?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

We present results of a randomised field experiment where voters in Tanzania were given information about elite use of tax havens. Information provided in a neutral form had no effect, while information phrased in more morally charged terms led to a reduction in voting intentions. Rather than increase the perceived importance of voting, charged information tends to undermine confidence in political institutions and the social contract. The effects are particularly pronounced among the less well off, indicating that increased transparency in the absence of perceived agency may not improve political participation.

1. Introduction

Through a combination of financial secrecy and low taxes on foreign residents and companies, tax havens facilitate tax avoidance and evasion, concealment of proceeds from corruption or criminal activities, and avoidance of legal responsibilities (Schjelderup, Citation2016). The exposure of developing countries to negative tax haven related practices is substantial. Illicit financial flows from developing and emerging economies are estimated at a significant US$1 trillion in 2014, 20 to 30 per cent of private wealth in many African countries are estimated to be held in tax havens (compared to 8% globally), and developing countries are significantly more exposed to tax avoidance by multinational firms (Global Financial Integrity, Citation2017; Johannesen, Tørsløv, & Wier, Citation2016; Zucman, Citation2014). In addition, the impact of tax haven related practices may be particularly detrimental to developing countries, for a number of reasons. Reduced public spending is more damaging to poor countries where the marginal benefit of spending is high, the cost of raising taxes on other sectors is greater in countries that have a narrow industrial base, and the costs of enforcing tax obligations are larger in countries where the institutional setting is weak. Moreover, the existence of tax havens reduces disincentives to corruption and other illicit activities which are rampant in many developing economies. It also facilitates patronage which undermines the accountability of the political elite, making democratic progress difficult.

Recent leaks of confidential records of tax haven facilitators and their clients through the LuxLeaks, the Swiss Leaks, the Panama Papers, and the Paradise Papers, have lead some to express optimism that this information will increase public pressure to address the problem (Seabrooke & Wigan, Citation2016). And we have seen effective popular mobilisation around the leaks in some well-functioning democracies, for instance in the case of the Icelandic prime minister being forced to resign in 2016 when the Panama Papers revealed he had held offshore assets. However, the effect of information about elite use of tax havens on popular mobilisation is much less clear in countries where the democratic system does not work well, where the general confidence in political institutions is low, and where cases of elite capture and impunity may not be viewed as anomalous to how the economy and the political system operate.

In this paper, we report the results of a randomised survey experiment which tests the effect of providing information about elite use of tax havens on voter turnout in elections. The experiment was conducted among 600 eligible voters in Dar es Salaam, the major city of Tanzania, a country with an imperfect democratic system, where multiparty elections have been held regularly since 1995, but where the incumbent party has never lost. The respondents were randomly assigned to two treatment groups and a control group. The first treatment group was shown a 90-second video with information about the Tanzanian elite’s use of tax havens, given in a neutral language and form. The second treatment group was shown a video containing the same information, but using more charged language, where the unfairness of the elite’s use of tax havens was emphasised.Footnote1 The tax haven information given in both treatments was factual, based on the Swiss leaks case published by The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists. The control group watched no video.

Our results show that the neutral information treatment had no effect on voter turnout, voting intentions rates were the same as in the control group. Strikingly, however, the charged information treatment had a significantly negative effect on turnout, reducing voting intentions by about nine percentage points compared to the control group. In the context of an imperfect democracy in which our experiment was conducted, information about elite capture seems at best ineffective in promoting citizen political participation, and at worst counter-productive if provided in a morally accentuated form. While we measure effects on voting intentions rather than actual voting, our negative results suggest that this is less of a concern. Previous analysis shows that those who state they do not intend to vote almost always do not in fact vote (Achen & Blais, Citation2016), and since our charged treatment pushes more respondents into the do not intend to vote category, the effect on actual voting is unlikely to be positive. Moreover, social desirability or experimenter demand effects related to the treatments would likely increase rather than reduce the gap between stated intentions and actual voting, in which case our results understate the negative effect of the information provided on actual voting.

Further analysis of mechanisms behind our main results suggests that both information treatments, but in particular the morally charged one, tend to make respondents take less favourable views of the prevailing social contract and of how much confidence one can have in political institutions. We also find important heterogeneous effects across socio-economic groups. The negative effect of the charged treatment on voting predominantly reflects an effect among those with little wealth and individuals who are not household heads, suggesting that participation is particularly adversely affected for groups with low perceived agency.

Our analysis addresses the literature on effects of dubious, corrupt, and criminal activities on voter behaviour. Empirical studies from contexts as varied as Brazil (Ferraz & Finan, Citation2008), India (Banerjee, Green, McManus, & Pande, Citation2014), and Mexico (Chong, De La O, Karlan, & Wantchekon, Citation2015) suggest that voters tend to penalise politicians for corrupt or criminal activities. However, other studies suggest that corruption is of minor importance to voters compared to other factors like shared ethnicity or a politician’s record (Chauchard, Klasnja, & Harish, Citation2017), or that voters may favour corrupt candidates in the expectation of future clientelistic benefits (Kramon, Citation2016). Our results suggest that studies of candidate choice pay too little attention to turnout, to the possibility that information on corruption or other dubious activities may make voters favour neither candidate. For instance, discrete choice experiments like Chauchard et al. (Citation2017) and Banerjee et al. (Citation2014) may overstate mobility of voters between corrupt and non-corrupt candidates by not including or analysing the possibility that voters prefer to opt out of the choice altogether.

An important exception to the limited attention to turnout is Chong et al. (Citation2015), who study the effect of distributing fliers containing corruption information to randomly selected constituencies in Mexico. Their results are consistent with ours in identifying a negative effect on voter turnout in treated constituencies. However, since our video treatments were delivered directly at the individual level and political participation responses recorded immediately after treatment, we avoid potential biases from selective information uptake and strategic party response present in studies using mass communication to disseminate information. The results of Chong et al. (2015) may overstate the negative effect of corruption information if the people who actually read their fliers are those who normally vote, and whose participation has nowhere to go but down. Similarly, if the fliers are met with strategic responses from the political parties competing for office, it is hard to separate these effects from that of the information treatment.

Our results are inconsistent with ideas that corrupt and self-serving elite behaviour signals anything about the elite that the population values. It has been argued that corrupt behaviour may be seen as a signal of which political candidate will provide the most in clientelistic transfers (Kramon, Citation2016), and that the poor may be particularly supportive of corrupt candidates due to greater vulnerability (Kurer, Citation2001, p. 70). Or alternatively, the economic elites’ use of tax havens could be admired as a smart and savvy way of getting around tax rates on mobile assets that have been set too high (Hong & Smart, Citation2010). If this were the case, we would expect information on tax haven use to increase support for the political system, increasing turnout. We find the opposite. And the poor seem particularly critical of these forms of elite activities, while at the same time seeing little chance of curtailing them through ordinary participation in the electoral system.

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 presents a brief conceptual framework underlying our analytical approach. The experimental design and empirical approach are detailed in Section 3. Section 4 presents descriptive statistics. Our main results are presented in Section 5, with evidence on mechanisms and heterogeneity across groups presented in Section 6. Section 7 concludes.

2. Conceptual framework

Our empirical analysis addresses three main questions: 1. How does information on elite tax haven use affect voter turnout? 2. Do neutral and morally charged information on tax haven use affect voter turnout differently, and if so, how? 3. Are there differences in responses to the treatments across socio-economic groups, in particular between the poor and the more wealthy?

Theoretical arguments suggest that information on elite tax haven use has an ambiguous effect on turnout, a priori. In rational choice models of voting, individual voters compare their expected benefit of voting with the costs of voting (Downs, Citation1957; Riker & Ordeshook, Citation1968). Information about elite use of tax havens can increase the importance of getting the right candidate elected and/or strengthen the perceived civic duty to vote. On the other hand, the information may highlight the deficiencies of a political system, suggesting that the elite comes out on top whoever wins the election, or undermining the civic duty to vote or the perceived probability that the voter is pivotal in a flawed electoral system.

This ambiguity is not dispelled if we instead consider game-theoretic, group-based voting theories. Ethical voting theories assume that voters identify with and pursue the goals of distinct groups (Feddersen & Sandroni, Citation2006). Social image theories emphasise voting as a way of being perceived favourably by others (Ali and Lin, Citation2013; DellaVigna, List, Malmendier, & Rao, Citation2017). Leader mobilisation theories emphasise the role of group leaders in applying social pressure or providing material incentives to get their group members to vote (Morton, Citation1991; Shachar & Nalebuff, Citation1999; Uhlaner, Citation1989). Similarly to the individual voting model, our information treatments may highlight the importance of one’s own group winning the election, and hence increase turnout. On the other hand, our treatments may undermine identification with a group, and the effectiveness of social and leader pressure to promote the group’s interests, if the information signals that the benefits of group membership are highly unequally distributed.

As for the differential effect of our treatments, it seems reasonable to expect that the charged intervention will have a stronger effect than the neutral one, in whichever direction the treatments work. A number of studies have analysed the effects of negative and positive campaigning on political behaviour (Ansolabehere, Iyengar, Simon, & Valentino, Citation1994; Barton, Castillo, & Petrie, Citation2016; Fridkin & Kenney, Citation2011; Lau, Sigelman, & Rovner, Citation2007). While our experiment compares neutral and charged information treatments, rather than positive and negative ones, similar theoretical arguments can be applied. Like negative advertising, our charged information may be more informative than the neutral information, or stand out more against a backdrop of positive information and experience, making our charged treatment more memorable and likelier to be mentally processed by the voters. In line with prospect theory (Kahneman & Tversky, Citation1979), our charged information treatment may make the loss from self-serving elite behaviour more salient and hence provoke a greater behavioural response. Moreover, our charged treatment may be met with stronger emotional responses by our subjects which may feed through to behaviour. The effect of the charged treatment is hence likely to be more extreme in either direction.

We also see heterogeneous effects on the turnout of the poor and less poor in our sample as ambiguous, a priori. In line with the arguments considered in Kurer (Citation2001, p. 70), the poor may see corrupt elite behaviour as a signal of greater clientelistic transfer on which they are more dependent. We should then see a more positive effect on the turnout of the poor. However, our treatments do highlight the fact that a patrimonial system mainly benefits the very wealthy. While it is commonly observed that African politics are highly clientelistic (Chabal & Daloz, Citation1999; Van de Walle & Butler, Citation1999), the resources transferred through clientelism in practise benefit narrow elites, with very small material gains accruing to citizens (Van de Walle, Citation2003). If our treatments highlight or strengthen citizen views that this is the case, the greater social distance of the poor to the elite may provoke either a more positive effect on turnout if the poor view the election outcome as more important, or a more negative effect if the poor take the treatments to mean they have little influence over how the economy is run in any case.

3. Research design

3.1. Context and timing

Our survey experiment was conducted from 30 October to 13 November 2015. In other words, data collection started five days after the general election in Tanzania on 25 October, and one day after the official election results were announced on 29 October. The general election that preceded our survey experiment took place in the context of what can be described as an imperfect democracy. While multi-party general elections were introduced in 1995, this and every subsequent election was won by the party Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM), which has ruled the country since independence. The country is hence not a consolidated democracy, in the sense that there has been a transition of power from an incumbent to an opposition party following any election. The CCM candidate John Magufuli won the 2015 election with 58.5 per cent of the vote against the opposition candidate’s 40 per cent. Turnout in the 2015 presidential election was 62.4 per cent of the voting age population, considerably higher than the 40.7 per cent of the preceding election, probably reflecting a higher level of competitiveness.Footnote2

To our knowledge, the question of tax havens did not feature substantially in the political campaigns for the 2015 election. Our results hence do not seem contingent on some pre-existing introduction of these issues immediately preceding the experiment. On the contrary, the absence of these types of issues in the campaign, and the fact that both main candidates were from the ruling elite suggest that we are in a setting where voters may perceive the political system to be particularly susceptible to capture by the elite. It should be noted that since taking office on 5 November, President Magufuli has embarked on an apparent drive to reduce corruption in the public sector. While some symbolic actions were taken immediately following his inauguration, the major and much publicised activities were introduced after our data collection had completed, including the sacking of dozens of port officials and the arrest of the head of the Tanzania Revenue Authority. Our survey was hence conducted in a setting where public perceptions of elite capture and limitations of democratic elections to address this were on the negative side.

3.2. Sampling and survey design

A pre-analysis plan for the survey experiment was submitted to The American Economic Association’s registry for randomized controlled trials (AEA RCT registry) on 9 November 2015.Footnote3

Sampling was done as follows. From a list of all polling stations in Dar es Salaam in the 2010 election (polling station information from the 2015 election was not available to us when preparing the survey), we randomly selected 24 polling stations. In each of these locations, a team of eight enumerators walked pre-defined routes evenly spaced in eight different directions from the polling stations, selecting every third household along the way. In each household, a random person at or above the age of 18 and of the enumerator’s gender was selected for an interview (there were four enumerators of each gender). A total of 25 interviews were conducted in this manner in the catchment area of each polling station, for a total of 600 interviews. Interviews were conducted in Swahili.

To avoid having responses primed by early questions, we collected only age and gender in the first section of the interview, as these were part of the selection process of respondents (respondents had to be above voting age and of the enumerator’s gender). We then moved immediately to randomisation of respondents into one of two video treatments (detailed below), or to the control group. Randomisation was hence at the individual level, and not blocked by polling station, resulting in approximately 200 respondents in each group. Balance tests (see Section 4) show that randomisation was successful in terms of balance on the pre-specified co-variates, and also on distance from the respondents’ dwelling to their respective polling stations. After the treatment/control stage, the enumerators proceeded directly to a section on voting and political participation, from which our dependent variable is taken. This was followed by questions on other political participation than voting, beliefs about how well democracy works, views on the social contract, and confidence in various political institutions then followed. Finally, a set of socio-economic background questions was collected in the final section.

3.3. Treatments

In the treatment section, respondents were randomly assigned to watch one of two videos, or to the control group, where no video was shown. The design of the videos was carefully considered in a pilot, to make the concept of tax havens as accessible to our respondents as possible. We found that using the term ‘Swiss billions’ to denote the phenomenon met with greater understanding among respondent than more abstract terms. The term ‘Swiss billions’ has been used extensively in the media and in public debates in Tanzania and refers to the implication of 99 Tanzanian nationals in the so-called Swiss Leaks case.Footnote4 The 99 Tanzanian nationals involved have not been named. However, their total holdings in the Swiss bank HSBC has been put to $114 million, which translates to about 200 billion Tanzanian Shillings, hence the term ‘Swiss billions’. The case has been repeatedly discussed in Tanzanian newspapers.

Both treatment videos hence contain definitions and explanation of tax haven use, starting from the highly publicised case of the Swiss billions. Both videos also contain information on what the use of tax havens entails in terms of reduced tax revenue for Tanzania, and therefore less money available to spend on public services or infrastructure, specifically schools, hospitals and roads. The treatment videos differ, however, in the tone and language used. The first treatment video is comparatively neutral in tone and language, as neutral as it can be when discussing not only definitions of tax havens, but also some of their implications for Tanzania. The second video is more morally charged, using words like ‘hiding’ money abroad about tax haven use, of wealthy individuals ‘avoiding to pay the taxes we are all supposed to pay’, and focusing on effects on the respondent and his or her family rather than general effects for Tanzania. The visual side of the videos is mostly the same, and different only in the addition of a shady looking wealthy tax evader in the second treatment video. Each video is about 90 seconds long, and was shown to the respondent on the tablet used for data collection, with headphones for the respondents.

3.4. Empirical strategy

Given successful randomisation to treatment and control groups, differences in responses across the groups will reflect a causal effect of exposure to the videos, and not other underlying differences between the groups. In the absence of a placebo treatment for the control group, we cannot completely rule out the possibility that the estimated effects reflect the act of watching a video rather than the content of the videos. However, it seems unlikely that our results reflect the act of watching a video, and the fact that we find different results for our two video treatments suggests that content matters. We note that previous experimental studies using video treatments differ in terms of their placebo choice; Bernard, Dercon, Orkin, and Taffesse (Citation2014) use a placebo while Ravallion, van de Walle, Dutta, and Murgai (Citation2015) do not. In our case, it seems difficult to conceive of a placebo video sufficiently neutral as to have no possible effect on participation, while at the same time not being boring to watch, so we decided to not use one.

The variables used in our analysis are presented in in Appendix B. The main dependent variable is intention to vote. This is a dummy variable based on responses to the question ‘If there was a new general election tomorrow, would you vote?’. We do, however, make one important adjustment to this variable.Footnote5 Due to social desirability bias, more people will likely say they would vote than actually vote if there was a new election tomorrow. We therefore recode from ‘Yes’ to ‘No’ the responses of subjects who claim to have voted in the 2015 general election, but fail to answer correctly two control questions on the appearance of the ballot boxes used in the election, and of the ballot sheets.Footnote6 Given the simplicity of these control questions, and the short space of time between the 2015 election and our survey, truthful voters should be able to recall the appearance of ballot boxes and sheets.

Table 1. Impact of exposure to information on elite use of tax havens

Table 2. Mechanisms

Table 3. Heterogeneous effects over covariates

Table B1. Main variables

In other words, we assume that if people misrepresent their actual voting behaviour in the election that just was, they will also misrepresent their intention to vote in a new election tomorrow. Since the underlying problem is one of social desirability bias, it seems plausible that respondents more susceptible to this form of bias will tend to exaggerate their voting behaviour across successive voting questions. The proportion misrepresenting their intention to vote is balanced across treatment and control groups.Footnote7 The importance of verifying claims by eligible voters of their voting behaviour was highlighted by our pilot. In the pilot data, 72 per cent of respondents reported having voted in the 2010 general election, a considerable over-statement since actual turnout rates in that election were about 40 per cent of the voting age population. This form of misrepresentation is a well-known problem in this kind of survey data; 80 per cent of respondents to the 2012 Afrobarometer survey in Tanzania similarly claim to have voted in the 2010 election. As the data section below suggests, a correction using the two control questions works well in bringing claims of voting in the 2015 election close to actual turnout rates. The adjustment is also important to correctly estimate the association between intention to vote and covariates such as gender (men have a significantly greater tendency to misrepresent their voting behaviour in our sample) and voting in the preceding election (without the adjustment, the estimated correlation between voting in the 2015 election and intention to vote in a new election is negative). Kolstad and Wiig (Citation2016) make a similar type of correction and show that this leads to results for covariates that are the opposite of studies not making such corrections (Croke, Grossman, Larreguy, & Marshall, Citation2016; Isaksson, Citation2014; Isaksson, Kotsadam, & Nerman, Citation2014).

In the pre-analysis plan we also specified two additional outcome variables. Retrospective voting, an outcome variable reflecting whether the respondent would change today his decision to vote/not vote in the 2015 general election. And other political participation, an outcome variable constructed through factor analysis of seven dummy variables reflecting non-voting forms of political participation over the coming six months (including being active in a political party, a civil society organisation, in political meetings, in demonstrations, being more politically active in general, following politics more frequently in the media or discussing it more frequently with friends). There are no significant results for these two other outcome variables (for results, see Appendix E in the Supplementary Materials). One reason we find no effect of the treatments on the retrospective voting variable may be that it is harder to relate to for respondents in the sense that you cannot in practise change your actual vote, whereas you can decide whether to vote tomorrow. Alternatively, regret theory suggests that decisions are made in anticipation of subsequent regret (Loomes & Sugden, Citation1982). For the other participation variable, the underlying questions ask for political activities over the coming six months, which may be less concrete than our main dependent variable by referring to a more distant future.

We test for balance between our treatment and control groups on the co-variates specified in .Footnote8 These include age and gender of respondents, whether they were born in Dar es Salaam, education, household headship status, wealth, religion, occupation, and whether they voted in the 2015 general election. Our covariates also include polling station fixed effects. Our wealth indicator is an asset index constructed through factor analysis of questions of whether the respondent’s household owns a TV, a radio, a motor vehicle, and the number of rooms the household occupies. We also asked directly about income in the survey, but see the replies as less reliable than those on assets, and in addition the non-response rate on the income question was high (19% declined to answer). For education, we use three dummies for completion of primary, secondary and tertiary education, with no completed education the excluded category. Religion is captured by two dummies for Christianity and Islam, with other religions the excluded category. Occupation is represented by three broad indicator variables, capturing whether the respondent is self-employed, employed in the private sector, or employed in the public sector, with other or no employment the excluded category. The indicator variable of whether the respondent voted in 2015 is adjusted in the same manner as our dependent variable, changing responses from ‘Yes’ to ‘No’ where a respondent could not correctly answer the two control questions on appearance of the ballot boxes and ballot sheets used in the election.Footnote9 While not specified as a covariate in the pre-analysis plan, we have also used the GPS coordinates of the respondents’ dwellings and their respective polling stations to calculate their physical distance from the polling station, in order to show that the treatment and control groups are balanced on this variable. In addition, we collected data on perceptions of democracy, the social contract, institutions and a few other variables, to analyse mechanisms and heterogeneous effects (see Section 6 for details).

We start by comparing the outcome in the control group with the two treatment groups collapsed into one. This is done through ordinary least squares estimation of the following equation:

Here is the outcome variable voting intention for individual i in the catchment area of polling station s,

is an indicator variable taking the value one if individual i is in one of the two treatment groups, and zero otherwise,

is a vector of control variables and

polling station fixed effects. We report results both with and without covariates (including polling station fixed effects). We estimate all equations using robust standard errors, and do not cluster errors since randomisation into treatments and control is done at the individual level.

The main part of our analysis centres on the comparison of each of the two treatments with the control. To this end, we use the following specification:

Here we regress the outcome variable on two separate treatment variables; is an indicator of whether the respondent was exposed to the neutral treatment, and

an indicator of exposure to the charged treatment. We also add a test of whether the effects of the two treatments are different using two-sided t-tests.Footnote10

Following our main results, we examine mechanisms behind the results and heterogeneous effects across our covariates. These analyses were not specified in the pre-analysis plan, so our analyses of mechanisms and heterogeneity in Section 6 can be considered explorative.

4. Data

Summary statistics for our sample are presented in in Appendix B. Our adjusted voting variables show that 62.5 per cent of voters intended to vote if there was a new election tomorrow, and that 64.3 per cent reported voting in the 2015 general election. These adjusted figures are very close to actual turnout rates of 62.4 per cent of the voting age population in this election, and much more realistic than the unadjusted intentions to vote of 71.3 per cent, and unadjusted claims to have voted in the 2015 elections of 77.5 per cent. It appears our approach of using control questions on ballot box and ballot sheet appearance have worked quite well, at least in terms of aggregate numbers.

Table B2. Summary statistics, main variables, full sample

In terms of socio-demographic variables, the mean voter in our sample is 35 years old, half are male, just under a third were born in Dar es Salaam, the median voter has completed primary education, half are household heads, there are a few more Muslims than Christians but few of any other belief, and most are self-employed and in practise working in the informal sector. The asset index is not directly informative of the general level of wealth, but on the underlying variables 83 per cent own a radio, 72 per cent a TV, 21 per cent a motor vehicle, and the household of the median respondent occupies three rooms. The distance to the polling station variable shows that our respondents range from living right next to the polling station to living 4.7 kilometres away, with the mean distance being a quarter of a kilometre.

in Appendix B provides evidence that the randomisation was successful in the sense that there is balance on co-variates. The first three columns provide means for the each balancing variable for the neutral treatment, charged treatment, and the control group, respectively. The subsequent three columns report the p-value from a t-test of the difference of means on each balancing variable between the two treatment groups and the control group. There are only two significant differences in that the neutral treatment group contains a lower proportion of people born in Dar es Salaam than the control group, and the charged treatment group has a lower proportion of government employees than the control group. In total, there are no more differences than you would expect by chance. The final column of contains the p-value of an F-test of the null hypothesis that the treatment arms do not predict the means on each balancing variable. The results are consistent in there being no significant differences across treatment and control groups.

5. Main results

Our main results are presented in . The first column shows results for our combined treatment variable, that is the effect on voting intention of having seen either of the two videos. While the point estimate is negative, it is not significant. Columns 3 presents results for the combined treatment variable with the co-variates added, including polling station fixed effects, and results are essentially the same. The more interesting results emerge when we distinguish between the two treatments, as is done in columns 2 (without covariates) and 4 (with covariates). The neutral treatment has no effect on voting intentions. However, the charged information treatment has a significantly negative effect on intentions to vote. According to our estimates, being exposed to charged information about elite use of tax havens reduces intentions to vote by between 8.5 and 9.3 percentage points. The p-value of a t-test that the two treatments have the same effect is included in the bottom row of column two, and confirms that the effects of the two treatments are different. In sum, our main results suggest that providing voters with neutral information about elite use of tax havens has no effect on participation, but providing them with charged information significantly and substantially reduces political participation.

Results for the co-variates suggest that there is a strong positive correlation between intention to vote and having voted in the 2015 election, as one would expect. Men also have significantly lower intentions to vote than women. While data on actual participation by gender is not available for the 2015 election in Tanzania, official data from the Tanzanian National Election Commission state that 53 per cent of registered voters were women.Footnote11 In our data, while men are more likely to report having voted, our control questions also reveal that they are less likely to actually have voted than women. In fact, of all the covariates in our specification, being male is the only factor that is significantly associated with misrepresenting your voting decision.Footnote12 We also find a small (in economic terms) negative effect of age on voting. The other results indicate that, conditional on having voted, gender and age, there is no association between voting intention and district of origin, education, headship status, income, religion, or occupation.

6. Mechanisms and heterogeneous effects

In light of the above results, the question of why charged information on questionable elite practices tends to reduce intentions to participate politically becomes important. Our survey included a set of 11 questions related to the respondent’s view of how well democracy and in particular elections work in general and in Tanzania, the extent to which they believe elite actions undermine the social contract, and their confidence in specific political institutions including parliament, political parties and central and local governments. In terms of sequencing, these questions were all asked after the treatment, and are therefore used to assess how the treatments affected or activated different forms of views, rather than for heterogeneity analysis. In our analysis of this data, we want to illuminate what kinds of views were affected by the treatments, but also want to avoid the challenge that with 11 dependent variables unaffected by the treatments and a significance level of 10 per cent, significant results for our charged treatment variable will on average be found for one of them. We therefore aggregate the 11 variables into three composite indices reflecting the respondent’s belief in democracy (how well democracy and elections work), their faith in the social contract (and specifically the extent to which it is being undermined by elite actions), and their confidence in political institutions (parliament, political parties, central and local government). In constructing the indices, the underlying variables are weighted by their inverse standard deviations in the control group, but the results are robust to other weights, both equal weights and weights calculated using factor analysis.Footnote13

The results when we use these three composite indices as dependent variables in additional regressions are reported in . The coefficient for the charged treatment is consistently negative across all three indices, but larger and significant for the faith in social contract and confidence in political institutions indices only. A possible interpretation is that providing information on the use of tax havens has more of an effect on views on elite-citizen interactions and on confidence in concrete political institutions than on more abstract views on democracy. The effects are sizeable, on the underlying five-point scale the charged treatment reduces assessments of the social contract and political institutions by about a half and a third of a point, respectively. The neutral treatment also has negative effects on the faith in social contract and confidence in political institutions indices, but for all three indices these effects are less negative compared to the charged treatment (and significantly so for the first two indices as captured by the p-value at the bottom of the table). While both treatments hence seem to generate or activate negative views of the social contract and political institutions, our results suggest that the effect is only strong enough to influence voting intentions in the case of the charged information treatment.

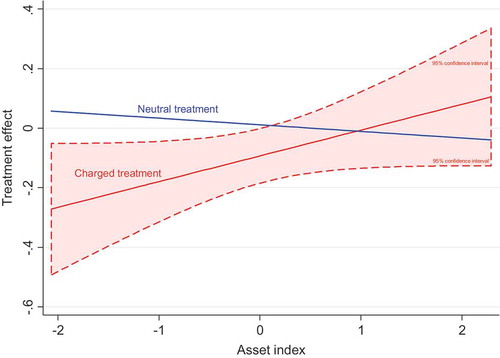

Voters may respond differently to information depending on their political and socio-economic background. summarises the main findings of our analysis of possible heterogeneous effects across covariates. Two covariates appear particularly important.Footnote14 In the first column of the table, we interact our two treatment variables with the asset index. The asset index runs from approximately −2 to 2, with a mean of 0. Each of the treatment coefficients hence captures the effects of the treatments on voting intentions for those with mean assets. The effect of the charged treatment for this group is negative, and as the subsequent interaction with the asset index shows, it is even more negative for those with less than mean assets, that is an asset index that is negative. In , we elaborate the marginal effects of the charged and neutral treatments for different levels of the asset index. As the figure shows, there is a negative effect of the charged information treatment at levels of assets below the mean, whereas above the mean the effect is indistinguishable from zero. This suggests that the charged information affects voting intentions primarily of less wealthy voters. One interpretation of this is that poorer voters have less agency to influence the direction of their own lives and perceive themselves as less likely to have a political impact through voting, making them respond more negatively to suggestions that the political system is not working. In support of this interpretation, our control group data shows a positive correlation between the asset index and the extent to which voters believe their vote matters to the way the country is run (p < 0.047). Moreover, the results presented in column two of suggest a similar conclusion. Here, the treatment variables are interacted with a dummy for whether the respondent is the head of his or her household. The treatment effect of the charged information is negative for respondents who are not household heads, while there is no significant effect for household heads (as captured by the p-value at the bottom of the table), again suggesting that those with less agency tend to respond negatively to the charged information treatment.

Figure 1. Conditional effects of treatments with 95 per cent confidence intervals

The differential effects may also be related to the issue raised in the treatments resonating differently with the poor and the more wealthy. On the one hand, the issue may be more important to the wealthy since they are more likely to pay taxes in our context, provoking more negative reactions to tax evasion and making them less likely to withdraw from voting. On the other hand, the poor are more affected by reductions in public goods stressed as the consequences of tax evasion in our treatments, and they may respond to the emphasis in the charged treatment on personal effects of tax evasion rather than on its questionable nature.Footnote15 However, even if the issue resonates differently, an explanation of why the less well off respond by withdrawing from the electoral process, why there is a negative effect of the treatment on their participation, is needed. Lack of agency is an explanation which fits the mechanisms uncovered in . In addition, if voters see all parties as equally implicated in the Swiss leaks scandal, a reluctance to legitimise an election unlikely to improve their situation may also play a role.Footnote16 In terms of practical implications in contexts where vote buying occurs, while the poor may be more easily mobilised in elections through hand-outs, our results suggest that this would prove more costly to parties if the voters are more informed of questionable elite practices.

7. Conclusions

Information has the potential to mobilise or to alienate. The results from our survey experiment in Tanzania indicate that, in the context of an imperfect democracy, providing eligible voters with information on elite capture either has no effect or a negative effect on voting intentions. Information of this kind tends to reduce faith in the social contract and confidence in political institutions, highlighting the dysfunctions of the political system more than the importance of the election outcome. Our results add detail and nuance to previous experimental evidence suggesting that information on corruption decreases turnout (Chong et al., Citation2015). We show that the form of information matters; attempting to mobilise voters by stoking their moral indignation with questionable elite practices may backfire. Moreover, the citizens whose political participation is most negatively affected by charged information on elite use of tax havens tend to be the less well off, possibly reflecting a lower level of perceived agency.

Given the importance of elections in holding politicians and the elite accountable, our results raise important questions. In particular, how do you introduce matters of elite capture and elite-citizen relations into political debates in a way that increases rather than reduces citizen political participation? Our results suggest that incentives for candidates and parties to form around or campaign on such issues are limited in the context of our study, which is consistent with the widely noted absence of programmatic political parties with clear policy platforms in Africa (Chabal & Daloz, Citation1999; Van de Walle & Butler, Citation1999). Moreover, our results contrast with the positive effect of elite capture on turnout in highly democratic states uncovered in Kolstad and Wiig (Citationforthcoming). This suggests that there may be multiple equilibria in terms of democracy. In well-functioning democracies, voters challenge and effectively curtail attempts at elite capture through the electoral system. In less democratic states, evidence of elite capture makes voters withdraw, leaving room for even more capture which further undermines the electoral system.

Some limitations of our study should be noted. While we find information on elite capture to have no effect or a negative effect on voting intentions, it is possible that it could increase other forms of political participation. We have some data on other forms of participation and our results suggest this is not the case, but our analysis of this is not exhaustive. In terms of accountability, it would be important to not only look at effects on voter turnout, but also on party choice, to see how this type of information affects political competition and an incumbent’s probability of being re-elected. While we have data on party choice, too large a proportion of our respondents declined to answer this question for an analysis of this to be meaningful. This also means that we cannot assess whether information about elite capture affects supporters of the ruling party differently from supporters of the opposition. In terms of external validity, ethnicity is less politically salient in Tanzania than in other countries in the region, and it is possible that the effects would be different in countries where voting occurs more along ethnic lines. These are matters for further studies to pursue.

Supplementary Materials

Download PDF (333.2 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors thank Vincent Somville, Ingrid Hoem Sjursen, Kristina Bott, Annette Altvater, Linda Helgesson Sekei, Bertil Tungodden, Alexander Cappelen, Odd-Helge Fjeldstad, Ragnar Torvik, Sosina Bezu, two anonymous reviewers, and participants at the Midwest Political Science Association 75th Annual Conference in Chicago 2017, the PEDD conference in Münster 2017, the WIDER Development Conference ‘Public Economics for Development’ in Maputo 2017, the EADI Nordic Conference in Bergen 2017, the Development Studies Association 2016 conference in Oxford, the Nordic Conference in Development Economics 2016 in Oslo, the 11th Nordic Conference on Behavioral and Experimental Economics in 2016 in Oslo, and the Choice Lab seminar in Bergen in April 2016 for helpful inputs, comments and suggestions. We thank Development Pioneer Consultants for excellent data collection services, and DJPA for assistance in creating the videos used for the experiment. The data and Stata code for the analyses are available on request from the corresponding author. Financial support from the Research Council of Norway is gratefully acknowledged.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Both videos can be viewed online at http://www.cmi.no/news/1666-research-results, and the manuscripts for the videos are presented in Appendix A.

2. http://www.idea.int/vt/countryview.cfm?id = 227 (accessed 27 January 2016).

4. The Swiss leaks case was based on leaks from a former employee of the Swiss bank HSBC in 2008, the information was passed on to the French newspaper Le Monde in early 2014, and subsequently analysed and published by The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ). The leaked data identified bank accounts in HSBC of more than 100,000 citizens of 203 countries, totalling more than $100 billion, and a number of the account holders so far identified are from the elite of their respective countries, including royalty, politicians and top officials, wealthy industrialists and more. See http://www.icij.org/project/swiss-leaks for details (accessed 27 January 2016).

5. In making this adjustment, we depart from the intention to vote outcome variable specified in the pre-analysis plan. Our results also hold (and are in fact stronger) if we instead drop the respondents misrepresenting their behaviour from the sample (results reported in Table D3, columns 1 and 2, in the Supplementary Material).

6. The question on ballot box appearance was deemed to be answered correctly or incorrectly by our enumerators based on whether the respondent could describe its physical appearance somewhat accurately. The question of ballot sheet appearance was multiple choice with four options, only one of which accurately described the types of information that were on the ballot sheet.

7. See Table D1 in the Supplementary Materials.

8. Our treatments are balanced across important determinants of turnout identified by the existing literature, see Blais (Citation2006) and Cancela and Geys (Citation2016) for reviews.

9. In the same way as for the adjustment of the dependent variable, this is a departure from the pre-analysis plan.

10. This is more conservative than using one-sided tests specified in the pre-analysis plan, which does not specify the test to be used when the signs of the two treatment coefficients differ.

12. See Section D in the Supplemental Material for details, including balance of misrepresentation across treatments (Table D1), correlates of voting misrepresentation (Table D2) and results when the outcome variable is not corrected for misrepresentation (columns 3 and 4 in Table D3).

13. For details on the three indices, please see Section C in the Supplementary Material.

14. Patterns across other covariates were less robust and are not reported here.

15. Wantchekon (Citation2003) shows that voting is more influenced by benefits targeted at specific groups, rather than general improvements in public goods.

16. We thank an anonymous reviewer for this point.

References

- Achen, C., & Blais, A. (2016). Intention to vote, reported vote and validated vote. In J. A. Elkink & D. M. Farrell (Eds.), The act of voting: Identities, institutions, and locale (pp. 195–209). London: Routledge.

- Ali, N., & Lin, C. (2013). Why people vote: Ethical motives and social incentives. American Economic Journal: Microeconomics, 5(2), 73–98.

- Ansolabehere, S., Iyengar, S., Simon, A., & Valentino, N. (1994). Does attack advertising demobilize the electorate? American Political Science Review, 88, 829–838. doi:10.2307/2082710

- Banerjee, A., Green, D. P., McManus, J., & Pande, R. (2014). Are poor voters indifferent to whether elected leaders are criminal or corrupt? A vignette experiment in Rural India. Political Communication, 31(3), 391–407. doi:10.1080/10584609.2014.914615

- Barton, J., Castillo, M., & Petrie, R. (2016). Negative campaigning, fundraising, and voter turnout: A field experiment. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 121, 99–113. doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2015.10.007

- Bernard, T., Dercon, S., Orkin, K., & Taffesse, A. S. (2014). The future in mind: Aspirations and forward-looking behaviour in Rural Ethiopia (CSAE Working Paper WPS/2014-16). Oxford: Centre for the Study of African Economies.

- Blais, A. (2006). What affects voter turnout? Annual Review of Political Science, 9, 111–125. doi:10.1146/annurev.polisci.9.070204.105121

- Cancela, J., & Geys, B. (2016). Explaining voter turnout: A meta-analysis of national and subnational elections. Electoral Studies, 42, 264–275. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2016.03.005

- Chabal, P., & Daloz, J. P. (1999). Africa works. Disorder as political instrument. Oxford: James Currey.

- Chauchard, S., Klasnja, M., & Harish, S. P. (2017). The limited impact of information on political accountability: An experiment on financial disclosures in India (Unpublished manuscript). Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH.

- Chong, A., de la O, A., Karlan, D., & Wantchekon, L. (2015). Does corruption information inspire the fight or quash the hope? A field experiment in Mexico on voter turnout, choice, and party identification. Journal of Politics, 77(1), 55–71. doi:10.1086/678766

- Croke, K., Grossman, G., Larreguy, H. A., & Marshall, J. (2016). Deliberate disengagement: How education decreases political participation in electoral authoritarian regimes. American Political Science Review, 110(3), 579–600. doi:10.1017/S0003055416000253

- DellaVigna, S., List, J., Malmendier, U., & Rao, G. (2017). Voting to tell others. Review of Economic Studies, 84(1), 143–181. doi:10.1093/restud/rdw056

- Downs, A. (1957). An economic theory of democracy. New York: Harper & Row.

- Feddersen, T., & Sandroni, A. (2006). A theory of participation in elections. American Economic Review, 96(4), 1271–1282. doi:10.1257/aer.96.4.1271

- Ferraz, C., & Finan, F. (2008). Exposing corrupt politicians: The effects of Brazil’s publicly released audits on electoral outcomes. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123(2), 703–745. doi:10.1162/qjec.2008.123.2.703

- Fridkin, K. L., & Kenney, P. J. (2011). Variability in citizen’s reactions to different types of negative information. American Journal of Political Science, 55(2), 307–325. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5907.2010.00494.x

- Global Financial Integrity. (2017). Illicit financial flows to and from developing countries: 2005–2014. Washington, DC: Author.

- Hong, Q., & Smart, M. (2010). In praise of tax havens: International tax planning and foreign direct investment. European Economic Review, 54, 82–95. doi:10.1016/j.euroecorev.2009.06.006

- Isaksson, A. S. (2014). Political participation in Africa: The role of individual resources. Electoral Studies, 34, 244–260. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2013.09.008

- Isaksson, A. S., Kotsadam, A., & Nerman, M. (2014). The gender gap in African political participation: Testing theories of individual and contextual determinants. Journal of Development Studies, 50(2), 302–318. doi:10.1080/00220388.2013.833321

- Johannesen, N., Tørsløv, T., & Wier, L. (2016). Are less developed countries more exposed to multinational tax avoidance? Method and evidence from micro-data (WIDER Working Paper 2016/10). Helsinki: UNU-WIDER.

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47, 263–292. doi:10.2307/1914185

- Kolstad, I., & Wiig, A. (2016). Education and electoral participation: Reported versus actual voting behaviour. Applied Economics Letters, 23(13), 908–911. doi:10.1080/13504851.2015.1119785

- Kolstad, I., & Wiig, A. (forthcoming). Elite behaviour and citizen mobilization. European Journal of Political Research.

- Kramon, E. (2016). Electoral handouts as information – Explaining unmonitored vote buying. World Politics, 68(3), 454–498. doi:10.1017/S0043887115000453

- Kurer, O. (2001). Why do voters support corrupt politicians? In A. K. Jain (Ed.), The political economy of corruption (pp. 63–86). London: Routledge.

- Lau, R. R., Sigelman, L., & Rovner, I. B. (2007). The effects of negative political Campaigns: A meta-analytic reassessment. Journal of Politics, 69(4), 1176–1209. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2508.2007.00618.x

- Loomes, G., & Sugden, G. (1982). Regret theory: An alternative theory of rational choice under uncertainty. Economic Journal, 92(368), 805–824. doi:10.2307/2232669

- Morton, R. (1991). Groups in rational turnout models. American Journal of Political Science, 35, 758–776. doi:10.2307/2111565

- Ravallion, M., van de Walle, D., Dutta, P., & Murgai, R. (2015). Empowering poor people through public information? Lessons from a movie in rural India. Journal of Public Economics, 132, 13–22. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2015.09.010

- Riker, W. H., & Ordeshook, P. C. (1968). A theory of the calculus of voting. American Political Science Review, 62, 25–42. doi:10.2307/1953324

- Schjelderup, G. (2016). Secrecy jurisdictions. International Tax and Public Finance, 23(1), 168–189. doi:10.1007/s10797-015-9350-7

- Seabrooke, L., & Wigan, D. (2016, May 6). The Panama Papers and corporate tax reform: How the leaks created a window of opportunity. Foreign Affairs. Retrieved from https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/europe/2016-05-06/panama-papers-and-corporate-tax-reform

- Shachar, R., & Nalebuff, B. (1999). Follow the leader: Theory and evidence on political participation. American Economic Review, 89(3), 525–547. doi:10.1257/aer.89.3.525

- Uhlaner, C. (1989). Rational turnout: The neglected role of groups. American Journal of Political Science, 33(2), 390–422. doi:10.2307/2111153

- Van de Walle, N. (2003). Presidentialism and clientelism in Africa’s emerging party systems. Journal of Modern African Studies, 41(2), 297–321. doi:10.1017/S0022278X03004269

- Van de Walle, N., & Butler, K. (1999). Political parties and party systems in Africa’s illiberal democracies. Cambridge Review of International Affairs, 13(1), 14–28. doi:10.1080/09557579908400269

- Wantchekon, L. (2003). Clientelism and voting behavior: Evidence from a field experiment in Benin. World Politics, 55, 399–422. doi:10.1353/wp.2003.0018

- Zucman, G. (2014). Taxing across borders: Tracking personal wealth and corporate profits. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 28(4), 121–148. doi:10.1257/jep.28.4.121

Appendix A.

Manuscripts – treatment videos

Neutral video

‘Have you heard about the Swiss billions?

99 Tanzanians sent 205 billion Shillings to bank accounts in Switzerland in 2006/2007.

Wealthy people and big companies in Tanzania send money to many countries like Switzerland – countries we call tax havens.

By sending money to these countries, rich people pay less taxes to Tanzania.

When wealthy people send money abroad in this way and pay less taxes, tax revenues in Tanzania are reduced.

Taxes are spent on building and improving public services and infrastructure like schools, hospitals and roads.

When wealthy people pay less taxes, the government has less money to spend and cannot provide good schooling – there are no desks for classrooms and teachers become scarce.

Health services suffer, too – with less available medicines in the clinics and fewer doctors to consult with patients.

Tanzania could be able to afford better public services for its people, if wealthy people did not send billions to Switzerland and other tax havens.’

Charged video

‘Have you heard about the Swiss billions?

99 Tanzanians sent 205 billion Shillings to bank accounts in Switzerland in 2006/2007.

Wealthy, greedy people and big companies in Tanzania are hiding money in overseas bank accounts in countries like Switzerland – countries we call tax havens.

By sending money to these countries, wealthy people get richer by avoiding to pay the taxes that we are all supposed to pay.

When wealthy people send money abroad in this way they do not pay the required amount of taxes, therefore tax revenues in Tanzania are reduced.

Taxes are spent on building and improving public services and infrastructure like schools, hospitals and roads.

When wealthy people pay less taxes, the government has less money to spend and cannot provide good schooling for your children, there will be no desks for classrooms and teachers become scarce.

Health services for your family will suffer, too – with less available medicines in the clinics and fewer doctors to consult with patients.

Tanzania could be able to afford better public services for you and all, if wealthy people did not send billions to Switzerland and other tax havens.

These greedy, wealthy people don’t do any justice to you or other Tanzanians!’

Appendix B.

Table B3. Balance treatments and control