Abstract

This mixed methods study investigates the impact of introducing participatory intrahousehold decision making in Ugandan agricultural households on multiple dimensions of women’s empowerment, including more subjective aspects of sense of agency and achievements by examining how impact aligns with women’s perceptions of the process, meaning and value of their empowerment. Participatory intrahousehold decision making is expected to empower women through increasing their voice and decision-making power and reducing collective action problems within households, which compromise efficiency and equitable sharing of costs and benefits of household farming. Couple seminars raising awareness about participatory intrahousehold decision making promoted women’s involvement in strategic farm and household decisions, highly aspired and valued by women to actively contribute to their households’ welfare. This may facilitate the pathway to empowerment where women have some leeway to participate in strategic household affairs. Couple seminars made improvement in household welfare more likely. This is an achievement in itself with great meaning to women as it answers to their priorities and sense of agency. Introducing participatory intrahousehold decision making by an additional intensive coaching of couples contributed to women’s priority of enhanced access to household coffee income, only feasible in the pathway with room for participation in household affairs.

1. Introduction

Smallholder household farming continues to be a key economic activity for the majority of the rural population in East Africa. Yet, various challenges at different institutional levels form hindrances not only to efficient smallholder household farming, but also to gender equitable investments, of labour amongst others, and returns from household farming. Some of those challenges are situated at the household level and are linked to limited cooperation between spouses as the main decision makers and women’s limited bargaining power within the household (Doss, Citation2013; Doss & Meinzen-Dick, Citation2015; Doss & Quisumbing, Citation2020; McCarthy & Kilic, Citation2017; Munro, Citation2018).

This study contributes to understanding the potential of directly changing decision-making processes within the household to increase cooperation and empower women. It specifically assesses the impact of interventions with couples introducing a more participatory way of intrahousehold decision making, in which spouses consult each other and make decisions in correspondence with each other, on different dimensions of women’s empowerment in smallholder coffee farming households in central Uganda. With a mixed methods approach it additionally examines how impact aligns with women’s own priorities and strategies for their empowerment.

2. Literature

2.1. Agricultural households, intrahousehold bargaining and women’s empowerment

In a household farm system, because household members have different preferences and abilities to influence outcomes, there will be bargaining between them when they make interrelated decisions about investments in production and consumption of resources (Alderman, Hoddinott, Haddad, & Udry, Citation2003; Doss & Meinzen-Dick, Citation2015). The weight of household members’ decisions about production and consumption depends on their relative bargaining power, as does the distribution of costs and benefits (Agarwal, Citation1997; Doss, Citation2013).

There is substantial evidence that intrahousehold bargaining does not necessarily lead to cooperative and efficient solutions (e.g. Fiala & He, Citation2017; Iversen, Jackson, Kebede, Munro, & Verschoor, Citation2011; Munro, Citation2018) and that the distribution of benefits – in cooperative and non-cooperative solutions – is not necessarily equitable across household members (e.g. Doss, Citation2013; Duflo & Udry, Citation2004).

Doss and Meinzen-Dick (Citation2015) draw parallels between household farm systems and common pool resources (CPR) from which exclusion is difficult and consumption of resource units rival (Ostrom, Citation1990). In recognition of the presence of collective action problems and power imbalances between members in agricultural households, and in parallel with solutions to collective action dilemmas in CPR settings, they point out that it is worth investigating whether more participatory intrahousehold decision making could contribute to cooperation and more balanced bargaining power.

This study focuses on the contribution of a more participatory mode of intrahousehold decision making for cooperation and women’s bargaining power and what this means for women’s empowerment in agricultural households. Empowerment is defined as a process of change where people acquire the ability to make strategic life choices and transform those choices into desired action and outcomes to lead the life one has reason to value (Alsop, Bertelsen, & Holland, Citation2006; Kabeer, Citation1999). Empowerment needs to carry the potential to challenge existing power relations (Cornwall, Citation2016). It may require an inner transformation from unquestioned acceptance of inequality or injustice to critical consciousness where women can at least imagine the possibility of choosing differently (Cornwall, Citation2016; Kabeer, Citation1999; Malhotra, Schuler, & Boender, Citation2002). The concept of empowerment is inherently subjective which makes the psychological dimension of empowerment – women’s sense of agency or the meaning, motivation and purpose they bring to their actions and decisions (‘power within’) – of fundamental importance (Kabeer, Citation1999; Klein & Ballon, Citation2018). The concept of empowerment can be broken down in terms of three inter-related dimensions of resources (pre-conditions), agency (the process of decision making, often considered the essence of empowerment) and achievements () (Kabeer, Citation1999; Malhotra et al., Citation2002). Achievements as outcomes of the ability to make choices that are meaningful to women, by definition, have a subjective component as well.

2.2. Research objectives and hypotheses

The objective of this study is to assess the impact of introducing participatory intrahousehold decision making through interventions with spouses, as the main decision makers in households, on different dimensions of women’s empowerment, including more subjective dimensions of sense of agency and achievements.Footnote1

A first mechanism by which participatory intrahousehold decision making is hypothesised to contribute to women’s empowerment is by reducing information asymmetry and strengthening mutual commitment between spouses (Ostrom, Citation1990) (). Since they will be better informed about household’s investment and expenditure needs and about each other’s contributions to production and consumption, spouses will be less likely to act opportunistically – by shirking on joint effort or excessively using its returns. This is expected to benefit cooperation and a more equitable sharing of costs and benefits of household farming.

Figure 2. Hypothesised pathways of change by which participatory intrahousehold decision making affects different dimensions of women’s empowerment

Evidence about the relation between information asymmetry, cooperation, efficiency and resource allocation in households in developing contexts includes Ashraf (Citation2009), who showed that one fifth of participants in a lab-in-the-field experiment were willing to give up money to keep returns hidden from their spouse, thereby creating household efficiency losses. In some cases, productive labour efforts, that are not easily observable and subject to information asymmetry, are provided at suboptimal levels and lead to efficiency losses in agricultural households (Baland & Ziparo, Citation2018). In Ghanaian households, public transfers increased expenditures on household goods, while private transfers were mainly used for private or concealable expenditures (Castilla & Walker, Citation2013). Ambler, Doss, Kieran, and Passarelli (Citation2019) found that women’s involvement in asset ownership and decision making which is agreed upon by spouses and which indicates limited information asymmetry is associated with positive outcomes for women, more so than women’s involvement which is disagreed upon by spouses and which indicates information asymmetry.

A second mechanism relies on the hypothesis that participatory decision making will strengthen the voice and influence of women in intrahousehold decision making, which are normally limited in patriarchal societies (). If women gain intrahousehold rule- and decision-making power, inequitable outcomes are expected less likely because women will be better able to claim a share of common household resources and benefits and negotiate a more equal sharing of the burden of investing in farm and household (Agarwal, Citation1997, Citation2001; Doss & Meinzen-Dick, Citation2015). Moreover, compliance with sharing rules is more likely if mutually agreed upon. Women’s strengthened voice and influence is expected to contribute to women’s sense of agency as well as achievements in the form of changes that are meaningful to women.

In support of the relation between women’s voice and more gender equitable outcomes, in matrilineal communities, where women’s bargaining power is relatively strong, female land managers are found less vulnerable to shocks and spouses more likely to pool risks (Asfaw & Maggio, Citation2017). There is, however, limited evidence of a correlation between women’s agency and lower levels of women’s time poverty (Arora, Citation2015; Bain, Ransom, & Halimatusa’diyah, Citation2018). Increased women’s agency is generally positively associated with women’s physical and psychological wellbeing (Fielding & Lepine, Citation2017). Qualitative studies looking into women’s empowerment ‘as a lived experience’ report an enhanced sense of self-worth, a new identity as valued contributor to the household, renewed respect in the eyes of their husbands, and more acceptance and inclusion within the community (Hunt & Kasynathan, Citation2001; Kabeer, Citation2001).

Additionally, we expect greater household welfare will follow from improved intrahousehold cooperation and reduced opportunism introduced by participatory decision making. In support, Lecoutere and Jassogne (Citation2019) found that cooperative and equal sharing behaviour by couples in a lab-in-the-field experiment is associated with greater actual investments in agricultural production and household wellbeing. Intrahousehold cooperation was found to positively affect expenditures on household public goods, including education and food, and households’ economic wellbeing (Duflo & Udry, Citation2004; McCarthy & Kilic, Citation2017).

Greater household welfare may also follow from women’s strengthened voice and agency. Women’s empowerment in the household has been found positively correlated with agricultural productivity of households (Seymour, Citation2017), household budget shares spent on food, children’s education and health, and (durable) household goods (De Brauw, Gilligan, Hoddinott, & Roy, Citation2014; Duflo & Udry, Citation2004; Quisumbing & Maluccio, Citation2003; Yoong, Rabinovich, & Diepeveen, Citation2012), household and child nutrition (Heckert, Olney, & Ruel, Citation2019; Sraboni, Malapit, Quisumbing, & Ahmed, Citation2014), including in Ugandan coffee farming households (Chiputwa & Qaim, Citation2016).

In line with hypothesised pathways of change visualised in , we will specifically test if information asymmetry, as a direct or negotiated consequence of participatory intrahousehold decision making, diminished. We will examine the extent to which expected positive effects on women’s access to resources, equality of spouses’ investments in household commons, women’s agency and household welfare materialised. We will additionally evaluate how impacts contributed to the more subjective sense of agency and achievements by examining how they fit into women’s own valued priorities and strategies for their empowerment; even if it remains tricky to differentiate the extent to which women’s preferences are intrinsic or external expectations that have been internalised (Doss, Citation2013; Kabeer, Citation1999).

Section 3 of the article presents interventions through which participatory intrahousehold decision making was introduced, Section 4 the mixed method approach to evaluating their impact on women’s empowerment, Section 5 results and Section 6 the conclusion.

3. Intervention

This study concentrates on smallholder coffee farming households living in Masaka and Kalungu districts and Mubende district in central Uganda who are member of producer organisations (POs) connected to the Hanns R. Neumann Stiftung (HRNS), a German non-profit foundation. Typically, the household farm system consists of productive resources such as land, labour, financial and other assets, from which agricultural produce and income are derived. Agricultural production on the household farm generally includes food crops for household consumption, of which excess harvests are sold, as well as some cash crops – mostly coffee in this case – for marketing.

In selected regions, in addition to standard agronomic and marketing trainings, HRNS implemented a Gender Household Approach (GHA), which fits into methodologies that address gender relations within households (Farnworth, Fones-Sundell, Nzioki, Shivutse, & Davis, Citation2013). The GHA promotes farm and coffee production as a family business where all members contribute and benefit equally.

In an initial stage of the GHA, half-day couple seminars were organised for PO members. The HRNS gender officers, with a background in family counselling and trained in addressing gender issues, guided a group of couples through a self-assessment of the division of roles, responsibilities, decision-making power and access to resources in their households. Participatory gender analysis tools, such as activity profiles and access/control over resources matrices were the key tools. Increased awareness of imbalances and insights that more consultation and collaboration and a fairer division of inputs and benefits could be beneficial for all is to motivate couples to change towards a more participatory way of running their household and farm.

In a next stage of the GHA, a selection of couples who participated in couple seminars went through a package of activities during which couples were intensively coached. A first activity was a one-day workshop during which the HRNS gender officer coached the couples how to make their intrahousehold planning and decision-making more participatory, set a common goal and share household resources and responsibilities in a more (gender) equitable way. A household farm plan and budget where each couple listed their anticipated income, necessary expenditures for both their farm and household and planned incremental investments to reach their common goals was an essential tool for goal setting, communication and follow-up. In total 20 of such workshops were conducted over the course of two months in Masaka-Kalungu, 32 in Mubende, for groups of seven couples on average. Subsequently, couples received a private household visit during which the HRNS gender officer continued coaching and provided support with implementation of the farm plan and budget. Thirdly, women attended a women leadership training, organised for small groups of women, to strengthen their participation and leadership skills in farmer groups and their household. In a final workshop, organised in small groups, couples shared experiences and self-evaluated the coaching package.

4. Methods

4.1. A mixed methods approach

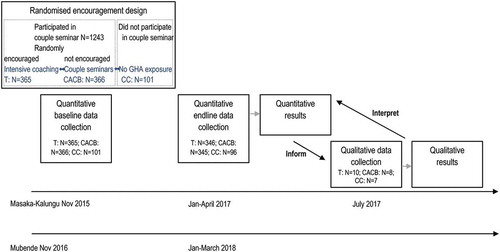

We adopted a mixed methods research strategy following the logic of a sequential explanatory design, starting with quantitative data collection, followed by qualitative inquiry, which combined into a mixed method assessment of impact (Ivankova, Creswell, & Stick, Citation2006) ().

A mixed method approach does not only add depth. It is also appropriate for analysing impact on women’s empowerment as it enables to additionally assess impact on more subjective dimensions of women’s sense of agency and achievement. To do so, we examined women’s perceptions and lived experiences to understand the meaning and value that women assign to different dimensions of empowerment in their household (Section 5.2.), the way they perceive their process towards empowerment (Section 5.3.), and the extent to which quantitatively observed impacts (Section 5.4.) aligns with their valued priorities and strategies for empowerment (Section 5.5.).

4.2. Quantitative data and method of analysis

4.2.1. Identification strategy

To evaluate the differential impact of the two stages of HRNS’ GHA – couple seminars and the subsequent intensive coaching package – through which participatory intrahousehold decision making was introduced in smallholder coffee farming households, a randomised encouragement design was set up in each study area, Masaka-Kalungu districts and Mubende district.

Out of 1243 couples who participated in couple seminars, per study area, we randomly assigned couples to be encouraged to take up the intensive coaching package and couples to not be encouraged.Footnote2 We labelled the couples randomly assigned to be encouraged the intensively coached group (T), which includes 346 couples.Footnote3 We labelled the couples randomly assigned to not be encouraged the control group of couples who only received a couple seminar (CACB). This group includes 345 couples.Footnote4 Ten couples of the intensively coached group did not comply with their encouragement status and did not attend intensive coaching. 13 couples of the control group who only received a couple seminar did not comply and followed intensive coaching. Per study area sub-sample, random encouragement achieved balance across the intensively coached group and control group who only received a couple seminar on most baseline characteristics (Tables A and B Online Supplementary Materials (OSM) A).

The encouragement consisted of a personal invitation for the first activity by phone and via a letter, which was accompanied by a folder, notebook and pens in Mubende. Couples also got a second chance to participate if they missed an activity.

A control group without GHA exposure (CC) is composed of 96 couples randomly selected among PO member coffee farming households across, respectively, Masaka-Kalungu and Mubende districts where HRNS did not implement its GHA.Footnote5 These couples did not self-select into a couple seminar, which we will control for (Inf.). Otherwise we can assume that circumstances in which they live and farm are not fundamentally different and they live far enough to avoid spillovers from any GHA activity (See map Figure A OSM A). Assessment of balance per sub-sample shows that the group who only received couple seminar and the control group without GHA exposure are imbalanced on some baseline characteristics (Tables C and D OSM A).

The impact of the intensive coaching programme versus only having attended a couple seminar was estimated by comparing outcomes in the intensively coached group and the group of couples who only received a couple seminar (T vs CACB).Footnote6 We used the randomised encouragement status as an exogenous instrumental variable (IV) for endogenous treatment status.Footnote7 Estimated local average treatment effects are externally valid for compliers.

As an identification strategy, apart from randomised encouragement, we used propensity score matching (PSM) based on baseline characteristics with inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW), separately for Masaka-Kalungu and Mubende sub-samples, to control for any remaining (observable) imbalance.Footnote8 Per sub-sample, with PSM, we controlled for initial conducive elements for women’s empowerment identified through qualitative interviews (listed in Section 5.3.), and, additionally, household food security, exogenous household wealth (land size), and husband’s off-farm income (potentially lowering his stake in cash crops leaving more room for wife’s involvement (Agarwal, Citation2001)).Footnote9 Assessment of balance after PSM is included in Tables A and B OSM A. We controlled for area (sub-sample) fixed effects by inclusion of a dummy for Mubende as a co-variate.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of outcome indicators by group (disregarding non-compliance and before matching)

Table 2. List of conducive elements for women’s empowerment as perceived by women

Comparing outcomes in the group of couples who only received couple seminars with the group without GHA exposure tells us the impact of the couple seminars (CACB vs CC). We used simple regression analysis of the effect of couple seminars combined with PSM and an area dummy using the same procedure as described above.Footnote10 Tables C and D OSM A present assessment of balance after PSM. PSM serves as an identification strategy to deal with imbalance and potential selection bias linked to the fact that couples in the group with couple seminars self-selected into couple seminars while couples in the group without GHA exposure did not. PSM relies on the assumption that unobservable differences are absorbed by controlling for observable factors and therefore do not bias results. We acknowledge this may be a strong assumption which cannot be verified. By controlling for initial women’s empowerment with PSM, in the same way as described above, we reduced the chance that unobservable differences linked to potential for and openness towards women’s empowerment remain reasons for bias.

There was attrition between base- and endline of 45 couples.Footnote11 Attrition rates per group are 5.2 per cent of T, 5. 7 per cent of CACB, and 5.0 per cent of CC. Attrition was by force majeure in number of cases.Footnote12 The assessment of balance on baseline characteristics (Tables F-I OSM C) hints that attrited couples in the Mubende sub-sample may be relatively poor. There are indicative differences in husband’s age and off-farm income and women’s microfinance group membership in the Masaka-Kalungu sub-sample. If these would imply that couples who are less receptive of participatory intrahousehold decision making and women’s empowerment selectively shied away, this could be a reason for upward attrition bias.

4.2.2. Data and indicator definition

In Masaka-Kalungu districts, the field experiment started in November 2015. Endline data was collected January-April 2017. In Mubende district, the field experiment started in November 2016, endline data was collected January-March 2018 (). Base- and endline interviews were done in approximately the same order with on average one year between interviews. Individual surveys were conducted separately with each of the spouses of selected couples.

Questions relevant for measuring women’s empowerment in the quantitative surveys were inspired by questions used for the Women Empowerment in Agriculture Index (Alkire et al., Citation2013). All questions referred as much as possible to specific situations to introduce face-validity and minimise socially desirability bias as compared to more open questions on feelings of power and ability (Hanmer & Klugman, Citation2016).

Along the lines of Johnson, Kovarik, Meinzen-Dick, Njuki, and Quisumbing (Citation2016) and Malapit et al. (Citation2019), women’s empowerment is taken to encompass both enhanced individual and joint decision making and resource access. We consider this most appropriate for assessment of methodologies that address gender relations within households and in line with women’s own perspectives on empowerment (Inf.).

As indicators for women’s access to resources we used proportion of household tropical livestock units (TLU) of which the wife has sole or shared ownership, the proportion of coffee income in which the wife was involved (alone or jointly) in sales transactions, including receiving money, the likelihood of the wife having personal income (See Appendix A for exact indicator definition; for descriptive statistics). We used an indicator of transparency between spouses over coffee income as a measure of information asymmetry. We used the relative time allocation of wife and husband to tasks in the reproductive and domestic versus productive sphere as an indicator of equality of investment in household commons. We operationalised agency as women’s effective involvement (alone or jointly) in strategic decisions about the household farm, which include decisions about major expenditures, investments, adoption of agronomic practices for coffee and expenditures for agricultural inputs and labour, and in strategic household decisions, which include decisions about expenditures for school fees, medical interventions, sending remittances and social events. We used perceived improvement in household wellbeing and/or food security over time as an indicator of household welfare. Measurement of impact on women’s sense of agency and achievements, as meaningful change, relies on combining quantitative and qualitative insights (Section 4.3.).

Where possible, we also defined indicators based on agreement by spouses or on averages of their reported amounts. This is to account for gender differences in perception and reporting of decision making in individual surveys and for the greater likelihood of women labelling a decision as joint where men labels it as their individual decision (Acosta et al., Citation2020; Ambler et al., Citation2019). We performed impact estimations on these indicators as a robustness check.

As we test impact on families of outcomes, we adjusted p-values for multiple hypotheses testing applying the method by Sankoh, Huque, and Dubey (Citation1997).Footnote13

4.3. Qualitative data and method of analysis

In line with our sequential explanatory design, in June-July 2017, we conducted individual in-depth qualitative interviews with 25 women from Masaka-Kalungu districts (). The sequential explanatory design enabled informed purposive selection of respondents from the quantitative study population. We selected respondents with a highly negative and highly positive aggregate empowerment score, calculated based on quantitative baseline data, across treatment and control groups.Footnote14 While the qualitative sample is small and not representative of the study population, at the end of inquiry, we felt close to having reached saturation. Interviews were conducted in Luganda, the local language, by the research assistant and translated on the spot to enable conversation between researcher and respondent.

One of our strategies to enhance credibility (internal validity) was to ground qualitative data collection and analysis in theory about women’s empowerment. Designed to capture subjective dimensions of empowerment and add depth to quantitative insights, the semi-structured interview guide combined simple scoring exercises with open-ended questions. As such, we elicited women’s reflections about changes over time, their ideal situation and other women’s situation in terms of decision-making power over daily needs, food and cash crops, major household expenditures, financial transparency and access to resources and land, and their importance for living the life they value.Footnote15 Decision-making power was captured by referring to having significant weight in final decisions. To ensure richness in women’s accounts, we asked for women’s perceived reasons and feelings about differences over time, with other women and with their ideal situation.

We analysed interview notes in different ways, consistent with theory about women’s empowerment and our sequential explanatory design. We examined accounts of their current situation by women with a low (baseline) empowerment score to determine prevailing ‘normal’ status, norms and customs defining women’s empowerment in the household. We brought in reflections by women with high empowerment score about their past situation and that of other women (informative) (Section 5.1.). We examined what women value in an empowering process to understand women’s sense of agency (reflective) (Section 5.2.). We screened all women’s entire stories of lived experiences with regard to decision-making power and access to resources and looked for patterns of specific pathways of empowerment, and categorised constraints and drivers for empowerment recurrently mentioned (informative) (Section 5.3.). We reflected on quantitative impact results while incorporating women’s perspectives on meaning and value of particular dimensions and pathways of empowerment (reflective) (Section 5.5.). This enabled an understanding of impact on subjective aspects of empowerment including women’s sense of agency and achievements.

We assume qualitative insights from Masaka-Kalungu districts are relevant for Mubende district since farm organisation, household composition, cultural traditions of the Baganda in Uganda’s Central Region and formal and informal institutions relevant for smallholder farming households and gender relations are largely similar (Howard & Nabanoga, Citation2007).

We minimised risks of confirmation bias by having the researcher, who did not run the field experiment and quantitative data collection, conduct qualitative data collection prior to her involvement in quantitative impact assessment. By explicitly stating our researcher team’s independence of HRNS, we minimised risks of social desirability bias whereby respondents try to conform to HRNS’ expectations.

As female researchers in development studies from a Western country, our background and lived experienced could have coloured research design, interviews and qualitative data analysis. The fact that the study was embedded in ongoing interventions of an organisation with long-term local presence, was triangulated with Ugandan programme staff, and included Ugandan research assistants reduced chances that our preconceived ideas remained unquestioned. It also provided the chance for seeking assistance in contextualising apparent anomalies. The input and feedback by Fortunate Paska, Emma Doreen Arinaitwe, and Sarah Nabulobi from HRNS andresearch assistant Betty Nnajjuma were particularly valuable. A final way to reduce subjectivity and enhance credibility was doing a first analysis of qualitative data separately after which we combined our insights.

5. Results

5.1. Context

To expand on context, we relied on qualitative data to uncover the prevailing ‘normal’ status of women’s empowerment and norms and customs that define intrahousehold access to resources and decision making. We related these to the literature discussing prevailing women’s land rights, bride price and gender norms in coffee farming in Uganda and included relevant baseline quantitative data.

Paying a bride price, as a non-refundable gift, is common in the study area (Nannyonga-Tamusuza, Citation2009), and tends to have negative implications for women’s bargaining power in the household. In Uganda, up to 80 per cent of land is administered according to local custom (Kabahinda, Citation2018). While statutory systems protect women’s rights to own, use or transfer land, weak institutional capacity, lack of knowledge of the laws, and the high costs of legal action mostly allow customary laws and practices, particularly in rural areas (Hannay, Citation2014; Jacobs & Kes, Citation2015). Women in our study context explain: ‘as a woman, you come and get married when your husband already owns land’ (CC_disemp_3, 29 June 2017). ‘My husband owns the land. I have limited power over how to use it’ (CA_disemp_1, 7 July 2017). These women’s accounts resonate with other studies pointing out that only 10–16 per cent of women legally own land in their own name (Rugadya, Citation2010), that women’s claims to land are made primarily through their husbands or male kin (Kabahinda, Citation2018) and that (joint) ownership does not necessarily translate into recognised use and decision-making rights on this land (Doss, Meinzen-Dick, & Bomuhangi, Citation2014; Jacobs & Kes, Citation2015; Kabahinda, Citation2018). As Jacobs and Kes (Citation2015) observed, legal marriage and children enhance women’s decision-making power over land transactions and use: ‘I have [some] power. I am [legally] married and have children’ (T_disemp_1, 9 July 2017). ‘I can oppose his decision [to sell land] because I have children’ (CA_disemp_1, 7 July 2017). Still, women’s claims to land are insecure: ‘I also signed when we bought [the land], but now he has sold everything, so those signatures didn’t count’ (T_emp_1, 3 July 2017).

Livestock is considered ‘personal ownership [of the one] who bought it. [Yet] if my husband would initiate a decision to sell [livestock] for a good reason, I would not complain’ (T_disemp_2, 4 July 2017). At baseline, women owned on average 0.41 TLU in Masaka-Kalungu, 0.19 TLU in Mubende. Women were involved in ownership of 38 per cent of household TLU in Masaka-Kalungu, of 45 per cent of household TLU in Mubende.

Coffee plantations are mostly controlled by the husband, which Kasente (Citation2012) relates to male-dominated land ownership and the perennial nature of coffee requiring secure land rights. ‘My husband owns the plantation […] I need to first request permission to harvest. He also has power over management decisions’ (T_disemp_3, 6 July 2017). Yet, some women in our study population personally own a coffee plantation. Food crops can be a shared or woman’s responsibility, but this tends to vary across contexts (Peterman, Quisumbing, Behrman, & Nkonya, Citation2011). In our study areas, at baseline, 26 per cent of women in Masaka-Kalungu and four per cent in Mubende reported to be involved in management of the main cash crop. 13 per cent of women in Masaka-Kalungu and three per cent in Mubende reported to be involved in the management of the main staple food crop.

Typically, ‘the husband [sells] the coffee’ (T_emp_2, 4 July 2017), which is confirmed by Bolwig (Citation2012), Kasente (Citation2012) and Chiputwa and Qaim (Citation2016). Or ‘it is sold under the husband’s name, but income is for the household’ (CC_disemp_1, 29 June 2017). Some women are informed about the coffee income, others not: ‘he doesn’t bring the money home […] I try to make inquiries, but he stays quiet’ (CA_emp_1, 7 July 2017). In some cases, the way coffee income is spent – often on school fees – is a joint decision. In other cases: ‘The husband has final decision power. Sometimes we have agreed, but my husband spends the money another way’ (T_emp_2, 4 July 2017). ‘[There is] no accountability about money’ (CA_emp_2, 3 July 2017).

Men typically have greater decision-making power than women over strategic household decisions and the use of income (Lecoutere & Jassogne, Citation2019; Sell & Minot, Citation2018). Some women see decisions about strategic household affairs and investments as the responsibility of the household head. ‘I cannot contribute; thus, I have little [decision-making] power’ (CA_emp_3, 8 July 2017). But situations differ: ‘We discuss when my husband seeks advice’ (CA_disemp_2, 9 July 2017), ‘my husband cannot buy anything without having told me’ (CC_disemp_3, 29 June 2017), or ‘what I plan is taken into consideration, I have considerable power about household investments’ (CC_disemp_1, 29 June 2017). For daily needs, most women ‘identify what is needed and the husband buys’ (CA_emp_4, 3 July 2017).

Women are heavily involved in domestic and agricultural work, which is widely confirmed (a.o. Bolwig, Citation2012; Kabahinda, Citation2018; Kasente, Citation2012). At baseline, in Mubende,Footnote16 on average, women spent almost three and a half hours on activities in the reproductive and domestic sphere, men less than 15 minutes. Women spent approximately four and a half hours on productive activities and men six and a half hours. Coffee production demands substantial women’s farm labour time, on top of women’s labour time spent on food production (Bolwig, Citation2012). Labour in coffee production is divided according to traditional gender roles, largely excluding women from marketing and sales (Bolwig, Citation2012; Kasente, Citation2012). But, women express ‘[they] would wish equal time [spent by husband and wife on food and cash crop production] … men over-concentrate on income-generating activities’ (CC_disemp_1, 29 June 2017).

5.2. What meaning and value do women assign to different dimensions of empowerment in their household?

First, women assign high value to having a significant weight in final decisions on all issues of strategic importance for farm and household to contribute to their households’ wellbeing from which they derive appreciation and a sense of self-worth (): ‘A woman is always looked at as the mirror of the household’ (CA_emp_2, 3 July 2017).

Figure 4. Overview of the importance women assign to their weight in final decisions about daily needs, food and cash crops, major household expenditures, land and groups for leading the life they have reason to value

Secondly, in women’s ideal situation in terms of empowerment in their households, they can exercise significant control over land. Some feel they earned a right: ‘when you get married, you work together and [acquire land]. I feel the land also belongs to [the wife]’ (CA_emp_5, 4 July 2017). Others desire to avert the insecurity of their claims to land.

Joint control over the household’s coffee plantation is ideal in some women’s perspective. Transparency about the returns is equally important: ‘I would love joint decision making, especially accountability on output’ (CA_emp_3, 8 July 2017). Other women find a personal coffee plantation ideal ‘to have personal income […] but also to reinvest in the household’ (CA_emp_4, 3 July 2017).

All women deem a significant degree of control over food crop production essential. ‘I do the planning, I think for the family […] I decide how to use the yield [of food crops]: how much to sell, how much we need for consumption’ (CA_disemp_1, 7 July 2017). Some claim: ‘Husbands don’t care about food security, so it’s very important for women to have a final say’ (CC_emp_2, 5 July 2017). But, ‘Now all my attention and effort go in [food production]. It should be a shared responsibility’ (CA_emp_2, 3 July 2017).

Most women pursue equal or coordinated decision making about strategic household and farm affairs. ‘As a woman I carry the burden of the wellbeing of the household, so I really want to stay in a position of [decision-making] power’ (CC_disemp_1, 29 June 2017). But many ‘do not see it happening’ (CA_emp_3, 30 June 2017), or ‘do not hope for change’ (T_emp_6, 6 July 2017).

5.3. How do women perceive their process towards empowerment in their household?

Qualitative analysis of women’s lived experiences shows there is great diversity in relationships between husbands and wives and in women’s self-perceived empowerment. Women’s involvement in decision making depends on how strongly patriarchal norms and customs are playing in their households. We call this a ‘wall of patriarchy’, a barrier to women’s decision-making power within the household and to their empowerment. The strength of this ‘wall of patriarchy’ appears to be largely beyond women’s control and depends mostly on the husband’s goodwill. ‘If a woman’s decision-making power is restricted by the morals of the man, then yes, that’s difficult to change […] Some women are better off because they cooperate more with their husbands. In these women’s cases, their husbands are flexible, dynamic, open to working together with their wives’ (CC_emp_5, 5 July 2017). ‘It came as a surprise that I acquired the power to make decisions over [strategic household] needs. My husband just changed’ (CC_disemp_2, 30 June 2017).

While screening women’s stories for patterns, we distinguished three ways in which women deal with this ‘wall of patriarchy’ ( visualises the first two). These are three broadly defined pathways towards empowerment, where women’s involvement in decision making is distinct and personal resources have a specific role. We labelled the first pathway ‘Breaking through the wall of patriarchy’, depicted by about half of interviewed women. This pathway is conditional on being ‘lucky’ to have married a ‘flexible’ husband who does not abide strongly by prevailing patriarchal modes of organising the household and farm described in Section 5.1. and is willing to be cooperative. ‘Some women […] are given freedom of expression, to initiate decisions and to be actively involved in family affairs, including coffee sales […] Their husband gave them a chance’ (T_emp_4, 7 July 2017).

Figure 5. Pathways of women’s empowerment

Most women on this pathway reported a source of personal income – through small livestock, trade, selling crafts or food, paid labour or a personal coffee plantation. This is important to provide in household and personal needs, but primarily to increase their bargaining power: ‘I invested part of my personal money in the tomatoes. I therefore had more input into decisions and my husband respected my input more’ (CA_emp_2, 3 July 2017). One possible situation is cooperation and shared decision making. ‘We are making decisions jointly. We work together in the household gardens’ (CC_emp_1, 7 July 2017). Transparency and accountability about household resources are crucially important in that case: ‘It’s all about knowing the resources, otherwise you cannot initiate decisions’ (T_emp_4, 7 July 2017). ‘You cannot have decision-making power if you don’t know the income’ (CC_emp_2, 5 July 2017). Transparency can be bargained for: ‘When the need for an investment arises […] I contribute […] My husband tells me how much he got [by selling coffee]’ (CA_disemp_1, 7 July 2017). Another situation consists of limited transparency but a husband who prioritises the household’s wellbeing. ‘My husband [keeps the money.] He doesn’t always tell me […] He takes his responsibility, every harvest he gives me enough money for household and some personal needs […] I feel happy about this’ (CA_emp_4, 3 July 2017).

We labelled a second pathway, experienced by somewhat less than half of women, ‘Circumventing the wall of patriarchy’. If women cannot, do not want or no longer dare to rely on cooperation or goodwill by their husbands, their pathway towards empowerment comes down to strengthening their independence within the household by taking control over resources. ‘My husband is hard, unpredictable, I don’t know how I can change his mind to see the need for joint decision making’ (T_emp_2, 4 July 2017). Having personal assets or income is deemed extremely important to contribute or manage the household by themselves if needed, not so much for gaining bargaining power. ‘I do tailoring and can use some of the income [for daily needs]’ (T_emp_2, 4 July 2017). In this pathway, women mostly have full control over food crops and their husbands over cash crops. But none of the women signalled to be comfortable with relying on their husband specialising in income generation while their control remains limited to food production. ‘I initiate and implement all decisions about food crops […] My husband takes care of the coffee […] I am not satisfied with the situation […] He doesn’t fulfil his responsibilities as a husband. Some [household needs] don’t cross my husband’s mind. I buy them myself’ (CC_emp_5, 5 July 2017).

Three women are on a third pathway and have ‘No choice but to take full responsibility’ over food as well as cash crop production and other farm and household affairs because their husband is a migrant worker or is ill. These women perceive this responsibility as a heavy burden that they would have preferred to share with their husband.

Next, we identified constraints and drivers for empowerment recurrently mentioned by women in (Analysis in Appendix B). Constraints and drivers that could be quantitatively operationalised are used to control for initial levels of women’s empowerment with PSM in the quantitative impact evaluation (See Section 4.2.1.).

5.4. What is the impact of introducing participatory intrahousehold decision making on different dimensions of women’s empowerment?

In this section, we quantitatively assessed impact of the GHA interventions with couples introducing participatory intrahousehold decision making on different dimensions of women’s empowerment.

5.4.1. Resources, transparency over income, time allocation

The intensive coaching versus only couple seminars increased the proportion of household coffee income in which women were involved in sales transactions by 0.104 ( Panel A (4)). This comes down to a 37 per cent increase compared to the control group with only couple seminars ( (4)). Intensive coaching did not affect women’s access to livestock, personal income, transparency, nor spouses’ relative time allocation to reproductive and domestic tasks (Panel A (1–3)(6–7)).

Table 3. Estimates of average treatment effects (βx) on women’s access to assets and income and on time allocation

Couple seminars versus no GHA exposure did not have any impact on women’s access to coffee income, livestock, personal income, transparency nor time allocation ( Panel B (1–7)).

5.4.2. Agency: women’s involvement in strategic decision making

Couple seminars increased the proportion of strategic farm decisions in which women are involved by 0.141 ( Panel B (1), which is a 45 per cent increase of the proportion in the control group without GHA exposure ( (8)). The proportion of strategic household decisions in which women are involved increased by 0.151 (Panel B (3)), which comes down to a 29 per cent increase ( (10)). These positive effects are confirmed for indicators based on husbands’ and wives’ agreement about women’s involvement in strategic farm and household decisions (Panel B (2) (4)).

Table 4. Estimates of average treatment effects (βx) on women’s involvement in strategic farm and household decisions and on improved household welfare

Intensive coaching did not cause any additional change in women’s involvement in strategic decision making about farm and household versus couple seminars ( Panel A (1–6)).

5.4.3. Household welfare

Couple seminars increased the likelihood of improved household’s wellbeing and/or food security by 0.098 ( Panel B (5)). The likelihood more than doubled vis-a-vis the control group without GHA exposure, where it is 0.065 ( (12)). This positive effect is confirmed in the robustness test (Panel B (6)).

Intensive coaching versus couple seminars did not have additional impact ( Panel A (5)).Footnote20

5.5. How does the impact of introducing of participatory intrahousehold decision making fit into women’s own strategies for empowerment?

In this section, we examined the extent to which the effects of introducing participatory intrahousehold decision making through intensive couple coaching and couple seminars, detected in Section 5.4., answered to women’s priorities in terms of their empowerment and fit into women’s own strategies for empowerment, discussed in Sections 5.2. and 5.3. (Visualised in ). As such, we additionally capture impact on more subjective aspects of women’s sense of agency and achievements.

Figure 6. How the impact of introducing of participatory intrahousehold decision making fits into women’s strategies for empowerment

Couple seminars catalysed women’s involvement in decision making over strategic farm and household affairs. As such, to an extent, couple seminars contributed to achieving women’s aspiration to be involved in strategic decisions which they find important to actively contribute to their household’s development. Hence, this supports women’s sense of agency. These effects may particularly aid women in or towards a pathway of ‘breaking through the wall of patriarchy’ where sharing decision-making power is possible. Intensive coaching did not additionally enhance women’s involvement in strategic farm and household decision making.

Women – as well as their husbands – are more likely to consider their households’ wellbeing and/or food security to have improved as a result of couple seminars; even if, still, not highly probable. Intensive coaching did not have additional impact. The achieved improved household welfare may relate to the positive effects on women’s decision-making power. Women perceive assuring their household is doing well and food secure as their duty, from which they derive appreciation and a sense of pride (sense of agency). This change can be considered valued and meaningful as women strive for their household’s welfare.

Women’s priority of enhanced (shared) access to household income from coffee was achieved to an extent, but only as a result of intensive coaching in participatory intrahousehold decision making. This suggests that norms and customs assigning access to income from coffee, and cash crops more in general, to men appear to be hard to defy. They require more than just awareness raising, as is done during couple seminars. This highly valued change may support women who are on or shifting to the ‘breaking through the wall of patriarchy’ pathway where sharing access to household income is feasible.

While women find transparency over household income complementary to access for their effective participation in strategic decision making, neither couple seminars, nor intensive coaching improved it. Women’s personal income and (shared) access to livestock did not increase either. Yet, these resources are important for women in the ‘circumventing the wall of patriarchy’ pathway to provide for themselves and their households, and to gain bargaining power for women in the ‘breaking through the wall of patriarchy’ pathway. The introduction of participatory intrahousehold decision making failed women in pursuing these priorities and strategies for their empowerment.

Lastly, despite the GHA’s emphasis on more gender-balanced work burdens and investments in household commons, the intrahousehold time allocation to reproductive versus productive tasks remained unchanged.

6. Conclusion

Some of the constraints to inclusive agricultural development in sub-Saharan Africa may be situated at the household level where spouses are not fully cooperative, and women have limited intrahousehold bargaining power. A more participatory way of intrahousehold decision making is expected to empower women through increasing their voice and effective decision-making power, which is otherwise limited in patriarchal contexts, and through reducing collective action problems, which otherwise compromise efficiency and equitable sharing of costs and benefits of household farming.

This study used a mixed method approach, combining qualitative inquiry and a field experiment, to investigate the impact of interventions with couples introducing participatory intrahousehold decision making in smallholder coffee farming households in central Uganda on different dimensions of women’s empowerment, including more subjective aspects of women’s sense of agency and achievements.

Qualitative inquiry showed that women’s empowerment within their household faces a ‘wall of patriarchy’. On a pathway towards empowerment of ‘breaking through the wall of patriarchy’, women have the opportunity to exercise agency and share access to resources with their husbands who do not strictly abide with prevailing patriarchal norms and customs. When ‘circumventing the wall of patriarchy’, women’s pathway towards empowerment comes down to strengthening their independence within the household by taking control over resources.

As a result of couple seminars that raise awareness about participatory intrahousehold decision making, women’s highly aspired involvement in strategic farm and household decisions increased to an extent. These advancements may facilitate ‘breaking through the wall of patriarchy’ and are valued by women as a way to actively contribute to their households’ welfare. Couple seminars made progress in household welfare more likely. This is an important achievement in itself that has great meaning to women as it answers to their priorities and sense of agency. The introduction of participatory intrahousehold decision making through intensive couple coaching contributed to some extent to achieving women’s priority of enhanced access to household income from coffee production, which is only feasible when ‘breaking through the wall of patriarchy’. Transparency over coffee income did not improve despite being equally important for women as access to income for their effective participation in strategic decisions. Women’s access to personal and livestock resources did not increase despite their importance for women’s independence when ‘circumventing’ and for women’s bargaining power when ‘breaking through the wall of patriarchy’. Spousal time allocation to productive, reproductive and domestic activities did not change.

Our study may face some limitations. First, it measured the impact of introducing participatory intrahousehold decision making. The study cannot quantitatively ascertain the extent to which decision-making processes in treated households became more participatory. Women’s qualitative accounts show that, in some households, decision-making processes changed and in others not. Furthermore, we acknowledge that participation in decision making does not always guarantee effective influencing of decisions or overcoming subordination, and that effectively influencing decisions may not need participation (Cleaver, Citation2001). Yet, for quantitatively operationalising agency we could only rely on reported participation, albeit confirmed by the husband, while qualitative accounts of women’s experienced agency capture some effective influencing of decisions other than by participation, for instance through complaint or threats. Second, the identification strategy for assessing impact of couple seminars versus no GHA exposure relied on strong assumptions that PSM deals with potential selection bias related to self-selection of couples into couple seminars. If this assumption is not entirely met, impact of couple seminars may be overestimated if these couples are more receptive to changing intrahousehold decision-making processes and women’s empowerment. Third, patriarchal norms and customs that define roles and responsibilities of men and women within their household are learnt and reinforced over many years. While we observe some changes in treated couples, this study did not assess change in norms and customs in the wider community. Even within treated couples, changing deep-rooted norms and customs may take longer than the one-year period covered by this study, need prolonged promotion, and require systematic interaction with the community to leverage collective agency and create wider support (Green, Wilke, & Cooper, Citation2020; Kyegombe et al., Citation2014).

Future research into drivers of women’s preferred pathway of ‘breaking through the wall of patriarchy’ in their households and constraints for men to relax the ‘wall of patriarchy’ would be worthwhile. Programmes addressing gender relations in households should acknowledge that the process of empowerment and undoing of customs and traditions may be long, gradual, non-linear and provide support along the journey. Apart from changing gender relations in households, supporting women in building economic power and gaining competencies remains important because it also gives their husbands and society instrumental reasons to rethink patriarchal gender constraints and welcome women’s involvement in economic development. But one should remain vigilant not to overburden women.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (1.2 MB)Acknowledgements

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No 702964. The interventions were funded by the Hanns R. Neumann Stiftung (HRNS) and received support from the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA), Uganda research station, as well. The Institute of Development Policy partly sponsored time for writing this article.

This study was granted ethical clearance by the Ethics Committee for the Social Sciences and Humanities of the University of Antwerp (SHW_15_41) and by the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (A564).

We are thankful for helpful comments by anonymous reviewers and participants in the research seminar of the Institute of Development Policy. We would like to specifically thank Fortunate Paska, Emma Doreen Arinaitwe, and Sarah Nabulobi from HRNS and research assistant Betty Nnajjuma for their valuable feedback and help in contextualising our findings. We would like to express our gratitude to Ghislaine Bongers, Stefan Cognigni and Daniel Kazibwe from HRNS, Laurence Jassogne from IITA and field research assistants Ronald Aroho, Apophia Kabazarwe, Patrick Mugisa, and Christopher Ssebadduka. Finally, we would like to express our gratitude to the women and men farmers who received us in their homes and gave us their valuable time to respond to our questions with interest and patience.

Data statement

The quantitative questionnaires, dataset, Stata code, and qualitative interview guide and transcripts are accessible at DOI: 10.17632/rb3zz4bx3p.2

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary materials

Supplementary Materials are available for this article which can be accessed via the online version of this journal available at https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2020.1849620

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. The interventions studied here aimed at changing decision-making processes within the household. Therefore, we focused on intrahousehold aspects of women’s empowerment even if collective agency beyond the household can be important as well (Alkire et al., Citation2013). This would, however, require in-depth analysis of women’s perceptions of its role which fell out of the scope of this study.

2. In Masaka-Kalungu 489 couples participated in couple seminars, in Mubende 754.

3. These include 166 couples from the Masaka-Kalungu and 180 from the Mubende sub-sample.We excluded couples whom we knew were polygamous. We controlled for the likelihood of a polygamous relationship by matching (a remaining 3.8 per cent of couples) (Inf.).

4. These include 159 couples from the Masaka-Kalungu and 186 from the Mubende sub-sample.

5. 41 couples were selected in areas across Masaka-Kalungu districts where HRNS did not implement its GHA, 55 couples in such areas across Mubende district.

6. The CACB group includes 263 couples that have potentially been exposed to spillovers by intensively coached couples who are part of the same POs (CA). (The CACB group also includes 82 couples from the Mubende sub-sample that have not been exposed to potential spillovers (CB) because we avoided the presence of intensively coached couples in the POs by delaying that intervention until after endline).If there have been positive spillover effects from intensively coached couples to couples in the CACB group who are part of the same POs, this could be a reason for underestimating the impact of intensive coaching (See Endnote 17 and OSM H).Another reason for underestimating the effect of intensive coaching in Masaka-Kalungu could be delayed implementation of home visits in 26 per cent of the intensively coached couples.

7. The encouragement status is a strong instrument as is evident from first stage regression results in Table E OSM B. The design of the study lends high credibility to the exclusion restriction.

8. We opted for PSM rather than regression analysis to control for these elements. PSM is a less parametric alternative for balancing the distribution of covariates across groups (Li, Zaslavsky, & Landrum, Citation2013). Where covariate adjustment makes estimated effects sensitive to model specification (e.g. linear or quadratic), this is not the case with PSM. PSM also avoids observations on the margin get a lot of weight. Added advantages of PSM using IPTW for the case of binary outcome variables, where conditional and marginal (unconditional) treatment effects do not necessarily coincide, include the estimation of marginal treatment effects, independent of the selection and correct modelling of the relation with covariates, in addition to increased precision (reduced standard errors) of estimated treatment effects as compared to covariate adjustment (Williamson, Forbes, & White, Citation2014).

9. Covariates included for PSM per sub-sample, both for T vs CACB and CACB vs CC: spousal age difference, wife’s age, husband has some secondary education, wife’s personal income, wife’s personally owned tropical livestock units (TLU), wife manages most important staple food crop alone, number of children, wife’s membership of a microfinance group, household food security, land size, husband’s personal income. Additionally for Masaka-Kalungu sub-sample: polygynous relationship (second wife reported by husband); and specifically for T vs CACB: wife has some secondary education. Additionally for T vs CACB in Mubende sub-sample: husband’s personally owned TLU, adoption intensify for coffee, house built with fire-baked bricks. Additionally for CACB vs CC in Mubende sub-sample: likelihood household’s wellbeing improved over time (reported by wife), wife has some secondary education.

10. We ignored non-compliance of the 13 couple seminar couples who had an additional intensive coaching, which may lead to overestimating the effect of couple seminars versus no GHA exposure.

11. 8 couples attrited from the Masaka-Kalungu sub-sample, 37 from the Mubende sub-sample.

12. Primary reasons for attrition were refused consent or death of one of the spouses and relocation.

13. Adjustment of p-values takes into account testing of seven hypotheses, including once proportion of coffee income in which the wife was involved in sales transactions and once transparency (both a function of woman reported total coffee income), while correcting for correlation between outcomes in the family of which hypotheses are not tested. In case of indicators based on agreed upon information, p-value adjustment takes into account five hypotheses. Correlation coefficients are included in Table J OSM D.

14. The aggregate empowerment score is based on an unweighted average evolution from baseline to endline of nine categories of household decision making, decision making on main food and cash crops and adoption of agricultural practices, ownership of food and cash crop plots, bicycle ownership, personally owned small livestock and poultry, and membership, input and leadership of any group.

15. See OSM E for the interview guide. Group participation was included in the interview guide to understand spillover between household and community spheres but was not a key focus in this study.

16. Time use data was not collected at baseline in Masaka-Kalungu.

17. A comparison of outcomes in the group of couples who received a couple seminar and was potentially exposed to spillovers (CA) and the group without spillovers (CB) points to positive spillover effects on the indicator of agreed upon improved household wellbeing and/or food security in the Mubende sub-sample (Table Q (13) OSM H). Such spillover effects could exist in the Masaka-Kalungu sub-sample as well. This implies the impact of intensive coaching on this outcome indicator may be underestimated.

18. See Table K OSM F for complete results including estimated coefficients of a dummy area fixed effects controlling for sub-sample Mubende, the constant and test statistics. Effects on differences in outcome indicators at end- vs baseline are included in Table O OSM G and intention to treat effects of T vs CACB in Table M.

19. See Table L OSM F for complete results including estimated coefficients of a dummy area fixed effects controlling for sub-sample Mubende, the constant and test statistics. Effects on differences in outcome indicators at end- vs baseline are included in Table P OSM G and intention to treat effects of T vs CACB in Table N.

20. We have added an arrow indicating how achievements, in turn, can contribute to women’s sense of agency, and an arrow indicating the influence of the community sphere on women’s (personal) resources through savings groups (Appendix B). Dashed arrows correspond to linkages described in the literature for which we have not found evidence in the interviews.

References

- Acosta, M., van Wessel, M., Van Bommel, S., Ampaire, E., Twyman, J., Jassogne, L., & Feindt, P. (2020). What does it mean to make a ‘joint’ decision? Unpacking intra-household decision making in agriculture: Implications for policy and practice. The Journal of Development Studies, 56(6), 1210–1229.

- Agarwal, B. (1997). Bargaining and gender relations: Within and beyond the household. Feminist Economics, 3(1), 1–51.

- Agarwal, B. (2001). Participatory exclusions, community forestry, and gender: An analysis for South Asia and a conceptual framework. World Development, 29(10), 1623–1648.

- Alderman, H., Hoddinott, J., Haddad, L., & Udry, C. (2003). Gender differentials in farm productivity: Implications for household efficiency and agricultural policy. In A. Quisumbing (Ed.), Household decisions, gender, and development: A synthesis of recent research (pp. 61–66). Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute.

- Alkire, S., Meinzen-Dick, R., Peterman, A., Quisumbing, A., Seymour, G., & Vaz, A. (2013). The women’s empowerment in agriculture index. World Development, 52, 71–91.

- Alsop, R., Bertelsen, M., & Holland, J. (2006). Empowerment in practice. From analysis to implementation. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Ambler, K., Doss, C., Kieran, C., & Passarelli, S. (2019). He says, she says: Exploring patterns of spousal agreement in Bangladesh. Economic Development and Cultural Change. Advance online publication. doi:10.1086/703082

- Arora, D. (2015). Gender differences in time-poverty in rural Mozambique. Review of Social Economy, 73(2), 196–221.

- Asfaw, S., & Maggio, G. (2017). Gender, weather shocks and welfare: Evidence from Malawi. The Journal of Development Studies, 54(2), 271–291.

- Ashraf, N. (2009). Spousal control and intra-household decision making: An experimental study in the Philippines. American Economic Review, 99(4), 1245–1277.

- Bain, C., Ransom, E., & Halimatusa’diyah, I. (2018). Weak winners of Women’s empowerment: The gendered effects of dairy livestock assets on time poverty in Uganda. Journal of Rural Studies, 61, 100–109.

- Baland, J. M., & Ziparo, R. (2018). Intra-household bargaining in poor countries. In S. Anderson, L. Beaman, & J. P. Platteau (Eds.), Towards gender equity in development (pp. 69–96). Helsinki: United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research.

- Bolwig, S. (2012). Poverty and gender effects of smallholder organic contract farming in Uganda (Uganda Strategy Support Program (USSP) Working Paper No. 8). Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute.

- Castilla, C., & Walker, T. (2013). Is ignorance bliss? The effect of asymmetric information between spouses on intra-household allocations. American Economic Review, 103(3), 263–268.

- Chiputwa, B., & Qaim, M. (2016). Sustainability standards, gender, and nutrition among smallholder farmers in Uganda. The Journal of Development Studies, 52(9), 1241–1257.

- Cleaver, F. (2001). Institutions, agency and the limitations of participatory approaches to development. In B. Cooke & U. Kothari (Eds.), Participation. The new tyranny? (pp. 37–55). London: Zed Books.

- Cornwall, A. (2016). Women’s empowerment: What works? Journal of International Development, 28(3), 342–359.

- De Brauw, A., Gilligan, D., Hoddinott, J., & Roy, S. (2014). The impact of Bolsa Família on women’s decision-making power. World Development, 59, 487–504.

- Doss, C. (2013). Intrahousehold bargaining and resource allocation in developing countries. The World Bank Research Observer, 28(1), 52–78.

- Doss, C., & Meinzen-Dick, R. (2015). Collective action within the household: Insights from natural resource management. World Development, 74, 171–183.

- Doss, C., Meinzen-Dick, R., & Bomuhangi, A. (2014). Who owns the land? Perspectives from rural ugandans and implications for large-scale land acquisitions. Feminist Economics, 20(1), 76–100.

- Doss, C., & Quisumbing, A. (2020). Understanding rural household behavior: Beyond Boserup and Becker. Agricultural Economics, 51(1), 47–58.

- Duflo, E., & Udry, C. (2004). Intrahousehold resource allocation in Cote d’Ivoire: Social norms, separate accounts and consumption choices (National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper, 10498). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Farnworth, C., Fones-Sundell, M., Nzioki, A., Shivutse, V., & Davis, M. (2013). Transforming gender relations in agriculture in Sub-Saharan Africa. Stockholm: Swedish International Agricultural Network Initiative.

- Fiala, N., & He, X. (2017). Unitary or non-cooperative intrahousehold model? Evidence from couples in Uganda. The World Bank Economic Review, 30(Suppl. 1), S77–S85.

- Fielding, D., & Lepine, A. (2017). Women’s empowerment and wellbeing: Evidence from Africa. The Journal of Development Studies, 53(6), 826–840.

- Green, D. P., Wilke, A. M., & Cooper, J. (2020). Countering violence against women by encouraging disclosure: A mass media experiment in rural Uganda. Comparative Political Studies, 53(14), 2283–2320.

- Hanmer, L., & Klugman, J. (2016). Exploring women’s agency and empowerment in developing countries: Where do we stand? Feminist Economics, 22(1), 237–263.

- Hannay, L. (2014, July 23). Women’s land rights in Uganda [Online guide]. Retrieved from https://www.landesa.org/wp-content/uploads/LandWise-Guide-Womens-land-rights-in-Uganda.pdf

- Heckert, J., Olney, D., & Ruel, M. (2019). Is women’s empowerment a pathway to improving child nutrition outcomes in a nutrition-sensitive agriculture program?: Evidence from a randomized controlled trial in Burkina Faso. Social Science & Medicine, 233, 93–102.

- Howard, P. L., & Nabanoga, G. (2007). Are there customary rights to plants? An inquiry among the Baganda (Uganda), with special attention to gender. World Development, 35(9), 1542–1563.

- Hunt, J., & Kasynathan, N. (2001). Pathways to empowerment? Reflections on microfinance and transformation in gender relations in South Asia. Gender and Development, 9(1), 42–52.

- Ivankova, N., Creswell, J., & Stick, S. (2006). Using mixed-methods sequential explanatory design: From theory to practice. Field Methods, 18(1), 3–20.

- Iversen, V., Jackson, C., Kebede, B., Munro, A., & Verschoor, A. (2011). Do spouses realise cooperative gains? Experimental evidence from rural Uganda. World Development, 39(4), 569–578.

- Jacobs, K., & Kes, A. (2015). The ambiguity of joint asset ownership: Cautionary tales from Uganda and South Africa. Feminist Economics, 21(3), 23–55.

- Johnson, N., Kovarik, C., Meinzen-Dick, R., Njuki, J., & Quisumbing, A. (2016). Gender, assets, and agricultural development: Lessons from eight projects. World Development, 83, 295–311.

- Kabahinda, J. (2018). On-the-ground perspectives of women’s land rights in Uganda. Development in Practice, 28(6), 813–823.

- Kabeer, N. (1999). Resources, agency, achievements: Reflections on the measurement of women’s empowerment. Development and Change, 30(3), 435–464.

- Kabeer, N. (2001). Conflicts over credit: Re-evaluating the empowerment potential of loans to women in rural Bangladesh. World Development, 29(1), 63–84.

- Kasente, D. (2012). Fair trade and organic certification in value chains: Lessons from a gender analysis from coffee exporting in Uganda. Gender and Development, 20(1), 111–127.

- Klein, E., & Ballon, P. (2018). Rethinking measures of psychological agency: A study on the Urban Fringe of Bamako. The Journal of Development Studies, 54, 1284–1302.

- Kyegombe, N., Abramsky, T., Devries, K. M., Starmann, E., Michau, L., Nakuti, J., … Watts, C. (2014). The impact of SASA!, a community mobilization intervention, on reported HIV-related risk behaviours and relationship dynamics in Kampala, Uganda. Journal of the International Aids Society, 17(1), 19232.

- Lecoutere, E., & Jassogne, L. (2019). Fairness and efficiency in smallholder farming: The relation with intrahousehold decision-making. The Journal of Development Studies, 55(1), 57–82.

- Li, F., Zaslavsky, A., & Landrum, M. (2013). Propensity score weighting with multilevel data. Statistics in Medicine, 32(19), 3373–3387.

- Malapit, H., Quisumbing, A., Meinzen-Dick, R., Seymour, G., Martinez, E. M., Heckert, J., … Team, S. (2019). Development of the project-level women’s empowerment in agriculture index (pro-WEAI). World Development, 122, 675–692.

- Malhotra, A., Schuler, S., & Boender, C. (2002). Measuring women’s empowerment as a variable in international development (Background paper prepared for the World Bank workshop on poverty and gender: New Perspectives, Vol. 28). Washington, DC: World Bank.

- McCarthy, N., & Kilic, T. (2017). Stronger together: Intrahousehold cooperation and household welfare in Malawi (Policy Research Working Paper, WPS 8043). Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Munro, A. (2018). Intrahousehold experiments: A survey. Journal of Economic Surveys, 32, 134–175.

- Nannyonga-Tamusuza, S. (2009). Female-men, male-women, and others: Constructing and negotiating gender among the Baganda of Uganda. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 3(2), 367–380.

- Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Peterman, A., Quisumbing, A., Behrman, J., & Nkonya, E. (2011). Understanding the complexities surrounding gender differences in agricultural productivity in Nigeria and Uganda. The Journal of Development Studies, 47(10), 1482.

- Quisumbing, A., & Maluccio, J. (2003). Resources at marriage and intrahousehold allocation: Evidence from Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Indonesia, and South Africa. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 65(3), 283–327.

- Rugadya, M. (2010). Women’s land rights in Uganda: Status of implementation of policy and law on women’s land rights. Addis Ababa: United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, African Centre for Gender and Social Development.

- Sankoh, A., Huque, M., & Dubey, S. (1997). Some comments on frequently used multiple endpoint adjustment methods in clinical trials. Statistics in Medicine, 16(22), 2529–2542.

- Sell, M., & Minot, N. (2018). What factors explain women’s empowerment? Decision-making among small-scale farmers in Uganda. Women’s Studies International Forum, 71, 46–55.

- Seymour, G. (2017). Women’s empowerment in agriculture: Implications for technical efficiency in rural Bangladesh. Agricultural Economics, 48(4), 513–522.

- Sraboni, E., Malapit, H., Quisumbing, A., & Ahmed, A. (2014). Women’s empowerment in agriculture: What role for food security in Bangladesh? World Development, 61, 11–52.

- Williamson, E., Forbes, A., & White, I. (2014). Variance reduction in randomised trials by inverse probability weighting using the propensity score. Statistics in Medicine, 33(5), 721–737.

- Yoong, J., Rabinovich, L., & Diepeveen, S. (2012). The impact of economic resource transfers to women versus men: A systematic review. London: Institute of Education, University of London.

Appendix

Appendix A. Definition of outcome indicators

A first outcome indicator for resources is the share of household tropical livestock units (TLU), calculated based on cattle and small livestock, excluding poultry, the wife reported to personally or jointly own, which indicates her access to household assets (Share TLU). We calculated a similar indicator based on averages reported by husband and wife for a robustness test (Share TLU A). We used the share of total household income from selling coffee in which the wife was involved - personally or jointly with her husband - in doing the sales transaction, including receiving the money, as an indicator of women’s access to household resources. One indicator is based on women reported data (Share coffee income), the other on averages reported by husband and wife (Share coffee income A). We used the ratio of wife reported versus husband reported total household coffee income as an indicator of transparency over income (Transparency), assuming that the level of transparency is higher if wife and husband report approximately the same amount. A final indicator of resources takes the value one if the wife reported she personally earned any income from off-farm activities, fishing, sales of livestock and/or remittances in three months prior to endline (Personal income).

For measuring impact on equality of investments in the household commons through time use, we used the difference in proportion of work time (i.e. total time allocated to productive, reproductive and domestic activities) wife and husband reported to allocate to tasks in the reproductive and domestic sphere as an indicator (Time).