?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The potential socioeconomic benefits of remittances remain untapped as a large portion of remittances is transferred through informal channels worldwide. In this paper, we explored the effect of the financial sector development in the home country on the preference for informal remittance channels using a nationally representative household dataset from Bangladesh along with subdistrict level data on bank branches. However, the identification of the effect of the banking network on the choice of remittance channel is challenging due to the unobserved heterogeneity problem. We circumvent this problem by using an instrumental variable (IV) approach. We found that greater accessibility to the banking network at the subdistrict level significantly reduces the use of the informal remittance transfer channels: a 10% increase in the availability of the total number of bank branches reduces the probability of using the informal channels, at least once, by 1.79% and hundi by 2.3% on average. The results are consistent and robust across different specifications and estimation methods. The main policy implication of this result is that the expansion of bank branches can enhance the inflows of remittances through formal channels and thereby can magnify the macroeconomic benefits of remittances globally.

1. Introduction

Globally, the inflows of officially recorded remittances have increased remarkably from $126 billion in 2000 to $717 billion in 2019 (Marie & Binod, Citation2020). However, the officially recorded figures significantly underestimate the actual size of the remittances because a large portion of the remittances is transferred through informal channels. Although there is no specific record of the number of remittances that are transferred through informal channels, different model-based estimates and household surveys in developing countries suggest that the unrecorded or informal inflows of remittances range from 10 to 50% (or more) of the official inflows (Maimbo, El Qorchi, & Wilson, Citation2003; Puri, Ritzema, et al., Citation1999; Ratha, Citation2003; Schiantarelli, Citation2005). Focusing on cross-country data, they mentioned that remittance transaction costs are the main factors for choosing informal channels. Transaction costs of remittance transfer depend on the level of financial development in the home country and the volatility of exchange rates (Freund & Spatafora, Citation2008).

Studies revealed that financial development in the home country affects migrants’ decision to remit (Mookerjee & Roberts, Citation2011; Niimi & Ozden, Citation2006) and the aggregate inflows of workers’ remittances through the banking channel (Barua & Rafiq, Citation2020; Bettin, Lucchetti, & Zazzaro, Citation2012) by increasing trust in the financial sector of the home country and by lowering transaction costs (Freund & Spatafora, Citation2008). However, how financial sector development in the home country affects an individual migrant’s choice of remittance channels remains unexplored in the literature. In particular, to the best of our knowledge, how financial sector development in the form of greater availability of bank branch networks influences the decision of a migrant worker in choosing a particular remittance channel has not been investigated in any of the earlier studies. This study fills this gap by examining the effects of the availability of bank branches in a locality on the use of remittance channels by international migrants.

In this paper, using household survey data from Bangladesh, we examined whether greater access to banking networks in a particular Upazila (i.e. sub-district) reduces the use of informal remittance transfer channels among the migrants who send remittances to their family members living in that Upazila. However, the identification of such a relationship is not free from endogeneity concerns, as the location choice of banks may be influenced by unobserved factors that can also affect the remitting behavior of migrants. To circumvent this problem, we used an instrumental variable (IV) strategy, which allows us to identify the causal effect of financial sector development on the choice of remittance channels.

This study contributes in at least three important ways. First, this is the first study that examines the effects of financial sector development in the recipient country on the choice of remittance channels by individual migrants. Previously, Amuedo-dorantes, Bansak, and Pozo (Citation2005) and Anneke and Robert (Citation2014) analyzed the determinants of migrants’ choice of channels from the host or sending country perspective using micro data. Second, as mentioned above, we used the IV approach to identify the effects of financial sector development on the choice of remittance transfer channels, whereas both of the previous studies (Amuedo-dorantes et al., Citation2005; Anneke & Robert, Citation2014) used the multinomial logit (MNL) model to identify the factors behind the choice of channels. Third, an understanding of the behavior of remittance senders, receivers, and receiving households along with the role of banking networks in choosing remittance-sending channels will help policymakers to formulate effective policies for encouraging the inflows of remittances through formal channels in a sustainable way globally.

The importance of remittances for the Bangladesh economy and the dynamics of financial development in the country provide us with an interesting setup to investigate the effect of the availability of bank branches on the choice of informal remittance channels. The officially recorded inflows of remittances in Bangladesh have grown significantly from USD 11.04 billion in 2010 to USD 21.75 billion in 2020 (Bureau of Manpower, Employment and Training (BMET), July Citation2021). Remittances play a vital role in the economic growth and development of Bangladesh and are the second-largest external source of foreign earnings after exports. In 2020, the inflows of remittances as a percentage of GDP was 6.5%, as a percentage of export earnings was 54.1% and as a percentage of import payments was 36.0%. The World Bank Migration and Development Brief 2020 ranked Bangladesh as the third-highest remittance receiver country in the south Asian region and as the eighth largest remittance recipient country in the world (Migration & Development Brief 34, May 2021).

In Bangladesh, a large portion of workers migrate from rural areas and send remittances to their families living in rural areas using both formal and informal channels. A study conducted by Siddiqui and Abrar (Citation2001) on Bangladeshi migrants in the UAE showed that approximately 54% of remittances are sent through informal channels. However, the share of remittances transferred through informal channels has been decreasing over time. According to the 2016 Survey on Investment from Remittances (SIR) prepared by the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS), approximately 22% of the total remittances was transferred through informal channels.

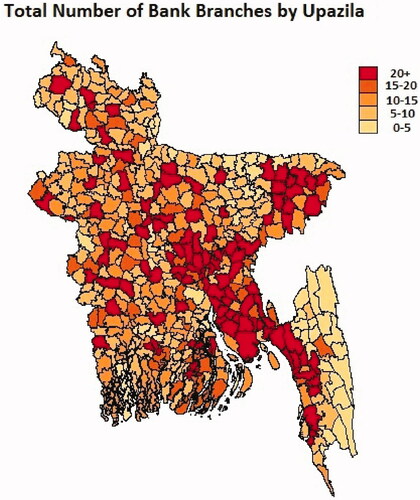

One of the possible factors behind the declining share of informal channels is the rapid expansion of the banking network in Bangladesh induced by regulatory initiatives taken by the Bangladesh Bank. In addition, incentives provided by the banks and the government along with the legal actions initiated by the latter stimulated the inflows of official remittances. Some of the main stimulus include tax exemption, cash incentives, paperwork easing, providing the highest remitter recognition award, and introducing digital and faster services. Additionally, banks have been rapidly expanding their footing in rural and urban areas due to the (urban:rural) 1:1 branch opening policy initiated by Bangladesh Bank in 2011 from its earlier 4:1 policy in 2006. The number of branches of scheduled banks increased from 7658 in 2010 to 9654 in 2016. In rural areas, the number of branches increased by 24 percent, and in urban areas, the number increased by 24 percent over the same period (Bangladesh Bank, Annual Report, July 2019-June 2020). The question that follows from the above discussion is whether such expansion of the banking network led to a change in the remitting behavior of international migrants.

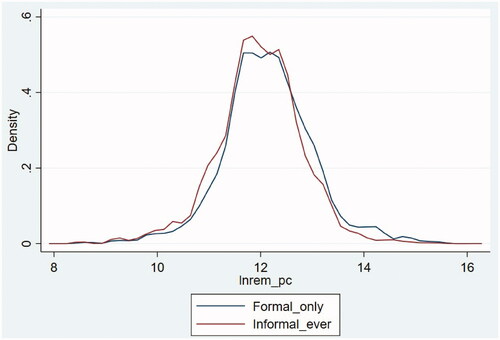

To explore the effects of bank branch networks on migrants’ choice of remittance channels, we used nationally representative household-level survey data from Bangladesh, titled the Survey on Investment from Remittances 2016 (hereafter, SIR 2016). We organized our analysis in two stages. First, we explored the determinants of inflows of remittances, particularly the relationship between the number of remittances and remittance transfer channels, controlling for other covariates. We found that the migrants who used at least one of the informal channels during the last year of the survey sent on average 4.8% more remittances than the migrants who used only formal channels for transferring remittances. We also found that the migrants who choose hundi at least once sent on average 10% more remittances per year compared to the migrants who did not use hundi. Both of the results are statistically significant at the 1% level.

Second, we estimated the effect of financial sector development on migrants’ preference for sending money through informal channels. In our estimation, we preliminarily used four binary outcome indicators to represent different combinations of informal remittance channels. As the measure of financial sector development, we used the total number of bank branches at each Upazila. Analyzing the impact of banking networks on informality faces the challenge of endogeneity problems that emanate from unobserved confounders (e.g. local-level economic development) simultaneously affecting both the location choice of banks and the remitters preference for transfer channels. To address this issue, we used the fraction of establishments (firms) using natural gas for production purposes in the Upazila, a proxy for the availability of natural gas, as an instrumental variable (IV) for the number of bank branches in a particular Upazila. We estimated different specifications of the model using the two-stage least square (2SLS) estimation method with robust standard errors in our analysis.

The 2SLS estimation results showed that the bank branch network can significantly reduce the use of informal channels. In particular, for a 10% increase in the total number of bank branches in a particular Upazila, the probability of using at least one informal channel is decreased by 1.79% on average. A 10% increase in the total number of bank branches reduces the likelihood of choosing only informal channels by 0.61% on average. The probability of using only hundi for sending remittances is decreased by 0.5% on average for a 10% increase in the total number of bank branches in a particular Upazila.

We estimated the model with various specifications of the models with different sets of control variables. In addition, we estimated different specifications of the model using the” ivprobit” estimation method. All the estimated coefficients of our main interest variable, the bank branch network, in different specifications of the model, show an expected negative effect on the choice of informal channel for sending remittances. The results remain consistent and robust with our main findings and are statistically significant at the 1% level.

We further checked the robustness of our estimation examining whether the banking network increases the choice of banks and formal channels for sending remittances. We found that for a 10% increase in the total number of bank branches, the probability of using banks as the most preferred channel increases by 1.8%, and the probability of using formal channels as the most preferred option increases by 10.2%. We also found a meaningful relationship between preference for informal channels and the characteristics of the receivers, the recipient households, and the remitters.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 discusses the data and provides summary statistics for the main variables. Section 3 presents the empirical strategy of our estimation. Section 4 presents the estimation results and discusses the major findings. Finally, Section 5 draws conclusions and makes policy recommendations.

2. Data

To investigate the effect of the bank branch network on the choice of remittance-sending channel, we combined Upazila (sub-district)-level data on the availability of banks with household-level microdata from a nationally representative survey titled “Survey on Investment from Remittance, 2016,” implemented by the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS), the apex body of the National Statistics. The survey covers 63 out of 64 districts located in eight administrative divisions in Bangladesh. The survey used a two-stage stratified random sampling technique where villages were selected from each division at the first stage and the remittance-receiving households were selected from each village in the second stage. The final sample includes 10452 remittance-receiving households (RRHHs) from 377 Upazilas located in 63 districts.

The survey reports the number of remittances (in-kind and in-cash) received by the households during the last one year of the survey. Although the total amount of remittances transferred was reported only at the household level, the rank of preferences for formal and informal channels for sending remittances was reported for each remittance sender of the household. The data set also contains some key characteristics of the remittance senders and the principal remittance receiver of each household. Our sample includes households that reported both the number of cash remittances and the transaction channels used by the senders and for which data are available for the variables representing the basic characteristics. Based on these criteria, the final sample includes the data on 11581 migrant workers from 10127 remittance recipient households located in 369 Upazilas. The descriptive and regression analyses of the paper are based on this final sample.

In the SIR 2016, as mentioned above, we can identify the preference for transfer channels used by the migrants for sending remittances to the home country during the last year of the survey. We defined the choice of channels in different ways which are presented in . The table shows that 24% of the migrants used at least one informal channel for sending remittances and 14% of the migrants used hundi at least once for sending remittances from the host country to the home country. Further, 89% of the migrants used formal channels as the most preferred channel for sending remittances.

Table 1. Description of the channels used in the analysis

presents some basic characteristics of the remittance senders (11581), principal remittance receivers (10127) and remittance recipient households (10127). In the sample, approximately 95% of the remittance-receiving households were located in rural areas. On average, the sample households consisted of five members and owned 119 decimal land. In the sample of households, most of the remittance senders were male (96%) and were married (71%). The remitters were 34 years old on average, and 27% of them had completed higher secondary or above education levels. Most of the migrants were working as laborers (64%), followed by salaried workers (27%), other elementary workers including house workers, part-time workers, students and others (5%) and business owners (4%). Among the migrants, only 15% had received training before their departure from their home country (Bangladesh), and 13% of them had migrated unofficially. The average duration of their stay in the host country was approximately 7 years.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of the basic characteristics of the remittance senders, principal remittance receivers, and remittance recipient households

The characteristics of principal remittance receivers show that 50% of them were female, most of them were married (89%) and aged approximately 34 years on average. Approximately 18% of the receivers completed secondary or higher levels of education. In terms of their relationships with the remittance senders, 34% of the receivers were reported as spouses of the senders, and the rest were recorded as parents or other relatives.

Our main variable of interest is the total number of bank branches in each Upazila. We collected Upazila-level bank branch data from the Statistics Department of Bangladesh Bank. Since the data for SIR 2016 were collected during 2016, we used the information on banks for December 2015. As of December 2015, there were on average 16 bank branches in 369 sample Upazilas. The distribution of the total number of bank branches across the Upazilas is presented in . These Upazila-wise data were merged with household survey data using geographical codes provided by the BBS.

2.1. Stylized facts

shows the kernel density plots of the inflows of remittances for the households where remitters used only formal channels (formal only) and the households where remitters used at least one informal channel (informal ever). The figure depicts that the average inflows of remittances were higher for migrants who chose at least one informal channel for sending remittances than for those who chose only formal channels.

The summary statistics of the inflows of yearly average remittances per migrant (in ’000 BDT) by selected characteristics of the senders and regions are presented in in Appendix. The average amount of remittances per migrant transferred through formal channels only is approximately BDT 224.19 thousand (equivalent to USD 2870), which is 12% lower than that of the remitters who used at least one informal channel (BDT 251.61 thousand or USD 3207). The average inflows of remittances per migrant increase with the education level of the migrants and are the highest for the migrants with secondary education or a higher level of education. In terms of occupation, migrants who had their own business in the host country transferred significantly higher amounts of remittances on average than the migrants of other occupations, such as salaried workers, laborers, and other elementary works. Moreover, migrants who received training in the home country before departure transferred (BDT 267.49 thousand) more than those without such training (BDT 224.51 thousand). Additionally, the remitters who migrated officially sent more remittances (BDT 231.72 thousand) than their unofficial counterparts (BDT 224.72 thousand). We further explored the relationship between remittances and these variables in our empirical analysis.

3. Empirical strategy

3.1. Inflows of remittances

Consider that a migrant i sends remittances from the host country to her household h located in Upazila j in the home country using any of the formal and/or informal channels. In the first part of the analysis, we investigated the relationship between the inflows of worker remittances per migrant and the channels of sending remittances using the following regression model:

(1)

(1)

where lnRemihj indicates the log of remittances per migrant sent by migrant i to the recipient of household h located in Upazila j. InfChannelihj is an indicator of informal channel usage for the transfer of remittances. In terms of the use of informal means, we used different measures of informality, as described in .

To control for other determinants of remittances, we included a set of characteristics of the remittance senders (), the principal remittance receivers (

) and the remittance recipient households (

).

includes the log of household size, the log of the land area owned by the households, and a household location dummy.

includes the migrant’s gender dummy, a marital status dummy, the log of age, the square of the log of age, an education dummy, relationship with the household head dummy, a set of occupation dummies, a pre-training dummy, an unofficial migration dummy, and the log of the duration of living in the host country.

consists of a gender dummy, a marital status dummy, the log of age, the square of the log of age, and an education dummy. The rationale for including these control variables follows the standard literature on migration and remittances. The detailed explanation along with the descriptive statistics of the control variables are described in . Additionally, a set of division dummies DD and country dummies CD are included in the estimation of our models to capture the regional and country heterogeneity.

3.2. Choice of remittance-sending channels

Generally, migrants use either formal or informal channels or both types of channels to send remittances to receivers in the home country. Consider that migrant i derives utility Uic from choosing channel c for transferring remittances. Utility derived from a particular channel depends on a set of factors, including characteristics of the remitters, receivers, and recipient households; transaction costs; and availability of banking facilities.

In general, transaction costs of remittances have two main components: the fees for transferring money (or service fees) and the spread of the exchange rate. One of the most important determinants of transaction costs is the level of financial development in the home country (Freund & Spatafora, Citation2008). The lack of access to banking services on the receivers’ end increases the transaction costs of remittances. Again, the higher the distance between the bank and the receiver is, the higher the costs of receiving remittances. This distance will also reduce the attractiveness of financial services offered by commercial banks. Therefore, the higher the number of commercial banks in a particular locality is, the lower the transaction costs and the higher the utility derived from selecting banking channels for sending remittances.

Let the utility function be

(2)

(2)

where Vic is the deterministic component,

is a coefficient vector and ϵic is the stochastic component of the utility function. The probability of selecting a particular channel increases with its utility. Therefore, migrant i chooses channel c if its associated utility Uic is greater than that of channel k, Uik, where

Based on the above framework, our primary econometric model is the following:

(3)

(3)

EquationEquation (3)(3)

(3) includes the supply and the demand side factors that can influence the choice of remittance sending channels. From the supply-side perspective, our main variable of interest is

which represents the log of the total number of bank branches in Upazila j. The main coefficient of interest β indicates how the availability of banking networks affects the choice of remittance channels. The expected sign of the coefficient on

β, is negative, indicating that the higher the availability of bank branches, the lower the use of informal channels. In other words, the probability of using formal channels increases (i.e. informal channel decreases) with the expansion of bank branches as the latter leads to a reduction in the transaction costs associated with remittance transfer (Freund & Spatafora, Citation2008). In order to control for other supply-side factors such as regional infrastructure, we included a rural dummy and a set of division fixed effects, DD. Similarly, to control for host country-specific supply-side factors (e.g. financial infrastructure), we included a set of host-country-specific dummy variables, CD in EquationEquation (3)

(3)

(3) .

From the demand-side perspective, to control the factors that can influence the demand for selecting formal or informal channels, in EquationEquation (3)(3)

(3) , we added a set of characteristics of the remittance recipient households (

), a set of characteristics of the remittance senders (

) and a set of characteristics of the principal remittance receivers (

) of the households. The variables included in each of these vectors have been discussed in EquationEquation (1)

(1)

(1) and in . Similar variables are also used in earlier studies to control for other determinants of remittance channels (Anneke & Robert, Citation2014; Siegel & Lücke, Citation2013). We hypothesize that the demand for using informal channels will be lower among the richer households, that is the probability of selecting informal channels is expected to be negatively correlated with the amount of land owned by the households. Similarly, we expect that the preference for selecting informal channels will be lower among the remitters with higher educational qualifications and those who are involved in higher income-generating occupations such as business. On the other hand, we can also hypothesize that the use of informal channels is likely to be higher among the unofficially migrated individuals due to lack of proper documentation and among the migrants without any pre-departure training due to lack of required financial literacy to utilize the official channels.

Even though we controlled for individual demographic characteristics, migration patterns, host country fixed effects and division fixed effects in our model, there are still reasons to worry about the coefficient of in the OLS estimation. Estimating the model using the OLS method may lead to a biased estimate of β since the bank branches are endogenous. The estimates are likely to be biased due to unobserved heterogeneity, which may affect both

and InfChannelihj simultaneously. Unobserved local-level characteristics such as migration patterns, cultural preferences, and preferences of bank managers may simultaneously affect both migrants’ choice of channels and the location choice of banks. Hence, β becomes biased and inconsistent. However, the direction of the bias was not clear.

3.3. Instrumental variables (IV) estimation

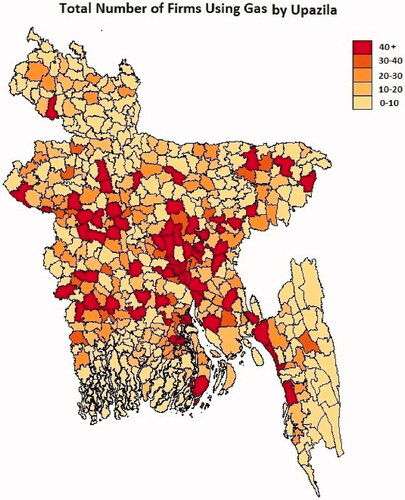

To estimate the causal effect of the bank branches on the choice of remittance channels, we addressed the unobserved heterogeneity problem by implementing the IV approach in our analysis. We used a proxy measure for local-level industrial infrastructure as an instrument for ln(Branches). More specifically, we used the fraction of firms using natural gas for production purposes as an indicator of the availability of natural gas at the Upazila level.

The idea behind using this variable as a proxy for local-level industrial infrastructure is that the usage of natural gas at the firm level generally depends on the uninterrupted supply of gas for production purposes in that Upazila or locality. Since such a level of supply is possible only through gas pipelines, firms located in Upazilas without the availability of gas pipelines are less likely to use gas for production purposes. Therefore, the fraction of firms using gas in a particular Upazila is a reasonable proxy for industrial development in that area. We used this as an instrument based on the understanding that Upazila-level industrial infrastructure is a key determinant of establishing a bank branch in that location. In the discussion that follows, we provide economic explanations to justify that our instrument satisfies the relevance and exclusion restriction criteria of a valid instrument as discussed in Angrist and Pischke (Citation2008).

Based on the existing literature on the determinants of bank branch location choice and industrial agglomeration, we argue that our instrument that represents local industrial infrastructure has a positive impact on the location decision of banks. The first strand of literature incorporates the trade potential of a particular region as one of the important criteria for location choice decision of banks, where the trade potential of a region is measured by the number of firms and industrial zones in a particular locality (Cabello, Citation2019; Cinar & Ahiska, Citation2010; Min, Citation1989). The second group of studies, focusing on the geography of industrial concentration, suggests that the availability of industrial infrastructure and natural resources (i.e. gas, water, electricity) have a positive impact on the concentration of manufacturing industries and thereby on regional industrial development (Crafts & Mulatu, Citation2006; Domenech, Citation2008; Ellison & Glaeser, Citation1999).

As discussed above, our instrument depends on the availability of gas pipelines in the region, and the latter depends on the proximity of the region to the natural gas fields. The presence of gas fields in a locality is a natural phenomenon (Liang, Ryvak, Sayeed, & Zhao, Citation2012). Since proximity to a natural gas field is the primary determinant of the availability of gas transmission pipelines in a particular Upazila, our instrument can be assumed to be independent of the choice of channels, conditional on observed covariates. Again, as the choice of channels depends on the availability of banking networks and the availability of gas cannot influence the use of remittance channels without developing the banking network, we can conclude that our instrument has no direct effect on the choice of remittance channel other than through the banking network. Therefore, following Angrist and Pischke (Citation2008), we can argue that our instrument satisfies both relevance and exclusion restriction conditions.

The data on the availability of natural gas for each Upazila (i.e. the fraction of firms using gas for production purposes) are taken from the District Reports of the Economic Census 2013 of the corresponding Upazila. In our sample, the percentage of firms that use natural gas is zero in 25 out of 361 Upazilas. In the Upazilas where the percentage is greater than zero, the ratio varies from 0.01% in the Ramgati Upazila of Noakhali District to 27.18% in the Hizla Upazila of Barisal District in 2013. On average, 1.74% of the firms were using natural gas for production purposes. Khondoker, Wadood, and Barua (Citation2011) mentioned that there is a considerable regional disparity in terms of the availability of natural gas in Bangladesh. The lack of access to natural gas in the northern and southern parts of the country inhibited the growth of the manufacturing sector in those regions, which caused these regions to lag behind the other parts of the country in terms of economic development. The geographical distribution of the uses of gas by Upazilas is presented in .

We used the two-stage least square (2SLS) estimation procedure with robust standard errors for estimating the IV models. In the first stage of the 2SLS procedure, we regressed on the instrument,

to obtain the predicted values of

(4)

(4)

where

stands for the log of the percentage of establishments using natural gas for production purposes. The first stage is estimated using the OLS estimation method.

The second stage regression of the 2SLS procedure is

(5)

(5)

4. Estimation results

We divided our estimation results into two parts. In the first part, we showed the relationship between the inflows of remittances and the choice of remittance channels, controlling for other covariates based on Model Equation(1)(1)

(1) . In the second part, we showed the IV and OLS estimation results to report the effect of the banking network on the choice of remittance channels based on specification Equation(3)

(3)

(3) . As discussed above, using the fraction of firms using natural gas as a measure of local-level industrial development as an IV, we can overcome the endogeneity problem of the bank branch network.

4.1. Determinants of inflows of remittances

This section presents the results of the relationship between the inflows of remittances and the choice of remittance transfer channels. shows the OLS regression results using Equation(1)(1)

(1) , controlling for the characteristics of remittance senders, receivers, and recipient households. The regression also includes a set of division dummies and a set of host country dummies. All the specifications use the log of remittances per migrant as the dependent variable. We report robust standard errors in all regressions to address the heteroskedasticity problem. Columns Equation(1)

(1)

(1) and Equation(2)

(2)

(2) are used

as the main explanatory variable, and columns Equation(3)

(3)

(3) and Equation(4)

(4)

(4) use

as the main explanatory variable. Columns Equation(1)

(1)

(1) and Equation(3)

(3)

(3) use both division dummies and host country dummies, and columns Equation(2)

(2)

(2) and Equation(4)

(4)

(4) include only division dummies.

Table 3. Determinants of the inflows of remittances per migrant

In column Equation(1)(1)

(1) , the results show that the migrants who used at least one of the informal channels during the last year of the survey sent on average 5% more remittances than the migrants who used only formal channels for transferring remittances. Similarly, in column Equation(3)

(3)

(3) , the estimate suggests that the migrants who choose hundi at least once sent on average 10% more remittances per year compared to the migrants who did not use hundi in the last year. Both results are statistically significant at the 1% level. The results are consistent even when we did not include country-fixed effects in our models.

From , we can also see how the inflows of remittances are associated with the characteristics of the migrants, remittance receivers and remittance-receiving households. Columns Equation(1)(1)

(1) and Equation(3)

(3)

(3) show that male migrants send on average 12% more remittances than female migrants. The average inflow of remittances is positively correlated with the age of the migrant and is negatively correlated with its squared term. The migrants send on average 23% more remittances to receivers who are their spouses than to those who are their parents or other relatives, which is in line with the findings of Carling (Citation2008). The occupation of migrants is also an important determinant of the number of remittances transferred by migrants. The migrants who were involved in labor work, salaried work and other elementary works sent on average 34%, 27% and 21% fewer remittances, respectively, than those who were involved in the business. Remittances are also positively correlated with the duration of stay in the host country. A 10% increase in the duration of stay in the host country leads to a 1.8% increase in the number of remittances per migrant. The migrants who received training in the home country before their departure tended to send 10% more remittances on average than those who did not have such training.

From the receiver perspective, the results show that female receivers receive on average 5% more remittances than male receivers. The flow of remittances increases with increasing receiver age and is negatively correlated with its squared term. Among the household characteristics, land size is positively related to the flow of remittances and is statistically significant at the 1% level. Family size also shows a positive relationship with the inflows of remittances, which is significant at the 10% level. From the results, in general, we can say that inflows of remittances are greater in the informal channels. The results remain consistent when we use different sets of controls in the models.

4.2. The choice of remittance transfer channels

To determine the effect of bank branches on the choice of remittance-sending channels, we estimated the model Equation(3)(3)

(3) for each of our main four binary outcome indicators as defined in . reports the first-stage regression results for our 2SLS model. and reports the IV and OLS estimation results for different combinations of explanatory variables. To address the heteroskedasticity problem, we report heteroskedasticity robust standard errors in the IV regression results. We hypothesize that the coefficient of

β is negative; that is, the availability banking network reduces the use of informal remittance channels by reducing the transaction costs of remittances, as discussed in section choice of remittance-sending channels. As we mainly rely on the IV approach to identify the effect of the banking network on the choice of remittance channels, we showed the first-stage results of our 2SLS model to document the sign and relevance of our instrument.

Table 4. First stage results of the 2SLS estimation

Table 5. Regression of preference for informal channels on the availability of bank branches (IV and OLS estimation)

Table 6. Regression of preference for hundi channel on the availability of bank branches (IV and OLS estimation).

The first-stage model Equation(4)(4)

(4) is used

as the dependent variable and

along with other covariates as explanatory variables. The first-stage estimation results for the different specifications of the model are presented in columns (1–5) in . As expected, the first-stage regression results show that the coefficient of our instrumental variable,

is positively correlated with the log of the total number of bank branches. In other words, the Upazilas that have better industrial infrastructure have more bank branches. The estimated coefficient of the instrument is consistent across different specifications of the model and is statistically significant at the 1% level.

A common concern in using the IV approach is the bias caused by the weak instrument problem, as highlighted by Bound, Jaeger, and Baker (Citation1995) and Stock, Wright, and Yogo (Citation2002). We used the Cragg and Donald (Citation1993) F-statistic to test for weak instruments. The Cragg-Donald F-statistic is reported at the bottom of . As the F-statistics clearly exceed the rule of the thumb threshold value of 10, we can reject the null hypothesis of a weak instrument. Therefore, there is no worry of weak instrument bias in our analysis.

4.2.1. Regression results for informal ever and informal only models

Column Equation(1)(1)

(1) of presents the IV results using

as the dependent variable. The estimated coefficient (se) of

−0.179 (0.032), indicates that a 10% increase in the total number of bank branches reduces the probability of using at least one informal channel by 1.79% on average. In other words, the higher the number of bank branches in a particular Upazila, the greater the likelihood of using only formal channels for a remittance transfer. Column Equation(2)

(2)

(2) shows the results using

as the dependent variable. The estimated coefficient, −0.061 (0.018), implies that a 10% increase in the total number of bank branches reduces the likelihood of choosing only the informal channel by 0.61% on average. Both coefficients are statistically significant at the 1% level.

To compare the findings of the IV approach with the standard OLS procedure, in columns Equation(3)(3)

(3) and Equation(4)

(4)

(4) of , we showed OLS results for

and

respectively. The influence of the endogeneity problem is clearly reflected in the OLS estimates. In column Equation(3)

(3)

(3) , the coefficient of

0.005, is positive but very small and statistically insignificant. In column Equation(4)

(4)

(4) , the coefficient of

−0.004, appears to be negative, as in the case of IV, but remains statistically insignificant. Therefore, the OLS estimates are biased, which justifies the use of the IV strategy in our study.

Looking at the sets of control variables, we found that most of the estimated coefficients appear with expected signs and remain consistent across different specifications in columns Equation(1)(1)

(1) and Equation(2)

(2)

(2) of . The coefficient of the log of land size owned by the household is negative and is statistically significant in both columns Equation(1)

(1)

(1) and Equation(2)

(2)

(2) . The results suggest that informality in remittance behavior is negatively correlated with the wealth of households: a 10% increase in land size reduces the probability of transferring money through the informal channel, at least once, by 0.09%, and through only informal channels by 0.12%. The size of the remittance recipient households is found to be uncorrelated with the migrants’ choice of transfer channels.

The characteristics of the remitters also influence the decision of remitters in selecting a transfer channel. The estimated coefficient of the female dummy is negative in all the regressions and is statistically significant at the 1% level. In column Equation(1)(1)

(1) , the corresponding estimate indicates that female senders are 14% less likely on average to choose an informal channel at least once compared to their male counterparts. The coefficient of the married dummy also appears to be negative and statistically significant in 3 out of 4 specifications shown in .

The migrants’ duration of living in the host country also determines the choice of channels. The estimated coefficient of Ln(Duration) is positive in the case of in column Equation(1)

(1)

(1) and negative in the case of

in column Equation(2)

(2)

(2) . One possible reason behind this finding is that some of the migrants switch from the use of only informal channels to both formal and informal channels or only formal channels as their duration of living in the host country increases.

Another interesting finding is that remitters who migrate unofficially are more likely to use informal channels for money transfers. In the case of they are 4.4% more likely to use only informal channels. The result is consistent with the findings of Amuedo-dorantes et al. (Citation2005), where they documented that the lack of immigration documents in the host country increases the probability of choosing informal channels because the use of formal channels usually requires proper documents.

Remittance senders who received training in the home country before their departure to the host country are less likely to use informal channels, but the coefficient is statistically significant at the 10% level only in the case of the model in column Equation(1)

(1)

(1) .

The education level of the senders is also an important determinant of channel choice. The probability of using only informal channels is approximately 1.4% lower for migrants with secondary or higher education levels than for those with less than secondary education. This coefficient is statistically significant at the 5% level. This finding is consistent with Anneke and Robert (Citation2014), who found that education increases the use of formal channels for transferring remittances. However, the corresponding coefficient in column Equation(1)(1)

(1) , for the

regression model, appears to be positive and statistically significant at the 10% level. One reason for the latter could be that the remitters who used both formal and informal channels for sending remittances are also included in the informal ever category.

The occupations of the remittance senders working in the host country also influence their decision to choose the transfer channel. Based on the survey data, the occupations of the migrants were categorized into four groups: business, salaried job, labor work and house work. In regression analysis, business is used as the reference category. The estimated coefficient of the labor work dummy is negative and statistically significant in column Equation(1)(1)

(1) . The coefficient shows that the likelihood of choosing any informal channel at least once is 6.7% lower on average for the migrants who were involved in labor work compared to the base category (i.e. business). The coefficient of labor work becomes positive in column Equation(2)

(2)

(2) for the

model. The latter result suggests that the likelihood of sending money using only informal channels is higher for the labor work category than for business owners. This result remains similar for the migrants involved in salaried job.

4.2.2. Regression results for hundi ever and hundi only models

After confirmation of the IV results that bank branches can significantly reduce the use of informal channels, we focused on one of the most prominent informal channels, hundi. As described earlier, we used two types of dependent variables: and

The IV results are presented in columns Equation(1)

(1)

(1) and Equation(2)

(2)

(2) , and the OLS results are presented in columns Equation(3)

(3)

(3) and Equation(4)

(4)

(4) of .

The estimated coefficient (se) for is −0.237 (0.028) in column Equation(1)

(1)

(1) , which is larger than that of the corresponding model for

reported in column Equation(1)

(1)

(1) of . In contrast, the estimate for the

model in column Equation(2)

(2)

(2) is −0.050 (0.013), which is slightly lower than that of the

model shown in column Equation(2)

(2)

(2) of . This result indicates that the banking network reduces the use of only the Hundi channel by 0.5% on average. Both coefficients are statistically significant at the 1% level. Together, the results suggest that the availability of bank branches in a particular Upazila can reduce the dependence of migrants on hundi-based transfer channels in that locality.

The results on the characteristics of remittance recipient households in remain consistent with those in . The coefficient of Ln(land) is negative and statistically significant at the 1% level in both columns Equation(1)(1)

(1) and Equation(2)

(2)

(2) , indicating a negative relationship between the choice of the hundi channel and the wealth level of the households. Among the senders’ characteristics, female senders are less likely to use hundi at least once than male senders. The coefficient of Ln(Duration) remains negative and statistically significant in the case of

reflecting a negative association between the duration of migrants’ stay and the use of the Hundi channel. However, this relationship is statistically insignificant in the case of the

model.

As in the case of senders having a secondary or higher level of education are less likely to use only hundi channels for sending remittances, which is in line with the findings of Anneke and Robert (Citation2014). Additionally, senders who were involved in labor work and housework are less likely to use hundi at least once than business owners. Senders who were living longer in the host country were more likely to use hundi at least once to send remittances. However, most of the characteristics of the senders are statistically insignificant except the education level of the sender in the case of the

model.

4.3. Robustness

4.3.1. Alternative specifications

We checked the sensitivity of our main results with different specifications by using alternative sets of control variables. The results are presented in in the Appendix. In all specifications, our main conclusions regarding the sign and statistical significance of ln(Branches) remain unchanged in comparison to their corresponding estimates in and .

4.4. ivprobit estimation

As a further robustness check, we estimate the previous models using the ivprobit estimation procedure for all four outcome variables of interest: and

The estimation results and their corresponding marginal effects are presented in and , respectively. The results also remain consistent with our main findings.

4.4.1. Use of formal channels as the dependent variable

In our main analysis, we used four different outcome variables to represent a different form of informal channel usage and found that the availability of bank branches in a particular Upazila can significantly reduce the choice of informal channels for sending remittances. The question that follows from the above findings is whether bank branch networks can significantly increase the use of banks and other formal channels for sending remittances. We used two different dummy variables to indicate the usage of formal channels namely bank and

which are described in 1

The 2SLS estimation results are presented in . Columns Equation(1)(1)

(1) and Equation(2)

(2)

(2) show the IV estimation results, and column Equation(3)

(3)

(3) presents the corresponding first-stage results. The estimated coefficient (se) of ln(Branches), 0.018 (0.006), in column Equation(1)

(1)

(1) shows that for a 10% increase in the total number of bank branches, the probability of using banks as the most preferred channel increases by 1.8%. The estimated coefficient is much larger for the

specification; for a 10% increase in the total number of bank branches in a particular Upazila, the probability of using formal channels as the most preferred option increases by 10.2%. Both coefficients are statistically significant at the 1% level.

Table 7. Regression of preference for formal channels on the availability of bank branches (IV estimation results)

Therefore, we can summarize that our main finding based on the IV estimation results strongly supports our hypothesis that financial sector development in the host country through the expansion of bank branches can reduce the use of informal remittance channels. The results also support the argument of Freund and Spatafora (Citation2008).

5. Conclusions

Inflows of remittances from migrants are at the heart of the relationship between migration and development. There is little doubt that remittances are important intra-family financial inflows for households and one of the main sources of foreign earnings for the economy as a whole and can have important effects on the economic growth and development of the country. Given the enormous importance of these financial flows and their importance for economic development, governments of sending and receiving countries and international organizations (World Bank, UN, etc.) are designing public policies to encourage migrants to use formal channels for transferring remittances. One of the reasons for choosing informal channels is the costs of transactions associated with remittance transfer through formal channels, which can be reduced by strengthening the financial sector.

In this paper, our aim is to determine the effect of the availability of a banking network, an indicator of financial sector development, on the choice of informal remittance-sending channels using micro-level nationally representative household data combined with the Upazila-level availability of bank branches in Bangladesh. Estimating the causal effects of bank branches on the choice of remittance transfer channels has often proven difficult, given that such expansion of bank branches is not randomly assigned and hence endogenous. We attempted to overcome this problem by incorporating the instrumental variable approach and estimating the model using the 2SLS estimation procedure. We found that the instrumental variable correctly captures the expected negative effect of financial sector development on the choice of informal remittance channel.

The findings of this study have several policy implications. To take potential benefits from the inflows of remittances, the government should encourage the expansion of the banking network across the country, especially in rural areas, to bring unbanked people under financial services and provide them with low-cost remittance-related services. Raising awareness through financial education and training can mitigate the use of informal channels for sending and receiving remittances. The government can provide pre-departure training to migrants and financial education to remittance recipients and should take the necessary steps to prevent unofficial migration.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Amuedo-dorantes, C., Bansak, C., & Pozo, S. (2005). On the remitting patterns of immigrants. Federal Reserve Bank Atlanta Economic Review, 90(1), 37–59.

- Angrist, J. D., & Pischke, J.-S. (2008). Instrumental variables in action: Sometimes you get what you need. In Mostly Harmless Econometrics (pp. 113–220). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Anneke, K., & Robert, V. (2014). Migrants’ choice of remittance channel: Do general payment habits play a role? World Development, 62, 213–227.

- Bangladesh Bank, Annual Report. (July 2019 – June 2020). https://www.bb.org.bd/pub/annual/anreport/ar1920/full_2019_2020.pdf.

- Barua, S., & Rafiq, F. (2020). Macroeconomic determinants of remittances and implications for economic growth: Evidence from Bangladesh. In Bangladesh’s Macroeconomic Policy (pp. 371–392). Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore: Springer.

- Bettin, G., Lucchetti, R., & Zazzaro, A. (2012). Endogeneity and sample selection in a model for remittances. Journal Development Economics, 99 (2), 370–384. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2012.05.001

- Bound, J., Jaeger, D. A., & Baker, R. M. (1995). Problems with instrumental variables estimation when the correlation between the instruments and the endogenous explanatory variable is weak. Journal of the American statistical association, 90(430), 443–450.

- Bureau of manpower, employment and training (bmet). (July 2021). Reterived July 30, 2021, from http://www.old.bmet.gov.bd/BMET/stattisticalDataAction.

- Cabello, J. G. (2019). A decision model for bank branch site selection: Define branch success and do not deviate. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences, 68, 100599. doi:10.1016/j.seps.2017.09.004

- Carling, J. (2008). The determinants of migrant remittances. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 24(3), 581–598. doi:10.1093/oxrep/grn022

- Cinar, N., & Ahiska, S. S. (2010). A decision support model for bank branch location selection. International Journal of Human and Social Sciences, 5(13), 846–851.

- Crafts, N., & Mulatu, A. (2006). How did the location of industry respond to falling transport costs in Britain before world war I? The Journal of Economic History, 66(3), 575–607.

- Cragg, J. G., & Donald, S. G. (1993). Testing identifiability and specification in instrumental variable models. Econometric Theory, 9(2), 222–240.

- Domenech, J. (2008). Mineral resource abundance and regional growth in Spain, 1860–2000. Journal of International Development: The Journal of the Development Studies Association, 20(8), 1122–1135. doi:10.1002/jid.1515

- Ellison, G., & Glaeser, E. L. (1999). The geographic concentration of industry: does natural advantage explain agglomeration? American Economic Review, 89(2), 311–316.

- Freund, C., & Spatafora, N. (2008). Remittances, transaction costs, and informality. Journal of Development Economics, 86(2), 356–366.

- Khondoker, B. H., Wadood, S. N., & Barua, S. (2011). Urbanization management and emerging regional disparity in Bangladesh: Policies and strategies for decentralized economic growth. In M. K. Mujeri, & S. Alam (Eds.) Sixth Five Year Plan 2011-2015, Background Papers, Volume 4: Cross Sectoral Issues, chap. 2, (pp. 55–188). Bangladesh: BIDS and GED, Planning Commission, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh.

- Liang, F.-Y., Ryvak, M., Sayeed, S., & Zhao, N. (2012). The role of natural gas as a primary fuel in the near future, including comparisons of acquisition, transmission and waste handling costs of as with competitive alternatives. Chemistry Central Journal, 6(1), 1–24.

- Maimbo, M. S. M., El Qorchi, M. M., & Wilson, M. J. F. (2003). Informal Funds Transfer Systems: An analysis of the informal hawala system. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

- Marie, M., & Binod, K. (2020). World migration report. Tech. rep., International Organization for Migration. URL https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/wmr_2020.pdf

- Migration and Development Brief 34. (May 2021). Reterived July 30, 2021, from https://www.knomad.org/publication/migration-and-development-brief-34.

- Min, H. (1989). A model-based decision support system for locating banks. Information & Management, 17(4), 207–215.

- Mookerjee, R., & Roberts, J. (2011). Banking services, transaction costs and international remittance flows. Applied Economics Letters, 18(3), 199–205.

- Niimi, Y., & Ozden, C. (2006). Migration and remittances: causes and linkages. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, (4087). Washington, DC: The World Bank Group.

- Puri, S., Ritzema, T., et al. (1999). Migrant worker remittances, micro-finance and the informal economy: prospects and issues. Geneva, Switzerland: Social Finance Unit, International Labour Office, Geneva.

- Ratha, D. (2003). Workers’ remittances: an important and stable source of external development finance. Global Development Finance, 1&2, 157–175.

- Schiantarelli, F. (2005). Global economic prospects 2006: economic implications of remittances and migration. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- Siddiqui, T., & Abrar, C. R. (2001). Migrant Worker Remittances and Micro-finance in Bangladesh. Geneva, Switzerland: Social Finance Programme, International Labour Office.

- Siegel, M., & Lücke, M. (2013). Migrant transnationalism and the choice of transfer channels for remittances: The case of Moldova. Global Networks, 13(1), 120–141.

- Stock, J. H., Wright, J. H., & Yogo, M. (2002). A survey of weak instruments and weak identification in generalized method of moments. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, 20(4), 518–529.

Appendix

Yearly Average Remittance Inflow Per Migrant for Selected Characteristics.

Table A.1. Yearly average remittance inflow per migrant for selected characteristics

Robustness

BASELINE MODEL

We checked the sensitivity of our main results with different specifications by using alternative sets of control variables. The results are presented in in the Appendix section.

Panel A of presents the regression results for and

and Panel B presents the results for

and

In both cases, ln(Branches) is used as the main explanatory variable with division fixed effects and host country fixed effects only (i.e. without the characteristics of households, remittance senders and receivers). The coefficient of ln(Branches) remains negative and statistically significant at the 1% level in both Panel A and Panel B for IV regressions (columns 1 and 2).

Table A.2 Regression results of choice of informal channels (OLS and IV estimation)

Alternative Specifications of Informal Ever and Informal Only Models

in the Appendix shows the IV estimation results for and

by including the household characteristics and senders along with ln(Branches), division fixed effects and host country fixed effects. Columns Equation(3)

(3)

(3) and Equation(4)

(4)

(4) exclude sender characteristics but remain similar to columns Equation(1)

(1)

(1) and Equation(2)

(2)

(2) in terms of other explanatory variables. repeats the same models for

and

variables.

Table A.3. 2SLS estimation results for choice of informal channels

Alternative Specifications of Hundi Ever and Hundi Only Models

Table A.4. 2SLS estimation results for choice of hundi channel

ivprobit Estimation Results

To reconfirm the consistency and robustness of our findings, we estimate the previous models using the ivprobit estimation procedure for all four outcome variables of interest: and

The ivprobit estimation results are presented in . The estimated coefficient of ln(Branches) for all four outcomes is negative and statistically significant at the 1% level. The results confirmed our main findings that the availability of bank branches in a particular upazila reduces the usage of informal remittance channels.

Table A.5. ivprobit estimation results for choice of informal channels and hundi channel

Marginal Effect

Table A.6. Marginal effect of from the ivprobit estimation results for the choice of informal channels on the availability of bank branches