?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Shared experiences but diversified developments make Africa an interesting region in which to investigate the impact of education on democracy, and the role of academic freedom in this impact. As building expertise takes time, we focus on the causality between past experience of academic freedom and electoral democracy. Our theory is that independent experts advocating free and fair elections are acclaimed, which makes rigging elections a costly strategy for rulers. Using the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) index of Academic Freedom, and the Generalized method of moments (GMM) technique to estimate a dynamic panel model, we find a positive impact of preceding academic freedom on the quality of elections after the Post-Cold war democratic transitions. The result is robust when we check reverse causality and country-specific effects such as the initial level of democracy or dependence on oil exportation. The analysis is robust to indicators measuring democracy by accountability of the executive and Polity2 and Freedom House Indices as alternatives to V-Dem measures of democracy. We discuss the observed heterogeneity of countries showing a counterintuitive relationship. The study highlights the significance of scholars as a channel through which education supports democracy.

KEYWORDS:

1. Introduction

Indicators measuring freedom of expression, including that of academics, are standard components of democracy rankings. The relationship between education and democracy is well recognised: a high level of education is one of the social requisites of democracy (Lipset, Citation1959). Less attention is paid to the causal relationship between academic freedom and democracy. Nevertheless, the introduction and implementation of legislation allowing political competition and popular participation requires expertise beyond common knowledge and experiences of other societies only. Democratic reforms need to be monitored, assessed and adjusted with expertise that covers local conditions. Democratic governance and accountability are not possible without evidence-based knowledge.

Our assumption is that the ability of scholars to participate in political discussions in their home countries contributes not only to the competence of decision-making but also to the quality and resilience of democratic institutions. Freedom to disseminate knowledge through research and education on the functioning, form and content of democracy can sustain it and prevent major setbacks. Furthermore, as research work itself, not to mention research training and higher education, takes time, our theory is that the higher the level of academic freedom before and at the time of transitions from one-party, non-party or military rule to multiparty competition, the better the prospects of its consolidation. In addition to human capital supporting democracy, i.e. understanding of the functions of political institutions, education contributes to political socialisation, when educated people encourage their peers to participate (Glaeser, Ponzetto, & Shleifer, Citation2007, p. 88).

We test the influence of the level of academic freedom preceding the post-Cold war democratic transitions on the subsequent conduct of elections, which we take as a critical ingredient of democratic consolidation in Africa. While many scholars such as Schedler, according to whom the very concept of democratic consolidation should be abandoned, define ‘electoral democracy’ pejoratively as a ‘diminished subtype’ of democracy (Schedler, Citation1998, p. 93), our approach is that it is the quality of elections that matters. That the rigging of elections is common, if not a norm, in a large part of the world (Cheeseman & Klaas, Citation2018) only highlights the importance of electoral democracy. Teorell, Coppedge, Lindberg, and Skaaning (Citation2019), with reference to Dahl’s famous definition of polyarchy (Citation1971, Citation1989), argue that electoral democracy must be measured not only by the quality of elections, but also by the universality of voting rights, appointment of the head of state and parliament through popular elections, the right to form political parties, and freedom of expression. While the latter overlaps with our independent variable, universal voting rights, apart from South Africa, were largely established in African countries right after their independence and have persisted since then. Same concerns elected head of state and parliament – interrupted by military coup’s, but regularly reintroduced soon after. The right to form political parties, in turn, was the essence of the transitions to multiparty competition. For our analysis, it is thus the quality of elections that can be regarded as the most pertinent indicator of the subsequent level of electoral democracy. However, for robustness checks, we have analysed the influence of academic freedom to freedom of association, too. Furthermore, we also look at the relationship between academic freedom and measurements of executive accountability, which, along with the quality of elections, previous literature has identified as a major issue of democratic consolidation in Africa.

Africa is a suitable region to investigate the relationship between academic freedom and democracy. This is not to deny the importance of the same questions elsewhere and the global challenges posed by autocratisation (Daly, Citation2019). Rather, we think that the African experience has general relevance. Although electoral political competition has long roots in Africa (Cowen & Laakso, Citation1997), the end of the Cold war brought the rules and rationale of liberal democracy to the centre of public debates there like in no other continent. Democratic transitions affected the whole continent, both state-controlled and market-oriented economies, within a relatively short period. Before 1990, only a few African countries implemented multiparty systems, but by 1995 de jure one-party or non-party systems had become exceptions. Political volatility and heterogeneity have prevailed, however. By 2021, democratisation in Africa has stagnated, although not reversed as dramatically as in other continents. Electoral violence (Laakso, Citation2020a) and ‘constitutional coups’ extending the tenure and powers of the executive (Reyntjens, Citation2020) appeared to be typical setbacks. These are also setbacks where academics with their knowledge could have a say.

A large part of the literature analysing constraints on democracy in Africa builds on ‘grand theories’ of African otherness. The focus has been on factors distinguishing the continent from the rest of the world and the West in particular: neopatrimonialism, weak state institutions and a political economy of dependency. Research, however, has also noted simple causal effects of historical events. Wantchékon and García-Ponce (Citation2013) argue that countries with high levels of urban protests during anti-colonial movements have developed more democratic institutions than those with rural insurgencies. Coulibaly and Omgba (Citation2021) show that democratic consolidation has been most successful in countries with large diasporas at the time of their democratic transitions. We, too, look at the impact of past experiences on democracy. Our empirical analysis shows that academic freedom, with different lag structures, has a positive and significant relationship with the current level of democracy in Africa.

This article is structured as follows. Section 2 presents a brief overview of the literature of democratisation in Africa; Section 3 discusses approaches to academic freedom; Section 4 describes our theory and econometric model; Section 5 presents the data; Section 6 discusses the main results; Section 7 shows robustness checks; Section 8 discusses heterogeneity in the data and reveals some deviant cases; and finally, Section 9 concludes and raises new research questions.

2. Democracy and its limits in Africa

Bratton and Van de Walle (Citation1997) published the first systematic attempt to understand the democratic transitions in Africa between 1989 and 1994, when 23 formerly one-party states held their first multiparty elections. The authors used Freedom House data and focused on neopatrimonialism and clientelistic relations in the use of state resources for political support as constraints on political rights, but also noted the positive impact of experiences of political competition prior to 1990. Their overall view of democratic consolidation in Africa, however, was pessimistic. And their research question, why some African countries seem to succeed in democratisation while others fail, is still pertinent.

International databases, such as Freedom House, V-Dem and the Polity project, as well as Afrobarometer surveys of public opinion on the level of democracy, demonstrate the heterogeneity of Africa. To give just a few examples, Ghana with its experience of military rule has succeeded in its democratic transition, while Zimbabwe has remained authoritarian in spite of its longstanding multiparty system, and in 2021 democracy was threatened in Senegal, one of its traditional strongholds in the continent. In a comprehensive overview of the first two decades of Africa’s democratisation, Lynch and Crawford distinguished several areas of simultaneous progress and setbacks: increasingly illegitimate, but still ongoing military rule; regular elections and democratic institutionalisation, but personal rule and corruption; new parties with political programmes, but identity based mobilisation; vibrant civil societies, but high levels of violence; economic growth, but poverty; and donor community promoting democracy, but supporting authoritarian regimes (Lynch & Crawford, Citation2011, p. 276). Accounting for this variety has no doubt been difficult.

Bratton and Chang (Citation2006) explained the different levels of democracy with differences in state capacity and rule of law which they measured by using Afrobarometer survey data and the World Bank Institute’s governance indicators. Not surprisingly, the correlation between democracy and these two was high, but instead of one-way causality, the authors acknowledged the constant interaction of state structures and democratic procedures. A weak state, rather than being a factor explaining a low level of democracy, appeared to be a phenomenon related to it. Similarly, Van Cranenburgh (Citation2008) observed a link between concentration of powers in the executive presidency, the ‘big man’ rule, and democratic breakdowns.

Researchers have also pointed to the importance of economic underdevelopment, income inequality and dependency on aid as major hindrances for democracy in Africa (Ake, Citation2000; Mkandawire, Citation2005). Peiffer and Englebert (Citation2012) measured the different mixture of external relations and economic dependence and showed association between ‘extraversion vulnerability’ and democratisation. The so-called ‘resource curse’, a negative correlation between natural resources and democracy (Jensen & Wantchekon, Citation2004; McFerson, Citation2010), has been referred to in explanations of why resource-poor countries, like Mozambique and Benin, have succeeded better in democratic transformations than resource-rich ones like Angola or Gabon. On the other hand, Botswana, whose economy is heavily dependent on the earnings generated from diamond mining, is one of the most stable democracies in the continent. Dependence on oil wealth appears to be more critical in this regard (Anyanwu & Erhijakpor, Citation2014; Arezki & Gylfason, Citation2013).

Institutional change in the organisation of the political competition in the form of multipartyism has remained, however (Acemoglu, Johnson, & Robinson, Citation2001; Aidt & Leon, Citation2016; Brückner & Ciccone, Citation2011). What seems to have been critical for democratic consolidation is not the intensity of political competition as such, nor even the various strategies used by the competing parties and rulers to stay in power, but how this competition has been framed, monitored and sanctioned in society at large. In order to understand this social condition of the political competition, it is useful to look at the limitations of multipartyism highlighted in the literature.

The first one concerns the quality of elections. While electoral violence, for instance, is not rare in political competition undergoing major transformations, one would assume that repeated rounds of multiparty elections would make them increasingly peaceful. This has not been the case in Africa although variation between African countries, within countries and even from one election to another, is high. According to Burchard, in the early 1990s 86 per cent of African elections witnessed violence. Since then the percentage has been around 50 per cent, while the international figure is below 20 per cent (Burchard, Citation2015, p. 11). Pre-election violence is usually connected to the strategies of the government and its supporters to manipulate the process, while post-election riots typically follow as spontaneous reactions of the losing opposition (Linke, Schutte, & Buhaug, Citation2015; Ojok & Achol, Citation2017; Söderberg Kovacs & Bjarnesen, Citation2018).

The second limitation relates to the concentration of powers in the executive branch and its weak accountability (Cranenburgh, Citation2009). Nothing manifests this better than recurrent cases to remove term limits for the incumbent head of state (Reyntjens, Citation2020), with examples including Cameroon, Djibouti, the Republic of Congo, Burundi, Rwanda and Uganda. And this is happening even though the African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance (in force since 2012, but not signed and ratified by all member states of the African Union) explicitly stipulates that if you change the constitution, it should be for your successor, not for yourself.

3. Why academic freedom?

Correlation between higher education and democracy is undeniable, but causality is not (Valero & Van Reenen, Citation2019). Acemoglu, Johnson, Robinson, and Yared (Citation2005) concluded that education has no effect on democracy. When controlled for country-specific effects, the positive correlation disappeared. Castelló-Climent (Citation2008, p. 189) and Apergis (Citation2018), in turn, emphasised the importance of primary, instead of higher, education for democratic consolidation.

One possible link between education and democracy relates to cognitive and motivational attributes. In their study of pro-democracy attitudes using data from the Afrobarometer survey in 18 African countries, Evans and Rose found that education enhances attention to, and comprehension of, politics (Evans & Rose, Citation2012, pp. 499, 513). Higgins defended humanities and social sciences in South African universities by stating that these constitute ‘the substance of both efficient and reflexive communication, as well as a significant element in critical and creative thinking’ (Higgins, Citation2014, p. 80). In the words of Edward Said, it is the responsibility of intellectuals ‘to speak the truth to power’ (Said, Citation1994, p. 97). Several researchers have noted that the democratic impact of universities extends well beyond those educated in them (Bryden & Mittenzwei, Citation2013; Cole, Citation2017; Post, Citation2012). However, the ability of scholars and students to produce and disseminate knowledge of public decision-making can have an impact only if academic expertise is protected, appreciated and utilised.

African scholars’ experiences of academic freedom have been mixed. After independence, universities were ‘widely viewed as a route to national liberation’ (Mama, Citation2006, p. 5), although the new rulers soon regarded discussion on democracy as ‘irrelevant’ (Oyugi, Citation1989). At the end of the 1980s, mobilisation against economic adjustment policies and authoritarianism involved intellectuals, too (Mkandawire, Citation2005). In 1990, the Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa (CODESRIA) and Africa Watch published the Kampala Declaration on Intellectual Freedom and Social Responsibility, according to which the intellectual community has the responsibility to struggle for and participate in the struggle of the popular forces for their rights and emancipation. As Diouf argued, the political transitions had highlighted the importance of academic freedom but not necessarily improved it (Diouf, Citation1994, p. 335).

Two decades later Appiagyei-Atua, Beiter and Karran in their survey of the legal and statutory protection of academic freedom in African universities showed great variety across countries. In their ranking of 44 countries, Eritrea and Gabon, which are low also in democracy measurements, got the lowest scores, while South Africa, Cape Verde and Ghana, which perform well in democracy measurements, too, got the highest (Appiagyei-Atua, Beiter, & Karran, Citation2016, pp. 109–110).

The legal setting, however, is only one dimension of academic freedom identified in the higher education literature (Abdel Latif, Citation2014). Difficulties to define it unambiguously have hampered its measurements and use in empirical studies (Grimm & Saliba, Citation2017, p. 48). The V-Dem index, which is based on expert views and surveys, was introduced in 2020, and consists of the widest range of indicators available so far (Spannagel, Kinzelbach, & Saliba, Citation2020).

4. The theory and model

The first premise of our theory is that in a society with educated citizens electoral democracy gives legitimacy to rule. The ruling elites have incentives to win elections. And second, that higher education contributes to the legal, logistical and information expertise needed to conduct elections. Third, we assume that academic freedom supports independent thinking in higher education: independent experts who advocate free and fair elections are acclaimed by their peers, or shamed if they accept manipulation. Rigging elections thus becomes a costly strategy for rulers to win elections. Conversely, lack of academic freedom supports acquiescence to authoritarian rule. The ruling elite rewards experts who manipulate elections for its benefit, or punish those who criticise such manipulation, and elections are rigged. A symmetrical assumption can be made of the accountability of the executive. Academic freedom enables critical expert views of public decision-making, and it is in the interest of the incumbent to take these into consideration. Academic acquiescence, on the other hand, ensures the educated elite’s silence or support for the rulers irrespective of their competence.

This leads to our hypothesis that high levels of academic freedom support the quality of subsequent elections and the accountability of the executive. With reference to Acemoglu et al. (Citation2005) and Castelló-Climent (Citation2008), who focused on the relationship between education and democracy, we estimate a similar dynamic model as follows:

Quality of elections is lagged for one period in order to capture the persistence of electoral quality. tests whether

(using different lag structures) contributes to better quality of elections.

is the ratio of total enrolment corresponding to the level of education in tertiary.

is included to control for country-specific effects, i is the country, t is the period from 1990 to 2019. We expect that the higher the indicator of academic freedom in the past, the better the current quality of elections.

The main advantage of estimating a panel model is that it enables control of unobservable variables that are country-specific, and whose omission may trigger biased estimated coefficients in a pure cross-sectional regression. The first difference Generalised Method of Moments (GMM) by Arellano and Bond (Citation1991) is considered to be an appropriate technique to estimate panel data, among others, but it is not able to deal with issues of unobservable heterogeneity and may not necessarily be an efficient method to estimate EquationEquation (1)(1)

(1) due to the repeating value in some data. Although data vary significantly between countries, they remain quite stable within a country for consecutive years. For instance, the countries in our sample display the same value of quality of elections and of academic freedom for many consecutive years within the period under scrutiny, which implies that the variation in the conduct of elections during this period is low. Thus, by applying the GMM in difference most of the variation in the data across countries disappears. This may surge the measurement error bias by mounting its variance relative to the variance of the true signal (Griliches & Hausman, Citation1986). Furthermore, when the explanatory variables hold persistency, the lagged levels of these variables are weak instruments for the differences (Blundell & Bond, Citation1998).

Consequently, it is preferable to explore a technique that captures the bulk of variation in the data and improves the quality of the estimated coefficients. For this end, we explore the system-GMM estimator, which not only estimates the equations in first differences but also estimates equations in levels that are instrumented with lagged first differences of the corresponding explanatory variables. In order to explore these additional instruments, there is a need to identify an assumption that the first differences of the explanatory variables are not correlated with the unobserved specific effect. Although the specific effect may be correlated to the explanatory variables, the correlation is supposed to be invariant over time. Thus, the additional moment condition for the equation in levels is

Where

The Monte Carlo simulations show that the system-GMM estimator is superior to the first-differences GMM, as long as the additional moment conditions are valid. We check the validity of the moment conditions by referring to the well-known test of over-identifying restrictions of Sargan–Hansen and by testing the null hypothesis of which the error term is not serially correlated (Sargan, Citation1958). Moreover, we check the validity of the additional moment conditions related with the level equation exploiting the Sargan–Hansen test.

5. The data

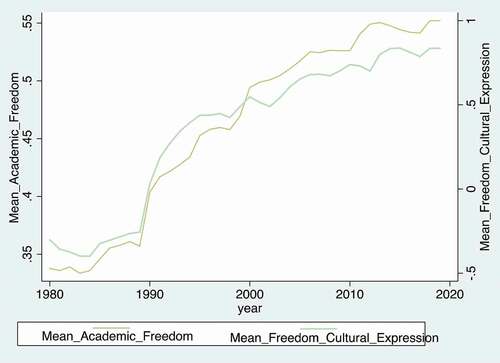

Our measures of academic freedom and democracy are taken from the V-Dem database, which provides a multidimensional collection of indicators of democracy. For academic freedom, we are using the Academic freedom index, which in addition to Freedom of academic and cultural expression includes its institutional aspects (see Spannagel et al., Citation2020). shows the high correlation between the two variables and the overall trend. The average level of academic freedom in Africa increased sharply at the time of democratic transition.

In order to grasp challenges of democratisation in Africa, we use the V-Dem Clean elections index. As explained in the Introduction, we take the quality of elections as the most critical component of electoral democracy in post-Cold war Africa. We are not using the V-Dem Electoral democracy index, because it includes Freedom of academic and cultural expression and is thus endogenous to our independent variable. To justify our choice further, we have checked the robustness of our results with Freedom of association index, a component of Electoral democracy index gauging the freedom of civil society organisations and parties to form, operate and participate in elections. This variable is not connected to the Academic freedom and cultural expression index.

In 1990 the average Clean elections index in Africa was 0.418 with a standard deviation of 0.253, while in 1995 the average value was 0.445 (). As a comparison we also included two commonly used proxies for democracy, namely Polity2 (Marshall, Gurr, & Jaggers, Citation2019) and Freedom House indices. The variance of all the indicators reveals divergent developments in different countries: some countries shifted successfully from autocratic systems to democracy, while others failed.

School enrolment is included as a control variable. As shown in Figure A1 the ratio has grown rapidly. It is noteworthy, however, that in 2018, Africa, with the level of 17 per cent, still lags behind the world average of 38 per cent Figure A2 shows that the level of school enrolment does not have a clear linear relationship with the Clean elections index.

6. Results

As initial evidence, Figures A3–5 reveal the correlation between the democracy indicators averaged over the period 1990–2019 and academic freedom averaged for the preceding period 1980–2009. Broadly, the figures show positive correlations, with all indicators.

shows the results from estimating EquationEquation (1)(1)

(1) under different specifications. Columns (1), (2), (3) and (4) present results of the static analysis (Pooled OLS). In column (1), the cross-sectional analysis regresses the average level of academic freedom before democratic transition (1980–1989) on the average level of democracy during the post-Cold war period (1990–2019) using the Academic freedom index and Academic freedom and cultural expression index, respectively. Columns (2) and (4) regress the average level of academic freedom between 1980 and 2009 on the level between 1990 and 2019 using the Academic freedom index and Academic freedom and cultural expression index, respectively.

Table 1. Clean elections and preceding academic freedom

The estimated equation assumes that. In line with our hypothesis, the results reveal that the correlation between clean elections and academic freedom is positive. The result holds with both indices (Academic freedom and Freedom of academic and cultural expression). This suggests that the higher the preceding level of academic freedom, the better the quality of elections after democratic transition.

The results, however, change when controlling for country-specific effects using the fixed-effect and the first-difference GMM estimators. When we apply the fixed-effect estimator, we lose the significance and size of the coefficient of academic freedom. The lagged value of the Clean elections index remains comparable to the other specifications (column 5 and 6). We obtain the same results with the difference GMM estimator (column 7 and 8). This implies that the correlation between academic freedom and the quality of elections is related to country-specific effects. In an analysis that focused on a similar, although not identical, relationship between education and democracy, Acemoglu et al. argued ‘that the cross-sectional relationship between education and democracy is driven by omitted factors influencing both education and democracy rather than a causal relationship‘ (Citation2005, p. 48). An alternative interpretation is that when the variable of interest shows persistency, the fixed effect is not an appropriate estimator. It may trigger a measurement error bias by exploring the within country variation in the data. Furthermore, the first-difference GMM estimator may raise an issue of weak instruments. Hauk and Wacziarg (Citation2009), for instance, argue that human capital accumulation reveals a sizeable negative biased effect on growth in Monte Carlo simulations due to weak instruments. When the model includes persistent variables within which the variation is very low, the gains from reducing the omitted variable under fixed–effects are more than offset by an increase in the exacerbation of the measurement error bias, which makes using the fixed effect estimator in this context unadvisable (Castelló-Climent, Citation2008).

We explore the system-GMM estimator, which is more appropriate to control for country-specific effects. In addition, when considering cross-country variation in the data, the results are similar to our expectations and do not reject our null hypothesis. The results confirm the positive impact of the Academic freedom index and Academic freedom and cultural expression index on the quality of elections. As shown in columns (9 and 10), the coefficient of academic freedom is positive, sizeable enough and significant at the level of 5 per cent. The result is robust and corroborates Castelló-Climent (Citation2008) and Apergis (Citation2018).

Comparison of different lag structures for academic freedom shows that the five-year lag is less significant than the 10-year lag (Table S1.2). This confirms our assumption that the impact of academic freedom on democracy takes time. We also explored a longer lag (15-year lag and 20-year lag) to check our assumption. Results (Table S1.3) show a sizeable and significant coefficient for the 15-year lag for most of the specifications, but less for the 20-year lag (Table S1.4). These results corroborate Valero’s and van Reenen’s finding of the association between historical university presence and ‘approval of a democratic system’ (Valero & Van Reenen, Citation2019, p. 65), but highlight also their caution that longer time frames can bring more uncontrolled factors into play (Citation2019, p. 60).

7. Robustness

To examine the robustness of the results, we first exclude countries that held competitive multiparty elections prior 1990 to detect reverse causation. Then, we address whether academic freedom has had a positive and significant effect on the quality of elections in countries that introduced multiparty political systems during the period. Thus, in column (11) we include only the countries that enter the sample as non-competitive systems in 1990 in accordance to the classification of Bratton and Van de Walle (Citation1997, for a list of countries, see the Appendix). The coefficient of academic freedom is positive and highly significant. The level of academic freedom in those countries cannot be interpreted as a result of their democracy.

Next, we exclude oil-exporting countries from the sample. Although the number of countries where oil revenues account for more than 35 per cent of their exports is only six, removing them from the sample may change the results. As is shown in the literature, over-reliance on oil revenue supports authoritarian rule, but can also make the countries politically unstable (Bjorvatn & Farzanegan, Citation2015; Ross, Citation2001) reflecting the rent-seeking behaviour of the political elite (Omgba, Citation2009). This means that possible improvement in the quality of elections in these countries may be due to other factors than the experience of academic freedom. As shown in column (12), the estimated coefficient of academic freedom remains positive and highly significant and its magnitude increases dramatically in comparison to the previous specifications. This suggests that our main finding is not affected by the specific features of these economies.

Finally, in the last two columns we examine whether the relationship between academic freedom and quality of elections depends on the level of income (World Bank classification). The results show that the positive relationship between academic freedom and quality of elections holds (columns 13 and 14). The level of income, however, plays a role. The coefficient is less significant in upper and lower middle-income countries with an estimated coefficient of 0.082 compared to 0.041 in low-income countries confirming the finding of Alemán and Kim that ‘the democratizing effect of education is stronger at lower income levels’ (Citation2015, p. 6).

For the purpose of additional robustness analysis, we explore the 10-year lag for academic freedom, which shows robustness among the different specifications compared to the other long lag structure. We conduct regression using additional control variables. These include the 1980 stock of emigrants in the OECD countries from the database of Brücker, Capuano, and Marfouk (Citation2013). Diaspora can transfer knowledge, awareness and help to develop civil society at home. The other control variables include total population (WDI), infant mortality rate (WDI), and educational attainment, which are often highlighted in the literature as potential determinants of institutional changes (Castelló-Climent, Citation2008). The inclusion of these variables is crucial in order to avoid biased results. In Table S2 the additional control variables are added one by one.

The results show that adding the control variables does not alter the main finding. The coefficient of academic freedom remains positive and in most specifications strongly significant at the level of 1 per cent. This reflects that results of the basic specification are robust and not dependent on the omission of the control variables. Furthermore, each of the potential control variables holds the expected sign, with different levels of statistical significance.

Emigrants to OECD countries seem to have a positive influence on democracy in Africa. These results corroborate the findings of Docquier, Lodigiani, Rapoport, and Schiff (Citation2016) that emigration to liberal democracies correlates with democracy in developing countries. Mercier (Citation2016) has noted the importance of political leaders’ experience of studying in high-income OECD countries and Coulibaly and Omgba that ‘the longer the duration of the migrant population, the greater the impact on democracy’ (Citation2021, p. 174).

Our other robustness checks relate to the aforementioned V-Dem indicators measuring executive accountability: judicial constraints, respect of the constitution and range of consultation, along with two commonly used proxies for democracy: Polity2 score of Polity V and Freedom House indices (political rights and civil liberties). Furthermore, we checked the robustness of the results with V-Dem Freedom of association index. In an attempt to allow the comparison across different measures of democracy and following Acemoglu, Johnson, Robinson, and Yared (Citation2008), each indicator was normalised on a scale ranging from zero reflecting autocracy to 1 reflecting full democracy. Table S3 shows the results and reveals that the coefficient of Academic freedom remains positive and significant in all estimations, in accordance with our assumption.

8. Deviant cases

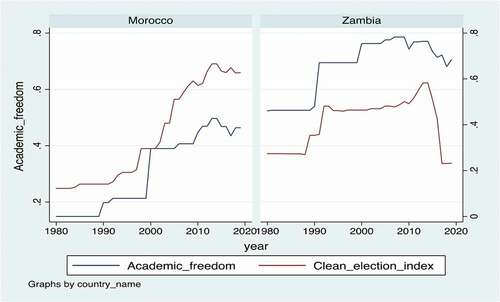

We have also observed relationships that contradict our theory and thus deserve to be examined in more detail. below shows the trends in the Academic freedom and the Clean elections indices in two most striking cases in this regard over the period 1980–2019: Morocco with an exceptionally good quality of elections when compared to the preceding low level of academic freedom and Zambia from the other end of the spectrum. In both countries, the level of academic freedom seems to follow rather than precede political developments. Both are also significant examples due to their well-established academic sectors.

Morocco is a monarchical state, where the constitutional and informal powers of the king are extensive. King Hassan II started the process of political liberalisation in 1990s with the establishment of an advisory council for human rights, and then referendum of the constitution that led to a directly elected Chamber of Representatives (White, Citation1997). King Mohammed VI, who succeeded Hassan II in 1999, has continued political opening and constitutional reforms. Although civil society activism preceded these developments, the outcome has been characterised as ‘a neo-patrimonial process of top-down “consensus building”’ (Sater, Citation2009, p. 189) strengthening rather than limiting the position of monarch.

Morocco’s good performance in electoral democracy thus stems from the endurance of the same regime. Only a setting where elections can challenge the regime would serve as a litmus test for the role of independent experts to advocate free and fair elections. Contemporary improvement of academic freedom, however, can be assumed to support such scenarios.

Zambia, in turn, is an example of a country where after reinstating a multiparty system in 1991 as a response to intense popular protests, the regime lost in the first competitive elections. The Movement for Multiparty Democracy (MMD) replaced the United National Independence Party (UNIP). MMD retained this position until 2011 when Michael Sata of the Patriotic Front (PF) gained power. By 2021 Zambia has experienced more than one electoral turnover after the transition showing democratic consolidation in this minimalist ‘result-oriented’ sense (Rakner, Citation2017, p. 526). Against this background, electoral violence and allegations of vote-rigging affecting the quality of the elections in a dramatic way after the mid-2010s have been unexpected. Rampant corruption has coincided with very intense competition between the ruling party and the opposition.

Academic freedom was relatively well respected during one-party rule and Kaunda’s African humanism emphasising education, although ideological pluralism was suppressed (Murove & Chitando, Citation2018, p. 330). As shows, the level of academic freedom rose rapidly after the political transition, but since then has taken steps backward along with the deteriorating quality of elections. An example of this was Zambian authorities’ decision to refuse entry to a Kenyan professor of law to give a lecture on China’s influence in Africa, possibly related to simultaneous revelations of financial mismanagement of government’s economic co-operation with China (Matambo, Citation2020, p. 105). This suggests that corruption has diminished the positive impact of preceding academic freedom on democracy in Zambia and then also academic freedom itself. The drop in the quality of elections is likely to be only temporary, but if the level of academic freedom deteriorates further, knowledge-based attempts to promote free and fair elections might be in vain.

9. Conclusions

Academic freedom is a fundamental norm in democracies. If anything, its importance is likely to increase rather than decrease with the use of information technologies and moves towards knowledge economies (Karran, Citation2009, pp. 277–278). Thus the alarming rates of attacks and threats against university teachers, researchers and students (Free to Think , Citation2020) at a time when autocratisation is surging are raising global concern (Maerz, Lührmann, Hellmeier, Grahn, & Lindberg, Citation2020).

We have looked at the relationship between academic freedom and democracy from another angle, trying to grasp the impact of academic freedom on democracy. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first attempt to investigate empirically the hypothesis that long-standing academic freedom has a positive effect on democratic consolidation. Specifically, our proposal is that respect of academic freedom in the past contributes to the ability and incentives of scholars to disseminate knowledge both directly and through higher education on the form and content of functioning democracy. Furthermore, public awareness, enhanced by scholars taking part in public discussions, supports the accountability of decision making. The emergence and ability of intellectuals to criticise and advise governments, political parties and the general public alike strengthens the democratic competence of the society.

We tackled the issues of the short time frame and highly persistent variables by using the GMM system technique. Even when controlling for country-specific effects, our results show that the null hypothesis holds. The robustness of the results was shown by checking alternative measures of democracy, as well as by checking reverse causality in the sample. Our results reveal that the vitality of academic freedom as a channel to improve the quality of elections is not subject to country-specific effects, such as the dependence on oil, income level and the initial level of democracy.

Our results demonstrate a positive and statistically significant relationship between academic freedom and the level of democracy. The likelihood of a government to implement and sustain democracy is higher the stronger its respect for academic freedom has been. Conversely, it is lack of academic freedom, or academic acquiescence, which explains the persistence of authoritarian rule in spite of increasing levels of education, including higher education. The Chinese one-party state is a prominent example (Perry, Citation2020), but there are also multiparty systems with low levels of democracy and high investments in education and research. Within Africa, Rwanda is a case in point (Schendel, Mazimhaka, & Ezeanya, Citation2013, see Figures A2–5). However, as academia itself is a global domain and international mobility an important ingredient of academic excellence (Laakso, Citation2020b), in the long run investing in academic excellence is likely to be a risk for undemocratic rulers.

Our findings that intellectuals are important catalysers for democratic consolidation contribute to the literature addressing the role of education and past developments in the implementation of peaceful political competition. They also corroborate Lipset’s notion: ‘If we cannot say that a “high” level of education is a sufficient condition for democracy, the available evidence does suggest that it comes close to being a necessary condition in the modern world’ (Citation1959, p. 80). Overall, the robust impact of academic freedom on democracy found in this paper suggests that future research has to test other channels through which higher education influences political systems. The scarcity of theoretical background and the unavailability of accurate data are challenges for further work.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (504.7 KB)Acknowledgements

This article is based on a paper presented at the conference “The Political Science Discipline in Africa: freedom, relevance, impact” on Oct 31-2 November 2019 in Accra, jointly organized by the Nordic Africa Institute (NAI), Association of African Universities (AAU) and Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa (CODESRIA) and published in the V-Dem website Users’ Working Papers series No. 33, June 2020. We want to thank the conference participants for comments. We are grateful to Staffan I. Lindberg and Johannes von Römer for valuable suggestions and assistance with V-Dem data, to Nely Keinänen for checking the language and two anonymous reviewers whose advice helped us to clarify our argument in a fundamental way. On request, we can provide data and available code to bona fide researchers.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplementary Materials are available for this article which can be accessed via the online version of this journal available at https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2021.1988080

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abdel Latif, M. M. M. (2014). Academic freedom: Problems in conceptualization and research. Higher Education Research & Development, 33(2), 399–401.

- Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., Robinson, J. A., & Yared, P. (2005). From education to democracy? American Economic Review, 95(2), 44–49.

- Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., Robinson, J. A., & Yared, P. (2008). Income and democracy. American Economic Review, 98(3), 808–842.

- Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., & Robinson, J. A. (2001). The colonial origins of comparative development: An empirical investigation. American Economic Review, 91(5), 1369–1401.

- Aidt, T. S., & Leon, G. (2016). The democratic window of opportunity: Evidence from riots in Sub-Saharan Africa. The Journal of Conflict Resolution, 60(4), 694–717.

- Ake, C. (2000). The feasibility of democracy in Africa. Codesria: African Books Collective [distributor].

- Alemán, E., & Kim, Y. (2015). The democratizing effect of education. Research & Politics, 2(4), 1–7.

- Anyanwu, J. C., & Erhijakpor, A. E. O. (2014). Does oil wealth affect democracy in Africa? African Development Review, 26(1), 15–37.

- Apergis, N. (2018). Education and democracy: New evidence from 161 countries. Economic Modelling, 71, 59–67.

- Appiagyei-Atua, K., Beiter, K., & Karran, T. (2016). A review of academic freedom in Africa through the prism of the UNESCO’s 1997 recommendation. Journal of Higher Education in Africa/Revue de l’enseignement Supérieur En Afrique, 14(1), 85–117.

- Arellano, M., & Bond, S. (1991). Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. The Review of Economic Studies, 58(2), 277–297.

- Arezki, R., & Gylfason, T. (2013). Resource rents, democracy, corruption and conflict: Evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of African Economies, 22(4), 552–569.

- Bjorvatn, K., & Farzanegan, M. R. (2015). Resource rents, balance of power, and political stability. Journal of Peace Research, 52(6), 758–773.

- Blundell, R., & Bond, S. (1998). Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics, 87(1), 115–143.

- Bratton, M., & Chang, E. C. C. (2006). State building and democratization in Sub-Saharan Africa: Forwards, backwards, or together? Comparative Political Studies, 39(9), 1059–1083.

- Bratton, M., & Van de Walle, N. (1997). Democratic experiments in Africa: Regime transitions in comparative perspective. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Brücker, H., Capuano, S., & Marfouk, K. (2013). Education, gender and international migration: Insights from a panel-dataset 1980-2010 | Institute for Employment Studies (IES). Institute for Employment Research (IAB). Retrieved from http://www.employment-studies.co.uk/resource/education-gender-and-international-migration-insights-panel-dataset-1980-2010

- Brückner, M., & Ciccone, A. (2011). Rain and the democratic window of opportunity. Econometrica, 79, 923–947.

- Bryden, J., & Mittenzwei, K. (2013). Academic freedom, democracy and the public policy process. Sociologia Ruralis, 53(3), 311–330.

- Burchard, S. M. (2015). Electoral violence in sub-Saharan Africa: Causes and consequences. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner.

- Castelló-Climent, A. (2008). On the distribution of education and democracy. Journal of Development Economics, 87(2), 179–190.

- Cheeseman, N., & Klaas, B. (2018). How to rig an election. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Cole, J. R. (2017). Academic freedom as an indicator of a liberal democracy. Globalizations, 14(6), 862–868.

- Coppedge, M., John, G., Carl H. K., Staffan I. L., Jan, T., David, A., Michael, B., Agnes, C., M. Steven, F., Lisa, G., Haakon, G., Adam, G., Allen, H., Anna, L., Seraphine, F. M., Kyle L. M., Kelly, M., Valeriya, M., Pamela, P., … Daniel Ziblatt. (2021). ‘V-Dem Codebook v11.1 Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project.’

- Coulibaly, D., & Omgba, L. D. (2021). Why are some African countries succeeding in their democratic transitions while others are failing? Oxford Economic Papers, 73(1), 151–177.

- Cowen, M., & Laakso, L. (1997). An overview of election studies in Africa. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 35(4), 717–744.

- Cranenburgh, O. (2009). Restraining executive power in Africa: Horizontal accountability in Africa’s hybrid regimes. South African Journal of International Affairs, 16(1), 49–68.

- Dahl, R. A. (1971). Polyarchy: Participation and opposition. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Dahl, R. A. (1989). Democracy and its critics. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Daly, T. G. (2019). Democratic decay: Conceptualising an emerging research field. Hague Journal on the Rule of Law, 11(1), 9–36.

- Diouf, M. (1994). The Intelligetsia in the democratic transition. In M. Mamdani & M. Diouf (Eds.), Academic freedom in Africa (pp. 327–336). Dakar: CODESRIA.

- Docquier, F., Lodigiani, E., Rapoport, H., & Schiff, M. (2016). Emigration and democracy. Journal of Development Economics, 120, 209–223.

- Evans, G., & Rose, P. (2012). Understanding Education’s influence on support for democracy in Sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Development Studies, 48(4), 498–515.

- Free to Think 2020. (2020). Scholars at risk. Retrieved October 13 2021, from https://www.scholarsatrisk.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Scholars-at-Risk-Free-to-Think-2020.pdf

- Glaeser, E. L., Ponzetto, G. A. M., & Shleifer, A. (2007). Why does democracy need education? Journal of Economic Growth, 12(2), 77–99.

- Griliches, Z., & Hausman, J. A. (1986). Errors in variables in panel data. Journal of Econometrics, 31(1), 93–118.

- Grimm, J., & Saliba, I. (2017). Free research in fearful times: Conceptualizing an index to monitor academic freedom. Interdisciplinary Political Studies, 3, 42–75.

- Hauk, W. R., & Wacziarg, R. (2009). A Monte Carlo study of growth regressions. Journal of Economic Growth, 14(2), 103–147.

- Higgins, J. (2014). Academic freedom in a democratic South Africa: Essays and interviews on higher education and the humanities. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Jensen, N., & Wantchekon, L. (2004). Resource Wealth and Political Regimes in Africa. Comparative Political Studies, 37(7), 816–841.

- Karran, T. (2009). Academic freedom: In justification of a universal ideal. Studies in Higher Education, 34(3), 263–283.

- Laakso, L. (2020a). ‘Electoral Violence and Political Competition in Africa.’ In The Oxford Encyclopedia of African Politics, ed. Nic Cheeseman, 552–563. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Laakso, L. (2020b). Academic mobility as freedom in Africa. Politikon, 47(4), 442–459.

- Linke, A. M., Schutte, S., & Buhaug, H. (2015). Population attitudes and the spread of political violence in Sub-Saharan Africa. International Studies Review, 17(1), 26–45.

- Lipset, S. M. (1959). Some social requisites of democracy: Economic development and political legitimacy. The American Political Science Review, 53(1), 69–105.

- Lynch, G., & Crawford, G. (2011). Democratization in Africa 1990–2010: An assessment. Democratization, 18(2), 275–310.

- Maerz, S. F., Lührmann, A., Hellmeier, S., Grahn, S., & Lindberg, S. I. (2020). State of the world 2019: Autocratization surges – Resistance grows. Democratization, 27(6), 909–927.

- Mama, A. (2006). Towards academic freedom for Africa in the 21st Century. Journal of Higher Education in Africa/Revue de l’enseignement Supérieur En Afrique, 4(3), 1–32.

- Marshall, M. G., Gurr, T. R., & Jaggers, K. (2019). Polity IV project: Dataset users’ manual. Vienna, Va: Center for Systemic Peace. Retrieved October 14, 2021, from http://www.systemicpeace.org/inscr/p4manualv2018.pdf Value

- Matambo, E. (2020). A choreographed Sinophobia? An analysis of China’s identity from the perspective of Zambia’s Patriotic Front. Africa Review, 12(1), 92–112.

- McFerson, H. M. (2010). Extractive industries and African democracy: Can the “resource curse” be exorcised? International Studies Perspectives, 11(4), 335–353.

- Mercier, M. (2016). The return of the prodigy son: Do return migrants make better leaders? Journal of Development Economics, 122, 76–91.

- Mkandawire, T. (2005). African intellectuals and nationalism. In T. Mkandawire (Ed.), African intellectuals: Rethinking politics, language, gender and development (pp. 10–55). London: Zed Books in association with CODESRIA.

- Murove, M., & Chitando, E. (2018). Academic freedom and the problems of patriotism and social responsibility in Post-colonial Africa. Alternation Journal, (23), 326–345. Retrieved from https://ojstest.ukzn.ac.za/index.php/soa/article/view/1252.

- Ojok, D., & Achol, T. (2017). Connecting the dots: Youth political participation and electoral violence in Africa. Journal of African Democracy and Development, 1(2), 94–108.

- Omgba, L. D. (2009). On the duration of political power in Africa: The role of oil rents. Comparative Political Studies, 42(3), 416–436.

- Oyugi, W. O. (Ed.). (1989). The Teaching and research of political science in Eastern Africa. Addis Ababa: Organization for Social Science Research in Eastern Africa.

- Peiffer, C., & Englebert, P. (2012). Extraversion, vulnerability to donors, and political liberalization in Africa. African Affairs, 111(444), 355–378.

- Perry, E. J. (2020). Educated acquiescence: How academia sustains authoritarianism in China. Theory and Society, 49(1), 1–22. Retrieved from https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-019-09373-1

- Post, R. C. (2012). Democracy, expertise, and academic freedom: A first amendment jurisprudence for the modern state. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Rakner, L. (2017). Tax bargains in unlikely places: The politics of Zambian mining taxes. The Extractive Industries and Society, 4(3), 525–538.

- Reyntjens, F. (2020). Respecting and circumventing presidential term limits in sub-Saharan Africa: A comparative survey. African Affairs, 119(475), 275–295.

- Ross, M. L. (2001). Does oil hinder democracy? World Politics, 53(3), 325–361.

- Said, E. W. (1994). Representations of the intellectual: The 1993 Reith Lectures. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Sargan, J. D. (1958). The estimation of economic relationships using instrumental variables. Econometrica, 26(3), 393–415.

- Sater, J. N. (2009). Reforming the Rule of Law in Morocco: Multiple Meanings and Problematic Realities. Mediterranean Politics, 14(2), 181–193.

- Schedler, A. (1998). What is democratic consolidation? Journal of Democracy, 9(2), 91–107.

- Schendel, R., Mazimhaka, J., & Ezeanya, C. (2013). Higher education for development in Rwanda. International Higher Education, (70), 19–21.

- Söderberg Kovacs, M., & Bjarnesen, J. (2018). Violence in African elections: Between democracy and big man politics. London: Zed Books.

- Spannagel, J., Kinzelbach, K., & Saliba, I. (2020). The academic freedom index and other new indicators relating to academic space: An introduction. The Varieties of Democracy Institute (Users Working Paper Series 26).

- Teorell, J., Coppedge, M., Lindberg, S., & Skaaning, S.-E. (2019). Measuring polyarchy across the globe, 1900–2017. Studies in Comparative International Development, 54(1), 71–95. Retrieved from https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-018-9268-z

- Valero, A., & Van Reenen, J. (2019). The economic impact of universities: Evidence from across the globe. Economics of Education Review, 68, 53–67.

- Van Cranenburgh, O. (2008). ‘Big Men’ rule: Presidential power, regime type and democracy in 30 African countries. Democratization, 15(5), 952–973.

- Wantchékon, L., & García-Ponce, O. (2013). Critical junctures: Independence movements and democracy in Africa. Competitive Advantage in the Global Economy (CAGE), 173. Retrieved from https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:cge:wacage:173

- White, G. (1997). The advent of electoral democracy in Morocco? The referendum of 1996. The Middle East Journal, 51, 389–404.

- World Bank. (2020). https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators

Appendix

Table A1. Data definition and source

Table A2. Democracy transition in Africa

Correlation matrix between Academic freedom and alternative index of democracy

List of countries