Abstract

This article examines the relationship between social capital and the creation and exchange of knowledge for grassroots development. It applies a framework that originated in developed countries to the experimental phase of a successful entrepreneurial development programme, undertaken between 2006 and 2012 in rural Bangladesh. Although generally applicable, the framework’s structural dimensions are further developed and divided into three functional subtypes of social capital (bonding, bridging and linking) following distinct pathways in their contribution to the creation and exchange of knowledge, demonstrating domains where programme participants co-created know-how. In conclusion, a framework representing the links between social capital and knowledge is presented.

1. Introduction

Knowledge is like light. Weightless and intangible, it can easily travel the world, enlightening the lives of people everywhere. Yet billions of people still live in the darkness of poverty. (World Bank, Citation1998, p. 1)

As illustrated in the above quote, development discourse often sees knowledge as an antidote to poverty. Indeed, sweeping assumptions are made about ‘lack of knowledge’. Koanantakool, for example, opens a paper with the unsupported statement that ‘… the main causes of poverty in Thailand are the lack of knowledge and management skills’ (Koanantakool, Citation2004, p. 127). Knowledge is also seen as playing a key role in development. For example, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Human Development Index (HDI) monitors long-term, national progress in human development against three fundamental dimensions: long and healthy life, access to knowledge, and standard of living (Gaye, Citation2011). The knowledge dimension of the HDI is, however, measured in terms of formal education and does not pay explicit attention to societies’ own capacities to create and exchange knowledge. This emphasis on external, exogenous knowledge in development processes appears to be shared by the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), agreed by the UN member states in September 2015, which will set the international development agenda for the 2016–2030 period (UN, Citation2015). For example, the SDGs give primacy to scientific and technological knowledge, largely ignoring traditional knowledge which receives only one mention (Cummings, Regeer, De Haan, Zweekhorst, & Bunders, Citation2017). As Ramalingam argues ‘ … the overriding mentality is still that developing countries are vessels to be filled with knowledge and ideas’ (Ramalingam, Citation2015, no pagination). Despite the general recognition of the importance of knowledge, the significance of local knowledge, and its role in development, is not mentioned or clarified. Is knowledge at the grassroots level important for local development and, if so, how is this demonstrated, understood and disseminated?

In developed countries, specifically in organisations and communities of practice, many researchers have charted the relationship between social capital and the creation and exchange of knowledge. This seems to be an interesting approach for development because social capital is an endogenous resource with particular potential to support development processes at the grassroots level, partly because it is present in all contexts. Like our economic capital enables us to buy resources, social capital makes it possible for individuals and groups to access resources, such as information and knowledge, through their social network (Seferiadis, Cummings, Zweekhorst, & Bunders, Citation2015). To explore the link between social capital and knowledge at the grassroots level, we address the following three-pronged research question, based on the example of a development programme in Bangladesh: 1) what types of new know-how are being co-created by the programme, 2) how does strengthening structural, cognitive and relational dimensions of social capital at the grassroots level contribute to knowledge creation and exchange and 3) what insights does this give us into the relationship between social capital and knowledge?

Although there has been considerable research on social capital in development, which we review briefly in the next section (see, for example, Seferiadis et al., Citation2015), such research is not specifically focused on the creation and exchange of knowledge. To support our efforts to make the contribution of social capital more visible, we used the influential Nahapiet and Ghoshal (Citation1998) framework which focuses on the hypothesised relationship between social capital and intellectual capital in organisations, seeking to establish whether it is applicable to development processes among the poor in rural Bangladesh. We were aware that we could not assume that the framework would be directly applicable to this context. Nahapiet and Ghoshal’s research is populated by anonymous employees, who are working together in organisations, are literate and probably with tertiary or at least secondary education, are eating three meals a day, with networks of friends and acquaintances, bank accounts and bank loans, televisions and telephones, computers, refrigerators, cars and houses. Would their framework yield insights into the process of creating and exchanging knowledge among poor women in rural Bangladesh, with primary schooling at best, constrained by norms of female seclusion (purdah) in which they are unable to work outside the home or go out to meet other women, subject to strong social control from their husbands and in-laws, with inadequate food, very few possessions and living in makeshift houses?

The development programme studied here was not originally focused on the link between social capital and knowledge but participants themselves identified social capital as an important element of their access to knowledge as is illustrated by this quote:

People who have lots of friends and who can communicate openly with others: they can improve their lives. But people who are poor and cannot communicate well are not able to make that sort of progress: they do not know other people, they cannot have information.

The programme took place between 2006 and 2012 and, after a period of learning and experimentation, was eventually scaled up to cover 136 villages involving 1300 social entrepreneurs (see, for example, Maas, Bunders, & Zweekhorst, Citation2014a, b, c). In this paper, we focus on the early phase of the programme because it shows gradual increases in knowledge and know-how among the participants which were intricately linked to strengthened social capital. It is this initial, micro-level process, in which the women participants started with very restricted social networks and not much knowledge of how to improve their livelihoods, surviving against all the odds, which is of interest as a possible route to sustainable development.

2. Knowledge and social capital

There is an enormous literature on social capital, defined as ‘the aggregate of the actual and potential resources, which are linked to possession of a durable network’ (Bourdieu, Citation1986, p. 248). Much of this literature is in the field of development studies because social capital can facilitate or hamper development at the micro, meso and macro levels. Three functional subtypes of social capital have been found to have an impact on development outcomes, namely bonding, bridging and linking social capital (for a full review of the concept see Seferiadis et al., Citation2015). Essentially, at the micro-level, bonding capital is found in family connections, bridging within horizontal networks of similar actors (peers), and linking to actors outside the horizontal network, which provides access to resources (vertical ties). These subtypes have distinct impacts in their capacity to facilitate development. For example, entrepreneurs initially draw support from their families and communities, but this is later replaced by ties outside their communities (Woolcock & Narayan, Citation2000). Empirical studies demonstrate that development interventions can successfully stimulate the development of social capital (for example, Bebbington & Carroll, 2002). Seferiadis et al. (Citation2015), strongly influenced by Cilliers and Wepener (Citation2007), identified four additional mechanisms, which play a role in creating social capital, namely the material level of structural opportunities, a sense of belonging, civic literacy, and the ethos of mutuality.

A number of academics have made the link between social capital and access to information, although most of the seminal works on this theme are located in developed countries. Coleman (Citation1988), for example, describes aspects of social relations that provide useful capital resources for individuals, arguing that one form of social capital resides in the information potential that can be accessed through social relations maintained for other purposes. For Lin (Citation1999), social capital facilitates the flow of information. The link between social capital and information has also been made in rural Bangladesh. For example, Bakshi, et al. identified social capital as ‘a powerful tool that affects human behaviour by mitigating information asymmetries among individuals’ (Bakshi, Mallick, & Ulubaşoğlu, Citation2015, p. 1604). In the literature, social capital has been identified as having a number of implications for organisations and networks. First, networks of social relations, particularly those characterised by weak ties or structural holes (disconnections and non-equivalences among actors) are considered to make the diffusion of information more efficient by reducing redundancy (Burt, Citation1992). Second, social capital has been found to encourage creativity and learning (Burt, Citation2002; Fischer, Scharff, & Ye, 2004). Third, it has been shown to support cooperative behaviour, facilitating innovative types of organisation and new forms of association (Fukuyama, Citation1995; Putnam, Citation1993). For organisational and management sciences, social capital is an important concept for understanding institutional dynamics, innovation, and value creation (Nahapiet & Ghoshal, Citation1998) (cited in Cummings, Heeks, & Huysman, Citation2006).

Scholars in the field of organisational and management studies have developed frameworks which hypothesise how social capital contributes to knowledge (Adler & Kwon, Citation2002; Nahapiet & Ghoshal, Citation1998). Probably the best known of these frameworks is Nahapiet and Ghoshal’s (Citation1998) three-dimensional model which describes how social capital contributes to intellectual capital, defined as the ‘knowledge and knowing capability of a social entity’ (Nahapiet & Ghoshal, Citation1998, p. 245). By 2014, the framework had been cited 9430 times and it is ‘widely acknowledged by scholars in different scientific disciplines’ (Ehlen, Citation2015, p. 27). The framework shows how social capital stimulates organisational innovation by creating intellectual capital, based on hypothesised relationships between social capital and the processes necessary for the creation of intellectual capital (Nahapiet & Ghoshal, Citation1998). Nahapiet and Ghoshal (Citation1998) distinguish between the structural, relational, and cognitive dimensions of social capital at the level of organisations as contributing to intellectual capital:

Structural dimension: patterns of connections between actors, including network ties and network configuration. For this dimension, descriptors include density, connectivity, hierarchy, and ‘appropriable organisation’.

Cognitive dimension: shared representation, interpretation, and systems of meaning among actors, such as shared language, codes and narratives.

Relational dimension: key aspects of personal relationships developed on the basis of a history of interactions, including trust, norms, obligations and expectations, and identification.

In this model, the combination and exchange of knowledge takes place because actors anticipate value in knowledge creation and exchange, are motivated to combine and exchange, have the capability to do so, and have access to others for combining and exchanging. Appropriable organisation in this framework relates to the fact that norms and trust developed in the context of an intervention can be transferred from one social setting to another, for example the transfer of trust and relationships from families to organisations. Building on the Nahapiet and Ghoshal (Citation1998) framework, a number of researchers have investigated the link between social capital and tacit knowledge in the corporate sector (see, for example, Huang, Jie, & Yuan Wang, Citation2009; Isa, Abdullah, & Senik, Citation2010; Yang & Farn, Citation2009). Based on Polanyi (Citation1967), Nonaka (Citation1994) made a distinction between tacit and explicit knowledge. Explicit knowledge comprises knowledge that can be expressed by language, while Polanyi’s tacit knowing can only be captured in language with context dependent or demonstrative elements, and can only be learned by doing (Davies, Citation2015).

In the next section, we provide an overview of the PRIDE programme in Bangladesh and of the transdisciplinary methodology followed by this programme. Following this, we apply the three-dimensional model (Nahapiet & Ghoshal, Citation1998) to consider dimensions of social capital that facilitated the combination and exchange of knowledge in the PRIDE programme.

3. The study and the methodology

Bangladesh is one of the poorest countries in Asia with some 47 million people living below the poverty line (World Bank, Citationundated). It is challenged by an extremely high population density, poor economic growth and high unemployment (Mabud, Citation2008). Poverty is more prevalent in rural areas than urban areas with more than 20 per cent of the rural population living in ‘extreme poverty’ in 2010 (Mangani, Oot, Sethuraman, Kabir, & Rahman, Citation2015). Many development programmes aim to alleviate poverty but are unable to reach the poorest members of the population (Abed & Matin, Citation2007; Mair & Marti, Citation2009). In addition, women face a greater burden of poverty than men, as women also face considerable inequality in terms of reproductive health, empowerment and access to the labour market (UNDP, Citation2015). Women’s opportunities to earn a living outside the home are also restricted by social norms of female seclusion, known as purdah.

In 2004, the Route to the Sustainable Development Programme was started by a local non-government organisation (NGO) PRIDE, with support from the Athena Institute of the VU University Amsterdam in the Netherlands. The programme, aiming to reach the local poor in rural areas, was located in villages of Jessore District in the Khulna Division of western Bangladesh. In this locality, 48–60 per cent of the population lives below the poverty line of USD2 per day (Islam & Morgan, Citation2012). The programme started with two villages and expanded every year to reach 136 villages by 2012. The programme had two main objectives: to train poor households in income-generating activities (IGAs) and, at the same time, to make it possible for them to stimulate development of other people in their communities. As mentioned above, social capital was not the original focus of the programme but it became increasingly relevant as the participants emphasised the importance of their social network in providing access to resources. Given that the programme was successful in stimulating social entrepreneurship and strengthening the capital base of poor households (Maas et al., Citation2014a, b, c), this paper examines the programme’s success from the perspective of knowledge co-creation.

A transdisciplinary action research methodology called Interactive Learning and Action (ILA) (Bunders, Citation1990) was employed to stimulate local development. During the reconnaissance phase (2004–2006), in-depth interviews and focus group discussions (FGDs) were used to understand obstacles and opportunities for development. The poor living in the area were landless with, at best, a small garden to grow vegetables or raise one or two chickens, lived in rudimentary houses and could not afford to eat more than two meals a day, sometimes only one meal. It became clear that the most pressing need concerned nutrition. As a result, growing vegetables in a garden was identified as a first solution to stimulate development. Next, the ILA process consisted of learning cycles: using a variety of M&E (monitoring and evaluation) tools, adaptations were made every year to the project (2007–2012). The action-research cycles started with an experimentation phase in which the NGO selected and trained women to pilot new approaches to development. In 2006, two women were identified who were already involved in IGAs and had developed a social network, involving contacts with other people in their village and other organisations. These two women were willing to experiment with other IGAs, such as home-based gardening and poultry rearing, to improve their incomes and to try to help others. Monitoring and evaluation of these activities resulted in suggestions on how to train other poor women in IGAs.

In 2007, four new poor women were included in the programme. PRIDE trained these women as ‘intermediaries’ in the knowledge and skills required to conduct IGAs and to disseminate these skills to other poor people, who represented the intermediaries’ beneficiaries. The training sessions were based on the lessons learnt from the first two participants. PRIDE organised training sessions with the intermediaries and with their beneficiaries on a variety of topics. In 2008, 20 participants were included in the programme, 15 women and five men. The NGO focused on training only the intermediaries who, from this time onwards, were responsible for training their own beneficiaries. New IGAs, such as handicrafts and sewing, were introduced and tried out. Other IGAs were developed so that intermediaries could earn incomes from their interactions with their beneficiaries, such as organising the sale of handicrafts and the vaccination of poultry. The NGO monitored the training of the beneficiaries by attending the group training sessions, and also by accompanying the intermediaries on home visits. In 2008, the men left the programme to pursue other employment opportunities. From this point onwards, the programme focused only on women.

In the course of 2008–2009, all participants were able to earn money from the IGAs. This led to the launch of the implementation phase. Some 32 women were selected and trained as intermediaries in 2009 without receiving a stipend. Previously trained intermediaries also remained in the programme although they were no longer paid to take part. From 10 original subjects, the training sessions were condensed to cover only the five most profitable ones: vegetable and seed production; tree nursery management; backyard poultry rearing and vaccination; tailoring and handicrafts; and farm management, including fish production, goat rearing and cow fattening. In 2010, 26 women were recruited, and actively monitored to analyse the changes occurring in their livelihood strategies. As processes became better understood, monitoring by PRIDE became less intensive. Building on the previous learning cycles, the scaling-up phase started in 2011 and took an explicit social entrepreneurship approach. In 2011, 26 entrepreneurs were trained and in 2012, an additional 26 women were recruited.

For the sake of clarity, the women trained by PRIDE whether in the first two phases (intermediaries) or in third one (social entrepreneurs) are referred to as ‘entrepreneurs’ in the rest of this article.

4. Data collection and analysis

Various researchers were involved in the project from 2004, including the authors of this article. They visited Bangladesh at various intervals from periods ranging from one week to three months. The action-research project spanned over six years and comprised a rich data set that enables detailed reflections. A mixed-method approach was used. It included in-depth interviews to explore lived experiences from informants’ perspectives and to identify important issues; focus-group discussions (FGDs) to enable group interactions and to explore steps in processes; visual ethnography to record changes in the project participants’ lives from their own point of view and to enable participants to engage in a collective analysis of issues affecting their development; and questionnaires were used to measure change. In addition, the programme also employed a range of visualisation techniques (such as participatory mappings) and participant observations including visits to participants’ gardens or participation in handicraft making and cooking. Data were also drawn from a study of the NGO’s internal documents and observations of its working practices, including participation in training sessions for entrepreneurs.

Triangulation of researchers, instruments and data was organised. Research questions, interview design and data analysis were developed in a research team. Researchers engaged in reflection with the staff of PRIDE on progress and challenges. The staff of PRIDE was continuously monitoring the project and communicating with the foreign-based research team by emails and telephone. This enabled reflection on the programme from different perspectives and allowed for multiple compositions of the research team to gather field data. Methods to triangulate data were used: saturation was sought, and various data collection methodologies were used so that questions could be asked differently, ranging from the very open photo-voice method, which asked women to depict changes in their lives, to the closed questionnaires asking for different themes on how much change had occurred, such as the quantity of vegetables produced. Data collected from one method was checked against data obtained from at least two other data-collection methods. For example, the results of the photo-voice with intermediaries were checked against questionnaires and in-depth interviews. In addition, data was checked by two different researchers or research teams. Different researchers applied the same instruments so that the data obtained by different researchers could be compared to check for inconsistencies. Data collected between different stakeholder categories was also triangulated. For example, data on relationships between entrepreneurs and community members was checked against interviews with entrepreneurs and against interviews with community members.

Respondents included the NGO staff, the project participants, that is entrepreneurs and their beneficiaries, but also a range of community members. Data from all research phases was used to answer the study questions. The study questions comprised: (1) exploring barriers for development encountered by community members; (2) domains of changes resulting from the programme; (3) how the programme stimulated development; and (4) how the community perceived the programme.

In particular, this study made use of photo-voice to assess the changes that women had experienced due to the programme. This community-based participatory method made it possible for women to ‘record and reflect on their lives […] from their own point of view’ (Wang, Burris, & Ping, Citation1996, p. 1) despite their limited literacy. Disposable cameras were distributed to 24 women who had been selected by PRIDE staff as being active in the programme and willing to take part. Cameras were distributed to 12 entrepreneurs and 12 beneficiaries, all of whom were requested to take photographs of what had changed in their lives since the start of the programme. After one week, the cameras were collected and the photographs were developed. Some 23 participants then considered their photographs in eight group discussions, comprising small groups of three to four women. Participants were asked to describe and explain their photographs while the groups were asked to reflect on these stories.

In addition, in-depth interviews were conducted over the years with 12 entrepreneurs, 24 beneficiaries, and 23 community members and 13 PRIDE staff members. Interviews were conducted by the first author (AS) with a translator, and transcribed verbatim from the English translation. FGDs were conducted with the staff of PRIDE (seven), entrepreneurs (three), beneficiaries (two) and community members (three). Questionnaires were administrated to 63 entrepreneurs and eight beneficiaries. Furthermore, data collected by the third author from 2010 to 2012 (JM) served to validate our findings in the longer term.

In the experimentation phase of the programme, PRIDE characterised its target beneficiaries as lacking in social capital. For example, during an FGD in March 2008, they described their target populations’ communication in terms of having ‘few friends’, ‘poor networking skills’, ‘low social abilities’ and ‘low speaking power’, and poor access to information and technology. PRIDE considered that the low level of social capital was a barrier to the development of their target beneficiaries because they could not obtain information or land. Facing challenges linked to the social domain, PRIDE developed strategies to strengthen the programme participants’ social capital.

5. Learning cycles

Along learning cycles, different strategies were developed by the NGO and the project participants to strengthen women’s social capital across its different functional subtypes: bonding, bridging and linking social capital.

Initially, when PRIDE enters a village, its staff negotiates with village power-holders and with women’s families to identify suitable candidates to take part in the programme and to gain permission for them to be engaged in IGAs. Bonding capital with husbands and families was identified during early learning cycles as very important because women need their families’ consent to take part and to leave the home. Women report that as their families see that they are contributing to the household’s food supply (vegetable gardens, fish ponds) and income (selling goods and services, such as handicrafts and poultry vaccination), their position in their family improves. In interviews and FGDs, women explained that they become more ‘valued’ by their husband and wider family. In one FGD, entrepreneurs explained: ‘Our husbands love us more because we can contribute money.’ In addition, women’s opinions and advice start to carry more weight: ‘My husband takes more notice of my decisions than before’ (Beneficiary). Women portrayed themselves in photographs as being able to provide goods or money for the household, or sending their daughter to school. In one example, a woman explained that now that her husband listens to her, they have decided to send their daughter to school. This bonding capital not only plays a role in changing the value of women’s knowledge within the household but is also perceived by the women interviewed as a basic precondition of women’s ability to develop their networks with other women. This represents their bridging capital.

The programme stimulated bridging social capital. Before the arrival of PRIDE, purdah restricted women’s ability to leave the home, to be involved in IGAs, and to interact with other women. PRIDE built on momentum initiated by other NGOs (such as micro-credit) to facilitate women’s capacities to interact with each other:

A few years ago, actually, women in our village didn’t talk to each other very much. But since the NGOs came, things have changed. Now there are meetings in the village and we can talk to each other.

The programme provided women with structural opportunities to meet: entrepreneurs met other entrepreneurs during trainings. When the entrepreneurs started organising the training of their own beneficiaries, poor women had the opportunity to meet peers in their village. Women started exchanging seeds: entrepreneurs gave seeds to their beneficiaries, while beneficiaries would give seeds in return to the entrepreneur but they also started giving seeds to other community members. Through these exchanges, women interacted more, started giving advice to each other and also helped each other in their gardens. Women used these structural opportunities to develop their network and to exchange information and advice.

From the very early learning cycles, PRIDE found that interactions between poor women and other community members were essential for women’s development. PRIDE purposefully created structural opportunities for women to meet by negotiating with the power-holders in the village – women’s husbands, their in-laws, rich men and Imams – making it possible for women to meet each other regularly and to attend training sessions. This aspect appears to be very similar to one of the mechanisms identified by Nahapiet and Ghoshal (Citation1998) for the creation and exchange of knowledge, namely access to others for combining and exchanging. In interviews, FGDs and questionnaires, entrepreneurs and beneficiaries reported knowing more people and having closer and stronger ties with other poor women since the start of the programme. As a result, women were able to exchange knowledge as explained by a beneficiary during an interview:

I talk to my friends [… My friends help me with] lots of knowledge. I get solutions for some problems. […] I talk to people who are a bit educated and they give me suggestions: you can go here and there … (Beneficiary)

In terms of linking capital, namely vertical links with power-holders, women also developed ties with other actors – landowners, the Imam, members of the local government – which they used to gain access to land, permission to leave their homes to undertake social and economic activities, access to local legal judgements, and greater knowledge. This linking social capital is of instrumental importance in knowing how to gain access to markets and for solving problems, as this quote from an entrepreneur shows:

Most of the time my beneficiaries ask me for advice concerning problems. If I know the answer already, I will make a suggestion. Sometimes I suggest going to someone else to ask for help, such as a village elder who might know how to help. Then I go with her and will learn from the elder too. (Entrepreneur)

However, it appeared that gaining access to linking social capital by developing vertical ties usually required support from PRIDE. Even when vertical ties had been developed, some entrepreneurs found it difficult to maintain them, particularly in the case of links with local power-holders.

6. New types of knowledge created by programme participants

Evaluation questionnaires and interviews in the scaling-up phase have shown that the project facilitated entrepreneurs’ single-loop and sometimes double-loop learning processes, which stimulated social entrepreneurial activities (see also Maas, Bunders, & Zweekhorst, Citation2013). In this section, we answer the first part of the research question, namely 'what types of new know-how have been co-created by the programme participants?' The programme developed new know-how across a range of domains, including livelihoods, social interaction, giving advice and social entrepreneurship. This made it possible for women to identify paths for improvement based on the co-creation of knowledge but also provided a momentum for change as one beneficiary reported: ‘The entrepreneur also encourages us to improve our family’s situation’ (Entrepreneur).

In the next section, we describe how endogenous knowledge for social entrepreneurship was developed.

6.1. Know-how of improved livelihoods

Through the photo-voice activity, entrepreneurs and beneficiaries ascribed many positive changes to the programme, including improvements in livelihood strategies, both agricultural and non-agricultural. The livelihood activities shown in the photographs included the cultivation of the kitchen garden, the rearing of animals (poultry, goats and cows), and aquaculture in small ponds. Non-agricultural activities included sewing and handicrafts (generally embroidery), the making of nets and baskets, and the production and selling of cooked food.

Many women reported a diversification of their livelihood strategies. For example, some women started cultivating vegetables and selling handicrafts as a result of the programme. Many women also took photographs that demonstrated an intensification of their activities: they now produce more vegetables; their animals survive; and their chickens now produce more eggs and their cows more milk. Moreover, many photographs show how women have extended the land they can use for their agricultural activities. In a context of land scarcity, photographs show how women are better able to use all available land, including land that was previously ‘vacant’ or ‘empty’. For example, they now use ‘that narrow space between the ponds’ to cultivate vegetables. They also make use of opportunities for aquaculture, for example rearing fish in ‘small holes’ of one square metre. In particular, the women now construct pergolas on their house, above their garden, or above the ponds to cultivate vine crops, thereby creating additional scope for agricultural production. The women also took photographs of other changes in their lives: for example, they showed that they were now able to invest in food for their family or in their children’s education.

6.2. Know-how of social interaction

During the learning cycles of the programme, women reported during interviews and FGDs that they are developing their networking and communication skills as one beneficiary explained:

Since I started working with PRIDE, many things have changed. I now know how to communicate with rich people. […] I have learnt how to speak to rich people, how to speak to poor people, how to lease land. (Beneficiary)

They are also learning how to use their social network to gain access to knowledge as the following quote illustrates:

If we need to talk to someone else that we don’t know, we will ask some other rich person we know. We will ask ‘Uncle, I need to talk to this person who has knowledge. How can I go about it?’ (Entrepreneur)

6.3. Know-how of giving advice

In tandem with their increased social status, entrepreneurs and beneficiaries report during interviews and FGDs that they are becoming increasingly recognised for the good advice they are able to offer others: ‘women come and ask’ and people ‘listen’ to their advice:

Before, I felt shy and now I feel confident to give suggestions, it is mutual, it is also the women who are attracted: they know I will give good suggestions because I have good vegetables. (Entrepreneur)

The giving of advice is supported helped by material exchanges as this beneficiary (who is gradually becoming an entrepreneur herself, copying the entrepreneur in her village) explained: ‘To whom I gift seeds, I also teach.’ Similarly, gifts are made to entrepreneurs by beneficiaries as a ‘thank you’ for advice as one beneficiary explained:

Willingly, I present the entrepreneur with vegetables as gifts. I am using her suggestions and improving so I think I should give her something but there is no pressure to do so. (Beneficiary)

6.4. Know-how of social entrepreneurship

Women are developing their ability to identify economic opportunities at the same time as further developing their ability to help others. They are also seeing the opportunities that are available to others, as this quote from a beneficiary shows:

[In this photograph, you can see …] my neighbour and her husband, they are making baskets. He used to make the baskets alone. I suggested that she should help him because she would sit down after finishing her household work. Now she helps him. I have learnt from the entrepreneur that you can give suggestions to others and show them how they can improve.

Hence, different types of knowledge are being co-created and exchanged. The next section will explore how this is facilitated by women’s social capital.

7. Dimensions of social capital that facilitate knowledge co-creation and exchange

In this section, we apply the framework developed by Nahapiet and Ghoshal (Citation1998) and, at the same time, adapt it to fit the findings from the PRIDE programme. In this way, we answer the second part of the research question, namely 'how does strengthening structural, cognitive and relational dimensions of social capital at the grassroots level contribute to knowledge creation and exchange?'

7.1. Structural dimensions

The structural dimensions of social capital relate to network ties, network configuration, and appropriable organisation.

7.1.1. Network ties

According to Nahapiet and Ghoshal (Citation1998), network ties provide benefits in terms of access, timing and referrals to information. Through evaluation questionnaires and interviews in the scaling-up phase, it appeared that the project facilitated learning processes through trainings and learning by doing (see also Maas et al., Citation2013). Throughout the learning cycles, many beneficiaries mentioned during in-depth interviews held at different phases that they have better access to information. Beneficiaries reported that entrepreneurs helped them to find out who they should contact for their IGAs, such as for selling handicrafts, but also for other domains related to livelihoods. For example, entrepreneurs explained that they helped their beneficiaries to navigate the complicated maze of health-service providers: entrepreneurs know whom to contact, for example, they have phone numbers of health providers or ambulances, and whom to avoid, such as quacks, fake organisations, non-accredited doctors and the like. An entrepreneur explained that they mediate contacts for their beneficiaries ‘until this is no longer necessary’ because the beneficiaries have developed their own networks. Many women (both entrepreneurs and beneficiaries) also claimed they are now more active in gaining knowledge and in requesting support, thus engaging in double-loop learning. As one beneficiary explained during an interview:

Before, I was also getting in touch with the governmental agricultural officer but it was less necessary. Now, I am working more and needing more support so contact is taking place more often than before. (Beneficiary)

7.1.2. Network configuration

Network configuration – density, configuration and hierarchy – are also hypothesised to play a role in information access. During the photo-voice activity, nearly half of the 346 photographs taken by entrepreneurs and beneficiaries displayed other people, bringing attention to the importance of ties with others. During interviews, questionnaires and FGDs, it became clear that different networks had been developed: bonding ties with family members, bridging ties with neighbours and, to a lesser extent, links with power holders. Through interviews with different stakeholders, specific aspects of network configuration representing bonding, bridging and linking capital were found to be of importance in providing access to others for combining and exchanging knowledge.

7.1.3. Appropriable organisation

This part of the structural dimension seems to be highly relevant to the programme because the knowledge and skills developed during the programme were evident across all domains. In fact, improvements in livelihoods would not have been possible without changes at the level of social interactions. It appeared that different network configurations provide access to different resources: family bonds provide access to support; bridging ties with neighbours provide access to exchanges and know-how; and links with the local elite provide access to land and markets. But the transfer of skills can also be seen from livelihoods to health, for example, as explained by one beneficiary:

This is a photograph of me making a fire with leaves with the neighbours. I suggested to them it is not good for your health to stay too near the fire [because of the smoke]; it is better to keep warm by using a blanket. This is not something I learnt from the entrepreneur, this is my own understanding and the neighbours are listening to me. (Beneficiary)

In addition, when beneficiaries demonstrated skills in one dimension, their capacities in other dimensions were increasingly recognised: ‘they are interested in asking me for suggestions because my vegetables are growing well and the chicken and ducks are well too’.

7.2. Cognitive dimensions

The cognitive dimension in the Nahapiet and Ghoshal framework is related to ‘what’ is being shared, including the production of the shared language, codes, and narratives.

7.2.1. Shared codes, language and narratives

The women involved in the programme share a language, a history, and codes, all reinforced by the fact that they share livelihoods. When PRIDE starts the project in a village, these women are identified as being from the poorest households in the village through wealth ranking activities. These women are either landless or have tiny gardens; they live in rudimentary houses, have sparse furniture (at best, two tin boxes and a rack to stock their belongings) and few poultry; and they generally eat only twice a day (sometimes three times, sometimes only once), rarely including fish or meat. Women stay within the confines of their home, and their activities generally revolve around taking care of the house and children. They rely on their husbands to earn money and to buy everything; they even need to ask them to buy a few biscuits to offer guests. Women reported that before the advent of the programme, they were stuck in poverty, not seeing the way out.

Given the shared livelihoods, changes and improvements made by one woman were directly applicable to others. In addition, women could exchange knowledge about the same livelihood base. Given their shared livelihoods, their codes and also their narratives are shared to describe their situation. As one women highlighted, ‘the poor understand the pain of the poor, the rich people cannot understand’ (Beneficiary). This highlights ties established within networks based upon common life histories in which norms and values are shared. This facilitated the exchange and co-creation of knowledge because women had shared frames of reference. The participants also noted the difficulties they faced in sharing knowledge with people from different socio-economic backgrounds. With other community members, such as older men, knowledge is not co-created but passed on vertically.

7.3. Relational dimensions

7.3.1. Identification

Identification represents the process by which individuals identify themselves with another person or group (Nahapiet & Ghoshal, Citation1998). This is very closely aligned to the shared narratives and livelihoods in the cognitive dimension. Women interviewed were consciously developing and accessing strong ties with members of the same social stratum because they recognise a sort of ‘like-mindedness’. This is linked to altruistic behaviour, such as giving gifts. Participating in others’ improvement also adds to the participants’ quality of life: ‘I feel happy to give gifts and see people around improve’. As one beneficiary explained: ‘I feel happy that I am giving suggestions and that I am right and that people come to me when they have problems. In the village, everyone is happy to help others’. Women were most comfortable when interacting with peers and these peer networks favour the exchange and co-creation of knowledge. Women in the programme often avoided contact with people even poorer than they were and who would be less able to reciprocate in exchanges. In addition, they also tended to denigrate people who are poorer than they are themselves, holding them responsible for their own poverty. For this reason, including the very poorest, such as beggars and women who are not able to eat every day, in a project like this one might face difficulties.

Moreover, the programme also strengthened women’s status within the community as an entrepreneur explained in a FGD: ‘We are pleased because members of our groups are improving: it is the outcome. Also, we are respected’. Such recognition was not only limited to other women of similar socio-economic status but also extended to village power-holders. Therefore, a sense of duty to help, a responsibility toward others also emerged as a vector to exchange knowledge and co-create novel solutions for the development of the community.

7.3.2. Trust, norms, obligations and expectations

The programme sought to avoid conflict with local norms. While it sought change to enable the development of vulnerable families, activities remained in harmony with the local norms, thereby not detaching women from dominant customs or their place within the community. From the early learning cycles, the NGO negotiated within these norms without confronting them, in particular purdah. For this reason, the IGAs developed by the entrepreneurs were generally home-based, such as farming and handicrafts.

Development of trust was an important issue within the programme and is the subject of another paper in its own right (Maas et al., Citation2014a). Given that the programme was taking place in an environment with a high level of institutional distrust and a low level of institutional trust (Maas et al., Citation2014a), PRIDE played an important part in developing trust within the villages and with the participants. As one village leader put it, ‘They [PRIDE] came suddenly into the village and we could not trust them. Many NGO people come here and cheat people’ (Maas et al., Citation2014a, p. 74). In addition, the entrepreneurs needed to develop the trust of their beneficiaries across four domains: the personal domain of intentions and benevolence; their stories and capacities; the ‘proof of principle’ that the entrepreneur could be successful in vegetable production; and the advantages accruing to their beneficiaries (Maas et al., Citation2014a). Only when they had proved their trustworthiness in these four domains was their advice listened to and followed. Even when the entrepreneurs had shown their trustworthiness in the first three domains and had shown ‘proof of principle’, their beneficiaries still needed convincing that they could also be successful and were hesitant to buy seeds. To overcome this barrier, PRIDE gave seeds to the entrepreneurs who then gave them to their beneficiaries, representing the inaugural gift. This is explained by an entrepreneur in the following quote: ‘It was difficult during the first 2 months to make them understand but the [gift of] seeds helped them to understand.’ In addition and of crucial importance, the programme was able to leverage the norm of altruism to encourage women to support each other. Many photographs display women helping and giving gifts to each other, while questionnaires report increased exchanges. Narratives show how the strengthening of exchanges was made on a non-contract basis as gifts. In interviews and FGDs, women explained that they help each other because ‘it is normal in the village’.

8. Discussion of the relationship between social capital and knowledge

What appears from our analysis is that bonding, bridging and linking social capital have different implications in terms of access to knowledge. Bonding capital with husbands and in-laws was a necessary precondition for women to be able to participate in networks and IGAs; bridging capital predominantly provided access to like-minded advice and knowledge about livelihoods, health, and other problems; while linking capital provided access to resources, such as to land, and advice from the government extension officer. Moreover, bonding, bridging and linking social capital have different modes of knowledge creation. Bridging social capital not only enables women to share narratives and co-create knowledge, stimulated by a strong motivation to exchange and combine knowledge, but also generates a very strong capacity to identify opportunities for development, identified as value anticipation by Nahapiet and Ghoshal (Citation1998). On the other hand, bonding and linking social capital enable transfers of knowledge (migratory knowledge) that the poor women combine with their own (embedded knowledge) to produce new knowledge and know-how, which becomes highly relevant and strengthens their capacities for development. In addition, the capacity to co-create and exchange knowledge is mediated by the cognitive and relational dimensions of social capital. Only when women have shared codes and livelihoods are they able to co-create knowledge. Prior identification of women as ‘knowing’ but also as ‘known’ to others – which also generates trust – is required for knowledge to be exchanged. The exchange and co-creation of knowledge is enacted between community members who have expectations but also obligations to help each other, based on norms of solidarity. In , we have attempted to link the functional sub-types of social capital as they relate to the newly elaborated dimensions. We hypothesise that the bonding and bridging functional sub-types of social capital give access to similar, relevant knowledge, while linking social capital may give access to different knowledge, namely knowledge which cannot be found among families and within horizontal networks.

Table 1. Sub-types of social capital and their links to the dimensions of social capital

Gift exchange played an unexpectedly important role within the context under study. Indeed, a gift seems to be the visible manifestation of social capital: gifts can be material, such as seeds and vegetables, but also non-material such as advice and knowledge. Exchanges were intensified as a result of the programme and this strengthened social capital. Moreover, gifts display circularity, which is endowed with sustainability. Although the importance of making gifts does not appear to be widely recognised in the development literature, the close relationship between social capital and gift exchange in the business environment is recognised. For example, Dolfsma and colleagues consider that ‘building a new social capital community, or extending an existing one, requires protracted investments in the form of gift exchange between individuals’ (Dolfsma, Van Der Eijk, & Jolink, Citation2009, p. 32).

Linked to the exchange of gifts, trust appears to play a far more important role in this context than it does in the Nahapiet and Ghoshal (Citation1998) framework, possibly because the programme was taking place in a context with low levels of trust – where NGOs are not trusted and where women are not trusted to be able to contribute to their own, their household’s and their community’s development. Initially, the gift exchange of seeds was chosen as an alternative to market exchange because it overcame this lack of trust. Fisher has identified the link between trust and knowledge, arguing that ‘trust provides an essential catalyst enabling passive information to be transformed into usable knowledge’ (Fisher, Citation2013, p. 1). In addition, the positive feelings of the women involved in the programme, their feelings of self-worth and of being valued, should not be underestimated. Gift, trust and positive feelings are the hidden mechanisms of this development programme.

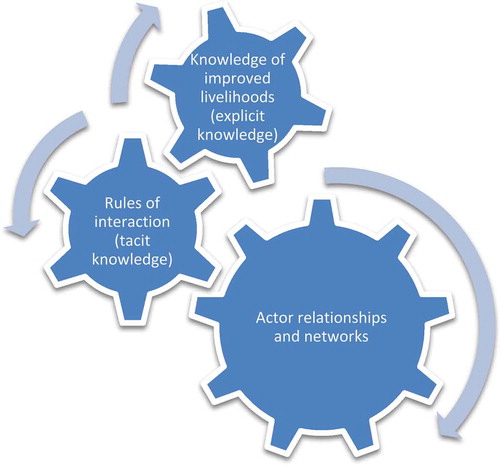

Based on the findings from the programme in Bangladesh, we also feel that the Nahapiet and Ghoshal framework can be simplified to clarify the relationship between knowledge and social capital. The results from the programme indicate in our opinion that the cognitive dimension of social capital represents explicit knowledge; the structural dimension represents the relationships and networks; and, finally, the relational dimension represents the rules for the interaction and exchange, comprising tacit knowledge (see ). It is, therefore, not surprising that in the rule-based interaction between knowledge and relationships/networks, knowledge creation and exchange takes place. This means that knowledge is one of the main components of social capital. Explicit knowledge, actor relationships and tacit knowledge represent the building blocks of social capital (). It is the increase in explicit knowledge which improves livelihoods, although new networks and new rules of interaction are also needed.

9. Conclusions

This paper considered the dimensions of social capital that contribute to the creation and exchange of knowledge at the grassroots level. Despite having been developed for a very different hypothesised group of people, the Nahapiet and Ghoshal (Citation1998) framework is applicable to the grassroots level and the context under study. We have, however, expanded the model in order to enhance our understanding of how development interventions stimulate social capital for knowledge creation and exchange. Based on these findings, we have developed a new understanding of the link between social capital and knowledge, arguing that social capital has three main dimensions as it can contribute to development: explicit knowledge in the form of new livelihood strategies, tacit knowledge in the form of rules for interaction, and relationships/networks.

The changes brought about by the programme are based on the social capital already theoretically available to the participants, but unused. The dynamic process was instigated and guided by PRIDE, and facilitated by a transdisciplinary methodology that involved a long-term process of experimentation and learning. In this process, PRIDE’s role and the long-term intervention stand in stark contrast to the typical pattern of development interventions which involve ‘exciting new development idea, huge impact in one location, influx of donor dollars, quick expansion, failure’ (Hobbes Citation2014, no page reference). The programme was based on PRIDE’s long-term, in-depth knowledge of the communities in which the programme was implemented, which involved understanding the knowledge and know-how of the women involved and their poverty. Replicating such stimulation of social entrepreneurship in a resource-constrained environment will require that NGOs and other actors take the time to strengthen the capacities of facilitating staff and are prepared to undertake such a process. Other NGOs can learn from this experience, which is based on a long-term intervention with co-creation of know-how across multiple domains.

According to the Dutch Scientific Council for Government Policy, ‘the ultimate task of high-quality development policy remains to search for mechanisms to initiate self-reinforcing processes of endogenous change’ (Van Lieshout, Went, & Kremer, Citation2010, p. 232). This programme fits within this category because it has facilitated poor women to develop self-reinforcing processes of endogenous change, based on local knowledge. The capabilities developed in the programme foster the development of women and their communities in a sustainable manner. In addition, it is striking that the potential to develop the know-how co-created in the programme existed before PRIDE initiated it. In that sense, the programme has been built on the potential within the social network, the potential being part of the definition of social capital. This potential also appears to be linked to what has been called ‘affordances’, namely action possibilities available in the environment to an individual, independent of the individual’s ability to perceive this possibility (McGrenere & Ho, Citation2000; cited in Cummings et al., Citation2006). The endogenous nature of knowledge and know-how generated are consistent with Ferreira’s definition of development as ‘most of all, the result of the synergy among millions of innovative initiatives people take every day in their local societies, generating new and more effective ways of producing, trading, and managing their resources and their institutions’ (Ferreira, Citation2009, p. 99). This study demonstrates that knowledge is of huge importance for development at the grassroots level but that leveraging knowledge and social capital is not a simple process: it requires concerted efforts and dedication from people at the grassroots level and NGOs who are helping them.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Abed, F. H., & Matin, I. (2007). Beyond lending: How microfinance creates new forms of capital to fight poverty. Innovations: Technology, Governance, Globalization, 2(1–2), 3–17.

- Adler, P., & Kwon, S.-W. (2002). Social capital: Prospects for a new concept. Academy of Management Review, 27(1), 17–40. Retrieved from https://msbfile03.usc.edu/digitalmeasures/padler/intellcont/SocialCapital(AMR)-1.pdf

- Bakshi, R. K., Mallick, D., & Ulubaşoğlu, M. A. (2015). Social capital and hygiene practices among the extreme poor in rural Bangladesh. The Journal of Development Studies, 51(12), 1603–1618.

- Bebbington, A. J., & Carroll, T. F. (2002). Induced social capital and federations of the rural poor in the Andes. In C. Grootaert & T. Van Balestar (Eds.), The role of social capital in development: An empirical assessment (pp. 234–278). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of capital. In J. E. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of theory of research for the sociology of education (pp. 241–258). New York, NY: Greenwood Press.

- Bunders, J. F. G. (1990). Biotechnology for small-scale farmers in developing countries: Analysis and assessment procedures. Amsterdam: Free University Amsterdam.

- Burt, R. S. (1992). Structural holes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Burt, R. S. (2002). The social capital of structural holes. In M. F. Guillen, R. Collins, P. England, & M. Meyer (Eds.), New directions in economic sociology (pp. 31–56). New York, NY: Russel Sage Foundation.

- Cilliers, J., & Wepener, C. (2007). Ritual and the generation of social capital in contexts of poverty: A South African exploration. International Journal of Practical Theology, 11(1), 39–55.

- Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology (94S) Organizations and Institutions: Sociological and Economic Approaches to the Analysis of Social Structure. 94, 95–120. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2780243

- Cummings, S., Heeks, R., & Huysman, M. (2006). Knowledge and learning in online networks in development: A social-capital perspective. Development in Practice, 16(6), 570–586.

- Cummings, S., Regeer, B. J., De Haan, L. J. A., Zweekhorst, M. B. M., & Bunders, J. F. G. (2017). Critical discourse analysis of perspectives on knowledge and the knowledge society within the Sustainable Development Goals. Development Policy Review, online first, April 2017. doi:10.1111/dpr.12296

- Davies, M. (2015). Knowledge–Explicit, implicit and tacit: Philosophical aspects. International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 74–90. doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.63043-X

- Dolfsma, W., Van der Eijk, R., & Jolink, A. (2009). On a source of social capital: Gift exchange. Journal of Business Ethics, 89(3), 315–329.

- Ehlen, C. G. J. M. (2015). Co-creation of innovation: investment with and in social capital studies on collaboration between education – industry – government ( Doctoral dissertation). Open Universiteit, Heerlen.

- Ferreira, S. M. (2009). The new enlightenment: A potential objective for the KM4Dev community. Knowledge Management for Development Journal, 5(2), 94–107.

- Fischer, G., Scharff, E., & Ye, Y. (2004). Fostering social creativity by increasing social capital. In M. Huysman & V. Wulf (Eds.), Social capital and information technology (pp. 355–559). Cambridge: MIT press.

- Fisher, R. (2013). A gentleman’s hand shake: The role of social capital and trust in transforming information into usable knowledge. Journal of Rural Studies, 31, 13–22.

- Fukuyama, F. (1995). Trust: Social virtues and the creation of prosperity. London: Hamish Hamilton.

- Gaye, A. (2011). Contribution to Beyond Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Name of the indicator/method: The Human Development Index (HDI) ( Unpublished manuscript). New York: UNDP Human Development Report Office, UN Development Programme. Retrieved 20 March, 2016 from http://ec.europa.eu/environment/beyond_gdp/download/factsheets/bgdp-ve-hdi.pdf.

- Hobbes, M. (2014, November 18). Stop trying to save the world. Big ideas are destroying international development. New Republic. Retrieved from https://newrepublic.com/article/120178/problem-international-development-and-plan-fix-it

- Huang, K., Jie, F., & Yuan Wang, K. (2009). The relationship between social capital and tacit knowledge. Paper presented at 2009 International Conference in Management Sciences and Decision Making Tamkang University, Tapei.

- Isa, R. M., Abdullah, N. L., & Senik, Z. C. (2010). Social capital dimensions for tacit knowledge sharing: Exploring the indicators. Jurnal Pengurusan. 30, 75–91. Retrieved from http://ejournal.ukm.my/pengurusan/article/view/335

- Islam, M. R., & Morgan, W. J. (2012). Non-governmental organizations in Bangladesh: Their contribution to social capital development and community empowerment. Community Development Journal, 47(3), 369–385.

- Koanantakool, T. (2004). ICTs for poverty reduction in Thailand. Asia-Pacific Review, 11(1), 127–141.

- Lin, N. (1999). Building a network theory of social capital. Connections, 22(1), 28–51.

- Maas, J., Bunders, J. F. G., & Zweekhorst, M. B. M. (2013). Creating social entrepreneurship for rural livelihoods in Bangladesh: Perspectives on knowledge and learning processes. Knowledge Management for Development Journal, 9(2), 67–84.

- Maas, J., Bunders, J. F. G., & Zweekhorst, M. B. M. (2014a). Trust building and entrepreneurial behaviour in a distrusting environment: A longitudinal study from Bangladesh. International Journal of Business and Globalisation, 14(1), 75–96.

- Maas, J., Seferiadis, A. A., Bunders, J. F. G., & Zweekhorst, M. B. M. (2014b). Social entrepreneurial leadership: Creating opportunities for autonomy. In P. H. Phan, J. Kickul, S. Bacq, & N. Nordqvist (Eds.), Theory and empirical research in social entrepreneurship (pp. 223–255). Johns Hopkins Research Series on Social Entrepreneurship. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University.

- Maas, J., Seferiadis, A. A., Bunders, J. F. G., & Zweekhorst, M. B. M. (2014c). Bridging the disconnect: How network creation facilitates female Bangladeshi entrepreneurship. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 10(3), 457–470.

- Mabud, M. A. (2008). Bangladesh Population: Prospects and Problems ( Doctoral dissertation). Department of Life Sciences, North South University, Dhaka.

- Mair, J., & Marti, I. (2009). Entrepreneurship in and around institutional voids: A case study from Bangladesh. Journal of Business Venturing, 24(5), 419–435.

- Mangani, R., Oot, L., Sethuraman, K., Kabir, G., & Rahman, S. (2015). USAID office of food for peace food security country framework for Bangladesh (FY 2015–2019). Washington, DC: FHI 360/FANTA.

- McGrenere, J., & Ho, W. (2000). Affordances: Clarifying and evolving a concept. Proceedings of Graphics Interface 2000. Retrieved March 12, 2016, from https://www.cs.ubc.ca/~joanna/papers/GI2000_McGrenere_Affordances.pdf

- Nahapiet, J., & Ghoshal, S. (1998). Social capital, intellectual capital and the organisational advantage. Academy of Management Review, 23(2), 242–266.

- Nonaka, I. (1994). A dynamic theory of organizational knowledge creation. Organization Science, 5(1), 14–37.

- Polanyi, M. (1967). The tacit dimension. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Putnam, R. D. (1993). The prosperous community: Social capital and public life. American Prospect, 13, 35–42.

- Ramalingam, B. (2015, September 24). Giving flesh to the science and innovation we need to see. Steps Blog. Retrieved February 25, 2016, from http://steps-centre.org/2015/blog/giving-flesh-to-the-science-and-innovation-we-need-to-see/

- Seferiadis, A. A., Cummings, S., Zweekhorst, M. B. M., & Bunders, J. F. G. (2015). Producing social capital as a development strategy: Implications at the micro-level. Progress in Development Studies, 15(2), 170–185.

- UN. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. Retrieved March 20, 2016, from https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld/publication

- UNDP. (2015). Human development report: Work for development. Basingstoke: Author.

- Van Lieshout, P., Went, R., & Kremer, R. (2010). Less pretension, more ambition: On development policy in times of globalisation. WRR/University of Amsterdam Press English Language edition 2010. Retrieved July 23, 2013, from www.wrr.nl/fileadmin/en/pub…Less_pretention_more_ambition.pdf

- Wang, C., Burris, M. A., & Ping, X. Y. (1996). Chinese village women as visual anthropologists: A participatory approach to reaching policymakers. Social Science & Medicine, 42(10), 1391–1400.

- Woolcock, M., & Narayan, D. (2000). Social capital: Implications for development theory, research, and policy. The World Bank Research Observer, 15(2), 225–249.

- World Bank. (1998). World development report 1998/1999: Knowledge for development. New York: Oxford University Press.

- World Bank. (undated). Bangladesh country overview. ( Retrieved July 13, 2016, from http://www.worldbank.org/en/country/bangladesh/overview

- Yang, S.-C., & Farn, C.-K. (2009). Social capital, behavioural control, and tacit knowledge sharing—A multi-informant design. International Journal of Information Management, 29(3), 210–218.