011. Kathmandu, Nepal: Ministry of Health and Population, New ERA, and ICF International, Calverton, Maryland.

- Nepal Global Health Initiative Strategy (2010). Retrieved from http://www.ghi.gov/documents/organization/158921.pdf.

- Quisumbing, A. R. (2003). Household decisions, gender, and development: A synthesis of recent research. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute.

- Ramalingaswami, V., Jonsson, U., & Rohde, J. (1996). Commentary: The Asian enigma. The progress of nations 1996, Nutrition. New York, NY: United Nations Children’s Fund.

- Reed, B. A., Habicht, J.-P., & Niameogo, C. (1996). The effects of maternal education on child nutritional status depend on socio-environmental conditions. International Journal of Epidemiology, 25, 585–592. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/25.3.585

- Ruel, M. T. (2003). Operationalizing dietary diversity: A review of measurement issues and research priorities. Journal of Nutrition, 133(11 Suppl 2), 3911S–3926S.

- Ruel, M. T., & Alderman, H., Maternal and Child Nutrition Study Group. (2013). Nutrition-sensitive interventions and programmes: How can they help to accelerate progress in improving maternal and child nutrition? The Lancet, 382, 536–551. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60843-0

- Smith, L. C., Ramakrishnan, U., Ndiaye, A., Haddad, L. J., & Martorell, R. (2003). The importance of women’s status for child nutrition in developing countries (Research Report No. 131). Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute.

- Sraboni, E., Malapit, H. J., Quisumbing, A., & Ahmed, A. (2014). Women’s empowerment in agriculture: What role for food security in Bangladesh?. World Development, 61, 11–52. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.03.025

- Swindale, A., & Bilinsky, P.(2006). Household dietary diversity score [HDDS] for measurement of household food access: Indicator guide (v.2). Washington, DC: Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance Project, Academy for Educational Development.

- Torheim, L. E., Ouattara, F., Diarra, M. M., Thiam, F. D., Barikmo, I., Hatløy, A., & Oshaug, A. (2004). Nutrient adequacy and dietary diversity in rural Mali: Association and determinants. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 58, 594–604. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601853

- Udry, C., Hoddinott, J., Alderman, H., & Haddad, L. (1995). Gender differentials in farm productivity: Implications for household efficiency and agricultural policy. Food Policy, 20(5), 407–423. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0306-9192(95)00035-D

- UNICEF. (1990). Strategy for improved nutrition of women and children in developing countries. New York, NY: United Nations Children’s Fund.

- Von Braun, J., & Kennedy, E., (Eds.). (1994). Agricultural commercialization, economic development, and nutrition. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute.

- WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group. (2006). WHO child growth standards: Length/height-for-age, weight-for-age, weight-for-length, weight-for-height and body mass index-for-age: Methods and development. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Yoong, J., Rabinovich, L., & Diepeveen, S. (2012). The impact of economic resource transfers to women versus men: A systematic review (Technical report). London: EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London.