?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This study relies on a unique precrisis baseline and five-year follow-up to investigate the effects of emergency school feeding and generalised food distribution (GFD) on children’s schooling during conflict in Mali. It estimates programme impact on child enrolment, absenteeism, and attainment by using a difference in differences weighted estimator. School feeding led to increases in enrolment by 10 percentage points and to around an additional half-year of completed schooling. Attendance among boys in households receiving GFD, however, declined by about 20 per cent relative to the comparison group. Disaggregating by conflict intensity showed that receipt of any food assistance led to a rise in enrolment mostly in high-intensity conflict areas and that the negative effects of GFD on attendance were also concentrated in the most affected areas. School feeding mostly raised attainment among children in areas not in the immediate vicinity of conflict. Programme receipt triggered adjustments in child labour. School feeding led to lower participation and time spent in work among girls, while GFD raised children’s labour, particularly among boys. The educational implications of food assistance should be considered in planning humanitarian responses to bridge the gap between emergency assistance and development by promoting children’s education.

1. Introduction

In 2016, at least 357 million children (one child in six globally) were living in conflict-affected states, and the number had been steadily rising since the 2000s (Bahgat et al., Citation2017). Conflicts and exposure to violence can have devastating effects on children’s education, health, and overall well-being, with long-term repercussions on children’s life course outcomes, as well as on the next generation (Akbulut-Yuksel, Citation2014; Akresh, Bhalotra, Leone, & Osili, Citation2017; Blattman & Miguel, Citation2010; Justino, Leone, & Salardi, Citation2014; Shemyakina, Citation2011).

Social protection is increasingly seen as a tool to build human capital and reduce poverty during humanitarian crises, potentially bridging the gap between emergency responses and long-term development (Ulrichs & Sabates-Wheeler, Citation2018). Food assistance constitutes 40 per cent of total humanitarian spending (World Food Programme [WFP], Citation2017). School feeding has been scaled up in emergencies as a rapidly deployable safety net, while generalised food distribution (GFD) is the largest component (25–30 per cent) of total humanitarian assistance globally (Harvey, Proudlock, Clay, Riley, & Jaspars, Citation2010; WFP, Citation2013). Despite the critical role of social protection during emergencies, evidence on the impacts on child education is thin, particularly with regards to food assistance (Doocy & Tappis, Citation2016). Additional knowledge gaps relate to whether the educational effects of social protection in conflict vary by type of programme, child gender, and conflict intensity. This lack of evidence hinders the design of context- and child-sensitive responses that can promote human capital accumulation, particularly in protracted fragility. Also, these evidence gaps translate into a significant funding mismatch. For instance, the education sector only receives 2 per cent of total humanitarian aid (Justino, Citation2016).

This study investigates the educational impacts of emergency food assistance during the recent conflict in Mali. Since February 2012, the country has experienced a series of political crises, which have compounded the high levels of food insecurity. Strengthening the educational impacts of humanitarian response is critical in Mali, where over half the 14.5 million inhabitants are children ages under 15. Primary schooling completion and youth literacy rates are among the lowest globally. One person in two ages 15–24 cannot read a basic sentence (World Development Indicators [WDI], Citation2017). Relying on a unique precrisis baseline and longitudinal follow-up, the analysis estimated the effects of emergency school feeding and GFD on educational outcomes among children in Mopti, central Mali, through a weighted difference in differences estimation.

This appears to be the first study that provides quasi-experimental evidence on the impacts of the most common form of emergency assistance, GFD, on child education in conflict. The focus on the comparative effectiveness of GFD and school feeding is also novel and complements the contributions of Schwab, Brück, and colleagues in this special issue. The study thus adds to the limited evidence on the impact of social protection on education in humanitarian settings that, to date, has mostly focused on cash-based approaches (Doocy & Tappis, Citation2016; United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees [UNHCR], Citation2017; Wald & Bozzoli, Citation2011). The study also adds to the literature by providing disaggregated estimates of programme impacts by gender and by the intensity of conflict exposure. It examines changes in child labour participation and duration as mechanisms linking food assistance receipt and education outcomes.

2. Emergency food assistance and schooling: conceptual framework

In nonhumanitarian contexts, investments in child schooling are part of household decisions related to the time allocation of different members, poverty and other contextual constraints, perceived returns to education, educational quality, and social norms. Social protection programmes such as school feeding and GFD can support child education by reducing poverty, enabling access to educational services, paying for school fees and other educational supplies, and decreasing the opportunity costs of schooling (Holmes, Citation2011). School feeding programmes offer a free meal, a snack, or a take-home ration to children attending school, while GFD involves the provision of a basic food ration to vulnerable households (Barrett, Citation2006). In particular, school feeding may directly benefit children’s schooling through two main pathways (Adelman, Gilligan, & Lehrer, Citation2009). The first involves increased enrolment and attendance through an income transfer to households that is equivalent to the size of the meal or ration. The transfer is conditional on school attendance. By subsidising the opportunity cost of schooling, school feeding can decrease the time children spend in productive activities within or outside the household and promote shifts in time use to activities that are more compatible with school attendance. The net effect of school feeding on attendance depends on the ratio between the value of the transfer and the expected differences between the cost and benefits of attending school on a given day. The second pathway relates to improved nutritional status and decreased morbidity, which may lead to an expansion in attendance and learning ability, for example, through enhanced cognition.

Compared with school feeding, the links between GFD and household decisions on child schooling in nonhumanitarian contexts are less direct. The school attendance pathway embedded in the design of school feeding may not apply in the case of GFD because these programmes do not typically include any explicit schooling conditionality. Decisions along the health pathway may also be more tenuous than in school feeding, depending on the way households allocate food among household members. One may hypothesise that GFD may positively influence household educational decisions by freeing up labour and financial resources that would otherwise be employed in food- or income-generating activities. For instance, in Ethiopia, GFD promoted schooling among younger boys after a drought (Broussard, Poppe, & Tekleselassie, Citation2016). On the other hand, families receiving GFD may use the savings from food purchases to invest in productive activities in which children participate, thus increasing the returns to child labour and potentially reducing school attendance.Footnote1 Similarly, changes in local food production or in prices following GFD may lead to an increased participation of children in agriculture or work directly or indirectly related to GFD (such as queuing at collection points, reselling food rations, or performing farm or care work in place of other household members who are busy obtaining GFD).

During conflict and other emergencies, the opportunity costs of schooling may rise even more because child labour is a common coping strategy in the face of shocks – such as the loss of productive assets or of household labour following armed violence, looting, or the recruitment of household members in the army – that add to the difficulties associated with poverty and poorly functioning labour markets (Akresh & de Walque, Citation2008; Buvinić, Das Gupta, & Shemyakina, Citation2014; Shemyakina, Citation2011). Fear and insecurity constitute additional barriers to children’s education during conflict (Justino, Citation2016). During humanitarian crises, school feeding serves additional objectives linked to child protection, dignity, and normalcy that may sometimes override the more general goals of promoting schooling and health (WFP, Citation2007). In these contexts, school feeding can be used to assist in the restoration of education systems, to encourage the return of internally displaced persons (IDPs), and to promote social cohesion (Harvey et al., Citation2010).

While the positive effects of school feeding on schooling are supported by a well-established literature on nonhumanitarian settings (see Drake et al., Citation2018, for a review), the evidence on the effectiveness of school feeding in emergencies is extremely limited. A field experiment assessed the impact of a World Food Programme (WFP) initiative involving school feeding and take-home rations on school participation in camps for IDPs in northern Uganda (Alderman, Gilligan, & Lehrer, Citation2012). The experiment showed that school feeding had a positive impact on school enrolment and attendance. There is no literature on the positive effects of GFD on education in emergency settings, however, despite the primary relevance of GFD in humanitarian responses.

The overall effects of both forms of food assistance on child schooling in conflict may also vary by gender. A large literature has documented that conflict has differential effects on schooling by gender based on a number of contextual factors, such as the extent of child participation in education and labour, perceived returns to schooling, the prevalence of child enlistment in the army, and social norms (Buvinić et al., Citation2014). Depending on gendered child labour patterns and related differentials in the opportunity cost of schooling, food assistance may lead to differential impacts on the schooling of boys and girls.

The educational effects of school feeding and GFD may vary with conflict intensity, too. The literature on the educational impacts of conflict highlights that children experiencing greater conflict intensity tend to exhibit lower educational outcomes (Akbulut-Yuksel, Citation2014; Wald & Bozzoli, Citation2011). Conflict intensity may influence the overall educational effects of emergency social protection in ways that are not known a priori. The overall effect will depend on the manner in which emergency responses are targeted (for example, towards areas that are more or less affected by the conflict events) or on some conditionality that is present, such as the distribution of take-home rations only among specific groups. Also, school feeding may not always represent a viable solution in high-intensity conflict areas where schools are closed or other operational constraints impede implementation. The effects of school feeding on child schooling during conflict may depend on implementation quality. A thematic evaluation of the WFP school feeding operations in emergencies identified a range of context-specific challenges related to implementation, including security, limited accessibility, and weak in-country capacity, which add to the operational constraints usually present in development settings (WFP, Citation2007).

Additional demand-side factors may affect the receipt by households of food assistance according to the intensity of conflict (Wald & Bozzoli, Citation2011). For instance, if households anticipate that schools will be targeted by violence because they receive food, they may keep children at home, and school participation may increase less in areas where conflict is more intense. Meanwhile, if households in areas of greater conflict intensity suffer from larger economic hardships relative to households in areas of lower conflict intensity, programme transfers may lead to increased schooling and to additional time spent in school. These factors may also interact with the gender of the child. For instance, in the case of school feeding, even if communities are exposed to the same level of conflict intensity, there may be reasons that vary systematically between boys and girls that can hamper programme participation among one gender. For example, fear of sexual violence on the way to school may lower the participation of girls, while fear of abduction by the army may have the same effect among boys.

Thus, the educational impacts of food programmes in conflict situations are far from defined a priori. The study hypothesises that school feeding, because it is conditional on school attendance, is more protective of child schooling in situations of conflict relative to GFD. However, the net effect of both programmes on education outcomes depends on a number of factors, including implementation, conflict intensity, gender patterns of schooling and work, and gendered perceptions of violence. The remainder of this report assesses the extent to which both types of transfers are able to protect households and children from the detrimental schooling impacts of conflict in the Malian context.

3. Background

3.1. The 2012–2013 crisis in Mopti, central Mali

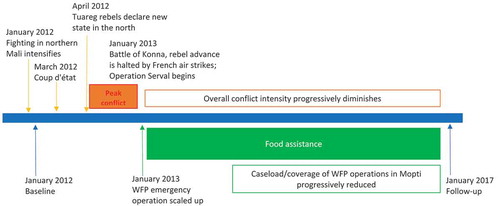

Mali has witnessed various Tuareg rebellions before and since independence, including in 1963, 1992, 2007, and since 2012 (Tranchant et al., Citation2018). Before 2012, these conflicts primarily took place in northern Mali. Mopti – similar to much of central Mali – was not directly exposed (International Crisis Group [ICG], Citation2016). During the 2012 crisis, however, parts of the Mopti region were occupied by Tuareg rebel groups, such as the Mouvement National pour la Libération de l’Azawad, and by Islamist groups, and the region was host to widespread violence between 2012 and 2013 (). As a result, government services and development programmes were interrupted, and public servants fled the region, which was already characterised by substantial economic and political fragility. The conflict caused large-scale internal displacement and the closure of public infrastructure, including schools and health centres. About 40,000 persons were displaced in Mopti in 2012 (International Displacement Monitoring Centre [IDMC], Citation2012). The deployment of the French military operation Serval put a stop to the advance of the rebels, who were eventually pushed out of Mopti, in April 2013. The government of Mali gradually re-established control over Mopti, and the number of IDPs drastically declined. In 2016, the number of IDPs in Mopti was reduced to 2,150 (United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs [UNOCHA], Citation2018). In a survey conducted for this study in December 2017, fewer than 1 per cent of the respondents declared that they had been displaced at any point between 2012 and 2017 by the conflict.

Yet, the conflict aggravated the already precarious situations among rural households in Mopti and, combined with a drought, created a complex emergency situation.Footnote2 Furthermore, when government forces returned in 2013, the re-establishment of the state did not result in greater security, nor did it improve the relations between state representatives and local populations. Military, social, and political tensions escalated from 2015 onward, and Mopti is currently the site of an increasingly violent and complex conflict (Tranchant, Gelli, & Masset, Citation2019). Armed groups are still active, and an international military operation is ongoing.Footnote3

3.2. Food assistance provision in 2014–2015

Following the liberation of the occupied zones and a relative return to normalcy, the government and its partners, including WFP, implemented several humanitarian interventions. The WFP intervention in northern and central Mali included two main operations. The first, focused on drought relief, was launched in late January 2013 and ended in 2014. A subsequent programme was implemented to continue to provide assistance during 2015 and 2016, though on a considerably smaller scale. This programme included GFD, consisting of a household ration of cereals, pulses, vegetable oil, and salt, along with fortified super cereal to increase micronutrient intake. GFD was thus undertaken at the beginning of the emergency operation.

During the crisis, children in school received school feeding implemented by the government, WFP, and other development partners (WFP, Citation2015). Daily hot lunches of cereals, pulses, and vegetable oil, complemented with local condiments, were provided throughout the school year as an incentive for parents to enrol and keep their children in school. Before the crisis, the programme was implemented by the government and targeted all primary school children in the country’s 166 food insecure communes (third-level administrative units). Governmental targeting was also based on low enrolment rates (of girls, particularly) and the greatest household distances to school. During the crisis, WFP and other partners relied on the government’s geographical targeting, which rendered programmatic delivery and implementation feasible.

WFP food assistance in Mopti also included targeted supplementary feeding and food-for-work initiatives, although coverage was limited relative to school feeding and GFD. Online Supplementary Appendix A provides a detailed timeline and information on the coverage of WFP food assistance, as well as a description of WFP activities. Overlaying the study villages in the maps on coverage suggests that the study population was exposed to varying degrees of humanitarian assistance (see Supplementary Appendix A, Figure SA.A.1). The exact targeting mechanism of villages and households is unclear. Discussions with WFP staff and regionwide aid distribution statistics suggest that targeting and coverage may have been implemented based on the viability of the delivery of assistance, which was often impeded by armed groups that delayed or blocked access to roads in certain areas. There was also some temporal variability in the mean coverage of WFP activities across regions (Supplementary Appendix A, Figure SA.A.2). (For a timeline of conflict events and subsequent food assistance, see .)

4. Sample

The study used a unique panel dataset with information on households and villages. The baseline survey was collected before the crisis in January 2012 as part of a cluster-randomised trial of school feeding in Mali. The trial was then interrupted because of the onset of conflict a month after the baseline (Masset & Gelli, Citation2013). Seventy villages were randomly sampled among the most food-insecure communes in Mopti on the basis of two villages within each sample commune. In each village, 25 households were randomly sampled for the survey interviews. The baseline survey collected detailed information on household food security, economic activities, sociodemographic indicators, and the anthropometry and educational outcomes of every child (Masset & Gelli, Citation2013). The end line survey was undertaken in January 2017 and included most of the initial questions, along with additional modules related to conflict and aid in both household and village surveys. Qualitative research was also conducted at end line with key government and humanitarian stakeholders in Bamako, the capital, and stakeholders and households in Mopti, with the aim of reconstructing a timeline of conflict and aid. Educational issues were only mentioned by some participants. Whenever this information is available, it is reported.

At end line, four of the baseline villages and 91 related households could not be reached because of ongoing conflict.Footnote4 In total, 210 households had been lost at follow-up, leading to an overall attrition rate of 22 per cent over the five-year study if the four villages are included that could not be reached at end line or 15 per cent if these villages are excluded. Considering the relatively long follow-up and the large internal displacements occurring during conflict, these attrition rates were, to a certain extent, expected. presents descriptive statistics on baseline households and village characteristics by attrition status and also by distinguishing whether the households belong to a village that was successfully resurveyed. There were a few characteristics that predicted tracking, which, however, were mostly common between the two sets of households. Generally, households that were successfully tracked in follow-up villages (column 1) were larger, less likely to belong to higher consumption expenditure quartiles, and more likely to belong to the main ethnic group (Dogon) and to be polygamous than households that were not tracked in resurveyed villages (column 2) or that belonged to villages that could not be reached at endline because of the ongoing conflict (column 4). The latter had more animals and were in more remote villages that had less educational infrastructure and were less likely to have hosted a past development project. Yet, at baseline, they perceived their villages as safer than households from villages that were successfully tracked. investigates predictors of attrition further by presenting baseline household and village predictors of household tracking among households that were resurveyed and for all baseline households. Again, few household and village characteristics predicted tracking.

Table 1. Household and village characteristics at baseline

Table 2. Baseline predictors of the five-year tracking of households and villages on which there was complete information at follow-up and all baseline villages

5. Identification strategy

Among households, exposure to conflict and the receipt of food assistance are likely to be non-random.Footnote5 The identification of the impact of food assistance on children’s education therefore presents challenges related to the absence of a counterfactual, endogenous programme placement, and self-selection into food assistance, which can lead to selection bias. The analysis addresses these challenges through a weighted difference in differences approach to estimate the average effect of food assistance on households that received it, that is, the average treatment effect on the treated (ATT) (Heckman, Ichimura, & Todd, Citation1998; Hirano, Imbens, & Ridder, Citation2003). Through propensity score matching, the analysis estimates the probability that a household receives food assistance P(A), conditional on a range of baseline household and village characteristics (X) that may be related to both the selection into treatment and child educational outcomes [X: P (X) = P (A = 1|X)]. Rosenbaum and Rubin (Citation1983) show that, if one controls fully for selection on observable characteristics, the conditional outcomes are independent of treatment status, and the ATT is identified (unconfoundedness assumption). The weight, , is calculated as

for treatment subjects and as

for control subjects, where

is the estimated propensity score for household h. The use of the inverse probability weights adjusts for the systematic imbalances in observable covariates between treatment and comparison households so that the difference in differences estimator weighted by the kernel propensity score provides an unbiased estimate of the ATT under the unconfoundedness assumption. To improve the quality of the match, the analysis restricts the matching to the region of common support. The use of the weighted difference in differences estimator removes differences between treatment and control groups in terms of observable and unobservable time-invariant characteristics that may be associated with the receipt of food assistance and with educational outcomes. This strategy remains vulnerable to the presence of unobservable time-varying characteristics that are correlated to both food assistance and educational outcomes. A key issue is that the presence of armed groups is itself determined by the coverage of food assistance (Gelli & Tranchant, Citation2018). To minimise this bias, the analysis examines the effect of aid over 2014–2016, while controlling for the presence of armed groups in 2012–2014.

The analysis first estimates treatment effects on the full longitudinal household sample on the basis of the underlying hypothesis that households in communes or villages not directly occupied by armed groups may nonetheless be affected by the conflict. The probability of a household receiving food assistance was estimated with a probit estimator by restricting the longitudinal sample to the villages that were successfully resurveyed at end line. The following variables were created: any aid, to measure whether a household received any food assistance, including school feeding, GFD, targeted supplementary feeding, and food-for-work; receipt of school feeding; and receipt of GFD. (See Supplementary Appendix B for descriptive statistics on food assistance.) Given the low coverage of supplementary feeding and food-for-work, the analysis does not estimate the impact of these programmes separately.

The analysis models the probability of a household receiving food assistance through the following baseline household characteristics: the age of the household head, household membership in the main ethnic group, household consumption expenditure quartile, household size, dependency ratio, number of school-age children, number of food groups consumed in the previous week, share of food expenditures in total expenditure, polygamous household, household head identified as a wage worker, amount of cultivated land, and number of livestock. The following baseline village characteristics are also included: presence of secondary school and market within five kilometres, presence of a development project, unsafe village, village conflict exposure during 2012–2014, and school infrastructure and school governance indices. (See Supplementary Appendix C for details on the construction of these indices.)

To disentangle the relationship between exposure to conflict and receipt of food assistance, the analysis focuses only on conflict events in the aftermath of the coup, when civil unrest was at its peak (2012–2014), and evaluates the impact of food assistance only in the subsequent period (2014–2016). The probability that a household received food assistance during 2014–2016 is thus estimated based on 2012 household and village characteristics and exposure to conflict (in communes and villages) during 2012–2014.

The analysis focuses on the following outcomes among compulsory school-age children (7–16): school enrolment; attendance measured by the number of days of absence of the child from school during the previous five-day school week (conditional on enrolment); and grade attainment, as measured by the number of years of formal education the child has completed.

Equation 1 presents the regression-equivalent of the difference in differences model with weighting based on the estimated propensity score:

where relates to the vector of educational outcomes of child i in household h at time t, when the household receives food assistance type a.

is the time trend; it is equal to 1 for the end line, zero otherwise.

is an indicator variable for the household receipt of food assistance type a. The parameter of interest is

, the treatment effect on each educational outcome for food assistance a at end line.

is a vector of child-level controls (age, male, whether the child is the oldest child in the household, and a variable taking the value 1 if the oldest child is male and 0 otherwise) to increase the precision of the difference in differences estimates. These covariates were chosen because they may all influence schooling and labour (Edmonds, Citation2007).

is a vector of standard errors. Because analytical standard errors are not known for most matching estimators, inference must rely on standard errors constructed by bootstrap, which, in this case, are estimated through 50 replications. Food assistance is evaluated at the household level rather than at the village level. Therefore, the analysis does not perform wild bootstrapping methods to control for a potentially low number of clusters, as suggested by Cameron and Miller (Citation2015). It is not clear whether this approach would solve the issue in difference in differences estimations (MacKinnon & Webb, Citation2018). A similar approach is undertaken by Gilligan, Hoddinott, and Taffesse (Citation2009) in evaluating emergency food assistance in Ethiopia. Also, the number of villages in this report is 66, whereas Cameron and Miller (Citation2015) state that potentially problematic cases in panel data relate to fewer than 50 clusters, which reassures about the robustness of the approach here. However, in a robustness check, the analysis assesses whether clustering standard errors at the village level affects the results because of the potentially clustered nature of the sample (Abadie, Athey, Imbens, & Wooldridge, Citation2017). All estimates were undertaken with Stata 15.1 using the diff command (Villa, Citation2017). (Data and code are available upon request.)

The analysis estimates treatment effects by gender and conflict intensity. In both cases, it separately estimates the propensity scores and balance in baseline covariates for each subgroup. It measures conflict intensity by using village data to limit potential endogeneity in the likelihood of a household reporting conflict-related violence and food assistance receipt. It generates a categorical variable that assumes the value of 0 if no armed groups were present in the village or the commune between 2012 and 2017, 1 if the armed groups were present in the commune surrounding the village, and 2 if the armed groups were present in the village.

As a robustness check, the estimates are rerun by including the full set of baseline villages in the estimation of the propensity score. Furthermore, because fewer than 5 per cent of households received both GFD and school feeding (Supplementary Appendix B), the analysis checks whether this issue may affect the results by including the receipt of school feeding as one of the covariates in the regressions for the propensity score in the estimates related to the impact of GFD, and, vice versa, it includes the receipt of GFD as a covariate in the propensity score for the impact estimates related to school feeding. Another concern could be the extent to which school closures or the flight of teachers after peak conflict could potentially affect impact estimates. Only 3 per cent of children reported they were not able to return to school because of each of these instances, and there were no differences in reporting school closures or absent teachers by food assistance type (available upon request). Given the overall low prevalence of these occurrences and the absence of substantial differences between the two food assistance modalities, the analysis does not address the issue of school closures or the flight of teachers directly in the estimates.

6. Descriptive statistics

6.1. Food assistance and conflict

Supplementary Appendix D presents baseline household and village predictors of food assistance receipt at end line. Households belonging to the Dogon ethnic group were less likely to receive GFD, and households with more land were less likely (but weakly so) to receive school feeding. Households in villages that hosted past developmental projects showed a greater likelihood of receiving all types of aid, while a lack of safety at baseline was associated with a lower probability of receiving GFD. This result corroborates the idea that targeting may have been implemented based on the viability of delivering assistance.

describes food assistance by conflict intensity. (For descriptive statistics on conflict intensity and a discussion of correlates of exposure to conflict, see Supplementary Appendix E.) Households in villages without the presence of armed groups were generally more likely to gain access to any type of food assistance relative to households in areas in which armed groups were present in the commune or the village. In villages occupied by armed groups, GFD was more common than school feeding; this may have been caused by difficulties in implementing school feeding in these areas.

6.2. Schooling during conflict

Primary education in Mali is provided free of charge and is compulsory among children ages 7–16. presents descriptive statistics on schooling among children of compulsory school age. Given that the analytical sample is restricted to the longitudinal household (and not the child) sample, there is a discrepancy in the sample size at the two survey waves.Footnote6

Table 3. Descriptive statistics of child enrolment, grade attainment, and absenteeism, by survey round and child gender

School enrolment was 48 per cent at baseline and 40 per cent at end line, which is well below the national average of 57 per cent in 2015 (WDI, Citation2017). The largest reductions were among boys. The proportion of school days missed in the week previous to the survey doubled from baseline to end line; boys showed the largest increases in absenteeism. Grade attainment increased slightly at follow-up (also because of the longitudinal design), though the overall levels remained extremely low: the average child in both surveys had not completed two years of education. In both rounds, the most common reasons mentioned for children to be out of school included work, young age, lack of interest in education, and parental refusal to send children to school. There were gender differences in the reasons for non-participation in school. Farm-related activities were mentioned more often by boys, while early marriage and social norms were mentioned only by girls. In focus groups, it emerged that a feeling that the state had abandoned them (especially prevalent in villages occupied by armed groups) led some of the boys to join rebel groups.

presents educational outcomes by household receipt of food assistance, including children with access to any type of aid. Children in households receiving school feeding were more likely to be enrolled than children in other groups. They were also more likely to spend more years in school and to be absent from school less often than their peers from households not receiving school feeding. Girls in households receiving any type of food assistance were more likely to be enrolled than boys.

Figure 3. Mean educational outcomes at end line among school-age children (ages 7–16), by gender and type of food aid.

Notes: Enrolment is a binary indicator indicating whether the child was currently enrolled in school; absenteeism is measured as the number of days the child was absent in the five-day school week previous to the survey; grade attained is measured as the number of years of education completed. Any aid, school feeding, and food aid are dichotomous variables related to the receipt of any food aid type, school feeding, and food aid, respectively, in the 24 months previous to the survey.

7. Treatment effects

7.1. Main results

In the full sample, the estimated densities of propensity scores between treatment and comparison groups displayed a high degree of overlap across all assistance modalities (Supplementary Appendix F, Figures SA.F.1–SA.F.3). Supplementary Appendix F, Tables SA.F.1–SA.F.2, shows standardised differences in baseline covariates and schooling outcomes between treated and untreated households before and after application of the propensity score weights. After weighting, all the standardised differences were below 10 per cent, which is the threshold for problematic imbalances (Austin, Citation2009). The study concludes that weighting was effective in eliminating observable sources of selection bias. Separate balance analyses for the subsamples of boys and girls highlighted no differences above the threshold for unbalanced covariates (available upon request).

reports impact estimates for education. School feeding had a positive impact on enrolment; there was an increase of about 10 percentage points in the probability of enrolment among treatment children relative to children in households in the comparison group. This is a large increase, particularly in light of the low enrolment rates. School feeding also positively affected grade attainment; treated children achieved an average of more than an additional half-year of education compared with comparison peers. The school feeding effect was slightly larger among girls.

Table 4. Impact of food assistance on child education, full sample and stratified by gender

By contrast, the receipt of GFD did not change enrolment and had a negative, but not significant effect on grade attainment. The receipt of GFD increased absenteeism by more than a half school-day per week. This result was driven by boys: on average, boys in households receiving GFD were absent almost one full additional day per week (an increase of 20 per cent over boys in the control group), while, among girls, the point estimate was positive, but not statistically different from zero. All robustness checks are reported in Supplementary Appendix G.

7.2. Heterogeneity, by conflict exposure

presents treatment effects by conflict intensity, that is, no armed groups, armed groups in communes, and armed groups in communes or villages. There were numerous unbalanced covariates in the subgroup of villages occupied by armed groups, most likely because of the small number of observations involved. This group was therefore excluded from the estimates. The two conflict-affected subgroups – villages in which rebels were present in communes or villages – were thus merged into a single group, for which the balance of matched covariates was satisfying. Overall, any type of assistance received had a positive effect on enrolment only in the case of households in occupied communes, which showed a 12 percentage point increase in the probability of enrolment. There was no impact of school feeding on enrolment in any of the three groups. School feeding had no statistically significant effects on absenteeism in conflict-affected subgroups, but it increased grade attainment in villages indirectly affected by conflict events; the average increase was about 0.6 additional school years.

Table 5. Impact of food assistance on child education, by intensity of exposure to conflict

The negative effect of GFD on school attendance observed in the full sample was largely driven by the villages most directly affected by conflict. While GFD had no effect on child absenteeism in villages where no armed groups were present, the receipt of GFD led to increases of 0.4 and about 0.8 additional absentee days where, respectively, armed groups were present in the communes and armed groups were present in the communes or villages.

7.3. Exploring pathways of impact: child labour

Child labour is an important response strategy in the face of severe adverse shocks, potentially leading to increased absenteeism and dropouts. For instance, using data on northern Mali before the political crisis, Dillon (Citation2013) documents that households adjusted child labour in response to large production shocks, leading to increases in the probability of withdrawal from school by 11 per cent and participation in farm work by 24 per cent, but does not report gender heterogeneity in these effects. Treatment effects on schooling show that the two programmes had diverging impacts on child education: school feeding had a large effect on enrolment rates and attainment, while GFD appeared to increase absenteeism. The impacts of both programmes on education also varied by child gender. By using the same estimation strategy, the study tests whether changes in child labour by type of food assistance may explain the differential effects of school feeding and GFD on schooling, as well as the observed gender differences in attendance induced by GFD.

illustrates the treatment effects of food assistance on participation in labour (panels a.1–c.1) and the duration of work (panels a.2–c.2). (See Supplementary Appendix H for details on child labour measurement and descriptive statistics by gender.) There are three main findings. First, consistent with the educational results, the receipt of GFD led to marked increases in the probability of participating in any type of work activity by about 12 percentage points among the full sample, which translated into about an additional month of work in any activity in the previous year (panel a.2). Though treatment effects for school feeding were suggestive of a protective effect, that is, a decline in participation and time spent in labour, the coefficients were not statistically significant.

Table 6. Impact of food assistance on child labour, full sample and stratified by gender

Second, large gender heterogeneities were present. Although GFD increased the probability of any work involvement in the full sample, this effect appears to have been driven by boys (, panel a.1). Boys in GFD households showed a 20 percentage point increase relative to comparison peers in the likelihood of involvement in any work activities. The treatment effect among girls in GFD was also positive, but the point estimate was smaller compared with boys and only significant at 10 per cent. Receiving GFD translated to about 1.5 additional months spent by boys in all work activities (panel a.2). By contrast, school feeding decreased the participation of girls in any labour by about 10 percentage points, which accounted for a reduction in total time spent in work of about one month per year.

Third, the indicators on participation in farm-related labour and housework were in opposite directions among boys and girls. In the case of girls, school feeding led to a decrease in the time spent on farming and animal-rearing by nearly one month, while no significant changes in housework were evident. By contrast, among boys, the probability of participating in farm work increased across all food assistance types; for GFD, the increase was by about 13 percentage points. Also, boys receiving GFD showed a greater likelihood of working at home by 9 percentage points, leading to a rise of about one additional month spent in housework relative to comparison peers.

The estimates were disaggregated by exposure to conflict intensity to test whether the shifts in child work were larger in areas that were most affected by conflict events. The results reported in Supplementary Appendix H, Table SA.H.2, show that this seemed to be the case, especially for any work and farm activities. This is coherent with the hypothesis that child labour may increase especially where the conflict-related production shocks are larger.

Overall, these results corroborate the gendered division of work observed in the descriptive statistics (Supplementary Appendix H, Table SA.H.1) and related gender differences in the opportunity costs of schooling, which may also explain the differences in attendance between boys and girls. Among girls, school feeding led to a shift away from farm work because these activities may be less compatible with schooling. A similar finding was reported in rural Burkina Faso (Kazianga, de Walque, & Alderman, Citation2012). However, among boys, the receipt of any programme, but particularly GFD, led to increases in any type of work. One may speculate that the opportunity cost of schooling was higher among boys (for example, because of the greater involvement of boys in farm work and animal-rearing activities), particularly in areas characterised by higher conflict intensity, and thus the income effect stemming from the receipt of either food programme was not sufficient to shield boys from the increased demand for their labour following conflict-related shocks. The largest increases in the participation of boys in work were among children in the GFD group. This finding provides a plausible mechanism for the documented increases in school absenteeism among boys living in households receiving this type of food assistance.

8. Discussion and conclusions

The study examines the educational impacts of emergency school feeding and GFD in a context of conflict, protracted fragility, and substantial food insecurity. Children in households receiving school meals were 10 percentage points more likely to be enrolled in school, and they had completed on average nearly an additional half-year of education relative to children in the comparison group. Household receipt of GFD, by contrast, had no significant effects on enrolment and attainment and led to reductions in school attendance (about an additional half-day of absence per week). Important gender differences were also found. School feeding led to slightly larger gains in attainment among girls, while boys in households receiving GFD exhibited larger decreases in attendance by missing about an additional day of school per week relative to comparison boys.

These results can be explained by how these two social protection programmes were able to offset the opportunity costs of education relative to participation in child labour. These costs were already high in a setting characterised by structural food insecurity and were raised by the conflict. The treatment effects on child labour by assistance type mirrored the findings on education: school feeding among girls led to marked declines in participation and time spent in any work activity, especially farm labour. Decreases in farm labour among girls may be more compatible with school attendance, the key condition for receiving the free meals. GFD does not appear, however, to have offset the benefits of child labour among boys, for whom the opportunity cost of schooling is plausibly higher because of the greater involvement of boys in farm-related activities. Boys expanded their participation in any work, particularly in high-intensity conflict areas and among boys in GFD households. These results highlight that labour constraints are important in the choices between schooling and productive activities among various household members.

In a complementary analysis, the study finds that food assistance had important protective effects on household food security (Tranchant et al., Citation2018). Though both GFD and school feeding were beneficial, the size of the effects differed by type of food assistance, and GFD had larger effects on household food expenditures. The combined findings from both studies suggest there are important trade-offs to consider in providing food assistance during conflict, which may not only depend on the costs and feasibility of providing assistance in conflict-affected areas, as highlighted by Tranchant et al. (Citation2018), but also on the multidimensional risks that households and individual members face during conflict. Overall, these results highlight that the joint programming of school feeding and GFD activities (which is currently not generally undertaken by WFP) may help account for trade-offs and complementarities within and across programmes, leading to a more coherent approach to designing and delivering emergency food assistance. However, joint programming may also have implications in terms of lowering beneficiary coverage, which is another important trade-off in humanitarian response.

This study has limitations. First, there are no available data on child educational achievements. In the absence of complimentary supply-side interventions and given the low perceived quality of the Mali educational system (particularly during the crisis), the expectation that effects on learning outcomes would be observed is low. Yet, even if learning outcomes did not increase, incentivising school participation, attendance, and attainment can contribute to other important dimensions of child development in conflict, such as feelings of normalcy and safety, and may delay child marriage, especially among girls. This goal is particularly relevant in Mali, where recent estimates have documented that about one woman ages 18–22 in two had a child before age 18, and 13 per cent had a child before age 15 (Malé & Wodon, Citation2016). In contrast to other countries, the share of teenage childbirth has been increasing, with adverse life course consequences for girls and their children.

Attrition among households and villages is an additional concern. Specifically, at follow-up, four villages were lost to attrition because of the extreme levels of insecurity, and, for this reason, the sample is not representative of the broader population in Mopti, nor perhaps of groups that are most vulnerable to the detrimental effects of conflict (Tranchant et al., Citation2019). However, the inclusion of all baseline households in the estimation of the propensity score did not affect the results. Moreover, households that were lost to follow-up were less likely to be economically vulnerable than the households included in the longitudinal sample, a finding that is consistent with feedback from in-depth interviews during the formative stages of the study, whereby respondents highlighted that more well off households were the first to leave when conflicts began. Attrition rates were, however, similar among both treatment and comparison groups for all forms of aid. Attrition is, in this case, thus more likely to threaten external validity than internal validity.

There are no available cost data to assess cost-benefit and cost-effectiveness ratios. Also, given that both programmes affect multiple domains of child and household well-being, including education and food security, cost-benefit and cost-effectiveness exercises should address all these aspects in the calculation of benefits, which is beyond the scope of this report.

In a world in which humanitarian crises are more complex, recurrent, and protracted, the promise of social protection and quality education for all included in Sustainable Development Goals 1 and 4 cannot be realised without sound evidence on the impacts on children’s human development in fragility. This research highlights the potential of emergency school feeding to protect the education of vulnerable children, and it highlights the important trade-offs involved in the design of emergency food assistance. Important areas for further research remain. For instance, as with cash transfers, variation in the size and duration of food assistance may influence the related educational (cost)-effectiveness. Also, the extent to which complementary interventions, including supply-side educational investments, may enhance the effects of emergency food assistance is left for future research. The hope is that this study will spur further investigation to ensure the right to education to all children living in humanitarian contexts.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (676.3 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the government of Mali, the World Food Programme (WFP), and nongovernmental organisations and civil society stakeholders involved in the project activities held in Bamako and Mopti, including stakeholders at the central level and in Mopti, without whom this study would not have been possible. They would like to thank, at WFP, Iona Eberle, Marc Sauveur, Niamkeezoua Kodjo, Ibrahima Diop, Gerard Rubanda, Outman Badaoui, Kamayera Fainke, Moussa Jeantraore, Jean Damascene Hitayezu, William Nall, Silvia Caruso, and Sally Haydock. They also gratefully acknowledge Lesley Drake at the Partnership for Child Development for supporting the study and providing access to the baseline data and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation for financial support for the baseline data collection. They also thank the team at the Institut National de Recherche en Santé Publique (Mali) that was responsible for the qualitative research report, including Aly Landoure, Fadiala Sissoko, Yaya Bamba, Marcel Dao, Saye Renion, and S. Mamadou Traore. They are grateful to the Initiative pour le Développement Agricole et Rural and their team of enumerators for undertaking data collection in challenging areas. They also wish to thank the valuable feedback and support provided by the guest editors of the JDS special issue on Social Protection in Context of Fragility and Forced Displacement, Tilman Brück, Jose Cuesta, Jacobus de Hoop, Ugo Gentilini, and Amber Peterman, the editor of JDS, and two anonymous peer reviewers for their feedback. Also, they thank participants at the UNICEF workshop on Evidence on Social Protection in Contexts of Fragility and Forced Displacement and participants at the 2018 NEUDC conference at Cornell University for their valuable comments.

This work was undertaken as part of the CGIAR Research Programme on Policies, Institutions, and Markets (PIM) led by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI). Funding support for this study was provided by the International Initiative on Impact Evaluation (3ie) and the CGIAR Research Programme on Policies, Institutions, and Markets. Elisabetta Aurino gratefully acknowledges the financial support of the Imperial College Research Fellowship and the Guido Cazzavillan Research Fellowship. Last but not least, the authors thank children and households in Mopti, which, despite their daily challenges, took time to participate in this research. The hope is that this work can contribute to supporting their communities. Elisabetta Aurino conducted data analysis and led in writing the article. All authors contributed to the study design and draft.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Materials are available for this article which can be accessed via the online version of this journal available at https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2019.1687874

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. de Hoop and Rosati (Citation2014) note a similar possibility with cash transfers.

2. Although multiple sources, including WFP documents, discuss the detrimental impacts of the 2011/2012 agroclimatic crisis on livelihoods and on the sense of marginalisation felt in Mali’s central and northern regions, no detailed information on the drought could be found.

3. See Tranchant et al. (Citation2019) for additional details on the conflict.

4. In two villages, the village survey could not be completed at end line for logistical reasons. However, because the household data were collected, data from these villages were included in the final sample (N = 148, about 5 per cent of the sample).

5. Tranchant et al. (Citation2019) estimate the likelihood that armed groups were present in a given village at any point between 2012 and 2017 based on preconflict village characteristics. Their estimates show that the likelihood of armed groups presence tends to increase with (a) the share of members of the Peulh ethnic group in the village and (b) the value of agricultural production (measured by farm production and livestock holdings). The likelihood of the presence of armed groups decreases with (c) the mean level of economic welfare in the village (measured by dietary diversity). Together, these results suggest that the presence of armed groups is related to communal dynamics (especially, Peulh-Dogon relations), is fuelled by opportunistic motives (armed groups prioritised villages with higher farming and livestock output), and becomes less likely as economic development takes root.

6. Restricting the analytical sample to the longitudinal children sample does not qualitatively change the results.

References

- Abadie, A., Athey, S., Imbens, G. W., & Wooldridge, J. (2017). When should you adjust standard errors for clustering? ( NBER Working Paper No. 24003). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Adelman, S., Gilligan, D. O., & Lehrer, K. (2009). How effective are food-for-education programs? A critical reassessment. In J. von Braun, R. Vargas Hill, & R. Pandya-Lorch (Eds.), The poorest and hungry: Assessment, analyses, and actions (pp. 307–314). Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute.

- Akbulut-Yuksel, M. (2014). Children of war: The long-run effects of large-scale physical destruction and warfare on children. Journal of Human Resources, 49, 634–662.

- Akresh, R., Bhalotra, S., Leone, M., & Osili, U. O. (2017). First and second generation impacts of the Biafran war ( NBER Working Paper No. 23721). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Akresh, R., & de Walque, D. (2008). Armed conflict and schooling: Evidence from the 1994 Rwandan genocide ( Policy Research Working Paper No. 4606). Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Alderman, H., Gilligan, D. O., & Lehrer, K. (2012). The impact of food for education programs on school participation in northern Uganda. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 61, 187–218.

- Austin, P. C. (2009). Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples. Statistics in Medicine, 28, 3083–3107.

- Bahgat, K., Dupuy, K., Østby, G., Rustad, S. A., Strand, H., & Wig, T. (2017). Children and armed conflict: What existing data can tell us. Oslo: Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO).

- Barrett, C. B. (2006). Food aid’s intended and unintended consequences ( ESA Working Paper No. 06–05). Rome: Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations, Agricultural and Development Economics Division.

- Blattman, C., & Miguel, E. (2010). Civil war. Journal of Economic Literature, 48, 3–57.

- Broussard, N. H., Poppe, R., & Tekleselassie, T. G. (2016, July 31–August 2). The impact of emergency food aid on children’s schooling and work decisions. Paper presented at the 2016 Agricultural and Applied Economics Association’s Annual Meeting, Boston, MA.

- Buvinić, M., Das Gupta, M., & Shemyakina, O. N. (2014). Armed conflict, gender, and schooling. The World Bank Economic Review, 28, 311–319.

- Cameron, A. C., & Miller, D. L. (2015). A practitioner’s guide to cluster-robust inference. Journal of Human Resources, 50, 317–372.

- de Hoop, J., & Rosati, F. C. (2014). Cash transfers and child labor. The World Bank Research Observer, 29, 202–234.

- Dillon, A. (2013). Child labour and schooling responses to production and health shocks in northern Mali. Journal of African Economies, 22, 276–299.

- Doocy, S., & Tappis, H. (2016). Cash-based approaches in humanitarian emergencies: A systematic review ( 3ie Systematic Review No. 28). London: International Initiative for Impact Evaluation (3ie).

- Drake, L., Fernandes, M., Aurino, E., Kiamba, J., Giyose, B., Burbano, C., … Gelli, A. (2018). School feeding programs in middle childhood and adolescence. In D. A. P. Bundy, N. de Silva, S. Horton, D. T. Jamison, & G. C. Patton (Eds.), Disease control priorities (3rd ed.): Vol. 8. Optimizing education outcomes: High-return investments in school health for increased participation and learning (pp. 49–66). Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Edmonds, E. V. (2007). Child labor. In T. P. Schultz & J. A. Strauss (Eds.), Handbook of development economics (Vol. 4, pp. 3607–3709). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- Gelli, A., & Tranchant, J.-P. (2018). The impact of humanitarian food assistance on household food security during conflict in Mali. In F. S. Wouterse & A. S. Taffesse (Eds.), Boosting growth to end hunger by 2025: The role of social protection (pp. 71–92). Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute.

- Gilligan, D. O., Hoddinott, J. F., & Taffesse, A. S. (2009). The impact of Ethiopia’s productive safety net programme and its linkages. Journal of Development Studies, 45, 1684–1706.

- Harvey, P., Proudlock, K., Clay, E., Riley, B., & Jaspars, S. (2010). Food aid and food assistance in emergency and transitional contexts: Review of the current thinking ( HPG Synthesis Paper). London: Overseas Development Institute, Humanitarian Policy Group.

- Heckman, J. J., Ichimura, H., & Todd, P. (1998). Matching as an econometric evaluation estimator. Review of Economic Studies, 65, 261–294.

- Hirano, K., Imbens, G. W., & Ridder, G. (2003). Efficient estimation of average treatment effects using the estimated propensity score. Econometrica, 71, 1161–1189.

- Holmes, R. (2011). The role of social protection programmes in supporting education in conflict-affected situations. Prospects, 41, 223–236.

- International Crisis Group (ICG). (2016, July 6). Central Mali: An uprising in the making? ( Africa Report No. 238). Brussels: Author.

- International Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC). (2012). Mali: Northern takeover internally displaces at least 118,000 people. Geneva: Author.

- Justino, P. (2016). Supply and demand restrictions to education in conflict-affected countries: New research and future agendas. International Journal of Educational Development, 47, 76–85.

- Justino, P., Leone, M., & Salardi, P. (2014). Short- and long-term impact of violence on education: The case of Timor Leste. The World Bank Economic Review, 28, 320–353.

- Kazianga, H., de Walque, D., & Alderman, H. (2012). Educational and child labour impacts of two food-for-education schemes: Evidence from a randomised trial in rural Burkina Faso. Journal of African Economies, 21, 723–760.

- MacKinnon, J. G., & Webb, M. D. (2018). The wild bootstrap for few (treated) clusters. The Econometrics Journal, 21, 114–135.

- Malé, C., & Wodon, Q. (2016, March). Basic profile of child marriage in Mali ( Health, Nutrition, and Population Global Practice Knowledge Brief). Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Masset, E., & Gelli, A. (2013). Improving community development by linking agriculture, nutrition and education: Design of a randomised trial of ‘home-grown’ school feeding in Mali. Trials, 14(1), 55. Retrieved from https://trialsjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1745-6215-14-55

- Rosenbaum, P. R., & Rubin, D. B. (1983). The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika, 70, 41–55.

- Shemyakina, O. (2011). The effect of armed conflict on accumulation of schooling: Results from Tajikistan. Journal of Development Economics, 95, 186–200.

- Tranchant, J.-P., Gelli, A., Bliznashka, L., Diallo, A. S., Sacko, M., Assima, A., … Masset, E. (2018). The impact of food assistance on food insecure populations during conflict: Evidence from a quasi-experiment in Mali. World Development, 119, 185–202.

- Tranchant, J.-P., Gelli, A., & Masset, E. (2019). A micro-level perspective on the relationships between presence of armed groups, armed conflict violence, and access to aid in Mopti, Mali ( IFPRI Discussion Paper No. 1844). Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute.

- Ulrichs, M., & Sabates-Wheeler, R. (2018). Social protection and humanitarian response: What is the scope for integration? ( IDS Working Paper No. 516). Brighton, UK: Institute of Development Studies.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). (2017). Cash for education: A global review of UNHCR programs in refugee settings. New York, NY: Author.

- United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA). (2018). Humanitarian bulletin: Mali. New York, NY: Author.

- Villa, J. M. (2017). DIFF: Stata module to perform differences in differences estimation ( Statistical Software Components No. S457083). Chestnut Hill, MA: Boston College, Department of Economics.

- Wald, N., & Bozzoli, C. (2011). Bullet proof? Program evaluation in conflict areas: Evidence from rural Colombia. Proceedings of the German development economics conference, No. 80. Berlin: Verein für Socialpolitik, Research Committee Development Economics.

- World Development Indicators (WDI). (2017). [database]. Washington, DC: World Bank. Retrieved from http://databank.worldbank.org/data/reports.aspx?source=world-development-indicators

- World Food Programme (WFP). (2007). Full report of the thematic evaluation of the WFP school feeding in emergency situations ( Report from the Office of Evaluation No. OEDE/2007/06). Rome: Author.

- World Food Programme (WFP). (2013). State of school feeding worldwide 2013. Rome: Author.

- World Food Programme (WFP). (2015). Assistance to refugees and internally displaced persons affected by insecurity in Mali ( Standard Project Report 2015). Dakar, Senegal: Author.

- World Food Programme (WFP). (2017). World food assistance 2017. Taking stock and looking ahead. Rome: Author.