Abstract

Inclusive growth is contested yet adopted by the World Bank to reduce poverty and inequality through rapid economic growth. Research has tested inclusive growth in sectors including agriculture, but few studies apply it to tourism which is significant for many developing countries. The paper interrogates tourism-led inclusive growth: supply chains, economic linkages/leakage, ownership, employment and expenditure. It draws from fieldwork in Vietnam where tourism has rapidly developed with partial economic benefits for local communities, but does not appear to fall within the inclusive growth paradigm. It is unclear if tourism-led growth will become any more inclusive in the short-to-medium term.

1. Introduction

As part of the continuing debate over the complex relationships between economic growth, economic development and how that is transmitted to households (Harrison, Citation2004; Scheyvens, Citation2011), the World Bank, UNDP and other agencies have, since around 2008, been investigating the inclusive growth paradigm. Moreover, it has been adopted by regional development banks such as the African Development Bank and the Asian Development Bank (de Haan & Thorat, Citation2013), large economies (Kannan, Citation2014) and more recently, by small economies such as SIDS (Small Island Developing States) (Tandon, Citation2012) to achieve broad based, equitable growth and development. However, the concept is controversial – it lacks clarity and meaning, yet, it is guiding planning and development policy objectives (Ranieri & Ramos, Citation2013). The breadth of interpretation, whether process-led, outcome-led or both, has offered little or even no explanation of indicators that could measure the distribution and the level of participation in growth across different groups of society (Klasen, Citation2010).

Vietnam presents an interesting case study in which to test inclusive growth because the state, and the ruling Communist Party, while adopting a market-orientated economic policy in the 1980s (Doi Moi), have rejected the ‘liberal traditions’ of governance in the West (Gainsborough, Citation2012). This raises the question of how inclusive growth fits comfortably with the Communist Party’s agenda for growth and development, considering the institutional and social dimensions associated with inclusive growth. In a bid to answer this, the paper focuses on the tourism industry, a ‘private-sector-activity’ (Mitchell, Citation2012) that continues to be seen by many international agencies and developing country governments as an important sector contributing to GDP, employment and government revenues. However, whilst tourism for development has a substantial literature including pro-poor tourism, inclusive growth in relation to tourism is under-theorised. This present paper focuses specifically on the tourism supply chain, the distribution of benefits (not costs) and economic linkages before more briefly examining social aspects. As noted in a recent World Bank study on poverty reduction in Vietnam, ‘measures are needed to make Vietnam’s future economic growth more inclusive’ [and that] ‘support for labor-intensive industries in both formal and informal sectors can also contribute to inclusive growth’ (Kozel, Citation2014, pp. 11–12).

The paper is structured in five main parts. The first section examines inclusive growth as defined by the World Bank, concerns raised about inclusive growth, and some of the challenges of inclusive growth in relation to tourism in a development context. The next section then introduces tourism development in Vietnam and the case study of the iconic UNESCO World Heritage Site of Ha Long Bay. The third section outlines the methodology used within a qualitative approach, before the paper’s central section that reports the findings and discussion. This section discusses the economic dimensions that cumulatively can be seen as ways to test parts of the inclusive growth paradigm, before more briefly considering the institutional and social aspects of possible inclusive growth. The paper ends with a conclusion and recommendations for further research on the possible relationship between aspects of inclusive growth and tourism for development in developing countries.

2. Inclusive growth and international development

This section will first discuss inclusive growth according to the World Bank, then the key concerns raised over inclusive growth, and lastly consider the challenges of inclusive growth in relation to tourism.

2.1. Inclusive growth according to the World Bank

In the past decade, the Asian region has experienced ‘a spectacular decline in the incidence of poverty’ (Ali, Citation2007, p. 1) and rapid economic growth. Yet at the same time, inequality in income, non-income and expenditure has risen significantly for much of the population. This trend is not only seen in Asia but also in other regions experiencing similar economic success, leading international organisations (the World Bank for example) and governments to propose an alternative growth model that addresses the imbalance in wealth creation. The inclusive growth paradigm sits within the sustainable development framework and can be viewed as a process or policy response (Hasmath, Citation2015) as well as a ‘desired outcome’ (George, McGahan, & Prabhu, Citation2012). Hasmath (Citation2015) has argued that inclusive growth has its ‘philosophical roots’ in Sen’s (Citation1992) capabilities approach that emphasised the role of not just economic mechanisms to reduce inequalities but social mechanisms too. Although there is no unified or standard definition of inclusive growth among international organisations (de Haan & Thorat, Citation2013) and others, this World Bank definition has been cited:

[…] inclusive growth analytics has a distinctive character focusing on both the pace and pattern of growth […] Rapid and sustained poverty reduction requires inclusive growth that allows people to contribute to and benefit from economic growth. Rapid pace of growth is unquestionably necessary for substantial poverty reduction, but for this growth to be sustainable in the long run, it should be broad-based across sectors, and inclusive of the large part of the country’s labor force. (World Bank, Citation2009, p. 1)

There is, however, some agreement on what inclusive growth should achieve: namely, a shared approach to economic growth that has fair and equitable outcomes both for lower- and middle-income households (de Haan & Thorat, Citation2013). It is also generally accepted that a rise in employment affects poverty reduction positively as does a rapid pace and pattern of economic growth, as defined by the World Bank among others; and that reference to inequality remains vague in definition and policy-led objectives and outcomes. Therefore, inclusive growth policies should promote a socially inclusive environment for income and non-income growth, which can then affect the broadest section of society, the workforce and industry (Ali, Citation2007; Klasen, Citation2010; World Bank, Citation2009). The notion of inclusive growth builds conceptually from elements of the pro-poor agenda but is seen by the World Bank as being broader and applies to all members of a community, regardless of their circumstances to collaborate in achieving inclusive growth (Ali, Citation2007; Rauniyar & Kanbur, Citation2010).

Despite the ongoing interest of the World Bank, national agencies such as DFID, and other policy-makers in the inclusive growth paradigm, it can be asked whether it is just an update of far older, long-running debates within international development. Saad-Filho (Citation2010) argues that the inclusive growth notion is where the mainstream orthodox – broadly neoclassical – approaches have in effect captured the conceptual ‘high ground’. He contends that ‘the World Bank has conceded nothing of substance either on the content of its preferred policies or on the primacy of growth (rather than distribution) to improve the lot of the poor – only lip service is paid to the significance of equity’ (Saad-Filho, Citation2010, p. 14). Damodaran (Citation2015) uses the metaphor of inclusive growth being a ‘chimera’ of little substance, arguing that it is in effect, a modern re-stating of the old trickle-down notion. The inclusive growth paradigm also raises concern that it is market-driven with no focus on redistribution with the role of the state reduced to facilitator. Practical concerns have also been raised by Hasmath (Citation2015), for example, who questions how measurable objectives might be selected and then met.

While the economy is one obvious dimension of inclusive growth, further dimensions need to be examined to re-address the perceived imbalance of having a focus purely on the economic sphere of activity. This section focuses on two dimensions – institutional and social – in response to the imbalance. Recent literature suggests that institutional dimensions are key to enabling ‘growth coupled with equal opportunities’ (Rauniyar & Kanbur, Citation2009, p. 3) through strong governance and equitable policies. According to de Haan and Thorat (Citation2013, p. 8 citing Addison & Nino-Zarazua, Citation2012), inclusive growth policies must ‘allow people from different groups – gender, ethnicity, religion – and across sectors – agriculture, manufacturing industry, services, to contribute to, and benefit from economic growth.’ However, in much of south and south-east Asia, there are considerable populations living in rural and coastal areas who are under-served and under-represented by institutions of power. Arguably, this is due to market-led reforms that typically favour urban expansion and high productivity industries such as manufacturing and services (Bhanumurthy, Citation2014). This has led to a rise in inequality in countries such as India, and particularly in rural areas, where access to education, and health and gender equality remains stubbornly low. According to Balakrishnan et al. (Citation2013, pp. 7–8), social and institutional barriers obstruct inclusive growth in India due to inequalities associated with identity (gender and caste), the underdevelopment of financial systems for the poor, unbalanced regional development and ‘fiscal redistribution’. Although evidence shows poverty reduction and inequality has fallen in some regions of India, the centralised planning apparatus has resulted in ‘preferential policies as well as persistent disparities in human capital and infrastructure’ (Fan, Kanbur, & Zhang, Citation2009 cited in Balakrishnan et al., Citation2013). Kundu (Citation2015) argues for policy prescription at ‘state and lower levels’ to effectively reduce distribution bias and income inequality between the core (urban, service sector, high human capital) and peripheral (rural, agriculture sector, lower human capital) regions. The imbalance affects more than 50 per cent of the total workforce, and according to Bhanumurthy (Citation2014, p. 4), this ‘hamper[s] the long term potential growth’ of agriculture; an industry with important forward linkages. In this case, the core participants and beneficiaries of growth are not ‘inclusive of the large part of a country’s labor force’ nor ‘broad-based across sectors’ (World Bank, 2009). Therefore, the need arises for an ‘explicit link between improved participation and benefit-sharing’ in policy (CAFOD, Citation2014) that mobilises the workforce through modern, appropriate infrastructure and rural development (Ali & Yao, Citation2004; Fernando, Citation2008; Rauniyar & Kanbur, Citation2010); fiscal policy (Heshmati, Kim, & Park, Citation2014) and ‘good’ governance (CAFOD, Citation2014). In south-east Asia, social protection schemes and public works programmes are common and designed to reduce poverty levels, yet according to Roelen (Citation2014), these initiatives, which are often very comprehensive, are not co-ordinated well and rely too much on individual responsibility. In addition, the assets of the poorest are cumulatively small and not sustainable, yet access to small loans and formal banking is weak. These structural barriers ultimately prevent the poorest from escaping poverty and being able to participate in inclusive growth, leading ‘to the perpetuation and reinforcement of patterns of disadvantage and inequality’ (Roelen, Citation2014, p. 60).

In the case of Vietnam, market-led reforms have led to ‘“money politics” and the resulting commercialisation of the state’ (Gainsborough, Citation2012, p. 39). Since the 1990s, inequality in income and land ownership has risen, the state has advanced and a political culture of nepotism and elitism has ensured ever-tighter ties with business, especially the new conglomerates. The opportunity to participate in, and fully benefit from, the growth process is severely limited to those with connections and good relationships with party and state officials (Gainsborough, Citation2012, p. 39). There is evidence that certain sectors are adopting inclusive growth principles, most notably social protection schemes including credit access programmes and health insurance cards (Roelen, Citation2014); however, this change does not imply that the Vietnamese state is adopting a more neo-liberal approach to governance (Gainsborough, Citation2010). Rather, it is attempting to decentralise some responsibility. Painter (Citation2008, p. 79) notes, however, that the decentralisation efforts are the ‘by-product of marketization, rather than part of a process of deliberate state restructuring’. This potentially leads to ‘significant fragmentation of the state, a high potential for informalisation and corruption’ (p. 79) and raises the question of how inclusive growth can be realistically implemented in Vietnam under its current institutional and political framework.

2.2. Challenges of inclusive growth for tourism

Unlike some other economic sectors that can be easily classified using standard international industrial categories, tourism is a diffuse and multiple industry consisting of closely associated and interacting segments such as transportation (both international and domestic); accommodation; intermediaries such as tour operators and travel agents; catering services; retail such as souvenirs; local attractions and activities; vehicle rental and so forth. Given this diffuse characteristic, tourism is perhaps better described as a group of industries. That noted, tourism, particularly, international tourism, remains a policy favourite of many developing country governments as it is seen to drive economic growth.

Although there has been discussion within the international development community around the pro-poor tourism notion (see Gascón, Citation2015; Harrison, Citation2008; Torres & Momsen, Citation2004), inclusive growth has been little studied in the context of the tourism industry (apart from work by Butler & Rogerson, Citation2016; on South Africa; Hampton & Jeyacheya, Citation2013, on the Seychelles; and Jones, Citation2013, on Nepal). This is despite tourism’s contribution to many developing countries’ local economies and employment, and the role of the potentially important forward linkages for the agriculture sector. Where local communities become suppliers of tourist products (accommodation, food and beverage, transport, guiding services), backward and forward linkages are generated. This can expand the local supply chain and stimulate further local innovation and new businesses in tourism (for example restaurants, shops, internet cafes), particularly among low- and middle-income groups. Research from South Africa (Pillay & Rogerson, Citation2013); Kenya (Mshenga & Richardson, Citation2013); Malaysia (Daldeniz & Hampton, Citation2013) and Indonesia (Graci, Citation2013; Hampton & Jeyacheya, Citation2015) for example, discuss coastal communities who exploited the more lucrative tourism market over increasingly dwindling traditional livelihoods. For example, fishing communities employed their skills, knowledge and equipment to offer fishing trips, diving expeditions, snorkelling tours and water taxi services to tourists. In other cases, small land-based businesses were established such as guest houses, small shops or restaurants, often in in private dwellings where one room could be made available for business use. This frugal innovation of existing skills and knowledge into small tourism businesses seems to be supported by, or at least not hindered by, economic, institutional or social dimensions.

In cases where support is limited or not evident, the local tourism supply chain can be severely impacted, for example; a combination of fiscal and economic policy reforms in the Seychelles has led to a dysfunctional local supply chain, disempowered local businesses and disenfranchised tourism graduates (Lee, Hampton, & Jeyacheya, Citation2015). There appears to be little opportunity for frugal innovation to exist or for agriculture to exploit potential forward linkages, as the country shifts to an import-led economy. This scenario is contrary to inclusive growth which should ‘diminish trade-offs between growth and inequality [so] the poor become enfranchised as customers, employees, owners, suppliers, and community members’ (George et al., Citation2012, p. 662).

In the context of tourism, these trade-offs are more likely to increase given three conditions: first, where there are weak governance structures and public institutions (Hall, Matos, Sheehan, & Silvestre, Citation2012); second, where ownership and power has shifted out of local control (Hampton & Jeyacheya, Citation2015); and third, where access to employment is limited or exclusive (Ali & Son, Citation2007). This together suggests that for tourism growth to be inclusive there must be a ‘level political playing field’ (Lin, Citation2004; Ruaniyar and Kanbur, Citation2009) that ‘facilitate[s] the full participation of those less well off’ (Ali & Son, Citation2007, p. 12) and under-represented. It also suggests that an increase in trade-offs will erode and weaken social networks, and particularly those associated with micro-enterprises and small businesses (CAFOD, Citation2014).

3. Tourism in Vietnam

Vietnam has a population of more than 90 million, GDP of $186.2 billion in 2014 (World Bank data) and an area of 332,000 square kilometres along a coastline of 3440 kilometres. Tourism has become a strategic industry in Vietnam and in 2014 it contributed in total around 9.3 per cent of GDP and directly employed 3.7 per cent of the labour force (WTTC, Citation2015) becoming the ‘centrepiece’ (Gillen, Citation2014) of the Vietnamese economy.

Vietnam was one of 10 countries with the fastest tourism recovery growth rates after the global financial crisis of 2008–2009 (UN WTO data). In 2014, Vietnam welcomed 7.8 million international visitors and had 38.5 million domestic visitors (Ministry of Culture, Sport and Tourism, Citation2014). In 2013, the tourist infrastructure was further enhanced with the opening of various large new four to five star resorts and hotels. Tourism accommodation capacity in Vietnam covers the whole spectrum of standards from backpackers to luxury resorts.

Ha Long Bay – consisting of approximately 1969 karst limestone islands covered in dense vegetation – is located in Quang Ninh province on the north east coast, 160 km from Hanoi (Mark, Citation2009). Since Vietnam opened up to international tourism in early 1990s under Doi Moi, Ha Long Bay has been one of Vietnam’s most important sites, both economically and culturally, and is one of the country’s premier tourism destinations receiving around 3.1 million visitors in 2012. It plays a significant role in Vietnam’s development as a tourism destination with a major portion of the bay declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1994 (Mark, Citation2009).

Regarding how tourism is organised, at national level, tourism strategy is the responsibility of the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism in Hanoi; whereas tourism planning and international marketing is undertaken by the Vietnam National Administration of Tourism (VNAT). At provincial level, each PPC (Provincial People’s Committee) is responsible for their own tourism department. In Quang Ninh province, given Ha Long Bay’s UNESCO status, the PPC established a World Heritage Site Management Board to coordinate site management between provincial government, local businesses, local inhabitants and other stakeholders. As well as tourism, Quang Ninh province is a key part of the northern economic triangle, and also hosts Vietnam’s major coal mines, as well as fishing and shipping industries (Lloyd & Morgan, Citation2008).

Unlike other coastal destinations in south-east Asia, tourists in Ha Long Bay typically stay for a short visit of one to two days, which has implications for possibilities of tourism-driven inclusive growth. The Quang Ninh provincial government has improved infrastructure and recreational facilities to encourage longer stays and has actively encouraged the sector’s development (Quang Ninh PPC, Citation2014). In 1990, Ha Long Bay had 14 hotels with 245 rooms, but by 2000, 90 hotels with 1800 rooms (World Bank, Citation2012). Data from 2011 shows further growth to 466 hotels and guesthouses with 7883 rooms, however – and unusually for a destination – around 25 per cent of Ha Long’s total accommodation capacity is on boats (Quang Ninh Departments of Culture, Sport and Tourism, 2011; Quang Ninh PPC (Provincial People’s Committee) and Quang Ninh Department of Sports, Culture and Tourism, Citation2014).

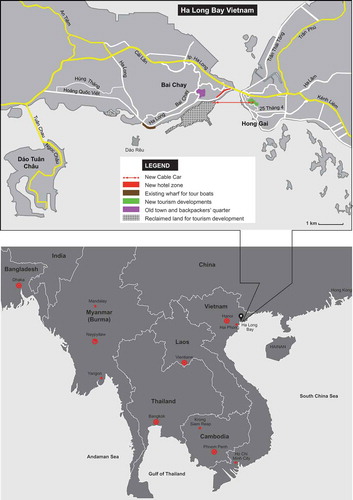

Most tourist facilities (accommodation, restaurants and so forth) are located in the Bai Chay district of Ha Long city, across the river mouth from Hong Gai (the main commercial district). Bai Chay comprises two identifiable, adjacent tourist zones: the main coastal development of larger hotels running parallel to the coast, and an inland area consisting smaller budget hotels and guesthouses for backpackers and domestic tourists (). Most of the large-scale hotels were built in the 2000s and many accommodation owners originate from outside of Ha Long City.

More recently, along the seafront is a major multi-million dollar development and land reclamation with a new cable car project, artificial beaches and new tourism accommodation including hotels and retail, and a new ‘six star’ luxury hotel being built on a small islet. This new sizeable development led by Vietnamese conglomerate firms operating at the very largest scale, raises questions about whether the local population will experience inclusive growth from tourism. We will return to this.

Other parts of the city also contain hotels and guesthouses, particularly along the highway at the city’s western margins. Also westwards of Bai Chay is the new Tuan Chau island marina, port and hotel development. The water-based component of Ha Long Bay tourism consists of small day boats – which tend to be family-owned small business servicing domestic tourists and backpackers – and the larger, more luxurious night boats that moor overnight in the islands mainly serving international tourists and wealthier domestic visitors. Cruise ship tourism is also growing with around 20 operators including Royal Caribbean and P&O. Although there are restrictions on ship size and therefore passenger numbers, cruise ship numbers doubled over 2010–2015 with more than 500 ships visiting annually (Respondent 3, local tourism college lecturer).

4. Methodology

This paper draws upon a funded international research project between Vietnamese and British universities that examined the socio-economic impacts of coastal tourism in Ha Long Bay. Field research was carried out over two visits with an initial scoping study during peak international tourism season (March) and the main fieldwork took place at the end of the international tourism season/start of the domestic tourism season (May). The approach selected was qualitative using insights from rapid appraisal type techniques (Chambers, Citation1983; Ellis & Sheridan, Citation2014). Given the research focus to interrogate tourism within inclusive growth, the respondents were predominantly from the tourism sector and government. Twenty-five in-depth, semi-structured interviews were undertaken with key informants from across the tourism industry and government officers from the province’s Department of Sport, Culture and Tourism and the World Heritage Site Management Board, as well as a senior official from VNAT in Hanoi. Average interview duration was one hour, often located in the place of work but some interviews were held in tea shops and other more informal venues following some respondents’ requests for a measure of privacy away from their workplace or government office. Each interview was administered by two researchers and conducted in either English or Vietnamese. The responses were recorded in notebooks by both researchers. Where interviews were conducted in Vietnamese, the responses were translated to English immediately after each question, allowing for clarification and follow-up questions. A debrief meeting was held at the end of each day with all researchers to discuss and cross-check the completed interviews.

Interview respondents were purposely sampled with further ‘snowballing’ to elicit other possible respondents. The Vietnamese team members were both from the Quang Ninh province and so provided local knowledge of Ha Long Bay as well as interview translation. Interview protocols were developed by the academic leads and then once agreed, translated into Vietnamese so that respondents who lacked sufficient English could be interviewed in the Vietnamese language. Only two interviews were digitally recorded as most who took part were uncomfortable with this and so extensive field notes were taken and typed up while still in the field. Interviews were then manually coded thematically and then analysed after team discussions.

5. Findings and discussion

The findings from Ha Long Bay represent a range of stakeholders whose businesses and livelihoods are impacted by the existing tourism industry and the ongoing tourism development ().

Table 1. Details of n = 25 respondents interviewed

From this sample, a rich narrative of experiences, opinions and perceptions was analysed to begin to test aspects of the inclusive growth concept. The economic dimensions of tourism in relation to inclusive growth will be discussed first before the paper examines institutional and social dimensions.

5.1. Economic dimensions: identifying key factors

This section begins by discussing the existing supply chain and backward linkages, before considering business ownership and economic leakage, employment patterns and tourist expenditure within Ha Long Bay’s tourism industry.

5.1.1. Supply chain and backward linkages

Respondents from the accommodation and food and beverage sectors represented six small, local businesses and six large businesses (national and local, sole business and part of a national chain), with all but one operating in the Bai Chay area of Ha Long Bay. Analysis showed that the local supply chain had strong backward linkages to the fishing sector but weaker backward linkages to agriculture in the province. illustrates the tourism supply chain and distinguishes between small and large businesses.

Small businesses in Ha Long Bay typically sourced from local markets for rice and fish, directly from fishermen and through local wholesalers (for alcohol and all non-perishable goods and services). Although larger businesses and chains also sourced regularly from the local supply chain, particularly fish and seasonal fruit/vegetables, their main supplier was Vietnam’s principal grocery wholesaler, Metro Cash and Carry (Metro C & C). The reasons given by these respondents [4, 13, 20, 22] for choosing the local supply chain were linked to freshness and quality of perishable products; however, the wholesaler offered higher quality products that were in greater and more regular supply and consistent quality. Interestingly, Cadilhon et al. (Citation2006, p. 33) commented on the fresh food sector as a ‘barrier[s] to the advancement of the modern retail sector’ in Vietnam because of cultural values. Food that has been chilled or frozen is considered ‘unfresh’ leaving only that which is ‘as close as possible to the live animal or plant’ as ‘fresh’. This cultural norm may sustain local suppliers and wholesalers in Ha Long Bay and could in fact stimulate backward and forward linkages for farming and fishing communities.

Metro C & C’s role in the hospitality and catering supply chain in Vietnam was observed by Cadilhon and Fearne (Citation2005) with an example highlighting the close relationship between the Metro branch in Ho Chi Minh City and a large five star hotel. (In Ha Long Bay, the research team observed regular deliveries from Metro trucks to several catering and accommodation establishments as we undertook fieldwork in Bai Chay). Cadilhon et al. (Citation2006, p. 33) note the rise of Metro in Vietnam and its emphasis on providing quality, fresh food sourced from ‘regular farmer-suppliers’; however it has a relationship with small local suppliers but only for ‘occasional deliveries’.

In terms of the local food supply chain, the province supplied chicken, pork, seafood (shellfish, squid, octopus), rice, and some fruit (pineapples, mangoes, oranges and lemons in season) but much fruit was sourced from the south of Vietnam, along with coffee from the central highlands. Although beer is brewed in the province and could be supplied to tourists, national brands such as Hanoi Beer or Saigon Beer predominated. The national brands were purchased from wholesalers for the tourism sector, alongside licenced international brands such as Heineken and Tiger.

Other backwards linkages were also explored such as possible use of local suppliers for furniture and fittings, kitchen and other catering equipment, crockery, cutlery, linens and other textiles. From this small sample of businesses, broad trends were visible such that local supply from the province was limited to some bespoke wooden furniture for typically smaller establishments, but the majority of kitchen equipment, appliances and furniture such as tables and chairs were supplied by Hanoi’s specialist distributors. This suggests weak backward linkages to other sectors that could, in theory, supply some of the non-food requirements of the tourism industry. However, regional social and economic policy that sustains and broadens existing access and opportunity to the growing tourism market needs to be strengthened so that local suppliers and producers can sustain and grow their businesses. The current trend suggests that opportunities for socially-inclusive growth have been missed as emphasis is placed on rapid tourism development and economic growth.

5.1.2. Ownership patterns and economic leakage

Small businesses operating in the formal and informal sectors are fundamental for inclusive growth because they sustain the livelihoods and communities of those typically under-represented in government policies (CAFOD, Citation2014): that is, poor, marginalised and rural communities. In our study, the small tourism operators running guest houses and restaurants were former local fisherfolk who had chosen tourism as an alternative livelihood because it offered more financial and social security for their families, particularly education, access to clean water, electricity and so forth. All small businesses were established in the early stages of (Doi Moi) tourism growth in Ha Long Bay, taking advantage of the backpacker and domestic tourism markets. This group of ‘frugal innovators’ pioneered tourism development in Bai Chay and owned their businesses and in many cases, the premises. Whether boat or building, the property typically doubled up as a business and a home, which was financed through personal savings. As noted earlier, the local supply chain is vital to small businesses, however, with no data available showing expenditure multipliers for example, it is difficult to understand its value (and potential loss, if development excludes micro and small tourism businesses).

By comparison, ownership of existing large tourism businesses was dominated by national companies. This was evident across a range of tourism services including tour operators (Saigon Travel), three to five star accommodation (Muong Thanh Hospitality), luxury cruise operators (Syrena) and food and beverages sectors, including chains (My Way Hospitality JSC) and wholesale (Metro). Unlike other developing countries’ coastal resorts, there was little obvious international ownership of business, with the sole exception in the hotel sector being the four star Novotel. The reason for this, according to one hotel manager, was because the destination did not yet attract sufficient numbers of high paying guests. This is expected to change however, as modern purpose-built entertainment and retail units coupled with a new faster highway are completed, attracting international investment from global hotel and resort chains such as Hilton [Manager, VNAT (2)].

As previously mentioned, the supply chains of large and international businesses are extended and often managed centrally; therefore, as Ha Long Bay develops and attracts high-end visitors, economic leakage from the area is expected to rise. During the fieldwork (May 2015) there was an observable shift away from local and provincial business ownership to major national firms headquartered in Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City, and a number of joint ventures between significant national and foreign investors, developers and architects (). It became clear from observations and interviews that unless policies were implemented to safeguard and promote the local supply chain and small businesses, the loss to the local economy through weakening backward and forward linkages could be significant. This is discussed in further detail under institutional and social dimensions.

Table 2. Tourism development projects in Ha Long Bay, Quang Ninh Province 2015

5.1.3. Employment patterns

Local employment is one of the main economic aspects needing consideration within the inclusive growth concept, however, employment creation by itself does not necessarily lead to equitable employment and growth opportunities unless there is a supporting strategic plan in place to prioritise and support a broad-based demographic (Samans, Blanke, Corrigan, & Drzeniek, Citation2015). Furthermore, and to differentiate from pro-poor strategies, inclusive growth promotes productive employment opportunities rather than broadening income distribution (Bakker & Messerli, Citation2016) to reduce or avoid poverty.

Research in Ha Long Bay strongly suggests that employment strategies for the tourism industry (from government) are extremely weak; but employment strategies of individual tourism businesses are collectively stronger. Employment strategies of interest to this research included hiring processes, training opportunities such as specialist colleges and on-site training, and employment outcomes. In Ha Long Bay respondents from large businesses (such as the major hotels, upmarket restaurants, large tour operators and night boat businesses) and the provincial government emphasised that human resources were a key barrier to employing locals. From the sample, common challenges included a lack of vocational training or technical experience, and limited soft skills. This led to in-house training becoming the standard operating procedure for large firms, with some employing training managers, and one large tour operator running their own training school. Individual business strategies for employment were broadly divided between those preferring not to employ local people – ‘not because we can’t recruit locally but our policy is to recruit like a blank paper in the remote mountainous areas. We can train them how to be good staff from the beginning.’ [Owner of high-end restaurant (22)] – and those preferring local employees because ‘[they] have more time for tourists; more time to devote to the company’ [Director, major tour operator (1)] and ‘better knowledge of Ha Long Bay’ [Owner, small travel agent (10)]. Furthermore, people from outside the area had ‘different habit[s] and different ways of living’ [Manager, national coffee shop chain (4)] and expected higher salaries to cover rent and other ‘away from home’ living expenses [Owner, small travel agent (10)].

For the smaller businesses in the sample such as budget hotels and small informal restaurants catering to backpackers and domestic tourists, typically employment was of local people or family members, a finding that concurs with earlier research elsewhere in south-east Asia (Ashley, Citation2006; Cohen, Citation1982; Hampton, Citation2013) as well as other studies on Ha Long (see Nguyen, Rahtz, & Shultz, Citation2014 on employment opportunities from tourism and local perceptions, and Long, Citation2012). During peak tourist seasons, additional staff were employed temporarily from either the extended family or the local community.

The existence of alternative, well-paid employment in the coal mining industry complicates matters further. One interviewee said: ‘People don’t want to work in tourism even those with a good education because the salary is low so people who live here try to find a way out.’ [Manager VNAT (2)].

Overall, results broadly show that large businesses have internal human resource strategies that prioritise skills-based training for employees, many of whom are local or marginalised. This suggests that employment across large tourism firms is broadly inclusive; however, this is not driven by government policy, but by the tourism industry itself. The long-term implications are unknown, but the future demand for employment in tourism is expected to be high considering the extensive tourism projects under construction, and growing interest from major international hotel and retail operators. In light of this, the lack of a centralised framework for equitable and productive employment in Ha Long Bay’s tourism industry may fuel disparities in income and non-income generation and benefits.

5.1.4. Tourist expenditure

In spite of the significant annual arrivals to Ha Long Bay, the contribution of tourism to regional GDP is not fully known, but two respondents [Manager, VNAT (2); Project Engineeer, Transport Department (18)] working in the provincial government cited figures of between 5 per cent and 15 per cent. The interviews did not ask directly about tourist spend, but data from the Tourism Master Plan (Quang Ninh PPC (Provincial People’s Committee) and Quang Ninh Department of Sports, Culture and Tourism, Citation2014) suggests that international tourist spend in 2012 was an estimated $55 per visit whereas domestic tourist spend was only $14 (a low figure compounded by the fact that most domestic tourists were daytrip visitors who did not stay overnight stay in Ha Long Bay). The figure was adjusted by Respondent 2 (Manager, VNAT) who noted that $32 was a more realistic estimate for domestic tourists in 2015. When combined with average length of stay data, this shows that tourist expenditure is seriously affected by the characteristics of the main attraction – the limestone island seascape – and the fact that once seen, there is little else to retain tourists (and their spending) in Ha Long city. This indicates that the primary tourist spend is primarily in and around the World Heritage Site where a fixed entrance fee to the UNESCO site (VND 120,000 ($5.00) plus the cost of a boat tour is guaranteed (a basic three-hour boat tour costs VND 100,000 [$4.50]). The total contribution of tourist spend from entrance fees and boat tours is likely to be significant; however, there is no certainty that this expenditure remains in the local area. This is partly due to the specifics of how tourism has developed there, particularly the high proportion of tourists purchasing their day or overnight tours in Hanoi rather than in Ha Long itself. Tourists buy tour packages through one of the many operators or hotels and although the exact proportion is unknown, it is likely to be very high considering the proportion of day visitors. Similarly, the retained contribution from cruise ship passengers is also likely to be negligible as bookings are normally arranged through large tour operators in Hanoi or Ho Chi Minh City. Finally, the large domestic tourist market is decreasing, according to the owner of a small guest house [9], because there is no incentive to re-visit the bay.

More recently, and in a bid to diversify the tourism economy, the MICE (meetings/incentives/conference/exhibitions) and gaming sectors have begun to contribute to tourism spend. Although data is not disaggregated enough to illustrate the true value of these sectors, it is clear that the geopolitical dispute with China over territory is affecting spend in casinos. Hoang Gai International JVC, a Taiwan/Vietnam joint venture also involved in developing Reu Island into a tourist resort, announced losses of VND44 billion ($1.9 million) from its casino, the Hoang Gia Ha Long (Vietnamnet, Citation2015). The loss was primarily attributed to the declining Chinese market.

Ownership from outside the province, as noted earlier, means that the tourist expenditure is likely to show a high level of economic leakage. Data on expenditure multipliers through the local/provincial economies – as in many developing countries – is unfortunately unavailable but it is suspected to be relatively low given the supply chain issues and relatively weak backward linkages and reliance on supplies transported from outside the province.

5.2. Institutional and social dimensions

Inclusive growth requires an open and transparent approach to governance with strategic policy-making that includes the broadest section of society. The field research suggests that the public sector suffers problems, particularly ‘structural weaknesses’ and reinforces the findings of Hildebrandt & Isaac (Citation2015, p. 14) including ‘institutional rigidities, lengthy and complicated decision-making processes, overlapping responsibilities and lack of market proximity’. Furthermore, evidence suggests ‘government indifference and corruption, lack of involvement of locals in planning and the fact that most promoters of tourism tend to be large non-local concerns’ (Suntikul et al., Citation2010, p. 206) adding further complexity to testing inclusive growth around tourism in Ha Long Bay.

5.2.1. Institutional and institutionalised networks

Institutional networks in Vietnam appear to be vertical rather than horizontal. Our study found several examples that support Hildebrandt and Isaac’s (Citation2015) research and suggests that structural weaknesses restrict opportunities for inclusive growth. The larger tourism businesses, as expected (and confirming findings from other developing country destinations), were seen to have a strong relationship with both provincial and central government and the provincial Management Board for Ha Long Bay, compared with smaller businesses. These relationships were deemed crucial for businesses to fast-track employment permits [Owner, small travel agent (10)], to hold meetings with officials [Director, large hotel (20)], and to take advantage of the new development opportunities for existing businesses [Owner, small souvenir shop (17)]; in other words, a strong alliance avoids similar challenges as noted by Hildebrandt & Isaac (Citation2015).

The small business owners and those excluded from this elite network experience a more uncertain outcome because of government indifference and lack of involvement in planning and development. One respondent [17] who was a trader at the night market from 1999 until 2015 (and now has a souvenir shop) explained: ‘It’s been difficult because the night market has been moved four times in the past two years, so we have to move all the time. We were given one-month notice to move but have a one-year contract, so contract is broken. People were very angry with changes. They talked to the management team [of the night market], then PPC [Provincial People’s Committee], then the Provincial Communist Party Committee, but nothing changed and no one listened.’ Her hope was that people with small businesses like hers will be given the opportunity to be involved in the new projects. She hoped that they will be asked before others but she was pessimistic because she has ‘no relationship with government.’ In this case, under-representation of local businesses in the future development of their area is an obvious barrier to inclusive growth. This leads to the second point.

5.2.2. Local participation and collaboration

A second factor is local participation and collaboration in policy and planning which was non-existent unless a relationship was secured with key individuals. The impact on local business owners has increased uncertainty about their future and eroding trust towards the government – ‘Local people are very disappointed with government. They are not consulted on new projects. Just rumours.’ [Manager, small local hotel (16)] – and to a lesser extent, large tourism businesses – ‘The problem is the businesses and the PPC [Provincial People’s Committee] don’t have the same voice. Businesses are not working properly with PPC. Ha Long tourism is not in good condition – it is incoherent’ [Director, local luxury cruise operator (13)]. Thus, despite new policies being drafted, the complex policy-making environment means that small businesses for example, are unaware of agreements with the owners of Tuan Chau Island to charge ‘no tax, no fees in the first two years, and then in the third year, some rental – maximum 15 per cent of market rate – a suitable price for small businesses’ [Regional Head, Department Sport, Culture and Tourism (21)]. The institutional weaknesses noted in Ha Long Bay reflect those at state level as mentioned earlier (Roelen, Citation2014), and this seems to be reinforcing social exclusion and income inequality that already exists.

6. Conclusion

Inclusive growth, as perceived by the World Bank and other agencies, at first sight appears to be a promising concept to explore for low-income countries. However, the inclusive growth paradigm remains somewhat controversial and appears to be located conceptually within an orthodox growth/neoclassical mode of analysis (Saad-Filho, Citation2010). This present paper has contributed to the ongoing debate on inequality and development by beginning to test the parts of the inclusive growth concept in the specific situation of the tourism industry in Vietnam, a rapidly developing country. Given tourism’s increasing importance to Vietnam for employment creation, contribution to GDP and government revenues, the paper examined tourism in relation to inclusive growth using the country’s leading destination, Ha Long Bay, to explore possible indicators.

The inclusive growth concept is seen to have three main dimensions: economic, institutional and social, although clearly, these three have some overlap. Regarding the economic aspect, Ha Long Bay demonstrated some positive impacts for the host population and local economy, but the overall picture is less clear with some variability across different aspects. The study found some local economic linkages, particularly in the food supply chain with possibilities for further strengthening and opportunities for local agriculture, but also found weak backward linkages in non-food items such as furniture, fittings and equipment. Scale becomes of interest here, as small locally-owned businesses (typically a key component of inclusive growth) had lower leakages than larger tourism operations which were typically owed by outsiders and national Vietnamese companies, often conglomerates. It is recognised that the lack of expenditure multiplier data is a limitation here but future research could shed further light on small business (both formal and informal) and the local supply chain for tourism.

The key issues around tourist expenditure concern the generally low average daily spend of only $55 for international tourists and $14 for domestic visitors (Quang Ninh PPC [Provincial People’s Committee] and Quang Ninh Department of Sports, Culture and Tourism, 2014). This was due to the high proportion of day trip visitors who typically spend less than overnight visitors once accommodation is stripped out; the dominance of package tours by externally owed firms (tour operators often based in Hanoi) so that tourists prepaid and had little expenditure in Ha Long; and similarly, the growing cruise ship sector whose passengers also have limited spend (a common problem also in many Small Island Developing States, especially in the Caribbean). Together, these characteristics of tourism in Ha Long Bay exhibit low visitor expenditure in the destination itself.

For employment, another key aspect of inclusive growth, the study found that scale was also significant. Many larger scale tourism businesses such as big hotels and restaurants typically employed staff from outside the province, although other large firms preferred local employees. Common to all of the respondents from larger firms though was a concern over the lack of skills and the need for training – an aspect of inclusive growth also noted in the World Bank report (Kozel, Citation2014, p. 12). It was noticeable that larger tourism businesses were taking the lead by providing human resource development and staff training. Smaller businesses, typically orientated to serving backpackers and domestic tourists, perhaps unsurprisingly tended to employ local people but, as with the larger firms, also faced competition for staff from other sectors especially the well-paid coal mining sector.

The combination of weak backwards linkages and significant economic leakage, in concert with low tourist expenditure, raises questions over the economic aspect of inclusive growth from tourism. The issue of employment, however, was less clear, with tourism remaining a useful source of employment for local people, particularly in small-scale businesses. At the same time, there was a noticeable trend to employ workers from outside the province, even for unskilled work such as construction labour where work gangs were brought in from other provinces. Also, tourism continues to compete for employees with other, better paid, sectors in the province such as coal mining.

Regarding the medium-term picture, the study found some indications of the ‘direction of travel’ of the overall tourist economy in Ha Long Bay for the next few years with very large linear development of capital intensive resorts and infrastructure being constructed stretching over nearly four kilometres along the Bai Chay tourist zone. This would suggest worsening inclusive growth opportunities for local households from middle incomes through to the lowest quartile given this type of luxury tourism’s weak economic linkages and high leakages to firms owned outside the province. However, pockets of possibility for inclusive growth remain, such as the existing low budget domestic tourist and backpacker area along with the small shops, restaurants and the informal sector such as souvenir hawkers. This could be further developed and could start to increase incomes meeting a need identified in Galla’s study (Citation2002, p. 67). However, such a focus requires political will, and despite official rhetoric about economic development for Ha Long residents, it is unclear whether there is any meaningful or effective government support for small tourism businesses as opposed to the large string of capital intensive developments and resorts presently under construction. It is clear that opportunities for local residents and small businesses to participate and contribute to development plans is severely limited – this being a crucial component of inclusive growth.

Concerning the institutional and social dimension of inclusive growth, the study found that relationships were emphasised by respondents and showed that lacking close-knit business and political networks could be potentially harmful and reduce opportunities for inclusive growth. Without such networks it was difficult for some to participate in tourism fully. Social capital was high among those in the tourist zone, but in comparison to that of the larger tourism businesses, it was insignificant. Networks at the higher end with regional or national government officials or wealthy individuals was a reason given – quite openly – by many, without much comment as if it was unremarkable. This links to the broader context, that is Vietnam’s political economy as a country in transition, and especially the tight nexus between Provincial People’s Committee, the central government in Hanoi and the biggest tourism businesses such as the conglomerates constructing and operating large hotels, resorts, the new marina and harbour at Tuan Chau island, the sizeable cable car and so forth. This also needs to be seen in light of the growing political role of tourism in nation-building in Vietnam as in other developing countries (Lloyd, Citation2004). Gillen (Citation2014, p. 1318) observed that ‘tourism is an important and still unfolding currency for the [Vietnamese Communist] Party’.

In terms of governance of tourism, and associated with the previous point, many respondents also commented on the lack of transparency. This reinforced the findings of the World Bank study: ‘Improving governance through greater transparency and accountability will help to increase local participation and reduce existing inequalities in voice and power that work to undermine inclusive growth’ (Kozel, Citation2014, p. 12). Our study’s findings suggested that while new governance structures have been created (such as the Ha Long Bay Management Board) in an attempt to coordinate different stakeholder groups, policy implementation remains somewhat patchy, for example over the continuing problems of pollution and waste management in the bay.

Overall, the research suggests that inclusive growth from tourism in Ha Long Bay is not yet evident. This stems partly from the rapid, recent changes with huge new capital-intensive developments, but also from the characteristics and governance of present tourism. Inclusive growth is more likely to occur where development and access extends the average length of stay of visitors. This is not the case with Ha Long Bay where the already falling average length of stay (1.9 days in 1990–1, 1.5 days in 1998 [Dapice, Hoa, Quinn, Tuan, & Van, Citation1998], 1 day in 2012 for international visitors and 0.5 days for domestic tourists [Quang Ninh PPC and Quang Ninh Department of Sports, Culture and Tourism, 2014]) may continue on a downward spiral with the new highway extension from Hanoi. The resultant effects on tourist expenditure and correspondingly reduced demand for accommodation and the night-time economy (a major component of tourist spend in destinations) is likely under this current development scenario.

Although tourism in Ha Long Bay has developed rapidly since the 1990s with some demonstrable economic benefits for the local community (Long, Citation2012), current developments coupled with the government’s market-led reforms are restricting opportunities for inclusive growth. Equitable business opportunities, a stronger local supply chain and robust employment strategies that benefit the broadest section of the destination’s population are seemingly diminishing, rather than increasing. The lessons for other developing countries would seem clear: at present, despite tourism’s potential for local economic development, the research raises further questions about whether tourism can lead to more inclusive growth. Similarly, it raises the question of whether the inclusive growth concept needs further theoretical development for it to be easily applied within the context of large-scale, capital intensive tourism development – a model replicated across much of the developing world’s coastal destinations.

Acknowledgements

This paper reports research jointly funded by the British Council’s UK-ASEAN Knowledge Partnership Fund and Kent Business School but the views expressed are not necessarily those of the British Council. The authors would also like to thank Thao Hien Nguyen for her assistance with fieldwork, as well as the interview respondents who generously gave up their time. We also thank Tim Forsyth, David Harrison, Lukas Hofer, Kate Lloyd and Grahame Whyte for their helpful comments on earlier versions of the paper. We also thank Perseverence Jeyacheya for his invaluable help turning sketch maps into figures. The usual disclaimers apply.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Addison, T., & Nino-Zarazua, M. (2012) ‘What is Inclusive Growth?’ Paper read at Nordic-Baltic MDB meeting, Helsinki, 25 January.

- Ali, I. (2007). Inequality and the imperative for inclusive growth in Asia. Asian Development Review, 24, 1–16.

- Ali, I., & Son, H. H. (2007). Defining and measuring inclusive growth application to the Philippines. (ERD Working Paper Series No 98). Manila: Asian Development Bank.

- Ali, I., & Yao, X. (2004) Pro-poor Inclusive Growth for Sustainable Poverty Reduction in DevelopingAsia: The Enabling Role of Infrastructure Development. ERD Policy Brief Series No. 27. Manila: Asian Development Bank

- Ashley, C. (2006). Participation by the poor in Luang Prabang tourism economy: Current earnings and opportunities for expansion. Report for SNV. London: Overseas Development Institute.

- Bakker, M., & Messerli, H. R. (2016). Inclusive growth versus pro-poor growth: Implications for tourism development. Tourism and Hospitality Research. Online version published 1 August. doi:10.1177/1467358416638919

- Balakrishnan, R., Steinberg, C., & Syed, M. (2013). The elusive quest for inclusive growth: Growth, poverty and inequality in Asia. (IMF Working Paper No. 13/152). Retrieved from http://ssrn.com/abstract=2292339

- Bhanumurthy, N. R. (2014). Recent downturn in emerging economies and macroeconomic implications for sustainable development: A case for India. (UN ESA Working Paper No. 137). Retrieved September, 2, 2016, from http://www.un.org/esa/desa/papers/2014/wp137_2014.pdf

- Butler, G., & Rogerson, C. (2016). Inclusive local tourism development in South Africa: Evidence from Dullstroom. Local Economy, 31, 264–281. doi:10.1177/0269094215623732

- Cadilhon, -J.-J., & Fearne, A. (2005) Lessons in collaboration: A case study from Vietnam. Supply Chain Management Review, May/June, 11-12.

- Cadilhon, -J.-J., Moustier, P., Poole, D., Giac Tham, P. T., & Fearne, A. (2006). Traditional vs. modern food systems? Insights from vegetable supply chains to Ho Chi Minh city (Vietnam). Development Policy Review, 24, 31–49. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7679.2006.00312.x

- CAFOD. (2014, August). What is “Inclusive Growth”? CAFOD Discussion Papers. Retrieved from www.cafod.org.uk/

- Chambers, R. (1983). Rural development. Putting the last first. London: Longman.

- Cohen, E. (1982). Marginal paradises. Bungalow tourism on the islands of Southern Thailand. Annals of Tourism Research, 9, 189–228. doi:10.1016/0160-7383(82)90046-9

- Daldeniz, B., & Hampton, M. P. (2013). Dive tourism and local communities: Active participation or subject to impacts? Case studies from Malaysia. International Journal of Tourism Research, 15, 507–520. doi:10.1002/jtr.1897

- Damodaran, S. (2015). The chimera of inclusive growth: Informality, poverty and inequality in India in the post-reform period. Development and Change, 46, 1213–1224. doi:10.1111/dech.2015.46.issue-5

- Dapice, D., Hoa, H. D., Quinn, B., Tuan, P. A., & Van, B. (1998). Trade and industrial development strategies for the Ha Long Bay region. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Institute for International Development.

- de Haan, A., & Thorat, S. (2013). Inclusive growth: More than safety nets. (SIG Working Paper 2013/1). Ottawa: IDRC (International Development Research Centre).

- Ellis, S., & Sheridan, L. (2014). A critical reflection on the role of stakeholders in sustainable tourism development in least-developed countries. Tourism Planning & Development, 11, 467–471. doi:10.1080/21568316.2014.894558

- Fan, S., Kanbur, R., & Zhang, X. (2009) Regional inequality in china: an overview. In S., Kanbur, R. & X. Zhang, (eds), Regional inequality in china: trends, explanations and policy responses. London: Routledge

- Fernando, N. (2008). Rural development outcomes and drivers: An overview and some lessons. Manila: Asian Development Bank.

- Gainsborough, M. (2010). Present but not powerful: Neoliberalism, the state and development in Vietnam. Globalizations, 7, 475–488. doi:10.1080/14747731003798435

- Gainsborough, M. (2012). Elites vs reform in Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam. Journal of Democracy, 23, 34–46. doi:10.1353/jod.2012.0024

- Galla, A. (2002). Culture and heritage in development. Ha Long ecomuseum, a case study from Vietnam. Humanities Research, 9, 63–76.

- Gascón, J. (2015). Pro-poor tourism as a strategy to fight rural poverty: A critique. Journal of Agrarian Change, 15, 499–518. doi:10.1111/joac.12087

- George, G., McGahan, A. M., & Prabhu, J. (2012). Innovation for Inclusive growth: Towards a theoretical framework and a research agenda. Journal of Management Studies, 49, 661–683. doi:10.1111/joms.2012.49.issue-4

- Gillen, J. (2014). Tourism and nation building at the war remnants museum in Ho Chi Minh city, Vietnam. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 104, 1307–1321. doi:10.1080/00045608.2014.944459

- Graci, S. (2013). Collaboration and partnership development for sustainable tourism. Tourism Geographies, 15, 25–42. doi:10.1080/14616688.2012.675513

- Hall, J., Matos, S., Sheehan, L., & Silvestre, B. (2012). Entrepreneurship and innovation at the base of the pyramid: A recipe for inclusive growth or social exclusion? Journal of Management Studies, 49, 785–812. doi:10.1111/joms.2012.49.issue-4

- Hampton, M. P. (2013). Backpacker tourism and economic development. Perspectives from the less developed world. London: Routledge.

- Hampton, M. P., & Jeyacheya, J. (2013). Tourism and inclusive growth in small island developing states. London: Commonwealth Secretariat.

- Hampton, M. P., & Jeyacheya, J. (2015). Power, ownership and tourism in small islands: Evidence from Indonesia. World Development, 70, 481–495. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.12.007

- Harrison, D. (2004). Tourism and the Less Developed World: Issues and case studies. Wallingford, Oxfordshire: CABI.

- Harrison, D. (2008). Pro-poor tourism: A critique. Third World Quarterly, 29, 851–868. doi:10.1080/01436590802105983

- Hasmath, R. (2015). The paradigms of inclusive growth, development and welfare policy. In R. Hasmath (ed), Inclusive growth, development and welfare policy: A critical assessment (pp. 1–9). London: Routledge.

- Heshmati, A., Kim, J., & Park, D. (2014) Fiscal policy and inclusive growth in advanced countries: their experience and implications for asia. ADB Economics Working Paper Series. No. 422.Manila: Asian Development Bank doi:10.2139/ssrn.2558908

- Hildebrandt, T., & Isaac, R. (2015). The tourism structures in central Vietnam: Towards a destination management organisation. Tourism Planning & Development, 12, 463–478. doi:10.1080/21568316.2015.1038360

- Jones, H. (2013). Entry points for developing tourism in Nepal. What can be done to address constraints to inclusive growth? Centre for inclusive growth - practical solutions for Nepal. London: Overseas Development Institute.

- Kannan, K. P. (2014). Interrogating inclusive growth: Poverty and inequality in India. New Delhi: Routledge India.

- Klasen, S. (2010). Measuring and monitoring inclusive growth: Multiple definitions, open questions, and some constructive proposals. (ADB Sustainable Development Working Paper Series No. 12). Manila: Asian Development Bank.

- Kozel, V. (ed). (2014). Well begun but not yet done: Progress and emerging challenges for poverty reduction in Vietnam. Washington DC: World Bank.

- Kundu, A. (2015). “Inclusive Growth” and income inequality in india under globalization: Causes, consequences and policy responses. In R. Bhattacharya (Ed.), Regional development and public policy challenges in India (pp. 257–289)). New Delhi: Springer India.

- Lee, D., Hampton, M., & Jeyacheya, J. (2015). The political economy of precarious work in the tourism industry in small island developing states. Review of International Political Economy, 22, 194–223. doi:10.1080/09692290.2014.887590

- Lin, Y. J. (2004). Development strategies for inclusive growth in developing Asia. Asian Development Review, 21, 1–27.

- Lloyd, K. (2004). Tourism and transitional geographies: Mismatched expectations of tourism investment in Vietnam. Asia Pacific Viewpoint, 45, 197–215. doi:10.1111/apv.2004.45.issue-2

- Lloyd, K., & Morgan, C. (2008). Murky waters: Tourism, heritage and the development of the ecomuseum in Ha Long Bay, Vietnam. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 3, 1–17. doi:10.1080/1743873X.2008.9701247

- Long, P. H. (2012). Tourism impacts and support for tourism development in Ha Long Bay, Vietnam: An examination of residents’ perceptions. Asian Social Science, 8, 28–39.

- Nguyen, T. T. M., Rahtz, D., & Shultz, C. (2014). Tourism as catalyst for quality of life in transitioning subsistence marketplaces: Perspectives from Ha Long, Vietnam. Journal of Macromarketing, 34, 28–44. doi:10.1177/0276146713507281

- Mark, H. (2009). Karst landscape in the Bay of Ha Long, Vietnam. Geographische Rundschau International Edition, 5, 48–51.

- Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism. (2014). Vietnam annual tourism report 2014. Hanoi: Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism.

- Mitchell, J. (2012). Value chain approaches to assessing the impact of tourism onlow-income households in developing countries.’. Journal Of Sustainable Tourism, 20, 457–475. doi:10.1080/09669582.2012.663378

- Mshenga, P., & Richardson, R. (2013). Micro and small enterprise participation in tourism in coastal Kenya. Small Business Economics, 41, 667–681. doi:10.1007/s11187-012-9449-5

- Painter, M. (2008). From command economy to hollow state? Decentralisation in Vietnam and China. The Australian Journal of Public Administration, 67, 79–88. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8500.2007.00570.x

- Pillay, M., & Rogerson, C. (2013). Agriculture-tourism linkages and pro-poor impacts: The accommodation sector of urban coastal KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Applied Geography, 36, 49–58. doi:10.1016/j.apgeog.2012.06.005

- Quang Ninh Administration of Culture Sport and Tourism (2011) Annual Report of Tourism Information. Ha Long. Ha Long: Quang Ninh Administration of Culture Sport and Tourism.

- Quang Ninh PPC (Provincial People’s Committee) and Quang Ninh Department of Sports, Culture and Tourism. (2014). Tourism Master Plan for Quang Ninh Province to 2020, with vision towards 2030. Ha Long: Quang Ninh Provincial People’s Committee and Quang Ninh Department of Sports, Culture and Tourism.

- Ranieri, R., & Ramos, R.A. (2013) Inclusive growth: building up a concept. (Working Paper 104). Brasilia: International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth (IPC-IG), UNDP

- Rauniyar, G., & Kanbur, R. (2009). Inclusive growth and inclusive development: A review and synthesis of asian development bank literature. (ADB Working Paper Series). Manila: Asian Development Bank.

- Rauniyar, G., & Kanbur, R. (2010). Inclusive development: Two papers on conceptualization, application, and the ADB perspective. (Working Paper 2010-01). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University.

- Roelen, K. (2014). Challenging assumptions and managing expectations: Moving towards inclusive social protection in Southeast Asia. Journal of Southeast Asian Economies, 31, 57–67. doi:10.1355/ae31-1d

- Saad-Filho, A. (2010). Growth, poverty and inequality: From Washington consensus to inclusive growth. (UN/DESA Working Paper 100. November). New York: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs.

- Samans, R., Blanke, J., Corrigan, G., & Drzeniek, M. (2015). Benchmarking inclusive growth and development. (World Economic Forum Discussion Paper). Retrieved June 24, 2015, from http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Inclusive_Growth_Development.pdf

- Scheyvens, R. (2011). Tourism and poverty. London: Routledge.

- Sen, A. (1992). Inequality re-examined. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Suntikul, W., Butler, R., & Airey, D. (2010). Implications of political change on national park operations: Doi moi and tourism to Vietnam’s national parks. Journal of Ecotourism, 9, 201–218. doi:10.1080/14724040903144360 ?

- Tandon, N. (2012) Food security, women smallholders and climate change in caribbean SIDS. (International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth, Research Brief Number 33. Brasilia). Retrieved September 2, 2016, from http://www.ipc-undp.org/pub/IPCPolicyResearchBrief33.pdf

- Torres, R., & Momsen, J. H. (2004). Challenges and potential for linking tourism and agriculture to achieve pro-poor tourism objectives. Progress in Development Studies, 4, 294–318. doi:10.1191/1464993404ps092oa

- Vietnamnet. (2015, June 10). Don’t expect windfall profits from casinos. Vietnam Breaking News. Retrieved June 17, 2015, from http://english.vietnamnet.vn/fms/business/132554/don-t-expect-windfall-profits-from-casinos–experts.html ?

- World Bank (2009) What is Inclusive Growth? World Bank Note. 10 February. Online. Retrieved September 2, 2016, from http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTDEBTDEPT/Resources/468980-1218567884549/WhatIsInclusiveGrowth20081230.pdf

- World Bank. (2012). City development strategy for Halong. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- WTTC. (2015). Economic impact 2015 Vietnam. London: World Travel and Tourism Council.